Abstract

Although approximately one in five Medicare beneficiaries are discharged from hospital acute care to postacute care at skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), little is known about access to timely medical care for these patients after they are admitted to a SNF. Our analysis of 2,392,753 such discharges from hospitals under fee-for-service Medicare in the period January 2012–October 2014 indicated that first visits by a physician or advanced practitioner (a nurse practitioner or physician assistant) for initial medical assessment occurred within four days of SNF admission in 71.5 percent of the stays. However, there was considerable variation in days to first visit at the regional, facility, and patient levels. We estimated that in 10.4 percent of stays there was no physician or advanced practitioner visit. Understanding the underlying reasons for, and consequences of, variability in timing and receipt of initial medical assessment after admission to a SNF for postacute care may prove important for improving patient outcomes and particularly relevant to current efforts to promote value-based purchasing in postacute care.

As US health care moves toward value-based payment, hospitals are being held accountable for patient outcomes after discharge. Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, for example, made reducing hospital readmissions a national priority by applying financial penalties to hospitals with excess readmission rates. Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), which provide postacute care for one in five Medicare beneficiaries,1,2 represent an important discharge destination for patients who require rehabilitation or skilled nursing after an acute hospital stay. These patients are medically complex and at high risk of poor outcomes, with nearly a quarter rehospitalized or dead within thirty days of hospital discharge.3 Efforts to reduce hospital readmissions from SNFs include dedicating “extensivist” physicians who follow complex patients across settings and increasing access to providers via telehealth (for example, using a connected care model).4–7 These efforts recognize that delays in medical care during the transition from hospital to SNF result in poor outcomes.8–12

However, one previously overlooked aspect of the relationship between delayed medical care and poor outcomes during that transition is whether patients discharged to a SNF receive a timely initial medical assessment by SNF physicians or advanced practitioners (nurse practitioners and physician assistants). The ideal timing of a medical assessment after admission to a SNF is not well defined empirically or conceptually. In theory, the timeliness of the initial visit would be determined based on the clinical needs of the patient. In practice, however, the timing of clinician visits is influenced by additional factors—including the needs of other patients under the clinician’s care, financial incentives or billing requirements, and regulatory mandates. While hospitalized patients are typically seen daily by an attending physician who oversees their care, physicians are rarely present daily at the receiving SNF.13,14 And while federal regulations specify that physicians must oversee medical care and participate in the design of care plans for SNF patients,15 Medicare mandates only that the initial assessment by a SNF physician be completed within thirty days of SNF admission.16 Advanced practitioners may conduct necessary focused visits with new SNF patients prior to the initial assessment by a physician.16

Whether current practice by SNF physicians and advanced practitioners reflects this standard is unknown. SNF practice is relatively uncommon among physicians nationally. In a 1997 national survey of 20,000 US physicians, only 15 percent reported treating any SNF patients, and the majority spent less than two hours per week on SNF practice.17 A more recent national study using Medicare claims found that the number of physicians or advanced practitioners who made any visits to SNFs did not change from 2012 to 2015.18 On the one hand, these studies raise concerns about inadequate access to physician services in SNFs to meet the current Medicare mandate. Furthermore, given the increased acuity and medical complexity of patients discharged to SNFs,19 the thirty-day requirement may be too liberal. On the other hand, the limited number of providers does not necessarily preclude timely medical assessment. For example, a growing proportion of SNF physicians and advanced practitioners focus their practice on SNF care,18 which may result in better availability of these practitioners to evaluate patients after discharge from the hospital to a SNF.

A necessary first step in exploring the possibility that ensuring a timely initial medical assessment might be one way to improve care outcomes is to document how frequently the initial medical assessment by a SNF physician or advanced practitioner is missing or delayed beyond a defined point—and if it is, in which subpopulations—and to compare the outcomes for patients who do and do not receive these visits in a timely manner. To do so, we analyzed fee-for-service Medicare claims for all beneficiaries discharged from hospitals to SNFs in the period January 2012–October 2014. Our objective was to measure the timing of initial physician or advanced practitioner evaluation of patients transferred from hospitals to SNFs and to identify facility- and patient-level factors associated with delayed evaluation. We also measured outcomes (rehospitalization, successful discharge to community, and death) of patients with and without physician or advanced practitioner visits during the SNF stay. We did not attempt to establish causality between visits and outcomes. Rather, our goal was to describe current practice behaviors to identify areas where interventions could improve postacute care outcomes.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCES AND STUDY SAMPLE

Our primary data sources were Medicare claims data for the period January 2011–October 2014, including the 100 percent Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file, Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File, and Medicare Carrier File. These data were supplemented with information from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) (which contains detailed clinical assessments on patients in Medicare-certified SNFs) and the Provider of Services file (which contains data on SNF characteristics).

