Abstract

Introduction

Pregnant women faced with complications of pregnancy often require long-term hospital admission for maternal and/or fetal monitoring. Antenatal admissions cause a burden to patients as well as hospital resources and costs. A telemonitoring platform connected to wireless cardiotocography (CTG) and automated blood pressure (BP) devices can be used for telemonitoring in pregnancy. Home telemonitoring might improve autonomy and reduce admissions and thus costs. The aim of this study is to compare the effects on patient safety, satisfaction and cost-effectiveness of hospital care versus telemonitoring (HOTEL) as an obstetric care strategy in high-risk pregnancies requiring daily monitoring.

Methods and analysis

The HOTEL trial is an ongoing multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial with a non-inferiority design. Eligible pregnant women are >26+0 weeks of singleton gestation requiring monitoring because of pre-eclampsia (hypertension with proteinuria), fetal growth restriction, preterm rupture of membranes without contractions, recurrent reduced fetal movements or an intrauterine fetal death in a previous pregnancy.

Randomisation takes place between traditional hospitalisation (planned n=208) versus telemonitoring (planned n=208) until delivery. Telemonitoring at home is facilitated with Sense4Baby CTG devices, Microlife BP monitor and daily telephone calls with an obstetric healthcare professional as well as weekly hospital visits.

Primary outcome is a composite of adverse perinatal outcome, defined as perinatal mortality, 5 min Apgar <7 or arterial cord blood pH <7.05, maternal morbidity (eclampsia, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome, thromboembolic event), neonatal intensive care admission and caesarean section rate. Patient satisfaction and preference of care will be assessed using validated questionnaires. We will perform an economic analysis. Outcomes will be analysed according to the intention to treat principle.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Utrecht University Medical Center and the boards of all six participating centres. Trial results will be submitted to peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

NTR6076.

Keywords: telemonitoring, preeclampsia, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, high-risk pregnancy, telemedicine, fetal monitoring, home-based care, eHealth

Strengths and limitations of this study.

An estimated 11% of all pregnant women require daily monitoring at some point during pregnancy because of complications, leading to hospital admission.

This is the first randomised trial to evaluate a digital health innovation for telemonitoring of both fetal and maternal parameters, self-recorded by the pregnant patient at home.

To minimise bias by patient selection, the randomised multicentre design increases generalisability of the study results comparing hospital admission versus telemonitoring during high-risk pregnancy.

Alongside safety reporting of perinatal outcomes, analysis of patient preferences and cost-effectiveness of both strategies will be performed.

Digital innovations need multi-faceted evaluation before widespread implementation.

Introduction

For pregnant women diagnosed with complications, increased monitoring and observation of maternal and fetal parameters is recommended.1 The aim of daily monitoring in high-risk pregnancies is to assess fetal and maternal condition using tests such as blood pressure (BP), urinary and blood analysis and cardiotocography (CTG). This increased surveillance essentially leads to antenatal hospitalisation in up to 11% of pregnancies, mostly for preterm rupture of membranes (PROM), fetal growth restriction (FGR), (gestational) diabetes mellitus, imminent preterm birth, fetal anomalies and hypertensive disorders including pre-eclampsia (PE).2–4 These admissions, often until delivery, result in dissatisfaction with the in-hospital stay, family burden and significant costs.5 6

Recent technological advancements in healthcare (eHealth) have resulted in remote monitoring platforms, mobile device-supported care, telemedicine and teleconsultation.7 eHealth has the potential to increase patient engagement and empowerment and create better access to healthcare while reducing the necessity for hospital visits or admittance.8 Pregnant women are frequent users of smartphones and internet, and therefore already equipped with the hardware to take self-measurements at home and the mind-set to communicate these digitally with their prenatal care professional.9 Telemonitoring of pregnancy is perceived to be one of the most promising answers to the possibilities of eHealth in antenatal care.

