Abstract

Membrane proteins are essential for many cell processes yet are more difficult to investigate than soluble proteins. Charged residues often contribute significantly to membrane protein function. Model peptides such as GWALP23 (acetylGGALW5LAL8LALALAL16ALW19LAGA-amide) can be used to characterize the influence of specific residues on transmembrane protein domains. We have substituted R8 and R16 in GWALP23 in place of L8 and L16, equidistant from the peptide center, and incorporated specific 2H-labeled alanine residues within the central sequence for detection by solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy. The resulting pattern of 2H-Ala quadrupolar splitting (Δνq) magnitudes indicates the core helix for R8,16GWALP23 is significantly tilted to give a similar transmembrane orientation in thinner bilayers with either saturated C12:0 or C14:0 acyl chains (DLPC or DMPC) or unsaturated C16:1 ∆9 cis acyl chains. In bilayers of DOPC (C18:1 ∆9 cis) multiple orientations are indicated, while in longer unsaturated DEiPC (C20:1 ∆11 cis) bilayers, the R8,16GWALP23 helix adopts primarily a surface orientation. The inclusion of 10–20 mol% cholesterol in DOPC bilayers drives more of the R8,16GWALP23 helix population to the membrane surface, allowing both charged arginines access to the interfacial lipid head groups. The results suggest that hydrophobic thickness and cholesterol content are more important than lipid saturation for the arginine peptide dynamics and helix orientation in lipid membranes.

Keywords: Arginine, cholesterol, GWALP23, protein-lipid interactions, solid-state NMR spectroscopy

Arginine arrest:

Lipid membrane thickness and cholesterol content were identified as critical factors for defining the orientations and dynamics of transmembrane arginine-containing helices in membrane proteins.

Introduction

Membrane proteins play vital roles in numerous cellular processes including cell signaling, ion transport, and enzyme driven processes.[1] Estimated to make up about 30% of proteins encoded by the human genome, membrane proteins are the target of 50% of current marketed drugs and are implicated in a wide variety of disorders including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases and cystic fibrosis.[1–2] A more thorough understanding of the basic principles that govern membrane protein folding will improve the ability to predict membrane protein structures and functions, and address abnormalities. The constraints imposed by the lipid bilayer environment, nevertheless, present challenges for determining the structures and lipid interactions of membrane proteins, requirements necessary to elucidate disease mechanisms.

It can be difficult to characterize the effects on protein structure induced by the complex lipid bilayer environment. Therefore, it is advantageous to employ, initially, model peptide systems with defined helix geometries and orientations in membranes. Experiments with designed systems can serve to identify protein-lipid interactions with single-residue resolution. Transmembrane α-helices, for example, are comprised mainly of hydrophobic amino acids, with relatively few strongly polar amino acids such as arginine, due to the energetic cost of burying them in the nonpolar membrane environment. While the ionization properties of Lys and His are modulated in bilayer membranes,[3–4] the guanidinium side chain of arginine carries a positive charge in essentially all biological membrane environments.[5–8] The long and flexible arginine guanindino group nevertheless can stretch up or “snorkel” toward the membrane-water interface,[9–10] where it is capable of forming multiple hydrogen bonds with the lipid head groups and water.[11] The snorkeling behavior of the arginine side chain also can result in membrane deformation and water penetration to satisfy the positive charge.[10, 12]

Despite retaining a positive charge in a membrane environment, up to at least pH 12,[5] arginine is highly conserved and plays critical functional roles in many membrane proteins, including sodium channels, acetylcholine receptors, integrins and others.[13] Structures of integral membrane proteins often reveal distinct belts of aromatic and charged residues on both sides of the membrane-spanning segments.[14] Additionally, some seemingly more buried charged residues are crucial for membrane protein function. Charge-charge interactions, sometimes involving “buriedˮ residues, are implicated for example in the regulation of voltage-gated sodium channels, which initiate and propagate action potentials in nerve, muscle, and endocrine cells.[15–17] The S4 transmembrane helix controls the voltage-dependent activation of the channel via four to seven arginine residues, spaced at about three-residue intervals, which act as gating charges in the voltage-sensing mechanism.[14, 17–19] The mechanisms by which these multiple arginine residues are stabilized in the hydrophobic bilayer environment and rearranged within a membrane during an action potential, however, are still debated.[16, 20–22]

The rigid ring structure of cholesterol induces acyl chain order, thereby modifying lipid-bilayer dynamics and fluidity [23–26]. The presence or absence of cholesterol therefore can have dramatic effects on cell activity and could significantly alter the structure and function of membrane proteins by inducing changes in their conformation or redistribution in the membrane.[1, 24] For instance, the voltage-gating ability of a potassium channel, KvAP, is completely lost in DOPC bilayers containing more than 18 mol % cholesterol.[27]

We have reduced the complexity of the membrane environment to facilitate experimental control for investigating the fundamentals of protein-lipid interactions, specifically those involving arginine, phospholipids, and cholesterol. The α-helical transmembrane peptide acetyl-GGALW5LALALALALALALW19L AGA-ethanolamide (“GWALP23”) adopts a well-defined transmembrane orientation with only modest dynamic averaging, making it a useful tool to monitor changes in helix orientation and dynamics in bilayer membranes.[10, 28–29] Using solid-state deuterium NMR, the influence of single “guest” residues on the transmembrane helix tilt and rotation in lipid bilayer membranes can be determined. The guest residues, including charged amino acids, are introduced within the GWALP23 peptide host framework containing site-specifically deuterium labeled alanine residues[1, 3–5, 30].

Previously we found that introducing a single arginine at position 14 in GWALP23 caused the peptide helix to rotate by 80° and to increase its tilt by 10° in DOPC bilayers, thus allowing the arginine to gain access to the aqueous interface of the lipid bilayer.[10] By contrast, a “trapped” arginine, at position 12 in the same 23-residue sequence, located seven residues away from each of two tryptophans, caused the peptide helix to adopt at least three competing orientations.[10, 30] Here we introduce double arginine residues at positions 8 and 16, equidistance from the center of the sequence. We aim to identify and compare the changes in the behavior of the double arginine replacements in GWALP23 to those of the single arginine replacements in saturated and unsaturated lipids of varying lengths. The helix properties for the “inner pair” of arginines 8 and 16 will furthermore be compared in the presence and absence of cholesterol

Results

The model peptide GWALP23-R8,16 (Figure 1) was synthesized successfully with pairs of 2H-labeled alanine residues at several different locations in the sequence. The identities of the 2H-labeled peptides and their levels of deuteration were confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (see Figure S1). The CD spectra of GWALP23-R8,16 in DLPC, DMPC. DPoPC, DOPC, and DEiPC vesicles show minima near 208 nm and a broad shoulder at 222 nm, confirming a predominantly α-helical secondary structure in each of the lipid membranes (Figure S2). The ellipticity ratio ( 222)/( 208) in DPoPC (0.80), DOPC (0.86), and DEiPC (0.85) is somewhat lower than in DLPC or DMPC (0.95), suggesting perhaps small differences in the peptide folding. The addition of cholesterol to GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC results in small changes in the negative ellipticity at 208 nm (Figure S3). The (ε222)/(ε208) ratio decreases marginally yet systematically from 0.86 at 0% cholesterol, to 0.82 at 10% and 0.78 at 20%, again suggesting that increasing amounts of cholesterol may induce small conformational changes.

