Abstract

Introduction

Global prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality is increasing. Treatments are available but can only be implemented if individuals at risk are identified. General health checks have been suggested to facilitate this process.

Objectives

To examine the long-term effect of population-based general health checks on CVD and all-cause mortality.

Design and setting

The Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project (EHPP) is a parallel randomised controlled trial in a Danish primary care setting.

Participants

The EHPP enrolled individuals registered in the Civil Registration System as (1) inhabitants of Ebeltoft municipality, (2) registered with a general practitioner (GP) participating in the study and (3) aged 30–49 on 1 January 1991. A total of 3464 individuals were randomised as invitees (n=2000) or non-invitees (n=1464). Of the invitees, 493 declined. As an external control group, we included 1 511 498 Danes living outside the municipality of Ebeltoft.

Interventions

Invitees were offered a general health check and, if test-results were abnormal, recommended a 15–45 min consultation with their GP. Non-invitees in Ebeltoft received a questionnaire at baseline and were offered a general health check at year 5. The external control group, that is, the remaining Danish population, received routine care only.

Outcome measures

HRs for CVD and all-cause mortality.

Results

Every individual randomised was analysed. When comparing invitees to non-invitees within the municipality of Ebeltoft, we found no significant effect of general health checks on CVD (HR=1.11 (0.88; 1.41)) or all-cause mortality (HR=0.93 (0.75; 1.16)). When comparing invitees to the remaining Danish population, we found similar results for CVD (adjusted HR=0.99 (0.86; 1.13)) and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR=0.96 (0.85; 1.09)).

Conclusion

We found no effect of general health checks offered to the general population on CVD or all-cause mortality.

Trial registration number

NCT00145782; 2015-57-0002; 62908, 187.

Keywords: preventive medicine, public health, primary care, organisation of health services, epidemiology, hypertension

Strengths and limitations of this study.

24-year duration with near-complete follow-up decreases risk of selection bias.

The randomised controlled trial design minimises risk of confounding.

Objective outcome measures—cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality—decreases risk of misclassification.

Secondary randomisation of controls in 2006 decreases statistical power.

Introduction

Global prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality, such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes, is increasing.1–4 Early detection and intervention is possible and may reduce CVD and all-cause mortality. One approach is the general health check which is a multi-modal screening of risk factors that can be applied to the general population. Such screening is already implemented in both the UK and Japan.5 6

Several randomised controlled trials of general health checks have been undertaken and found significant effects on cardiovascular risk factors,7–11 but small or no effect on CVD and all-cause mortality.8 12 13 Among those is the Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project (EHPP) which was initiated in 1991 and included 2.000 individuals from the general population in a small municipality of Denmark.14 In this project, cardiovascular risk factors were significantly reduced in the intervention groups compared with the control group after 5 years.9 15 After 8 years of follow-up, a 20% decrease in all-cause mortality was found in the intervention groups, although non-significant.12 No effects were found on CVD. As the included population was a middle-aged population with relatively low risk of CVD and death, a longer follow-up period is necessary in order to investigate whether general health checks do have an effect on CVD and all-cause mortality.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the long-term effects of population based general health checks on CVD and all-cause mortality. We accomplished this by intention to screen analysis comparing invitees in the EHPP to non-invitees 24 years after randomisation. Due to possible spill-over effects between invitees and non-invitees, we performed an additional adjusted analysis in which the remaining Danish population of the same age was used as a comparator to the invitees.

