Abstract

Objectives

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is not recommended in major knee osteoarthritis (KOA) treatment guidelines. We investigated whether a LLLT dose–response relationship exists in KOA.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Eligible articles were identified through PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Physiotherapy Evidence Database and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on 18 February 2019, reference lists, a book, citations and experts in the field.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

We solely included randomised placebo-controlled trials involving participants with KOA according to the American College of Rheumatology and/or Kellgren/Lawrence criteria, in which LLLT was applied to participants’ knee(s). There were no language restrictions.

Data extraction and synthesis

The included trials were synthesised with random effects meta-analyses and subgrouped by dose using the World Association for Laser Therapy treatment recommendations. Cochrane’s risk-of-bias tool was used.

Results

22 trials (n=1063) were meta-analysed. Risk of bias was insignificant. Overall, pain was significantly reduced by LLLT compared with placebo at the end of therapy (14.23 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 95% CI 7.31 to 21.14)) and during follow-ups 1–12 weeks later (15.92 mm VAS (95% CI 6.47 to 25.37)). The subgroup analysis revealed that pain was significantly reduced by the recommended LLLT doses compared with placebo at the end of therapy (18.71 mm (95% CI 9.42 to 27.99)) and during follow-ups 2–12 weeks after the end of therapy (23.23 mm VAS (95% CI 10.60 to 35.86)). The pain reduction from the recommended LLLT doses peaked during follow-ups 2–4 weeks after the end of therapy (31.87 mm VAS significantly beyond placebo (95% CI 18.18 to 45.56)). Disability was also statistically significantly reduced by LLLT. No adverse events were reported.

Conclusion

LLLT reduces pain and disability in KOA at 4–8 J with 785–860 nm wavelength and at 1–3 J with 904 nm wavelength per treatment spot.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42016035587.

Keywords: phototherapy, laser therapy, knee osteoarthritis, systematic review, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The review was conducted in conformance with a detailed a priori published protocol, which included, for example, laser dose subgroup criteria.

No language restrictions were applied; four (18%) of the included trials were reported in non-English language.

A series of meta-analyses were conducted to estimate the effect of low-level laser therapy on pain over time.

Three persons each independently extracted the outcome data from the included trial articles to ensure high reproducibility of the meta-analyses.

The review lacks quality-of-life analyses, a detailed disability time-effect analysis and direct comparisons between low-level laser therapy and other interventions.

Introduction

Approximately 13% of women and 10% of men in the population aged ≥60 years suffer from knee osteoarthritis (KOA) in the USA.1 KOA is a degenerative inflammatory disease affecting the entire joint and is characterised by progressive loss of cartilage and associated with pain, disability and reduced quality of life (QoL).1 Increased inflammatory activity is associated with higher pain intensity and more rapid KOA disease progression.1 2

Some of the conservative intervention options for KOA are exercise therapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and anti-inflammatory low-level laser therapy (LLLT). There is evidence that exercise therapy reduces pain and disability and improves QoL in persons with KOA.3 4 NSAIDs are recommended in most KOA clinical treatment guidelines and is probably the most frequently prescribed therapy category for osteoarthritis, despite intake of these drugs is associated with negative side effects,5 which is problematic, especially since the disease requires long-term treatment. Furthermore, a recently published network meta-analysis indicates that the pain relieving effect of NSAIDs in KOA beyond placebo is small to moderate (depending on drug type).6 Likewise, in the first systematic review on this topic, the pain relieving effect of NSAIDs was estimated to be only 10.1 mm on the 0–100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) better than placebo.7

LLLT is a non-invasive treatment modality,8 9 which has been reported to induce anti-inflammatory effects.9–14 LLLT was compared with NSAID in rats with KOA by Tomazoni et al in a laboratory; NSAID (10 mg diclofenac/knee/session) and LLLT (830 nm wavelength, 6 J/knee/session) reduced similar levels of inflammatory cells and metalloproteinase (MP-3 and MP-13). In addition, LLLT reduced the expression of proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor α), myeloperoxidase and prostaglandin E2 significantly more than NSAID did.10 11

LLLT has been applied to rabbits with KOA three times per week for 8 weeks in a placebo-controlled experiment by Wang et al.12 At the end of treatment week 6, they found that LLLT had significantly reduced pain and synovitis and the production of IL-1β, inducible nitric oxide synthase and MP-3 and slowed down loss of metallopeptidase inhibitor 1. Two weeks later, LLLT had significantly reduced MP-1 and MP-13 and slowed down loss of collagen II, aggrecan and transforming growth factor beta, and the previous changes were sustained.12 These findings indicate that the effects of LLLT increase over time.

Pallotta et al 14 conducted a study on LLLT in rats with acute knee inflammation, which demonstrated that even though LLLT (810 nm) significantly enhanced cyclooxygenase (COX-1 and COX-2) expression it significantly reduced several other inflammatory makers, that is, leucocyte infiltration, myeloperoxidase, IL-1 and IL-6 and especially prostaglandin E2. Pallotta et al 14 hypothesised that the increase in COX levels by LLLT was involved in a production of inflammatory mediators related to the resolution of the inflammatory process.

LLLT is not recommended in major osteoarthritis treatment guidelines. LLLT for KOA was mentioned in the European League Against Rheumatism osteoarthritis guidelines (2018) but not recommended,15 and in the Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines (2018), it was stressed that LLLT should not be considered a core intervention in the management of KOA.16

This may be partly due to conflicting results of two recently published systematic reviews on the current topic.8 17 The conflicting results may arise from omission of relevant trials8 17–23 and unresolved LLLT dose-related issues. Only Huang et al 17 conducted a LLLT dose–response relationship investigation in KOA, that is, by subgrouping the trials by laser dose, but they did not consider that World Association for Laser Therapy (WALT) recommends applying four times the laser dose with continuous irradiation compared to superpulsed irradiation.22 24–26 Thus, it was unknown whether LLLT is effective in KOA, and we saw a need for a new systematic review.

The objectives of the current review were to estimate the effectiveness of LLLT in KOA regarding knee pain, disability and QoL, and we only considered placebo-controlled randomised clinical trials (RCTs) for inclusion to minimise risk of bias.

Methods

This review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement 2009.27

Literature search and selection of studies

Any identified study was included if it was a placebo-controlled RCT involving participants with KOA according to the American College of Rheumatology tool and/or a radiographic inspection with the Kellgren/Lawrence (K/L) criteria, in which LLLT was applied to participants’ knee(s) and self-reported pain, disability and/or QoL was reported. There were no language restrictions.

We updated a search for eligible articles indexed in PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Physiotherapy Evidence Database and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials on 18 February 2019. The database search strings contained synonyms for LLLT and KOA, and keywords were added when optional. The PubMed search string is available in the online supplementary material. The search was continued by reading reference lists of all the eligible trial and relevant review articles,8 17 28 citations29–33 and a laser book34 and involving experts in the field.