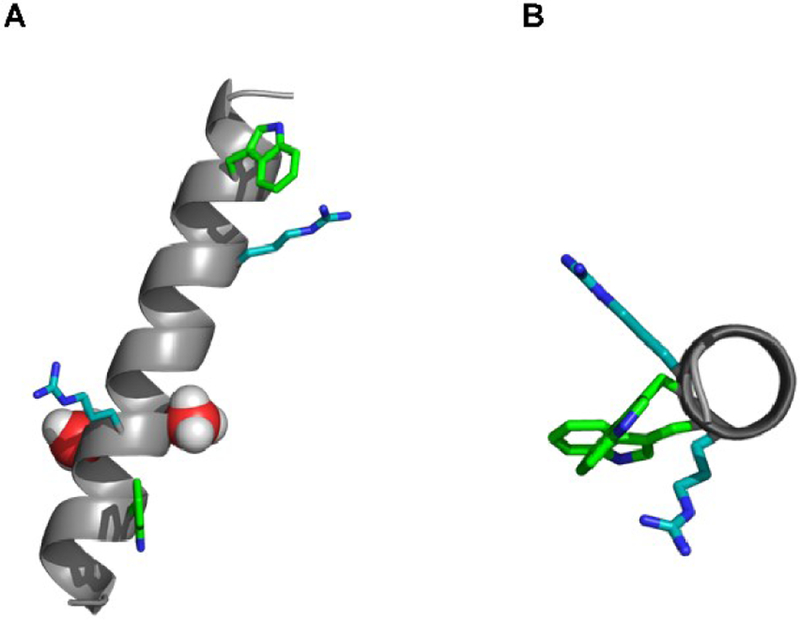

Figure 1.

Molecular models of GWALP R8,16, (A) shown in an arbitrary tilted orientation, with the side chains of A15 and A17 space-filling red and the side chains of W5, R8, R16 and W19 shown as sticks; (B) an end view of the helix to show the relative locations of the larger side chains.

Peptide-lipid samples were aligned on thin glass plates for solid-state NMR spectroscopy, and lipid bilayer alignment was confirmed by solid-state 31P NMR spectroscopy. Importantly, the 31P NMR spectra of oriented samples of GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC alone, or with 10% or 20% cholesterol (Figure S6), reveal well-defined peaks at +28 ppm for the β=0° macroscopic sample orientation and −14 ppm for the β=90° orientation, indicating proper bilayer alignment with or without cholesterol.

Solid-state 2H NMR Spectroscopy:

Deuterium NMR in thin bilayers:

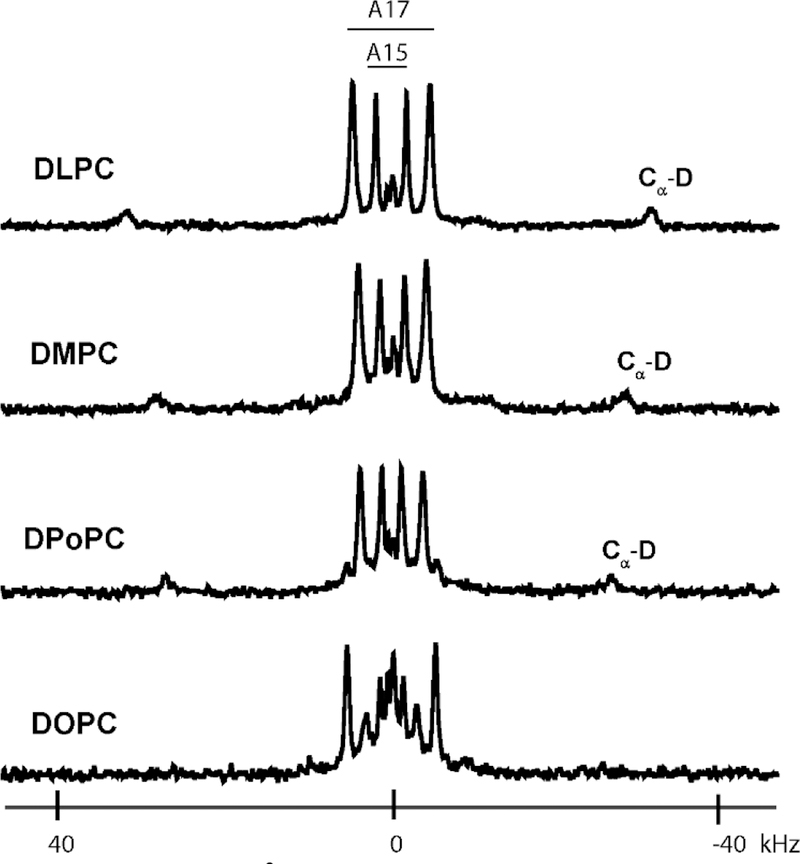

Deuterium NMR spectra of core 2H-alanine residues in the aligned samples of GWALP23-R8,16 in DLPC and DMPC exhibit distinct signals for each side chain methyl group of the core labeled alanine residues 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17, indicating a well-defined transmembrane orientation in each lipid bilayer (Figure S7). Notably, residues A7 and A17, adjacent to arginines R8 and R16, give good 2H-NMR spectra with narrow and distinct 2H quadrupolar splittings (Figure 2) that fit the core helix in DLPC and DMPC (see below). Since A7 and A17 are both observed experimentally to be on the core helix yet located outside of residues R8 and R16, this implies that both arginine residues also must be included in the core helix. Notably, the C D backbone deuteron resonances for A15 and A17 also are clearly resolved in DLPC and DMPC (Figure 2). Indeed, backbone C D resonances are indicative of excellent alignment of a helix undergoing precession about a bilayer normal and often have been observed for Arg-containing transmembrane helices [10, 30–31].

Figure 2.

Solid-state 2H NMR spectra of labeled alanines A15 and A17 of GWALP23-R8,16 in aligned bilayers of DLPC, DMPC, DPoPC, DOPC. The peaks labeled Cα-D arise from the backbone Cα deuteron of residue A17. Sample orientation β = 90°; temperature 50 °C.

