Abstract

Background

Monocytes play an important role in immune and inflammatory diseases and monocyte subsets are predictors of disease in certain conditions. Expression of the chemokine receptors, CCR2 and CX3CR1 on monocyte subsets relates to their function and can be used in their characterization. Our objective was to determine whether CD14, CD16, CCR2 and CX3CR1 on monocyte subsets are potential indicators of asthma severity.

Methods

Blood samples were collected from Saudi Arabian patients with asthma and normal healthy individuals. Six-color flow-cytometry phenotypic analysis was used to identify human blood monocyte subsets, based on their expression of CD14 and CD16 following CD45 gating. Expression of CCR2 and CX3CR1 was analysed on classical (CD14++CD16−), intermediate (CD14++CD16+) and non-classical (CD14+CD16++) subsets and correlated with disease severity.

Results

We demonstrated a significant increase in percentage of total CD45-positive monocytes in the blood of patients with severe asthma, but the proportion of the individual monocyte subsets was not significantly changed when patients with mild, moderate and severe asthma were compared with healthy individuals. CD16 expression (mean fluorescence intensity, MFI) was decreased on intermediate and non-classical subsets in patients with severe asthma compared to healthy controls. CX3CR1 expression was also lower, with a lower percentage of cells expressing CX3CR1 in the non-classical CD14+CD16++ subset in all patients with asthma and this was inversely related to the percentage of cells expressing CCR2.

Conclusions

CCR2 expression on monocytes indicated a tendency toward more phagocytic monocytes in patients with asthma. The differential expression of CD16, CX3CR1 and CCR2 on monocyte subsets in peripheral blood indicates modulation of the inflammatory response and suggests a role for monocytes in asthma pathogenesis.

Keywords: Saudi Arabia, Chemokine receptor, Flow cytometry, CD14, Biomarker

Background

Bronchial asthma, a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by reversible airway obstruction and hyperresponsiveness [1], is one of the commonest chronic disorders in the world [2]. Its prevalence and symptoms vary in different geographical locations and it affects over two million people in Saudi Arabia. Although therapeutic options have improved, there are still unnecessary fatalities and there is a clear need to improve treatment strategies and define better biomarkers to identify patients at risk.

Allergic inflammation in asthma is characteristically associated with T helper (Th) cell and eosinophil infiltration in the bronchial mucosa [3]. Antigen-specific Th2 lymphocytes play a critical role in the generation of allergic inflammation through the release of cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 [4, 5], which promote the activation and survival of eosinophils. However, monocytes are also likely to play a role due to increased production of monocyte-derived cytokines and mediators involved in oxidative stress, and in determining subsequent macrophage/dendritic cell and T helper cell phenotype and function [6, 7]. To date monocytes have received little attention in asthma pathogenesis although newly recruited monocyte-derived macrophages in the airway have been shown to be linked to eosinophilic airway inflammation [8]. Decrease in eosinophil recruitment in macrophage-depleted mice is thought to be due to reduction in macrophage chemokine production leading to altered recruitment of Th2 cells [8]. As a key immune cell in the bloodstream monocytes have been used to characterise severity of inflammation in other disorders including ischemic stroke and allergic rhinitis [7, 9, 10].

Human monocytes are heterogeneous and are classified into different subsets defined by the extent of their cell surface expression of CD14 and CD16, with associated differences in function and phenotype related to the intensity of expression of these markers. The major subset, termed classical monocytes, consists of CD14highCD16negative (CD14++CD16−) monocytes, while the CD16 expressing monocytes are usually divided into a CD14highCD16low (CD14++CD16+) intermediate subset and a CD14lowCD16high (CD14+CD16++) non-classical subset [11–13]. Differential expression of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CX3CR1 is associated with these human monocyte subsets with the classical CD14++CD16− subset predominantly expressing CCR2 and the non-classical CD14+CD16++ subset showing lower CCR2 expression and expressing significantly higher CX3CR1 [14–16].

These subsets have different functions with the CD14++CD16− subset showing predominantly a phagocytic phenotype, CD14++CD16+ an inflammatory/antigen presenting phenotype and CD14+CD16++ a patrolling phenotype in blood vessels that also has ability to present antigen [17, 18]. The CD14++CD16+ and CD14+CD16++ subsets account for only 5–15% of all human monocytes, but their frequency increases significantly in certain inflammatory conditions [17, 19–21]. One study of patients with asthma in Poland showed a significant increase in the frequency of CD14++CD16+ monocytes in patients with severe asthma compared to healthy controls or patients with mild and moderate asthma [22] and it was suggested that this increase in the intermediate population might be a useful biomarker for asthma severity. However, whether this is universally applicable is unknown.

Our aims were firstly to test, in a different population, the hypothesis that increase in the percentage of intermediate monocytes is associated with severe asthma and secondly to determine whether expression of the chemokine receptors, CCR2 and CX3CR1, on monocyte subsets can act as indicators of asthma severity. We used flow cytometry to compare monocyte populations in Saudi Arabian adults with asthma and healthy age matched controls and analysed data to identify any associations between subset populations and asthma severity.