We used these data to create a cohort of fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries discharged from an acute care hospital to a SNF in the period January 2012–October 2014. We excluded beneficiaries younger than age sixty-five and those not enrolled in Medicare Parts A and B for the duration of the hospital and SNF stays and 60 days thereafter. We also excluded patients with any SNF stays in the previous 365 days because those patients may be familiar to SNF physicians and may therefore be seen later than new SNF patients are. We conducted sensitivity analyses including the stays that were preceded by another SNF stay in the previous 365 days.

STUDY OUTCOMES AND KEY VARIABLES

Our primary variable of interest was time to first physician (or advanced practitioner) visit, defined as any submitted claims for SNF services (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes 99304–99310, 99315, 99316, and 99318) or office visits (HCPCS codes 99201–99205 and 99211–99215) in the Medicare Carrier file starting from the date of SNF admission in the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file. We included office visits to account for post-hospitalization follow-up care that was provided by physicians who saw patients in their clinics or offices during the patients’ SNF stays. We included claims for visits by advanced practitioners because evidence suggests that they provide high-quality primary care and increasingly substitute for physicians in providing services, especially in shortage areas,20,21 and because we wanted to provide conservative estimates that captured cases in which advanced practitioners collaborated with physicians not available to perform a full assessment themselves. Although the initial assessment of patients admitted to a SNF is mandated to be conducted by a physician, as noted above, advanced practitioners may conduct necessary focused visits with new patients prior to the initial assessment by a physician.16

Our secondary variable of interest was the receipt of a physician (or advanced practitioner) visit during the SNF stay observed in the Medicare Carrier file. This was recorded as a dichotomous variable set to 1 if we observed one or more claims with the above-mentioned service codes on any day from the SNF admission through the discharge date.

Other variables measured were patient demographic characteristics (age at admission, sex, race, and dual eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid), Elixhauser comorbidities22 and other clinical characteristics,23 and SNF characteristics. Clinical variables in addition to Elixhauser comorbidities included the number of hospitalizations and intensive care unit stays in the prior year; index hospital length-of-stay (defined as the length of hospital stay immediately preceeding SNF admission, in days); eligibility for Medicare because of disability or end-stage renal disease; whether the acute care stay was for a medical or surgical principal diagnosis; functional status, measured by the degree of loss of four activities of daily living (eating, using the toilet, bed mobility, and transferring); and score on the MDS, version 3.0, Cognitive Function Scale. The scale is a single measure that uses a combination of the Brief Interview for Mental Status items and cognitive assessment questions answered by staff members that was developed to address the problem of missing responses to questions on the interview for patients unable to participate in it.24 SNFcharacteristics included size (small: fewer than 100 beds; medium: 100–199 beds; or large: 200 or more beds), ownership (profit, nonprofit, or government), whether the facility was hospital based (owned by a hospital but not necessarily located on its campus),25 urban versus rural, geographic region of the US, and whether the facility was part of a chain.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analyses were conducted at the SNF-stay level. Outcomes were modeled as a function of the above-mentioned SNF and patient covariates, with fixed effects for year. Negative binomial models were estimated for the count outcome of days to first visit, and logistic regression was used to model whether any visit occurred as a function of patient and SNF characteristics. The Huber-White sandwich estimator was used in all regressions to account for clustering of observations within SNFs.26

We conducted three additional analyses. First, we reestimated the models including the subgroup of patients who had SNF stays in the preceding 365 days. Second, we modeled the association between patients’ cognitive impairment and visits within facilities using SNF fixed effects. To do so, we used linear probability models to estimate the adjusted probability of any visit as a function of the patient and SNF characteristics described above. By including SNF fixed effects, we aimed to estimate the role of cognitive impairment while controlling for unobserved heterogeneity in patient case-mix and other factors across facilities. Lastly, we compared the unadjusted rates of seven- and thirty-day rehospitalizations and deaths and successful discharge to the community between stays with and without a physician or advanced practitioner visit. Rehospitalizations and successful discharges to the community were measured using previously described methods.27

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 14.1. The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Privacy Board.

