Abstract

SETD1B is a component of a histone methyltransferase complex that specifically methylates Lys-4 of histone H3 (H3K4) and is responsible for the epigenetic control of chromatin structure and gene expression. De novo microdeletions encompassing this gene as well as de novo missense mutations were previously linked to syndromic intellectual disability (ID). Here, we identify a specific hypermethylation signature associated with loss of function mutations in the SETD1B gene which may be used as an epigenetic marker supporting the diagnosis of syndromic SETD1B-related diseases. We demonstrate the clinical utility of this unique epi-signature by reclassifying previously identified SETD1B VUS (variant of uncertain significance) in two patients.

Introduction

Currently, five patients have been described with a microdeletion 12q31.24 and comparable phenotypes [1–5]. The lost fragment of chromosome 12 varied in size and included multiple genes. Labonne et al. [5] identified the smallest overlapping region and proposed two histone modifiers, KDM2B and SETD1B, as the most probable candidates to be responsible for the microdeletion 12q24.31 syndrome. SETD1B encodes a SET domain-containing protein, which is a part of a histone methyltransferase complex. The key role of this complex is methylation of histone 3 on lysine 4 (H3K4), which is enriched in gene promoters and is seen to be highly correlated to gene expression [6]. KDM2B is a member of the F-protein family and encodes an enzyme that demethylates H3K36me2/3 and H3K4me3 [7]. Labonne et al. [5] showed that the genetic organization of 12q24.31 is conserved between zebrafish and humans and that KDM2B and SETD1B were expressed in the brain tissue of both zebrafish and human, suggesting evolutionary conservation of the regulation of these genes [5]. More recently, three patients with de novo point mutations in SETD1B have been described [8, 9]. Their phenotypes were similar to patients with a 12q24.31 microdeletion.

Since it has been shown that there is a strong relationship between the methylation of H3K4 and DNA methylation [10–13], we set out to determine whether the SETD1B and KDM2B aberrations can manifest with a specific DNA methylation signature. For this, a genome wide-methylation analysis was performed on DNA samples from 13 patients with either aberrations of 12q24 (including or not including KDM2B and/or SETD1B genes) or mutations in SETD1B (Table 1). This set of patients included previously described patients and additional cases identified in our laboratory or through GeneMatcher [14].

Table 1.

Cohort—molecular characteristics

| Patient no. | Patient ID | Aberrations | Pathogenicity | Inheritance | SETD1B aberrations/variations | KDM2B aberration | SETD1B DNAm signature | Batch | Previously reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1_mut | p.Arg1301* | Pathogenic | de novo | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | No; |

| 2 | 2_mut | p.Arg1902Cys | Pathogenic | de novo | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | No |

| 3 | 3_mut | p.Arg1902Cys | Pathogenic | de novo | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | Yes; Hiraide et al. [8] |

| 4 | 4_mut | p.Arg1885Trp | Pathogenic | de novo | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | Yes; Hiraide et al. [8] |

| 5 | 5_mut | p.Arg1885Trp | Pathogenic | unknown | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | No |

| 6 | 6_mut | p.Glu1692del | VUS | unknown | Yes | No | No | 1 | No |

| 7 | 7_mut | p.Glu1160Lys | VUS | de novo | Yes | No | No | 2 | No |

| 8 | 1_del12q | The minimal deletion: | VUS | Pat. inheritance | No | Yes | No | 1 | Yes; Chouery et al. [2] |

| 12q24.3(121150820-122120257) | |||||||||

| The maximal deletion: | |||||||||

| 12q24.3(121139660-122135589) | |||||||||

| 9 | 2_del12q | The minimal deletion: | Pathogenic | de novo | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 | No |

| 12q24.31(121838818-122405204) | |||||||||

| The maximal deletion: | |||||||||

| 12q24.31(121814901-122423659) | |||||||||

| 10 | 3_del12q | The minimal deletion: | Pathogenic | de novo | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes; Labonne et al. [5] |

| 12q24.31(121895610-122271171) | |||||||||

| The maximal deletion: | |||||||||

| 12q24.31(121882128-122294222) | |||||||||

| 11 | 4_del12q | The minimal deletion: | Pathogenic | de novo | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | Yes; Qiao et al. [4] |

| 12q24.31(122255880-123758046) | |||||||||

| The maximal deletion: | |||||||||

| 12q24.31(122234178-123780094) | |||||||||

| 12 | 5_del12q | The minimal deletion: | VUS | unknown | No | No | No | 2 | No |

| 12q24.31q-12q24.32(122844745-127838399) | |||||||||

| The maximal deletion: | |||||||||

| 12q24.31q-12q24.32(12:122825331-127854607) | |||||||||

| 13 | dup12q | The minimal duplication: | VUS | Mat. inheritance | No | No | No | 1 | No |

| 12q24.12(12:112169989-112313658) |

*Mutations are reported according to NM_001353345.1; Hg19

The minimal deletion/duplication within the given start and end position

The maximal deletion—without the given start and end position (between)

Results

Identification of a SETD1B-related specific methylation signature

Genomic DNA was obtained from whole blood samples (13 patients and 60 controls), and genome methylation status was analyzed using the Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip. The determination of DNAm signature based on HumanMethylation array was previously validated and described in various studies [13, 15–19].

The principal component analysis (PCA) of the data obtained showed two outliers in our cohort: a patient with a microdeletion including SETD1B and KDM2B (3_del12q; Batch1) and a healthy control (4 days old, batch 2). Estimation of the blood cell types in patient 3_del12q showed an unexpected distribution of cell types (99% of B lymphocytes). Both outliers were excluded from further group analysis. Quality control (QC) of the data, PCA analysis, and estimation of the blood cell type distribution are described in detail in the supplemental information and listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Next, a group-based differential methylation analysis was carried out, comparing the DNAm of five patients with pathogenic variants in SETD1B to that in controls (n = 59). Variants were considered pathogenic if the following was observed: (i) variants were de novo and occurred in more than one patient or (ii) variants resulted in a premature stop codon. The patients included in the group analysis were patient 1_mut (p.Arg1301*), patients 2_mut and 3_mut (p.Arg1902Cys), and patients 4_mut and 5_mut (p.Arg1885Trp).

