Abstract

Purpose: We explored the perspectives of experts on increasing the recruitment of Indigenous students into Canadian physical therapy (PT) programmes. Methods: For this qualitative interpretivist study, we conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews with individuals with expertise in encouraging Indigenous students to pursue higher education, recruiting them into PT programmes, or both. Data were organized using NVivo and analyzed using the DEPICT method, which included inductive and deductive coding to develop broader themes. Results: Analyzing the participants’ perspectives revealed three themes, which could be layered sequentially, so that each informed the next: (1) building insight by increasing awareness of structural forces and barriers; (2) changing thinking, using a paradigm shift, from the dominant Eurocentric orientation to a view that respects the sovereignty and self-determination of Indigenous peoples; and (3) informing action by recommending practical strategies to facilitate the recruitment of Indigenous students into Canadian PT programmes. Conclusions: This is the first study to provide evidence of the structural considerations, barriers to, and facilitators of increasing the recruitment of Indigenous students into Canadian PT programmes.

Key Words: barrier, health care, Indigenous, recruitment

Abstract

Objectif : explorer les points de vue des experts pour recruter plus d’étudiants autochtones au sein des programmes de physiothérapie canadiens. Méthodologie : dans le cadre de cette étude d’interprétation qualitative, les chercheurs ont réalisé des entrevues semi-structurées approfondies avec des personnes qui possèdent des compétences pour encourager les étudiants autochtones à faire des études supérieures et pour les recruter dans des programmes de physiothérapie. Ils ont organisé les données à l’aide du logiciel NVivo et les ont analysées à l’aide de la méthode DEPICT, qui inclut un codage inductif et déductif pour établir des thèmes plus vastes. Résultats : l’analyse des points de vue des participants a fait ressortir trois thèmes, qui pourraient être superposés séquentiellement pour que chacun éclaire le suivant, comme suit : 1) favoriser les prises de conscience en faisant mieux connaître les forces et obstacles structurels; 2) faire évoluer les mentalités par un changement de paradigme afin de passer de l’orientation eurocentrique dominante à une vision qui respecte la souveraineté et l’autodétermination des peuples autochtones et 3) éclairer les actions en recommandant des stratégies pratiques pour faciliter le recrutement d’étudiants autochtones au sein des programmes de physiothérapie canadiens. Conclusions : c’est la première étude à fournir des données probantes sur les facteurs structurels, les obstacles et les incitations liés au recrutement d’un plus grand nombre d’étudiants autochtones au sein des programmes de physiothérapie canadiens.

Mots-clés : Autochtones, obstacle, recrutement, soins de santé

Canada’s Indigenous peoples (e.g., First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) are the fastest growing population in the country,1 but despite this rapid growth, relatively few Indigenous clinicians work in the Canadian health care system.2 Recommendation 23 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) report, released in 2015, calls for an increased number of Aboriginal professionals working in the health care field.3 This need was further recognized in the position statement released by the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA), which states, “There is limited availability of health care professionals skilled in the delivery of culturally competent and safe health care.”2(p. 10)

Increasing the recruitment of Indigenous students into physical therapy (PT) programmes in Canada is important for several reasons. First, there is a need for PT among this population. For example, more than 62% of First Nations adults report having at least one chronic health condition.4–7 A second reason is that Indigenous physiotherapists are underrepresented in the profession in Canada. Although no data exist on how many physiotherapists working in Canada are Indigenous, Coghlan and colleagues found that, of the 14,135 applicants to PT programmes in the decade from 2004 to 2014, only 112 (0.8%) identified as Aboriginal and, of those, only 31 accepted an offer of admission.8

There is also an increasing need for culturally safe practice in PT and throughout health care, and increasing the number of Indigenous physiotherapists can directly meet this need. By culturally safe practice, we are referring to the approach developed by Maori nurse Irihapeti Ramsden in response to the mainstream health system’s inability to meet the needs of Maori people in Aotearoa/New Zealand.9,10 Physiotherapy New Zealand’s professional guidelines explain that cultural safety “relates to the experience of the recipient of physiotherapy service and extends beyond cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity.”11(p. 6) This means that only the client can determine whether her or his experience has been culturally safe. The Health Council of Canada defines cultural safety as

an outcome, defined and experienced by those who receive the service—they feel safe; … based on respectful engagement that can help patients find paths to well-being; … based on understanding the power differentials inherent in health service delivery, the institutional discrimination, and the need to fix these inequities through education and system change; and requires acknowledgement that we are all bearers of culture—there is self-reflection about one’s own attitudes, beliefs, assumptions, and values.12(p. 5)

