Abstract

Many volatile organic chemicals (VOCs) have not been tested for sensory pulmonary irritation. Development of in vitro non-animal sensory irritation assay suitable for large number of chemicals is needed to replace the mouse assay. An adverse outcome pathway (AOP) was developed to provide a clear description of the biochemical and cellular processes leading to toxicological effects or an adverse outcome. The AOP for chemical sensory pulmonary irritation was developed according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development guidance including the Bradford Hill criteria for a weight of evidence to determine the confidence of the AOP. The proposed AOP is based on an in-depth review of the relevant scientific literature to identify the initial molecular event for respiratory irritation. The activation of TRPA1 receptor (transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily A, member 1) is identified as the molecular initial event (MIE) leading to sensory irritation. A direct measure of TRPA1 activation in vitro should identify chemical sensory irritants and provide an estimate of potency. Fibroblasts expressing TRPA1 are used to determine TRPA1 activation and irritant potency. Based on preliminary analysis we report a apparent linear relationship between the in vivo RD50 and the in vitro pEC50 values to support this hypothesis. We propose that this in vitro assay after additional analysis and validation could serve as a suitable candidate to replace the mouse sensory irritation assay.

Keywords: Sensory pulmonary irritation, TRPA1, neurogenic inflammation, TRPV1, non-animal test

1. Introduction

Inhalation exposure to gases and vapors frequently occurs in occupational and ambient environments. Each year new volatile organic chemicals (VOCs) are introduced into commercial use as solvents, vapors or gases and are subsequently incorporated into household consumer products, and ultimately discharged into the environment. Many of these VOCs are not well characterized with respect to irritation.

The respiratory tract is richly innervated by trigeminal nerves and their nerve endings in the epithelial tissue, nasal mucosa, expressing transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels (Fujitta et al., 2008; Dhaka et al., 2009; Bessac and Jordt, 2008; Inoue and Bryant, 2005; Bautista et al., 2006). Activation of TRP ion channels is involved in the detection of irritants present in the environment. Exposure to chemicals by inhalation causes trigeminal chemoreception (pain, nasal pungency, eye irritation, decreases in respiration rate) and is dependent on the concentration and the frequency of exposure. TRPA1 (transient receptor potential ankyrin-repeat 1) is a key regulator of neuropeptide release and neurogenic inflammation leading to increased mucus production, nasal obstruction, sneezing, and coughing (Belvisi et al., 2011; Bautista et al., 2013; Caceres et al., 2009).

The term sensory irritation (Alarie,1981) is frequently used to describe adverse health effects caused by compounds interacting with peripheral nerve fibers. TRPA1 and TRPV1 are two key receptors, or ion channels are present in the nerve endings in the upper airways that mediate sensory irritation as part of a physiological response to make the subject aware of the presence of chemicals and initiate several defensive biological responses. A wide range of chemicals activate TRPA1, while acids and a limited number of chemicals activate TRPV1 (Bessac and Jordt, 2010). The activation of TRPA1 has been characterized as a gatekeeper of inflammation and is an important endpoint in the regulation of exposure to VOCs (Bautista et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2016, 2017).

Chemicals that are irritants can be identified and characterized, in part, based on the following: physical and chemical characteristics, the result of classical in vitro skin and eye corrosion irritation assays (Bos et al., 2002), and data obtained from in vivo sensory irritation tests (Alarie, 1966, 1981, and Alarie et al.,1995). Acute inhalation injury by corrosive chemicals is more overt and therefore more easily quantified in animal studies. Corrosion is identified based on histological necropsy observations, including cell necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and edema. The physical and chemical characteristics are frequently predictive for corrosive chemicals but known sensory irritants have a wide range of physical and chemical characteristics that are, in general, not predictive for sensory irritation.

Test systems to determine sensory irritation is limited to a single assay, the classical in vivo sensory irritation test presenting the data as a dose causing a 50% reduction in respiration rate or RD50 (Alarie, 1966, 1973, 1981, Alarie et al., 1995, Schaper M., 1993). Many VOCs were classified as sensory irritants based on results from this assay. The utility and validity of the RD50 assay for sensory irritation and subsequent development of exposure limits have been questioned based on the extrapolation of animal data to humans (Bos et al., 1991, 2002). The data did not correlate with histopathological changes or corrosion of the respiratory tract. However, as pointed out by Kuwabara et al. (2007) and Nielsen and Wolkoff (2017), the RD50 assay is designed to evaluate sensory irritation potential and not corrosive effects. The in vivo sensory assay (RD50) is proposed as acceptable for developing guidance levels to protect the public based on the correlation of sensory irritants of 0.033xRD50. In addition, Nielsen and Wolkoff (2017) propose a systematic approach that includes an evaluation of the number of mice and the strain, exposure concentrations, exposure-response relationships, and the mode-of-action in mice and humans for using animal data to set air quality guidelines.

To develop non-animal testing, improved or additional assays are needed to determine if chemicals are sensory irritants. Ideally, the assays should be an in vitro system, suitable to measure a reasonably large number of chemicals, based on biochemical processes, and chemical structure activity. A clear understanding of the biochemical and cellular mechanisms of receptor activation and signal transduction pathways for sensory irritation should point the way for the development of assays that can be applied for risk assessment of inhalable chemicals. An Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) initiative was developed for collaboration between the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), and the United States Army Engineer Research and Development Center. The outcome of this effort is the Adverse Outcome Pathway Knowledge Base developed as a tool for risk assessment. The AOP is designed to provide a clear description of the mechanisms underlying biochemical events and modes of action leading to adverse effects. Here we report the development of an AOP for sensory irritation that should provide guidance in developing in vitro assays for assessing and quantitating sensory irritation. This AOP (AOP #196) is in the AOP wiki under development, not open for comment and can be found at https://aopwiki.org/.

2. Approach

An Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) wiki was developed based on Villeneuve et al., 2014 and the OECD guidelines (OECD, 2012a, 2012b, 2016, 2018). An AOP has a single starting point; the molecular initiation event and only one endpoint or adverse outcome. All AOPs follow the same format: a single molecular initiation event (MIE), progress through several key events and culminate in a single adverse outcome either in an individual or a population (OECD, 2012a, 2012b, 2016, 2018). For VOC induced irritation, the binding to sensory receptors was determined to be the molecular initiation event (MIE), and the adverse outcome (AO) is respiratory irritation. Identification of biochemical and cellular events between the molecular initiation event and the adverse outcome which is composed of a series of intermediate processes and key biological events was achieved by an in-depth survey of comprehensive and appropriate scientific literature, using PubMed, and Google Scholar as the main resource along with reference tree searching.