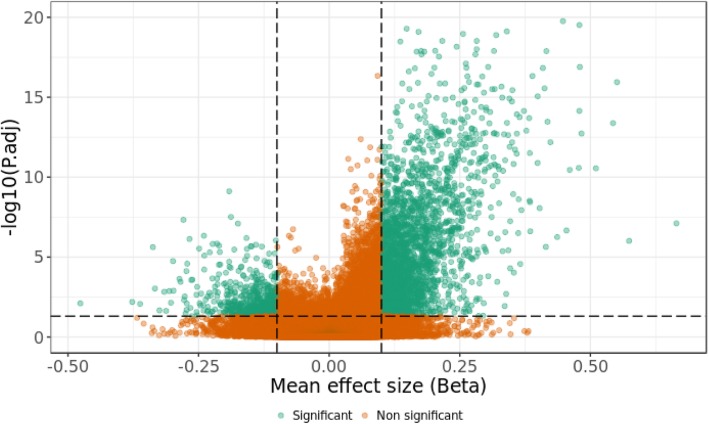

A shift of the genome-wide methylation toward hypermethylation was observed (Fig. 1), which is reflected in the selected significant differentially methylated CpGs (adj. P-value_M < 0.05, absolute beta difference > 0.1). This analysis identified 3340 significant differentially methylated CpGs, out of which more than 82% had a positive beta difference. All significant differentially methylated CpGs identified in this analysis are listed in Additional file 2: Table S2. To further calculate the probability that we would have identified that these 3340 CpGs as significant by chance, we performed an additional permutation analysis on the group labels. 99.6% of 3340 significant differentially methylated CpGs displayed P value less than or equal to 0.05. Details of this analysis are described in the additional information and listed in the Additional file 6: Table S6.

Fig. 1.

The volcano plot of the methylation difference between patients with certain pathogenic variation in SETD1B and healthy individuals (group analysis). The y-axis represents a negative log10 of adj. P-values_M; the x-axis represents the different beta values between patients and controls. Each dot on the plot represents a single CpG site. The horizontal, dotted line represents the statistical significance threshold (adj. P-values_M = 0.05). The vertical, dotted lines show the effect-size threshold (− 0.1 and 0.1). CpGs with adj. P-value_M lesser than 0.05 and an absolute beta difference higher than 0.1 are highlighted in green

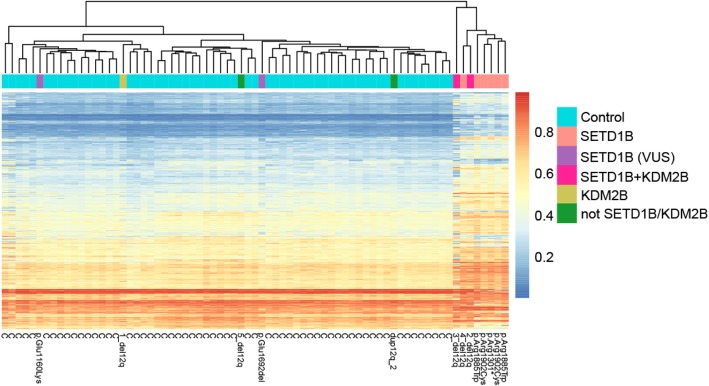

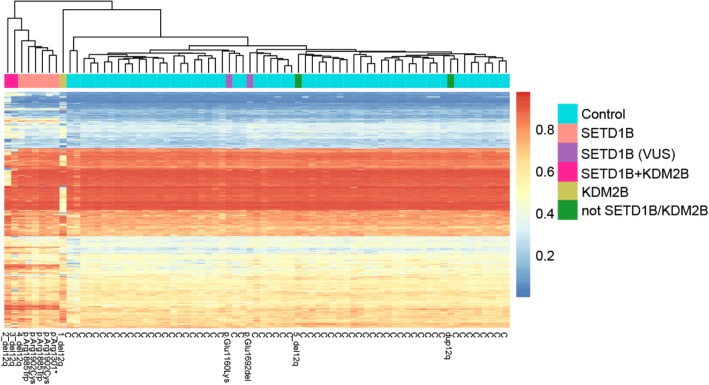

Next, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of beta values of the identified significant CpG sites (3340 CpGs) for each individual of our cohort was created; 13 patients and 60 controls (Fig. 2). Eight of the 13 patients were clustered in a separate group. All five patients with pathogenic variants in SETD1B (patients included in the “SETD1B-related” group analysis); two patients with a deletion including KDM2B and SETD1B (2_del12q, 3_del12q) and one with a deletion including only SETD1B (4_del12q) fell into this cluster. Note that although patient 3_del12q had an aberrant blood cell composition, the methylation signature was detectable in this sample. These results demonstrate the robustness of the specific DNAm of the SETD1B aberrations/variations. Despite the many variables in the cohort that may have had an impact on the DNAm (different ethnicity, different aberrations/variations, a different method of DNA isolation small sample size, batch, age, and distribution of the cell types), there is a distinct SETD1B specific methylation signature. The methylation profile of the patients with a deletion excluding SETD1B (1_del12q and 5_del12q_a), a patient that carried a duplication of the 12q region, and two patients with a variant of uncertain significance, in SETD1B (6_mut and 7_mut), did not show the SETD1B-specific signature.

Fig. 2.

SETD1B-related DNAm signature. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of 3340 CpG sites identified in the SETD1B group analysis (DNAm of patients with certain pathogenic aberration/variation in SETD1B compared to that in healthy controls). C represents controls; aberrations/variations are annotated to patients. Note that the data was obtained from two batches

Examination of the specificity of the SETD1B-related DNAm signature

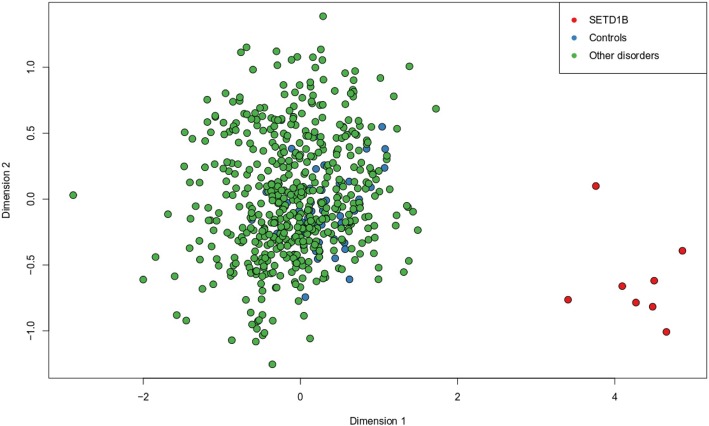

We examined whether the DNA methylation signature of SETD1B-related syndrome overlaps with that of other neurodevelopmental disorders or syndromes, which in some cases, are caused by mutations in the members of the epigenetic machinery. Using a multidimensional scaling of the methylation values across the CpGs differentially methylated in the SETD1B-related syndrome, we examined the methylation profile of a total of 502 individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of various syndromes with previously described epi-signatures including imprinting defect disorders [16, 17, 20] (Angelman syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, Silver–Russell syndrome, and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome), BAFopathies (Coffin-Siris and Nicolaides-Baraitser syndromes), Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy, Floating–Harbor syndrome, Cornelia de Lang syndrome, Claes–Jensen syndrome, ADNP syndrome, ATRX syndrome, Kabuki syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, Fragile X syndrome, trisomy 21, Williams syndrome, and Chr7 duplication syndrome (Fig. 3). All of these patients showed a DNA methylation pattern different from the SETD1B-related syndrome and were clustered with controls, indicating that the identified epi-signature is highly specific to SETD1B loss of function.

Fig. 3.

