Abstract

Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC), also called stress cardiomyopathy, is a transient reversible left ventricular dysfunction mimicking acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Studies have shown similar rates of in-hospital complications in TTC and myocardial infarction (MI). Left bundle branch block (LBBB) is associated with increased mortality in patients with MI; however, similar studies comparing outcomes of TTC in the presence of LBBB are lacking.

Methods

The 2016 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was queried to identify all admissions with a primary discharge diagnosis of TTC. Diagnosis-specific codes were used to stratify patients based on the presence or absence of LBBB. Both population sets were paired using 1:10 propensity score matching. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to compare various in-hospital outcomes among both groups.

Results

Amongst 7270 admissions for TTC, 226 patients had concomitant LBBB. After performing 1:10 propensity matching, 130 patients with LBBB were compared to 1275 patients without LBBB. The presence of LBBB was associated with increased odds of cardiogenic shock (AOR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.21–3.99, p = 0.0097); ventricular arrhythmia (AOR 1.99, 95% CI 1.11–3.57, p = 0.02), acute congestive heart failure (AOR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.01–2.2, p = 0.04), and sudden cardiac arrest (AOR = 3.37, 95% CI 1.59–7.13, p = 0.0001). There was no statistical difference in all-cause in-hospital mortality, however a trend towards worsening was noted.

Conclusions

The incidence of arrhythmia and shock in patients with TTC does not correlate with the extent of myocardium involvement. The presence of LBBB in such cases can help recognize at-risk populations, and with timely intervention, life-threatening complications can be avoided. Despite limitations of the dataset and inability to establish causality, prospective studies with longer follow-up are warranted.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Conduction disorders, Left bundle branch block, Stress cardiomyopathy, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy

Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) also called stress cardiomyopathy or broken heart syndrome, is described as short-term reversible left ventricular dysfunction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) [1]. Dote et al. first reported the condition in 1991 to describe myocardial stunning in five patients with multi-vessel coronary spasm and no evidence of CAD [2]. The term TTC was coined due to the echocardiographic resemblance of the left ventricle to a fishing apparatus called ‘takotsubo’ commonly used in Japan to catch octopus. TTC characteristically causes hypokinesis of the left ventricle apical wall resulting in systolic bulging of the apex, hence the name apical ballooning syndrome. The upgraded International Takotsubo Diagnostic Criteria (InterTAK Diagnostic criteria) was reported by Ghadri et al. in ‘The International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome’ released in the year 2018 [3]. Besides the typical TTC affecting the apex, ‘atypical’ variants of TTC involving non-apical myocardial territories such as the base, mid ventricles, focal, and diffuse ventricle wall have also been reported in the literature [3]. Often preceded by a physical or emotional stressor, TTC can lead to life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern results from a disruption of the normal conducting capacity of both anterior and posterior left fascicles of His-Purkinje system (HPS). Interruption of impulse conduction leads to the chaotic transmission through the ventricular myocardium leading to broadening of the QRS complex on electrocardiogram (EKG). Often seen in asymptomatic young patients, LBBB can represent underlying structural heart disease, especially when presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). New LBBB in a patient with presumed ACS is considered ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) equivalent [4]. Several studies have highlighted LBBB as an independent predictor of mortality in patients with CAD [5–7]. Similar studies, however, in patients with TTC are lacking. TTC can mimic ACS as both conditions present with similar symptoms: elevated serum cardiac biomarkers and electrocardiographic changes. The risk of in-hospital complications with TTC is reportedly similar to ACS [8]. Increased age, presence of physical stressor, and ejection fraction (EF) of < 40% have all been associated with poor prognosis in TTC [9]. However, a positive correlation between the degree of ventricular dysfunction and incidence of hypotension and cardiogenic shock in TTC has not been established [10, 11]. Given the lack of indicators to suggest poor prognosis or rates of complications in TTC, we carried out a retrospective study to assess for clinical outcomes in this population, when associated with chronic or new-onset LBBB.

Methods

Data Sources

The largest all-payer database of in-patient hospitalization in the United States, the 2016 National Inpatient Sample (NIS), was used to extract the study population [12]. The NIS is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The NIS is primarily derived from billing data submitted by hospitals to statewide data organizations across the USA. The 2016 NIS comprises 47 statewide organizations including 96% of hospital admissions from U.S. community hospitals. The database represents a 20% stratified sample of all inpatient discharges from acute care hospitals excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care facilities. Each hospitalization includes de-identified patient information such as demographics, discharge diagnosis as identified by the international classification of diseases, tenth revision clinical modification (ICD-10 CM), procedures performed (ICD-10 PCS), comorbid conditions, and final outcome. Compared to previous versions of older datasets, the 2016 database uses ICD-10 CM codes instead of ICD-9 CM and has a self-weighting design that reduces the margin of error while calculating estimates. The 2016 NIS format allowed identification of one primary discharge diagnosis and up to 24 secondary discharge diagnoses based on ICD-10-CM codes. Institutional review board approval was not required as the dataset was publicly acquired and consisted of de-identified patient information.

