Abstract

Mammalian cell entry (mce) genes are the components of the mce operon and play a vital role in the entry of Mycobacteria into the mammalian cell and their survival within phagocytes and epithelial cells. Mce operons are present in the DNA of Mycobacteria and translate proteins associated with the invasion and long-term existence of these pathogens in macrophages. The exact mechanism of action of mce genes and their functions are not clear yet. However, with the loss of these genes Mycobacteria lose their pathogenicity. Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), the etiological agent of Johne’s disease, is the cause of chronic enteritis of animals and significantly affects economic impact on the livestock industry. Since MAP is not inactivated during pasteurization, human population is continuously at the risk of getting exposed to MAP infection through consumption of dairy products. There is need for new candidate genes and/or proteins for developing improved diagnostic assays for the diagnosis of MAP infection and for the control of disease. Increasing evidences showed that expression of mce genes is important for the virulence of MAP. Whole-genome DNA microarray representing MAP revealed that there are 14 large sequence polymorphisms with LSPP12 being the most widely conserved MAP-specific region that included a cluster of six homologs of mce-family involved in lipid metabolism. On the other hand, LSP11 comprising part of mce2 operon was absent in MAP isolates. This review summarizes the advancement of research on mce genes of Mycobacteria with special reference to the MAP infection.

Keywords: mce operon, Mycobacteria, protein, diagnosis, MAP, MTB, Johne’s disease

1. Introduction

Mammalian cell entry (mce) operons are present in the DNA of Mycobacteria and translate proteins associated with the invasion and long-term existence of this pathogen in macrophages (Mohn et al. 2008; Senaratne et al. 2008; Zhu et al. 2008; Zhang and Xie 2011; Rathor et al. 2013; Rodriguez et al. 2015). The mce genes are also present in other species like Nocardia, Janibacter, Nocardiodes, Amycolatopsis and Streptomyces (Table 1) as well as in Gram-negative bacteria and have also been found encoded in plant genomes. In Gram-negative bacteria, a 98 amino acid sub-region of ‘Mce-like’ protein domain as part of the inner membrane lipid-binding proteins (PF02470) are widely distributed (Casali and Riley 2007; Isom et al. 2017). An operon is a functional unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The mce operon was first discovered while studying the entry of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) inside host non-phagocytic cells (Ahmad et al. 2005; Timms et al. 2015). Arruda et al. (1993) first reported that a DNA fragment of MTB, namely H37Ra, conferred on a nonpathogenic Escherichia coli the ability to enter macrophage cells and was termed as mce gene (Kumar et al. 2003; Marjanovic et al. 2010; Zhang and Xie 2011). A total of 45 vital cell surface (exposed) antigens of Mycobacteria have been listed in Table 2 of which 6 are mce proteins. Although mce genes have been reported in many bacterial species, these genes exist as operons in Mycobacteria only (Timms et al. 2015). The mce operons encode sets of invasion/adhesion like proteins all predicted to contain hydrophobic stretches or signal sequences near the N-terminus. Their location on the Mycobacterial cell surface is in line with the potential role of mce operons in mammalian cell invasion, hence regarded as important virulence attributes (Harboe et al. 2004; Ahmad et al. 2005; Gioffre et al. 2005; Semret et al. 2005; Rodriguez et al. 2015). As the mce genes are absent in the human genome, these genes might also be represented as ideal candidates for drug targets (Zhang and Xie 2011).

Table 1.

Distribution of mce genes within the order Actinomycetales.

| Suborder | Family | Species | mce | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corynebacterineae | Mycobacteria ceae | M. leprae TN | 6 | UniProt |

| M. bovis AF2122/97 | 18 | UniProt | ||

| MTB CDC1551 | 24 | TIGR | ||

| MTB H37Rv | 24 | TIGR | ||

| Mycobacterium paratuberculosis K-10 | 48 | UniProt | ||

| M. smegmatis MC2 155 | 34 | TIGR | ||

| Mycobacterium sp. MCS | 38 | JGI | ||

| Mycobacterium sp. KMS | 38 | JGI | ||

| Mycobacterium sp. JLS | 50 | JGI | ||

| Mycobacterium flavescens PYR-GCK | 48 | UniProt | ||

| Mycobacterium vanbaalenii PYR-1 | 66 | UniProt | ||

| Nocardiaceae | N. farcinica IFM 10152 | 36 | UniProt | |

| Micrococcineae | Intrasporangiaceae | Janibacter sp. HTCC2649 | 6 | NCBI |

| Propionibacterineae | Nocardioidaceae | Nocardioides sp. JS614 | 12 | UniProt |

| Pseudonocardineae | Pseudonocardiaceae | Amycolatopsis mediterranei | 6 | Pfam |

| Streptomycineae | Streptomycetaceae | Streptomyces avermitilis MA-4680 | 6 | UniProt |

| S. coelicolor A3(2) | 6 | UniProt |

Table 2.

List of MAP cell surface proteins and their functions.

| S. No. | Mycobacterium structural proteins | Functions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MAP2189 | Mammalian cell entry proteins |

| 2 | MAP2190 | |

| 3 | MAP2191 | |

| 4 | MAP2192 | |

| 5 | MAP2193 | |

| 6 | MAP2194 | |

| 7 | MAP3567 | Hypothetical protein |

| 8 | MAP1508 | Hypothetical protein |

| 9 | MAP 0047c | Lpp-LpqN family conserved in Mycobacteria ceae |

| 10 | MAP0209c | Protein potentially involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis in MAP |

| 11 | MAP3936 | Chaperonin GroEL |

| 12 | MAP4143 | Elongation factor Tu |

| 13 | MAP3024c | HupB |

| 14 | MAP3651c | FadE3_2 |

| 15 | MAP1997 | Acyl carrier protein |

| 16 | MAP3968 | Heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin-like protein |

| 17 | MAP1122 | MIHF |

| 18 | MAP1589c | Alkylhydroperoxidase C |

| 19 | MAP1506 | Hypothetical protein |

| 20 | MAP3362c | S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase |

| 21 | MAP1519 | Hypothetical protein |

| 22 | MAP2698c | DesA2 DesA2 |

| 23 | MAP1998 | 3-oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase II |

| 24 | MAP3840 | Molecular chaperone DnaK |

| 25 | MAP4264 | co-chaperonin GroES |

| 26 | MAP3693 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase |

| 27 | MAP1563c | Hypothetical protein |

| 28 | MAP0398c | Probable transcriptional regulatory protein |

| 29 | MAP0896 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase subunit beta |

| 30 | MAP0966c | Hypothetical protein |

| 31 | MAP3033c | SerA |

| 32 | MAP3007 | Hypothetical protein |

| 33 | MAP3188 | FadE24 |

| 34 | MAP0990 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase |

| 35 | MAP1588c | AhpD |

| 36 | MAP1164 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| 37 | MAP1889c | Wag31 |