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) of 502 individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Red dots represent eight patients with SETD1B-related DNAm signature of the current study, blue dots represent controls of the current study, and green dots represent patients with other disorders

Identification of the SETD1B-related differentially methylated regions

Using the “bumphunter” R-package, four genomic regions differentially methylated between patients with pathogenic variants in SETD1B (as defined above) and controls were identified (minimum three differentially methylated CpGs in a region; family-wise error rate (Fwer) < 0.05) (Table 2). All four regions were hypermethylated in patients and located in the regulatory clusters of active promoters, enhancers, and DNAse hypersensitivity (UCSC Genome Browser on Human; GRCh37/hg19 [21]), three of which were annotated to genes (i) KLHL28, FAM179B; (ii) RUNX1; and (iii) BRD2.

Table 2.

DMRs identified in the group analysis of certain pathogenic aberrations/variants in SETD1B

| Chr | Start | End | Value | L | ClusterL | Fwer | Gene_Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr6 | 26195488 | 26195995 | 0,45 | 5 | 5 | 0,002 | |

| chr14 | 45431885 | 45432516 | 0,40 | 4 | 21 | 0,014 | KLHL28;FAM179B |

| chr21 | 36258423 | 36259797 | 0,21 | 13 | 13 | 0,02 | RUNX1 |

| chr6 | 32942063 | 32943025 | 0,26 | 11 | 128 | 0,026 | BRD2 |

Value –represents the difference between patient end controls

L– number of differentially methylated CpGs in the detected region, Cluster L– number of CpGs in the genomic cluster, Fwer– family-wise error rate

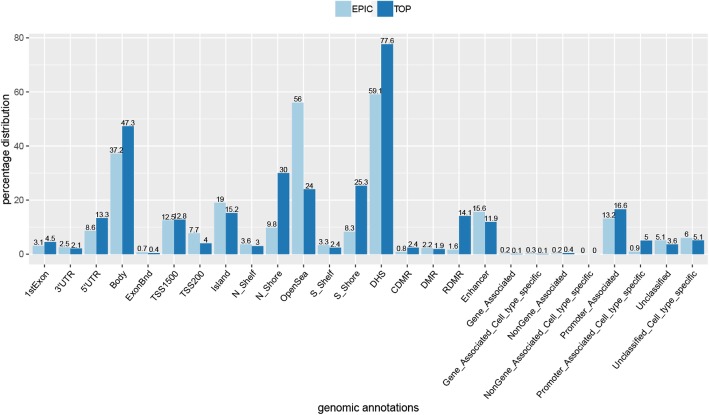

Analysis of the genomic distribution of the CpG sites in the SETD1B DNAm signature

An analysis of the genomic distribution of the CpG sites identified in the group analysis was conducted. This showed an over-representation of CpGs in the gene body, DNase hypersensitivity sites (DHS), CpG island S-shore, reprogramming differentially methylated regions (RDMR), and in promoter-associated sites (Fig. 4). These results demonstrate that the disrupted methylation related to the SETD1B function is enriched in the regulatory parts of the genome.

Fig. 4.

Genomic distribution of the significant differentially methylated CpG sites identified in group analysis according to the genomic annotations of the epic array. The light blue bars (EPIC) represent all the informative probes included in the data (777,148 CpGs) and the dark blue bars the CpGs identified in the group analysis (TOP; 3340 CpGs). The numbers on the top of the bars represent the percentage distribution of CpGs for each category. All categories are listed in the supplemental information—Infinium Methylation EPIC Manifest Column Headings®. This comparison demonstrates the enrichment in the body (between the ATG and stop codon), DHS–DNase I hypersensitivity site, RDMR–reprogramming-specific differentially methylated region, promoter-associated, and promoter-associated cell-type specific

Over-representation analysis (ORA) of CPGs in the SETD1B DNAm signature

To identify the processes involved in the development of the phenotype, ORA analysis based on gene names associated with the 3340 identified significant methylated CpGs using WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit [22] was performed. The analysis for biological processes displayed enrichment for genes with a function in chromosome organization, regulation of organelle organization, cell cycle, and regulation of cell death. ORA for molecular function demonstrates enrichment for genes with a role in the regulation of gene activity, such as RNA binding, protein domain-specific binding, regulatory region nucleic acid binding, and transcription regulatory region DNA binding. ORA for the human phenotype (top 10 highest ranked features) showed enrichment in genes related to facial and posture abnormalities. The results of ORA are summarized in Table 3. Note that ORA analysis is very general and the results should be interpreted with caution.

Table 3.

Summary of the ORA

| Gene ontology: biological processes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | C | O | E | R | pValue | FDR | |

| GO:0051276 | Chromosome organization | 1143 | 165 | 97.67 | 1.69 | 5.59E−12 | 5.08E−08 |

| GO:0033043 | Regulation of organelle organization | 1245 | 175 | 106.39 | 1.64 | 1.16E−11 | 5.26E−08 |

| GO:0007049 | Cell cycle | 1739 | 223 | 148.60 | 1.50 | 1.15E−10 | 3.48E−07 |

| GO:0006915 | Apoptotic process | 1911 | 239 | 163.30 | 1.46 | 2.52E−10 | 5.74E−07 |

| GO:0010941 | Regulation of cell death | 1648 | 210 | 140.83 | 1.49 | 7.83E−10 | 1.42E−06 |

| GO:0006325 | Chromatin organization | 741 | 112 | 63.32 | 1.77 | 1.35E−09 | 1.90E−06 |

| GO:0033554 | Cellular response to stress | 1867 | 231 | 159.54 | 1.45 | 1.47E−09 | 1.90E−06 |

| GO:0010942 | Positive regulation of cell death | 660 | 102 | 56.40 | 1.81 | 2.28E−09 | 2.60E−06 |

| GO:0010629 | Negative regulation of gene expression | 1733 | 216 | 148.09 | 1.46 | 3.00E−09 | 2.87E−06 |

| GO:0034613 | Cellular protein localization | 1815 | 224 | 155.10 | 1.44 | 3.44E−09 | 2.87E−06 |

| Gene ontology: molecular function | |||||||

| GO:0003723 | RNA binding | 1603 | 203 | 131.47 | 1.54 | 7.52E−11 | 8.28E−08 |

| GO:0019904 | Protein domain specific binding | 684 | 106 | 56.10 | 1.89 | 8.82E−11 | 8.28E−08 |

| GO:0001067 | Regulatory region nucleic acid binding | 898 | 129 | 73.65 | 1.75 | 1.39E−10 | 8.70E−08 |

| GO:0044212 | Transcription regulatory region DNA binding | 896 | 128 | 73.48 | 1.74 | 2.38E−10 | 1.12E−07 |

| GO:0043565 | Sequence-specific DNA binding | 1097 | 146 | 89.97 | 1.62 | 1.87E−09 | 7.02E−07 |

| GO:0003690 | Double-stranded DNA binding | 915 | 126 | 75.04 | 1.68 | 3.41E−09 | 1.07E−06 |

| GO:0000976 | Transcription regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding | 781 | 111 | 64.05 | 1.73 | 5.41E−09 | 1.45E−06 |