Study Population

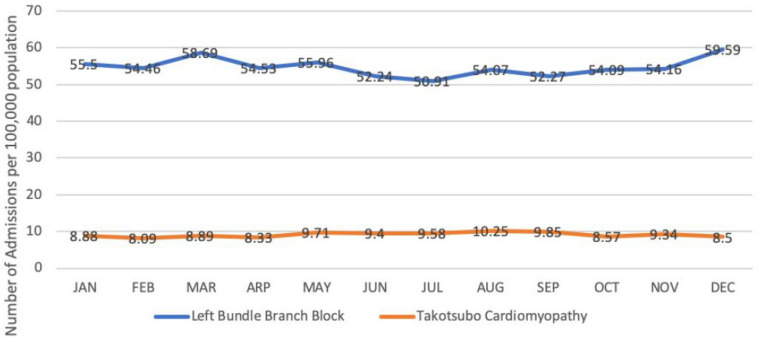

We queried the 2016 NIS to recognize all unweighted admissions for patients aged > 18 years who were discharged with a primary diagnosis of TTC. Sampling weights were only applied to calculate the national rates for trends of TTC and LBBB by month as recommended by HCUP for trend analysis (Fig. 1). ICD-10-CM codes developed by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) were utilized to identify the study cohort. Patients with primary discharge ICD-10-CM code I51.81 applicable to patients with reversible left ventricular dysfunction following sudden emotional stress, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, TTC, transient left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome as defined by CMS were selected for the study. One of the prerequisites to diagnose TTC as defined by the Mayo Clinic Criteria is either the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) on cardiac catheterization or left ventricle dysfunction out of proportion to the angiographic findings [13]. To improve cohort characteristic and TTC specificity, only patients who underwent cardiac catheterization were included in the study. TTC patients who did not undergo cardiac catheterization were excluded. Once patients with TTC were identified, the cohort was stratified into two groups based on the presence or absence of LBBB (ICD-10-CM code I44.7). Patients with TTC without LBBB served as the reference population, as opposed to the testing population with concomitant LBBB. Respective ICD-10-CM codes were used to categorize comorbid conditions in both groups. The list of ICD codes used in the analysis to compare comorbidities, diagnosis, and procedures between both groups are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Annual trend of all hospitalizations related to takotsubo cardiomyopathy and left bundle branch block. The Y-axis shows the rates per 100,000 admissions

Table 1.

International classification of diseases, tenth revision clinical modification (ICD-10-CM) codes used to compare diagnosis, morbidities, and procedures between both groups

| Diagnosis/comorbidities/procedures | ICD-10-CM/ICD-10-PCS codes |

|---|---|

| Takotsubo cardiomyopathy | I5181 |

| Left bundle branch block | I447 |

| Chronic congestive heart failure | I5022, I5032, I5042 |

| Chronic kidney disease | N181, N182, N183, N184, N185, N189 |

| Dyslipidemia | E782, E784 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | J43, J44 |

| Essential hypertension | I10 |

| Coronary artery disease | I252, I249, I2510, I25110, I25111, I25118, I25119, I259, I2583 |

| Obesity | E6601, E6609, E661-E663, E668-9, Z6825-Z6845 |

| Alcohol | F1010, F1011, F10120-21, F10129, F10150-51, F10159, F10180-F10182, F10188, F1019-21, F10220-21, F10229, F10230-32, F10239, F1024 |

| Smoking | F17203, F17208, F17209, F17210, F17211, F17213, F17218, F17219, F17220, F17221, F17223, F17228, F17290, F17291, F17293, F17298, F17299 |

| Cardiac catheterization without intervention | 4A023N6, 4A023N7, 4A023N8, B2000Z, B2001ZZ, B200YZZ, B2010ZZ, B2011ZZ, B201YZZ, B2020ZZ, B2021ZZ, B202YZZ, B2030ZZ, B2031ZZ, B203YZZ, B2040ZZ, B2041ZZ, B204YZZ, B2050ZZ, B2051ZZ, B205YZZ, B2060ZZ, B2061ZZ, B206YZZ, B2070ZZ, B2071ZZ, B207YZZ, B2080ZZ, B2081ZZ, B208YZZ, B20F0ZZ, B20F1ZZ, B20FYZZ, B210010, B2100ZZ, B210110, B2101ZZ, B210Y10, B210YZZ, B211010, B2110ZZ, B211110, B2111ZZ, B211Y10, B211YZZ, B212010, B2120ZZ, B212110, B2121ZZ, B212Y10, B212Y10, B212YZZ, B213010, B2130ZZ, B213110, B2131ZZ, B213Y10, B213YZZ, B2140ZZ, B2141ZZ, B214YZZ, B2150ZZ, B2151ZZ, B215YZZ, B2160ZZ, B2161ZZ, B216YZZ, B2170ZZ, B2171ZZ, B217YZZ, B2180ZZ, B2181ZZ, B218YZZ, B21F0ZZ, B21F1ZZ, B21FYZZ |