Methods

Participants

The participants were all from Saudi Arabia and included 35 healthy, non-smoking adult volunteers with no history of asthma or of any respiratory disease as controls (Table 1). None of the control subjects had suffered from any febrile illness during the last 3 months or were taking any medication. Seventy-six patients routinely attending asthma clinics while in a non-attack state were studied and presented with mild asthma (22 patients), moderate asthma (32 patients) and severe asthma (22 patients) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects with asthma and healthy controls

| Healthy control | Asthma | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| N | 35 | 22 | 32 | 22 |

| Mean, age ±SD | 39 ± 12.86 | 39 ± 11.64 | 46 ± 16.1 | 52 ± 12.73 |

| Gender, F|M | 15|20 | 13|9 | 19|13 | 16|6 |

| Asthma duration, years (mean) | – | 18.33 | 16.03 | 21.48 |

| Family history, n (%) | – | 15 (68.2) | 17 (53.1) | 15 (68.2) |

| FEV% | – | 93 | 77.38 | 69.25 |

| History of smoking, n (%) | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 1 (3.1) | 0 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 0 | 3 (13.6) | 3 (9.4) | 2 (9.1) |

| SHS, n (%) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (6.25) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| ICS/LABA combined inhaler | ||||

| Budesonide/formoterol (160 µg/4.5 µg) | ||||

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 23 (84.4) | 15 (77.3) |

| n/day | 2/day | 2/day | ||

| Fluticasone/Salmeterol (125 µg/25 µg) | ||||

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 9 (28.1) | 7 (31.8) |

| n/day | 2/day | 2/day | ||

| SABA | ||||

| Salbutamol (200 µg) | ||||

| n (%) | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 3 (9.4) | 22 (100) |

| n/day | 2/day | 4/day | 2/day | |

| PRN | 21 (95.4) | 29 (90.6) | 0 | |

| Tiotropium | ||||

| Spiriva (18 µg) | ||||

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (68.2) |

| n/day | 1/day | |||

| Montelukast | ||||

| Singulair (10 µg) | ||||

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 12 (37.5) | 20 (90.9) |

| n/day, course | 1 course | 1/day | ||

| Anti-IgE | ||||

| Omalizumab (300 mg) | ||||

| n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 (86.4) |

| n/month | 1/month | |||

Data are presented in the form of numbers or percentage (%)

FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s; SHS second hand smoke; ICS inhaled corticosteroid; LABA long acting β2 agonist; SABA short acting β2 agonist; PRN as needed

Table 2.

Co-morbidities and laboratory characteristics of asthma patients

| Co-morbidities | Mild, n = 22 (%) | Moderate, n = 32 (%) | Severe, n = 22 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic rhinitis | |||

| Yes | 1 (4.5) | 14 (43.75) | 18 (81.81) |

| No | 21 (95.45) | 18 (56.25) | 4 (18.19) |

| Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 0 | 7 (21.88) | 11 (50) |

| No | 25 (78.12) | 11 (50) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| Yes | 0 | 7 (21.88) | 5 (22.73) |

| No | 25 (78.12) | 17 (77.27) | |

| Obesity | |||

| Yes | 1 (4.5) | 3 (9.38) | 4 (18.19) |

| No | 21 (95.45) | 29 (90.62) | 18 (81.81) |

| GERD | |||

| Yes | 0 | 11 (34.38) | 7 (31.82) |

| No | 21 (65.62) | 15 (68.18) | |

| Laboratory characteristics | |||

| Total IgEa | – | 32 (100) 0–100 | 8 (36.4) > 100 |

| 9 (40.9) > 300 | |||

| 5 (22.7) 500–700 | |||

| % Eosinophilb | 22 (100) 0–6 | 32 (100) 6.2–11 | 22 (100) 7.4–14 |

| # Eosinophilc | 22 (100) 0.2–0.8 | 32 (100) 9–1.23 | 22 (100) 1.1–1.5 |

| % Neutrophild | 22 (100) 40–75 | 28 (87.5) 40–75 | 20 (90.9) 40–75 |

| 2 (6.25) > 75 | 1 (4.55) > 75 | ||

| 2 (6.25) < 40 | 1 (4.55) < 40 | ||

| # Neutrophile | 22 (100) 2–7.5 | 28 (87.5) 2–7.5 | 21 (95.45) 2–7.5 |

| 2 (6.25) > 7.5 | 1 (4.55) < 2 | ||

| 2 (6.25) < 2 | |||

| % Lymphocytef | 22 (100) 20–45 | 26 (81.25) 20–45 | 18 (81.81) 20–45 |

| 1 (3.13) > 45 | 1 (4.55) > 45 | ||

| 5 (15.62) < 20 | 3 (13.64) < 20 | ||

| # Lymphocyteg | 22 (100) 1–5 | 30 (93.75) 1–5 | 20 (90.9) 1–5 |

| 2 (6.25) < 1 | 1 (4.55) > 5 | ||

| 1 (4.55) < 1 | |||

| % Monocyteh | 22 (100) 3–9 | 25 (78.13) 3–9 | 17 (77.27) 3–9 |

| 7 (21.87) > 9 | 5 (22.73) > 9 | ||

| # Monocytei | 22 (100) 0.2–0.8 | 28 (87.5) 0.2–0.8 | 21 (95.45) 0.2–0.8 |

| 4 (12.5) > 0.8 | 1 (4.55) < 0.8 | ||

Data are presented in the form of numbers or percentage (%)

n number of patients; Percentage of number of patients is shown in parentheses. GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease

