Abstract

Considering the advantages and disadvantages of biomaterials used for the production of 3D scaffolds for tissue engineering, new strategies for designing advanced functional biomimetic structures have been reviewed. We offer a comprehensive summary of recent trends in development of single- (metal, ceramics and polymers), composite-type and cell-laden scaffolds that in addition to mechanical support, promote simultaneous tissue growth, and deliver different molecules (growth factors, cytokines, bioactive ions, genes, drugs, antibiotics, etc.) or cells with therapeutic or facilitating regeneration effect. The paper briefly focuses on divers 3D bioprinting constructs and the challenges they face. Based on their application in hard and soft tissue engineering, in vitro and in vivo effects triggered by the structural and biological functionalized biomaterials are underlined. The authors discuss the future outlook for the development of bioactive scaffolds that could pave the way for their successful imposing in clinical therapy.

Keywords: Bioactive scaffolds, Bone tissue engineering, Polymeric biomaterials, Bioceramics, Bioprinting

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Recent trends in single-, composite-type and cell-laden scaffolds are discussed.

-

•

3D constructs dedicated for hard and soft tissue application are reviewed.

-

•

Scaffolds for delivering growth factors, cytokines, bioactive ions, genes, drugs, etc.

-

•

In vitro and in vivo effects triggered by the functionalized biomaterials are revealed.

-

•

Future outlook for the development of bioactive scaffolds is summarized.

Abbreviations

- 2D

two-dimensional

- 3D

three-dimensional

- 3T3

fibroblasts cells

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ADMSCs

adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- BG

bioactive glass

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- BMP-2

bone morphogenic protein-2

- BMSCs

bone marrow stromal cells

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CPC

calcium phosphate cement

- CSH

calcium sulphate hydrate

- CT

computed tomography

- dECM

decellularized extracellular matrix

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- EBM

electron-beam melting

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EPCs

endothelial progenitor cells

- FHAp

fluorhydroxyaptite

- FDM

fused deposition modelling

- GF

growth factor

- GO

graphene oxide

- HA

hyaluronic acid

- HAp

hydroxyapatite

- hADSCs

human adipose-derived stem cells

- hAVICs

human aortic valvular interstitial cells

- hBMSCs

human bone marrow-derived stem cells

- hDFCs

human dental follicle cells

- hEKCs

human embryonic kidney cells

- hFOBCs

human fetal osteoblast cells

- hNDFs

human neonatal dermal fibroblasts

- hTMSCs

human inferior turbinate-tissue derived mesenchymal stromal cells

- hUCMSC

human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells

- hUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- hUVSMCs

human umbilical vein smooth muscle cells

- LBM

laser beam melting

- MBG

mesoporous bioactive glass

- MC3T3-E1

osteoblast precursor cell line

- MG-63

human osteosarcoma cell line

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cells

- MWCNTs

multi-wall carbon nanotubes

- NHEKs

normal human epidermal keratinocytes

- oMSCs

ovine mesenchymal stem cell

- PAA

poly(acrylic acid)

- PCL

ε-poly(caprolactone)

- PEG

poly(ethylene glycol)

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- PEO

poly(ethylene oxide)

- PES

polyethersulphone

- PET

polyethylene terephthalate

- PGA

poly(glycolic acid)

- PGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PHB

polyhydroxybutyrate

- PHBV

poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)

- PHEMA

polyhydroxy ethyl methacrylate

- PHPMA

N-(2-Hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide

- PLC

poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone)

- PLGA

poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid

- PLA

poly(lactic acid)

- PLLA

poly(l-lactic acid)

- P(LLA-CL)

poly(l-lactic acid-co–caprolactone)

- PMMA

poly(methyl methacrylate)

- PP

polypropylene

- PU

polyurethane

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

- PVAc

polyvinyl acetate

- rBMSC

rat bone mesenchymal stem cells

- rCCs

rabbit corneal cells

- rGO

reduced graphene oxide

- rhBMP-2

recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- SDSCs

synovium-derived stem cells

- SH-SY5Y

human-derived cells used as models for neuronal function and differentiation

- SiHAp

silicate containing hydroxyapatite

- SLA

stereolithography

- SLS

selective laser sintering

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor-β1

- TPU

thermoplastic polyurethane

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- β-TCP

β-tricalcium phosphate

1. Introduction

Implantable 3D scaffolds are used for restoration and reconstruction of different anatomical defects of complex organs and functional tissues. The scaffolds provide a template for the reconstruction of defects while promoting cell attachment, proliferation, extracellular matrix generation, restoration of vessels, nerves, muscles, bones, etc. Scaffolds are three-dimensional (3D) porous, fibrous or permeable biomaterials intended to permit transport of body liquids and gases, promote cell interaction, viability and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition with minimum inflammation and toxicity while bio-degrading at a certain controlled rate. The artificial material substituted for tissue grafts is called alloplastic. The alloplastic bioactive scaffolds ensure not only the mechanical support of the tissue but also serve as a delivery vehicle for bioactive molecules (cytokines, inhibitors, drugs, antibiotics, etc.) and templates for attaching genetically transduced cells establishing new centres for tissue regeneration and morphogenesis. Simultaneously, 3D scaffolds can be used as tissue models replicating the structural complexity of the living tissues. For that reason, not only the biomaterial used, but also the macro-, micro-, and nano-architecture of the scaffolds are of prime importance.

Based on their chemical composition, biomaterials used for 3D scaffolds are classified into metals, ceramics and glass-ceramics, natural and synthetic polymers, and composites. Recently, the focus is put towards biodegradable biomaterials that do not need to be explanted from the organism. Table 1 summarizes the main classes of biomaterials used in 3D scaffold production together with their common application and synthesis methods. Each biomaterial has specific chemical, physical, and mechanical properties, the ability for processing and control of 3D shapes and geometry. The selection of production technique depends on the specific requirements for the scaffold, material of interest, and machine limitation [1]. The integration of computer-aided design (CAD) software and rapid prototyping proposes the ability to produce objects with macro- (overall size and shape), micro- (pore size, shape, interconnection, and distribution) and sometimes nanoarchitecture (nano-roughness, topology, etc.) control of highly complex biomedical devices. Using patient data, the design of the scaffold could be individualized by preparing special 3D model with certain porosity or structures for vasculature that is compatible with multiple biomaterials and cells. The use of 3D printing has revolutionized the development of regenerative medicine and pharmaceutical field.

Table 1.

Biomaterials for 3D scaffolds production together with their common application and fabrication methods.

| Class biomaterial | Application | Fabrication | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomaterial for 3D scaffolds | CERAMICS | (HA, β-TCP, α-TCP, ZrO2, TiO2, porous bioglass, calcium silicate, calcium sulphate, etc.) | Hard tissue replacement Orthodontic application |

|

|

| POLYMERS | Natural | Proteins(silk, collagen, gelatin, fibrinogen, actin, keratin) | Connective and hard tissue application |

|

|

| Polysaccharides(alginate, chitosan, cellulose, dextran, chitin, glycosaminoglycan, hyaluronic acid, agarose) | Decellularized living tissues/organs Drug delivery Hard and soft tissue on applicants |

||||

| Polynucleotides(DNA, RNA) | Gene therapy | ||||

| Synthetic | Degradable (polyesters, polyorthoesters, polylactones, polycarbonates, polyanhydrides, polyphosphazenes, etc.) | Drug-delivery systems Implants |

|

||

| Non-degradable(PE, PTFE, PMA, PAA, PU, polyether, polysiloxanes, etc.) | Orthopaedic implants | ||||

| METALS & ALLOYS | (Co–Cr, Ti, Ti–6Al–4V, stainless steel etc.) | Orthopaedic and dental application Artificial hearing |

|

||

| COMPOSITES | Blends of polymers and ceramics/metals | Orthopaedic and dental application |

|

||

Recently, much research has been done to develop a variety of novel biomaterials and composites with enhanced cell viability, cell proliferation, and printability. For additional modification, biomimicry approach arranging different cellular components (growth factors, hormones, ECM proteins, etc.) to mimic living tissue is used to enhance cell signalling or ECM formation [2]. Moreover, biomaterial scaffolds are used for delivering therapeutic agents like proteins, growth factors, drugs, etc. and the anchorage of these substances to the scaffold is of high importance for loading. As biomaterial-cell interactions are key to cell viability, proliferation and differentiation, characteristics of biomaterials such as surface chemistry, charge, roughness, reactivity, hydrophilicity, and rigidity need to be considered. With continuous research and progress in biomaterials used in medical implants, the goal of this review is to discuss recently developed implantable scaffold materials for different tissues and highlight the advances in in vitro and in vivo biological regeneration.

