Abstract

Background: Prejudice against transgender people is widespread, yet in spite of the prevalence of this negativity relatively little is known about the antecedents and predictors of these attitudes. One factor that is commonly related to prejudice is religion, and this is especially true for prejudice targets that are considered to be “value violating” (as is the case for transgender individuals).

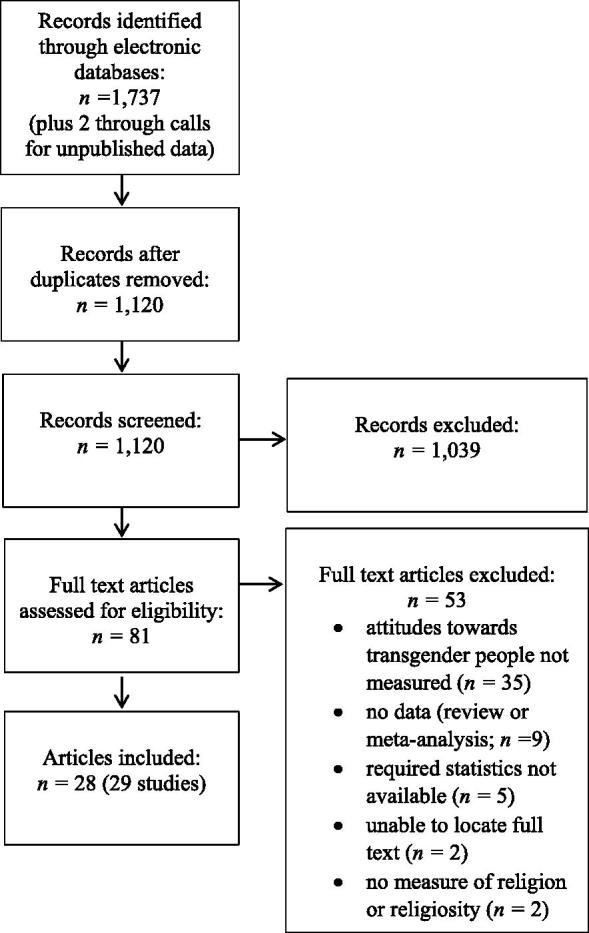

Method: In this paper, we present the findings of our systematic search of the literature on this topic and present the synthesized evidence. Our search strategy was conducted across five databases and yielded 29 studies (across 28 articles).

Results: We found consistent evidence that self-identifying as with either being “religious” or as Christian (and to a lesser extent, being Muslim) was associated with increased transprejudice relative to being nonreligious (and to a lesser extent, being Jewish). Additionally, we found consistent evidence that certain forms of religiosity were also related to transprejudice – specifically religious fundamentalism, church attendance, and interpretations of the bible as literal (transprejudice was unrelated to religious education).

Conclusion: Although this young, but important field of research is growing, more empirical exploration is needed to fully understand that nuances of the religion-transprejudice relationship.

Keywords: Prejudice, Religious affiliation, Religiosity, Sexual Prejudice, Transphobia, Transprejudice

Public awareness and the visibility of transgender and gender-variant individuals has increased in recent times, with a significant rise in public discussions concerning transgender issues over the last decade (e.g., improving legal rights, access to healthcare, gender-neutral bathrooms, etc.; Bockting et al., 2016; Stroumsa, 2014). Yet despite increased awareness, transgender people remain subject to significant discrimination and harassment (Lombardi, 2009; Miller & Grollman, 2015; Stotzer, 2008). A growing body of evidence indicates that a majority of transgender people have been assaulted due to their gender identify (Clements-Nolle, Marx, & Katz, 2006; Kidd & Witten, 2007; Stotzer, 2009). For example, violence against transgender people is four times as likely to cause hospitalization (Lynch, 2005) and the murder rate has been estimated at 17 times higher than victimization patterns of the general population (Lee & Kwan, 2014; 2,264 murders of transgender people recorded globally between January 2008 and September 2016; Transgender Europe, 2016). Moreover, in a number of countries being transgender is illegal and can attract heavy penalties including jail time (Hurst, Gibbon, & Nurse, 2016).

Negative attitudes toward transgender individuals are prevalent in most societies, with research indicating that a range of demographic factors, ideological values, and belief systems predict anti-transgender attitudes and behaviors (Willoughby et al., 2010). In particular, religion appears to play an important role in predicting negative attitudes toward transgender individuals (Nagoshi et al., 2008; Tee & Hegarty, 2006). The major aim of this paper is to systematically review the literature that has examined the relationship between religion and attitudes toward transgender people, and to synthesize the available evidence on this relationship.

Being transgender: Definitions, stigma, and discrimination

Transgender is an umbrella term used to define individuals whose gender (i.e., the gender that an individual psychologically identifies as) differs to the sex they were assigned at birth (American Psychological Association [APA], 2015; Davidson, 2007). For example, a transman is a person who was assigned a female sex at birth – but psychologically identifies as a man (Collazo, Austin, & Craig, 2013; see van Anders, 2015 for a more nuanced discussion of gender/sex and sex diverse labelling). Some transgender people have no desire to “transition,” and this might be because they do not experience the dysphoria sometimes associated with sex-gender incongruence. Others live with sex-gender incongruence and decide not to transition for a variety of reasons (e.g., social pressure and financial burden). Many socially, medically, and/or legally transition from the sex that they were assigned at birth to that of their gender (Collazo et al., 2013)1. Each of these varying levels of transition (including the choice not to transition) results in an individual’s trans-status being more visible (at least in the instance of the early stages of transition), which then has the potential to make these individuals the target of negative attitudes, or transprejudice (Elischberger, Glazier, Hill, & Verduzco-Baker, 2016; Erich et al., 2007; Kenagy, 2005; King, Winter, & Webster, 2009).2

Transgender people face widespread stigma and discrimination across a variety of domains, including employment, housing, healthcare, and the legal system (Grant et al., 2011; Kenagy, 2005; Lombardi, 2009). Consistent with research in the areas of sexism, racism, and sexual prejudice, research on transgender issues has revealed that a combination of demographic factors, values and beliefs can lead to transprejudice (Willoughby et al., 2010). A large body of research indicates that gender, political views, and religiosity predict transprejudice -specifically, men are more likely than women to express transprejudice (although both men and women report higher levels of transphobia if they possess traditional views of gender – e.g., belief in gender binary), as are those who endorse conservative political ideologies, and those holding conservative religious beliefs or identifying as religious (Costa & Davies, 2012; Hill & Willoughby, 2005; Nagoshi et al., 2008; Norton & Herek, 2013; Tee & Hegarty, 2006; Willoughby et al., 2010). The relationship between religion and transprejudice is the focal point of this review.

The role of religion in transprejudice

Many religions are based on teachings of peace, love, and tolerance (Johnson, Rowatt, & LaBouff, 2012) and thus, at least based on those specific teachings, these religions promote intergroup pro-sociality. However, evidence from studies of religion and social attitudes have paradoxically revealed that religion is typically a predictor of intergroup anti-sociality, or in other words religion tends to predict most forms of prejudice. When conceptualizing religion in terms of self-reported categorical religious affiliation (i.e., Christian, Muslim, Jewish, etc.), religiously affiliated individuals tend to report more negative attitudes against a variety of social outgroups than individuals who are not religiously affiliated (Allport, 1954; Shariff, Willard, Andersen, & Norenzayan, 2016). In terms of transprejudice, recent research has documented that religiously affiliated individuals report less interpersonal comfort (Kanamori, Pegors, Hulgus, & Cornelius-White, 2017), and more negative attitudes towards transgender people than non-religious individuals (Solomon & Kurtz-Costes, 2018; similar findings exist for trans-youth, see Elischberger et al. 2016). Social attitudes that are related to transprejudice reveal similar patterns: religiously affiliated individuals tend to be more prejudiced against gay men and lesbian women (Christianity: Whitehead, 2014; Muslims: Anderson & Koc, 2015), and are less supportive of gay rights (e.g., Anderson, Koc, & Falomir-Pichastor, 2018) and marriage equality (e.g., Anderson, Georgantis, & Kapelles, 2017), than non-religious individuals.