| 38 | MAP4233 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha |

| 39 | MAP4167 | rpsC |

| 40 | MAP3061c | Probable electron transfer flavoprotein (beta-subunit) fixed |

| 41 | MAP2228 | Hypothetical protein |

| 42 | MAP4233 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit alpha |

| 43 | MAP2453c | AtpH |

| 44 | MAP3005c | Hypothetical protein |

| 45 | MAP2280c | ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit |

This review summarizes advancements of research on mce genes of Mycobacteria with special reference to the Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), the cause of incurable granulomatous enteritis known as Johne’s disease (JD) in domestic livestock. Since MAP is not inactivated during pasteurization, human population is continuously at the risk of getting exposed to MAP infection through consumption of dairy products. MAP has also been associated with human disorders mainly of auto-immune nature (Faisal et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2014; Sechi and Dow 2015; Waddell et al., 2015; Chaubey et al. 2017; Gupta et al. 2017).

Objectives of this review are to enlighten the importance of Mce proteins in pathogenesis of Mycobacterial infections as well as facilitating the development of new candidates for Mycobacterial diagnostics. Current diagnostics for Mycobacterial infection have focused on the use of surface proteins as antigenic bio-markers of Mycobacterial species to diagnose the infection, which may be helpful in the control of disease (Li et al. 2005; Souza et al. 2011; Moigne and Mahana 2012; Chaubey et al. 2016). Our focus in this review is on the Mce proteins because (1) most of the Mycobacteria having Mce proteins, and (2) the information may be helpful in better understanding of the patho-biological and immunological significance of Mce proteins and their roles in the virulence of the pathogens belonging to Mycobacterial species.

2. The mce operon in MTB

MTB is an intracellular pathogen and reside inside the macrophages which is the vital constituents of the immune system (Mukhopadhyay and Balaji 2011). The mechanism of the entry and survival of MTB inside macrophages have been poorly understood earlier, but recent findings showed the presence of multiple cells-surface receptors that influence the entry of MTB into the macrophages: mannose receptors, complement receptors CR3b and CR1, Fc receptors, fibronectin receptor, scavenger receptors, and Mce proteins (Harboe et al. 2004; El-Shazly et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2017).

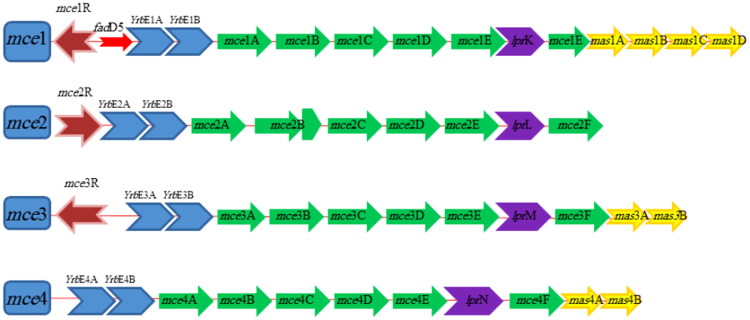

MTB genome possesses four dispersed, but homologous sets of genes called mce operons (mce1–mce4) organized in identical pattern and each mce operon translates into two integral membrane proteins (yrbEA-B) and six Mce proteins (MceA–F) (Ahmad et al. 2005; Uchiya et al. 2013). Hence, mce genes present in four operons and each operon is made up of eight genes (yrbEA-B and mceA–mceF) as shown in Figure 1. Differential expression of mce1–4 operons points toward their functional significance (Pasricha et al. 2011). Four downstream genes of MTB mce1 (Rv0175-78) operon, two downstream genes of MTB mce3 operon and two downstream genes of MTB mce4 operons are termed as ‘mce-associated proteins’ or Mas proteins, which are involved in Mce transporter function (Casali and Riley 2007) (Figure 1). Contribution of these mce genes on the pathogenicity of Mycobacteria may be determined by their level of expression (Haile et al. 2002; Marjanovic et al. 2010; Singh et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of M. tuberculosis mce operons. Transcription regulators are colored in brown, yrbE genes in blue, mce genes in green, mas genes in yellow and genes encoding Mce-family lipoprotein (lpr) are shown in purple.

2.1. Mammalian cell entry 1 (mce1) operon

The mce1 operon is present in all species of Mycobacteria. MTB encodes six (mce1A–mce1F) invasion-like proteins that localize to the cell wall and are involved in substrate trafficking (Chitale et al. 2001; Shimono et al. 2003; Stavrum et al. 2012). The mce1A (Rv0169) operon helps to change of plasma membrane in host mammalian cells that promote the uptake of products bound to it (Chitale et al. 2001). The Mce1 proteins taking part in mycolic acid or fatty acids importation (Marjanovic et al. 2011; Forrellad et al. 2014) and glutamate and phosphatidic acid as possible substrates of the new Mce transporters (Dassa and Bouige 2001).

Purified recombinant Mce1A protein coated on latex beads are internalized by non-phagocytic HeLa cells (Chitale et al. 2001; Kumar et al. 2003). Further studies have shown that mce1A gene deletion in M. bovis BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guerin) decreases in bacterium ability to invade Hela cell (Gioffre et al. 2005; Obregon-Henao et al. 2011; Zhang and Xie 2011; Castellanos et al. 2012). Beste and colleagues (2009) opined similar scenario for MTB mce1 mutants and reported these mutants were unable to enter, or exit early from, the slow growth rate state and are thereby over represented in slow growth rate cultures. Additionally, the mce1 operon proteins are involved in mycolic acid recycling and fatty acid transport (Stavrum et al. 2012). Forrellad et al. (2014) also demonstrated that the lack of Mce1 proteins affects the uptake of fatty acids. In addition, Rv0165c gene (a putative transcriptional regulator) is localized upstream of mce1 operon and this Mce1R regulator facilitates the balanced expression of the Mce1 proteins that are important for granuloma formation, which is necessary for the perseverance of Mycobacteria (Gioffre et al. 2005; Zhang and Xie 2011). It has been shown that mce1R gene (GntR-negative transcriptional regulators) may be involved in lipid transports (Cheigh et al. 2010; Joon et al. 2010). Casali and Riley (2007) also observed that mce1 operon can express independently. Mce1R may express under various negative regulators. Similar observations were also reported by Joon et al. (2010), who strongly supported the existence of two promoters for MTB mce1 that could potentially differentiate different functions of one operon. The mce1 operon is not the same as the other three mce operons, having a Rv0166 gene (fadD5), which is putatively involved in fatty acid catabolism (Joon et al. 2010). The fadD5 gene, a fatty acid CoA synthetizer, may be involved in recycling mycolic acids from dying MTB inside granulomas (Cheigh et al. 2010). Dunphy et al. (2010) have shown in their study that mice infected with a MTB mutant in fadD5 gene, survived longer than those infected with the wild-type strains. They also reported that MTB disrupted in fadD5 gene is diminished in growth in minimal medium supplied with only mycolic acids (Dunphy et al. 2010).

