Abstract

Bleeding from traumatic injury is the leading cause of death for young people across the world, but interventions are lacking. While many agents have shown promise in small animal models, translating the work to large animal models has been exceptionally difficult in great part because of infusion-associated complement activation to nanomaterials that leads to cardiopulmonary complications. Unfortunately, this reaction is seen in at least 10% of the population.

We developed intravenously infusible hemostatic nanoparticles that were effective in stopping bleeding and improving survival in rodent models of trauma. To translate this work, we developed a porcine liver injury model. Infusion of the first generation of hemostatic nanoparticles and controls 5 minutes after injury led to massive vasodilation and exsanguination even at extremely low doses. In naïve animals, the physiological changes were consistent with a complement-associated infusion reaction. By tailoring the zeta potential, we were able to engineer a second generation of hemostatic nanoparticles and controls that did not exhibit the complement response at low and moderate doses but did at the highest doses. These second-generation nanoparticles led to cessation of bleeding within 10 minutes of administration even though some signs of vasodilation were still seen. While the complement response is still a challenge, this work is extremely encouraging in that it demonstrates that when the infusion-associated complement response is managed, hemostatic nanoparticles are capable of rapidly stopping bleeding in a large animal model of trauma.

Introduction

Traumatic injury is the leading cause of death for children and adults up to age 46 in the US and worldwide (1–3), and hemorrhage is the primary cause of death both during the pre-hospital and early phases of resuscitation in both military and civilian settings (4–6). Rapid intervention with either mechanical means (e.g. tourniquet application) or hemostatic dressings can improve outcomes in patients with severe hemorrhage (7); however, these interventions are limited to compressible and exposed wounds.

Transfusion of blood products remains the primary treatment beyond surgery for bleeding. Administration of allogeneic platelets can help to halt bleeding; however, platelets have a short shelf life, and administration of allogeneic platelets can cause graft versus host disease, alloimmunization, and transfusion-associated lung injuries (8). Furthermore, in austere environments, the logistics of platelet collection and storage often limit their availability (9). Consequently, platelet substitutes which either replace or augment existing platelets have been pursued for a number of years (8).

The use of drugs including recombinant factor VIIa (NovoSeven) and tranexamic acid were promising in early studies, but recent studies suggest their effectiveness is somewhat limited (10–19). Factor VIIa has fallen out of favor after multiple trials did not show improvements in survival coupled with potential complications (20). Tranexamic acid has shown improvements in survival in the CRASH-2 trial when administered early after trauma (21). Late administration appears to increase mortality, however, and administration does not reduce the need for blood products. Fibrinogen and prothrombin complex concentrates (PCC) have drawn significant interest as potential treatments for trauma induced coagulopathy (TIC). Fibrinogen levels are depleted during trauma (22, 23), and studies suggest that signs of coagulopathy are reversed with fibrinogen therapy (24–26). Transfusion of plasma and platelets does not increase fibrinogen levels, but transfusion with cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen does (22). While the studies looking at fibrinogen transfusion are relatively small, they have been promising. Nonetheless, there are potential challenges with fibrinogen therapy. The most notable ones are the issues regarding changes in blood viscosity that may increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (25, 27, 28), the lack of thermal stability of the molecule, the risk associated with administration of a blood-product derivative, and the expense of fibrinogen concentrate (29). Fibrinogen concentrate is estimated to be approximately $6000 per dose, which most hospitals have said is prohibitive based on the current outcomes (29). In the economic study, hospitals cite a price point of $2000–3000 being more realistic, particularly if outcomes are better and subsequent costs are reduced.

The risks and limitations of the current treatments for acutely bleeding patients have motivated significant interest in developing alternative hemostatic agents. An early approach coated albumin particles with fibrinogen (30). These particles reduced bleeding in an in vivo ear injury model in thrombocytopenic rabbit, but the particles were inflexible and large (3.5–4.5 um in diameter) which leads to accumulation in the capillary beds of the lungs (31). More recent approaches focused on smaller or more flexible particles. Liposomes carrying the fibrinogen γ chain dodecapeptide (HHLGGAKQAGDV) reduced bleeding in thrombocytopenic rats and rabbits compared with saline (32, 33). Liposomes with multiple targeting ligands for the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor as well as von Willebrand factor have been pursued to bind to both activated platelets as well as walls of the vessels following injury (34). Early in vivo data suggests the particles reduce bleeding (35). However, longer peptides and more peptides are more complicated and may exhibit off-target effects. Polyphosphate or polyP, secreted by activated platelets, facilitates activation of clotting factors and reduces fibrinolysis. Silica nanoparticles (~50 nm) functionalized with polyP have been shown to reduce clotting time using in vitro methods (36). The particles have also reduced bleeding time in a tail vein model (37). A creative approach to creating a contracting platelet-like particle based on a hydrogel system has shown promise in models of bleeding (38). These particles are highly deformable, and contract under stress to mimic the platelet response. Most of the nanoparticle formulations have focused on reducing the time to initial clot formation. However, stabilization of clot formation is critical. One nanoformulation that is entirely based on this is polySTAT (39). This polymer works by crosslinking fibrin and stabilizing clots. It has been shown to reduce bleeding in models of injury and may be able to work in concert with other approaches to further reduce bleeding. Most nanoparticle systems rely on intravenous administration. However, one uses a reaction between carbonate and TXA to create CO2 to propel nanoparticles through flowing blood to injury sites. The particles reduce bleeding in a number of models of trauma (40–42).

Overall, there are many elegant emerging approaches to the challenge of hemorrhage control. Our approach focuses on a simple mimic of fibrinogen. We have developing nanoparticles that are administered intravenously and halve bleeding time in a femoral artery injury model (43). We have also shown that these hemostatic nanoparticles can significantly improve survival following a blunt liver injury in rodents (44, 45) as well as improve survival in both the short (1 hour) and long term (3 weeks) following blast trauma (46). However, the transition to large animal models, and, ultimately, the potential for clinical application is fundamentally limited by the infusion reaction associated with intravenously administered nanomaterials.

Intravenously administered nanomaterials trigger complement activation related pseudoallergy (CARPA) in both pigs and humans (47–49). While rodents have a complement response to nanomaterials, it is so mild compared to the porcine and human responses that the CARPA response is generally not considered in this context (50). In humans, Doxil, the PEGylated liposomal formulation of doxorubicin, triggers mild to severe cardiopulmonary responses in patients that disappear over several infusions in a process of self-induced tolerance called tachyphylaxis (51). This infusion-associated complement response is not limited to just nanomaterials. It has been seen with the administration of cellular therapies and biologics as well (52).

The solution, traditionally, is to administer the liposomes at extremely slow rates (1 mg/min) along with drugs to treat the cardiopulmonary responses (53). However, a slow infusion is not practical for a hemostatic agent because the patient could bleed out before the particles arrive. Thus, an alternative particle that promotes hemostasis while avoiding or mitigating this complement reaction during infusion is critical.

The complement issue was first well mapped out in the porcine and human systems by Szebeni and his colleagues (47–49). In the last few years, several approaches have been developed to try and characterize and reduce this response. Wibroe et al. found that the shape of the particles impacted the infusion reaction and that coupling particles to red blood cells could reduce the response further (54). Several groups have cloaked nanoparticles with components of blood cells to reduce complement activation (55–58). Glycopolymers have also been used in place of PEG-based coronas to reduce complement activation although they bring their own challenges with nanoparticles (59–61). For PEG-based systems, the density and organization of PEG matters (62). The zeta potential also plays a role (47).

Based on these observations, we sought to explore whether simple modifications to the hemostatic nanoparticles would mitigate the infusion reaction and preserve the hemostatic function in a large animal model of trauma. We investigated the role of zeta potential, excipients, and dosing on bleeding and physiological parameters in a porcine model of blunt liver injury. We examined the impact of the infusion reaction on bleeding, developed a formulation with a limited reaction at all but the highest doses, and determined a range of doses of hemostatic nanoparticles that can stop bleeding in a large animal model of blunt trauma. We believe this work marks an important foundation for developing new hemostatic agents for translation to the clinic.