It is often argued that this link between religious affiliation and negative social attitudes is driven by perceptions that the attitude-target is violating their religion’s value system (Herek, 1987; Hunsberger & Jackson, 2005). The severity of prejudice toward social outgroups can vary depending on the religion and doctrine a person follows (Goplen & Plant, 2015). For example, research indicates that Jewish people have higher acceptance of gay men and lesbian women (Lottes & Kuriloff, 1992; Wills & Crawford, 1999), and transgender people (Cragun & Sumerau, 2015) than people identifying with other religions. In addition, most Abrahamic religions (e.g., Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) contain dogmas in which their respective deity create mankind with individuals who are perfectly entrenched in the gender binary (e.g., Christianity’s Adam and Eve), and thus religions might be instilling cisgender normativity into individuals who ascribe to their doctrines.

Religious affiliation is often used in social attitudes research because of the simplicity of this of quantification of religion. However, researchers have established that the simple categorical quantification of religious affiliation (i.e., Christian, Muslim, Jewish, etc.), might not be the most meaningful operationalization, and instead have used a continuous quantification of religiosity (i.e., the degree to which people are involved in their religion or integrate religion into their daily lives) in their research. Religiosity has been conceptualized in many ways. Some researchers have measured religious behaviors such as church attendance or frequency of praying. Others have preferred to use individual difference style measures of religiosity, including intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientations (i.e., personal vs. instrumental uses of religion, respectively), religious fundamentalism (i.e., an authoritarian set of beliefs that identify one set of religious teachings as the fundamental truth), beliefs in deity, or an amalgamation of these and other forms of religiosity (i.e., general religiosity; for a review, see Anderson, 2015). Indeed, there is evidence that religiosity can quantify religion in a way that is differently meaningful to religious affiliation (Allport, 1954; Anderson & Koc, 2015; Whitely, 2009) - particularly in the specific case of exploring religious-based prejudice.

Regardless of their religious affiliation, people who report higher levels of religiosity have been found to report more negative attitudes toward people perceived to violate religious worldviews (Whitley, 2009; Whitley & Lee, 2000). As such, individuals who are higher in religiosity may express more prejudiced attitudes toward transgender people due to increased belief in, and adherence to, specific doctrinal ordinances against gender variant behavior (Finlay & Walther, 2003; Whitley, 2009). As such, people who highly value their religious beliefs may be intolerant of gender nonconforming behavior and are more likely to feel validated in expressing transprejudice (Norton & Herek, 2013; Willoughby et al., 2010). In addition, a growing body of recent evidence has linked various forms of religiosity to transprejudice including church attendance (Fisher et al., 2017), literal interpretations of the bible (Cragun & Sumerau, 2015), and religious fundamentalism (Nagoshi, Cloud, Lindley, Nagoshi, & Lothamer, 2018). Religious fundamentalism appears to have the most consistent relationship with measures of prejudice (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992; Hunsberger & Jackson, 2005), including transprejudice (e.g., Nagoshi et al., 2008).

In summary, transgender people are becoming more publicly visible and so it is important to understand the antecedents and consequences of attitudes towards this socially vulnerable group. The broader relationship between religion and social attitudes is complex and tenuous – however, the literature suggests that religion might be related to negative attitudes toward this specific group for a variety of reasons. The aim of this paper is to identify and synthesis the available data exploring the religion-transprejudice relationship, and to systematically consider this evidence in light of various quantifications of religion used in this literature.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted and reported based on the Cochrane methodology (Higgins & Green, 2011). The methods and results are presented in accordance with the relevant sections of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2015). The protocol detailed below was developed prior to study commencement to guide the systematic search and data extraction.

Eligibility criteria

In order to be eligible for inclusion in the systematic review, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) include a measure of transprejudice—that is, a measure of attitudes toward transgender people or peoples; (2) include a measure of religion (i.e., categorical self-classification) or religiosity (e.g., religious affiliation, religious fundamentalism, frequency of religious attendance, etc.); (3) present statistical quantitative evidence for the religion-transprejudice relationship; (4) be published in peer-reviewed academic journal, and; (5) be available in English.

Information sources and search strategy

Articles were identified by searching the following five databases: Web of Science, PsycINFO, PsycEXTRA, Proquest Psychology Collection and EBSCO Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, using search terms designed to target three key concepts: (1) transgender (transgender* OR transsexual* OR "male to female" OR "female to male" OR "FtM" OR "MtF), (2) attitudes (attitud* OR belie* OR opinion* OR perception* OR perceive* OR judg* OR prejudic* OR stigma* OR discriminat* OR stereotype*), and (3) religion (religio* OR spiritual* OR faith* OR Christian* OR Islam* OR Muslim* OR Buddhis* OR Hindu* OR Catholic* OR Protestant* OR Judaism or Jew* OR Sikh* OR Mormon* OR Fundamentalis*). Limits of “English language” were applied, and no restrictions were placed on year of publication.

Study selection and data collection process

The searches were completed in April 2018, after which all records identified by the search strategy were downloaded from the five databases and merged into a single EndNote library. After both automated and manual removal of duplicates, records were screened by two independent researchers for eligibility. Screening was first conducted by examining titles and abstracts of all records (discrepancies were all moved through to the full-text screening phase); records which passed this stage were downloaded and full text articles were examined for relevance in accordance with inclusion criteria detailed above.

Information was extracted from all relevant records, and the extracted data included the year of the study, sample size, population characteristics (age, gender, religious affiliation, etc.), measures, and main findings for each study.

Quality assessment of individual studies

We used the AXIS appraisal tool to assess the methodological quality and reliability of the studies included in this review study quality (Downes, Brennan, Williams, & Dean, 2016). Each study was evaluated on 20 criteria (e.g., clarity of study aims and methodological rigour) as either yes (classified as a 1) or no/unsure (classified as 0), and thus each study is assigned a score out of 20. It is worth noting that the interpretation of these scores is subjective. The outcomes of this quality assessment are summarized in the extraction table and presented in full in the supplementary material.