| GO:1990837 | Sequence-specific double-stranded DNA binding | 823 | 115 | 67.50 | 1.70 | 7.55E−09 | 1.77E−06 |

| GO:0000977 | RNA polymerase II regulatory region sequence-specific DNA binding | 729 | 103 | 59.79 | 1.72 | 2.69E−08 | 5.62E−06 |

| GO:0001012 | RNA polymerase II regulatory region DNA binding | 735 | 103 | 60.28 | 1.71 | 4.11E−08 | 7.72E−06 |

| Human Phenotype Ontology | |||||||

| HP:0002346 | Head tremor | 20 | 10 | 1.87 | 5.36 | 3.48E−06 | 0.016253 |

| HP:0011337 | Abnormality of mouth size | 269 | 43 | 25.09 | 1.71 | 2.13E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0004097 | Deviation of finger | 320 | 49 | 29.85 | 1.64 | 2.23E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0000311 | Round face | 73 | 17 | 6.81 | 2.50 | 2.80E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0000219 | Thin upper lip vermilion | 137 | 26 | 12.78 | 2.03 | 2.84E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0011228 | Horizontal eyebrow | 8 | 5 | 0.75 | 6.70 | 3.04E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0005306 | Capillary hemangioma | 26 | 9 | 2.43 | 3.71 | 3.59E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0001894 | Thrombocytosis | 21 | 8 | 1.96 | 4.08 | 3.63E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0100559 | Lower limb asymmetry | 21 | 8 | 1.96 | 4.08 | 3.63E−04 | 0.167774 |

| HP:0000107 | Renal cyst | 203 | 34 | 18.93 | 1.80 | 4.21E−04 | 0.167774 |

C reference genes in the category, O observed number of genes in the category, E expected number of genes in the category, R ratio of enrichment, pValue p value from hypergeometric test, FDR false discovery rate

Analysis of a KDM2B-related specific methylation signature

Only three patients in this cohort had a deletion of KDM2B (1_del12q, 2_del12q, 3_del12q), one of whom presented with a deletion excluding SETD1B (1_del12q). Furthermore, of these, patient 3_del12q was excluded from the group analysis due to the heavily disturbed blood cell-type distribution. Despite these limitations, an attempt was made to identify a KDM2B-specific signature, running the group analysis of only two patients (1_del12q, 2_del12q) compared to 59 controls. This identified 697 significant differently methylated CpG sites (adj. P-value_M < 0.05 and absolute beta difference > 0.1). Nevertheless, the unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Fig. 5) of the 697 identified CpGs did not show any specific methylation signature related to KDM2B. The two patients (1_del12q and 2_del12q) were clustered separately from each other, other patients, and healthy controls. Moreover, the SETD1B-related specific signature was still strongly marked. All significant differentially methylated CpGs identified in this analysis are listed in Additional file 3: Table S3.

Fig. 5.

Unsuperviesed hierarchical clustering of the 697 CpG sites identified in KDM2B group analysis. C–represents controls, aberrations/variations annotated to patients. The data was obtained from two batches

Identification of the KDM2B-related differentially methylated regions

The DMR analysis did not show any significant DMR (minimum of three differentially methylated CpGs in a region; Fwer < 0.05).

Clinical features

All patients with a SETD1B signature-positive methylation profile presented with an intellectual disability. Common features included language delay, epilepsy, and behavioral problems such as autism spectrum disorder and anxiety. Dysmorphisms included full cheeks, full lower lip, macroglossia, and tapering fingers. Delay in motor development was primarily present in patients with a deletion and absent in patients with a point mutation in SETD1B (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of clinical features of patients with variation/aberration within the SETD1B gene

| Specific SETD1B-related DNAm signature (this study) | Other previously reported patients (not included in this study) | Non-SETD1B DNAm signature | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | mut_1 Male 13 years Disrupted SETD1B |

mut_2 Male 16 years Disrupted SETD1B |

3_mut Male 34 years Disrupted SETD1B |

4_mut Female 12 years Disrupted SETD1B |

5_mut Male 7 years Disrupted SETD1B |

2_del12q Female 12 years Disrupted SETD1B and KDM2B |

3_del12q Male 3 years Disrupted SETD1B and KDM2B |

4_del12q Female 16 years Disrupted SETD1B |

Baple et al. [1] Female 11 years Disrupted SETD1B and KDM2B |

Palumbo et al. [3] Female 11 years Disrupted SETD1B and KDM2B |

6_mut Male 8 years VUS SETD1B |

7_mut Male 10 years VUS SETD1B |

| Growth parameters at birth | ||||||||||||

| Height | 48 cm | NA | NA | – |

47 cm (5th centile) |

52 cm (+ 0.45 SD) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Weight | 2.9 kg |

2.52 kg (2.5 SD) |

3.6 kg (+ 1.5 SD) |

3.55 kg (+ 1.4 SD) 34.5 cm (+ 1.1 SD) |

2.8 kg (9th centile) |

3.78 kg (+ 1.45 SD) |

NA | NA | 4094 g (90–95th centile) | 2650 g (5–10th centile) | 3260.2 (25–50th centile) | NA |

| Head circumference | 33 cm | NA | NA | NA |

33 cm (10th centile) |

35 cm (− 0.1 SD) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Growth parameters at last evaluation | ||||||||||||

| Height | 167.5 cm (at 30 years) | 193 cm (+ 1.45SD) | NA | NA | 1.35 m (+ 1.8 SD) | 170 cm (+ 1.2SD) (at 13) | NA | (98th centile) | 157.5 cm (98th centile) | (10–25th centile) | 13 cm (67th centile) | NA |

| Weight | 111.8 kg (at 30 years) | 67 kg (− 0.15SD) | NA | NA | 46 kg (>> + 3 SD) | 84.9 kg; + 2.5 SD (according to height) | NA | (98th centile) | 91.5 kg (98–99,6th centile) | (10–25th centile) | 46.8 kg (95th centile) | |

| Head circumference | 60 cm (at 30 years) | NA | NA | NA | 51 cm (− 1.2 SD) | 48 cm; − 0.97 SD at 3 years | NA | (98th centile) | 54.8 cm (75th centile) | (10–25th centile) | 54 cm | NA |

| Dysmorphisms | ||||||||||||

| Head | – | NA | NA | Normal | NA | Prominent forehead | Narrow face, prominent forehead, plagiocephaly | NA | NA | NA | Very fair hair | NA |

| Eye | – | Up slant palpebral fissures, proptosis | Thick eye brows | Normal | Thick eyebrows, hypertelorism, sunken eyes, short palpebral fissures | Telecanthu, epicanthus | Hypertelorism | Up slanting palpebral fissures, synophrys | NA | NA | Very Fair (blue) | Upslant palpebral fissures, myopia |

| Ear | – | Normal | Normal | Normal | Thick helix | Tags preauriculair | Folded ear ridges | Small, low set and posteriorly rotated | Large, narrow with thick helix and rotated | Large and narrow with a thick helix | NA | NA |