2.1. Relevant background information

2.1.1. Biochemical and Cellular Basis for Sensory Irritation

Chemesthesis or sensations produced by chemical exposure occur through trigeminal nerve fiber endings present in the nasal cavity and airways and is mediated by a family of ion channel receptors located in the nerve endings. Present in the respiratory tract are neurons with receptors that interact with inhaled chemicals. The ASIC receptors (Acid-Sensing Ion Channels) detect changes in acidity between pH 6 to 7. ASIC receptors are ubiquitously expressed in both the A and C fiber sensory neurons. For example, inhalation of acetic acid activates the ASICs receptors (Bessac and Jordt, 2010). Activation of these receptors plays a role in the pain response that occurs on the inhalation of chemicals altering cellular acidity.

TRPV1 is a member of the TRP family ion channel receptors also located in the sensory fibers in the lining of the trachea, bronchi, and alveoli. TRPV1 is only activated by few chemicals some irritants found in foods, including chili peppers (capsaicin), black pepper, garlic for example, and is also activated by acidic conditions in the respiratory tract. Activation of TRPV1 by capsaicin causes a respiratory tract irritation inducing sneezing, cough, increased mucus secretion, and pain. Activation of the TRPV1 receptor can also desensitize the airway response to other irritants (Bessac et al., 2008, 2010).

The TRPA1 receptors are present in the C-fiber nerve endings and are directly activated by volatile organic chemicals and are essential for the irritant response (see below). TRPA1 receptor reacts with or is activated by a wide range of natural chemicals and many environmental chemicals and irritants including dust, cigarette smoke, vapors, and common air pollutants. Electronic cigarettes can also produce potentially reactive aldehydes and with their increasing use may become an important source of pulmonary irritants (Rowell and Tarran, 2015). The activation of the TRPA1 channel also causes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines at the site of the interaction with the chemicals (Bessac et al., 2010). TRPA1 receptors are also present in skin suggesting that skin could be used as a surrogate for the respiratory tract in in vitro investigation of irritation by chemicals (Jordt et al., 2004). The range of chemicals activating TRPA1 is very diverse with the chemical reactivity and not the structure important for TRPA1 agonist (Peterlin et al., 2007).

Sensory detection of chemicals causes the following sensations: piquancy, tingling, prickling, irritation, stinging, burning, and pain, or may induce involuntary, autonomic, and motor reflexes (Bessac and Jordt, 2010). In addition, the TRP ion channels are implicated in the cough reflex, a response that is frequently observed upon inhalation of an irritant. TRPA1 and TRPV1 co-localize in the sensory nerve ending (Bessac and Jordt, 2008) and are expressed in the small diameter neurons in the trigeminal nerves located in the respiratory tract. The vagal jugular and vagal nodose ganglia project TRPA1 expressing C-fibers into the airways of the pulmonary system (Belvisi et al., 2011). TRPV1 is localized with the substance P, and NK1 receptors in trigeminal nerve endings and some evidence suggests they interact with the TRP receptors (Naono-Nakayama et al., 2010). TRPA1 is expressed in many species with the activation by electrophiles conserved across species.

On activation of trigeminal neurons, the release of substance P (SP), a peptide that stimulates an inflammatory response is characterized by an increase in mucus secretion, plasma extravasation, and vasodilation. The nerve endings expressing neuropeptide CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) in the respiratory tract are in the same regions as SP, and CGRP is frequently released with SP after stimulation (Russell et al., 2014). Nerve endings expressing CGRP are also located in the walls of small blood vessels and after release from nerves, cause prolonged vasodilation. CGRP has two forms, alpha, and beta with the expression of the alpha form abundant in the nerve fibers, respiratory tract mucosa, and pulmonary epithelium. Activation of the TRPA1 but not TRPV1 ion channel receptors in the airways can cause the release of CGRP (Kichko et al., 2015.)

2.1.2. TRPA1 activation is essential for VOC induced irritation

Activation of the TRPA1 channel appears to be the determinate for most of the response of the pulmonary system to inhaled irritants (Bessac et al., 2009; Belvisi et al., 2011; Caceres et al., 2009). Many known irritants including isocyanates, cigarette smoke extracts, ozone, H2O2, and aldehydes are shown to increase calcium flux, as measured by TRPA1 transfected HEK293 but not in control HEK293 cells. Ca2+ flux measured in isolated trigeminal neurons after incubation with an irritant chemical was significantly reduced in neurons isolated from TRPA1 deficient mice (TPRA1 −/−) compared to wild-type mice (Taylor-Clark et al., 2009; Taylor and Undem, 2010). Furthermore, the irritation responses including cough, pain, and inflammation are absent or decreased after exposure to irritants in TRPA1−/− mice. TRPA1 deficient mice show absence from the sensory irritation caused by alkyl isothiocyanate, toluene diisocyanate, or formaldehyde (McNamara et al., 2007; Taylor-Clark et al., 2009). In contrast, TRPV1 deficient mice exposed to acrolein do not respond with a decrease in respiration rate but have rates that are like wild-type mice (Symanowicz et al., 2004). The chemical activation of TRPA1 appears to be essential for the irritant response in the respiratory tract after exposure to pulmonary irritants (Belvisi et al., 2011).

2.1.3. TRPA1 and Airway Hyper-reactivity.

Hyper-activation and chronic activation of the TRPA1 appear to contribute to chronic bronchitis, occupational asthma, and other inflammatory respiratory tract diseases associated with exposure to inhaled toxic agents. TRPA1 also appears to be important in allergic sensitivity because as shown in experimental animals, the receptor modulates sensitivity to ovalbumin, an inducer of allergic asthma in experimental animal models (Bessac et al., 2010). Activation of the irritation or nociceptive receptors can lead to increased sensitization to allergic stimuli (Bessac and Jordt, 2008; 2010).

The activation of TRPA1 stimulates the release of inflammatory peptide SP and CGRP; which play a role in the asthmatic and irritation symptoms observed after one-time and frequent exposure to inhaled irritants (Caceres et al., 2009). Exposure to high levels of TRPA1 agonists can induce reactive airway dysfunction syndrome or RADS, characterized by asthma-like symptoms (Brooks et al., 1985). Bessac and Jordt (2008) proposed that exposure to an irritant with activation of TRPA1 may sensitize TRPA1 through inflammatory pathways and thereby establishing a hypersensitivity to other reactive irritants. TRPA1 but not TRPV1 appear to have an important role in allergic airway inflammation and hyper-reactivity associated with asthma. In the ovalbumin mouse model of asthma, TRPA1 (−/−) mice but not TRPV1 (−/−) had reduced mucus, fewer leukocytes in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and lower amounts of inflammatory cytokines. Treatment of mice with tear gas or TRPA1 agonist increased CGRP, SP, and NKA in wild-type mice with greatly reduced levels detected in the alveolar fluid in the TRPA1 (−/−) mice. Likewise, treatment of wild-type mice with ovalbumin also increased levels of NKA with a diminished level in the TRPA1 (−/−) mice. These results indicate TRPA1 may also have a role in the development of asthma after allergen challenge (Caceres et al., 2009).