Using a validated automated BP monitoring device (Microlife WatchBP) and a wireless, portable CTG system (Sense4Baby), a telemonitoring strategy could replace hospital admission that require these types of monitoring.10 11 Measurements, self-recorded by the pregnant women at home, are saved on the included tablet in a personal profile. Using a secured Internet portal, the data are integrated in the electronic patient record system enabling access for healthcare professionals. A pilot study (n=76) using the Sense4Baby system was performed in UMC Utrecht to examine the accuracy of the tracings, the system’s usability and participants’ experiences and acceptability. Feedback and experiences from participants were positive about the used technology and no clinical relevant adverse events occurred (unpublished data, see also Patient and public involvement section).

Currently, no clinical trials have evaluated this novel strategy with telemonitoring of self-recorded data in high-risk pregnancy before. While the patient at home will take care of measurements of CTG and BP, a considerable amount of time could be saved on hospital ward or outpatient clinic for healthcare providers. Telemonitoring might therefore reduce costs and might offer a more acceptable form of pregnancy care.12 However, risks of unevaluated implementation of digital innovations include usability problems, issues regarding safety and reimbursement, and adverse effects, resulting in disappointing adoption by the end-users. Therefore, patient safety and effectiveness of telemonitoring compared with antenatal admission have yet to be examined in a prospective trial.

In the h ospital care versus telemonitoring (HOTEL) trial, a multicentre randomised controlled trial, we aim to compare hospital care to telemonitoring in high-risk pregnancy requiring daily monitoring. We will evaluate patient safety and clinical effectiveness as well as patient satisfaction and cost-effectiveness of both strategies.

Methods

Design and setting

This ongoing multicentre randomised controlled trial will be performed in six Dutch perinatal care units, including two university hospitals. The study will be open label. The trial protocol was registered in September 2016 the first inclusion took place in December 2016. Planned end date of the trial is 1 September 2020.

Patient and public involvement

Prior to the start of the trial, pregnant women were involved in study set up. A pilot study was performed to check feasibility and acceptance of telemonitoring in pregnancy (see Introduction section). In focus groups, women with either antenatal admission or participation in the telemonitoring pilot joined our focus group studies (total n=22) to report on satisfaction of antenatal care (submitted data).

Hospitalised patients recalled anxiety, boredom and concerns about privacy on ward. Their family life was disturbed because of frequent travelling of partners and worries over their other child(s). The patients in the home telemonitoring group reported that use of the monitoring devices was uncomplicated after instruction. They reported relief about sleeping at home, better food, seeing partners and first child(s) more often and good feeling of security with at-home monitoring and weekly face-to-face visits. With use of these focus group interviews, the telemonitoring strategy and study communications were improved and we developed the questionnaire that is used at the end of the study period.

Eligibility criteria

Definitions of the inclusion criteria are fully described in table 1. Eligible women must be ≥18 years old with a singleton pregnancy ≥26+0 weeks gestational age requiring hospital admittance for maternal or fetal surveillance for one (or multiple) of the following reasons: (1) PE; (2) preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM) without contractions; (3) FGR; (4) recurrent reduced fetal movements; (5) fetal anomaly requiring daily monitoring (eg, fetal gastroschisis) and (6) intrauterine fetal death in previous pregnancy.

Table 1.

Additional information on inclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Additional definitions or criteria (other than exclusion criteria) | |

| 1 | Pre-eclampsia | Defined as:

|

| 2 | Preterm rupture of membranes |

|

| 3 | FGR | Defined as:

|

| 4 | Recurrent reduced fetal movements | |

| 5 | Fetal anomaly requiring daily monitoring | |

| 6 | Intrauterine fetal death in previous pregnancy |

Exclusion criteria for participation in the study are (1) pregnancy complications requiring intravenous therapeutics or expected obstetric intervention within 48 hours; (2) current BP >160/110 mm Hg; (3) active antepartum haemorrhage or signs of placental abruption; (4) CTG registration with abnormalities indicating fetal distress or hypoxia; (5) place of residence >30 min travel distance from a hospital; (6) multiple pregnancy and (7) insufficient knowledge of Dutch or English language or impossibility to understand training or instructions of telemonitoring devices.