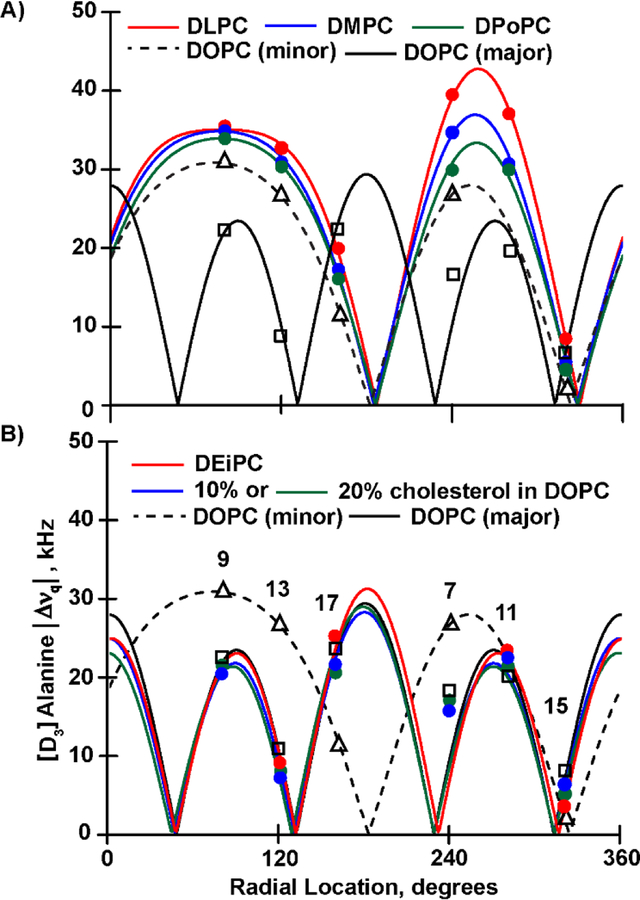

Analysis by the semi-static GALA method, after assignment of the individual 2H NMR signals, provides the characteristic plots for transmembrane orientations with helix tilt (τ0) and rotation (ρ0) angles of GWALP23-R8,16 in the DLPC and DMPC bilayers (Figure 4). The helix tilt 0 values of about 29° in DLPC and 25° in DMPC (Table 2) confirm that GWALP23-R8,16 resides in the membrane as a significantly tilted transmembrane helix. The ρ0 values for azimuthal rotation about the helix axis are indistinguishable, 122° (DLPC) and 120° (DMPC). A modified Gaussian analysis predicts similar ρ0 values of 121° (DLPC) and 120° (DMPC), with τ0 values of 31° for DLPC and 28° for DMPC, slightly higher than those from the semi-static GALA analysis, as is typical when these methods of analysis are compared [32]. The slippage (σρ) from the modified Gaussian analysis is notably low, about 18° in DLPC and DMPC bilayers (Table 2), similar to previous observations for Arg-containing transmembrane helices [31]. Similar results are obtained when the backbone Cα|Δνq| from alanine 7 is included in the analysis, with a minor change to 16° for (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Quadrupolar wave analysis for the tilted helix of GWALP23-R8,16 in bilayer membranes. A. Results for aligned bilayers of DLPC, DMPC, DPoPC and DOPC. The major orientation in DOPC (solid black curve) is surface-bound, while the helix orientation in the thinner lipids and the minor orientation in DOPC (dashed curve) are transmembrane. B. Results for aligned bilayers of DEiPC and of DOPC with 20%, 10% or 0% cholesterol. The minor orientation in DOPC (dashed curve) is transmembrane while the other orientations represent surface-bound helices. Labeled alanine positions are numbered in panel B. Residue A7 does not fit the curve for the surface-bound orientation.

Table 2.

Semi-static GALA and modified Gaussian analysis of GWALP23-R8,16 helix orientations and dynamics in bilayer membranesa

| Lipid | GALA fit results | Modified Gaussian resultsb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Τo | ρo | Szz | RMSD | Τo | ρo | σρ | σΤb | RMSD | |

| DLPC | 29° | 122° | 0.84 | 0.45 | 30° | 121° | 18° | 5° | 0.37 |

| DLPCc | 30° | 120° | 16° | 5° | 0.58 | ||||

| DMPC | 25° | 120° | 0.86 | 0.55 | 26° | 119° | 18° | 5° | 0.47 |

| DMPCc | 26° | 119° | 16° | 5° | 0.69 | ||||

| DPoPC | 23° | 121° | 0.86 | 0.62 | 24° | 120° | 18° | 5° | 0.74 |

| DPoPCc | 24° | 119° | 16° | 5° | 0.94 | ||||

| DOPC (minor) | 21° | 116° | 0.81 | 0.31 | 21° | 116° | 18° | 5° | 1.14 |

| DOPC (major)d | 89° | 43° | 0.56 | 1.09 | 88° | 42° | 25° | 25° | 1.27 |

| DOPC+10% | 88° | 43° | 0.52 | 0.28 | 88° | 42° | 25° | 25° | 0.42 |

| DOPC+20% | 87° | 42° | 0.51 | 0.81 | 87° | 41° | 25° | 25° | 0.77 |

| DEiPC | 87° | 45° | 0.55 | 0.42 | 85° | 42° | 25° | 25° | 0.82 |

The analysis methods were described previously [32]. The units for RMSD are kHz. Unless otherwise noted, each analysis is based on the deuterium (2H) quadrupolar splittings for the CD3 side chains of six central alanine residues 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17 in the core helix of the transmembrane or surface-bound peptide.

For the modified Gaussian analysis [32, 34], στ was assigned the fixed value noted in the table; Szz was assigned the fixed value of 0.88. For the surface orientations, a higher fixed value of 25° for στ was needed to fit the data.

Analysis based on the deuterium (2H) quadrupolar splitting for the backbone C -D for residue A17 (see Figure 2) in addition to those for the CD3 side chains of the central alanine residues 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17.

Residue 7 did not fit the helix and was omitted from the analysis of the surface orientations (where τo is near 88°).

Deuterium NMR in short (C16:1, DPoPC) unsaturated lipid bilayers:

For comparison with results in the relatively thin DLPC and DMPC bilayers, oriented NMR experiments were performed in bilayers of DPoPC, which has two 16-carbon unsaturated acyl chains. The 2H NMR spectra of labeled GWALP23-R8,16 in DPoPC bilayers show well-defined single quadrupolar splittings for each deuterated alanine side chain, similar to those in DLPC and DMPC bilayers (Figure 2 and Figure S7). As in DLPC and DMPC, the CαD backbone deuteron resonances from A15 and A17 are clearly resolved in DPoPC (Figure 2). Semi-static GALA analysis (Table 2) in DPoPC gives tilt and rotation angles for GWALP23-R8,16 of 23° and 121°, respectively, confirming a transmembrane helical conformation similar and slightly less tilted than that in DLPC and DMPC (Figure 4A). Modified Gaussian analysis gives again a slightly higher value for τ0 (24°) compared to semi-static analysis, as expected,[32] and the same value for ρ0 (120°). The rotational slippage (σρ) about the helix axis remains low at about 16–18° in DPoPC.

