Abstract

The link between age-related cellular changes within brain regions and larger scale neuronal ensemble dynamics critical for cognition has not been fully elucidated. The present study measured neuron activity within medial prefrontal cortex (PFC), perirhinal cortex (PER), and hippocampal subregion CA1 of young and aged rats by labeling expression of the immediate-early gene Arc. The proportion of cells expressing Arc was quantified at baseline and after a behavior that requires these regions. In addition, PER and CA1 projection neurons to PFC were identified with retrograde labeling. Within CA1, no age-related differences in neuronal activity were observed in the entire neuron population or within CA1 pyramidal cells that project to PFC. Although behavior was comparable across age groups, behaviorally driven Arc expression was higher in the deep layers of both PER and PFC and lower in the superficial layers of these regions. Moreover, age-related changes in activity levels were most evident within PER cells that project to PFC. These data suggest that the PER-PFC circuit is particularly vulnerable in advanced age.

Keywords: Arc, CA1, Cognition, Infralimbic cortex, Prelimbic cortex

1. Introduction

Cognitive decline associated with advanced age can reduce an individual’s quality of life. As no single neurobiological deficit can account for the wide spectrum of behavioral impairments observed in old age, it is critical to develop an understanding of how interactions among different brain regions change over the lifespan. Rats have been used to model age-related cognitive decline, showing age-related impairments in the ability to perform a range of behavioral tasks, including the hippocampal-dependent spatial Morris water maze (Gallagher et al., 1993), prefrontal cortical (PFC)–dependent working memory and set-shifting tasks (Beas et al., 2013, 2017; Bizon et al., 2012) and perirhinal cortical (PER)–dependent object recognition tasks (Burke et al., 2010, 2011; Johnson et al., 2017). In fact, the PFC and medial temporal lobe (MTL) are among the first regions vulnerable to the effects of advancing age (Morrison and Baxter, 2012; Peters, 2006; Samson and Barnes, 2013). Interestingly, when aged rats are tested on an object-place paired association (OPPA) task (see Methods section and Figure 1), which requires PFC-MTL communication (Hernandez et al., 2017; Jo and Lee, 2010a; Lee and Solivan, 2008), deficits are observed before detectable hippocampal-dependent water maze impairments (Hernandez et al., 2015). Specifically, the OPPA task tests cognitive flexibility and associative learning, as such it requires the hippocampus, PFC, and PER, as well as functional connectivity between these structures (Hernandez et al., 2017; Jo and Lee, 2010a; Lee and Solivan, 2008). Together, these data suggest that tasks requiring both PFC and MTL structures are particularly sensitive to detecting decline in advanced age.

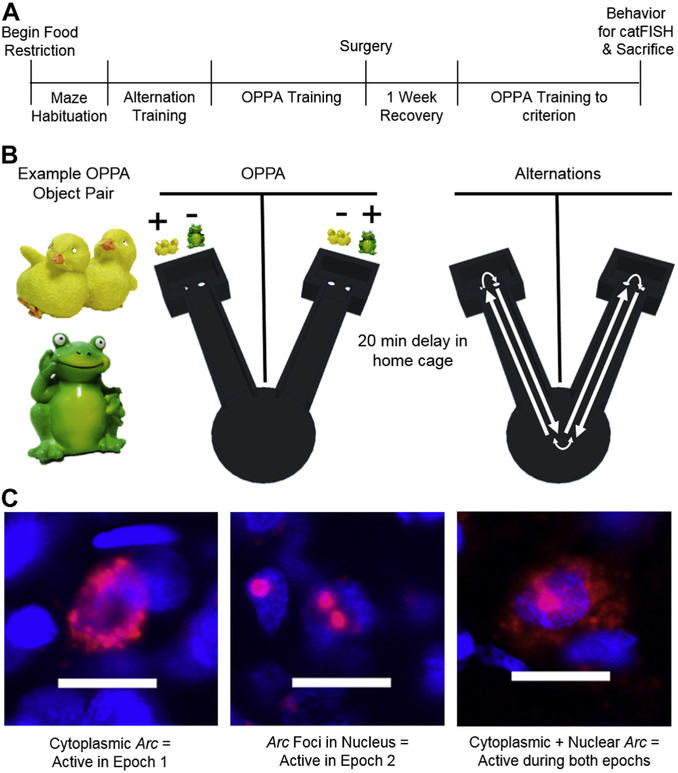

Fig. 1.

Behavioral paradigm on final testing day. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Objects used during the OPPA task are shown. During the OPPA task, rats traversed back and forth between the two arms of the testing apparatus, choosing an object in each arm. In the left arm, the chicks object was correct, but in the right arm the frog object was correct. Following a 20-minute rest in their home cages, animals then performed an alteration task in which they traversed back and forth between the two start platforms for reward, but did not perform the object discrimination component. Order of testing was counter balanced across rats. (C) Representative images of subcellular distribution of Arc within neurons. Subcellular location was used to infer which behavioral epoch a neuron was active in. Scale bar is 20 μm.

Although it is known that there are age-related impairments on behaviors that rely on the PFC and MTL, there is no neuronal cell loss within the infralimbic cortex (IL) and prelimbic cortex (PL) of the medial PFC (Stranahan et al., 2012), hippocampus (Rapp and Gallagher, 1996), or PER (Rapp et al., 2002). Rather than loss of neurons, biochemical analyses (Bañuelos et al., 2014; Beas et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2008; McQuail et al., 2015), in vivo neurophysiology (Thomé et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2011), and human imaging data (Cabeza et al., 2002; Grady, 2012; Ryan et al., 2012; Yassa et al., 2011, 2011; Zarahn et al., 2007) have suggested that age-related cognitive impairments are the result of changes in neural activity patterns that show distinct disruptions between different brain regions. In many of these studies, however, the young and older study participants were either performing differently on the behavioral tasks during which neural activity was examined or were performing a task that did not depend on the region of interest. Thus, the extent to which age-related alterations in neural activation across the hippocampus, PER, and PFC persist when subjects are performing comparably on behavioral tasks that require those regions has not been well defined.

In the present study, young and aged rats were sacrificed from their home cages, and the IL, PL, PER, and hippocampal subregion CA1 were examined for baseline expression of the activity-dependent immediate-early gene Arc. Another group of young and aged rats received the retrograde tracer, cholera toxin subunit b, into the PL and IL of medial PFC to label neurons in PER and CA1 of hippocampus that project to the PFC. These animals were trained to criterion performance of >81% correct on 2 consecutive days of testing on the OPPA task, which requires animals to use a biconditional object-in-place rule to learn the correct choice from an object pair. On the final day, rats completed two 5-minute epochs of behavior separated by a 20-minute rest. In one epoch, rats performed OPPA task, and in the other, they alternated between the 2 arms of the same maze without doing the biconditional object discrimination. Tissue was then processed for cellular compartment analysis of temporal activity with fluorescence in situ hybridization (catFISH) by labeling expression of the neuron activity-dependent immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal subregion CA1, PER, and medial PFC regions of IL and PL. The subcellular localization of Arc can be used to determine which neural ensembles across the brain were active during 2 distinct episodes of behavior. Arc is first transcribed within the nucleus of neurons 1–2 minutes after cell firing. Importantly, Arc mRNA translocate to the cytoplasm approximately 15–20 minutes after cell firing, which allows for cellular activity during 2 epochs of behavior, separated by a 20-minute rest to be represented within a single neural population (Guzowski et al., 1999). Combining this catFISH approach with retrograde labeling allowed for the examination of neural activity in anatomically defined cellular populations. Importantly, aged rats in this study were trained on the OPPA task until they performed at the same level of accuracy as young rats. Therefore, alterations in neural activity could not be attributed to overt behavioral differences.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and handling

A total of 21 young (4 months) and 19 aged (24 months) male Fisher 344 × Brown Norway F1 (FBN) Hybrid rats from the National Institute on Aging colony at Taconic Farms were used in this study. Notably, the lifespan of the FBN is greater than inbred Fisher 344 rats (Turturro et al., 1999), and many of physical issues experienced by Fischer 344 rats, including high rates of leukemia (Thomas et al., 2007), are not evident in the FBN rats until they are older than 28 months (McQuail and Nicolle, 2015). Therefore, changes in performance are likely due to cognitive decline and not age-related physical impairment. Importantly, hybrid rats of 24 months of age have been shown to have OPPA task impairments to a comparable level of the F344 rats (Hernandez et al., 2015). Thus, while the lifespan of the hybrids is longer compared with inbred F344 rats, behaviorally, FBNs 24 months and older can be considered aged.

One group of young (n = 10) studies. and aged (n = 9) rats were used for behavioral An additional 11 young and 10 aged male rats were sacrificed directly from the home cages to assess baseline expression of Arc and were not included in the behavioral assay. Each rat was housed individually and maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle, and all behavioral testing was performed in the dark phase. To encourage appetitive behavior in discrimination experiments, rats were placed on restricted feeding in which 20 ± 5 g (1.9 kcal/g) moist chow was provided daily, and drinking water was provided ad libitum. Shaping began once rats reached approximately 85% of their baseline weights. Baseline weight was considered the weight at which an animal had an optimal body condition score of 3. Throughout the period of restricted feeding, rats were weighed daily, and body condition was assessed and recorded weekly to ensure a range of 2.5–3. The body condition score was assigned based on the presence of palpable fat deposits over the lumbar vertebrae and pelvic bones (Hickman and Swan, 2010; Ullman-Culleré and Foltz, 1999). Animals with a score under 2.5 were given additional food to promote weight gain. All procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida.

