Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate seroprevalence against Bordetella pertussis in Tuscany, a large Italian region, from 1992 to 2005 and from 2013 to 2016.

Design

Seroepidemiological study.

Participants

1812 serum samples collected in Tuscany from subjects older than 12 years from 1992 to 2005 and from 2013 to 2016.

Outcome measures

Specific antibody levels were determined by means of standard commercial ELISA using a dual cut-off of 50 and 125 IU/mL as markers of past and recent infection/vaccination, respectively.

Results

The highest values of IgG titres were observed in 1992–1994 in all subjects (69.5 IU/mL), with prevalence values of subjects with IgG titres of >50 and >125 IU/mL of 68.3% and 23.8%, respectively. IgG titres decreased in the years thereafter (37.8 IU/mL in 2002–2005), together with prevalence values (41.7% and 8.1% in 2002–2005). In 2013–2016, both IgG titres and prevalence values showed a slight increase (50.6 IU/mL, 53.9% and 14.7%, respectively). IgG titres and prevalence followed the same age-related trend in all time periods considered, with the highest values in subjects aged 12–22 years. The lowest values were found in the age group of subjects aged 23–35 years (OR 0.54).

Conclusions

Since 2002, approximately half of the population over 22 years of age have low IgG titres and are presumably susceptible to acquiring and transmitting pertussis infection. In addition, in 2013–2016, almost one-third of subjects aged 12–22 years, that is, the age group most likely to have been vaccinated against pertussis in infancy, had low antibody levels. Improving vaccination coverage and implementing careful surveillance are therefore recommended in order to prevent morbidity and mortality due to pertussis.

Keywords: pertussis, epidemiology, Italy, Tuscany

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides data on levels of specific antibodies against pertussis in a large, population-based selection of serum samples from Tuscany, Central Italy.

This study considers a period of over two decades, based on the introduction of pertussis vaccination in infants in the Tuscany region, as well as in Italy, after 1995.

Antibody titres and prevalence values were calculated over time and by age group, providing an evidence of susceptibility to pertussis in Italian adolescents and adults.

The main limitation is that samples between 2006 and 2012 were not available.

Only information on sex and age was available for each sample, and no extensive statistical analysis could be performed on other sociodemographic variables.

Introduction

Pertussis is a highly infectious respiratory disease caused by Bordetella pertussis.1 The disease affects all age groups; however, if contracted in the first 2 years of life, the course of the disease can be particularly severe, with a high incidence of complications and mortality.1 2 Despite the introduction of large-scale vaccination programmes for infants and children, pertussis is still one of the most serious vaccine-preventable diseases, even in countries with high vaccination coverage.1 Over recent decades, several reports have highlighted a resurgence of pertussis in older children, adolescents and adults.3–5

In Italy, a whole-cell pertussis (wP) vaccine became available in 1961 and was recommended for the immunisation of infants.6 However, pertussis vaccination coverage remained low (less than 40%), with large regional differences.7 In 1995, the wP vaccine was replaced by an acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine; this was incorporated into the diphtheria–tetanus–acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine, the administration of which was recommended in three doses at 3, 5 and 11 months of age. In 1999, a booster dose at the age of 6 years (school entry) was introduced into the national childhood immunisation plan, together with further booster doses in adolescents (12–14 years) from 2003 onwards.8 9 Vaccination coverage in children up to 24 months of age increased progressively after the introduction of the aP vaccine, with 88% of children aged 12–24 months having received three doses of DTaP vaccine in 1998.10 After 2002, vaccination coverage increased further, reaching 96.6% in 200811 12 probably as a result of the free-of-charge provision of vaccines at the national level. However, vaccination coverage among children aged 6 years (fourth dose of DTaP vaccine) was 26.7% and that among adolescents (fifth dose) was only 14.1% in 2008.12 Over the following years, the national vaccination coverage for the three doses in children aged 12–24 months decreased to 93.55%, as reported in 2016.13

In the Tuscany region, pertussis vaccination coverage displayed a similar trend to that seen at the national level. In 2008, the vaccination coverage for the third dose in children aged 24 months was 94.8%, while it was 44.8% for both the fourth and fifth doses, a higher figure than the national average.12 In 2016, vaccination coverage was 94.4% in children aged 12–24 months and 78.4% in 16-year-old subjects.13