At the core of this approach is the critical need to address the health inequalities that exist between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous peoples as a result of colonization.2,4,13 The colonization of Indigenous peoples used racialization and “othering” to justify claims to land and practices intended to erase the Indigenous way of life.13 Central to this process was the creation of legislation, including the Indian Act of 1876 (which is still in force today), through which the government of Canada gave itself the authority to determine who was defined as an Indian. The act also introduced the reserve system, which limited where Indigenous peoples could live, denied Indigenous peoples the right to vote, and initiated the Indian residential school system, which forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families and subjected them to assimilation into European culture as well as to widespread physical, psychological, and sexual abuse.3,13 The Indian Act and other legacies of colonization continue to shape the health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada, including the underrepresentation of Indigenous clinicians in the health care system.13

Andersen and colleagues14 outlined four strategies for optimizing the educational success of Indigenous students in Australia, which has a similar colonial history to Canada: (1) recruiting highly dedicated staff to optimize the success of these students, (2) optimizing cultural and academic comfort for new students, (3) ensuring Indigenous centres in Indigenous higher education, and (4) keeping Indigenous support systems under constant review. Another Australian study, which examined strategies to increase the recruitment of Indigenous people into nursing, found that streamlining placement at university and appointing a supportive academic mentor for each student increased students’ feelings of inclusion and acceptance.15 Although neither study was specific to PT, Canada has yet to introduce consistent strategies in any health care professional programme to promote the recruitment of Indigenous students.

In Canada, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine is a leader in increasing the recruitment of Indigenous individuals into its medical programmes: it sets aside at least two seats for Indigenous students, and it employs an Indigenous Reference Group to provide advice on research, administration, and academic issues as well as accommodation of an Indigenous worldview.16,17 The Canadian National Aboriginal Health Organization recognized three considerations for recruiting mature Indigenous students into medical programmes: (1) creating an adequate pool of Indigenous participants, involving preparatory programmes and focused recruitment initiatives, (2) ensuring financial support for students, and (3) providing an environment in which Indigenous students feel respected.18 These considerations are particularly salient for recruiting Indigenous students to study PT, which is a master’s-level degree programme and therefore requires a pool of eligible applicants with the appropriate undergraduate prerequisites.

In 2015, the same year that the TRC report was released, Gruenig reported the strategies being implemented by Canadian PT programmes to recruit Indigenous students. She noted that the University of Saskatchewan had reserved 12% of its seats,19 and the University of Western Ontario had reserved 2 seats, for Indigenous students.20 Of the 14 PT programmes she reviewed, 12 invited Indigenous students to self-identify during the application process, and 5 universities (McMaster University, Dalhousie University, University of Alberta, University of Saskatchewan, and University of Manitoba) had a separate admissions stream for Indigenous applicants who met the minimum admission criteria.16 For example, McMaster University automatically provided a spot in its interview process to Indigenous students who met the minimum admission criteria.16

Although these admissions changes are a step in the right direction, the evidence to guide a more comprehensive approach to increasing the number of Indigenous physiotherapists in Canada is limited.16 In response to this research gap, the TRC’s calls to action, and the CPA’s 2015 position statement, in this study we sought to explore the recommendations of individuals who are working in this area for increasing the number of Indigenous students enrolled in Canadian PT programmes.

Methods

This cross-sectional qualitative interpretivist study was approved by the research ethics board at the University of Toronto and the Six Nations Elected Council Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided informed consent. The research team included two male and two female second-year MScPT students. Two of these student researchers are white and two are racialized; none are Indigenous. The team also included one white female faculty advisor, who is a physiotherapist, and a co-advisor, who is an Indigenous female physiotherapist.

Participants

The participants were required to have knowledge of and insight into the recruitment of Indigenous students into Canadian PT programmes. They consisted of (1) Indigenous graduates of Canadian PT programmes, (2) advocates for increasing the number of Indigenous students enrolled in health care professional programmes in Canada, (3) faculty in Canadian university or college programmes working on engaging Indigenous students in their programmes, and (4) those involved in recruiting students from minority groups into PT and other health care programmes. Participants had to speak English. We aimed for at least half of the participants to be Indigenous and for perspectives to come from across Canada.

Recruitment

We recruited participants for this study using purposive sampling to intentionally find those individuals who would most likely be able to contribute to the research question and to emphasize the perspectives of Indigenous people.21 We used snowball sampling to invite the initial participants to suggest others who met the inclusion criteria.22

Targeted invitations were issued by an email address created for this study to individuals who seemed to meet the inclusion criteria. These individuals were identified through the professional networks of the research team members and by searching the academic literature. Recruitment consisted of three staggered waves of invitations, with efforts to ensure that participants were equally distributed across the country and that at least half of the participants were Indigenous.