Results

Design of hemostatic nanoparticles

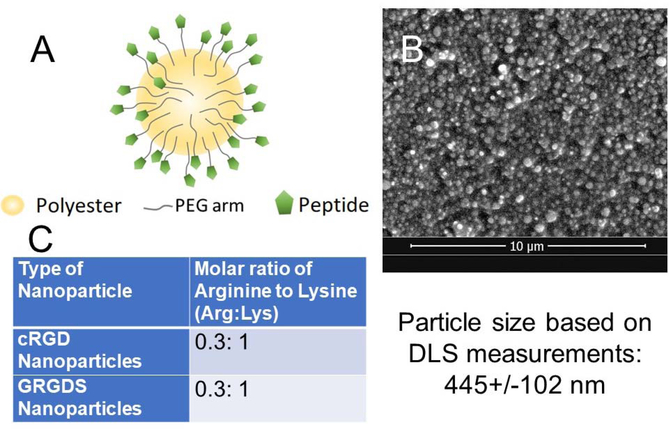

Two generations of nanoparticles were used for this study. The first generation of hemostatic nanoparticles consist of a 400–500nm poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-block-polylysine (PLGA-PLL) core with poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) arms functionalized with RGD moieties (Fig 1A). Core diameter and nanoparticle charge were determined with dynamic light scattering (DLS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). These PLGA-based hemostatic nanoparticles (hNPs) were positively charged (zeta potential ~23–25 mV) due to the presence of PLL. PLA-PEG nanoparticles of the same size but with a zeta potential of −30 mV were used as negatively charged controls. Both the PLGA-based and PLA-based nanoparticles had the same degree of PEGylation as determined by comparing NMR in deuterated water to NMR in deuterated chloroform with approximately 10–15% of the polyesters having a PEG consistent with our previous work (44, 45). The second-generation nanoparticles (hNPs*) were based on PLGA-PLL-PEG with cRGD in place of GRGDS to make particles with a neutral zeta potential. For this work, we defined neutral particles as those with zeta potential between −3 and 3 mV.

Figure 1:

Characteristics of nanoparticles used in this study. (A) Schematic of the nanoparticles. All of the nanoparticles consisted of a polyester degradable core (either PLGA-PLL or PLA) with PEG arms (Mn~4600 Da). The hemostatic nanoparticles all had an RGD peptide (either GRGDS or cRGD. The control nanoparticles in the study all had no peptide. (B) Representative scanning electron micrograph of hemostatic nanoparticles. DLS confirmed that the size was approximately 445+/−102 nm for all of the particles used in the study unless otherwise noted. (C) The peptide density was determined as a function of peptide per lysine unit and was 0.3 peptides per lysine.

In vivo Porcine Liver Injury Model

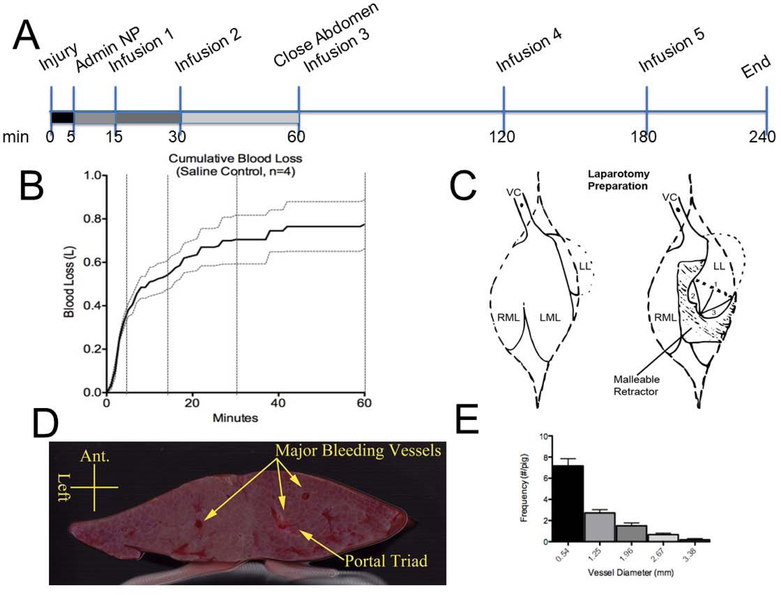

The porcine liver injury model is one of the critical preclinical models for translation of trauma treatments. We used this model to investigate the impact of the different generations on hemostatic nanoparticles or controls on bleeding and survival following injury. The injury was performed at 0 minutes. The animal was allowed to bleed freely for 5 minutes, at which point treatment was introduced via a catheter placed in the jugular vein. Saline infusions were administered at 15, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes post-injury (Figure 2A). Animals were sacrificed at 240 minutes post injury via pentobarbital overdose.

Figure 2:

(A) Timeline of the injury and treatment. (B) Blood loss over 60 minutes with saline infusions at 15, 30 and 60 minutes. The dotted lines represent the SE for each timepoint (n=4). (C) Schematic of the injury. The left lobe (LL) is isolated from the underlying anatomy and medial lobe (left LML; right RML) with a malleable retractor and measured and marked with cautery 2” from the apex (1). Two additional measurements are made from the apex to the lateral aspects of the resection line to ensure consistent equilateral angles (2 & 3). Ring clamps are used to hold the liver while the injury is made. The liver is resected to the left lobe midline (1), starting from patient---right. This is allowed to bleed for 1 minute with ring clamps still holding proximal to the injury line, and then the remaining liver is cut. After the injury is made, the left lobe is placed back in its natural resting place to prevent alteration of normal hepatic blood flow. VC=hepatic inferior vena cava. (D) Cross section of a resected section of the liver lobe showing the major vessels. (E) Quantification of vessel diameters at surface of resected liver

To validate the model, we tested the model using saline (30 ml). Preadministration blood loss (0–5 minutes) is highly dependent on the injury. Tightly standardizing the injury and using ring clamps is critical, but due to the variability in animals in the 0–5 minute window, for treatments, it was helpful to consider blood loss curves for individual subjects.

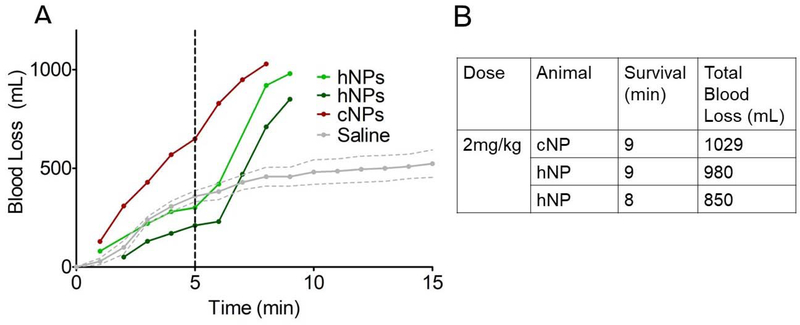

First Generation Hemostatic Nanoparticles: Massive Exsanguination in Liver Trauma model

Based on the successful dose of hemostatic nanoparticles in the rodent liver injury model (5 mg/kg) (45), we decided to start our dosing study at 2 mg/kg in the porcine model, a conservative dose with the expectation that we would increase the dose to an effective dose. Intravenous administration of either the hemostatic nanoparticles (hNPs) or control nanoparticles (PLGA-PLL-PEG particles without peptide; cNPs) at a dose of 2 mg/kg led to exsanguination (Figure 3A) and death within minutes of administration (Figure 3B).

Figure 3:

Injury at time=0. Particles were administered at time= 5min. (A) 2 mg/kg of hemostatic nanoparticles or control nanoparticles triggered vasodilation and bleed out within minutes of administration leading to death. (B) Table summarizing survival time and total blood loss for the first-generation nanoparticle group at 2 mg/kg. In contrast, the saline group (n=4) survived for the entire experiment with an average blood loss of 722+/−106 ml.

Both the control and the hemostatic nanoparticle animals exhibited this rapid exsanguination. We reduced the dose by tenfold to 0.2 mg/kg and repeated the experiment. At a dose of 0.2 mg/kg, we still saw an increase in bleeding rate upon administration of either the treatment or control nanoparticles (Supplementary figure 1A). We reduced the dose one more time to 0.03 mg/kg and saw a modest increase in bleeding in both compared to the saline control (Supplementary figure 1B). While reducing the dose limits the increase in bleeding following administration, the 0.03 mg/kg dose is so exceptionally low that it is not surprising that there are no signs of hemostatic effect.

In light of this rapid bleed out following particle administration, we wanted to look at the physiological parameters before and after particle administration. To that end, we administered the particles in naïve pigs.