Deuterium NMR in bilayers of intermediate thickness (C18:1; DOPC) :

In contrast to the well-defined 2H quadrupolar splittings observed in the spectra from helices in the thinner bilayers (DLPC, DMPC and DPoPC), the 2H NMR spectra of labeled GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC reveal multiple signals for each of the labeled core alanines (Figure S8), suggesting the presence of multiple states for the helix with respect to the DOPC bilayers. For example, the spectra for 2H-labeled A15 and A17 (Figure 2) reveal multiple quadrupolar splittings, including some that overlap closely with the signals observed in DLPC and DMPC. Indeed, detailed examination reveals that two populations are present, representing two orientations of the GWALP23-R8,16 helix in DOPC membranes.

The major population in DOPC is quite different from the transmembrane helix orientation observed in the thinner bilayers. The major population of the GWALP23-R8,16 helix, indicated by the quadrupolar wave shown by the solid black curve in Figure 4A and 4B, sits on the surface of the DOPC bilayer. The surface orientation is indicated by τ0 being ~89° with respect to the bilayer normal (Table 2). Residue A7, furthermore, misses the curve for the helical quadrupolar wave by about 7 kHz (Figure 4A) and is therefore markedly unraveled from the surface-bound core helix.

Weaker signals in the 2H NMR spectra (Figure 2 and Figure S8) represent a minor transmembrane population for the helix that remains embedded in DOPC. This minor orientation follows the trend for decreasing the helix tilt as the bilayer thickens (dashed black curve in Figure 4A), with τ0 following the trend from about 29° in DLPC to 25° in DMPC to 23° in DPoPC and then to about 21° in DOPC (minor population). Yet in DOPC, the now more “buried” arginines cause the major helix population to exit the DOPC bilayer (Table 2, Figure 4A). The DOPC bilayer membrane is a transition environment for the GWALP23-R8,16 helix. This transition of the helix from transmembrane to the surface of DOPC bilayers results in multiple 2H-NMR signals (lower panel of Figure 2 and top panel of Figure S8).

Deuterium NMR in a longer (C20:1; DEiPC) unsaturated lipid:

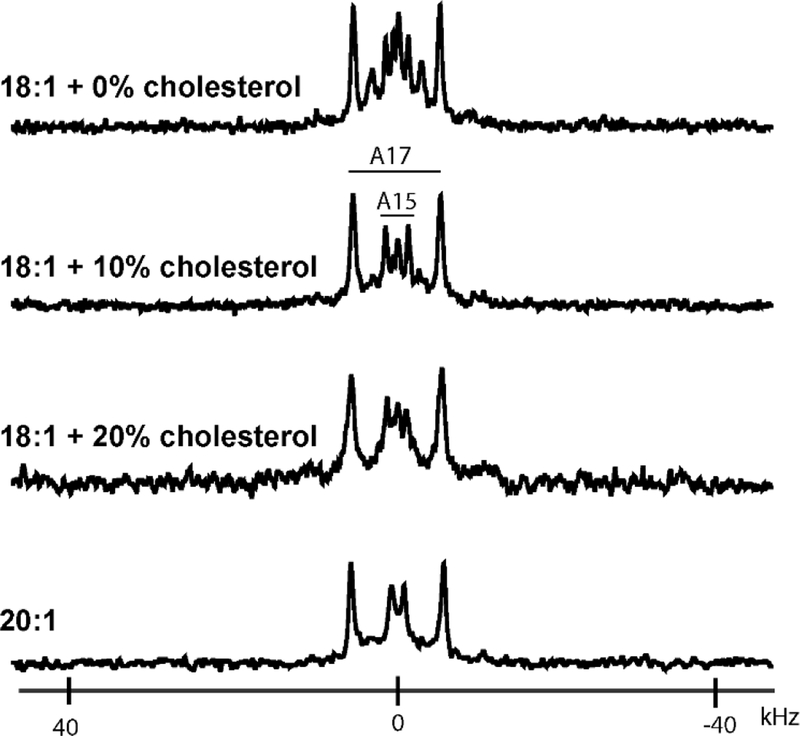

To investigate the helix properties in a thicker bilayer, oriented samples were prepared in a longer unsaturated C20:1 lipid (DEiPC). The 2H NMR spectra of GWALP23-R8,16 in DEiPC bilayers (Figure 3 and Figure S8), display remarkable single-state behavior, as indicated by the presence of just one pair of peaks with a well-defined quadrupolar splitting for each deuterated alanine. The quadrupolar splittings differ from those observed for the transmembrane orientation in DLPC, DMPC or DPoPC lipid bilayers, yet indeed match those of the major surface-bound population observed in DOPC. Interestingly, the minor membrane-embedded population is absent in DEiPC. GALA analysis (Figure 4B) gives a quadrupolar wave showing a helix tilt τ0 of 87° indicating a surface bound orientation. The azimuthal rotation ρ0 of 45° is similar to that of the major surface helix population in DOPC. Modified Gaussian analysis shows further agreement, with similar values of 85° for τ0 and 42° for ρ0 and a low slippage (σρ) value of 25° (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Solid-state 2H NMR spectra of labeled alanines A15 and A17 GWALP23-R8,16 in aligned bilayers of DEiPC (C20:1) or of DOPC with varying amounts of cholesterol. Sample orientation β = 90°; temperature 50 °C.

Addition of cholesterol to DOPC samples:

Cholesterol, a vital component of mammalian cells, influences the physical properties of the cell membrane and its constituent proteins. Previously it was observed that cholesterol modulates the multistate behavior of GWALP23-R12 to favor an interfacial helix, bound at the membrane surface [5]. To examine the effect of cholesterol on the multistate behavior of GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC, 10% or 20% cholesterol was included with DOPC and peptide when the bilayers were formed. Shown in Figure 3 and Figure S8, the addition of even 10% cholesterol decreases the multistate behavior of GWALP23-R8,16 in favor of a single helix, bound at the bilayer surface. The influence of cholesterol parallels that seen with GWALP23-R12 in DOPC.[5] The multiple quadrupolar splittings from 2H-alanines in the spectra of GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC collapse to single pairs of resonances in the presence of 10% cholesterol. Indeed, the spectra for labeled alanines of GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC with 10 or 20% cholesterol are similar to those observed in the thicker bilayers of DEiPC (Figure 3, bottom panel). GALA analysis (Figure 4B and Table 2) reveals an interfacial helix located at the membrane surface when cholesterol is present in DOPC.

Trends for the helix orientations.

