Abstract

Introduction

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in adults is characterised by toxic immune activation and a sepsis-like syndrome, leading to high numbers of undiagnosed cases and mortality rates of up to 68%. Early diagnosis and specific immune suppressive treatment are mandatory to avoid fatal outcome, but the diagnostic criteria (HLH-2004) are adopted from paediatric HLH and have not been validated in adults. Experimental studies suggest biomarkers to sufficiently diagnose HLH. However, biomarkers for the diagnosis of adult HLH have not yet been investigated.

Methods and analysis

The HEMICU (Diagnostic biomarkers for adult haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in critically ill patients) study aims to estimate the incidence rate of adult HLH among suspected adult patients in intensive care units (ICUs). Screening for HLH will be performed in 16 ICUs of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The inclusion criteria are bicytopaenia, hyperferritinaemia (≥500 µg/L), fever or when HLH is suspected by the clinician. Over a period of 2 years, we expect inclusion of about 100 patients with suspected HLH. HLH will be diagnosed if at least five of the HLH-2004 criteria are fulfilled, together with an expert review; all other included patients will serve as controls. Second, a panel of potential biomarker candidates will be explored. DNA, plasma and serum will be stored in a biobank. The primary endpoint of the study is the incidence rate of adult HLH among suspected adult patients during ICU stay. Out of a variety of measured biomarkers, this study furthermore aims to find highly potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of adult HLH in ICU. The results of this study will contribute to improved recognition and patient outcome of adult HLH in clinical routine.

Ethics and dissemination

The institutional ethics committee approved this study on 1 August 2018 (Ethics Committee of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, EA4/006/18). The results of the study will be disseminated in an international peer-reviewed journal and presented at international conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), haemophagocytic syndrome (HS), macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), sepsis, biomarker, intensive care unit (ICU)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The HEMICU (Diagnostic biomarkers for adult haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in critically ill patients) study is the first prospective study to investigate biomarkers for the diagnosis of adult haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

The variety of analysed biomarkers will provide a better understanding of adult HLH pathophysiology.

Biobanking of DNA, plasma and serum of adult HLH patients will generate a database to investigate future research questions.

This study might be limited in that it only includes ICU patients and findings will not be generalisable to non-ICU patients.

Introduction

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a hyperinflammatory syndrome that is due to toxic immune activation and is associated with multiple organ failure and high mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients.1–3 Primary HLH due to genetic causes has been the subject of extensive research in paediatric medicine, resulting in an advanced understanding of its pathophysiology including identification of underlying genetic defects related to cytotoxic granule exocytosis.4 However, much less is known about HLH in adults, where the secondary form triggered by infections, autoimmune diseases, malignancies or immunosuppressive therapy is more common. Both hereditary primary and reactive secondary HLH are characterised by impaired immune function, that is, impaired natural killer (NK) or cytotoxic T cell function leading to abnormal activation of cytokine-releasing macrophages and T cells, and finally to an uncontrolled inflammatory condition known as cytokine storm.5

Currently, diagnosis is based on the HLH-2004 criteria (box 1) derived from the paediatric HLH-2004 protocol, which has not been validated in adult patients with HLH.6 7 Moreover, diagnosis of HLH in ICU-admitted patients is hampered by its sepsis-like presentation. Clinical features include repetitive fever, hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly and antibiotic-refractory infections, as well as pulmonary and renal involvement with consequent multiple organ failure.7 Laboratory findings may reveal cytopaenia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hyperferritinaemia and hypofibrinogenaemia. Timely diagnosis is crucial to initiate adequate treatment and thus to improve prognosis. As demonstrated by Jordan et al,8 early therapy reduces mortality to 30%–35%. However, up to 78% of all HLH cases in ICU remain undiagnosed, leading to mortality rates as high as 68%.2 9 Given the lack of specific diagnostic tests and the established use of unvalidated diagnostic criteria in adults, we aim to identify a biomarker panel of high sensitivity and specificity to allow early detection of HLH in critically ill patients.