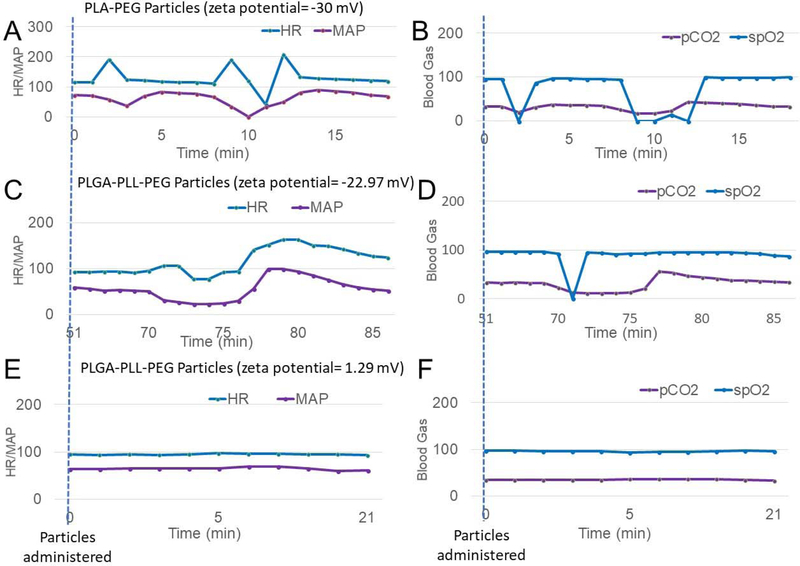

Naïve Administration Model

The naïve administration model was used to investigate the influence of excipient and nanoparticle zeta potential (−30.04mV, neutral, and +22.97mV) on cardiopulmonary data in the absence of an injury. Two doses were given to each pig. Because repeated administrations can reduce the physiological response to nanoparticles, the treatment hypothesized to give the least response was always given first. Pig 1 received a 60mg dose (2 mg/kg) of PLA-PEG nanoparticles (zeta potential = −30.04 mV) at 0 minutes. An hour later, the same animal received 60mg of PLA-PEG nanoparticles (zeta potential=−31.64 mV). Both administrations led to significant physiological responses with the heart rate, blood pressure, and blood gases changing rapidly upon administration of the particles. The first administration (2 mg/kg of PLA-PEG nanoparticles, zeta potential of −30.04 mV) led to the physiological changes seen in Figure 4A and 4B. The second dose replicated the overall response.

Figure 4:

No injury was performed. (A and B) 2 mg/kg PLA-PEG Nanoparticles (Zeta potential = −30 mV) were administered at time=0 minutes. Within 2 minutes the heartrate and blood pressure changed dramatically followed by a subsequent spike at t=8–12 minutes. (B) The blood gases also showed the same dramatic changes over the same time period. This is consistent with what has been seen by others following nanoparticle administration (48, 63, 64). (C and D) 2 mg/kg of PLGA-PLL-PEG Nanoparticles (Zeta = 22.97 mV) were administered at time=68 minutes. These positively charged particles led to a similar response as in A and B. (E and F) 2 mg/kg of PLGA-PLL-PEG Nanoparticles, (Zeta = 1.29 mV) were administered at time=0 minutes and did not show signs of these physiological responses.

Pig 2 was given 60 mg of +1.29mV PLGA-PEG nanoparticles at 0 minutes (Figure 4E and F) and 22.97mV PLGA-PEG NPs at 65 minutes (Figure 4C and D). Even though the PLA-PEG nanoparticles were given in the second dose when the complement associated response is generally reduced (65), the pig showed a strong complement associated response with rapid changes in the heart rate and blood pressure (Figure 4C) as well as blood gases (Figure 4D). However, the first administration in that pig of the neutral particles (60 mg of +1.29mV PLGA-PEG nanoparticles) did not show physiological changes (Figure 4E and F). Based on these findings, we sought to design a new generation of hemostatic nanoparticles with zeta potentials close to neutral.

Nanoparticles with Neutral Surface Charge

To make neutral particles, we used the PLGA-based nanoparticles with the cRGD peptide in place of GRGDS peptide. The GRGDS targeting ligand is inherently negatively charged due to the presence of Arg (+), Asp (−) and the carboxylic acid terminus (−). The cyclic RGD, cRGD has both a higher specificity for activated platelet GPIIb/IIIa and a net neutral charge (66). Thus, it was easier to tailor hemostatic particles to be neutral with the addition of the cRGD peptide. One of the challenges of making neutral particles is that even when highly PEGylated, they have a propensity for aggregation. Therefore, we investigated the impact of excipients on the infusion response. While poly(vinyl alcohol) triggers an infusion response (Supplementary figure 2 and supplementary figure 3A), poloxamer 188 does not (supplementary figure 3B and supplementary figure 4). Therefore, we focused on the addition of poloxamer 188 to the hemostatic nanoparticles and controls to facilitate resuspension and administration.

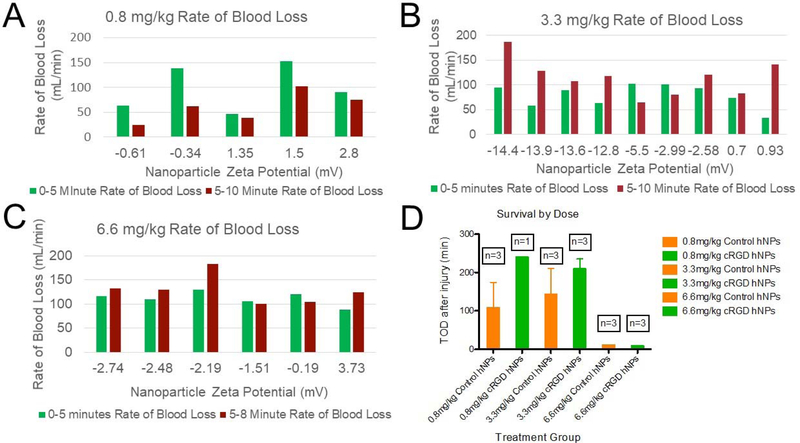

With the observation that particles with a near-neutral zeta potential did not show physiological changes consistent with an infusion response following administration in naïve pigs (Figure 4E and 4F), we focused on the relationship between bleeding and zeta potential as a function of dose in the injury model. All of the hemostatic nanoparticles were fabricated with the cRGD peptide, and the control nanoparticles did not have any peptide. The treatments were administered 5 minutes after the injury was made Thus, in figure 5, the green bars represent the rate of blood loss as a function of injury and the red bars represent the rate of blood loss in the window after the particle administration.

Figure 5:

Second generation hemostatic nanoparticles. (A) At the lowest dose, 0.8 mg/kg, all of the zeta potentials for nanoparticles did not increase the bleeding rate following administration. The zeta potentials in (A) represent the particles we designated as neutral with −3mV<neutral<3mV. (B) At the next highest dose, 3.3 mg/kg particles with a greater zeta potential led to an increase in bleeding. The notable exception is the particles with a zeta potential of 0.93 mV. While the standard deviation for most particles was less than 1 mV, these particles exhibited a standard deviation of 2.45 mV, suggesting that the particles had a wide range of charges. (C) At the highest dose studied, 6.6 mg/kg, all of the particles, independent of zeta potential led to some increase in bleeding, albeit far smaller than seen with the first-generation nanoparticles. (D) The majority of the animals at the two lowest doses exhibited long term survival that varied between the control and hemostatic nanoparticle groups. At the highest dose, 6.6 mg/kg rapid exsanguination led to death in both the control and hemostatic nanoparticle groups. The average rate of blood loss for saline was 72 ml/min for 0–5 minutes and 25 ml/min for 5–10 minutes.

At the lowest dose, 0.8 mg/kg, the hemostatic nanoparticles and control nanoparticles exhibited a lower rate of blood loss post administration than preadministration independent of zeta potential over the range of −0.61 mV to 2.8 mV (Figure 5A). At the next dose tested, 3.3 mg/kg, bleeding did increase following particle administration, particularly in the more highly charged particles (Figure 5B). One outlier was a near neutral set of particles with a zeta potential of 0.93 mV and a standard deviation of 2.45 mV. This standard deviation was far larger than that for the other nanoparticles where the standard deviation was 1 mV or less. The large variation in zeta potential may have led to a charged subset that exacerbated bleeding. At the highest dose, 6.6 mg/kg, all of the particles, regardless of zeta potential, increased bleeding (Figure 5C).

While these particles did lead to increases in bleeding at the highest doses tested, at the low and medium doses, the increase was limited enough that the survival was extended to the end of the study in the majority of animals (Figure 5D). The highest dose of particles at 6.6 mg/kg led to rapid onset of exsanguination and death (Figure 5D). The more limited response to the infusion and increased survival in the low and medium dose groups allowed us to look at whether the hemostatic particles were able to induce hemostasis in this large animal model of trauma.

