Abstract

Introduction

The associations between smoking prevalence, socioeconomic group and lung cancer outcomes are well established. There is currently limited evidence for how inequalities could be addressed through specific smoking cessation interventions (SCIs) for a lung cancer screening eligible population. This systematic review aims to identify the behavioural elements of SCIs used in older adults from low socioeconomic groups, and to examine their impact on smoking abstinence and psychosocial variables.

Method

Systematic searches of Medline, EMBASE, PsychInfo and CINAHL up to November 2018 were conducted. Included studies examined the characteristics of SCIs and their impact on relevant outcomes including smoking abstinence, quit motivation, nicotine dependence, perceived social influence and quit determination. Included studies were restricted to socioeconomically deprived older adults who are at (or approaching) eligibility for lung cancer screening. Narrative data synthesis was conducted.

Results

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria. Methodological quality was variable, with most studies using self-reported smoking cessation and varying length of follow-up. There were limited data to identify the optimal form of behavioural SCI for the target population. Intense multimodal behavioural counselling that uses incentives and peer facilitators, delivered in a community setting and tailored to individual needs indicated a positive impact on smoking outcomes.

Conclusion

Tailored, multimodal behavioural interventions embedded in local communities could potentially support cessation among older, deprived smokers. Further high-quality research is needed to understand the effectiveness of SCIs in the context of lung screening for the target population.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018088956.

Keywords: smoking, smoking cessation, older, deprived, lung cancer, lung cancer screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There is a current gap in knowledge about the most suitable form of behavioural smoking cessation intervention (SCI) for older, deprived smokers who are most likely to be eligible for lung screening.

This systematic review suggests that tailored, multimodal behavioural SCIs could support smoking cessation for those most likely to be eligible for lung screening; however, the studies included in the review were heterogeneous in design, SCI modality, sample size, intervention timing and measurement of smoking abstinence.

There is a lack of rigorous, high quality research for the target population.

Introduction

Smoking is the leading global cause of death and disease1 and data show that there are approximately 7.4 million adult cigarette smokers in the UK2 3. Twenty-six per cent of smokers in the UK are aged 50 years or older3; these individuals tend to have long standing smoking histories, are often from deprived communities and are a population that are likely to be eligible for future lung screening implementation. The associations between smoking prevalence, socioeconomic group and a range of chronic disease outcomes, including lung cancer outcomes are well established, with higher smoking rates and greater lung cancer incidence and mortality4–6 among people living in deprived areas.

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends annual low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening for those who are high-risk heavy smokers, including adults aged 55–80 years old, with a 30 pack-year history7. LDCT lung cancer screening has the potential to prompt a smoking cessation attempt and evidence for integrated smoking cessation support is growing8–11, with research demonstrating promising results for quit rates when using a combined approach of smoking cessation support in a lung screening setting9.

Prior to implementing an appropriate smoking cessation intervention (SCI) in a lung screening context in the UK, it is important to understand the factors that influence cessation attempts in older, deprived smokers who may be eligible for lung cancer screening. Known barriers to smoking cessation in this population include higher nicotine dependence, less motivation to quit, more life stress, lack of social support and differences in perceptions of smoking12–14. Smokers from a low socioeconomic background may find quitting more difficult due to lack of support from their family members or community with quit attempts15, partly due to higher smoking prevalence and normalisation of smoking in their social networks16. Studies suggest that cessation attempts in older smokers are more likely to fail due to heavy nicotine dependence and insufficient motivating factors such as self-efficacy to quit17 18.

Using pharmacotherapy with structured behavioural support to assist smoking cessation has shown promise with disadvantaged smokers19 20. Intensive SCIs involving tailored pharmacotherapy and behavioural counselling to increase self-efficacy are most effective for deprived smokers.21 However, further research is needed to understand specific characteristics of behavioural SCIs, such as mode of delivery, setting, intensity and duration, that could be used for older, deprived smokers.

A recent review by Iaccarino et al 22 attempted to identify the best approach for delivering SCIs in a lung cancer screening setting and concluded that the optimal strategy remains unclear. There is a need to identify gaps in the evidence surrounding the optimal models for integrated smoking cessation in a lung screening setting, focusing specifically on a disadvantaged lung screening eligible population, as well as gain a better understanding of what form of SCI may work best for this population in the UK.

The aims of this systematic review were to identify the behavioural aspects of SCIs for older, deprived adults who are eligible (or approaching eligibility) for lung cancer screening, and to explore which elements of the interventions were most effective in reducing smoking abstinence and modifying psychosocial variables. The findings from the systematic review will contribute to further understanding of optimal SCIs for individuals who are a target population for lung cancer screening.