Box 1. HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria6 .

HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria of which at least five must be fulfilled.

Ferritin ≥500 µg/L.

Fever (≥38.2°C).

Splenomegaly.

Cytopaenias in ≥2 lines (haemoglobin <90 g/L, platelets <100×109/L, neutrophils <1.0×109/L).

Hypertriglyceridaemia and/or hypofibrinogenaemia (fasting triglycerides ≥2.65 g/L, fibrinogen <1.5 g/L).

Haemophagocytosis in bone marrow or spleen or lymph nodes.

Low or absent natural killer cell activity.

Soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor) ≥2400 U/mL.

HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Methods and analysis

Design and screening

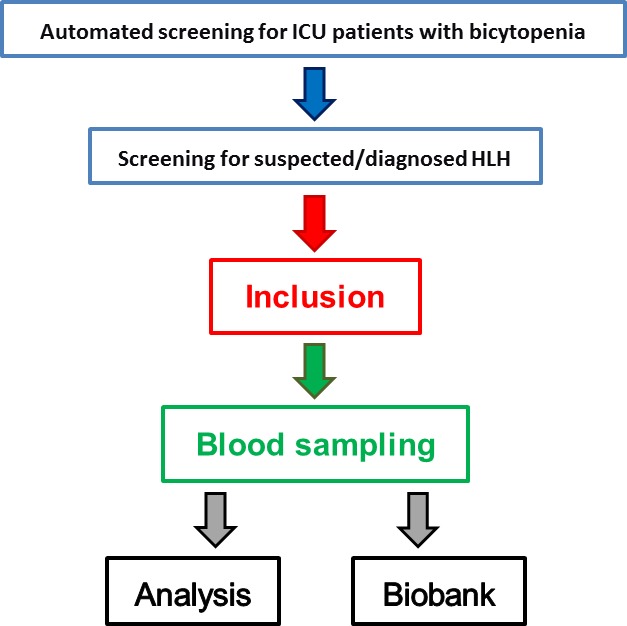

Over a 2-year period (ongoing since 1 September 2018), screening of all patients admitted to 16 adult ICUs of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin will be performed. As part of the process, electronic patient charts will be screened daily for bicytopaenia by an automated script. All patients with bicytopaenia are searched daily by the study team for HLH-2004 criteria (box 1), HScore10 and suspected HLH by clinicians. If highly suspected of HLH, the patient will be enrolled after informed consent by the patient himself or a legal representative. Immediately after study enrolment and before initiation of specific HLH treatment, whole blood samples will be obtained for all analyses. Additionally, plasma and serum samples as well as DNA will be stored in a biobank (figure 1). HLH will be diagnosed if at least five of the HLH-2004 criteria are fulfilled and finally confirmed after a case-by-case review by two HLH experts. The study aims to include at least 100 patients with suspected HLH. Patients in whom HLH is not confirmed will serve as controls.

Figure 1.

Screening protocol and blood sampling. HLH, haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; ICU, intensive care unit.

Study population and eligibility criteria for patients

Inclusion criteria

ICU patients of at least 18 years old.

Suspected or diagnosed HLH: based on the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria (bicytopaenia, hyperferritinaemia (≥500 µg/L), fever) or as suspected by clinicians.

Eligible to informed consent by the patient himself or a legal representative.

Exclusion criteria

Participation in an interventional study.

Female patients who are pregnant or breast feeding.

Setting

Participating ICUs include anaesthesiological, surgical, medical, neurological and mixed ICUs. In total, 16 ICUs of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin will provide patients.

