Abstract

Introduction

Depression is highly prevalent and the leading contributor to the burden of disease in young people worldwide, making it an ongoing priority for early intervention. As the current evidence-based interventions of medication and psychological therapy are only modestly effective, there is an urgent need for additional treatment strategies. This paper describes the rationale of the Improving Mood with Physical ACTivity (IMPACT) trial. The primary aim of the IMPACT trial is to determine the effectiveness of a physical activity intervention compared with psychoeducation, in addition to routine clinical care, on depressive symptoms in young people. Additional aims are to evaluate the intervention effects on anxiety and functional outcomes and examine whether changes in physical activity mediate improvements in depressive symptoms.

Methods and analysis

The study is being conducted in six youth mental health services across Australia and is using a parallel-group, two-arm, cluster randomised controlled trial design, with randomisation occurring at the clinician level. Participants aged between 12 years and 25 years with moderate to severe levels of depression are randomised to receive, in addition to routine clinical care, either: (1) a physical activity behaviour change intervention or (2) psychoeducation about physical activity. The primary outcome will be change in the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, with assessments occurring at baseline, postintervention (end-point) and 6-month follow-up from end-point. Secondary outcome measures will address additional clinical outcomes, functioning and quality of life. IMPACT is to be conducted between May 2014 and December 2019.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee on 8 June 2014 (HREC 1442228). Trial findings will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at conferences. Key messages will also be disseminated by the youth mental health services organisation (headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation).

Trial registration number

ACTRN12614000772640.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, Depression & mood disorders, Clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study is a cluster randomised controlled trial, which reduces the risk of contamination bias and uses validated outcome measures.

The study is conducted in real-world clinical services, which increases the likelihood of translation into practice.

A large number of participants needs to be recruited to provide sufficient power to demonstrate a relevant effect size.

Limited capacity to provide ongoing supervision for clinicians in implementing the intervention.

Background

Depression is highly prevalent1 and is the leading cause of disability in young people worldwide.2 Associated adverse consequences include impairments in academic attainment and achievement,3 unemployment or underemployment,3 and increased risk of self-harm and suicide.4 Effective treatments have the potential to improve the health and functioning of young people and prevent the entrenchment of problems with relationships, education and health.5 The current international evidence-based clinical practice guideline for treating depression in children and young people recommends cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) as the first-line treatment for moderate to severe depression, with or without the antidepressant medication, fluoxetine.6 Recent evidence from meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown the effect sizes of both CBT and antidepressant medication are smaller than previously reported.7–9 This suggests that many young people either fail to respond or do not show a clinically significant change even after receiving the best available guideline-recommended treatment delivered in controlled trials.7 10

With such modest effects of first-line treatments, there is a need for additional therapeutic strategies. One such strategy with an emerging evidence base is exercise or physical activity as an augmentation or adjunct treatment.11 Large cross-sectional and cohort studies show that less physically active young people are currently more likely to be depressed and are at greater risk of developing future depression.12 13 While insufficient physical activity places all young people at greater risk of poor physical health, including higher rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and premature death,14 15 young people with depression are far more likely to be physically inactive than the general population, placing them at higher risk of long-term poorer physical health.16 17 In addition to mental and physical health benefits, physical activity is a low-stigma intervention that has few side effects.18 19 Both of these factors are important to help-seeking young people.20

There is strong evidence from RCTs and meta-analyses that physical activity is an effective intervention for depression in adults (standard mean difference (SMD)=1.135, p<0.001)21 and reduces the risk of suicidal ideation.22 Although not as robust as the evidence base for adults,21 physical activity interventions for young people with depression show similar findings.23–25 A recent meta-analysis, conducted by members of our investigator team, of RCTs in young people aged 12–25 years established that physical activity is effective in reducing depression symptoms.26 Data from 771 participants across 16 trials showed a large effect of supervised physical activity interventions on depression symptoms compared with controls in subthreshold samples (SMD=−0.82, p<0.01). The effect remained robust in five trials of young people with a diagnosis of depression (SMD=−0.72, p<0.01). However, clinical applications are hindered by the majority of studies being of low quality, lack of longer term follow-up and inadequate consideration of real-world implementation factors.26