| Nose | – | Asymmetric due to cleft lip | Normal | Normal | Normal | Short upturned nose, large nose bridge | NA | Height nasal bridge, square tip | Broad nasal based | Broad base; high root | NA | NA |

| Cheeks | Full | Normal | Full | Normal | Full | Full | NA | NA | Full | Full | NA | NA |

| Lip | – | Cleft lip | Full lower lip | Normal | Full | Full lower lip; short philtrum | NA | NA | Full and everted lower lip | Full and everted lower lip | NA | Malformation of upper lip, prominent upper lip |

| Mouth | – | Cleft jaw bilateral | NA | Normal | NA | Macroglossia; prognathic | NA | Minor micrognathia | Macroglossia | Macroglossia | NA | NA |

| Palate | – | Cleft palate | NA | Normal | NA | NA | NA | Narrow palate | High arch | High arch | NA | NA |

| Teeth | – | Misaligned due to cleft jaw | NA | Normal | Oligodontia | Irregular, oligodontia | NA | Prominent front incisors | Overcrowded | Overcrowded | NA | Malaligned teeth with increased spacing |

| Developmental delay | ||||||||||||

| Intellectual disability | Mild – moderate | Mild | Profound | Mild | Profound | + | Moderate | Moderate | moderate to severe | mild-to-moderate | + | |

| Motor development | Walk without support | – | Walk without support | Walk without support | Walk without support | Normally but her movements are not fluent | + | Global developmental delay | Walk with a broad-based gait | global developmental delay | global developmental delay | + |

| Language delay | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | +; few words at 2 years old | – | first words at 3 years | NA |

| Anxiety | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | NA | ||

| Autism/autistic behavior | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | +; at 4 years | + | – | + |

| Epilepsy/seizures/spasms | ||||||||||||

| Type | Frontal-temporal | In early childhood absences, alter tonic-clonic seizures | Myoclonic seizures (3y11m) | Myoclonic seizures (2y9m), | NA | NA | Myoclonic seizures | NA | – | Tonic-clonic seizures | No seizures | Tonic-clonic seizures remotely in childhood and more recently complex partial seizures |

| Fingers abnormality | NA | Fetal pads | Tapering fingers- mild | – | Tapering fingers-mild | Clinodactyly | Tapering fingers | Tapering fingers with prominent fingertip pads |

Tapering finger – mild left 4th finger proximally implanted |

Tapering fingers – mild | – | Long fingers, widened tips, 5th finger clinodactyly |

| Toes | Foot pronation | Normal | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Bilateral hypo-plastic nails on both halluces | Short toes | NA | – | NA |

| Hypoglycemia | – | – | – | – | NA | – | NA | NA | + | + | – | NA |

| Hypotonia | + | – | – | – | NA | – | + | – | + | – | – | NA |

| Additional findings | Obsessive interest for electronic objects and their accumulation, acute pancreatitis, cholecystectomy, liver steatosis | Urinary continence problems | Umbilical hernia at birth, hyperactivity - PDD NOS/ADHD; obstipation | T cell skin lymphoma on the lower back; hypo-plastic nails, patchy eczema, thick ichthyic skin | Cafe-au-lait spot:1 truncal; large hands and feet; urinary continence problems inverted nipples; | His skin is also very fair | Cerebral visual impairment; ptosis | |||||

NA not available, “+” feature present, “-” feature absent

Discussion

Pathogenic changes within the SETD1B gene were found to have an associated specific DNAm signature. This specific DNAm was not substantially affected by differences in blood cell distribution and other variables such as technical differences and chromosomal aberrations. The specificity of the DNAm signature was highlighted by the lack of signature in patients carrying a deletion that did not include SETD1B or in a patient carrying a duplication of the region or patients with other neurodevelopmental disorders or syndromes. Moreover, we were able to assess the pathogenicity of two variants of unknown clinical significance: p.(Glu1692del) and p.(Glu1160Lys) in patients 6_mut and 7_mut, respectively.

The inheritance of variant p.(Glu1692del) in patient 6_mut was unknown. This variant results in the loss of residue Glu1692. The p.(Glu1160Lys) variant in the 7_mut patient occurred de novo. It is a missense variant present at very low frequencies in the general population (5/187386 alleles in the GnomAD database [23]; MAF < 0.01; rs959370052) and affects a weakly conserved amino acid. The methylation profile of both patients did not display a specific SETD1B signature, suggesting both variants do not result in a loss of SETD1B function and are probably not pathogenic. While patients 6_mut and 7_mut display clinical features compatible with the phenotype caused by SETD1B mutations, this is not related to the specific SETD1B methylation pattern, indicating that they do not have a SETD1B-related disorder.

We detected the specific SETD1B-related DNAm signature based on the methylation status of three different pathogenic variants in five patients. An increased sample size would lead to the possibility of detecting differences in DNAm between variants.

Four hypermethylated DMRs were found to be associated with SETD1B. The region located on chromosome 6 (chr6: 26195488-26195995; hg19) was not assigned to any gene and was found to be characterized by high DNase hypersensitivity with promoter activity and located in Homo sapiens histone cluster 1. Histone 1 (H1) is responsible for chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation during apoptosis [24, 25]. Note that the apoptotic process, regulation of cell death, and chromatin condensation were enriched in ORA (biological processes) of CpG sites of the SETD1B-related DNAm-specific signature. Another hypermethylated region on chromosome 6 (chr6: 32942063-32943025; hg19) was assigned to the BRD2 gene. It displays promoter and enhancer activity and overlaps exon 3 of BRD2. Pathak et al. [26] reported hypermethylation in another locus (CPG75) near the promoter of BRD2 as implicated in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) [26]. Hypermethylation of this locus was found to be associated with a single nucleotide polymorphism (rs3918149). Schultz et al. [27] could not confirm this association in the German population. However, in 2007, Cavalleri et al. published the results of genotyping rs3918149 variant across five independent JME cohorts, observing a significant effect of this SNP on epilepsy in the British and the Irish cohorts, but not in those of the German, Australian, and Indian [28]. Although the association of BRD2 and epilepsy is not clear, we tentatively speculate that the hypermethylation detected in BRD2 in our cohort may play a role in the occurrence of epilepsy in these patients. Two other hypermethylated DMRs detected in the SETD1B-related group analysis were found to be located on chromosomes 14 and 21 (chr14:45431885-45432516; chr21:36258423-36259797; hg19) and assigned to genes KLHL28, FAM179B, and RUNX1. The former covers a CpG island with promoter activity and a DNAse hypersensitivity cluster (exon 1 of FAM179B) while the latter corresponds to a CpG island with promoter activity at exon 4 of RUNX1 and a DNAse hypersensitivity cluster. The biological function of these genes could not be related to clinical features in our cohort; however, their localization in genomic regulatory regions suggests a role in SETD1B-related disorders.

