Abstract

Introduction

Health-promoting lifestyle behaviours are part of the activities of daily living that influence individual happiness, values and well-being. They play a crucial role in prevention and control of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among all age groups. Current statistics on mortality, disability and morbidity associated with NCDs are alarming globally. The use of information and communication technology (ICT) for a health-promoting lifestyle behaviour programme enhances health behaviours that are important in the prevention and control of both communicable and non-communicable diseases. Our study aimed to map evidence on the use of ICT in comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviour among healthy adults.

Methods

Eleven electronic databases were searched for the study. We included studies published in English between January 2007 and December 2018 reporting on healthy adults, ICT and any subscales of the health-promoting lifestyle profile (HPLP). Studies focusing on diseases or disease management and studies that combine monitoring tools in the form of hardware (accelerometer or pedometer) with ICT or computer games were excluded. Data were summarised numerically and thematically.

Results

All the studies reviewed were conducted in developed countries. Most of the studies reported on physical activity, and findings of one study covered all the subscales of HPLP. The use of ICT for health-promoting lifestyle behaviours was reported to be effective in ensuring health behaviours that can improve physical and mental health.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that there is a dearth of knowledge on comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviour that can be beneficial for the control and prevention of NCDs. There is a need to carry out primary studies on the use of ICT and comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle, especially among adults in low-income and middle-income countries where there are alarming statistics for mortality and disability associated with NCDs.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016042568.

Keywords: health-promoting lifestyle behaviour, nutrition, physical activity, health responsibility, stress management, interpersonal relationship, self-actualisation, information and communication technology, healthy adults, systematic scoping review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A comprehensive and extensive literature search on the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviour among healthy adults was done to identify research gap.

Rigorous process was followed in searching and selecting the included articles for the study.

Inclusion of primary research articles in the study was subjected only to Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) V.2011.

Only studies published in English between January 2007 and December 2018 were included in the study.

The reference lists of the included articles were not examined, and no manual searches were performed. Lastly, only electronic databases were extensively searched for the included studies.

Introduction

Increase in the prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as chronic cardiovascular diseases, stroke, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes mellitus calls for more proactive ways to manage, control and prevent them. Seventy per cent of global mortality has been attributed to NCDs.1 2 Eighty per cent of deaths associated with NCDs occur in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the 30–60 years age group.2–5 In 2013, a report showed that (Int$) 53.8 billion was spent on NCDs globally.6 NCDs have been shown to be a major barrier to development and achievement of the millennium development goals.6 Many NCDs have a strong association with unhealthy lifestyle.2 7 8 Risk factors for NCDs are tobacco use, food high in saturated and trans fat, high consumption of sugar and salt, excessive alcohol intake, physical inactivity, poor diet, overweight and obesity, inadequate sleep and rest, stress and exposure to environmental hazards.9–12

Health-promoting lifestyle behaviour has been identified as having an essential role in prevention and control of NCDs.13–16 Health promotion is an umbrella term describing a composite of disease prevention and health promotion.3 Information and communication technology (ICT) has been shown to be beneficial as it has made it possible to access health-related information easily.17 The use of ICT in health promotion and health management is increasingly well recognised because of its cost-effectiveness in the prevention of diseases.18 Evidence exists that ICT is used in health surveillance for both communicable and non-communicable diseases. ICT paired with monitoring tools can improve physical activity (PA) and weight loss.19 Few individuals adhere to healthy lifestyle behaviour despite the role it plays in chronic disease prevention, and literature has shown that web-based interventions are effective in changing behaviour.20 ICT refers to technology that provides access to information and communication21 through a wide range of communication tools. In this study, ICT includes internet, cell phones, computers and websites.

The use of ICT in management and prevention of diseases is on the increase. ICT applications are used in psychotherapeutic intervention,22 23 management and control of medical conditions such as hypertension,24 25 HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases,26 diabetes management, smoking cessation, asthma management, weight loss and PA.20 27 28 ICT applications have also been used for recruitment of particular research groups. One good example was a study conducted by Bauermeister and his team, where they used a web version of respondent-driven sampling (webRDS) to recruit a sample of young adults (ages 18–24) and examined whether this strategy would result in alcohol and other drug prevalence estimates comparable with national estimates.29 On health-promoting lifestyle and ICT, several studies have been done, mainly on PA, smoking cessation, alcohol intervention and diet for weight control. However, there are other health-promoting lifestyle behaviours such as stress management, interpersonal relationship, health responsibility and self-actualisation that are equally important to disease prevention and health promotion, along with PA and nutrition.11

We are not aware of any review that has reported on the use of ICT and the six domains of comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviour (nutrition, PA, stress management, interpersonal relationships, self-actualisation/spiritual growth and health responsibility) among healthy individuals. Comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviours are described for the purpose of this study as day-to-day lifestyle practices that can prevent diseases and promote health. The six health-promoting lifestyle behaviours are the subscales of the health-promoting lifestyle profile (HPLP) instrument.30 Joseph-Shehu et al 31 described the HPLP subscales as follows: (1) nutrition signifies an individual’s eating habits and food choices; (2) PA signifies actions engaged in by an individual that make him/her active and not sedentary; (3) health responsibility signifies knowing how to act in ways that improve one’s own health; (4) stress management signifies the ability to identify factors that affect one’s stress level and being able to manage such factors; (5) self-actualisation is the ability to achieve one’s life goals by adopting a positive approach and drawing on one’s talents and creativity; (6) spiritual growth is not specific to any particular religion; rather, it signifies ability to harness inner resources to connect with oneself and with others and having purpose in life that leads one to excel and develop in attaining life goals and possible fulfilment; (7) interpersonal relations signifies achieving meaningful and sustainable relationships with people through any form of communication.31

Each of these health-promoting lifestyle behaviours is important in the prevention and control of both communicable and non-communicable diseases, as they are part of the activities of daily living that influence individual happiness, values and well-being.32 Reports show that there was a lower risk of developing diabetes mellitus, stroke, myocardial infarction and cancers among 23 153 Germans between 35 and 65 years of age that were followed for an average period of 7.8 years on adherence to no smoking, exercise, healthy diet and body mass index (BMI) less than 30 kg/m2 compared with participants that did not engage in these healthy lifestyle practices.20 There is a possibility that if lifestyle practices such as stress management, interpersonal relationships, health responsibility and self-actualisation were added to the lifestyle, this could have led to lower risk for developing other NCDs such as peptic ulcer and mental illnesses. Hence, this study aimed to map evidence on the use of ICT in health-promoting lifestyle behaviour among healthy individuals to comprehensively assess the current state of knowledge on health-promoting lifestyle behaviour and ICT. The results of this study will help identify an area that requires meta-analysis and future primary research. This systematic scoping review accordingly seeks to address the following research questions:

Does use of ICT improve and enhance health-promoting lifestyle behaviour?

Is there any evidence that use of ICT in health-promoting lifestyle activity resulted in good health status (healthy weight, normal blood pressure, normal blood sugar, and good mental and physical health)?

