Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between diabetes and latent tuberculosis infections (LTBI) in high TB incidence areas.

Design

Community-based comparison study.

Setting

Outpatient diabetes clinics at 4 hospitals and 13 health centres in urban and rural townships. A community-based screening programme was used to recruit non-diabetic participants.

Participants

A total of 2948 patients with diabetes aged older than 40 years were recruited, and 453 non-diabetic participants from the community were enrolled.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) and the tuberculin skin test were used to detect LTBI. The IGRA result was used as a surrogate of LTBI in logistic regression analysis.

Results

Diabetes was significantly associated with LTBI (adjusted OR (aOR)=1.59; 95% CI 1.11 to 2.28) and age correlated positively with LTBI. Many subjects with diabetes also had additional risk factors (current smokers (aOR=1.28; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.71), comorbid chronic kidney disease (aOR=1.26; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.55) and history of TB (aOR=2.08; 95% CI 1.19 to 3.63)). The presence of BCG scar was protective (aOR=0.66; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.85). Duration of diabetes and poor glycaemic control were unrelated to the risk of LTBI.

Conclusion

There was a moderately increased risk of LTBI in patients with diabetes from this high TB incidence area. This finding suggests LTBI screening for the diabetics be combined with other risk factors and comorbidities of TB to better identify high-risk groups and improve the efficacy of targeted screening for LTBI.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, latent infection, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccination, interferon-gamma release assay, tuberculin skin test

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of this study are the adoption of stringent diagnostic criteria for diabetes mellitus (DM) and comprehensiveness of information obtained from community-based programmes.

Protection of BCG vaccination, remote tuberculosis (TB) infection and other important potential confounding variables were controlled for assessing the DM-latent TB infection association.

The study limitations are the reduced sensitivity of the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube and tuberculin skin test in elderly diabetics and better general health status among the DM group.

Background

The co-occurrence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and tuberculosis (TB) cannot be overemphasised because of the high prevalence of each disease throughout the world.1 Previous studies found that DM affects TB disease presentation, leads to poor treatment outcomes and increases the risk for active TB.1 2 The recently published WHO guideline recommends screening for active TB with DM,3 but it remains elusive whether screening and treatment of latent TB infections (LTBI) should be prioritised to target individuals with DM.1 4–6

There is only limited information on the LTBI status of patients with DM. Most of antecedent-relevant studies were in low TB incidence countries7 or based on selected population by identifying DM in high-risk populations, such as TB contacts, immunocompromised patients with comorbid DM or crisis-affected people.6 The results of these studies are also inconsistent, mainly due to the different methods used to ascertain DM status (eg, self-report, medical records or laboratory testing) and differences in the control of potentially important confounders.1 5–7

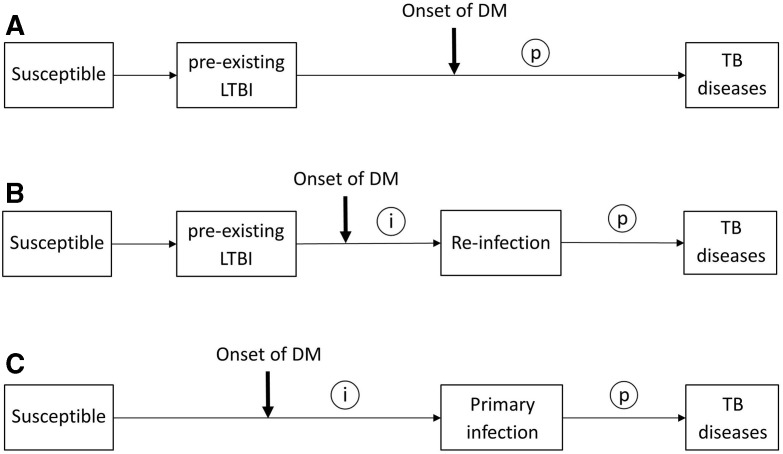

In high TB incidence areas, where most of TB infection occurred at young age before the onset of DM,8 the temporal relationship between DM and TB infection is different from that in low-incidence areas (figure 1A,B and C).6 This temporal characteristic may lead to non-differential misclassification of DM-related TB infection in cross-sectional studies and therefore bias the association towards the null (figure 1A).6 It is also worth noting that BCG vaccine is widely used in high-burden TB countries for childhood immunisation against TB. Recent studies found BCG vaccine has a protective effect against TB infection in children9 and can even last into adulthood.10 Although several research have been devoted to assessment of DM-LTBI association, rather less attention has been paid to confounding from the protection conferred by BCG vaccination in settings where coverage of BCG vaccination in study subjects was high.

