Abstract

Background: Despite transgender people being more visible in prison systems, research suggests they are at higher risk of experiencing sexual violence compared to other prisoners. Research also suggests that transgender prisoners experience harassment, and physical and sexual assault by fellow prisoners, and prison officers who lack transgender-specific health knowledge. There exist no systematic reviews on the experiences of transgender people in prisons. This review aims to fill this research gap. The following question developed in consultation with transgender, sexual health/HIV and corrective services stakeholders has guided the systematic review: What are transgender and gender-diverse prisoners’ experiences in various prison settings and what are their knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs?

Methods: The review followed the PRISMA guidelines and searches were conducted in four databases for the period of January 2007 to August 2017. Studies were assessed against predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Included studies were peer-reviewed, written in English with online full-text availability and reported data on transgender and gender-diverse prisoner experiences relevant to the research question.

Results: Eleven studies (nine qualitative, one quantitative, one mixed-methods; nine in USA, two in Australia) met the criteria for review. Four studies were of high quality, six were of good/acceptable quality, and one study was of modest quality. Transgender and gender-diverse prisoners reported a range of challenges which included sexual assault, discrimination, stigma, harassment, and mistreatment. Information on their sexual health and HIV/STIs knowledge, attitudes, practices is in short supply. Also, their lack of access to gender-affirming, sexual health/STIs and mental health services is commonplace.

Conclusions: The experiences of transgender prisoners as reported in this review are almost uniformly more difficult than other prisoners. Their “otherness” is used as a weapon against them by fellow prisoners through intimidation and violence (including sexual) and by prison officers through neglect and ignorance.

Keywords: Gender-diverse, HIV, incarceration, lived experiences, prison officers, sexual coercion, transgender, vulnerable group

Introduction

Within prison populations, the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and the National Standards to Prevent, Detect and to Respond to Prison Rape: Final Rule (PREA) in the United States of America (USA) identify transgender prisoners as a “vulnerable group” and “vulnerable inmates” (Atabay, 2009; Gatherer, Atabay, & Hariga, 2014; U.S. Department of Justice, 2012), as their “appearance or manner” do not “conform to traditional gender expectations” (U.S Department of Justice, 2012). This vulnerability also reflects the high prevalence of physical and sexual violence transgender and gender-diverse people experience outside the prison system (Blondeel et al., 2018). Due to their “heightened risk of discrimination and abuse in the closed [prison] environment…[and] being at high risk of rape, they are also at high risk of acquiring HIV/AIDS in prisons” (Gatherer et al., 2014). The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS] (2015) define transgender as follows:

Transgender is an umbrella term to describe people whose gender identity and expression does not conform to the norms and expectations traditionally associated with their sex at birth. Transgender people include individuals who have received gender reassignment surgery, individuals who have received gender-related medical interventions other than surgery (e.g., hormone therapy) and individuals who identify as having no gender, multiple genders or alternative genders. Transgender individuals may self-identify as transgender, female, male, transwoman or transman, transsexual, hijra, kathoey, waria or one of many other transgender identities, and they may express their genders in a variety of masculine, feminine and/or androgynous ways. (UNAIDS, 2015)

It is recognized that prisoners are at higher risk for acquiring HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs; Das & Horton, 2016; Todts, 2014) due to underfunded and overcrowded prisons (Baral et al., 2013), limited provision of condoms/dental dams (Mahon, 1996), and unprotected sex, risky sexual practices, and sexual violence (Banbury, 2004; Saliu & Akintunde, 2014; Todts, 2014; UNAIDS, 2014). Unsafe injection practices (Saliu & Akintunde, 2014), very limited provision of syringes/needles (Stoove, 2016), unsafe tattooing practices (Goyer & Gow, 2001a, 2001b; UNAIDS, 2014), discriminatory criminal justice systems and insufficient knowledge about effective preventative measures, care and support services (Beyrer, Kamarulzaman, & McKee, 2016; Das & Horton, 2016; WHO, 2016) contribute to higher risk. These risks to transgender prisoners, especially transgender women, are magnified quite considerably given they are commonly housed with cisgender men (Gatherer et al., 2014; United Nations Development Programme et al., 2016). For example, in the USA the classification of transgender inmates is frequently based on visual inspection of their genitalia upon intake, therefore pre-operative transgender women are placed in cisgender male prison housing according to sex assigned at birth irrespective of their gender identity (Routh et al., 2017; Scott, 2013).

In recent years, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer/questioning (LGBTIQ+) issues have gained legal and human rights acknowledgement in some (mainly Western) countries (Brömdal, 2008; Carroll & Mendos, 2017; Chiam, Duffy, & Gil, 2017; Government of UK, 2010; International Commision of Jurists, 2007; Transgender Europe, 2017). This raised awareness has resulted in initial moves to incorporate explicit policies and procedures to manage transgender prisoners within some more progressive prison systems (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2015; Blight, 2000; Carr, McAlister, & Serisier, 2016; Correctional Service Canada, 2017; Corrections Victoria Commissioner, 2017; Corrective Services NSW, 2015; Jenness, Maxson, Matsuda, & Sumner, 2007b; Ministry of Justice, 2016; National Institute of Corrections, 2013; National LGBTI Health Alliance, 2012; Queensland Corrective Services, 2017; UNAIDS, 2014; White Hughto et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017). Despite these recent acknowledgements, research suggests that prisoners who transgress heteronormative sex, sexuality and gender boundaries are at higher risk of experiencing bullying, violence, harassment, coercion, and sexual assault compared to other prisoners (Atabay, 2009; Australian Human Rights Commission, 2015; Blight, 2000; Carr et al., 2016; Dunn, 2013; Gatherer et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2011; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Jenness, Maxson, Matsuda, & Sumner, 2007a; Jenness et al., 2007b; Meyer et al., 2017; National LGBTI Health Alliance, 2012; UNAIDS, 2014; White Hughto et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017). For example, lesbian, gay, and bisexual prisoners are more likely to experience sexual assault than their heterosexual counterparts (from other inmates), and the likelihood is even greater for transgender women inmates (Beck, Berzofsky, Caspar, & Krebs, 2013; Blight, 2000; Clark et al., 2017; Carr et al., 2016; Jenness et al., 2007b; Oparah, 2012; von Dresner, Underwood, Suarez, & Franklin, 2013; White Hughto et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017). In a 2007 study, Jenness and colleagues reported that “sexual assault is 13 times more prevalent among transgender inmates, with 59% reporting being sexually assaulted while in a Californian prison” (Jenness et al., 2007b).