Figure 4 summarizes the results for the orientations of the GWALP23-R8,16 helix in the bilayer membranes of varying thickness. Two orientations of the helix are seen, depending on the bilayer membrane environment, with DOPC bilayers being a “transition” environment in which the two helix orientations coexist. Figure 4A illustrates the 2H quadrupolar waves for the transmembrane orientations in DLPC, DMPC, DPoPC and DOPC (minor population), compared to the surface-bound major population in DOPC, which serves as a reference. In similar fashion, Figure 4B illustrates the 2H quadrupolar waves for the helix at the membrane surface of DEiPC or of DOPC with 20% or 10% or 0% cholesterol, where these waves are compared to that of the minor transmembrane population in DOPC without cholesterol, which serves as a reference. Notably, for the surface orientation, residue A7 deviates from the helix in all cases, suggesting that the helix breaks at arginine R8 when bound to a membrane surface. The values for the tilt τ0 and azimuthal rotation ρ0 for the transmembrane and surface orientations are summarized in Table 2. The helix properties were analyzed using both semi-static GALA [33] and modified Gaussian [32, 34] methods, and there is fundamental agreement between the two methods of analysis (Table 2).

For the transmembrane orientation, the helix tilt τ0 shows an expected systematic decrease as the bilayer thickens, from τ0 of about 29° in DLPC to about 21° in DOPC (minor population), where also a major fraction of the helix population begins to exit the bilayer. The helix exit to the membrane surface is then accentuated in the thicker DEiPC bilayer or if cholesterol is present in DOPC; see Discussion. The azimuthal rotation ρ0 about the transmembrane helix axis remains essentially the same in each bilayer (Table 2). As expected for Arg-containing helices, [31] the motional averaging is very low for the transmembrane helix, with the modified Gaussian analysis fitting to about 18° when στ is fixed at 5° (Table 2).

For the helix on the membrane surface, the values of τ0 (88° from the bilayer normal) and ρ0 are essentially the same for all of the bilayer surfaces (Table 2), as should be expected when the head groups remain constant, namely phosphatidylcholine. The azimuthal rotation ρ0 is probably dictated by interactions between the lipid head groups and the arginine side chains of R8 and R16, with residue A7 markedly unraveled from the core helix (Figure 4B). Notable also is the increased dynamic averaging of the surface-bound helix on all of the lipid membranes. The increase in dynamics is reflected by the low value of about 0.55 for Szz in the GALA analysis and by the need to fix the helix wobble at 25° for all of the surface helices in the modified Gaussian analysis (Table 2). (We were unable to obtain modified Gaussian fits when was only 5°.)

Tryptophan Fluorescence Spectroscopy:

The exit of the GWALP23-R8,16 helix from thicker membranes was confirmed by fluorescence emission spectroscopy. The spectra in Figure S4 indicate interfacial indole ring locations in the thinner membranes, with the Trp emission λmax increasing slightly with acyl chain length, from DLPC (337 nm) to DMPC (342 nm) to DPoPC (343 nm). When part of the helix population moves to the bilayer surface, the Trp emission λmax increases further, to an average of 345 nm with DOPC and to 348 nm with DEiPC bilayers (Figure S4), reflecting increasing water exposure for the Trp residues on the surface of the thicker lipid bilayers. The Trp λmax increases still further upon inclusion of cholesterol in the DOPC bilayers (Figure S5), to 352 nm and 354 nm for 10% and 20% cholesterol, respectively, indicating increasingly more solvent exposure for the surface helix when cholesterol is in the bilayer.

Discussion

We have addressed the question of how the relative position of arginine affects the orientation and dynamics of a transmembrane helix. To this end, the model peptide GWALP23-R8,16, with arginines located three residues inside of, respectively, tryptophans 5 and 19, was incorporated into PC bilayers of varying thickness and chain saturation. As background, the parent GWALP23 peptide without arginine adopts a tilted transmembrane orientation with tryptophans 5 and 19 at the membrane interface [29] and about 3–4 residues unravelled at each end of the core helix.[35] Previously we reported that peptide sequence isomers with single arginines R12 or R14 display markedly different behaviors.[10] GWALP23-R14 shows one major state in DOPC or DPPC bilayers, with an apparent average tilt ∼10° greater than GWALP23 and the helix displaced to “lift” the charged guanidinium toward the bilayer surface. By contrast, GWALP23-R12 exhibits multiple states in slow exchange on the NMR time scale. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations revealed about equal populations for a surface-bound state and two distinct transmembrane states for the GWALP23-R12 helix. [10] We now compare the properties of GWALP23-R8,16 in bilayers prepared from lipids of varying hydrophobic thickness, DLPC and DMPC (saturated), and DPoPC, DOPC and DEiPC (unsaturated). At 50°C, the hydrophobic thicknesses of DLPC and DMPC are 20.8 Å and 24.8 Å, respectively,[36] while the DOPC thickness at 45 °C is about 26.2 Å.[37] Despite being four carbons longer than DMPC, DOPC bilayers are only about 1.4 Å thicker due to the presence of the double bond. Based on X-ray scattering measurements of PC lipid vesicles having monounsaturated chains of 18 to 24 carbons.[38], the bilayer thickness changes by about 3.5 Å per two carbons. Derived from these results, the bilayer thicknesses of DPoPC (16:1) and DEiPC (20:1) can be estimated to be approximately 23.5 Å and 30.5 Å, respectively, under similar conditions.

In thinner membranes of DLPC, DMPC and DPoPC, GWALP23-R8,16 forms a transmembrane helix for which the tilt angle from the bilayer normal decreases slightly with increasing bilayer thickness (Figure 4). The helical rotation (ρ0) is essentially constant, showing no dependence upon bilayer thickness. For well-aligned helices with minimal dynamic averaging, some of the backbone CαD quadrupolar splittings may be observed.[31] Interestingly, the CαD quadrupolar splittings signals are observed for A17 of GWALP23 R8,16 in DLPC, DMPC, and DPoPC bilayers (Figure 2).

A 22-residue -helix would be 33 Å long [39], however unwinding of the ends would reduce the overall length. The distance between the backbone Cα of the charged arginine residues, R8 and R16, would only be 12 Å; however as the guanadinium side chain of arginine is able to extend or “snorkel” [40–41] as much as ~3.5 Å to access the membrane-water interface [30, 42], the distance between the positive charges could be up to about 18–19 Å. The thinner bilayers, DLPC, DMPC, and DPoPC, thus could accomodate GWALP23-R8,16 in a stable transmembrane orientation with the Arg charges on either side snorkeling out to reach the polar environment. It is also likely that the peptide will induce bilayer deformation in the vicinity of an Arg residue, to enable stabilizing contacts with phospholipid head groups or water of hydration [30, 43]. For example, the S4 helix of the voltage-gated potassium channel (Kv), with several conserved Arg residues, has been shown to induce 9 Å of local and 2 Å of average bilayer thinning [44]. For an additional adaptation, GWALP23-R8,16 adjusts its tilt with respect to the bilayer thickness, to optimize the Arg guanidinium access to the membrane surface. The helix azimuthal rotation angle by contrast remains fairly constant in each of the three thinner lipid bilayers.