Our group developed an intervention and evaluated it in the first RCT examining the potential benefits of low-intensity, simple psychological and unsupervised physical activity interventions for young people (n=176) with high prevalence mental health problems,25 implemented within community-based youth mental health services. Conducted in two such services in the western region of Melbourne, Australia, the trial used a factorial design to compare the effects of a psychological intervention (problem solving therapy vs supportive counselling) and a physical activity intervention (behavioural change vs psychoeducation) delivered in up six sessions (an average of 4.3 sessions were completed). Importantly, we recruited men and women, making this the first physical activity study to be conducted with young men with depression or anxiety symptoms. The physical activity intervention focused on addressing barriers to engaging in physical activity and creating individualised activity plans. Postintervention data showed the main effect of the physical activity intervention was significant when compared with the control condition (psychoeducation), resulting in a clinically meaningful reduction in depression symptoms with a medium effect size (d=0.41; (95% CI 0.07 to 0.76)), measured by the Beck Depression Inventory.27 Those in the physical activity intervention group reported the greatest improvement regardless of the type of psychological intervention received.25 However, it is important to note that the physical activity intervention was delivered in conjunction with manualised psychological therapies by research therapists rather than as part of routine clinical care.

Study rationale

Current first-line treatments for depression in young people are, at best, modestly effective. Augmentation with an additional intervention such as physical activity is a strong candidate to improve response to treatment. The results from our earlier study indicate that physical activity in combination with psychological treatment is effective in reducing depression symptoms in young people.25 However, as clinicians do not routinely include physical activity interventions in standard care,28 the opportunity to improve depression and functional outcomes and prevent poor physical health for young people with depression may be missed.13 28 This lack of integration likely occurs because clinicians are not aware of the evidence, are unsure how to implement physical activity interventions or lack the time and resources.28 29 By providing training and clinical resources, the objective of the current study is to determine the effectiveness of a physical activity behaviour change intervention when used as an adjunct to routine clinical care, delivered in real-world mental health contexts.

Methods and analysis

Study aims

The aims of this study are to test the effectiveness of a physical activity behaviour change intervention, compared with psychoeducation about physical activity, in addition to routine clinical care in improving depressive symptoms (primary outcome) in young help-seekers with depression. Secondary outcomes include the effect of the intervention on anxiety symptoms and functioning and to examine whether changes in physical activity mediate improvements in depressive symptoms.

Study design

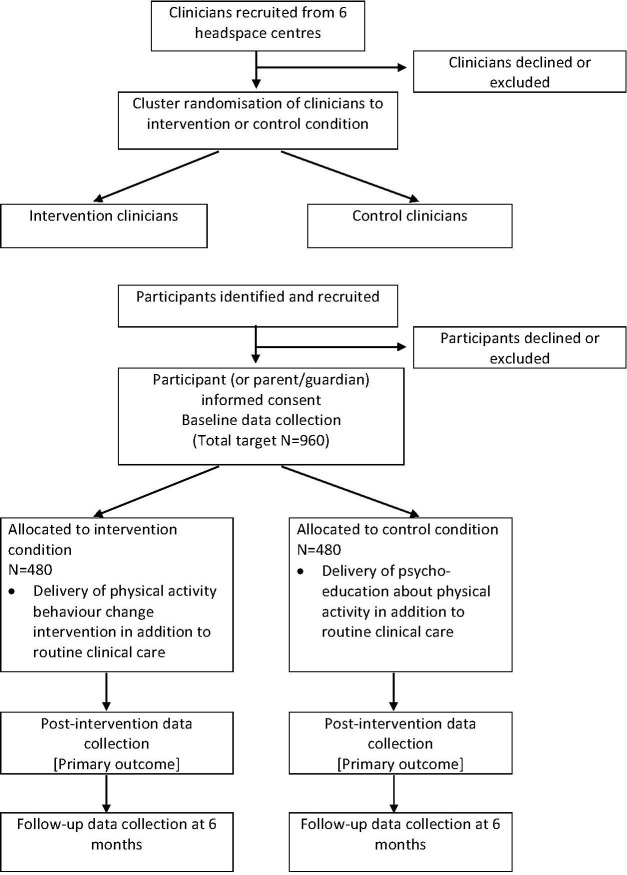

The study will use a parallel group, two-arm, cluster randomised controlled trial (C-RCT) design to test the effect of the physical activity intervention compared with psychoeducation, in addition to routine clinical care, with randomisation occurring at the clinician level (see figure 1). Randomising clinicians will reduce the contamination associated with clinicians concurrently managing intervention and control participants, as would occur in a standard patient randomised trial.30 Assessment time points will be at baseline, intervention end-point (primary outcome) and 6 months (follow-up). The trial has well-defined objectives and protocols addressing Good Clinical Practice (GCP)31 and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines.32 Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination of our research.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of clinician and participant recruitment and study timeline.