Objectives and hypotheses

This study aims to investigate critically ill patients for adult HLH and estimate its incidence rate among suspected patients during ICU stay. Second, a panel of various biomarker candidates from experimental and paediatric studies will be measured to explore potential to diagnose HLH in adult ICU-admitted patients. As a result, HLH might be detected earlier, leading to an improved outcome. Highly sensitive biomarkers may also help to distinguish HLH from sepsis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the development of the research question, design, recruitment and conduct of this study. The results of immunological analyses will be sent immediately to the physicians in charge. Patients will be informed of the global results of the study at their request.

Statistical analyses

The incidence rate of HLH among suspected adult patients during ICU stay will be calculated with 95% CI. Investigation of potential biomarkers will be exploratory. Descriptive statistics between patient groups with confirmed HLH and controls will incorporate mean and SD or absolute and relative frequencies depending on each variable’s scale. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models with confirmed HLH diagnosis as outcome will be calculated for different combinations of influencing variables and biomarkers. Receiver operating characteristic analysis will be performed to determine discrimination ability as measured by the area under the curve for each continuous biomarker. Sensitivity and specificity within our patient sample will be given for cut-off points with the highest Youden index. Highly potential markers are found when sensitivity and specificity each reaches 90%.

Outcome measures

Primary endpoint

Incidence rate of adult HLH among suspected patients during ICU stay.

Secondary endpoints

Identification of highly sensitive and highly specific biomarkers to safely diagnose adult HLH in ICU.

Trigger and underlying conditions.

Therapy of HLH by clinicians.

ICU and hospital length of stay.

Mortality and survival after 6 months.

Quality of life questionnaire '36-item Short Form Health Survey' after 6 months.11

HIV antibodies and antigen.

Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus viral loads.

Inflammatory markers (ferritin, C reactive protein, procalcitonin, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-18, IL-33, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-ɣ, sCD25, sCD163 and presepsin).12

Perforin and CD107a.13

Fibrinogen, triglycerides, bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, alanine aminotransferase (ALAT) and aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT).

Sodium, serum albumin and serum protein electrophoresis.

Detailed immune status (differential blood count, T cells (CD3+), B cells (CD19+), NK cells (CD16+), T helper cells (CD4+), cytotoxic T cells (CD8+), CD4:CD8 ratio, human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR of CD8+, CD11a of CD8−, CD57 of CD8−, CD28 of CD8+, HLA-DR of monocytes, CD56bright and CD69 of NK cells).

Glycosylated ferritin14 and microRNAs (miR-205-5p, miR-194-5p and miR-30c-5p).15

Chemokines CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 (RANTES), CCL11 (eotaxin), CCL19, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL9, CXCL8 (IL-8), CXCL10 (IP-10) and CXCL12 (SDF1A).16

HLA typing.

Biobanking for future research questions (eg, genetic polymorphisms and gene expression of PRF1, UNC13D, STX11 and STXBP27).

Data collection

The number of screened patients, the number of patients with suspected HLH who could not be included as well as data on all outcome measures will be collected prospectively. If the patient received immunosuppressive therapy prior to inclusion, this will be documented separately. Further data including patient demographic data, past medical conditions, physicians’ reports and routine laboratory results will be abstracted from the hospital’s database. For follow-up 6 months after study inclusion, patients will be contacted either by telephone or by mail as indicated on enrolment to assess health-related quality of life and mortality, respectively.

Immunological measurements

Plasma concentrations of soluble IL-2R (sIL-2R or sCD25) will be determined with the IMMULITE semiautomatic chemiluminescent immunoassay (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Additional soluble factors IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-18, IL-33, TNF-α and IFN-ɣ will be measured by Meso Scale Discovery (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Maryland USA). The kit provides all reagents, together with a 96-well plate with specific precoated spots, the detection antibodies and assay diluent. The standard will be reconstituted with assay diluent to obtain a lot-specific concentration which differs for all cytokines. The vials are inverted multiple times for mixing, and after vortexing the vials will be kept for 5–10 min at room temperature (RT) and then on ice until use. Preparation of further serial 1:5 dilution of cytokine standard is performed. Quality controls (low and high) are components of the kits, and respective quality control ranges are provided by the manufacturer. The quality controls (low and high) will be reconstituted with 250 µL of deionised water. The vials are inverted multiple times for mixing, and after vortexing kept for 5–10 min at RT and then on ice until use. Plasma concentrations of soluble CD163 protein levels will be determined with the Quantikine ELISA Human CD163 Immunoassay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA). The minimum detectable dose ranged from 0.058 to 0.613 ng/mL. For measurement of presepsin, Presepsin (Human) ELISA Kit will be used (BioVision, California, USA) with a detection range of 0.156–10 ng/mL.