Methods

The systematic review was registered on PROSPERO and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines23. Throughout all stages of the search, data extraction and quality appraisal, 20% of studies were double-checked for consistency by another member of the team (RP). All discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Data duplication was managed by removing duplications using a reference management software package (EndNote X9), which were then manually checked.

Search strategy

The literature was searched from 1990 to November 2018 on electronic databases: Medline, EMBASE, PsychInfo and CINAHL. Search terms related to smoking cessation, SCIs and socioeconomic status were used (table 1). To limit restricting the search in relation to age, papers were manually screened to identify studies that used a relevant sample.

Table 1.

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) tool

| PICO | Description | Search terms and connectors |

| Population | Individuals from socioeconomically deprived groups, defined through either individual or area level indicators | (Depriv* or disadvantage* or inequit* or socioeconomic or socio-economic or sociodemographic or socio-demographic or social class or deprivation group or poverty or low income or social welfare).tw. |

| Intervention | A range of interventions including individual and group counselling, self-help materials, pharmacological interventions (eg, nicotine replacement therapy), social and environmental support, comprehensive programmes and incentives | Smoking Cessation/ and (intervention* or initiative* or strategy* or program* or scheme* or outcome* or approach*).tw. |

| Comparison | All study types with a pre-intervention/post-intervention and/or a control group | – |

| Outcome | Primary outcome: smoking abstinence Secondary outcome: moderating variables (eg, nicotine dependence, quit motivation, self-efficacy, social support and influences) |

((nicotine or tobacco or smok* or cigarette) adj (quit* or stop* or cess* or cease* or cut down or “giv* up” or reduc*)).tw. |

Study eligibility criteria

All searches were restricted to high-income countries24. Inclusion criteria for the included publications were; ‘Socioeconomically deprived groups’ that defined their sample through individual level indicators (eg, educational level, income) or area level indicators (eg, postcode). ‘Older adults’, defined as aged 50 years+ (or when the majority of the sample was aged 40+) were included to represent a sample at or approaching lung cancer screening age25. The review included studies that examined behavioural aspects of SCIs and outcomes including smoking abstinence and psychosocial variables such as quit motivation, nicotine dependence, perceived social influence and quit determination.

Data extraction and synthesis

Study outcomes, including moderating variables and selected study features were extracted. Where relevant, statistical associations between variables are described in order to examine relationships within and between the included studies. Data from qualitative elements of included studies were extracted and a narrative synthesis was conducted. Due to the heterogeneity of included studies, a narrative synthesis was performed using guidance outlined by Popay e t al 26 and organised under relevant behavioural intervention elements.

Critical appraisal

The methodological quality of included studies and risk of bias was assessed using an adapted Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool27. Quality was assessed according to each domain on the checklist including rationale, study design, recruitment, sample size, data collection and analysis, ethical issues, reporting of findings and contribution to research. The CASP tool was adapted to address quality of methods for verifying smoking abstinence, intervention type, and socioeconomic and age variation within the sample. Overall quality was categorised as high, medium or low.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was not adopted for the review.

Results

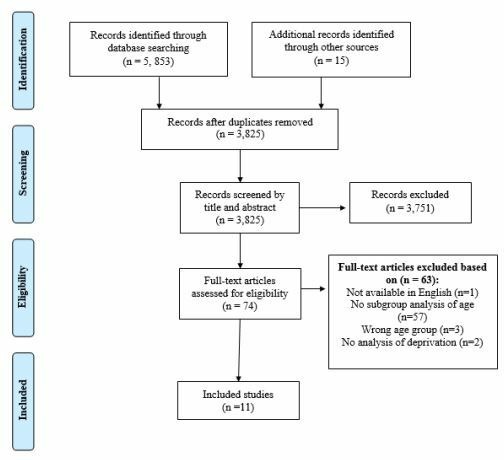

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria (figure 1). Nine of the 11 studies were quantitative28–36 and two were mixed-methods design37 38. Three studies were randomised control trials, with the remaining using a range of non-randomised designs. Two studies28 34 were conducted in a lung screening context. Quality of included studies was high (n=2), medium (n=5) and low (n=4). Limitations of lower quality studies included measuring but not reporting a subgroup analysis of age and/or deprivation, study design, limited description of the intervention and statistically underpowered results. Where available, relevant statistical values are presented in table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2.