2. 3D scaffold requirements

A large number of scaffolds with various macro- and microarchitectures from different biomaterials have been reported in the literature. The design of a scaffold includes mechanical (stiffness, elastic modulus, etc.), physicochemical (surface chemistry, porosity, biodegradation, etc.), and biological (cell adhesion, vascularization, biocompatibility, etc.) requirements as well as considerations concerning sterilization and commercial feasibility. To improve the bioactivity and functionality of 3D scaffolds acting as synthetic frameworks or matrices, the shape, size, strength, porosity, and degradation rate are readily controlled. The design of these regeneration templates has evolved over the past years. To repair the damaged tissue, the scaffold should be designed and fabricated in a manner resembling the anatomical structure and mimicking the function and biomechanics of the original tissue. The 3D scaffold should temporarily withstand the external loads and stresses caused by the formation of the new tissue while preserving mechanical properties close to that of the surrounding tissue. It was demonstrated that the tissue-specific mechanical characteristics, in particular, stiffness, could control the differentiation of MSCs [3]. Simultaneously, the scaffold designs such as sponges, meshes, foams, etc., are able the control biodegradation as a key factor in tissue engineering. The degradation of biomaterials could be surface or bulk. In contrast to bulk degradation that breaks the internal structure of the material, the surface degradation maintains the bulk structure. The rate of degradation should match the tissue growth without separation of toxic byproducts. The degradation of a biomaterial could be achieved by physical, chemical, biological or combined processes influencing the biocompatibility of the 3D scaffold. For example, incorporating different biodegradable components in the construct triggers hydrolytic degradation while processes such as enzymatic digestion and cell-driven degradation biologically change the implant material. When the application of a scaffold does not require a complete degradation (for example in articular cartilage repair) permanent (non-degradable) or semi-permanent scaffolds could be used. When implanted in body right, toxic, immunological or foreign body responses should not occur which prove the scaffold biocompatible. The surface properties of a scaffold should also be designed in such a way that to facilitate cell attachment, homogeneous distribution, proliferation and cell-to-cell contacts. The scaffold geometry should maintain the porous or fibrous design and provide high surface-to-volume ratio for cell attachment and tissue development. Nanostructured surfaces demonstrate high surface energy as opposed to polished materials that result in enhanced hydrophilicity and, therefore, improved adhesion of proteins and cell attachment. For metal and ceramic scaffolds, the smaller grain size not only increases the mechanical strength but was found to be more favourable in terms of attachment and proliferation of osteogenic cells [4]. Therefore, the scaffold with its topography and mechanical features controls cellular behaviour. When seeded in 3D scaffolds, cells need to be urged to regain typical in vivo morphology. The process of regeneration also requires the development of interconnected neurovascular networks between the mature and surrounding tissue. On one hand, the scaffold design should make allowance for vascular remodelling as tissue mature so that nutrients, oxygen and other soluble factors could reach all embedded cells while the metabolic wastes are constantly removed. On the other hand, nerve fibres are spatially closely associated with cells that express receptors for neuropeptides and should be simultaneously developed with the new tissue to regulate homeostasis. Usually, the distribution of peripheral nerves and blood vessels follows each other in human body development because they are anatomically coupled and influence the growth and development of each other [5]. Since it is still hard to regulate multi-tissue types development, autologous neurovascular bundles integrated by microsurgery during scaffold implantation is a potential concept [6] for improving scaffold performance.

To support and accelerate the endogenous healing process, especially in extensive or irreversible damages, different strategies for administration of stem cells (after in vitro expanded) alone or in combinations with natural or synthetic scaffolds are proposed. Stem cells from different sources (bone marrow, adipose, muscle tissue, lung, umbilical cord, etc.) are usually used as therapeutic rely on because of their ability to maintain homeostasis in healthy tissues and differentiate when activated under a reparative response or disease. When using tissue-specific stem cells, they are able to regenerate the tissue from which they are isolated. After the injury, a cascade of biological events such as stem cell migration, chemokine and growth factor secretion occurs to repair the destroyed tissue. These processes could be mimicked, stimulated and controlled by adding a variety of bioactive moieties such as growth factors, peptides, genes, aptamers (single strength oligonucleotides), antibodies, drugs, or even ECM. These substances are chemically or physically (by electrostatic forces, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonds) decorated to the scaffold. In that way, the engineered complex scaffolds mimic natural signalling and repair events and generate suitable microenvironment for adhesion, proliferation, differentiation of stem cells that regenerate the tissue.

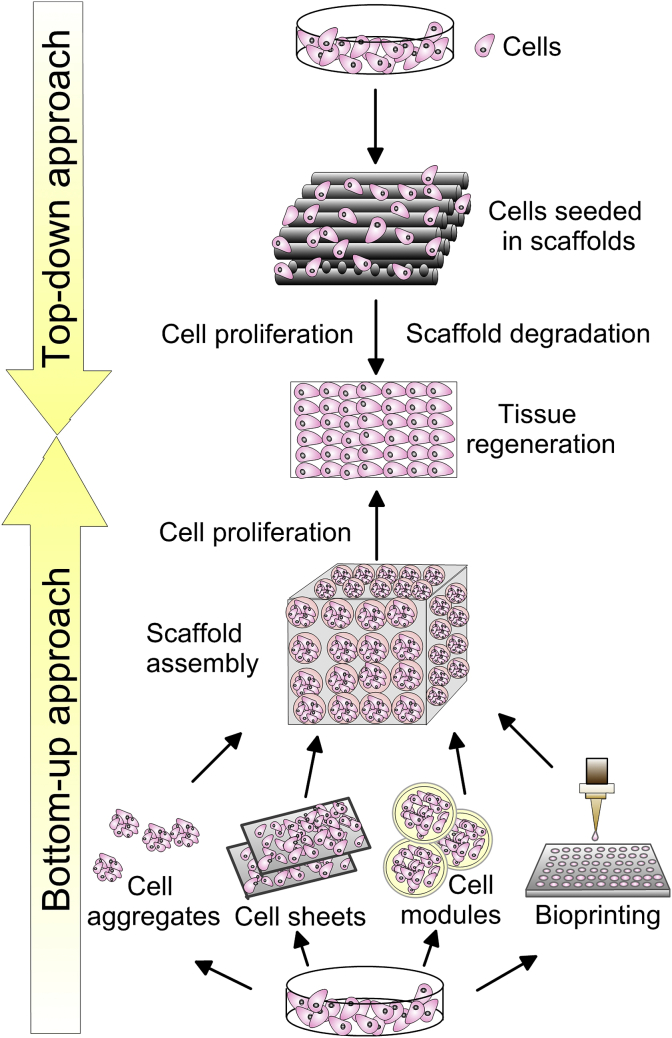

3. Types of 3D scaffolds based on their geometry

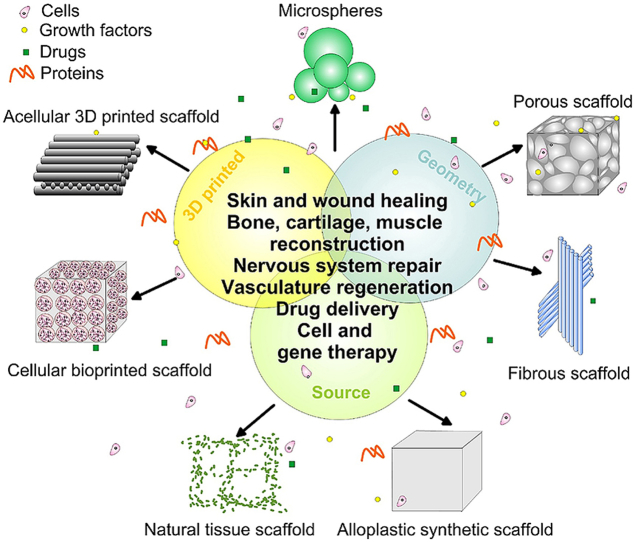

Scaffolds of various biomaterials cover a wide range of applications (Fig. 1). The classification of these complex constructs could be based on their geometry or material source.

Fig. 1.

A general scheme of various types of 3D scaffolds together with their applications in tissue engineering.

When the geometry is used to categorize 3D scaffolds, the available biological constructs are:

3.1. Porous scaffolds

Sponge or foam porous scaffolds usually contain interconnected pore structure (orientated or random) that is highly useful in bone re-growth, vascularization and ECM deposition. Because of the high physical surface, such scaffolds provide improved gas and nutrients transport through the channel network. However, increased pore interconnectivity is required for peripheral nerve and blood vessels growth without scarifying the mechanical properties of the scaffold. Otherwise, the cell in-growth and flow of nutrients will be prevented. If the pores are too small, the cellular penetration, ECM deposition, and neovascularization could be prevented. Ideally, the interconnected porous structure should consist of 90% porosity [7] which could substantially influence the resulting mechanical properties. However, the ideal size of pores for specific cells and tissues varies substantially [8]. For example, pores with 200–400 μm size were found to be effective for bone tissue formation [9], while 50–200 μm pores were suitable for smooth muscle cell growth [10]. Scaffolds with pore sizes between 10-44 and 44–75 μm enable accommodation only of fibrous tissue [11]. As a rule, pores with sizes greater than 100 μm enable tissue growth and vascularization, whereas micro- (less than 2 nm) and mesopores (2–50 nm) promote cell adhesion and resorbability at controllable rates [12]. The pores that are excessively large in size (more than 400 μm) decrease the cell-to-cell contact ratio since the cells experience two-dimensional (2D) growth pattern on the substrate rather than a 3D organization [6]. The special properties of porous scaffolds could be obtained by using methods capable of applying control over pore sizes. Except for the conventional freeze-drying and solvent casting/particulate leaching techniques, fabrication methods with enhanced control over the porosity are the inverse opal hydrogelation which uses colloidal particles as templates for obtaining ordered macroporous scaffolds or cryogelation utilizing frozen solvent crystals as interconnecting porogen [13].