Figure 1.

Possible temporal relationships between the onset of DM and the occurrence of TB infection. Circled letters indicate times when DM could possibly affect the pathogenesis of TB (i, increased susceptibility to TB infection; p, accelerated progression from infection to clinical disease). (A) Onset of DM with a pre-existing latent TB infection (LTBI). (B) Onset of DM with a pre-existing LTBI, but before reinfection. (C) Onset of DM before the primary TB infection. DM, diabetes mellitus; TB, tuberculosis.

In this study, using data from community-based programmes in an area with a high incidence of TB and a high coverage of BCG vaccination, we assessed the overall risk of LTBI in people with and without DM by carefully controlling for potential confounders, specifically including BCG vaccination, risk of remote TB infection, comorbidities, important lifestyle factors and DM severity.

Methods

We conducted a community-based study that comprised DM and non-DM subjects by combining two community-based programmes to investigate the effect of DM on risk of LTBI in Changhua, a county in Taiwan with a TB incidence of 58.7 per 100 000 and a BCG vaccination coverage of around 99% in 2012.11 The first programme recruited the DM group from patients registered in the Changhua Diabetes Shared Care (CHDSC) programme12 to participate in the LTBI survey. The second recruited the community comparison (CC) group from participants of a community-based LTBI screening programme.13 Due to the lack of a gold standard test for LTBI, the tuberculin skin test (TST) was used in parallel with the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

DM group

Nearly 60% of patients with DM in Changhua were enrolled in the national diabetes disease management programme (DDMP) and registered in the CHDSC.12 These enrollees were suitable to be included as the study subjects, because their DM status had been ascertained by certified physicians who provided diabetes care according to national guidelines. We prospectively invited all those registered DM cases aged older than 40 years when they presented to outpatient diabetes clinics of the Changhua Christian Healthcare System (CCHS) or 13 nearby health centres in the surrounding townships from 1 April 2013 to 31 December 2013. CCHS comprises one medical centre and three branch hospitals, distributed evenly at different locations of the county, and covers urban and rural areas. Thus, the participants of this study were a representative sample of the total DM population.

All study subjects were screened for pulmonary TB based on respiratory symptoms and chest X-rays on entry into the study. Suspected cases submitted sputum specimens for acid-fast bacilli smears and culture. The diagnosis of TB was confirmed by chest specialists. Subjects were excluded if they had active pulmonary TB, a life expectancy of less than 2 years, metastatic cancer or organ failure (eg, severe liver disease (Child-Pugh class B or C)) except chronic renal failure. The included eligible DM cases then received a TST and IGRA for detection of LTBI.

Community comparison group

The Changhua Community-based Integrated Screening (CHCIS) programme, which began in 2005, screens for neoplastic and non-neoplastic diseases (including DM and pulmonary TB).13 The method used to screen for pulmonary TB was the same as that used in the DM group. We invited all consecutive attendees of the CHCIS programme within the major catchment area of the CCHS to participate in LTBI screening on 1 May 2011. Participants with known DM or newly screened DM (ie, fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL) were excluded.

Tests for LTBI

Venous blood was collected for the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT; Cellestis, Carnegie, Australia), which was performed in two stages, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cut-off for a positive result was 0.35 IU/mL. The reactions of a nil control and a mitogen control were within the range provided by the manufacturer. After collection of blood samples for QFT-GIT, trained nurses administered the TST using 2 tuberculin units of purified protein derivative RT23 (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) by the Mantoux method, and inspected the presence of BCG scars. Tuberculin indurations were measured 48–72 hours after injection using the palpation method, and a diameter of 10 mm or more was defined as positive. All TST procedures followed the national guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control of Taiwan.14

Data collection

We examined the DDMP database, and abstracted demographic data and information on DM care in the same year when each subject was recruited. This included duration of DM, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), blood pressure, lipid profile, renal function and other related cardiovascular disease risk factors. We also linked individual data with the TB registry at the local health authority to assess whether each study subject had a history of TB or contact with TB.