Study characteristic

| Study (country) | Study design | Sample | Intervention | Measure of smoking abstinence | Summary of findings | Quality appraisal |

| Bade et al (2016) (Germany)28 |

Randomised controlled trial | 4052 participants from the German lung cancer screening intervention trial. 1535 (62%) male, 950 (38%) female. 1737 (70%) aged 50–59 years, 748 (30%) 60–69 years old. 1823 (73%) ‘low’ in education and 1594 (65%) ‘low’ in vocational training. |

Low-dose multislice CT screening and smoking cessation counselling delivered by a psychologist in a radiology department. 20-minute counselling followed by at least one telephone call. | Self-report at 12 and 24 months | Proportion of current smokers decreased among screenees (3.4%, p<0.0001), controls (4.5%, p<0.0001), and entire cohort (4.0%, p<0.0001). The magnitude of decrease in smoking rate was larger in SSC participants (screenees 9.6%, p<0.0001; controls 10.4%, p<0.0001) compared with non-SSC participants (screenees 0.8%, p=0.30; controls 1.6%, p=0.03). | High |

| Bauld et al (2009) (UK)29 |

Observational study | 1785 pharmacy service users. 762 (56%) in the Starting Fresh (SF) group and 311 (76%) in the Smoking Concerns (SC) group were aged 41 years or older. 796 (58%) from SF were in the lowest deprivation quintile, 187 (46%) from SC were in the lowest quintile. |

Behavioural support delivered by a trained adviser in a group-based community setting (SC) up to 12 weeks or individually in a pharmacy setting (SF) up to 12 weeks, with access to nicotine replacement therapy. | Biochemical validation at 1 month | 146 (36%) quit rate in SC versus 255 (19%) in SF (OR=1.98; 95% CI 1.90 to 3.08). SC and SF deprived smokers had lower cessation rates (OR=0.677; p=0.015). Cessation rate for pharmacy clients increased sharply with age from 13.4% for age 16–40% to 30.7% for age 61 and over (p<0.001). The increase for group-based clients (SC) was statistically insignificant (p<0.25). Determination to quit was not statistically significant: p=0.072 (SF) and p=0.092 (SC). | Medium |

| Celestin et al (2016) (USA)30 |

Retrospective cohort study | 8549 tobacco users in Louisiana’s public hospital facility. 1531 (68%) in the intervention group were aged 45 years and over. 1196 (57%) were from the lowest ‘financial class’. |

Standard care plus group behavioural counselling in a hospital classroom. 4 1hour sessions, once a week within a 1month period. | Self-report at 12 months | Intervention participants had greater odds of sustained abstinence than non-attendees (AOR=1.52; 95% CI 1.21 to 1.90). Higher 12-month quit rate in patients over age 60 (22%) compared with 18–30 years old (11%) (AOR 2.36; 95% CI 1.58 to 3.52). There was a statistically significant effect of COPD status on quit rate (from UOR 1.01 CI 0.86 to 1.19, to aOR 0.75 CI 0.63 to 0.90). |

Low |

| Copeland et al (2005) (UK)31 |

Observational cohort study | 101 patients from a disadvantaged area of Edinburgh. Mean age for males was 47 years and for females was 44 years. | General practitioner consultation and subsequent prescription of nicotine replacement therapy. | Self-report at 3 months | Post intervention 35 (35%) smoked the same, 46 (45%) were smoking less and 20 (20%) had stopped smoking. Older participants were more likely to have stopped or to be smoking less (p<0.00). |

Low |

| Lasser et al (2017) (USA)32 |

Prospective, randomised trial | 352 participants randomised (177 intervention, 175 control). 197 (56%) aged 51–74. 193 (55%) with a household yearly income <US$20 000. |

Patient navigation and financial incentive (intervention) versus enhanced traditional care (control). Intervention received 4 hours of support over 6 months. Delivered by patient navigators over the phone or in-person. | Biochemical validation at 12 months | 21 (12%) intervention participants quit smoking compared with four (2%) control participants (OR=5.8, 95% CI 1.9 to 17.1, p<0.00). In the intervention arm (n=177), participants aged 51–74 had higher quit rates compared with those aged 21–50 (19(19.8%) vs 2(2.0%); p<0.00). Household yearly income of <US$20 000 had higher quit rates compared with >US$20 000 (15(15.5%) vs 4(8%); p=0.00). |

Medium |

| Neumann et al (2013) (Denmark)33 |

Observational prospective cohort study | 20 588 disadvantaged patients (low level of education and receiving unemployment benefits). 15 244 (74%) aged 40 years or over. |

6-week manualised Gold Standard Programme in hospitals and primary care facilities (eg, pharmacies). Delivered in five meetings over 6 weeks by a certified staff member. Both group and individual counselling was offered. | Self-reported continuous abstinence at 6 months | 34% of responders reported 6 months of continuous abstinence. Continuous abstinence was significantly lower in those with less education (30%) versus more education (35%) (p<0.00). For participants with a lower educational level, individual counselling was a predictor of success in smoking cessation (OR=1.31, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.63). |

