Kinetochores monitor their attachment to spindle microtubules to control spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) signaling and cell cycle progression. Kuhn and Dumont show that individual mammalian kinetochores monitor the number of attached microtubules as a single unit in a sensitive and switch-like manner.

Abstract

The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) prevents anaphase until all kinetochores attach to the spindle. Each mammalian kinetochore binds many microtubules, but how many attached microtubules are required to turn off the checkpoint, and how the kinetochore monitors microtubule numbers, are not known and are central to understanding SAC mechanisms and function. To address these questions, here we systematically tune and fix the fraction of Hec1 molecules capable of microtubule binding. We show that Hec1 molecules independently bind microtubules within single kinetochores, but that the kinetochore does not independently process attachment information from different molecules. Few attached microtubules (20% occupancy) can trigger complete Mad1 loss, and Mad1 loss is slower in this case. Finally, we show using laser ablation that individual kinetochores detect changes in microtubule binding, not in spindle forces that accompany attachment. Thus, the mammalian kinetochore responds specifically to the binding of each microtubule and counts microtubules as a single unit in a sensitive and switch-like manner. This may allow kinetochores to rapidly react to early attachments and maintain a robust SAC response despite dynamic microtubule numbers.

Introduction

The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) protects genomic integrity by preventing anaphase until all kinetochores stably attach to the spindle (Rieder et al., 1995). Unattached kinetochores, and certain improperly attached ones, recruit Mad1 and Mad2, which generate an anaphase-inhibitory signal (Chen et al., 1998; De Antoni et al., 2005; Maldonado and Kapoor, 2011). The attachment of microtubule plus-ends (“end-on” attachments) is required for removing Mad1/Mad2 from kinetochores and consequently for cell cycle progression (Chen et al., 1998; Waters et al., 1998). Approximately 15–25 end-on microtubules bind mammalian kinetochores at metaphase (Wendell et al., 1993; McEwen et al., 1997), but how many microtubules are necessary for Mad1/2 loss, and how the kinetochore measures microtubule number, are not known. Yet, determining how the kinetochore detects and responds to varying microtubule numbers is critical to understanding the mechanisms and function of this signaling platform.

While we have a growing understanding of the individual molecules that give rise to the mammalian kinetochore, how they function together as an ensemble in vivo remains poorly understood. Kinetochores bind microtubule plus-ends through a dynamic subset of Hec1 molecules (of the Ndc80 complex; Cheeseman et al., 2006; DeLuca et al., 2006; Yoo et al., 2018), and in metazoans, kinetochore–microtubule binding triggers dynein to “strip away” Mad1/2 from kinetochores (Howell et al., 2001; Wojcik et al., 2001). In budding yeast kinetochores, which only bind one microtubule (Peterson and Ris, 1976), attachments may trigger and be detected by Mps1 kinase being displaced or blocked from its substrates (Aravamudhan et al., 2015). Loss of Mps1 activity prevents Mad1/2 kinetochore recruitment and is required for SAC satisfaction (Hewitt et al., 2010; Jelluma et al., 2010; Maciejowski et al., 2010; Santaguida et al., 2010; London and Biggins, 2014). In mammalian kinetochores, mechanisms to reduce Mps1 activity and thereby permit and potentially activate Mad1/2 loss (Jelluma et al., 2010; Hiruma et al., 2015; Ji et al., 2015) must operate over a disordered kinetochore “lawn” binding many microtubules (Zaytsev et al., 2014). The necessary and sufficient microtubule occupancy levels needed for Mad1/2 loss will drive kinetochore function: triggering anaphase with too few bound microtubules could increase mitotic errors (Dudka et al., 2018), and waiting for too many microtubules could cause mitotic delays, and thereby DNA damage and cell death (Uetake and Sluder, 2010; Orth et al., 2012). Previous work indicates that kinetochores bound to few microtubules can have low Mad2 levels at early prometaphase (Sikirzhytski et al., 2018), and that Mad1/2 can leave kinetochores with reduced (DeLuca et al., 2003) microtubule occupancy (50%; Kuhn and Dumont, 2017; Dudka et al., 2018; Etemad et al., 2019). Accessing SAC signaling at lower steady-state microtubule occupancies is challenging without perturbing proteins involved in the SAC (Martin-Lluesma et al., 2002; DeLuca et al., 2003), and capturing attachment intermediates is difficult since microtubules rapidly attach during kinetochore-fiber (k-fiber) formation (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017; Sikirzhytski et al., 2018; David et al., 2019). To understand how the kinetochore counts microtubules, we need to externally tune and fix the normally dynamic number of attached microtubules. Finally, understanding how microtubule occupancy regulates SAC signaling requires defining what element of microtubule attachment is detected by the SAC at individual kinetochores. Both kinetochore–microtubule binding (Rieder et al., 1995; Waters et al., 1998; O’Connell et al., 2008; Etemad et al., 2015; Tauchman et al., 2015) and attachment-generated tension (McIntosh, 1991; Maresca and Salmon, 2009; Uchida et al., 2009; Janssen et al., 2018) have been proposed to be detected by the SAC, and decoupling their closely linked contributions (Akiyoshi et al., 2010; Sarangapani and Asbury, 2014) is needed to identify how kinetochores count microtubules.

Here, we develop a “mixed kinetochore” system to tune and fix the fraction of Hec1 kinetochore molecules within the kinetochore lawn that are capable of microtubule binding. We demonstrate that the number of bound microtubules scales linearly with the number of functional binders, indicating a lack of binding cooperativity between the hundreds of Hec1 molecules (Johnston et al., 2010; Suzuki et al., 2015) within the native kinetochore. We then show that kinetochores with as low as 20% of metaphase microtubule occupancy can trigger complete Mad1 loss, indicating that the kinetochore makes its decision as a single unit, not through independent subunits. However, Mad1 loss under low occupancy occurs more slowly, which may give early attachments time to mature before complete Mad1 loss. Finally, by acutely removing spindle forces, we show that individual kinetochores detect changes in microtubule binding, not in pulling forces that occur with attachment. Together, our data demonstrate that microtubule binding itself activates Mad1 loss, and that it does so in an all-or-none decision with a temporally tuned response. These findings provide a quantitative framework for understanding SAC signaling: they constrain mechanisms for how the kinetochore monitors and responds to microtubule occupancy and suggest how it can rapidly react to new attachments and yet maintain a robust SAC response despite dynamic microtubule occupancy.

Results

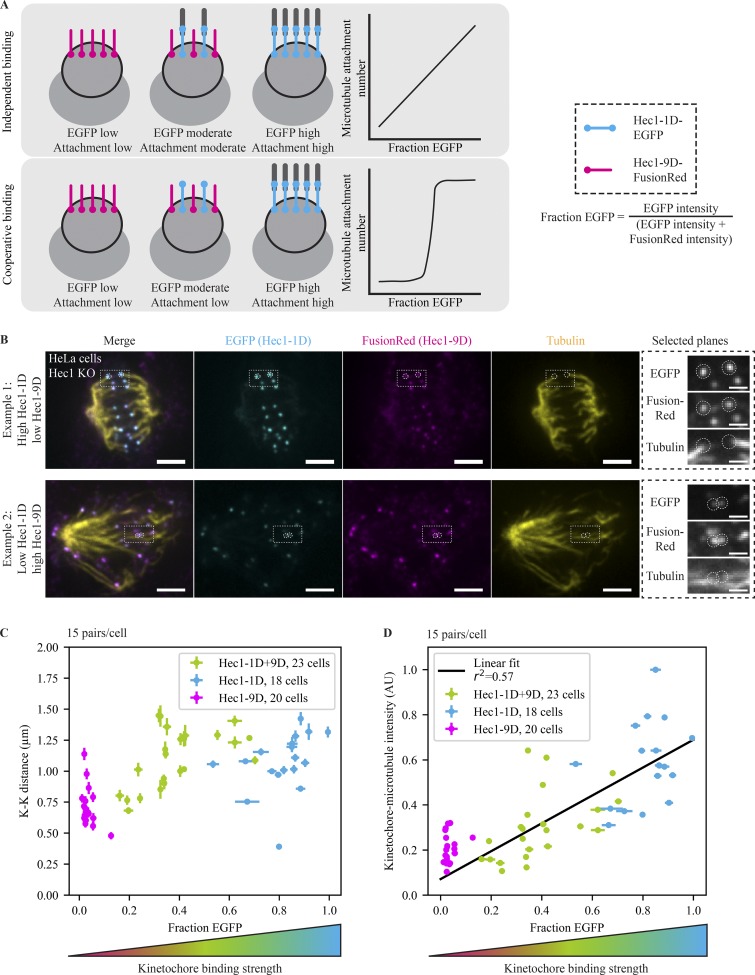

To vary the number of steady-state microtubule attachments at kinetochores, we designed a system to vary, fix, and quantify the fraction of Hec1 molecules at kinetochores capable of strong microtubule binding (Fig. 1 A). To this end, we depleted endogenous Hec1 in HeLa cells using an inducible CRISPR-based system (Fig. S1, A–C; McKinley and Cheeseman, 2017) and coexpressed weak-affinity Hec1-9D-FusionRed and metaphase-like affinity Hec1-1D8A-EGFP (Hec1-1D; Fig. 1 A; Zaytsev et al., 2014). In contrast to changing Hec1–microtubule interactions over the entire lawn, this mixed kinetochore system preserves a fraction of Hec1–microtubule interactions with native affinity (Zaytsev et al., 2014) and native SAC signaling (Hiruma et al., 2015; Ji et al., 2015). In this mixed kinetochore assay, the fraction of EGFP (Hec1-1D) versus FusionRed (Hec1-9D) at each kinetochore sets microtubule affinity (Fig. 1 A). Notably, EGFP and FusionRed intensities varied far more between cells than within a given cell (Fig. S1 D; F = 175, P = 10−220 for EGFP; F = 59, P = 10−139 for Fusion Red, one-way ANOVA), independent of any bias in identifying kinetochores (Fig. S1 E; F = 170, P = 10−92 for EGFP; F = 50, P = 10−35 for FusionRed, one-way ANOVA), suggesting that variability in protein expression more than kinetochore assembly gives rise to the spread of kinetochore compositions we observe.

Figure 1.