Methods/Designs

This systematic scoping study was registered with PROSPERO (the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews): registration number CRD42016042568. The review adopted the five stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s framework (identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarising and reporting the results) for conducting scoping reviews.33 The study protocol was published in BMJ Open.3 This review report was guided by PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews).34

Search strategy

An extensive search of eligible studies was conducted on the following 11 databases: Academic Search Complete (EBSCO), PsycArticle (EBSCO), PubMed, Medline (EBSCO), CINAHL (EBSCO), Educational Source (EBSCO), Health Source: Consumer Edition (EBSCO), Health Source: Nursing Academic Edition (EBSCO), PsycINFO (EBSCO), Science Direct and Google Scholar. We searched for articles published in the English language between January 2007 and December 2018. This time frame was selected to assess work that has been done on using ICT in comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviour among healthy adults over one decade. The search strategy was focused mainly on the study interventions and the population of interest (table 1). Boolean operators (AND and OR) separated keywords in the search as follows: health promoting lifestyle profile OR health-promoting lifestyle profile OR health-promoting lifestyle behaviour OR wellness OR nutrition OR diet OR physical activity OR interpersonal relationships OR health responsibility OR stress management OR self-actualisation OR spiritual growth AND information and communication technology OR ICT OR mobile phone OR text messages OR SMS OR e-health OR m-health OR the internet AND adult OR workers OR employees. Summary of the search strategy is found in the (online supplementary file 1).

Table 1.

Population, Interventions, Comparison, Outcome and Study setting (PICOS) framework for determination of the eligibility of the review questions

| Criteria | Determinants |

| Population | Healthy adults, workers and well individuals |

| Interventions | Health-promoting lifestyle profile (nutrition, interpersonal relationship, health responsibility, stress management, self-actualisation or spiritual growth) and information and communication technologies (ICT, mobile phone, text messages, SMS, internet, computers, websites) |

| Comparison | Health-promoting lifestyle profile intervention without ICT |

| Outcomes | Effective and sustaining health-promoting lifestyle practices (nutrition, interpersonal relationship, health responsibility, stress management, self-actualisation or spiritual growth) and health status (normal weight, normal blood pressure, normal blood sugar and good mental and physical health) |

| Study setting | Focus on low-income and middle-income countries |

Adopted from the study protocol.3

ICT, information and communication technology; PA, physical activity; SMS, short messaging service.

bmjopen-2019-029872supp001.pdf (23.4KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Studies reporting on healthy workers, professionals and adults.

Studies published in the English language.

Studies published between January 2007 and December 2018.

Studies reporting on interventions such as one or more subscale(s) of the health-promoting lifestyle profile (stress management, interpersonal relationships, nutrition, self-actualisation/spiritual growth, health responsibility and PA) and ICT (text messages, short messaging service (SMS), computers, mobile phone, websites and internet).

All study designs, including cross-sectional studies, quantitative studies, randomised controlled trial (RCT) studies, quasi-experimental study designs, cohort studies, qualitative studies and systematic reviews.

Exclusion criteria

Studies which do not report on any form of ICT.

Studies on patients, youth, students, diseases/management or children.

Studies that do not report on all or any of the subscales of the HPLP.

Studies that do not report on outcome of interest (table 1).

Studies that use any form of ICT in recruitment or as a means of collecting data only.

Literature published before January 2007 and after December 2018.

Studies which do not report on adults.

Studies that combine monitoring tools in the form of hardware (accelerometer or pedometer) with ICT and computer games.

Studies reporting on alcoholism, obesity or cigarette smoking.

Non-English publications.

Study protocols, non-systematic review, book chapters, dissertation and letter to the editors.

Study selection

The selection process for the included articles involved rigorous exercises in three stages of screening—title, abstract and full-text screening—before data extraction. One reviewer conducted the title screening of the included articles and abstract, and full-text screening was undertaken independently by two reviewers. Any disagreement at any level of the screening was discussed until both reviewers reached consensus. Title of an article that was not cleared was included for abstract screening, and if abstract of an article was not cleared, same was added for the full-text screening. The reviewers developed the screening form before commencement of the screening exercise. The screening forms were developed based on population, interventions and outcomes.3 Systematic reviews were included if they met the inclusion criteria. Two independent reviewers screened the included articles full text, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above, and consensus between the reviewers resolved any disagreement. The degree of agreement between reviewers at the full-text screening stage was estimated using kappa statistic with STATA V.13.

Data extraction

Data extraction criteria were determined, and a self-designed data extraction form was designed by the reviewers before data extraction to aid the process. The primary outcome measured was health-promoting lifestyle behaviours and health status (table 1). There was no restriction on how to measure the outcome such as whether physiological or self-report. However, use of accelerometer, pedometer or computer games was not included in this study. In order to provide answers to the study questions, data extracted from each of the studies included were as follows: bibliography of the study (author’s name and date), location of the study, objective or aim of the study (as reported by authors), study design, study population, study setting, sample size, type of ICT (table 1), type of health-promoting lifestyle behaviour (table 1), duration of the study, outcome of the study, results or findings from the study and conclusions of the study.

Quality appraisal of the included studies

Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) V.201135 was used to assess the quality of included research articles. MMAT was designed to evaluate articles on primary research using the following study designs: qualitative; quantitative and mixed method. The MMAT enabled us to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Scores for each study varied between 25% and 100%. For mixed method studies, there were 11 criteria to be met for an article to be rated as high; four criteria each for quantitative (QUANT) section and qualitative (QUAL) section and three for mixed method (MM) section. MM studies were rated as 25% when QUAL=1 and QUAN=1 and MM=0; as 50% when QUAL=2 and QUAN=2 and MM=1; as 75% when QUAL=3 and QUAN=3 and MM=2; and as 100% when QUAL=4 and QUAN=4 and MM=3. A criterion score between 25% and 49% was rated as low quality, a score of 50%–74% as average quality and a score of 75%–100% as high quality.

Collating and summarising the findings

Extracted data were summarised numerically and thematically using the following two themes: ICT used in health-promoting lifestyle behaviour and health-promoting lifestyle behaviour outcomes. The authors collectively assessed themes and conducted a critical appraisal of each theme in relation to the research questions. We also examined the meaning of the findings in relation to the aim of the study and their implications for research, practice and policy.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the study as it is a systematic scoping review.

Results

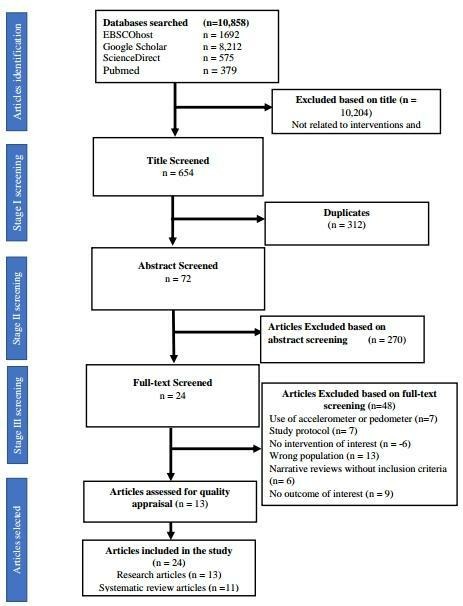

The literature encompassed a broad scope of studies exploring the use of ICT in health-promoting lifestyle behaviour among healthy individuals. Eleven electronic databases searched (figure 1) yielded 10 858 potential articles. After screening and duplicates were removed, 24 articles met the study inclusion criteria. The kappa statistics for the degree of agreement showed 74.5% agreement versus 49.8% expected by chance, which constitutes moderate to substantial agreement (kappa statistic=0.49, p-value<0.001). McNemar’s χ2 statistic suggests that there is not a statistically significant difference in the proportions of yes/no answers by reviewers. The study includes 13 research articles and 11 systematic reviews identified as meeting the inclusion criteria and focused on the specified health-promoting lifestyle behaviours and ICT among healthy adults.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the included article.