The DOPC bilayer membrane is a transition environment for both GWALP23-R12 and GWALP23-R8,16. These peptides exist in competing orientations in DOPC (Figure 5), including a major surface-bound orientation and at least one minor populated transmembrane orientation. GWALP23-R12 exhibits three states that include a surface population of about 40% occupancy and two equally probable transmembrane states at about 30% each.[10] By contrast, only two states are apparent for GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC, those being a surface population of about 70% occupancy (based on the relative spectral intensities in Figure 3) and transmembrane population of about 30%. If there is a third state for GWALP23-R8,16 in DOPC, it is very minor, much less probable and not apparent from the 2H NMR spectra. In DOPC then, it appears that a tipping point is reached, where the the peptide and the lipids are no longer able to further adapt to the increase in the membrane thickness, and where the transmembrane orientation is now unfavourable compared with a surface orientation.

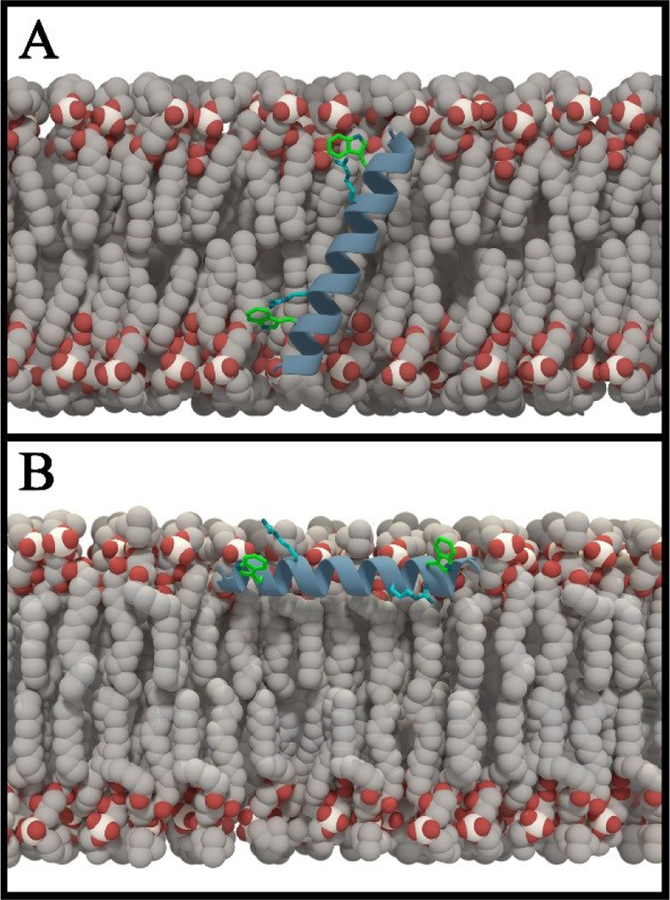

Figure 5.

Pymol models of GWALP23 R8,16: (A) tilted in DMPC, and (B) surface bound in DOPC.

In the thicker membranes of DEiPC, both arginines R8 and R16 have exited the bilayer. The transition from a transmembrane helix to a surface helix is complete. Indeed, the multiple states for GWALP23-R8,16, are not due to the double bond in DOPC, as they are not observed in the longer DEiPC or shorter DPoPC lipids. The thickness of the bilayer, rather than the presence of double bonds, therefore, seems to determine whether the peptide is membrane-embedded, as in DLPC, DMPC and DPoPC, surface bound as in DEiPC, or both, as in the intermediate length lipid, DOPC.

The increased dynamic averaging for the surface-bound helix of GWALP23-R8,16 contrasts with the properties of the antimicrobial peptide MSI-103 in the surface state in several lipid systems [34]. Interestingly, the dynamics of MSI-103 (στ = 0° and σρ = 15°) on a bilayer surface are significantly reduced compared to those of GWALP23-R8,16 (στ = 25° and σρ = 25°; see Table 2). Why are the dynamics of these two surface helices so different? One possibility could be that the notabley amphipathic MSI-103, with several charged lysines on one side of the helix and hydrophobic residues on the opposite face, is very stable in the surface state. By contrast, GWALP23-R8,16, with two arginines, two tryptophans and a leucine close to the same helix face, may find it more difficult to accommodate polar and non-polar side chains on the same side of the helix. As the Arg guanidinium side chains of GWALP23-R8,16 seek the bulk water environment, for example, the Trp indole rings may become frustrated by their preference for the membrane interface. These competing forces may lead to the increased dynamics of the GWALP23-R8,16 helix on a bilayer membrane surface. These features also could explain the helix unraveling at residue seven, observed from the deuterium quadrupole splitting of A7 in GWALP23-R8,16.

In conjunction with the lipid bilayer thickness, cholesterol also regulates the location of the GWALP23-R8,16 helix in DOPC bilayers (Figures 3-4). The issue is important because cholesterol affects a variety of lipid membrane properties, including the bilayer thickness, fluidity, compressibility, water penetration, intrinsic curvature and chain packing.[24, 27, 45] One notes, however, that 10% cholesterol increases the DOPC bilayer thickness by only about 0.5 Å.[37, 46] In spite of the small thickness change, 10% cholesterol (mol:mol, cholesterol:DOPC) drives the residual transmembrane population of the GWALP23-R8,16 helix entirely to the surface of DOPC (Figure 4), indeed to give the helix the same status as on the surface of the thicker DEiPC bilayers. A similar result has been noted for a single-arginine helix, as 10% cholesterol also drives both of the membrane-embedded populations of the GWALP23-R12 helix to the surface of DOPC bilayers.[5] Whether the primary effects involve bilayer thickness, chain packing or other factors, the net result in each case is that cholesterol renders a partially embedded Arg residue less compatible with a lipid bilayer and indeed often dispatches the arginine to the bilayer surface.

Cholesterol also may influence the ability to solvate a partially buried arginine in a membrane-spanning α-helix by means of a so-called “water-defect” by which water penetrates into the bilayer [10, 30, 47]. Molecular simulations were used to study the solvation of a midspan arginine (R694) and its relationship to cholesterol in the membrane spanning domain of gp41 from human immunodeficiency virus [48]. Results from the simulations revealed that fluctuations in membrane thickness and water penetration depth in the cholesterol-containing membranes were localized near the midspan arginine, and the helix tilt angle was more tightly regulated compared to cholesterol-free membranes.