3.2. Fibrous scaffolds

Fibrous scaffolds from different biodegradable polymers such as PCL [14], PLA [15], PLGA [16], gelatin [17], cellulose [18], silk fibroin [19] have been successfully prepared. Fibres possess the desired properties as scaffolds for skin, cartilage, ligament, bone, muscle, vein and vehicles for drugs, DNA and proteins [20]. Nanofibres as scaffolds are found to be more favourable biomaterials than micro fires because the nanosize provokes cell to obtain typical in vivo morphology. Nanofibres have the potential to provide guiding alignment for neurite growth by establishing topographical clues affecting cell differentiation and fate [21]. These nanofibres mimic the structure and properties of the extracellular matrix and because of their high aspect ratio, porosity, and surface-to-volume ratio, they induce greater cellular attachment than microfibres [22]. The nanostructure may help the rapid diffusion of encapsulated substances and cell infiltration [23]. When cultured on smaller fibres (283 nm) of polyethersulphone (PES) with laminin (protein of ECM, a major component of the basal lamina), rat neural stem cells showed 40% increase in oligodendrocyte differentiation and 20% increase on larger fibres (749 nm) [24]. Commonly used techniques for fabrication of nanofibres are electrospinning, self-assembly, phase separation, and solid free-form fabrication. In electrospinning, by applying electrical field, the ejected material from the syringe pumps forms fibres from nanometers to several micrometres in size producing fibrous scaffolds. During electrospinning high voltage is imposed between the spinneret and the ground collector to thinner the filaments. In order to have stable fibres, polymers with enhanced chain entanglement such as PCL, PLLA, PLGA, and polymer-containing composites, are used. The method has high loading and encapsulation capacity of small molecules and drugs [25]. Phase separation technique separates phases through cooling or non-solvent exchange of heterogeneous fibre structures with little control over diameter and orientation of fibres whereas the self-assembly process autonomously organizes components into nanofibre structures. The phase separation method suffers from drawbacks such as limited material selection and inadequate resolution while self-assembly requires careful molecular design because of the complex mechanism of synthesis. Recently, Yao et al. proposed the production of scaffolds using thermally-induced self-agglomeration of short individual electrospun nanofibres and tiny nanofibre pieces in ethanol/water/gelatin (4/2/1) solution followed by freeze-drying [26]. The hierarchical structure consisted of random overlaid PLC/PLA fibres with a diameter ranging from 150 nm to 2 μm, pores from sub-micron to around 300 μm, and about 96% porosity. It was also found that the aligned fibres are able to direct the tissue growth [27] while random fibres demonstrate improved stiffness in all directions [28]. Yin et al. discovered that aligned PLLA scaffolds induced endogenic differentiation in MSCs while the cells cultured on randomly orientated fibres displayed enhanced osteogenic differentiation [29]. These facts provide inside into development of fibrous scaffold design with smart functionalization in interfacial tissue engineering. For that reason Cai et al. developed dual-layer aligned random nanofibrous scaffolds of electrospun silk fibroin-P (LLA-CL) that effectively augmented tendon-to-bone integration and improved gradient microstructure formation [30]. However, the lack of specific functional groups in synthetic nanofibres requires functionalization by attaching different ligands (such as molecules, proteins, ceramics, etc.). Mixed fibre mesh scaffolds provide the opportunity to develop constructs with enhanced properties (biomechanical, physicochemical and biological) in comparison to the properties of individual scaffolds. For example, when nanofibre-reinforced composites are used, higher mechanical strength than traditional unfilled composites could be obtained [31]. Nonetheless, conventional fibre scaffolds suffer from some disadvantages like limited thickness and small pore size.

3.3. Microsphere/microparticle scaffolds

These scaffolds are intensively used in advanced applications such as gene therapy, drug and growth factor delivery in a controlled fashion [32] while demonstrating a certain degree of site-specific targeting [33]. Bioactive moiety-delivery is determined by the ability of the scaffold to control and trigger the substance release in a smart manner through the interaction with bio-molecular stimuli [34]. Polymers with low molecular weight demonstrate rapid drug release, whereas high molecular weight microspheres achieve slower release [35]. Embedded within 3D scaffold as building blocks, microspheres are capable of a cumulative release of encapsulated bioactive substances [36]. Different methods such as solvent vapour treatment, solvent/non-solvent sintering, oil-in-water dispersion, selective laser sintering (SLS) are used for the production of microspheres and microsphere-based 3D scaffolds [37]. The first three methods sinter polymeric microspheres at ambient temperatures to make porous matrices for drug delivery or cell seeding. The polymerization is conducted in heterogenous (two- or multi-phase) systems where a monomer-rich phase is suspended in a solvent-rich phase. During or after polymerization, aggregation, coalescence or crosslinking of the formed microspheres/microparticles are used. The SLS is an additive manufacturing technique for fabrication of complex-shaped scaffolds without using moulds or preforms. The laser beam is the heating source for selective sintering of the powder material (metal, polymer, ceramic, composite) according to the predetermined model geometry. An advantage of the sintered porous structure is the ability to form a 3D porous structure suitable for bone regeneration [38]. For example, lovastatin microparticles in polyurethane scaffold were found to release lovastatin stimulating expression of BMP-2 growth factor in osteoblast cells in 14 days period [39] thus combining better cellular adhesion and controlled delivery of active biomolecules. However, cells could not survive as long as they are more than a few hundred μm away from blood vessels. Otherwise, gases, nutrients and soluble substances should be supplied by slow diffusion which may cause delayed new tissue formation or cell necrosis [40]. To encourage vascularization of an appropriately designed scaffold, three main approaches are applied: 1) functionalization with VEGF, 2) seeding with endothelial cells, and 3) adding angiogenic gene carrying vectors or hypoxia mimic agents [41]. Using the first approach, simultaneously loaded PLGA microspheres with BMP-2 and gelatin hydrogel with VEGF onto PP scaffold have been shown to successfully induce both enhanced bone formation and increased vascularization in rat bone in vivo [42].

3.4. Solid free-form scaffolds

In general, most conventional techniques for scaffold production are incapable of creating complex scaffolds with precisely controlled microarchitecture and properties [43]. 3D scaffolds with controlled architecture and reproducible properties are created by stacking CAD/CAM produced 2D shapes. After preparing 2D models, they are directly transformed into STL files and transmitted to the additive manufacturing equipment. The whole 3D scaffold is obtained by successive printing of 2D layers. The process includes precise X-Y-Z positioning system, automated material-fed system, and computer-based software for operational control. This allows high precision in spatial parameters (from mm to nm) of geometrically complex objects, controlled pore size and interconnectivity, and enhanced productivity of a wide range of biomaterials. The computer-aided method allows creating scaffolds incorporating patient-specific information in a uniquely designed micro-environment. The data for tissue geometry can derive from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) that allow for reconstruction in the 3D model (reverse modelling) [44]. Derived from the 3D medical image of the defect, this fabrication technique is able to create patient-specific scaffold with the exact geometry of the defect. The individualized scaffold design provides production of more accurate and perfectly fitting implants together with decreased fabrication time. However, the accuracy of the model depends on the resolution of the device for image acquisition, 3D printing technology, and machine used.

The additive manufacturing technologies could be classified into scaffold-based (subdivided into cellular and acellular) and scaffold-free 3D printing [45]. Cellular 3D printing could be sub-categorized as extrusion-based, droplet-based, laser-based (that will be later explained), and stereolithography (SLA) while acellular printing can be sub-divided into SLS, selective laser melting (SLM), electron-beam melting (EBM), fused deposition modelling (FDM), and melt electrospinning writing [46]. SLA or vat polymerization is a process where a photoreactive resin is selectively cured while a platform moves the scaffold after each new layer is formed. The method is used for the synthesis of polymer, ceramic and polymer-ceramic composite scaffolds with high accuracy and resolution. Nonetheless, limited materials used as photoresist, residual toxic moieties, and need of post-processing remain challenges in the biomedical application of SLA scaffolds. In contrast to SLS, SLM uses a high energy density laser that completely melts the material thus increasing the mechanical strength and surface quality of the scaffold. The powders used require uniform distribution of spherical particles with equal size. The smaller the size, the higher the resolution and accuracy. When EBM is used, electron-beam gun in a high vacuum selectively scans and melts only conductive metal powder (even with high melting points) materials to form a 3D scaffold. The EBM-processed scaffolds have high surface roughness and limited accuracy [47]. FDM is an extrusion-based process that heats the material (polymer and polymer-ceramic composites) before squeezing it out of a nozzle. By moving the nozzle, the material is layer-by-layer deposited on a substrate. More comprehensive review regarding the methods of 3D scaffolds printing can be seen in Ref. [48]. Most printed scaffolds fulfil the requirements for tissue engineering applications providing interconnected micro- and macroporosity, anisotropy, and heterogeneity. Various types of materials could be used for printing of different scaffolds for skin, bone, nerve, muscle, cartilage regeneration or heart tissue replacement [49,50]. Оnly CAD-based design could produce scaffolds with regular and periodic structure with cube, diamond, gyroid, etc. unit cells. In that way, the porosity, pore size and surface-to-volume ratio can be exactly defined. However, biological materials should be liquidized before printing and biologically relevant cellular density is hard to be achieved [49]. Recently, the use of cryogenic 3D printing shows great potential in the incorporation of high quantity of bioactive moieties in situ into scaffolds. After fabrication at relatively low temperature (−32 °C), high bioactivity and adequate mechanical strength without post-treatment were achieved [51]. Nonetheless, the cost of specialized equipment is still high for mass fabrication.