Other prisoners contribute to a large proportion of the violence, abuse, harassment and assault that transgender prisoners experience while in prison. However, a 2011 study of 6,454 transgender and gender non-conforming people in the USA found that among the 749 transgender women whom had been incarcerated, 38% reported they had been harassed, 9% physically assaulted, and 7% sexually assaulted by prison officers or staff (Grant et al., 2011). Similarly, transgender inmates from minority ethnic backgrounds experienced heightened prison officer harassment and physical or sexual assault compared to their Caucasian counterparts (Grant et al., 2011). Further, prison officers and health staff members often lack transgender-specific health knowledge, and regularly deny them general health care (Clark et al., 2017; Grant et al., 2011; Mullens et al., 2017; White Hughto et al., 2018).

Prison management and prison officers often play an important role in providing a safe, secure, and humane living environment that promotes the health and well-being of transgender inmates (United Nations Development Programme et al., 2016). However, providing a safe and secure living environment requires comprehensive policies and training for prison staff regarding how to treat, manage and support transgender prisoners consistent with anti-discrimination legal frameworks (Grant et al., 2011; Jenness et al., 2007a, 2007b; Sevelius & Jenness, 2017; White Hughto et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017). Despite the recent legal and policy acknowledgements in wider society and prison systems in a few countries (e.g., the USA, Australia, the UK, Italy, Canada), no systematic reviews known to the authors to date exist regarding the experiences of transgender prisoners (i.e., living conditions/environment; treatment by prisoners and correctional staff; availability of gender affirming health care; and housing) and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices concerning sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs transmission, while incarcerated. Originally it was planned to replicate the review process for prison officers however only three studies were uncovered, and it was felt that generalizability of findings would not be informative nor valid and was therefore not progressed as a second research aim.

The results from this systematic review will likely be of significant benefit to prison management and staff and transgender prisoner community members. Review and synthesis of findings may likely lead to better appreciation of the relevance in developing and/or enhancing educational programs, health promotion and policy procedures aimed at improving the lives of transgender prisoners while incarcerated. Through “best practice” strategies (Sevelius & Jenness, 2017) this review also aims to more effectively prepare prison staff for their roles in managing transgender prisoners, and also to enhance prisoners’ security, safety, health, and wellbeing.

Review question

The following question developed in consultation with transgender, sexual health/HIV and corrective services stakeholders has guided the systematic review: What are transgender and gender-diverse prisoners’ experiences in different prison settings and what are their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs?

Method

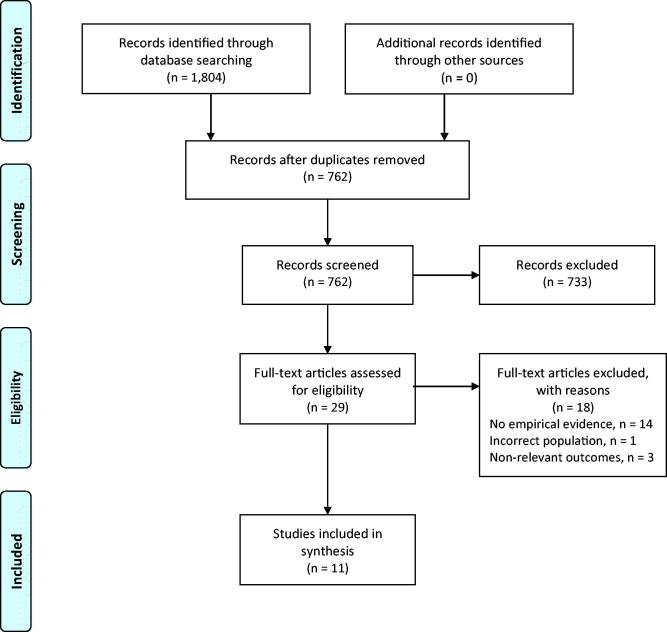

The systematic review was developed following the PRISMA statement recommendations (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO; registration number CRD42017073932 (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017073932). Each stage of the methodology was completed by two independent reviewers, TP and AB; and where discrepancies arose, reviewers AM and JG were consulted. The results of the search and progression of screening for the research question are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of review search.

Search strategy

The collection period occurred in August 2017. Searches were conducted in EBSCOhost MegaFile Ultimate, US National Library of Medicine National Institute of Health (PubMed), Web of Science Core Collection, and Scopus. Further, manual search of reference lists from eligible articles were conducted, consultation with experts in the field and identified authors or studies known to the review team were included. The search strategy included the terms “transgender” and “gender-diverse” populations, “prisoners”, “prison”, “prison officers”, and related synonyms (the full search strategy is available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPEROFILES/73932_STRATEGY_20170808.pdf). The search terms were adapted for use within each database in combination with database-specific filters/limiters.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible publications were peer-reviewed journal articles and e-book chapters written in English, available online for full-text download and published between January 2007 and August 2017. The specific publication period was selected as the non-binding Yogyakarta Principles were formulated in 2007, which set out for the first time the “Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity” (International Commision of Jurists, 2007). Specifically, Principle 9 which addresses a person’s human right to maintain dignity while incarcerated, stating “sexual orientation and gender identity are integral to each person’s dignity” (International Commision of Jurists, 2007).

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

The population studied were transgender and/or gender-diverse prisoners whom were incarcerated (including recently released); and

Data were reported on outcome measures relating to the research question under review.

Studies were excluded if they reported on transgender and gender-diverse persons whom had never been incarcerated, were reviews/literature reviews, conference abstracts, editorials, newspaper articles, opinions, preface, and brief communications, not accessible online in full text, not written in English or published earlier than 2007.

Screening

Screening was conducted in three stages: identification and removal of duplicate items, title and abstract screening, and full text screening. The initial screen identified duplicate items and they were removed accordingly. Reviewers TP and AB independently screened title/abstract against the inclusion criteria to determine eligibility for full text screening. Where eligibility was unclear from title/abstract, the full text was reviewed to establish eligibility. AM and JG confirmed eligibility, quality of articles and content of the data extraction.

Study quality

To assess the quality and strength of included studies, and reduce bias, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative and cohort studies was applied (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2017a, 2017b). Each study method received a quality rating corresponding to the number of quality criteria met, where high quality studies were awarded a score of five, good scored four, acceptable scored three, and modest scored two.

Strategy for data synthesis

The findings of included studies are reported as a systematic narrative synthesis that is consistent with PRISMA preferred reporting criteria, as a meta-analysis was not feasible (Shamseer et al., 2015). Information is presented in a results table and a synthesis textual approach to “tell the story” of included studies was employed (Popay et al., 2006). This is complemented with a qualitative descriptive methodology, as a meaningful description of the unique conditions experienced by transgender and gender-diverse prisoners was desired (Lambert & Lambert, 2012). The story of the findings is structured around transgender and gender-diverse prisoners’ experiences in different prison settings and their knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs. Further, the narrative synthesis compares and contrasts findings both within and between included studies.