Additional observations concern the relative extents of dynamic wobble and terminal unraveling of the transmembrane and surface helices. Notably, when the helix of GWALP23-R8,16 is embedded as a transmembrane helix spanning a bilayer of DLPC, DMPC, DPoPC or DOPC (Figure 4), then residue A7 along with, by implication, the adjacent to arginine residue R8, fits nicely within the core transmembrane helix. However, when the helix moves to the surface of DOPC or DEiPC (Figure 4), then the 2H quadrupolar splitting for residue A7 deviates substantially from the quadrupolar wave plot for the core helix. The unwinding of alanine A7 from the surface helix is probably attributable to interactions of R8 with lipid heads groups at the membrane helix. The helix unraveling also is reminiscent of the behavior of A7 when histidines H4 and H5 are present, albeit for the transmembrane helix of GWALP23-H4,5.[35]

It is of interest also to compare the width (στ) of the orientation distributions about the mean helix tilt τ0 for the embedded and surface helices. For many transmembrane helices, the extent of the helix wobble is quite low, typically around 5° or 10°. [32, 34–35] The low extent of helix wobble (about 5°) is observed also for the transmembrane helix of GWALP23-R8,16 in each of the relevant bilayer membranes (Table 2). Notably, however, the surface-bound helix of GWALP23-R8,16 can be fit only with a larger σρ of about 25° on the surface of DOPC or DEiPC bilayers (Table 2). The surface environment, apparently, is less restrictive than the transmembrane environment for defining the helix orientation.

Conclusions

A 23-residue largely hydrophobic helix with double arginine residues one-third of the way from each end of the sequence can be accommodated in relatively thin lipid bilayers having from 12- to 16-carbon acyl chains. The helix is significantly tilted, about 21° to 29° from the bilayer normal, depending on the bilayer thickness (Table 2). The extent of dynamic averaging is low, and the rotational preference for the transmembrane helix about its helix axis is independent of the bilayer thickness (Table 2). When thicker bilayers are considered, a transition point is reached in which the helix of GWALP23-R8,16 moves to the membrane surface (see Figure 5). Indeed, in bilayers of DOPC this helix is partially embedded, but the major population is on the surface of DOPC membranes. For the thicker DEiPC bilayer, the helix is entirely on the surface. When 10 mol % cholesterol is included in DOPC bilayers, the helix moves entirely to the surface, an effect attributed to membrane thickening and perhaps other factors such as hydration or acyl chain packing. While unsaturated acyl chains influence the membrane fluidity, they appear not to influence directly the lipid interactions with the peptide helix per se. Overall, these results reveal interesting details of the molecular interactions between arginine-containing helices and lipid-bilayer membranes with and without cholesterol.

Experimental Section

Peptide synthesis:

[D4]L-alanine from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA) was modified with an N-terminal Fmoc protecting group and was recrystallized from Ethyl acetate/hexane (80:20). Other protected amino acids and Rink amide resin, including arginine whose side chain was additionally protected with 2,2,4,6,7-pentamethyldihydrobenzofuran-5-sulfonyl (Pbf) protecting group, were purchased from Anaspec (Freemont, CA), Bachem (Torrance, CA), Sigma Aldrich and NovaBiochem (MillaporeSigma, Burlington, MA). Peptides were synthesized on a model 433A solid-phase peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems/Thermo Fisher Sci.; Foster City, CA) using a 0.1 mmol scale FastMoc chemistry. Two deuterium-labeled alanines were incorporated per peptide, with 50% and 100% isotope abundance levels, to distinguish the 2H NMR signals based on relative intensities. Following cleavage from the resin using a trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) based cocktail, the resulting C-termini amidated peptides were precipitated with methyl-tert-butyl-ether/hexane (50:50). The peptides were purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a 5 μm octylsilica Zorbax SB-C8 or SB300-C3 column (9.4 mm × 250 mm) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), as described in [32, 49]. The molecular mass of peptide and distributions of deuterium were confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Figure S1).

Solid-state NMR sample preparation:

Mechanically aligned samples for solid-state NMR spectroscopy (peptide/lipid, 1:60, mol/mol) were prepared using both saturated and unsaturated lipids, 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLPC), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), 1,2-dipalmitoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (ΔCis-9) (DPoPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (ΔCis-9) (DOPC) or 1,2-dieicosenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (ΔCis-11) (DEiPC) from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Peptide/lipid films were hydrated using deuterium-depleted water (Cambridge Isotope Labs, Tewksbury, MA) to achieve 45 % w/w hydration, as described previously.[29, 49].

Solid-state 31P NMR:

Bilayer alignment for each sample was confirmed by 31P NMR at 50 °C on a Bruker Avance 300 spectrometer at both β=0° (bilayer normal parallel to magnetic field) and β=90° macroscopic sample orientations. Measurements were performed in a Doty 8 mm wideline probe (Doty Scientific Inc., Columbia, SC) with broadband 1H decoupling using the zgpg pulse program, a 6 μs 90° pulse, and a recycle delay time of 5 s. Before Fourier transformation, an exponential weighting function with 100 Hz line broadening was applied. The chemical shift was referenced externally to 85% phosphoric acid at 0 ppm.

Solid-state 2H NMR:

Deuterium NMR spectra were recorded at 50 °C with both sample orientations and a quadrupolar echo pulse sequence with full phase recycling [50], a 120 ms recycle delay, 3.2 μs pulse length, and 105 μs echo delay. Between 0.7 and 1.5 million scans were acquired for each 2H NMR experiment, and an exponential weighting function with 100 Hz line broadening was applied prior to Fourier transformation.

Semi-static GALA and Modified Gaussian Analyses:

The individual NMR signals for GWALP23-R8,16 were assigned and analyzed by the semi-static “geometric analysis of labeled alanines” (GALA) method to determine the helix orientation. The GALA method is based on three adjustable parameters, the average tilt (τ0) of the helix axis, the average azimuthal rotation (ρ0) about the helix axis, and the principal order parameter (Szz). [3, 33, 51–52] The εll angle was fixed at 59.4°. A modified Gaussian approach based on τ0, ρ0, a distribution width σρ, and a fixed στ, was also employed as previously described.[32, 34] When available, the 2H quadrupolar splitting from the backbone C deuteron of residue A17 was included along with the data points from the deuterated alanine side chains.

Circular Dichoism (CD) and Fluorescence Spectroscopy:

Small unilamellar lipid vesicles with incorporated peptides (1:60 peptide:lipid) were prepared by sonication. Peptide concentrations, determined by ultraviolet−visible spectroscopy, were in the 100 μM range. For CD spectra, six to twelve scans were recorded and averaged on a Jasco J-1500 spectropolarimeter, using a 1 mm cell path length, a 1.0 nm bandwidth, a 0.1 nm slit, and a 20 nm/min scan rate. Vesicle solutions for fluorescence experiments were prepared by 1/10 dilution with water, of the samples previously prepared for CD spectroscopy. Samples were excited at 280 nm and emission spectra were recorded between 300 and 450 nm using the Jasco J-1500 spectropolarimeter. Two to four scans per sample were recorded and averaged.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Deuterium quadrupolar splittings (kHz) for 2H-labeled alanines in GWALP23-R8,16 in bilayer membranesa

| Lipid | Alanine Position | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 17 | |

| DLPCb | 39.6 | 35.6 | 37.2 | 32.8 | 8.0 | 20.0 |

| DMPCb | 34.8 | 35.0 | 30.8 | 31.0 | 6.0 | 17.3 |

| DPoPCb | 30.0 | 34.0 | 30.0 | 30.4 | 5.0 | 16.1 |

| DOPC (minor) | 27 | 31 | -- | 26.6 | 1.6 | 12.8 |

| DOPC (major) | 17.2c | 23.2 | 20.4 | 9.2 | 5.8 | 22.6 |

| DOPC+10% | 16.0c | 21.2 | 20.0 | 8.2 | 5.8 | 22.8 |

| DOPC+20% | 16.8c | 22.2 | 19.0 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 23.8 |

| DEiPC | -- | -- | 21.6 | 6.5 | 3.3 | 24.0 |

Sample orientation, β = 0°; 50 °C.