Characteristics of included studies in this scoping review

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in table 2. Two of the included studies adopted MM designs36 37; one study in each case adopted qualitative design,38 quantitative non-randomised design,39 prospective longitudinal cluster-randomised controlled trial,40 retrospective randomised trial design41 and intervention study.42 Six studies18 20 43–46 adopted RCT design. The duration of the intervention studies ranged from 4 weeks to 10 months. One of the main study aims was to determine the effect of proactive dissemination strategy on the reach of the internet-delivered computer-tailored intervention42; study duration commenced with the invitation to participate in the study. Sample sizes of the included research articles ranged from 26 to 16 948; sample sizes of the included evidence review articles ranged from 11 to 457.47 Twelve studies focused on males and females,20 36–42 44–46 48 one reported on females alone,18 one reported on all study population,49 one reported on employees50 and nine studies (systematic review) did not report study population.17 27 47 51–56 Seven of the studies reviewed were conducted in the community.39 41 44–46 48 56 Eight were conducted at the workplace: one each among the military,40 nurses,18 university employees,36 municipality employees46; two in more than one organisation20 38 47; and two did not describe the workers.37 50

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author and date | Country | Income level of country | Aim of the study | Study design | Study population | Study setting | Sample size | Duration of study |

| Research articles | ||||||||

| Ammann et al (2012)39 | Australia | High | To evaluate a website-delivered computer-tailored PA intervention, with a specific focus on differences in tailored advice acceptability, website usability, and PA change between three age groups. | Quantitative non-randomised design | Male and female | Community | 863 | 1 month |

| Bardus et al (2014)38 | UK | High | To investigate the reason for participating and not participating in an eHealth workplace PA intervention. | Qualitative study | Male and female | Workplace | 62 | Not specified |

| Carr et al (2013)48 | USA | High | The goals of these focus groups were to identify internet features rated as ‘useful for improving PA’. | RCT design | Male and female | Community | 53 | 6 months |

| Frank et al (2016)40 | USA | To determine if a telehealth coaching initiative is superior to a one-time nutrition and fitness education class regarding: (1) dietary contributions to bone health and (2) exercise contributions to bone health, assessed before and after deployment. | Prospective, longitudinal, cluster-RCT | Male and female | Workplace | 158 | 9 months | |

| Guertler et al (2015)41 | Australia | High | The aims of this study were to (1) examine the engagement with the freely available PA promotion programme 10 000 Steps, (2) examine how use of a smartphone app may be helpful in increasing engagement with the intervention and in decreasing non-usage attrition, and (3) identify sociodemographic and engagement-related determinants of non-usage attrition. | Retrospective randomised trial | Male and female | Community | 16 948 | 9 months |

| King et al (2016)44 | USA | High | This study provided an initial 8-week evaluation of three different customised PA-sedentary behaviour apps drawn from conceptually distinct motivational frames in comparison with a commercially available control app. | Controlled experimental design | Male and female | Community | 95 | 8 weeks |

| Kirwan et al (2012)45 | Australia | High | To measure the potential of a newly developed smartphone application to improve health behaviours in existing members of a website-delivered PA programme (10 000 Steps, Australia). | Two-arm matched case–control trial | Male and female | Community | 200 | 3 months |

| Lara et al (2016)37 | UK | High | We report a pilot RCT of a web-based platform (Living, Eating, Activity and Planning through retirement; LEAP) promoting healthy eating (based on an MD, PA and meaningful social roles. | Mixed method design | Male and female | Workplace | 70 | 8 weeks |

| Mackenzie et al (2015)36 | UK | High | To explore the acceptability and feasibility of a low-cost, co-produced, multimodal intervention to reduce workplace sitting. | Mixed method design | Male and female | Workplace | 26 | Over 4 weeks |

| Naimark et al (2015)20 | Israel | High | Our aim was to compare people receiving a new web-based app with people who got an introductory lecture alone on healthy lifestyle, weight change, nutritional knowledge and PA, and to identify predictors of success for maintaining a health. | RCT | Male and female | Workplace | 85 | 14 weeks |

| Schneider et al (2013)42 | The Netherlands | High | This study investigated the influence of content and timing of a single email prompt on re-use of an internet-delivered CT lifestyle programme. | RCT | Male and female | Workplace | 200 | 6 weeks |

| Schneider et al (2013)42 | The Netherlands | High | This study aimed to determine the effect of proactive dissemination strategy on reach of the internet-delivered CT intervention. | Intervention study | Male and female | Community | 5168 | 10 months |

| Tsai et al (2015)18 | Taiwan | High | This study aimed to evaluate health-promoting effects of an eHealth intervention among nurses compared with conventional handbook learning. | Randomised control | Female nurses | Workplace | 105 | 12 weeks |

| Review evidence articles | ||||||||

| Bardus et al (2015)49 | 36 countries in Asian, Australia and Oceania; Europe, North and South America |

High | To provide an up-to-date, comprehensive map of the literature discussing use of mobile phone and web 2.0 apps for influencing behaviours related to weight management (ie, diet, PA, weight control). | Review | All population group | Not specified | 457 articles | NA |

| Bert et al (2014)51 | Not specified | High | To describe use of smartphones by health professionals and patients in the field of health promotion. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 21 articles | NA |

| Buhi et al (2013)52 | Europe, Asia South Korea, USA, New Zealand | High | To perform a systematic review of the literature concerning behavioural mobile health (mHealth) and summarise points related to heath topic, use of theory, audience, purpose, design, intervention components and principal results that can inform future health education applications. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 34 articles | NA |

| Fanning et al (2012)27 | Not specified | Not specified | The aims of this review were to (1) examine the efficacy of mobile devices in the PA setting, (2) explore and discuss implementation of device features across studies and (3) make recommendations for future intervention development. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 11articles | NA |

| Howarth et al (2018)47 | Not specified | Not specified | The aim of this systematic review was to assess the impact of pure digital health interventions in the workplace on health-related outcomes. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 22 articles | NA |

| Hou et al (2014)53 | USA | High | This review examines internet interventions aiming to change health behaviours in the general population. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 38 articles | NA |

| Kohl et al (2013)54 | Not specified | Not specified | The aim of this paper is to (1) review the current literature on online prevention aimed at lifestyle behaviours, and (2) identify research gaps regarding reach, effectiveness and use. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 41 articles | NA |

| Laranjo et al. (2014)17 | UK, USA, Australia | High | Our aim was to evaluate use and effectiveness of interventions using SNSs to change health behaviours. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 12 articles | NA |

| Lee et al (2018)56 | The objective of this study was to investigate the content and usefulness of mobile app programme for the general adult population. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 12 articles | NA | ||

| Rogers et al (2017)55 | Not specified | Not specified | The aims of this study were to (1) discover the range of health-related topics that were addressed through internet-delivered interventions, (2) generate a list of current websites used in the trials which demonstrated a health benefit and (3) identify gaps in the research that may have hindered dissemination. | Review | Not specified | Not specified | 71 articles | NA |

| Stratton et al (2017)50 | Not specified | Not specified | The aim of this paper is to conduct the first comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the evidence for the effectiveness and examine the relative efficacy of different types of eHealth interventions for employees. | Review | Employee | Workplace | 23 articles | NA |

CT, computer-tailored; MD, Mediterranean diet; NA, not applicable; PA, physical activity; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SNSs, social networking sites.