Results

Study selection

The search yielded a total of 1,120 unique records. After abstract screening, 78 articles (6.98%) were deemed eligible for full-text review. Twenty-six studies within 25 articles met inclusion criteria. An additional three studies (one published and two unpublished were identified through a call for unpublished research, resulting in a total of 29 studies within 28 articles. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

Study characteristics

The 29 studies (within 28 articles) included in this systematic review contained data regarding religious affiliation and 5 categories of religious beliefs and behaviors (i.e., religiosity, biblical literalism, religious service attendance, religious fundamentalism, and religious education). The majority of studies presented the data provided by populations from the United States (k = 22). Most studies presented data from samples of university students or university faculty members (k = 18), while a lesser number presented data from community samples (k = 9). One study presented data provided by mental health nurses (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2016), and one by religious leaders (Mbote, Sandfort, Waweru, & Zapfel, 2018). All studies involved both male and female participants, except for a single study which used only male participants (Watjen & Mitchell, 2013). The results of the data extracted from these articles have been synthesized below; study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Systematic Review.

| First author, year | Country | N | Gender of sample | Age (years) | Population | Religious affiliation | Transphobia measure | Religiosity measure | Major findings | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acker, 2017 | USA | 600 | 22% male, 78% female | M = 22.00, SD = 5.85 | University students majoring in social work, nursing, occupational therapy, or psychology. | Not reported. | 9-item Transphobia Scale (Nagoshi et al., 2008). | Two-item religiosity scale (adapted from Gottfried & Polikoff, 2012): attendance at religious services in the past year, and importance religion. 85% of the sample reported moderate to high levels of religiosity. | Religiosity: Transphobia was positively correlated with religiosity (r = .23, p < .01). In MRA, religiosity was a significant predictor of transphobia (R2 = .03, p < .006). | 18 |

| Adams et al., 2016 | USA | 339 | 57.2% male, 42.8% female | Males: M = 19.34, SD = 1.22 Females: M = 18.81, SD = .94 | University students enrolled in introductory psychology courses. | 35% Catholic; 32%, Protestant or “other Christian”; 4%, Jewish; 3%, Mormon; 11%, “other”; 17%, atheist or agnostic. | 9-item Transphobia Scale (Nagoshi et al., 2008). | Twenty-item Religious Fundamentalism (RF) Scale (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). | Religiosity (fundamentalism): Transphobia was positively correlated with RF for both women (r = .20, p < .05) and men (r = .15, p < .05). In a pathway analysis, RF and RWA (indicative of a general adherence to social conventions) were significantly correlated with all indices of discomfort with violations of gender and sexual heteronormativity and with sexual prejudice and transphobia for both men and women. | 18 |

| Ali, 2016 | Canada | 74 | 56.8 % male, 41.9 % female, 1.3% unspecified | Not reported. | Psychiatrists (faculty members) and psychiatry residents at university). | Not reported. | 32-item Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | Assessed by asking “How much guidance does religion provide in your day-to-day living?” (“None at all,” “Some,” “Quite a bit,” “A great deal”). | Religiosity (religious guidance): Transphobia scores descriptively increased as reported levels of religious guidance increased (none: M = 55.3, SD = 14.6; some: M = 59.4, SD = 14.9; quite a bit: M = 62.7, SD = 24.3; a great deal: M = 68.0, SD = 17.7). However, the sample sizes were underpowered from a statistical perspective and, as such, the reliability of these between-group findings remains to be confirmed. | 15 |

| Cragun & Sumerau, 2015 | USA | 1,612 | 30.3% male, 69.7% female | M = 18.67, SD = 1.21 | University students | 27.4% “none” or non-religious, 33.4% Catholic, 30.1% Protestant, 3.4% Jewish and 5.7% other | Feeling thermometer (range: 0–100): positive values indicating relatively warmer feelings toward transgender people. | Participants self-identified their religious affiliation, then rated their religiosity on a 10-point scale. Participants were also asked their view of the Bible (response options included: “The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word”; “The Bible is the inspired word of God but not everything in it should be taken literally, word for word”; “The Bible is an ancient book of fables, legends, history, and moral precepts recorded by men”; “The Bible is not part of my religious tradition” and other. | Religiosity: Religiosity was correlated with negative attitudes toward transgender people at the bivariate level (r = −.156, p < .001), and predicted these attitudes in MRA after controlling for sex, race and sexual orientation (ß = −2.085, p < .001). Bible interpretation: Biblical literalists reported more negative attitudes toward transgender people than students who viewed the Bible as inspired or as myth (ps < .001), and students who viewed the Bible as inspired had more negative attitudes toward transgender people than did those who viewed the Bible as inspired (p < .05). Religious affiliation: Christians and those of other religions reported more negative attitudes toward transgender individuals than Jewish participants (ps < .05) and non-religious participants (ps < .01). In MRAs, identifying as Jewish was predictive of positive attitudes towards transgender people (ß = 10.95, p < .03), while identifying as Catholic (ß = 7.71, p < .01), Protestant (ß = 7.63, p < .05), or as “another” religion (ß = 15.87, p < .01) was predictive of negative attitudes. | 18 |

| de Jong, 2015 | USA | 113 | Not reported | M = 21.46, SD = 3.49 | Faculty members teaching primarily in undergraduate social work programs. | 73% no affiliation, 7% Evangelical Christian, 10% Mainline Protestant, 9% Roman Catholic, 1% “other”. | 20-item Attitudes Toward Transgendered Individuals Scale (Walch, Ngamake, Francisco, Stitt, & Shingler, 2012). | Participants were asked whether their institution had a religious affiliation or was secular. | Religious affiliation (institution level): Faculty members from secular institutions (M = 94.31, SD = 6.19) had more positive attitudes towards transgender people than faculty members from religiously affiliated institutions (M = 89.75, SD = 10.90; t(33) = 2.10, p = .044). | 19 |

| Elischberger et al., 2018 | USA and India | USA: 218; India: 217 | USA: 45.8% male, 50.5% female, 3.7% unspecified; India: 59.4% male, 37.8% female, 2.8% unspecified | USA: M = 34.04, SD = 10.11; India: M = 32.63, SD = 9.79 | Community | Not reported | 7-item scale measuring disapproval of gender atypicality (self-developed) and the 32-item Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | 2-item religiously motivated disapproval of gender nonconformity scale (self-developed). | Religion-based disapproval: Religious disapproval of gender nonconformity was predictive of disapproving attitudes towards transgender people for both U.S. participants (ß = .44, p < .001) and Indian participants (ß = .36, p < .001) when controlling for demographic variables. | 17 |

| Elischberger et al., 2016 | USA | 281 | 45.6% male, 54.1% female, 0.3% unspecified | M = 32.96, SD = 11.70 | Community | 38% not religious, 18% agnostic, 20% Protestant, 11% Catholic, 2% Jewish, 1% Muslim, < 1 % Hindu, < 1 % Buddhist, 7 % other religion. | 8-item scale measuring disapproval of transgender youth (self-developed). | Participants indicated which religious group they belonged (Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, or “other”) or whether they considered themselves not religious or agnostic. | Religious affiliation: Religiously affiliated participants were less favorable (M = 4.22, SD = 2.88) towards transgender youth than non-religious participants (M = 2.18, SD = 1.74; p < .001). There were considerable differences between religions (e.g., Jewish > Muslim), but small sample sizes precluded exploring this. MRAs found that religious affiliation was a significant predictor of negative attitudes towards transgender youth for males (ß = 0.20, p < .01) and females (ß = 0.13, p < .05), after controlling for other demographic variables. | 18 |

| Fisher et al., 2017 | Italy | 310 | 29.7% cisgender men, 31.0% cisgender women, 20.3% transwomen, 19.0% transmen | M = 33.60, SD = 10.35. | Gender dysphoric individuals, health care providers, and community. | 59.4 % agnostics/atheists, 37.1 % Christians (99% Catholics and 1% orthodox), 2.6 % Buddhists, 0.6 % Hindus, and 0.3 % Jews. | 20-item Attitude Toward Transgendered Individuals Scale (Walch et al., 2012). | Italian version of the 12-item RF Scale (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). Religious belief was measured with a single item (I do [not] have a religious belief). Religious services attendance was measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale (I do not attend religious services; I attend only for the main festivities; I attend about once a month, I attend about once a week). Religious education was measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale (not at all; a little; enough; a lot). | Religiosity (fundamentalism): Positive attitudes toward transgender people were negatively correlated with RF (r = −0.41, p < .001). For the gender dysphoric population, internalized negative attitudes towards transgender people was negatively correlated with RF (r = −0.43, p < .001). Religiosity (service attendance): Positive attitudes towards transgender people were negatively associated with a higher attendance at religious services (r = −.32, p < .001). Religious education: No significant associations were found between attitudes and religious education. | 19 |