2.2. Object-place paired association task

A group of young (n = 10) and aged (n = 9) rats were trained and tested on an OPPA task as previously described (Hernandez et al., 2015; Jo and Lee, 2010a,b; Lee and Solivan, 2008). The OPPA task was utilized to compare neural activity changes in young adult and aged rats because aged rats are impaired at the acquisition of this task (Hernandez et al., 2015). For the second task, we used an alternation task which does not differ across these 2 age groups. Different tasks were used to establish the behavior specificity of age-related ensemble dynamics. The experimental timelines are depicted in Fig. 1A. Rats were habituated to the testing apparatus for 10 minutes a day for 2 consecutive days, with froot loop pieces (Kellogg’s Company, Battle Creek, MI) scattered throughout the maze to encourage exploration. The maze used for all experiments was a 2-arm maze constructed out of wood and sealed with black waterproof paint (Fig. 1B, Hernandez et al., 2017, 2015). A black divider with distinctive markings on each side separated the arms, preventing visibility of the opposite arm during the experiment. The arms radiated from a starting platform that was 48.3 cm in diameter. Each arm was 84.0 cm long and had a rectangular choice platform (31.8 cm 24.1 cm) attached at the end. Each choice platform contained 2 food wells (2.5 cm in diameter) that were recessed into the maze floor by 1.0 cm and were separated by 12.8 cm. The arms and choice platforms had 5.5 cm high walls.

Following habituation, once rats were comfortable on the testing apparatus, they were trained to alternate between the left and right arms of the maze using froot loops as a reward at the end of each arm. Once a reward was retrieved from one choice platform, the choice platform in the opposite arm was baited for the next trial. This procedure continued for 32 trials per day. Owing to the increased body mass of the aged rats upon arrival, more time was required for these rats to reach their 85% restricted weight, and they, therefore, were slower to begin participation in this appetitively motivated behavior (Johnson et al., 2017), and therefore required more days of training before they were successfully alternating. Rats were continuously trained until all rats could complete 32 correct alternations in less than 20 minutes. Once rats reliably alternated 32 times in less than 20 minutes, they were trained on the OPPA biconditional association task. In this task, rats must associate an object with a particular location within the maze using an object-in-place rule (Hernandez et al., 2015; Lee and Solivan, 2008). Thus, although objects A and B are presented in both arms of the maze, object A is the correct choice in the left arm and object B is the correct choice in the right arm. Rats were randomly started in the left or right arm (counterbalanced across trials) and were required to traverse to the opposite arm to initiate the trial (see Fig. 1B). Arms were not blocked so rats were required to remember the arm they were previously in and go into the opposite arm, alternating between trials. If they failed to correctly alternate, and re-entered the arm from the previous trial, an alternation error was recorded, and no object discrimination trial was presented. Instead, the rat was redirected back to the center of the maze to continue the trial in the correct arm. Throughout raining, alternation errors were infrequent among both age groups, and no rats made an alternation error on the day of sacrifice.

In the testing platform of each arm, the rat was presented with the same 2 objects, each covering a hidden food well. The correct object for a given arm had a food reward (Froot Loops) within the food well covered by the target object, and rats made a choice by pushing aside the correct object to reveal the food reward below. After choosing an object and retrieving a food reward if correct, rats then alternated to the opposite arm where they were presented with the same 2 objects. In this arm, the other object was covering a food reward; therefore, rats had to use information about their spatial location in the maze to determine the correct object choice. If the incorrect object was chosen, all objects and rewards were removed from the maze, and the rat was not allowed to try again, until they moved to the alternate arm to initiate a new trial. Criterion performance was achieved when a rat selected the correct object a minimum of 26 of 32 trials. In addition, at least 13 correct trials must have been made in each arm. Rats were tested 32 trials/ day a minimum of 5 days a week until criterion was reached on 2 consecutive days. Following criterion performance, rats were tested at least every other day to ensure all rats maintained high levels of performance and encountered similar numbers of training days.

2.3. Retrograde tracer injection surgeries

After preliminary OPPA task training, all rats that participated in behavioral training underwent stereotactic surgery to inject the retrograde tracer cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) Alexa Fluor 594 Conjugate (catalog #C22842) into the left and right medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Under isoflurane anesthesia (1%–3%), an incision was made to expose Bregma. Small holes were drilled at +3.2 mm Anterior/Posterior and ±0.7 mm ML from Bregma. Using a glass pipette backfilled with CTB, a Nanoject II Auto-Nanoliter Injector (Drummond Scientific Company) was used to inject 112 nL of CTB at −3.6 mm ventral to the skull surface. After waiting 60 seconds, the pipette was moved up 100 mm and 56 nL of CTB was again injected, and this process was repeated for a total of 10 injections, so the final injection was given at a depth of −2.7 mm ventral to the skull surface. Thus, injected regions included IL and the full extent of PL. After the final injection, the pipette was left in place for 150 seconds, and then slowly advanced up by 0.5 mm where it was left in place for another 150 seconds allowing for the tracer to diffuse away. After the final waiting period, the pipette was slowly removed from the brain. These same injection procedures were then repeated on the contralateral side. The mPFC coordinates were determined based on a previous study showing temporary pharmacological inactivation through cannulae positioned at these coordinates produced significant impairments on the OPPA task used in these experiments (Hernandez et al., 2017). During surgery and postoperatively, the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory meloxicam (Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc., St. Joseph, MO; 1.0 mg/kg subcutaneously) was administered as an analgesic for 2 days. All animals were given 7 days to recover before resuming behavioral testing.

2.4. Experimental behavior for Arc compartmental analysis of temporal activity with fluorescence in situ hybridization (catFISH)

Thirty minutes before sacrifice, rats performed either the OPPA task or alternation task for 5 minutes each in 2 different behavioral epochs, separated by a 20-minute rest (see Fig. 1B). The alternation task required rats to ambulate back and forth between the 2 empty arms to obtain a froot loop reward. The order of task (epoch 1 OPPA-epoch 2 alternations or epoch 1 alternations-epoch 2 OPPA) was counterbalanced across rats. There were no effects of test order on Arc expression during either task (p ≥ 0.14 for both); therefore, behavioral group order was not included as a factor during further analyses. All rats then were returned to the colony room for a 20-minute rest period in their home cages before performing the other task for 5 minutes. This design enabled neurons activated during the first epoch to be differentiated from neurons activated during the second epoch based on the subcellular location of Arc mRNA. Specifically, if Arc mRNA is in the cytoplasm, then the cell fired during epoch 1. If Arc is in the nucleus at discrete foci of transcription, then the cell fired during epoch 2. Fig. 1C shows representative examples of the subcellular distribution of Arc.

2.5. Sacrifice and tissue collection

After behavioral testing, rats were sacrificed, and tissue was collected to evaluate immediate-early gene activity during the OPPA and alternation tasks. Rats were placed into a bell jar containing isoflurane-saturated cotton (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA), separated from the animal by a wire mesh shield. Animals lost righting reflex within 30 seconds of being placed within the jar and immediately euthanized by rapid decapitation. Tissue was extracted and flash frozen in 2-methyl butane (Acros Organics, NJ, USA) chilled in a bath of dry ice with 100% ethanol (~ −70°C). Two additional rats in each age group were sacrificed directly from the home cage as negative controls during the experiment to ensure that disruptions within the colony room do not lead to robust nonexperimental behaviorally induced Arc expression. Additional young (n = 9) and aged (n = 7) rats were sacrificed from the home cage on different days to measure baseline Arc expression as a function of age. Tissue was stored at −80°C until cryosectioning and processing for fluorescence in situ hybridization.