Two reviewers (MBS and JMB) each independently selected the trial articles. Both reviewers scrutinised the titles/abstracts of all the publications identified in the search, and any accessible full-text article was retrieved if it was judged potential eligible by at least one reviewer. Both reviewers evaluated the full texts of all potentially eligible retrieved articles and made an independent decision to include or exclude each article, with close attention to the inclusion criteria. When selection disagreements could not be resolved by discussion, a third reviewer (IFN) made the final consensus-based decision. Any retrieved article not fulfilling the inclusion criteria was omitted and listed with reason for exclusion.

Risk-of-bias analysis

Two reviewers (MBS and JJ) each independently evaluated all included trials for risk of bias at the outcome level, using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk-of-bias tool.35 When risk-of-bias disagreements could not be resolved by discussion, a third reviewer (IFN) made the final consensus-based decision. Likelihood of publication bias was assessed with graphical funnel plots.35

Data extraction and meta-analysis

Three reviewers (MBS, JMB and KVF) each independently extracted the data for meta-analysis. Two of the reviewers (MBS and KVF) each independently collected the other trial characteristics. The data-extraction forms were subsequently compared, and data disagreements were resolved by consensus-based discussions. Summary data were extracted, unless published individual participant data were available.21 The results from the included trials for statistical analysis were selected from outcome scales in adherence to hierarchies published by Juhl et al. 36

Pain intensity was the primary outcome. As pain reported with continuous, numeric and categorical/Likert scales highly correlates with pain measured using the VAS, the scores of all pain scales were transformed to 0%–100%, corresponding to 0–100 mm VAS.37 The pain results were combined with the mean difference (MD) method, primarily using change scores, that is, when only final scores could be obtained from a trial, change and final scores were mixed in the analysis, since the MD method allows for this without introducing bias.35

Self-reported disability results were synthesised with the standardised mean difference (SMD) method using change scores solely. The SMD was adjusted to Hedges’ g and interpreted as follows: SMDs of 0.2, ~0.5 and >0.8 represent a small, moderate and large effect, respectively.35

Lack of QoL data prohibited an analysis of this outcome.

Random effects meta-analyses were conducted, and impact from heterogeneity (inconsistency) on the analyses was examined using I2 statistics. An I2 value of 0% indicates no inconsistency, and an I2 value of 100% indicates maximal inconsistency35; the values were categorised as low (25%), moderate (50%) and high (75%).38

SDs for analysis were extracted or estimated from other variance data in a prespecified prioritised order: (1) SD, (2) SE, (3) 95% CI, (4) p value, (5) IQR, (6) median of correlations, (7) visually from graph or (8) other methods.35

The trials were subgrouped by adherence and non-adherence to the WALT recommendations for laser dose per treatment spot, as prespecified. WALT recommends irradiating the knee joint line/synovia with the following doses per treatment spot: ≥4 J using 5–500 mW mean power 780–860 nm wavelength laser and/or ≥1 J using 5–500 mW mean power (>1000 mW peak power) 904 nm wavelength laser.24 25

The main meta-analyses were conducted using two prespecified time points of assessment, that is, immediately after the end of LLLT and last time point of assessment 1–12 weeks after the end of LLLT (follow-up).

MBS performed the meta-analyses, under supervision of JMB, using the software programme Excel 2016 (Microsoft) and Review Manager Version V.5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the conceptualisation or carrying out of this research.

Results

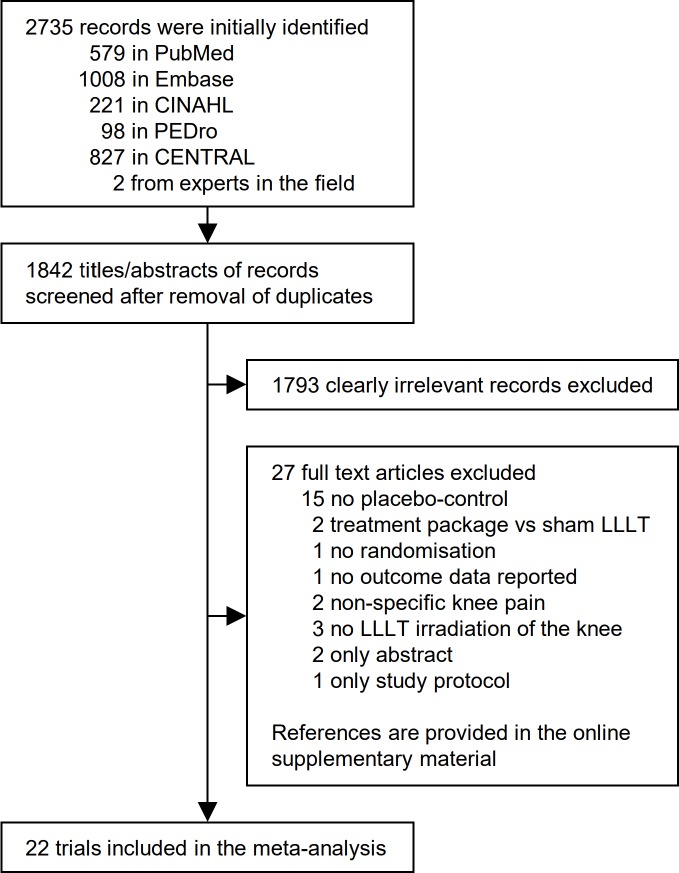

In total, 2735 records were identified in the search, of which 22 trial articles were judged eligible and included in the review (n=1089; figure 1 and tables 1–2) with data for meta-analysis (n=1063). Four included trials were not reported in the English language19 21 23 39 and one included trial was unpublished (Gur and Oktayoglu). Excluded articles initially judged potentially eligible were listed with reasons for omission (online supplementary material).

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the trial identification process. CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; LLLT, low-level laser therapy; PEDro, Physiotherapy Evidence Database.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included trials

| First author | Intervention group at baseline | Control group at baseline | Intervention versus control programme | Outcome scales, week of reassessment |

| Al Rashoud 201431 | N: 26 Women: 62% Age: 52 years BMI: 38 VAS pain: 64 mm K/L: - |

N: 23 Women: 65% Age: 56 years BMI: 37.1 VAS pain: 59 mm K/L: - |

3 weeks of exercise therapy, advice and LLLT versus 3 weeks of exercise therapy, advice and sham LLLT | Pain: VAS (movement) Disability: SKFS QoL: – Week of assessment: 2, 3, 9, 29 |

| Alfredo 2011/201829 52 | N: 24 Women: 75% Age: 61.15 years BMI: 30.16 VAS pain: 53.2 mm K/L: 3 |

N: 22 Women: 80% Age: 62.25 years BMI: 29.21 VAS pain: 35.4 mm K/L: 2 |

3 weeks of LLLT followed by 8 weeks of exercise therapy versus 3 weeks of sham LLLT followed by 8 weeks of exercise therapy | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 3, 11, 24, 37 |

| Alghadir 201432 | N: 20 Women: 50% Age: 55.2 years BMI: 32.34 VAS pain: 74.5 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 20 Women: 40% Age: 57 years BMI: 33.09 VAS pain: 75.5 mm K/L: 2 |

4 weeks of exercise therapy, heat packs and LLLT versus 4 weeks of exercise therapy, heat packs and sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 4 |

| Bagheri 201123 | N: 18 Women: 83.13% Age: 58.32 years BMI: 28.87 VAS pain: 67 mm K/L: – |