Five of the 11 systematically reviewed studies27 50 51 54 55 did not report the study country of included articles; one reported 457 articles from 36 countries in Asia, Australia and Oceania, Europe, North America and South America49; one reviewed 34 articles from five countries (Europe, Asia, South Korea, USA, New Zealand)52; 12 articles from three countries (USA, UK and Australia)17; 12 articles from nine countries (USA, Denmark, England, Ireland, Canada, Australia, South Korea, Israel and Singapore),56 22 articles from eight countries (USA, Australia, Netherlands, UK, Sweden, Japan, Norway and Singapore)47 and 38 articles from the USA alone.53 In regard to primary research included in this study, three studies were conducted in Australia,39 41 45 three in the UK,36–38 three in the USA,40 43 44 two in the Netherlands,42 46 one in Israel20 and one in Taiwan.18 Not all of the included studies reported on geographical setting of the research and none of the studies was conducted in an LMIC.

Risk-of-bias assessment

In regard to quality assessment of the included studies, the scores of the 13 articles reviewed for methodological quality ranged from 50% to 100%. Nine of the reviewed articles were rated as high quality, of which three scored 100%40 44 45 and six scored 75%.18 20 38 41 42 48 Only four were rated average quality, with two scoring 50%39 46 and two scoring 67%.36 37 The overall quality assessment was appraised to be average risk of bias due to the following: no clear description of concealment, withdrawal rate higher than 20% and no consideration given to how findings related to researcher influence.

ICT use in health-promoting lifestyle behaviours

A theme emerging from the study was ICT use in health-promoting lifestyle behaviours, and health-promoting lifestyle behaviours targeted by the included studies (table 3). Various forms of ICT (email, social network sites (SNSs), websites, SMS or text messages, mobile phone app, smartphones, computers, and multimedia messaging service (MMS)) were used in the included studies for health-promoting lifestyle behaviours intervention that targeted one form or another of health-promoting behaviours. In all the included articles the internet was obviously used via either phones or computers. However, some authors specifically mentioned use of internet in their reports,42 46–48 52 55 and a few authors explicitly mentioned computer use.42 46 53 All the reviewed studies except one50 reported on physical activity, 13 reported on nutrition,18 20 37 40 42 46 47 49 51 53–56 one reported on social connection,37 three reported on stress management47 50 56 and one reported on all the subscales of health-promoting lifestyle profile.18

Table 3.

Health-promoting lifestyle behaviours and ICT

| Author and date | ICT employed | Health promoting-lifestyle behaviour | Outcome of interest | Findings | Conclusion |

| Ammann et al (2012)39 | Email, website | PA | PA and BMI | No significant differences between the age groups were found with regard to BMI and PA level at baseline. All age groups increased their weekly total PA minutes and the number of total PA sessions significantly over time from baseline to 1-month follow-up. Old-age group increased PA more than the other two age groups. | The study suggests that website-delivered PA interventions can be suitable and effective for older aged adults. |

| Bardus et al (2014)38 | Website, email and text messaging (SMS) | PA | PA | Reasons for participation included a need to be more active, increase motivation to engage in PA, and better weight management. Employees were attracted by the perceived ease of use of the programme and by the promise of receiving reminders. Many felt encouraged to enrol by managers or peers. Reported reasons for non-participation are lack of time, loss of interest towards the programme, or a lack of reminders to complete enrolment. | In developing workplace PA interventions, it is important to identify salient motivators and barriers to participation through formative research with the target population. Programme enrolment procedures should be simple and not time consuming, so that burden on participants is reduced and early attrition is minimised. It is also important that employers find ways to actively promote WHPPs to their staff while also maintaining confidentiality and individual rights on employees, so that larger segments of the workforce can be reached. |

| Bardus et al (2015)49 | Mobile phone and web V.2.0 technologies | PA, diet and weight loss management | Diet and PA | This review categorised the identified articles into two overarching themes, which described use of technologies for either (1) promoting behaviour change (309/457, 67.6%) or (2) measuring behaviour (103/457, 22.5%). The remaining articles were overviews of apps and social media content (33/457, 7.2%) or covered a combination of these three themes (12/457, 2.6%). | Limited evidence exists on use of social media for behaviour change, but a segment of studies deals with content analyses of social media. Future research should analyse mobile phone and web V.2.0 technologies together by combining the evaluation of content and design aspects with usability, feasibility and efficacy/effectiveness for behaviour change, in order to understand which technological components and features are likely to result in effective interventions. |

| Bert et al (2014)51 | Smart phones | Nutrition lifestyles, PA, health in elderly, prevention of sexually transmitted diseases | Nutrition and PA | Out of 21 articles identified as specifically centred on health promotion, the nutrition field has applications that allow to count calories and keep a food diary or more specific platforms for people with food allergies. While in the PA many applications suggest exercises with measurement of sports statistics and some applications deal with lifestyles suggestions and tips. | The promotion of healthy lifestyles, adequate nutrition and PA are all possible and desirable through use of smartphones but it is important to underline the crucial role of healthcare providers in the management of the patient while using these tools. There is also a need to analyse the usefulness, quality and accuracy of smartphones applications in the field of preventive medicine. |

| Buhi et al (2013)52 | SMS, MMS, internet | Breast cancer prevention, diabetes management, weight loss or obesity prevention, smoking cessation, asthma self-management and PA | PA and breast cancer prevention | One journal assessed PA promotion and breast cancer prevention, respectively. Twenty interventions (59%) were evaluated using experimental designs, and most resulted in statistically significant health behavioural changes. | Consideration should be given for the deployment of mHealth applications to combat coronary heart disease, HIV/AIDS and other high-priority problems contributing to high mortality. A mobile video-based modality, using sight and sound, may show even greater promise in health behaviour change interventions. |

| Carr et al. (2013)48 | Internet website | PA | PA | The EI arm increased PA in relation to the SI arm at 3 months but between-group differences were not observed at 6 months. EI participants maintained PA from 3–6 months. This result suggests that a non-face-to-face, user-guided and theory-guided internet PA programme is more efficacious for producing immediate increases in PA among sedentary adults than what is currently available to the public. | The EI programme was efficacious at improving PA levels in relation to publicly available websites initially, but differences in PA levels were not maintained at 6 months. Future research should identify internet features that promote long-term maintenance. |

