Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

Lifestyle may affect observed associations between glucocorticoid use and adverse events. This study aimed to investigate whether lifestyle differ according to use of systemic glucocorticoids.

Design

Population-based cross-sectional study.

Setting

The Central Denmark Region.

Participants

30 245 adults (≥25 years of age) who participated in a questionnaire-based public health survey in 2010.

Outcome measures

Systemic glucocorticoid use was categorised as never use, current use (prescription redemption ≤90 days before completing the questionnaire), recent use (prescription redemption 91–365 days before completing the questionnaire), former use (prescription redemption >365 days before completing the questionnaire) and according to cumulative dose expressed in prednisolone equivalents (<100, 100–499, 500–999, 1000–1999, 2000–4999, ≥5000 mg). We computed the prevalence of lifestyle factors (body mass index, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity and dietary habits) according to glucocorticoid use. We then estimated age-adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs, comparing the categories of glucocorticoid users versus never users. All analyses were stratified by sex.

Results

Of the 30 245 participants (53% women, median age 53 years), 563 (1.9%) were current users, 885 (2.9%) were recent users, 3054 (10%) were former users and 25 743 (85%) were never users. Ever users of glucocorticoids had a slightly higher prevalence of obesity than never users (18% vs 14%, aPR=1.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.5 in women and 17% vs 15%, aPR=1.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.4 in men). In women, ever users of glucocorticoids had a slightly lower prevalence of high-risk alcohol consumption compared with never users (17% vs 20%, aPR=0.8, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.0). Smoking, diet and physical activity did not differ substantially according to use of glucocorticoids.

Conclusion

Our study provides a framework for quantifying potential uncontrolled confounding by lifestyle factors in studies of systemic glucocorticoids.

Keywords: glucocorticoids, body mass index, alcohol drinking, exercise, smoking, diet

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Lifestyle may confound the observed associations between glucocorticoid use and adverse events in observational studies.

This large population-based study may guide assessment of the association between lifestyle and glucocorticoid use when data on lifestyle factors are not available.

The response rate to the questionnaire was 67% and it is possible that the respondents had a different health profile than non-respondents. To minimise bias due to non-response, we used a weighting method developed for this particular survey.

Information on lifestyle factors was based on self-reported data, which can be prone to misclassification.

As this study had a cross-sectional design, it was unable to evaluate whether lifestyle predicts glucocorticoid use or vice versa.

Background

Since their introduction in the 1950s, glucocorticoids have been prescribed to treat numerous inflammatory conditions and are widely used with annual prevalence of 3% in Denmark.1 2 However, glucocorticoids also are associated with several adverse events, including truncal obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia,3 cardiac disease,4,7 venous thromboembolism,6 diabetes mellitus,8 psychiatric illnesses9 and osteoporosis.10

Lifestyle factors, including smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and obesity, are well-described risk factors for many adverse events associated with glucocorticoids.11,14 Moreover, prior studies have found that unhealthy lifestyle is abundant in populations with diseases frequently treated with glucocorticoids, for example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, and also associated with severity of disease development.15,21 Thus, lifestyle factors potentially can confound observed associations between glucocorticoid exposure and adverse events. Pharmacosurveillance of glucocorticoids is often performed using observational studies, in which control of such confounders is important. However, many data sources used for surveillance lack data on lifestyle. This has been acknowledged as a limitation in prior studies.6 22

To quantify the amount of potential uncontrolled confounding by lifestyle factors in observational studies of systemic glucocorticoids, we used data from a population-based health survey and conducted a cross-sectional study to examine prevalence of lifestyle factors according to glucocorticoid use.

Methods

Setting

Denmark provides tax-supported health services to all residents with access to primary and secondary care free of charge. A unique central personal registration number is assigned to all Danish residents at birth or immigration, permitting accurate and unambiguous linkage of relevant registries at the individual level.23 Denmark is administratively divided into five regions. We conducted this study in the Central Denmark Region, with a population of 1.2 million inhabitants.