3. Sensory Irritation Adverse Outcome Pathway

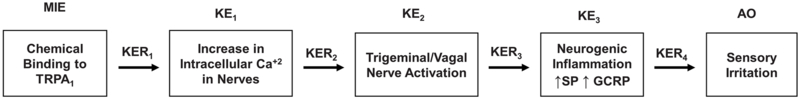

Based on the biochemical and cellular data on sensory irritation described above, an AOP for sensory irritation is proposed as depicted in Figure 1 as a series of biological events.

Figure 1. The temporal sequence of biological events leading the AOP (adverse outcome pathway).

MIE= Molecular initiating event; KE= key events, KER= Key events relationship, AO=Adverse outcome

3.1. Molecular initiating event

The binding of the irritant to the TRPA1 receptor is the initial molecular event leading to an adverse outcome. Chemical irritants have highly diverse chemical structures but can be divided into two groups based on their chemical reactivity. Irritants in the reactive group include endogenous inflammatory lipids, oxidants, and electrophilic agents that react with biomolecules including amino acid residues in proteins (Bessac and Jordt, 2010) and may differ in chemical structure and properties but have in common a reaction with biomolecules. Some members of this reactive group are isocyanates (tear gases), α, β-unsaturated aldehydes, heavy metals, and peroxides. They are very potent irritants that covalently link to and modify to activate the TRPA1 receptor that then initiates the irritation response (Bessac and Jordt, 2010; Bautista et al., 2006, 2013). This type of irritant as illustrated by the tear gases covalently bind to cysteine residues present in the receptor (Macpherson et al., 2007; Brone et al., 2008) and can cause sustained activation of TRPA1 (Macpherson et al., 2007).

Chemicals in the non-reactive group for example alcohols, alkylbenzenes, non-reactive ketones, and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (Jordt et al., 2004), appear to physically but not covalently interact with the receptors and are not as potent as the reactive irritants. For example, THC activates TRPA1 by binding presumably to the active site of TRPA1 (Baraldi et al., 2010). In the epithelial cells lining the airways are the CYP450 family of enzymes that can metabolize chemicals to reactive metabolites (Lanosa et al., 2010) that can bind to TRPA1. For example, styrene and naphthalene that are non-reactive require metabolism to bind receptor in mice and elicit the subsequent reduction in respiratory rate. Differences in the CYP450 family of enzymes between human and mice may contribute to different mice and human responses to some irritants (Lanosa et al., 2010).

3.2. Key Events

3.2.1. KE1. Increase in intracellular Ca2+

The binding of irritant chemicals to the TRPA1 activates the ion channel resulting in an influx of Ca2+ and the increase in intracellular Ca2+ measured in cells by fluorescence dye imaging (Bessac and Jordt, 2010; Brone et al., 2008; Bessac et al., 2009). For reactive irritants, the activation is dependent on the covalent binding of the chemical to cysteines residues in the activated site. The increase in Ca2+ influx detected on incubation with reactive irritants is not observed with mutant TRPA1 proteins with the substitution of three cysteine residues in the active site. In contrast, on incubation of these mutant TRPA1 proteins with non-reactive irritants such as THC, an increase of Ca2+ influx is still observed (Peterlin et al., 2007; MacPherson et al., 2007). Both covalent binding and non-covalent binding of chemical irritants to TRPA1 cause activation of TRPA1 as measured by an increase in intracellular Ca2+ (KER1) shown in Figure 2. In HEK-293 cells expressing TRPA1, a clear concentration dependence was found and the Ca2+ influx also increased with time of exposure to the irritant chemicals indicating a time dependence. The ED50 or the concentration causing a 50% of the maximum increase in Ca2+ influx into cells is reported for approximately 65 chemicals in the Guide to Pharmacology database with data as pED50 or negative log of the molar concentration (Lui et al., 2017). Differences in the pED50 are reported for rat, mouse, and human TRPA1 for some chemicals. In mice and in cultured cells the influx of Ca2+ increased with increasing chemical concentration and time of exposure (Bessac and Jordt 2008, 2010; Bautista et al., 2006; Brone et al., 2008).

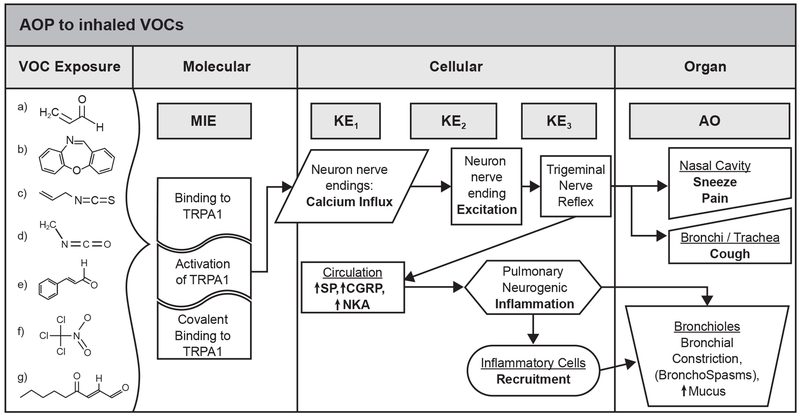

Figure 2. Adverse Outcome Pathway for Sensory Irritation.

Some examples of volatile irritant organic chemicals (VOC) are shown. a) acrolein; b) dibenz[b,f,][1,4]oxazepine(CN); c) cinnamaldehyde; d) methyl isocyanate; e) allyl-isothiocyanate; f) chloropicrin; g) 4-oxo-nonenal.