| Cardiac catheterization with intervention | In addition to cardiac cath codes; all PCS codes under 02703, 02704, 02713, 02714, 02723, 02724, 02733, 02734, 02C03, 02C04, 02C13, 02C14, 02C23, 02C24, 02C33, 02C34 categories |

| Hypothyroidism | E039 |

| Hyperthyroidism | E0590 |

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome of the analysis was to study the impact of LBBB on in-hospital mortality in patients with TTC. Secondary outcomes included rates of cardiogenic shock, ventricular arrhythmia, sudden cardiac arrest, acute congestive heart failure (CHF), total hospital cost, and length of stay. Ventricular arrhythmia included diagnostic codes for both ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation. The list of ICD codes used in the analysis to compare outcomes between both groups are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

International classification of diseases, tenth revision clinical modification (ICD-10-CM) codes used to compare outcomes between both groups

| Outcomes | ICD codes |

|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock | R57.0 |

| Acute kidney injury | N170, N171, N172, N178, N179, N19 |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | I472, I4901, I4902 |

| Acute congestive heart failure | I5021, I5031, I5041, I5023, I5033, I5043 |

| Sudden cardiac arrest | I462, I468, I469 |

Statistical Analysis

We used a propensity scoring method to match two cohorts in order to mitigate selection bias and to control for patient and institutional imbalances. The scoring was based on a multivariate logistic regression model accounting for all the variables, as mentioned in Table 3. Using 8-to-1-digit match, we paired each admission in TTC plus LBBB group with ten admissions in TTC without LBBB group. Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables, and the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. A logistic regression model was used to examine the associations between LBBB and various in-hospital outcomes after adjusting the variables listed in Table 3. The monthly trends for TTC and LBBB were calculated using sampling trends as recommended by HCUP. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics for patients with and without left bundle branch block (LBBB) before calculating propensity scores

| Variables | With LBBB (n = 135) | Without LBBB (n = 3330) | Total (n = 3465) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 73.1 (10.1) | 66.6 (12.6) | 66.9 (12.6) | < 0.0001 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 116 (85.9%) | 2880 (86.5%) | 2996 (86.5%) | 0.8312 |

| Male | 19 (14.1%) | 447 (13.4%) | 466 (13.4%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 113 (83.7%) | 2746 (82.5%) | 2859 (82.5%) | 0.9629 |

| Black | 10 (7.4%) | 259 (7.8%) | 269 (7.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 5 (3.7%) | 176 (5.3%) | 181 (5.2%) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3 (2.2%) | 54 (1.6%) | 57 (1.6%) | |

| Native American | 1 (0.7%) | 20 (0.6%) | 21 (0.6%) | |

| Other | 3 (2.2%) | 75 (2.3%) | 78 (2.3%) | |

| Household income | ||||

| $1–24,999 | 33 (24.4%) | 890 (26.7%) | 923 (26.6%) | 0.3818 |

| $25,000–34,999 | 37 (27.4%) | 882 (26.5%) | 919 (26.5%) | |

| $35,000–44,999 | 42 (31.1%) | 847 (25.4%) | 889 (25.7%) | |

| 45,000 or more | 23 (17.0%) | 711 (21.4%) | 734 (21.2%) |

| Comorbidities | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 16 (11.9%) | 617 (18.5%) | 633 (18.3%) | 0.0491 |

| Alcohol | 2 (1.5%) | 160 (4.8%) | 162 (4.7%) | 0.0730 |

| All cardiac catheterizations | 135 (100.0%) | 3330 (100.0%) | 3465 (100.0%) | NA |

| Cardiac catheterizations with intervention | 6 (4.4%) | 199 (6.0%) | 205 (5.9%) | 0.4597 |

| Cardiac catheterizations without intervention | 129 (95.6%) | 3131 (94.0%) | 3260 (94.1%) | 0.4597 |

| Chronic congestive heart failure | 8 (5.9%) | 249 (7.5%) | 257 (7.4%) | 0.5001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 27 (20.0%) | 327 (9.8%) | 354 (10.2%) | 0.0001 |