Statistical analysis

Although both TST and IGRA indicate a cellular immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and are useful for the diagnosis of LTBI, the two tests identified different population with distinct immunological processes.15 Substantial discordance of TST and IGRA has been found in previous studies.15 16 Nevertheless, IGRA has a dose–response relationship with recent TB exposure and it wanes rapidly.15 16 It may be better than TST at detecting recent rather than remote TB infection. Thus, we used the result of the QFT-GIT as a surrogate of LTBI status to estimate univariate ORs and 95% CIs using a logistic regression model. Variables that met p values less than 0.2 at univariable analysis were retained for the multivariable model, which also incorporated standard sociodemographic variables such as age and gender. The multivariable model was fitted to generate adjusted ORs (aOR) of the association between LTBI and DM by comparing the DM group with the CC group and adjusting for other independent variables, including age, gender, BCG scar, smoking, history of TB, contact with TB and comorbid chronic kidney disease (CKD), and so on.

Since tuberculin reactivity was known to represent the cumulative effect of previous TB infection, we further included the TST results in the models in attempt to control the confounding of remote TB infection (ie, TB infection acquired at young age before the onset of DM, figure 1A). All analyses were conducted using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in this study. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants.

Results

Characteristics of participants

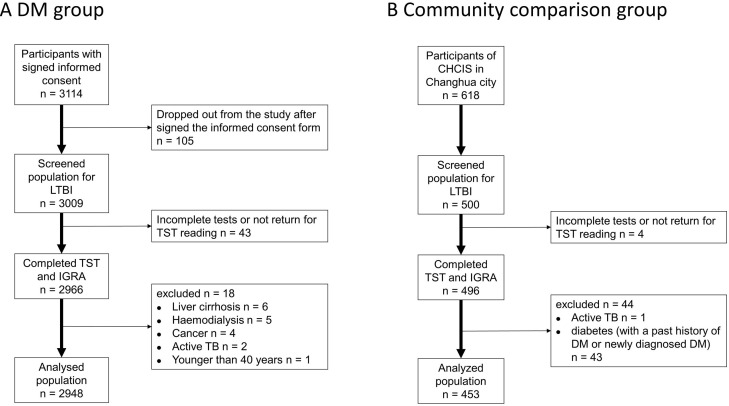

We ultimately enrolled 2948 patients in the DM group and 453 non-DM subjects in CC group, and included all of these individuals in the final analysis (figure 2). The mean duration of DM in the DM group was 9.0 years (SD=6.6) and nearly half of these patients achieved good glycaemic control (ie, HbA1c <7%) (table 1). The DM group had a greater mean age, higher percentages of males and smokers, greater prevalences of obesity, CKD and history of TB. The DM group also had a greater prevalence of tuberculin reactivity (≥15 mm) and of QFT-GIT positivity, and a higher proportion of indeterminate results (table 1).

Figure 2.

Patient selection and enrolment in the DM group (A) and the community comparison (CC) group (B). CHCIS, Changhua Community-based Integrated Screening programme; DM, diabetes mellitus; IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; LTBI, latent tuberculosis infection; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the DM group and the community comparison (CC) group

| DM group (n=2948) |

CC group (n=453) |

P value | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 61.5 (9.3) | 51.3 (10.5) | < 0.001 |

| <50 | 304 (10.3%) | 209(46.1%) | |

| 50–59 | 918 (31.1%) | 137 (30.2%) | < 0.001 |

| 60–69 | 1123 (38.1%) | 91 (20.1%) | |

| ≥70 | 603 (20.5%) | 16 (3.5%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1468 (49.8%) | 109 (24.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 1480 (50.2%) | 344 (75.9%) | |

| History of TB | |||

| Yes | 61 (2.1%) | 4 (0.9%) | 0.0852 |

| No | 2887 (97.9%) | 449 (99.1%) | |

| History of contact with TB | |||

| Yes | 115 (3.9%) | 65 (14.3%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 2283 (77.4%) | 388 (85.7%) | |

| Unknown | 550 (18.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| BCG scar | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 2436 (82.6%) | 440 (97.1%) | |