A comparison of phenotypes of patients with a SETD1B DNAm signature showed overlapping clinical features such as intellectual disability, language delay, autism, seizures, full cheeks, and tapering fingers (Table 4). Interestingly, two patients presenting with the microdeletion, involving also KDM2B, were initially diagnosed with Beckwith Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) because of overgrowth and macroglossia, which are typical for BWS (MIM 130650). Hiraide et al. (2018) suggested that the deletion of KDM2B could be a possible reason for an overgrowth phenotype in these two patients [8]. Moreover, a KDM2B missense mutation (c.2503G > A) was identified to be associated with “paunch calf syndrome” [29]. The characteristic features of this syndrome include abdominal distension and tongue protrusion that are comparable with abdominal wall defects and macroglossia, features that are characteristics for BWS [30].

The results of this study show a strong effect of SETD1B function on DNA methylation. SETD1B is a known histone modifier that produces trimethylated histone H3 at Lys4 (H3K4me3), which may play a role in blocking of the de novo DNA methylation in some genomic regions. DNMT3L ((cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 3-like), which stimulates de novo DNA methylation, interacts only with unmodified H3K4. The methylation of H3K4 disables this interaction [31]. The loss of the function of SETD1B may lead to the insufficient production of H3K4me3 and, thereby, hypermethylation of the DNA in specific loci. Indeed, 82% of differentially methylated CpGs in patients with a SETD1B pathogenic variant were hypermethylated. The 18% of differentially methylated CpGs that were hypomethylated remain unexplained by this mechanism, but these may be secondary effects, caused by altered expression of target genes of SETD1B.

Syndromic disorders have often similar clinical features. Genetic testing has multiple limitations. For instance, the resolution often prevents it from detecting low-frequency mosaicism. Moreover, the reason underlying the clinical features can occasionally not easily be inferred from the variants if variant occurs in non-coding regions, contiguous genes are deleted, or if they have been annotated as VUS. Examination of specific DNAm signatures was previously described as a powerful solution in the classification of various unresolved cases including syndromic Mendelian disorders, imprinting disorders, repeat expansion disorders, and uncertain clinical diagnosis with VUS [16, 17] and has therefore been proposed as a novel molecular diagnostic test. Our results reinforce this observation indicating that the specific DNAm signature has a diagnostic value and can be used as an additional diagnostic test to resolve variants of unknown significance in SETD1B.

Due to the small sample, we were unable to determine whether the loss of the KDM2B caused a specific DNAm signature. Studies including a sufficient number of patients are needed to solve this. The other limitation of our study was the technical differences between samples. Different DNA isolation methods between samples may influence the results.

Methods

Patients

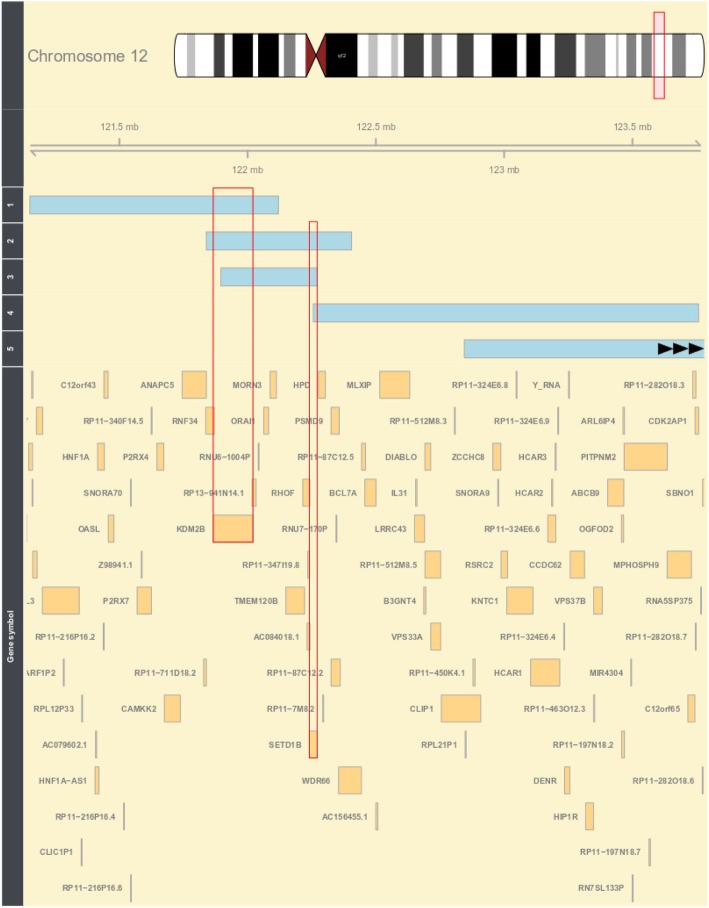

Whole blood DNA samples from 13 individuals were collected for the methylation study. Seven patients had point mutations in SETD1B, which were identified by whole-exome sequencing (WES), and five chromosomal 12q24.12-32 aberrations. One of the five patients had the deletion involving KDM2B (1_del12q), two the deletion of both KDM2B and SETD1B (2-del12q, 3_del12q), one the deletion on SETD1B (4_del12q), one the deletion not involving KDM2B and SETD1B, and one the duplication of 12q24.12 not involving KDM2B and SETD1B. Table 1 shows the genetic aberrations and inheritance of the patients included in the analysis. Figure 6 depicts the comparison between the deleted regions and genes in patients with microdeletions of 12q24.31 from the cohort (according to Hg19). Informed consent was obtained for each patient.

Fig. 6.

Comparison between deleted regions in patients with a microdeletion of 12q24.31. The light blue bars represent the deleted regions for individual patients. Numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 represent patients 1_del12q24.31, 2_del12q24.31, 3_del12q24.31, 4_del12q24.31, and 5_del12q24.31, respectively. The red frames highlight genes SETD1B and KDM2B. Note: microdeletion of patient 5_del12q24.31 has not been fully displayed on the plot and does not overlap KDM2B and SETD1B

Healthy controls

Whole blood DNA samples were collected from 60 healthy individuals.

Cohort details are listed in Additional file 4: Table S4.

Methylation EPIC array

The samples were divided into two batches: the first contained seven DNA samples from the patients (two females and five males) and 40 samples from the healthy controls (20 females and 20 males) and the second contained six DNA samples from the patients (two females and four males) and 20 from the healthy controls (ten females and ten males). The samples were randomized and sent to GenomeScan in Leiden (ISO/IEC 17025 approved), where the bisulfite treatment and the hybridization to the Infinium Methylation EPIC array (Illumina) were processed. The raw methylation data were obtained and the quality (QC) of the data assessed using the MethylAid script in R. (GenomeScan’s Guidelines for Successful Methylation Experiments Using the Illumina Infinium® HumanMethylation BeadChip).

Normalization and data analysis

The EPIC array data was loaded onto the R software and normalized using the preprocessFunnorm function of “minfi” R package [32]. All probes containing SNPs (MAF > 0.01), cross-hybridization probes, and probes located on the sex chromosomes were excluded; 776,920 probes remained for analysis. The beta values (ratio of the methylated probe intensity ranging from 0 to 1) were obtained for all the patients from the cohort. Row beta values were normalized and PCA carried out.