2.6. In situ hybridization

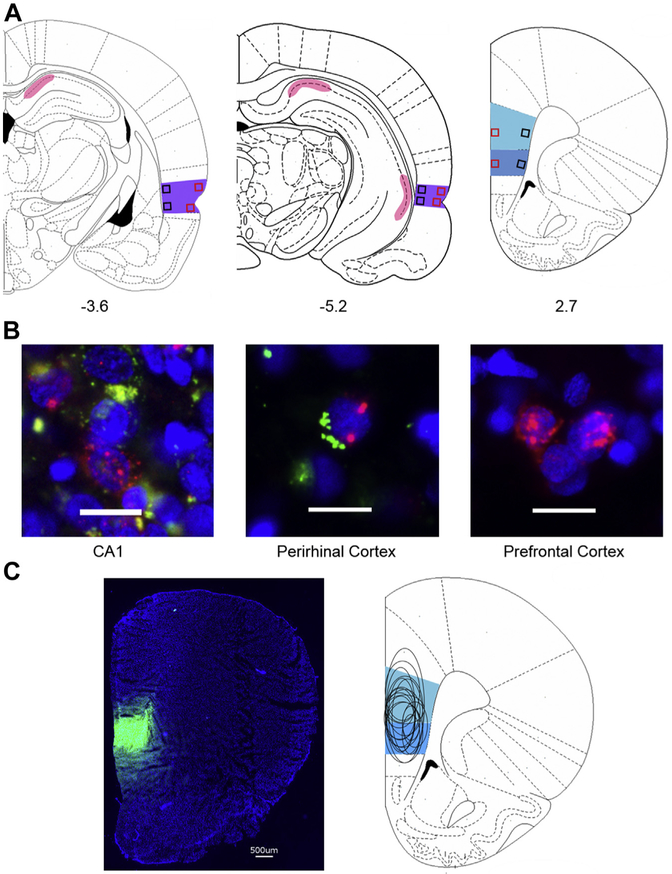

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for the immediate-early gene Arc was performed as previously described (e.g., Burke et al., 2012b; Guzowski et al., 1999). Tissue was sliced at 20-μm thickness on a cryostat (Microm HM550) and thaw-mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). In situ hybridization for Arc mRNA was performed, and z-stacks were collected by fluorescence microscopy (Keyence; Osaka, Osaka Prefecture, Japan). Briefly, a commercial transcription kit and RNA labeling mix (Ambion REF #: 11277073910, Lot #: 10030660; Austin, TX) was used to generate a digoxigenin-labeled riboprobe using a plasmid template containing a 3.0 kb Arc cDNA (Steward et al., 1998). Tissue was incubated with the probe overnight, and Arc-positive cells were detected with anti–digoxigenin-HRP conjugate (Roche Applied Science Ref #: 11207733910, Lot #: 10520200; Penzberg, Germany). Fluorescein (Fluorescein Direct FISH; PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA) was used to visualize labeled cells, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Scientific). Two images (superficial and deep) from areas 35 and 36 of the PER, 2 images (superficial and deep) from IL and PL of mPFC, and 2 images within the CA1 (dorsal and ventral) were taken for all rats, including caged controls (see Figure 2). This process was repeated on 2–3 additional sections of tissue from each rat (see Table 1 for the total number of images per region). One young rat did not have tissue analyzed because of damage, and this animal was excluded from all analyses. Analysis of variance-repeated measures (ANOVA-RM) demonstrated that neuron density differed across regions (F[7,98] = 3.06; p = 0.006), as CA1 demonstrated more densely packed cells than PER or either region of the PFC. As expected from previous data (Merrill et al., 2001; Mohammed and Santer, 2001; Pannese, 2011; Rapp and Gallagher, 1996; Rapp et al., 2002), there was no effect of age (F[1,14] = 0.02; p = 0.90) nor interaction between age and region (F[7,98] = 1.51; p = 0.17, see Table 1). Consistent with a previous report (Burke et al., 2012a), there were no significant differences between areas 36 and 35 of PER for all analyses, therefore, these subregions were combined.

Fig. 2.

(A) Location of regions imaged (PL: lightblue, IL: dark blue, CA1: pink, PER: purple). Black squares indicate deep andred squares indicate superficial areas of interest. (B) Representative images of Arc (red) and CTB (green) labeling within the different brain regions analyzed. Scale bars represent 20mm. (C) Representative image of PFC with CTB (green) injection and schematic of injection site spread.

Table 1.

Average number cells counted for each region, as well as statistical results from independent samples t-tests across age groups for behaviorally characterized and caged control animals

| PER deep | PER sup | CA1 dorsal | CA1 ventral | IL deep | IL sup | PL deep | PL sup | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of images, total | ||||||||

| Young | 72 | 65 | 33 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 32 |

| Aged | 58 | 57 | 34 | 35 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 30 |

| Young control | 38 | 37 | 22 | 23 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Aged control | 40 | 40 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Average number of cells analyzed | ||||||||

| Young | 238.60 | 215.45 | 263.40 | 278.00 | 240.40 | 239.60 | 221.80 | 240.70 |

| Aged | 176.33 | 202.44 | 312.11 | 315.11 | 209.89 | 228.11 | 214.44 | 267.00 |

| t-test (t; p) | 0.55; 0.59 | 1.47; 0.16 | 1.01; 0.33 | 0.81; 0.43 | 0.92; 0.37 | 0.26; 0.80 | 0.34; 0.74 | 0.64; 0.53 |

| Young control | 114.55 | 117.70 | 259.82 | 284.27 | 93.55 | 94.27 | 75.36 | 97.82 |

| Aged control | 139.20 | 146.45 | 226.00 | 268.00 | 162.40 | 152.00 | 148.30 | 173.10 |

| t-test (t; p) | 0.15; 0.88 | 0.25; 0.80 | 0.85; 0.41 | 0.64; 0.53 | 1.60; 0.13 | 1.58; 0.13 | 1.87; 0.08 | 1.59; 0.13 |

Key: IL, infralimbic cortex; PER, perirhinal cortex; PL, prelimbic cortex.

2.7. Arc catFISH and CTB quantification

After FISH, z-stacks were taken at increments of 1 mm and the percentage and subcellular location of Arc-positive cells was determined by experimenters blind to age and order of behavioral tasks using ImageJ software with a custom written plugin for identifying and classifying cells. Nuclei that were not cutoff by the edges of the tissue and only those cells that were visible within the median 20% of the optical planes were included for counting. All nuclei were counted with the Arc channel off, as to not bias the counter. When the total number of cells in the z-stack were identified, the Arc and CTB channels were turned on to classify cells as positive for nuclear Arc, cytoplasmic Arc, both nuclear and cytoplasmic Arc, or negative for Arc (see Fig. 1C) and/or positive for CTB. A cell was counted as Arc nuclear positive if 1 or 2 fluorescently labeled foci could be detected above threshold anywhere within the nucleus on at least 4 consecutive planes. A cell was counted as Arc cytoplasmic positive if fluorescent labeling could be detected above background surrounding at least 1/3 of the nucleus on 2 adjacent planes. Cells meeting both of these criteria were counted as Arc nuclear and cytoplasmic positive. Cells were considered to be CTB+ if at least 1/3 of the nucleus was surrounded by labeling on at least 2 adjacent planes.

Images from the PFC (rats: n = 5 young; n = 8 aged), PER (rats: n = 7 young; n = 6 aged), and CA1 (rats: n = 8 young; n = 6 aged) were obtained from animals sacrificed directly from their home cages to assess baseline Arc expression. Images were collected from superficial and deep layers of the PL and IL subregions of the medial PFC (see Fig. 2), superficial and deep layers of areas 35 and 36 of the PER, and from dorsal intermediate and ventral distal CA1 (see Fig. 2A). All cell counts were averaged per rat. Although the sample sizes differed between young and aged rats for the different regions of interest, there were no significant differences in the total number of images or average number of cells counted between the 2 age groups (see Table 1 for summary).

Images from PFC, PER, and CA1 were taken from the same regions as the caged control tissue described previously (see Fig. 2). An ANOVA examining any potential effects of age on cell numbers included in the analyses indicated that there were no significant effects of age (F[1,17] = 0.12; p = 0.73) or interaction between age and brain region (F[7,112] = 0.92; p = 0.49). Moreover, within individual brain regions, t-tests indicated that there were no significant differences in the number of cells or number of images examined between young and aged rats (p ≥ 0.07 for all; see Table 1 for individual statistics).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Neural activation during the OPPA and alternation tasks was examined using the percentage of cells positive for cytoplasmic and/or nuclear Arc expression. A mean percentage of cells was calculated for each rat for each brain region and condition, so that all statistics were based on the number of animals for sample size, rather than images or cells. This avoids the caveat of inflating statistical power and having different dependent variables correlate with each other, which can be the case in nested experimental designs (Aarts et al., 2014). Critically, the order of behavior was counterbalanced across rats, with equal numbers in both age groups, such that cytoplasmic staining corresponded to OPPA task behavior and nuclear staining corresponded with alternation behavior for half of the rats and vice versa for the others. Thus, all plots showing mean percentage of Arc-positive cells are in reference to the task and not the epoch. Notably, as mentioned previously, task order did not have a significant impact on neuron activity levels.

Potential effects of age and brain region on the percentage of cells expressing Arc during the different behaviors (OPPA versus alternation) were examined with factorial ANOVAs. For the principal component analyses, statistics were calculated from Z-scores that were determined separately for each age group. This minimizes the chances of finding a spurious correlation due to age differences rather than a relationship between the 2 variables of interest. All analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), v.25, software. Statistical significance was considered at p values less than 0.05. Principal components with an eigenvalue ≥1.0 were considered meaningful, and factor loadings ≥0.50 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral performance

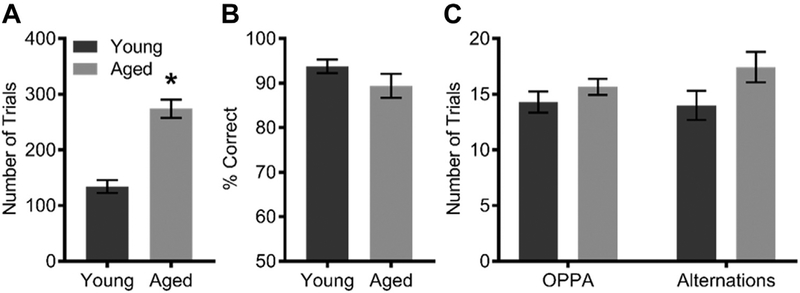

The OPPA task was used to compare neural activity changes in young adult and aged rats because aged rats are impaired at the acquisition of this task (Hernandez et al., 2015). For the second task, we used an alternation task which does not differ across these 2 age groups. Different tasks were used to establish the behavior specificity of age-related ensemble dynamics. During OPPA task acquisition, aged rats made significantly more incorrect trials before reaching a criterion performance (≥26/32 trials on 2 consecutive days) than young rats (F[3,15] = 40.47; p < 0.01; Fig. 3A). Young rats took 11.6 ± 2.93 days before reaching criterion, whereas aged rats took 20.64 ± 4.27 days. After criterion performance, rats were trained 3 days per week to maintain performance. On the final day of OPPA task performance, from which Arc expression data were obtained, there was no significant main effect of age (F[1,17] = 3.38; p = 0.08; Fig. 3B) on the percentage of correct object choices. Although there was a tendency for young rats to get more trials correct compared with the aged rats (93.90% versus 88.20%), both groups were performing well above the criterion indicating that young and aged rats were showing the OPPA behavior. For the alternation task, no animals made an alternation error on the final day of testing (data not shown). In addition, there were no differences between young and aged rats in the number of trials completed on the OPPA task (F[1,17] = 1.27; p = 0.28; Fig. 3C) or on the alternation task (F[1,17] = 3.30; p = 0.09) on the final day of testing. Thus, it can be inferred that any age-related differences in neuron activity are due to altered circuit dynamics rather than overt differences in behavioral performance.

Fig. 3.

OPPAand alternation task performance. (A) During OPPA task acquisition, aged rats made significantly more incorrect trials before reaching stable criterion performance (p < 0.01). (B) Behavioral performance and (C) number of trials performed across age groups did not differ on the final day of the task. All values represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) and * indicates p value ≤0.05 across age groups.