LIMITATIONS

The study had a number of limitations. First, there were likely some observed and unobserved confounders of the relationship between physician or advanced practitioner visits and patient and facility characteristics that were unaccounted for. For example, nurse and physical therapist staffing levels may be associated with visits by other clinicians but were not included in this analysis.

Second, the use of fee-for-service Medicare claims precluded the generalizability of our findings to Medicare Advantage beneficiaries or non-Medicare beneficiaries, though Medicare is the payer for most postacute SNF care in the US.

Third, we could not measure care provided but not billed to Medicare. For example, clinicians might participate in discussions about care plans with SNF staff and perform aspects of transitional care but be unable to bill for their services if they do not include a required component under Medicare (such as a physical exam).

Study Results

Of the 2,392,753 SNF stays that took place in the period January 2012–October 2014, 10.4 percent had no associated SNF or office-based physician or advanced practitioner visits during the SNF stay. Stays without a visit had a median duration of eleven days (interquartile range: 4–21). Of the remaining 2,143,887 stays with at least one visit, 94.9 percent had visits in the SNF, and 5.1 percent had office visits. Generalist physicians (those in internal medicine, general or family practice, or geriatrics specialties) performed 77.0 percent of the initial SNF visits, while 13.0 percent were performed by nurse practitioners, 2.5 percent by physician assistants, and the remaining 7.5 percent by other specialists.

TIMING OF FIRST VISIT

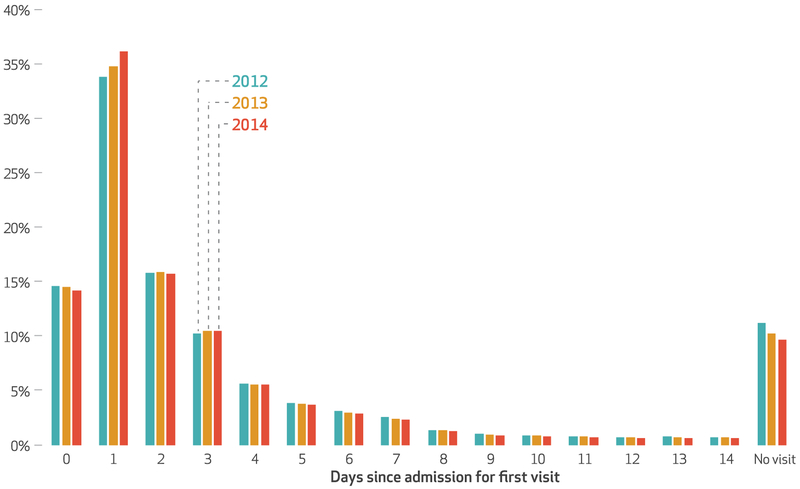

The distributions of first visits by time from date of admission to the SNF were similar for the three years in the study period (exhibit 1). During the stays with any visits, the first visit occurred within a day of admission in about half of the stays, with 79.8 percent of visits taking place in the first four days of the SNF stay.

Exhibit 1.

Percent of stays in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) after discharge from an acute care hospital with a first postadmission visit by a physician or advanced practitioner, by number of days since SNF admission, 2012–14

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare Part B claims data from the Carrier File for 2,392,753 SNF stays by fee-for-service beneficiaries with both Part A and Part B coverage in the period January 2012–October 2014. NOTES Fewer than 4 percent of stays had a first visit more than fourteen days after SNF admission, and those stays are not shown in the exhibit. “No visit” refers to percent of all stays with no physician or advanced practitioner visit billed for between admission and discharge from the SNF. The proportion of stays with no visits decreased from 11.2 percent in 2012 to 9.7 percent in 2014 (p value for trend <0:01).