Methods

Participants and setting

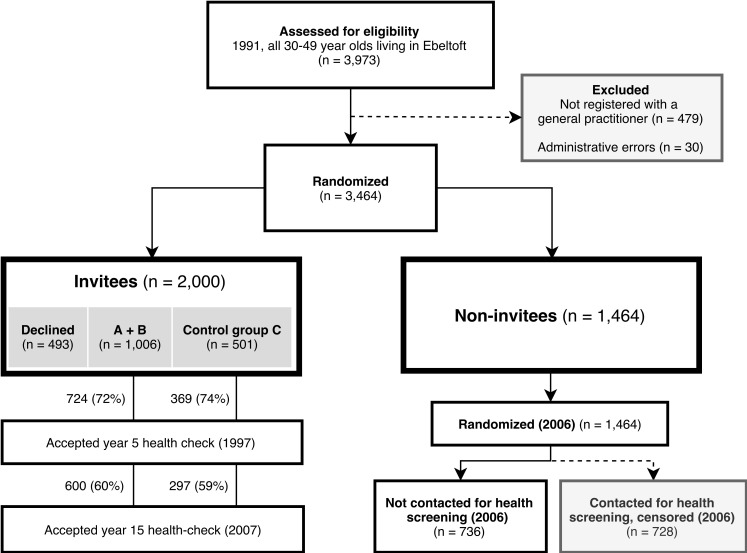

Everyone (3464) registered in the Civil Registration System as (1) inhabitants of Ebeltoft municipality, (2) registered with a general practitioner (GP) participating in the study and (3) aged 30–49 on 1 January 1991 were eligible for inclusion. Ebeltoft municipality was covered by nine GPs, all of whom agreed to participate. Randomisation was completed in two stages (figure 1). In the first stage, proportional stratification on date of birth and GP was applied to draw a random sample of 2000 to be invited to the EHPP (invitees); 1464 were not invited (non-invitees) (figure 1). The invitees and non-invitees constitute the main parallel comparison in the present paper.

Figure 1.

Allocation and participation in the Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project. The compared groups, invitees and non-invitees, are highlighted by a heavier outline. Participants contacted in 2006 were censored on 31 January 2005. Percentages are proportions of initial allocation size.

In the second stage, all invitees who returned questionnaires and agreed to a general health check underwent 1:1:1 proportional randomisation by GP, gender, age, body mass index (BMI) and cohabitation status into three arms: intervention A, intervention B and the control group C (figure 1). As part of a separate study, a third randomisation of non-invitees was completed in 2006. In the present study, participants contacted in 2006 were censored on 31 December 2005.

All randomisations were done independently of the investigators by a statistician employed by Aarhus County. Sample size was pragmatically determined by the number of inhabitants of Ebeltoft and the workload that could be put on the local practices. No further contact was attempted for individuals that withdrew from the study and, as such, no information on why they withdrew was registered. However, outcome data was still acquired through the registers. For the comparison of invitees to the remaining Danish population, all inhabitants of Denmark aged 30–49 on 1 January 1991 were derived from the Civil Registration System.

Interventions

Invitees were mailed a combined invitation and questionnaire containing questions on health, lifestyle, psychosocial status, important life events and whether they wanted a general health check. Intervention A was offered a general health check at baseline, one and 5 years followed by mailed feedback in layman’s terms (figure 1). If test-results were outside predefined acceptable ranges, a recommendation for a 10–15 min consultation with the respective GP was mailed. Intervention B was offered the same and, irrespective of the general health check results, a 45 min baseline consultation with their GP to discuss health problems and inspire healthy lifestyle changes. Controls received a questionnaire at baseline and a general health check at year 5.

General health check methodology

The general health checks included an assessment of blood pressure, cholesterol, smoking, family history, BMI, ECG, liver enzymes, creatinine, blood glucose, spirometry, urinary dipstick for albumin and blood, CO concentration in expired air, physical endurance, vision, hearing and an optional test for HIV.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes for the present study were CVD and mortality. CVD was defined as acute myocardial infarction (International Classification of Disease revision 8 (ICD8)8: 4100–4199, ICD10: I21–I22), chronic heart disease (ICD8: 4110–4139, ICD10: I20+I23–I25), cerebrovascular haemorrhage (ICD8: 4300–4319, ICD10: I60–I62) or other cerebrovascular disease (ICD8: 4320–4389, ICD10: I63–I68) and was derived from the Danish National Patient Registry. Date of death was acquired from The Civil Registration System.

Covariates

Data on hospital discharge diagnosis was acquired from The National Patient Register, while data on gender, age at baseline and ethnicity was collected from The Civil Registration System. Data on cohabitation status, household size, income, occupation and education was acquired from The Danish Integrated Database for Labour Market Research. All baseline data were acquired for 1 January 1991.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were analysed by frequencies and proportions, medians and interquartile intervals (25th, 75th percentile) as appropriate. Statistical testing was completed with chi-squared tests for binary variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. In comparisons on baseline characteristics between groups, individuals with missing data were excluded on each characteristic.

Groups were compared via Cox-regression on time to first CVD-event or death by intention to screen. Time at risk of CVD was calculated from date of inclusion to date of first CVD event, date of death from other causes or 31 December 2014, whichever came first. Time at risk for mortality was calculated from date of inclusion to date of death or 31 December 2014. Participants contacted for health screening in 2006 were censored on 31 December 2005.