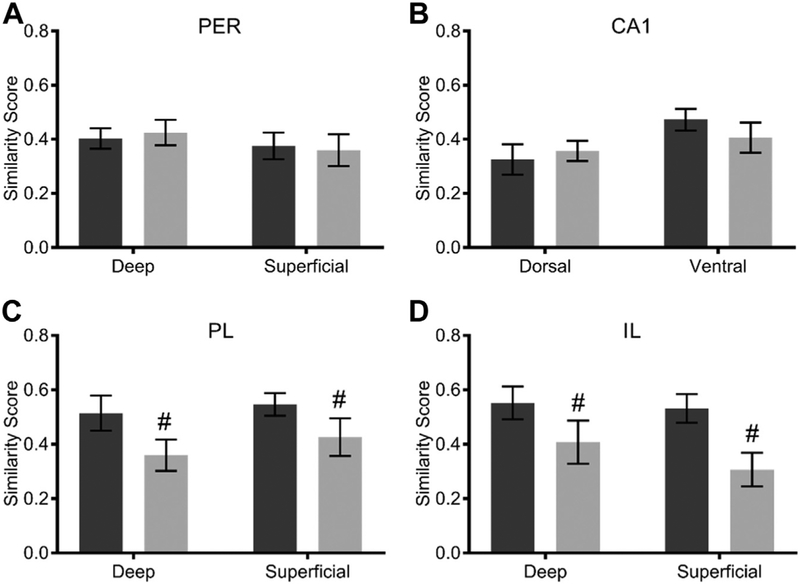

3.2. Baseline Arc expression in caged control rats

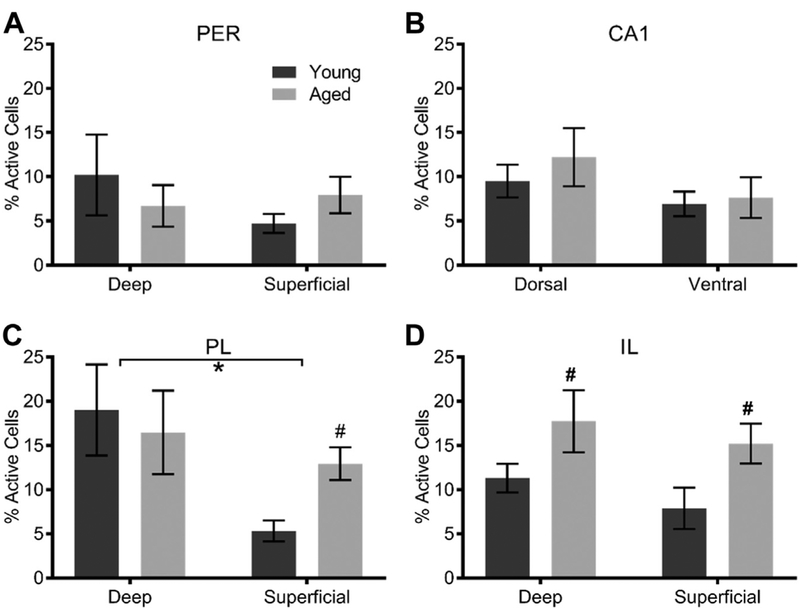

The baseline levels of Arc expression in rats sacrificed directly from the home cage were compared between young and aged rats and across brain regions with factorial ANOVA and are summarized in Fig. 4. While the main effect of age did not significantly affect the percentage of cells that were positive for Arc, there was a trend for aged rats to have a higher percentage of cells that expressed Arc within the home cage (F[15,86] = 3.34; p = 0.07). The main effect of region, however, did reach statistical significance (F[15,86] = 3.26; p = 0.004). Furthermore, there was no significant interaction between age and region (F[15,86] = 1.01; p = 0.43). Post hoc comparisons revealed that there were significantly more cells that expressed Arc in the deep layers of PL relative to ventral CA1 and superficial PER (p < 0.02 for both comparisons, Tukey). In addition, there was a trend toward more Arc-positive cells in the deep layers of PL relative to deep layers of PER (p = 0.065; Tukey). Moreover, there was an additional trend toward more cells expressing Arc in the deep layers of IL than the superficial layers of PER (p = 0.068). There were no other statistically significant differences in baseline expression across all other regions examined (p > 0.12 for all comparisons). These data suggest that medial PFC regions tend to have a higher percentage of cells that express Arc when animals are in the home cage compared with ventral CA1 and PER. Importantly, the percentage of cells expressing Arc within CA1 and PER during baseline, home cage conditions was comparable to what has been reported in other studies (Burke et al., 2005; Burke et al., 2012b; Hartzell et al., 2013; Penner et al., 2011). Thus, it is unlikely that an exogenous salient event occurred before sacrifice that increased medial PFC activity, as this would have been associated with elevated Arc-positive cells in both CA1 and PER, which was not observed.

Fig. 4.

Baseline percentage of cells expressing Arc in young and aged caged control rats for (A) perirhinal cortex (PER), (B) CA1, (C) prelimbic cortex (PL), and (D) infralimbic cortex (IL). There was a significant age-related increase in activity within the superficial layers of PL (p = 0.01) and within both layers of IL (p = 0.03). All values represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM), # indicates main effect of age across both layers and * indicates significant effect of layer.

Because of the significant effect of region and the trend of age impacting the percentage of cells expressing Arc, we examined each region individually. When the baseline percentage of Arc-positive cells was quantified in the caged control animals, within the PER, there was no main effect of age (F[1,20] = 0.00; p = 0.97), layer (F[1,20] = 0.57; p = 0.46) or on age by layer interaction=(F[1,20] = 1.41; p = 0.25). This is consistent with a previous report that did not find age differences in baseline expression of Arc between young and aged rats within the PER (Burke et al., 2012a). For CA1, as in previous studies (Hartzell et al., 2013; Penner et al., 2011), the percentage of Arc-positive cells at baseline did not differ by age (F[1,22] = 0.58; p = 0.46). Moreover, there was no significant difference in baseline Arc expression between dorsal and ventral CA1 (F[1,22] = 2.57; p = 0.12). Finally, there was no interaction between age and subregion (F[1,22] = 0.20; p = 0.66).

Within the PL, there was a significant main effect of layer on the percentage of Arc-positive cells (F[3,22] = 5.02; p = 0.04), with deep layers having more Arc-positive cells relative to the superficial layers. The main effect of age was not significant (F[3,22] = 0.44; p = 0.52) nor was there a significant interaction between age and layer (F[3,22] = 1.74; p = 0.20). Notably, when the deep and superficial layers of PL were examined independently, aged rats had significantly more Arc-positive cells in superficial layers compared with young rats (t = 2.98; p = 0.01). Within IL, there was a significant main effect of age on the percentage of Arc-positive cells (F[3,22] = 5.67; p = 0.03), with aged animals having higher baseline expression. The effect of layer, however, did not reach significance (F[3,22] = 1.06; p = 0.31). Furthermore, the effects of age and layer did not significantly interact (F[3,22] = 0.03; p = 0.88), indicating that baseline activity of IL neurons was elevated with age in both deep and superficial layers. Together, these data suggest that medial PFC activity is elevated in aged animals in the absence of significant cognitive demand.

3.3. Behaviorally induced Arc expression relative to baseline activation

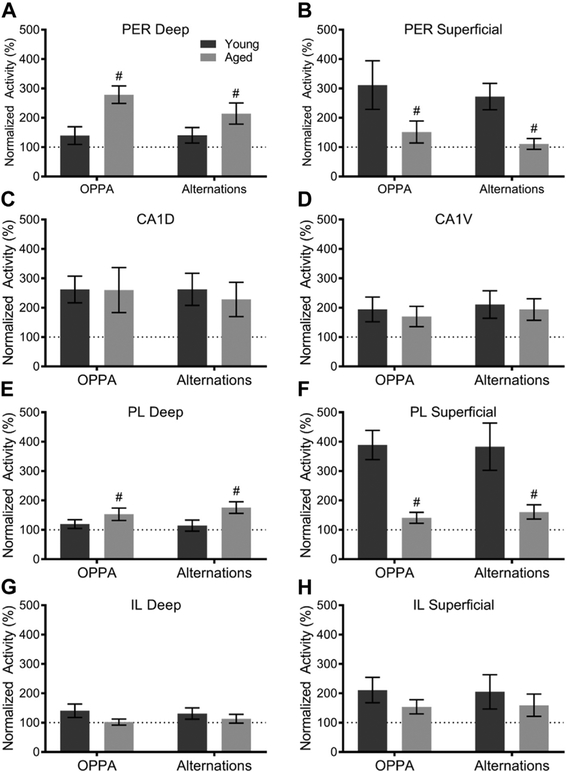

Because aged rats showed elevated proportions of cells that were positive for Arc expression within the home cage in medial PFC, Arc expression was normalized relative to caged control rats as has been done in previous studies (Fletcher et al., 2014; Tomás Pereira et al., 2015). Specifically, the percentage of cells active during a single behavioral epoch was either divided by the percentage of cells positive for cytoplasm at baseline (for behavior that occurred in epoch 1) or cells positive for foci at baseline (for behavior that occurred in epoch 2). For the raw data not normalized to baseline, see Supplemental Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Fig. 5 shows the average population activity normalized to baseline levels for the different brain regions examined in young and aged rats, with 100% being equivalent to what was observed in the home-caged controls. ANOVA-RM on the normalized percentage of Arc-positive cells comparing the OPPA and alternation tasks with the between-subjects factors of age and region did not show a main effect of task (F[1,136] = 0.00; p = 0.98). Task also did not significantly interact with region (F[1,136] = 0.44; p = 0.88) or with age (F[1,136] = 0.23; p = 0.63). There was, however, a significant main effect of region (F[1,136] = 9.10; p = 0.00) and a significant main effect of age (F[1,136] = 6.50; p = 0.01). Furthermore, the interaction between age and region also reached significance (F[1,136] = 5.64; p = 0.00).