4. Types of 3D scaffolds based on the source material

Depending on the source of materials utilized for fabrication, 3D scaffolds could be divided into alloplastic synthetic scaffolds and natural tissue scaffolds. Even though a wide range of materials evaluated as hydrogels are commonly thought of in two groups, natural and synthetic.

4.1. Alloplastic synthetic scaffolds

Synthetically created 3D scaffolds are vastly used materials for tissue engineering since they propose almost complete control over the mechanical properties and architecture of the construct. Commonly utilized materials are metals, bioceramics, glass and glass-ceramics, synthetic polymers, and a myriad of composites. Overall, these synthetic biomaterials can be broken up into two major subgroups, non-biodegradable and biodegradable. Recently, researchers emphasize the use of biodegradable materials as they create a suitable microenvironment for growth of native tissue and are susceptible to cellular remodelling leaving in vivo produced natural matrix [52]. Based on their application, the major groups of synthetic scaffold will be further discussed.

4.2. Hydrogel scaffolds

Hydrogels are composed of hydrophilic polymer chains either covalent or non-covalent (hold by intermolecular attractions) bonded. When crosslinked through either covalent or noncovalent bonds, natural (gelatin, fibrin, alginate, agarose, etc.) or synthetic (PEG, PAA, PEO, PVA, etc.) polymers form gels. In contrast to gels that are more solid-like than liquid-like, hydrogels absorb large amounts of water and swell without dissolving. In the swollen state, they are soft and elastic. The inherent crosslinking (by using bi-functional monomers) of hydrogels allows them to retain 3D shape and swell without dissolving. The higher the cross-linking extent, the lower the swelling. Both chemical and radiation crosslinkers have been used for the fabrication of hydrogels [53]. Chemical hydrogels contain covalent bonds, whereas physical hydrogels are maintained by ionic interaction, hydrogen bonding or molecular entanglement between polymeric chains. Deriving from natural macromolecules, hydrogel scaffolds exhibit high hydrophilicity, flexibility, biocompatibility, and degradability together with limited mechanical properties, the difficulty of purification and sometimes pathogen transmission and immunogenicity (depending on the source). They can be also used as injectable materials able to adapt the form of the damaged tissue. Synthetic polymers used for developing hydrogels such as PEG, PLGA, PVA, PCL, PLA, PU, etc., propose tunable and responsive physicochemical characteristics like modulus, water affinity, degradation rate, etc. at the expanse of potential cytotoxicity and lack of cell-adhesion moieties. According to their structure, both natural and synthetic hydrogels could be amorphous or semi-crystalline, while depending on their response to environmental stimuli, hydrogels could be divided into conventional and smart (intelligent). “Smart” hydrogels reversely change their swelling behaviour or structure in response to light, pressure, temperature, pH, ionic strength, electric or magnetic field, and other stimuli that make them interesting for the production of 4D scaffolds such as artificial muscles, self-regulating drug-delivery systems, etc. Hydrogels are also beneficial for cell transplantation because they offer immuno-isolation while allowing gaseous exchange as well as nutrients and metabolic substances to diffuse [54]. They are important materials for scaffolds due to the ability оf tailoring the mechanical properties, including peptide moieties preventing bacterial invasion, and adhering or suspending of cells [55]. The appropriate rheological properties (dependent on hydrogel chemistry and crosslinking) of hydrogels are crucial to ensure the construct shape maintenance without compromising cell (cytocompatibility) or bioactive moiety spreading and function. Hydrogels are currently used in cell scaffolds, bone regeneration, cartilage healing, wound dress and drug or growth factor delivery [56]. The main challenge for the compatibility of hydrogels remains the toxic moieties or chemicals used in the polymerization of synthetic or crosslinking of natural hydrogel precursors, and other organic solvents, initiators, stabilizers, etc. The methods used for fabrication of hydrogel scaffolds include solvent casting/leaching, gas foaming/leaching, photolithography, electrospinning, 3D printing, etc.

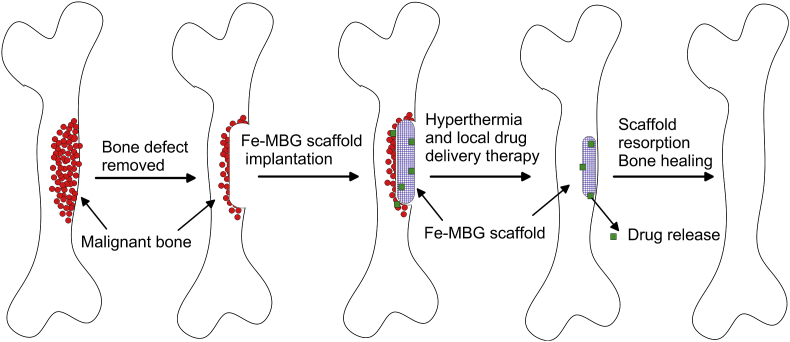

4.3. Natural tissue scaffolds

Natural tissues consist of cells, growth factors and extracellular matrix (ECM). ECM is a heterogeneous hydrophilic 3D matrix that provides a proper microenvironment for cell, accumulates and presents growth factors, directs migratory cells, and participates in mechanical signalling by mechanical receptors (integrins). The composition of ECM usually includes vitronectin, fibronectin, collagen type I and II, decorin, diglycan, laminin and perlecan [57]. The main components – collagen fibres and proteoglycan (from protein and hyaluronic acid) filaments, provide the durability and tensile strength of ECM. In order to exploit the advantages of natural ECM, researchers are using the decellularization procedure to remove all cellular components that could cause an inflammatory response in the host. Thus, the remaining ECM retains its composition, architecture, integrity, biomechanical properties, biological activity, hemocompatibility and is able to direct the cell migration, tissue-specific gene expression, and to control cell fate. The process of removal of cells and their sources are crucial for the decellularized ECM (dECM) performance. The decellularized material could keep the whole organ intact or could be further processed by cutting or digesting into the liquid to form a coat or ECM-containing hydrogel. By using detergents or mechanical manipulations, natural 3D scaffolds such as heart [58], lungs [59], urethra [60] and bladders [61] are decellularized and functionalized by re-implanting host-specific stem cells (re-cellularized) together with additional growth factors [62]. The sources for creating ECM scaffolds include native devitalized and decellularized human or animal (porcine, bovine) organs and tissues or de novo synthesized ECM from autologous, allogenic or xenogenic cells. Usually, human samples that could be used as dECM source are either aged or diseased while xenogenic animal materials are potentially immunogenic. Moreover, difficulties in preparation could also be faced. For in vitro synthesis (Fig. 2) of cell-derived dECM, a proper selection of specific adult (induced pluripotent) or embryonic stem cells should be made taking into account the medical application. It was found that MSC-produced decellularized ECM dramatically increased the growth and differentiation of neural cells [63] while maintaining the multi-potentiality of MSCs during expansion in vitro [54]. Nonetheless, some disadvantages such as immunogenicity of material left or inhomogeneity in cell distribution may appear, and risky and long immunosuppressant treatment can be needed [64]. To avoid immunological response, autologous or allogenic sources are used. Using autologous source cells, Hang et al. produced superior urea-extracted dECM containing non-collagenous proteins enhancing MSC proliferation, migration and differentiation [65]. This strongly suggests that the origin and preparation of ECM predetermine the biological activities of biomaterial scaffolds. Additionally, different cell types could be mixed to create gradient tissue scaffolds. The cells plated in 3D scaffolds secrete and integrate new components to form ECM trying to shape their environment. Nevertheless, these artificially fabricated dECM scaffolds are less dense and have restricted chemical complexity because their organization is a result of spontaneous, rather than cell-directed polymerization [66].

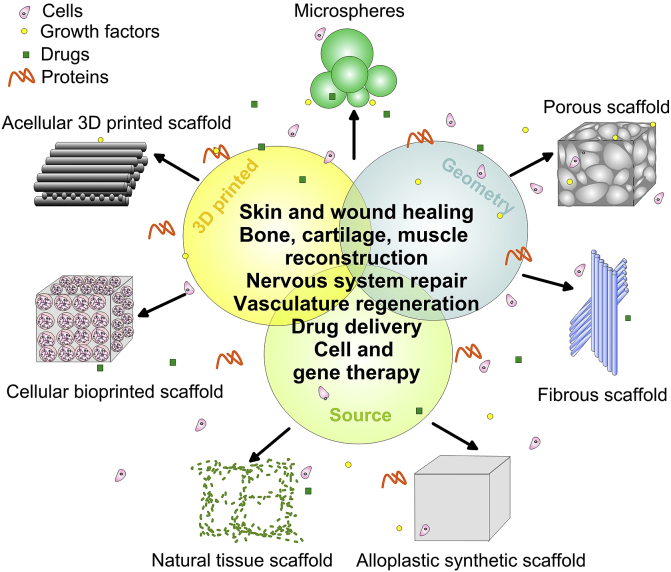

Fig. 2.