In addition to crude analyses, we completed an adjusted analysis for the comparison to the Danish population, which was adjusted for the following confounders: gender, age and relationship status at baseline, household size, income, early retirement pension, educational level, immigration status and comorbidity. If any individual had missing data on any of these variables, they were excluded from the adjusted analysis. To estimate comorbidity, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated based on hospital discharge diagnoses (online supplementary appendix A—Translation of disease categories in the Charlson comorbidity index into discharge diagnoses) and dichotomised into >0 (yes) or 0 (no) as no further predictive power was gained from categorical analysis. The proportional hazards assumption was tested and fulfilled in all Cox-regression analyses.

bmjopen-2019-030400supp001.pdf (44.6KB, pdf)

All analyses were performed in Stata V.15. We consider p≤0.05 as statistically significant.

Registration and data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Danish Health Data Authority. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data; they were used under license for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors on reasonable request and with permission of The Danish Health Data Authority and Statistics Denmark.

Patient and public involvement

The study was conceived and designed, and participants were recruited without direct patient involvement, however, both design and execution were monitored and implemented by a steering committee with 13 members, four of which were from the general public. The scientific publication of the present results will be followed up by dissemination in public local and national media. No direct contact will be taken to study participants, as they did not provide consent for further contact. The burden of intervention was assessed indirectly by the proportion of invitees which declined participation, but no qualitative information was gathered from patients.

Results

Study population

All inhabitants of Ebeltoft municipality were examined for eligibility; 3973 individuals were aged 30–49 on 1 January 1991, 87% of which were registered with a GP in the municipality and thus eligible and enrolled (n=3464); 30 individuals were lost due to administrative errors; 2000 individuals were randomised for invitation and 1464 for no invitation. Initial questionnaires were sent out on 1 September 1991. From this point on, general health check participation rates in the A to C groups were similar. All individuals were analysed on CVD and mortality as follow-up data was available through the registers.

Comparing invitees to non-invitees

Baseline characteristics were comparable between invitees and non-invitees. The majority were married, had a low degree of comorbidity and a minority were immigrants (table 1). There were no significant differences in first event distributions between groups (table 2). Cerebrovascular haemorrhage had a low cumulative first event proportion (0.8%), whereas ischaemic heart disease was the disease with the highest cumulative proportion (4.4%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of invitees and non-invitees in the EHPP and the Danish population Baseline: 1 January 1991

| EHPP | Danish population | ||

| Invitees (n=2000) |

Non-invitees (n=1464) |

(n=1 511 498) | |

| Male, n (%) | 1032 (52) | 743 (51) | 769 971 (51) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 41 (36; 46) | 41 (36; 46) | 41 (36; 46) |

| Married, n (%) | 1213 (61) | 897 (62) | 996 953 (66) |

| Single, n (%) | 212 (11) | 161 (11) | 162 486 (11) |

| Income, 1000 Danish kroner, median (IQR) | 108 (87; 131) | 109 (86; 130) | 110 (90; 133) |

| Early retirement pension, n (%) | 86 (4) | 59 (4) | 70 944 (5) |

| 0–10 years education, n (%) | 670 (35) | 475 (34) | 495 518 (34) |

| Immigrants, n (%) | 65 (3) | 59 (4) | 75 953 (5) |

| Comorbidity*, n (%) | 96 (5) | 63 (4) | 65 553 (4) |

| CVD†, n (%) | 15 (1) | 13 (1) | 13 345 (1) |

Missing data were 3% for 0–10 years education,<1% for all other categories.

*Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥1.

†Non-fatal CVD event between 01/01/1979 and baseline (01/01/1991).

CVD, cardiovascular disease; EHPP, Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project.

Table 2.

Distribution of first CVD event and death among invitees and non-invitees after 24 years of follow-up in the EHPP

| Invitees (n=2000) |

Non-invitees (n=1464*) | Total (n=3464) |

|

| AMI†, n (%) | 50 (2.5) | 29 (2.0) | 79 (2.3) |

| CHD‡, n (%) | 90 (4.5) | 61 (4.2) | 151 (4.4) |

| Cerebrovascular haemorrhage,§ n (%) | 13 (0.7) | 16 (0.7) | 29 (0.8) |

| Other cerebrovascular disease,¶ n (%) | 50 (2.5) | 46 (3.1) | 96 (2.8) |

| Death, n (%) | 247 (12.4) | 141 (9.6) | 388 (11.2) |

Percentages are proportions of total number of individuals in the column.

*Non-invitees contacted for health screening during secondary randomisation in 2006 (n=728) were censored on 31 December 2005.