Fig. 5.

Percentof behaviorally induced Arc positive cells normalized to caged control levels within (A, B) deep and superficial layers of the perirhinal cortex (PER), (C, D) dorsal and ventral CA1, (E, F) deep and superficial layers of the prelimbic cortex (PL), and (G, H) deep and superficial layers of the infralimbic cortex (IL). There is a significant age-related increase in Arc activity within deep layers of both the PER and PL (p ≤ 0.04 for both) and a significant age-related increase in Arc activity within the superficial layers of both the PER and PL (p ≤ 0.1 for both). All values represent the mean ± the standard error ofthe mean (SEM) and # symbol indicates main effect of age across both tasks.

Post hoc comparisons revealed that Arc expression relative to baseline was significantly higher in superficial layers of PER compared with superficial and deep layers of IL, ventral CA1, and deep layers of PL (p < 0.03 for all comparisons; Tukey). Moreover, Arc expression was significantly more elevated in neurons in the deep layers of PER compared with superficial and deep layers of IL and deep layers of PL (p ≤ 0.02 for all comparisons; Tukey). There were also significantly more cells expressing Arc, compared with baseline, within dorsal CA1 compared with deep layers of PL and IL (p < 0.01 for all comparisons; Tukey). Finally, behaviorally induced Arc expression relative to baseline was significantly higher within the superficial layers of PL than in the deep layers of PL and IL (p < 0.01 for all comparisons; Tukey).

Because of the main effect of region, each region was examined individually for age effects. There was a significant increase in Arc activity with age within the deep layers of the PER and PL (p ≤ 0.04 for both). There was a significant decrease in the extent to which behavior elevated Arc activity with age within the superficial layers of the PER and PL (p ≤ 0.01 for both). Together these data indicate that deep layers of the PER and PL are robustly engaged by behavior compared with baseline levels in aged rats, even to a greater degree than observed in young animals. In contrast, superficial layers of PER and PL show age-related reductions in recruitment of active cells during behavior. The dissociable effects of advanced age on the different layers could reflect the distinct connectivity patterns between deep and superficial layers. There were no other significant effects of age, task, or interactions between age and task (see Table 2 for complete statistical summary).

Table 2.

Comparison of normalized Arc activity across tasks for each region

| Region | Task (F; p) | Age (F; p) | Task × age (F; p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PER deep | 1.58; 0.22 | 9.18; 0.008* | 1.66; 0.22 |

| PER sup | 0.58; 0.46 | 8.62; 0.009* | 0.00: 0.99 |

| CA1D | 0.05; 0.83 | 0.02; 0.89 | 0.05; 0.83 |

| CA1V | 0.98; 0.34 | 0.002; 0.97 | 0.24; 0.63 |

| IL deep | 0.00; 1.00 | 3.10; 1.00 | 0.43; 0.52 |

| IL sup | 0.23; 0.64 | 1.19; 0.29 | 0.58; 0.46 |

| PL deep | 0.20; 0.66 | 4.71; 0.04* | 0.57; 0.46 |

| PL sup | 0.06; 0.81 | 16.04; 0.001* | 0.16; 0.70 |

Key: IL, infralimbic cortex; PER, perirhinal cortex; PL, prelimbic cortex.

Indicates p < 0.05.

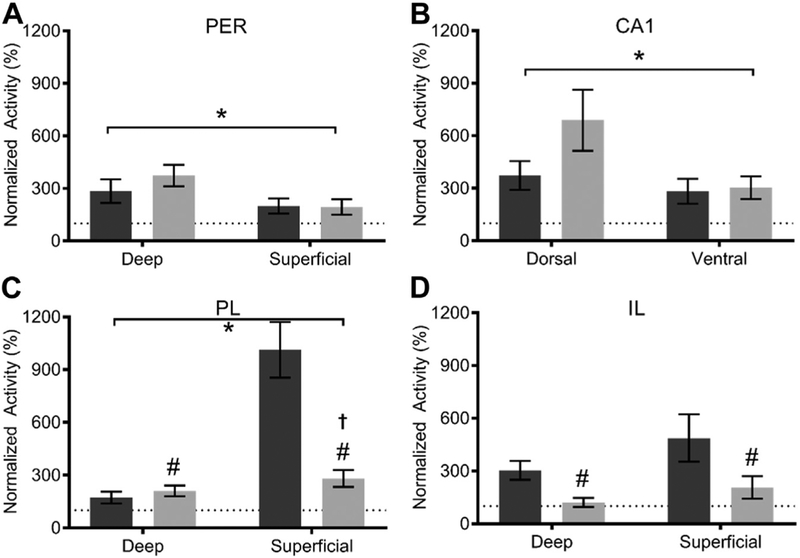

3.4. Neuronal population overlap across tasks with age

A powerful aspect of the Arc catFISH approach is that it allows one to determine the extent to which neuronal populations engaged during 2 different experiences orthogonalize. Fig. 6 summarizes the mean proportion of cells with both cytoplasmic and nuclear foci labeling normalized to baseline expression. This represents the neurons that are activated across both tasks, above what would be seen by chance from the home cage. A factorial ANOVA comparing the proportion of cells active during both epochs of behavior across regions and age groups showed a main effect of age (F[1,136] = 4.68; p = 0.03), region (F[1,136] = 7.52; p < 0.001), and a significant interaction between age and region (F[1,136] = 6.75; p < 0.001).

Fig. 6.

Proportion of cells with both cytoplasmic and nuclear foci labeling for Arc expression with (A) perirhinal cortex (PER), (B) CA1, (C) prelimbic cortex (PL), and (D) infralimbic cortex (IL). There is a significant decrease in expression within the IL and PL (p < 0.001 for both) with age. There is also a significant difference across layers/subregions within PER, CA1 and PL (p ≤ 0.03 for all) and a significant interaction between age and layer within PL (p < 0.001). All values represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM), * indicate main effect of layer, # indicates main effect of age across both layers and † indicates interaction between age and layer.

When the effects of age and layer on population overlap across tasks were examined for each brain region, there was a significant decrease in the proportion of cells active during both epochs of behavior in aged relative to young rats within PL and IL (p ≤ 0.001 for both). In PER, there was a significant effect of layer (F[1,34] = 5.63; p = 0.02) with more overlap being observed in deep relative to superficial layers, as in previous reports (Burke et al., 2005; Takehara-Nishiuchi et al., 2013). Within PL, there was also a significant effect of layer (F[1,34] = 25.80; p < 0.001) but in the opposite direction with cells in superficial layers showing greater population overlap across tasks. This was particularly evident in the young rats such that there was a significant interaction between age and layer (F[1,34] = 18.40; p < 0.001). Together, these data indicate reduced population overlap within the PFC of aged rats. Within CA1, there was significantly more population overlap across tasks in the dorsal compared with the ventral region (F[1,34] = 5.13; p = 0.03). All other effects and interactions were nonsignificant (p > 0.05). For a summary of statistical results, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Statistical summary of the mean proportion of cells with both cytoplasmic and nuclear foci labeling normalized to baseline expression across subregions and age groups

| Region | Age (F; p) | Layer/region (F; p) | Age × layer (F; p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PER | 0.56; 0.46 | 5.63; 0.02* | 0.72; 0.40 |

| CA1 | 2.55; 0.12 | 5.13; 0.03* | 1.97; 0.17 |

| IL | 7.78; 0.009* | 2.59; 0.12 | 0.35; 0.56 |

| PL | 14.96; 0.00* | 25.80; 0.00* | 18.40; 0.00* |

Key: IL, infralimbic cortex; PER, perirhinal cortex; PL, prelimbic cortex.

Indicates p < 0.05.

As population overlap can be affected by differences in overall activity levels, similarity scores can be calculated to control for differences in activity between regions (Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004). The similarity scores between the OPPA and alternation tasks were therefore calculated as:

where pB is the proportion of cells active during both epochs and pE1 and pE2 are the proportion of cells active during epochs 1 and 2, respectively. Although similarity score cannot be calculated utilizing values normalized to baseline expression, a similar effect of age on population overlap within the PFC was observed for the similarity scores. Fig. 7 summarizes the mean similarity scores for young and aged rats in the different brain regions examined. A factorial ANOVA comparing similarity scores across regions and age groups showed a main effect of age on similarity score (F[1,136] = 9.09; p = 0.003), with aged rats having a lower similarity score compared to young. There was no main effect of region (F[1,136] = 1.64; p = 0.13) nor was there an interaction between age and region (F[1,136] = 1.40; p = 0.22). When the effects of age and layer on similarity score were examined for each brain region, there was a significant decrease in similarity score in aged rats relative to young within PL and IL (p ≤ 0.03 for both). These data suggest that the neurons that show elevated activity with age in PFC drift over time such that it is not a single population of cells. Across age groups, there was a trend toward a higher similarity score for the ventral portion of CA1 than the dorsal portion (p = 0.052). All other effects and interactions were not significant (p > 0.05). For a summary of statistical results, see Table 4.

Fig. 7.

Similarity scores for Arc expression with (A) perirhinal cortex (PER), (B) CA1, (C) prelimbic cortex (PL), and (D) infralimbic cortex (IL). There is a significant decrease in similarity score across PFC with age as a whole (p < 0.03), reaching significance individually within the IL (p = 0.007) and PL (p = 0.03) regions. All values represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM), and # indicates main effect of age across both layers.

Table 4.