| Obesity | 23 (17.0%) | 465 (14.0%) | 488 (14.1%) | 0.3143 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (28.9%) | 790 (23.7%) | 829 (23.9%) | 0.1679 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 (2.2%) | 63 (1.9%) | 66 (1.9%) | 0.7831 |

| COPD | 28 (20.7%) | 773 (23.2%) | 801 (23.1%) | 0.5041 |

| CAD | 87 (64.4%) | 1718 (51.6%) | 1805 (52.1%) | 0.0034 |

| Essential hypertension | 82 (60.7%) | 1881 (56.5%) | 1963 (56.7%) | 0.3282 |

| Hypothyroidism | 30 (22.2%) | 548 (16.5%) | 578 (16.7%) | 0.0781 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 0 | 17 (0.5%) | 17 (0.5%) | 0.4053 |

Results

A total of 7270 unweighted admissions with a primary discharge diagnosis of TTC were identified from the dataset. Out of 7270 patients, 47.66% (n = 3465) underwent cardiac catheterization and were included in the study. The remaining 52.44% of patients (n = 3805) who did not undergo cardiac catheterization were excluded from the study. Previous studies have observed a temporal trend of increased TTC admissions from April to September. [14]. We conducted a similar trend analysis for all hospitalizations in the year 2016. Figure 1 shows the monthly admission trends of TTC and LBBB for the year 2016. The peak incidence of TTC admissions, 10.2 per 100,000 admissions, was seen in August correlating with the findings studied previously.

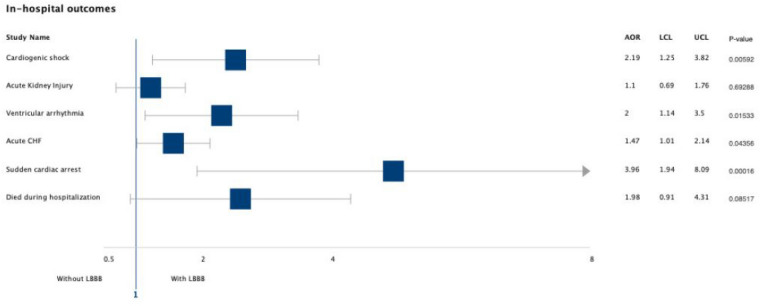

Among 3465 TTC patients who underwent cardiac catheterization, 86.46% (n = 2996) were females and 3.89% (n = 135) had concomitant diagnosis of LBBB. Table 3 demonstrates baseline characteristics and comorbidities for both groups (with and without LBBB) before calculating the propensity scores. Patients with LBBB were older (73.1 vs. 66.6 years, p < 0.0001), had higher incidence of coronary artery disease (64.4 vs. 51.6%, p = 0.0034), and chronic kidney disease (20.0 vs. 9.8%, p = 0.0001). The rates of smoking were higher in patients without LBBB (18.5 vs. 11.9%, p = 0.04). There was no statistical difference between both groups in terms of gender, race, income, and other comorbidities such as chronic congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease, diabetes mellitus, and obesity, among others. Among patients with LBBB, 4.4% (n = 6) had cardiac catheterization with some capacity of intervention (angioplasty or stent placement) as opposed to 6.0% (n = 199) in those without LBBB. The rates of cardiogenic shock (11.9 vs. 6.5%, p = 0.0059), ventricular arrhythmia (11.9 vs. 6.5%, p = 0.01), sudden cardiac arrest (7.4 vs. 2.5%, p = 0.0001), and acute congestive heart failure (37.8 vs. 25.2%, p = 0.043) were higher in the LBBB group (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forrest plot graph showing adjusted odds ratio for various in-hospital outcomes before calculating propensity score. AOR adjusted odds ratio, LCL lower confidence limit, UCL upper confidence limit

After calculating propensity scores, we paired 130 admissions in the LBBB group to 1275 admissions without LBBB. Table 4 shows the baseline characteristics and comorbidities for both groups after performing propensity matching. The mean age of the cohort after pairing was 73.0 ± 10.3 years, comprising 87.3% (n = 1226) females. The earlier noted statistical difference in the rates of coronary artery disease, age, chronic kidney disease, and smoking was annulled post-pairing, advocating successful matching. Post-matching, there was less than a 5% standardized mean difference between both groups. Post-pairing, LBBB was associated with higher rates of cardiogenic shock (11.5 vs. 5.9%, p = 0.0097), ventricular arrhythmia (12.3 vs. 6.4%, p = 0.02), sudden cardiac arrest (7.7 vs. 2.5%, p = 0.001), and acute congestive heart failure (37.7 vs. 28.9%, p = 0.04). The overall in-hospital mortality was found 2.6% in all patients (with and without LBBB) with TTC. We did not achieve statistical significance for acute kidney injury (19.2 vs. 17.6%, p = 0.769) and all-cause in-hospital mortality (5.4 vs. 2.7%, p = 0.113) in the LBBB group, however a trend towards worsening was noted.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics for patients with and without left bundle branch block (LBBB) after calculating propensity scores