Results

The initial electronic search of the databases resulted in a total of 1,804 references. After the removal of 1,042 duplicate records, the title and abstract of remaining 762 records were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine full-text screening eligibility. Of the 29 eligible articles, a total of 18 full-text articles were excluded while 11 (Figure 1) met these criteria and formed the final sample. No e-books were included. Data were extracted from each article to obtain structural information and content, year and place of publication, research methodology, number and description of study participants, and main results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of reviewed studies (n = 11).

| Author, year and QR | Country and location | Population | Housing | Study design | Prisoner experiences | Sexual behaviors KAP | HIV/STI KAP | Key findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative studies (n = 9) | |||||||||

| Beckwith et al. (2017) QR = high |

USA, Washington, DC |

n = 110 HIV infected individuals 64 men 6 women 20 transgender women Age M = 40 years (SD = 10.5) Ethnicity 85% Black 4% White 1% Hispanic 10% Other Sexual orientation of transgender women 45% Heterosexual 45% Homosexual 10% Bisexual |

30% District of Columbia central detention facility or correctional treatment facility. 70% Community or outreach member with recent incarceration. |

Larger study randomized, controlled, longitudinal trial. Stratified by gender. Feasibility and efficacy evaluation. |

– | P | P | Majority of transgender individuals had access to HIV treatment in prison, only one did not. Transgender sexual risk behaviors: exchange sex was sig. higher for transgender women compared to women; condomless sex pre-incarceration revealed majority (60%) transgender individuals engaged in safe sex. |

Limited representation of transgender individuals in sample. Outcome variables included data three months prior to last incarceration. |

| Brown (2014) QR = acceptable |

USA, 24 States |

n = 129 125 Transgender women 1 Transgender man 3 Intersex |

24 States: Department of Correction prisons or Federal Bureau of Prisons. |

Naturalistic, observational design. Unsolicited letters from transgender inmates to editor of Trans in Prison Journal. |

Yes | KAP | – | Frequent complaints of limited access to transgender health care and lack of competent evaluations for gender identity disorder/gender dysphoria diagnosis. Auto-castration had been attempted or completed by six inmates, which is a complication of untreated gender identity disorder. Frequent reports of sexual and physical abuse of transgender population. Suicidality linked to gender dysphoria feelings/frustrations were spontaneously reported by 8%, which is low and may be explained by the naturalistic design of the study. |

Naturalistic, observational design with a convenience sample is not generalizable to wider transgender inmate population. |

| Culbert (2014) QR = high |

USA, Illinois |

n = 42 38 HIV + men 4 HIV + transgender women or gender queer Recently released from male correctional centers Age M = 38.5 years (SD = 10.7) Ethnicity 88% Black 4% White 2% Hispanic 4% Other |

6 Community HIV Clinics: 5 University of Illinois Chicago, HIV Community Clinic Network and field stations of the Community Outreach Intervention Projects. 1 Corrections Continuity Clinic operated by Ruth M. Rothstein CORE Center. |

Ethnographic (social interaction) approach. Semi-structured in-depth face-to-face recorded interviews. | Yes | – | KAP | HIV disclosure represented a “social death” (p. 8) to transgender inmates in prison. Where interpersonal violence, stigma and search for social support was found to affect access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Transgender inmates who perceive threats to their safety and privacy withheld disclosure. Thus, lack of confidentiality and safety deter transgender inmates from disclosing their HIV status and seeking treatment. |

Self-selection bias as only participants willing to be voice recorded were included. Selection of male correctional facilities only excluded representation of transgender men, thus only generalizable to HIV positive transgender women or gender queer population. |

| Dolovich (2011) QR = acceptable |

USA, California |

n = 32 Transgender women and MSM Ethnicity 39.4% Black 27.3% White 30.3% Latino 2.89% Other |

Los Angeles County Jail, segregated K6G Unit. |

Observational design. In-depth structured one-on-one recorded interviews with random sample. |

Yes | KAP | – | Strategic segregation of sexual minorities in K6G increased inmates subjective experience of safety from physical assault, sexual assault, sexual harassment. Inmates “subjectively feel safer” (p. 47) in K6G compared to general prison population. | Gender identity characteristics were not reported. Not generalizable to other prisons populations outside K6G. |

| Jenness and Fenstermaker (2014) QR = modest |

USA, California |

n = 315 Transgender women |

27 California prisons for men. | Face-to-face interviews. Self-report data Official data. Drawn from a larger project. |

Yes | KAP | KAP | Transgender inmates in prison are identifiable and do not hide their preferred identity. The powerful heteronormative masculine environment context explains their pursuit of femineity and the desire to conform to a normative gender expectation. The search for gender authenticity is fundamentally a pursuit of recognition, respect, and belonging. | Gender authenticity was not ascribed by all transgender prisoners. |

| Rosenberg and Oswin (2015) QR = good |

USA, California, Texas and Florida |

n = 23 Transgender persons Identification 12 transgender 8 transsexual 6 women 5 gender queer Ethnicity 10 White 4 Black 9 Other |

Men’s correctional facilities: State prisons, pre-transitional centers, state correctional institutions, federal correctional complexes, county jails, and US penitentiaries. |

Questionnaire via mail. Arts-based inquiry. Strategic and snowball sampling. |

Yes | P | – | Transgender inmates endured harsh conditions of confinement, including enforced masculine gender norms, denied access to hormone and medical treatments; experience assault, harassment, social isolation and sexual violence. | Sample bias prisoners who were illiterate or had poor writing ability were excluded. Lack of transgender men. Possibility of mail being intercepted was unavoidable. |

| Sumner and Sexton (2016) QR = high |

USA, Pennsylvania |

n = 37 27 prisoners 10 transgender prisoners 20 prison staff Prisoners: Age M = 41 years Ethnicity 55.6% Black 27.8% White 8.3% Hispanic 8.3% Other Prison staff: 94.7% White 5.3% Black |

4 Pennsylvania prisons for men. | In-depth interviews with transgender prisoners. Focus group with random sample of non-transgender prisoners. Focus groups and individual interviews with purposive sample of prison staff. |