“–” was not measured for mild asthma patients

aTotal IgE normal range, 0–100 Ku/l

bEosinophil percentage of leukocyte count normal range, 0–6%

cEosinophil count normal range, 0.2–0.8 × 109/l

dNeutrophil percentage normal range, 40–75

eNeutrophil count normal range, 2–7.5 × 109/l

fLymphocyte percentage normal range, 20–45

gLymphocyte count normal range, 1–5 × 109/l

hMonocyte percentage normal range, (3–9)

iMonocyte count normal range 0.2–0.8 × 109/l

Severity of asthma was classified according to the Saudi Initiative for Asthma (SINA) guidelines based on Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) criteria [23, 24]. Assessment of asthma severity was based on the treatment steps required to control symptoms and exacerbations.

Mild asthma controlled asthma at step 1 or 2 that needs reliever treatment, monotherapy of low-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), or leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA).

Moderate asthma controlled asthma where the patients are on combination of ICS/long-acting beta 2 agonist (LABA) or other alternative options at step 3.

Severe asthma severe uncontrolled asthma at presentation (step 4 or 5) where patients require treatment with combination of high-dose ICS/LABA with or without add-on treatment.

Ethical standards

All participants with asthma were selected from the respiratory outpatient clinic at King Khalid University Hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Khalid University Hospital, Ethics Committee, and signed informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Flow cytometry

Sample collection and preparation

Five ml of venous blood was withdrawn from the cubital vein into EDTA-anticoagulant, transferred to a 50 ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged for 4 min at 431×g. The supernatant was discarded and 10 ml of red blood cell lysing solution (Sigma Aldrich R7757) was added and incubated for 20 min at room temperature (RT) followed by centrifugation for 4 min at 431×g. Re-suspended cell pellets were washed twice with 15 ml of FACS buffer (phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 2% fetal bovine serum FBS) for 4 min at 431×g and re-suspended in 1 ml of FACS buffer.

Compensation, optimization and controls

Cytometer setup tracking (CST) research beads were used as a quality control for the instrument to improve the automated cytometer setup and performance. Compensation beads were used to ensure the integrity of the fluorochromes being used in the experiment before data acquisition. To optimize the fluorescence for the multi-color flow cytometric analysis, fluorescence compensation was run first for each fluorochrome being analysed.

In order to achieve consistent and reproducible results, and to minimize bleeding between the different dyes, optimization experiments were performed for surface markers (Alexa-700, BV510, BV421, Alexa-647, PE, and DAPI) prior to sample acquisition.

FMOs (fluorescence minus one) for each monoclonal antibody were prepared and run with the first batch of samples each week. An unstained cell suspension for each sample was included with each run. Appropriate isotype controls were also included (Table 3) to set up appropriate gating.

Table 3.

Fluorescently labelled antibodies for monocyte cell surface markers (all mouse anti-human antibodies except rat anti-human)

| Epitope | Conjugate | Manufacturer | Clone | Isotype | Test volume (µl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD45 | AF700 | Becton–Dickinson | HI30 | IgG1, k | 5 |

| CD14 | BV510 | Becton–Dickinson | MφP9 | IgG2b, k | 5 |

| CD16 | BV421 | Becton–Dickinson | 3G8 | IgG1, k | 3 |

| CCR2 | AF647 | Becton–Dickinson | 48607 | IgG2b | 5 |

| CX3CR1 (rat anti-human) | PE | MBL | 2A9-1 | IgG2b, k | 10 |

Cell surface staining

Aliquots of each cell suspension sample (100 µl) were incubated (30 min) at 4 °C in the dark with anti-CD45, anti-CD14, anti-CD16, anti-CD192 (CCR2) and anti-CX3CR1 fluorescently conjugated monoclonal antibodies (Table 3). Following incubation, cells were washed with 1 ml FACS buffer followed by centrifugation at 431×g for 4 min. The cell pellets were re-suspended in 500 µl of FACS buffer and 3×105 cells were acquired using LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences).