| Variables | With LBBB (n = 130) | Without LBBB (n = 1275) | Total (n = 1405) | p value | Standardized differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 73.0 (10.3) | 73.5 (9.8) | 73.0 (10.3) | 0.5561 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | − 2.0 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 112 (86.2%) | 1114 (87.4%) | 1226 (87.3%) | 0.6914 | |

| Male | 18 (13.8%) | 161 (12.6%) | 179 (12.7%) | ||

| Race | |||||

| White | 109 (83.8%) | 1066 (83.6%) | 1175 (83.6%) | 0.9165 | 0.1 |

| Black | 9 (6.9%) | 86 (6.7%) | 95 (6.8%) | − 0.2 | |

| Hispanic | 5 (3.8%) | 72 (5.6%) | 77 (5.5%) | NA | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3 (2.3%) | 25 (2.0%) | 28 (2.0%) | − 2.4 | |

| Native American | 1 (0.8%) | 5 (0.4%) | 6 (0.4%) | 1.3 | |

| Other | 3 (2.3%) | 21 (1.6%) | 24 (1.7%) | 1.1 | |

| Household income | 3.4 | ||||

| $1–24,999 | 32 (24.6%) | 325 (25.5%) | 357 (25.4%) | 0.3856 | − 1.0 |

| $25,000–34,999 | 35 (26.9%) | 340 (26.7%) | 375 (26.7%) | 4.0 | |

| $35,000–44,999 | 40 (30.8%) | 318 (24.9%) | 358 (25.5%) | − 0.8 | |

| 45,000 or more | 23 (17.7%) | 292 (22.9%) | 315 (22.4%) | − 0.2 |

| Comorbidities | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | 2.6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 16 (12.3%) | 157 (12.3%) | 173 (12.3%) | 0.9984 | − 0.9 |

| Alcohol | 2 (1.5%) | 20 (1.6%) | 22 (1.6%) | 0.9789 | − 0.5 |

| All cardiac catheterization | 130 (100.0%) | 1275 (100.0%) | 1405 (100.0%) | NA | |

| Cardiac catheterization with intervention | 6 (4.6%) | 97 (7.6%) | 103 (7.3%) | 0.2124 | 0 |

| Cardiac catheterization without intervention | 124 (95.4%) | 1178 (92.4%) | 1302 (92.7%) | 0.2124 | − 2.4 |

| Chronic congestive heart failure | 8 (6.2%) | 75 (5.9%) | 83 (5.9%) | 0.9005 | 1.3 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 22 (16.9%) | 194 (15.2%) | 216 (15.4%) | 0.6072 | 1.1 |

| Obesity | 19 (14.6%) | 191 (15.0%) | 210 (14.9%) | 0.9115 | 3.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 (28.5%) | 340 (26.7%) | 377 (26.8%) | 0.6600 | 4.0 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 (2.3%) | 31 (2.4%) | 34 (2.4%) | 0.9303 | − 0.8 |

| COPD | 27 (20.8%) | 266 (20.9%) | 293 (20.9%) | 0.9801 | − 0.2 |

| CAD | 83 (63.8%) | 798 (62.6%) | 881 (62.7%) | 0.7775 | 2.6 |

| Essential hypertension | 82 (63.1%) | 810 (63.5%) | 892 (63.5%) | 0.9187 | − 0.9 |

| Hypothyroidism | 28 (21.5%) | 277 (21.7%) | 305 (21.7%) | 0.9607 | − 0.5 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 0 | 6 (0.5%) | 6 (0.4%) | 0.4331 | NA |