Since particles that were more highly charged tended to trigger increased vasodilation, we focused on bleeding in the particles with zeta potentials between −3 and 3 mV. With more neutral nanoparticles, our second-generation system, we hoped to be able to see if there was a hemostatic component to these nanoparticles in the large animal model of trauma in spite of the potential component of infusion-triggered vasodilation.

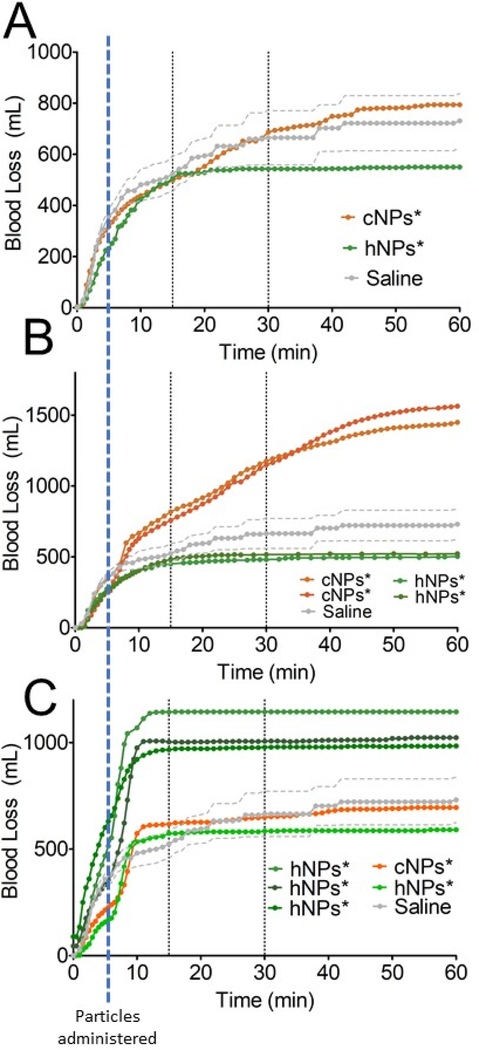

Remarkably, there is a difference between the second-generation hemostatic nanoparticles, hNPs* and controls. At three of the four doses studied, 0.8, 2, and 3.3 mg/kg, administration of the hemostatic nanoparticles triggered hemostasis by the 15-minute mark, even in cases where the administration of the particles leads to some increase in bleeding (as seen in the 2 mg/kg dose (Supplementary figure 6 and the 3.3 mg/kg dose).

In the lowest dose group, 0.8 mg/kg, the hemostatic nanoparticles lead to hemostasis at 15 minutes post injury (Figure 6A, n=1). In the 2 mg/kg group, the hemostatic nanoparticles lead to hemostasis at 15 minutes in all 3 of the animals tested (Figure 6B). In the 3.3 mg/kg group, the hemostatic nanoparticles lead to hemostasis at 15 minutes in all of the animals (Figure 6C) (n=4).

Figure 6:

The impact of the second-generation hemostatic nanoparticle (hNPs*) and control nanoparticles (cNPs*) on bleeding over the first 60 minutes following the liver injury model. The particles were delivered five minutes after the injury was made (at time=5 minutes in each graph). All the nanoparticles included in this data had reproducible zeta potentials between −3 and 3 mV with small standard deviations. (A) 0.8 mg/kg dose (B) 2 mg/kg dose (C) 3.3 mg/kg dose

At the highest dose tested, 6.6 mg/kg, both the hNPs* and cNPs* led to substantial increases in bleeding, exsanguination, and death. Nonetheless, at moderate doses, the hemostatic effect of the nanoparticles can be seen in this large animal model of trauma.

The role of complement in the infusion reaction

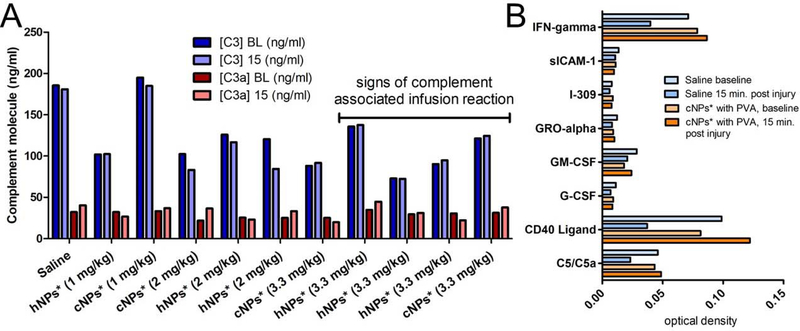

One would be remiss to engineer materials that modulate the complement response without looking at markers of complement activation. Since nanomaterials generally trigger complement activation via the alternative pathway, we focused on C3 and C3a, particularly since C3a is a potent vasodilator.

In figure 7A, one can see the concentration of C3 and C3a at baseline and 15 minutes post injury. The concentrations are essentially identical. Typically, a 2–4-fold change in complement molecules is noted as likely to trigger cardiac and pulmonary responses (48, 67). However, a subset of the animals showed signs of complement activation including vasodilation and modest changes in the physiological parameters within minutes of the infusion. For two of the animals, a saline animal, and one that had signs of vasodilation following particle administration (supplementary figure 5), we used a cytokine array to screen for differences. We did seen changes in C5a as well as several other molecules between the saline and cNP*-treated animal that suggest that a more complete picture of the molecular changes in the blood is needed to assess complement activation.

Figure 7:

(A) Complement response as measured by changes in C3 and C3a between baseline (BL) and 15 minutes post injury. These data would suggest that the particles do not activate complement, yet in a subset, marked by the line, we see signs of the complement associated infusion reaction marked by vasodilation and small changes in the physiological parameters. (B) A cytokine array panel on serum from baseline and 15 minutes post injury in an infusion suggests that the impact of particle may be better understood through looking at different molecules. The cNPs* were given at a 0.2 mg/kg dose and the presence of PVA was, ultimately, identified as a trigger for the infusion-associated complement reaction.

Discussion

It is certainly unexpected when one is designing and testing hemostatic agents to find that they trigger massive exsanguination. The most important clues to the underlying cause were the rapid changes in physiological data in the naïve, uninjured pigs. The rapid changes in blood gases, blood pressure, and heart rate are consistent with the data published by Szebeni and his colleagues over the last twenty years (68–71). They showed that intravenous administration of nanomaterials led to can lead to difficulty breathing, arrhythmia, tachycardia, leukopenia, and that the symptoms can start within 3 minutes of the infusion but subside within an hour in pigs (72). These phenomena happen in the vast majority of pigs, and in at least 10% of humans (73).

One of the limitations of this work is the small animal numbers. We used Yorkshire pigs (29–35 kg) in this work. This is an outbred strain, and, as such, they are more variable than inbred rodent strains which we used previously. Even in the simple case of saline administration (Figure 2B), there is notable variation in the cumulative blood loss over time. The administration of nanomaterials, both the first and second generation, has the potential to add a layer of complexity. Ultimately, variability in the model may be a good thing for increasing the reproducibility of work (74, 75), but it raises important questions about how to deal with the distribution of responses and determine whether an intervention has promise.

One solution would be to increase the power of the studies. In the case of a negative finding, such as exsanguination, that would seem unwise. In the case where promising results are seen such as in figure 6, there are still signs of infusion-related increases in bleeding in response to the nanoparticles. To deal with this, we would require a tremendous number of animals to be able to fully power a study for rigorous statistics. However, this seems both ethically and economically challenging, particularly when the data suggests that further development is needed to deal with the infusion response at the highest doses. One question that is important to ask is can one learn something from a small number of large animals. We believe that this work suggests that if one looks at the data carefully, much can be determined. In part, to facilitate this, we have sought to present the data as completely as possible and avoided averaging groups and processing the data. Rather, we have presented the data regarding the bleeding following injury and the physiological data as individual responses from the pigs.

Intravenous infusion of nanomaterials triggers complement activation which, in turn, triggers the complement activation related pseudoallergy (CARPA) response. Nanomaterials tend to trigger complement activation via the alternative pathway (59, 76, 77). Since the alternative pathway involves interactions at surfaces, perhaps it is not surprising that nanomaterials, with their extremely high surface areas, would trigger such a response. Assuming one infuses just 2 mg of polymeric nanoparticles with diameters of approximately 400 nm, one is infusing material with a surface area on the order of 300 cm2 of surface area which is an incredible amount of surface area delivered to a small space in a bolus infusion. Altering the surface of the material to reduce the surface interactions is one important area of research.