N: 18 Women: 83.13% Age: 56.14 years BMI: 27.66 VAS pain: 59 mm K/L: – |

2 weeks of exercise therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, TENS and LLLT versus 2 weeks of exercise therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, TENS and sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC (VAS) 0–100 Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 2 |

| Bülow 199420 | N: 14 Women: – Age: – BMI: – VAS pain: 65.08 mm K/L: – |

N: 15 Women: – Age: – BMI: – VAS pain: 56.35 mm K/L: – |

3 weeks of LLLT versus 3 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: 0–121 Likert scale (movement/rest) Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 3, 6 |

| Delkhosh 201839 | N: 15 Women: 100% Age: 55.9 years BMI: 26.5 VAS pain: 57 mm K/L: – |

N: 15 Women: 100% Age: 58.3 years BMI: 27.8 VAS pain: 45 mm K/L: – |

2 weeks of exercise therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, TENS and LLLT versus 2 weeks of exercise therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, TENS and sham LLLT | Pain: VAS Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 2, 8 |

| Fukuda 201130 | N: 25 Women: 80% Age: 63 years BMI: 30 VAS pain: 61 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 22 Women: 64% Age: 63 years BMI: 30 VAS pain: 62 mm K/L: 2 |

3 weeks of LLLT versus 3 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VNSP (movement) Disability: Lequesne QoL: – Week of assessment: 3 |

| Gur 200333 (1.5 J) | N: 30 Women: 83.3% Age: 58.64 years BMI: 31.17 VAS pain: 73.2 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 30 Women: 80% Age: 60.52 years BMI: 30.27 VAS pain: 67.4 mm K/L: 2 |

14 weeks of exercise therapy and 2 weeks of LLLT versus 14 weeks of exercise therapy and 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS (movement) Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 6, 10, 14 |

| Gur 200333 (1 J) | N: 30 Women: 76.7% Age: 59.8 years BMI: 28.49 VAS pain: 74.4 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 30 Women: 80% Age: 60.52 years BMI: 30.27 VAS pain: 67.4 mm K/L: 2 |

14 weeks of exercise therapy and 2 weeks of LLLT versus 14 weeks of exercise therapy and 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS (movement) Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 6, 10, 14 |

| Gur and Oktayoglu | N: 40 Women: 75% Age: 58.2 years BMI: 29.11 VAS pain: 88 mm K/L: 3 |

N: 40 Women: 72.5% Age: 58.26 years BMI: 30.11 VAS pain: 92 mm K/L: 3 |

14 weeks of exercise therapy and 2 weeks of LLLT versus 14 weeks of exercise therapy and 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS (movement) Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 6, 10, 14 |

| Gworys 201218 | N: 34 Women: – Age: 57.6 BMI: – VAS pain: 54 mm K/L: – |

N: 31 Women: – Age: 67.7 BMI: – VAS pain: – K/L: – |

2 weeks of LLLT versus 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS Disability: Lequesne QoL: – Week of assessment: 2 |

| Hegedűs 200953 | N: 18 Women: – Age: – BMI: – VAS pain: 57.5 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 17 Women: – Age: – BMI: – VAS pain: 56.2 mm K/L: 2 |

4 weeks of LLLT versus 4 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 4, 6, 12 |

| Helianthi 201654 | N: 30 Women: 60% Age: 69 years BMI: 25.8 VAS pain: 60.2 mm K/L: 3 |

N: 29 Women: 82.8% Age: 68 years BMI: 26.3 VAS pain: 54.1 mm K/L: 3 |

5 weeks of LLLT versus 5 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS (movement) Disability: Lequesne QoL: – Week of assessment: 2, 5, 7 |

| Hinman 201441 | N: 71 Women: 39% Age: 63.4 years BMI: 30.7 VAS pain: 41.5 mm K/L: – |

N: 70 Women: 56% Age: 63.8 years BMI: 28.8 VAS pain: 43 mm K/L: – |

12 weeks of LLLT versus 12 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: AQoL-6D Week of assessment: 12, 52 |

| Jensen 198721 | N: 13 Women: – Age: – BMI: – VAS pain: 67 mm K/L: – |

N: 16 Women: – Age: – BMI: – VAS pain: 72.6 mm K/L: – |

1 week of LLLT versus 1 week of sham LLLT | Pain: 0–21 (movement) Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 1 |

| Kheshie 201447 | N: 18 Women: 0% Age: 56.56 years BMI: 28.62 VAS pain: 76.8 mm K/L: 2.5 |

N: 15 Women: 0% Age: 55.6 years BMI: 28.51 VAS pain: 78.7 mm K/L: 2.5 |

6 weeks of exercise therapy and LLLT versus 6 weeks of exercise therapy and sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 6 |

| Koutenaei 201755 | N: 20 Women: 85% Age: 52.3 years BMI: 28.4 VAS pain: 74 mm K/L: 3 |

N: 20 Women: 80% Age: 53 years BMI: 28.6 VAS pain: 65.5 mm K/L: 3 |

2 weeks of exercise therapy and LLLT versus 2 weeks of exercise therapy and sham LLLT | Pain: VAS (movement) Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 2, 4 |

| Mohammed 201856 | N: 20 Women: 85% Age: 55.25 years BMI:≥25 VAS pain: 70 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 20 Women: 85% Age: 50.11 years BMI:≥25 VAS pain: 80 mm K/L: 2 |

4 weeks of LLLT versus 4 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 4 |

| Nambi 201648 | N: 17 Women: – Age: 58 BMI: 26.9 VAS pain: 78 mm K/L: 3.1 |

N: 17 Women: – Age: 60 BMI: 28.3 VAS pain: 76 mm K/L: 3.2 |

4 weeks of exercise therapy, kinesio tape and LLLT versus 4 weeks of exercise therapy, kinesio tape and sham LLLT | Pain: VAS Disability: – QoL: – Week of assessment: 4, 8 |

| Nivbrant 199219 | N: 15 Women: 69.2% Age: 69 years BMI: – VAS pain: 67 mm K/L: – |

N: 15 Women: 84.6% Age: 66 years BMI: – VAS pain: 58 mm K/L: – |

2 weeks of LLLT versus 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: VAS (movement) Disability: Walking disability QoL: – Week of assessment: 2, 3, 6 |

| Rayegani 201243 | N: 12 Women: 83.3% Age: 61.7 years BMI: – VAS pain: 63 mm K/L:<4 |

N: 13 Women: 92.3% Age: 61.2 years BMI: – VAS pain: 52 mm K/L:<4 |

2 weeks of LLLT versus 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 6, 14 |

| Tascioglu 200440 (3 J) | N: 20 Women: 70% Age: 62.86 years BMI: 27.56 VAS pain: 68 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 20 Women: 65% Age: 64.27 years BMI: 29.56 VAS pain: 63.88 mm K/L: 2 |

2 weeks of LLLT versus 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 3, 26 |

| Tascioglu 200440 (1.5 J) | N: 20 Women: 75% Age: 59.92 years BMI: 28.63 VAS pain: 65.72 mm K/L: 2.5 |