Study population

The study population was identified through responses to the survey, ‘Hvordan har du det?’ (How Are You?), a questionnaire-based public health study conducted by DEFACTUM (formerly Centre for Public Health and Quality Improvement).24 The main incentive of the survey was to map health and health behaviours among citizens in order to promote better health through targeted prevention and intervention by Danish health authorities. Yet, data are available for research also. Between February and May 2010, a random sample of 52 400 people (7026 in the 16–24 year age group and 45 373 in the ≥25 year age group) living in the Central Denmark Region was invited to participate in the study. The current study only included adults (≥25 years of age) who completed the study’s detailed questionnaire (30 245 persons, 67% of those invited). The questionnaire was sent by post and had to be returned by mail in reply enveloped (postage was prepaid). Up to three reminders were sent if people did not answer. The first 1000 people answering the questionnaire were promised two tickets for the cinema. In addition, participants were able to win lottery gifts.

Lifestyle data

Lifestyle-related items included in the questionnaire were body mass index (BMI), participation in regular leisure-time physical activities, diet, smoking status and alcohol intake. BMI was calculated as self-reported weight in kilograms divided by self-reported height in metres, squared. BMI was categorised according to WHO criteria, as underweight (BMI <18.5), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24), overweight (BMI 25–29) and obese (BMI ≥30).25 Questionnaire items on physical activity focused on participation in leisure sports or other regular exercise (yes/no). To assess diet, the health survey used a scoring system developed by the Research Centre for Prevention and Health, Capital Region of Denmark. Thirty different questions were included on intake of fruit, vegetables, fish and fat. The scoring system was used to summarise responses into categories of ‘healthy’ (high amount of fruit, vegetables, fish and low amounts of saturated fat), ‘reasonably healthy’ (median high intake of fruit, vegetables, fish and saturated fat), or ‘unhealthy’ (low amount of fruit, vegetables, and fish, and high amount of saturated fat). Smoking status was categorised as never, former or current (daily or occasional). We categorised alcohol use according to the Danish Health and Medicine Authority's recommendations, that is, high-risk consumption (>7/14 (women/men) drinks weekly) or low-risk consumption (≤7/14 drinks weekly).

Data on medication use

Use of systemic glucocorticoids was identified through the Danish National Health Service Prescription Database (DNHSPD). The DNHSPD contains information on prescriptions reimbursed by the National Health System since 2004.26 Use of systemic glucocorticoids was defined as never use (persons who never redeemed a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid before completing the questionnaire) and ever use of systemic glucocorticoids. Ever use was categorised further according to timing of exposure and cumulative dose expressed in dose of prednisolone equivalents. Timing of exposure was classified as current use (redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid ≤90 days before completing the questionnaire), current new use (first-ever redemption of a prescription ≤90 days before completing the questionnaire), current continuing use (first-ever prescription redemption more than 90 days before completing the questionnaire, but most recent prescription ≤90 days), recent use (redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid 91–365 days before completing the questionnaire) and former use (redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid >365 days before completing the questionnaire). The cumulative dose expressed in prednisolone equivalents was divided in <100 mg, 100–499 mg, 500–999 mg, 1000–1999 mg, 2000–4999 mg and ≥5000 mg. (See online supplementary table 1 for codes used in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system of WHO and online supplementary table 2 for calculation of prednisolone equivalent doses.)

Statistical analyses

First, prevalence of lifestyle factors was computed according to glucocorticoid use.

Second, adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs were estimated using a Poisson regression model. All categories of systemic glucocorticoid use (ever use, current use, current new use, current continuing use, recent use and former use as well as categories of cumulative dose of prednisolone equivalents) were compared with the reference of never use. The prevalence ratios (PRs) were adjusted for age (10 year age groups). All analyses were stratified by sex.

