Abstract

Objective

Obesity and hypertension (HTN) have become increasingly prevalent in Taiwan. People with obesity are more likely to have HTN. In this study, we evaluated several anthropometric measurements for the prediction of HTN in middle-aged and elderly populations in Taiwan.

Design

Cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

Community-based investigation in Guishan Township of northern Taiwan.

Participants

A total of 396 people were recruited from a northern Taiwan community for a cross-sectional study. Anthropometrics and blood pressure were measured at the annual health exam. The obesity indices included body mass index (BMI), body fat (BF) percentage and waist circumference (WC).

Outcome measures

Statistical analyses, including Pearson’s correlation, multiple logistic regression and the area under ROC curves (AUCs) between HTN and anthropometric measurements, were used in this study.

Results

Of the 396 people recruited, 200 had HTN. The age-adjusted Pearson’s coefficients of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 0.23 (p<0.001), 0.14 (p=0.01) and 0.26 (p<0.001), respectively. Multiple logistic regression of the HTN-related obesity indices showed that the ORs of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 1.15 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.23, p<0.001), 1.07 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.11, p<0.001) and 1.06 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.08, p<0.001), respectively. The AUCs of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 0.626 (95% CI 0.572 to 0.681, p<0.001), 0.556 (95% CI 0.500 to 0.613, p=0.052) and 0.640 (95% CI 0.586 to 0.694, p<0.001), respectively.

Conclusions

WC is a more reliable predictor of HTN than BMI or BF percentage. The effect of abdominal fat distribution on blood pressure is greater than that of total BF amount.

Keywords: abdominal fat, elderly, hypertension, middle-aged, obesity index

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted a community-based study and comprehensively collected various data from a health promotion project that may have clinical implications.

This is the first study to explore the association between different obesity indices and hypertension (HTN) in a middle-aged and elderly Taiwanese population.

A cross-sectional study cannot effectively determine the causal relationship between obesity indices and HTN.

Our findings were obtained from community-based subjects and cannot be generalised to the whole middle-aged and elderly population in Taiwan.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity has increased progressively in Taiwan, particularly among the elderly. However, the precise definition of obesity in the elderly has yet to be developed.1 Traditionally, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC) and body fat (BF) percentage have been used to evaluate obesity. The cut-off values of these obesity indices have not been defined for the elderly population1 because sarcopenia causes loss of muscle mass and fatty tissues increase with ageing.2 Ageing and sarcopenia cause muscle loss and increase fat deposition, making BMI an inaccurate reference. Lower BMI in the elderly may not indicate a lower BF percentage, as it could be correlated with muscle loss coupled with a relative BF increase.

The utility of different types of obesity indices has been discussed in the past. If the BF percentage determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry is regarded as a gold standard, it would be difficult to assess as the sensitivity and specificity of BMI, which vary by sex.3 For older women, a BMI of 25 has the best sensitivity and specificity. For older men, a BMI of 27 is the most appropriate. Different obesity indices show different comorbidity risks. WC is more strongly associated with a high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than BMI among middle-aged and elderly persons in Taiwan.4 5 BMI and WC are more positively correlated with insulin resistance than BF percentage.6

Hypertension (HTN) is also a common problem among the elderly population, with increasing prevalence, and is associated with the risks of CVD, stroke and chronic kidney disease.7 HTN has different effects in different age groups. Isolated systolic HTN is predominant in the elderly.8 There are many physiological changes related to the development of HTN in the elderly, such as arterial stiffness, increasing pulse pressure, changes in renin and aldosterone levels, decreased renal salt excretion, declined renal function, changes in the autonomic nervous system sensitivity and function, and changes in endothelial function.9

Obesity is a major risk factor for essential HTN.10–12 The development of HTN caused by obesity can occur via multiple mechanisms: insulin resistance, adipokine alterations, inappropriate sympathetic nerve function and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation, structural and functional abnormalities in the kidney, heart and vascular changes, and immune maladaptation.10 13 Uric acid and incretin or dipeptidyl peptidase 4 activity alteration also contribute to the development of HTN in the context of obesity.13 Different obesity indices have different correlations with HTN. High levels of BMI and WC have increased the risk of HTN among rural Chinese women.14 15 WC is more strongly associated with the development of HTN than BMI.16 In another study, no significant difference in HTN prediction between BMI and WC was found.17 Another similar study showed that the association of obesity indices with HTN in Chinese elderly individuals differed by sex and age.18 BMI in men and hip circumference in women showed a significant impact on the risk of HTN.18 Collectively, it appears that the relationship between various obesity indices and HTN has been relatively well established in the general population but not in the middle-aged and elderly population, an age group that has a high risk of HTN. This study was designed to investigate the relationship between different obesity indices and HTN among middle-aged and elderly Taiwanese individuals.