Yes | – | – | Transgender prisoners are different to general population prisoners. They are highly stigmatized against, exposed to discrimination, hate, resentment and demeaning treatment. Scrutinized by staff and prisoners. Being transgender was often fused with homosexuality. Demonstrating willingness to fight back provided transgender prisoners some protection from violence and victimization. | Gender classification may not have identified all eligible transgender prisoners. |

| Wilson et al. (2017) QR = good |

Australia, New South Wales |

n = 7 transgender women Age range 20 to 47 years Ethnicity 2 Australian-Aboriginal 5 Anglo-Australian |

New South Wales prisons. 7 community organizations. 2 incarcerated in women’s prison and men’s prison 5 incarcerated in men’s prisons (majority in protective custody). |

Semi-structured interviews. Purposive and chain-referral sampling. |

Yes | KAP | – | Transgender negotiation of sexual safety in prison is complex. The experience of rape and/or witnessing violent rape, sexual harassment, and coercive threats may impact transgender psychological and social well-being. In contrast, findings suggest there are elements of pleasure and ease, including perceptions of having a tradable (transactional) asset, namely sex. | Transgender men were not represented. Small sample size. |

| Yap et al. (2011) QR = good |

Australia, New South Wales |

n = 40 33 men 7 transgender women Age range 20 to 60 years Ethnicity 31 Anglo-European 6 Aboriginal / Aboriginal-European 3 Other |

New South Wales men’s and women’s prisons. | Exploratory study. Snowball (prisons) and purposive (community) sampling strategy. Face-to face open-ended interviews. |

Yes | KAP | – | Reported decrease in sexual and physical violence due to (a) increase in prison surveillance (b) different attitudes of new generation criminals/prisoners. Transgender women and effeminate male inmates still greatly experience sexual harassment and are vulnerable to sexual assault if unpartnered for protection or are alone in an area unmonitored by security cameras or prison officers, such as laundries and showers. |

Small sample of transgender women only. |

| Quantitative studies (n = 1) | |||||||||

| Jaffer et al. (2016) QR = acceptable |

USA, New York City |

n = 27 25 transgender women 2 transgender men |

12 New York City Jail clinics. | In-person survey. Review of transgender health care related complaints. |

Yes | – | – | Transgender inmate’s primary complaint was inability to obtain hormone therapy and almost one third of complaints were not resolved. Further, complaints by almost all transgender inmates indicated health staff require more training and sensitivity towards transgender inmates. The impact of LGBT training for health staff reduced complaints by 50%, 3 months post-training and after training was revised, no complaints reported at six months post-training. All transgender inmates stressed the need for separate transgender housing and 96% believe “housing criteria should be based on self-identity” (p. 118) |

Small sample size. Non-hormone treatment transgender inmates were not represented. Lack of pre-intervention survey. |

| Mixed methods studies - qualitative and quantitative (n = 1) | |||||||||

| Harawa et al. (2010) QR = high |

USA, California |

n = 101 80 MSM 19 transgender wome Age range 18 to 79 years Median =37 years Ethnicity 22 White 33 Black 36 Hispanic 10 Other |

Los Angeles County Jail, segregated K6G Unit. |

Quantitative Survey. Qualitative in-depth semi-structured interviews (n = 17). Random sample of K6G inmates. |

Yes | KAP | KAP | K6G inmates are a high-risk population for HIV/STI. Due to condom program (weekly access to condoms), 49% of sexual acts were protected. However, reported inadequate condom provisions as well as diminished sexual pleasure, spontaneity, monogamy and HIV seroconcordance contributed to condom nonuse within this population. | Pre-test of survey instrument was not possible. Participants reported previous as well as current incarceration and others grouped transgender and male sexual partners. Not generalizable to other prisons populations outside K6G. |

K: knowledge; A: attitudes; P: practices; QR: quality rating; USA: United States of America; K6G: keep-away designation 6G protective custody unit; MSM: men who have sex with men.

Study quality

The evidence reviewed was generally of moderate to high quality. The quality ratings for included studies are presented in Table 1. Four studies were of high quality (Beckwith et al., 2017; Culbert, 2014; Harawa, Sweat, George, & Sylla, 2010; Sumner & Sexton, 2016); three were good (Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015; Wilson et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2011); three were acceptable (Brown, 2014; Dolovich, 2011; Jaffer et al., 2016); while one was modest and was retained (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014). The richness of the qualitative data reported in Jenness and Fenstermaker (2014) was deemed to enhance findings for this systematic review.

Findings

Table 1 summarizes the name, study design definitions, and descriptors used across the 11 studies (nine qualitative, one quantitative, one mixed-methods; nine in USA, and two in Australia) which met the criteria for inclusion.

Experiences

Eleven studies reported on the experiences of transgender and gender-diverse prisoners with the most frequent themes cited comprising the categories of treatment by prisoners and correctional staff; gender affirming and other health care; living conditions/environment and procedural mistreatment; and housing.

Treatment by prisoners and correctional staff

Frequent themes of interpersonal violence, including sexual assault (Brown, 2014; Culbert, 2014; Dolovich, 2011; Jaffer et al., 2016; Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015; Sumner & Sexton, 2016; Wilson et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2011); lack of respect/sensitivity, discrimination, mistreatment, harassment, or stigma from prison staff and other prisoners related to gender and/or sexuality – including homophobia was reported (Brown, 2014; Culbert, 2014; Dolovich, 2011; Jaffer et al., 2016; Sumner & Sexton, 2016; Yap et al., 2011). Prisoners also reported a lack of knowledge and confusion among prison staff and fellow prisoners regarding “gender-diversity” (beyond a heteronormative understanding of the gender binary), and lack of understanding of how gender identity and expression is related to yet distinct from sexual orientation (Sumner & Sexton, 2016); “they think I’m gay or a gay boy” (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014). However, a minority of participants reported increased awareness and acceptance of sexual- and gender-diversity over time and a decline in sexual assaults, which contradicts some of the results found in other studies that were reviewed (Yap et al., 2011); and experiences of not having been victimized as the prisoners were deemed “at risk” populations housed in a specific unit (“keep-away designation 6G” or K6G) within the men’s central jail for men who have sex with men and transgender women only, to ensure their safety from the male general population (Dolovich, 2011).

Gender affirming and other health care

Lack of access to adequate medical treatment for gender affirming health care, other transgender-related concerns (e.g., gender dysphoria) and HIV management were frequently reported (Brown, 2014; Dolovich, 2011; Jaffer et al., 2016; Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015). Furthermore, perceived vulnerability and heightened mental health issues were, in some cases, associated with secondary harm (Brown, 2014; Dolovich, 2011; Harawa et al., 2010; Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015; Wilson et al., 2017). Examples of this secondary harm was linked to prisoners engaging in self-harm such as self-treatment as an attempt to cope with their gender dysphoria (e.g., “self-castration”; Brown, 2014), attempting suicide, exaggerating mental health symptomatology or refusing medication in an attempt to receive medical attention (Brown, 2014).