Medium |

| Ormston et al (2015) (UK)37 |

Mixed-methods, quasi-experimental study | 2042 smokers living in deprived areas of Dundee. 70 (54%) aged 45 years and over. 119 (92%) from the two most deprived areas. | Financial incentive and behavioural support based on Scottish national guidelines, with pharmacotherapy (Quit4u Scheme) delivered in group (practice nurses) and one-to-one settings (community pharmacists) for up to 12 weeks. | Biochemical validation at 1, 3 and 12 months | Intervention was responsible for 36% of all quit attempts in the three most deprived areas. 12-month quit rate (9.3%) was significantly higher than other Scottish stop smoking services (6.5%) (relative difference 1.443, 95% CI 1.132 to 1.839, p=0.00). | Medium |

| Park et al (2015) (USA)34 |

Matched case control study | 3336 National Lung Screening Trial participants. Aged 55–74 years old. No report of deprivation at baseline. Subgroup analysis performed for education. |

SCI delivered by a primary care clinician using the 5As. | Self-report at 12 months | Assist was associated with a 40% increase in quitting (OR=1.40, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.63). Arrange was associated with a 46% increase in quitting (OR=1.46, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.79). Higher educational level was significantly associated with quitting after delivery of each of the 5As (ORs=1.14 to 1.26 for college degree or higher versus high school education). Lower nicotine dependence (OR=0.94, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.98), and higher quit motivation (OR=1.28, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.35) were significantly associated with quitting after delivery of each of the 5As | Medium |

| Sheffer et al (2013) (USA)35 |

Observational study | 7267 participants in telephone treatment: 30% aged >50 years, 35% aged 36–49 years. In-person participants: 38% aged >50 years, 38% aged 36–49 years. No report of deprivation at baseline. Subgroup analysis performed for deprivation. |

Behavioural counselling- manual driven sessions delivered weekly in-person (healthcare settings) or over the telephone, with free nicotine patches for 6 weeks. Delivered by a healthcare provider trained in brief evidence-based tobacco dependence interventions. | Self-report at 3 and 6 months | Abstinence rates were higher for in-person counselling (37.7%) versus telephone counselling (30.8%) (p<0.00). No significant difference at 3 months (p=0.73) and 6 months (p=0.27) between in-person (28.2%; 27.2%) and telephone (28.7%; 28.7%). The highest socioeconomic (SES) group was more likely to be abstinent with telephone treatment (SES3: p=0.03; OR=1.45; 95% CI 1.04 to 2.01). No significant differences between the in-person and telephone for the two lower SES groups (SES1: OR=1.02, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.18, p=0.82; SES2: OR=0.91, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.15, p=0.41). | Low |

| Sheikhattari et al (2016) (USA)36 |

Randomised controlled trial | 409 (52%) were aged 48 years and over. Recruited in targeted communities where more than 40% of the households earn less than US$25 000. 531 (72%) were unemployed. |

Peer-led community-based intervention over three phases. Phase 1 (n=404)—the American Cancer Society’s 4-week Fresh Start smoking cessation curriculum expanded to 12 weeks at health centres and delivered by a doctor, nurse or social worker. Phase 2 (n=398) and Phase 3 (n=163)—tailored group counselling in community venues, delivered by trained peer motivators. |

Self-report and biochemical validation at 3 and 6 months | Delivery of services in community settings was a predictor of quitting (OR=2.6, 95% CI 1.7 to 4.2). Smoking cessation increased from 38 (9.4%) in Phase 1 to 84 (21.1%) in Phase 2, and 49 (30.1%) in Phase 3. Phases 2 and 3 were associated with higher odds compared with Phase 1, with adjusted ORs of 2.1 (95% CI 1.3 to 3.5) and 3.7 (95% CI 2.1 to 6.3) respectively. Older age (>48 years versus <48 years) was associated with higher quit rate (13.3% vs 19.1%, p=0.028). | High |

| Stewart et al (2010) (Canada)38 |

Pilot evaluation of a before and after study | 44 women, aged 25–69, living on low income in urban areas of Western Canada. 23 (52%) aged 40 years or older. 18 (39%) participants unemployed, 26 (62%) on welfare/income support. |

Facilitated group support supplemented with one-to-one support from a mentor. Once a week, duration of 12 weeks minimum. Groups facilitated by professionals and former smokers with the option of one-to-one from peers in community centres. | Self-report at 3 months | The mean number of cigarettes smoked daily decreased from pre to post-test (p=0.00). Among women completing all data collection (n=22), the mean number of cigarettes consumed daily decreased from 0.95 preintervention to 0.32 immediately after the intervention, then increased to 0.64 at 3 months postintervention. Four women reported sustained cessation. | Low |

AOR, Adjusted odds ratio; 5As, ask, advise, assess, assist and arrange follow-up; CI, Confidence interval; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OR, Odds ratio; UOR, Unadjusted odds ratio.