Setting headspace centres are accessible, community-based mental health services that support young people aged 12–25 years, funded by the Australian federal government.33 Services are delivered in a youth-friendly environment staffed by a range of service providers, including general practitioners, psychologists, psychiatrists, youth workers, mental health nurses and other allied health professionals. headspace centres assess approximately 850 new patients per year, 40% presenting with depression.34 A subset of approximately 6 of the more than 100 headspace centres will be involved in this study.

Participant and recruitment procedures

Clinicians

All allied health professionals, including psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists (‘clinicians’), who provide mental health treatments to young people in the participating headspace centres will be invited to participate in the study and will be randomised to deliver either the intervention group (physical activity behaviour change) or the control group (psychoeducation), in addition to routine clinical care. Clinicians in predominantly intake and assessment roles will not be included.

Participants

All help-seeking young people aged 12–25 years who present to participating headspace centres will be screened for eligibility. We aim to recruit a total of 960 participants. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants; those aged between 15 years and 18 years will be assessed for mature minor capacity35 during the intake assessment procedure at entry to the service and, if they meet this threshold, will be able to make the decision whether or not to consent to participate. Those aged 12–14 years can provide assent to participate but will also require parental/legal guardian consent. After obtaining informed consent, participants will be screened by research assistants who will: (A) assess the eligibility of the young person and (B) collect outcome data (interview and self-report) at baseline, post-treatment and 6-month follow-up assessments.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Inclusion, exclusion and discontinuation criteria

Inclusion criteria

(1) Meeting the requirements for a Mental Health Treatment Plan to access up to 10 sessions of psychological treatment under the Medicare Benefits Scheme Better Access programme per annum36; and (2) a Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Adolescent (17 item) - Clinician Rated (QIDS-A17-C)37 score of 11 or greater, indicating depression levels of moderate or above.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Presence of a psychotic disorder or eating disorder during the intake assessment on first presentation to the headspace centre38; (2) current physical activity meeting the Australian Government Guidelines (ie, for those under 18 years, 60 min of moderate to vigorous activity every day; for those over 18 years, 30 min of moderate activity at least five times for week)39 40; (3) physical illness that contraindicates participation in physical activity; (4) organic mental disorder; and (5) intellectual disability/cognitive impairment that precludes providing informed consent, as assessed by the headspace intake and access team members and the study’s research assistants and referred for review to the study site’s principal investigator or clinical review team. Any young person reporting a prior history of physical illness that might impede their ability to take part in physical activity will be required to receive medical clearance from a general practitioner in order to participate in the trial.

Discontinuation criteria

(1) Incidence of a psychotic disorder or eating disorder meeting diagnostic threshold or (2) physical illness that contraindicates participation in physical activity, as assessed by the treating clinicians during the course of the intervention. Discontinuation from the active or control interventions can be at the request of the participant or if any changes in the participant’s presentation warrants a referral to another service, as determined by their treating clinician or clinical review team. These participants will discontinue their assigned intervention but will remain involved in the postintervention assessment.

Interventions

The interventions will be integrated into routine clinical care and delivered by a headspace clinician, which may also include probationary psychologists (graduate trainees) on clinical placement. The current funding rules of the Medicare Benefits Schedule allow for six sessions of psychological treatment (plus an additional four if clinically warranted) per calendar year. We anticipate that the interventions (both physical activity and control) will be delivered in an average of four treatment sessions across approximately 4–6 weeks, consistent with the average national attendance rates to headspace centres.41 The intervention will be capped at a maximum of 10 sessions. The active and control interventions have been described to meet the Template for Intervention Description and Replication standards.42 At the first treatment session, participants will be provided with relevant materials and resources according to the treatment condition to which their treating clinician has been assigned.