Data collection

A one-on-one, semi-structured interview lasting 30–90 minutes was conducted with each participant. Interviews were conducted by one of two investigators (JS, AM) in person, by telephone, or over Skype. Open-ended questions were used to explore the participants’ experiences in and perspectives on increasing the enrolment of Indigenous students in PT programmes in Canada. Interview questions were provided to the participants before the interview, and the interview guides were piloted before arranging the interviews. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted collaboratively, with all investigators using the six steps of the DEPICT method.23 This method was chosen because it is a rigorous approach for collaboratively analyzing qualitative data.

In the first step, dynamic reading, all six research team members read a subset of the transcripts, keeping in mind the research question and writing down the important topics they found.23 In the engaged codebook development step, these topics were organized into a draft code book, which was piloted by four investigators. The final code book was then used to independently code each transcript twice by different investigators during participatory coding.23 The identified codes were entered into NVivo, Version 10.0 (QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia). The data for each code were analyzed in the inclusive reviewing and summarizing of categories step, resulting in a descriptive analysis summary for each code.23 In collaborative analysis, the team reviewed the summaries and reflected on how these results answered our research question.23 In the final step, translation, we created a schematic of the results.

Results

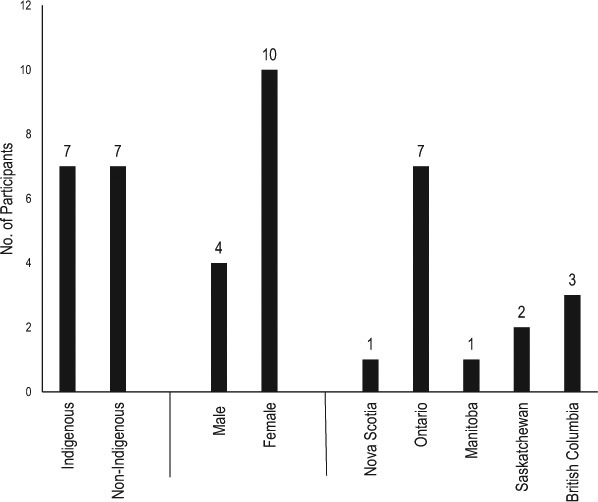

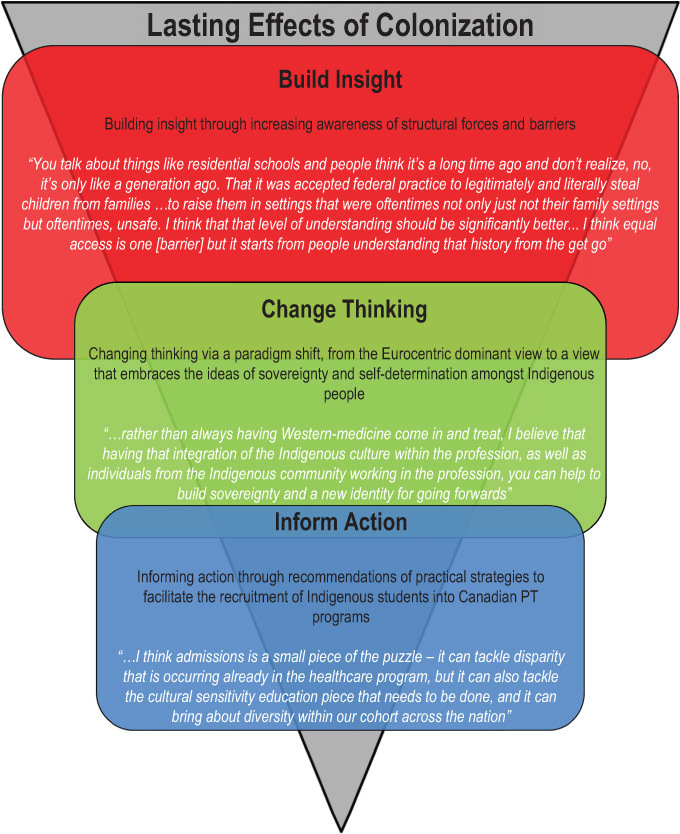

We interviewed 14 participants, half of whom were Indigenous (see Table 1 and Figure 1). Overall, the participants identified three themes related to increasing the enrolment of Indigenous students in Canadian PT programmes (see Figure 2). First, they identified the need to build insight at Canadian universities by increasing the awareness of the lasting effects of colonization, which have produced the structural forces and barriers influencing the low enrolment of Indigenous students. Second, they described how building insight can lead to a change in thinking, whereby university administrators and PT professionals develop self-reflection about the dominant Eurocentric orientation of the field, which in turn can inform action about recruitment strategies.