N: 20 Women: 65% Age: 64.27 years BMI: 29.56 VAS pain: 63.88 mm K/L: 2 |

2 weeks of LLLT versus 2 weeks of sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 3, 26 |

| Youssef 201642 (904 nm) | N: 18 Women: 66.7% Age: 67.5 BMI:<40 VAS pain: 51.67 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 15 Women: 66.7% Age: 66.3 years BMI:<40 VAS pain: 50 mm K/L: 2 |

8 weeks of exercise therapy and LLLT versus 8 weeks of exercise therapy and sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 8 |

| Youssef 201642 (880 nm) | N: 18 Women: 61.1% Age: 67.3 BMI: <40 VAS pain: 52.50 mm K/L: 2 |

N: 15 Women: 66.7% Age: 66.3 years BMI: <40 VAS pain: 50 mm K/L: 2 |

8 weeks of exercise therapy and LLLT versus 8 weeks of exercise therapy and sham LLLT | Pain: WOMAC Disability: WOMAC QoL: – Week of assessment: 8 |

The values for age and body mass index (BMI) are means and the values for K/L grade are medians. Baseline Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores have been extracted or estimated as described in the Method section. Week of assessment in bold denotes time point used for the main meta-analyses.

AQoL-6D, Assessment of Quality of Life 6 Dimensions; DIQ, Disability Index Questionnaire; K/L, Kellgren/Lawrence; LLLT, low-level laser therapy; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; QoL, quality of life; SKFS, Saudi Knee Function Scale; TENS, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation; VNPS, Visual Numerical Pain Scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Table 2.

Laser therapy characteristics of the included trials

| First author | Treated area | Wavelength (nm) | Joules per treatment spot | Mean output power (mW) | Seconds per treated spot | Number of spots treated | Sessions/sessions per week |

| Al Rashoud 201431* | Knee joint line (medial and lateral) and acupoints (SP9, SP10, ST36) | 830 | 1.2 | 30 | 40 | 5 | 9/3 |

| Alfredo 2011, 201829 52 | Knee joint line (medial and lateral) | 904 | 3 | 60 | 50 | 9 | 9/3 |

| Alghadir 201432 | Knee condyles, joint line (medial and lateral) and popliteal fossa | 850 | 6 | 100 | 60 | 8 | 8/2 |

| Bagheri 201123* | Knee joint line | 830 | 3 | 30 | 100 | 10 | 10/5 |

| Bülow 199420* | Painful spots in 0–10 cm radius of the knee joint line | 830 | 1.5–4.5 | 25 | 60–180 | 5–15 | 9/3 |

| Delkhosh 201839 | Knee joint | 830 | 5 | 30 | 167 | 5 | 10/5 |

| Fukuda 201130 | Front knee capsule | 904 | 3 | 60 | 50 | 9 | 9/3 |

| Gur 200333 (1.5 J) | Anterolateral and anteromedial portal of the knee | 904 | 1.5 | 10 | 150 | 2 | 10/5 |

| Gur 200333 (1 J) | Anterolateral and anteromedial portal of the knee | 904 | 1 | 11.2 | 90 | 2 | 10/5 |

| Gur and Oktayoglu | Anterolateral and anteromedial portal of the knee | 904 | 1.5 | 10 | 150 | 2 | 10/5 |

| Gworys 201218 | Knee joint line, patellofemoral joint and popliteal fossa | 810 | 8 | 400 | 20 | 12 | 10/5 |

| Hegedűs 200953 | Knee joint line, popliteal fossa and condyles | 830 | 6 | 50 | 120 | 8 | 8/2 |

| Helianthi 201654 | Knee joint line (lateral) and acupoints (ST36, SP9, GB34, EX-LE-4) | 785 | 4 | 50 | 80 | 5 | 10/2 |

| Hinman 201441* | Acupoints (locations not stated) | 904 | 0.2 | 10 | 20 | 6 | 8-12/0.67–1 |

| Jensen 198721* | Knee joint line (medial and lateral), apex and basis of patellae | 904 | 0.054 | 0.3 | 180 | 4 | 5/5 |

| Kheshie 201447† | Front knee | 830 | – | 160 | – | – | 12/2 |

| Koutenaei 201755 | Front knee, popliteal fossa and femur condyles in the popliteal cavity | 810 | 7 | 100 | 70 | 8 | 10/5 |

| Mohammed 201856 | Knee joint line (lateral) and acupoints (ST36, Sp10, GB, ashi) | 808 | 5.4 | 90 | 60 | 7 | 12/3 |

| Nambi 201648 | Knee joint line, condyles and popliteal fossa | 904 | 1.5 | 25 | 60 | 8 | 12/3 |

| Nivbrant 199219* | Knee joint line (medial and lateral) and acupoints (ST34, SP10, X32) | 904 | 0.72 | 4 | 180 | 7 | 6/3 |

| Rayegani 201243* | Knee joint line and popliteal fossa | 880 | 6 | 50 | 120 | 8 | 10/5 |

| Tascioglu 200440 (3 J)* | Painful spots on the knee | 830 | 3 | 50 | 60 | 5 | 10/5 |

| Tascioglu 200440 (1.5 J)* | Painful spots on the knee | 830 | 1.5 | 50 | 30 | 5 | 10/5 |

| Youssef 201642 (904 nm) | Knee joint line (medial and lateral) | 904 | 3 | 60 | 50 | 9 | 16/2 |

| Youssef 201642 (880 nm)* | Knee joint line (medial and lateral), epicondyles and popliteal fossa | 880 | 6 | 50 | 120 | 8 | 16/2 |

*Non-recommended low-level laser therapy dose.

†1250 Joules per session.

bmjopen-2019-031142supp001.pdf (7.7MB, pdf)

At the group level, the mean age of the participants was 60.25 (50.11–69) years (data from 19 trials), the mean percentage of women was 69.63% (0–100%; data from 17 trials), the mean body mass index of the participants was 29.55 (25.8–38; data from 14 trials), the mean of median K/L grades was 2.37 (data from 13 trials) and the mean baseline pain was 63.61 mm VAS (35.25–92) (data from 22 trials). LLLT was used as an adjunct to exercise therapy in 11 trials. The mean duration of the treatment periods was 3.53 weeks with the recommended LLLT doses and 3.7 weeks with the non-recommended LLLT doses (tables 1 and 2). Non-recommended LLLT doses were applied in nine of the trials. That is, Al Rashoud et al,31 Bülow et al,20 Tascioglu et al 40 and Bagheri et al 23 applied too few (<4) Joules per treatment spot with 830 nm wavelength, Jensen et al,21 Nivbrant et al 19 and Hinman et al 41 applied too few (<1) Joules per treatment spot with 904 nm wavelength and Youssef et al 42 (one group) and Rayegani et al 43 used continuous laser with too long of a wavelength (880 nm; table 2). No adverse event was reported by any of the trial authors. None of the trial authors stated receiving funding from the laser industry (online supplementary material).