Physical activity intervention

Participants who receive treatment from a clinician who has been allocated to this group will receive a manualised integrated physical activity behaviour change intervention, as per the training delivered to the clinicians, within their psychological treatment sessions. Treatment sessions will be delivered face to face and onsite at each participating headspace centre. The IMPACT treatment manual includes evidence-based behaviour change techniques, targeting self-regulation (planning and organising), motivation, enjoyment and tailoring for individual needs.43 44 Participants will be encouraged to set short-term and longer term specific and measureable goals; monitor progress towards these goals; discuss the benefits of physical activity; consider factors that may facilitate their participation (eg, enlisting support from others and choosing physical activities that are enjoyable)44 45; and identify potential barriers and strategies for overcoming these barriers. Clinicians will review weekly goals, participants’ self-monitoring of mood preactivity and postactivity, addressing barriers and enhancing individual facilitators, reinforcing achievements and revising physical activity plans in each weekly session of psychological treatment to facilitate an increase in engagement in physical activity.46 The intervention is designed to be delivered within 15–20 min to the initial session, with 5–10 min duration in subsequent sessions. Given the real-world nature of the intervention context, it is not possible to define the frequency of sessions or duration of the intervention period a priori, due to variation in each of the study sites in terms of allocation to clinicians, managing service demands and appointment scheduling.

Participants will receive verbal and written information about the relationship between depressive symptoms and exercise47; access to online resources providing advice and instructions on physical activities; minimal equipment (resistance band for resistance activity and skipping rope for cardiovascular physical activity); written worksheets and resources to enhance motivation, address barriers and provide physical activity suggestions, including the current Australian national physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines48 49; and a weekly planner to discuss and plan for how and when the physical activity can be completed and any memory aids that could be used to aid in completion of this (including mobile technology applications (‘apps’)).

Psychoeducation intervention

Participants who receive treatment from a clinician who has been allocated to this group will be provided with the same psychoeducation about the relationship between depressive symptoms and physical activity as the intervention group, within the first treatment session only. Treatment sessions will be delivered face to face and onsite at each participating headspace centre. The inclusion of the control group intervention is to examine whether the provision of information about physical activity for mental health and minimal resources is sufficient for participants to increase their current levels of physical activity. This will include providing the same verbal and written information about the relationship between depressive symptoms and exercise47; minimal equipment (resistance band for resistance activity and skipping rope for cardiovascular physical activity); and physical activity suggestions, including the current Australian national physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines,48 49 that will be provided to the intervention group. The importance of physical activity for depression will be addressed in the first session but will not be included in ongoing treatment.

Study hypotheses

Primary: that the physical activity intervention will lead to greater reductions in depressive symptoms compared psychoeducation on physical activity, in addition to routine clinical care,

Secondary: (A) that the physical activity intervention will lead to greater reductions in anxiety symptoms and greater improvements in functioning, when compared with the control condition; and (B) that changes in depressive symptoms will be mediated by increases in physical activity.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome will be level of depression symptoms postintervention and at 6-month follow-up, measured by the QIDS-A17-C.37

Secondary outcomes

Physical activity (mediator): levels of physical activity measured by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire50 and an electronic accelerometer device worn for 5–7 days.

Mental health and substance use: anxiety symptoms measured by the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale51; depression module from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV52; and substance use measured by the WHO Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test.

Anthropomorphic and lifestyle variables: height, weight and hip and waist measurements to determine body mass index and hip/waist ratio; Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index53; and the Simple Dietary Questionnaire.

Functioning: Social and Occupational Functional Assessment Scale54; and Australian Quality of Life Scale for adolescents55 to facilitate future cost utility and other economic analyses.

Variables that will be the subject of subsequent exploratory analyses include: self-efficacy measured by General Self Efficacy Scale56 and Barriers Self-Efficacy Scale (physical activity)57; Perceived Social Support Scale; Positive and Negative Affect Schedule58 Cognitive and Behavioural Therapy Skills Questionnaire59; Behavioural Activation for Depression Scale60; Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale61; and Working Alliance Inventory (therapeutic alliance)62; and the Trail Making Test A & B63 64 to assess attention, processing speed and mental flexibility.

Assessments and measures will be conducted as per the assessment schedule: (1) screening for eligibility; and (2) baseline, postintervention (end-point) and 6-month follow-up assessments. Data from participating young people will be entered into a project-specific secure online database at all assessment time-points, using a reversible process in which the identifiers are removed and replaced by a code.