The epidemiology of pertussis in Italy has changed over the years since the implementation of pertussis vaccination. After the introduction of the wP vaccine in 1961, the incidence of pertussis declined slightly. However, a steady decrease was observed only after the high coverage rates were reached with aP-containing vaccines: from approximately 7000 cases reported in 1998 to 339 in 2008. Subsequently, however, the incidence rose to 670 cases in 2014.2 14 In 2016, 965 cases were reported, and in 2017, 964 cases were reported, 919 of which were confirmed.14 In the Tuscany region, the trend in reported cases was similar to the national data, with a decrease from 355 cases in 1998 to 31 in 2008. In 2016 and 2017, 83 and 117 cases, respectively, were reported.15 National routine notification data indicate that Italy has a low incidence of pertussis. Although notification is mandatory,16 the number of reported pertussis cases is greatly underestimated.8 11 In immunised children, adolescents and adults, the disease may have a mild course and is not usually diagnosed.17 These subjects constitute a major reservoir of infection for children who are not yet fully immunised. Indeed, several epidemiological surveys have suggested that the incidence of pertussis infection is high in this age group,2 18 19 as reported by hospitalisation data collected in the Tuscany region.9 20

The spread of the infection can be prevented by achieving herd immunity through high vaccination coverage in the population. Several studies have reported that immunity against pertussis, whether natural or acquired through vaccination, wanes after 4–12 years21 or more. In highly immunised populations, the reduced circulation of B. pertussis decreases natural boosting, and epidemic outbreaks are observed mainly in older adolescents and adults.2 21 22 In these circumstances, information on the serological status of the population may provide a critical contribution to the implementation of pertussis vaccination strategies and policies.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of antibodies against B. pertussis as a marker of vaccination or natural exposure in samples collected in Tuscany, a large Italian region, between 1992 and 2005 and between 2013 and 2016.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Samples were anonymously collected as residual samples for unknown diagnostic purposes and were stored in compliance with Italian ethics law. The only information available for each serum sample was age, sex and date of sampling. Patients and/or the public were not involved.

Human serum samples were available from the Serum Bank of the Laboratory of Molecular Epidemiology, Department of Molecular and Developmental Medicine, University of Siena, Siena Italy. Sample size per group was calculated by means of Cochran’s sample size formula. The desired level of precision was set at 10%, and frequencies of 15% and 60% were assumed. These calculations yielded 49 and 93 subjects per group for 15% and 60% frequency, respectively. Out of a total of 10 200 serum samples collected in the area of Siena from 1992 to 2005 and from 2013 to 2016, a total of 1812 were randomly selected. Randomisation was performed in a stratified fashion; the main selection criterion was that the numbers be balanced in terms of sex, age and time interval according to the availability of sera during each particular time period. Selection of the time periods was based on two main criteria: the availability of serum samples collected from the age group of interest during a given period and the introduction of pertussis vaccination in infants in the Tuscany region, as well as in Italy, after 1995. Samples were not available between 2006 and 2012.

Samples were tested for IgG antibodies against B. pertussis by means of the ‘SERION ELISA classic Bordetella pertussis IgG’ (Virion\Serion, Germany) commercial kit, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. According to the manufacturer, this immunoassay uses both pertussis toxin (PT) and filamentous haemagglutinin (FHA) as antigens and has a sensitivity and a specificity of >99%. As indicated in the instructions, the cut-off level for positivity was 50 IU/mL. In addition, samples with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL were considered suggestive of recent infection or exposure to the vaccine, that is, within the past year.23 24

Table 1 lists the selected samples by period of collection and age group.

Table 1.

Serum samples collected in Siena by period and age group

| Sample period | Age groups (years) | Total | |||

| 12–22 | 23–35 | 36–50 | >50 | ||

| 1992–1994 | 64 | 80 | 90 | 56 | 290 |

| 1995–1998 | 86 | 103 | 125 | 72 | 386 |

| 1999–2001 | 64 | 77 | 92 | 58 | 291 |

| 2002–2005 | 74 | 104 | 114 | 89 | 381 |

| 2013–2016 | 68 | 131 | 148 | 117 | 464 |

All statistical analyses were performed by means of Microsoft R-Open V.3.5.0 (https://www.R-project.org/). Figures were prepared by means of the ggplot2 package in Microsoft R-open. Age-specific geometric mean titres (GMTs) and proportions above cut-off rates were calculated for each time period, along with the corresponding 95% CIs. The effects of age group and sampling period were evaluated by two-way analysis of variance for GMTs and logistic regression for IgG titres of >50 and >125 IU/mL proportions. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. The best-fitting model was selected on the basis of the lowest Akaike information criterion.