Recruitment and randomisation

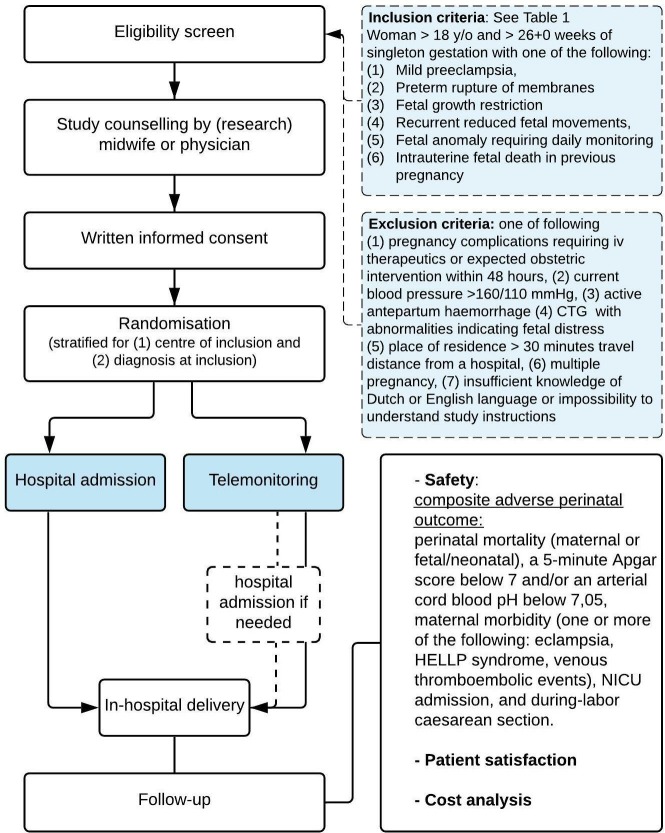

Eligible women will be approached and informed by obstetric care professionals, that is, physicians, (research) midwives or research nurses. Following counselling and sufficient time for questions, written informed consent is obtained and participants will be randomly allocated in a 50:50 ratio to either hospital admission or telemonitoring. Randomisation will be performed through a secured web-based domain (Research Online, Julius Research Support, UMC Utrecht) and will be stratified for six diagnoses for inclusion and six centres of inclusion. Block randomisation with variable block sizes is used. Cross over of trial arm is not permitted and will be considered a protocol violation. An overview of the study procedures is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study procedures.

Intervention group: telemonitoring

Prior to the start of the study, we will provide support and training of the telemonitoring strategy in each participating hospital to ensure local reliance on the technological aspects as well as task definition for the different roles. A telemonitoring team in each centre will be trained how to register, train and technically enrol new participants on the novel platform after randomisation for telemonitoring. As set in each local research protocol, responsibilities of healthcare providers are assigned to each task within the strategy: training new participants, daily monitoring of uploaded parameters, antenatal management after reviewing new results and daily telephone contact with the pregnant women at home.

After randomisation for telemonitoring, the participant will be trained in using the medical devices involved in the system (Sense4Baby CTG system and the Microlife Watch BP, both CE marked). The training will be conducted using standardised instructions of use. The instructions include a contact sheet with telephone numbers for technical or health-related questions, accessible 24/7. Each participant will receive an individual treatment plan according to national and/or local guidelines, including fetal CTG monitoring and BP measurement, both once daily. Participants at home are contacted by phone every day by the telemonitoring team, to discuss present symptoms or questions regarding the pregnancy. Possible protocolled steps in the management, after the uploaded test results are checked, are: (1) expectant management, (2) same-day clinical assessment (eg, in case of CTG abnormalities, rise in BP or symptoms) or (3) if necessary clinical admission. The participant will visit the outpatient clinic at least once a week for real-time contact and when needed ultrasound assessment, blood or urinary analysis. Should hospital admission be necessary in case of change in clinical presentation or deterioration (eg, non-reassuring CTG, hypertension, contractions, antepartum haemorrhage, signs of infection, maternal distress or technical difficulties), the patient will be monitored in the hospital as per local protocol and all data of interest during the admission will be collected. In the case, this same participant can be discharged from ward again (eg, after treatment optimisation for hypertension), she may go home with telemonitoring—as per randomisation—until delivery. All consultations in the outpatient department and possible ward admissions during pregnancy will be recorded for the study.