Process and implementation measures

Training

All participating clinicians will be trained in GCP and IMPACT study procedures, delivered in a 1.5-hour session in face-to-face format. Additionally, all participating clinicians will participate in a further 30 min training session on how to deliver the psychoeducation on physical activity and share resources with participants in the study. Following this, all clinicians who are randomised to the physical activity intervention group will take part in an additional 60 min training session to integrate the IMPACT intervention into routine clinical care. For the intervention group, skills, knowledge and attitudes will be assessed before and after the training session, measured by the Theoretical Domains Framework questionnaire.65

The face-to-face training will be supported by additional online resources using a learning management system that will host an electronic version of the intervention manual, project resources, training videos and case vignettes. The training will incorporate practice recommendations for delivering physical activity behaviour change interventions for mental health, including: (A) creating individual training plans to increase adherence and aim to increase physical activity levels and decrease sedentary behaviours, (B) integrating the physical activity intervention into routine psychoeducation and psychotherapy; and (C) incorporating evidence-based behaviour change techniques, targeting self-regulation (planning and organising), motivation, enjoyment and tailoring for individual needs.43 44 Clinicians will be provided with a comprehensive IMPACT treatment manual66 and the resources required to deliver the intervention (handouts, worksheets and access to online materials). Clinicians in the control condition will not have access to the online support materials.

Fidelity

Fidelity will be assessed using a brief checklist to be completed by clinicians after each session to estimate time spent on the intervention and the type of psychological treatment that was delivered as part of routine care (eg, CBT and interpersonal therapy). Fidelity will also be assessed by audio recording of all treatment sessions, with a random subset of 10% of the recordings to be coded by an independent rater for adherence to the treatment manual and to discriminate between the intervention and control conditions. Fidelity will be maintained by offering quarterly online group peer supervision sessions for the clinicians in the intervention group to allow group discussion and case presentations, in addition to the face-to-face training at the commencement of the trial. Less frequent peer supervision (approximately every 6 months) will be offered to the control group clinicians. Fidelity of the intervention will also be assessed using a checklist of components of the active and control conditions collected from participants at the postintervention assessment. In addition, at the end of the intervention period, a subgroup of physical activity intervention group clinicians and young people will be invited to participate in semistructured interviews to explore their experiences of delivering and receiving the intervention, respectively.

Randomisation and allocation to treatment

Clinicians will be allocated to the intervention and control groups using a minimisation procedure commencing with random assignment.67 The procedure was devised by the study statistician (AM) and will be carried out by an independent researcher, following the ICH Guideline,68 to ensure allocation concealment. Minimisation factors to be incorporated are gender of clinician (two-level factor: male/female), background training of clinician (two-level factor: psychologist/non-psychologist) and headspace centre, to ensure equal numbers in each intervention at each site (six centres). Participants will be stratified by age (≤17 and 18+ years), gender (male/female) and QIDS-A17-C score (≤15 and 16+). Participants will be assigned to a clinician based on a randomised list. Due to the nature of the intervention, it will not be possible to blind the clinicians and participants; however, all preintervention, postintervention and follow-up assessments will be conducted by research assistants blinded to treatment allocation. Investigators not involved in the delivery of the intervention and the trial statistician will be blind to group allocation until the analysis is completed.

Statistical analysis

Analysis plan

Primary quantitative analyses will be undertaken on an intent-to-treat basis, including all participants as randomised, regardless of treatment received or withdrawal from the study. Linear mixed models will be used to analyse change in the primary outcome measure (QIDS-A17-C). Models will include a random ‘clinician’ factor. Correlation of repeated outcome measures will be accommodated using an unstructured variance–covariance matrix. An a priori planned comparison of change from baseline to the postintervention assessment will be used to test the primary hypothesis. Comparison of change from baseline to follow-up between arms will be undertaken as a secondary outcome analysis. Factors used in assignment by minimisation (clinician gender, discipline and headspace centre) will be introduced in models as covariates and retained if significant. Variables associated with participant missingness or found to be substantially inbalanced between groups will be included in models on an exploratory basis.69

Mathematical transformation or categorisation of raw scores will be undertaken to meet distributional assumptions and address any violation of assumptions required in mixed models. When transformations have been undertaken to better meet distribution assumptions, models using the transformed data will be considered the main test of the primary hypotheses. Mixed models use all available data and do not involve any substitution of missing values with supposed or estimated values. The assumptions underlying mixed modelling allow ‘missingness’ to be related to observed variables in the analysis but not to unobserved values (termed ‘missing at random’).70

Similar analyses of scaled secondary measures will assess differential change due to intervention arm. For dichotomous outcomes such as diagnoses and ordinal or count outcomes, comparable generalised mixed modelling approach will be used. Relative and reduction in risk of depression based on SCID diagnostic status will be estimated at the trial end-point and follow-up. Numbers needed to treat will be derived from these values. All analyses will use two-sided tests, with an alpha value set at 0.05. In the event of substantial missingness, sensitivity analyses based on identified clinically plausible mechanisms may be undertaken to determine the robustness of findings.