Figure 1.

Demographics of participants based on their self-identification as Indigenous, their gender, and their place of residence.

Figure 2.

Participants’ perspectives on increasing the recruitment of Indigenous students into Canadian physiotherapy programmes.

Build insight

The participants identified several barriers that limit the recruitment of Indigenous students into PT programmes in Canada, emphasizing the overarching structural forces that have erected these barriers. Contrary to individualistic barriers, structural forces are systemic and institutional, and they create challenges at the population level. The core structural consideration emphasized by the participants was the lasting effects of colonization, including entrenched stereotypes, as described by this Indigenous participant:

What are these [non-Indigenous] students going to think about me and my research when they’re coming from a completely different world? Maybe they think about me as a stereotype. These are the obstacles that I know I’m going to have to overcome and be strong about, you know? I really weigh who I’m going to want to deal with on their ignorance or whatever. Or how I’m going to deal with that, how many times I’m going to have to deal with that. That weighs on me. (Participant 14)

Participants described how the legacy of colonization continues to create hardships and inequalities for Indigenous peoples today. They explained how these challenges are fueled by a lack of awareness among many non-Indigenous people of Canada’s colonial history. When asked to address inequitable access to higher education, one participant stated,

You talk about things like [Indian] residential schools, and people think it’s a long time ago and don’t realize, no, it’s only like a generation ago. That it was accepted federal practice to legitimately and literally steal children from families and take them physically away to raise them in settings that were oftentimes not only just not their family settings but [also] oftentimes unsafe. I think that that level of understanding should be significantly better. … I think equal access is one [barrier], but it starts from people understanding that [history] from the get-go. (Participant 4)

Participants also identified geographical location as a barrier to recruiting Indigenous students into Canadian PT programmes. An effect of the government of Canada’s reserve system, a strategy of colonization, was to situate Indigenous communities away from urban centres and, consequently, the majority of Canadian universities. Therefore, to obtain a post-secondary education, rural Indigenous students must separate themselves from their community. The participants identified several problems resulting from students moving away from their community, including an inability to fulfill familial responsibilities, feelings of isolation and alienation, and safety concerns on campus. As one Indigenous participant explained, “Every time we extract somebody who’s a support person in the community, then we leave a gap” (Participant 10). This finding points to not only the challenges of recruiting Indigenous students but also the need for strategies to support them while they are in their programme.

Table 1.

Descriptions of Participants’ Expertise

| Participant | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Non-Indigenous health care provider involved in setting physiotherapy policies |

| 2 | Non-Indigenous physiotherapist involved in university-level recruitment |

| 3 | Indigenous physiotherapist |

| 4 | Indigenous physiotherapist |

| 5 | Non-Indigenous physiotherapist involved in First Nations outreach at the university level |

| 6 | Non-Indigenous physiotherapist involved in the university admissions process |

| 7 | Indigenous physiotherapist |

| 8 | Non-Indigenous physiotherapist with experience working with Indigenous populations |

| 9 | Indigenous professional involved in increasing the Indigenous presence in post-secondary institutions |

| 10 | Indigenous professional working in Indigenous education |

| 11 | Non-Indigenous physiotherapist involved in Indigenous health and Indigenous research |

| 12 | Non-Indigenous health care professional working in Indigenous health care |

| 13 | Indigenous rehabilitation professional involved in Indigenous health care research |

| 14 | Indigenous health care professional with post-secondary expertise in colonialism |

Another structural issue emphasized by participants was inequitable educational attainment. They stated that many Indigenous students do not complete high school because of wider social determinants, such as disparities in funding for education and the need to leave communities to attend high school. As a result, Indigenous students may have low literacy rates and lack the necessary prerequisites for entering health care programmes. Educational preparation is crucial when considering the recruitment of Indigenous students into PT programmes, but it must be tackled contextually, as this participant explained: “Until [high school completion] is addressed in some systemic way, we’re going to continue to have a scarcity of potential candidates” (Participant 10).

The participants explained how geographical and educational barriers are linked to colonization, which has prevented many Indigenous students from achieving higher education. Thus, they stressed the importance of Canadians unlearning stereotypes and misconceptions about Indigenous peoples and learning about the history and effects of colonization. They encouraged Canadians to read the TRC report to “make sure they have a good idea of the horrors Indigenous peoples had to endure” (Participant 14).