Schematic overview of in vitro preparation of ECM template.

Once implanted, the dECM releases soluble peptides while degrading that are able to chemo-attract stem cells to the injured sites [67]. These chemoattractive properties and degradation products vary depending on the age, species, gender or physical characteristics of ECM source. For example, a cell-derived ECM was obtained from cells grown in 3D cultures of fetal and adult synovium-derived stem cells (SDSCs) that were afterwards decellularized for ECM scaffold fabrication [68]. The fetal ECM provided a better microenvironment for proliferation, while adult ECM was advantageous for chondrogenic and adipogenic differentiation. However, all these costly and time-consuming procedures restrict the clinical application of the cell-derived matrix scaffolds.

It follows that an important factor that determines the biocompatibility of the scaffold except for the chemistry, morphology, structure, and properties, is the processing of a biomaterial. To overcome the disadvantages of a certain fabrication method, a combination of other methods could be used that complicates the existing production processes. Considering the variety of biomaterials used, not all of them are suitable for a given fabrication technology. This is a reason for constant modification of the materials which broaden their use. Since the surface characteristics such as wettability, chemistry, charge, and surface roughness are also able to regulate the contacts with the living cells and ECM proteins, a variety of surface treatments are proposed to optimize the biocompatibility of the scaffold while sealing undesirable additives and regulating absorption or corrosion rate. The next paragraphs discuss the properties, advantages and disadvantages of the major types of biomaterials used in the fabrication of 3D scaffolds dedicated for various applications.

5. Scaffolds for hard tissue application

Bone tissue consists of organic (predominantly collagen matrix, 22 wt%), inorganic (mainly HAp crystals, 69 wt%) components and water (9 wt%) [69]. In its hierarchical organization two main types of bone structures could be distinguished: trabecular (porous) and cortical (compact) bone, both reinforced with collagen fibres. Because of the natural self-repairing and regeneration ability of bones, most of the produced scaffolds aim at providing regenerative signals to osteogenic cells to enhance regeneration and repair [69]. A major difficulty in designing scaffolds for load-bearing application is to simultaneously tailor all biomaterial requirements that are competing in nature. Hard tissue scaffolds should not only be biocompatible, well-integrated with the native tissue, and easily produced but should also have an ideal replacement rate and highly porous structure which doesn't significantly compromise the adequate mechanical properties. Commonly used alloplastic synthetic scaffolds as bone grafting materials that mimic the native bone tissue and provide structural and mechanical support are metals, biomimetic ceramics and composites.

5.1. Non-biodegradable and resorbable metal scaffolds

As first-generation materials for bone substitutes, metallic 3D scaffolds are largely popular for load-bearing applications compared with ceramics or polymers because of their high mechanical strength, fatigue resistance, and printing processability. Commonly used metallic biomaterials include titanium, stainless steels, cobalt-chromium (Co–Cr) based alloys, and magnesium (Mg). Titanium (Ti) is a metallic biomaterial characterized with good biocompatibility, tensile strength, and corrosion resistance. Porous Ti scaffolds with 3D architecture benefit the vascularization, nutrient and gas transport, and cell seeding [70]. As previously explained, the pore sizes have a decisive influence on bioactivity of the porous scaffolds. In order to determine the optimum pore size, Yang et al. fabricated screw-shaped Ti6Al4V dental implant prototypes by laser beam melting (LBM) with three controlled pore sizes (200, 350 and 500 μm) [71]. MC3T3-E1 cells showed improved attachment, proliferation and differentiation on both 350 and 500 μm pore size implants. Moreover, the 350 μm pore size alloy displayed the best mechanical stress distribution in the surrounding bone under 20, 30, 40 and 80 N loading. When EBM processing was used, Ti6Al4V scaffolds revealed better anti-corrosion ability with reduced precipitates of harmful Al and V ions compared to wrought scaffolds [72]. Moreover, the same EBM technology was capable of producing double and triple-layered meshes from Ti6Al4V alloy [73]. The cylindrically shaped lattice scaffolds were composed of layers with different porosity of 65–21% in order to mimic trabecular bone structure. The graded (denser outer and less dense inner) tubular design of the scaffold demonstrated decreased Young moduli (from 0.9 to 3.6 GPa) compared with a dense alloy that brought it closer to that of human bones. By changing the morphology of the lattice structure, the deformation behaviour of the scaffold was able to provide a unique combination of high ductility, energy absorption, and strength simultaneously [73]. Nonetheless, comparing the performance of EBM-produced Ti6Al4V and Co–Cr scaffolds with similar porosity of 67–70% and pore size of 470–545 μm on bone tissue growth, Shah et al. [74] established higher osteocyte density at the periphery of Co–Cr scaffold. The authors explained that fact with the existence of more favourable biomechanical environment and higher stiffness within Co–Cr alloy as opposed to Ti6Al4V. Fousová and her group produced fully interconnected open porous scaffold with rough surface by adhering spherical particles (15–50 μm) from 316L stainless steel using SLM [75]. The mechanical properties in compression of the scaffold with square-shaped pores with size of 750 μm and porosity of 87 vol% approached those of human trabecular bone. In another study, pre-cultured cell-loaded with rat bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) Ti fibre mesh with volumetric porosity of 86% and fibre diameter of 45 μm demonstrated an almost complete absence of inflammatory cells and improved bone healing capacity [76]. Although the bone defect symptoms were improved, the use of embedded BMSCs requires appropriate donor sites that could cause additional pain and infection. The main problems with titanium, Co–Cr and stainless steel scaffolds remain the lack of metabolization over time, need of repeated surgery, risks of ion release and abrasion (that could trigger inflammatory cascade), disease infection, low tissue adherence and prolonged recovery time.

Porous Mg scaffolds are promising biomaterials for bone substitute application owing to their good mechanical properties and biodegradability [77]. Moreover, released Mg ions and biodegradation products in endosseous sites demonstrated the ability to induce new bone formation and neovascularization [78]. In this context, open porous Mg scaffolds with 250 and 400 μm pore size and 55% porosity were found to exhibit good cytocompatibility and enhanced alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity indicating osteogenic differentiation in vitro whereas in vivo the scaffold with larger pore size promoted vascularization and higher bone mass formation in a rabbit model [79]. The compressive strengths were about 41 and 46 MPa whereas Young's moduli reached values of 2.2 and 2.4 GPa for 250 and 400 μm pore size scaffold, respectively which values exceeded Young's moduli of the cancellous bone. However, weak points of porous Mg scaffolds remain the fast degradation rate and accelerated micro galvanic corrosion by the presence of impurities [80,81] together with the production of a large amount of hydrogen gas during in vivo degradation [82]. In addition, it was found that Mg ions can negatively affect the function of red blood cells and hemolysis ratio in direct contact with blood [83].

5.2. Low degradable bioceramic, glass and glass-ceramic scaffolds

Ceramic biomaterials usually include inorganic calcium or phosphate salts that have osteoconductive (promote new bone ingrowth) and osteoinductive (promote osteoblastic differentiation) properties. Ceramics could be classified into inert (non-absorbable), semi-inert (bioactive) and non-inert (resorbable) [84]. They are commonly brittle in nature but show good compression and corrosion resistance. Hydroxyapatite (HAp, Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2), β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP, Ca3(PO4)2) and bioactive glasses are among the most common biomaterials used for 3D scaffolds in bone regeneration. Except conventional methods for production of porous ceramic scaffolds such as polymer sponge method, salt leaching, dual-phase leaching, gel casting, etc., the major techniques available for ceramics 3D printing are: 1) agglomeration with polymer, chemical/physical solidification and thermal processing, and 2) sacrificial inverse matrix printing, infiltration with ceramic slurry and burning the negative [85].

Because of their similarity to bone, bio-resorbability and good biocompatibility, calcium phosphate biomaterials are widely used for orthopaedic and dental implant applications. 3D printed β-TCP scaffolds showed an increase in uniaxial strength with the increase of sintering temperature and time [86]. The compression strength could be additionally improved by controlling particle size distribution and binder's concentration. Another approach proposed by Deng at al. includes incorporation of Mn in β-TCP scaffolds that improved both biomechanical (density and compressive strength) and biological properties [87]. The ionic products from the scaffold promoted the proliferation of rabbit chondrocytes and rBMSCs in vitro and improved regeneration of subchondral bone and cartilage tissue as compared to β-TCP scaffolds upon transplantation in rabbit models. However, similarly to HAp, the application of β-TCP as bone regeneration scaffold is limited because of its overall poor mechanical properties. For that reason, 3D printed porous β-TCP scaffolds with interconnected squire channels (500 μm in size) were mechanically strengthened by SiO2 (silica; 0.5 wt%) and ZnO (0.25 wt%) dopants. The cylindrical scaffolds demonstrated increased density and a mean increase in compressive strength of 250% after sintering at 1250 °C when compared to pure β-TCP scaffolds [88]. A greater rate of attachment and proliferation of human fetal osteoblast cells (hFOBCs) within the doped scaffolds was also observed.