Methods

Study design and study population

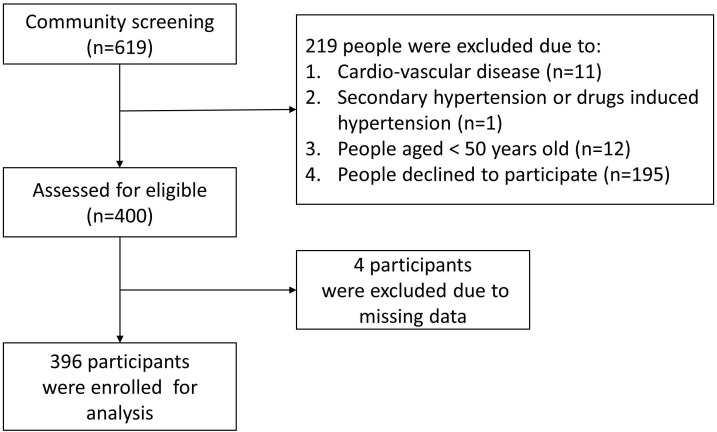

This is a cross-sectional, community-based study. We collected data from a community health promotion project of Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital conducted between February and August 2014. A total of 619 subjects aged 50 years or older recruited through poster promotion or notification from the community office participated in this project. The recruitment posters were all placed in the community, and all participants were recruited from the community. After exclusion, 400 subjects were eligible to be enrolled in this study. Four participants were excluded because they had pacemaker implantations (figure 1). As a result, 396 participants were enrolled, and all participants completed a questionnaire including personal information and medical history (online supplementary file 1) during a face-to-face interview. Anthropometric measurements were conducted by trained research assistants or nurses under the supervision of a medical doctor. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) participants with coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease or heart failure; (2) participants with secondary HTN or medications that increase BP, such as licorice, oral contraceptives, steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cocaine, amphetamines, erythropoietin, ciclosporin, tacrolimus and anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor); and (3) participants with incomplete or missing data. Only four participants were excluded due to lack of BF percentage measurements. Finally, 396 participants were enrolled in the analysis. Written informed consent was given by all the participants before enrolment.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

bmjopen-2019-031660supp001.pdf (267.3KB, pdf)

Anthropometric and laboratory measurements

Each participant was required to complete a questionnaire. The questionnaires were completed by trained interviewers based on face-to-face interviews. Basic personal data included age, sex, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), education level, history of HTN, diabetes, metabolic syndrome and hyperlipidemia. Lifestyle factors included alcohol consumption, current smoking and regular exercise. HTN was defined as SBP ≧140 mm Hg or DBP ≧90 mm Hg, current use of antihypertensive medications, or history of HTN. The definition of HTN was based on the 2015 Guidelines of the Taiwan Society of Cardiology and the Taiwan Hypertension Society for the Management of Hypertension. Laboratory data included alanine aminotransferase (ALT), creatinine, fasting sugar, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), total cholesterol, triglycerides and uric acid. Each participant’s blood pressure was measured on the right arm in a sitting position using a standardised electronic sphygmomanometer (OMRON, model HEM-7130). The participants rested for at least 5 min in a seated position before the measurements, with their arms supported at the heart level. We measured blood pressure in each subject three times, separated by an interval of 10 min to minimise random error and provide a more accurate basis for the estimation of blood pressure and calculated the mean value of these three readings. There was a warning light on our electronic sphygmomanometer for irregular heartbeat detection. We also performed physical examination for every participant, including manual auscultation, and there was no participant with an irregular heartbeat detected by the warning light or manual auscultation. The obesity indices included BMI, BF percentage and WC. The BF percentage was measured with an 8-contact electrode bioelectrical impedance analysis device (Tanita BC-418, Tanita, Tokyo, Japan). BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). WC was measured at the level midway between the iliac crests and the lowest rib margin at minimal respiration in a standing position.