2.2. Mammalian cell entry 2 (mce2) operon

The mce2 operon of MTB-encoded proteins which showed highest amino acid identity with mce1 operon-encoded proteins (Chitale et al. 2001; Kumar et al. 2003; Ahmad et al. 2005). The mce2 operons are present in all M. avium, M. bovis and M. smegmatis species (Haile et al. 2002). The arrangement of mce2 operon is different from other three mce operons, having an Rv0590A gene fragment between mce2B and mce2C (Zhang and Xie 2011). However, information about mce2 operon-encoded proteins is scanty; Mce2A protein appears to have a distinct role from other mce operon-encoded proteins (Uchiya et al. 2013). Mce2 proteins may be involved in the sulfalipids (SL) metabolism and importation during MTB infection (Marjanovic et al. 2011).

Okamoto and colleagues (2006) found that the MTB mce2 operon mutants may have an imperfection in the catabolism of cell wall SL, and the accumulation of SL molecules in these mutants may reduce the granuloma formation and inhibit the macrophage activation. Marjanovic et al. (2011) reported that the MTB, with the activation of mce2 operon, facilitate the catabolism of SL, remodel architecture of the Mycobacterial cell wall in response to the host immune system, and promote the long-term survival of MTB during infection. Marjanovic et al. (2010) also showed that MTB H37Rv disrupted in mce2 gene leads to attenuation in the mouse model of tuberculosis. They also objected that deletion of mce2 gene does not affect the Mycobacterial viability in vitro. In 2005, Kumar et al. found that the mce2 operon could be expressed under all study conditions and that the knock-out of the mce2 operon may generate a potential vaccine strain of M. bovis. In addition, expression of mce2 gene is essential for Mycobacterial growth and might be involved in the latency of these bacteria (Zhang and Xie 2011). In this respect, we can hypothesize that each mce operon is selectively expressed under a particular condition during host infection.

2.3. Mammalian cell entry 3 (mce3) operon

The mce3 operon is not present in MAP, M. bovis BCG, M. smegmatis, M. microti and M. leprae (Ahmad et al. 2004; Gioffre et al. 2005; Zhang and Xie 2011). Therefore, it was suspected that mce3 operon deletion in these bacterial species might contribute to differences in virulence and/or bacterial host range (Bakshi et al. 2005). The absence of mce3 within these bacterial species has made this gene an interesting diagnostic candidate (Mitra et al. 2005). Mce3A and Mce3E proteins like Mce1A are also involved in uptake and survival of Mycobacteria (Uchiya et al. 2013). El-Shazly et al. (2007) purified recombinant Mce3A and lipoprotein LprM (Mce3E) from E. coli and reported that Mce3A facilitated the internalization and uptake of latex beads by HeLa cells.

Expression studies also revealed that the purified recombinant Mce3A, 3 D and 3E (LprM) protein expression have the ability to elicit antibody responses during MTB infection in human beings (Ahmad et al. 2004; Zhang and Xie 2011). The mce3 operon genes are regulated by mce3R (Rv1963) gene, a tetR transcriptional regulator gene, which regulates the expression of genes which are involved in the metabolism of lipids such as Ino1 and FadA4 (Santangelo et al. 2008; Marjanovic et al. 2010; Forrellad et al. 2014). These two genes are involved in phosphatidylinositol biosynthetic pathways and lipid degradation, respectively (Santangelo et al. 2008). Furthermore, bioinformatics evidence suggested that Mce3A, 3B, 3C, 3D, 3E and 3F are similar with the other three mce operons-encoded proteins in 31–46% of amino acid composition (Ahmad et al. 2005). So the mce3 operons relate to the virulence of pathogenic Mycobacteria.

2.4. Mammalian cell entry 4 (mce4) operon

The mce4 operon is present in most of the Mycobacterial species. It is expressed in the stationary phase of Mycobacterial growth culture or in mammalian hosts (Saini et al. 2008). The mce4 operons showed a high degree of conservation in different Mycobacterial species (Haile et al. 2002; Mitra et al. 2005; Timms et al. 2015). It has been shown that Mce4A protein promotes invasion of nonpathogenic E. coli strains into non-phagocytic HeLa cells (Saini et al. 2008; Zhang and Xie 2011). Xu et al. (2007) suggested that Mce4A might be a virulence factor which significantly inhibits alveolar macrophage activity. Therefore, deletion of mce4 operon attenuates MTB virulence in infected macrophages (Zhang and Xie 2011; Khan et al. 2016). In addition, the Mce4F (Rv3494c) was predicted as Mycobacterial virulence factor which could play a vital role in host cell invasion and could be related to infection adaptation (Rodriguez et al. 2015). The Mce4 proteins are also involved in cholesterol uptake, which is an essential carbon and energy source for Mycobacteria for its prolonged existence in host cells (Pandey and Sassetti 2008; Cheigh et al. 2010; Joon et al. 2010; Klepp et al. 2012; Uchiya et al. 2013). The mce4 operon is regulated by KstRregulator, which is involved in fatty acid catabolism (Kendall et al. 2007; Zhang and Xie 2011). Thus, the evidence points to the Mce4 family proteins as of importance for Mycobacterial pathogenesis due to their roles in cholesterol transport with cholesterol being an important nutrient during the Mycobacterial infection (Xu et al. 2007; Mohn et al. 2008; Rathor et al. 2013; Perkowski et al. 2016).

3. Distribution of mce operons appearing among bacteria

The genus Mycobacterium constitutes a large group of facultative and obligate pathogenic Mycobacteria, e.g. MTB, M. avium subsp. avium, M. ulcerans, M. leprae and MAP, causing major diseases in human beings and animals (Haile et al. 2002; Tortoli et al. 2017; Gupta et al. 2018). The homologous regions of mce gene families have been reported to be widely distributed in different Mycobacterial species, even in nonpathogenic Mycobacteria (Hemati et al., 2018; Haile et al. 2002; Gioffre et al. 2005; Saini et al. 2008). Parker et al. (1995) reported for the first time the presence of a conserved cellular entry factor, mce genes, in Mycobacteria other than the MTB, such as M. intracellulare, M. avium and M. scrofulaceum complex. Casali and Riley (2007) suggested that MTB mce-like operons (including six mce genes and two yrbE) existed within all Mycobacterium species and in five other Actinomycetales genera.