Estimation of the blood cell type distribution

White blood cell type was estimated for each patient using estimateCellCounts function in R “FlowSorted.Blood.EPIC” package [33]. The counts were calculated for CD8T (cytotoxische T cell), CD4T(T helper cells), NK (natural killer cells), B cell (B lymphocytes), mono (monocytes), and gran (granulocytes). The P value was calculated for each patient of our cohort (13 patients), for each cell type (Crawford-Howell t test; R software). Subsequently, the Bonferroni correction was applied for 78 tests (six cell types × 13 patients). We assume that the distribution of the cell types was significantly disturbed if the Bonferroni-corrected P value for the cell types was less than 0.05.

Group analysis and identification of CpG sites for the DNAm-specific signature

DNA methylation of patients in the groups (five patients in the SETD1B-related group and two in the KDM2B-related group) were compared with methylation in a group of 59 healthy controls using the “minfi” R-package. The design model was corrected for age, gender, batch, and cell distribution. The beta values were obtained and logit transformed into M values. The adjusted P values for the M values were calculated, and the significance threshold was 0.05. Finally, to avoid false-positive results, CpG sites with an effect size of at least 10% difference in an average of DNAm between patient groups and the control group were selected. In this way, we identified 3340 and 697 differentially methylated CpGs in the SETD1B-related group and KDM2B-related group, respectively.

Analysis of a specific methylation signature

Beta values of CpGs selected in the group analyses were used to perform the unsupervised hierarchical clustering (“pheatmap” R-package). Two heatmaps were created, one for the SETD1B-related group and the other for the KDM2B-related group. Each heatmap was created for all individuals in the cohort (13 patients and 60 controls).

Examination of the specificity of the SETD1B-related DNAm signature

Whole blood DNA samples were collected from 502 patients with various neurodevelopmental syndromes. To compare the methylation values of our cohort with these additional samples, we performed re-normalization, according to the Illumina normalization method, with background correction using the “minfi” R-package. To select significant differentially methylated SETD1B-related CpGs, we used similar filtering steps for these in the SETD1B-related group analysis namely, a corrected P value less than 0.05 and an effect size of at least 10% difference. Correlated probes with r2 higher than 0.8 were removed from this analysis. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) was used to examine the DNA methylation profiles. All samples used in this analysis and the details of the method were fully described by Aref-Eshghi et al. [16, 17]. The list of 502 samples used in this specific analysis is listed in Additional file 5: Table S5.

Identification of differentially methylated regions

To identify the DMRs between patient and control groups, a “bumphunter” R-package was used. The design model was corrected for age, gender, batch, and cell distribution.

The P value for each region was calculated and multiple testing applied according to the family-wise error rate. The significant DMRs were selected based on the two filter steps: (i) Fwer < 0.05 and (ii) at least three differentially methylated CpGs within the region (L > 2).

ORA—WEB-based Gene Set Analysis Toolkit

ORA were carried out for the first and unique gene symbol annotated to the CpGs identified during group analysis (according to the Infinium MethylationEPIC v1.0 B4 Manifest File). Basic parameters were as follows: organism–human, method–ORA, functional database–gene ontology (biological process and molecular function), and reference set for enrichment analysis–genome protein-coding. Advanced parameters were as follows: minimum number of genes for a category–5, maximum number of genes for category–2000, multiple test adjustment–Benjamini-Hochberg (BH), significant level–top 10, number of categories expected from set cover–10, number of categories visualized in the report–40, and color in DAG–continuous.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. The estimation of the cell types distribution and the calculation of P-values of the cell types distribution.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Significant differentially methylated CpGs identified in the SETD1B-related group analysis.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Significant differentially methylated CpGs identified in the KDM2B-related group analysis.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Cohort details.

Additional file 5: Table S5. The list of 502 samples used in the examination of the specificity of the SETD1B-related DNAm signature.

Additional file 6: Table S6. Contains adjusted P-values for M values and empirical p-values for 3340 significant differentially methylated CpGs calculated in the SETD1B-related group analysis and permutation analysis, respectively.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the physicians and genetic counselors for their help with participant recruitment.

Additional information

Contains additional information about (1) Quality control, (2) pre- processing data and statistical methods, (3) estimation of the cell type distribution, (4) statistical model, (5) verification of the results, (6) and the flow diagram of analysis.

Abbreviations

- BWS

Beckwith Wiedemann syndrome

- DHS

DNase I hypersensitivity site

- DMR

Differentially methylated region

- Fwer

Family-wise error rate

- ID

Intellectual disability

- JME

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- ORA

Over-representation analysis

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- QC

Quality control

- RDMR

Reprogramming Differentially Methylated Regions

- VUS

Variant of uncertain significance

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

Authors’ contributions

MA, IMK, and MMAM designed the project. MA, SMM, KB, AC, AJE, TF, HI, MJ, H-GK, AL, SMEL, GL, IM, SM, NM, RR, ER-S,YQ. HS, DAS, and IMK contributed to the sample collection. SSM, DAS, H-GK, SD, SL, HS, NM, GL, RR, and NSS contributed to the clinical assessment of participants. IMK, MA, PH, BS, and EAE designed the statistical analysis. IMK, AV, BS, and EAE performed the statistical analysis. KL and IMK performed the laboratory experiments. IMK, MA, and BS wrote the manuscript. MMAM contributed to the manuscript revision. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The funding was obtained from the Catalan Government PERIS program (SLT002/16/00310) and the Techgene project from the FP7 framework (ID: 223143).

Availability of data and materials

All HumanMethylation450 data are available on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

METC waived (anonymous study, further study in line with a clinical question).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

M. Alders and M. M. A. M. Mannens contributed equally to this work.

This person has passed away.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13148-019-0749-3.