PEGylation has been studied to reduce complement activation and the density is very important (62). In the particles used in our work, we obtain approximately 10% of polymer has PEG, and the vast majority is at the surface based on NMR analysis in deuterated chloroform versus deuterated water (44, 45, 78, 79). Zeta potential, a proxy for surface charge, impacts complement activation (50, 80, 81). We focused on modulating zeta potential in this work because it was the simplest way to try to modulate the complement response without significantly changing the design of the nanoparticles.

Based on our results here, we are still seeing a modest CARPA response at the 3.3 mg/kg dose and a significant response at the 6.6 mg/kg dose. If complement is activated, C3 will go down after nanoparticle activation, and C3a and C5a concentrations will increase. We do not see changes in C3 and C3a in the animals, even with signs of the CARPA response, but this is not surprising. It has been that the time course of production and consumption of complement molecules makes it difficult to assay activation in vivo (48) and thus, the physiological response is a far better indicator than the molecules (48). We do see changes in C5a, so this may be worth pursing in the future along with SC5b-9. Nonetheless, the physiological response in the pig is a far more robust indicator for whether or not a nanomaterial triggers CARPA than the complement assays (52).

One of the important things to remember is that this infusion-associated complement response is not limited to nanomaterials. It has been seen with the administration of cellular therapies and biologics as well (52). Many of the critical, cutting edge therapies being developed could trigger this response, and thus it is critical that we acknowledge and deal with the challenge.

To that end, it is clear that we need to do more to make these hemostatic nanoparticles avoid complement activation. While it is tremendously exciting that these particles do trigger hemostasis following administration in this large animal model, they are doing so despite triggering at least a modest CARPA response at the higher doses. If this is a technology that could be administered in the field, it will be important to avoid activating complement at a wide range of doses.

There are several potential directions to pursue to further mitigate the CARPA response. While the chemistry can be more difficult, using glycopolymers in place of PEG has shown promise (59–61). The shape of the particles may also play a critical role in modulating complement activation (54). Cloaking nanoparticles with cellular components may also reduce complement activation (55–58). Complement inhibitors such as antibodies to complement molecules and compstatin are very attractive, but many of these molecules are only reactive with human and nonhuman primate (82, 83). In porcine models, one must focus on inhibitors such as antibodies and cleavage disruptors that are active in the pig (84–87) which makes translation, perhaps, more challenging but possible.

In light of the challenges, it is exciting that there are routes to engineering the hemostatic nanoparticles to reduce the complement response to the point of preserving the hemostatic behavior of the particles. We have shown that these hemostatic nanoparticles work by interacting with the activated glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor on activated platelets (79). It is striking that a very simple design, a polyester core with a PEG corona and RGD-based peptides can have a hemostatic response in a large animal model of trauma. This work provides the motivation to pursue more complex polytraumas with complications like traumatic induced coagulopathy to determine whether these particles could be beneficial as part of a transfusion protocol.

Before that can happen, though, we will need to further address complement. It is even more important since trauma can induce complement activation (88, 89), and it is further exacerbated in hemorrhagic shock-induced sepsis (90–92).

Conclusions

In spite of the challenges associated with complement activation in the porcine model of trauma, we have developed a generation of hemostatic nanoparticles that lead to complete cessation of bleeding within 10 minutes of administration. The ability to rapidly trigger hemostasis in a large animal model of trauma with substantial bleeding is a critical step in developing and translating intravenously infusible hemostatic technologies.

Materials and Methods

Materials

PLGA (Resomer 503H) was purchased from Evonik Industries. Poly-l-lysine was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. PEG (4600 Da) was purchased from Laysan Biosciences. Peptides, including cRGDfK, GRGDS, and GRADSP were purchased from Anaspec. All other reagents were ACS grade and purchased from Fisher Scientific.

Nanoparticle Synthesis and Characterization

Polymer synthesis

PLGA-PLL-PEG was synthesized following our previous work (45). Briefly, PLGA-PLL-PEG triblock polymer was synthesized using stepwise conjugation reactions, starting with PLGA (Resomer 503H) and poly(ε-cbz-L-lysine) (PLL-cbz) PLL with carbobenzoxy-protected side amine side groups (Sigma P4510) as previously described (43, 93). This conjugation reaction was confirmed using UV-Vis to check for a signature triple peak corresponding to the cbz groups. After deprotecting the PLGA-PLL-cbz with HBr, the free amines on the PLL-NH3 were reacted with CDI-activated PEG in a 5:1 molar excess (94). PLA-PEG was synthesized following Conner et al (95) via ring opening polymerization catalyzed by Imes.

Peptide Conjugation

The peptide was coupled to the polymer via CDI on the PEG. PLGA-PLL-PEG (1g) that had been activated with CDI (above) was dissolved in DMSO to create a solution with a concentration of 100 mg/mL. Then, 25mg of GRGDS, GRADSP, or cRGD was dissolved in 1mL of DMSO and added to the PLGA-PLL-PEG/DMSO solution while stirring. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 3 hours, after which the resulting solution was dialyzed (SpectraPor 2 kDa MWCO) for 4 hours with water changes every half hour. The mixture was subsequently frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized for 2–5 days. This conjugation yields the quadblock copolymer PLGA-PLL-PEG-peptide.

Nanoparticle Fabrication

The quadblock polymer (PLGA-PLL-PEG-peptide) or triblock polymer (PLGA-PLL-PEG) was dissolved in acetonitrile at a concentration of 10 mg/ml (w/v) in 6 ml of ACN. The solution was added dropwise to 12 ml of MilliQ water to trigger nanoprecipitation. This emulsion was then added to 35 ml of MilliQ water. For charged particles, 35 ml more of MilliQ water was added and the particles were allowed to harden for 1–2 hours. For neutral particles, 35 ml of 5% poloxamer 188 in MilliQ water was added and the particles were allowed to harden for 1–2 hours. The solution was then dialyzed for 1.5 hours using 2000 MWCO tubing to remove any uncoupled peptide before snap freezing and lyophilizing.

PLA-PEG nanoparticles, used as controls for the naïve pig administration work, were fabricated by dissolving PLA and PLA-PEG at a 3:1 ratio in THF at 20mg/ml. This solution was added dropwise to a stirring solution of PBS twice the volume of the THF. Nanoparticles formed as the water miscible solvent dissipated within the PBS. After stirring for 1 hour, poloxamer was added to the solution in a 1:1 weight ratio to the PLA/PLA-PEG. The nanoparticle solution was then dialyzed to remove residual solvent, snap frozen, and lyophilized.

Nanoparticle Characterization

Nanoparticle size distribution and surface charge for GRGDS and GRADSP nanoparticles were characterized using dynamic light scattering initially (90Plus, Brookhaven Instruments Corporation). Scanning electron microscopy (JEOL 5600) was used to determine nanoparticle polydispersity for PLA-PEG-PLL nanoparticles. Peptide, PEG, and PLL conjugation to PLGA was confirmed using UV spectroscopy (BioRad), 1H-NMR (Varian) and amino acid analysis (Shimadzu) using high performance liquid chromatography Amino acid analysis was performed following our previous work (45). The arg:lys ratio was measured to determine conjugation efficiency. Briefly, a 5 mg aliquot of polymer was hydrolyzed for 24 h in a hydrolysis/derivatization workstation (Eldex Laboratories, Inc., Napa, CA). The hydrolysate was then neutralized with a redrying solution (ethanol: water: triethylamine in a 2:2:1 ratio) and derivatized with 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate, using the Water’s AccQ-Tag system. These samples were run on an HPLC (Shimadzu, with Water’s PicoTag Column) and measured using a fluorescence detector. Standard addition of known quantities of arg and lys to hydrolyzed samples was used to correct for polymer hydrolysate background.

Porcine Liver Injury

Yorkshire pigs (29kg – 35kg) were used in accordance with animal protocols reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Case Western Reserve University. The protocols were developed by Gurney et al (96) and modified in conjunction with the Trauma Research Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital. The pigs were anesthetized with 6–8mg/kg of telazolol, after which they were intubated and placed on a ventilator. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (2–2.5%). A catheter attached to a pressure transducer was inserted into the carotid vein to monitor blood pressure: the internal jugular vein was also catheterized for drug and saline administration. A reproducible injury was created by resecting the left lobe of the liver 2” from its apex using a #15 scalpel blade. The left lobe was isolated using a malleable retractor and held in place with ring clamps for the duration of the injury. Treatments were administered 5 minutes after injury and include saline (30 ml, n=4), GRADSP nanoparticles (cNPs, n=8) GRGDS nanoparticles (hNPs, n=7), cRGD nanoparticles (hNP*, n=9), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, n=2) and poloxamer (n=3). Four different doses of the first generation cNPs and hNPs were delivered: 0.03 mg/kg, 0.1 mg/kg, 0.2 mg/kg, and 2 mg/kg. Four doses of the second generation triblock (PLGA-PLL-PEG; cNPs*) and cRGD (hNPs*, PLGA-PLL-PEG-cRGD) nanoparticles were administered: 0.8 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg, 3.3 mg/kg, and 6.6 mg/kg. All treatments were administered in 30 ml of saline.