Statistical analysis

The minimum sample size for this study was calculated at the initial stage of the study. After previewing a relatively smaller population, we found that the non-HTN to HTN ratio was ~1:1. Considering 90% power, 95% CI, 0.30 as the exposure (obesity) rate among the non-HTN individuals, and a non-HTN to HTN ratio of 1:1, we calculated that 308 participants were required to detect at least two ORs differences between these two study groups.

The normality of continuous variables was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We express all continuous variables as the mean and SD, while categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. In univariate analysis, independent T-test and χ2 test were used to compare HTN and non-HTN subjects. Correlations were assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficient and the coefficient of determination (r2) between different obesity indices and blood pressures. In multivariate analysis, binary logistic regression was used to adjust covariates. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for BF percentage, WC and BMI as predictors of HTN. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) and the optimal cut-off points for HTN prediction by BMI, WC and BF percentage were determined by the largest sum of specificity and sensitivity. The analysis was performed with SPSS Statistics V.22.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved.

Results

A total of 396 participants were enrolled in the analysis, and 200 had HTN (SBP ≧140 mm Hg or DBP ≧90 mm Hg), with a prevalence of 50.5%. The average age was 64.44 years. There were no significant static differences in alcohol consumption, current smoking, ALT, total cholesterol, regular exercise or dyslipidemia between people with and without HTN. People with HTN had higher levels of BMI, WC, BF percentage, fasting sugar, triglycerides, uric acid and creatinine with static significance (table 1). They also had a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome, diabetes and hyperlipidemia but lower LDL and HDL levels.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the study population according to HTN and non-HTN

| Variables | HTN | |||||||||

| Total (n=396) | Yes (n=200) | No (n=196) | P value | |||||||

| Age (years) | 64.44±8.46 | 65.63±8.53 | 63.23±8.23 | 0.005 | ||||||

| SBP (mm Hg) | 129.61±16.70 | 138.51±15.92 | 120.53±11.92 | <0.001 | ||||||

| DBP (mm Hg) | 77.10±11.28 | 81.24±11.74 | 72.88±9.04 | <0.001 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.55±3.50 | 25.35±3.83 | 23.73±2.92 | <0.001 | ||||||

| BF percentage (%) | 29.98±8.41 | 30.92±8.46 | 29.02±8.27 | 0.025 | ||||||

| WC (cm) | 85.12±9.66 | 87.52±10.31 | 82.67±8.28 | <0.001 | ||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 22.67±13.00 | 22.81±12.66 | 22.53±13.38 | 0.834 | ||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.77±0.43 | 0.82±0.42 | 0.72±0.43 | 0.019 | ||||||

| FPG (mg/dL) | 96.31±25.84 | 100.18±29.85 | 92.36±20.29 | 0.002 | ||||||

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 54.29±13.81 | 52.13±13.91 | 56.49±13.39 | 0.002 | ||||||

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 118.54±32.19 | 115.05±30.87 | 122.11±33.18 | 0.029 | ||||||

| TC (mg/dL) | 197.30±35.80 | 194.29±35.16 | 200.37±36.28 | 0.091 | ||||||

| TGs (mg/dL) | 122.68±66.00 | 136.02±74.02 | 109.08± | 53.52 | <0.001 | |||||

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 5.75±1.40 | 5.94±1.47 | 5.56± | 1.31 | 0.007 | |||||

| Men, n (%) | 140 | (35.35%) | 76 | (38.00%) | 64 | (32.65%) | 0.266 | |||

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 75 | (18.94%) | 36 | (18.00%) | 39 | (19.90%) | 0.630 | |||

| Current smoking, n (%) | 43 | (10.86%) | 24 | (12.00%) | 19 | (9.69%) | 0.461 | |||

| Regular exercise, n (%) | 325 | (82.07%) | 160 | (80.00%) | 165 | (84.18%) | 0.278 | |||

| Education years, n (%) | 0.294 | |||||||||

| ≦6 | 205 | (51.77%) | 111 | (55.50%) | 94 | (47.96%) | ||||

| 7~12 | 157 | (39.65%) | 72 | (36.00%) | 85 | (43.37%) | ||||

| >12 | 34 | (8.59%) | 17 | (8.50%) | 17 | (8.67%) | ||||

| Current single, n (%) | 74 | (18.69%) | 49 | (24.50%) | 25 | (12.76%) | 0.003 | |||

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 143 | (36.11%) | 108 | (54.00%) | 35 | (17.86%) | <0.001 | |||

| DM, n (%) | 79 | (19.95%) | 51 | (25.50%) | 28 | (14.29%) | 0.005 | |||

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 260 | (65.66%) | 137 | (68.50%) | 123 | (62.76%) | 0.229 | |||

Clinical characteristics are expressed as the mean±SD for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables. P values were derived from independent t-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BF, body fat; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HTN, hypertension; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TGs, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference.