In supplementary analyses, PRs were estimated stratified by age group (25–44, 45–64, ≥65 years of age) and by potential COPD (yes/no). Based on history of medication use, potential COPD was defined as at least two redeemed prescriptions after age 40 (and none before) for a long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA), a long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist (LAMA) or an inhaled corticosteroid (or combinations thereof).

In estimating prevalence and PRs, postsurvey weights computed at Statistic Denmark were used to account for survey design and non-response.27

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata software (Release V.12, StataCorp LP).

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

In total, 30 245 persons completed the study questionnaire (53% women), and median age was 53 years. Of these, 563 (1.9%) were current users of glucocorticoids, 885 (2.9%) were recent users, 3054 (10%) were former users and 25 743 (85%) were never users. The prevalence of demographics and lifestyle factors according to glucocorticoid use is presented in table 1 and in the online supplementary table 3.

Table 1. Prevalence of lifestyle factors according to glucocorticoid use in women and men.

| Ever use | Current use | Recent use | Former use | Never use | Total | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Women | ||||||

| All | 2460 (100) | 301 (100) | 489 (100) | 1670 (100) | 13 485 (100) | 15 945 (100) |

| Median age (range), years | 61 (25–98) | 66 (26–94) | 58 (25–98) | 58 (25–98) | 52 (25–101) | 53 (25–101) |

| Body mass Index | ||||||

| <18.5 | 58 (2.7) | 17 (5.4) | 15 (3.9) | 26 (1.8) | 310 (2.6) | 368 (2.6) |

| 18.5–24 | 1113 (45) | 126 (38) | 218 (44) | 769 (46) | 7203 (54) | 8316 (52) |

| 25–29 | 717 (28) | 89 (31) | 120 (23) | 508 (29) | 3718 (27) | 4435 (27) |

| ≥30 | 444 (18) | 50 (17) | 105 (22) | 289 (17) | 1862 (14) | 2306 (14) |

| Missing | 128 (6.3) | 19 (8.2) | 31 (7.3) | 78 (5.6) | 392 (3.3) | 520 (3.8) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Current | 552 (22) | 66 (20) | 112 (22) | 374 (22) | 2744 (21) | 3296 (21) |

| Former | 765 (30) | 111 (35) | 148 (30) | 506 (29) | 3913 (28) | 4678 (28) |

| Never | 1047 (44) | 107 (40) | 206 (42) | 734 (45) | 6535 (49) | 7582 (48) |

| Missing | 96 (4.2) | 17 (4.6) | 23 (5.3) | 56 (3.9) | 293 (2.4) | 389 (2.7) |

| Diet | ||||||

| Unhealthy | 191 (7.9) | 29 (9.7) | 36 (7.6) | 126 (7.7) | 852 (6.8) | 1043 (7.0) |

| Reasonably healthy | 1425 (58) | 181 (62) | 280 (57) | 964 (57) | 8021 (60) | 9446 (59) |

| Healthy | 730 (29) | 72 (22) | 143 (27) | 515 (31) | 4234 (30) | 4964 (30) |

| Missing | 114 (5.2) | 19 (5.5) | 30 (7.6) | 65 (4.4) | 378 (3.2) | 492 (3.5) |

| Alcohol intake | ||||||

| Low-risk consumption | 1832 (76) | 231 (80) | 376 (77) | 340 (74) | 10 146 (75) | 11 978 (75) |

| High-risk consumption | 458 (17) | 43 (12) | 75 (13) | 1225 (18) | 2730 (20) | 3188 (19) |

| Missing | 170 (7.9) | 27 (8.1) | 38 (9.2) | 105 (7.5) | 609 (4.7) | 779 (5.2) |