| 1 scar | 1481 (50.2%) | ||

| 2 scars | 934 (31.7%) | ||

| ≥2 scars | 21 (0.7%) | ||

| No | 502 (17.0%) | 13 (2.9%) |

|

| Unknown | 10 (0.3%) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 50 (1.7%) | 7 (1.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 1175 (39.9%) | 274 (60.5%) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 1265 (42.9%) | 149 (32.9%) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 458 (15.5%) | 23 (5.1%) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 433 (14.7%) | 31 (6.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Quit | 434 (14.7%) | 34 (7.5%) | |

| Never | 2081 (70.6%) | 388 (85.7%) | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | |||

| <150 | 1962 (66.6%) | 371 (81.9%) | < 0.001 |

| ≥150 | 986 (33.4%) | 82 (18.1%) | |

| HDL-C* | |||

| Low | 1336 (45.3%) | 299 (66%) | < 0.001 |

| Ideal | 1612 (54.7%) | 154 (34%) | |

| CKD† | |||

| Yes | 948 (32.2%) | 57 (12.6%) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1941 (65.8%) | 375 (82.8%) | |

| Unknown | 59 (2.0%) | 21 (4.6%) | |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9 (6.6) | ||

| ≤5 | 1077 (36.5%) | ||

| >5 | 1871 (63.5%) | ||

| HbA1c | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (1.5) | ||

| <7% | 1400 (47.5%) | ||

| ≥7% | 1548 (52.5%) | ||

| Unknown | 6 (0.2%) | ||

| TST positive (mm) | |||

| ≥5 | 2280 (77.3%) | 350 (77.3%) | 0.9895 |

| <5 | 668 (22.7%) | 103 (22.7%) | |

| ≥10 | 1665 (56.5%) | 251 (55.4%) | 0.6974 |

| <10 | 1283 (43.5%) | 202 (44.6%) | |

| ≥15 | 890 (30.2%) | 112 (24.7%) | 0.0211 |

| <15 | 2058 (69.8%) | 341 (75.3%) | |

| QFT-GIT | |||

| Positive | 623 (21.1%) | 44 (9.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Negative | 2144 (72.7%) | 406 (89.6%) | |

| Indeterminate | 181 (6.1%) | 3 (0.7%) |

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

*Low HDL-C: <40 mg/dL (males) and <50 mg/dL (females).

†CKD was assessed by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation using the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

BMI, body mass index;CKD, chronic kidney disease; DB, diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; QFT-GIT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

TST and QFT-GIT results

The presence of BCG scars had no effect on the tuberculin reactivity of the DM group (figure 3A). TST positivity decreased with age, and was higher in the DM group than the CC group, except among the elderly (60+ years). Figure 3B shows that QFT-GIT positivity of DM group was highest among those with no BCG scars, and that positivity declined dramatically in those more than 60 years old. In contrast, the rate of QFT-GIT positivity in those with BCG scars gradually increased with age. For each age group, there was an inverse correlation between the number of BCG scars and QFT-GIT positivity. Individuals in the CC group with BCG scars had the lowest QFT-GIT positivity, but elderly individuals from the CC group (age 70+) had the highest QFT-GIT positivity. Generally, the concordance between the TST and QFT-GIT was low (online supplementary table 1).

Figure 3.

Tuberculin skin test (TST) positivity (A) and interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) positivity (B) in the diabetes mellitus group (DMG) and the community comparison group (CCG) according to age and BCG scar status. A tuberculin induration size of 10 mm was used as the cut-off point for both groups. QFT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube.

bmjopen-2019-029948supp001.pdf (34.7KB, pdf)