| Garelick et al., 2017 | USA | 287 | 38.7% male, 61.3% female | M = 19.5, SD not reported | University students | Not reported | 9-item Transphobia Scale (Nagoshi et al., 2008). | 12-item RF Scale (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). | Religiosity (fundamentalism): Transphobia was significantly and positively correlated with RF for women (r = .35, p < .001), but not for men (r = .14, p > .05). RF predicted transphobia in MRAs (ß =.17, p < .05). | 15 |

| Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015 | Greece | 238 | 39.9% male, 60.1% female | M = 22.0, S = 4.5 | University students | Most participants (n = 229) were either Christian or Orthodox Christian. The remainder (n = 9) did not respond to this item. | 32-item Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | 2-item religiosity scale (self-developed): items related to self-identification as religious and frequency of attendance at religious services. Participants reported their religion (if any) with an open-ended measure. | Religiosity: Transphobia was positively correlated with self-identification as religious (r = .25, p < .01.) and frequency of attendance at religious services (r = .30, p < .01.) In MRAs, neither self-identification as strongly religious, or frequency of attendance at religious services, predicted attitudes towards transgender individuals. | 17 |

| Haupert, 2018 (unpublished manuscript) | USA | 442 | 36% male, 63% female, 0.4% genderfluid, 0.2% non-binary, 0.2% do not know 0.2% choose not to answer | M = 19.6, SD = 1.94 | University students | Not reported | 9-item Transphobia Scale (Nagoshi et al., 2008). 32-item Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | Self-report if religious (and if so, self-reported religious affiliation). | Religiosity: Transphobia (measured by both scales) was positively correlated with self-identification as religious (rs = .19 & .26, respectively). Transphobia (measured by the Transphobia Scale) was higher for religious participants (M = 2.82) than non-religious participants (M = 2.40; t(400.93) = −3.78, p < .001). Transphobia (measured by the Genderism and Transphobia Scale) was higher in religious participants (M = 3.701) than non-religious participants (M = 3.161; t(429.93) = −5.4528, p < .001). | N/A |

| Kanamori et al., 2017 | USA | 483 | 44.3% male, 55.7% female | Not reported | Community | 52.4% none, 47.6% Evangelical Christian | The 29-item Transgender Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (Kanamori et al., 2017), comprises 3 factors: interpersonal comfort; sex/gender beliefs (dichotomy vs continuum); and human value (transgender persons’ intrinsic human value). | Self-report of religious affiliation (and then only participants who identified as Evangelical Christian or non-religious were included). | Religious affiliation: A gender by religion ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for religion for all three attitude - Evangelical Christians scored lower than did non-religious people on all three factors: interpersonal comfort, F(1, 479) = 99.71, p <.001, d =.91; sex/gender beliefs, F(1, 479) = 164.38, p <.001, d = 1.17; human value, F(1, 479) = 21.21, p <.001, d =.42. No gender differences existed (ps > .115). | 20 |

| Lewis et al., 2017 | USA | 1,020 | Not reported. | Not reported. | National representative sample. | Not reported. | Feeling thermometer (range: 0–100): positive values indicating relatively warmer feelings toward transgender people. | Participants self-reported belonging to a denomination of Christianity (if any) or as being non-religious. Religiosity was measured by frequency of religious attendance on a 6-point scale from “never” to “more than once a week”. | Religiosity and affiliation: In MRAs, after controlling for demographic variables, religious attendance (ß = −1.878, p < .01) and any Christian affiliation (ß = −7.916, p < .01) were significant predictors of negative feelings toward transgender people. Non-affiliation did not predict attitudes. | 16 |

| Mao et al., 2018 | USA | 319 | 29.78% male, 70.22% | Not reported. | Self-identified cisgender heterosexual students | 1% Buddist, 29% Catholic, 1.9% Muslim, 0.6% Hindu, 6.4% Jewish, 22.9% Protestant, 10.2% another religion, 28% no religion. | 9-item Transphobia Scale (Nagoshi et al., 2008). 32-item Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | Religious affiliation was self-reported. 20-item RF scale (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). | Religiosity (fundamentalism): Transphobia (measured by both the Transphobia Scale and the Genderism and Transphobia Scale) was positively correlated with RF (rs = .407 & .475 respectively). Religious affiliation: Different religious groups reported varying levels of transphobia (F(4, 247) = 421.6, p < .001). Protestants > other religions > Catholics > no religion had higher levels of transphobia (all ps < .001). | 16 |

| Mbote et al., 2018 | Kenya | 212 | 85.8% male, 11.8% female; 2.4% did not report their gender. | Not reported. | Religious leaders from registered churches and mosques. | 59.0% Protestant, 22.1% Muslim, and 18.9% Catholic. | Three-items (self-developed) assessing beliefs and attitudes towards gender nonconformity. | Self-report. | Religious Affiliation: No difference between the three religious groups on overall attitudes of transgender people (p > .05). Muslims > Catholics > Protestants felt that it was morally wrong for a man to present himself as a woman χ2(2) = 18.47, p < .05, and for a woman to present herself as a man χ 2(2) = 22.52, p < .01). These opinions were notably strong. | 19 |

| Nagoshi et al., 2018 | USA | 294 | 36.4% male, 63.6% female | Female: M = 19.9, SD = 3.9 Male: M = 21.0, SD = 3.9 | University students | Not reported | 9-item Transphobia scale (Nagoshi et al.2008). | 20-item RF scale (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). | Religiosity (fundamentalism): RF was positively correlated with transphobia towards male-to-female targets for both men (r = .30, p < .05) and women (r = .37, p < .001), and female-to-male targets for both men (r = .33, p < .05) and women (r = .51, p < .001). | 14 |

| Nagoshi et al., 2008 | USA | 310 | 50.6% male, 49.4% female | Female: M = 19.45, SD = 3.28 Male: M = 19.47, SD = 1.76. | University students | 35% Catholic, 32% Protestant or “other Christian”, 5% Jewish, 3% Mormon, 12% “other”, and 14% atheist or agnostic. | 9-item Transphobia Scale (Nagoshi et al., 2008); items adapted from the Flexibility of Gender Aptitude Scale (Bornstein, 1998). | 20-item RF Scale (Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992). | Religiosity (fundamentalism): Transphobia was positively correlated with RF for women (r = .54, p < .001), and men (r = .28, p < .001) at the bivariate level. After controlling for homophobia, transphobia was still positively correlated with RF for women (r = .34, p < .001), but not for men (r =-.01, p > .05). | 14 |

| Norton & Herek, 2013 | USA | 2,281 | 44% male, 56% female | M = 45.87, SD not reported. | Community (heterosexual adults). | Not reported. | Feeling thermometer (range: 0–100): positive values indicating relatively warmer feelings toward transgender people. | Religiosity item, asking how much guidance religion provides in participants day-to day living (“None at all,” “Some,” “Quite a bit,” “A great deal”). | Religiosity: Positive attitudes towards transgender people were negatively correlated with religiosity only for women (r = −.30, p <.001) and not for men (r = −.02, p >.5). In MRAs, religiosity predicted women’s transgender positive attitudes (9% unique variance) but not those of men (< 1% unique variance). | 20 |

| Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2016 | Australia | 96 | 28% male, 72% female | M = 48.31, SD = 11.22 | Mental health nurses | Not reported. | 20-item Attitudes Towards Transgender Individuals Scale (Walch et al., 2012), and the 20-item Counselor Attitude Toward Transgender Scale (Rehbein, 2012). | Participants were asked their degree of religiosity (not at all, somewhat, quite, very). | Religiosity: Positive attitudes towards transgender people were negatively correlated with religiosity (r = −.330, p < .05). | 17 |