Statistical summary of similarity score comparisons across subregions and age groups

| Region | Age (F; p) | Layer (F; p) | Age × layer (F; p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PER | 0.006; 0.94 | 0.97; 0.33 | 0.15; 0.70 |

| CA1 | 0.13; 0.72 | 4.05; 0.052 | 0.97; 0.33 |

| IL | 8.29; 0.007* | 0.90; 0.35 | 0.38; 0.54 |

| PL | 5.40; 0.03* | 0.72; 0.40 | 0.08; 0.78 |

Key: IL, infralimbic cortex; PER, perirhinal cortex; PL, prelimbic cortex.

Indicates p < 0.05.

3.5. Relationship of neuronal activation across regions and OPPA task acquisition

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to determine if there was a relationship between Arc expression within each region and OPPA task acquisition. PCAs were performed separately for activation during OPPA task and activation during alternation task to determine whether region-specific activity clustered differently across tasks (Table 5). For the OPPA task, a PCA with a varimax rotation was performed due to the occurrence of split loadings. This analysis revealed no problematic redundancies for any task variables (problematic redundancy >0.46 across multiple components). Item communalities were moderate to high (ranging from 0.60 to 0.92) for all items except deep IL activity which was low (0.48). According to the total variance explained, a model using the top 3 components (eigenvalues >1.0), explained 73.22% of the variance in the data. The first component (eigenvalue = 2.81), which corresponded with MTL activity, accounted for 31.20% of the variance. Increased Arc activation within the deep layers of PER and within dorsal and ventral portions of CA1 positively loaded onto the first component (≥0.79). The second component (eigenvalue = 2.34), which corresponded with PFC activity, accounted for 26.02% of the variance. Increased Arc activation within superficial and deep layers of IL and superficial layers of PL positively loaded (≥0.69) and Arc activation within superficial PER negatively loaded onto the second component (−0.53). The third component (eigenvalue = 1.44), task acquisition, accounted for 16.01% of the variance, and Arc activation within deep layers of PL and superficial layers of PER positively loaded (≥0.53) and incorrect trials required to reach criterion negatively loaded (−0.76). This indicates that rats taking longer to reach criterion performance on OPPA task had increased activity in the superficial PER and deep PL during criterion performance. Whether this increased activity enabled criterion to finally be achieved, and therefore reflects an adaptive process, or is a reason for poorer performance requires further exploration. Interestingly, neural activity within the PFC and the MTL loaded onto separate components, suggesting that there is no correlation between activity levels in these 2 regions during the OPPA task.

Table 5.

Principal component analysis

| Component | OPPA | Alternations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTL activity | PFC activity | Task acquisition | MTL activity | PFC activity | Task acquisition | |

| Eigenvalue; % variance | 2.81; 31.20% | 2.34; 26.02% | 1.44; 16.01% | 3.21; 35.61% | 2.14: 23.80% | 1.46; 16.23% |

| PER deep | 0.80 | 0.91 | ||||

| PER sup | −0.53 | 0.53 | 0.74 | |||

| CA1D | 0.88 | 0.91 | ||||

| CA1V | 0.96 | 0.89 | ||||

| IL deep | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.64 | |||

| IL sup | 0.94 | 0.92 | ||||

| PL deep | 0.71 | |||||

| PL sup | 0.71 | 0.89 | ||||

| Incorrect trials | −0.76 | −0.94 | ||||

Key: IL, infralimbic cortex; MTL, medial temporal lobe; OPPA, object-place paired association; PER, perirhinal cortex; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PL, prelimbic cortex.

For the alternation task, the PCA revealed no problematic redundancies of any task variables (problematic redundancy >0.52 across multiple components). Item communalities were moderate to high (ranging from 0.68 to 0.89) for all items except deep PL activity which was low (0.30). According to the total variance explained, a model using the top 3 components (eigenvalues >1.0), explained a total of 75.64% of the variance in the variables. The first component (eigenvalue = 3.21), MTL activity, accounted for 35.61% of the variance. Similar to the activation patterns during OPPA task, increased Arc activation within superficial and deep layers of PER and within dorsal and ventral portions of CA1 positively loaded onto the MTL component (≥0.73). The second component (eigenvalue = 2.14), PFC activity, accounted for 23.80% of the variance. Increased Arc activation within superficial and deep layers of IL and superficial layers of PL positively loaded (≥0.52). The third component (eigenvalue = 1.46), task acquisition, accounted for 16.23% of the variance, and increased Arc activation within deep layers of IL positively loaded (0.64) and incorrect trials required to reach criterion negatively loaded (−0.94). Again, neural activity within the PFC and MTL loaded individually onto separate components during the alternation task.

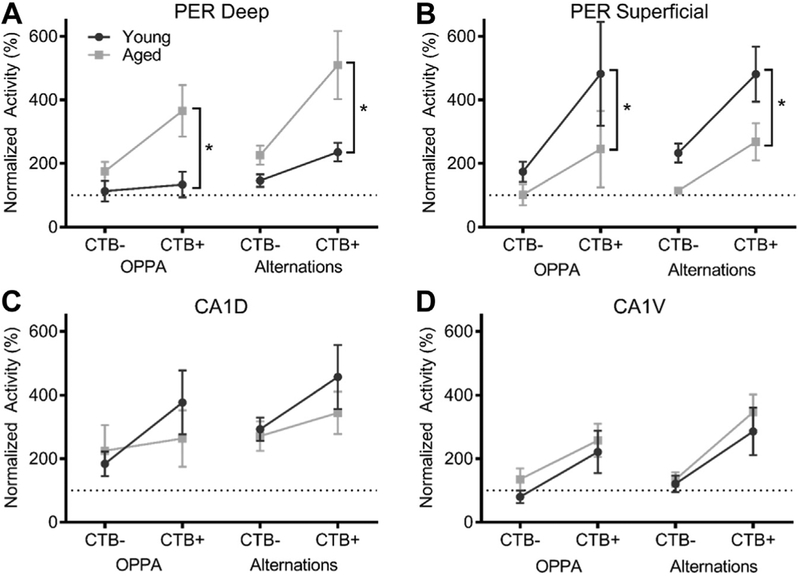

3.6. Arc expression within PFC projection neurons

Because there were significant age-related changes in neuronal activity within the medial PFC, analysis of behaviorally induced Arc expression within the PER and CA1 was restricted to neurons in these regions that projected directly to PFC, as determined by CTB labeling around the nucleus of cell bodies. To ensure that the retrograde label was similarly effective in young and aged rats, the proportion of CTB+ cells were first compared across groups (see Table 6). Although there were no significant differences in the projection neuron number in PER or ventral CA1 (p ≥ 0.11 for all), there were significantly more CTB+ cells in aged relative to young rats within dorsal CA1 (F[1,17] = 5.14; p = 0.04). Thus, any potential age-related loss in connectivity between PFC and MTL did not affect retrograde labeling with CTB. While the reason for increased CTB+ cells within dorsal CA1 with age is not known, it may reflect a compensatory mechanism in aged animals warranting further investigation.

Table 6.

Percent of CTB labeled cells

| Region | Age (F; p) |

|---|---|

| PER deep | 0.07; 0.79 |

| PER sup | 0.03; 0.88 |

| CA1D | 5.14; 0.04* |

| CA1V | 2.84; 0.11 |

Key: CTB, cholera toxin subunit B; PER, perirhinal cortex.

Indicates p < 0.05.

The proportion of Arc+ cells within PFC-projecting cells was normalized to baseline levels using the caged control data as described previously. Fig. 8 summarizes the increase in the proportion of cells expressing Arc above baseline for cells that were positive and negative for CTB. Interestingly, the increase in Arc positive cells from baseline appeared to be higher in the CTB+ cells compared with the whole population. Thus, the proportion of CTB− cells expressing Arc relative to CTB cells were compared using ANOVA-RM with age and task as between-subjects factors. For all regions, there were significantly more cells expressing Arc in the CTB+ compared with the CTB− neuron population (p < 0.01 for all comparisons; see Fig. 8 and Table 7). These data indicate that cells connected to medial PFC are more likely to be engaged during behavior. Furthermore, there was a significant age-related increase in Arc expression within the deep layers of PER (p = 0.001) and a significant age-related decrease in Arc expression within the superficial layers of PER (p = 0.02). These data suggest that the layer-specific change in activity with age observed in the entire population of cells (Fig. 5) was predominantly mediated by the PFC-projecting neurons.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of Arc activity restricted to within CTB− cells vs. activity restricted to within CTB+ projection cells demonstrated elevated signaling within CTB+ projection neurons within (A, B) deep and superficial perirhinal cortex (PER) and (C, D) dorsal and ventral CA1. All values represent the mean ± the standard error ofthe mean (SEM) and * indicates a significant effect of age across both tasks.

Table 7.

Statistical summary of the difference between all Arc+ cells with CTB+/Arc+ cells

| Region | CTB status (F; p) | CTB status × age (F; p) | CTB status × task (F; p) | Age (F; p) | Task (F; p) | Age × task (F; p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA1D | 9.15; 0.005* | 2.50; 0.12 | 0.001; 0.97 | 0.65; 0.43 | 1.52; 0.23 | 0.06; 0.81 |

| CA1V | 28.73; 0.00* | 0.05; 0.82 | 0.90; 0.35 | 1.15; 0.29 | 1.56; 0.22 | 0.01; 0.92 |

| PER deep | 27.52; 0.00* | 10.72; 0.002* | 2.12; 0.16 | 13.20; 0.001* | 3.46; 0.07 | 0.11; 0.74 |

| PER sup | 13.98; 0.00* | 1.57; 0.22 | 0.06; 0.81 | 5.63; 0.02* | 0.12; 0.73 | 0.006; 0.94 |

Key: CTB, cholera toxin subunit B; PER, perirhinal cortex.