TIMING OF VISITS BY PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

Patients with a longer index hospital length-of-stay or with critical care stays in the prior year were slightly more likely to have a SNF visit and were seen sooner, compared to patients with shorter index hospital lengths-of-stay or no critical care stays in the prior year (exhibit 2). Patients with a higher Elixhauser Comorbidity Index were less likely to have no visits compared to patients with a lower index, but the difference in time from admission to the first visit did not differ between the two groups. Patients who were older or were more functionally impaired (that is, had a higher degree of loss of activities of daily living) were more likely to have a SNF visit but were seen later, compared to younger or less functionally impaired patients. Patients with cognitive impairment were more likely not to have a SNF visit and were seen later, on average, than those without cognitive impairment.

Exhibit 2.

Number and percent of skilled nursing facility (SNF) stays, percent of stays with no visit from a physician or advanced practitioner, and average number of days from SNF admission to the first visit, by patient and facility characteristics

| Characteristic | No. of stays | % of stays | No visit (%) | Avg. time to first visit (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 66–75 | 577,096 | 24.1 | 11.4 | 3.6 |

| 76–85 | 966,758 | 40.4 | 10.5 | 3.9 |

| More than 85 | 848,899 | 35.5 | 9.6 | 4.1 |

| Racea | ||||

| White | 2,099,873 | 87.8 | 10.6 | 3.9 |

| Black | 196,661 | 8.2 | 9.1 | 3.7 |

| Other | 92,047 | 3.9 | 9.8 | 3.7 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 813,607 | 34.0 | 10.7 | 3.8 |

| Female | 1,579,146 | 66.0 | 10.3 | 4.0 |

| Cognitive functioningb | ||||

| Not impaired | 1,320,149 | 55.2 | 8.7 | 3.5 |

| Mildly impaired | 574,271 | 24.0 | 13.3 | 4.0 |

| Moderately impaired | 420,165 | 17.6 | 11.1 | 4.8 |

| Severely impaired | 78,168 | 3.3 | 14.0 | 4.6 |

| Score measuring degree of loss in four ADLsc | ||||

| Less than 8 | 1,129,379 | 47.2 | 11.8 | 3.5 |

| 8 or more | 1,263,374 | 52.8 | 9.1 | 4.2 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | ||||

| Fewer than 7 | 1,304,050 | 54.5 | 10.8 | 4.0 |

| 7 or more | 1,088,703 | 45.5 | 9.9 | 3.8 |

| Any intensive care unit stay in prior year | ||||

| No | 1,721,974 | 71.8 | 10.6 | 4.0 |

| Yes | 670,779 | 28.2 | 10.1 | 3.6 |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index | ||||

| Less than 8 | 1,186,805 | 49.6 | 10.6 | 3.9 |

| 8 or more | 1,205,948 | 50.4 | 10.2 | 3.9 |

| FACILITY CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Hospital based | ||||