Effect of DM and other factors on risk of LTBI

Multivariate regression analysis indicates DM significantly increased the risk of LTBI after controlling for major confounders (aOR=1.67; 95% CI 1.18 to 2.38). This risk was similar after adjustment for tuberculin reactivity (aOR=1.59; 95% CI 1.11 to 2.28). In addition, the presence of LTBIs increased with age. For age older than 70 years, TST adjustment had a marked effect and changed its aOR from 4.27 (95% CI 2.83 to 6.44) to 2.98 (95% CI 2.00 to 4.44). Other variables, such as current smoking, CKD and history of TB, were also significant risk factors for LTBI, and their effects were similar with or without adjustment for tuberculin reactivity. Notably, the presence of a BCG scar had a significantly protective effect on LTBI (aOR=0.66; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.85) (table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with LTBI by comparing the DM group with the community comparison group (n=3217)

| Variable | Crude OR (95% CI) | aOR1 (95% CI) | aOR2 (95% CI) |

| DM | 2.68 (1.94 to 3.71) | 1.67 (1.18 to 2.38) | 1.59 (1.11 to 2.28) |

| TST 10+ | 3.66 (2.99 to 4.49) | 4.56 (3.67 to 5.66) | |

| BCG scar | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.51 (0.41 to 0.63) | 0.73 (0.57 to 0.93) | 0.66 (0.51 to 0.85) |

| Age (years) | |||

| <50 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 50–59 | 1.98 (1.42 to 2.76) | 1.86 (1.30 to 2.65) | 2.12 (1.48 to 3.05) |

| 60–69 | 2.52 (1.83 to 3.49) | 2.25 (1.58 to 3.20) | 2.77 (1.93 to 3.97) |

| ≥70 | 4.07 (2.89 to 5.71) | 2.98 (2.00 to 4.44) | 4.27 (2.83 to 6.44) |

| Male | 1.41 (1.19 to 1.68) | 1.22 (0.98 to 1.52) | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.41) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Current | 1.54 (1.22 to 1.95) | 1.49 (1.13 to 1.97) | 1.28 (0.95 to 1.71) |

| Quit | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.29) | 0.87 (0.64 to 1.17) | 0.82 (0.60 to 1.11) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.56 (1.31 to 1.87) | 1.17 (0.96 to 1.42) | 1.26 (1.03 to 1.55) |

| History of TB | 2.95 (1.78 to 4.89) | 2.17 (1.28 to 3.68) | 2.08 (1.19 to 3.63) |

| TB contact | 0.75 (0.50 to 1.13) | 0.92 (0.60 to 1.40) | 0.86 (0.55 to 1.33) |

The aOR of DM has been adjusted for age, gender, smoking status, chronic kidney disease, history of TB and TB contact in this multivariable logistic regression model.

aOR, adjusted OR;aOR1, adjusted OR without adjustment of TST results; aOR2, adjusted OR with adjustment of TST results.; DM, diabetes mellitus; LTBI, latent TB infection; TB, tuberculosis; TST 10+, tuberculin skin test ≥10 mm result.

Comorbidities, such as hyperlipidaemia, hypertension and abnormal body mass index (BMI), had no significant associations with LTBI. We further investigated the effect of long-duration DM and poor glycaemic control by dividing the DM group into four subgroups according to duration of DM and HbA1c level, and then compared the risk of LTBI of these different subgroups, using the CC group as a reference. All of the DM subgroups had similar risks for LTBI. This indicates that long duration of DM and poor glycaemic control had no effect on the risk of LTBI (online supplementary table 2).

Discussion

Very few studies have examined the effect of DM on the risk of LTBI in high TB incidence areas and simultaneously taken into account confounding effects resulting from protection of BCG vaccination and remote TB infection. To our best knowledge, this is the first study of this kind. The key strengths of this study included adoption of stringent diagnostic criteria for DM and comprehensiveness of information obtained from community-based programmes, which enabled thorough adjustment for important potential confounding variables. Our multivariate analysis indicated that DM had a positive association with risk of LTBI (aOR: 1.59; 95% CI 1.11 to 2.28). This finding has profound implications.

A recent systematic review concluded the pooled OR estimate for DM on risk of LTBI was 1.18 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.30).6 Reasons for the different results from our study could be related to differences in the populations studied, methods for pooling results from distinct measurements for LTBI (ie, TST vs IGRA), ascertainment of diabetes status by self-reports or medical records and lack of control for several major confounders. By contrast, a recently published population-based study in the USA, a country where BCG is not generally recommended for use, using similar diagnostic criteria as this study, showed DM was associated with LTBI with aOR 1.5 (95% CI 1.0 to 2.2),7 very similar to our finding.