3.2.2. KE2. Trigeminal nerve excitation

With an increase in intracellular Ca2+, electrophysiological changes occur, and depolarization of sensory neurons or excitation (KER2) can be observed (Jordt et al., 2004). Treatment of dorsal root ganglia (DRG neurons) isolated from rats with tear gases, thioisocyanate, or THC (Jordt et al., 2004; Brone et al., 2008) or treatment of isolated rat and mouse sensory neurons (DRG and nodose neurons) with reactive irritants, oxidants, or reactive lipids (Andersson et al., 2008) results in changes in Ca2+ influx measured by fura-2 dyes, Ca2+ imaging and membrane potentials changes that were both concentration and time-dependent. Furthermore, mouse DRG neurons isolated from mice deficient in TRPA1 (TRPA1 −/−) mice have greatly reduced increases in Ca2+ influx and electrophysiological changes after treatment with several irritants as compared to DRG isolated from wild-type mice. In contrast, DRG neurons isolated from TRPV1 −/− have responses similar to DRG neurons isolated from wild-type mice after treatment with irritants. After exposure to inhaled irritants, TRPA1 −/− mice but not the TRPV1 −/− mice have significantly lower trigeminal/vagal responses than wild-type mice as measured by respiration rate and in the symptoms of irritation; pain, coughing, sneezing. Studies with TRPA1−/− mice strongly supported the critical importance of the trigeminal excitation after activation of TRPA1 receptor in response to irritants (Bessac and Jordt 2008, 2010; Bautista et al., 2006; Brone et al., 2008).

The reduction in respiratory rates after exposure to chemicals at different concentrations measured as reported in Alarie et al. (1981, 1995) can be considered as an estimate of trigeminal nerve excitation in mice after exposure. Studies with TRPA1−/− mice support the hypothesis that trigeminal excitation is dependent on TRPA1. The increase in respiration rates occurs with increasing chemical concentration supporting the sensory assay (RD50) correlation of trigeminal nerve excitation in vivo.

3.2.3. KE3. Neurogenic inflammation

Trigeminal excitation of chemosensory nerve endings in the nasal mucosa and airway after activation of TRPA1 stimulates the release of neurogenic pro-inflammatory neuropeptides SP and GCRP (KER3) that promote neurogenic inflammation, vasodilation, and fluid leakage. SP reacts with goblet cells and submucosal glands to increase mucus secretion and contractility of airway smooth muscles that results in bronchial constriction and increased airway resistance (O’Connor et al., 2004). CGRP reacts with the pulmonary vascular causing plasma extravasation, edema, and neutrophil infiltration (Andre et al., 2008; Trevisani et al., 2007). Clear time and concentration-dependent relationships between the activation of the receptor, Ca2+ ion flux and the release of neuropeptides are reported (Bessac and Jordt, 2010; 2008).

TRPA1 −/− mice but not TRPV1 −/− mice also have a greatly reduced leukocyte infiltration, reduced cytokine and mucus production, and abolished hyperactivity and hence impaired inflammation and hyper-reactivity. The lack of an irritant response and reduced neurogenic inflammation after exposure to known irritants in mice deficient in TRPA1 provides compelling evidence supporting the linkage for TRPA1 activation and neuropeptide release (Bautista et al., 2006; Caceres et al., 2009).

The Adverse Outcome:

Excitation of the trigeminal nerves causes the initiation of airway reflex responses, coughing, sneezing, and pain. The release of inflammatory neuropeptides induces bronchoconstriction, vasodilation, recruitment of immune cells, and an inflammatory response (Bautista et al., 2006, 2013). As the irritant reaches the lower airways, sensory nerve activation causes the following organ response or pulmonary responses: bronchial constriction spasms, increased mucus production, and further neurogenic inflammation. Increased eosinophils, T helper cells, and increases in the associated inflammatory cytokines (IL-2, Il-4, IL-10, Il-13) are observed (Caceres et al., 2009; Belvisi et al., 2011).

Trigeminal activation also results in a vagal response that slows the respiration rate (Alarie, 1981; Alarie et al., 1995). Exposure to irritants and the activation of TRPA1 coupled with its interaction with TRPV1 can eventually lead to the following organism responses or clinical manifestations: chronic cough, pain, airway inflammation, COPD, and asthmatic like conditions (Bessac and Jordt, 2008; Chen and Haclos, 2015; Baraldi et al., 2010.) The activation of these receptors causes hyper airway responsiveness and the induction of neurogenic inflammation (Bessac and Jordt, 2010; Belvisi et al., 2010). The activation of TRPA1 and TRPV1 induces the release of pro-inflammatory peptides such as NG, SP, and CGRP that mediate neurogenic inflammation observed as bronchoconstriction, and the vasodilation recruitment of immune cells (Bautista et al., 2006, 2013).

3.3. Weight of Evidence Assessment for the AOP

Evaluation of the AOP was based on the Bradford Hill criteria as described in the OECD AOP handbook (OECD, 2012, 2012a, 2016,2018) with the additional guidance provided in Becker et al. (2015) and Vinken et al. (2013). A box and linear flow diagram presented above was constructed to allow an easy determination of the sequence of biological events at the different levels of biological organization. The AOP was evaluated based on the weight of evidence (OECD, 2012a, 2016, 2018) for the following criteria: 1) dose-response relationships, 2) temporal relationship between the key events and adverse effect, 3) strength, consistency, and specificity between adverse effect and initiating event, and 4) biological plausibility, coherence, and consistency of the experimental evidence, 5) alternative mechanisms that logically present themselves and the extent to which they may distract from the postulated AOP, and 6) uncertainties, inconsistencies, and missing data.

3.3.1. Molecular initiating event (MIE)

The MIE is the binding of the chemical to the TRPA1 receptor resulting in an increase in intracellular Ca2+. The importance of the activation of TRPA1 receptor in the pulmonary responses to irritants is strongly supported by the results from studies with knockout mice, TRPA1−/− mice and TRPV−/− mice (Taylor-Clark et al., 2009; Bessac et al., 2009; Bessac et al., 2008; Caceres et al., 2009). For TRPA1 −/− mice after treatment with irritant chemicals, a diminished response is reported confirming the association of the initiating event, the activation of the TRPA1 receptor to the adverse effect. In contrast, after exposure to irritant chemicals, the irritation response was the same in TRPV1 (−/−) mice compared to wild-type mice consistent with the high specificity between TRPA1 activation and the adverse effect. Actual binding of the reactive chemicals to TRPA1 was confirmed by mass spectrum analysis. However, no dose-response was measured for the binding (Macpherson et al., 2007; Brone et al., 2008). These studies in knockout mice provide a strong strength, consistency, and specificity for the association of adverse effects and the initiating event.