| Scandurra et al., 2017 | Italy | 438 | 30.8% male, 69.2% female | M = 32.21, SD = 5.51 | University students (graduates studying teaching) | 72.6% current religious faith (Catholic), 27.4% no current religious faith. | 25-item Transphobia/Genderism Scale of the Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005) translated into Italian. | Participants were asked if they practiced a religious faith at the moment of the study and if they had a religious education (yes/no). | Religiosity (current practice): practicing religious participants (M = 2.56, SD = .88) reported higher transphobia scores than non-practicing participants (M = 2.02, SD = 0.79; t = 5.69, p < .001, d = .64). Religious education: Participants who received a religious education (M = 2.44, SD = .90) reported higher transphobia scores than those who did not (M = 2.08, SD = 0.77; t = 2.22, p < .05, d = .43). After controlling for demographic variables in MRAs, practicing religion was a predictor of transphobic attitudes (ß = −.12, p <.05), but religious education was not (ß = −.01, p >.05). | 19 |

| Skarsgard et al., 2014 (unpublished Conference Poster) | USA | 318 | 38.68% male, 61.32% female | M = 38.0; SD = 15.10 | 61.64% university students, 38.36% community sample | Not reported | 30-item Prejudice Towards Transsexual Women Scale (Winter et al. 2009). | Religiosity was rated on a likert scale. | Religiosity: Transphobia was correlated with self-reported religiosity for the student sample (r = −.33, p < .001), but not the community sample (r = .14, p > .05). | 14 |

| Solomon & Kurtz-Costes,2018 (Study 1) | USA | 274 | 41.2% male, 58.8% female | M = 36.0; SD = 11.60 | Community sample | 48.5% Christians, 35.8% atheists, 15.7% Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, and other non-Abrahamic religions. | 20-item Attitudes Toward Transgendered Individuals Scale (Walch et al., 2012). | Religious affiliation was self-reported. Most participants identified as Atheist (n = 98) or Christian (n = 133), resulting in comparisons between these categories Religiosity was assessed by asking participants how important religion was to them on a 1 to 10 scale. | Religious affiliation: Christians (M = 3.50, SD = 0.99) reported more negative attitudes towards transgender people than Atheists (M = 4.31, SD = 0.70; F(1, 229) = 47.51, p < .001, d = .94). Religiosity: For Christians, positive attitudes towards transgender individuals were negatively correlated with religiosity (r = −.24, p = .006). | 20 |

| Solomon & Kurtz-Costes, 2018 (Study 2) | USA | 450 | 46.7% male, 53.3% female | M = 39.50; SD = 12.70 | Community sample | 52.4% Christians, 23.8% atheists, 23.8% other religions. | 20-item Attitudes Toward Transgendered Individuals Scale (Walch et al., 2012). | Religious affiliation was self-reported. | Religious affiliation: Christian participants (M = 3.41, SD = 1.01) reported more negative attitudes than Atheist participants (M = 4.13, SD = 0.71; F(1, 338) = 44.34, p < .001, d = .82). | 20 |

| Swank et al., 2013 | USA | 2,078 | 37.1% male, 62.9% female | M = 23.74, SD = 7.69 | University students | 34.8% no religious affiliation, 55.3% follow Christian traditions, 9.9% follow non-Christian traditions. | One item from the Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005): “If I found out that a friend was changing their sex, I could no longer be their friend.” | Participants were asked “How often do you attend religious services?” (0= never, 1 = very rarely, 2 = once a month, 3 = every other week, 4 = once a week, 5 = more than once a week). | Religiosity (attendance): Transphobia was correlated with attendance at religious services for straight (r(1168) = .187, p < 0.01), but not LGB students (r(366) = .063, p >.05). | 16 |

| Watjen & Mitchell, 2013 | USA | 114 | All male | M = 21.2, SD = 0.41 | University students | 79% Christian; the rest identified as atheist, agnostic, or non-religious. | 15 items derived (or modified) from the Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | Single item requesting religious affiliation. | Religious affiliation: Christians reported higher transphobia scores (M = 49.00, SD = 1.90) than non-religious participants (M = 33.70, SD = 3.70; z (Mann–Whitney U) = 3.39, p < .001). | 15 |

| Willoughby et al., 2010 | Philippines | 207 | 24.6% male 67.6% female, 7.7% self-identified as either both or neither male and female. | M = 18.50, SD not reported | Christian university students | 75% Roman Catholic, 21% other Christian denominations | 32-item Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | To measure religiosity, participants were asked (a) whether they were religious, and (b) how often they attended church or worship services in the past month. | Religiosity: Transphobia was correlated with self-reported religiosity (r = .25, p < .001) and worship frequency (r = .33, p < .001). | 18 |

| Worthen, 2014 | USA | 991 | Not reported. | M = 21.58, SD = 3.36 | University students | Not reported | 32-item Genderism and Transphobia Scale (Hill & Willoughby, 2005). | Respondents were asked (a) if they religious, and (b) how often they attended church. | Religiosity: In MRAs, religiousness (ß = –1.76, p < .001) and church attendance (ß = –1.10, p < .001) were predictors of transphobia when controlling for various demographic factors. | 19 |

| Worthen, 2017a | USA, Italy and Spain | 1311 | Not reported | Oklahoma: M = 21.82, SD = 3.51 Texas: M = 20.24 SD = 1.90 Italy: M = 23.45, SD = 2.34 Spain: M = 23.53, SD = 2.82 | University students | Not reported | Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scale (Worthen, 2012). | Respondents were asked how often they attend church on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (every week). Respondents were also asked if they believed that “The bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word” were coded as (1) for Biblical Literalism while others were coded as (0). | Religiosity: Church attendance was a significant predictor of negative attitudes in Oklahoma (ß = −.04, p < .001), but not in Texas (p > .05). Biblical literalism was a significant predictor of negative attitudes toward transgender people, when controlling for demographic factors, both in Oklahoma (ß = −.15, p < .001) and Texas (ß = −.20, p < .05). For Italians and Spaniards, neither church attendance nor biblical literalism were significant predictors of attitudes toward transgender people (when controlling for demographic factors; ps > .05). | 20 |

| Worthen, 2017b | USA | 1,940 | 42% male, 58% female | Not reported | University students in the Bible Belt in the southern USA. | Not reported | Attitudes Toward LGBT People Scales (Worthen, 2012). | Religiosity scale included questions about general religiousness, church attendance, biblical literalism, and attitudes toward biblical passages about “sin” and “homosexuality” (Worthen, 2012). | Religiosity: In MRAs, after controlling for demographic factors, religiosity was a predictor of negative attitudes toward transgender men for both heterosexual (ß = −.29, p < .05) and LGB participants (ß = −.31, p < .05), and towards transgender women for both heterosexual (ß = −0.37, p < .05) and LGB people (ß = −0.28, p < .05). | 19 |

Notes: RF = religious fundamentalism; RWA = right-wing authoritarianism; MRA = multiple regression analyses.

Religious affiliation

Religious identification

All six studies examining self-identification found that identifying as “religious” was associated with higher levels of transphobia than identifying as not religious (i.e., atheist, agnostic, or no religion; Elischberger et al., 2016; Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015; Haupert, 2018; Scandurra, Picariello, Valerio, & Amodeo, 2017; Solomon & Kurtz-Costes, 2018 [Studies 1 & 2]). Three of these studies (Elischberger et al., 2016; Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015; Scandurra et al., 2017), along with an additional study (Worthen, 2014), examined religious identification as a predictor of transprejudice. Three studies found that self-identification as religious predicted transprejudice (Elischberger et al., 2016; Scandurra et al., 2017; Worthen, 2014), while the forth study found that religious self-identification was only correlated to attitudes at the bivariate level but was not a significant predictor in multiple regression analyses (Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015).