Gating strategy

First, forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) dot plots were used to identify cells from debris. An SSC/CD45 dot plot from a live gate was used to gate on CD45+cells and exclude large granulocytes. An FSC/SSC dot plot from the CD45+ expressing cells was used to tightly gate on the monocyte population as previously described by our group [25]. A CD14/CD16 dot plot was expressed from the gated monocytes to reveal the three monocyte subsets (CD14++CD16−, CD14++CD16+, and CD14+CD16++) based on their fluorescent intensity based on FMO and isotype controls. A CCR2/CX3CR1 dot plot was obtained for each monocyte subset (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Gating strategy for defining monocyte subsets. a A side scatter (SSC) versus forward side scatter (FSC) dot plot was used to identify cells from debris (P1); b a SSC/CD45 dot plot from live gate (P2) was used to gate on CD45+ cells and exclude large granulocytes; c a FSC/SSC dot plot from the CD45+ expressing cells was used to tightly gate on the monocyte population (positioned just above the lymphocytes); d a CD14/CD16 dot plot from CD14+ monocytes was arbitrarily set based on their fluorescent intensity and on FMO and isotype controls to reveal the three monocyte subsets (CD14++CD16−, CD14++CD16+, and CD14+CD16++); e the expression of CCR2 and CX3CR1 by the three monocyte subsets was set based on FMO and isotype control

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed through Graph Pad PRISM version 6 (Graph Pad software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Significance was calculated using a Holm–Sidak unpaired comparison test. Results were considered statistically significant if the p value was < 0.05. Mean percentages are given in the text ± standard error. Correlations were analysed using nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Results

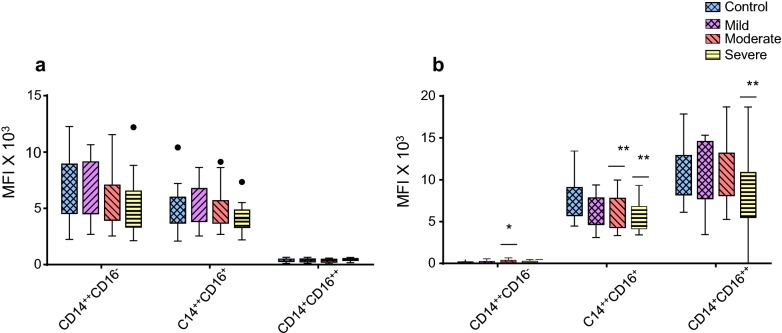

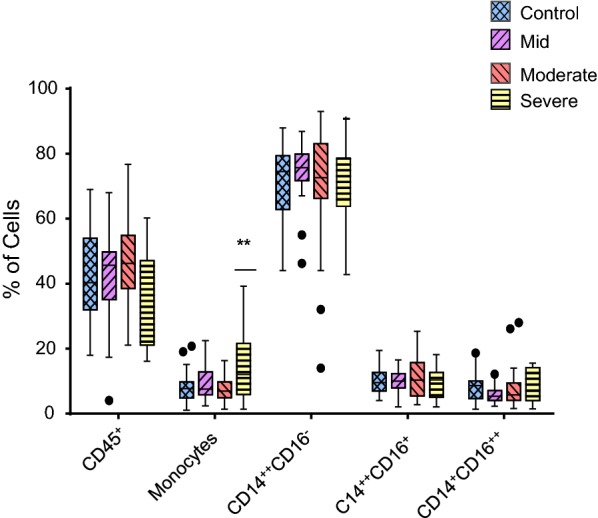

Expression of CD16 is altered on monocyte subsets in patients with asthma

The percentage of blood monocytes was significantly increased in patients with severe asthma (15 ± 2; p = 0.002) compared to healthy individuals (8%), while no significant change was observed in the patients with mild (9 ± 1) and moderate (7 ± 1) asthma (Fig. 2). The proportion of the three individual monocyte subsets showed no significant changes in patients with mild, moderate and severe asthma compared with healthy individuals (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of the percentage of CD45+ cells, total monocyte population and monocyte subsets in mild asthmatic patients (n = 22), moderate asthmatic patients (n = 32) and severe asthmatic patients (n = 22) compared to healthy control patients (n = 35). Each monocyte subset is shown as box groups where the left box indicates healthy subjects and the next boxes indicate mild, moderate and severe asthmatic patients respectively. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentile, where the top end of the whiskers indicates the largest value less than the sum of 75th percentile plus 1.5×IQR (interquartile range) and any values greater than this are considered outliers (represented by dots) and the bottom end of the whiskers indicates the lowest value greater than the 25th percentile minus 1.5×IQR and any values less than this are considered outliers. The middle line represents the median. Significance was calculated using Holm–Sidak unpaired multiple comparison test and is indicated with **(p < 0.01)

Our data showed that the expression level (MFI) of CD14 on the monocyte subsets was not significantly different in patients with mild, moderate and severe asthma compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3a). However, the expression level of CD16 on CD14++CD16+ intermediate subset monocytes was significantly lower in patients with moderate (p = 0.006) and severe (p = 0.004) asthma and there was also a significant decrease (p = 0.005) in CD16 expression on the non-classical CD14+CD16++ monocyte subset in patients with severe asthma compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3b). Collectively, these data demonstrated that while the percentage of the monocyte subsets was not significantly changed, there was differential expression of CD16 on monocyte subsets associated with asthma severity.