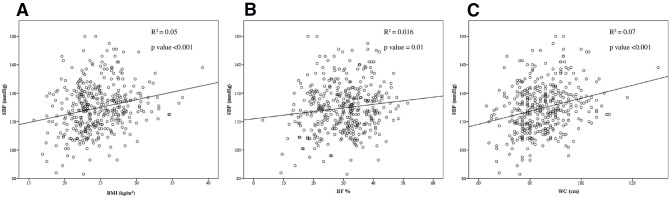

We analysed the correlation between SBP and obesity indices. The age-adjusted Pearson’s coefficient of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 0.23 (p<0.001), 0.14 (p=0.01) and 0.26 (p<0.001), respectively (table 2, figure 2). In addition, multiple logistic regression of the HTN-related obesity indices showed that the ORs of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 1.15 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.23, p<0.001), 1.07 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.11, p<0.001) and 1.06 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.08, p<0.001), respectively (table 3). Further multiple logistic regression analyses revealed that these obesity indices remained independent risk factors for HTN in the subgroup of participants with an age ≧65 years old (table 4A and subgroups of either sex (table 4B,C). The ORs of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 1.11 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.22, p=0.047), 1.06 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.12, p=0.03) and 1.04 (95% CI 1.00 to 1.08, p=0.04), respectively, in the subgroup of participants with an age ≧65 years old (table 4A). The ORs of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 1.19 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.33, p=0.002), 1.11 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.19, p=0.003) and 1.08 (95% CI 1.03–1.12, p=0.01), respectively, in the subgroup of male participants (table 4B). The ORs of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 1.13 (95% CI 1.04 to 1.23, p=0.003), 1.06 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.10, p=0.01) and 1.04 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.08, p=0.01), respectively, in the subgroup of female participants (table 4C).

Table 2.

The correlation between SBP and obesity indices

| Variables | SBP (n=396) | |||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for age | |||

| Pearson’s coefficient | P value | Pearson’s coefficient | P value | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.22 | <0.001 | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| BF percentage (%) | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| WC (cm) | 0.26 | <0.001 | 0.26 | <0.001 |

BF, body fat; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; WC, waist circumference.

Figure 2.

The correlation between (A) BMI and SBP, (B) BF% and SBP and (C) WC and SBP. BF, body fat; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; WC, waist circumference.

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression of the obesity indices related to HTN in the screened population (n=396)

| BMI | BF percentage | Waist circumference | |||||||

| ORs | 95% CI | P value | ORs | 95% CI | P value | ORs | 95% CI | P value | |

| Model 1* | 1.15 | 1.08 to 1.23 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.05 | 0.03 | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.08 | <0.001 |

| Model 2† | 1.16 | 1.09 to 1.24 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.04 to 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Model 3‡ | 1.15 | 1.08 to 1.23 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.03 to 1.11 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.08 | <0.001 |

*Model 1: Unadjusted.

†Model 2: Multiple logistic regression adjusted for age and sex.

‡Model 3: Multiple logistic regression adjusted for factors in model two plus DM and hyperlipidemia.

BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses of the association of obesity indices with HTN according to age and sex

| BMI | BF percentage | Waist circumference | |||||||

| ORs | 95% CI | P value | ORs | 95% CI | P value | ORs | 95% CI | P value | |

| (A) Age≧65 years old (n=166) | |||||||||

| Model 1* | 1.09 | 0.99 to 1.20 | 0.06 | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.08 | 0.04 | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.06 | 0.08 |

| Model 2† | 1.10 | 1.00 to 1.21 | 0.05 | 1.05 | 1.00 to 1.11 | 0.0497 | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.07 | 0.04 |

| Model 3‡ | 1.11 | 1.00 to 1.22 | 0.047 | 1.06 | 1.01 to 1.12 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.08 | 0.04 |

| (B) Male (n=140) | |||||||||

| Model 1* | 1.17 | 1.06 to 1.30 | 0.002 | 1.10 | 1.03 to 1.17 | 0.004 | 1.07 | 1.03 to 1.12 | <0.001 |