| Fanning et al (2012)27 | Mobile device, mobile software, SMS | PA | PA | Four studies were of ‘good’ quality and seven of ‘fair’ quality. In total, 1351 individuals participated in 11 unique studies. This study suggests that mobile devices are effective means for influencing PA behaviour. | Our focus must be on the best possible use of these tools to measure and understand behaviour. Therefore, theoretically grounded behaviour changes interventions that recognise and act on the potential of smartphone technology could provide investigators with an effective tool for increasing PA. |

| Frank et al (2016)40 | Website, email | Exercise, nutrition, bone health | PA, nutrition, waist circumference, BMI | There were no significant differences found in the BMI and waist circumference of soldiers in both control and intervention group over the course of study. There were significant increases in body fat, osteocalcin and sports index for the telehealth group. | A 9-month deployment to Afghanistan increased body fat, bone turnover and PA among soldiers randomised to receive telehealth strategies to build bone with nutrition and exercise. This study indicates that diet and exercise coaching via telehealth methods to deployed soldiers is feasible but limited in its effectiveness for short-term overseas deployments. |

| Guertler et al (2015)41 | Smartphone app and website | PA | PA | Compared with other freely accessible web-based health behaviour interventions, the 10 000 Steps programme showed high engagement. | Use of an app alone or in addition to the website can enhance programme engagement and reduce risk of attrition. |

| Hou et al (2014)53 | Computer-based information and communication technology | Tobacco prevention, alcohol prevention, weight loss, PA, nutrition, HIV and chronic diseases | PA and nutrition | There were seven studies focused primarily on increasing PA, and additionally five studies also examined related factors, such as nutrition and binge eating. Two studies were categorised as nutrition only interventions, with one focused on folic acid intake and the other targeted FJV consumptions. | Findings from the current review study indicated that, overall, internet or WIs produce favourable results and are effective in producing and increasing targeted health or behavioural outcomes. |

| Howarth et al (2018)47 | Smartphone, email, either as a website, app or downloadable software. | Self-reported measures of sleep, PA levels and healthy lifestyle rating, mental health | Blood pressure and BMI, PA, mental health |

There was a high level of heterogeneity across these studies, significant improvements were found for a broad range of outcomes such as sleep, mental health, sedentary behaviours and PA levels. Standardised measures were not always used to quantify intervention impact. All but one study resulted in at least one significantly improved health-related outcome, but attrition rates ranged widely, suggesting sustaining engagement was an issue. | This review found modest evidence that digital-only interventions have a positive impact on health-related outcomes in the workplace. High heterogeneity impacted the ability to confirm what interventions might work best for which health outcomes, although less complex health outcomes appeared to be more likely to be impacted. A focus on engagement along with the use of standardised measures and reporting of active intervention components would be helpful in future evaluations. |

| King et al (2016)44 | Smartphone’s built-in accelerometer | PA | PA behaviour | Over the 8-week period, the social app users showed significantly greater overall increases in weekly accelerometery-derived moderate to vigorous PA relative to the other three arms. Participants reported that the apps helped remind and motivate them to increase their PA levels as well as sit less throughout the day. | The results provide initial support for use of a smartphone-delivered social frame in the early induction of both PA and sedentary behaviour changes. The information obtained also sets the stage for further investigation of subgroups that might particularly benefit from different motivationally framed apps in these two key health promotion areas. |

| Kirwan et al (2012)45 | Smartphone, website | PA | PA | Over the study period (90 days), the intervention group logged steps on an average of 62 days, compared with 41 days in the matched group. Use of the application was associated with an increased likelihood to log steps daily during the intervention period compared with those not using the application. | Using a smartphone application as an additional delivery method to a website-delivered PA intervention may assist in maintaining participant engagement and behaviour change. |

| Kohl et al (2013)54 | Internet-delivered intervention | Dietary behaviours, PA, alcohol use, smoking and condom use | Dietary behaviours and PA | According to health priorities, interventions are largely targeted at weight-related behaviours, such as PA and dietary behaviour. Eleven studies targeted weight management and they were on dietary behaviours and PA. The main aimed of these studies were weight loss; five reviews also included interventions on weight maintenance. Six studies included three or more behaviours. The other groups included studies aimed at PA, five reviews were on smoking and alcohol, respectively. Four papers combined alcohol and smoking, while three were on dietary behaviours. An additional manual search showed one study on condom use. | More research is needed on effective elements instead of effective interventions, with special attention to long-term effectiveness. The reach and use of interventions need more scientific input to increase the public health impact of internet-delivered Interventions. |

| Lara et al (2016)37 | Web-based platform | Diet, PA, social connection and anthropometric status | Diet, PA, social connection, BMI and waist circumference | ‘Eating well’ and ‘being social’ were the most visited modules. At interview, participants reported that diet and PA modules were important and acceptable within the context of healthy ageing. | The trial procedures and the LEAP (Living, Eating, Activity and Planning through retirement) intervention proved feasible and acceptable. Overall participants reported that the LEAP domains of ‘eating well’, were important for their health and well-being in retirement. |

| Laranjo et al (2014)17 | SNS | Fitness, sexual health, food safety, smoking and health promotion | Fitness (PA) | The study found a statistically significant positive effect of SNS interventions on behaviour change, boosting encouragement for future research in this area. | The study showed a positive effect of SNS interventions on health behaviour-related outcomes, but there was considerable heterogeneity. |

| Lee et al (2018)56 | Mobile apps | Diet, PA and overall healthy lifestyle improvement | Diet, PA and overall healthy lifestyle improvement | Across all studies, health outcomes were shown to be better for mobile app users compared with non-users. Mobile app-based health interventions may be an effective strategy for improving health promotion behaviours in the general population without diseases. | This study suggests that mobile app use is becoming commonplace for a variety of health-promoting behaviours in addition to PA and weight control. Future research should address the feasibility and effectiveness of using mobile apps for health promotion in developing countries. |

| Mackenzie et al (2015)36 | Email, reminder software, twitter | Reduced workplace sitting | Increased PA | Therefore, ‘completers’ demonstrated a range of levels of PA. In addition, ‘completers’ generally demonstrated positive health behaviours with 0% being smokers, over 50% eating five fruits or vegetables/day and almost 25% not drinking alcohol. | Evaluation of this intervention provides useful information to support participatory approaches during intervention development and the potential for more sustainable low-cost interventions. |

| Naimark et al (2015)20 | Web-based app | Nutrition and PA | Nutrition, PA, BMI and waist circumference | The app group increased their weekly duration of PA to the healthy range of more than 150 min a week, which may afford substantial health benefits, they lost more weight and had increased nutritional knowledge compared with the control group. | We showed a positive impact of a newly developed web-based app on lifestyle indicators during an intervention of 14 weeks. These results are promising in the app’s potential to promote a healthy lifestyle, although larger and longer duration studies are needed to achieve more definitive conclusions. |

| Rogers et al (2017)55 | Website internet-delivered intervention | Diet, PA, alcohol and tobacco use, mental health intervention, disease management, sexual health |