Living conditions/environment and procedural mistreatment

Further themes less frequently discussed included inability to express sexuality for fear of mistreatment and victimization (Dolovich, 2011), high standards and consequences imposed for strict gender regulation associated with birth gender (Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015), and secondary punishment and victimization if not strictly adhering to heteronormative expressions of sexuality and/or gender (Brown, 2014; Sumner & Sexton, 2016). Brown and colleagues cited the following excerpt from a gender-diverse prisoner “[A prison officer] is condemning me and reprimanding me for being a transgender. Saying it was unnatural and he would write me up for sexual misconduct if I continued to be this way” (Brown, 2014).

Housing

Conflicting views were reported regarding segregated housing based on gender and whether this reduces or heightens perceived vulnerability and stressors (Brown, 2014; Dolovich, 2011; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014). Regardless, there are distinct challenges for transgender women inmates living in male or female facilities (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Wilson et al., 2017), with some participants strongly endorsing separate transgender housing (Dolovich, 2011; Jaffer et al., 2016). Similarly, when considering whether transgender women prisoners would prefer to be housed in a women’s prison or a men’s prison, some reported strong preference of being housed with men because “women…are vicious. They are worse than men. Their hormones are going all the time” (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014), while others reported feeling safer and less intimidated in women’s prisons (Wilson et al., 2017).

Other themes identified at lesser frequency included legal issues, and policy shortcomings or implications (Brown, 2014; Jaffer et al., 2016; Sumner & Sexton, 2016; Wilson et al., 2017). Thus, individual perceptions and lack of adequate policies regarding how to most effectively manage gender-diverse prisoners can result in their further victimization (e.g., being more likely to be put into protective custody which may result in more perceived harm than benefit; “z-code” assigned single-cell housing; Sumner & Sexton, 2016). It should be noted that evidence included in this review and reported elsewhere in the literature regarding transgender women inmates housed in female facilities is scant, however differences have been noted between gender-diverse people detained in male versus female settings – on topics such as status, identity, relationships, and/or victimization (Brown, 2014; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014).

Sexual behaviors and sexual violence

Compared to the experiences of transgender and gender-diverse prisoners, evidence regarding sexual behaviors (knowledge, attitudes, and practices) was more limited. In addition to previously mentioned themes of interpersonal violence, including sexual assault (noted above; e.g., Culbert, 2014), further sexual behaviors discussed included: sexual practices (frequency, partner characteristics, types of sexual practices, sexual risk-taking/condom use; Beckwith et al., 2017; Harawa et al., 2010), contexts of sexual activity (Harawa et al., 2010), reasons for having sex (e.g., boredom, pleasure, exchange sex; Beckwith et al., 2017; Harawa et al., 2010; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Wilson et al., 2017), and reasons for avoiding/abstaining sex (Harawa et al., 2010). Conversely, “psychosocial reasons” were also associated with reported reluctance to use condoms, such as “perceived HIV seroconcordance with one’s partner” when engaging in anal sex, disliking the ways in which condoms feel, and how condoms had a negative impact on “maintaining an erection” (Harawa et al., 2010).

Significant complexities were noted within sexual and intimate relationships (see Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014), with some participants reporting seeking relationships as a means of protection to reduce the likelihood of assault or victimization from other prisoners (Wilson et al., 2017). There were other accounts of increased susceptibility to harassment or violence when declining sexual or relationship advances from other prisoners (Sumner & Sexton, 2016; Wilson et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2011). These dynamics were reported as both protective and further victimizing. Examples of further victimization include the actual possibility of being physically abused: “If I do that [decline] then they get stroppy, and then sometimes you might be bashed” (Wilson et al., 2017). The ongoing fear and effects of chronic sexual harassment may further negatively impact the psychological wellbeing of the victims (Wilson et al., 2017). Further complexities were reported among some participants that being transgender was associated with heightened status and privilege and greater perceived sexual safety or protection (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Sumner & Sexton, 2016). “I’ve been lucky to have guys who look at me as female and then they want to take care of me” (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014). Other prisoners reported resorting to perpetuating violence themselves to reduce vulnerability associated with their gender identity (Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Sumner & Sexton, 2016).

Participants in many studies reported on complex sexual relationships whereby coercive and transactional sex were engaged in an attempt to facilitate survival, as adaptive to and to cope with vulnerabilities (Harawa et al., 2010; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Wilson et al., 2017). Others note that sex seemed consensual at the time, and later realized they were attempting to keep themselves safer (Wilson et al., 2017). Further related themes included: forced sex due to sexual identity (Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015), being “sold for sex” and “exchange sex” (higher among transgender women; Beckwith et al., 2017). Overt attempts were made to avoid sexual assault (e.g., remaining in videoed surveillance areas monitored by custodial staff; Yap et al., 2011), and perceptions of reduced likelihood of sexual assault when housed in a segregated unit for at risk populations, namely men who have sex with men and transgender women inmates (Dolovich, 2011).

HIV/STIs prevention and management

Discussion of HIV/STIs was further limited compared to other topics within this review, and tended to focus solely on HIV issues, including challenges and barriers to accessing HIV treatment and maintaining adherence (Beckwith et al., 2017; Culbert, 2014), and lack of sufficient access to prevention (condoms) within prisons (Harawa et al., 2010). Those recently diagnosed or living with HIV reported further challenges regarding stigma, discrimination, mistreatment, and victimization, representing further marginalization (Culbert, 2014; Wilson et al., 2017). In an attempt to reduce victimization, HIV-infected prisoners would also reportedly hide HIV medications or not disclose their status while in jail (Culbert, 2014).

Discussion

The results of the systematic review reveal limited empirical evidence on prison programmatic activities which explicitly involve the management of transgender and gender-diverse prisoners that ameliorate their experiences of stigma, mistreatment, and violence; provide appropriate living conditions (housing based on gender identity versus sex assigned at birth); and gender affirming health care. Moreover, there is a low number of published studies which satisfy the inclusion criteria for the review. However, further data may be available in studies prior to 2007 and within the gray literature and would be a useful target for future investigation. Another key feature of the results is the very narrow geographical settings in which programs and studies are being conducted. More specifically, being reflective of only two countries (USA and Australia), the literature addressing the research question is limited to 11 studies.