| Model 2† | 1.08 | 1.03 to 1.12 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 1.03 to 1.17 | 0.003 | 1.08 | 1.03 to 1.12 | <0.001 |

| Model 3‡ | 1.19 | 1.06 to 1.33 | 0.002 | 1.11 | 1.03 to 1.19 | 0.003 | 1.08 | 1.03 to 1.12 | 0.001 |

| (C) Female (n=256) | |||||||||

| Model 1* | 1.14 | 1.05 to 1.23 | 0.001 | 1.06 | 1.02 to 1.11 | 0.004 | 1.05 | 1.02 to 1.09 | 0.001 |

| Model 2† | 1.14 | 1.05 to 1.23 | 0.002 | 1.06 | 1.02 to 1.11 | 0.01 | 1.05 | 1.01 to 1.08 | 0.004 |

| Model 3‡ | 1.13 | 1.04 to 1.23 | 0.003 | 1.06 | 1.01 to 1.10 | 0.01 | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.08 | 0.01 |

*Model 1: Unadjusted.

†Model 2: Multiple logistic regression adjusted for age and sex.

‡Model 3: Multiple logistic regression adjusted for factors in model two plus DM and hyperlipidemia.

BF, body fat; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

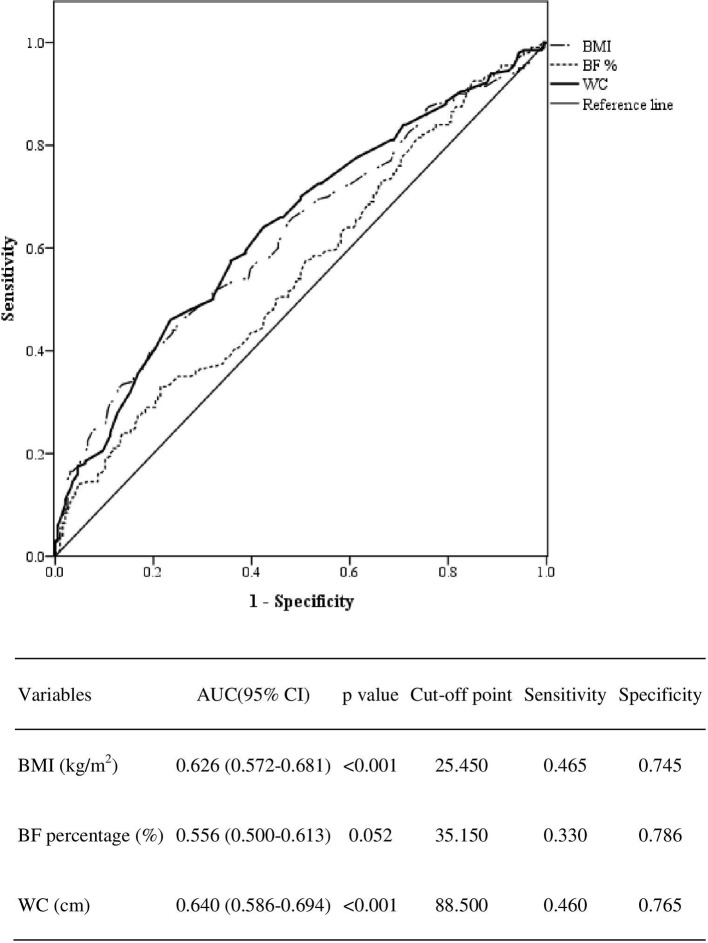

Finally, the AUCs of BMI, BF percentage and WC were 0.626 (95% CI 0.572 to 0.681, p<0.001), 0.556 (95% CI 0.500 to 0.613, p=0.052) and 0.640 (95% CI 0.586 to 0.694, p<0.001), respectively (figure 3). WC had the largest AUC for predicting HTN.

Figure 3.

ROC curves for obesity indices as predictors of hypertension (HTN). BF, body fat; BMI, body mass index; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SBP, systolic blood pressure; WC, waist circumference.