Control group: hospital admission

Pregnant women allocated to hospital admittance will receive standard obstetric care according to national and local guidelines and current state of the art, including daily fetal monitoring and BP measurements. All participating centres committed to following guidelines for different diagnoses and management as set by the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. A typical regime on ward includes vital parameter check (BP, temperature on indication) by obstetric nurses, daily CTG and daily rotations by a resident in obstetrics and gynaecology, supervised by an obstetrician, for interpretation of results and further management. Blood and/or urine sampling and fetal ultrasound will be performed when indicated and according to local protocol. In case the necessity of hospital admission is no longer present, the patient may be discharged and if necessary admitted to ward again, as per randomisation, not allowing cross-over to telemonitoring.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome is maternal and fetal/neonatal safety during perinatal care from study inclusion onwards by recording incidence of perinatal mortality and maternal and neonatal morbidity. The composite of adverse perinatal outcome is defined as: perinatal mortality (maternal or fetal or neonatal), a 5 min Apgar score below 7 and/or an arterial pH below 7.05, maternal morbidity (one or more of the following: eclampsia, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome, thromboembolic events), admission of the new-born to neonatal intensive care unit, and caesarean section rate. The components of the composite outcome are both chosen for either (or both) the possibility to be affected by the new intervention as well as the severity as a stand-alone adverse outcome. All components will be reported separately as a secondary outcome for interpretation of study results.

Secondary outcome will consist of patient satisfaction, quality of life and cost-effectiveness.

The satisfaction, experience and quality of life of every participating pregnant woman will be surveyed with help of the EuroQol 5D, State Trait Anxiety Inventory and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Score questionnaires.13–15 Surveys are sent by email at study start, and 1, 3, 5 weeks after randomisation and 4 weeks after delivery. With the help of focus group discussion (see under Patient involvement), we created a questionnaire which will be filled out 4 weeks after delivery.

The cost-effectiveness and budget impact analyses (CEA and BIA) will be assessed from different perspectives, that is, hospitals, health insurance companies and from the societal perspective. The BIA will follow International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research guidelines for BIA to calculate the differences in budgetary impact of telemonitoring and hospital admittance in high-risk pregnancies. For the CEA and the BIA, we will record duration of telemonitoring and duration of admittance (number of days), number of consultations and healthcare provider involved, number and length of CTG registration, number of maternal blood analyses and ultrasound assessments, emergency transport to the hospital and emergency caesarean sections. Besides this maternal use of health services, all health service use of the newborn during the follow-up period (until discharge to home) will be recorded.

Sample size

Before the start of the trial, we formed an expert panel, consisting of gynaecologists, paediatricians, methodologists and statisticians to conceive the design, content and execution of the trial. The sample size calculation is based on the assumption that the composite of adverse perinatal outcome will be equal in the telemonitoring and the hospital admittance patient groups: a non-inferiority trial. To estimate this risk for each individual component of adverse perinatal outcome in our inclusion criteria, we made use of the results of three large Dutch randomised controlled trials for patients with PPROM, FGR and PE.16–18 No data on perinatal outcome of telemonitoring in high-risk pregnancy are available to use in our sample size calculation. The incidence of this composite primary outcome in the high-risk pregnancy group is assumed to be 20% in either group. The panel made a reasoned choice about the acceptable difference in adverse perinatal outcome and feasibility of the trial, since this is the first ongoing trial of telemonitoring in complicated pregnancies. As a result, the non-inferiority margin (Δ) was defined as a 10% absolute increase or less in the telemonitoring group. With a one-sided α of 0.05, the study will achieve a power (β) of 0.80 if 200 women will be included in each trial arm. Accounting for a loss to follow-up of 4%, a total of 416 patients are needed, 208 in each arm.