Kinetochore-microtubule occupancy scales linearly with the number of functional Hec1 subunits. (A) Schematic depicting experimental design and expected outcomes. After deleting endogenous Hec1, strong (Hec1-1D, blue) and weak (Hec1-9D, pink) microtubule-binding mutants are expressed. Cells randomly receive different fractions of functional binders and therefore have different microtubule occupancies. Depending on whether Hec1 subunits bind microtubules cooperatively or independently, microtubule attachment may change rapidly or gradually. Hec1-9D kinetochores are depicted without attached microtubules for simplicity but may have low-affinity attachments. (B) Immunofluorescence imaging (maximum-intensity projection) of microtubule attachments (tubulin), Hec1-1D intensity (anti-EGFP), and Hec1-9D intensity (anti-mKate, binds to FusionRed) in Hec1 knockout cells expressing Hec1-1D-EGFP and Hec1-9D-FusionRed. Cells were treated with 5 µM MG132 to accumulate them at a metaphase spindle steady state. The two highlighted examples were taken from the same coverslip, where the top has a high Hec1-1D to -9D ratio and the bottom a low ratio. Scale bars = 3 µm (large) and 1 µm (zoom). (C and D) Mean of cellular EGFP fraction for each cell versus mean cellular K-K distance (C) and mean cellular kinetochore microtubule intensity (D) from Hec1 knockout cells in B with mixed kinetochores (n = 345 pairs, 690 kinetochores, 23 cells; green) and cells with control Hec1-1D alone (n = 270, 540, 18; blue) and Hec1-9D alone coverslips (n = 300, 600, 20; pink; D). The relationship between microtubule attachment and amount of strong binders fits a linear relationship (r2 = 0.57) better than an exponential one (r2 = 0.51). Error bars = SEM. All data displayed were acquired at the same time for all conditions and with the data in Fig. 2.

We first used this mixed kinetochore assay to map how microtubule occupancy scales with the number of binding-competent Hec1 molecules. If microtubule binding were highly cooperative, creating broadly tunable microtubule occupancy steady states would be difficult (Fig. 1 A). To map the relationship between functional Hec1 numbers and microtubule occupancy, we prepared mixed kinetochore cells as above and added the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 1 h to increase the fraction of kinetochores that reach steady-state occupancies. We then fixed and stained cells for microtubules, EGFP (Hec1-1D), and FusionRed (Hec1-9D). As expected, cells highly expressing Hec1-1D (and Hec1-1D–alone cells) formed robust microtubule attachments, and cells highly expressing Hec1-9D (and Hec1-9D–alone cells) did not (Figs. 1 B and S1 F). These kinetochores were fully able to recruit and retain proteins critical for microtubule attachment and checkpoint function (Fig. S1 G). As the fraction of Hec1-1D increased, attachments produced more force, as measured by the interkinetochore (K-K) distance (Fig. 1 C, Spearman’s rho = 0.35, P = 10−21), and the intensity of end-on microtubule attachments (Fig. S1 H) rose in a smooth, graded way well fitted by a linear relationship (Fig. 1 D, r2 = 0.57, P = 10−8), mixed kinetochores having microtubule occupancies between those of Hec1-9D–alone and Hec1-1D–alone cells. This suggests that Hec1 subunits bind microtubules independently of each other, with weak or no cooperativity in the in vivo native kinetochore, similar to some (but not all [Alushin et al., 2010]) in vitro measurements despite different binding geometries and molecular contexts (Cheeseman et al., 2006; Ciferri et al., 2008; Zaytsev et al., 2015; Volkov et al., 2018). Thus, this mixed kinetochore system can tune and fix kinetochore–microtubule numbers in a graded and quantifiable way.

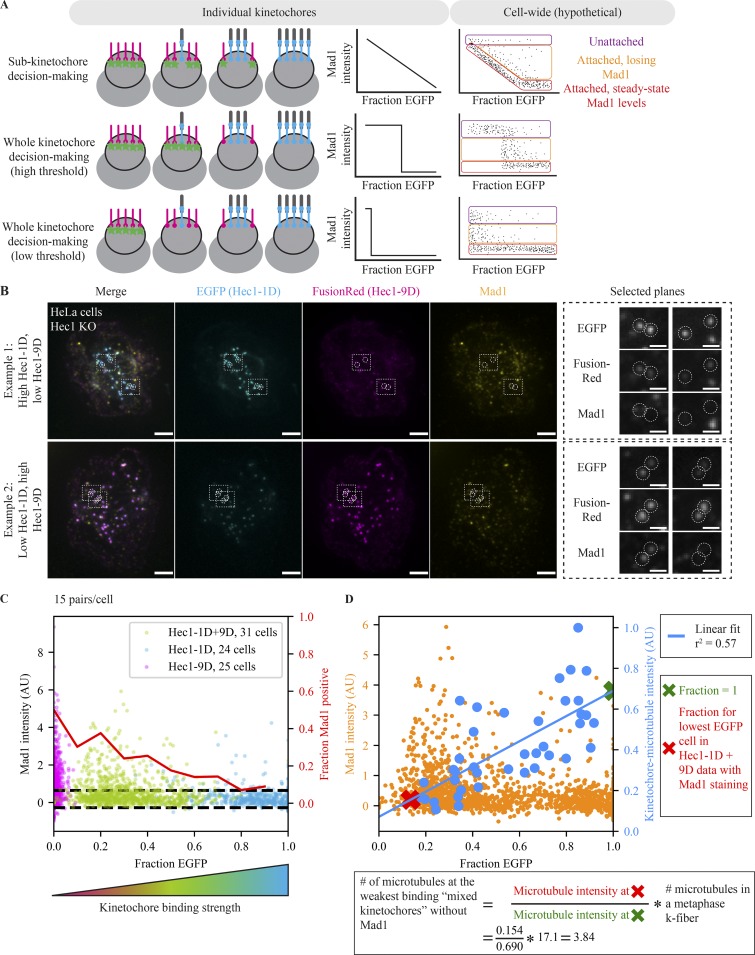

We then used this mixed kinetochore system to map how kinetochores with different fractions of strong microtubule-binding Hec1s coordinate a SAC response, and how many microtubules attachments are needed for complete Mad1 loss (Fig. 2 A). If Hec1 molecules in the outer kinetochore lawn (Zaytsev et al., 2014) function as independent subunits for SAC processing, we expect Mad1 levels to gradually go down as more Hec1s bind microtubules (Fig. 2 A, top). Alternatively, if the kinetochore integrates information from all Hec1 binding sites as a single unit, Mad1 levels could suddenly drop to zero (undetectable) as more Hec1s bind microtubules and a threshold occupancy level is crossed (Fig. 2 A, middle and bottom). To distinguish between these scenarios and others, we treated Hec1-depleted cells expressing Hec1-9D or Hec-1D or varying mixtures of both with MG132 for 1 h and then fixed and stained cells for Mad1, GFP (Hec1-1D), and FusionRed (Hec1-9D; Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

The number of attached microtubules regulates steady-state Mad1 localization in a switch-like, highly sensitive manner. (A) Schematic depicting models for kinetochore signal integration and expected hypothetical outcomes. The kinetochore processes microtubule attachments either as many individual units (top) or as one single unit (switch like) with a high (middle) or low (bottom) threshold. On the cellular scale, we expect three kinetochore populations: completely unattached (purple), attached and in the process of losing Mad1 (orange), and at attached steady-state Mad1 levels (red). The relative number of kinetochores in each population is arbitrary. (B) Immunofluorescence imaging (maximum-intensity projection) of SAC activation (Mad1), Hec1-1D intensity (anti-EGFP), and Hec1-9D intensity (anti-mKate, binds to FusionRed) in Hec1 knockout cells expressing both Hec1-1D-EGFP and Hec1-9D-FusionRed. Cells were treated with 5 µM MG132 to accumulate them at a metaphase spindle steady state. The two examples are cells on the same coverslip, where the top has a high Hec1-1D to -9D ratio and the bottom a low ratio. Kinetochores in both conditions are capable of recruiting (left zoom) and losing (right zoom) Mad1. Scale bars = 3 µm (large) and 1 µm (zoom). (C) Fraction EGFP versus Mad1 intensity from mixed kinetochore cells in B (n = 930 kinetochores, 31 cells; green) and cells with control Hec1-1D (n = 720, 24; blue) and Hec1-9D (n = 750, 25; pink) alone. Red line indicates the fraction of kinetochores with Mad1 intensities 1 SD (dashed black lines) greater than average Mad1 intensity on Hec1-1D kinetochores. (D) Fraction EGFP versus Mad1 intensity (B and C) or average end-on attached microtubule numbers (Fig. 1, B–D) for Hec1-1D alone and Hec1-1D + -9D conditions. Blue line indicates linear fit for cellular average fraction EGFP versus cellular average kinetochore–microtubule intensity (r2 = 0.57, P = 10−8). Xs indicate the points along the fit used for the calculation of attached microtubule number (red, average fraction EGFP for the lowest fraction EGFP cell in mixed kinetochores in which some kinetochores are Mad1-negative; green, fraction EGFP of 1). Calculation of the number of microtubules at the weakest binding mixed kinetochores without Mad1 uses the average number of microtubules in a metaphase k-fiber from Wendell et al. (1993) (see Materials and methods). All data displayed was acquired at the same time for all conditions and with the data in Fig. 1. Alternative estimation methods lead to similar estimates (Fig. S2 B).

In the mixed kinetochore system, cells with high Hec1-9D had many more Mad1-positive kinetochores than cells with high Hec1-1D (Fig. 2, B and C), and the Mad1 intensity was brighter on average at weak binding kinetochores (fraction EGFP = 0.1–0.3) than strong binding ones (fraction EGFP = 0.6–0.9; P = 10−15). While Hec1-9D cells have no or delayed anaphase entry (Sundin et al., 2011), individual kinetochores can lose Mad1; indeed, ∼60% of kinetochores in high–Hec1-9D cells had no detectable Mad1 (Fig. 2 C). Staining for Mad1 and microtubules together (Fig. S2, A–D) revealed mixed kinetochores with low microtubule levels and undetectable Mad1 (Fig. S2 A), and kinetochores with low Hec1-1D expression and low microtubule levels reached Mad1 levels equivalent to WT cells arrested at metaphase (Fig. S2, B and C). Mixed kinetochores had an unperturbed ability to bind microtubules (at high Hec1-1D expression, P = 0.106; Fig. S2 D) and to recruit Mad1 (in nocodazole; Fig. S2, E and F). The distribution of kinetochore Mad1 intensities we observed in our assay (Fig. 2 C), which is not dependent on kinetochore selection bias (Fig. S2 G), is consistent with a single-unit, switch-like decision to lose Mad1 in response to microtubule attachment (Fig. 2 A, bottom). While some kinetochores remain unattached (Fig. 2 A, purple) or in the process of Mad1 loss (Fig. 2 A, orange), Mad1 reaches undetectable levels even at the lowest microtubule occupancy levels we can reach with mixed kinetochores (Fig. 2 C). In contrast, in an independent subunit model, we would expect the minimum Mad1 intensity at low occupancy to be high and then to decrease gradually as occupancy increases (Fig. 2 A, top). Thus, the decision to trigger Mad1 loss is made at the level of the whole kinetochore by a single unit, rather than at the level of kinetochore subunits (Fig. 2 A).