Fig. 3.

Comparative analysis of CD14 expression (a) and CD16 expression (b) on monocyte subsets from mild asthmatic patients (n = 22), moderate asthmatic patients (n = 32) and severe asthmatic patients (n = 22) compared to healthy control (n = 35). Each monocyte subset is shown as box groups (as defined in Fig. 2) where the left box indicates healthy subjects and the next boxes indicate mild, moderate and severe asthmatic patients respectively. Gating was performed as in Fig. 1 and significance, compared to healthy controls, was calculated using Holm–Sidak unpaired multiple comparison test and is indicated with *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01)

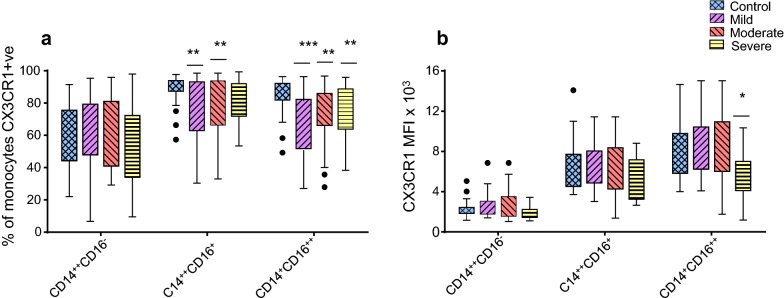

CCR2 and CX3CR1 chemokine receptor expression is altered on monocytes from patients with asthma

Expression of CCR2, is associated with phagocytic monocytes [14–17]. In the non-classical CD14+CD16++ subset, the percentage of monocytes expressing CCR2 was significantly higher in the patients with mild (24 ± 3; p < 0.0001), moderate (16 ± 2.5; p = 0.009) and severe (18 ± 2.7; p = 0.002) asthma compared to healthy (9%) controls (Fig. 4a). The percentage of monocytes expressing CCR2 in the intermediate CD14++CD16+ subset was significantly higher only in patients with mild (17 ± 4; p = 0.018) and moderate (17 ± 3; p = 0.003) asthma, not severe asthma, compared to healthy (7%) controls (Fig. 4a). The percentage of monocytes expressing CCR2 in the classical CD14++CD16− subset was not changed when patients with mild, moderate or severe asthma were compared with healthy controls (Fig. 4a). The MFI for CCR2 on all monocyte subsets showed no significant difference in patients with mild, moderate or severe asthma compared to healthy controls (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Comparative analysis of the percentage of monocytes that are CCR2 positive (a) or CCR2 expression (MFI; b) on monocyte subsets from mild asthmatic patients (n = 22), moderate asthmatic patients (n = 32) and severe asthmatic patients (n = 22) compared to healthy control patients (n = 35). Each monocyte subset is shown as box groups (as defined in Fig. 22 where the left box indicates healthy subjects and the next boxes indicate mild, moderate and severe asthmatic patients respectively. Gating was performed as in Fig. 1 and significance, compared to healthy controls, was calculated using Holm–Sidak unpaired multiple comparison test and is indicated with **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

Expression of CX3CR1 is associated with patrolling monocytes [14–17]. In the non-classical CD14+CD16++ subset, the percentage of cells expressing CX3CR1 was significantly decreased in patients with mild (67 ± 4; p < 0.0001, moderate (74 ± 3.5; p = 0.003) or severe (74 ± 3.6; p = 0.003) asthma compared to healthy controls (85%) (Fig. 5a). A significant decrease was observed in the percentage of cells expressing CX3CR1 in the intermediate CD14++CD16+ subset in patients with mild (75 ± 4; p = 0.002) and moderate (78 ± 3; p = 0.004) asthma compared to healthy (88%) controls (Fig. 5a). The percentage of monocytes expressing CX3CR1 in the classical CD14++CD16− subset was not changed when patients with mild, moderate or severe asthma were compared with healthy controls (Fig. 5a). CX3CR1 MFI was also significantly decreased (p = 0.0146) on the non-classical CD14+CD16++ subset in patients with severe asthma compared to healthy control subjects (Fig. 5b). Together, all patients with asthma demonstrated a significant (p < 0.05) inverse relationship between CCR2 (increased compared to controls) and CX3CR1 (decreased compared to controls) percentage expression in the intermediate CD14++CD16+ subset (Fig. 6a–c) although this relationship was weaker in the severely asthmatic patients (Fig. 6c). For the non-classical CD14+CD16++ subset all the patients strongly showed this inverse relationship with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient analysis showing this to be highly significant (p ≤ 0.0005, Fig. 6d–f).

Fig. 5.