Change thinking

Building insight into structural barriers was viewed as a prerequisite for enabling a shift in thinking. The participants stressed the need for a paradigm shift among Canadians of settler descent and other non-Indigenous Canadians, especially those at Canadian universities and in PT programmes, to recognize the inequalities that Indigenous peoples live with. They explained that this shift entails recognizing the limits of the dominant Eurocentric worldview, which positions Western norms as the normal and right way of being and thinking, and instead moving toward respect for the sovereignty and self-determination of Indigenous peoples.

This participant explained the shift needed for health care:

Rather than always having Western medicine come in and treat, I believe that having that integration of the [Indigenous] culture within the profession, as well as individuals from the [Indigenous] community working in the profession, you can help to build sovereignty and a new identity for going forwards. (Participant 1)

Another participant said that “non-Indigenous people should strive to incorporate, honour, and privilege Indigenous knowledge” (Participant 11). Participants emphasized that colonization continues to influence and serve as a barrier to increasing the enrolment of Indigenous students in PT programmes, but changing thinking and developing respect for Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty and self-determination can begin to address these pervasive effects.

Participants also described the importance of university recruiters establishing authentic relationships with Indigenous communities by building trust, mutual respect, and genuine connections as part of the paradigm shift.

From a relationships perspective, I think it’s really important for universities and schools of PT, whether there’s an individual, or several individuals, who can build relationships within communities, because once a relationship has been established and developed, then it’s a little bit more of an authentic engagement that can happen. (Participant 11)

Reflecting on the importance of investing in partnerships, another participant stated,

It shows the importance, that you are showing them that they are important. That’s why you’re taking the time to come there and showing them it’s important, and have it be a positive contact. … It’s hard when a stranger comes to the community, especially if they are not Indigenous. So just to, you know, be able to show that you are actually taking the time to do that, it’s just a matter of respect and showing the total willingness that that’s what you want. (Participant 14)

The participants explained that relationships should be built on a foundation of reciprocity so that they are authentic and enduring. For example, they described the reciprocal benefits that could arise from increasing clinical placements on reserves and in remote areas: students would benefit from a “better understanding, in terms of cultural sensitivity and humility” (Participant 6), the community would benefit from the services, and the profession would benefit by increasing Indigenous awareness of and interest in PT. The participants also noted how increasing the engagement of Indigenous students could strengthen the profession:

Diversity in a profession helps to enhance and grow the profession itself … and is good because it breaks down those social, political misunderstandings or even stereotypes that may grow when you have a more insulated profession or a profession that operates in a silo. (Participant 1)

The participants described how a paradigm shift is needed to move away from a deficit-based approach (e.g., that positions Indigenous People as a “problem”) and toward a strength-based approach (e.g., that begins from a place of respect and dignity), which would identify the self-determining capacity of Indigenous peoples to control their own decisions. In turn, this paradigm shift could increase the likelihood of Indigenous students entering PT programmes as a result of relationship building and reciprocity, increased diversity, and a greater emphasis on holistic care. One Indigenous participant used the phrase “for our people, by our people” (Participant 11), referring to the notion that increasing the number of Indigenous health care professionals could enable Indigenous peoples to provide the most suitable care for their communities. Moreover, the paradigm shift advocated for PT was viewed as part of the wider shift underway in Canada for reconciliation and nation building.

Inform action

Building awareness, which can attend to the structural challenges that exist in Canadian society, and the change in thinking that can result, set the stage for informing actions to increase the enrolment of Indigenous students in Canadian PT programmes. Participants described the need for universities to develop strategies that increase Indigenous awareness of PT programmes and PT as a profession: organizing rural outreach efforts such as in-school visits and social media marketing campaigns; encouraging face-to-face engagement between current and prospective students during science fairs and university campus tours; and encouraging active efforts by recruitment officers and liaisons to guide, assist, and support Indigenous students. One participant suggested bringing preventive physical rehabilitation programmes to broaden Indigenous awareness of physiotherapists’ scope of practice.

This study also highlighted the need for Indigenous physiotherapists to act as both role models and ambassadors for their people by returning to their community as practising professionals and thereby “facilitate more students from the area, kind of seeing these role models and wanting to follow in their shoes” (Participant 7). Various participants also several times emphasized sparking interest and engaging Indigenous students in sport and science as early as the elementary school level, specifically in an effort to “instil hope” (Participant 11).

Strategies were also proposed for ways in which Canadian PT programmes’ admissions processes could be modified to better support Indigenous students pursuing higher level education. Considering the financial barriers limiting the number of Indigenous student applicants, increased financial supports and scholarships for Indigenous students were recommended. Participants also stressed the need for a separate admissions process for Indigenous students in pursuit of a graduate degree in PT.