†Acute Myocardial Infarction (ICD8: 4100–4199, ICD10: I21–I22).

‡Chronic Heart Disease (ICD8: 4110–4139, ICD10: I20 +I23–I25).

§(ICD8: 4300–4319, ICD10: I60–I62).

¶(ICD8: 4320-4389, ICD10: I63–I68).

CVD, cardiovascular disease; EHPP, Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project.

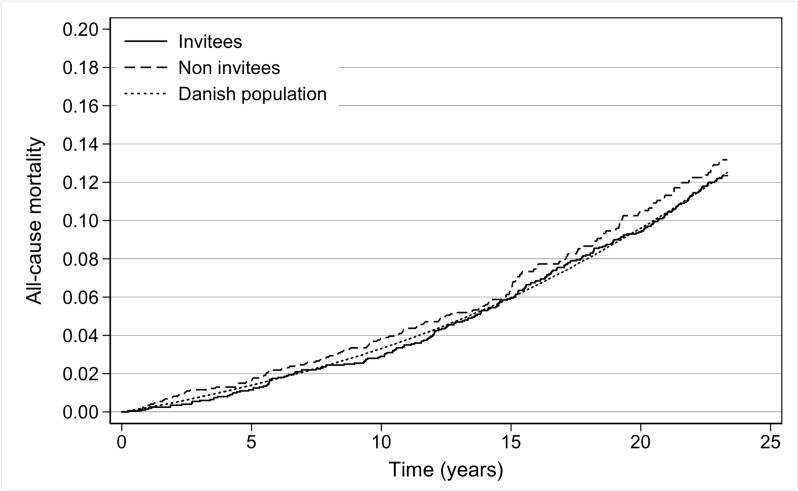

No significant difference between invitees and non-invitees in risk of CVD (HR=1.11 (0.88; 1.41)) or mortality (HR=0.93 (0.75; 1.16)) was found (table 3), as illustrated in figure 2.

Table 3.

HRs for CVD and all-cause mortality comparing invitees to non-invitees in the EHPP and comparing invitees in the EHPP to the remaining Danish population after 24 years of follow-up

| Invitees vs non-invitees HR (95% CI) |

Invitees vs Danish population HR (95% CI) |

||

| Crude | Crude | Adjusted | |

| CVD | 1.11 (0.88 to 1.41) | 0.99 (0.87 to 1.13) | 0.99 (0.86 to 1.13) |

| All-cause mortality | 0.93 (0.75 to 1.16) | 0.98 (0.87 to 1.12) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.09) |

Invitees (n=2000). Non-invitees (n=1464). Danish population (n=1 511 498). Adjusted for gender, age at baseline, relationship status, household size, income, occupation, education and Comorbidity at baseline. All individuals with missing data were excluded from the adjusted analyses. CVD events were defined as acute myocardial infarction (ICD8: 4100–4199, ICD10: I21–I22), chronic ceart disease (ICD8: 4110–4139, ICD10: I20+I23–I25), cerebrovascular haemorrhage (ICD8: 4300–4319, ICD10: I60–I62) or other cerebrovascular disease (ICD8: 4320–4389, ICD10: I63–I68).

CVD, cardiovascular disease; EHPP, Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project.

Figure 2.

Cumulative all-cause mortality rate comparing invitees and non-invitees in the Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project and the Danish population.

Comparing invitees to the remaining Danish population

The invitees were comparable to the remaining Danish population on most examined characteristics (table 1). Invitees were less likely to be married or immigrants compared with the remaining Danish population. Using the remaining Danish Population (n=1 511 499) as an external control group resulted in only minor changes to our point estimates for CVD (crude HR=0.99 (0.87; 1.13), adjusted HR=0.99 (0.86; 1.13)) and mortality (crude HR=0.98 (0.87; 1.12), adjusted HR=0.96 (0.85; 1.09)).

Discussion

Principal findings

We performed a post hoc intention to screen analysis in a 24-year follow-up of the EHPP. We found that general health checks offered to the general population aged 30–49 did not result in statistically significant decreases in CVD or all-cause mortality.