Diet and PA | The efficacy of the interventions for diet and PA, although significant, was modest (eg, 2.1 kg mean weight reduction compared with a 0.4 kg increase in controls). People who completed the internet intervention reduced their waist circumference by 2.6 cm, whereas people who did not complete the intervention added 0.3 cm to their waist circumference. | A wide range of evidence-based internet programme are currently available for health-related behaviours, as well as disease prevention and treatment. However, the majority of internet-delivered health interventions found to be efficacious in RCTs do not have websites for general use. Increased efforts to provide mechanisms to host ‘interventions that work’ on the web and to assist the public in locating these sites are necessary. |

| Schneider et al (2013)46 | Internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle programme | PA, fruit and vegetable consumption, smoking status, alcohol consumption | PA, fruit and vegetable consumption | Sending prompt 2 weeks after the first visit was more effective compared with using a longer time period, adding a preview of new website content to a standard prompt increased its effectiveness in persuading people to log in to the programme and sending a prompt with additional content after a 2-week period significantly increased programme log-ins compared with using a reactive approach in which no additional prompts were used. | The key findings suggest that boosting revisits to a CT programme benefits most from relatively short prompt timing. Furthermore, a preview of new website content may be added to a standard prompt to further increase its effectiveness in persuading people to log in to the programme. |

| Schneider et al (2013)46 | Internet-delivered computer-tailored intervention. | PA, fruit and vegetable intake, alcohol consumption and smoking behaviour | PA, fruit and vegetable intake, BMI, mental health status | Approximately 50% of all participants had a healthy body weight, 35% were overweight, and 10% were obese. In terms of PA, 21% with a minimum of 150-min exercise per week, whereas 46% and 69% were not adhering to the Dutch guidelines of fruit and vegetable intake, respectively. More than one-third (36%) complied with three lifestyle guidelines, while 1% of the respondents complied with none of these guidelines. Older and respondents with a higher educational degree, as well as respondents with relatively healthier lifestyle and a healthy BMI, were more likely to participate in the intervention. | The study concluded that there is need to put additional effort to ensure that at-risk individuals (low socioeconomic status and unhealthy lifestyle) have increase interest in a lifestyle intervention and they should also be encouraged to employ lifestyle intervention. |

| Stratton et al (2017)50 | Websites, smartphone and tablet apps. | Cognitive behavioural therapy, stress management, mindfulness-based approaches, | Stress management | The stress management interventions differed by whether delivered to universal or targeted groups with a moderately large effect size at both postintervention (g=0.64, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.85) and follow-up (g=0.69, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.33) in targeted groups, but no effect in unselected groups. | There is reasonable evidence that eHealth interventions delivered to employees may reduce mental health and stress symptoms postintervention and still have a benefit, although reduced at follow-up. |

| Tsai et al (2015)18 | Website | HPLP | HPLP, BMI, physical and mental component summary | The eHealth education intervention had the effect of significantly increasing nurses’ postintervention HPLP total scores, PCS, MCS and decreases in BMI. | Tailored eHealth education is an effective and accessible intervention for enhancing health-promoting behaviour among nurses. |

BMI, body mass index; EI, enhanced internet; FJV, fruit juice and vegetable; HPLP, Health-promoting lifestyle profile; ICT, information and communication technology; MCS, mental component summary; MMS, multimedia messaging service; PA, physical activity; PCS, physical component summary; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SI, standard internet; SMS, short messaging service; SNS, social networking siteWHPP, workplace health promotion programme; WIs, web-based interventions.;

Use of email and website,39 email, website and SMS,38 smartphone and website,45 50 and website only48 50 55 was reported only for PA behaviour. Three of the reviewed studies reported on smartphone apps, one in the form of an in-built accelerator44 and one on smartphone with website for PA behaviour.41 Fanning et al reported on use of mobile device, mobile software and SMS for PA.27 Websites, smartphone and tablet apps were reported to be used for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), stress management and mindfulness-based approaches.50 Five of the included studies reported on use of more than one form of ICT for more than one health behaviour.40 47 49 52 56 Computer-based information and communication technologies53 and internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle programme42 46 54 were reported to be used for more than one health behaviour, including PA, nutrition, alcohol use, smoking behaviour and condom use. Use of website only was reported for nutrition, PA, stress management, interpersonal relationship, spiritual growth, and health responsibility,18 and diet, PA and social connection.37

SNSs were reported for fitness, sexual health, food safety, smoking and health promotion,17 and for diet, PA, alcohol and tobacco use, mental health intervention, disease management and sexual health.55 A specific software programme aimed at reducing sedentary behaviour in the work place.47 Mackenzie et al reported use of email, software reminder and Twitter to reduce workplace sitting only,36 while a web-based app was used for nutrition and PA only.20 A comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviour was reported among female nurses only.18

Use of ICT for health-promoting lifestyle behaviours and health status

Use of any form of ICT increased participants’ PA behaviour,27 36 39–41 44 45 48 and health behaviour change17 20 47 52 53 56 (table 3). Use of ICT in health-promoting behaviour was reported to reduce weight,20 55 56 but Frank et al reported no significant difference in participants’ BMI and waist circumference.40 People that are likely to participate in an internet-delivered computer-tailored intervention are older individuals with higher educational level, relative healthier lifestyle and healthy BMI.42 For efficient use of internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle programme, a preview of new website content should be included in a standard prompt in addition to short prompt timing.46 Factors to be considered when planning intervention for ICT to be used for health-promoting lifestyle behaviours in the workplace are encouragements in the form of motivation from managers, time management, involvement of stakeholders in the designing of the intervention and reminders.38 Use of ICT has been documented to be effective in promoting health behaviours.50 53 55 Comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviours and ICT reduce BMI and improve physical and mental component summary.18 There is a need to examine the long-term effectiveness of ICT on health-promoting behaviours.54 To ascertain the effectiveness of ICT and comprehensive health-promoting behaviours in the prevention of diseases, there is a need to consider other health assessment parameters such as blood pressure and biochemical parameter instead of BMI alone.18

Discussion

We conducted a systematic scoping review of the available studies on the use of ICT for stress management, interpersonal relations, nutrition, self-actualisation/spiritual growth, health responsibility and PA lifestyle behaviours globally. Health-promoting lifestyle behaviours play an essential role in the prevention of diseases and quality of life.12 15 According to the WHO, to control NCDs it is important to reduce risk factors associated with them by adopting health-promoting lifestyle behaviours.2 Our systematic scoping review showed that various forms of ICT such as email, SNSs, websites, SMS or text messages, mobile phone app, smartphones, computers and MMS were used for a range of health-promoting lifestyle behaviours such as nutrition, PA, stress management, smoking cessation and reducing alcohol consumption. There was a paucity of data on interpersonal relationship, self-actualisation/spiritual belief, stress management and health responsibility. However, health-related lifestyle behaviours such as condom use, breast cancer prevention and sexually transmitted diseases prevention that could have incorporated into health responsibility lifestyle behaviour were not a primary research article.

Furthermore, our study reported that use of ICT for health promotion improves and enhances health-promoting behaviours. More particularly, use of ICT for comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviours was reported to result in a healthy BMI and to improve physical and mental health. However, BMI was the only physical health assessment parameter reported by the included studies. Factors such as time management, motivation and reminders are essential when designing health-promoting lifestyle behaviour for workers. There was only one primary study on the use of ICT and comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviour among women. Also, the quality assessment of the primary studies included was of moderate risk. It is of interest to know that no reports on LMICs were found in the included studies. Regarding population size, our systematic review reported wide population spreads from 26 to 16 948 across the study locations reported. This review showed that there is a dearth of knowledge on the use of ICT for comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle and health status.