| No | 2,210,349 | 92.4 | 10.1 | 4.0 |

| Yes | 182,404 | 7.6 | 14.3 | 2.3 |

| Part of a chain | ||||

| No | 1,040,827 | 43.5 | 10.3 | 3.7 |

| Yes | 1,351,926 | 56.5 | 10.5 | 4.1 |

| Rural location | ||||

| No | 1,970,871 | 82.4 | 7.6 | 3.2 |

| Yes | 421,882 | 17.6 | 23.7 | 8.1 |

| Region | ||||

| Midwest | 625,066 | 26.1 | 13.8 | 5.3 |

| Northeast | 543,181 | 22.7 | 5.2 | 2.2 |

| South | 882,256 | 36.9 | 11.0 | 4.1 |

| West | 342,250 | 14.3 | 11.0 | 3.8 |

| Ownership | ||||

| For profit | 1,636,079 | 68.4 | 10.0 | 4.0 |

| Government | 79,738 | 3.3 | 16.8 | 5.2 |

| Nonprofit | 676,936 | 28.3 | 10.5 | 3.5 |

| Size | ||||

| Large (200 or more beds) | 283,482 | 11.9 | 5.4 | 2.6 |

| Medium (100–199 beds) | 1,317,824 | 55.1 | 9.4 | 3.9 |

| Small (fewer than 100 beds) | 791,447 | 33.1 | 13.8 | 4.4 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare Part B claims data from the Carrier File for 2,392,753 SNF stays by fee-for-service beneficiaries with both Part A and Part B coverage during the period January 2012–October 2014. NOTES “Admission” refers to admission to a SNF after discharge from an acute care hospital. “No visit” is explained in the notes to exhibit 1. Unadjusted time to first visit was measured in days from the day of admission to the SNF after discharge from an acute care hospital. With the exception of no significant difference in the number of days from SNF admission to first visit for patients with Elixhauser index less than 8, compared to an index of 8 or more, all comparisons within patient and facility characteristics were significantly different (p < 0:001).

For 4,172 stays (0.17 percent of the sample), patient race was unknown.

According to the Minimum Data Set, version 3.0, Cognitive Function Scale, as explained in text.

A higher score represents greater degree of loss of ability to perform four activities of daily living (ADLs) (eating, using the toilet, bed mobility, and transferring).

TIMING OF VISITS BY FACILITY CHARACTERISTICS

Hospital-based SNFs had a higher proportion of stays with no visits, compared to other SNFs (exhibit 2). Rural SNFs also had a much higher percentage of SNF stays without visits (23.7 percent) than was the case in urban or suburban SNFs (7.6 percent). SNFs in the Northeast had half as many stays with no visits as SNFs in other regions. Large SNFs had the lowest percentage of missing visits (5.4 percent), while small SNFs had the highest percentage (13.8 percent). Trends in the timing of first visits by SNF characteristics were generally consistent with these observations. Specifically, visits occurred later in SNFs that were small (versus large) rural (versus urban or suburban), and in the South or Midwest (versus the Northeast).

ADJUSTED ANALYSES

In multivariable models, facility-level factors and patients’ cognitive impairment were associated with the differences in physician or advanced practitioner visits during SNF stays. Patients with more severe cognitive impairment were less likely to be seen by a physician or advanced practitioner during the SNF stay and were more likely to experience a delay between admission and the first visit (exhibit 3). Visits were also absent or delayed in facilities that were small and in those that were located in rural settings and outside of the Northeast.

Exhibit 3.

Odds ratio (OR) of a patient’s having a physician or advanced practitioner visit during a stay at a skilled nursing facility (SNF), and incidence rate ratio (IRR) of the number of days from SNF admission to first visit, by patient and facility characteristics

| Characteristic | OR | IRR |

|---|---|---|

| PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Race (ref: white) | ||

| Black | 1.12 | 0.96 |

| Other | 1.06 | 0.94 |

| Sex (ref: male) | ||

| Female | 1.02 | 1.02 |

| Cognitive functioninga (ref: not impaired) | ||

| Mildly impaired | 0.57 | 1.01 |

| Moderately impaired | 0.61 | 1.09 |

| Severely impaired | 0.40 | 1.02 |

| FACILITY CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Ownership (ref: freestanding facility) | ||

| Hospital-based facility | 0.92 | 0.58 |

| Facility part of chain (ref: no) | ||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.98 |

| Location (ref: urban or suburban) | ||

| Rural | 0.30 | 2.16 |

| Region (ref: Northeast) | ||

| South | 0.60 | 1.63 |

| Midwest | 0.46 | 2.01 |

| West | 0.50 | 1.67 |

| Profit status (ref: not for profit) | ||

| For profit | 1.07 | 0.98 |

| Size (ref: small) | ||

| Medium | 1.26 | 0.92 |

| Large | 1.76 | 0.76 |

| Year (ref: 2012) | ||

| 2013 | 1.10 | 0.97 |

| 2014 | 1.14 | 0.93 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of Medicare Part B claims data from the Carrier File for 2,392,753 SNF stays by fee-for-service beneficiaries with both Parts A and B coverage during the period January 2012–October 2014. NOTES “Admission” refers to admission to a SNF after discharge from an acute care hospital. In addition to the variables in the exhibit, ORs and IRRs were adjusted for patient age, Elixhauser comorbidities, hospitalizations or intensive care unit stays in the prior year, eligibility for Medicare because of disability or end-stage renal disease, whether the acute care stay was for a medical or surgical principal diagnosis, and functional status. All ORs and IRRs were significantly different from 1 (p < 0:001). Size (number of beds) is defined in exhibit 2.