Fibroblast expressing TRPA1 is a well-established in vitro assay measuring Ca2+ influx measured by Fura-2 fluorescent upon activation of TRPA1. Many investigators have used this assay to measure the potency of some irritant chemicals serving as the basis for much the information of TRPA1 and EC50 reported in the Guide to Pharmacology (Liu et al., 2017). A fibroblast cell line typically used is the HEK-293 due to its ease of expressing TRPA1 and utility for measuring Ca2+ influx. In a human transformed lung epithelial cell line, the A549 offers another cell line with the advantage of already expressing a functional TRPA1 (Buch et al., 2013). In vitro data on the activation of TRPA1 by known irritants as measured directly in cells expressing TRPA1 causes some uncertainty in the MIE since only a few irritants have been tested both in vitro and in vivo. In general, the potency of a few irritants, obtained from in vitro assays for the activation of TRPA1, is in agreement with the concentrations required to produce adverse effects in mice (Bessac et al., 2009; Brone et al., 2008; Bessac et al., 2008; McNamara et al., 2007; Schaper M., 1993). The correlation between the potency of most irritants that as measured by in vitro methods and the concentrations required for the irritation or the adverse effects in mice has not been fully investigated.

While the weight of evidence for activation of TRPA1 by chemicals in the mouse is high with a high confidence level, the exact mechanism and interactions with other receptors present in the trigeminal ganglia neurons are less clear. In general, however, there is a strong strength, consistency, and specificity for the association of adverse effects and the initiating event.

3.3.2. KE1 and KER1

TRPA1 is a member of the TRP family of Ca2+ ion channels and the binding of the chemicals to TRPA1 that results in an increase in intracellular is Ca2+ with a strong coherence and consistency exists with the experimental evidence (Bessac and Jordt 2008; 2010, Bautista et al., 2006; Brone et al., 2008). Studies with TRPA1 (−/−) cells and mice confirm that TRPA1 is essential for the increase in intracellular Ca2+ observed after treatment with irritant chemicals. Concordances between dose responses and temporal relationships were observed in vitro for increased intracellular Ca2+ and the trigeminal nerve excitation as measured by changes in electric potential (Bessac and Jordt, 2008; Besssac et al., 2008). The weight of evidence for both KE1 and KER1 is high, and the confidence level is high.

3.3.3. KE2 and KER2

The temporal sequence of events and the concentration dependency for intracellular Ca2+ agree with the electro-physiological changes observed in cells and isolated trigeminal neurons after irritant chemical treatment (Bessac and Jordt 2009; 2010, Bautista et al., 2006; Brone et al., 2008). The results from experiments with site-directed mutagenesis confirm the dependence of the electric potential differences and hence the nerve excitation by TRPA1 on Ca2+ ion (Doerner et a., 2007). Other studies with TRPA1 (−/−) mice confirm the presence of TRPA1 is essential for the trigeminal nerve excitation and irritation in mice (Bessac and Jordt 2009, 2010; Baustista et al., 2006; Brone et al., 2008; Achanta and Jordt, 2017) providing biological plausibility, coherence, and consistency with a high confidence level in KE2 and KER2.

3.3.4. KE3 and KER3

Neurogenic inflammation causes excitation of the trigeminal nerve-mediated sneezing, pain, coughing and vagal stimulation resulting in a decreased respiration rate occurs. In addition, the trigeminal nerve excitation stimulates the release of the pro-inflammatory neuropeptide, SP and CGRP that cause neurogenic inflammation (Trevisanti et al., 2007; Andre et al., 2008; Caceres et al., 2009). These biological responses to irritant exposure are greatly diminished in TRPA1 (−/−) mice confirming the essential role of TRPA1 in the adverse outcome, irritation (Bessac et al., 2008; Bautista et al., 20006; Taylor-Clark et al., 2010 Liu et al., 2013; McNamara et al., 2007). Other studies with TRPA1 (−/−) mice confirm the essential role of TRPA1 in airway inflammation and hyperreactivity and mast cell induction (Hox et al., 2013; Careres et al., 2009).

The temporal sequences of biochemical and physiological events agree with the adverse outcome of pulmonary irritation as observed at different times after exposure (Bessac and Jordt 2008; 2010, Bautista et al., 2006; Brone et al., 2008). The dose-response relationship between the activation of TRPA1 and neurogenic inflammation from in vitro, and in vivo experimental evidence is consistent with the hypothesis: the activation of the TRPA1 receptor is a key initiation event in pulmonary irritation (Bautista et al. 2006,2013, Bessac and Jordt, 2009; Belvisi et al., 2011). Biological plausibility is high and consistent with other studies on neurogenic inflammation (Mesegur et al., 2014; Xanthos and Sandkuhler, 2014) with strong coherence, and consistency of the experimental evidence to support the essential role, and empirical results indicating the weight of evidence and confidence in KE3 and KER3 is high.

3.3.5. Weight of evidence for AOP

The analysis of the overall weight of evidence for this AOP is strong and with a high level of confidence based on Bradford-Hill criteria for the analysis of the key events and the KERs connecting the key events to the subsequent key event sensory irritation. The biological plausibility based on the experimental evidence is strong for the KEs and KERs based on the knowledge obtained from numerous investigations. The concordance of dose responses and temporal relationships also strongly support the high confidence level. Evidence of essentiality for the AOP is based on diminished response to irritant chemicals observed with mice TRPA1 (−/−). All the key events and the adverse outcome were dependent on the MIE - activation of TRPA1.

4. Discussion

Compelling evidence as reported in the literature by several investigators (Bautista et al., 2013; Bessac and Jordt, 2010; Baraldi et al., 2010) support this sequence of key biological events in the AOP. The activation of the TRPA1 receptor is the critical event; it is the MIE that initiates this series of biological events causing respiratory irritation. The concentration dependence for the activation of TRPA1 for irritant chemical determines, in part, its potency for causing biological effects in vitro or in animal models.

More than 350 chemicals characterized as pulmonary irritants have been investigated with a mouse assay for sensory irritation based on measurement of changes in respiration (Alarie et al., 1981, 1995) with the data reported as RD50 values (Schaper, 1993). Excitation of the trigeminal nerves after activation of TRPA1 by an inhaled irritant causes a vagal mediated reduction in respiration rate. In TRPA1−/− mice, the reduction in respiration rate is attenuated after exposure to an inhalable irritant (Bessac and Jordt, 2010; Achanta and Jordt, 2017), providing evidence that respiration rate is a measure of TRPA1 activation. The RD50 values may be considered as an indirect measure of potency of an irritant to stimulate trigeminal nerve activation in mice, but the assay is comprised by the issues associated with animal experiments (pharmacokinetic issues, volatility of the chemicals, etc.).

For some irritant chemicals, including a few environmental chemicals, the activation of TRPA1 has been determined in HEK-293T fibroblasts and other cells that express TRPA1. Known irritant chemicals (65 are reported) bind to and activate TRPA1 with the data reported as pEC50 or the negative log Molar concentration causing a 50% of maximum response (Liu et al., 2017). Although many volatile chemicals are characterized as pulmonary irritants only a few of these environmental irritants have been tested using in vitro assays to directly measure the activation of TRPA1 and only a limited number of EC50 are reported (Bessac and Jordt, 2010; Bos et al., 2002, 2008; Lehmann et al., 2016).