In general, bioactive glasses (BG, CaO–SiO2–P2O5 composition) share better degradation properties and bioactivity than HAp and β-TCP. Therefore, the biodegradation performance of ceramic bone implants could be improved by introducing mesoporous silica-based particles that also promote Si ion release known to be essential for pro-angiogenesis and healthy bone development [89]. Bioceramic scaffolds with 34% porosity were 3D printed with laser-aided gelling from CaCO3/SiO2 (5:95 wt%) sol in the form of cylindrical specimens and sintered at 1300 °C afterwards [90]. The bioceramic scaffold showed 47 MPa compressive strength value or 30% improvement over pure SiO2 scaffold, no cytotoxicity, and good biocompatibility when tested in MG-63 osteoblast-like cells in vitro. Pressure extruded ceramic composite scaffolds of calcium sulphate hydrate (CSH) and mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG) with different mass ratio of the components, uniform square macroporous structure (67–68% porosity) and pore size of 350 μm indicated stimulated adhesion, proliferation and osteogenic-related gene expression of hBMSCs (human bone marrow-derived stem cells) in vitro [91]. In vivo results in rats demonstrated that the scaffolds promoted new bone formation in calvarial defects compared to pure calcium sulphate hydrate (CSH) scaffolds.

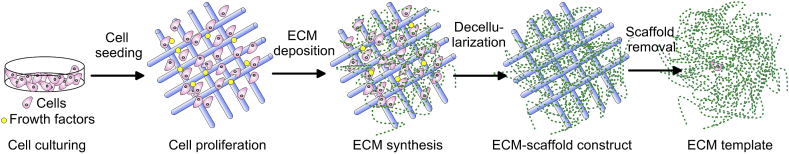

Application of growth factors or cytokines is used to promote cell differentiation, tissue formation or neoangiogenesis. On one hand, most of the growth factors (GFs) have a short half-life in circulation and on the other, fast and uncontrolled release of GFs may increase the adverse effects on non-target sites. For that reason, the controlled release of these substances is a desirable capability of the scaffold. To facilitate vascularization, Li et al. printed at room temperature (without sintering afterward) mesoporous with approximately 300 μm macropores silica/calcium phosphate cement (CPC)-based 3D scaffold with concomitant Si ion (promoting vascular tissue ingrowth) and recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) release stimulating osteogenesis of human bone marrow stromal cells [92]. The produced scaffolds with uniform interconnected pore structure induced osteogenic differentiation of hBMSCs and vascularization of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (hUVECs) in vitro. Implanted in femur defect rabbit model abundant new vessels around the complex scaffold and rapid rate of osteogenesis were observed as compared to CPC control scaffolds [92]. Moreover, various studies demonstrated improvement in biological and physicochemical properties of mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG) scaffolds by incorporation inorganic therapeutic components such as Sr [93], Zn, Mg [94,95], Zr [96], Ga [97], or B [98]. Incorporation of beneficial Fe (5–10%) in MBG turned the scaffolds with high porosity (83%) into biocompatible magnetic material that exposed to the external magnetic field had great potential for use in hyperthermia therapy (at around 43 °C) of malignant bone tumours [99]. The scaffolds with a hierarchical structure of large 300–500 μm pores and 4.5 nm mesopores demonstrated a slight decrease in compressive strength (46–48 kPa) as opposed to pure PBG scaffolds (50 kPa). The multifunctionality of Fe-MBG scaffolds that makes them suitable for therapy of malignant bone diseases is schematically presented in Fig. 3. Five percentage of Fe in MBG scaffold benefited the mitochondrial activity and gene expression of BMSCs indicating improved osteoconductivity of the implant. This fact the authors explained with changes in ionic composition and pH value that improved cell viability and differentiation [99]. Moreover, mesoporous silica displayed additional capability of local drug release owing to its large nanopore volume, size and surface area. To demonstrate that Zhang et al. fabricated 3D printed porous Sr-containing MBG porous (400 μm pore size, 70% porosity) scaffold that showed sustained dexamethasone (anti-inflammatory drug) release with a rate depending on Sr dissolution characteristics of the scaffold [100]. To combine drug-delivery properties with additional angiogenetic and antibacterial properties, multifunctional Cu-containing MBG scaffold with large pore size of 300–500 μm loaded with ibuprofen was prepared by simple polymer sponge method [101]. The ion (Cu2+) release was able to induce a hypoxic cascade of hBMSCs activating neovascularization, promote osteogenic differentiation, and prevent osteomyelitis incidence by infections. In this respect, composite ceramic scaffolds could meet all the requirements of a bioresorbable therapeutic cell and drug (or antibiotics and growth-factors) carriers for improved healing in bone tissue engineering. The major disadvantages of ceramic scaffolds are their brittleness, compressive strength lower than that of the human bone (100–230 MPa [102]) at high volume percentage of porosity, and the need of high sintering temperature that limits the incorporation of bioactive molecules in the scaffolds. Some ceramics such as calcium sulphate hydrates (CSH) display faster degradation rate than the formation of new bone and a release of acidic degradation products that are not beneficial for cell proliferation and viability [103]. Other ceramics like wollastonite (CaSiO3) are difficult to be cut and shaped in uniform porous scaffold with controllable mechanical properties and porosity [104]. Moreover, the highly promising MBG scaffolds could have high degradation rate together with unstable interface/surface performance that could also decrease cell attachment and proliferation.

Fig. 3.

A scheme illustrating the potential application of Fe-MBG scaffolds for malignant bone treatment (hyperthermia) and regeneration of the defect bone. Adapted from Ref. [99].

5.3. Polymer scaffolds

Polymer materials are vastly used to renovate the traumatized tissue due to their unique properties such as biocompatibility, reproducible mechanical, physical properties, workability, and low price. Because non-biodegradable synthetic polymer scaffolds require a procedure of surgical removal, they are not widely used. Some acrylic polymers like PHEMA, PHPMA, PMMA [105,106], and conductive polymers [107] are such representatives. Two-part self-polymerizing PMMA cement is known to be the most enduring material in orthopaedic surgery used in total joint replacement for fixation of components [108]. However, drawbacks such as aseptic loosening caused by monomer-mediated bone damage, inherit inert properties, and mechanical mismatch during long term wearing are also reported [108].

Biodegradable polymers with tunable degradation rates could be both natural (from human or animal tissues) and synthetic. Their degradation rate depends on molecular weight, the structural arrangement of macromolecules (amorphous/crystal structure), isomeric characteristics, formulation, architecture, and quantity of the material [[109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151]]. Natural polymer scaffolds usually demonstrate a lack of immune response and better cell interactions while synthetic polymers are cheaper, stronger, and have better functionality although sometimes triggering immune response and toxicity [37]. Biodegradable polymers demonstrate suboptimal load-bearing capacity when used alone that limit their application as hard tissue scaffolds. However, in pulpodentinal complex and periodontal apparatus, the smaller sizes and difficulties in reaching the target places require soft, injectable scaffolds that match irregular patient defects [110]. Moreover, the ability of polymers to incorporate diverse bioactive moieties could be most eminent to induce osteogenic differentiation in less loaded constructs. For example, immobilizing or including GFs within the scaffold are promising approaches as many GFs exhibit inherited binding properties to molecules of ECM through specific binding protein intermediaries [111]. Bilayer system of porous PLGA cylinder overlaid with PLGA microspheres dispersed in alginate sponge matrix was examined for localized delivery of pre-encapsulated transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF β1 – 50 ng) and bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2 – 2.5 and 5 μg) applied for osteochondral defect repair [112]. In vitro, the total dose of GFs was delivered at the end of the sixth week. After co-encapsulation of TGF-β1 with a higher dose of BMP-2, the histological analysis demonstrated tissue repair after very short (2 weeks) period, higher quality cartilage with improved surface regularity, and very good tissue integration in the rabbit model. The controlled release rate of GFs from the scaffolds preserved cartilage integrity from 12 to 24 weeks [112]. Using non-biodegradable orientated in parallel arrays of polystyrene sub-micron fibres with diameter (630–760 nm) approximating the diameter of ECM fibres, coated with fibrin and bioprinted with tendon- or bone-promoting-GFs (fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) or BMP-2, respectively), Ker et al. [113] inhibited the myocyte differentiation of mouse C2C12 myoblasts and stimulated cell alignment, tenocyte and osteoblast differentiation. The bioprinting technique gives the possibility to have direct control over the concentration of the immobilized growth factors. Therefore, using hydrogel with embedded GFs, it is possible to present a precise quantity of extrinsic factors and direct cells rather than adding them in the culture medium.