Spill-over effects are unlikely to explain this lack of effect since no effect on CVD or all-cause mortality was found when comparing invitees to the remaining Danish population.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

The present study contributes to the field through its main strengths. First, the gold-standard of the randomised controlled trial with intention to screen analysis decreases the risk of confounding. In addition to this, the geographical and social proximity of invitees and non-invitees increases the odds of comparable sociodemographics, thus further decreasing confounding. Second, the potential latency of effects is essentially eliminated by a long follow-up of 24 years which also increases statistical power. Third, near-complete follow-up through national registers covering both public and private hospitals was accomplished, strongly decreasing the risk of selection bias. Furthermore, the use of registry data reduces the risk of information bias as the Danish registers are highly valid.16

Limitations

The proximity of invitees and non-invitees is also a limitation. It increases the risk of spill-over effects, potentially biasing the results towards no effect. Therefore, we compared invitees to the remaining Danish population as an external control group. However, this comparison might introduce confounding. As invitees and the remaining Danish population were highly similar on the baseline characteristics registered, the risk of confounding is believed to be small.

Another limitation is the proportion of invitees that were not offered a general health check. This included one quarter of invitees that were randomised to the control group and were not offered a general health check at baseline, and another quarter that declined to participate. This limitation may result in underestimation of the potential effects of general health checks. For the comparison between invitees and the general Danish population, however, spill-over effects may decrease this limitation.

Lastly, we did not acquire information on emigration. This limitation is believed to be small, as emigration rates are highly likely to be similar between groups, more than half of emigrants return to Denmark and the emigration rate was less than 4% in a highly similar dataset.

Generalisability

Effectiveness of screening depends on the probability of going undiagnosed without screening and the effectiveness of treatment. In both regards, the study conditions in Ebeltoft are likely to be comparable to the rest of Denmark in the same period and probably even quite representative of the industrialised world as a whole. In that sense, the generalisability of study results can be considered high.

However, Denmark has a well-developed universal healthcare system free of charge. This decreases the probability of going undiagnosed without screening, rendering general health checks more effective in other countries. On the other hand, general health checks might be more effective in Denmark due to other factors: Participation rates are likely larger than countries where patients must pay for consultations and gold-standard treatment is available at no or very small cost to patients.

Further, it must be considered whether the effect of the intervention has changed since the initiation of the EHPP. During this period, the treatment of CVD risk factors has been substantially improved and/or intensified (eg, the widespread use of statins).17 Given this progress, general health checks could be more effective today than this study’s results imply, although later interventions hold no clear indication that this is the case.13

Strengths and weaknesses compared with other studies

Previous follow-up studies of the EHPP9 and other studies10 11 18–20 found effects of general health checks on risk factors, but no effects on CVD or all-cause mortality.12 21 This discrepancy appears paradoxical but may be explained by insufficient power; effects on CVD and all-cause mortality are expected to be smaller than effects on risk factors and therefore require greater statistical power to be demonstrated. Further, effect sizes are decreased by applying the general health check to the general population; in the EHPP, only 11,4% of the invited group had CVD risk-factors at baseline that indicated lifestyle interventions and/or drug treatment.14

The most well-powered study (Inter99) also found no effect.13 This may be due to Inter99 having no formal arrangements with GPs to ensure follow-up of patients with detected risk factors, essentially making it a pragmatic trial. The present study was conducted in collaboration with GPs, increasing the strength of intervention and has 24 years of follow-up, increasing statistical power.

Interpretation

This study’s results are not statistically significant. However, non-significant results are not the same as proof of the null hypothesis. Based on our findings, we cannot exclude a clinically meaningful reduction of all-cause mortality-risk of 25%.

Interestingly, the opposite is true for CVD. Comparing invitees to non-invitees, our best estimate is a 10% increase in diagnosis of CVD. However, incidence of diagnosis is closely related to, but not the same as, incidence of disease. Screening may increase diagnosis of CVD due to increased awareness, without an actual increase in disease. This may obscure a potential benefit of general health checks on CVD, biasing the results towards null. Such an effect does not apply to all-cause mortality, as diagnosis of death correlates almost perfectly with death.

However, since the comparison of invitees in the EHPP to the Danish population shows no effect on either measure and considering the repeated null-results in the literature, it appears unlikely that general health checks affect CVD or all-cause mortality. Policy-makers should consider whether the large expenditure of routine general health checks is justified.

Since general health checks offered to the general population appear ineffective and inefficient, it does not seem the most productive way of enhancing disease prevention.

Conclusion

In this 24-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial, we found that general health checks offered to the general population aged 30–49 years do not have effects on CVD and all-cause mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following members of the general public for participation in the EHPP steering committee: Bodil Helmer, Bent De Fine Olivarius, Ove Mikkelsen and Viggo Tjørnemose.