ICT enhances the success of national health promotion and disease prevention programmes.57 Our study reported large population sizes, which demonstrates that public health promotion campaigns can be achieved through use of ICT58 since large populations can be involved in health promotion intervention programmes, which will potentially enhance achievement of the sustainable development goal of reducing premature deaths associated with NCDs to one-third by 2030.2 However, to reduce attrition rate in ICT use for health-promoting lifestyle behaviour intervention, one of our included studies reported that reminders are critical.38 Much attention has been given to PA, nutritional lifestyle behaviours and healthy weight, and this might be the possible reason why these two lifestyle behaviours were more pronounced in our findings. This might also be the reason why only BMI was assessed among all the physical health parameters that could be of importance to control and prevention of NCDs.2 These findings have implications for the control and prevention of NCDs in the near future.

One of the strengths of this study is the extensive literature searched and the rigorous process in selecting the included studies. Scoping review as conducted for this study is an approach that examines the extent, range and nature of research activity in a particular field to identify research gap.33 59 This is the first article that has examined ICT and comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviours among healthy adults, as the authors are not aware of any such others. We also conducted a methodological quality appraisal of the included primary research. Results in our study did not omit any country, as ‘country filter’ was not applied during the literature search. All the included articles reported on PA except one that reported only on stress management. Also, some articles reported on stress management, spiritual growth health responsibility and interpersonal relationships. Most of the included studies that reported on health responsibility-related lifestyle behaviours such as smoking cessation, reduced alcohol consumption, condom use, breast cancer prevention and sexually transmitted diseases prevention were systematically reviewed studies. However, none of the included studies reported on blood pressure or blood glucose level. Screening and early detection of NCDs are one way to prevent and control this demon called NCDs.2 In the next 30 years, there will be a 3.5-fold increase globally in deaths due to cardiovascular diseases,60 which are the leading cause of mortality and morbidity among all the NCDs.1–3 Highest premature deaths associated with NCDs are recorded in the LMICs.1 2 61 However, our scoping review showed scarcity in the use of ICT for comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviours research among healthy adults from these regions.

Some limitations of this study were as follows: first, inclusion of studies published in the English language between January 2007 and December 2018; second, the reference lists of the included articles were not examined, and no manual searches were performed; lastly, only electronic databases were extensively searched for the included studies.

Health-promoting lifestyle behaviour remains a crucial means of curbing the menace associated with NCDs.3 14–16 However, some people prefer to be busy with other issues of life rather than engaging in health-promoting lifestyle behaviour.14 38 Hence, only a few individuals adhere to healthy lifestyle behaviour despite the role it plays in chronic diseases prevention.14 36 There is need to explore other means of encouraging people to practise health-promoting lifestyle behaviours because it is a fact that prevention is better than cure. Literature showed that web-based interventions are effective in changing behaviour.20 With the increase in the burden of NCDs in LMICs,61 use of ICT to promote health behaviour lifestyle is the key determinant in the control and prevention of NCDs.58 There is an urgent need to assess the nature and form of ICT that can be effective in promoting health behaviours among healthy adults in LMICs, and in Africa in particular. In addition, there is need to explore use of ICT and comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle behaviours among healthy adults in LMICs where there is a gap in the primary study of these issues.

Conclusion

The findings from our study showed that ICT in relation to health-promoting lifestyle behaviour enhances health-promoting lifestyle behaviour and promotes physical and mental health. PA was assessed by all the included studies except for one that examined stress management. BMI was the only physical health parameter reported by one of the included studies. Factors such as time management, motivation and reminders are important when designing health-promoting lifestyle behaviour for the worker. None of the included studies reported on LMICs. There is a dearth of knowledge on a comprehensive health-promoting behaviour that can be beneficial in the control and prevention of NCDs. There is need to carry out primary studies on the use of ICT for a comprehensive health-promoting lifestyle, especially among ‘healthy’ adults in LMICs where there are alarming statistics on the mortality and disability associated with NCDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Mr Joseph Shehu for offering technical assistance related to information and communication technologies.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Ncama BP, Mooi N, Mashamba-Thompson TP.

Contributors: Dr EMJ-S conceptualised, designed the protocol and prepared the draft of the manuscript under the supervision of Professor BPN. Ms NM and Dr TPMT contributed to the methodology and data collection. All authors critically reviewed the draft version of the manuscript and gave approval for submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Ali MK, Jaacks LM, Kowalski AJ, et al. Noncommunicable diseases: three decades of global data show a mixture of increases and decreases in mortality rates. Health Aff 2015;34:1444–55. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO Noncommunicable diseases, 2017. Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs355/en/ [Accessed 27/05/2017].

- 3. Joseph-Shehu EM, Ncama BP. Evidence on health-promoting lifestyle practices and information and communication technologies: Scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014358 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray CJ, Lopez AD, World Health Organization . The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Summary 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mokdad A. Global non-communicable disease prevention: building on success by addressing an emerging health need in developing countries. Journal of Health Specialties 2016;4 10.4103/1658-600X.179820 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. The Lancet 2016;388:1311–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30383-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ulla Diez SM, Perez-Fortis A. Socio-Demographic predictors of health behaviors in Mexican college students. Health Promot Int 2010;25:85–93. 10.1093/heapro/dap047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El Ansari W, Stock C, John J, et al. Health promoting behaviours and lifestyle characteristics of students at seven universities in the UK. Cent Eur J Public Health 2011;19:197–204. 10.21101/cejph.a3684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. The Lancet 2011;377:1438–47. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60393-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burniston J, Eftekhari F, Hrabi S, et al. Health behaviour change and lifestyle-related condition prevalence: comparison of two epochs based on systematic review of the physical therapy literature. Hong Kong Physiotherapy Journal 2012;30:44–56. 10.1016/j.hkpj.2012.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sorour AS, Kamel WW, Abd El- Aziz EM, et al. Health promoting lifestyle behaviors and related risk factors among female employees in Zagazig City. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 2014;4:42–51. 10.5430/jnep.v4n5p42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tol A, Tavassoli E, Shariferad GR, et al. Health-Promoting lifestyle and quality of life among undergraduate students at school of health, Isfahan University of medical sciences. J Educ Health Promot 2013;2:11 10.4103/2277-9531.108006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Turkmen M, Ozkan A, Murat K, et al. Investigation of the relationship between physical activity level and healthy life-style behaviors of academic staff. Educational Research and Reviews 2015;10:577–81. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shehu RA, Onasanya SA, Onigbinde TA, et al. Lifestyle, fitness and health promotion initiative of the University of Ilorin, Nigeria: an educational media intervention. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management 2013;6:273–9. 10.4314/ejesm.v6i3.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bully P, Sánchez Álvaro, Zabaleta-del-Olmo E, et al. Evidence from interventions based on theoretical models for lifestyle modification (physical activity, diet, alcohol and tobacco use) in primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Med 2015;76:S76–93. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2010:406–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laranjo L, Arguel A, Neves AL, et al. The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsai Y-C, Liu C-H. An eHealth education intervention to promote healthy lifestyles among nurses. Nurs Outlook 2015;63:245–54. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greene GW, Fey-Yensan N, Padula C, et al. Change in fruit and vegetable intake over 24 months in older adults: results of the senior project intervention. Gerontologist 2008;48:378–87. 10.1093/geront/48.3.378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Naimark JS, Madar Z, Shahar DR. The impact of a web-based APP (eBalance) in promoting healthy lifestyles: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research 2015;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christensson P. Ict definition, 2010. Available: https://techterms.com [Accessed 9 September 2017].