Specific religious affiliations

Christian participants were the most frequently sampled religious affiliation in this literature. Six studies explored transprejudice as a function of a Christian affiliation—specifically, by comparing participants who identified as Christian and those who identified as having another religion or no religion (Cragun & Sumerau, 2015; Kanamori et al., 2017; Mao, Haupert, & Smith, 2018; Mbote et al., 2018; Scandurra et al., 2017; Watjen & Mitchell, 2013). These studies all found that Christian participants reported more transprejudice than did non-Christian/nonreligious and Jewish participants (Kanamori et al., 2017; Scandurra et al., 2017; Watjen & Mitchell, 2013), however, there were no differences in attitudes between Christian participants and participants of other religions (e.g. Buddhist, Islamic, Hindu, etc; Cragun & Sumerau, 2015). Another study found that Protestant participants reported more transprejudice than other Christians and participants of other religions; however, all religious groups reported higher levels than participants with no religion (Mao et al., 2018). One African study found that more Muslim leaders than Christian leaders felt that it was morally wrong for a man to present himself in public as a woman and for a woman to present herself in public as a man (Mbote et al., 2018). One of these five studies (Cragun & Sumerau, 2015), as well as an additional study (Lewis et al., 2017) examined Christian affiliation as a predictor of transprejudice. One study found that identifying as Christian predicted transprejudice (Cragun & Sumerau, 2015), while the other found differences between Christian denominations—specifically, that identifying as an Evangelical or Protestant Christian did not predict transprejudice; however, being any other Christian religion (e.g., Catholic) did predict increases in transprejudice (Lewis et al., 2017).

Two studies explored differences in transprejudice as a function of a Jewish religious affiliation (Cragun & Sumerau, 2015; Elischberger et al., 2016). Both studies found that Jewish participants had less transprejudice than participants of other religions. In addition, Cragun and Sumerau found that Jewish participants’ attitudes toward transgender people did not differ from participants who reported having no religion, and that being Jewish predicted decrease in transprejudice in multivariate analyses.

Religiosity

General religiosity

All nine studies that evaluated the role of religiosity (i.e., nonspecific religiosity, typically measured with single items—see Table 1 for specifics) found that individuals with higher levels of religiosity reported more transprejudice than individuals endorsing lower levels of religiosity (Acker, 2017; Ali, Fleisher, & Erickson, 2016; Cragun & Sumerau, 2015; Elischberger, Glazier, Hill, & Verduzco-Baker, 2018; Norton & Herek, 2013; Skarsgard, Ganesan, Broussard, Goldsmith, & Harton, 2014; Solomon & Kurtz-Costes, 2018 [Study 1]; Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2016; Willoughby et al., 2010).3 However, it is worth noting that Skarsgard et al. (2014) found that this relationship was only significant in a student sample and not a community sample. Four of these studies (Acker, 2017; Cragun & Sumerau, 2015; Elischberger et al., 2018; Norton & Herek, 2013) and an additional study (Worthen, 2017) examined religiosity as a predictor of transprejudice. All five studies found that religiosity was a significant predictor of negative attitudes toward transgender individuals (Acker, 2017; Cragun & Sumerau, 2015; Elischberger et al., 2018; Norton & Herek, 2013; Worthen, 2017). However, it is worth noting that Norton and Herek (2013) found that this result was qualified by the participants gender, and that this relationship existed only for women and not for men.

Religious fundamentalism

All six studies assessing religious fundamentalism (beliefs that one set of religious teachings are the unchanging and fundamental truth) found that religious fundamentalism was a bivariate correlate of transprejudice (Adams, Nagoshi, Filip-Crawford, Terrell, & Nagoshi, 2016; Fisher et al., 2017; Garelick, Filip-Crawford, Varley, Nagoshi, Nagoshi, & Evans, 2017; Mao et al., 2018; Nagoshi et al., 2008; Nagoshi et al., 2018). Two of these studies also examined religious fundamentalism as a predictor of transprejudice. Nagoshi et al. (2008) found that religious fundamentalism was a significant predictor of transprejudice when simultaneously entered in a block with authoritarianism, and Garelick et al. (2017) found that religious fundamentalism was a significant predictor of transprejudice, but only for women participants (this qualification also existed at the bivariate level).

Biblical literalism

Only one study explored biblical literalism, but this study found a significant correlation between literal interpretation of the Bible and transprejudice (Cragun & Sumerau, 2015). In addition, Worthen et al. (2017) also assessed biblical literalism as a predictor of transprejudice. Both studies found that biblical literalism predicted transprejudice in U.S. populations; however, this effect did not hold for samples from Italy or Spain.

Frequency of religious attendance

All four studies that examined the relationship between religious attendance and transprejudice found that more frequent attendance at religious services was significantly correlated with increase in transprejudice for heterosexual participants (Fisher et al., 2017: Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015; Swank et al., 2013; Willoughby et al., 2010). Swank et al. (2013) found that frequency of religious service attendance was significantly correlated with transprejudice, but this effect was qualified by the sexual orientation of their participants—the effect existed for the heterosexual portion of their sample but found this effect did not exist for lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) participants. One of these studies (Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015) and an additional three studies (Lewis et al., 2017; Worthen, 2014; Worthen, Lingiardi, & Caristo, 2017) examined frequency of religious attendance as a predictor of transprejudice, with three of the studies finding that religious attendance was a significant predictor of transprejudice (Lewis et al., 2017; Worthen, 2014; Worthen et al., 2017). However, the latter study found that this was true only for an Oklahoman population, and that the effect did not hold for Texan, Italian, or Spanish populations. One study that examined almost exclusively Greek Orthodox Christians found that the frequency of attendance at religious services did not predict transprejudice (Grigoropoulos & Kordoutis, 2015).

Religious education

Three studies investigated the relationship between religious education (or used samples from religious affiliated vs nonaffiliated educational institutions) and transprejudice, with mixed results. One study found a significant difference in transprejudice between participants who received a religious education and those who did not receive a religious education (Scandurra et al., 2017), with participants who received a religious education reporting higher levels of transprejudice. However, another study found no relationship (Fisher et al., 2017). One study found that faculty members from religious affiliated institutions had more transprejudice than faculty members from secular institutions (de Jong, 2015). One study examined religious education was not a predictor of transprejudice among Catholic participants (Scandurra et al., 2017).

Factors influencing the religion-attitudes relationship

Gender

Five studies examined the moderating effect of gender on the religion-transprejudice relationship (Adams et al., 2016; Garelick et al., 2017; Nagoshi et al., 2008; Nagoshi et al., 2018; Norton & Herek, 2013). Three of these studies found that religious fundamentalism was correlated with transprejudice for both men and women (Adams et al., 2016; Nagoshi et al., 2008; Nagoshi et al., 2018); however, Nagoshi et al. (2008) found this correlation was significant only for women (and not for men) when statistically controlling for homophobia. Two studies found that measures of religiosity were correlated with transprejudice for women (but not men) participants (Garelick et al., 2017; Norton & Herek, 2013).

Two of these studies (Garelick et al., 2017; Norton & Herek, 2013) and an additional single study (Elischberger et al., 2016) examined if gender qualified religious factors as predictors of transprejudice. Two studies found that measures of religiosity predicted transprejudice for women but not men (Garelick et al., 2017; Norton & Herek, 2013), and one study found that religious affiliation was a significant predictor of transprejudice people for both men and women (Elischberger et al., 2016).