Footnotes

Contributors: MB: interpretation of data, drafting and revising manuscript. PD: acquisition and interpretation of data, critical revisions. NHB: statistical analyses and critical revisions. E-MD: acquisition and interpretation of data, critical revisions. MF-G: contributions to statistical analyses, significant revisions to manuscript. TL: study conception, interpretation of data and critical revisions.

Funding: Financial support for register-based investigations in relation to the Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project was given by the County Health Insurance Office Aarhus, the Danish College of General Practitioners (Sara Krabbe scholarship), the Danish College of General Practitioners (Lundbeck scholarship), the Danish Research Foundation for General Practice, the General Practitioners Education and Development Fund, the Health Promotion Council of Aarhus, the Health Insurance Fund, the Lundbeck Foundation for scientific research grant to GPs, the Ministry of Health Foundation for Research and Development, the Danish Medical Research Council (9801336), and the Danish Heart Foundation (97–2-F-22515).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Permission to conduct the EHPP was given by the Scientific Ethical Committee of Aarhus County (J. no. 1990/1966).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. . Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control. Circulation 2016;134:441–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lonardo A, Byrne CD, Caldwell SH, et al. . Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:1388–9. 10.1002/hep.28584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442–30. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ebrahim S, Taylor F, Ward K, et al. . Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;226 10.1002/14651858.CD001561.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakanishi N, Tatara K, Fujiwara H. Do preventive health services reduce eventual demand for medical care? Soc Sci Med 1996;43:999–1005. 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00016-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chisholm JW. The 1990 contract: its history and its content. BMJ 1990;300:853–6. 10.1136/bmj.300.6728.853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang KC-M, Lee JT, Vamos EP, et al. . Impact of the National health service health check on cardiovascular disease risk: a difference-in-differences matching analysis. Can Med Assoc J 2016;188:E228–38. 10.1503/cmaj.151201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Si S, Moss JR, Sullivan TR, et al. . Effectiveness of general practice-based health checks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e47–53. 10.3399/bjgp14X676456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Engberg M, Christensen B, Karlsmose B, et al. . General health screenings to improve cardiovascular risk profiles: a randomized controlled trial in general practice with 5-year follow-up. J Fam Pract 2002;51:546–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baumann S, Toft U, Aadahl M, et al. . The long-term effect of a population-based life-style intervention on smoking and alcohol consumption. The Inter99 Study--a randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2015;110:1853–60. 10.1111/add.13052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baumann S, Toft U, Aadahl M, et al. . The long-term effect of screening and lifestyle counseling on changes in physical activity and diet: the Inter99 Study - a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12 10.1186/s12966-015-0195-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krogsbøll LT, Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;46:603–135. 10.1002/14651858.CD009009.pub3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jorgensen T, Jacobsen RK, Toft U, et al. . Effect of screening and lifestyle counselling on incidence of ischaemic heart disease in general population: Inter99 randomised trial. BMJ 2014;348:g3617–7. 10.1136/bmj.g3617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lauritzen T, Leboeuf-Yde C, Lunde IM, et al. . Ebeltoft project: baseline data from a five-year randomized, controlled, prospective health promotion study in a Danish population. Br J Gen Pract 1995;45:542–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lauritzen T, Jensen MSA, Thomsen JL, et al. . Health tests and health consultations reduced cardiovascular risk without psychological strain, increased healthcare utilization or increased costs. An overview of the results from a 5-year randomized trial in primary care. The Ebeltoft health promotion project (EHPP). Scand J Public Health 2008;36:650–61. 10.1177/1403494807090165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, et al. . The Danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vancheri F, Backlund L, Strender L-E, et al. . Time trends in statin utilisation and coronary mortality in Western European countries. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010500 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wood DA, Kinmonth AL, Davies GA, et al. . Randomised controlled trial evaluating cardiovascular screening and intervention in general practice: principal results of British family heart study. family heart Study Group. BMJ 1994;308:313–20. 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toft U, Pisinger C, Aadahl M, et al. . The impact of a population-based multi-factorial lifestyle intervention on alcohol intake: the Inter99 study. Prev Med 2009;49:115–21. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pisinger C, Ladelund S, Glümer C, et al. . Five years of lifestyle intervention improved self-reported mental and physical health in a general population: the Inter99 study. Prev Med 2009;49:424–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cochrane T, Davey R, Iqbal Z, et al. . NHS health checks through general practice: randomised trial of population cardiovascular risk reduction. BMC Public Health 2012;12:944 10.1186/1471-2458-12-944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030400supp001.pdf (44.6KB, pdf)