The sample size was calculated for non-inferiority testing with the one-sided Score test (Farrington & Manning) using PASS software.

Data handling, analysis and result reporting

At study entry, baseline data such as patient demographics, medical and obstetric history and current pregnancy details are collected. At delivery, relevant data will be collected for the assessment of perinatal outcomes such as gestational age at birth, birth weight, condition at birth (Apgar scores, umbilical cord blood gas analysis) and neonatal admission (type of ward and number of days). Neonatal mortality and morbidity will be specified. For the mother, data will be collected on treatment for pain relief, mode of delivery and adverse outcomes (eclampsia, thromboembolic events and HELLP syndrome). Standardised online case record forms developed by Julius Centre for Research Support (UMC Utrecht) are used, including source data verification options. Missing data will be handled according to the complete-case analysis principle, based on the availability of the components needed to determine the primary endpoint.

Primary outcome

Data analyses will primarily be carried out according to the intention-to-treat principle, that is, the participants will be analysed according to their randomised allocation, regardless of the actual interventions received by the patient. Results will be reported according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines, using the extension for non-inferiority trials. If necessary, skewed continuous variables will be transformed to normality prior to the analyses. Supplementary, we will perform per protocol analyses excluding participants in whom there is a clear deviation or suboptimal execution of the intended care as prescribed by the protocol in either the admission group or the telemonitoring group. Examples include technical difficulties at home or non-compliance of study agreements, cross-over, or participants in the telemonitoring arm with (multiple) hospital admissions accounting for over half of the study period.

The primary outcome, the composite (dichotomous) endpoint of perinatal mortality and morbidity will be analysed with logistic regression analysis with the stratification factors (centre of inclusion and diagnosis of pregnancy complication) and parity as predefined covariates in the regression model. No prespecified subgroup analyses are planned.

Secondary outcomes

Each individual component outcome within the composite outcome will be reported as a single (secondary) outcome to provide further insight as the incidence and the relative importance between components of the composite outcome differ. Point estimates with CIs for the comparison of groups will be reported for these components of the composite outcome.

Patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life will be analysed with a general linear model for continuous outcomes. Comparison of questionnaires will be made for each time point, with the survey at 4 weeks postdelivery being the most important. Assumptions for general linear model (ie, normality, homoscedasticity) will be checked with residual analyses. In case of heteroscedasticity, the analyses will be repeated with robust (Huber-White) estimators for SEs. If distributional assumptions are violated, first a log transformation of the outcome will be analysed. If this transformation does not result in a valid regression analysis, intervention effects will be evaluated with a Mann-Whitney test without any corrections.

Time to delivery with account for different durations of gestation at study entry, will be evaluated with Cox regression with control of the stratification factors and parity as a predefined covariate.

For the CEA, all healthcare resources use will be transformed into cost estimates, by multiplying number of units of healthcare use, that is, number of days in hospital, number of laboratory tests and other diagnostic tests with standard unit prices as provided by the Dutch guideline for costing research in health economic evaluation studies (National Health Care Institute, Zorginstituut Nederland, 2016). For medical costs, the process of care is divided into three cost stages (antenatal stage, delivery/childbirth and postnatal stage). Cost differences between the two treatment arms will be related to effect differences (primary outcome) between the treatment arms (if any). If non-inferiority of telemonitoring is confirmed, cost differences between the two treatment arms will be analysed (cost-minimisation analysis). The CEA will be performed from both the healthcare perspective and the societal perspective.

Study monitoring and safety

To monitor the conduct of the trial and safeguard the interest of participants, an independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) will be established, including a professor of biostatistics, an obstetrician and a neonatologist. A study monitor will periodically visit participating centres, assessing quality of data and auditing trial conduct. All serious adverse events, reported by either participant or local clinician, will be recorded, and reported to the accredited ethics committee and the DSMB following international GCP guidelines. Trial data will be analysed and stored in the UMC Utrecht (study sponsor). No formal interim analysis of efficacy outcome is planned.