| Participation in regular leisure time physical activity | ||||||

| No | 1179 (49) | 171 (59) | 245 (53) | 763 (46) | 5853 (44) | 7032 (45) |

| Yes | 1209 (48) | 121 (39) | 228 (44) | 860 (50) | 7354 (54) | 8563 (53) |

| Missing | 72 (3.2) | 9 (2.3) | 16 (3.2) | 47 (3.3) | 278 (2.3) | 350 (2.4) |

| Men | ||||||

| All | 2042 (100) | 262 (100) | 396 (100) | 1384 (100) | 12 258 (100) | 14 300 (100) |

| Median age (range), years | 61 (25–98) | 65 (28–94) | 57 (25–88) | 59 (25–100) | 53 (25–99) | 54 (25–100) |

| Body mass Index | ||||||

| <18.5 | 21 (1.3) | 6 (4.0) | 6 (1.8) | 9 (5.3) | 40 (0.04) | 61 (0.6) |

| 18.5–24 | 644 (33) | 88 (34) | 128 (34) | 428 (32) | 4572 (39) | 5216 (38) |

| 25–29 | 959 (46) | 116 (41) | 188 (46) | 655 (47) | 5566 (44) | 6525 (44) |

| ≥30 | 365 (17) | 47 (19) | 65 (14) | 253 (18) | 1864 (15) | 2229 (15) |

| Missing | 53 (2.8) | 5 (2.2) | 9 (3.5) | 39 (2.6) | 216 (1.7) | 269 (1.9) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Current | 518 (27) | 64 (27) | 98 (26) | 356 (27) | 3072 (27) | 3590 (27) |

| Former | 843 (38) | 126 (43) | 157 (36) | 560 (38) | 4022 (30) | 4865 (31) |

| Never | 630 (32) | 67 (27) | 132 (35) | 431 (32) | 4968 (42) | 5598 (41) |

| Missing | 51 (2.8) | 5 (2.2) | 9 (3.2) | 37 (2.8) | 196 (1.6) | 247 (1.8) |

| Diet | ||||||

| Unhealthy | 310 (15) | 47 (15) | 63 (15) | 200 (15) | 1906 (16) | 2216 (16) |

| Reasonably healthy | 1301 (64) | 159 (62) | 253 (65) | 889 (64) | 7874 (64) | 9175 (64) |

| Healthy | 342 (15) | 38 (13) | 68 (16) | 236 (15) | 2069 (17) | 2411 (16) |

| Missing | 89 (5.1) | 18 (9.3) | 12 (3.2) | 59 (4.9) | 409 (3.4) | 498 (3.6) |

| Alcohol intake | ||||||

| Low-risk consumption | 1489 (72) | 184 (70) | 293 (73) | 1012 (72) | 9231 (75) | 10 720 (75) |

| High-risk consumption | 443 (22) | 62 (21) | 81 (19) | 300 (22) | 2588 (21) | 3031 (21) |

| Missing | 110 (6.7) | 16 (8.7) | 22 (7.6) | 72 (6.0) | 439 (3.5) | 549 (4.0) |

| Participation in regular leisure time physical activity | ||||||

| No | 1128 (54) | 82 (65) | 214 (52) | 739 (52) | 6265 (50) | 7393 (51) |

| Yes | 874 (44) | 175 (32) | 171 (45) | 621 (46) | 5791 (48) | 6665 (48) |

| Missing | 40 (2.2) | 5 (2.6) | 11 (2.7) | 24 (2.0) | 202 (1.6) | 242 (1.7) |

Percentages are weighted. Never use: Ppersons who never redeemed a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid before completing the questionnaire. Ever use: Aat least one redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid before completing the questionnaire. Current use: Rredemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid ≤90 days before completing the questionnaire. Recent use: Rredemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid 91–365 days before completing the questionnaire. Former use: Rredemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid >365 days before completing the questionnaire.