To estimate how many microtubules were attached at the lowest Hec1-1D levels sampled in the mixed kinetochores, we used the relationship between microtubule attachments we obtained in parallel (Figs. 1 and 2 D). Assuming that an EGFP fraction of 1 corresponds to Hec1-1D–only expression, and thus a WT affinity kinetochore (Zaytsev et al., 2014), we estimate that the attached microtubule number in the lowest Hec1-1D fraction reached in mixed cells is ∼23% of normal metaphase levels, corresponding to ∼4 of 17 microtubules (Fig. 2 D; Wendell et al., 1993). Using different assumptions in this estimation yields values of 2–4 microtubules (Fig. S2 H), significantly lower than previous estimates (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017; Dudka et al., 2018; Etemad et al., 2019), likely because we can now generate lower steady-state microtubule occupancy levels. The sensitivity of the checkpoint to microtubule attachment (fully turning off at a small fraction of a full metaphase complement) indicates that the kinetochore must not only respond as single unit, but also amplify small changes in microtubule occupancy across its entire structure. Thus, while Hec1 molecules independently bind microtubules (Fig. 1), they do not independently process microtubule attachment cues to regulate the SAC (Fig. 2).

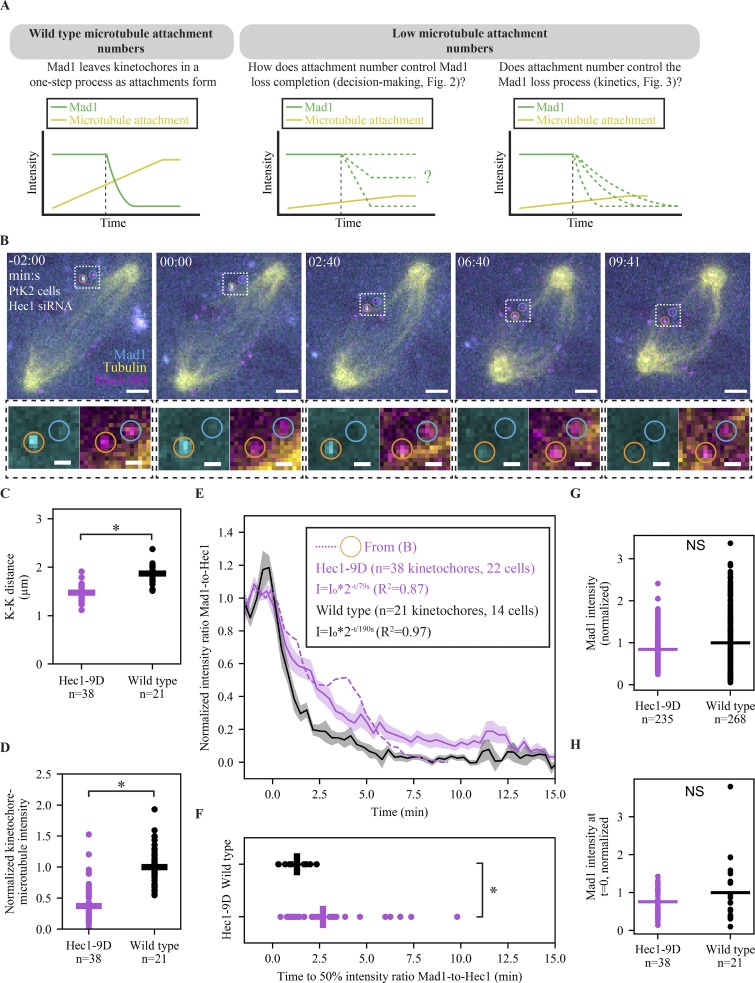

Previous work indicates that once the kinetochore triggers the start of Mad1 loss, Mad1 leaves with stereotyped single exponential kinetics (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017). These kinetics are likely governed by one rate-limiting step, but the nature of this step and whether it is regulated are not known. Above, we show that kinetochores with lower microtubule occupancy can trigger complete Mad1 loss, and here we use live imaging to ask whether microtubule occupancy levels regulate the rate of Mad1 loss (Fig. 3 A). Determining whether microtubule occupancy regulates only the Mad1 loss trigger or also its rate can have implications for both the SAC’s molecular underpinnings and cellular role. To test how lowering steady-state microtubule occupancy affects Mad1 loss rates, we expressed Hec1-9D-FusionRed in PtK2 cells where endogenous Hec1 was depleted by RNAi (Guimaraes et al., 2008; Long et al., 2017) and monitored EYFP-Mad1 loss dynamics during attachment formation (visualized using SiR-Tubulin; Lukinavičius et al., 2014; Fig. 3 B). A decrease in K-K distance versus that in WT cells (Fig. 3 C; 1.49 ± 0.03 vs. 1.87 ± 0.04 µm, P = 10−8) and in kinetochore–microtubule attachment intensity (Fig. 3 D; P = 10−15) confirms the expected reduction in kinetochore–microtubule affinity. We note that this decrease in affinity is likely smaller here compared with Hec1-9D-FusionRed cells in Figs. 1 and 2 because it relies on Hec1 RNAi rather than gene knockout. While the Mad1 loss rate does not increase with higher microtubule occupancy (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017), we find that it decreases with decreased occupancy (Fig. 3, E and F, half-life [t1/2] = 190 s in Hec1-9D vs. 62 s in WT; Video 1), and yet decreased-occupancy kinetochores are still capable of losing Mad1 to undetectable levels (Fig. 3, B and E). This difference in kinetics is not due to differences in Mad1 levels, as we do not detect differences in Mad1 intensity at individual kinetochores between Hec1-9D and WT cells in nocodazole (Fig. 3 G; P = 0.126) or immediately before Mad1 loss (Fig. 3 H; P = 0.298). Together, our data indicate that low microtubule occupancy regulates the rate at which Mad1 is lost from kinetochores and the SAC is thereby satisfied (Fig. 3), but not the decision to satisfy the SAC (Fig. 2).

Figure 3.

Lowering microtubule occupancy at a kinetochore slows down the process of Mad1 loss. (A) Schematic of how the number of attached microtubules could influence two different properties of Mad1 loss: the decision to complete loss and the speed of loss. (B) Time-lapse imaging (maximum-intensity projection) of representative Mad1 loss kinetics (EYFP-Mad1) and microtubule attachment (SiR-Tubulin) in a Hec1-RNAi PtK2 cell with decreased kinetochore–microtubule affinity (Hec1-9D-FusionRed). Scale bars = 3 µm (large) and 1 µm (zoom), and t = 0 indicates the start of Mad1 loss on the orange-circled kinetochore. (C) Individual (circles) and average (lines) K-K distance in WT (n = 21 pairs) and Hec1-9D (n = 38) cells. (D) Individual (circles) and average (lines) kinetochore–microtubule intensity normalized to cellular astral microtubule intensity in Hec1-9D (n = 22 cells) and WT (n = 14 cells). (E and F) Mean, SEM, and individual trace (E) of the orange-circled kinetochore in B of the Mad1-to-Hec1 intensity ratio with t = 0 being the Mad1 loss start, and distribution of times to reach a 50% intensity ratio (F) of initial Mad1-to-Hec1, in WT cells (n = 21 kinetochores) and Hec1-9D-expressing cells (n = 38). WT data taken from Kuhn and Dumont (2017) and acquired in a parallel experiment. (G and H) Individual (circles) and average (lines) kinetochore EYFP-Mad1 intensity in 5 µM nocodazole (G) or right before Mad1 loss start (H) in Hec1-9D and WT cells. *, P < 0.005, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test).