Comparative analysis of the percentage of monocytes that are CX3CR1 positive (a) or CX3CR1 expression (MFI; b) on monocyte subsets from mild asthmatic patients (n = 22), moderate asthmatic patients (n = 32) and severe asthmatic patients (n = 22) compared to healthy control patients (n = 35). Each monocyte subset is shown as box groups (as defined in Fig. 2) where the left box indicates healthy subjects and the next boxes indicate mild, moderate and severe asthmatic patients respectively. Gating was performed as in Fig. 1 and significance, compared to healthy controls, was calculated using Holm–Sidak unpaired multiple comparison test and is indicated with *(p < 0.05), **(p < 0.01), ***(p < 0.001)

Fig. 6.

Correlations shown are between the percentage of monocytes that are CCR2 or CX3CR1 positive in the CD14++CD16+ monocyte subset from mild (a) moderate (b) and severe (c) asthmatic patients and in the CD14+CD16++ monocyte subset from mild (d) moderate (e) and severe (f) asthmatic patients using nonparametric Spearman rank correlation Rs

Discussion

In the presented work, we have studied monocytes from patients with asthma (all from Saudi Arabia) in terms of their CD14/CD16 defined subsets and expression of the chemokine receptors CCR2 and CX3CR1 to determine whether there are monocyte characteristics that can be linked to asthma or to the disease severity.

Proportions of monocyte subsets did not change with asthma severity

Our study showed a significant increase in the percentage of the CD45+ population of blood cells that were monocytes (CD45+/CD14+) in patients with severe asthma compared to healthy controls. The observed increase in this percentage of monocytes in patients with severe asthma may reflect their higher susceptibility to an allergenic or stress response and subsequent inflammatory reaction and release of monocytes from bone marrow or spleen [26, 27].

Despite the increase in the percentage of the CD45+ population that were monocytes, the proportions of classical, intermediate and non-classical monocyte subsets, as defined by CD14/CD16 expression, showed no significant difference in patients compared to healthy controls. While most asthma studies have focused on assessing the total monocyte numbers, one study in particular, by Moniuszko et al. [22], demonstrated a significant increase in the intermediate CD14++CD16+ monocyte percentage in patients with severe asthma compared to healthy controls or to patients with mild and moderate asthma [22]. Our study, however, provides no evidence that the proportion of this intermediate subset is increased with severe asthma. This may be a result of gating variation between the two studies; for example, our study gated on CD45+ cells initially. Perhaps more importantly, one of the main dissimilarities is that the study by Moniuszko et al. [22] involved patients from Poland whereas the patients in our study are from Saudi Arabia, where asthma may be triggered by different environmental factors. This suggests that differences may also reflect genetic or environmental factors influencing the distinct populations.

Decreased expression of CD16 on monocyte subsets in asthma

There was a significant decrease in CD16 MFI expression in patients with moderate and severe asthma in the intermediate (CD14++CD16+) monocyte subset and also in the non-classical (CD14+CD16++) subset in patients with severe asthma compared to healthy controls. Changes in CD16 MFI have not been investigated in previous asthma studies although reduction in CD16 MFI on monocytes has been reported in other patients, for example, in patients with coronary artery disease [28].

CD16+ monocytes are often expanded in inflammatory conditions such as sepsis and atherosclerosis [17, 21, 29]. It has been shown with human monocyte subsets that monocytes are released from the bone marrow in an inflammatory response as classical monocytes and differentiate sequentially in the circulation into intermediate and then non-classical monocytes [30]. This suggests that the decreased CD16+ expression we show, on intermediate and non-classical monocytes, associated with increased asthma severity may be due to the fact that monocytes are recently released from the bone marrow and have not yet acquired full CD16 expression.

CD16 on human monocytes is the Fc receptor, FcγRIIIa (CD16a) which is a low affinity IgG receptor [31] unlikely to promote an inflammatory response in asthma. However, CD16+ monocyte subsets have distinct roles in the inflammatory response, with the non-classical subset responsible for a patrolling, ‘house-keeping’ role, able to attach and crawl on endothelium and distinguish virally infected and damaged cells [32].

Chemokine receptor expression on monocyte subsets changes in patients with asthma

In addition to CD14 and CD16 surface expression, monocyte subpopulations can be further characterised based on the expression of chemokine receptors, with the phagocytic classical monocyte subset expressing high levels of CCR2 and the non-classical patrolling subset expressing low CCR2 and high CX3CR1 [14, 33, 34].

In this study, analysis of the percentage of cells expressing CCR2 and CX3CR1 in the intermediate and non-classical monocyte subsets shows a strong inverse correlation, with CCR2 increased and CX3CR1 decreased, in patients with asthma compared to healthy controls. This is consistent with our finding that monocyte subsets have decreased CD16+ associated with increased asthma severity and the suggestion that monocytes newly released from the bone marrow have not fully reduced CCR2 and acquired CX3CR1 in addition to CD16.

CCR2 and its ligands are known to be crucial for the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes, enhancing monocyte adhesion to endothelium leading to their exit into the site of inflammation [35–37]. In response to infection CCR2-positive monocytes can be recruited in large numbers and in the lung in particular this can cause widespread damage as they appear to be less likely than in the skin for example to convert to M2 macrophages associated with wound healing and repair [38].