Quadrupolar splitting also observed for the backbone Cα deuteron of A17: 128 kHz (DLPC); 114 kHz (DMPC); 105 kHz (DPoPC).

Data point does not fit the helix in Figure 4.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) Molecular and Cellular Biosciences grant 1713242 and by the Arkansas Biosciences Institute. The peptide, NMR, and mass spectrometry facilities were supported in part by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant GM103429.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This manuscript has been accepted after peer review and appears as an Accepted Article online prior to editing, proofing, and formal publication of the final Version of Record (VoR). This work is currently citable by using the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) given below. The VoR will be published online in Early View as soon as possible and may be different to this Accepted Article as a result of editing. Readers should obtain the VoR from the journal website shown below when it is published to ensure accuracy of information. The authors are responsible for the content of this Accepted Article.

Supporting information and ORCID(s) from the author(s) for this article are available on the WWW under https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7104-8499 and https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0676-6413.88

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

[References

- [1].McKay MJ, Afrose F, Koeppe RE 2nd, Greathouse DV, Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2018, 1860, 2108–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sanders CR, Myers JK, Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 2004, 33, 25–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gleason NJ, Vostrikov VV, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE 2nd, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 1692–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Martfeld AN, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE 2nd, J Biol Chem 2016, 291, 19146–19156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thibado JK, Martfeld AN, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE, Biochemistry 2016, 55, 6337–6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Allen TW, J. Gen. Physiol 2007, 130, 237–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].MacCallum JL, Bennett WF, Tieleman DP, Biophys J 2008, 94, 3393–3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Roux B, J Gen Physiol 2007, 130, 233–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Strandberg E, Killian JA, FEBS lett 2003, 544, 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vostrikov VV, Hall BA, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE 2nd, Sansom MS, J Am Chem Soc 2010, 132, 5803–5811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hristova K, Wimley WC, J Membr Biol 2011, 239, 49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vorobyov I, Olson TE, Kim JH, Koeppe RE, Andersen OS, Allen TW, Biophys J 2014, 106, 586–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhou FX, Merianos HJ, Brunger AT, Engelman DM, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98, 2250–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bezanilla F, Physiol Rev 2000, 80, 555–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Catterall WA, Neuron 2000, 26, 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yarov-Yarovoy V, DeCaen PG, Westenbroek RE, Pan CY, Scheuer T, Baker D, Catterall WA, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, E93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sula A, Wallace BA, J Gen Physiol 2017, 149, 613–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stuhmer W, Conti F, Suzuki H, Wang XD, Noda M, Yahagi N, Kubo H, Numa S, Nature 1989, 339, 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Catterall WA, J Physiol 2012, 590, 2577–2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Freites JA, Tobias DJ, J Membr Biol 2015, 248, 419–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Okamura Y, Fujiwara Y, Sakata S, Annu Rev Biochem 2015, 84, 685–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Guo J, Zeng W, Chen Q, Lee C, Chen L, Yang Y, Cang C, Ren D, Jiang Y, Nature 2016, 531, 196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Frey L, Hiller S, Riek R, Bibow S, J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140, 15402–15411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang ST, Kreutzberger AJB, Lee J, Kiessling V, Tamm LK, Chem Phys Lipids 2016, 199, 136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rog T, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Vattulainen I, Karttunen M, Biophys J 2007, 92, 3346–3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Weisz K, Grobner G, Mayer C, Stohrer J, Kothe G, Biochemistry 1992, 31, 1100–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zheng H, Liu W, Anderson LY, Jiang QX, Nat Commun 2011, 2, 250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vostrikov VV, Grant CV, Daily AE, Opella SJ, Koeppe RE 2nd, J Am Chem Soc 2008, 130, 12584–12585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vostrikov VV, Daily AE, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE 2nd, J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 31723–31730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vostrikov VV, Hall BA, Sansom MS, Koeppe RE 2nd, J Phys Chem B 2012, 116, 12980–12990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vostrikov VV, Grant CV, Opella SJ, Koeppe RE 2nd, Biophys J 2011, 101, 2939–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sparks KA, Gleason NJ, Gist R, Langston R, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE 2nd, Biochemistry 2014, 53, 3637–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].van der Wel PC, Strandberg E, Killian JA, Koeppe RE 2nd, Biophys J 2002, 83, 1479–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Strandberg E, Esteban-Martin S, Ulrich AS, Salgado J, Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1818, 1242–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Afrose F, McKay MJ, Mortazavi A, Suresh Kumar V, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE 2nd, Biochemistry 2019, 58, 633–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kucerka N, Nieh MP, Katsaras J, Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1808, 2761–2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pan J, Tristram-Nagle S, Kucerka N, Nagle JF, Biophys J 2008, 94, 117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lewis BA, Engelman DM, J Mol Biol 1983, 166, 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1951, 37, 205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Killian JA, von Heijne G, Trends Biochem Sci 2000, 25, 429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Strandberg E, Morein S, Rijkers DT, Liskamp RM, van der Wel PC, Killian JA, Biochemistry 2002, 41, 7190–7198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ojemalm K, Higuchi T, Lara P, Lindahl E, Suga H, von Heijne G, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 10559–10564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li S, Su Y, Luo W, Hong M, J Phys Chem B 2010, 114, 4063–4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Doherty T, Su Y, Hong M, J Mol Biol 2010, 401, 642–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].de Meyer F, Smit B, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 3654–3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hung W-C, Lee M-T, Chen F-Y, Huang HW, Biophys J 2007, 92, 3960–3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schow EV, Freites JA, Cheng P, Bernsel A, von Heijne G, White SH, Tobias DJ, J Membr Biol 2011, 239, 35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Baker MK, Gangupomu VK, Abrams CF, Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1838, 1396–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Gleason NJ, Vostrikov VV, Greathouse DV, Grant CV, Opella SJ, Koeppe RE 2nd, Biochemistry 2012, 51, 2044–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Davis JH, Jeffrey KR, Valic MI, Bloom M, Higgs TP, Chem. Phys. Lett 1976, 390–394.

- [51].Strandberg E, Esteban-Martin S, Salgado J, Ulrich AS, Biophys J 2009, 96, 3223–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Thomas R, Vostrikov VV, Greathouse DV, Koeppe RE 2nd, Biochemistry 2009, 48, 11883–11891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.