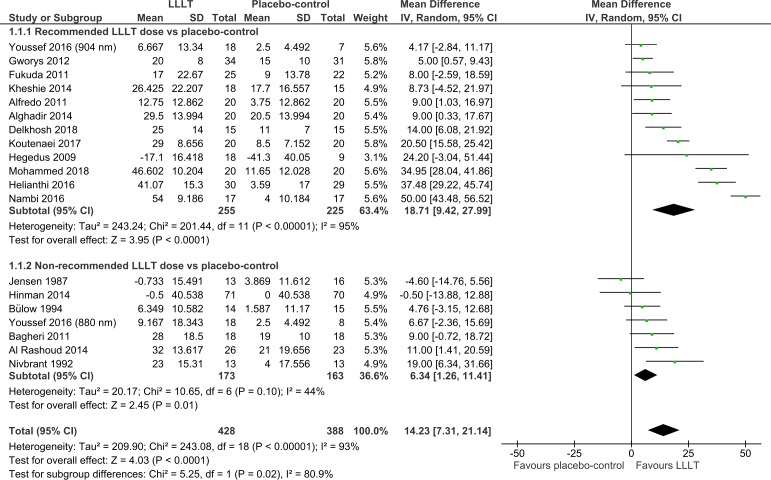

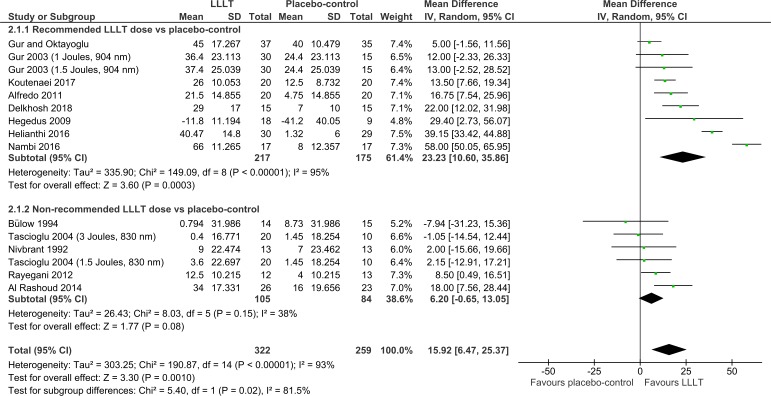

Overall, pain was significantly reduced by LLLT compared with the placebo control at the end of therapy (14.23 mm VAS (95% CI 7.31 to 21.14); I2=93%; n=816; figure 2) and during follow-ups 1–12 weeks later (15.92 mm VAS (95% CI 6.47 to 25.37); I2=93%; n=581; figure 3). The dose subgroup analyses demonstrated that pain was significantly reduced by the recommended LLLT doses compared with placebo at the end of therapy (18.71 mm (95% CI 9.42 to 27.99); I2=95%; n=480; figure 2) and during follow-ups 2–12 weeks later (23.23 mm VAS (95% CI 10.60 to 35.86); I2=95%; n=392; figure 3). The dose subgroup analyses demonstrated that pain was significantly reduced by the non-recommended LLLT doses compared with placebo at the end of therapy (6.34 mm VAS (95% CI 1.26 to 11.41); I2=44%; n=336; figure 2), but the difference during follow-ups 1–12 weeks later was not significant (6.20 mm VAS (95% CI −0.65 to 13.05); I2=38%; n=189; figure 3). The between-subgroup differences (recommended versus non-recommended doses) in pain results were significantly in favour of the recommended LLLT doses regarding both time points (p=0.02 and 0.02; figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Pain results from immediately after the end of therapy. LLLT, low-level laser therapy.

Figure 3.

Pain results from follow-ups 1–12 weeks after the end of therapy. LLLT, low-level laser therapy.

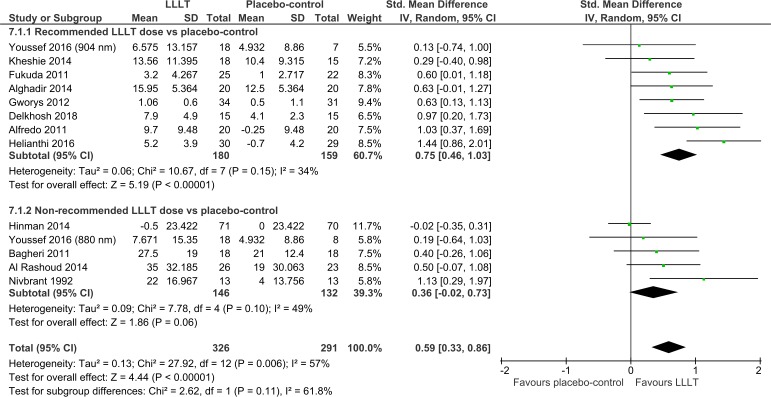

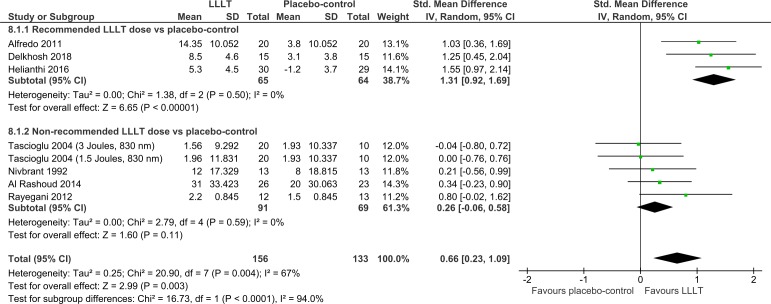

Overall, disability was significantly reduced by LLLT compared with placebo at the end of therapy (SMD=0.59 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.86); I2=57%; n=617; figure 4) and during follow-ups 1–12 weeks later (SMD=0.66 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.09); I2=67%; n=289; figure 5). The dose subgroup analyses demonstrated that disability was significantly reduced by the recommended LLLT doses compared with placebo at the end of therapy (SMD=0.75 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.03); I2=34%; n=339; figure 4) and during follow-ups 2–8 weeks later (SMD=1.31 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.69); I2=0%; n=129; figure 5). The dose subgroup analyses demonstrated that disability was neither significantly reduced by the non-recommended LLLT doses compared with placebo at the end of therapy (SMD=0.36 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.73); I2=49%; n=278; figure 4) nor during follow-ups 1–12 weeks later (SMD=0.26 (95% CI −0.06 to 0.58); I2=0%; n=160; figure 5). The between-subgroup differences in disability results were in favour of the recommended LLLT doses over the non-recommended LLLT doses but only significantly regarding one of two time points (p=0.11 and <0.0001; figures 4–5).

Figure 4.

Disability results from immediately after the end of therapy. LLLT, low-level laser therapy.

Figure 5.

Disability results from follow-ups 1–12 weeks after the end of therapy. LLLT, low-level laser therapy.