Flow cytometric analysis of human lymphocyte subsets in EDTA whole blood will be performed, as described recently.17 Briefly, the following mouse antihuman fluorescently labelled monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are used for quantification of lymphocytes subsets and analysis of T and NK cell activation markers: cluster of differentiation (CD)3 Allophycocyanin-Alexa Fluor 750 (APC-A750), CD4 energy coupled dye, CD8 APC, CD11a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD14 FITC, CD16 phycoerythrin (PE), CD19 PE-Cy5.5, CD28 PC5, CD45 Krome-Orange, CD56 PE or CD56 APC, CD57 Pacific Blue, CD69 PE, and HLA-DR PE (all from Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany). Functional analysis of NK cells will be performed using the CD107a degranulation assay according to a protocol published by Bryceson et al.18 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) will be isolated by density gradient centrifugation and incubated overnight in the presence or absence of 3600 IU/mL recombinant IL-2 (Peprotech). PBMC will then be incubated with the target cell line K562 (ATCC) in a 1:1 ratio for 3 hours. Subsequently, CD107a expression on NK cells is assessed by staining samples with fluorescently labelled antibodies against lineage markers and an anti-CD107a FITC-labelled mAb (eBioscience). Perforin expression in NK cells will be assessed by intracellular staining in unstimulated NK cells using the PerFix-nc reagent (Beckman Coulter) for cell permeabilisation and an APC-labelled antiperforin mAb (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Expression of HLA-DR on monocytes will be determined by flow cytometry using a highly standardised quantitative assay, as described earlier.19 In short, whole blood in Vacutainer tubes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA) containing EDTA is stained with 20 µL of monoclonal PE-conjugated anti-HLA-DR and PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-CD14 antibodies (QuantiBRITE HLA-DR/monocyte; BD Biosciences) in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Erythrocyte lysis will be done with 0.5 mL of lysing solution (BD Biosciences) for another 30 min at room temperature. Finally, the cells are washed with 1 mL phosphate buffer saline (PBS) buffer containing 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) and analysed on a Navios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). HLA-DR surface expression on monocytes will be calculated as mAb bound per cell using the QuantiBRITE PE calibration beads. All flow cytometric analyses will be performed on a 10-colour Navios flow cytometer using the Navios Software (Beckman Coulter). Human glycosylated ferritin will be determined by ELISA (MyBioSource, San Diego, USA). The sensitivity of this kit is 2.0 ng/mL.

The expression of miR-205-5p, miR-194-5p and miR-30c-5p will be determined in whole blood, plasma and serum using a protocol published by Balcells et al.20 Briefly, after RNA isolation, miRNAs are polyadenylated and then reverse-transcribed with a special primer (RT-primer). For quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), two specific primers for each miRNA are designed using a software tool from Busk.21 All primers are tested for specificity and efficiency. qPCR will be performed with SYBR Green using QuantStudio5 (Thermo Fisher, Darmstadt, Germany). The quantification of chemokines involved in cell trafficking and effector functions of lymphocytes, granulocytes and mononuclear cells from the CC subfamily (CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL11, CCL19 and CCL20) as well as the CXC subfamily (CXCL1, CXCL8 (IL-8), CXCL10 and CXCL12) will be performed with the LUNARIS Human 11-Plex Chemokine Kit (AYOXXA Biosystems, Cologne, Germany).