Almost uniformly transgender prisoners experience stigma and discrimination in their everyday lives while incarcerated (Brown, 2014; Culbert, 2014; Dolovich, 2011; Harawa et al., 2010; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2014; Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015; Wilson et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2011). This stigma comes from other prisoners, prison officers and health care providers (Dolovich, 2011; Hagner, 2010; Sumner & Sexton, 2016) as reported elsewhere (Atabay, 2009; Gatherer et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2011; Jenness et al., 2007a; Scott, 2013; Clark et al., 2017; White Hughto et al., 2018). The reported lack of general, mental and gender affirming health care may be the result of numerous barriers, such as structural stigma, heteronormative culture, and lack of staff with specialized training, prompting urgent attention for the development of interventions to address this significant gap in the health care of transgender and gender-diverse prisoners (Clark et al., 2017; White Hughto et al., 2018). Hyper-heteronormative behaviors are the norm in male prisons and transgender prisoners experience this aggression and violence on a regular basis (Lara, 2010; Reisner, Bailey, & Sevelius, 2014; Robinson, 2011; Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015; Sumner & Sexton, 2015; Wilson et al., 2017). Threats of rape and forced sex (Dolovich, 2011; Hagner, 2010; Jenness & Fenstermaker, 2016; Lara, 2010; Rosenberg & Oswin, 2015; Wilson et al., 2017) make transgender prisoners much more susceptible to HIV/STIs transmission (Atabay, 2009) and inadequate prevention methods, both physical protection by prison officers and barrier methods by ease of condom availability, increase greatly their risk of HIV/STIs transmission (Harawa et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2017). Nevertheless, a minority of participants were housed in prisons that implemented either higher security measures, such as security cameras in showers and laundries (Yap et al., 2011), or segregated units (Dolovich, 2011) and demonstrate promise of what can be achieved when evidence-based change occur within correctional policy and procedures.

Limitations of this review

The current review was limited due to several reasons. The most critical was the very limited research in this area available internationally, of which findings were even more scant in relation to prison staff as compared to transgender and gender-diverse prisoners. Additionally, one article of ‘modest’ acceptability was deemed by the research team to be included as it provided relevant quotations to the topics of interest and was based on previously published work. Only data from two countries were represented, which limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts. All studies had very small numbers of participants which makes generalization problematic. Further, views from and regarding transgender men were particularly limited across the studies – which in part may reflect demographic characteristics within prisons as well as less definitive or clear categorization (as evidenced by reports from other prisoners and staff members, lack of clarity around gender identity and sexual orientation as related, but distinct constructs; or simply “systematic error” in measurement of gender as binary; Valcore & Pfeffer, 2018). Inclusion criteria solely regarding published literature may limit understanding of possible existing data within the gray literature and other databases not searched. Further limitations include missed studies published in non-English languages or not cited in searched databases.

Conclusions

The experiences of transgender prisoners within this sample are almost uniformly poor with stigma, discrimination, violence, and sexual exploitation commonly reported. This increases the risks transgender prisoners face in conducting their sexual lives and exposes them to higher risks of HIV/STIs transmission. Contemporary evidence of best practice management of transgender prisoners in the prison system is limited and as such warrants further attention. Prison policy changes that focus on appropriate gender classification, housing and increased access to gender affirming health care are sorely needed. The knowledge and attitudes of many prison officers towards transgender and gender-diverse prisoners, sexual practices and HIV/STIs risks within corrective sites reflects the heteronormative domination of societies. This dismissal of “otherness” results in increased levels of violence (or threats) towards transgender prisoners from both other prisoners and prison officers. The literature on transgender and gender-diverse prisoners, their experiences and management by prison authorities is extremely limited. This lack of discussion may reflect the difficulty in accessing transgender and gender-diverse prisoners for research due to a number of barriers. Ethical barriers may include the difficulty in obtaining appropriate permissions from research ethics committees and/or correctional institutions themselves, due to the controversial nature of pursuing research with this highly vulnerable population (Adams et al., 2017; Apa et al., 2012). Some institutional barriers may be grounded in the prison systems’ lack of familiarity with the research team, conflicting perspectives regarding research objectives and/or lack of willingness to “develop a collaborative research relationship” (Apa et al., 2012; Watson & van der Meulen, 2018). Some of these institutional hurdles may be further embedded in an absence of mutual goals or incompatible methodological aspects of proposed studies due to the specific needs and culture within correctional institutions and potential fear of “exposure” resulting in possible negative press or institutional reviews among correctional facilities (Apa et al., 2012; Watson & van der Meulen, 2018). These barriers may collectively restrict researchers, although if overcome they equally present themselves as opportunities to access transgender and gender-diverse prisoners and signify an important research gap that warrants further investigation.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the HIV Foundation Queensland (Project ID 2017-20).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the feedback of Dr Mandy Cassimatis, Dr Joseph Debattista and Heidi Ellis for reviewing the research questions and protocol guiding the systematic review. We would also like to thank Rowena McGregor, USQ Liaison librarian for Health Sciences, for assisting us throughout the systematic review process and identifying appropriate databases, and a number of Queensland prison staff members for providing general information helping to guide the systematic review.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Adams N., Pearce R., Veale J., Radix A., Castro D., Sarkar A., & Thom K. C (2017). Guidance and ethical considerations for undertaking transgender health research and institutional review boards adjudicating this research. Transgender Health, 2(1), 165–175. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apa Z. L., Bai R. Y., Mukherejee D. V., Herzig C. T. A., Koenigsmann C., Lowy F. D., & Larson E. L (2012). Challenges and strategies for research in prisons. Public Health Nursing, 29(5), 467–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2012.01027.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atabay T. (2009). Handbook on prisoners with special needs. Vienna: United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2015). Resilient individuals: Sexual orientation, gender identity & intersex rights. Retrieved from https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/SOGII%20Rights%20Report%202015_Web_Version.pdf

- Banbury S. (2004). Coercive sexual behaviour in British prisons as reported by adult ex-prisoners. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(2), 113–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2311.2004.00316.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S. D., Poteat T., Strömdahl S., Wirtz A. L., Guadamuz T. E., & Beyrer C (2013). Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 13(3), 214–222. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. J., Berzofsky M., Caspar R., & Krebs C (2013). Sexual victimization in prisons and jails reported by inmates, 2011–12 (NCJ241399). Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/svpjri1112.pdf

- Beckwith C., Castonguay B. U., Trezza C., Bazerman L., Patrick R., Cates A., … Kuo I (2017). Gender differences in HIV care among criminal justice-involved persons: Baseline data from the care plus corrections study. PLoS ONE, 12(1), 15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C., Kamarulzaman A., & McKee M (2016). Prisoners, prisons, and HIV: Time for reform. The Lancet, 388(10049), 1033–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30829-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blight J. (2000). Transgender inmates: Trends and issues in crime and criminal justice (168). Retrieved from http://aic.gov.au/media_library/publications/tandi_pdf/tandi168.pdf