Qualitative analyses of the semistructured interviews included within the process and implementation measures will be undertaken on audio-recorded interviews that will be transcribed verbatim, with data analysed using thematic analysis.71

Power analysis

Calculations of required sample size were based on detecting a postintervention effect size of 0.34, which is at the lower boundary of utility and also reflects the adjunctive status of the intervention. Power was set at 0.90, alpha=0.05 (two tailed) and correlation of 0.5 assumed between pretreatment and post-treatment scores. To allow for possible clustering effects (participants with the same therapist having characteristics and outcomes more alike than between therapists), a design effect72 was calculated assuming an intraclass correlation (ICC) of 0.05 and the number of clients per therapist up to 24. The estimate of the ICC is at the upper range of therapist effects and is conservative given the prescribed, manualised nature of the intervention. It is anticipated that 6–8 clinicians per headspace centre will be involved in the study. The resultant design effect of 2.15 reflects the possible non-independence of cluster-sampled participants and was used to inflate the calculated sample size, which assumes independence. The estimated required sample size was 784. To accommodate a potential attrition/withdrawal rate of up to 20%, the target sample size was set at 960 or 480 participants per condition.

Safety procedures and oversight

Each participating headspace centre will have a principal site investigator and will also be required to nominate a lead clinician who will be responsible for the oversight of participant safety during the course of the trial. Withdrawal from the study can be at the request of the participant or if the participant meets discontinuation criteria. Once withdrawn, the young person will be reviewed using the headspace centre’s standard clinical review procedure and either maintained in the headspace centre or referred to other services as necessary. Any adverse incident, any serious or unanticipated adverse effects of the research on study participants, and unforeseen events that might affect continued ethical acceptability of the project, will be captured and reported until resolution, stabilisation or the participant is lost to follow-up, unless the condition is unlikely to resolve as per the opinion of the medical practitioner appointed by the study sponsor to monitor adverse incidents. In the event of an adverse incident or unexpected outcome, the allied health professional or research personnel will report to the study sponsor, Orygen. If necessary, a decision will be made as to whether to withdraw or suspend participation. The study sponsor will conduct annual centralised monitoring visits of the study sites.

Ethics and dissemination

Revisions to the study protocol have been enacted following approval received from the HREC (latest version: Protocol Version 9, 1 April 2019), and these revisions have been reported in the trial registry by the study’s clinical trial managers (CM and VR). Trial findings will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at conferences. Key messages will also be disseminated by the youth mental health services organisation (headspace National Youth Mental Health Foundation).

Discussion

Depressive disorders are highly prevalent and are the leading cause of disability in young people worldwide. If effective, the physical activity intervention tested in this C-RCT has the potential to improve the immediate outcomes for young people with depression by providing an additive treatment effect in conjunction with routine clinical care. Additional benefits may include improvements in social and vocational functioning, thereby reducing the likelihood of longer term damage in these domains.

The IMPACT intervention is easily scalable. As it is set within the national network of headspace centres, this will increase the likelihood that any benefits are translated into routine clinical practice for the many thousands of young people who access headspace services per annum. There is also potential to adapt the intervention for other service delivery models (eg, primary care and tertiary mental health services) nationally and internationally—including in regional and remote areas—which may be of interest to policy makers and those funding mental health programmes or services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge the support from the headspace National Office and the headspace centres involved as study sites (headspace Hawthorn (Victoria), headspace Ipswich and Townsville (Queensland), headspace Coffs Harbour and Bathurst (New South Wales) and headspace Edinburgh North (South Australia)). The authors would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Victoria Rayner in supporting the management of this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: AGP led the development of this manuscript. AGP, DJR, AM, RP, MA-J, ARY, PM, SH and AJ secured the funding for the project and, together with author CM, devised the research design and measures. AGP, CM, DR, RP, MA-J, ARY, PM, SH and AJ were involved in devising the intervention content and intervention implementation strategies, which were based on those established and previously operated by AGP, RP, ARY, PM, SH and AJ. AM was primarily responsible for the sample size and power calculations and development of proposed statistical analyses. AGP wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant (GNT1063033) titled ‘Physical activity for young people with depression: A cluster randomised controlled trial to test the effectiveness of incorporating a brief intervention into routine clinical care’. AJ received salary support from an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (APP1059785). AY received salary support from an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship (APP1136829). Study sponsor: the study is sponsored by the Sponsor Operations Department, Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health. Contact details: 35 Poplar Road, Parkville, Victoria, Australia 3052. A risk assessment of the study conducted by the study sponsor determined that a data monitoring committee was not needed due to the low-risk nature of the intervention.