According to the Minimum Data Set, version 3.0, Cognitive Function Scale, as explained in text.

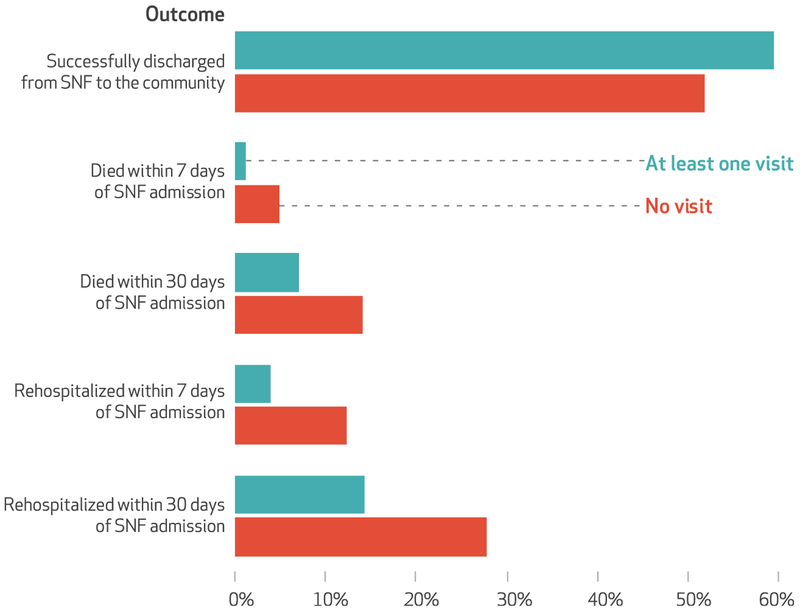

PATIENT OUTCOMES OF STAYS WITH AND WITHOUT A PHYSICIAN VISIT

Of “no visit” patients, 27.9 percent were readmitted to a hospital, and 14.2 percent died within thirty days of SNF admission (exhibit 4). Of patients whose stays included one or more visits, 14.3 percent were readmitted to a hospital, and 7.2 percent died within thirty days of SNF admission. Compared to stays with at least one visit, those without any visits had a lower rate of successful discharge to the community (51.9 percent versus 59.6 percent).

Exhibit 4.

Unadjusted percent of patients in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) at risk for a given outcome who experienced it, by whether or not they had any physician or advanced practitioner visit

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the Minimum Data Set, version 3.0, and Medicare Part A claims data from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files for 2,392,753 SNF stays by fee-for-service beneficiaries with both Part A and Part B coverage in the period January 2012–October 2014. NOTES “No visit” refers to the stays with no physician or advanced practitioner visit billed for between admission and discharge from the SNF. A visit was defined as any submitted claims for SNF services or office visits using the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes listed in the text from the Medicare Carrier file. A successful discharge from a SNF to the community is a discharge from the SNF within 100 days of admission that is not followed by death, rehospitalization, or readmission to the SNF within thirty days of the discharge. The categories are not mutually exclusive. All comparisons between the two groups (patients with and without any physician or advanced practitioner visit) were significantly different (p < 0:001).

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

The first visit occurred slightly later during repeat SNF stays compared to new stays (see online appendix exhibit A1).28 The observed differences by patient and facility characteristics for missing and delayed visits were generally similar across the new and repeat stays. Repeat stays were more likely to have no visits and had longer delays between SNF admission and the first visit, compared to new stays (appendix exhibits A2–A4).28 When repeat stays were included in the sample, adjusted models estimated associations between patient and facility characteristics that were similar to estimates in the main models (results from the models are included in appendix exhibits A5 and A6).28 And compared to the main models, fixed-effects models estimated similar effects of patient cognitive impairment on the presence of physician or advanced practitioner visits (appendix exhibit A7).28 Patients with cognitive impairment were less likely to be evaluated by a physician or advanced practitioner during their SNF stay (4.8 percent less likely for mild, 3.4 percent for moderate, and 7.5 percent for severe cognitive impairment compared to no impairment; p < 0:001).