Notably, the mce loci are present in diverse mycolic acid bacteria which have hydrophobic and thick cell walls, including MTBmce, M. avium (MAmce), MAP (MAPmce) M. bovis (MBmce) and M. smegmatis (MSmce) and may be found in other species, such as Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Janibacter, Amycolatopsis, Nocardiodes and Streptomyces (Chitale et al. 2001; Haile et al. 2002; Kumar et al. 2003; Casali and Riley 2007; Mohn et al. 2008). M. smegmatis and MAP have two copies of the mce5 operon; N. farcinica and MAP have two copies of the mce7 operon; N. farcinica possess two copies of the mce8 operon and Streptomyces has a cluster of mce6 operons (Casali and Riley 2007). The mce7 operons have a single mas gene, the mce6 operons of S. avermilitis and N. farcinica have two copies of mas genes, and the S. coelicolor operon has four copies of mas genes, which all are encoded downstream of mce operons (Casali and Riley 2007).

However, the number of mce operons varies between Mycobacterial species. For example, the fast-growing Mycobacteria contain the most in contrast to the slow-growing and host-specialized species have less operons, and the obligate intracellular Mycobacteria such as M. leprae, have only a single mce operon (Miller et al. 2004). Comparison of the mce operons encoded in some Actinomycetales revealed that these contain an extra mkl gene, which encodes an ATPase component resembling those in the ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-transporter system (Casali and Riley 2007). Further studies showed expression of the mce genes during steroid and cholesterol metabolism in the Rhodococcal species, with the mce4 operon encoding a steroid transporter gene (Kumar et al. 2003; Van der Geize et al. 2007). Mycobacterium indicus pranii, an opportunistic pathogen of the MAC family, has extra Mce-related proteins that are common among all the Mycobacterium species except for M. leprae and M. bovis (Singh et al. 2014b). Sato et al. (2007) have shown that the mce1A gene (ML2589) products can mediate entry of M. leprae into epithelial cells of the host respiratory tract, whereas anti-Mce1A antibodies can prevent bacterial internalization by epithelial cells. Garcia-Fernández et al. (2017) found that M. smegmatis contains 6 mce operons that encode ABC-like transporter systems, which are involved in sterol uptake. The mce3, mce4 and mce7 operons of M. smegmatis possess the same organization found in mce operons of MTB. MSmce1 operon differs from MTBmce operons in having two additional mas genes (MSMEG_5902 and MSMEG_5893), whereas MSmce5A and MSmce5B operons have insertions between the mce genes (Garcia-Fernández et al. 2017). The presence of Mce proteins in nonpathogenic Mycobacteria implies their role in mechanisms other than virulence.

Some Gram-negative bacteria additionally contain homologous regions of mce gene family, which encode an ABC-transporter-like system, which may be associated with remodeling the bacterial cell envelope (Casali and Riley 2007). In these bacteria, mce homologue operons always have the orthologuos of mkl genes (Wolf et al. 2001). Many Proteobacteria species possess mce (PqiB proteins) genes that are analogous to the mce complex of Acinomycetales (Casali and Riley 2007). Of note, mce-associated ATPase of Pseudomonas putida make the cells sensitive to toluene (Kim et al. 1998).

In Neisseria meningitidis the gltT gene is a mce-like operon, that is expressed only in invasive hypervirulent isolates (Pagliarulo et al. 2004). Clark et al. (2013) suggested that the deletion of mce operon in saprophyte Streptomyces species may have serious effects on bacterial long-term survival in soil environment. More recently, Mce surface protein was described in Leptospira species as a novel virulence factor which could mediate the attachment of L. interrogans to human cell receptors and are responsible for adherence and invasion mechanisms (Cosate et al. 2016). The presence of mce genes, in both Gram-negative bacteria and Actinomycetales, affects characteristics of the cell membrane and virulence of the pathogenic species.

4. Mce operon in MAP

Homologous regions of mce gene family have been demonstrated to be present in all of the MAP isolates (Motiwala et al. 2006). The mce gene is placed in the outer membrane of MAP (Hemati et al., 2018; Li et al. 2005; Cangelosi et al. 2006). Mce proteins encoded by MBmce and MAmce operons showed 99.6–100% and 56.2–85.5% homology, respectively, with the respective MTBmce proteins (Haile et al. 2002). However, the functions of Mce protein family are not yet been clearly understood in other Mycobacteria (Klepp et al. 2012). In the MAP type K-10 reference genome, the mce genes are present in 8 separate clusters containing 6–10 ORFs (Casali and Riley 2007; Xu et al. 2007; Paustian et al. 2008; Castellanos et al. 2009). On the basis of mce operons MAP differs from MTB, as MAP has eight-mce operons (MAPmce1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 5, 7 and 7) instead of four mce operons (MTBmce1–4) that are present in MTB (Paustian et al. 2008; Castellanos et al. 2009). MAP also possesses two copies of each of the mce5 and mce7 operons (Casali and Riley 2007).

Individual cluster of mce genes in the MAP genome was supposed to encode specific control mechanisms of adaptations that contributed toward entry and survival in different hosts or diverse environments (Zhang and Xie 2011). Timms et al. (2015) reported the missing of conserved hypothetical integral membrane protein yrbE3B and mce3 operon in MAP K10. They reported that MAPmce3 mutant strain grew slower than the parental strain, thus providing a possible explanation for the longer doubling time of MAP. The sequences of the yrbE genes associated with mce genes of MTB and MAP are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Classification of MAP and MTB H37Rv yrbE and mce genes.

| Prefixa | yrbE1A | yrbE1B | mce1A | mce1B | mce1C | mce1D | mce1E | mce1F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP | 3602 | 3603 | 3604 | 3605 | 3606 | 3607 | 3608 | 3609 |

| MTB | 0167 | 0168 | 0169 | 0170 | 0171 | 0172 | 0173 | 0174 |

| yrbE2A | yrbE2B | mce2A | mce2B | mce2C | mce2D | mce2E | mce2F | |

| MAP | 4082 | 4083 | 4084 | 4085 | 4086 | 4087 | 4088 | 4089 |

| MTB | 0587 | 0588 | 0589 | 0590 | 0591 | 0592 | 0593 | 0594 |

| yrbE3A | yrbE3B | mce3A | mce3B | mce3C | mce3D | mce3E | mce3F | |

| MAP | 2117b | 2117b.1c | 2116b | 2115b | 2114b | 2113b | 2112b | 2111b |

| MTB | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 |

| yrbE4A | yrbE4B | mce4A | mce4B | mce4C | mce4D | mce4E | mce4F | |

| MAP | 0562 | 0563 | 0564 | 0565 | 0566 | 0567 | 0568 | 0569 |

| MTB | 3451b | 3450b | 3499b | 3498b | 3497b | 3496b | 3495b | 3494b |

| yrbE5A | yrbE5B | mce5A | mce5B | mce5C | mce5D | mce5E | mce5F | |

| MAP | – | – | 2189 | 2190 | 2191 | 2192 | 2193 | 2194 |

| MTB | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| yrbE6A | yrbE6B | mce6A | mce6B | mce6C | mce6D | mce6E | mce6F | |

| MAP | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| MTB | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| yrbE7A | yrbE7B | mce7A | mce7B | mce7C | mce7D | mce7E | mce7F | |

| MAP | 1849 | 1850 | 1851 | 1852 | 1853 | 1854 | 1855 | 1856 |

| MTB | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| yrbE8A | yrbE8B | mce8A | mce8B | mce8C | mce8D | mce8E | mce8F | |

| MAP | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| MTB | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

aOrganism specific gene number prefix: MAP; MTB H37Rv.