In the non-classical (CD14+CD16++) monocyte subset, which patrols the endothelium, clearing debris and scanning for an inflammatory stimulus, CCR2 is down-regulated and CX3CR1 is highly expressed with CX3CR1 linked with patrolling ability and survival [18–20]. A general decrease in the frequency or expression of CX3CR1 on human monocytes has been shown in other conditions, for example, in patients with atopic dermatitis [39]. Thus these changes in CCR2 and CX3CR1 expression in intermediate and non-classical monocyte subsets indicate a more phagocytic phenotype and increased likelihood of endothelial damage adversely affecting asthma progression.

One unavoidable limitation is that the patients included in this study were receiving treatment to reduce inflammation (Table 1) and it is possible that the treatment will have influenced monocyte characteristics. However, despite this, significant changes in CCR2 and CX3CR1 on the intermediate and non-classical monocyte subsets were still evident however, whether they are a cause or consequence of disease remains to be established.

Conclusions

This differential expression of CD16, CX3CR1 and CCR2 on the monocyte subsets in peripheral blood indicates that monocytes may modulate the inflammatory response in asthma. The increase in CCR2 expression and decrease in CX3CR1 on CD16+ monocytes has not, to our knowledge, been described before in asthma and this association suggests a role for monocytes in asthma pathogenesis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from ‘Research Center, Center for Female Scientific and Medical Colleges, Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University. Support from the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau and External Joint Supervision Program (EJSP) is also gratefully acknowledged. Professor Graeme Devereux (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine) provided helpful discussion on asthma. Dr. Raif Yuecel and Amer Al-Mazrou provided expertise for flow cytometry and analysis.

Abbreviations

- ICS

inhaled corticosteroids

- LTRA

leukotriene receptor antagonist

- LABA

long-acting beta 2 agonist

- FMOs

fluorescence minus ones

- DCs

dendritic cells

- SINA

Saudi Initiative for Asthma

- GINA

Global Initiative for Asthma

- Th

T helper

- IL

interleukin

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed substantially in terms of design, interpretation and reporting of data, and final writing and approval of the manuscript. In addition RAR and GM were important for acquisition and analysis of data and MAH performed patient selection, reviewed the clinical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Reem AlRashoudi was funded as part of the Saudi Arabian Cultural Bureau, External Joint Supervision Program (EJSP) to do a Ph.D. degree jointly between Aberdeen University, UK and King Saud University, SA. The funding body played no part in the preparation of the data or the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from Dr. Reem AlRashoudi on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Khalid University Hospital, Ethics Committee, and signed informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Maslan J, Mims JW. What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and health care costs. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014;47:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anandan C, Nurmatov U, van Schayck O, Sheikh A. Is the prevalence of asthma declining? Systematic review of epidemiological studies. Allergy. 2010;65:152–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakagome K, Nagata M. Pathogenesis of airway inflammation in bronchial asthma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holgate ST. Pathophysiology of asthma: what has our current understanding taught us about new therapeutic approaches? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3):495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd CM, Saglani S. T cells in asthma: influences of genetics, environment, and T-cell plasticity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(5):1267–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parihar A, Eubank TD, Doseff AI. Monocytes and macrophages regulate immunity through dynamic networks of survival and cell death. J Innate Immun. 2010;2(3):204–215. doi: 10.1159/000296507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moniuszko M, Kowal K, Jeznach M, Rusak M, Dabrowska M, Bodzenta-Lukaszyk A. Phenotypic correlations between monocytes and CD4 + T cells in allergic patients. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;161(2):131–141. doi: 10.1159/000343687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YG, Jeong JJ, Nyenhuis S, Berdyshev E, Chung S, Ranjan R, Karpurapu M, Deng J, Qian F, Kelly EA, Jarjour NN, Ackerman SJ, Natarajan V, Christman JW, Park GY. Recruited alveolar macrophages, in response to airway epithelial-derived monocyte chemoattractant protein 1/CCL2, regulate airway inflammation and remodeling in allergic asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52(6):772–784. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0255OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afiune Neto A, Mansur AD, Avakian SD, Gomes EP, Ramires JA. Monocytosis is an independent risk marker for coronary artery disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2006;86(3):240–244. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X2006000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang J, Zhang L, Yu C, Yang XF, Wang H. Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomark Res. 2014;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2050-7771-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appleby LJ, Nausch N, Midzi N, Mduluza T, Allen JE, Mutapi F. Sources of heterogeneity in human monocyte subsets. Immunol Lett. 2013;152:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–964. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiesen S, Janciauskiene S, Uronen-Hansson H, Agace W, Hogerkorp CM, Spee P, Hakansson K, Grip O. CD14(hi) HLA-DRdim macrophages, with a resemblance to classical blood monocytes, dominate inflamed mucosa in Crohn’s disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:531–541. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0113021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:669–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19(1):71–82. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber C, Belge KU, von Hundelshausen P, Draude G, Steppich B, Mack M, Frankenberger M, Weber KS, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Differential chemokine receptor expression and function in human monocyte subpopulations. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67(5):699–704. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.5.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee R, Barman PK, Thatoi PK, Tripathy R, Das BK, Ravindran B. Non-classical monocytes display inflammatory features: validation in sepsis and systemic lupus erythematous. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13886. doi: 10.1038/srep13886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, Patey N, Zhang SY, Senechal B, Puel A, Biswas SK, Moshous D, Picard C. Human CD14 dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33(3):375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlin LM, Stamatiades EG, Auffray C, Hanna RN, Glover L, Vizcay-Barrena G, Hedrick CC, Cook HT, Diebold S, Geissmann F. Nr4a1-dependent Ly6C low monocytes monitor endothelial cells and orchestrate their disposal. Cell. 2013;153(2):362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landsman L, Bar-On L, Zernecke A, Kim KW, Krauthgamer R, Shagdarsuren E, Lira SA, Weissman IL, Weber C, Jung S. CX3CR20 is required for monocyte homeostasis and atherogenesis by promoting cell survival. Blood. 2009;113(4):963–972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler-Heitbrock L. The CD14+CD16+blood monocytes: their role in infection and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(3):584–592. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moniuszko M, Bodzenta-Lukaszyk A, Kowal K, Lenczewska D, Dabrowska M. Enhanced frequencies of CD14++CD16+, but not CD14+CD16+, peripheral blood monocytes in severe asthmatic patients. Clin Immunol. 2009;130:338–346. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institutes of Health. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention Revision. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.NIH Publication 2014;(02-3659).