- 22. Barak A, Hen L, Boniel-Nissim M, et al. A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of Internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. J Technol Hum Serv 2008;26:109–60. 10.1080/15228830802094429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilkinson N, Ang RP, Goh DH. Online video game therapy for mental health concerns: a review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2008;54:370–82. 10.1177/0020764008091659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, McCant F, et al. Hypertension intervention nurse telemedicine study (hints): testing a multifactorial tailored behavioral/educational and a medication management intervention for blood pressure control. Am Heart J 2007;153:918–24. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klasnja P, Pratt W. Healthcare in the pocket: mapping the space of mobile-phone health interventions. J Biomed Inform 2012;45:184–98. 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muessig KE, Pike EC, LeGrand S, et al. Mobile phone applications for the care and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases: a review. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e1 10.2196/jmir.2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fanning J, Mullen SP, McAuley E. Increasing physical activity with mobile devices: a meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e161 10.2196/jmir.2171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Free C, Phillips G, Galli L, et al. The effectiveness of mobile-health technology-based health behaviour change or disease management interventions for health care consumers: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001362 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Johns MM, et al. Innovative recruitment using online networks: lessons learned from an online study of alcohol and other drug use utilizing a web-based, respondent-driven sampling (webRDS) strategy. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2012;73:834–8. 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Walker SN, Sechrist KR, Pender NJ. Health Promotion Model - Instruments to Measure Health Promoting Lifestyle : HealthPromoting Lifestyle Profile [HPLP II] (Adult Version), 1995. Available: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/85349 [Accessed 08 July 2015].

- 31. Joseph-Shehu E, Ncama B. Health-Promoting lifestyle behaviour of workers: a systematic review. Occupational Health Southern Africa 2019;25:60–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nassar OS, Shaheen AM. Health-Promoting behaviours of university nursing students in Jordan. Health 2014;06:2756–63. 10.4236/health.2014.619315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, et al. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews: archived by WebCite®, 2011. Available: http://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ

- 36. Mackenzie K, Goyder E, Eves F. Acceptability and feasibility of a low-cost, theory-based and co-produced intervention to reduce workplace sitting time in desk-based university employees. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1294–94. 10.1186/s12889-015-2635-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lara J, O’Brien N, Godfrey A, et al. Pilot randomised controlled trial of a web-based intervention to promote healthy eating, physical activity and meaningful social connections compared with usual care control in people of retirement age recruited from workplaces. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159703–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0159703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bardus M, Blake H, Lloyd S, et al. Reasons for participating and not participating in a e-health workplace physical activity intervention. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 2014;7:229–46. 10.1108/IJWHM-11-2013-0040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ammann R, Vandelanotte C, De Vries H, et al. Can a website-delivered computer-tailored physical activity intervention be acceptable, usable, and effective for older people? Health Education & Behavior 2012;1090198112461791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Frank LL, McCarthy MS. Telehealth coaching: impact on dietary and physical activity contributions to bone health during a military deployment. Mil Med 2016;181:191–8. 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guertler D, Vandelanotte C, Kirwan M, et al. Engagement and nonusage attrition with a free physical activity promotion program: the case of 10,000 steps Australia. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e176 10.2196/jmir.4339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schneider F, Schulz DN, Pouwels LHL, et al. The use of a proactive dissemination strategy to optimize reach of an internet-delivered computer tailored lifestyle intervention. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1 10.1186/1471-2458-13-721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carr LJ, Leonhard C, Tucker S, et al. Total worker health intervention increases activity of sedentary workers. American journal of preventive medicine 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. King AC, Hekler EB, Grieco LA, et al. Effects of three Motivationally targeted mobile device applications on initial physical activity and sedentary behavior change in midlife and older adults: a randomized trial. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156370–16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kirwan M, Duncan MJ, Vandelanotte C, et al. Using smartphone technology to monitor physical activity in the 10,000 steps program: a matched case–control trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e55 10.2196/jmir.1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schneider F, de Vries H, Candel M, et al. Periodic email prompts to re-use an internet-delivered computer-tailored lifestyle program: influence of prompt content and timing. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e23 10.2196/jmir.2151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Howarth A, Quesada J, Silva J, et al. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: a systematic review. Digital Health 2018;4 10.1177/2055207618770861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Carr LJ, Dunsiger SI, Lewis B, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing an Internet physical activity intervention for sedentary adults. Health Psychology 2013;32:328–36. 10.1037/a0028962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bardus M, Smith JR, Samaha L, et al. Mobile phone and web 2.0 technologies for weight management: a systematic scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e259 10.2196/jmir.5129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stratton E, Lampit A, Choi I, et al. Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for reducing mental health conditions in employees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0189904 10.1371/journal.pone.0189904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bert F, Giacometti M, Gualano MR, et al. Smartphones and health promotion: a review of the evidence. J Med Syst 2014;38:1–11. 10.1007/s10916-013-9995-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Buhi ER, Trudnak TE, Martinasek MP, et al. Mobile phone-based behavioural interventions for health: a systematic review. Health Educ J 2013;72:564–83. 10.1177/0017896912452071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hou S-I, Charlery S-AR, Roberson K. Systematic literature review of internet interventions across health behaviors. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 2014;2:455–81. 10.1080/21642850.2014.895368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kohl LFM, Crutzen R, de Vries NK. Online prevention aimed at lifestyle behaviors: a systematic review of reviews. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e146 10.2196/jmir.2665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rogers MAM, Lemmen K, Kramer R, et al. Internet-Delivered health interventions that work: systematic review of meta-analyses and evaluation of website availability. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e90 10.2196/jmir.7111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lee M, Lee H, Kim Y, et al. Mobile app-based health promotion programs: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2838 10.3390/ijerph15122838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haluza D, Jungwirth D. Ict and the future of health care: aspects of health promotion. Int J Med Inform 2015;84:48–57. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Honka A, Kaipainen K, Hietala H, et al. Rethinking health: ICT-enabled services to empower people to manage their health. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng 2011;4:119–39. 10.1109/RBME.2011.2174217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Assaram S, Magula NP, Mewa Kinoo S, et al. Renal manifestations of HIV during the antiretroviral era in South Africa: a systematic scoping review. Syst Rev 2017;6:200 10.1186/s13643-017-0605-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cipriano G, Neves LMT, Cipriano GFB, et al. Cardiovascular disease prevention and implications for worksite health promotion programs in Brazil. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014;56:493–500. 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Alwan A, MacLean DR, Riley LM, et al. Monitoring and surveillance of chronic non-communicable diseases: progress and capacity in high-burden countries. The Lancet 2010;376:1861–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61853-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029872supp001.pdf (23.4KB, pdf)