Saline infusions were given at 15 minutes (10 ml/kg over 10 minutes), as well as 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes (5 ml/kg over 10 minutes). Blood samples were collected from the carotid artery at baseline, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, and 240 minutes after injury. Physiological data collected include blood loss, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), and partial pressure of CO2 at the end of an exhaled breath or end tidal CO2 (ETCO2). The duration of the study was from time of injury to death, or 4 hours after injury at which point the animal was euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital.

Naïve Administration Model

A naïve administration model was used to evaluate the effect of the nanoparticles in the absence of an injury (A naïve administration model was developed to evaluate the effects of PLA-PEG and PLGA-PEG nanoparticles in the absence of an injury). Catheters were placed in the carotid artery and jugular vein to allow for blood pressure monitoring, drug and lactated ringer infusions, and the collection of arterial blood samples. 2mg/kg of the prescribed nanoparticles was administered at time point 0. Heart rate mean arterial pressure, and blood gas were monitored for 1 hour following nanoparticle infusion. After 1 hour, a second bolus of nanoparticles was injected, and the monitoring steps described above were repeated. Two pigs were used in this experiment, with each pig receiving a total of two treatments.

Assessment of Complement Response in Vivo

Blood samples were collected prior to injury at 15 minutes post injury in citrated tubes. Samples were centrifuged, and the plasma was collected and frozen until analysis could be performed. The plasma samples were analyzed using either ELISA kits to C3 and C3a (Abcam ab157705 and ab133037, respectively) or using a human cytokine array panel (R and D Systems, catalogue number ARY005). For the cytokine array panel, we switched out the streptavidin-HRP for streptavidin-AP and used DAB as the substrate (Vector Labs). The dots were quantified using ImageJ on scanned images of the arrays.

Statistics

Because there was such variability in the overall response of the pigs to the nanoparticles, we have not grouped the animals with regards to physiological response or bleeding for the administration of the nanoparticles. All other data is presented as average+/−SD unless otherwise noted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Navy Contract, N62645-12-C04055, and NIH Director’s New Innovator Award Grant, DP20D007338. Ms. Onwukwe was supported in part by an NIH/NIGMS MARC U*STAR T34 12463 National Research Service Award to UMBC.