Results

A total of 1812 serum samples were tested (table 1); samples with IgG titres of >50 IU/mL were considered positive, and those with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL were deemed indicative of exposure to pertussis infection or vaccination in the past year.23 24 Analysis by sex showed no effect.

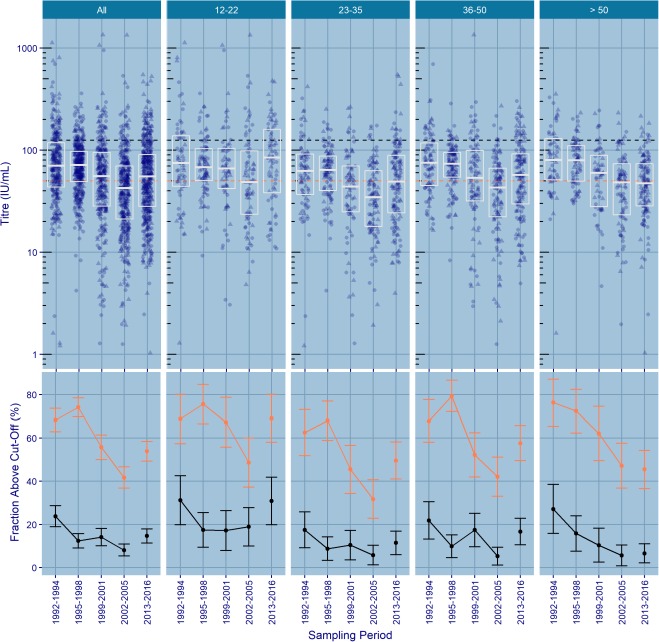

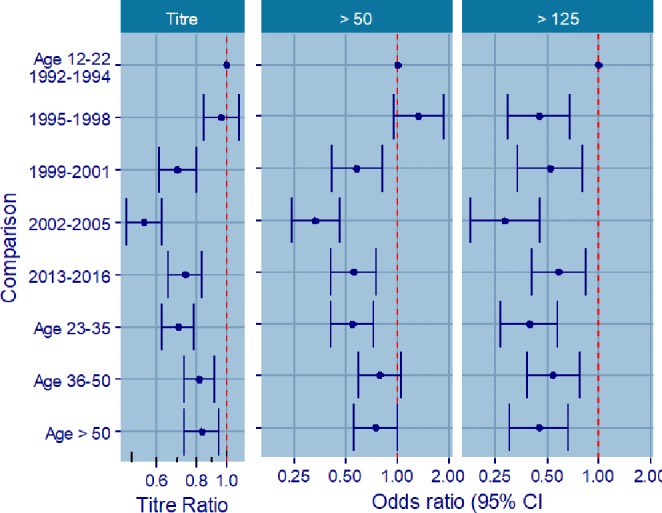

Figure 1 shows IgG titres (GMTs and proportions above cut-off rates) over time and by age group; estimates and logistic regression analyses are shown in figure 2.

Figure 1.

Top panel: pertussis IgG titres by sampling period and age group. Individual titres are plotted per sampling period (circles indicate female and triangles indicate male). Boxes indicate median and quartile ranges; orange and black dashed lines indicate antibody levels at 50 and at 125 IU/mL, respectively. Bottom panel: percentages of subjects with IgG titres of >50 IU/mL (orange) and >125 IU/mL (black) by sampling period and age group.

Figure 2.

Estimates from analysis of variance and logistic regression analyses, all comparisons versus index, that is, age 12–22 in 1992–1994.

Time trends in pertussis IgG titres

The highest IgG GMTs were observed in 1992–1994 (69.5 IU/mL, 95% CI 62.7 to 77.0) and in 1995–1998 (67.1 IU/mL, 95% CI 63.3 to 71.2). Titres decreased to 48.8 IU/mL (95% CI 43.3 to 54.9) in 1999–2001 and even further to 37.8 IU/mL (95% CI 34.3 to 41.6) in 2002–2005, but rose slightly to 50.6 IU/mL (95% CI 46.6 to 54.9) in 2013–2016. The time trend in IgG GMTs was similar across all age groups, with the exception of the >50-year-old age group, in which no increase was observed in 2013–2016. The change in IgG GMTs over time was also reflected in the proportion of IgG titres of >50 and >125 IU/mL.