An apparent correlation is reported between RD50 values and threshold limit values (TLVs) for some of these chemicals. Kuwabara et al. (2007), found relationships between RD50, and the lowest observed adverse effect (LOAELs), and acute exposure reference levels for 16-25 irritant chemicals. They concluded that RD50 data are useful for setting protective exposure levels for both workers and the general population. Sensory irritation has been proposed as a basis for setting occupational limits (Brüning et al., 2014; Nielsen and Wolkoff, 2017). Recently Nielsen and Wolkoff et al., 2017 evaluated the mouse bioassay (RD50 values) for setting exposure limits or guidelines for exposure to airborne irritants. They concluded this assay was the “only validated animal bioassay for prediction of sensory irritation in humans.” Exposure levels and RD50 data appear to be linked to the critical biochemical event (MIE) determined by the AOP.

Based on the understanding of the of respiratory irritation from the AOP and the data showing the mouse sensory assay indirectly measures TRPA1 activation we propose to use the in vitro assay with fibroblasts or other cells expressing TRPA1 to measure the direct activation of TRPA1 by suspected irritants. The assay could be used to screen chemicals for the activation of TRPA1 and to determine the concentration dependence or EC50 that could be used with other assays to help set exposure limits. A comparison of the RD50 values to the EC50 values is a suitable approach to test this hypothesis that the EC50 values and RD50 values obtained from exposure of mice to irritants correlate.

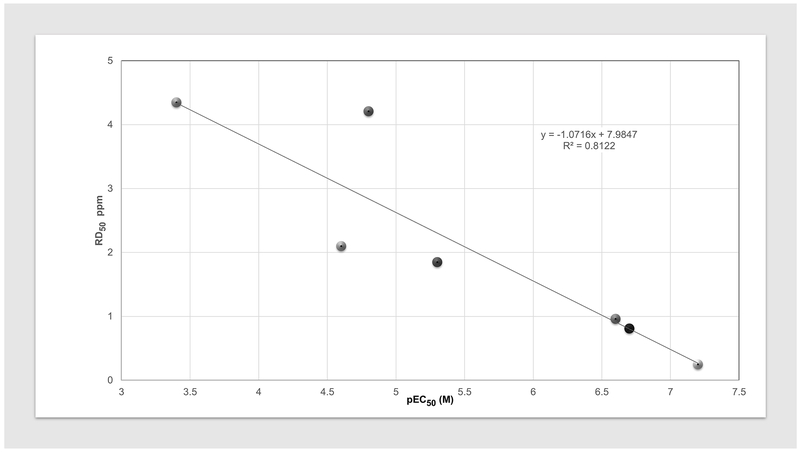

To identify EC50 values, the primary references identified from our extensive literature search and data reported in the Guide to Pharmacology database were examined (Liu et al., 2017). The pEC50 values were cross-referenced with the chemicals reported with the Schaper database (1993). Only 9 chemicals with both RD50 and pEC50 values were identified. A preliminary analysis with this published data was then done to determine the feasibility of this approach and is reported in Figure 3 and Table 1. The result shows a linear relationship exists between the in vivo RD50 and in vitro pEC50 values and is support for this proposal. The results suggest that pEC50 values for the activation of TRPA1 obtained from in vitro assay may be used to estimate in vivo RD50 or potentially replace the mouse sensory assay and hence be used in setting exposure levels of irritant chemicals. Additional support for this proposal is the good correlation that exists between the potency of tear gases determined by an in vitro assay using human TRPA1 expressed in cells and the concentrations causing 50% of an exposed human subject to detect the tear gas or to become incapacitated by the exposure (Brone et al., 2008). The development of a validated in vitro assay for TRPA1 activation can be used determine if an uncharacterized chemical is a potential chemical irritant and the results obtained may be useful as predictive tests and ultimately for setting human inhalation exposure limits.

Figure 3. The relationship between the RD50 values reported for mice exposure to irritants and the reported pEC50 for the in vitro activation of TRPA1.

The vertical linear axis is the RD50 values (ppm) as reported for mice. On the horizontal log axis is pEC50 (M) in for the activation of TRPA1 obtained by measuring the changes in Ca2+in fibroblasts expressing hTRPA1 as reported in Liu et al., 2017. All pEC50are from cells expressing human TRPA1 except for formaldehyde obtained with mouse TRPA1 and crotonaldehyde obtained with rat TRPA1. The chemicals and data are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Volatile organic chemicals (VOCs) used to compare in vivo RD50 values (ave. ± SD) to in vitro pEC50 values.

For the RD50 values, the exposure time was 3-10 minutes with mice. The pEC50 (negative logarithm to base 10 of the concentration) exposure time to produce the maximal response is typically seconds to minutes.

| Chemicala | CAS RN | RD50b,c (ppm) | pEC50d (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde | 50-00-0 | 4.35±0.94 (n=4) | 3.4 |

| Methyl isocyanate (MIC) | 624-83-9 | 2.1±1.13 (n=2) | 4.6 |

| Crotonaldehyde | 123-73-9 | 4.21±0.95 (n=2) | 4.8 |

| Acrolein | 107-02-8 | 1.85±0.69 (n=7) | 5.3 |

| 1-Chloroacetophenone (CN) | 532-27-4 | 0.96 | 6.6. |

| 2-Chlorobenzyl-malononitrile (CS) | 2698-41-1 | 0.81±0.54 (n=2) | 6.7 |

| Dibenz[b,f,][1,4] -oxazepine (CR) | 257-07-8 | 0.25 | 7.2 |

Chemicals with both reported RD50 and pEC50 values were identified and had 2015 TLVs (threshold limit value) developed based solely on respiratory irritation by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). The TLV is a level to which a worker can be exposed day after day for a working lifetime without adverse effects. Chemicals with TLVs based upon pulmonary sensitization or edema were excluded due to the complexity of multiple mechanisms.