Nine studies used a combination of nicotine replacement therapy and behavioural counselling28–30 32–37. One study used only nicotine replacement therapy31 and one used behavioural counselling without nicotine replacement therapy38. Results are presented in relation to intervention elements including the behavioural content, setting, intervention provider and mode and duration of delivery. A subheading under each intervention element presents data on smoking outcomes. Further study characteristics and findings are also presented in table 2.

Behavioural intervention content

Ten studies focused on meeting the individual participant’s needs using education and motivational techniques including support and encouragement28–30 32–38. In all 10 studies, the interventions involved used motivational techniques with varying levels of intensity (table 2).

Nine studies used interventions that were of higher intensity28–30 32 33 35–38. These studies involved incorporating specific action planning, tailored by the participant’s level of quit motivation28, using a combination of manual-based teaching and patient education sessions including relapse prevention modules36, motivational interviewing techniques32, discussions on the benefits and costs of smoking versus cessation33, empowering strategies to enhance self-efficacy38 and cognitive behavioural content35.

Three studies used financial incentives as part of their intervention32 36 37. A randomised control trial conducted by Lasser et al 32 offered participants $750 for abstinence at 12-month follow-up. This element of the intervention was combined with patient navigation in which trained navigators identified and discussed salient social contextual factors using motivational interviewing. Ormston et al 37 combined behavioural support with financial incentives to participants on biochemically verified cessation.

Outcomes

A study by Park et al 34 found that the ‘assist’ and ‘arrange follow-up’ elements of a brief SCI based on the 5As (ask, advise, assess, assist and arrange follow-up) alongside lung cancer screening significantly increased the odds of quitting. Results showed that the decrease in smoking rate was larger for participants who received behavioural support compared with those who did not. Smoking abstinence was higher in participants with a higher educational level (table 2).

Studies of interventions that involved using financial incentives found that older participants and those with the lowest income had higher quit rates (table 2). Ormston et al 37 found that quit rates for the intervention group were significantly higher compared with other stop smoking services (table 2). Seventy-one percent of participants reported that the incentive component was ‘very’ or ‘quite useful’ in helping them quit, with participants describing it as a ‘bonus’ or ‘reward’ to motivate them.

Stewart et al 38 reported qualitative data on self-efficacy for quitting and found that participants thought the education they gained from the intervention increased their awareness of their smoking habits, reasons why they smoked and the importance of quitting. Participants also reported an increase in the number of available support sources (eg, parents, spouse and friends) along with a significant increase in perceived social support38.

Setting

Two studies took place in a lung screening setting28 34 and used contrasting forms of interventions. Park et al 34 offered a brief SCI delivered by a primary care clinician, whereas Bade et al 28 used a more intensive intervention delivered by a psychologist who was trained in tobacco treatment. The latter study used a randomised control trial design with a large sample size and took place in the radiology department before or after the participant’s screening.

Five studies were delivered in a variety of easily accessible community settings including community pharmacies29 33 37 and community venues such as centres and churches29 36–38 (table 2). Three studies took place at medical facilities such as local medical/health centres31 32 35 and two studies took place in hospitals30 33. One study delivered the intervention in both community and primary care settings33.

Outcomes

Stewart et al 38 used a community-based intervention that took place in a local community centre, familiar to participants. Findings from this small-scale pilot study of female smokers suggested that the number of cigarettes smoked decreased post-intervention (table 2). Ormston et al 37 compared intervention delivery in community pharmacies and behavioural support (both group and one-to one sessions) to other stop smoking services and demonstrated significantly higher quit rates in deprived communities (table 2).

Bauld et al 29 showed that specialist-led group-based services have higher quit rates compared with one-to-one services that are provided by pharmacies. Cessation rates for pharmacy clients increased with age, and more deprived smokers had lower smoking cessation rates in both the pharmacy-led and one-to-one services (table 2). Sheikhattari et al 36 found higher quit rates for community-based participants compared with those receiving support in clinics during phase 1 of the intervention (table 2). Results from this study also showed that older age (defined as over 48 years) was associated with higher quit rates for participants.

Provider

Interventions were delivered by a range of providers (table 2). Seven studies employed healthcare professionals such as general practitioners, primary care practice nurses, psychologists and pharmacists28 30 31 33–35 38. Two studies employed trained peer motivators to deliver their intervention. Sheikhattari et al 36 used peer motivators who were former smokers to deliver the behavioural sessions. Peer motivators lived or worked in the community and were trained in delivering the intervention. Lasser et al 32 used patient navigators who had completed 10 hours of training in motivational interviewing techniques and had experience of working in community settings.

Outcomes

Smoking abstinence outcomes varied according to SCI provider (table 2). A small-scale observational study by Copeland et al 31 examined the use of nicotine replacement theory and a brief general practitioner consultation. Results showed that older smokers were more likely to have stopped smoking (table 2).