The highest proportion of subjects with IgG titres of >50 IU/mL was found in 1992–1994 (68.3%, 95% CI 62.9 to 73.6) and in 1995–1998 (74.1%, 95% CI 69.7 to 78.5). From 1999 onwards, the proportion of titres above 50 IU/mL decreased in comparison with 1992–1994, with ORs of 0.58 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.81) and 0.33 (95% CI 0.24 to 0.46) for 1999–2001 (55.7%, 95% CI 50.0 to 61.4) and 2002–2005 (41.7%, 36.8 to 46.7), respectively. The proportion of subjects with titres over 50 IU/mL showed a slight increase in 2013–2016 (53.9%, 95% CI 49.3 to 58.4; OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.75).

The highest proportion of subjects with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL was found in 1992–1994 (23.8%, 95% CI 18.9 to 28.7), particularly among subjects in the age group of subjects aged 12–22 years (31.2%, 95% CI 19.9 to 42.6). In 1995–1998, a substantial decrease in the proportion of subjects with IgG levels of >125 IU/mL was observed (12.4%, 95% CI 9.1 to 15.7; OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.67), and the trend was still characterised by a high proportion of IgG titres of >125 IU/mL in subjects aged 12–22 years (17.4%, 95% CI 9.4 to 25.5). Up to 2005, the proportion of subjects with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL decreased in the overall population (14.1% in 1999–2001, 95% CI 10.1 to 18.1; OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.79; and 8.1% in 2002–2005, 95% CI 5.4 to 10.9; OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.45) and in all age groups except in the age group of subjects aged 12–22 years, in which it remained similar to those of the 1995–1998 period.

In 2013–2016, the proportion of subjects with titres of >125 IU/mL increased slightly in comparison with 2002–2005 (14.7%, 95% CI 11.4 to 17.9; OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.85). This increase was observed in the overall population and in all age groups with the exception of those older than 50 years of age. The highest increase was observed in subjects aged 12–22 years (30.9% in 2013–2016, 95% CI 19.9 to 41.9).

Age trends in pertussis IgG titres

IgG GMTs were lowest in the age group of subjects aged 23–35 years. Both IgG GMTs and the proportions of subjects with IgG levels of >50 IU/mL followed the same age-related trend in all time periods considered, with the highest values in subjects aged 12–22 years. The lowest proportion of subjects with IgG titres of >50 IU/mL was found in the age group of subjects aged 23–35 years (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.72). The proportion of subjects with titres of >50 IU/mL showed an increase in subjects aged 36–50 years and those over 50 years old (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.04 and OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.01, respectively). Only in 2013–2016 did subjects over 50 years display the lowest IgG proportion, with 54.7% (95% CI 45.7 to 63.7) having IgG levels of <50 IU/mL.

The trend was quite similar among subjects with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL; the highest proportion was found in subjects aged 12–22 years. The lowest proportion was again found in those aged 23–35 years (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.57); an increase was observed in the age group of subjects aged 36–50 years (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.76) and a slight decrease in subjects over 50 years old (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.66).

Discussion

In this study, we found that in recent years (2013–2016), more than 40% of subjects aged over 12 years had low IgG titres against pertussis, although with some differences among age groups. Specifically, the highest titres were observed in those aged 12–22 years. Although the commercial kit used to measure IgG does not discriminate between antibodies generated after natural exposure and those generated after vaccination, this age group benefits from high vaccination coverage in infancy (>90%) and booster doses given during adolescence. As subjects in this age group were born between 1991 and 2004, it could be hypothesised that they were the only vaccinated subjects considered in this study and that a small proportion had received the preadolescence booster dose. Pertussis vaccination coverage in adolescents increased significantly in Tuscany from 44.8% in 2008, both for the fourth and fifth doses,12 to 78.4% in 2016.13 In our study, we found that, during the period 1992–1994, which is considered a prevaccination era for pertussis in Italy because of the very low wP vaccine uptake,7 B. pertussis circulated widely in all age groups, with the highest proportion of subjects with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL being observed in preadolescents and adolescents (12–22 years old). In 1995–1998, when aP vaccines became available in Italy and vaccination coverage in infants increased steadily in Tuscany and Italy,8–10 we observed a substantial decrease in the proportion of subjects with IgG levels of >125 IU/mL (−11% from 1992 to 1994), suggesting a reduction in exposure to B. pertussis in all age groups included in this study. However, the trend was still characterised by a high proportion of IgG titres of >125 IU/mL in subjects aged 12–22 years (17%), as in the previous time period. In the following years, up to 2005, the proportion of subjects with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL decreased in the overall population and in all age groups except the 12–22 year-old group, in which it remained similar to that in the 1995–1998 period. The proportion of subjects with IgG titres of >125 IU/mL increased again in 2013–2016 in all age groups with the exception of those over 50 years of age. Specifically, the highest increase was observed in subjects aged 12–22 years, with values close to those of the prevaccination era. This could be interpreted as the result of high vaccination coverage in infants since the past 20 years and in children and adolescents in more recent years. However, variations in IgG titres could correlate not only with the immune status of the population but also with the number of cases of pertussis infection. Indeed, a recent study on pertussis seroprevalence in five Italian regions16 reported that, in serum samples collected in Tuscany, 5% of the general population and 7.1% of subjects aged 20–29 years had antibody titres compatible with a recent infection (PT-IgG level >100 IU/mL), indicating an increase in the circulation of B. pertussis in adults in Italy.