Determination of HLA typing will be performed by reverse sequence-specific oligonucleotide assay LABType (One Lambda, Canoga Park, California, USA). Typing will be assessed on an intermediate resolution level for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1. The assay will be performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and data will be acquired on a Luminex FlexMAP 3D machine (Luminex, Austin, Texas, USA).

Informed consent in critically ill patients

Written informed consent will be obtained from all patients or their legally authorised representatives. Consent for genetic analyses in future projects will be obtained separately.

Sample size

The true incidence of adult HLH in ICU is unknown. According to our own research9 and the annual number of patients admitted to our ICU, we expect to see about 200 patients with diagnosed HLH over 2 years and about 400 with suspected HLH. Of these, we hope to include at least 100 patients with suspected HLH into the study, of whom about 50 patients are expected to be diagnosed with HLH. When the sample size is 100, a two-sided 95.0% CI for a single proportion using the large sample normal approximation will extend 0.1 from the observed proportion for an expected proportion of 0.5 (nQuery Advisor V.7.0).

Dissemination

The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov on 27 April 2018. The results of the study will be disseminated in an international peer-reviewed journal and presented at international conferences.

Discussion

HLH is a rare condition in adults with poor prognosis. Due to the paucity of data available on adult HLH, recognition remains low, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment, and finally fatal outcome. This is the first prospective study to systematically investigate routine and non-routine parameters for biomarker development. Importantly, the daily systematic screening will help to identify patients with HLH at an early stage of the syndrome, which ultimately will improve patient care, safety and outcome. Moreover, describing a distinct pattern of biomarkers generates new hypothesis for future research, thereby potentially providing targets for therapy development. With regard to clinical practice, the HEMICU (Diagnostic biomarkers for adult haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in critically ill patients) study seeks to inform clinicians about HLH and ICU therapies to improve outcomes for patients with HLH. However, it is of note that this study does not seek to advise the clinician in charge to change therapy. No change in routine management is intended due to the observational study design, and final decisions are left to the discretion of the responsible clinician.

Strengths and limitations

This study might be limited in that it only includes ICU patients and findings will not be generalisable to non-ICU patients. In addition, patients might have developed HLH before ICU admission and will thus be detected and measurements obtained at an advanced stage of the disease, possibly limiting comparability of the results. Moreover, we will not assess longitudinal parameters, preventing us from describing the dynamics of biomarkers over time. However, as this study aims to develop a tool facilitating diagnosis at the earliest possible time point, study endpoints will not be affected by lack of repeated measurements. Possible advances of this study include comprehensive laboratory testing of parameters which have previously been suggested to be associated with HLH.12–16 Previous studies, most of which are retrospective in nature, aimed at identifying associations to detect risk factors.2 22 Therefore, the HEMICU study is the first prospective study of its kind.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, the Department of Surgery (CCM/CVK), the Medical Department, Division of Nephrology and Internal Intensive Care Medicine (CVK/CCM), the Medical Department, Division of Infectiology and Pneumonology, the Medical Department, Division of Cardiology (CVK), the Department of Cardiology (CBF), the Department of Neurology with Experimental Neurology, and the Department of Anesthesiology and Operative Intensive Care Medicine (CBF) for being part of our study and for excellent collaboration. We also thank the BIH Biobank Core Facility for support, coordination and storage of blood samples (biobanking). We are grateful to Dr Kathrin Scholtz for monitoring the study. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Funds of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept: GL. Conceived and designed the experiments: GL, CvH, NP, CM, PLR, TS, NL, H-DV, DK. Performing the experiments: GL, CK, CvH, NP, CM, PN, FSS, GV, FB, NU, UK, NL, LA. Analysing the data: GL, CK, PN, FSS, SKP, JK, PLR, TS. Wrote the manuscript: GL, CK, CvH, NP, CM, SKP, NL, LA, FMB, DK, CS. Commented on the manuscript: all authors.