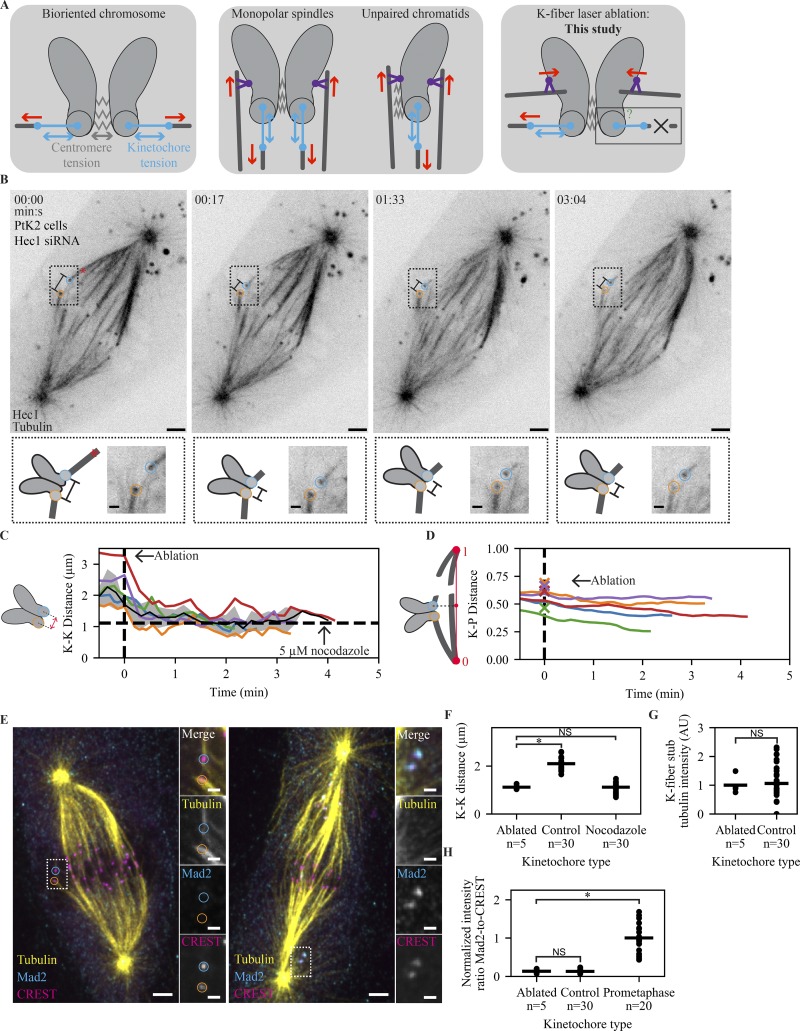

To understand how microtubule occupancy regulates Mad1 localization, it is necessary to define what element of microtubule attachment the SAC detects. Hec1-microtubule binding (Rieder et al., 1995; Waters et al., 1998; O’Connell et al., 2008; Etemad et al., 2015; Tauchman et al., 2015) and the tension generated by spindle-pulling forces (Maresca and Salmon, 2009; Uchida et al., 2009; Janssen et al., 2018) have been proposed to be the cues detected by the SAC. Tension across the centromere is not required for Mad1 removal (Fig. 4 A; Rieder et al., 1995; Waters et al., 1998; O’Connell et al., 2008; Etemad et al., 2015; Tauchman et al., 2015), but tension within an individual kinetochore, which is harder to remove, may be necessary. For example, unpaired kinetochores in cells undergoing mitosis with an unreplicated genome and kinetochores in monopolar spindles can still be under tension given spindle pulling forces on kinetochores and pushing forces on chromosome arms (Fig. 4 A; Rieder et al., 1986; Maresca and Salmon, 2009; Uchida et al., 2009; Cane et al., 2013). To determine whether the SAC responds to force across an individual kinetochore, we used laser ablation to acutely and persistently remove spindle pulling forces without detectably perturbing microtubule occupancy. By cutting the k-fiber close to its kinetochore, we minimized spindle connections and forces (Kajtez et al., 2016; Elting et al., 2017), and without these the ablated k-fiber (stub) cannot pull to move kinetochores. We expressed EGFP-tubulin and human Hec1-EGFP in PtK2 cells (in a Hec1 RNAi background) to assist ablation and response tracking. Human Hec1 has been previously shown to function normally in PtK2 cells (Guimaraes et al., 2008). If Mad1/2 loss requires spindle pulling forces, acutely removing them on attached kinetochores should rerecruit Mad1/2. To allow time for recruitment (∼1.5 min; Clute and Pines, 1999; Dick and Gerlich, 2013), we persistently prevented force generation from k-fiber-spindle reincorporation (Elting et al., 2014; Sikirzhytski et al., 2014) by repeatedly ablating the k-fiber and partially knocking down NuMA (Elting et al., 2014), essential for reincorporation (Hueschen et al., 2017). As predicted, during ablation, the K-K distance dropped to nocodazole-like values (1.11 ± 0.04 µm; Fig. 4, B and C), the disconnected kinetochore persistently moved away from its pole (Fig. 4 D; Khodjakov and Rieder, 1996), and we could not detect significant microtubule intensity between the k-fiber stub and spindle body (Fig. 4 B and Video 2). Thus, the above approach removes productive force generation at individual kinetochores.

Figure 4.

The mammalian SAC does not detect changes in spindle-pulling forces at individual kinetochores. (A) Schematic of different spatial arrangements used to probe the role of tension in the SAC. After biorientation, both centromere and kinetochore are under force (left). Preventing biorientation in monopolar or mitosis with an unreplicated genome spindles removes force (red) across the centromere, but force (red) can still be generated across the kinetochore through polar ejection forces generated by chromokinesins (purple; middle). By removing pulling force using laser ablation (X), force can in principle be generated neither across the centromere nor the kinetochore. (B) Time-lapse imaging of microtubule attachments (EGFP-tubulin) and kinetochores (Hec1-EGFP) in a metaphase PtK2 cell under Hec1 RNAi + partial NuMA RNAi during the mechanical isolation of the highlighted k-fiber (circles) using laser ablation (red X, t = 0). Bottom: Schematic and zoom of highlighted pair. Scale bars = 3 µm (large) and 1 µm (zoom). (C) Mean, SEM, and individual K-K distance of pairs before and after ablation (time of fixation is ∼30 s from the end of trace). Vertical dashed line marks first ablation. Horizontal dashed line marks the average K-K distance in 5 µM nocodazole (n = 30 kinetochores). Example in B is the purple trace. (D) Normalized distance along the pole-to-pole axis for disconnected kinetochores before and after ablation. Dashed line marks first ablation, and X’s indicate ablation position. Example in B is the purple trace. (E) Immunofluorescence imaging (maximum-intensity projection) of microtubule attachment (tubulin), kinetochores (CREST), and SAC activation (Mad2) at (left) the cell in B and (right) a prometaphase cell on the same dish at approximately t = 3:40. Scale bars = 3 µm (large) and 1 µm (zoom). (F–H) Individual (circles) and average (lines) K-K distance (F), k-fiber intensity (G), and SAC activation (H; Mad2/CREST, normalized to prometaphase intensity) at ablated kinetochores (n = 5), same-cell controls without ablation (n = 30), and prometaphase cells on the same dish (n = 20). There is no SAC activation and no change in attachment intensity on sister kinetochores attached to an ablated k-fiber, and ablation reduces K-K distance to a value similar to that in nocodazole (P = 0.40).

To assess SAC signaling after prolonged loss of force, we fixed each ablated cell 3–5 min after the initial cut; stained for Mad2, kinetochores, and tubulin (Fig. 4 E, top); and reimaged each ablated cell. Consistent with force removal, ablating k-fibers led to a decrease in K-K distance compared with control pairs in the same cell (Fig. 4 F; 1.12 ± 0.04 vs. 2.09 ± 0.05 µm, P = 10−4) but had indistinguishable K-K distance from pairs in nocodazole-treated cells (1.12 ± 0.04 vs. 1.11 ± 0.04 µm, P = 0.40). K-fiber microtubule intensity appeared unchanged after ablation (Fig. 4 G; P = 0.42), implying that the timescale of any force-based microtubule destabilization is longer than the time we allowed. There was no detectable increase in Mad2 intensity at kinetochores bound to the ablated k-fiber versus controls with no ablation in the same cell (Fig. 4 E [left] and H, P = 0.45), while unattached kinetochores in nearby cells had higher Mad2 intensity (Fig. 4 E [right] and H, P = 10−4). In contrast, kinetochores in nocodazole-treated cells rapidly rerecruit Mad1 after k-fibers begin to depolymerize (Fig. S3, A and B). We conclude that the SAC does not detect changes in spindle-pulling forces and that microtubule binding itself controls Mad1 localization. Thus, microtubule binding is specifically detected, binding events are independent of each other, and yet the kinetochore monitors microtubule occupancy as a single unit.

Discussion

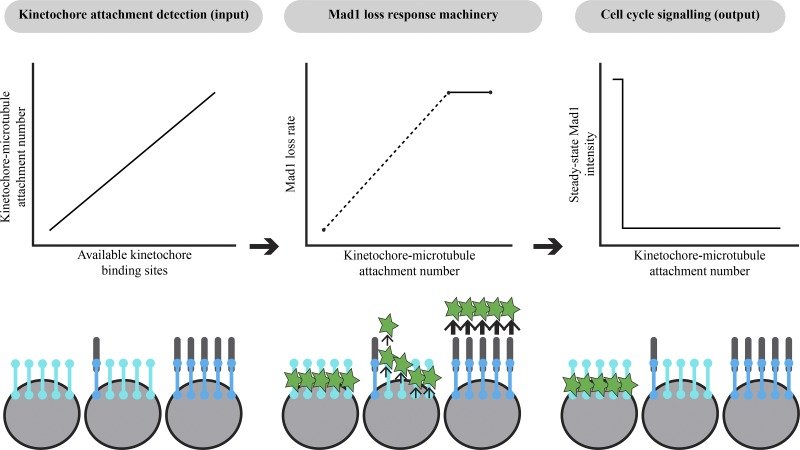

The kinetochore processes input microtubule attachment signals to produce an output SAC signal controlling cell cycle progression. While we can now better define attachment input signals (Waters et al., 1998), the output signal (Mad1 localization; Chen et al., 1998; Maldonado and Kapoor, 2011), and kinetochore structure and biochemistry underlying the SAC, how inputs are detected and how inputs and outputs are quantitatively related remain poorly understood. By developing an approach to tune and fix attachment inputs, here we quantitatively map inputs to SAC outputs (Fig. 5): the kinetochore detects as input the binding (Fig. 4) of microtubules which independently attach to its subunits (Fig. 1), and processes these inputs as a single unit to compute an output response (Fig. 2) and response rate (Fig. 3). Together, our findings provide a quantitative framework for understanding SAC signaling and have implications for both the mechanisms driving the SAC and their cellular function.

Figure 5.

The mammalian kinetochore integrates attachment input signals in a sensitive and switch-like manner. Microtubules bind kinetochore attachment subunits independently rather than cooperatively, leading to a wide range of kinetochore–microtubule attachment numbers (left; Fig. 1). The speed of this response, the loss of Mad1, is sensitive to the number of microtubules attached (middle): Mad1 loss rates are slow at weakly attached kinetochores (Fig. 3) and reach a maximum at kinetochores with WT attachment numbers (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017). However, kinetochores with very low microtubule occupancy are still capable of fully removing Mad1 (Fig. 2), resulting in a decision-making process that is highly sensitive and switch-like (right). The combination of switch-like decision making and a tunable response rate is well suited to allow cells to rapidly exit mitosis while preventing errors (see Discussion).

Using mixed kinetochores, we asked how the disordered kinetochore lawn works as an ensemble to control k-fiber formation and kinetochore decision making. We find that the number of k-fiber microtubules scales linearly with functional Hec1 numbers (Fig. 1), indicating a lack of binding cooperativity. In contrast, the relationship between microtubule binding and SAC decision making is switch like and sensitive (Fig. 2); many kinetochores in our assay cannot reach metaphase levels of microtubule occupancy and yet still lose Mad1, as full-occupancy kinetochores do. Because kinetochore subunits do not bind microtubules cooperatively (Fig. 1), this sensitive behavior must be created downstream of microtubule attachment. Feedback between SAC kinases and phosphatases could, for example, amplify small decreases in kinase activity upon the binding of a few microtubules, creating a switch-like Mad1 loss initiation response that communicates attachment information over the whole kinetochore (Saurin et al., 2011; Funabiki and Wynne, 2013; Nijenhuis et al., 2014).