| Propensity scores | 0.03091 | 0.03091 | NA | 0 |

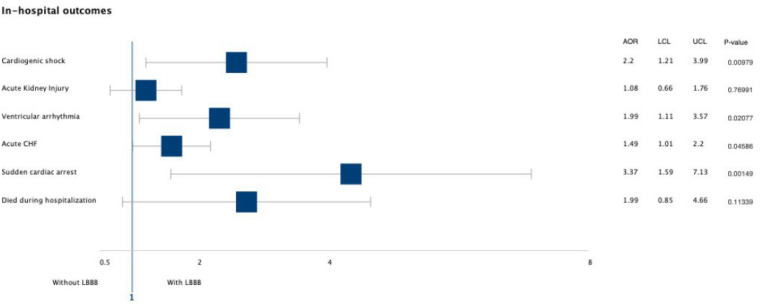

The odds of having cardiogenic shock (AOR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.21–3.99, p = 0.0097) and ventricular arrhythmia (AOR = 1.99, 95% CI 1.11–3.57, p = 0.02) were doubled in the LBBB group. Similarly, LBBB was also associated with increased odds of having sudden cardiac arrest by almost three-fold in comparison to those without LBBB (AOR = 3.37, 95% CI 1.59–7.13, p = 0.001) (Fig. 3). The presence of LBBB was not associated with increased hospital charges or length of hospitalization. In the unmatched population, the median length of stay was 3.0 days (IQR = 2.0–6.0 days) compared to 4.0 days (IQR = 2.0–7.0 days). These findings did not change post-matching.

Fig. 3.

Forrest plot graph showing adjusted odds ratio for various in-hospital outcomes after calculating propensity score. AOR adjusted odds ratio, LCL lower confidence limit, UCL upper confidence limit

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first-ever study performed to assess the outcomes of TTC in patients with ventricular conduction abnormalities such as LBBB. After adjusting for other comorbidities, we found that LBBB is independently associated with increased odds of cardiogenic shock, sudden cardiac arrest, ventricular arrhythmia, and acute congestive heart failure in patients with TTC. The hospitalization all-cause mortality rates were higher in the LBBB group; however, this number did not reach statistical significance.

The prevalence of LBBB is around 0.06–1% in the general population and increases with age [15, 16]. The incidence of LBBB increases in patients with a history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure. Not only is LBBB associated with various cardiovascular disease but also its presence at a young age increases the risk of acquiring cardiovascular health problems later in life [17, 18]. More often than not, LBBB is associated with slowly progressing aging or fibrotic conduction system, left ventricular hypertrophy rather than acute MI [19]. The prognostic significance of LBBB in patients with angina and ACS is well established [6, 7]. Bansilal et al. studied long-term outcomes in patients with angina who presented with LBBB and found increased rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and lower survival rates at 16 years of follow-up [20]. For MI to present as new-onset LBBB, myocardial damage involving the distal conduction system is required. This usually happens in cases with transmural MI involving extensive myocardial territory, which partly explains why ACS patients with LBBB tend to have a poorer prognosis [21].

The exact pathophysiology behind TTC remains ambiguous. The hypothesis of catecholamine surge resulting in myocardial stunning has been backed by elevated plasma catecholamine levels and histologic evidence during endomyocardial biopsies [22–24]. Other mechanisms, such as coronary artery spasm and microvascular dysfunction, have also been postulated [25, 26]. Since the extent of myocardial involvement in TTC extends beyond the territory of a single vessel, the HPS can be frequently involved, resulting in LBBB. ST-segment elevation and T wave inversion remain the two most common electrocardiogram (EKG) changes in patients with TTC as studied by Namgung [27]. Parodi et al. reported an estimated prevalence of LBBB in 9% of TTC patients at the time of diagnosis [28]. Other isolated case reports establishing an association between TTC and new or old LBBB have also been reported in the literature [29–31]. The presence of conduction abnormalities in TTC can be attributed to decreased blood flow to the ventricular conduction system either due to left ventricular dyskinesia or catecholamine-induced vasospasm [30].

During the acute and subacute phases of TTC, patients are prone to cardiogenic shock, ventricular arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac arrest. Initial proposed reports of favorable prognosis in TTC patients compared to ACS have been challenged in recent studies. The large International Takotsubo Registry reported 30-day mortality of 5.9% in TTC patients and a similar study based in Sweden found a 30-day mortality rate of 4.1%, similar to those with ACS [32, 33]. TTC can occur without an existing stress trigger (primary TTC) as opposed to those with identifiable trigger or when already hospitalized for other medical conditions (secondary TTC). Mortality rates also differ between primary and secondary TTC. A study based on the United States Medicare database by Murugiah et al. showed worse 30-day in secondary TTC compared to principle TTC (2.5 vs. 4.7%) [34]. Several studies have been carried out to identify the factors responsible for high mortality rates in TTC. Ghadri et al. showed higher mortality rates when TTC is affiliated with a physical stressor compared to an emotional stressor [35]. A systematic review of 54 studies including a total of 4679 patients showed old age, physical stressor, and atypical ballooning were all associated with unfavorable prognosis in TTC [36]. Active malignancy or even a history of cancer increases mortality in TTC [37]. The mortality rates were higher in TTC patients presenting with T-wave inversion on EKG compared to ACS patients with a similar electrocardiographic presentation [38]. Similar results were not seen in those presenting with ST-elevation on EKG [39].