- 24.Al-Moamary MS, Alhaider SA, Idrees MM, Al Ghobain MO, Zeitouni MO, Al-Harbi AS, Yousef AA, Al-Matar H, Alorainy HS, Al-Hajjaj MS. The Saudi Initiative for Asthma-2016 update: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma in adults and children. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11(1):3. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.173196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scally C, Rudd A, Mezincescu A, Wilson H, Srivanasan J, Horgan G, Broadhurst P, Newby DE, Henning A, Dawson DK. Persistent long-term structural, functional, and metabolic changes after stress-induced (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2018;137(10):1039–1048. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hrusch CL, Tjota MY, Sperling AI. The role of dendritic cells and monocytes in the maintenance and loss of respiratory tolerance. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0494-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowal K, Møller HJ, DuBuske LM, Moestrup SK, Bodzenta-Lukaszyk A. Differential expression of monocyte CD163 in single-and dual-asthmatic responders during allergen-induced bronchoconstriction. Clin Exp Allergy. 2006;36(12):1584–1591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shantsila E, Tapp LD, Wrigley BJ, Pamukcu B, Apostolakis S, Montoro-García S, Lip GY. Monocyte subsets in coronary artery disease and their associations with markers of inflammation and fibrinolysis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;234(1):4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogacev KS, Cremers B, Zawada AM, Seiler S, Binder N, Ege P, Große-Dunker G, Heisel I, Hornof F, Jeken J. CD14++CD16+monocytes independently predict cardiovascular events: a cohort study of 951 patients referred for elective coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel AA, Zhang Y, Fullerton JN, Boelen L, Rongvaux A, Maini AA, Bigley V, Flavell RA, Gilroy DW, Asquith B. The fate and lifespan of human monocyte subsets in steady state and systemic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2017;214(7):1913–1923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruhns P, Jönsson F. Mouse and human FcR effector functions. Immunol Rev. 2015;268(1):25–51. doi: 10.1111/imr.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas G, Tacke R, Hedrick CC, Hanna RN. Nonclassical patrolling monocyte function in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(6):1306–1316. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss-Ayali D, Conrad SM, Mosser DM. Monocyte subpopulations and their differentiation patterns during infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(2):244–252. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong KL, Tai JJ-Y, Wong WC, Han H, Sem X, Yeap WH, Kourilsky P, Wong SC. Gene expression profiling reveals the defining features of the classical, intermediate, and nonclassical human monocyte subsets. Blood. 2011;118(5):e16–e31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuziel WA, Morgan SJ, Dawson TC, Griffin S, Smithies O, Ley K, Maeda N. Severe reduction in leukocyte adhesion and monocyte extravasation in mice deficient in CC chemokine receptor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94(22):12053–12058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robays LJ, Maes T, Lebecque S, Lira SA, Kuziel WA, Brusselle GG, Joos GF, Vermaelen KV. Chemokine receptor CCR36 but not CCR36 or CCR36 mediates the increase in pulmonary dendritic cells during allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178(8):5305–5311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, Mack M, Charo IF. Critical roles for CCR37 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J Clin Investig. 2007;117(4):902–909. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray PJ. Immune regulation by monocytes. Semin Immunol. 2018;35:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Echigo T, Hasegawa M, Shimada Y, Takehara K, Sato S. Expression of fractalkine and its receptor, CX 3 CR1, in atopic dermatitis: possible contribution to skin inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(5):940–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from Dr. Reem AlRashoudi on reasonable request.