Indicates p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The present study used the subcellular location of Arc mRNA [i.e., catFISH (Guzowski et al., 1999)] to quantify neuronal activity during 2 epochs of behavior: a biconditional OPPA task and an alternation task on the same track within the same environment. Rats were also injected with a retrograde tracer into the PL and IL regions of the mPFC to investigate age-related changes in the specific population of MTL neurons that project to PFC. These data show that when performance on the OPPA task was equivalent across age groups, there were still age- and region-specific changes in neuronal activity. Furthermore, the percentage of Arc expressing neurons in rats sacrificed directly from their home cages were used to establish a baseline of neuronal activation in young and aged rats. As in previous reports (Hartzell et al., 2013; Penner et al., 2011; Small et al., 2004; Tomás Pereira et al., 2015), there were no differences in baseline Arc expression between young and aged rats within the PER and CA1. However, there was a trend for elevated baseline expression in several PFC subregions that reached significance for the superficial layers of PL. These data suggest that the medial PFC of old animals shows enhanced activation even outside the context of a cognitive task. These data are consistent with a previous report showing delays in the spiking of inhibitory interneurons within the medial PFC that occur during both rest and behavior (Insel et al., 2012).

Although behavioral performance was equivalent on the final test day, one caveat to interpreting the current findings is that overtraining within a subset of rats could have contributed to age group differences. Notably, there was a significant difference in the number of training days required to reach equivalent performance between young and aged animals. However, because there were differences in baseline expression, it is unlikely that overtraining alone caused increased PFC engagement and altered PER activity with age. That being said, it is important to examine activation levels at different time points during task acquisition, which is not possible with the between-subjects design implemented here. In addition, there is the possibility that expectancy changes due to the absence of objects during the alternation task may cause changes in neural activity levels. Importantly, because CA1 is reported to be involved in match/mismatch expectancy signals (Duncan et al., 2012; Vinogradova, 2001), the absence of age-related changes in activity levels within this region suggests that expectancy mismatch cannot fully account for the age differences observed here. Furthermore, the age-related increase in PFC activation in animals sacrificed directly from the home cage further suggests that changes in activation levels within this region are not solely due to differences in expectancy during behavior.

The behaviorally induced expression of Arc within CA1 was not affected by age when looking at activation relative to baseline levels. These data are consistent with previous reports of CA1 activity levels remaining unaltered by age (Barnes et al., 1997; Burke et al., 2008; Hartzell et al., 2013; Penner et al., 2011; Schimanski et al., 2013; Small et al., 2004; Wilson, 2005). In the present study, the percentage of Arc-positive cells in dorsal CA1 was reduced compared with previous reports (~12% compared to ~30% in Guzowski et al., 1999; Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004). There are several potential explanations for this apparent discrepancy. First, the familiarity with the task and testing apparatus may account for lower levels of Arc expression than those observed when the environment is novel (Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004). Similarly, novel objects were placed in the arenas in Vazdarjanova and Guzowski (2004), which was not the case for our experimental setup in which rats had extensive exposure to the objects within the maze. In fact, a previous study reported that Arc expression can be reduced after extensive exposure to the same environment (Guzowski et al., 2006), as is the case here. In addition, differences in testing apparatus size may account for the decreased proportion of Arc-positive cells reported here. A greater proportion of CA1 neurons have place fields in larger compared with smaller environments (Maurer et al., 2006). During the OPPA and alternation tasks, rats traversed along a restricted path in 2 arms that totaled 168 cm. This is a substantially smaller area than the >3600 cm2 that has been used for foraging behavior in previous experiments (Guzowski et al., 1999; Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004). Both of these factors likely contributed to the lower numbers of dorsal CA1 cells that expressed Arc. Importantly, the levels of neuronal activation in ventral CA1; PER, PL, and IL reported in the present study were comparable to previous reports (Burke et al., 2012a; Chawla et al., 2018; Zelikowsky et al., 2014), indicating that methodological differences if the detection of Arc mRNA signal are not likely to account the observed differences in dorsal CA1 activation between this study and previous reports.

In both young and aged rats, there was a significant difference in activity levels between the dorsal and ventral regions of CA1. Higher levels of Arc expression within dorsal CA1 relative to more ventral areas have been reported during spatially relevant behavioral tasks (Chawla et al., 2018). Moreover, our data are in agreement with neurophysiological recordings, showing that cells in dorsal hippocampus are more likely to have a spatial receptive field than neurons in the ventral areas (Jung et al., 1994; Kjelstrup et al., 2008; Maurer et al., 2006). The data presented here indicate that this phenomenon persists with age.

While CA1 activity in the present study was not altered with age, a previous study showed that when rats were trained on a spatial task, aged behaviorally impaired rats failed to show a significant increase in CA1 Arc expression relative to baseline levels (Fletcher et al., 2014). Importantly, Fletcher and colleagues utilized labeling density to quantify Arc expression, providing a measure of overall mRNA levels rather than the proportion of cells contributing to the mRNA signal. Thus, taken together, the current data along with the work of Fletcher et al. (2014) suggest that while the number of cells that express Arc does not change with age, the quantity of Arc mRNA produced by each cell is altered. This idea is consistent with a previous report showing that individual aged neurons express less Arc mRNA relative to younger CA1 pyramidal cells (Penner et al., 2011).

Within the PER, there was a significant decrease in Arc expression in aged rats within the superficial layers, but there was age-related increase in Arc expression within the deeper layers. This effect persisted when the analysis was restricted to PFC projection cells within the PER and there is precedent for distinct patterns of neuronal activity across different cortical layers, as measured by Arc catFISH (Burke et al., 2005; Takehara-Nishiuchi et al., 2013). While both superficial and deep layers of the PER receive projections from the postrhinal cortex (POR), the deep layers project back to the POR and the superficial layers of PER more strongly project to CA1 (Agster and Burwell, 2009; Burwell et al., 1995). The decrease in activity within the superficial layers of PER suggests a decline in communication with the hippocampus during behavior, which has recently been suggested to be critical for providing sensory details to course representations of environments (Burke et al., 2018). This PER-CA1 detail network may be particularly vulnerable in advanced age (Burke et al., 2018). Conversely, the increase in activity within the deep layers of the PER suggests increased recruitment of the PER-POR circuitry with age during behavior that may reflect a compensatory mechanism for the decreased activity within the superficial layers.

Because baseline expression within the PFC was affected by age, data were normalized to caged control baseline levels of Arc expression. This represents the extent to which neuronal activity is selectively engaged by behavior across the 2 age groups. After normalization, several distinctions can be made among subregions of the PFC. First, there was a clear distinction between the patterns of behaviorally induced activity within the PL and IL regions. More neurons within PL were recruited during behavior than IL, consistent with previous reports of PL versus IL Arc activity during a foot shock paradigm (Zelikowsky et al., 2014). Whether or not the data were normalized to baseline Arc activity levels within caged control animals, however, the PL was more active than the IL during both behavioral paradigms. This could reflect differences in connectivity patterns, because the PL is more densely connected with cortical structures, whereas the IL is more densely connected with subcortical structures (Vertes, 2004). A previous study showed that young and aged rats with behavioral impairments on the hippocampal-dependent Morris water maze demonstrated increased Arc expression in response to flexibly updating choice strategy within both PL and IL. This difference in activation between dual- and single-strategy tasks was not observed in aged rats with intact spatial learning, demonstrating differential neural activity between “successful” and “unsuccessful” agers in the same task (Tomás Pereira et al., 2015). Consistent with the present study, Tomás Pereira et al. (2015) observed that overall activation in PL and IL was lower in aged compared with young rats regardless of behavioral status. In the present study, within superficial layers of PL, aged rats had fewer neurons that were engaged by the behavioral tasks. Thus, the reduced proportions of cells that activated during behavior could contribute to the overall lower levels of Arc mRNA in PFC as previously reported.

Within the PL, there were clear laminar differences for the effect of age on neural activity. While there was an age-related increase in Arc activity within the deep layers of PL, there was an age-related decrease in Arc activity within the superficial layers. These dissociable effects of age with layer were also observed in the PER and were particularly evident among the PER cells that project to the medial PFC. Together, these data suggest that between the PFC and PER, there similar effects of age that may manifest from the strong connectivity between these cortical areas.

Interestingly, there were no differences in the proportion of neurons positive for Arc mRNA between the OPPA and alternation tasks within the brain regions examined. Importantly, however, all brain regions did have distinct activity patterns across the different epochs of behavior. For CA1, in which the primary firing correlate is space (O’Keefe, 1976; O’Keefe and Dostrovsky, 1971) and activity patterns do not change dramatically between different episodes of behavior within the same environment (Thompson and Best, 1990), many neurons did not show activity across both the OPPA and alternation tasks even though both behaviors occurred on the same maze. In fact, when rats were exposed to the same environment under identical conditions across 2 different epochs, the similarity score reported in previous experiments was between 0.7 and 0.9 (Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004). This is considerably larger than the similarity score of 0.32 for dorsal CA1 observed here, indicating that the different behaviors resulted in unique populations of active neurons without changing the size of neural ensemble. A similar pattern was observed in the PER, in which it has been reported that the similarity score for active neurons in this region across 2 identical epochs is ~0.65 (Burke et al., 2012). In the current experiment, different tasks in the same environment resulted in a similarity score of 0.38 for active PER neurons further supporting that performing different behaviors in the same environment results in distinct activity patterns.

While there were no significant effects of age on population overlap across tasks in CA1 and PER as measured by the change from baseline and the similarity score, both of these measures were altered by age in the PL and IL, with aged rats showing significantly less population overlap compared with young animals. During initial event learning, PL neuron activity in young animals has been reported to be specific to events within an episode. After acquisition, however, PL activity generalizes to common features across different episodes (Morrissey et al., 2017). These data suggest that medial PFC circuits in older animals are less able to bridge common elements across distinct but overlapping episodes. An additional, but not mutually exclusive explanation, for the lower population overlap in old rats could be due to reduced trace activity in neuron firing. Medial PFC neurons in young rats have been shown to continue to fire to objects, even after they have been removed from the environment. This trace activity is in relation to where an object was located and can persist for weeks (Weible et al., 2012), which would confer overlapping activity between the OPPA and alternation tasks. Reduced population overlap in aged rats suggests that there is diminished trace activity.