bOrthologous sequence present, but Open Reading Frame (ORF) annotated in reverse direction.

cOrthologous sequence present, but not annotated. ORF extends ∼400 bp at 5′end.

Whole-genome DNA microarray representing MAP revealed that there are 14 large sequence polymorphisms (Motiwala et al. 2006). LSPP12 was the most widely conserved MAP-specific region that included a cluster of six homologous of the mce-family (MAP2189-MAP2194), which is involved in lipid metabolism (Hemati et al., 2018; Semret et al. 2005; Alexander et al. 2009). In MAP, mas homologous genes were located in pairs (MAP0750-51c, MAP0767-68c) both downstream and upstream of the MAPmce5 operon (Casali and Riley 2007). These genes have been identified as important for MAP invasion, survival and virulence (Semret et al. 2005). Large sequence polymorphisms (LSPs) having diagnostic importance and in total 14 LSPs have been identified till to date, whereas LSP11 was absent in the MAP isolates, which comprised part of a mce2 operon (Motiwala et al. 2006). The loss of mce2 or, mce3, genes in the most pathogenic MAP isolates along with the deletion of mce3 from virulent M. bovis together prove either mce2 and mce3 operons to act as virulence factors (Semret et al. 2004). Timms and colleagues (2015) observed the gap between mycobactin A and mycobactin J (lipK) genes in all MAP genomes containing at least one mce operon 8.7 kB downstream from mycobactin A gene and a link between the mce operons and the mycobactin cluster genes. Studies on the importance of the close proximity of this operon with mycobactin cluster are currently underway.

5. Mechanisms of function of mce genes

Mechanism and function of mce genes is not very clear yet, but Mycobacterial species not having mce genes cannot enter the host cell and thereby the severity of infection could be reduced (Castellanos et al. 2012). Several observations strengthen this hypothesis: gene knockouts of mce1–mce3 and mce4 in MTB and M. bovis (BCG) cause attenuation of these strains in mouse models (Castellanos et al. 2012); inactivation of mce genes could reduce the ability of MTB to invade and persist in the host cells (Gioffre et al. 2005); mce3 operon mutant of MTB was attenuated in mice (Senaratne et al. 2008); the mce4 operon mutant of MTB have shown growth defect and significantly reduced bacterial survival in infected mice (Saini et al. 2008). Most recently, Zhang et al. (2017) have shown that Mce3C as MTB surface protein could interact with β2 integrin and cause clustering at Mycobacterial entry site. In the host mammalian cells, interaction between adhesion proteins such as integrin and their ligand is essential for cell proliferation and growth, thus, the interaction between Mce proteins and integrin may be involved in an adhesion-dependent mechanism (Simoes et al. 2005).

Kumar et al. (2005) suggested that invasion of the host cell is not the only function of mce operons. Mce-family proteins may also have a role in pathogenesis by inhibiting alveolar macrophage activity or eliciting immune response from the host, may serve as lipid transporters by analogy to ABC-transporters and also can be related to granuloma formation and long-term survival of Mycobacteria within the host cells with all above attributes playing a very important role in Mycobacterial virulence (Mohn et al. 2008; Marjanovic et al. 2010; Rathor et al. 2013; Rodriguez et al. 2015; Perkowski et al. 2016). A previous study has shown that mce genes may have a role in the maintenance of cell surface properties in Mycobacteria and can be contributed to the cell envelope production (Klepp et al. 2012). Furthermore, some Mce proteins of the Mycobacterial membrane may contribute to the creation of beta barrel proteins serving as channels (by six Mce proteins with similarity to substrate binding proteins and two YrbE proteins with similarity to ABC-permeases) and may function as ABC-transport systems (Li et al. 2005; Cangelosi et al. 2006; Pandey and Sassetti 2008; Paustian et al. 2008; Perkowski et al. 2016). Arrangements of Mce proteins are structurally similar to ABC-transporters and due to the cell surface location of Mce proteins; it has been suggested that they may play a role in cell invasion of cholesterol-rich regions and immuno-modulation (Lamont et al. 2014; Khan et al. 2016). Mohn et al. (2008) determined that in Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 (with 2 mce operons), mce4 operon encodes an ATP-dependent steroid transporter that was essential for bacterial growth on media containing a range of sterols as the only carbon source.

This novel type of ABC-transporter system encoded by mce loci is believed to be involved in both import of fatty acids as a source of nutritional carbons and the export of a variety of lipid virulence factors during Mycobacterial growth (Wang et al. 2007). Just like ABC-type transporters, Mce transporter system can specifically bind with small lipid molecular compounds (Zhang and Xie 2011). The nature of their substrates has only been revealed in the case of the Mce4 proteins with cholesterol as one potential substrate (Forrellad et al. 2014). Pajon et al. (2006) found that eight-Mce proteins of MTB could help piercing of the outer lipid layer and could form a channel through this lipid bilayer. Therefore, it is possible that these Mce proteins may be more important for the transport of solutes through hydrophobic barriers such as host cell membranes or the Mycobacterial envelope (Joshi et al. 2006). The mce4 operon of R. equi encodes an active system for steroid uptake, such as cholesterol, 5-α-cholestanol and β-sitosterol (Mohn et al. 2008). This hypothesis is supported by the recent finding that the deletion of mce4 operon was responsible for the cholesterol uptake failure in the mce4-deficient strain (Kelpp et al. 2013). Saprophytic Mycobacteria with steroid uptake activity might be able to detect the presence of abundant steroid substrates in the nature.

Another possibility is that the ability of Mce4 proteins to bind to cholesterol-rich areas of the cell membrane may play a vital role in the pathogenesis of Mycobacteria by localizing the Mycobacterium, modifying the host cell membrane, facilitating host cell entry and blocking the normal phagosome maturation or eliciting an important immune response from the host (Keown et al. 2012). It has been demonstrated that the mce4 operons are involved in the cholesterol uptake in MTB (Pandey and Sassetti 2008), R. equi (van der Geize et al. 2007), M. smegmatis (Klepp et al. 2012) and R. jostii RHA1 (Mohn et al. 2008). Remarkably, the uptake of this steroid by Mce4A protein in MTB has been linked to its long-term survival ability in the host (khan et al. 2016).