There are two recent models for how microtubule binding could reduce Mps1 kinase activity: a competition model where microtubules occupy Mps1 binding sites (Hiruma et al., 2015; Ji et al., 2015) and a displacement model where binding distances kinases from substrates (Aravamudhan et al., 2015; Hengeveld et al., 2017). Consistent with both models, microtubule attachment may also increase the kinetochore recruitment of phosphatases that oppose Mps1 (Sivakumar et al., 2016) and are required for SAC satisfaction (Pinsky et al., 2009; Vanoosthuyse and Hardwick, 2009). The signal amplification we observe can explain how, in a binding competition model, metaphase kinetochores with highly variable microtubule occupancy (McEwen et al., 1997) and residual Mps1 localization (Howell et al., 2004) lose Mad1. The observation that Mad1 is not rerecruited to tensionless kinetochores (Fig. 4) indicates biochemical (e.g., binding or conformational change) rather than force-based structural signal detection and supports the idea that signal integration is also biochemical. In a displacement model, our data suggest that displacement does not reflect relevant changes in spindle forces across an individual kinetochore, consistent with observations that changes in intrakinetochore deformations are not themselves force dependent (Magidson et al., 2016). Our observations do not eliminate the possibility that tension is required to remove Mad1 upon microtubule attachment, but not to maintain its removal.

While the decision to complete Mad1 loss is switch like (Fig. 2), we find that the kinetics of Mad1 removal can be tuned by the number of attached microtubules (Fig. 3). The Mad1 loss process, dependent on dynein stripping of its binding partner Spindly in mammals (Howell et al., 2001; Barisic et al., 2010; Gassmann et al., 2010), is likely controlled by one rate-limiting step (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017). Mad1 loss may for example slow down at weakly attached kinetochores because there are fewer dynein tracks available for stripping Mad1. While we know that dynein stripping is regulated by kinetochore protein Cenp-I (Matson and Stukenberg, 2014), how microtubule attachment controls this process is not clear. The discrepancy between the effect of kinetochore–microtubule occupancy on steady-state Mad1 localization (on-off relationship) and on Mad1 loss kinetics (gradual relationship) suggests that different signaling nodes downstream of Mps1 regulate Mad1 steady-state levels and loss kinetics. Previously, neither changing centromere tension nor increasing microtubule occupancy affected Mad1 loss rates (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017), suggesting that with more microtubules, WT kinetics are limited by dynein concentration or kinetochore biochemistry, rather than the number of microtubule tracks.

In addition to their mechanistic implications, our findings suggest how kinetochore signal arrival and processing can contribute to accurate and robust chromosome segregation. First, independent binding of kinetochore subunits to microtubules (Fig. 1) may help prevent reinforcement of incorrect attachments. Second, by having a low-threshold occupancy for Mad1 loss (Fig. 2), cells may ensure that attachments rapidly and robustly turn off the kinetochore’s SAC response. Because metaphase microtubule occupancy is highly variable (McEwen et al., 1997), a high microtubule threshold occupancy for Mad1 loss could lead to transient reactivation at individual bioriented kinetochores; this could result in metaphase delays and consequent DNA damage and cell death (Uetake and Sluder, 2010; Orth et al., 2012). However, low occupancy at anaphase leads to increased segregation errors (Dudka et al., 2018) and a higher probability that unstable, incorrect attachments could lose Mad1 and allow anaphase entry. Thus, and third, slowing Mad1 loss on kinetochores with low microtubule occupancy (Fig. 3) may prevent rapid Mad1 loss on transient, incorrect attachments and provide time for error correction mechanisms to act (Tanaka et al., 2002). Looking forward, uncovering the mechanisms determining the rate of Mad1 loss and the number of required kinetochore–microtubules for Mad1 loss will not only reveal the basis for kinetochore signal processing, but enable us to probe its impact on accurate and timely chromosome segregation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

PtK2 EYFP-Mad1 (Shah et al., 2004; gift from Jagesh Shah, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) and WT cells were cultured in MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with sodium pyruvate (11360; Thermo Fisher Scientific), nonessential amino acids (11140; Thermo Fisher Scientific), penicillin/streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated FBS (10438; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Tet-on inducible CRISPR-Cas9 HeLa cells (Hec1 knockout cells, gift from Iain Cheeseman, Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA) were cultured in DMEM/F12 with GlutaMAX (10565018; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, 5 µg/ml puromycin, and tetracycline-screened FBS (SH30070.03T; Hyclone Labs). Cas9 expression was induced by the addition of 1 µM doxycycline hyclate 48 h before fixation. Knockout was confirmed by Western blot and the accumulation of mitotic cells after doxycycline addition. Cell lines were not short tandem repeat profiled for authentication. All cell lines tested were negative for mycoplasma. Cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. For imaging, cells were plated on 35-mm #1.5 glass-bottom dishes (poly-d-lysine coated, MatTek; Figs. 3 and S3), 25-mm #1.5 glass-etched coverslips (acid cleaned and poly-l-lysine coated; G490; ProSciTech; Fig. 4), or 25-mm #1.5 glass coverslips (acid cleaned and poly-l-lysine coated; 0117650; Marienfeld; Figs. 1, 2, S1, and S2). Cells were transfected with EGFP-Tubulin (Clontech), Hec1-WT-EGFP (gift from Jennifer DeLuca, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO), mCherry-CenpC (gift from Aaron Straight, Stanford University, Stanford, CA), Hec1-8AS8D-EGFP (1D-EGFP; gift from J. DeLuca), and Hec1-9D-FusionRed. FusionRed (gift from Michael Davidson, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL) was swapped for EGFP in Hec1-9D-EGFP (gift from J. DeLuca) using ViaFect (E4981; Promega) 48 h (HeLa) or 72 h (PtK2) before imaging. For siRNA knockdown, cells were treated with 100 nM siRNA oligos (Sigma-Aldrich) and 4 µl oligofectamine (12252011; Thermo Fisher Scientific) either 24 h (Fig. 3) or 6 h (Fig. 4) after transfection (66 or 48 h before imaging, respectively). The following oligonucleotides were used: siNuMA, 5′-GCATAAAGCGGAGACUAAA-3′ (Elting et al., 2017) and siHec1, 5′-AATGAGCCGAATCGTCTAATA-3′ (Guimaraes et al., 2008).

Immunofluorescence

For “ablate and fix” experiments (Fig. 4) and Hec1 knockout confirmation (Fig. S1), cells were fixed in 95% methanol and 5 mM EGTA for 1 min on ice. Cells were then blocked at room temperature for 1.5 h in TBST (Tris-Buffered Saline + Triton, 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Triton X-100, pH 7.6) plus 2% BSA. Primary and secondary antibody incubations were done in blocking solution for 1 h and 30 min, respectively. Between each step, fourwashes for five minutes each in TBST were performed. For mixed kinetochore immunofluorescence (Figs. 1, 2, S1 [except Mps1], and S2), cells were preextracted in PHEM (120 mM Pipes, 50 mM Hepes, 20 mM EGTA, and 4 mM magnesium acetate, pH 7) plus 1% Triton X-100 for 20 s then fixed for 15 min in PHEM plus 4% PFA (freshly dissolved from powder) at 37°C. Cells were then permeabilized in PHEM plus 0.5% IGEPAL-CA-630 (octylphenoxy poly(ethyleneoxy)ethanol) for 10 min and blocked in PHEM plus 0.05% Triton X-100 and 2% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Both the primary and secondary antibody incubations were done in block solution at 37°C for 1 h. Between each step (excluding preextraction), four 5-min washes in PHEM plus 0.05% Triton X-100 were performed; PFA staining protocol was adapted from Suzuki et al. (2018). In the case of the four-color dual staining with Mad1 and tubulin (Fig. S2), cells were first stained for FusionRed alone using the above protocol, then blocked with anti-rabbit IgG at 37°C for 1 h. After four 5-min washes, cells were stained for tubulin, Mad1, and EGFP using the above protocol minus the fixation, permeabilization, and BSA block. Because the Mps1 antibody (Fig. S2) was not amenable to the above protocol, for this experiment cells were instead fixed in PBS plus 3.7% PFA and 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 s, permeabilized in PBS plus 0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 min, fixed again in 3.7% PFA plus 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in PBS plus 3% BSA. Primary and secondary antibody incubations were done for 1 h. All steps were done at room temperature. Between each step after the second fixation, four 5-min washes in PBS were performed; Mps1 staining protocol was adapted from Ballister et al. (2014).

For all experiments, cells were mounted in ProLong Gold (P10144; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored in the dark at 4°C. The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-α-tubulin DM1 (1:1,000; T6199; Sigma-Aldrich), human anti-centromere (CREST; 1:25; discontinued; Antibodies Inc.), rabbit anti-rat kangaroo-Mad2 (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017; DeLuca et al., 2018; 1:100), mouse anti-Hec1 (9G3; 1:100, ab3613; Abcam), rabbit anti-mKate (recognizes FusionRed; 1:200; TA150072; OriGene), mouse anti-hsMad1 (1:300; MABE867; EMD-Millipore), rabbit anti-α-tubulin (1:200; ab18251; Abcam), mouse anti-Mps1 (4-112-3; 1:100; 05-683; EMD-Millipore), mouse anti-ZW10 (1:100; sc-81430; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit anti-Aurora B (1:100; ab2254; Abcam), camel anti-EGFP conjugated to Atto488 (1:100; added during secondary; gba-488; ChromoTek), camel anti-RFP conjugated to Atto594 (1:100; added during secondary; rba-594; ChromoTek), anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:500) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (A11001; Invitrogen) or Alexa Fluor 647 (A21236; Invitrogen), anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:500) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 405 (A-31556; Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 488 (A11008; Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568 (A11011; Invitrogen), or Alexa Fluor 647 (A21244; Invitrogen), and a human secondary antibody conjugated to DyLight 405 (1:100; 109-475-098; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Drug and dye treatments

To depolymerize spindle microtubules (Figs. 3, S1, S2, and S3), 5 µM nocodazole (M1404; Sigma-Aldrich) was added 10 min before imaging (Fig. 3), 10 min before fixation (Fig. 4), or 1 h before fixation (Figs. S1 and S2) or 10 µM was added at the indicated time (Fig. S3). To prevent anaphase onset (Figs. 1, 2, S1, and S2) cells were treated with 5 µM MG132 (474790; EMD-Millipore) 1 h before fixation. To visualize tubulin as a third color (Fig. 3), 100 nM SiR-Tubulin dye (cy-sc002; Cytoskeleton) was added 1 h before imaging, along with 10 µM verapamil (V4629; Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent dye efflux.