No QoL meta-analysis was performed because this outcome was only assessed in a single trial, that is, by Hinman et al who applied a non-recommended LLLT dose and reported insignificant results.41

The funnel plots indicated that there was no publication bias (online supplementary material). We additionally checked for small study bias by reducing the statistical weight of the smallest studies through a change from random to fixed effects models and this led to similar mean effect estimates, indicating that there was no small study bias (online supplementary material).35

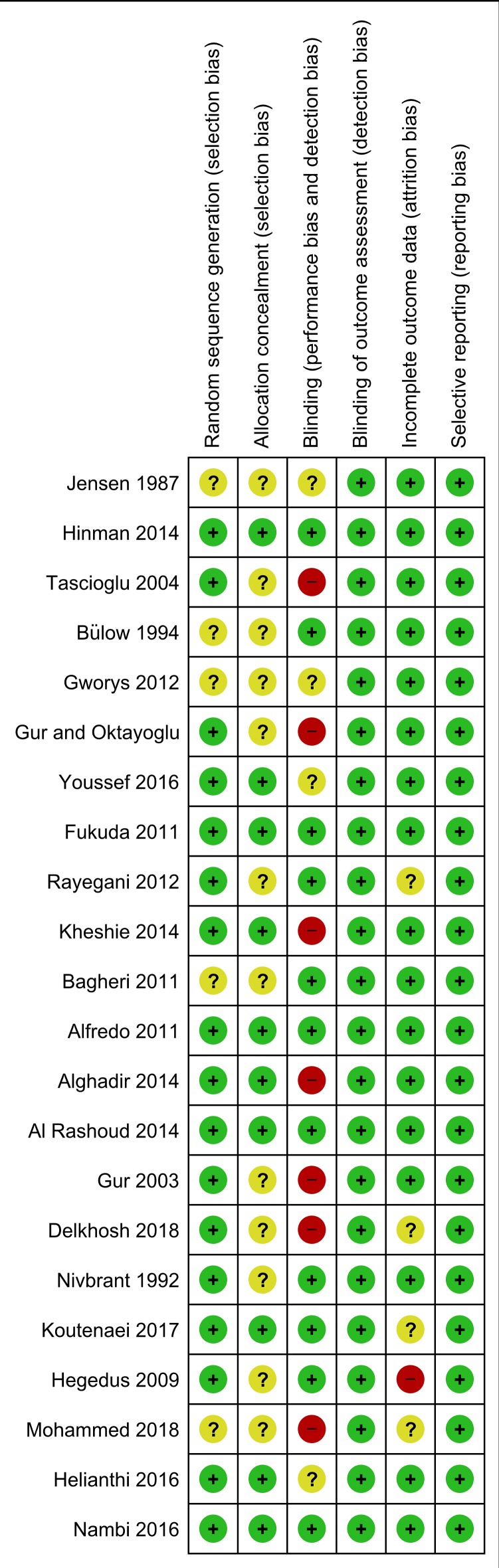

Methodological quality of the included trials was judged adequate (low risk of bias), unclear (unclear risk of bias) and inadequate (high risk of bias) in 75%, 19% and 6% instances, respectively. Risk of detection bias and reporting bias appeared low in all the trials. There was a lack of information regarding random sequence generation in five trials, allocation concealment in 12 trials, blinding of therapist in four trials and incomplete outcome data in four trials. Therapist blinding was inadequate in seven trials and there was an inadequate handling of data in a single trial (figure 6). However, risk-of-bias subgroup analyses conducted post hoc revealed that there was no statistically significant interaction between the effect estimates and risk of bias, and the analyses did not display a drop in statistical heterogeneity (online supplementary material). Support for our risk of bias judgments is available (online supplementary material).

Figure 6.

Risk-of-bias plot of the included trials. The trials are ranked by mean pain effect estimates, that is, more laser positive results in the bottom of the figure; the plot is based on the results from the main pain analyses (immediately after the end of therapy, primarily).

Neither did the levels of statistical heterogeneity change when we switched from the MD to the SMD method post hoc (online supplementary material).

Post hoc analyses demonstrated that LLLT was significantly superior to placebo both with exercise therapy (p=0.0009 for pain and p<0.0001 for disability) and without exercise therapy (p=0.01 for pain and p=0.008 for disability) as cointervention (online supplementary material).

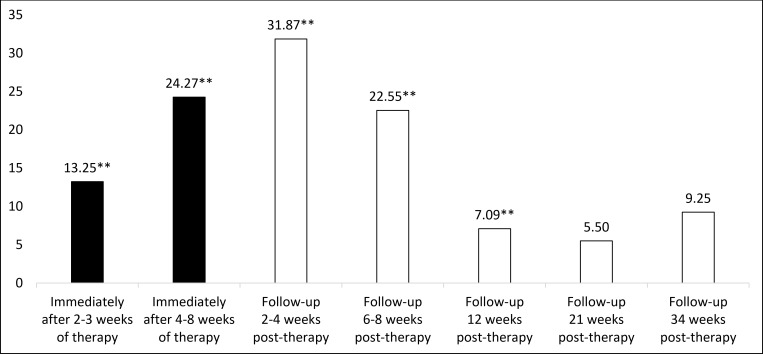

Post hoc analyses were performed to more precisely estimate the pain time-effect profile for the recommended LLLT doses by imputing the results of the trials with these doses in subgroups with narrower time intervals. Pain was significantly reduced by the recommended LLLT doses compared with placebo immediately after therapy weeks 2–3 and 4–8 and at follow-ups 2–4, 6–8 and 12 weeks later; the peak point was 2–4 weeks after the end of therapy (31.87 mm VAS beyond placebo (95% CI 18.18 to 45.56); I2=93%; n=322). The 21-week and 34-week follow-up pain results were not statistically significant (figure 7 and online supplementary material). The statistical heterogeneity in the main pain analyses of the recommended LLLT doses was high (I2=95%; figures 2–3) but the mean statistical heterogeneity of the five subgroups covering the same time period was only moderate (I2=58%; figure 7 and online supplementary material).

Figure 7.

Pain time-effect profile (recommended low-level laser therapy (LLLT) doses versus placebo-control). Values on the y-axis are mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) pain results. Positive VAS score indicates that the recommended LLLT doses are superior to placebo. The related forest plot is available (online supplementary material). **The recommended LLLT doses are highly statistically significantly superior to placebo (p≤0.01).

Discussion

Our meta-analyses showed that pain and disability were significantly reduced by LLLT compared with placebo. We subgrouped the included trials according to the WALT recommendations (2010) for laser dose per treatment spot, and this revealed a significant dose–response relationship. Our principal finding is that the recommended LLLT doses offer clinically relevant pain relief in KOA. The non-recommended LLLT doses provided no or little positive effect.

The absolute minimally clinically important improvement (MCII) of pain in KOA has been estimated to be 19.9, 17 and 9 units on a 0–100 scale in 2005, 2012 and 2015, respectively.44–46 It is important to note that the MCII of pain is a within-subject improvement and depends on baseline pain intensity.44–46 The pain reduction from the recommended LLLT doses was significantly superior to placebo even at follow-ups 12 weeks after the end of therapy, and the difference was greater than 20 mm VAS from the final 4–8 weeks of therapy through follow-ups 6–8 weeks after the end of therapy. Interestingly, the pain reduction from the recommended LLLT doses peaked at follow-ups 2–4 weeks after the end of therapy (31.87 mm VAS highly significantly beyond placebo).

Disability was also significantly reduced by the recommended LLLT doses compared with placebo, that is, to a moderate extent at the end of therapy (SMD=0.75) and to a large extent during follow-ups 2–8 weeks later (SMD=1.31). More trials with disability assessments are needed to precisely estimate the effect of LLLT on this outcome during follow-up.