5.4. Particle loaded polymeric and other composite scaffolds

The development of composite scaffolds allows for the engineering of biomaterials with suitable mechanical and physiological properties by controlling the type, size, fraction, morphology and arrangement of the reinforcing phase. Moreover, the degradation behaviour of the scaffolds could be altered by adding bioactive phase in the matrix [114]. For instance, PCL is relatively elastic and drug permeable but has poor mechanical stability (low modulus with high elongation behaviour), slow degradation (2–4 years) in living tissue, and poor cellular adhesion properties. However, it shows blend compatibility with other biomaterials such as Sr-hydroxyapatite [115], nanohydroxyapatite, nanocellulose, carbon nanotubes [116,117], cyclodextrins [118], etc. It follows that PCL possesses the capacity for functionalization while overcoming the poor mechanical stability and low bioactivity of the unmodified polymer. PGA/HAp composites demonstrated high bioactivity, osteoconductivity uniform cell seeding, cell ingrowth and tissue formation as hard tissue scaffolds [119]. By releasing Ca and Si ions, MBG powders were also found to neutralize the acidic degradation of synthetic polymers such as PLGA in composite scaffolds and stimulate thereby cell response [120]. The ceramic mesoporous powders increased hydrophilicity, water absorption and degradation rate of the composite compared to pristine PLGA scaffolds. Electrospun hybrid scaffolds of randomly orientated fibres (average diameter 4.11 μm) of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) and silicate containing hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (PHBV-SiHAp) seeded with hMSCs showed the largest adhesion and differentiation ability compared with pure piezoelectric PHBV and non-piezoelectric PCL scaffolds [121]. The composite scaffold revealed improved mineralization and superior osteoinductive properties either because of changed scaffold chemistry by the presence of bioactive SiHAp nanoparticles or by altering scaffold charge due to inherited piezoelectricity of PHBV.

In another study, calcium phosphate cement (CPC)-based scaffold incorporating chitosan, absorbable fibres, and hydrogel microbeads possessed 4-fold increased flexural strength and 20-fold enhanced toughness compared to rigid CPC microbead scaffolds which matched the strength of cancellous bone [122]. These non-rigid scaffolds demonstrated excellent proliferation, osteodifferentiation and enhanced mineralization when incubated with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSC) in vitro. Similarly, freeze-dried porous fluorhydroxyaptite (FHAp)-Mg-gelatin scaffold with different amount of FHAp (30, 40, 50 wt%) and pore size of 150–250 μm improved the compressive strength of the polymer from about 2.1 MPa to 3.3 MPa at the highest amount of FHAp and supported the proliferation and adhesion of MG-63 cells for bone regeneration [123]. Graphene alone was found to stimulate osteogenesis [124] while covalent associations of graphene oxide (GO) flakes (4 nm thick) in porous collagen scaffolds directed the stem cells fate toward osteogenic differentiation by up-regulating cell-adhesion molecules and stiffening the scaffold [125]. As opposed to pure collagen scaffolds (14.6 kPa), GO-collagen construct showed elastic moduli of about 39 kPa. It was also demonstrated that adding silk (2.5 and 5 wt%) to mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG) scaffold (94% porosity) improved its mechanical properties, cell attachment, proliferation and controlled drug release [126]. The compressive strength rose up from 60 kPa up to 250 kPa when incorporating 5 wt% silk in MBG scaffold which means 300% increase. The degradation rate of the composite was slower as opposed to that of a MBG scaffold and a thin silk film on the pore walls (200–400 μm pore size) was formed. Thus formed stable surfaces with fibroin provided better support for BMSCs proliferation and differentiation [126].

In a remarkable study, Cheng et al. tried to construct highly porous bilayer scaffold with interconnected honeycomb structure with chondral (consisting of plasmid TGF-β1-activated chitosan-gelatin scaffold) phase integrated into osseous (of plasmid BMP-2-activated HAp/chitosan-gelatin scaffold) phase [127]. This bilayer gene-activated scaffold with pores of about 50–100 μm was dedicated to spatial control of localized gene delivery that could induce the mesenchymal stem cells in different layers to differentiate into chondrocytes and osteoblasts in vitro and in vivo. The spatially controlled and sustained delivery of plasmid DNA encoding for tissue inductive factors maintained the specific cell phenotypes of complex osteochondral integrated tissue derived from a single stem/progenitor cell source in vitro. In vivo, the complex scaffold gave simultaneous support of articular cartilage and subchondral bone [127].

The surface properties of 3D scaffold biomaterials could be altered in order to promote their bioactivity, corrosion resistance, hydrophilicity, mechanical strength or tribological properties. For example, bioactive adhesive molecules such as collagen, fibronectin, growth factors, insulin, etc. can be covalently or physically attached on the biomaterial surface. These modified 3D scaffolds are able to modulate in a complex fashion the cellular response. Such hybrid polymeric-bioceramic porous (over 60% porosity) scaffolds of β-TCP/HAp vacuum coated with alginate demonstrated improved osteoblast adhesion, maturation and proliferation as well as an enhanced mechanical performance involving increased fracture toughness, Young's modulus, and compressive stress close to that of cancellous bone [128]. The improved osteoblast adhesion and migration the authors attributed to the additional biocompatibility created by alginate via changing surface micro-topography and roughness. Another approach aiming at increasing the bioactivity and biocompatibility of metal implants is deposition of wollastonite (CaSiO3) [129], calcium phosphate [130], biomimetic nanoapatite [131], or polycrystalline diamond [132] coatings on different titanium scaffolds. When EBM-manufactured Ti6Al4V scaffold was functionalized with Ag and CaP nanoparticles via electrophoretic deposition, the change in hydrophobicity and surface roughness at nanoscale provided physical cues that disrupted bacterial adhesion [133]. The silver nanoparticles at concentration 0.02 mg/cm2 in CaP film covered with positively charged PEI indicated bacteriostatic activity against gram positive bacteria, S. aureus, during 17 h of exposition. Although bi- and multiphasic scaffolds provide enhanced mechanical and biological performance, there is always a concern about the adhesive strength between the adjacent layers or contacting non-homogeneous biomaterials that could lead to delamination or crack propagation. Although improving the surface performance, these additional modifications are usually cost- and time-consuming.

A summary of recent studies on composite scaffolds using numerous production technologies and stem cells dedicated to a hard tissue application is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Composite scaffolds for bone tissue application.

| Biomaterial composition | Fabrication | Cell type | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gelatine, alginate, HAp scaffolds | Extrusion | hMSCs | Cell survived the printing process and showed 85% viability after 3 days | [134] |

| Chitin-nanoHAp scaffolds | Freezing/thawing method | COS-7 (fibroblast-like) cell line | Good adhesion and proliferation of cells | [135] |

| Gelatin-carboxymethyl chitosan-nanoHAp scaffolds | High stirring-induced foaming and freeze-drying | Human Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cell microtissues | Cell growth, proliferation and differentiation; high mineralization capacity | [136] |

| Glycol chitosan-hyaluronic acid-nanoHAp scaffolds | Injectable | MC-3T3-E1 | Cytocompatibility with cells well attached to the pores | [137] |

| Chitosan, gelatin, and GO containing scaffolds | Freeze-drying | Rat calvarial osteoprogenitor cells and mouse mesenchymal stem cells (C3H10T1/2) | Promote differentiation into osteoblasts; increased collagen deposition in vivo | [138] |

| Chitosan-nanoHAp containing Cu/Zn alloy nanoparticle scaffolds | Freeze-drying | Rat osteoprogenitor cells | Increase protein adsorption and antibacterial activity; no toxicity towards osteoprogenitor cells | [139] |

| Blended PLGA-silk fibroin fibrous scaffold coated with HAp | Electrospinning | MSCs | Increased adhesion, proliferation and differentiation towards osteoblasts; excellent cytocompatibility and good osteogenic activity | [140] |

| Micro-nano PLGA-collagen – nanoHAp rods scaffolds | Electrospinning | MC3T3-E1 | Improved osteogenic properties; bioactivity | [141] |

| Alginate-PVA-HAp hydrogel scaffold | Bioprinting | MC3T3 | Excellent osteoconductivity; well distributed and encapsulated cells | [142] |

| Tri-layer scaffold consisting of superficial PVA/PVAc-simvastatin (a type of statin)-loaded layer, followed by PLC-cellulose acetate-β-TCP layer and final PCL layer | Electrospinning | MC3T3-E1 | Higher mineralization; enhanced cell attachment and proliferation | [143] |

| Laminated nanoHAp layer on PHB (polyhydroxybutyrate) fibrous scaffold | Electrospinning | MSCs | Better adherence, proliferation and osteogenic phenotype formation | [144] |

| PMMA-nHAp decorated cubic scaffold | Solvent casting and particle leaching | MG-63 | Friendly environment for cell growth and protection from microbial infection | [145] |

| PLGA/TiO2 nanotube sintered microsphere scaffolds | Emulsion and solvent evaporation method and sintering | G-292 cell lines | Increased cell viability; a higher amount of bone formation | [146] |

| PU fibrous scaffolds loaded with MWCNTs (0.4 wt%) and ZnO nanoparticles (0.2 wt%) | Electrospinning | MC3T3-E1 | Scaffolds promote osteogenic differentiation | [147] |

| PCL-nanoHAp nanofibre layer deposited on Mg alloy scaffold | Electrospinning | Osteocytes | Retard corrosion and increased osteocompatibility; higher cell attachment and proliferation | [148] |

| Porous rGO-nanoHAp scaffold | Self-assembly | rBMSCs (rat bone mesenchymal stem cells) | Enhanced proliferation and osteogenic gene expression | [149] |

| PLLA - osteogenic dECM (from MC3T3-E1) scaffolds | Electrospinning | mBMSCs (mouse bone marrow stem cells) | Faster proliferation; early stage osteogenic differentiation | [150] |

6. Scaffolds for soft tissue application

By careful selection of biomaterials and key scaffold characteristics, researchers developed novel techniques for developing complex architectures with desired properties for soft-tissue engineering applications. These scaffolds should be fabricated so that to regenerate and mimic both the anatomical structure and function of the original soft tissue to be repaired. Polymers are commonly used biomaterials to construct soft matrices that are widely utilized for the production of most of the transplanted organs such as kidneys and liver [2], but also successfully applied for muscles, tendon [151,152], heart valves, arteries [153], bladder and pancreas [154,155] regeneration.