Alarie, 2015,

Confirming the in vitro activation of TRPA1 by other established irritants would enhance the scope of this AOP. If some of these irritants were found not to be activators of TRP A1 receptors, then fibroblast expressing TRPV1 or ASIC may be appropriately used. TRPA1 and TRPV1 co-localize in the nerve ending (Bessac and Jordt, 2008) and some data suggest possible interactions between these two receptors. For example, the diallyl sulfides present in garlic activate both the TRPV1 and TRPA1, but activation of TRPA1 was observed at lower concentrations (Koizumi et al., 2009). Lehmann et al. (2016, 2017) have also provided evidence with 2-ethyl hexanol activation of both TRPA1 and TRPV1 in vitro and suggested the use of several in vitro assays is necessary to investigate and fully characterize irritants. Fibroblasts or oocytes can be constructed to co-express both TRPA1 and TRPV1 that can be used to determine if any interaction alters the EC50 for activation. Primary cultures of trigeminal neurons and calcium imaging have also been used to investigate the activation by a series of VOCs irritants (Inoune and Bryant, 2005; Lehmann et al., 2016, 2017). The activation of the neurons did not always agree with its RD50 value and suggest additional mechanisms may also be responsible for the irritation observed in the mice assay. In addition, using the in vitro assay combined with other assays to measure the biochemical and cellular processes described in the key events of this AOP (the increase in intracellular Ca2+, trigeminal nerve excitation measured by changes in cellular membrane potential or calcium imaging, and measurements of the release of neurogenic pro-inflammatory neuropeptides or cytokines) as a multitiered approach could increase the predictive accuracy and requires further research.

In summary, the development of an AOP for respiratory sensory irritation provided evidence that the activation of TRPA1 is the MIE and subsequently causes an increase in intracellular Ca2+, trigeminal nerve excitation and neurogenic inflammation to cause the adverse outcome of pulmonary irritation. This understanding leads to a proposed approach to use a cellular-based in vitro assay to directly measure the activation of TRPA1 to determine if a suspected chemical is an irritant and then to determine its potency. With further development and validation this in vitro assay to measure the activation of TRPA1 may be a suitable replacement for the mouse sensory RD50 assay that can be used for setting inhalation exposure limits.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information: The NIEHS Intramural Research Program supported, in part, this study.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

5. References:

- Achanta S and Jordt SE (2017). TRPA1: Acrolein meets its target. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 324: 45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarie Y (1966). Irritating Properties of Airborne Materials to the Upper Respiratory Tract, Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal, 13(4), 433–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarie Y (1981). Bioassay for evaluating the potency of airborne sensory irritants and predicting acceptable levels of exposure in man, Food Cosmet Toxicol, 19(5), 623–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarie Y, Nielsen GD, Andonian-Haftvan J, and Abraham MH (1995). Physicochemical properties of nonreactive volatile organic chemicals to estimate RD50: alternatives to animal studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 134(1): 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DA, Gentry C, Moss S and Bevan S (2008). Transient receptor potential A1 is a sensory receptor for multiple products of oxidative stress. J Neurosci 28(10): 2485–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre E, Campi B, Materazzi S, Trevisani M, et al. (2008). Cigarette smoke-induced neurogenic inflammation is mediated by alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes and the TRPA1 receptor in rodents. J Clin Invest 118(7): 2574–2582. doi: 10.1172/JCI34886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi PG, Preti D, Materazzi S, and Geppetti P(2010). Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) channel as emerging target for novel analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents. J Med Chem, 53(14), 5085–107. doi: 10.1021/jm100062h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Jordt S-E, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, et al. (2006). TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agent. Cell 124(6), 1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Pellegrino M, and Tsunozaki M (2013). TRPA1: A gatekeeper for inflammation, Annu Rev Physiol, 75, 181–200. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker RA, Ankley GT, Edwards SW, Kennedy SW, et al. (2015). Increasing Scientific Confidence in Adverse Outcome Pathways: Application of Tailored Bradford-Hill Considerations for Evaluating Weight of Evidence. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 72, 514–37. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi MG, Dubuis E, and Birrell MA (2011). Transient receptor potential A1 channels: insights into cough and airway inflammatory disease. Chest, 140, 1040–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessac BF and Jordt SE (2008). Breathtaking TRP channels: TRPA1 and TRPV1 in airway chemosensation and reflex control. Physiology (Bethesda), 23, 360–70. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00026.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessac BF, Sivula M, von Hehn CA, Escalera J, et al. (2008). TRPA1 is a major oxidant sensor in murine airway sensory neurons. J Clin Invest, 118(5), 1899–1910. doi: 10.1172/JCI34192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessac BF, Sivula M, von Hehn CA, Caceres AI, et al. (2009). Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 antagonists block the noxious effects of toxic industrial isocyanates and tear gases. FASEB J, 23, 1102–1114. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessac BF and Jordt SE (2010). Sensory detection and responses to toxic gases: mechanisms, health effects, and countermeasures, Proc Am Thorac Soc, 7 (4), 269–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos PM, Zwart A, Reuzel PG and Bragt PC (1991). Evaluation of the sensory irritation test for the assessment of occupational health risk. Crit Rev Toxicol 21(6): 423–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos PM, Busschers M, & Arts JH (2002). Evaluation of the sensory irritation test (Alarie test) for the assessment of respiratory tract irritation. J Occup Environ Med, 44(10), 968–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brône B, Peeters PJ, Marrannes R, Mercken M, et al. (2008). Tear gasses CN, CR, and CS are potent activators of the human TRPA1 receptor. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 231(2), 150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SM, Weiss MA, and Bernstein IL (1985). Reactive airways dysfunction syndrome (rads). Persistent asthma syndrome after high level irritant exposures, Chest, 88(3), 376–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüning T, Bartsch R, Bolt H, Desel H, et al. (2014). Sensory irritation as a basis for setting occupational exposure limits. Arch Toxicol 88(10), 1855–1879. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1346-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch TR, Schafer EA, Demmel MT, Boekhoff I, et al. (2013). Functional expression of the transient receptor potential channel TRPA1, a sensor for toxic lung inhalants, in pulmonary epithelial cells. Chem Biol Interact 206(3): 462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres AI, Brackmann M, Elia MD, Bessac BF, et al. (2009). A sensory neuronal ion channel essential for airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(22), 9099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900591106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J and Hackos DH (2015). TRPA1 as a drug target--promise and challenges. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol, 388(4), 451–63. doi: 10.1007/s00210-015-1088-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka A, Uzzell V, Dubin AE, Mathur J, et al. (2009). TRPV1 is activated by both acidic and basic pH. J Neurosci 29(1), 153–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4901-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner JF, Gisselmann G, Hatt H, & Wetzel CH (2007). Transient receptor potential channel A1 is directly gated by calcium ions. J Biol Chem, 282(18), 13180–13189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607849200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita F, Uchida K, Moriyama T, Shima A, et al. (2008). Intracellular alkalization causes pain sensation through activation of TRPA1 in mice. J Clin Invest 118(12), 4049–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI35957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox V, Vanoirbeek JA, Alpizar YA, Voedisch S, et al. (2013). Crucial role of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 and mast cells in induction of nonallergic airway hyperreactivity in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187(5): 486–493. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1358OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T and Bryant BP (2005). Multiple types of sensory neurons respond to irritating volatile organic compounds (VOCs): calcium fluorimetry of trigeminal ganglion neurons, Pain, 117(1–2), 193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordt SE, Bautista DM, Chuang HH, McKemy DD, et al. (2004). Mustard oils and cannabinoids excite sensory nerve fibres through the TRP channel ANKTM1. Nature, 427(6971), 260–265. doi: 10.1038/nature02282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kichko TI, Kobal G, and Reeh PW (2015). Cigarette smoke has sensory effects through nicotinic and TRPA1 but not TRPV1 receptors on the isolated mouse trachea and larynx. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 309(8), L812–820. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00164.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocmalova M, Joskova M, Franova S, Banovcin P, et al. (2016). Airway Defense Control Mediated via Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. Adv Exp Med Biol 921, 71–80. doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi K, Iwasaki Y, Narukawa M, Iitsuka Y, et al. (2009). Diallyl sulfides in garlic activate both TRPA1 and TRPV1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 382(3), 545–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara Y, Alexeeff GV, Broadwin R, and Salmon AG (2007). Evaluation and application of the RD50 for determining acceptable exposure levels of airborne sensory irritants for the public. Environ Health Perspect 115(11), 1609–16. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanosa MJ, Willis DN, Jordt S, and Morris JB (2010). Role of metabolic activation and the TRPA1 receptor in the sensory irritation response to styrene and naphthalene. Toxicol Sci 115(2), 589–95. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann R, Schobel N, Hatt H, and van Thriel C (2016). The involvement of TRP channels in sensory irritation: a mechanistic approach toward a better understanding of the biological effects of local irritants. Arch Toxicol 90(6), 1399–413. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1703-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann R, Hatt H, & van Thriel C (2017). Alternative in vitro assays to assess the potency of sensory irritants-Is one TRP channel enough? Neurotoxicology, 60, 178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Escalera J, Balakrishna S, Fan L, et al. (2013). TRPA1 controls inflammation and pruritogen responses in allergic contact dermatitis. FASEB J 27(9), 3549–63. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-229948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Fan L, Nilius B, Owsianik G, et al. (2017). Transient Receptor Potential channels: TRPA1. Last modified on 15/03/2017 Accessed on 04/03/2019 IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology, database: http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=485.