Furthermore, our analyses demonstrated that LLLT is effective in KOA both with and without exercise therapy as cointervention. Strength training was seemingly only used as an adjunct to LLLT in two of the included trials,47 48 and thus more trials with this combination of treatments are needed.

Risk of bias of the included trials appeared insignificant and could not explain the statistical heterogeneity (online supplementary material). We find it plausible that some of the statistical heterogeneity of the overall analyses is associated with the dose subgroup criteria (wavelength-specific laser doses per treatment spot) since the mean levels of statistical heterogeneity of the subgroup analyses were consistently lower than the overall levels. It is unknown to us whether other differences in the LLLT protocols impacted the results.

The statistical heterogeneity in the main pain analyses of the recommended LLLT doses was high, and some of it can be explained by the pooling of results from various time points of assessment given the pain reduction increased and subsequent decreased with time; the pain reduction time profile showed a drop in statistical heterogeneity to a moderate level.

According to WALT, the osteoarthritic knee should be laser irradiated to reduce inflammation and promote tissue repair.24 25 49 One of the discrepancies from our review and previously published reviews of the same topic is that we omitted the RCT by Yurtkuran et al,8 17 28 50 as they solely applied laser to an acupoint located distally from the knee joint (spleen 9).

In line with our findings and the WALT dose recommendations, Joensen et al 26 observed that the percentage of laser penetrating rat skin at 810 and 904 nm wavelength was 20% and 38%–58%, respectively. That is, to deliver the same dose beneath the skin, 2.4 times the energy on the skin surface is required with an 810 nm laser compared with a 904 nm laser device. This may be due to the different wavelengths and/or because 904 nm laser is superpulsed (pulse peak power ≥10 000 mW typically), whereas shorter wavelength laser is delivered continuously or with less intense pulsation.26 The estimated median dose applied with the recommended LLLT was 6 and 3 J per treatment spot with 785–860 and 904 nm wavelength laser, respectively. Most of the trial authors reported LLLT parameters in detail but did not state whether the laser devices were calibrated. Therefore, in the LLLT trials with non-significant effect estimates, equipment failure cannot be ruled out.

It is important to note that no adverse events were reported by any of the trial authors and the dropout rate was minor, indicating that LLLT is harmless.

Our clinical findings that the effect of LLLT progresses over time is in line with in vivo results of Wang et al.12 The positive effect from LLLT seems to last longer than those of widely recommended painkiller drugs.51 The effect of using the NSAID tiaprofenic acid, for example, is probably gone within a week, unless the treatment is continued.51 Future trials should investigate whether booster sessions of LLLT can prolong the positive effect. Comparative cost-effectiveness analyses of LLLT and NSAIDs would also be of great interest.

Strengths and limitations of this study

In contrast to previous reviews on the current topic, our review was conducted in conformance with an a priori published protocol,8 17 28 which included a detailed plan for statistical analysis (eg, laser dose subgroup criteria). Furthermore, this is the first review on this topic without language restrictions,8 17 28 and this expansion proved important since four (18%) of the included trials were reported in non-English language.19 21 23 39

We conducted a series of meta-analyses illustrating the effect of LLLT on pain over time. To ensure high reproducibility of the meta-analyses, three persons each independently extracted the outcome data from the included trial articles.

This review is not without limitations. It lacks QoL analyses, a detailed disability time-effect analysis and direct comparisons between LLLT and other interventions.

Conclusions

LLLT reduces pain and disability in KOA at 4–8 J with 785–860 nm wavelength and at 1–3 J with 904 nm wavelength per treatment spot.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MBS, JMB and HL wrote the PROSPERO protocol. MBS and JMB selected the trials, with the involvement of IFN when necessary. MBS and JJ judged the risk of bias, with the involvement of IFN when necessary. MBS and IFN did the translations. MBS, JMB and KVF extracted the data. MBS performed the analyses, under supervision of JMB. All the authors participated in interpreting of the results. MBS drafted the first version of the manuscript, and subsequently revised it, based on comments by RÁBL-M, HS and all the other authors. All the authors read and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The University of Bergen funded this research.

Competing interests: JMB and RÁBL-M are post-presidents and former board members of World Association for Laser Therapy, a non-for-profit research organization from which they have never received funding, grants or fees. The other authors declared that they had no conflict of interests related to this work.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The dataset for meta-analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The corresponding author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1. Heidari B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Caspian J Intern Med 2011;2:205–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:16–21. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3 10.1002/14651858.CD005523.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, et al. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:622–36. 10.1002/art.38290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rannou F, Pelletier J-P, Martel-Pelletier J. Efficacy and safety of topical NSAIDs in the management of osteoarthritis: evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;45:S18–21. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bannuru RR, Schmid CH, Kent DM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:46–54. 10.7326/M14-1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bjordal JM, Ljunggren AE, Klovning A, et al. Non-Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, in osteoarthritic knee pain: meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ 2004;329 10.1136/bmj.38273.626655.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rayegani SM, Raeissadat SA, Heidari S, et al. Safety and effectiveness of low-level laser therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Lasers Med Sci 2017;8:S12–19. 10.15171/jlms.2017.s3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamblin MR. Can osteoarthritis be treated with light? Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15 10.1186/ar4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tomazoni SS, Leal-Junior ECP, Pallotta RC, et al. Effects of photobiomodulation therapy, pharmacological therapy, and physical exercise as single and/or combined treatment on the inflammatory response induced by experimental osteoarthritis. Lasers Med Sci 2017;32:101–8. 10.1007/s10103-016-2091-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomazoni SS, Leal-Junior ECP, Frigo L, et al. Isolated and combined effects of photobiomodulation therapy, topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical activity in the treatment of osteoarthritis induced by papain. J Biomed Opt 2016;21:108001 10.1117/1.JBO.21.10.108001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang P, Liu C, Yang X, et al. Effects of low-level laser therapy on joint pain, synovitis, anabolic, and catabolic factors in a progressive osteoarthritis rabbit model. Lasers Med Sci 2014;29:1875–85. 10.1007/s10103-014-1600-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Assis L, Almeida T, Milares LP, et al. Musculoskeletal atrophy in an experimental model of knee osteoarthritis: the effects of exercise training and low-level laser therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2015;94:609–16. 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pallotta RC, Bjordal JM, Frigo L, et al. Infrared (810-nm) low-level laser therapy on rat experimental knee inflammation. Lasers Med Sci 2012;27:71–8. 10.1007/s10103-011-0906-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R, et al. EULAR recommendations for the health professional's approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:797–807. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Collins NJ, Hart HF, Mills KAG. Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: rehabilitation and outcomes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:378–91. 10.1016/j.joca.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang Z, Chen J, Ma J, et al. Effectiveness of low-level laser therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:1437–44. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gworys K, Gasztych J, Puzder A, et al. Influence of various laser therapy methods on knee joint pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2012;14:269–77. 10.5604/15093492.1002257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nivbrant B, Friberg S. Laser tycks ha effekt pa knaledsartros men vetenskapligt bevis saknas [Swedish]. Lakartidningen [Journal of the Swedish Medical Association] 1992;89:859–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bülow PM, Jensen H, Danneskiold-Samsøe B. Low power Ga-Al-As laser treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee. A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Scand J Rehabil Med 1994;26:155–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jensen H, Harreby M, Kjer J. Infrarød laser - effekt ved smertende knæartrose? [Danish]. Ugeskr Laeger 1987;149:3104–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stausholm MB, Bjordal JM, Lopes-Martins RAB, et al. Methodological flaws in meta-analysis of low-level laser therapy in knee osteoarthritis: a letter to the editor. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017;25:e9–10. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bagheri SR, Fatemi E, Fazeli SH, et al. Efficacy of low level laser on knee osteoarthritis treatment [Persian]. Koomesh 2011;12:285–92. [Google Scholar]