Sheikhattari et al 36 demonstrated that subsequent phases of the intervention delivered by trained peer facilitators were associated with higher odds of quitting compared with the first phase where intervention delivery was conducted by a doctor, nurse or social worker (table 2). Findings from Lasser et al 32 demonstrated that older participants and those with a lower household yearly income had higher quit rates (table 2).

Qualitative data from Stewart et al 38 demonstrated that participants felt peer facilitators helped to support their cessation efforts as they were able to share personal experiences and strategies. Participants reported that they were able to learn coping strategies and techniques from other participants in the group which then helped them with their quit attempt.

Mode and duration

Studies varied in the mode and duration of delivery of SCIs (table 2). Seven studies examined both individual and group behavioural counselling sessions29 30 32 33 35 37 38 (table 2) and four studies used only one-to-one behavioural support28 31 32 34. Duration of interventions varied greatly between and within studies (table 2). The shortest duration was an intervention embedded in a general practitioner consultation31 and the longest was 16 weeks of smoking cessation support38.

Outcomes

Bauld et al 29 showed that participants accessing group-based services were almost twice as likely as those who used individual pharmacy-based support to have quit smoking at 4 weeks (table 2). Similarly, Celestin et al 30 showed that attendees of group behavioural counselling had significantly higher long-term quit rates compared with non-attendees. Sheikhattari et al 36 used a six-week group-counselling module followed by a six-week relapse prevention module. Higher odds of quitting were associated with later phases of the intervention in which community-based group counselling was delivered (table 2).

Lasser et al 32 delivered their one-to-one behavioural support over 6 months either in-person or over the telephone, with a goal of four hours per participant. Results demonstrated that more participants from the intervention group had quit smoking in comparison to the control group (table 2). Bade et al 28 also employed behavioural counselling in-person, with at least one subsequent telephone call for those who had specified a quit date. Participants were offered four telephone calls that lasted around 20 minutes in duration and findings demonstrated a larger decrease in smoking for screening attendees compared with non-attendees (table 2).

Sheffer et al 35 delivered both telephone and in-person behavioural counselling. Smoking abstinence rates were higher for in-person counselling, with smokers from higher socioeconomic groups more likely to quit after telephone counselling than smokers from lower socioeconomic groups. Neumann et al 33 offered either group or individual counselling and demonstrated that for those with a lower educational level, individual counselling was a predictor of smoking cessation (table 2).

Moderating variables

Seven studies reported limited data on moderating variables28–30 32 34–36. Bauld et al 29 found that smokers who reported being ‘extremely determined’ to quit were more likely to be successful in their quit attempt. Celestin et al 30 demonstrated that COPD status had a statistically significant effect on quit rates (table 2) and Park and colleagues34 showed that lower nicotine dependence and higher quit motivation were significantly associated with quitting after the delivery of each of the 5As. Three RCTs demonstrated that participants who had a lower Fagerstrom score36, who were contemplating quitting32 and reported high readiness to quit28 at baseline were more likely to have abstained from smoking post-intervention.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to examine the influence of behavioural SCIs for an older, deprived population. The majority of included studies used a combination of pharmacotherapy and a form of behavioural counselling, supporting previous evidence that a combined approach is the most effective for older, deprived smokers21. Additionally, findings relating to the intensity, provider, mode, duration and setting of behavioural counselling are encouraging. Behavioural counselling delivered in a community setting and tailored to individual needs appeared to demonstrate a positive impact on smoking cessation outcomes.

Behavioural interventions identified in the current review used a range of approaches and although none of the included studies explicitly described their intervention as ‘tailored’, many used a form of behavioural counselling that was implicitly flexible according to the needs of the individuals. Interventions were implemented in locations that addressed barriers to access, such as local community centres, and intervention content was driven by the individual’s psychological needs29 36–38. Previous research suggests that in order for people to access stop smoking services, the appointments should be flexible and accessible39.

The optimal mode and duration of intervention was unclear from our review, with findings suggesting varying success for both group and one-to-one behavioural support. The current results reflect similar findings from a review conducted in the UK. Bauld et al 21 concluded that due to a dearth of studies examining subpopulations of smokers, further research is needed to determine the most effective models of treatment for smoking cessation and their efficacy with these subgroups21. The current review did, however, demonstrate that certain aspects of behavioural interventions, such as incentives, the use of peer facilitators and more intensive counselling are promising for encouraging cessation in older, deprived smokers. Additionally, limited data regarding the influence of moderating variables suggests that factors such as nicotine dependence, quit motivation and pre-existing health conditions such as COPD can impact the effectiveness of SCIs. Future research should aim to understand the needs and preferences of older, deprived smokers and focus on psychosocial mechanisms that can be targeted in more holistic level interventions.