Although there is abundant evidence on the positive association of DM and active TB, it is uncertain whether DM increases the susceptibility to TB infection or accelerates the progression from infection to clinical disease (figure 1).1 5 More recent studies found DM increased the risk of active TB disease with aORs ranging from 1.3 to 2.6, or no significant effect at all.17–19 The strength of the association of DM and LTBI in our study was comparable to these estimates, and was particularly close to the results of Pealing et al; like our study, Pealing et al also examined patients with DM under chronic disease management.19 The observations above provide indirect evidence that increased susceptibility to TB infection might play a major contributory role in the occurrence of active TB in the diabetics. However, we must be cautious in this interpretation, because most new infections among LTBI subjects are attributable to reinfection in high TB incidence areas (figure 1B). In such cases, LTBI is associated with a significantly lower risk of progressive TB relative to primary infection (incidence rate ratio, 0.21).20 Consequently, the effect of DM on TB still depends on the extent to which the negative impact of DM on the immune response over-rides the presumably immunoprotective effect provided by pre-existing LTBI.

Since DM is a progressive disease, longer diabetes duration was found to be a major predictor of DM-related complications and death, independent of glycaemic control.21 An earlier study also revealed the risk of developing TB disease increased among those with increasing diabetes severity.2 Thus, in this study, we investigated the combined effect of longer duration of DM and poor glycaemic control (online supplementary table 2). We found they did not affect the risk of LTBI. While association between glycaemic control and risk of TB was not observed either in other research targeting patients with long-established DM,17 19 there have been several studies on cases of pre-diabetes or untreated early diabetes supported the hypothesis.1 5 7 Patients with diabetes with poor glycaemic control and longer disease duration tend to have a smaller social network and less contact with their family members or friends.22 23 This may reduce the opportunity of social contact with TB cases and trumped the risk for recent TB infection.

Many of the subjects with DM in the present study also smoked (14.7%), had abnormal BMIs (overweight and obese, 58.4%; underweight, 1.7%), CKD (32.2%), history of TB (2.1%) and advanced age (58.6% older than 60 years), and these may also be the risk factors for TB.24–26 We found that each factor alone had only a mild to moderate association with LTBI (table 2) after adjustment of BCG protection. However, when an individual has all of these other factors as well as DM, there may be a particularly high risk of LTBI, especially in those who are elderly. For example, male patients with DM older than 60 years who smoke have an aOR of LTBI up to 6.7 (derived by summation of the estimated regression coefficients). Conventional targeted screening for LTBI mostly focuses on host variables and the environment, such as infectiousness of index cases and contact patterns, but seldom consider the effects of multiple factors simultaneously.27 28 Our results underscore the necessity of incorporating DM, BCG, TST results, related risk factors and comorbidities to develop a composite scoring system that improves the efficacy of LTBI screening programmes.

There are some limitations in our study. First, although the in vivo TST and ex vivo IGRAs are the only two methods available for diagnosing LTBI, there is concern that immune dysfunction in DM may compromise the performance of these tests.5 Reduced sensitivity of the QFT-GIT and TST in elderly diabetics (figure 3A,B) may lead to false negatives, and therefore underestimate the effect of DM. Second, all patients with DM were enrolled from the DDMP, an intervention designed to facilitate lifestyle modification in patients with DM.12 Thus, these study subjects may have better general health status, and hence lower risk of TB infection, than patients with DM from the general population.19 Third, the differences in the characteristics of the DM group and the CC group suggested selection bias existed between the two groups. Some unmeasured confounders, such as the exposure of TB related to social environment and socioeconomic status, may have biased our estimation of effect of DM on risk of LTBI.