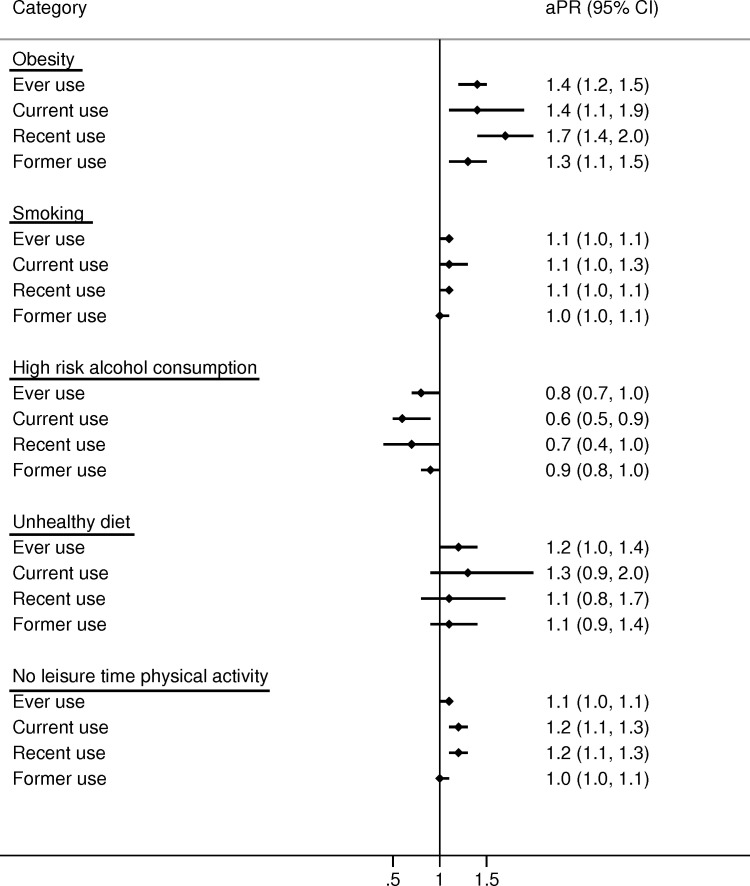

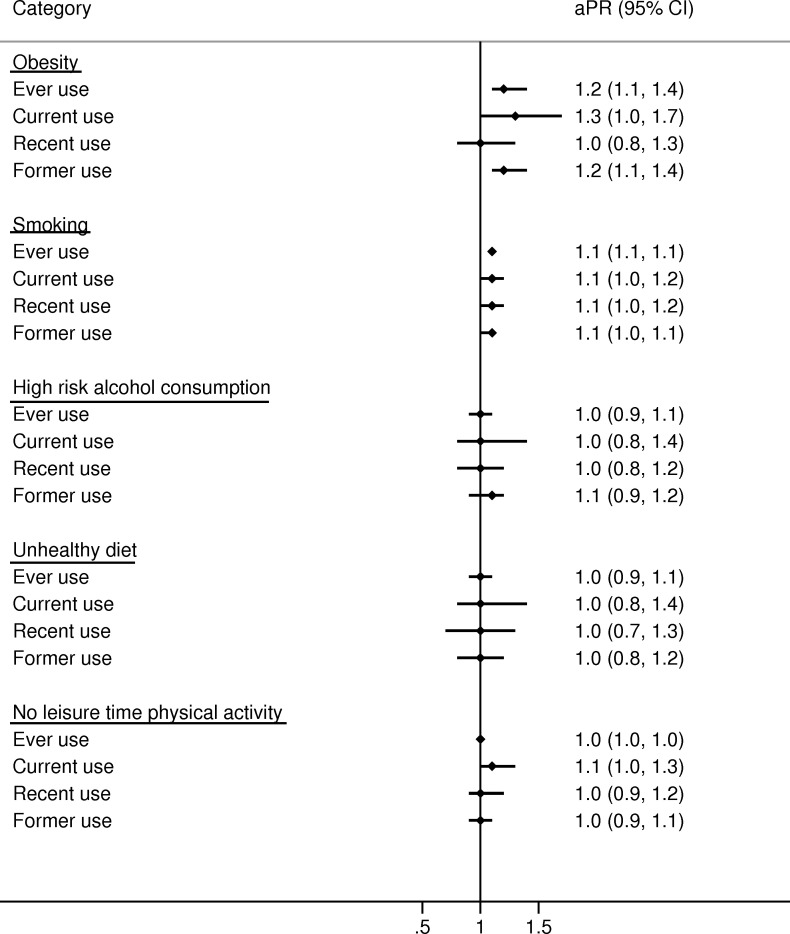

Body mass index

In women, ever users of glucocorticoids were slightly more obese than never users (18% vs 14%; aPR 1.4 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.5); see table 1 and figure 1) with the highest prevalence in current continuing users (21%) and recent users (22%; see table 1, online supplementary table 3 and table 4). Also, male ever users were slightly more obese than never users (17% vs 15%; aPR 1.2 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.4); see table 1 and figure 2). In addition, prevalence of obesity increased with greater cumulative glucocorticoid dose in both sexes (figures3 4).

Figure 1. Age-adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs for lifestyle factors comparing glucocorticoid users to never users in women. Never use: persons who never redeemed a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid before completing the questionnaire. Ever use: at least one redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid before completing the questionnaire. Current use: redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid ≤90 days before completing the questionnaire. Recent use: redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid 91–365 days before completing the questionnaire. Former use: redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid >365 days before completing the questionnaire.

Figure 2. Age-adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs for lifestyle factors comparing glucocorticoid users to never users in men. Never use: persons who never redeemed a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid before completing the questionnaire. Ever use: at least one redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid before completing the questionnaire. Current use: redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid ≤90 days before completing the questionnaire. Recent use: redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid 91–365 days before completing the questionnaire. Former use: redemption of a prescription for a systemic glucocorticoid >365 days before completing the questionnaire.