The use of LBBB as an indicator to predict outcomes in TTC has not been advocated previously. In theory, myocardial stunning extensive enough to disrupt the distal conductive system to result in LBBB should portend worse consequences. Similarly, in patients with known LBBB who develop new-onset TTC, the desynchrony of the left ventricle could potentiate underlying heart failure. This was evident in our study, as the rates of acute congestive heart failure were higher in patients with LBBB. Another potential explanation for poor outcomes in patients presenting with LBBB is the association of the latter with other comorbid conditions [40]. Stenestrand et al. reported that in patients with MI when adjusted for age, baseline characteristics, comorbid conditions, and left ventricular ejection fraction, LBBB was not independently associated with 1-year mortality [41]. Similar equivocal results with LBBB have also been reported in TTC patients [28]. Despite early reports questioning the impact of LBBB in ACS or TTC when adjusted for comorbidities, there was undoubtedly a strong predilection between LBBB and in-hospital adverse events in our study when comparing two equally matched cohorts.

The ensuing limitations should be considered when translating the results of our study. The NIS database relies heavily on physician ICD-10-CM coding, which can leave room for diagnosis error and selection bias. This was minimized by excluding the patients who did not undergo cardiac catheterization. Secondly, sinus tachycardia in patients with LBBB can appear as wide complex tachycardia (WCT) and can be wrongly interpreted as ventricular tachycardia again, raising the possibility of diagnostic errors. However, the higher rates of sudden cardiac arrest in the LBBB group can indicate the true nature of the above-mentioned ventricular arrhythmia. Since both old and new-onset LBBB had the same ICD code, we were unable to distinguish the impact on one compared to the other. Propensity matching to pair both groups for comorbidities resulted in the loss of power, which could explain why despite the higher rates of acute kidney injury and in-hospital deaths in patients with LBBB, both of these findings were not statistically significant (type II error). The 2016 NIS uses ICD-10-CM codes as opposed to ICD-9-CM codes used in previous years. The authors preferred ICD-10-CM codes over ICD-9-CM due to the former’s specificity in diagnostic codes. For this reason, we were unable to extend our analysis to more than 1 year. We were unable to identify the inciting event or the ejection fraction due to the scarcity of available information in NIS. The study also had its strength in being the only analysis to assess the impact of conduction abnormalities, such as LBBB in patients with TTC. The use of propensity scoring aided in creating two similar groups with similar comorbidity profiles establishing the independent role of LBBB in TTC outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we studied the impact of new or chronic LBBB on in-hospital outcomes in patients with TTC. After adjusting for various comorbidities both before and after propensity matching, LBBB was associated with increased odds of various in-hospital complications including cardiogenic shock and ventricular arrhythmias. A trend towards increased in-hospital mortality was also notable. Along with age, physical stressor, and low ejection fraction, the presence of LBBB should be considered as an ominous sign in patients with TTC. Future studies with longer follow-up are warranted to validate our findings further.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Dipesh Ludhwani, Mouyyad Rahaby, Vasu Patel, Saad Jamil, Adam Kedzia and Chunyi Wu have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Institutional review board approval was not required as the dataset was publicly acquired and consisted of de-identified patient information.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed are available in the HCUP-NIS repository. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.8397053.

References

- 1.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):858–865. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dote K. Myocardial stunning due to simultaneous multivessel coronary spasm: a review of five cases. J Cardiol. 1991;21:203–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (part I): clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(22):2032–2046. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesse B, Diaz LA, Snader CE, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Complete bundle branch block as an independent predictor of all-cause mortality: report of 7,073 patients referred for nuclear exercise testing. Am J Med. 2001;110(4):253–259. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00713-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman RA, Alderman EL, Sheffield LT, Saporito M, Fisher LD. Bundle branch block in patients with chronic coronary artery disease: angiographic correlates and prognostic significance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(87)80162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sumner G, Salehian O, Yi Q, et al. The prognostic significance of bundle branch block in high-risk chronic stable vascular disease patients: a report from the HOPE trial. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20(7):781–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929–938. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madhavan M, Rihal CS, Lerman A, Prasad A. Acute heart failure in apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo/stress cardiomyopathy): clinical correlates and Mayo Clinic risk score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(12):1400–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chong CR, Neil CJ, Nguyen TH, et al. Dissociation between severity of takotsubo cardiomyopathy and presentation with shock or hypotension. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(7):401–406. doi: 10.1002/clc.22129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh K, et al. Dissociation of early shock in takotsubo cardiomyopathy from either right or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(12):1141–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.HCUP‐NIS. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Databases. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2018. [PubMed]