The 11 studies included in the review were heterogeneous in design, SCI modality, sample size, intervention timing and measurement of smoking abstinence. Some of the included studies did not report CIs, thus making it difficult to interpret findings. Only three of the studies included were randomised control trials, of which one was underpowered32, thus the effectiveness results across the studies were modest. Chen and Wu40 also identified the need for controlled trials of SCIs for older smokers, in order to better understand the most suitable form of intervention for this population. Similarly, to findings from Piñeiro et al’s systematic review41, the studies in the current review did not consistently use biochemical verification of smoking cessation, with most relying on self-reported smoking cessation (table 2).

Various design aspects of the included studies, including the use of non-randomised methods, limited the extent to which firm conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of behavioural SCIs for older, deprived smokers. Only two studies included qualitative process evaluation data, limiting the ability to understand why specific intervention characteristics were more or less likely to influence smoking cessation outcomes. Evidence suggests that smokers from disadvantaged backgrounds face particular obstacles to successful quitting such as lack of support, higher nicotine dependence and life stress20. Further mixed-methods research is therefore warranted to understand why some forms of SCI support may be more suited to mitigating these barriers in the target population.

The findings indicate a clear lack of evidence from large-scale trials of effectiveness in a lung screening context as well as a lack of data reporting psychosocial moderators of cessation for older, deprived smokers. We acknowledge methodological limitations of the present systematic review. By restricting the inclusion criteria for age and socioeconomic group, several potentially relevant studies were excluded. For example, telephone-based counselling for smokers undergoing lung cancer screening, involving messages about risks of smoking in the context of lung scan results, can improve self-efficacy for quitting and the likelihood of a successful quit attempt42. However, our review highlights the current absence of robust evidence regarding behavioural SCIs that are effective for the lung screening eligible population of older, deprived smokers.

Conclusion

Our systematic review demonstrates the potential for tailored, multimodal SCIs for older, deprived smokers that can be embedded within disadvantaged communities. With the prospect of lung cancer screening being implemented in the UK and Europe in the near future, this research adds to the evidence base regarding promising SCIs for older, deprived populations who will benefit most from lung screening and integrated smoking cessation support. Further studies to understand the psychosocial barriers to quitting in the target population should be conducted to inform the design and conduct of high-quality trials of intervention effectiveness in older, deprived smokers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Grace McCutchan for her support and guidance throughout the review process.

Footnotes

Twitter: @SysReviews, @annmarie0

Contributors: PS, KB, MM, AN and GM were responsible for the concept, overall design and conduct of the review. MM gave additional support and advice on methodology including the search strategy. PS was responsible for collection of data and manuscript preparation. RP double checked 20% of included abstracts and full-texts. RP, MM, AN, GM and KB reviewed the edited manuscript preparation. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by School of Medicine, Cardiff University. RP is funded by a Cancer Research UK Population Research Committee Post-Doctoral Fellowship. AN's and MM’s posts are supported by Marie Curie core grant funding (grant reference: MCCCFCO-11-C).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation Report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008. Available: www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/en/

- 2. Office for National Statistics Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2017, 2018. Available: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/bulletins/adultsmokinghabitsingreatbritain/2017 [Accessed cited 2019 February].

- 3. Office for National Statistics Adult smoking habits in Great Britian 2017, 2017. Available: http://ash.org.uk/category/information-and-resources/fact-sheets/

- 4. Information Services Division (ISD) Nhs national services Scotland, 2012. Available: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Cancer/Publications/2012-04-24/2012-04-24-Cancer-Incidence-report.pdf?49042910338

- 5. Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unit Public health Wales 2015.