Figure 3. Age-adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs for lifestyle factors comparing cumulative glucocorticoid dose (in grams of prednisolone equivalents) to never users in women.

Figure 4. Age-adjusted prevalence ratios (aPRs) and 95% CIs for lifestyle factors comparing cumulative glucocorticoid dose (in grams of prednisolone equivalents) to never users in men.

Smoking

Glucocorticoid ever users had a similar prevalence of smoking as never users of glucocorticoids in both women (aPR 1.1 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.1)) and men (aPR 1.1 (95% CI 1.1 to 1.1); figures1 2). These findings were consistent across all categories of glucocorticoid users (figures14) and when stratifying on potential COPD (online supplementary table 5).

Alcohol intake

In women, the prevalence of high-risk alcohol consumption was somewhat lower in ever users of glucocorticoids than never users (17% vs 20%; aPR=0.8 (95% CI 0.7 to 1.0); see table 1 and figure 1). For men, there was no difference (aPR 1.0 (95% CI 0.9 to 1.1); see table 1 and figure 2).

Physical activity

Physical activity did not differ substantially according to use of glucocorticoids in either women (aPR 1.1 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.1)) or men (aPR 1.0 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.0); see figures1 2) although greater cumulative dose of glucocorticoid use was slightly associated with less physical activity (figures3 4).

The PRs did not differ substantially by age group (online supplementary table 6 and online supplementary table 7).

Discussion

This population-based study found that users of systemic glucocorticoids had a slightly higher prevalence of obesity than never users. In women, the prevalence of obesity was 1.4-fold higher and in men 1.2-fold higher. In women, the prevalence of high-risk alcohol consumption was 0.8-fold lower in users of glucocorticoids than never users. This finding did not apply for men. Smoking habits, diet and physical activity did not differ substantially according to use of systemic glucocorticoids.