Footnotes

The supporting information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

References

- (1).Krug EG, Sharma GK, and Lozano R (2000) The global burden of injuries. The American Journal of Public Health 90, 523–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Rhee P, Joseph B, Pandit V, Aziz H, Vercruysse G, Kulvatunyou N, and Friese RS (2014) Increasing trauma deaths in the United States. Ann Surg 260, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Committee on Military Trauma Care’s Learning Health, S., Its Translation to the Civilian, S., Board on Health Sciences, P., Board on the Health of Select, P., Health, Medicine, D., National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine (2016) A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury, National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2016 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved., Washington (DC). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, Moser KS, Brennan R, Read RA, and Pons PT (1995) Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment. Journal Of Trauma‐injury Infection And Critical Care 38, 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Champion HR, Bellamy RF, Roberts CP, and Leppaniemi A (2003) A profile of combat injury. Journal Of Trauma‐injury Infection And Critical Care 54, 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Eastridge BJ, Mabry RL, Seguin P, Cantrell J, Tops T, Uribe P, Mallett O, Zubko T, Oetjen‐Gerdes L, Rasmussen TE, et al. (2012) Death on the battlefield (20012011): implications for the future of combat casualty care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 73, S431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Regel G, Stalp M, Lehmann U, and Seekamp A (1997) Prehospital care, importance of early intervention on outcome. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. Supplementum 110, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Blajchman MA (1999) Substitutes for success. Nat Med 5, 17–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Spinella PC, Dunne J, Beilman GJ, O’Connell RJ, Borgman MA, Cap AP, and Rentas F (2012) Constant challenges and evolution of US military transfusion medicine and blood operations in combat. Transfusion 52, 1146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Stein DM, and Dutton RP (2004) Uses of recombinant factor VIIa in trauma. Current opinion in critical care 10, 520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kembro RJ, Horton JD, and Wagner M (2008) Use of Recombinant Factor VIIa in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom ‐ Survey of Army Surgeons. Military Medicine 173, 1057–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Benharash P, Bongard F, and Putnam B (2005) Use of recombinant factor VIIa for adjunctive hemorrhage control in trauma and surgical patients. American Surgeon 71, 776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Morse BC, Dente CJ, Hodgman EI, Shaz BH, Nicholas JM, Wyrzykowski AD, Salomone JP, Vercruysse GA, Rozycki GS, and Feliciano DV (2011) The effects of protocolized use of recombinant factor VIIa within a massive transfusion protocol in a civilian level I trauma center. Am Surg 77, 1043–1049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Boffard KD, Riou B, Warren B, Choong PI, Rizoli S, Rossaint R, Axelsen M, Kluger Y, and NovoSeven Trauma Study G (2005) Recombinant factor VIIa as adjunctive therapy for bleeding control in severely injured trauma patients: two parallel randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind clinical trials. J Trauma 59, 8–15; discussion 15‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Patanwala AE (2008) Factor VIIa (recombinant) for acute traumatic hemorrhage. Am J Health Syst Pharm 65, 1616–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Duchesne JC, Mathew KA, Marr AB, Pinsky MR, Barbeau JM, and McSwain NE (2008) Current evidence based guidelines for factor VIIa use in trauma: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am Surg 74, 1159–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Rappold JF, and Pusateri AE (2013) Tranexamic acid in remote damage control resuscitation. Transfusion 53 Suppl 1, 96–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Pusateri AE, Weiskopf RB, Bebarta V, Butler F, Cestero RF, Chaudry IH, Deal V, Dorlac WC, Gerhardt RT, Given MB, et al. (2013) Tranexamic Acid and Trauma: Current Status and Knowledge Gaps With Recommended Research Priorities. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 39, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cannon JW, Khan MA, Raja AS, Cohen MJ, Como JJ, Cotton BA, Dubose JJ, Fox EE, Inaba K, Rodriguez CJ, et al. (2017) Damage control resuscitation in patients with severe traumatic hemorrhage: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 82, 605–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Levi M, Levy JH, Andersen HF, and Truloff D (2010) Safety of recombinant activated factor VII in randomized clinical trials. N Engl J Med 363, 1791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, Caballero J, Coats T, Dewan Y, El‐Sayed H, Gogichaishvili T, Gupta S, Herrera J, et al. (2010) Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH‐2): a randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet 376, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Rourke C, Curry N, Khan S, Taylor R, Raza I, Davenport R, Stanworth S, and Brohi K (2012) Fibrinogen levels during trauma hemorrhage, response to replacement therapy, and association with patient outcomes. J Thromb Haemost 10, 1342–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Maegele M, Zinser M, Schlimp C, Schochl H, and Fries D (2015) Injectable hemostatic adjuncts in trauma: Fibrinogen and the FIinTIC study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 78, S76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hannon M, Quail J, Johnson M, Pugliese C, Chen K, Shorter H, Riffenburgh R, and Jackson R (2015) Fibrinogen and prothrombin complex concentrate in trauma coagulopathy. J Surg Res 196, 368–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Levy JH, Welsby I, and Goodnough LT (2014) Fibrinogen as a therapeutic target for bleeding: a review of critical levels and replacement therapy. Transfusion 54, 1389–405; quiz 1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kozek‐Langenecker S, Sorensen B, Hess JR, and Spahn DR (2011) Clinical effectiveness of fresh frozen plasma compared with fibrinogen concentrate: a systematic review. Crit Care 15, R239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).McBride D, Tang J, and Zhang JH (2015) Maintaining Plasma Fibrinogen Levels and Fibrinogen Replacement Therapies for Treatment of Intracranial Hemorrhage. Curr Drug Targets. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ozier Y, and Hunt BJ (2011) Against: Fibrinogen concentrate for management of bleeding: against indiscriminate use. J Thromb Haemost 9, 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Okerberg CK, Williams LA 3rd, Kilgore ML, Kim CH, Marques MB, Schwartz J, and Pham HP (2016) Cryoprecipitate AHF vs. fibrinogen concentrates for fibrinogen replacement in acquired bleeding patients ‐ an economic evaluation. Vox Sang 111, 292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Levi M, Friederich PW, Middleton S, Groot P. G. d., Wu YP, Harris R, Biemond BJ, Heijnen HFG, Levin J, Cate J. W. t., et al. (1999) Fibrinogen‐coated albumin microcapsules reduce bleeding in severely thrombocytopenic rabbits. Nature medicine 5, 107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ilium L, Davis SS, Wilson CG, Thomas NW, Frier M, and Hardy JG (1982) Blood clearance and organ deposition of intravenously administered colloidal particles. The effects of particle size, nature and shape. Int. J. Pharm 12, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Okamura Y, Takeoka S, Eto K, Maekawa I, Fujie T, Maruyama H, Ikeda Y, and Handa M (2009) Development of fibrinogen γ‐chain peptide‐coated, adenosine diphosphate‐encapsulated liposomes as a synthetic platelet substitute. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 7, 470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Okamura Y, Takeoka S, Teramura Y, Maruyama H, Tsuchida E, Handa M, and Ikeda Y (2005) Hemostatic effects of fibrinogen γ‐chain dodecapeptide‐conjugated polymerized albumin particles in vitro and in vivo. Transfusion 45, 1221–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ravikumar M, Modery CL, Wong TL, Dzuricky M, and Sen Gupta A (2012) Mimicking adhesive functionalities of blood platelets using ligand‐decorated liposomes. Bioconjug Chem 23, 1266–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Modery‐Pawlowski CL, Tian LL, Ravikumar M, Wong TL, and Sen Gupta A (2013) In vitro and in vivo hemostatic capabilities of a functionally integrated plateletmimetic liposomal nanoconstruct. Biomaterials 34, 3031–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kudela D, Smith SA, May‐Masnou A, Braun GB, Pallaoro A, Nguyen CK, Chuong TT, Nownes S, Allen R, Parker NR, et al. (2015) Clotting activity of polyphosphate‐functionalized silica nanoparticles. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 54, 4018–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Ploense KL, Kippin T, Hammond S, Stucky G, and Kudela D (2016) Polyphosphate-conjugated Silica Nanoparticles (polyP‐SNPs) Attenuate Bleeding After Tail Amputation. The FASEB Journal 30, lb483–lb483. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Brown AC, Stabenfeldt SE, Ahn B, Hannan RT, Dhada KS, Herman ES, Stefanelli V, Guzzetta N, Alexeev A, Lam WA, et al. (2014) Ultrasoft microgels displaying emergent platelet‐like behaviours. Nat Mater 13, 1108–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Chan LW, Wang X, Wei H, Pozzo LD, White NJ, and Pun SH (2015) A synthetic fibrin cross‐linking polymer for modulating clot properties and inducing hemostasis. Sci Transl Med 7, 277ra29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Baylis JR, Chan KY, and Kastrup CJ (2016) Halting hemorrhage with self‐propelling particles and local drug delivery. Thromb Res 141 Suppl 2, S36–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Baylis JR, St John AE, Wang X, Lim EB, Statz ML, Chien D, Simonson E, Stern SA, Liggins RT, White NJ, et al. (2016) Self‐Propelled Dressings Containing Thrombin and Tranexamic Acid Improve Short‐Term Survival in a Swine Model of Lethal Junctional Hemorrhage. Shock (Augusta, Ga.) 46, 123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Baylis JR, Yeon JH, Thomson MH, Kazerooni A, Wang X, St John AE, Lim EB, Chien D, Lee A, Zhang JQ, et al. (2015) Self‐propelled particles that transport cargo through flowing blood and halt hemorrhage. Science advances 1, e1500379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bertram JP, Williams CA, Robinson R, Segal SS, Flynn NT, and Lavik EB (2009) Intravenous hemostat: nanotechnology to halt bleeding. Sci Transl Med 1, 11ra22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Shoffstall AJ, Atkins KT, Groynom RE, Varley ME, Everhart LM, Lashof-Sullivan MM, Martyn‐Dow B, Butler RS, Ustin JS, and Lavik EB (2012) Intravenous hemostatic nanoparticles increase survival following blunt trauma injury. Biomacromolecules 13, 3850–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Shoffstall AJ, Everhart LM, Varley ME, Soehnlen ES, Shick AM, Ustin JS, and Lavik EB (2013) Tuning ligand density on intravenous hemostatic nanoparticles dramatically increases survival following blunt trauma. Biomacromolecules 14, 2790–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lashof‐Sullivan MM, Shoffstall E, Atkins KT, Keane N, Bir C, VandeVord P, and Lavik EB (2014) Intravenously administered nanoparticles increase survival following blast trauma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111, 10293–10298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Szebeni J, Bedocs P, Csukas D, Rosivall L, Bunger R, and Urbanics R (2012) A porcine model of complement‐mediated infusion reactions to drug carrier nanosystems and other medicines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64, 1706–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Szebeni J, Bedocs P, Rozsnyay Z, Weiszhar Z, Urbanics R, Rosivall L, Cohen R, Garbuzenko O, Bathori G, Toth M, et al. (2012) Liposome‐induced complement activation and related cardiopulmonary distress in pigs: factors promoting reactogenicity of Doxil and AmBisome. Nanomedicine 8, 176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Johnson RA, Simmons KT, Fast JP, Schroeder CA, Pearce RA, Albrecht RM, and Mecozzi S (2011) Histamine release associated with intravenous delivery of a fluorocarbon‐based sevoflurane emulsion in canines. J Pharm Sci 100, 2685–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Szebeni J, Muggia F, Gabizon A, and Barenholz Y (2011) Activation of complement by therapeutic liposomes and other lipid excipient‐based therapeutic products: prediction and prevention. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 63, 1020–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Szebeni J, Bedocs P, Urbanics R, Bunger R, Rosivall L, Toth M, and Barenholz Y (2012) Prevention of infusion reactions to PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin via tachyphylaxis induction by placebo vesicles: a porcine model. J Control Release 160, 382–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Szebeni J (2012) Hemocompatibility testing for nanomedicines and biologicals: predictive assays for complement mediated infusion reactions. European Journal of Nanomedicine 4, 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Goram AL, and Richmond PL (2001) Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: tolerability and toxicity. Pharmacotherapy 21, 751–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Wibroe PP, Anselmo AC, Nilsson PH, Sarode A, Gupta V, Urbanics R, Szebeni J, Hunter AC, Mitragotri S, Mollnes TE, et al. (2017) Bypassing adverse injection reactions to nanoparticles through shape modification and attachment to erythrocytes. Nature nanotechnology 12, 589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Hu CM, Fang RH, Wang KC, Luk BT, Thamphiwatana S, Dehaini D, Nguyen P, Angsantikul P, Wen CH, Kroll AV, et al. (2015) Nanoparticle biointerfacing by platelet membrane cloaking. Nature 526, 118–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hu CM, Zhang L, Aryal S, Cheung C, Fang RH, and Zhang L (2011) Erythrocyte membrane‐camouflaged polymeric nanoparticles as a biomimetic delivery platform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 10980–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Lunov O, Syrovets T, Loos C, Beil J, Delacher M, Tron K, Nienhaus GU, Musyanovych A, Mailander V, Landfester K, et al. (2011) Differential uptake of functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles by human macrophages and a monocytic cell line. ACS Nano 5, 1657–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Oh E, Delehanty JB, Sapsford KE, Susumu K, Goswami R, Blanco‐Canosa JB, Dawson PE, Granek J, Shoff M, Zhang Q, et al. (2011) Cellular uptake and fate of PEGylated gold nanoparticles is dependent on both cell‐penetration peptides and particle size. ACS Nano 5, 6434–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Yu K, Lai BF, Foley JH, Krisinger MJ, Conway EM, and Kizhakkedathu JN (2014) Modulation of complement activation and amplification on nanoparticle surfaces by glycopolymer conformation and chemistry. ACS Nano 8, 7687–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Thasneem YM, Sajeesh S, and Sharma CP (2013) Glucosylated polymeric nanoparticles: a sweetened approach against blood compatibility paradox. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 108, 337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Vauthier C, Persson B, Lindner P, and Cabane B (2011) Protein adsorption and complement activation for di‐block copolymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials 32, 1646–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Hamad I, Al‐Hanbali O, Hunter AC, Rutt KJ, Andresen TL, and Moghimi SM (2010) Distinct polymer architecture mediates switching of complement activation pathways at the nanosphere‐serum interface: implications for stealth nanoparticle engineering. ACS Nano 4, 6629–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Merkel OM, Urbanics R, Bedocs P, Rozsnyay Z, Rosivall L, Toth M, Kissel T, and Szebeni J (2011) In vitro and in vivo complement activation and related anaphylactic effects associated with polyethylenimine and polyethylenimine‐graft‐poly(ethylene glycol) block copolymers. Biomaterials 32, 4936–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Toklu HZ, Muller‐Delp J, Yang Z, Oktay S, Sakarya Y, Strang K, Ghosh P, Delp MD, Scarpace PJ, Wang KK, et al. (2015) The functional and structural changes in the basilar artery due to overpressure blast injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35, 1950–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Szebeni J (2014) Complement activation‐related pseudoallergy: a stress reaction in blood triggered by nanomedicines and biologicals. Molecular immunology 61, 163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Thibault G, Tardif P, and Lapalme G (2001) Comparative specificity of platelet alpha(IIb)beta(3) integrin antagonists. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 296, 690–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Dezsi L, Fulop T, Meszaros T, Szenasi G, Urbanics R, Vazsonyi C, Orfi E, Rosivall L, Nemes R, Kok RJ, et al. (2014) Features of complement activation‐related pseudoallergy to liposomes with different surface charge and PEGylation: comparison of the porcine and rat responses. J Control Release 195, 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Szebeni J, Wassef NM, Hartman KR, Rudolph AS, and Alving CR (1997) Complement activation in vitro by the red cell substitute, liposome‐encapsulated hemoglobin: mechanism of activation and inhibition by soluble complement receptor type 1. Transfusion 37, 150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Szebeni J (1998) The interaction of liposomes with the complement system. Critical Reviews™ in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems 15, 57–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Jackman JA, Meszaros T, Fulop T, Urbanics R, Szebeni J, and Cho NJ (2016) Comparison of complement activation‐related pseudoallergy in miniature and domestic pigs: foundation of a validatable immune toxicity model. Nanomedicine 12, 933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Unterweger H, Janko C, Schwarz M, Dezsi L, Urbanics R, Matuszak J, Orfi E, Fulop T, Bauerle T, Szebeni J, et al. (2017) Non‐immunogenic dextran‐coated superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: a biocompatible, size‐tunable contrast agent for magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Nanomedicine 12, 5223–5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Urbanics R, Bedőcs P, and Szebeni J (2015) in European Journal of Nanomedicine pp 219. [Google Scholar]