The proposed streaming process included non-exclusionary reserved seating for Indigenous students, provided the minimum admissions requirement was met, and the mandatory addition of Indigenous culture to the interview process through inclusion of a case dealing with either Indigenous issues or an Indigenous evaluator. One participant said,

I think admissions is a small piece of the puzzle—it can tackle disparity that is occurring already in the health care programme, but it can also tackle the cultural sensitivity education piece that needs to be done, and it can bring about diversity within our cohort across the nation. (Participant 8)

This statement demonstrates the many benefits of modifying the current admissions process for Indigenous students entering Canadian PT programmes.

Modifying the university environment and curriculum was considered imperative to diminish the current inequalities and educational disparities between Indigenous students and non-Indigenous students and generally increase the enrolment of Indigenous students in PT programmes. Key strategies identified to facilitate a more inclusive university environment for Indigenous students included adding distinct spaces for students to embrace their culture and traditions and more on-campus supports, such as an Indigenous centre where students would receive culturally appropriate support and care from elders and mentors. Moreover, participants stressed the need for ongoing mandatory Indigenous education throughout the programme, which would include Indigenous guest lecturers, formal education on Indigenous culture, cultural safety training for both university staff and students, problem-based case studies relevant to Indigenous culture or care, practical experience speaking through a translator, and more clinical placements on reserves.

A final strategy was to increase funding for PT on reserves; this would provide job opportunities for graduates so that they could return to their community for work. To help decrease detachment from their rural community and familial responsibilities, Indigenous students would benefit from the creation of rural-based university facilities, laddering programmes such as rehabilitation assistant programmes, and curriculum flexibility in the form of modular-based learning, evening and weekend classes, and part-time PT programmes. In taking Indigenous community and familial responsibilities into account, one participant said that the university would be “making sure the curriculum is relevant to the living circumstances of the people who are enrolled in it” (Participant 10).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate recommendations for increasing the number of Indigenous students in PT programmes in Canada. Our results align with three of the four strategies for optimizing the educational success of Indigenous students proposed by Andersen and colleagues.14 Our participants echoed the importance of engaging Indigenous faculty and staff to recruit Indigenous students, optimizing the inclusion of Indigenous students through modifications to the Westernized university environment, and recognizing the importance of Indigenous centres in higher education. Additional strategies include reserving admission seats and an admissions stream tailored to Indigenous students.18,24

The participants also supported the strategies used by Canadian medical schools to prioritize relationship building with Indigenous communities.18 Finally, our results reinforce the need to financially support Indigenous students, create safe spaces for them on campus, and include Indigenous health issues in the PT curriculum. All of these recommendations were made by the National Aboriginal Health Organization for universities considering the recruitment of Indigenous students into medical programmes.18

Although PT programmes across Canada have begun implementing changes to their admissions programme, such as reserved seating and a streamlined process for Indigenous students, this study identified additional initiatives. For example, participants emphasized how strategies for change should be informed by enhanced insight into the structural challenges in Canadian society, including the legacies of colonization, and a shift in mindset toward including an Indigenous worldview.

How more Indigenous health care professionals can strengthen physical therapy as a profession

The results of this study support increasing the recruitment of Indigenous students into Canadian PT programmes as part of increasing the diversity of the PT profession as a whole. Enhanced diversity can introduce new strengths to the PT community that it may not have realized existed. Increasing the number of Indigenous individuals will integrate Indigenous culture and knowledge into the profession, thereby benefiting the delivery of health care to Indigenous clients. Indigenous practitioners can help to educate other health care professionals trained in a Western model of health care delivery about care that is culturally safe for Indigenous peoples.25

Such a response would support the recognition by the CPA that “physiotherapists who practice in [rural] communities report that they recognize the limitations of ‘western medicine’ and look to Aboriginal leaders and elders for guidance to achieve a more comprehensive approach to care.”2(p. 9),5,26 Despite the conclusion of the CPA’s report on Indigenous peoples’ access to physiotherapy in Canada that PT can contribute to the health care of Indigenous peoples,2 a wide gap exists in the proportion of Indigenous physiotherapists to the number of Indigenous people in Canada. The results of this study provide strategies for increasing the opportunities for Indigenous students to enrol in PT programmes across Canada.

Future directions for policy and education

The results of this study identify strategies for universities to consider to increase enrolment of Indigenous students in their PT programmes. The participants proposed changes to admissions processes, such as reserved seating and a separate admissions stream. Moreover, to integrate Indigenous perspectives on health and rehabilitation into the PT curriculum, universities should consider modifying their curricula and physical environments, hiring more Indigenous staff and faculty members, and creating supports for Indigenous students on campus.