Susceptibility to pertussis in a highly vaccinated population, such as that of the present study, is a complex issue. The overall temporal trend showed a reduction in exposure after the introduction of aP vaccines, followed by a resurgence in the number of positive subjects in 2013–2016; this is consistent with a waning of protection 5–10 years after the administration of the last aP vaccine dose.22 25 26 The resulting lower immunity leads to increased B. pertussis circulation in the overall population, including pregnant women,27 with a serious impact on the most vulnerable subjects, such as neonates, as recently reported in the Tuscany region,9 20 where a dramatic increase in hospital admissions and deaths due to pertussis in infants was reported.

The history of pertussis immunisation (low coverage with wP vaccine, followed by a switch to the aP vaccines and a substantial increase in vaccination coverage) makes Italy an interesting example of the impact of aP vaccines. There is no established correlate of protection for pertussis28; however, a ‘positive’ or ‘detectable’ diagnostic test is considered consistent with some measure of protection.29 In this study, the cut-off recommended by the kit manufacturer was used as a threshold antibody value to define susceptibility, exposure and recent exposure to pertussis or vaccination. Data on the proportion of subjects susceptible to pertussis in a given age group could be very informative and may be used to monitor or plan vaccination policies to prevent resurgence of the disease. The present study illustrates the situation in Italy, but it would be interesting to investigate other European countries where different vaccination policies have been adopted.

This study has some limitations, as samples between 2006 and 2012 were not available, making interpretation of the temporal trend more difficult. In addition, the results may not be fully applicable to the entire Tuscany population, as only two variables were available for each sample (sex and age), and no extensive statistical analysis could be performed to compare these sociodemographic variables with those of the whole Tuscan or Italian population. Moreover, the vaccination status of the subjects was not known. Another potential limitation of this study is that an ELISA against both PT and FHA antigens was used for the assessment of antibody response. Indeed, according to European Union recommendations, the diagnosis of pertussis infection is based on the measurement of PT-specific antibodies alone,30 31 as the FHA antigen is shared with other Bordetella spp; however, the low specificity of the ELISA may ultimately lead to an underestimation of the proportion of susceptible subjects, leaving the conclusions of this study unchanged.

In conclusion, our study revealed that, since 2002, at least 50% of subjects over 22 years of age, and therefore least likely to have been vaccinated against pertussis, have low IgG titres (<50 IU/mL); they are presumably more susceptible to acquiring pertussis and transmitting the disease to the most vulnerable and susceptible individuals, such as newborns and infants. In Tuscany, as in the rest of Italy, only aP vaccines are used. Careful disease surveillance and the maintenance of high vaccination coverage are therefore recommended in order to prevent morbidity and mortality due to pertussis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

GTMS and AA contributed equally.