- Macpherson LJ, Dubin AE, Evans MJ, Marr F, et al. (2007). Noxious compounds activate TRPA1 ion channels through covalent modification of cysteines. Nature 445(7127), 541–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara CR, Mandel-Brehm J, Bautista DM, Siemens J, et al. (2007). TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104(33), 13525–13530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705924104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meseguer V, Alpizar YA, Luis E, Tajada S, et al. (2014). TRPA1 channels mediate acute neurogenic inflammation and pain produced by bacterial endotoxins. Nat Commun. 5:3125. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naono-Nakayama R, Sunakawa N, Ikeda T, and Nishimori T (2010). Differential effects of substance P or hemokinin-1 on transient receptor potential channels, TRPV1, TRPA1 and TRPM8, in the rat. Neuropeptides 44(1), 57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen GD and Wolkoff P (2017). Evaluation of airborne sensory irritants for setting exposure limits or guidelines: A systematic approach. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 90: 308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TM, O’Connell J, O’Brien DI, Goode T, et al. (2004). The role of substance P in inflammatory disease. J Cell Physiol 201(2), 167–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2012a). The Adverse Outcome Pathway for Skin Sensitization initiated by covalent binding to proteins Part 1: Scientific Evidence. Retrieved from: http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=env/jm/mono(2012)10/part1anddoclanguage=en

- OECD. (2012b). Proposal for a template and guidance on developing and assessing the completeness of adverse outcome pathways. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/chemicalsafety/testing/49963554.pdf

- OECD (2016), Users Handbook supplement to the Guidance Document for developing and assessing Adverse Outcome Pathways, OECD Series on Adverse Outcome Pathways,No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris: 10.1787/5jlv1m9d1g32-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2018), Users Handbook supplement to the Guidance Document for developing and assessing Adverse Outcome Pathways, OECD Series on Adverse Outcome Pathways, No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris: 10.1787/5jlv1m9d1g32-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen CE, Armache JP, Gao Y, Cheng Y, and Julius D (2015). Structure of the TRPA1 ion channel suggests regulatory mechanisms. Nature 525 (7570), 552–552 (Corrigendum). doi: 10.1038/nature14367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterlin Z, Chesler A, and Firestein S (2007). A painful trp can be a bonding experience. Neuron 53(5), 635–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell TR and Tarran R (2015). “Will chronic e-cigarette use cause lung disease?” Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309(12): L1398–1409. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00272.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell FA, King R, Smillie SJ, Kodji X, et al. (2014). Calcitonin gene-related peptide: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 94 (4), 1099–142. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper M (1993). Development of a database for sensory irritants and its use in establishing occupational exposure limits. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 54 (9), 488–544. doi: 10.1080/15298669391355017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symanowicz PT, Gianutsos G, and Morris JB (2004). Lack of role for the vanilloid receptor in response to several inspired irritant air pollutants in the C57Bl/6J mouse. Neurosci Lett 362(2), 150–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Clark TE, Kiros F, Carr MJ, and McAlexander MA (2009). Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 mediates toluene diisocyanate-evoked respiratory irritation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 40 (6), 756–762. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0292OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Clark TE, and Undem BJ (2010). Ozone activates airway nerves via the selective stimulation of TRPA1 ion channels. J Physiol, 588(Pt 3), 423–433. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisani M, Siemens J, Materazzi S, Bautista DM, et al. (2007). 4-Hydroxynonenal, an endogenous aldehyde, causes pain and neurogenic inflammation through activation of the irritant receptor TRPA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104(33), 13519–13524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705923104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinken M, Landesmann B, Goumenou M, Vinken S, et al. (2013). Development of an adverse outcome pathway from drug-mediated bile salt export pump inhibition to cholestatic liver injury. Toxicol Sci, 136(1), 97–106. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve DL, Crump D, Garcia-Reyero N, Hecker M, et al. (2014). Adverse outcome pathway (AOP) development I: strategies and principles, Toxicol Sci. 2(2):312–20. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthos DN, & Sandkuhler J (2014). Neurogenic neuroinflammation: inflammatory CNS reactions in response to neuronal activity. Nat Rev Neurosci, 15(1), 43–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn3617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]