Future directions for research

Current research acknowledges the need, and proposes strategies, for increasing the recruitment of Indigenous students into health care professional programmes such as medicine and nursing; however, there is a gap in the literature regarding strategies for PT.14,15,18,24 Future research should investigate how non-Indigenous PT faculty and clinicians in Canada can increase their awareness of their settler privilege and their “reflexivity” (understanding how their own cultural upbringing influences their worldview and interpreting other’s views on the basis of their cultural backgrounds) and complicity in the structural forces in society that impede Indigenous students’ access to higher education. Future research should also explore the effectiveness of recruitment strategies designed to increase Indigenous students’ enrolment in health care professional programmes.

This study had three limitations. First, all but one of the research team members were non-Indigenous. Increasing the number of Indigenous student PT researchers might have enhanced the group’s insight into this inquiry. Second, all the participants were English speaking, thereby excluding the perspectives of non-English-speaking people. Third, participants were successfully recruited from five different provinces within Canada, but representation from the additional provinces and territories might have enhanced understanding.

Conclussion

In response to Recommendation 23 of the TRC report to increase the number of Indigenous health care providers throughout Canada, in this study we set out to identify the challenges, resulting from the legacy of colonization, that act as key barriers to Indigenous student enrolment in PT programmes. Our analysis identified three interrelated opportunities for PT programmes to meet these challenges: (1) build insight into the legacies of colonization and other structural barriers to Indigenous access to higher education and (2) change thinking from the dominant Western perspective to make room for an Indigenous worldview, which can (3) inform action to increase the enrolment of Indigenous students in PT programmes.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

There is a call to action by the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report for an increased number of Aboriginal professionals working in health care fields.3 Some physiotherapy (PT) programmes in Canada have begun implementing strategies to facilitate the admission of more Indigenous students, such as reserved seats and a streamlined admissions process.19,27 However, there is little consistency among these approaches, and no empirical research in Canada has explored this issue with respect to the PT profession. This suggests a need to revisit and re-examine the current admissions processes to better respond to the TRC report.

What this study adds

This is the first study to provide evidence of the structural considerations of, barriers to, and facilitators of increasing the recruitment of Indigenous students into Canadian PT programmes. It concludes that a paradigm shift is needed whereby PT programmes and the PT profession recognize the limits of their predominantly Eurocentric way of thinking and embrace the sovereignty and self-determination of Indigenous peoples. This enhanced understanding can better inform their actions to increase Indigenous enrolments, such as increasing awareness of PT as a profession among Indigenous high school students, modifying university admissions processes, and modifying the university environment and curriculum to be more inclusive of Indigenous culture and worldviews. These findings may also offer insights into increasing the enrolment of Indigenous students in PT programmes in other countries with similar colonial histories.

References

- 1. Cameron A, Cutean A. Digital Economy Talent Supply: Indigenous Peoples of Canada [Internet]. Ottawa: Information and Communications Technology Council; 2017. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: https://www.ictcctic.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2017/06/Indigenous_Supply_ICTC_FINAL_ENG.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canadian Physiotherapy Association. Access to physiotherapy for Aboriginal peoples in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa: The Association; 2014. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: https://physiotherapy.ca/system/files/advocacy/access-to-physiotherapy-for-aboriginal-peoples-in-canada-april-2014-final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Calls to action [Internet]. Winnipeg: The Commission; 2015. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reading CL, Wien F. Health inequalities and the social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health [Internet]. Prince George (BC): National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2009. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/RPT-HealthInequalities-Reading-Wien-EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fricke M. First Nations people with disabilities: an analysis of service delivery in Manitoba [MSc thesis]. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Statistics Canada. Aboriginal Peoples Survey, 2006: Adults [Internet]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2006. [cited 2018 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/89-637-X. [Google Scholar]