Imaging

All imaging was performed on an inverted (Eclipse Ti-E; Nikon), spinning-disk confocal microscope (CSU-X1; Yokogawa Electric Corporation). Single-color live imaging (Fig. 4) was performed with a Di01-T488-13 × 15 × 0.5 head dichroic (Semrock) along with a 488-nm (120 mW) diode laser, an ET500LP emission filter (Chroma), and an iXon3 camera (Andor Technology; bin = 1, 105 nm/pixel). For these experiments, cells were imaged in phase contrast (400-ms exposure) and fluorescence (60-ms exposure) in three z-planes spaced 700 nm apart every 7.5–15 s with a 100× 1.45 Ph3 oil objective through a 1.5× lens with 5× preamplifier gain and no electron-multiplying gain (Metamorph 7.7.8.0; Molecular Devices).

Three-color live imaging (Figs. 3 and S3) was performed with a Di01-T405/488/568/647 head dichroic (Semrock) instead, along with 561-nm (150-mW) and 642-nm (100-mW) diode lasers and different emission filters (ET525/50M, ET630/75M, and ET690/50M; Chroma). Cells were imaged by phase contrast (200-ms exposure) and fluorescence (40–75-ms exposure) in four z-planes spaced 350 nm apart every 13–30 s and at bin = 2 (to improve imaging contrast for dim Mad1 and microtubule structures; 210 nm/pixel). All live PtK2 cells were imaged at 30°C, 5% CO2 in a closed, humidity-controlled Tokai Hit PLAM chamber. To quantify Mad1 recruitment in PtK2 cells in nocodazole (Fig. 3), whole-cell images were acquired in z-slices 350 nm apart on a Zyla complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) camera (Andor Technology; bin = 1, 65 nm/pixel) with imaging parameters identical to those above.

For fixed-cell imaging (Figs. 1, 2, 4, S1, and S2), a 405-nm (100-mW) laser was added along with an ET455/50M emission filter (Chroma), and two emission filters were changed to ET525/36M and ET600/50M (Chroma). Cell images were acquired in z-slices 300 nm apart with bin = 1 and laser powers, exposure times, and electron-multiplying gain optimized (but not changed between cells) to fill as much of the dynamic range of the camera as possible without saturation. For mixed kinetochore experiments (Figs. 1, 2, S1, and S2), all acquisition settings for EGFP and FusionRed or mRuby2 were kept identical. To assess the efficiency of Hec1 knockout in Hec1 knockout cells (Fig. S1), fixed cells stained for Hec1, kinetochores, and microtubules were assessed visually using these same imaging conditions.

Ablation protocol

Laser ablation (20 3-ns pulses at 20 Hz) with 551-nm light was performed using the MicroPoint Laser System (Photonic Instruments). Images were acquired more slowly before ablation and then acquired more rapidly after ablation (typically 7.5 s before and 15 s after). Successful k-fiber ablation was verified by loss of tension across the centromere (Fig. 1). To prevent k-fiber reincorporation into the spindle (Elting et al., 2014; Sikirzhytski et al., 2014), the spindle area around the k-fiber was also ablated concurrently, and the minus-end of the k-fiber was reablated periodically before fixation.

Cell selection

For laser ablation (Fig. 4), metaphase cells with minor pole-focusing defects and wavy spindle morphology, indicative of partial NuMA knockdown, and visible Hec1-EGFP expression were chosen. In addition, Hec1 knockdown was confirmed by the lack of k-fibers and irregular motion of chromosomes in EGFP-negative cells. For imaging Mad1 loss (Fig. 3), prometaphase cells with moderate Mad1-EFYP expression, high Hec1-9D-FusionRed expression, and low average K-K distances (to indicate lack of strong attachments) were chosen. Hec1 knockdown was confirmed by the lack of k-fibers and irregular motion of chromosomes in FusionRed-negative cells.

Data analysis

Tracking and feature identification

For live ablation experiments (Fig. 4), kinetochores (Hec1-EGFP) and poles (EGFP-tubulin) were tracked by hand using a custom-made Matlab (Mathworks) graphical user interface (GUI). Pairs were then included in further analysis if they exhibited prolonged decrease in K-K distance after ablation. For nocodazole addition experiments (Fig. S3), kinetochores (CenpC-mCherry) and k-fibers (SiR-tubulin) were tracked by hand in a custom Matlab GUI using the plane of brightest CenpC intensity (for kinetochores) or SiR-tubulin (for k-fibers). For live imaging of Mad1 intensity (Fig. 2), kinetochores were tracked as previously (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017), using Matlab program SpeckleTracker (Wan et al., 2012). For analysis of fixed images (Figs. 1, 2, 4, S1, and S2), kinetochores were identified by hand in a custom Matlab GUI using the plane of brightest Hec1 or CREST intensity and k-fibers were identified as bundles of tubulin intensity (where applicable).

Intensity measurements

Fixed kinetochore intensities (Figs. 1, 2, 4, S1, and S2) were measured in Matlab by summing pixel intensities in a 7 × 7-pixel (0.73 × 0.73-µm) box centered at the indicated coordinate. To calculate the Mad2/CREST ratio (Fig. 4) and Mad1 kinetochore intensity (Fig. 2), intensities were background-corrected by dividing (Fig. 4) or subtracting (Fig. 2) the kinetochore intensity by the average of three background intensities. To calculate the fraction EGFP (Figs. 1 and 2), the kinetochore EGFP intensity (background subtracted) was divided by the sum of the kinetochore EGFP and FusionRed intensity (both background subtracted). To avoid negative numbers, corrected intensities less than zero were recorded as zero. To calculate tubulin intensity on a given kinetochore, two 0.5-µm-long intensity linescans were taken for each kinetochore: one (Tubin) perpendicular to the kinetochore-kinetochore axis 0.25 µm away from the kinetochore toward its sister, and one (Tubout) perpendicular to the kinetochore–microtubule axis 0.25 µm away from the kinetochore toward the microtubule. The microtubule attachment intensity is the difference between Tubout and Tubin. To account for variance in staining between coverslips, all tubulin intensities were normalized to the intensity of a 7 × 7-pixel box centered on the spindle pole. Because of high variability in intensity between experiments, the data displayed for mixed kinetochore experiments (Figs. 1, 2, S1, and S2) are drawn from single immunofluorescence experiments. However, two to three biological replicates were performed in all cases.

To determine Mad1 loss rates (Fig. 3), we measured EYFP-Mad1 and FusionRed-Hec1-9D intensities at each time point following a protocol identical to the one used to measure Mad1 loss rates previously (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017). In short, videos were thresholded by setting to zero all pixels <2 SDs above image background at the first frame. For each time point, the intensities of all pixels in a 5 × 5-pixel (1.05 × 1.05-µm) box around the kinetochore were summed over all planes. We did not detect significant bleaching over the course of the video. t = 0 was set to the time for each kinetochore where Mad1 intensity started decreasing while Hec1 intensity stayed constant, and intensities were normalized to the average intensity for t = −100 to t = 0 (Kuhn and Dumont, 2017). To determine the relative microtubule attachment intensity in Hec-1-9D and WT cells, two points were placed along k-fibers and astral microtubules in these same cells using a custom Matlab GUI, and then a 1-µm intensity linescan was taken perpendicular to a line between these two points. To correct for background, a similar linescan was drawn in the cell periphery and subtracted from both values. To normalize for different cellular SiR-tubulin levels, all k-fiber intensities in a cell were normalized to an average cellular astral microtubule intensity. To measure EYFP-Mad1 recruitment in nocodazole-treated Hec1-9D-FusionRed and WT PtK2 cells, kinetochores were identified using Hec1-9D-FusionRed (9D) or CenpC-mCherry (WT), and then kinetochore Mad1 intensity was calculated summing pixel intensities inside a 10 × 10-pixel (0.65 × 0.65-µm) box centered at the kinetochore. To correct for background, the average intensity of six nonkinetochore boxes was subtracted from all kinetochore intensities.

To determine Mad1 accumulation timing relative to kinetochore–microtubule attachment loss after nocodazole addition (Fig. S3, A and B), we measured EYFP-Mad1 and CenpC-mCherry at every time point by summing all pixel intensities across all planes in a 5 × 5-pixel (1.05 × 1.05-µm) box centered at the indicated kinetochore coordinate. To measure k-fiber intensity, an intensity linescan was taken along a 1-µm line perpendicular to a line drawn between the kinetochore coordinate and its corresponding k-fiber coordinate, 1 µm away from the kinetochore. t = 0 was set to the time for each kinetochore where k-fiber intensity started decreasing, and intensities were normalized to the average intensity for t = −100 to t = 0. All code used in intensity calculations is available upon request.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Calculations of P values (Mann–Whitney U and one-way ANOVA) and correlation coefficients (Spearman rank-order) were done using Scipy and Numpy Python modules. To calculate the relationship between the fraction EGFP and the number of attached microtubules, a linear regression (least-squares) was applied to the data using Scipy. The lower limit of fraction of a metaphase attachment is calculated as the ratio between attachment numbers at the lowest average fraction EGFP cell with Mad1-negative kinetochores in the mixed population from Fig. 2 and the attachment number at fraction EGFP = 1. Alternative calculations (Fig. S2) instead used the average fraction EGFP in the Hec1-1D–alone population for the denominator or the average fraction EGFP in the Hec1-9D–alone population for the numerator. Sample sizes were determined by the number of cells that fulfilled listed criteria out of an initial dataset (Figs. 3 and 4) or by the number of detectably expressing cells on a coverslip (Figs. 1 and 2).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that Hec1-1D, but not 9D, rescues spindle defects after Hec1 depletion; related to Fig. 1. Fig. S2 shows that Hec1-1D, but not 9D, allows for robust Mad1 loss after Hec1 depletion; related to Fig. 2. Fig. S3 shows that Mad1 rerecruitment is associated with microtubule loss; related to Fig. 4 A. Video 1 shows that lowering microtubule occupancy at a kinetochore slows down the process of Mad1 loss. Video 2 shows mechanical isolation of a kinetochore-fiber from a metaphase spindle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jagesh Shah for EYFP-Mad1 PtK2 cells; Iain Cheeseman for Hec1-inducible knockout HeLa cells; Michael Davidson for the FusionRed construct; Aaron Straight for the mCherry-CenpC construct; Jennifer DeLuca for the Hec1-9D-EGFP, Hec1-WT-EGFP, and Hec1-1D-EGFP constructs; Jennifer DeLuca and Jeanne Mick (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO) for the rat kangaroo Mad2 antibody; Eline ter Steege for preliminary experiments; Ted Salmon and Arshad Desai for discussions; David Morgan and Fred Chang for critical reading of the manuscript; and the Dumont laboratory for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Benafsheh Etemad and Geert Kops for sharing data before publication.