Discussion

Our study revealed a positive correlation between all obesity indices and HTN. BMI, BF percentage and WC were found to be associated with HTN or higher systolic pressure through the independent T-test, χ2 test, correlation analysis and multivariate analysis. These obesity indices remained independent risk factors for HTN in the subgroup of participants with an age ≧65 years old (a population with a high expected prevalence of sarcopenia) and subgroups of either sex. Regarding the AUC, WC had the largest AUC for predicting HTN. Clinical adiposity indices, such as BMI and WC, were linked with HTN in review articles.19 20 A Chinese study showed that women with obesity defined by BMI or WC have an increased risk of developing HTN.14 Another study on predicting HTN with different obesity indices reached a similar conclusion.16 Compared with BMI, WC has a stronger association with HTN development.16 However, these previous observations were mainly from the general population. Thus, the novel finding of this study is the association between various obesity indices and HTN in the middle-aged and elderly population, an age group that has a high risk of HTN.

A Korean study showed a similar outcome as that of our study.21 The central obesity index, WC, is better than BMI for predicting HTN in middle-aged Korean people.21 The relationship between central obesity and HTN has also been mentioned in previous reviews.22 23 Visceral obesity and leptin play a crucial role in the development of HTN in patients with obesity.22 Fat is an important endocrine organ in patients with obesity. Adipokines, such as adiponectin, leptin and resistin, may result in arterial stiffness and predispose individuals to endothelial dysfunction and HTN.23

Our study suggested that the optimal cut-off point for predicting HTN with BMI was 25.45 kg/m2, with BF percentage was 35.15% and with WC was 88.5 cm. However, another study of a younger population (40 to 59 years old) suggested that the optimal BMI and WC cut-off values are 29.57 kg/m2 and 90.5 cm.24 Because age is also a risk factor for HTN, the cut-off point for BMI for elderly individuals is lower. Similar to the results of the BMI-obesity literature review, other age-related studies have shown conflicting results.17 A study in Nigeria found that BMI and WC are both good predictors of HTN risk. However, there was no significant difference between the AUCs of BMI and WC.17 In a Chinese rural cohort study, BMI was superior to WC for predicting incident HTN in both sexes.25 Another study among Chinese elderly individuals showed a sex difference in predicting HTN with obesity indices.18 The results showed that BMI is associated with a significant risk of developing HTN in men only.18 Finally, a study showed that the obesity index predictions differed between sexes.26 The combination of BMI +WC can improve the estimation of HTN risk.26

There were several limitations in our study. First, a cross-sectional study cannot effectively determine the causal relationship between obesity indices and HTN. Second, the participants in this study came from a relatively small community, so selection bias should be considered. Third, our findings were obtained from community-based subjects and cannot be generalised to the whole middle-aged and elderly population in Taiwan. Fourth, we could not closely define the stages of smoking/alcohol consumption or the regularity of exercise. This is because these items were included in the questionnaire used in your study, which was designed for community participants during a health examination. Fifth, sarcopenia was not assessed in our study because hand grip and walking speed were not measured in our subjects in this project. The potential impact of sarcopenia may be an area for future work.