The comorbidity of TB and DM is due to the interaction between DM-impaired immunity and the occurrence of active TB by endogenous reactivation (figure 1A) or exogenous new or reinfection (figure 1B,C).1 5 This process is further complicated by the protection conferred from BCG vaccination, remote TB infection, social environment, the coexistence of multiple non-communicable risk factors and other related comorbidities and complications.5 26 29 We tried to control for all possible confounders, but this remains challenging due to the lack of a gold standard for diagnosis of LTBI and the presence of only limited tools to identify patients with DM who have the greatest risk of progressing to active TB. More studies are therefore required to identify the predictive value for progression to active TB based on IGRA and/or TST results in patients with DM. There is an ongoing longitudinal study of the present study cohort.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrated a 1.59-fold increased risk of LTBI in patients with DM from a geographic area that has a high incidence of TB. This finding suggests that practitioners should incorporate BCG vaccination, comorbidities and other coexisting risk factors, in addition to DM, to better identify high-risk groups and enhance the efficacy of targeted screening for LTBI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Statistics experts: Dr Chao-Chih Lai from Emergency Department, Taipei City Hospital, Ren-Ai Branch, Taiwan and Graduate Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Division Biostatistics, Taipei Taiwan; Professor Hsiu-Hsi Chen from Graduate Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Division of Biostatistics, Taipei Taiwan; Dr ChenYang Hsu from Graduate Institute of Epidemiology and Prevention Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University. The authors also express special thanks to the physician at the Changhua Health Bureau and the physician at the Department of Metabolism, Changhua Christian Hospital, for their assistance in the community-based study. This work was supported by the "Innovation and Policy Center for Population Health and Sustainable Environment (Population Health Research Center, PHRC), College of Public Health, National Taiwan University" from The Featured Areas Research Center Programme within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Footnotes

C-HL and S-TT contributed equally.

Contributors: Guarantor of integrity of the entire study: CHL, SCK, YPY, STT. Study concepts: CHL, SCK, MCH, IJS, SHL, YPY, STT. Study design: CHL, SCK, MCH, IJS, SHL, YPY, STT. Definition of intellectual content: CHL, SCK, IJS, YCC, YPY, STT. Literature research: SCK, MCH, CYC, YCC, HYD. Clinical studies: MCH, CHL, SYH, SHL, SLS, CYL, SRH, YCH, SYW, SDL, YPY, STT. Experimental studies: CHL, SCK, MCH, IJS, CYC, CYL, YCH, HYD, JSL, YPY, STT. Data acquisition: MCH, SYH, SHL, SLS, CYL, SRH, YCH, SYW, SDL. Data analysis: SCK, MCH, SYH, CYC, CYL, YCH, FCT, YPY, STT. Statistical analysis: MCH, FCT, YPY. Manuscript preparation: CHL, SCK, SHL, YPY, STT. Manuscript editing: CHL, SCK, SHL, YPY, STT. Manuscript review: CHL, MCH, SHL, YCC, YPY, STT.

Funding: This study is supported by the funding sponsorship plan of the National Health Research Institutes: 'A New Strategy for Genetics, Pathogenesis, Prevention and Treatment of Pathogens of Important Infectious Diseases in Taiwan–A study on Evolution, Toxicity and Drug Resistance of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis (IV-102-SP-08)' and 'A New Strategy for Genetics, Pathogenesis, Prevention and Treatment of Pathogens of Important Infectious Diseases in Taiwan–A Study on the Evolution of Tuberculosis Genes and Transcripts in Tuberculosis Recurrence (IV-103-SP-06, IV-104-SP-06)'; the funding sponsorship plan of Changhua Christian Hospital: 'Risk assessment of TB reactivation and efficacy of preventive therapy in latent TB infection population in Changhua county (102-CCH-PRJ-03)'.

Disclaimer: The founders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All participants provided signed informed consent before enrolment. Both studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Changhua Christian Hospital (numbers IRB:CCH-130102 and IRB:CCH-111012).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Changhua Research Alliance for Tuberculosis Elimination

References

- 1. Dooley KE, Chaisson RE. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: convergence of two epidemics. Lancet Infect Dis 2009;9:737–46. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70282-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baker MA, Lin H-H, Chang H-Y, et al. The risk of tuberculosis disease among persons with diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54::818–25. 10.1093/cid/cir939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: principles and recommendations. WHO/HTM/TB.2013.04. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization Collaborative framework for care and control of tuberculosis and diabetes, 2011. Available: http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/tb_diabetes2011/en/ [Accessed 12 Apr 2017]. [PubMed]