This work was funded by National Institutes of Health DP2GM119177 (S. Dumont), the Rita Allen Foundation and Searle Scholars’ Program (S. Dumont), the National Science Foundation Center for Cellular Construction 1548297 (S. Dumont), and a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship (J. Kuhn).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: J. Kuhn developed methodology, performed experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. J. Kuhn and S. Dumont conceived the project and designed experiments. S. Dumont edited the manuscript.

References

- Akiyoshi B., Sarangapani K.K., Powers A.F., Nelson C.R., Reichow S.L., Arellano-Santoyo H., Gonen T., Ranish J.A., Asbury C.L., and Biggins S.. 2010. Tension directly stabilizes reconstituted kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Nature. 468:576–579. 10.1038/nature09594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alushin G.M., Ramey V.H., Pasqualato S., Ball D.A., Grigorieff N., Musacchio A., and Nogales E.. 2010. The Ndc80 kinetochore complex forms oligomeric arrays along microtubules. Nature. 467:805–810. 10.1038/nature09423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravamudhan P., Goldfarb A.A., and Joglekar A.P.. 2015. The kinetochore encodes a mechanical switch to disrupt spindle assembly checkpoint signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 17:868–879. 10.1038/ncb3179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballister E.R., Riegman M., and Lampson M.A.. 2014. Recruitment of Mad1 to metaphase kinetochores is sufficient to reactivate the mitotic checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 204:901–908. 10.1083/jcb.201311113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisic M., Sohm B., Mikolcevic P., Wandke C., Rauch V., Ringer T., Hess M., Bonn G., and Geley S.. 2010. Spindly/CCDC99 is required for efficient chromosome congression and mitotic checkpoint regulation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21:1968–1981. 10.1091/mbc.e09-04-0356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane S., Ye A.A., Luks-Morgan S.J., and Maresca T.J.. 2013. Elevated polar ejection forces stabilize kinetochore-microtubule attachments. J. Cell Biol. 200:203–218. 10.1083/jcb.201211119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman I.M., Chappie J.S., Wilson-Kubalek E.M., and Desai A.. 2006. The conserved KMN network constitutes the core microtubule-binding site of the kinetochore. Cell. 127:983–997. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R.H., Shevchenko A., Mann M., and Murray A.W.. 1998. Spindle checkpoint protein Xmad1 recruits Xmad2 to unattached kinetochores. J. Cell Biol. 143:283–295. 10.1083/jcb.143.2.283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciferri C., Pasqualato S., Screpanti E., Varetti G., Santaguida S., Dos Reis G., Maiolica A., Polka J., De Luca J.G., De Wulf P., et al. . 2008. Implications for kinetochore-microtubule attachment from the structure of an engineered Ndc80 complex. Cell. 133:427–439. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clute P., and Pines J.. 1999. Temporal and spatial control of cyclin B1 destruction in metaphase. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:82–87. 10.1038/10049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David A.F., Roudot P., Legant W.R., Betzig E., Danuser G., and Gerlich D.W.. 2019. Augmin accumulation on long-lived microtubules drives amplification and kinetochore-directed growth. J. Cell Biol. 218:2150–2168. 10.1083/jcb.201805044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Antoni A., Pearson C.G., Cimini D., Canman J.C., Sala V., Nezi L., Mapelli M., Sironi L., Faretta M., Salmon E.D., and Musacchio A.. 2005. The Mad1/Mad2 complex as a template for Mad2 activation in the spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 15:214–225. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J.G., Howell B.J., Canman J.C., Hickey J.M., Fang G., and Salmon E.D.. 2003. Nuf2 and Hec1 are required for retention of the checkpoint proteins Mad1 and Mad2 to kinetochores. Curr. Biol. 13:2103–2109. 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J.G., Gall W.E., Ciferri C., Cimini D., Musacchio A., and Salmon E.D.. 2006. Kinetochore microtubule dynamics and attachment stability are regulated by Hec1. Cell. 127:969–982. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca K.F., Meppelink A., Broad A.J., Mick J.E., Peersen O.B., Pektas S., Lens S.M.A., and DeLuca J.G.. 2018. Aurora A kinase phosphorylates Hec1 to regulate metaphase kinetochore-microtubule dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 217:163–177. 10.1083/jcb.201707160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick A.E., and Gerlich D.W.. 2013. Kinetic framework of spindle assembly checkpoint signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 15:1370–1377. 10.1038/ncb2842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudka D., Noatynska A., Smith C.A., Liaudet N., McAinsh A.D., and Meraldi P.. 2018. Complete microtubule-kinetochore occupancy favours the segregation of merotelic attachments. Nat. Commun. 9:2042 10.1038/s41467-018-04427-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elting M.W., Hueschen C.L., Udy D.B., and Dumont S.. 2014. Force on spindle microtubule minus ends moves chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 206:245–256. 10.1083/jcb.201401091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elting M.W., Prakash M., Udy D.B., and Dumont S.. 2017. Mapping Load-Bearing in the Mammalian Spindle Reveals Local Kinetochore Fiber Anchorage that Provides Mechanical Isolation and Redundancy. Curr. Biol. 27:2112–2122.e5. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemad B., Kuijt T.E.F., and Kops G.J.P.L.. 2015. Kinetochore-microtubule attachment is sufficient to satisfy the human spindle assembly checkpoint. Nat. Commun. 6:8987 10.1038/ncomms9987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etemad B., Vertesy A., Kuijt T.E.F., Sacristan C., van Oudenaarden A., and Kops G.J.P.L.. 2019. Spindle checkpoint silencing at kinetochores with submaximal microtubule occupancy. J. Cell Sci. 132:231589 10.1242/jcs.231589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funabiki H., and Wynne D.J.. 2013. Making an effective switch at the kinetochore by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Chromosoma. 122:135–158. 10.1007/s00412-013-0401-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann R., Holland A.J., Varma D., Wan X., Civril F., Cleveland D.W., Oegema K., Salmon E.D., and Desai A.. 2010. Removal of Spindly from microtubule-attached kinetochores controls spindle checkpoint silencing in human cells. Genes Dev. 24:957–971. 10.1101/gad.1886810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes G.J., Dong Y., McEwen B.F., and Deluca J.G.. 2008. Kinetochore-microtubule attachment relies on the disordered N-terminal tail domain of Hec1. Curr. Biol. 18:1778–1784. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengeveld R.C.C., Vromans M.J.M., Vleugel M., Hadders M.A., and Lens S.M.A.. 2017. Inner centromere localization of the CPC maintains centromere cohesion and allows mitotic checkpoint silencing. Nat. Commun. 8:15542 10.1038/ncomms15542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt L., Tighe A., Santaguida S., White A.M., Jones C.D., Musacchio A., Green S., and Taylor S.S.. 2010. Sustained Mps1 activity is required in mitosis to recruit O-Mad2 to the Mad1-C-Mad2 core complex. J. Cell Biol. 190:25–34. 10.1083/jcb.201002133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma Y., Sacristan C., Pachis S.T., Adamopoulos A., Kuijt T., Ubbink M., von Castelmur E., Perrakis A., and Kops G.J.P.L.. 2015. Competition between MPS1 and microtubules at kinetochores regulates spindle checkpoint signaling. Science. 348:1264–1267. 10.1126/science.aaa4055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell B.J., McEwen B.F., Canman J.C., Hoffman D.B., Farrar E.M., Rieder C.L., and Salmon E.D.. 2001. Cytoplasmic dynein/dynactin drives kinetochore protein transport to the spindle poles and has a role in mitotic spindle checkpoint inactivation. J. Cell Biol. 155:1159–1172. 10.1083/jcb.200105093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell B.J., Moree B., Farrar E.M., Stewart S., Fang G., and Salmon E.D.. 2004. Spindle checkpoint protein dynamics at kinetochores in living cells. Curr. Biol. 14:953–964. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueschen C.L., Kenny S.J., Xu K., and Dumont S.. 2017. NuMA recruits dynein activity to microtubule minus-ends at mitosis. eLife. 6:e29328 10.7554/eLife.29328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen L.M.E., Averink T.V., Blomen V.A., Brummelkamp T.R., Medema R.H., and Raaijmakers J.A.. 2018. Loss of Kif18A Results in Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Activation at Microtubule-Attached Kinetochores. Curr. Biol. 28:2685–2696.e4. 10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelluma N., Dansen T.B., Sliedrecht T., Kwiatkowski N.P., and Kops G.J.P.L.. 2010. Release of Mps1 from kinetochores is crucial for timely anaphase onset. J. Cell Biol. 191:281–290. 10.1083/jcb.201003038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Z., Gao H., and Yu H.. 2015. Kinetochore attachment sensed by competitive Mps1 and microtubule binding to Ndc80C. Science. 348:1260–1264. 10.1126/science.aaa4029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston K., Joglekar A., Hori T., Suzuki A., Fukagawa T., and Salmon E.D.. 2010. Vertebrate kinetochore protein architecture: protein copy number. J. Cell Biol. 189:937–943. 10.1083/jcb.200912022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajtez J., Solomatina A., Novak M., Polak B., Vukušić K., Rüdiger J., Cojoc G., Milas A., Šumanovac Šestak I., Risteski P., et al. . 2016. Overlap microtubules link sister k-fibres and balance the forces on bi-oriented kinetochores. Nat. Commun. 7:10298 10.1038/ncomms10298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodjakov A., and Rieder C.L.. 1996. Kinetochores moving away from their associated pole do not exert a significant pushing force on the chromosome. J. Cell Biol. 135:315–327. 10.1083/jcb.135.2.315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn J., and Dumont S.. 2017. Spindle assembly checkpoint satisfaction occurs via end-on but not lateral attachments under tension. J. Cell Biol. 216:1533–1542. 10.1083/jcb.201611104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London N., and Biggins S.. 2014. Mad1 kinetochore recruitment by Mps1-mediated phosphorylation of Bub1 signals the spindle checkpoint. Genes Dev. 28:140–152. 10.1101/gad.233700.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long A.F., Udy D.B., and Dumont S.. 2017. Hec1 Tail Phosphorylation Differentially Regulates Mammalian Kinetochore Coupling to Polymerizing and Depolymerizing Microtubules. Curr. Biol. 27:1692–1699.e3. 