Funding: GL is a participant of the BIH Charité Clinician Scientist Program granted by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and Berlin Institute of Health (BIH). The study is supported by the Department of Anesthesiology and Operative Intensive Care Medicine (CCM, CVK), Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The institutional ethics committee approved this study on 1 August 2018 (Ethics Committee of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, EA4/006/18). The data protection commissioner also approved the study (91-SP-18).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Buyse S, Teixeira L, Galicier L, et al. . Critical care management of patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Intensive Care Med 2010;36:1695–702. 10.1007/s00134-010-1936-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barba T, Maucort-Boulch D, Iwaz J, et al. . Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in intensive care unit: a 71-Case Strobe-Compliant retrospective study. Medicine 2015;94:e2318 10.1097/MD.0000000000002318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lachmann G, La Rosée P, Schenk T, et al. . [Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis : a diagnostic challenge on the ICU]. Anaesthesist 2016;65:776–86. 10.1007/s00101-016-0216-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Devitt K, Cerny J, Switzer B, et al. . Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res Rep 2014;3:42–5. 10.1016/j.lrr.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (hLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2009:127–31. 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Henter J-I, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. . HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. 10.1002/pbc.21039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, et al. . Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014;383:1503–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61048-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, et al. . How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2011;118:4041–52. 10.1182/blood-2011-03-278127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lachmann G, Spies C, Schenk T, et al. . Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: potentially underdiagnosed in intensive care units. Shock 2018;50:149–55. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. . Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:2613–20. 10.1002/art.38690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chrispin PS, Scotton H, Rogers J, et al. . Short form 36 in the intensive care unit: assessment of acceptability, reliability and validity of the questionnaire. Anaesthesia 1997;52:15–23. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.015-az014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Put K, Avau A, Brisse E, et al. . Cytokines in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: tipping the balance between interleukin-18 and interferon-γ. Rheumatology 2015;54:1507–17. 10.1093/rheumatology/keu524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rubin TS, Zhang K, Gifford C, et al. . Perforin and CD107a testing is superior to NK cell function testing for screening patients for genetic HLH. Blood 2017;129:2993–9. 10.1182/blood-2016-12-753830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nabergoj M, Marinova M, Binotto G, et al. . Diagnostic and prognostic value of low percentage of glycosylated ferritin in acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a single-center study. Int J Lab Hematol 2017;39:620–4. 10.1111/ijlh.12713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bay A, Coskun E, Oztuzcu S, et al. . Evaluation of the plasma micro RNA expression levels in secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2013;5:e2013066 10.4084/mjhid.2013.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bracaglia C, de Graaf K, Pires Marafon D, et al. . Elevated circulating levels of interferon-γ and interferon-γ-induced chemokines characterise patients with macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:166–72. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Klehmet J, Staudt M, Ulm L, et al. . Circulating lymphocyte and T memory subsets in glucocorticosteroid versus IVIg treated patients with CIDP. J Neuroimmunol 2015;283:17–22. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bryceson YT, Pende D, Maul-Pavicic A, et al. . A prospective evaluation of degranulation assays in the rapid diagnosis of familial hemophagocytic syndromes. Blood 2012;119:2754–63. 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Döcke W-D, Höflich C, Davis KA, et al. . Monitoring temporary immunodepression by flow cytometric measurement of monocytic HLA-DR expression: a multicenter standardized study. Clin Chem 2005;51:2341–7. 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Balcells I, Cirera S, Busk PK. Specific and sensitive quantitative RT-PCR of miRNAs with DNA primers. BMC Biotechnol 2011;11:70 10.1186/1472-6750-11-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Busk PK. A tool for design of primers for microRNA-specific quantitative RT-qPCR. BMC Bioinformatics 2014;15:29 10.1186/1471-2105-15-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishii E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, et al. . Nationwide survey of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Japan. Int J Hematol 2007;86:58–65. 10.1532/IJH97.07012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.