- 24. WALT Recommended treatment doses for low level laser therapy 780-860 nm wavelength: world association for laser therapy, 2010. Available: http://waltza.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Dose_table_780-860nm_for_Low_Level_Laser_Therapy_WALT-2010.pdf

- 25. WALT Recommended treatment doses for low level laser therapy 904 nm wavelength: world association for laser therapy, 2010. Available: http://waltza.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Dose_table_904nm_for_Low_Level_Laser_Therapy_WALT-2010.pdf

- 26. Joensen J, Øvsthus K, Reed RK, et al. Skin penetration time-profiles for continuous 810 nm and Superpulsed 904 nm lasers in a rat model. Photomed Laser Surg 2012;30:688–94. 10.1089/pho.2012.3306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Lopes-Martins RAB, et al. Short-Term efficacy of physical interventions in osteoarthritic knee pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007;8:51 10.1186/1471-2474-8-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alfredo PP, Bjordal JM, Dreyer SH, et al. Efficacy of low level laser therapy associated with exercises in knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blind study. Clin Rehabil 2012;26:523–33. 10.1177/0269215511425962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fukuda VO, Fukuda TY, Guimarães M, et al. Short-Term efficacy of low-level laser therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Rev Bras Ortop 2011;46:526–33. 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30407-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Al Rashoud AS, Abboud RJ, Wang W, et al. Efficacy of low-level laser therapy applied at acupuncture points in knee osteoarthritis: a randomised double-blind comparative trial. Physiotherapy 2014;100:242–8. ‐ 10.1016/j.physio.2013.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alghadir A, Omar MTA, Al-Askar AB, et al. Effect of low-level laser therapy in patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis: a single-blinded randomized clinical study. Lasers Med Sci 2014;29:749–55. 10.1007/s10103-013-1393-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gur A, Cosut A, Sarac AJ, et al. Efficacy of different therapy regimes of low-power laser in painful osteoarthritis of the knee: a double-blind and randomized-controlled trial. Lasers Surg Med 2003;33:330–8. 10.1002/lsm.10236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tunér J, Hode L. The new laser therapy Handbook: a guide for research scientists, doctors, dentists, veterinarians and other interested parties within the medical field. Grängesberg: Prima Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, 2011. Available: http://handbook.cochrane.org/ [Accessed 3 Dec 2015].

- 36. Juhl C, Lund H, Roos EM, et al. A hierarchy of patient-reported outcomes for meta-analysis of knee osteoarthritis trials: empirical evidence from a survey of high impact journals. Arthritis 2012;2012:1–17. 10.1155/2012/136245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bolognese JA, Schnitzer TJ, Ehrich EW. Response relationship of vas and Likert scales in osteoarthritis efficacy measurement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:499–507. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00082-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delkhosh CT, Fatemy E, Ghorbani R, et al. Comparing the immediate and long-term effects of low and high power laser on the symptoms of knee osteoarthritis [Persian]. Journal of mazandaran university of medical sciences 2018;28:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tascioglu F, Armagan O, Tabak Y, et al. Low power laser treatment in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Swiss Med Wkly 2004;134:254–8. doi:2004/17/smw-10518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hinman RS, McCrory P, Pirotta M, et al. Acupuncture for chronic knee pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:1313–22. 10.1001/jama.2014.12660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Youssef EF, Muaidi QI, Shanb AA. Effect of laser therapy on chronic osteoarthritis of the knee in older subjects. J Lasers Med Sci 2016;7:112–9. 10.15171/jlms.2016.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rayegani SM, Bahrami MH, Elyaspour D, et al. Therapeutic effects of low level laser therapy (LLLT) in knee osteoarthritis, compared to therapeutic ultrasound. J Lasers Med Sci 2012;3:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant changes in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the minimal clinically important improvement. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:29–33. 10.1136/ard.2004.022905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bellamy N, Hochberg M, Tubach F, et al. Development of multinational definitions of minimal clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptomatic state in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:972–80. 10.1002/acr.22538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tubach F, Ravaud P, Martin-Mola E, et al. Minimum clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state in pain and function in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic back pain, hand osteoarthritis, and hip and knee osteoarthritis: results from a prospective multina. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1699–707. 10.1002/acr.21747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kheshie AR, Alayat MSM, Ali MME. High-Intensity versus low-level laser therapy in the treatment of patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci 2014;29:1371–6. 10.1007/s10103-014-1529-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nambi SG, Kamal W, George J, et al. Radiological and biochemical effects (CTX-II, MMP-3, 8, and 13) of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in chronic osteoarthritis in Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia. Lasers Med Sci 2016;32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lopes-Martins RAB, Marcos RL, Leal-Junior ECP, et al. Low-Level laser therapy and world association for laser therapy dosage recommendations in musculoskeletal disorders and injuries. Photomed Laser Surg 2018;36:457–9. 10.1089/pho.2018.4493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yurtkuran M, Alp A, Konur S, et al. Laser acupuncture in knee osteoarthritis: a double-blind, randomized controlled study. Photomed Laser Surg 2007;25:14–20. 10.1089/pho.2006.1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Scott DL, Berry H, Capell H, et al. The long-term effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology 2000;39:1095–101. 10.1093/rheumatology/39.10.1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alfredo PP, Bjordal JM, Junior WS, et al. Long-Term results of a randomized, controlled, double-blind study of low-level laser therapy before exercises in knee osteoarthritis: laser and exercises in knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:173–8. 10.1177/0269215517723162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hegedűs B, Viharos L, Gervain M, et al. The effect of low-level laser in knee osteoarthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Photomed Laser Surg 2009;27:577–84. 10.1089/pho.2008.2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Helianthi DR, Simadibrata C, Srilestari A, et al. Pain reduction after laser acupuncture treatment in geriatric patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Med Indones 2016;48:114–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Koutenaei FR, Mosallanezhad Z, Naghikhani M, et al. The effect of low level laser therapy on pain and range of motion of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Physical Treatments - Specific Physical Therapy 2017;7:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mohammed N, Allam H, Elghoroury E, et al. Evaluation of serum beta-endorphin and substance P in knee osteoarthritis patients treated by laser acupuncture. J Complement Integr Med 2018;15 10.1515/jcim-2017-0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031142supp001.pdf (7.7MB, pdf)