Data on lifestyle among glucocorticoid users are sparse, although truncal obesity is a well-known feature of glucocorticoid excess.3 28 In addition, one study reported higher prevalence of glucocorticoid use in obese versus non-obese people29 and one study found that overweight and obesity were risk factors of self-reported arthritis.19 In contrast, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was lower in people with inflammatory bowel disease than healthy controls.20 While arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease are potential indications for glucocorticoid treatment, these populations do not compare directly to our study population. Due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we were not able to investigate if glucocorticoid use predicted obesity or vice versa and the study did not aim to investigate adverse effects of glucocorticoids. Nevertheless, we found higher prevalence of obesity in current continuing users of glucocorticoids compared with current new users and increasing prevalence of obesity with increasing cumulative glucocorticoid dose. These results may indicate that glucocorticoid use precedes obesity. Physical activity has been reported to be low in some patient groups ordinarily treated with glucocorticoids; one study found that more than 60% of adults with arthritis do not comply with physical activity recommendations.21 The reasons why the majority of persons with arthritis did not meet physical activity recommendations were not investigated, but authors discussed if it may be related to arthritis-specific barriers to physical activity such as fear of making their arthritis worse, fatigue or pain.21 In our study, we found no major difference in physical activity according to glucocorticoid use, although greater cumulative dose of glucocorticoid was slightly associated with less physical activity.

While we conducted a large population-based cohort study with detailed information on lifestyle factors, its limitations must be considered. First, the response rate to the questionnaire was 67%. We cannot be sure if persons who completed the health survey had a different health profile than those who declined. To minimise such bias, we used a weighting method developed by Statistic Denmark for this particular survey.27 Second, persons who completed the questionnaire might have answered incorrectly. Third, redeemed prescriptions may be an imperfect measure of actual drug intake and its timing. Also, the prescription database only covers prescriptions from 2004 on, which may have led to misclassification of glucocorticoid use. We were not able to predict direction of bias due to potential misclassification of glucocorticoid use or lifestyle factors. Fourth, we did not stratify on socioeconomic status and were not able to identify treatment indication. The algorithm used to define people as having potential COPD may be imperfect. In particular, certain persons identified as having COPD actually have asthma. To address this issue, redeemed prescriptions for LABA or LAMA before age 40 were an exclusion criterion, as asthma onset most often occurs in childhood or adolescence, whereas COPD onset is later in life. Last, as this study had a cross-sectional design, it was unable to evaluate whether lifestyle predicts glucocorticoid use or vice versa. Still, the study did not aim or was designed to evaluate adverse effects of glucocorticoids.

Our study has important implications for quantifying the amount of potential uncontrolled confounding by lifestyle factors in observational studies of systemic glucocorticoids. Results from this study may guide assessment of the association between lifestyle and glucocorticoid use and can, for example, be used in a bias analysis when data on lifestyle factors are not available.6 7 30 Yet, it must be acknowledged that any assessment should not be based solely on associations found in this study. Directed acyclic graphs could be applied to ensure that recorded lifestyle factors are not mediators or colliders.31

In conclusion, glucocorticoid users had a slightly higher prevalence of obesity and female glucocorticoid users had a slightly lower prevalence of high-risk alcohol consumption compared with never users. Smoking habits, diet and physical activity did not differ substantially according to use of glucocorticoids. Our study provides a framework for quantifying potential uncontrolled confounding by lifestyle factors in studies of systemic glucocorticoids.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by Department of Clinical Epidemiology. Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University Hospital, receives funding for other studies from companies in the form of research grants to (and administered by) Aarhus University. None of these studies have any relation to the present study.

prepub: Prepublication history and additional material for this paper are available online. To view please visit the journal (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030780).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Record number: 2016-051-000001, serial number 448). For this type of study, approval from ethics committee and formal consent is not required.

Contributor Information

Kristina Laugesen, Email: kristina.laugesen@clin.au.dk.

Irene Petersen, Email: i.petersen@ucl.ac.uk.

Lars Pedersen, Email: lap@clin.au.dk.

Finn Breinholt Larsen, Email: finn.breinholt@stab.rm.dk.

Jens Otto Lunde Jørgensen, Email: joj@clin.au.dk.