- (73).Szebeni J, Bedőcs P, Csukás D, Rosivall L, Bünger R, Urbanics R, Bedocs P, Csukas D, and Bunger R (2012) A porcine model of complement‐mediated infusion reactions to drug carrier nanosystems and other medicines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64, 1706–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Karp NA (2018) Reproducible preclinical research‐Is embracing variability the answer? PLoS Biol 16, e2005413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Richter SH (2017) Systematic heterogenization for better reproducibility in animal experimentation. Lab animal 46, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Banda NK, Mehta G, Chao Y, Wang G, Inturi S, Fossati‐Jimack L, Botto M, Wu L, Moghimi S, and Simberg D (2014) Mechanisms of complement activation by dextran‐coated superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoworms in mouse versus human serum. Particle and fibre toxicology 11, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Chen F, Wang G, Griffin JI, Brenneman B, Banda NK, Holers VM, Backos DS, Wu L, Moghimi SM, and Simberg D (2016) Complement proteins bind to nanoparticle protein corona and undergo dynamic exchange in vivo. Nature nanotechnology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Lashof‐Sullivan MM, Shoffstall E, Atkins KT, Keane N, Bir C, VandeVord P, and Lavik EB (2014) Intravenously administered nanoparticles increase survival following blast trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 10293–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Lashof‐Sullivan M, Holland M, Groynom R, Campbell D, Shoffstall A, and Lavik E (2016) Hemostatic Nanoparticles Improve Survival Following Blunt Trauma Even after 1 Week Incubation at 50 degrees C. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2, 385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Pham CT, Mitchell LM, Huang JL, Lubniewski CM, Schall OF, Killgore JK, Pan D, Wickline SA, Lanza GM, and Hourcade DE (2011) Variable antibody-dependent activation of complement by functionalized phospholipid nanoparticle surfaces. J Biol Chem 286, 123–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Socha M, Bartecki P, Passirani C, Sapin A, Damge C, Lecompte T, Barre J, El Ghazouani F, and Maincent P (2009) Stealth nanoparticles coated with heparin as peptide or protein carriers. J Drug Target 17, 575–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Mastellos DC, Yancopoulou D, Kokkinos P, Huber‐Lang M, Hajishengallis G, Biglarnia AR, Lupu F, Nilsson B, Risitano AM, Ricklin D, et al. (2015) Compstatin: a C3‐targeted complement inhibitor reaching its prime for bedside intervention. European journal of clinical investigation 45, 423–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Mastellos DC, Ricklin D, Hajishengallis E, Hajishengallis G, and Lambris JD (2016) Complement therapeutics in inflammatory diseases: promising drug candidates for C3-targeted intervention. Molecular oral microbiology 31, 3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Pischke SE, Gustavsen A, Orrem HL, Egge KH, Courivaud F, Fontenelle H, Despont A, Bongoni AK, Rieben R, Tonnessen TI, et al. (2017) Complement factor 5 blockade reduces porcine myocardial infarction size and improves immediate cardiac function. Basic Res Cardiol 112, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Paredes RM, Reyna S, Vernon P, Tadaki DK, Dallelucca JJ, and Sheppard F (2018) Generation of complement molecular complex C5b‐9 (C5b‐9) in response to poly-traumatic hemorrhagic shock and evaluation of C5 cleavage inhibitors in non‐human primates. International immunopharmacology 54, 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Kroshus TJ, Rollins SA, Dalmasso AP, Elliott EA, Matis LA, Squinto SP, and Bolman RM 3rd. (1995) Complement inhibition with an anti‐C5 monoclonal antibody prevents acute cardiac tissue injury in an ex vivo model of pig‐to‐human xenotransplantation. Transplantation 60, 1194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Fu Q, McPhie P, and Gowda DC (1998) Methionine modification impairs the C5-cleavage function of cobra venom factor‐dependent C3/C5 convertase. Biochemistry and molecular biology international 45, 133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Hoth JJ, Wells JD, Jones SE, Yoza BK, and McCall CE (2014) Complement mediates a primed inflammatory response after traumatic lung injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 76, 601–8; discussion 608‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Huber‐Lang M, Ignatius A, and Brenner RE (2015) Role of Complement on Broken Surfaces After Trauma. Adv Exp Med Biol 865, 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Younger JG, Bracho DO, Chung‐Esaki HM, Lee M, Rana GK, Sen A, and Jones AE (2010) Complement activation in emergency department patients with severe sepsis. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine 17, 353–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Lupu F, Keshari RS, Lambris JD, and Coggeshall KM (2014) Crosstalk between the coagulation and complement systems in sepsis. Thromb Res 133 Suppl 1, S28–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Helling H, Stephan B, and Pindur G (2015) Coagulation and complement system in critically ill patients. Clinical hemorheology and microcirculation 61, 185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Bertram JP, Jay SM, Hynes SR, Robinson R, Criscione JM, and Lavik EB (2009) Functionalized poly(lactic‐co‐glycolic acid) enhances drug delivery and provides chemical moieties for surface engineering while preserving biocompatibility. Acta biomaterialia 5, 2860–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Hermanson G (2008) Bioconjugate Techniques, Vol. 1, 2nd ed., Academic Press, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- (95).Connor EF, Nyce GW, Myers M, Möck A, and Hedrick JL (2002) First Example of N‐Heterocyclic Carbenes as Catalysts for Living Polymerization: Organocatalytic Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cyclic Esters. Journal of the American Chemical Society 124, 914–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Gurney J, Philbin N, Rice J, Arnaud F, Dong F, Wulster‐Radcliffe M, Pearce LB, Kaplan L, McCarron R, and Freilich D (2004) A Hemoglobin Based Oxygen Carrier, Bovine Polymerized Hemoglobin (HBOC‐201) versus Hetastarch (HEX) in an Uncontrolled Liver Injury Hemorrhagic Shock Swine Model with Delayed Evacuation. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 57, 726–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.