- Blondeel K., de Vasconcelos S., García-Moreno C., Stephenson R., Temmerman M., & Toskin I (2018). Violence motivated by perception of sexual orientation and gender identity: A systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 96(1), 29–41L. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.197251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal A. (2008). Intersex: A challenge for human rights and citizenship rights. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. R. (2014). Qualitative analysis of transgender inmates’ correspondence: Implications for departments of. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 20(4), 334–342. doi: 10.1177/1078345814541533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A., & Mendos L. R (2017). State sponsored homophobia 2017: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: Criminalisation, protection and recognition. Retrieved from https://www.ilga.org/downloads/2017/ILGA_State_Sponsored_Homophobia_2017_WEB.pdf

- Carr N., McAlister S., & Serisier T (2016). Out on the inside. The rights, experiences and needs of LGBT people in prison. Retrieved from http://www.iprt.ie/files/IPRT_Out_on_the_Inside_2016_EMBARGO_TO_1030_Feb_02_2016.pdf

- Chiam Z., Duffy S., & Gil M. G (2017). Trans legal mapping report: Recognition before the law. Retrieved from https://www.ilga.org/downloads/ILGA_Trans_Legal_Mapping_Report_2017_ENG.pdf

- Clark K. A., White Hughto J. M., & Pachankis J. E (2017). “What’s the right thing to do?” Correctional healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences caring for transgender inmates. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 193, 80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correctional Service Canada (2017). Gender dysphoria (800-5). Canada: Correctional Service Canada; Retrieved from http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/acts-and-regulations/800-5-gl-eng.shtml#s4 [Google Scholar]

- Corrections Victoria Commissioner (2017). Commissioner’s requirement: Management of prisoners who are trans, gender diverse or intersex. (CR No 2.4.1). Melbourne: Corrections, Prisons & Parole; Retrieved from http://assets.justice.vic.gov.au/corrections/resources/9dd194b0-3358-4c32-bb52-9f7393e8d08/2.4.1management_prisoners__genderdiverse_intersexv7.docx [Google Scholar]

- Corrective Services NSW (2015). Corrective services NSW operations procedures manual: Section 7.23 management of transgender and intersex inmates. (OPM 7.23). Sydney: Corrective Services NSW; Retrieved from http://www.correctiveservices.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/custodial-op-proc-manual/OPM%20Sec%207.23%20Management%20of%20Transgender%20and%20Intersex%20inmates%20v2.0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2017a). CASP cohort study checklist. Retrieved from http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_5ad0ece77a3f4fc9bcd3665a7d1fa91f.pdf

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2017b). CASP qualitative checklist. Retrieved from http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf

- Culbert G. J. (2014). Violence and the perceived risks of taking antiretroviral therapy in US jails and prisons. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 10(2), 94–110. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-05-2013-0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P., & Horton R (2016). On both sides of the prison walls - prisoners and HIV. Lancet, 388(10049), 1032–1033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30892-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolovich S. (2011). Strategic segregation in the modern prison. American Criminal Law Review, 48(1), 1–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn P. (2013). Slipping off the equalities agenda? Work with LGBT prisoners. Prison Service Journal, 206, 3–10. doi: 10.1080/02589340120091655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Equality Act 2010 (UK.) (2015). Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/pdfs/ukpga_20100015_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gatherer A., Atabay T., & Hariga F (2014). Prisoners with special needs In Enggist S., Møller L., Galea G., & Udesen C. (Eds.), Prisons and health (pp. 151–158). Copenhagen: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Goyer K. C., & Gow J (2001a). Confronting HIV/AIDS in South African prisons. Politikon: South African Journal of Political Studies, 28(2), 195–206. doi: 10.1080/02589340120091655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer K. C., & Gow J (2001b). Transmission of HIV in South African prisoners: Risk variables. Society in Transition, 32(1), 128–132. doi: 10.1080/21528586.2001.10419037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. M., Mottet L., Tanis J. E., Harrison J., Herman J., & Keisling M (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]

- Hagner D. (2010). Fighting for our lives: the D.C. Trans Coalition's campaign for humane treatment of transgender inmates in District of Columbia correctional facilities. Georgetown Journal of Gender & the Law, 11(3), 837–867. Retrieved from https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/grggenl11&div=36&id=&page= [Google Scholar]

- Harawa N. T., Sweat J., George S., & Sylla M (2010). Sex and condom use in a large jail unit for men who have sex with men (MSM) and male-to-female transgenders. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 21(3), 1071–1087. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Commision of Jurists (2007). Yogakarta Principles - Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity. Retrieved from http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/principles_en.pdf

- Jaffer M., Ayad J., Tungol J. G., Macdonald R., Dickey N., & Venters H (2016). Improving transgender healthcare in the New York City correctional system. LGBT Health, 3(2), 116–121. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness V., & Fenstermaker S (2014). Agnes goes to prison: Gender authenticity, transgender inmates in prisons for men, and pursuit of “the real deal”. Gender & Society, 28(1), 5–31. doi: 10.1177/0891243213499446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness V., & Fenstermaker S (2016). Forty years after Brownmiller: Prisons for men, transgender inmates, and the rape of the feminine. Gender & Society, 30(1), 14–29. doi: 10.1177/0891243215611856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness V., Maxson C. L., Matsuda K. N., & Sumner J. M (2007a). Violence in California correctional facilities: An empirical examination of sexual assault. Retrieved from http://ucicorrections.seweb.uci.edu/files/2013/06/PREA_Presentation_PREA_Report_UCI_Jenness_et_al.pdf

- Jenness V., Maxson C. L., Matsuda K. N., & Sumner J. M (2007b). Violence in California correctional facilities: An empirical examination of sexual assault. Bulletin, 2(2), 1–4. Retrieved from http://ucicorrections.seweb.uci.edu/files/2013/06/BulletinVol2Issue2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2014). Services for people in prisons and other closed settings. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2014_guidance_servicesprisonsettings_en.pdf

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (2015). UNAIDS terminology guidelines - 2015. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2015/2015_terminology_guidelines

- Lambert V. A., & Lambert C. E (2012). Qualitative descriptive research: An acceptable design. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 16(4), 255–256. Retrieved from https://www.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/PRIJNR/article/download/5805/5064 [Google Scholar]