6.1. Synthetic polymer scaffolds

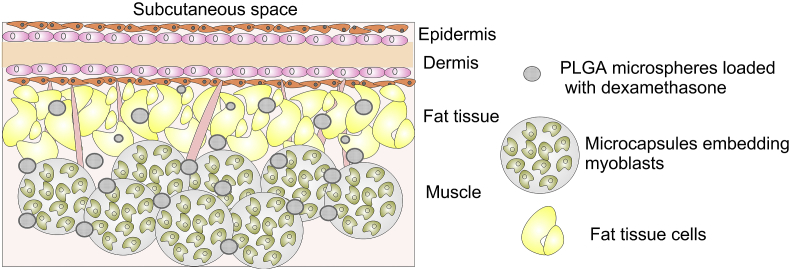

Synthetic polymers are easily produced under controlled conditions. Their physical and mechanical properties are tunable, predictable and reproducible and thus, could be tailored for the production of scaffolds dedicated for a specific application. The most commonly utilized synthetic polymer for drug, gene, and growth factor delivery application [[156], [157], [158]], is PLGA, a flexible and permeable copolymer of lactic and glycolic acid. Each lactic acid residue includes a pendant methyl group which makes the surface hydrophobic. The polymer chains show a lack of functional groups and biodegrade in non-toxic but highly acidic glycolic and lactic acid [159]. To address the problem with acidity, a greater amount of glycolic than lactic acid could be used to form PLGA that lessens the degradation rate and lowers the acidic byproducts. Because of their semi-permeability, PLGA microspheres were used to entrap living cells like myoblasts [160]. When subcutaneously implanted, the former simultaneously released therapeutic anti-inflammatory drug to protect these cell from the host immune system (Fig. 4). The myoblast cells retained their viability in 30 day period suggesting that the semi-permeable microspheres allowed appropriate diffusion of nutrients and oxygen. These encapsulated cell implants loaded with dexamethasone, after 60 days of subcutaneous post-implantation in rats diminished the inflammatory response by sustain delivery of the drug. The histological analysis revealed that blood capillaries surrounded the microcapsule aggregates in 100 μl dexamethasone-treated mice group [160].

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of subcutaneous microenvironment after implantation of encapsulated myoblast cells and microspheres releasing dexamethasone in mice. Adapted from Ref. [160].

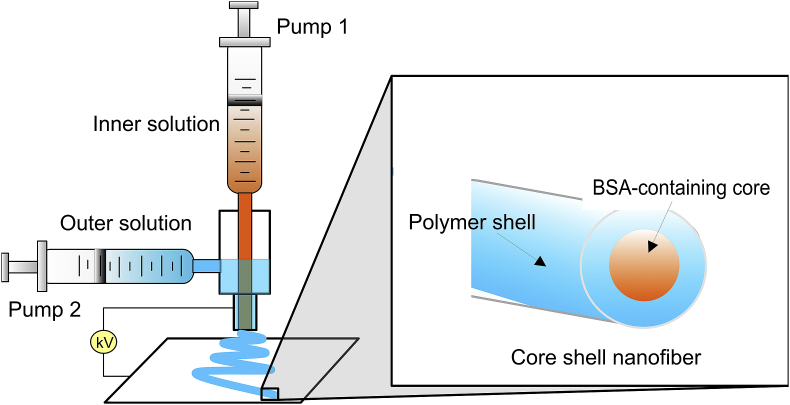

Not only encapsulated but also aligned nanofibre scaffolds were found to be suitable for highly organized soft tissues such as skeletal muscle, ligament and peripheral nerve regeneration whereas random nanofibres were useful for cartilage and skin regeneration application [161]. Since muscle fibres must grow parallel to one another following identical anisotropy, electrospun PLGA scaffolds of aligned fibres with a diameter of about 0.6–0.9 μm were found to provide topographical cues guiding the alignment of myoblast cells (C2C12 murine myoblasts) and encouraging their differentiation as compared with randomly oriented fibre substrates [162]. Moreover, the incorporation of polyaniline in PCL well-ordered fibrous scaffolds increased the electrical conductivity of constructs thus giving not only topographical but also electrical cues to C2C12 myoblast cells both synergistically improving myotube maturity [163]. Another approach applied is using permeable core-shell nanofibres that incorporate bioactive agents and enable controlled release within the tissue. The active substance is usually entrapped in the core layer. Li et al. used co-axial electrospinning where two syringe pumps fed both solutions separately (Fig. 5) to produce poly(l-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone), (PLC) fibrous scaffold of different LA:CL ratio and BSA (model protein) containing core, namely PLC(50:50)BSA and PLC(75:25)BSA [164]. The BSA release of PLC(50:50)BSA and proliferation rate of hMSCs toward smooth muscle cells were higher than those of PLA(75:25)BSA. Except for tunable mechanical properties, these core-shell nanofibres possessed regulable release potential as medical 3D scaffolds.

Fig. 5.

A scheme illustrating the principle of co-axial electrospinning where the polymer in a solvent coats the inner aqueous solution while immerging from the needle. As a result, a smooth and beadless core-shell nanofibre is formed. Adapted from Ref. [164].

Damaged neural tissues are known to regenerate for a longer period of time whereas sometimes larger nerves never recover. Similarly to muscle scaffolds, for enhanced nerve regeneration fibrous scaffolds of PLLA, PCL, PGA, etc. with aligned or random arrangements are commonly used [165]. Moreover, different studies demonstrated that therapeutic cell-laden scaffolds also enhanced in vivo soft tissue regeneration. For example, by combining longitudinal aligned electrospun scaffolds of PCL and PLGA (proportion of 4.5:5.5) with hDFCs (human dental follicle cells), neural regeneration was stimulated [166]. The authors found no cytotoxic reactions and when transplanted to restore the defect in rat spinal cord, re-myelination and induced tissue polarity occurred. It was also reported that incorporating of nerve growth factor (NGF) into aligned core-shell PLGA nanofibres enhanced physical and biomolecular signalling and promoted better nerve regeneration in 13-mm rat sciatic nerve defect than only PLGA scaffold [167]. Similarly, a strong electrospun fibre-aligned scaffold of PCL and PLLA with incorporated bFGF and PGF (platelet-derived growth factor) was found to up-regulate the gene expression of hMSCs in vitro [168] critical for the viability and repair of the anterior cruciate ligament that had a poor healing capability.

The complexity of mechanical requirements and physical properties of cartilage hinders the fabrication of effective artificial scaffolds for cartilage regeneration. Because of low coefficient of friction (0.02–0.05 against smooth and wet substances), high permeability to fluids, and biocompatibility, PVA-based hydrogels were developed to be used as synthetic scaffolds for articulating cartilage [169]. Kim and his group developed macroporous PVA sponge incorporating in its pores encapsulated rabbit chondrocytes in photocrosslinkable PEG derivates that improved in vitro chondrocyte functions and collagen accumulation within the scaffold [170]. In an ectopic mouse model, the mechanical properties of the cell-laden PVA-based scaffold were biomimeticaly reinforced by over 80% compared to their acellular counterparts. Similarly, by encapsulating chondrocytes in a photopolymerized degradable PEG tiol-ene hydrogel scaffold with localized presentation of TGF-β1, Sridhar et al. demonstrated in vitro cell viability, proliferation, and cartilage-specific molecules generation at a higher rate than without GF [171]. It follows that tethering GFs into synthetic polymer scaffolds integrates promoting effect on cells and provides advantages for clinical applications. An issue when using extrusion printing technology for scaffold production is the elevated temperature (above 100 °C) that prevents the incorporation of bioactive materials promoting the healing process. Guo et al. proposed lowering the printing temperature of PLGA scaffold by utilizing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a solvent that allows for the incorporation of proteins favourable for induction of hMSC differentiation [172]. After the solvent treatment, the material became tougher with improved flexibility and compressive strength similar to that of native cartilage while the activity of the growth factors was retained with the cold printing method used.

In another study, thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) (25%)/PCL (75%) blends with thermally induced shape memory were produced by melt blending and showed 98% shape fixing ratio and 90% shape recovery ratio upon heating (60 °C in hot water bath). 3T3 fibroblasts cells cultured on the TPU/PCL scaffold indicated high viability together with obvious cell-substrate interactions [173] that make the composite biomaterial suitable for surgical sutures or other medical devices. However, many synthetic polymers demonstrate low cell-affinity surfaces [174], hard to control degradation rate, and in vitro cytotoxicity [159]. Other problems encountered are lack of hydrophilicity, bioactivity, and release of acidic by-products that lower pH values and trigger inflammatory response [175].