- 5. Restrepo BI. Diabetes and tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr 2016;4 10.1128/microbiolspec.TNMI7-0023-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee M-R, Huang Y-P, Kuo Y-T, et al. Diabetes mellitus and latent tuberculosis infection: a systematic review and Metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:719–27. 10.1093/cid/ciw836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martinez L, Zhu L, Castellanos ME, et al. Glycemic control and the prevalence of tuberculosis infection: a population-based observational study. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65:2060–8. 10.1093/cid/cix632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yeh YP, Luh DL, Chang SH, et al. Tuberculin reactivity in adults after 50 years of universal Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination in Taiwan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2005;99:509–16. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roy A, Eisenhut M, Harris RJ, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g4643 10.1136/bmj.g4643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chan P-C, Yang C-H, Chang L-Y, et al. Lower prevalence of tuberculosis infection in BCG vaccinees: a cross-sectional study in adult prison inmates. Thorax 2013;68:263–8. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control, R.O.C. (Taiwan) Taiwan tuberculosis control report 2013. Taiwan: Centers for Disease Control, Department of Health, R.O.C. (Taiwan), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yeh Y-P, Chang C-J, Hsieh M-L, et al. Overcoming disparities in diabetes care: eight years' experience changing the diabetes care system in Changhua, Taiwan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;106 Suppl 2:S314–22. 10.1016/S0168-8227(14)70736-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen TH-H, Chiu Y-H, Luh D-L, et al. Community-Based multiple screening model: design, implementation, and analysis of 42,387 participants. Cancer 2004;100:1734–43. 10.1002/cncr.20171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control, R.O.C. (Taiwan) Tuberculosis control manual, 2nd ED. Taiwan: Centers for Disease Control, Department of Health, R.O.C. (Taiwan), 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lai C-C, Hsu C-Y, Hsieh Y-C, et al. The effect of combining QuantiFERON-TB gold In-Tube test with tuberculin skin test on the detection of active tuberculosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2018;112:245–51. 10.1093/trstmh/try043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kang YA, Lee HW, Yoon HI, et al. Discrepancy between the tuberculin skin test and the whole-blood interferon gamma assay for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection in an intermediate tuberculosis-burden country. JAMA 2005;293:2756–61. 10.1001/jama.293.22.2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leegaard A, Riis A, Kornum JB, et al. Diabetes, glycemic control, and risk of tuberculosis: a population-based case-control study. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2530–5. 10.2337/dc11-0902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuo M-C, Lin S-H, Lin C-H, et al. Type 2 diabetes: an independent risk factor for tuberculosis: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS One 2013;8:e78924 10.1371/journal.pone.0078924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pealing L, Wing K, Mathur R, et al. Risk of tuberculosis in patients with diabetes: population based cohort study using the UK clinical practice research Datalink. BMC Med 2015;13:135 10.1186/s12916-015-0381-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andrews JR, Noubary F, Walensky RP, et al. Risk of progression to active tuberculosis following reinfection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54:784–91. 10.1093/cid/cir951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herrington WG, Alegre-Díaz J, Wade R, et al. Effect of diabetes duration and glycaemic control on 14-year cause-specific mortality in Mexican adults: a blood-based prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:455–63. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30050-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yokobayashi K, Kawachi I, Kondo K, et al. Association between social relationship and glycemic control among older Japanese: JAGES cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169904 10.1371/journal.pone.0169904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sparring V, Nyström L, Wahlström R, et al. Diabetes duration and health-related quality of life in individuals with onset of diabetes in the age group 15-34 years - a Swedish population-based study using EQ-5D. BMC Public Health 2013;13:377 10.1186/1471-2458-13-377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Romanowski K, Clark EG, Levin A, et al. Tuberculosis and chronic kidney disease: an emerging global syndemic. Kidney Int 2016;90:34–40. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Horsburgh CR, O'Donnell M, Chamblee S, et al. Revisiting rates of reactivation tuberculosis: a population-based approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:420–5. 10.1164/rccm.200909-1355OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dye C, Bourdin Trunz B, Lönnroth K, et al. Nutrition, diabetes and tuberculosis in the epidemiological transition. PLoS One 2011;6:e21161 10.1371/journal.pone.0021161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, et al. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2013;41:140–56. 10.1183/09031936.00070812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aissa K, Madhi F, Ronsin N, et al. Evaluation of a model for efficient screening of tuberculosis contact subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:1041–7. 10.1164/rccm.200711-1756OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Martinez N, Kornfeld H. Diabetes and immunity to tuberculosis. Eur J Immunol 2014;44:617–26. 10.1002/eji.201344301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029948supp001.pdf (34.7KB, pdf)