Contributors: EM, CMT and SV conceived and designed the research study. SM, GTMS and AA performed the experiments. EJR performed the statistical analysis. SM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CMT, EJR and SV revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of the University of Siena, Siena, Italy, deemed that a review of the research study was not required, given that serum samples were not derived from a clinical study and that they were stored and would be tested in a completely and irreversibly anonymous way.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. WHO Pertussis vaccines: WHO position paper - September 2015. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2015;90:433–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gabutti G, Rota MC. Pertussis: a review of disease epidemiology worldwide and in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:4626–38. 10.3390/ijerph9124626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chiappini E, Stival A, Galli L, et al. Pertussis re-emergence in the post-vaccination era. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:151 10.1186/1471-2334-13-151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan T, Dalby T, Forsyth K, et al. Pertussis across the globe: recent epidemiologic trends from 2000 to 2013. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:e222–32. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zepp F, Heininger U, Mertsola J, et al. Rationale for pertussis booster vaccination throughout life in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:557–70. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70007-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Binkin NJ, Salmaso S, Tozzi AE, et al. Epidemiology of pertussis in a developed country with low vaccination coverage: the Italian experience. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11:653–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO Childhood vaccination coverage in Italy: results of a seven-region survey. The Italian vaccine coverage survey Working group. Bull World Health Organ 1994;72:885–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gonfiantini MV, Carloni E, Gesualdo F, et al. Epidemiology of pertussis in Italy: disease trends over the last century. Euro Surveill 2014;19 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.40.20921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berti E, Chiappini E, Orlandini E, et al. Pertussis is still common in a highly vaccinated infant population. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:846–9. 10.1111/apa.12655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salmaso S, Rota MC, Ciofi Degli Atti ML, et al. Infant immunization coverage in Italy: estimates by simultaneous EPI cluster surveys of regions. ICONA Study Group. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77:843–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rota MC, D'Ancona F, Massari M, et al. How increased pertussis vaccination coverage is changing the epidemiology of pertussis in Italy. Vaccine 2005;23:5299–305. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. ICONA ICONA 2008: Indagine di COpertura vaccinale NAzionale nei bambini e negli adolescenti, 2009: 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministero della Salute Vaccinazioni dell’et pediatrica e dell’adolescente – coperture vaccinali [Childhood and adolescent vaccination- Vaccine coverage]. Available: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/documentazione/p6_2_8_3_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=20 [Accessed 6 Nov 2017].

- 14. ECDC Pertussis - Annual Epidemiological Report 2017, 2017: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toscana ARS. La sorveglianza epidemiologica delle malattie infettive in Toscana, Rapporto Ottobre 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palazzo R, Carollo M, Fedele G, et al. Evidence of increased circulation of Bordetella pertussis in the Italian adult population from seroprevalence data (2012-2013). J Med Microbiol 2016;65:649–57. 10.1099/jmm.0.000264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yaari E, Yafe-Zimerman Y, Schwartz SB, et al. Clinical manifestations of Bordetella pertussis infection in immunized children and young adults. Chest 1999;115:1254–8. 10.1378/chest.115.5.1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cherry JD. Immunity to pertussis. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:1278–9. 10.1086/514350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Greeff SC, de Melker HE, van Gageldonk PGM, et al. Seroprevalence of pertussis in the Netherlands: evidence for increased circulation of Bordetella pertussis. PLoS One 2010;5:e14183 10.1371/journal.pone.0014183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiappini E, Berti E, Sollai S, et al. Dramatic pertussis resurgence in Tuscan infants in 2014. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016;35:930–1. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wendelboe AM, Van Rie A, Salmaso S, et al. Duration of immunity against pertussis after natural infection or vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005;24:S58–61. 10.1097/01.inf.0000160914.59160.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klein NP, Bartlett J, Rowhani-Rahbar A, et al. Waning protection after fifth dose of acellular pertussis vaccine in children. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1012–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1200850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ECDC Guidance and protocol for the serological diagnosis of human infection with Bordetella pertussis, 2012: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giammanco A, Chiarini A, Maple PAC, et al. European Sero-Epidemiology Network: standardisation of the assay results for pertussis. Vaccine 2003;22): :112–20. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00514-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Misegades LK, Winter K, Harriman K, et al. Association of childhood pertussis with receipt of 5 doses of pertussis vaccine by time since last vaccine dose, California, 2010. JAMA 2012;308:2126–32. 10.1001/jama.2012.14939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gustafsson L, Hessel L, Storsaeter J, et al. Long-term follow-up of Swedish children vaccinated with acellular pertussis vaccines at 3, 5, and 12 months of age indicates the need for a booster dose at 5 to 7 years of age. Pediatrics 2006;118:978–84. 10.1542/peds.2005-2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marchi S, Viviani S, Montomoli E, et al. Low prevalence of antibodies against pertussis in pregnant women in Italy. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19): :690 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30269-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Plotkin SA. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2010;17:1055–65. 10.1128/CVI.00131-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gall SA, Myers J, Pichichero M. Maternal immunization with tetanus–diphtheria–pertussis vaccine: effect on maternal and neonatal serum antibody levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:334.e1–334.e5. 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guiso N, Berbers G, Fry NK, et al. What to do and what not to do in serological diagnosis of pertussis: recommendations from EU reference laboratories. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2011;30:307–12. 10.1007/s10096-010-1104-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fedele G, Leone P, Bellino S, et al. Diagnostic performance of commercial serological assays measuring Bordetella pertussis IgG antibodies. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;90:157–62. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.