Discussion

Ninety percent of patients discharged from an acute care hospital to postacute care in a skilled nursing facility were evaluated by a physician or advanced practitioner after SNF admission, and a majority of assessments were completed within four days of admission. Nevertheless, about one in ten patients were not assessed during the SNF stay, and visits in rural or small SNFs and to patients with cognitive impairment were delayed. The differences in the likelihood of being seen and the timing of the visit by patient clinical characteristics that confer greater risk of poor SNF outcomes were small relative to the differences by facility-level characteristics and geography. One notable exception to this was that despite representing a particularly vulnerable population, patients with cognitive impairment were seen later in the course of their SNF stays compared to cognitively intact patients.

Overall, these findings suggest that missing and delayed medical care occurs during a time when patients are discharged from an acute care hospital to postacute care in a SNF and are particularly vulnerable to poor outcomes. While the current study does not suggest why this happens, previous work has identified a number of possible explanations. First, physicians have historically been reluctant to practice in SNFs, citing poor reimbursement, greater exposure to malpractice litigation, and other concerns.17,29 Furthermore, physicians who practice in SNFs report discrepancies between optimal versus actual visit time for SNF patients, which suggests that the time allotted to SNF visits may be inadequate for this high-need population.30 Second, a lack of evidence-based triage protocols for the evaluation of recently admitted SNF patients may exacerbate the effects of personnel shortages. Third, inadequate staffing or training of direct care staff may preclude the implementation of triage protocols or similar processes. Fourth, poor practices by the discharging hospitals (for example, inaccurate discharge records or late-evening discharges) may result in early rehospitalizations that occur before a patient can be evaluated by a SNF physician or advanced practitioner. Fifth, some of the SNF stays may represent long-term nursing home residents who were readmitted to a SNF under the Medicare Part A benefit after an acute hospital stay. Presumably SNF physicians are familiar with those patients and may provide the necessary transitional care at a later time, compared to patients newly admitted to a SNF. In fact, we observed that patients were seen slightly sooner after admission for a new SNF stay, compared to a repeat stay.

More research is needed to identify the underlying reasons for the missed and delayed first visits. In addition, research is needed to understand the marginal effect of the initial medical assessment by a physician or advanced practitioner relative to other factors (for example, nursing care quality or staffing) on outcomes among SNF patients receiving postacute care.

As patients discharged from hospitals to SNFs for postacute care tend to be increasingly more medically complex,19,31 they may require timely physician assessment that is not incentivized by current regulatory or payment policies. In contrast, Medicare provides additional reimbursement to physicians for postdischarge services— such as reviewing discharge information, arranging tests or referrals, and reconciling medications—for patients discharged from the hospital to the community (that is, home).32 Although the codes are not widely used, patients who received these services had lower mortality and costs during the following month.33 An analogous approach could represent one potential lever to encourage prompt assessment of SNF patients. Furthermore, health systems transitioning from fee-for-service to value-based payment may be more willing to reallocate resources and experiment with new care models to improve population-level outcomes in the long run. A survey of hospitals that participated in bundled payment models found that many partnered with local SNFs by forming referral networks.4 The recent emergence of physicians and advanced practitioners who practice exclusively in SNFs18 (that is, “SNFists”) may represent the consequences of local efforts to improve access to timely medical care in SNFs.

Conclusion

Timely evaluation of medically complex patients by a physician or advanced practitioner did not take place for some patients after their transfer from acute hospital care to postacute SNF care. The differences were small for traditional markers of clinical severity compared to the differences by SNF characteristics, which suggests that timely access to physician or advanced practitioner care after hospital discharge to a SNF depends in large part on local practice patterns rather than clinical needs. Understanding the underlying reasons for variability in initial SNF visits may well prove important in efforts to improve patient outcomes and may be particularly relevant to current efforts to promote value-based purchasing in postacute care. ▪

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Seattle, Washington, June 25, 2018. Kira Ryskina’s work on this study was supported by a National Institute on Aging Career Development Award (No. K08-AG052572). Robert Burke’s work was supported by a Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award (No. 1IK2 HX001796). The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Kira L. Ryskina, Assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia.