Besides, Mce-family proteins as cell surface proteins are recognized by the immune system of the host in the involvement of Mycobacterial species virulence (Ghosh et al. 2012). The functional importance of these highly antigenic mce operons is illustrated by their differential expression profile in bacilli under different culture conditions and during infection (Ahmad et al. 2004; Joon et al. 2010; Pasricha et al. 2011). The expression of mce operons in Mycobacteria may be modulated in response to stress conditions and nutritional status, however, the extra-cellular signals required for mce expression are not known yet (Zhu et al. 2008).

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the detection of Mce proteins with high immunogenicity can be a big step in the early diagnosis of Mycobacterial diseases. Surface location of the mce proteins makes them interesting early diagnostic markers. Taken together, the functional importance of mce operons invites further studies, however work done so far has shown that there are immune-dominant epitopes within mce genes, suggesting that these could potentially be exploited as a source of antigenic proteins for the diagnosis of all the Mycobacterial species notably MAP.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahmad S, El-Shazly S, Mustafa A, Al-Attiyah R. 2004. Mammalian cell-entry proteins encoded by the mce3 operon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are expressed during natural infection in humans. Scand J Immunol. 60(4):382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S, El-Shazly S, Mustafa A, Al-Attiyah R. 2005. The six mammalian cell entry proteins (Mce3A-F) encoded by the mce3 operon are expressed during in vitro growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 62(1):16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DC, Turenne CY, Behr MA. 2009. Insertion and deletion events that define the pathogen Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1913:1018–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda S, Bomfim G, Knights R, Huima-Byron T, Riley L. 1993. Cloning of a M. tuberculosis DNA fragment associated with entry and survival inside cells. Science. 261(5127):1454–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi CS, Shah DH, Verma R, Singh RK, Malik M. 2005. Rapid differentiation of Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on a 12.7-kb fragment by a single tube multiplex-PCR. Vet Microbiol. 109(3–4):211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste DJ, Espasa M, Bonde B, Kierzek AM, Stewart GR, McFadden J. 2009. The genetic requirements for fast and slow growth in Mycobacteria. PLoS One. 4(4):e5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi GA, Do JS, Freeman R, Bennett JG, Semret M, Behr MA. 2006. The two-component regulatory system mtrAB is required for morphotypic multidrug resistance in Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 50(2):461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali N, Riley LW. 2007. A phylogenomic analysis of the Actinomycetales mce operons. BMC Genomics. 8:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos E, Aranaz A, de Juan L, Dominguez L, Linedale R, Bull TJ. 2012. A 16 kb naturally occurring genomic deletion including mce and PPE genes in Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis isolates from goats with Johne's disease. Vet Microbiol. 159(1-2):60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos E, Aranaz A, Gould KA, Linedale R, Stevenson K, Alvarez J. 2009. Discovery of stable and variable differences in the Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis type I, II, and III genomes by pan-genome microarray analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 753:676–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaubey KK, Gupta RD, Gupta S, Singh SV, Bhatia AK, Jayaraman S, Kumar N, Goel A, Rathore AS, Sahzad, et al. . 2016. Trends and advances in the diagnosis and control of paratuberculosis in domestic livestock. Vet Q. 36(4):203–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaubey KK, Singh SV, Gupta S, Singh M, Sohal JS, Kumar N, Singh MK, Bhatia AK, Dhama K. 2017. Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis – an important food borne pathogen of high public health significance with special reference to India: an update. Vet Q. 37(1):282–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheigh CI, Senaratne R, Uchida Y, Casali N, Kendall LV, Riley LW. 2010. Post treatment reactivation of tuberculosis in mice caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis disrupted in mce1R. J Infect Dis. 2025:752–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitale S, Ehrt S, Kawamura I, Fujimura T, Shimono N, Anand N. 2001. Recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein associated with mammalian cell entry. Cell Microbiol. 4:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LC, Seipke RF, Prieto P, Willemse J, van Wezel GP, Hutchings MI, Hoskisson PA. 2013. Mammalian cell entry genes in Streptomyces may provide clues to the evolution of bacterial virulence. Sci Rep. 3:1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosate MR, Siqueira GH, de Souza GO, Vasconcellos SA, Nascimento AL. 2016. Mammalian cell entry (Mce) protein of Leptospira interrogans binds extracellular matrix components, plasminogen and β2 integrin. Microbiol Immunol. 60(9):586–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassa E, Bouige P. 2001. The ABC of ABCs: a phylogenetic and functional classification of ABC systems in living organisms. Res Microbiol. 152(3-4):211–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunphy KY, Senaratne RH, Masuzawa M, Kendall LV, Riley LW. 2010. Attenuation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis functionally disrupted in a fatty acyl-coenzyme A synthetase gene fadD5. J Infect Dis. 201(8):1232–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shazly S, Ahmad S, Mustafa AS, Al-Attiyah R, Krajci D. 2007. Internalization by HeLa cells of latex beads coated with mammalian cell entry Mce proteins encoded by the mce3 operon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol. 56(Pt 9):1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal SM, Yan F, Chen TT, Useh NM, Guo S, Yan W. 2013. Evaluation of a Salmonella vectored vaccine expressing Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis antigens against challenge in a goat model. PLoS One. 8(8):e70171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrellad MA, McNeil M, Santangelo ML, Blanco FC, Garcia E, Klepp LI. 2014. Role of the Mce1 transporter in the lipid homeostasis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 94(2):170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Fernández J, Papavinasasundaram K, Galan B, Sassetti CM, Garcia JL. 2017. Molecular and functional analysis of the mce4 operon in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Environ Microbiol. 19(9):3689–3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Hsu C, Alyamani EJ, Shehata MM, Al-Dubaib MA, Al-Naeem A, Hashad M, Mahmoud OM, Alharbi KB, Al-Busadah K, et al. . 2012. Genome-wide analysis of the emerging infection with Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in the Arabian camels Camelusdromedarius. PLos One. 7(2):e31947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioffre A, Infante E, Aguilar D, Santangelo MP, Klepp L, Amadio A, Meikle V, Etchechoury I, Romano MI, Cataldi A, et al. . 2005. Mutation in mce operons attenuates Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Microbes Infect. 7:325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RS, Lo B, Son J. 2018. Phylogenomics and comparative genomic studies robustly support division of the genus Mycobacterium into an emended genus Mycobacterium and four novel genera. Front Microbiol. 9:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Singh SV, Gururaj K, Chaubey KK, Singh M, Lahiri B, Agarwal P, Kumar A, Misri J, Hemati Z, et al. . 