References

- 1.Baple E, Palmer R, Hennekam RC. A microdeletion at 12q24.31 can mimic beckwith-wiedemann syndrome neonatally. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1(1):42–45. doi: 10.1159/000275671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chouery E, Choucair N, Abou Ghoch J, El Sabbagh S, Corbani S, Megarbane A. Report on a patient with a 12q24.31 microdeletion inherited from an insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus father. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4(3):136–142. doi: 10.1159/000346473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palumbo O, Palumbo P, Delvecchio M, Palladino T, Stallone R, Crisetti M, Zelante L, Carella M. Microdeletion of 12q24.31: report of a girl with intellectual disability, stereotypies, seizures and facial dysmorphisms. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(2):438–444. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiao Y, Tyson C, Hrynchak M, Lopez-Rangel E, Hildebrand J, Martell S, Fawcett C, Kasmara L, Calli K, Harvard C, et al. Clinical application of 2.7M Cytogenetics array for CNV detection in subjects with idiopathic autism and/or intellectual disability. Clin Genet. 2013;83(2):145–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labonne JD, Lee KH, Iwase S, Kong IK, Diamond MP, Layman LC, Kim CH, Kim HG. An atypical 12q24.31 microdeletion implicates six genes including a histone demethylase KDM2B and a histone methyltransferase SETD1B in syndromic intellectual disability. Hum Genet. 2016;135(7):757–771. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1668-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129(4):823–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janzer A, Stamm K, Becker A, Zimmer A, Buettner R, Kirfel J. The H3K4me3 histone demethylase Fbxl10 is a regulator of chemokine expression, cellular morphology, and the metabolome of fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(37):30984–30992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.341040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiraide T, Nakashima M, Yamoto K, Fukuda T, Kato M, Ikeda H, Sugie Y, Aoto K, Kaname T, Nakabayashi K, et al. De novo variants in SETD1B are associated with intellectual disability, epilepsy and autism. Hum Genet. 2018;137(1):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Den Kouhei, Kato Mitsuhiro, Yamaguchi Tokito, Miyatake Satoko, Takata Atsushi, Mizuguchi Takeshi, Miyake Noriko, Mitsuhashi Satomi, Matsumoto Naomichi. A novel de novo frameshift variant in SETD1B causes epilepsy. Journal of Human Genetics. 2019;64(8):821–827. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0617-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(5):295–304. doi: 10.1038/nrg2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimshony T, Zhang J, Keshet I, Bustin M, Cedar H. The role of DNA methylation in setting up chromatin structure during development. Nat Genet. 2003;34(2):187–192. doi: 10.1038/ng1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aref-Eshghi E, Schenkel LC, Lin H, Skinner C, Ainsworth P, Pare G, Rodenhiser D, Schwartz C, Sadikovic B. The defining DNA methylation signature of Kabuki syndrome enables functional assessment of genetic variants of unknown clinical significance. Epigenetics. 2017;12(11):923–933. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2017.1381807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choufani S, Cytrynbaum C, Chung BH, Turinsky AL, Grafodatskaya D, Chen YA, Cohen AS, Dupuis L, Butcher DT, Siu MT, et al. NSD1 mutations generate a genome-wide DNA methylation signature. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10207. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobreira N, Schiettecatte F, Valle D, Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(10):928–930. doi: 10.1002/humu.22844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krzyzewska IM, Alders M, Maas SM, Bliek J, Venema A, Henneman P, Rezwan FI, Lip KVD, Mul AN, Mackay DJG, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome patients without molecular confirmation after routine diagnostics. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0649-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aref-Eshghi E, Rodenhiser DI, Schenkel LC, Lin HX, Skinner C, Ainsworth P, Pare G, Hood RL, Bulman DE, Kernohan KD, et al. Genomic DNA methylation signatures enable concurrent diagnosis and clinical genetic variant classification in neurodevelopmental syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102(1):156–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aref-Eshghi E, Bend EG, Colaiacovo S, Caudle M, Chakrabarti R, Napier M, Brick L, Brady L, Carere DA, Levy MA, et al. Diagnostic utility of genome-wide DNA methylation testing in genetically unsolved individuals with suspected hereditary conditions. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104(4):685–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobreira N, Brucato M, Zhang L, Ladd-Acosta C, Ongaco C, Romm J, Doheny KF, Mingroni-Netto RC, Bertola D, Kim CA, et al. Patients with a Kabuki syndrome phenotype demonstrate DNA methylation abnormalities. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017;25(12):1335–1344. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0023-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butcher DT, Cytrynbaum C, Turinsky AL, Siu MT, Inbar-Feigenberg M, Mendoza-Londono R, Chitayat D, Walker S, Machado J, Caluseriu O, et al. CHARGE and Kabuki syndromes: gene-specific DNA methylation signatures identify epigenetic mechanisms linking these clinically overlapping conditions. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(5):773–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aref-Eshghi E, Bend EG, Hood RL, Schenkel LC, Carere DA, Chakrabarti R, Nagamani SCS, Cheung SW, Campeau PM, Prasad C, et al. BAFopathies’ DNA methylation epi-signatures demonstrate diagnostic utility and functional continuum of Coffin-Siris and Nicolaides-Baraitser syndromes. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4885. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07193-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12(6):996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Vasaikar S, Shi Z, Greer M, Zhang B. WebGestalt 2017: a more comprehensive, powerful, flexible and interactive gene set enrichment analysis toolkit. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W130–W137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, Collins RL, Laricchia KM, Ganna A, Birnbaum DP et al. Variation across 141,456 human exomes and genomes reveals the spectrum of loss-of-function intolerance across human protein-coding genes. bioRxiv. 2019:531210.

- 24.Kijima M, Mizuta R. Histone H1 quantity determines the efficiencies of apoptotic DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation. Biomed Res Tokyo. 2019;40(1):51–56. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.40.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner AL, Watson M, Wilkins OG, Cato L, Travers A, Thomas JO, Stott K. Highly disordered histone H1-DNA model complexes and their condensates. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(47):11964–11969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805943115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pathak S, Miller J, Morris EC, Stewart WCL, Greenberg DA. DNA methylation of the BRD2 promoter is associated with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy in Caucasians. Epilepsia. 2018;59(5):1011–1019. doi: 10.1111/epi.14058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz H, Ruppert AK, Zara F, Madia F, Iacomino M, Vari MS, Balagura G, Minetti C, Striano P, Blanche A et al. No evidence for a BRD2 promoter hypermethylation inblood leukocytes of Europeans with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2019;60(5):E31–E36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Cavalleri GL, Walley NM, Soranzo N, Mulley J, Doherty CP, Kapoor A, Depondt C, Lynch JM, Scheffer IE, Heils A, et al. A multicenter study of BRD2 as a risk factor for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48(4):706–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Testoni S, Bartolone E, Rossi M, Patrignani A, Bruggmann R, Lichtner P, Tetens J, Gentile A, Drogemuller C. KDM2B is implicated in bovine lethal multi-organic developmental dysplasia. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brioude F, Kalish JM, Mussa A, Foster AC, Bliek J, Ferrero GB, Boonen SE, Cole T, Baker R, Bertoletti M, et al. Expert consensus document: clinical and molecular diagnosis, screening and management of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: an international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(4):229–249. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose NR, Klose RJ. Understanding the relationship between DNA methylation and histone lysine methylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839(12):1362–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(10):1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salas LA, Koestler DC, Butler RA, Hansen HM, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT, Christensen BC. An optimized library for reference-based deconvolution of whole-blood biospecimens assayed using the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC BeadArray. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1448-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. The estimation of the cell types distribution and the calculation of P-values of the cell types distribution.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Significant differentially methylated CpGs identified in the SETD1B-related group analysis.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Significant differentially methylated CpGs identified in the KDM2B-related group analysis.

Additional file 4: Table S4. Cohort details.

Additional file 5: Table S5. The list of 502 samples used in the examination of the specificity of the SETD1B-related DNAm signature.

Additional file 6: Table S6. Contains adjusted P-values for M values and empirical p-values for 3340 significant differentially methylated CpGs calculated in the SETD1B-related group analysis and permutation analysis, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

All HumanMethylation450 data are available on request.