BMI, BF percentage and WC were all positively associated with HTN with statistical significance. Of the three indices, WC was the most reliable predictor of HTN. Thus, there is a strong implication that abdominal fat distribution has more influence on blood pressure than total BF amount among middle-aged and elderly populations. Thus, our findings may provide valuable information for clinicians to alert subjects in this age group regarding the increased risk of HTN.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank May Lu for her assistance in editing this manuscript and acknowledge the support of the Maintenance Project of the Center for Big Data Analytics and Statistics (Grant CLRPG3D0044) at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-AL was involved in writing of the manuscript. Y-JC, Y-CT, W-CY, W-CL and I-ST provided opinions about the study designs and help collect data. J-YC contributed conceived, designed and performed the experiments, collected and analysed the data, revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding: This study was supported by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (grants CORPG3C0171~3C0172, CZRPG3C0053, CORPG3G0021, CORPG3G0022).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by Chang-Gung Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board (102-2304B), and written informed consent was given by all the participants before enrolment.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Mathus-Vliegen EMH. Obesity and the elderly. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46:533–44. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31825692ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cetin DC, Nasr G. Obesity in the elderly: more complicated than you think. Cleve Clin J Med 2014;81:51–61. 10.3949/ccjm.81a.12165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. FdAGd V, Cordeiro BA, Rech CR, et al. . Sensitivity and specificity of the body mass index for the diagnosis of overweight/obesity in elderly. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2010;26:1519–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang K-T, Chen C-H, Chuang H-H, et al. . Which obesity index is the best predictor for high cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and elderly population? Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2018;78:165–70. 10.1016/j.archger.2018.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. David CN, de Mello RB, Bruscato NM, et al. . Overweight and abdominal obesity association with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the elderly aged 80 and over: a cohort study. J Nutr Health Aging 2017;21:597–603. 10.1007/s12603-016-0812-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng Y-H, Tsao Y-C, Tzeng I-S, et al. . Body mass index and waist circumference are better predictors of insulin resistance than total body fat percentage in middle-aged and elderly Taiwanese. Medicine 2017;96:e8126 10.1097/MD.0000000000008126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Setters B, Holmes HM. Hypertension in the older adult. Prim Care 2017;44:529–39. 10.1016/j.pop.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ker J. Hypertension in the elderly. Medical Chronicle 2018;2018:13 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pont L, Alhawassi T. Challenges in the management of hypertension in older populations. Hypertension: from basic research to clinical practice. Springer, 2016: 167–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jiang S-Z, Lu W, Zong X-F, et al. . Obesity and hypertension. Exp Ther Med 2016;12:2395–9. 10.3892/etm.2016.3667 10.3892/etm.2016.3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hu H, Wang J, Han X, et al. . Bmi, waist circumference and all-cause mortality in a middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. J Nutr Health Aging 2018;22:975–81. 10.1007/s12603-018-1047-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen X, Kong C, Yu H, et al. . Association between osteosarcopenic obesity and hypertension among four minority populations in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026818 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeMarco VG, Aroor AR, Sowers JR. The pathophysiology of hypertension in patients with obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014;10:364–76. 10.1038/nrendo.2014.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang X, Yao S, Sun G, et al. . Total and abdominal obesity among rural Chinese women and the association with hypertension. Nutrition 2012;28:46–52. 10.1016/j.nut.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu L, He Y, Jiang B, et al. . Association between waist circumference and the prevalence/control of hypertension by gender and different body mass index classification in an urban elderly population. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi= Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi 2015;36:1357–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Janghorbani M, Aminorroaya A, Amini M. Comparison of different obesity indices for predicting incident hypertension. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 2017;24:157–66. 10.1007/s40292-017-0186-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ononamadu CJ, Ezekwesili CN, Onyeukwu OF, et al. . Comparative analysis of anthropometric indices of obesity as correlates and potential predictors of risk for hypertension and prehypertension in a population in Nigeria. Cardiovasc J Afr 2017;28:92–9. 10.5830/CVJA-2016-061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Q, Xu L, Li J, et al. . Association of anthropometric indices of obesity with hypertension in Chinese elderly: an analysis of age and gender differences. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:801 10.3390/ijerph15040801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rhéaume C, Leblanc Marie-Ève, Poirier P. Adiposity assessment: explaining the association between obesity, hypertension and stroke. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2011;9:1557–64. 10.1586/erc.11.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Q, Wang Z, Yao W, et al. . Anthropometric indices predict the development of hypertension in normotensive and Pre-Hypertensive middle-aged women in Tianjin, China: a prospective cohort study. Med Sci Monit 2018;24:1871–9. 10.12659/MSM.908257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee J-W, Lim N-K, Baek T-H, et al. . Anthropometric indices as predictors of hypertension among men and women aged 40–69 years in the Korean population: the Korean genome and epidemiology study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:140 10.1186/s12889-015-1471-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stępień M, Stępień A, Banach M, et al. . New obesity indices and adipokines in normotensive patients and patients with hypertension. Angiology 2014;65:333–42. 10.1177/0003319713485807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sabbatini AR, Fontana V, Laurent S, et al. . An update on the role of adipokines in arterial stiffness and hypertension. J Hypertens 2015;33:435–44. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramezankhani A, Ehteshami-Afshar S, Hasheminia M, et al. . Optimum cutoff values of anthropometric indices of obesity for predicting hypertension: more than one decades of follow-up in an Iranian population. J Hum Hypertens 2018;32:838–48. 10.1038/s41371-018-0093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen X, Liu Y, Sun X, et al. . Comparison of body mass index, waist circumference, conicity index, and waist-to-height ratio for predicting incidence of hypertension: the rural Chinese cohort study. J Hum Hypertens 2018;32:228–35. 10.1038/s41371-018-0033-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luz RH, Barbosa AR, d'Orsi E. Waist circumference, body mass index and waist-height ratio: are two indices better than one for identifying hypertension risk in older adults? Prev Med 2016;93:76–81. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031660supp001.pdf (267.3KB, pdf)