Ethics and dissemination

Changes to the study protocol are documented in amendments and submitted for approval to the MREC. After completion of the trial, the principal investigator will report on the results of the main study and submit a manuscript to a peer-reviewed medical journal. Supplementary analyses will be reported separately.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JFMvdH, AF and MNB contributed to study concept, trial design and study protocol. JFMvdH, AF, MNB, WG, JMDH-J, KLD, DPvdH and LS contributed to the acquisition of data. JFMvdH, AF and MNB drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. AF and MNB performed study supervision. All authors edited the manuscript and read and approved the final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by Stichting Achmea Gezondheidszorg grant number Z659 and BMA-Telenatal BV. Neither the sponsor, nor Stichting Achmea Gezondheidszorg nor BMA-Telenatal is involved in the study design, interpretation of data or planned result reporting.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This trial has been approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC) of the UMC Utrecht. Trial reference number: 16-516. The MREC of the UMC Utrecht is accredited by the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO) since November 1999. Approval by the boards of management of University Medical Center Utrecht, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Diakonessenhuis Utrecht, OLVG Amsterdam, Martini Ziekenhuis Groningen and St. Antonius Ziekenhuis Nieuwegein is obtained prior to study start in each centre. Changes to the study protocol are documented in amendments and submitted for approval to the MREC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Queenan JT. Management of High‐Risk Pregnancy: John Wiley And Sons Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.NICE Guideline CG107 hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. RCOG Green-top Guideline No.31 - The Investigation and Management of the Small–for–Gestational–Age Fetus, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. NICE NICE Guideline NG25 preterm labour and birth, 2015. (accessed 15-11-2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gourounti C, Karpathiotaki N, Vaslamatzis G. Psychosocial stress in high risk pregnancy. Int Arch Med 2015;8 10.3823/1694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huynh L, McCoy M, Law A, et al. Systematic literature review of the costs of pregnancy in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2013;31:1005–30. 10.1007/s40273-013-0096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies. global Observatory for eHealth series. 3 Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ, Telehealth Sof. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med 2016;375:154–61. 10.1056/NEJMra1601705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van den Heuvel JF, Groenhof TK, Veerbeek JH, et al. eHealth as the next-generation perinatal care: an overview of the literature. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e202 10.2196/jmir.9262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chung Y, de Greeff A, Shennan A. Validation and compliance of a home monitoring device in pregnancy: Microlife WatchBP home. Hypertens Pregnancy 2009;28:348–59. 10.1080/10641950802601286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boatin AA, Wylie B, Goldfarb I, et al. Wireless fetal heart rate monitoring in inpatient full-term pregnant women: testing functionality and acceptability. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117043 10.1371/journal.pone.0117043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buysse H, De Moor G, Van Maele G, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of telemonitoring for high-risk pregnant women. Int J Med Inform 2008;77:470–6. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. M Versteegh M, M Vermeulen K, M A A Evers S, et al. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health 2016;19:343–52. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait anxiety inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol 1992;31:301–6. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergink V, Kooistra L, Lambregtse-van den Berg MP, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh depression scale during pregnancy. J Psychosom Res 2011;70:385–9. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van der Ham DP, van der Heyden JL, Opmeer BC, et al. Management of late-preterm premature rupture of membranes: the PPROMEXIL-2 trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boers KE, Vijgen SMC, Bijlenga D, et al. Induction versus expectant monitoring for intrauterine growth restriction at term: randomised equivalence trial (DIGITAT). BMJ 2010;341:c7087 10.1136/bmj.c7087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Broekhuijsen K, van Baaren G-J, van Pampus MG, et al. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2015;385:2492–501. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61998-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tranquilli AL, Dekker G, Magee L, et al. The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a revised statement from the ISSHP. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014;4:97–104. 10.1016/j.preghy.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.