2017. Comparison of IS900 PCR with ‘Taqman probe PCR’ and ‘SYBR green Real time PCR’ assays in patients suffering with thyroid disorder and sero-positive for Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. IJBT. 16(2):228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Haile Y, Caugant DA, Bjune G, Wiker HG. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis mammalian cell entry operon mce homologs in Mycobacterium other than tuberculosis MOTT. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 33(2):125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harboe M, Das AK, Mitra D, Ulvund G, Ahmad S, Harkness RE, Das D, Mustafa AS, Wiker HG. 2004. Immuno-dominant B-cell epitope in the Mce1A mammalian cell entry protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cross-reacting with glutathione S-transferase. Scand J Immunol. 59(2):190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemati Z, Haghkhah M, Derakhshandeh A, Singh S, Chaubey KK. 2018. Cloning and characterization of MAP2191 gene, a mammalian cell entry antigen of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Mol Biol Res Commun. 7(4):165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom GL, Davies NJ, Chong ZS, Bryant JA, Jamshad M, Sharif M, Cunningham AF, Knowles TJ, Chng SS, Cole JA, et al. . 2017. MCE domain proteins: conserved inner membrane lipid-binding proteins required for outer membrane homeostasis. Sci Rep. 7(1):8608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joon M, Bhatia S, Pasricha R, Bose M, Brahmachari V. 2010. Functional analysis of an intergenic non-coding sequence within mce1 operon of M. tuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 10:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi SM, Pandey AK, Capite N, Fortune SM, Rubin EJ, Sassetti CM. 2006. Characterization of Mycobacterial virulence genes through genetic interaction mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103(31):11760–11765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall SL, Withers M, Soffair CN, Moreland NJ, Gurcha S, Sidders B, Frita R, Ten Bokum A, Besra GS, Lott JS, et al. . 2007. A highly conserved transcriptional repressor controls a large regulon involved in lipid degradation in Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 65(3):684–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keown DA, Collings DA, Keenan JI. 2012. Uptake and persistence of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in human monocytes. Infect Immun. 80(11):3768–3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Islam A, Hassan MI, Ahmad F. 2016. Purification and structural characterization of Mce4A from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Biol Macromol. 93(Pt A):235–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lee S, Lee K, Lim D. 1998. Isolation and characterization of toluene- sensitive mutants from the toluene-resistant bacterium Pseudomonas putida GM73. J Bacteriol. 180(14):3692–3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepp LI, Forrellad MA, Osella AV, Blanco FC, Stella EJ, Bianco MV, Santangelo Mde L, Sassetti C, Jackson M, Cataldi AA, et al. . 2012. Impact of the deletion of the six mce operons in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbes Infect. 14(7-8):590–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Bose M, Brahmachari V. 2003. Analysis of expression profile of mammalian cell entry (mce) operons of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 71(10):6083–6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Chandolia A, Chaudhry U, Brahmachari V, Bose M. 2005. Comparison of mammalian cell entry operons of Mycobacteria: in silico analysis and expression profiling. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 43(2):185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont EA, Talaat AM, Coussens PM, Bannantine JP, Grohn YT, Katani R, Li LL, Kapur V, Sreevatsan S. 2014. Screening of Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis mutants for attenuation in a bovine monocyte derived macrophage model. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 4:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Bannantine JP, Zhang Q, Amonsin A, May BJ, Alt D, Banerji N, Kanjilal S, Kapur V. 2005. The complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102(35):12344–12349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjanovic O, Iavarone AT, Riley LW. 2011. Sulfolipid accumulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis disrupted in the mce2 operon. J Microbiol. 49(3):441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjanovic O, Miyata T, Goodridge A, Kendall LV, Riley LW. 2010. Mce2 operon mutant strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is attenuated in C57BL/6 mice. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 90(1):50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CD, Hall K, Liang YN, Nieman K, Sorensen D, Issa B, Anderson AJ, Sims RC. 2004. Isolation and characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading Mycobacterium isolates from soil. Microb Ecol. 48(2):230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra D, Saha B, Das D, Wiker HG, Das AK. 2005. Correlating sequential homology of Mce1A, Mce2A, Mce3A and Mce4A with their possible functions in mammalian cell entry of Mycobacterium tuberculosis performing homology modeling. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 85(5-6):337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn WW, van der Geize R, Stewart GR, Okamoto S, Liu J, Dijkhuizen L, Eltis LD. 2008. The actinobacterial mce4 locus encodes a steroid transporter. J Biol Chem. 283(51):35368–35374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moigne VL, Mahana W. 2012. P27-PPE36 (Rv2108) Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen – member of PPE protein family with surface localization and immunological activities Understanding Tuberculosis Pere-Joan Cardona. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Motiwala AS, Li L, Kapur V, Sreevatsan S. 2006. Current understanding of the genetic diversity of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 8(5):1406–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Balaji KN. 2011. The PE and PPE proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 91(5):441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obregon-Henao A, Shanley C, Bianco MV, Cataldi AA, Basaraba RJ, Orme IM, Bigi F. 2011. Vaccination of guinea pigs using mce operon mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Vaccine. 29(26):4302–4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Fujita Y, Naka T, Hirai M, Tomiyasu I, Yano I. 2006. Mycobacterial sulfolipid shows a virulence by inhibiting cord factor induced granuloma formation and TNF-alpha release. Microb Pathog. 40(6):245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarulo C, Salvatore P, De Vitis LR, Colicchio R, Monaco C, Tredici M, Talà A, Bardaro M, Lavitola A, Bruni CB, et al. . 2004. Regulation and differential expression of gdhA encoding NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase in Neisseria meningitidis clinical isolates. Mol Microbiol. 51(6):1757–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajon R, Yero D, Lage A, Llanes A, Borroto CJ. 2006. Computational identification of b-barrel outer-membrane proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis predicted proteomes as putative vaccine candidates. Tuberculosis. 86(3–4):290–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey AK, Sassetti CM. 2008. Mycobacterial persistence requires the utilization of host cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 105(11):4376–4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Tsai YL, Palmer CJ. 1995. Comparison of PCR-generated fragments of the mce gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. avium, M. intracellulare, and M. scrofulaceum. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2:770–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasricha R, Chandolia A, Ponnan P, Saini NK, Sharma S, Chopra M, Basil MV, Brahmachari V, Bose M. 2011. Single nucleotide polymorphism in the genes of mce1 and mce4 operons of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: analysis of clinical isolates and standard reference strains. BMC Microbiol. 11:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paustian ML, Zhu X, Sreevatsan S, Robbe-Austerman S, Kapur V, Bannantine JP. 2008. Comparative genomic analysis of Mycobacterium avium subspecies obtained from multiple host species. BMC Genomics. 9:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkowski EF, Miller BK, McCann JR, Sullivan JT, Malik S, Allen IC, Godfrey V, Hayden JD, Braunstein M. 2016. An orphaned Mce-associated membrane protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a virulence factor that stabilizes Mce transporters. Mol Microbiol. 100(1):90–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathor N, Chandolia A, Saini NK, Sinha R, Pathak R, Garima K, Singh S, Varma-Basil M, Bose M. 2013. An insight into the regulation of mce4 operon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 93(4):389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez DC, Ocampo M, Varela Y, Curtidor H, Patarroyo MA, Patarroyo ME. 2015. Mce4F Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein peptides can inhibit invasion of human cell lines. Pathog Dis. 73:pii: ftu020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini NK, Sharma M, Chandolia A, Pasricha R, Brahmachari V, Bose M. 2008. Characterization of Mce4A protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role in invasion and survival. BMC Microbiol. 8:200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo MP, Blanco FC, Bianco MV, Klepp LI, Zabal O, Cataldi AA, Bigi F. 2008. Study of the role of Mce3R on the transcription of mce genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 8:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Fujimura T, Masuzawa M, Yogi Y, Matsuoka M, Kanoh M, Riley LW, Katsuoka K. 2007. Recombinant Mycobacterium leprae protein associated with entry into mammalian cells of respiratory and skin components. J Dermatol Sci. 46(2):101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechi LA, Dow CT. 2015. Mycobacterium avium. Paratuberculosis zoonosis, the hundred year war beyond Crohn’s disease. Front Microbiol. 6:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semret M, Alexander DC, Turenne CY, de Haas P, Overduin P, van Soolingen D, Cousins D, Behr MA. 2005. Genomic polymorphisms for Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis diagnostics. J Clin Microbiol. 43(8):3704–3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semret M, Zhai G, Mostowy S, Cleto C, Alexander D, Cangelosi G, Cousins D, Collins DM, van Soolingen D, Behr MA. 2004. Extensive genomic polymorphism within Mycobacterium avium. J Bacteriol. 186(18):6332–6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaratne RH, Sidders B, Sequeira P, Saunders G, Dunphy K, Marjanovic O, Reader JR, Lima P, Chan S, Kendall S, et al. . 2008. Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains disrupted in mce3 and mce4 operons are attenuated in mice. J Med Microbiol. 57(Pt 2):164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimono N, Morici L, Casali N, Cantrell S, Sidders B, Ehrt S, Riley LW. 2003. Hypervirulent mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resulting from disruption of the mce1 operon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 100(26):15918–15923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes I, Mueller EC, Otto A, Bur D, Cheung AY, Faro C, Pires E. 2005. Molecular analysis of the interaction between cardosin A and phospholipase Da: identification of RGD/KGE sequences as binding motifs for C2 domains. FEBS J. 272(22):5786–5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Katoch VM, Mohanty KK, Chauhan DS. 2016. Analysis of expression profile of mce operon genes (mce1, mce2, mce3 operon) in different Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates at different growth phases. Indian J Med Res. 143(4):487–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Y, Kohli S, Sowpati DT, Rahman SA, Tyagi AK, Hasnain SE. 2014. Gene cooption in Mycobacteria and search for virulence attributes: comparative proteomic analyses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium indicus pranii and other Mycobacteria. Int J Med Microbiol. 304(5-6):742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza GS, Rodrigues AB, Gioffré A, Romano MI, Carvalho EC, Ventura TL, Lasunskaia EB. 2011. Apa antigen of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis as a target for species-specific immunodetection of the bacteria in infected tissues of cattle with paratuberculosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 143(1-2):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrum R, Valvatne H, Stavrum A-K, Riley LW, Ulvestad E, Jonassen I, Doherty TM, Grewal HMS. 2012. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mce1 protein complex initiates rapid induction of transcription of genes involved in substrate trafficking. Genes Immun. 13(6):496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timms VJ, Hassan KA, Mitchell HM, Neilan BA. 2015. Comparative genomics between human and animal associated subspecies of the Mycobacterium avium complex: a basis for pathogenicity. BMC Genomics. 16:695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortoli E, Fedrizzi T, Meehan CJ, Trovato A, Grottola A, Giacobazzi E, Serpini GF, Tagliazucchi S, Fabio A, Bettua C, et al. . 2017. The new phylogeny of the genus Mycobacterium: the old and the news. Infect Genet Evol. 56:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiya K, Takahashi H, Yagi T, Moriyama M, Inagaki T, Ichikawa K, Nakagawa T, Nikai T, Ogawa K. 2013. Comparative genome analysis of Mycobacterium avium revealed genetic diversity in strains that cause pulmonary and disseminated disease. PLoS One. 8(8):e71831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Geize R, Yam K, Heuser T, Wilbrink MH, Hara H, Anderton MC, Sim E, Dijkhuizen L, Davies JE, Mohn WW, et al. . 2007. A gene cluster encoding cholesterol catabolism in a soil Actinomycete provides insight into Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104(6):1947–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell LA, Rajić A, Stärk KDC, McEwen SA. 2015. The zoonotic potential of Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analyses of the evidence. Epidemiol Infect. 143(15):3135–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Langley R, Gulten G, Wang L, Sacchettini JC. 2007. Identification of a type III thioesterase reveals the function of an operon crucial for Mtb virulence. Chem Biol. 14(5):543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Pritchard JR, Kreitmann L, Montpetit A, Behr MA. 2014. Disruption of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis-specific genes impairs in vivo fitness. BMC Genomics. 15:415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf YI, Rogozin IB, Kondrashov AS, Koonin EV. 2001. Genome alignment, evolution of prokaryotic genome organization, and prediction of gene function using genomic context. Genome Res. 11(3):356–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Li Y, Yang J, Zhou X, Yin X, Liu M, Zhao D. 2007. Effect of recombinant Mce4A protein of Mycobacterium bovis on expression of TNF-alpha, iNOS, IL-6, and IL-12 in bovine alveolar macrophages. Mol Cell Biochem. 302(1-2):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Xie JP. 2011. Mammalian cell entry gene family of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 352(1-2):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li J, Li B, Wang J, Liu CH. 2017. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mce3C promotes Mycobacteria entry into macrophages through activation of β2 integrin-mediated signalling pathway. Cell Microbiol. 20(2):800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Tu ZJ, Coussens PM, Kapur V, Janagama H, Naser S, Sreevatsan S. 2008. Transcriptional analysis of diverse strains Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in primary bovine monocyte derived macrophages. Microbes Infect. 10(12-13):1274–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]