Sexual orientation

Two studies examined the moderating effect of sexual orientation on the religion-transprejudice relationship. Swank et al. (2013) found that transprejudice was correlated with attendance at religious services for heterosexual students, but not LGB students. In contrast, Worthen (2017) found that religiosity was a predictor of transprejudice for both heterosexual and LGB participants.

Target’s gender/sex

Two studies differentiated attitudes toward male-to-female (MTF) transprejudice from female-to-male (FTM) transprejudice (Nagoshi et al., 2018; Worthen, 2017). No differences were found in religious attitudes toward transmen and transwomen. One study found that religious fundamentalism was related to both MTF and FTM transprejudice (Nagoshi et al., 2018), and the other found that religiosity predicted both MTF and FTM transprejudice (Worthen, 2017).

Discussion

Negative attitudes toward transgender people (i.e., transprejudice) are prevalent in most societies and can lead to discrimination and harassment (Lombardi, 2009; Willoughby et al., 2010). Religion—both categorical religious affiliation and differences in religiosity—appears to play an important role in trans-prejudicial attitudes (Nagoshi et al., 2008; Tee & Hegarty, 2006). This paper systematically reviewed and synthesized the evidence from studies that have examined the religion-transprejudice relationship and in doing so presented substantial evidence that religion is related to increase in transprejudice (regardless of the operationalization of religion). Some mixed evidence for moderators of this relationship were identified.

Summary of evidence

Across studies, consistent evidence was found indicating that religious identification (i.e., self-classification as a religious person) is associated with more negative attitudes toward transgender people and higher levels of transphobia. These findings are comparable to studies that have found that self-identification as religious is linked to prejudice against other social outgroups (Allport, 1954; Shariff et al., 2016; Whitley, 2009). The majority of studies also found that specific religious affiliations tend to be associated with higher levels of transprejudice. For example, Christian participants reported the most negative attitudes towards transgender people, and a single study reported that Muslim participants harbor similar levels of transprejudice as Christians participants; however, evidence for this finding is limited to a single study that explicitly examined Muslim attitudes. A caveat to the religious affiliation- transprejudice findings pertains to Judaism. Specifically, across a limited number of studies (k = 2), evidence was presented that Jewish participants had the most positive attitudes toward transgender people compared to participants of other religions (although equitable with nonreligious participants). This finding is comparable to research suggesting that Jewish people tend to have more tolerant attitudes toward social outgroups than Christians (Lottes & Kuriloff, 1992; Wills & Crawford, 1999).

Consistent evidence was found linking forms of religiosity (general religiosity, religious fundamentalism, biblical literalism, and attendance at religious services) with transprejudice. This may be explained by research indicating that individuals who are highly religious have increased belief in, and adherence to, specific doctrinal ordinances against gender variant behavior (Finlay & Walther, 2003; Whitley, 2009). As such, people who highly value their religious beliefs are more likely to have negative attitudes toward people who they perceive as demonstrating gender nonconforming behavior, and thus are more likely to feel validated in expressing transphobia (Norton & Herek, 2013; Willoughby et al., 2010). There was a mixed evidence regarding the association between religious education and transprejudice, with no definite trend found suggesting that religious education is associated with negative attitudes towards transgender people. It is also worth noting that one of these studies only measured the religious affiliation of the participants’ educational institution, and not the religious identification and/or religiosity of individual participants, limiting the interpretability of the findings.

Some evidence was provided indicating the relationship between religion and attitudes toward transgender people may be moderated by individual characteristics of the attitude holder—including their geographical location, gender, and sexual orientation. At the bivariate level, religiosity was found to significantly correlate with transprejudice across all populations, regardless of geographical location. Although aspects of religiosity, such as biblical literalism and frequency of religious attendance, were predictive of transprejudice for the majority of U.S populations, they were not significant predictors of transprejudice for other populations including Italian, Spanish, and Greek populations. It has been suggested that negative attitudes toward transgender people in these countries may be mostly related to political beliefs, rather than religious beliefs (Worthen, 2017). Related to this, researchers have begun to explore the roles of political and social factors and how they interact with religion to result in other prejudices. For example, Doebler (2015) found that religion was more strongly related to prejudice toward gay people in Western Europe in comparison to Eastern Europe. Future research could explore the interaction of such political and social factors with religion to produce transprejudice.

Mixed evidence was found regarding the effect of gender on the religion-transprejudice relationship - approximately half of the studies (k = 3) suggested that there were no gender differences; however, the remaining studies (k = 2) presented evidence in which gender differences existed. In these studies, religion was associated with increase in transprejudice for women but not men. This is an area where further research would be beneficial. Mixed evidence was found in the limited number of studies (k = 2) that examined the effect of sexual orientation on religious attitudes toward transgender people, with only one study providing evidence that sexual orientation influences the relationship between religious measures and transphobia. Taken together, our understandings of the religion-transprejudice relationship are fairly limited, and the moderating and mediating factors in this relationship warrant further exploration.

Limitations

The generalizability of these findings are limited by the populations studied. The majority of studies (n = 18) used convenience samples comprised exclusively of university students or faculty members. This can present a problem as university students typically represent a more liberal-leaning part of society due to the well-documented relationship between education and positive attitudes toward LGBT individuals (Norton & Herek, 2013). Additionally, most studies used U.S. samples, which were primarily Christian in religious affiliation. However, only a limited number of studies explicitly examined the individual denominations that make up the larger affiliation of Christianity (e.g., Evangelicalism, Protestantism, Catholicism, etc). As such, this systematic review did not account for differences between individual Christian denominations. Furthermore, although other religious affiliations, such as Buddhism and Hinduism, may also be associated with transphobia, no studies were identified that met inclusion criteria and assessed these affiliations explicitly. More cross-national and cross-cultural research is needed to examine the roles social and cultural norms play in shaping the relationship between religiosity and attitudes toward transgender people.

The literature on religion has reported that religiosity is made up of a number of different constructs (Anderson, 2015). Yet, many of the measures of religiosity used were based on simplistic indices involving a single dimension (e.g., self-rating general “religiousness” or frequency of religious attendance). Measuring religiosity in this way may limit the conclusions a study can make. In particular, it may not accurately measure religiosity across religious affiliations. For example, frequency of religious attendance may vary in some religious populations (i.e., some religions mandate more frequent attendance than others; some people attend for ritualistic purposes or out of obligation [e.g., with parents/spouse] rather than for personal reasons). Although some studies included multiple measures of religiosity (e.g., self-rated religiosity and religious fundamentalism), few studies directly compared the ways in which different measures of religiosity are associated with attitudes toward transgender people or examined possible interactions between these religious measures.

Finally, we would like to acknowledge that our search strategy targeted the transprejudice literature, and that the search terms used in this strategy might have overlooked other related constructs of interest such as attitudes toward gender and sexual diversity.

Conclusions

This is the first systematic review of the literature that explores the relationship between religion and transprejudice. The narrative synthesis of the results indicates that people who identify as being religious, or as belonging to a religion (with the exception of Judaism), on average reported higher levels of transprejudice than nonreligious individuals. In addition, there was consistent evidence that religiosity (in particular religious fundamentalism, biblical literalism, and church attendance) was also related to increase in transprejudice. There was a mixed evidence for moderators of these relationships—these relationships were sometimes stronger and more consistent for participants who were straight, female, and from the United States.