- 7. First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) 2008/10: National report on adults, youth and children living in First Nations communities [Internet]. Akwesasne (ON): FNIGC; 2012. [cited 2018 Apr 29]. Available from: https://fnigc.ca/sites/default/files/docs/first_nations_regional_health_survey_rhs_2008-10_-_national_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coghlan CM, Mallinger H, McFadden A, et al. Demographic characteristics of applicants to, and students of, Ontario physiotherapy education programs, 2004–2014: trends in gender, geographical location, Aboriginal identity, and immigrant status. Physiother Can. 2017;69(1):83–93. 10.3138/ptc.2016-23e. Medline:28154448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Churchill M, Parent-Bergeron M, Smylie J, et al. Evidence brief: wise practices for Indigenous-specific cultural safety training programs [Internet]. Toronto: Well Living House Action Research Centre for Indigenous Infant, Child and Family Health and Wellbeing, St. Michael’s Hospital; 2017. [cited 2018 Apr 30]. Available from: http://www.hnhblhin.on.ca//media/sites/hnhb/Goals%20and%20Achievements/Population%20Based%20Integrations/Aboriginal%20Health/2017%20Wise%20Practices%20in%20Indigenous%20Specific%20Cultural%20Safety%20Training%20Programs.pdf?la=en. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramsden I. M. Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu [dissertation] [Internet]. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington; 2002. [cited 2018 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.nzno.org.nz/Portals/0/Files/Documents/Services/Library/2002%20RAMSDEN%20I%20Cultural%20Safety_Full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Physiotherapy New Zealand. Guidelines for cultural competence in physiotherapy education and practice in Aotearoa/New Zealand [Internet]. Wellington, New Zealand: Physiotherapy New Zealand; 2004. [cited 2018 Sept 21]. Available from: https://docplayer.net/37796914-Guidelines-physiotherapy-nz-guidelines-for-cultural-competence-in-physiotherapy-education-and-practice-in-aotearoa-new-zealand.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Health Council of Canada. Empathy, dignity, and respect Creating cultural safety for Aboriginal people in urban health care [Internet]. Toronto: The Council; 2012. [cited 2018 Apr 30]. Available from: https://healthcouncilcanada.ca/files/Aboriginal_Report_EN_web_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Allan B, Smylie J. First Peoples, second class treatment: the role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada [Internet]. Toronto: Wellesley Institute; 2015. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: http://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Summary-First-Peoples-Second-Class-Treatment-Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andersen C, Bunda T, Walter M. Indigenous higher education: the role of university in releasing the potential. Aust J Indigen Educ. 2008;37(1):1 10.1375/s1326011100000041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meiklejohn B, Wollin JA, Cadet-James Y. Successful completion of the Bachelor of Nursing by Indigenous people. Aust Indigen Health Bullet [serial on the Internet]. 2003. [cited 2017 June 29];3(2):1 Available from: https://researchrepository.griffith.edu.au/bitstream/handle/10072/26863/33558 _1.pdf?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gruenig S. Aboriginal curriculum and admissions in physiotherapy schools in Canada. Physiother Pract. 2015;5(2):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Northern Ontario School of Medicine [homepage on the Internet]; c2018. [cited 2018 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.nosm.ca/education/md-program/admissions/admission-requirements/.

- 18. Hill SM. Best practices to recruit mature Aboriginal students to medicine by the Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada and the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada. Prince George (BC): National Aboriginal Health Association; c2017. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: https://afmc.ca/pdf/IPAC-AFMC_Recruitment_of_Mature_Aboriginal_Students_Eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Master of Physical Therapy Program [Internet]. Saskatoon: University of Saskatchewan; c2017. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: https://medicine.usask.ca/programs/physical-therapy.php. [Google Scholar]

- 20. School of Physical Therapy. Admission and application [Internet]. London (ON): University of Western Ontario; c2017. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: http://www.uwo.ca/fhs/pt/programs/mpt/admission.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tongco DM. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2007;5:147–58. 10.17348/era.5.0.147-158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trotter RI. Qualitative research sample design and sample size: resolving and unresolved issues and inferential imperatives. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):398–400. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.003. Medline:22800684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flicker S, Nixon SA. The DEPICT model for participatory qualitative health promotion research analysis piloted in Canada, Zambia and South Africa. Health Promot Int. 2015(3):616–24. 10.1093/heapro/dat093. Medline:24418997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Akle M, Deschner M, Giroux R, et al. Indigenous Peoples and health in Canadian medical education: CFMS Position Paper [Internet]. Ottawa: Canadian Federation of Medical Students; 2015. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: https://www.cfms.org/files/position-papers/2015_indigenous_people_in_canadian_med_ed.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25. West R, Usher K, Foster K. Increased numbers of Australian Indigenous nurses would make a significant contribution to “closing the gap” in Indigenous health: what is getting in the way? Contemp Nurse. 2010;36(1–2):121–30. 10.5172/conu.2010.36.1-2.121. Medline:21254828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Health Canada. An examination of continuing care requirements in Inuit communities. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2008. [cited 2019 Feb 25]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2009/sc-hc/H34-172-1-2007E.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27. McMaster University School of Rehabilitation Science. McMaster MSc(PT) admissions [Internet]. Hamilton (ON): McMaster University; c2017. [cited 2017 June 29]. Available from: https://srs-mcmaster.ca/pt-admissions/#1535374297083-093d262c-7465. [Google Scholar]