Disclaimer: The funding body has had no role in the study design or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The study sponsor has had no role in the study design or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Data availability statement: There are no data in this work.

References

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics Mental health of young people, Australia, 2007. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gore FM, Bloem PJN, Patton GC, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2011;377:2093–102. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clayborne ZM, Varin M, Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;58:72–9. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, et al. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:915–23. 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGorry PD, Hickie IB, Yung AR, et al. Clinical staging of psychiatric disorders: a heuristic framework for choosing earlier, safer and more effective interventions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:616–22. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01860.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Nice guideline. depression in children and young people: identification and management. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Cox GR, et al. Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12 10.1002/14651858.CD004851.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Locher C, Koechlin H, Zion SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and placebo for common psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:1011–20. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, et al. What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: a multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am Psychol 2017;72:79–117. 10.1037/a0040360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:807–20. 10.1001/jama.292.7.807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dunn AL, Jewell JS. The effect of exercise on mental health. Curr Sports Med Rep 2010;9:202–7. 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181e7d9af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bélair M-A, Kohen DE, Kingsbury M, et al. Relationship between leisure time physical activity, sedentary behaviour and symptoms of depression and anxiety: evidence from a population-based sample of Canadian adolescents. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021119–8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ströhle A. Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. J Neural Transm 2009;116:777–84. 10.1007/s00702-008-0092-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet 2012;380:219–29. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Mental Health Commission A contributing life, the 2012 national report card on mental health and suicide prevention. Sydney: NHMRC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, et al. The Lancet psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:675–712. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mangerud WL, Bjerkeset O, Lydersen S, et al. Physical activity in adolescents with psychiatric disorders and in the general population. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2014;8:2–10. 10.1186/1753-2000-8-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chu I-H, Buckworth J, Kirby TE, et al. Effect of exercise intensity on depressive symptoms in women. Ment Health Phys Act 2009;2:37–43. 10.1016/j.mhpa.2009.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mead GE, Morley W, Campbell P, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tylee A, Haller DM, Graham T, et al. Youth-friendly primary-care services: how are we doing and what more needs to be done? The Lancet 2007;369:1565–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60371-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res 2016;77:42–51. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Firth J, et al. Physical activity and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2018;225:438–48. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Biddle SJH, Asare M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:886–95. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carter T, Morres ID, Meade O, et al. The effect of exercise on depressive symptoms in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016;55:580–90. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Parker AG, Hetrick SE, Jorm AF, et al. The effectiveness of simple psychological and physical activity interventions for high prevalence mental health problems in young people: a factorial randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2016;196:200–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bailey AP, Hetrick SE, Rosenbaum S, et al. Treating depression with physical activity in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychol Med 2018;48:1068–83. 10.1017/S0033291717002653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Callaghan P. Exercise: a neglected intervention in mental health care? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2004;11:476–83. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00751.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Stanton R, et al. Implementing evidence-based physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: an Australian perspective. Australas Psychiatry 2016;24:49–54. 10.1177/1039856215590252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weijer C, Grimshaw JM, Taljaard M, et al. Ethical issues posed by cluster randomized trials in health research. Trials 2011;12 10.1186/1745-6215-12-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Therapeutic Goods Adminstration The Australian clinical trial Handbook: a simple, practical guide to international standards of good clinical practice (GCP) in the Australian context. Canberra DoHa: Ageing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rickwood D, Paraskakis M, Quin D, et al. Australia's innovation in youth mental health care: the headspace centre model. Early Interv Psychiatry 2019;13:159–66. 10.1111/eip.12740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rickwood DJ, Mazzer KR, Telford NR, et al. Changes in psychological distress and psychosocial functioning in young people visiting headspace centres for mental health problems. Med J Aust 2015;202:537–42. 10.5694/mja14.01696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bird S. Consent to medical treatment: the mature minor. Aust Fam Physician 2011;40:159–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Department of Health Better access to psychiatrists, PSYCHOLOGISTS and general practitioners through the Mbs (better access) initiative, 2019. Available: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-ba [Accessed 01 Aug 2019].