The contribution of altered activity in MTL afferent input to PL and IL was examined by injecting the retrograde tracer CTB into these regions (Fig. 8). Within PER, increased activity within the deep layers and decreased activity within the superficial layers with age persisted when the analyses were restricted to CTB+ neurons. In fact, the significant interaction between age and CTB labeling in deep PER indicates that the difference in activation levels between young and aged rats can almost entirely be accounted for by those PER cells that project to PL and IL. These data suggest that neurons with long-range projections may be particularly vulnerable in advanced age.

Interestingly, in both young and aged rats, there were distinct patterns of activation between CTB− and CTB+ cell populations. Within both superficial and deep PER, there was no significant increase in Arc expression during the OPPA task within CTB− cells, but there was significant increase in Arc expression during the OPPA task within CTB+ cells. These data suggest that those cells in PER that are connected to the PFC are more likely to be engaged during behavior. Arc expression within CTB− neurons of ventral CA1 also did not increase over baseline expression. In contrast, expression within CTB+ neurons was significantly increased during both tasks, suggesting that among ventral CA1 it was the PFC-projecting neurons that were recruited during behavior. Finally, cells in dorsal CA1 exhibited higher levels of Arc activity during behavior, relative to baseline, in both CTB− and CTB+ cell populations. However, activity within CTB+ cells was significantly higher than that of CTB− cells.

Higher activity levels in MTL neurons that project to PFC is interesting in the context of aging. Brain network organization is governed by a tradeoff between topological efficiency and metabolic wiring cost (Bullmore and Sporns, 2012). Because long-distance projections between each cell or even each region would be too metabolically costly to maintain, brain networks rely on a system of densely interconnected hubs with more sparse communication between them. The higher costs associated with topological connections across multiple hubs makes them particularly vulnerable to metabolic deficiencies and cellular dysfunction. This idea is consistent with the current data in wh age-related differences in PER activity during behavior could be accounted for by those cells that project to the PFC. Furthermore, these data provide evidence that inter-regional communication supports higher cognitive function and that these brain regions are not working in isolation to perform behavioral tasks. Thus, alterations in activity within one brain region may affect cognitive outcomes by altering circuit-wide communication strategies, even with other non-dysfunctional brain regions comprising part of the circuitry.

The observed increase in PFC activity within the home cage of aged compared with young rats, as well as the increased percentage of active cells within the deep layers of PL, is particularly interesting in light of human functional magnetic resonance imaging data that show enhanced blood-oxygen-level dependent signals in the PFC of older adults (Cabeza et al., 1997; Cappell et al., 2010; Grady et al., 1999; Nagel et al., 2009). Previous studies have also shown over-recruitment of the PFC in aged compared with younger adults when cognitive demand is low, indicating that neural resources are being spent in older participants without a behavioral benefit (Cabeza et al., 2004; Morcom et al., 2003; Reuter-Lorenz and Cappell, 2008; Reuter-Lorenz and Lustig, 2005; Rypma et al., 2007; Zarahn et al., 2007). The data presented here, including increased PFC activity with age at rest, may be consistent with this idea.

In addition, increased PFC activity in old animals when cognitive load is minimal is consistent with the compensation-related utilization of neural circuits (CRUNCH) hypothesis proposed by Reuter-Lorenz et al. (2005). This theory posits that aged individuals recruit higher levels of activity during “easy” tasks to prevent behavioral deficits. As a consequence, during “difficult” tasks, this increased activity within aged individuals is not sufficient to accommodate the increased cognitive load and behavioral deficits become detectable, a phenomenon not observed in young adults (Grady, 2012; Reuter-Lorenz and Lustig, 2005). Similarly, it has been suggested that aging is associated with decreases in dynamic range or decreased ability to either upmodulate or downmodulate activity when needed (Rieck et al., 2017). Kennedy et al., 2017 found that increasing age was associated with reduced dynamic range in modulation to increasing working memory load and that greater dynamic range in both directions is associated with better performance (Kennedy et al., 2017).

In conclusion, the data presented here demonstrate age- and region-dependent alterations in neural ensemble activity during a biconditional association task and a simple alternation task. Importantly, the effect of age on activity in CA1, PER, and PFC could be dissociated. Thus, large-scale assessment of neuron activity dynamics across brain networks is imperative for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of behavioral deficits in advanced age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authorsthank Amanda Schaerer for assistance with behavioral experiments and Michael Burke for constructing the behavioral apparatus. This work was supported by the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, National Institute on Aging (R01AG049722 to SNB and F31AG058455 to ARH), and University of Florida, College of Medicine Scholars Program Awards (Leah M. Truckenbrod & Keila T. Campos).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.06.028.

References

- Aarts E, Verhage M, Veenvliet JV, Dolan CV, van der Sluis S, 2014. A solution to dependency: using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data. Nat. Neurosci 17, 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agster KL, Burwell RD, 2009. Cortical efferents of the perirhinal, postrhinal, and entorhinal cortices of the rat. Hippocampus 19, 1159–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bañuelos C, Beas BS, McQuail JA, Gilbert RJ, Frazier CJ, Setlow B, Bizon JL, 2014. Prefrontal cortical GABAergic dysfunction contributes to age-related working memory impairment. J. Neurosci 34, 3457–3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Suster MS, Shen J, McNaughton BL, 1997. Multistability of cognitive maps in the hippocampus of old rats. Nature 388, 272–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beas BS, Setlow B, Bizon JL, 2013. Distinct manifestations of executive dysfunction in aged rats. Neurobiol. Aging 34, 2164–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beas BS, McQuail JA, Banuelos C, Setlow B, Bizon JL, 2017. Prefrontal cortical GABAergic signaling and impaired behavioral flexibility in aged F344 rats. Neuroscience 345, 274–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizon JL, Foster TC, Alexander GE, Glisky EL, 2012. Characterizing cognitive aging of working memory and executive function in animal models. Front. Aging Neurosci 4, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullmore E, Sporns O, 2012. The economy of brain network organization. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 13, 336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Chawla MK, Penner MR, Crowell BE, Worley PF, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL, 2005. Differential encoding of behavior and spatial context in deep and superficial layers of the neocortex. Neuron 45, 667–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Maurer AP, Yang Z, Navratilova Z, Barnes CA, 2008. Glutamate receptor-mediated restoration of experience-dependent place field expansion plasticity in aged rats. Behav. Neurosci 122, 535–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Wallace JL, Nematollahi S, Uprety AR, Barnes CA, 2010. Pattern separation deficits may contribute to age-associated recognition impairments. Behav. Neurosci 124, 559–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Wallace JL, Hartzell AL, Nematollahi S, Plange K, Barnes CA, 2011. Age-associated deficits in pattern separation functions of the perirhinal cortex: a cross-species consensus. Behav. Neurosci 125, 836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Hartzell AL, Lister JP, Hoang LT, Barnes CA, 2012a. Layer V perirhinal cortical ensemble activity during object exploration: a comparison between young and aged rats. Hippocampus 22, 2080–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Maurer AP, Hartzell AL, Nematollahi S, Uprety A, Wallace JL, Barnes CA, 2012b. Representation of three-dimensional objects by the rat perirhinal cortex. Hippocampus 22, 2032–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Gaynor LS, Barnes CA, Bauer RM, Bizon JL, Roberson ED, Ryan L, 2018. Shared functions of perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices: implications for cognitive aging. Trends Neurosci 41, 349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD, Witter MP, Amaral DG, 1995. Perirhinal and postrhinal cortices of the rat: a review of the neuroanatomical literature and comparison with findings from the monkey brain. Hippocampus 5, 390–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Grady CL, Nyberg L, McIntosh AR, Tulving E, Kapur S, Jennings JM, Houle S, Craik FI, 1997. Age-related differences in neural activity during memory encoding and retrieval: a positron emission tomography study. J. Neurosci 17, 391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Anderson ND, Locantore JK, McIntosh AR, 2002. Aging gracefully: compensatory brain activity in high-performing older adults. Neuroimage 17, 1394–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Daselaar SM, Dolcos F, Prince SE, Budde M, Nyberg L, 2004. Task-independent and task-specific age effects on brain activity during working memory, visual attention and episodic retrieval. Cereb. Cortex 14, 364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell KA, Gmeindl L, Reuter-Lorenz PA, 2010. Age differences in prefontal recruitment during verbal working memory maintenance depend on memory load. Cortex 46, 462–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla MK, Sutherland VL, Olson K, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, 2018. Behavior-driven Arc expression is reduced in all ventral hippocampal subfields compared to CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus in rat dorsal hippocampus. Hippo-campus 28, 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan K, Ketz N, Inati SJ, Davachi L, 2012. Evidence for area CA1 as a match/ mismatch detector: a high-resolution fMRI study of the human hippocampus. Hippocampus 22, 389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BR, Hill GS, Long JM, Gallagher M, Shapiro ML, Rapp PR, 2014. A fine balance: regulation of hippocampal Arc/Arg3.1 transcription, translation and degradation in a rat model of normal cognitive aging. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 115, 58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Burwell R, Burchinal M, 1993. Severity of spatial learning impairment in aging: development of a learning index for performance in the Morris water maze. Behav. Neurosci 107, 618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady C, 2012. The cognitive neuroscience of ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 13, 491–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady CL, McIntosh AR, Rajah N, Beig S, Craik FIM, 1999. The effects of age on the neural correlates of episodic encoding. Cereb. Cortex 9, 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Worley PF, 1999. Environment-specific expression of the immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Nat. Neurosci 2, 1120–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]