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukinavičius G., Reymond L., D’Este E., Masharina A., Göttfert F., Ta H., Güther A., Fournier M., Rizzo S., Waldmann H., et al. . 2014. Fluorogenic probes for live-cell imaging of the cytoskeleton. Nat. Methods. 11:731–733. 10.1038/nmeth.2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciejowski J., George K.A., Terret M.-E., Zhang C., Shokat K.M., and Jallepalli P.V.. 2010. Mps1 directs the assembly of Cdc20 inhibitory complexes during interphase and mitosis to control M phase timing and spindle checkpoint signaling. J. Cell Biol. 190:89–100. 10.1083/jcb.201001050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magidson V., He J., Ault J.G., O’Connell C.B., Yang N., Tikhonenko I., McEwen B.F., Sui H., and Khodjakov A.. 2016. Unattached kinetochores rather than intrakinetochore tension arrest mitosis in taxol-treated cells. J. Cell Biol. 212:307–319. 10.1083/jcb.201412139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M., and Kapoor T.M.. 2011. Constitutive Mad1 targeting to kinetochores uncouples checkpoint signalling from chromosome biorientation. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:475–482. 10.1038/ncb2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresca T.J., and Salmon E.D.. 2009. Intrakinetochore stretch is associated with changes in kinetochore phosphorylation and spindle assembly checkpoint activity. J. Cell Biol. 184:373–381. 10.1083/jcb.200808130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Lluesma S., Stucke V.M., and Nigg E.A.. 2002. Role of Hec1 in spindle checkpoint signaling and kinetochore recruitment of Mad1/Mad2. Science. 297:2267–2270. 10.1126/science.1075596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson D.R., and Stukenberg P.T.. 2014. CENP-I and Aurora B act as a molecular switch that ties RZZ/Mad1 recruitment to kinetochore attachment status. J. Cell Biol. 205:541–554. 10.1083/jcb.201307137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B.F., Heagle A.B., Cassels G.O., Buttle K.F., and Rieder C.L.. 1997. Kinetochore fiber maturation in PtK1 cells and its implications for the mechanisms of chromosome congression and anaphase onset. J. Cell Biol. 137:1567–1580. 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J.R. 1991. Structural and mechanical control of mitotic progression. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 56:613–619. 10.1101/SQB.1991.056.01.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley K.L., and Cheeseman I.M.. 2017. Large-Scale Analysis of CRISPR/Cas9 Cell-Cycle Knockouts Reveals the Diversity of p53-Dependent Responses to Cell-Cycle Defects. Dev. Cell. 40:405–420.e2. 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijenhuis W., Vallardi G., Teixeira A., Kops G.J.P.L., and Saurin A.T.. 2014. Negative feedback at kinetochores underlies a responsive spindle checkpoint signal. Nat. Cell Biol. 16:1257–1264. 10.1038/ncb3065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell C.B., Loncarek J., Hergert P., Kourtidis A., Conklin D.S., and Khodjakov A.. 2008. The spindle assembly checkpoint is satisfied in the absence of interkinetochore tension during mitosis with unreplicated genomes. J. Cell Biol. 183:29–36. 10.1083/jcb.200801038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth J.D., Loewer A., Lahav G., and Mitchison T.J.. 2012. Prolonged mitotic arrest triggers partial activation of apoptosis, resulting in DNA damage and p53 induction. Mol. Biol. Cell. 23:567–576. 10.1091/mbc.e11-09-0781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J.B., and Ris H.. 1976. Electron-microscopic study of the spindle and chromosome movement in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 22:219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky B.A., Nelson C.R., and Biggins S.. 2009. Protein phosphatase 1 regulates exit from the spindle checkpoint in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 19:1182–1187. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder C.L., Davison E.A., Jensen L.C., Cassimeris L., and Salmon E.D.. 1986. Oscillatory movements of monooriented chromosomes and their position relative to the spindle pole result from the ejection properties of the aster and half-spindle. J. Cell Biol. 103:581–591. 10.1083/jcb.103.2.581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder C.L., Cole R.W., Khodjakov A., and Sluder G.. 1995. The checkpoint delaying anaphase in response to chromosome monoorientation is mediated by an inhibitory signal produced by unattached kinetochores. J. Cell Biol. 130:941–948. 10.1083/jcb.130.4.941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaguida S., Tighe A., D’Alise A.M., Taylor S.S., and Musacchio A.. 2010. Dissecting the role of MPS1 in chromosome biorientation and the spindle checkpoint through the small molecule inhibitor reversine. J. Cell Biol. 190:73–87. 10.1083/jcb.201001036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarangapani K.K., and Asbury C.L.. 2014. Catch and release: how do kinetochores hook the right microtubules during mitosis? Trends Genet. 30:150–159. 10.1016/j.tig.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin A.T., van der Waal M.S., Medema R.H., Lens S.M.A., and Kops G.J.P.L.. 2011. Aurora B potentiates Mps1 activation to ensure rapid checkpoint establishment at the onset of mitosis. Nat. Commun. 2:316 10.1038/ncomms1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah J.V., Botvinick E., Bonday Z., Furnari F., Berns M., and Cleveland D.W.. 2004. Dynamics of centromere and kinetochore proteins; implications for checkpoint signaling and silencing. Curr. Biol. 14:942–952. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikirzhytski V., Magidson V., Steinman J.B., He J., Le Berre M., Tikhonenko I., Ault J.G., McEwen B.F., Chen J.K., Sui H., et al. . 2014. Direct kinetochore-spindle pole connections are not required for chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 206:231–243. 10.1083/jcb.201401090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikirzhytski V., Renda F., Tikhonenko I., Magidson V., McEwen B.F., and Khodjakov A.. 2018. Microtubules assemble near most kinetochores during early prometaphase in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 217:2647–2659. 10.1083/jcb.201710094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar S., Janczyk P.Ł., Qu Q., Brautigam C.A., Stukenberg P.T., Yu H., and Gorbsky G.J.. 2016. The human SKA complex drives the metaphase-anaphase cell cycle transition by recruiting protein phosphatase 1 to kinetochores. eLife. 5:e12902 10.7554/eLife.12902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin L.J.R., Guimaraes G.J., and Deluca J.G.. 2011. The NDC80 complex proteins Nuf2 and Hec1 make distinct contributions to kinetochore-microtubule attachment in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 22:759–768. 10.1091/mbc.e10-08-0671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Badger B.L., and Salmon E.D.. 2015. A quantitative description of Ndc80 complex linkage to human kinetochores. Nat. Commun. 6:8161 10.1038/ncomms9161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Long S.K., and Salmon E.D.. 2018. An optimized method for 3D fluorescence co-localization applied to human kinetochore protein architecture. eLife. 7:e32418 10.7554/eLife.32418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T.U., Rachidi N., Janke C., Pereira G., Galova M., Schiebel E., Stark M.J.R., and Nasmyth K.. 2002. Evidence that the Ipl1-Sli15 (Aurora kinase-INCENP) complex promotes chromosome bi-orientation by altering kinetochore-spindle pole connections. Cell. 108:317–329. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00633-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauchman E.C., Boehm F.J., and DeLuca J.G.. 2015. Stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment is sufficient to silence the spindle assembly checkpoint in human cells. Nat. Commun. 6:10036 10.1038/ncomms10036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida K.S.K., Takagaki K., Kumada K., Hirayama Y., Noda T., and Hirota T.. 2009. Kinetochore stretching inactivates the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 184:383–390. 10.1083/jcb.200811028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetake Y., and Sluder G.. 2010. Prolonged prometaphase blocks daughter cell proliferation despite normal completion of mitosis. Curr. Biol. 20:1666–1671. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanoosthuyse V., and Hardwick K.G.. 2009. A novel protein phosphatase 1-dependent spindle checkpoint silencing mechanism. Curr. Biol. 19:1176–1181. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkov V.A., Huis In’t Veld P.J., Dogterom M., and Musacchio A.. 2018. Multivalency of NDC80 in the outer kinetochore is essential to track shortening microtubules and generate forces. eLife. 7:e36764 10.7554/eLife.36764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X., Cimini D., Cameron L.A., and Salmon E.D.. 2012. The coupling between sister kinetochore directional instability and oscillations in centromere stretch in metaphase PtK1 cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 23:1035–1046. 10.1091/mbc.e11-09-0767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters J.C., Chen R.H., Murray A.W., and Salmon E.D.. 1998. Localization of Mad2 to kinetochores depends on microtubule attachment, not tension. J. Cell Biol. 141:1181–1191. 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendell K.L., Wilson L., and Jordan M.A.. 1993. Mitotic block in HeLa cells by vinblastine: ultrastructural changes in kinetochore-microtubule attachment and in centrosomes. J. Cell Sci. 104:261–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik E., Basto R., Serr M., Scaërou F., Karess R., and Hays T.. 2001. Kinetochore dynein: its dynamics and role in the transport of the Rough deal checkpoint protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:1001–1007. 10.1038/ncb1101-1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo T.Y., Choi J.-M., Conway W., Yu C.-H., Pappu R.V., and Needleman D.J.. 2018. Measuring NDC80 binding reveals the molecular basis of tension-dependent kinetochore-microtubule attachments. eLife. 7:e36392 10.7554/eLife.36392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev A.V., Sundin L.J.R., DeLuca K.F., Grishchuk E.L., and DeLuca J.G.. 2014. Accurate phosphoregulation of kinetochore-microtubule affinity requires unconstrained molecular interactions. J. Cell Biol. 206:45–59. 10.1083/jcb.201312107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev A.V., Mick J.E., Maslennikov E., Nikashin B., DeLuca J.G., and Grishchuk E.L.. 2015. Multisite phosphorylation of the NDC80 complex gradually tunes its microtubule-binding affinity. Mol. Biol. Cell. 26:1829–1844. 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.