Henrik Toft Sørensen, Email: hts@clin.au.dk.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Laugesen K, Jørgensen JOL, Sørensen HT, et al. Systemic glucocorticoid use in Denmark: a population-based prevalence study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015237–2016. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laugesen K, Jørgensen JOL, Petersen I, et al. Fifteen-year nationwide trends in systemic glucocorticoid drug use in Denmark. Eur J Endocrinol. 2019;181:267–73. doi: 10.1530/EJE-19-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pivonello R, De Martino MC, Iacuaniello D, et al. Metabolic alterations and cardiovascular outcomes of cortisol excess. Frontiers of hormone research. 2016;46:54–65. doi: 10.1159/000443864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis JM, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, et al. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:820–30. doi: 10.1002/art.22418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fardet L, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Risk of cardiovascular events in people prescribed glucocorticoids with iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome: cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johannesdottir SA, Horvath-Puho E, Dekkers OM, et al. Use of glucocorticoids and risk of venous thromboembolism: a nationwide population-based case-control study. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173:743–52. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei L, MacDonald TM, Walker BR. Taking glucocorticoids by prescription is associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:764–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clore J, Thurby-Hay L. Glucocorticoid-Induced hyperglycemia. Endocrine Practice. 2009;15:469–74. doi: 10.4158/EP08331.RAR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fardet L, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Suicidal behavior and severe neuropsychiatric disorders following glucocorticoid therapy in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169:491–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Staa TP, Leufkens HGM, Cooper C, et al. The epidemiology of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:777–87. doi: 10.1007/s001980200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson JJB, Rondano P, Holmes A. Roles of diet and physical activity in the prevention of osteoporosis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25:65–74. doi: 10.3109/03009749609103752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, et al. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1983;67:968–77. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, et al. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham heart study. Jama. 1994;271:840–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:790–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:269–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lunney PC, Kariyawasam VC, Wang RR, et al. Smoking prevalence and its influence on disease course and surgery in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:61–70. doi: 10.1111/apt.13239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radner H, Lesperance T, Accortt NA, et al. Incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2016 doi: 10.1002/acr.23171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:70–81. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehrotra C, Naimi TS, Serdula M, et al. Arthritis, body mass index, and professional advice to lose weight: implications for clinical medicine and public health. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nic Suibhne T, Raftery TC, McMahon O, et al. High prevalence of overweight and obesity in adults with Crohn's disease: associations with disease and lifestyle factors. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2013;7:e241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fontaine KR, Heo M, Bathon J. Are us adults with arthritis meeting public health recommendations for physical activity? Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;50:624–8. doi: 10.1002/art.20057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Mehnert F, et al. Glucocorticoid use and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: a population-based, case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1677–83. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:541–9. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen FB, Ankersen PV, Poulsen S. Hvordan har du det? 2010 – Sundhedsprofil for region og kommuner [How Are you? 2010– Health profile for region and municipalities]. Report. Vol. 25. Denmark: Region Midtjylland; 2011. p. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johannesdottir SA, Horváth-Puhó E, Ehrenstein V, et al. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish national database of Reimbursed prescriptions. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:303–13. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fangel S, Linde PC, Thorsted BL. Nye problemer med reprasentativitet i surveys, som opregning med registre kan reducere. Metode & Data. Nye problemer med reprasentativitet i surveys, som opregning med registre kan reducere. Metode & Data. 2007;14 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barahona M-J, Sucunza N, Resmini E, et al. Persistent body fat mass and inflammatory marker increases after long-term cure of Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3365–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savas M, Wester VL, Staufenbiel SM, et al. Systematic evaluation of corticosteroid use in obese and non-obese individuals: a multi-cohort study. Int J Med Sci. 2017;14:615–21. doi: 10.7150/ijms.19213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern epidemiology. 3th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkens; 2008. Modern Epidemiology; pp. 345–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]