- 6. Shack L, Jordan C, Thomson CS, et al. Variation in incidence of breast, lung and cervical cancer and malignant melanoma of skin by socioeconomic group in England. BMC Cancer 2008;8:271 10.1186/1471-2407-8-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the U.S. preventive services Task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:411–20. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ashraf H, Tønnesen P, Holst Pedersen J, et al. Effect of CT screening on smoking habits at 1-year follow-up in the Danish lung cancer screening trial (DLCST). Thorax 2009;64:388–92. 10.1136/thx.2008.102475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brain K, Carter B, Lifford KJ, et al. Impact of low-dose CT screening on smoking cessation among high-risk participants in the UK lung cancer screening trial. Thorax 2017;72:912–8. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tammemägi MC, Berg CD, Riley TL, et al. Impact of lung cancer screening results on smoking cessation. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106 10.1093/jnci/dju084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van der Aalst CM, van den Bergh KAM, Willemsen MC, et al. Lung cancer screening and smoking abstinence: 2 year follow-up data from the Dutch-Belgian randomised controlled lung cancer screening trial. Thorax 2010;65:600–5. 10.1136/thx.2009.133751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bryant J, Bonevski B, Paul C. A survey of smoking prevalence and interest in quitting among social and community service organisation clients in Australia: a unique opportunity for reaching the disadvantaged. BMC Public Health 2011;11:827 10.1186/1471-2458-11-827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hiscock R, Judge K, Bauld L. Social inequalities in quitting smoking: what factors mediate the relationship between socioeconomic position and smoking cessation? J Public Health 2011;33:39–47. 10.1093/pubmed/fdq097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vangeli E, West R. Sociodemographic differences in triggers to quit smoking: findings from a national survey. Tob Control 2008;17:410–5. 10.1136/tc.2008.025650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chandola T, Head J, Bartley M. Socio-Demographic predictors of quitting smoking: how important are household factors? Addiction 2004;99:770–7. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00756.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mermelstein R, Cohen S, Lichtenstein E, et al. Social support and smoking cessation and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol 1986;54:447–53. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Benowitz NL. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2295–303. 10.1056/NEJMra0809890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. public health service clinical practice guideline executive summary. Respir Care 2008;53:1217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bauld L, Judge K, Platt S. Assessing the impact of smoking cessation services on reducing health inequalities in England: observational study. Tob Control 2007;16:400–4. 10.1136/tc.2007.021626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, et al. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1248:107–23. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bauld L, Bell K, McCullough L, et al. The effectiveness of NHS smoking cessation services: a systematic review. J Public Health 2010;32:71–82. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iaccarino JM, Duran C, Slatore CG, et al. Combining smoking cessation interventions with LDCT lung cancer screening: a systematic review. Prev Med 2019;121:24–32. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The World Bank [cited October 2018] High income, 2018. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/income-level/high-income

- 25. Oudkerk M, Devaraj A, Vliegenthart R, et al. European position statement on lung cancer screening. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:e754–66. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30861-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Popay JR, HMSowden, Petticrew A. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in sytematic reviews: Institute for health research, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singh J. Critical appraisal skills programme. CASP appraisal tools, 2013: 76 p. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bade M, Bahr V, Brandt U, et al. Effect of smoking cessation counseling within a randomised study on early detection of lung cancer in Germany, 2016: 959–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bauld L, Chesterman J, Ferguson J, et al. A comparison of the effectiveness of group-based and pharmacy-led smoking cessation treatment in Glasgow, 2009: 308–16 2009 Feb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Celestin MD, Tseng TS, Moody-Thomas S, et al. Effectiveness of group behavioral counseling on long-term quit rates in primary health care. Translational Cancer Research 2016;5:972–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Copeland L, Robertson R, Elton R. What happens when GPs proactively prescribe NRT patches in a disadvantaged community. Scott Med J 2005;50:64–8. 2005 May 10.1177/003693300505000208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lasser KE, Quintiliani LM, Truong V, et al. Effect of patient navigation and financial incentives on smoking cessation among primary care patients at an urban safety-net Hospital: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1798–807. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neumann T, Rasmussen M, Ghith N, et al. The gold standard programme: smoking cessation interventions for disadvantaged smokers are effective in a real-life setting. Tob Control 2013;22:e9 2013 Nov 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Park ER, Gareen IF, Japuntich S, et al. Primary care provider-delivered smoking cessation interventions and smoking cessation among participants in the National lung screening trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1509–16. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sheffer C, Stitzer M, Landes R, et al. In-person and telephone treatment of tobacco dependence: a comparison of treatment outcomes and participant characteristics. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e74–82. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sheikhattari P, Apata J, Kamangar F, et al. Examining smoking cessation in a community-based versus clinic-based intervention using community-based participatory research. J Community Health 2016;41:1146–52. 2016 Dec 10.1007/s10900-016-0264-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ormston R, van der Pol M, Ludbrook A. quit4u: the effectiveness of combining behavioural support pharmacotherapy and financial incentives to support smoking cessation, 2015: 121–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stewart MJ, Kushner KE, Greaves L, et al. Impacts of a support intervention for low-income women who smoke. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:1901–9. 2010 Dec 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Venn A, Dickinson A, Murray R, et al. Effectiveness of a mobile, drop-in stop smoking service in reaching and supporting disadvantaged UK smokers to quit. Tob Control 2016;25:33–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen D, Wu L-T. Smoking cessation interventions for adults aged 50 or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;154:14–24. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Piñeiro B, Simmons VN, Palmer AM, et al. Smoking cessation interventions within the context of low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening: a systematic review. Lung Cancer 2016;98:91–8. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zeliadt SB, Greene PA, Krebs P, et al. A proactive Telephone-Delivered risk communication intervention for smokers participating in lung cancer screening: a pilot feasibility trial. J Smok Cessat 2018;13:137–44. 10.1017/jsc.2017.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.