- Lara A. (2010). Forced integration of gay, bisexual and transgendered inmates in California state prisons: From protected minority to exposed victims. Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal, 19(3), 589–614. Retrieved from http://www-bcf.usc.edu/∼idjlaw/PDF/19-3/19-3%20%20Lar.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mahon N. (1996). New York inmates' HIV risk behaviors: The implications for prevention policy and programs. American Journal of Public Health, 86(9), 1211–1215. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.9.1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. H., Flores A. R., Stemple L., Romero A. P., Wilson B. D., & Herman J. L (2017). Incarceration rates and traits of sexual minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 267–273. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice (2016). The care and management of transgender offenders. (AI 13/2016; PSI 17/2016; PI 16/2016). London: National Offender Management Service; Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/offenders/psipso/psi-2016/PSI-17-2016-PI-16-2016-AI-13-2016-The-Care-and-Management-of-Transgender-Offenders.docx [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., & Altman D. G (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullens A. B., Fischer J., Stewart M., Kenny K., Garvey S., & Debattista J (2017). Comparison of government and non-government alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment service delivery for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) Community. Substance Use Misuse, 52(8), 1027–1038. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1271430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Corrections (2013). Policy review and development guide: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex persons in custodial settings (027507). Retrieved from https://info.nicic.gov/sites/info.nicic.gov.lgbti/files/lgbti-policy-review-guide-2_0.pdf

- National LGBTI Health Alliance (2012). Diversity in health: Improving the health and well-being of transgender, intersex and other sex and gender diverse Australians. Retrieved from http://www.lgbtihealth.org.au/sites/default/files/Diversity%20In%20Health%20Report%20FINALOnline.pdf

- Oparah J. C. (2012). Feminism and the (trans)gender entrapment of gender nonconforming prisoners. UCLA Women's Law Journal, 18(2), 239–271. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sp664r9 [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Roberts H., Sowden A., Petticrew M., Arai L., Rodgers M., … Duffy S (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mark_Rodgers4/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme/links/02e7e5231e8f3a6183000000/Guidance-on-the-conduct-of-narrative-synthesis-in-systematic-reviews-A-product-from-the-ESRC-Methods-Programme.pdf

- Queensland Corrective Services (2017). Deputy commissioner instruction: Transgender prisoner management. Brisbane: Queensland Corrective Services. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S. L., Bailey Z., & Sevelius J (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S. Women and Health, 54(8), 750–767. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.932891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R. K. (2011). Masculinity as prison: Sexual identity, race, and incarceration. California Law Review, 99(5), 1309–1408. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com.au/&httpsredir=1&article=2760&context=facpubs [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg R., & Oswin N (2015). Trans embodiment in carceral space: Hypermasculinity and the US prison industrial complex. Gender Place and Culture, 22(9), 1269–1286. doi: 10.1080/0966369x.2014.969685 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Routh D., Abess G., Makin D., Stohr M. K., Hemmens C., & Yoo J (2017). Transgender inmates in prisons: A review of applicable statutes and policies. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(6), 645–666. doi: 10.1177/0306624X15603745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliu A., & Akintunde B (2014). Knowledge, attitude, and preventive practices among prison inmates in Ogbomoso prison at Oyo State, South West Nigeria. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 2014, 1–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/364375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S. (2013). “One is not born, but becomes a woman”: A fourteenth amendment argument in support of housing male-to-female transgender inmates in female facilities. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law, 15(4), 1259–1297. Retrieved from https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ upjcl15&i = 1279 [Google Scholar]

- Sevelius J., & Jenness V (2017). Challenges and opportunities for gender-affirming healthcare for transgender women in prison. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 13(1), 32–40. doi: 10.1108/ijph-08-2016-0046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., … Stewart L. A (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349(jan02 1), g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoove M. (2016). It's time: A case for trialling a needle and syringe program in Australian prisons. HIV Australia, 14(1), 6 Retrieved from https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=996476799867348;res=IELHEA [Google Scholar]

- Sumner J., & Sexton L (2015). Lost in translation: Looking for transgender identity in women’s prisons and locating aggressors in prisoner culture. Critical Criminology, 23(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10612-014-9243-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner J., & Sexton L (2016). Same difference: The ‘dilemma of difference’ and the incarceration of transgender prisoners. Law & Social Inquiry, 41(3), 616–642. doi: 10.1111/lsi.12193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Transgender Europe (2017). Trans rights Europe map & index 2017. Retrieved from https://tgeu.org/trans-rights-map-2017/

- Todts S. (2014). Infectious diseases in prison In Enggist S., Møller L., Galea G., & Udesen C. (Eds.), Prisons and health (pp. 73–77). Copenhagen: World Health Organization; Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/128603/1/Prisons%20and%20Health.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme, IRGT: A Global Network of Transgender Women and HIV, United Nations Population Fund, UCSF Center of Excellence for Transgender Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, World Health Organization, … United States Agency for International Development (2016). Implementing comprehensive HIV and STI programmes with transgender people: Practical guidance for collaborative interventions. Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/hiv-aids/implementing-comprehensive-hiv-and-sti-programmes-with-transgend.html

- U.S. Department of Justice. (2012) National standards to prevent, detect, and respond to prison rape: Final rule 2012. Retrieved from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2012-06-20/pdf/2012-12427.pdf [PubMed]

- Valcore J. L., & Pfeffer R (2018). Systemic error: Measuring gender in criminological research. Criminal Justice Studies, 31(4), 1–19. doi: 10.1080/1478601X.2018.1499022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Dresner K. S., Underwood L. A., Suarez E., & Franklin T (2013). Providing counseling for transgendered inmates: A survey of correctional services. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 7(4), 38–44. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2013-10410-010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Watson T. M., & van der Meulen E (2018). Research in carceral contexts: confronting access barriers and engaging former prisoners. Qualitative Research, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/1468794117753353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto J. M., Clark K. A., Altice F. L., Reisner S. L., Kershaw T. S., & Pachankis J. E (2018). Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: A qualitative study of transgender women’s healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 14(2), 69–88. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-02-2017-0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M., Simpson P. L., Butler T. G., Yap L., Richters J., & Donovan B (2017). ‘You’re a woman, a convenience, a cat, a poof, a thing, an idiot’: Transgender women negotiating sexual experiences in men’s prisons in Australia. Sexualities, 20(3), 380–402. doi: 10.1177/1363460716652828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2016). Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations–2016 update. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/246200/1/9789241511124-eng.pdf [PubMed]

- Yap L., Richters J., Butler T., Schneider K., Grant L., & Donovan B (2011). The decline in sexual assaults in men’s prisons in New South Wales: A “systems” approach. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(15), 3157–3181. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]