- 37. Haley CL, Kennard BD, Bernstein IH, et al. Improving depressive symptom measurement in adolescents: a psychometric evaluation of the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology, adolescent version (QIDS-A17). Dallas: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Parker A, Hetrick S, Purcell R. Psychosocial assessment of young people - refining and evaluating a youth friendly assessment interview. Aust Fam Physician 2010;39:585–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Department of Health and Ageing Australia’s Physical Activity Recommendations for 12-18 year olds. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Department of Health and Ageing National physical activity guidelines for adults. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rickwood DJ, Telford NR, Mazzer KR, et al. The services provided to young people through the headspace centres across Australia. Med J Aust 2015;202:533–6. 10.5694/mja14.01695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:1687 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ekkekakis P, Murri MB. Exercise as antidepressant treatment: time for the transition from trials to clinic? Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2017;49:A1–5. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lederman O, Suetani S, Stanton R, et al. Embedding exercise interventions as routine mental health care: implementation strategies in residential, inpatient and community settings. Australas Psychiatry 2017;25:451–5. 10.1177/1039856217711054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ekkekakis P. People have feelings! exercise psychology in paradigmatic transition. Curr Opin Psychol 2017;16:84–8. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sebire SJ, Jago R, Banfield K, et al. Results of a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial of a peer-led school-based intervention to increase the physical activity of adolescent girls (PLAN-A). International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2018;15:1–13. 10.1186/s12966-018-0682-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. beyondblue Getting active to beat depression: fact sheet. Ybblue (youth program of beyondblue, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Department of Health Australia's physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines: young people (13-17 years). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Department of Health Australia's physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines: adults (18-64 years. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Booth M. Assessment of physical activity: an international perspective. Res Q Exerc Sport 2000;71 Suppl 2:114–20. 10.1080/02701367.2000.11082794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Norman SB, Cissell SH, Means-Christensen AJ, et al. Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Depress Anxiety 2006;23:245–9. 10.1002/da.20182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:1148–56. 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Moodie M, Richardson J, Rankin B, et al. Predicting time trade-off health state valuations of adolescents in four Pacific countries using the AQoL-6D instrument. Melbourne: Centre for Health Economics, Monash University, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale : Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Windsor, UK: NFER-Nelson, 1995: 35–7. [Google Scholar]

- 57. McAuley E. The role of efficacy cognitions in the prediction of exercise behavior in middle-aged adults. J Behav Med 1992;15:65–88. 10.1007/BF00848378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;54:1063–70. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jacob KL, Christopher MS, Neuhaus EC. Development and validation of the cognitive-behavioral therapy skills questionnaire. Behav Modif 2011;35:595–618. 10.1177/0145445511419254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kanter JW, Rusch LC, Busch AM, et al. Validation of the behavioral activation for depression scale (bads) in a community sample with elevated depressive symptoms. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2009;31:36–42. 10.1007/s10862-008-9088-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:382–9. 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Munder T, Wilmers F, Leonhart R, et al. Working alliance Inventory-Short revised (WAI-SR): psychometric properties in outpatients and inpatients. Clin Psychol Psychother 2010;17:231–9. 10.1002/cpp.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Partington JE, Leiter RG. Partington's pathway test. The Psychological Service Center Bulletin 1949;1:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Reitan RM. The relation of the TRAIL making test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol 1955;19:393–4. 10.1037/h0044509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:26–33. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Parker AG, Moller B, Baird S, et al. Behavioural exercise and lifestyle psychoeducation therapy manual: simple interventions trial: Orygen youth health research centre, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Taves DR. The use of minimization in clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2010;31:180–4. 10.1016/j.cct.2009.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lewis JA. Statistical principles for clinical trials (ICH E9): an introductory note on an international guideline. Stat Med 1999;18:1903–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Guideline on adjustment for baseline covariates in clinical trials (EMA/CHMP/295050/2013), 2015. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-adjustment-baseline-covariates-clinical-trials_en.pdf

- 70. Carpenter JR, Kenward MG. Missing data in randomised controlled trials: a practical guide. Birmingham: health technology assessment methodology programme, 2007: 199. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012;345 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.