Yihao Yuan, Statistical analyst at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania..

Shelly Teng, Research assistant with the Division of General Internal Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania..

Robert Burke, Core investigator at the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, Corporal Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center, in Philadelphia, and an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania..

NOTES

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy [Internet]. Washington (DC): MedPAC; 2017. March [cited 2019 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport224610adfa9-c665e80adff00009edf9c.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014; 312(15):1542–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu JM, Patel V, Shea JA, Neuman MD, Werner RM. Hospitals using bundled payment report reducing skilled nursing facility use and improving care integration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(8):1282–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kane RL, Keckhafer G, Flood S, Bershadsky B, Siadaty MS. The effect of Evercare on hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1427–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reuben DB. Physicians in supporting roles in chronic disease care: the CareMore model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):158–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim LD, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg MB. Impact of a connected care model on 30-day readmission rates from skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouslander JG, Naharci I, Engstrom G, Shutes J,Wolf DG, Rojido M, et al. Hospital transfers of skilled nursing facility (SNF) patients within 48 hours and 30 days after SNF admission. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016; 17(9):839–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeCoster V, Ehlman K, Conners C. Factors contributing to readmission of seniors into acute care hospitals. Educ Gerontol. 2013;39(12):878–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lima JC, Intrator O, Wetle T. Physicians in nursing homes: effectiveness of physician accountability and communication. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(9):755–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen BT, Halbert RJ, Hart K, Diniz MA, Isonaka S, Black JT. The Enhanced Care Program: impact of a care transition program on 30-day hospital readmissions for patients discharged from an acute care facility to skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, Sircar M, Travison TG, Abrams A, et al. Improving transitions to post-acute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine. Improving the quality of long-term care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karuza J, Katz PR. Physician staffing patterns correlates of nursing home care: an initial inquiry and consideration of policy implications. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(7):787–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy C, Epstein A, Landry L-A, Kramer A, Harvell J, Liggins C. Physician practices in nursing homes: final report [Internet]. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2006. April [cited 2019 Feb 12]. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/74516/phypracfr.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy C, Palat SI, Kramer AM. Physician practice patterns in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007; 8(9):558–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz PR, Karuza J, Kolassa J, Hutson A. Medical practice with nursing home residents: results from the National Physician Professional Activities Census. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(8):911–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryskina KL, Polsky D, Werner RM. Physicians and advanced practitioners specializing in nursing home care, 2012–2015. JAMA. 2017; 318(20):2040–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Patient and hospitalization characteristics associated with increased postacute care facility discharges from US hospitals. Med Care. 2015;53(6):492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, Martsolf G. Rural and nonrural primary care physician practices increasingly rely on nurse practitioners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):908–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caprio TV. Physician practice in the nursing home: collaboration with nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Ann Longterm Care. 2006;14(3):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: the AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris JN, Moore T, Jones R, Mor V, Angelelli J, Berg K, et al. Validation of long-term and post-acute care quality indicators: final report [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2003. June 10 [cited 2019 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/NHQIFinalReport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare skilled nursing facility manual: section 201.2 [Internet]. Washington (DC): HHS; 2000. September 28 [cited 2019 Feb 11]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R367SNF.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980; 48(4):817–38. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abt Associates. Nursing Home Compare claims-based quality measure technical specifications: final [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2018. September [cited 2019 Feb 11]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/Nursing-Home-Compare-Claims-based-Measures-Technical-Specifications.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 29.Katz PR, Karuza J, Intrator O, Mor V. Nursing home physician specialists: a response to the workforce crisis in long-term care. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(6):411–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caprio TV, Karuza J, Katz PR. Profile of physicians in the nursing home: time perception and barriers to optimal medical practice. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(2):93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyler DA, Feng Z, Leland NE, Gozalo P, Intrator O, Mor V. Trends in postacute care and staffing in US nursing homes, 2001–2010. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(11):817–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Transitional care management services [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2016. December [cited 2019 Feb 13]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bindman AB, Cox DF. Changes in health care costs and mortality associated with transitional care management services after a discharge among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(9): 1165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.