- 13.Scantlebury DC, Prasad A. Diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2014;78(9):2129–2139. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aryal MR, et al. Seasonal and regional variation in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(9):1592. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francia P, Balla C, Paneni F, Volpe M. Left bundle-branch block–pathophysiology, prognosis, and clinical management. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30(3):110–115. doi: 10.1002/clc.20034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksson P, Hansson PO, Eriksson H, Dellborg M. Bundle-branch block in a general male population: the study of men born 1913. Circulation. 1998;98(22):2494–2500. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.22.2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider JF, Thomas HE, Kreger BE, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. Newly acquired left bundle-branch block: the Framingham study. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90(3):303–310. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-3-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabkin SW, Mathewson FAL, Tatc RB. Natural history of left bundle-branch block. Br Heart J. 1980;43:164–169. doi: 10.1136/hrt.43.2.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahy GJ, Pinski SL, Miller DP, et al. Natural history of isolated bundle branch block. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:1185–1190. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bansilal S, Aneja A, Mathew V, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with angina pectoris presenting with bundle branch block. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(11):1565–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godman MJ, Lassers BW, Julian DG. Complete bundle-branch block complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1970;282(5):237–240. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197001292820502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paur H, Wright PT, Sikkel MB, et al. High levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a beta2-adrenergic receptor/Gi-dependent manner: a new model of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;126(6):697–706. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.111591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JH, Kang SJ, Song JK, et al. Left ventricular apical ballooning due to severe physical stress in patients admitted to the medical ICU. Chest. 2005;128(1):296–302. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nef HM, Mollmann H, Kostin S, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: intraindividual structural analysis in the acute phase and after functional recovery. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(20):2456–2464. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misumi I, Ebihara K, Akahoshi R, et al. Coronary spasm as a cause of takotsubo cardiomyopathy and intraventricular obstruction. J Cardiol Cases. 2010;2(2):e83–e87. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel SM, Lerman A, Lennon RJ, Prasad A. Impaired coronary microvascular reactivity in women with apical ballooning syndrome (takotsubo/stress cardiomyopathy) Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2013;2(2):147–152. doi: 10.1177/2048872613475891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namgung J. Electrocardiographic findings in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: ECG evolution and its difference from the ECG of acute coronary syndrome. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2014;8:29–34. doi: 10.4137/cmc.s14086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parodi G, Salvadori C, Del Pace S, et al. Left bundle branch block as an electrocardiographic pattern at presentation of patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009;10(1):100–103. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32831a6a26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marmoush FY, Barbour MF, Noonan TE, Al-Qadi MO. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new perspective in asthma. Case Rep Cardiol. 2015;2015:4. doi: 10.1155/2015/640795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Limm BN, Hoo AC, Azuma SS. Variable conduction system disorders in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a case series. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014;73(5):148–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito T, Fujita H, Ichihashi T, Ohte N. Electrocardiographic changes associated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a patient with pre-existing left bundle branch block. Heart Vessels. 2016;31(8):1393–1396. doi: 10.1007/s00380-015-0766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redfors B, Vedad R, Angerås O, et al. Mortality in takotsubo syndrome is similar to mortality in myocardial infarction—a report from the SWEDEHEART registry. Int J Cardiol. 2015;15(185):282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929–938. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murugiah K, Wang Y, Desai NR, et al. Trends in short- and long-term outcomes for takotsubo cardiomyopathy among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries, 2007 to 2012. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2016;4:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghadri JR, Kato K, Cammann VL, Gili S, Jurisic S, Di Vece D, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with takotsubo syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(8):874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelliccia F, Pasceri V, Patti G, et al. Long-term prognosis and outcome predictors in takotsubo syndrome: a systematic review and meta-regression study. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(2):143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunetti ND, Tarantino N, Guastafierro F, et al. Malignancies and outcome in takotsubo syndrome: a meta-analysis study on cancer and stress cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;1:1. doi: 10.1007/s10741-019-09773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gietzen T, El-Battrawy I, Lang S, et al. Impact of T-inversion on the outcome of takotsubo syndrome as compared to acute coronary syndrome. Eur J Clin Investig. 2019;49(4):e13078. doi: 10.1111/eci.13078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gietzen T, El-Battrawy I, Lang S, et al. Impact of ST-segment elevation on the outcome of takotsubo syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:251–258. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S180170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Go AS, Barron HV, Rundle AC, Ornato JP, Avins AL. Bundle-branch block and in-hospital mortality in acute myocardial infarction. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(9):690–697. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-9-199811010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stenestrand U, Tabrizi F, Lindbäck J, Englund A, Rosenqvist M, Wallentin L. Comorbidity and myocardial dysfunction are the main explanations for the higher 1-year mortality in acute myocardial infarction with left bundle-branch block. Circulation. 2004;110(14):1896–1902. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143136.51424.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed are available in the HCUP-NIS repository. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.