Understanding the factors that are antecedents and predictors of transprejudice, and specifically religiously-motivated transprejudice, are necessary into order to inform interventions and strategies to combat stigma and discrimination against this vulnerable people. The continued exploration of these factors is necessary. We hope that if religion-specific transprejudice decreases, there will be a related decrease in more general transprejudice and continued improvements in policy and laws that affect transgender individuals.

Funding Statement

This research was supported in part by an Early Career Research Grant from the Freilich Foundation, and also by a student grant from the Faculty of Health Science at Australian Catholic University.

Notes

It is also worth noting that some transgender people identify outside the gender binary of ‘male’ and ‘female’, identifying as neither, both, or somewhere on a spectrum between the two, and may move fluidly between identities over time (Dean et al., 2000; Whittle, Turner, Al-Alami, Rundall, Thom, 2007).

Transprejudice is synonymous with Transphobia which refers to negative, prejudicial attitudes toward individuals whose gender identity does not align with their biological sex (Hill & Willoughby, 2005), although in line arguments that the suffix ‘phobia’ has clinical connotations (Anderson & Holland, 2015; Herek & McLemore, 2013) we prefer the former term.

It is worth noting that Ali and colleagues (2016) found a trend for higher levels of transprejudice as levels of religious guidance increased, however the sample sizes in this study was underpowered from a statistical perspective and as such, the reliability of these between-group findings needs ratifying.

Ethical approval

Formal consent is not required for this paper (i.e., no data collected).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- *indicates references identified for inclusion in this review by the search strategy.*Acker G. M. (2017). Transphobia among students majoring in the helping professions. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(14), 2011–2029. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1293404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Adams K. A., Nagoshi C. T., Filip-Crawford G., Terrell H. K., & Nagoshi J. L (2016). Components of gender-nonconformity prejudice. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(3–4), 185–198. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1200509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Ali N., Fleisher W., & Erickson J (2016). Psychiatrists’ and psychiatry residents’ attitudes toward transgender people. Academic Psychiatry, 40(2), 268–273. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0308-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allport G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. New York, NY: Addison Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer B., & Hunsberger B (1992). Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 2(2), 113–133. doi: 10.1207/s15327582ijpr0202_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. R. (2015). The social psychology of religion: Using scientific methodologies to understand religion In Mohan B. (Ed.), Constructions of social psychology. Baton Rouge, CA: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. R., Koc Y., & Falomir-Pichastor J. M (2018). The English Version of the attitudes toward homosexuality scale. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 77(3), 1–10. advanced online edition. doi: 10.1024/1421-0185/a000210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. R., Georgantis C., & Kapelles T (2017). Predicting support for marriage equality in Australia. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69(4), 256–262. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. R., & Holland E (2015). The legacy of medicalising ‘homosexuality’: A discussion on the historical effects of non-heterosexual diagnostic classifications. Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain, and Culture, 12, 4–15. doi: 10.7790/sa.v11i1.405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. R., & Koc Y (2015). Exploring patterns of explicit and implicit anti-gay attitudes in Muslims and Atheists. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(6), 687–701. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting W., Coleman E., Deutsch M. B., Guillamon A., Meyer I., Meyer W., … Ettner R (2016). Adult development and quality of life of transgender and gender nonconforming people. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 23(2), 188. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K., Marx R., & Katz M (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(3), 53–69. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n03_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collazo A., Austin A., & Craig S. L (2013). Facilitating transition among transgender clients: Components of effective clinical practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, 41(3), 228–237. doi: 10.1007/s10615-013-0436-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P. A., & Davies M (2012). Portuguese adolescents' attitudes toward sexual minorities: Transphobia, homophobia, and gender role beliefs. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(10), 1424–1442. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.724944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Cragun R. T., & Sumerau J. E (2015). The last bastion of sexual and gender prejudice? Sexualities, race, gender, religiosity, and spirituality in the examination of prejudice toward sexual and gender minorities. The Journal of Sex Research, 52(7), 821–834. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.925534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M. (2007). Seeking refuge under the umbrella: Inclusion, exclusion, and organizing within the category transgender. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 4(4), 60. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2007.4.4.60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean L., Meyer I. H., Robinson K., Sell R. L., Sember R., Silenzio V. M., … Dunn P (2000). Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 4(3), 102–151. doi: 10.1023/A:1009573800168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *de Jong D. (2015). Transgender issues and BSW programs: Exploring faculty perceptions, practices, and attitudes. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 20(1), 199–218. doi: 10.18084/1084-7219.20.1.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Elischberger H. B., Glazier J. J., Hill E. D., & Verduzco-Baker L (2016). “Boys Don’t Cry”—or Do They? Adult Attitudes Toward and Beliefs About Transgender Youth. Sex Roles, 75(5-6), 197–214. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0609-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Elischberger H. B., Glazier J. J., Hill E. D., & Verduzco-Baker L (2018). Attitudes toward and beliefs about transgender youth: A cross-cultural comparison between the United States and India. Sex Roles, 78(1–2), 142–160. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0778-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erich S. A., Boutté-Queen N., Donnelly S., & Tittsworth J (2007). Social work education: Implications for working with the transgender community. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 12(2), 42–52. doi: 10.18084/1084-7219.12.2.42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay B., & Walther C (2003). The relation of religious affiliation, service attendance, and other factors to homophobic attitudes among university students. Review of Religious Research, 44(4), 370–393. doi: 10.2307/3512216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Fisher A. D., Castellini G., Ristori J., Casale H., Giovanardi G., Carone N., … Maggi M (2017). Who has the worst attitudes toward sexual minorities? Comparison of transphobia and homophobia levels in gender dysphoric individuals, the general population and health care providers. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 40(3), 263–273. doi: 10.1007/s40618-016-0552-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Garelick A. S., Filip-Crawford G., Varley A. H., Nagoshi C. T., Nagoshi J. L., & Evans R (2017). Beyond the binary: Exploring the role of ambiguity in biphobia and transphobia. Journal of Bisexuality, 17(2), 172–189. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2017.1319890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goplen J., & Plant E. A (2015). A religious worldview: Protecting one’s meaning system through religious prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(11), 1474–1487. doi: 10.1177/0146167215599761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. M., Mottet L., Tanis J. E., Harrison J., Herman J., & Keisling M (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; Retrieved from: http://transequality.org/PDFs/NTDS_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- *Grigoropoulos I., & Kordoutis P (2015). Social factors affecting antitransgender sentiment in a sample of Greek undergraduate students. International Journal of Sexual Health, 27(3), 276–285. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2014.974792 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Haupert M. L. (2018). Considerations in the Development and Implementation of Transgender-Inclusive Gender Questions (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Herek M. G. (1987). Can functions be measured? A new perspective on the functional approach to attitudes. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50(4), 285–303. doi: 10.2307/2786814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M., & McLemore K. A (2013). Sexual Prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 309–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., & Green S (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Vol. 4). Wiltshire, Great Britain: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hill D. B., & Willoughby B. L (2005). The development and validation of the genderism and transphobia scale. Sex Roles, 53(7-8), 531–544. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-7140-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger B., & Jackson L. M (2005). Religion, meaning, and prejudice. Journal of Social Issues, 61(4), 807–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00433.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst C. E., Gibbon H. M. F., & Nurse A. M (2016). Social inequality: Forms, causes, and consequences. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. K., Rowatt W. C., & LaBouff J. P (2012). Religiosity and prejudice revisited: In-group favoritism, out-group derogation, or both? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 4(2), 154–168. doi: 10.1037/a0025107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Kanamori Y., Pegors T. K., Hulgus J. F., & Cornelius-White J. H (2017). A comparison between self-identified evangelical Christians’ and nonreligious persons’ attitudes toward transgender persons. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(1), 75–86. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy G. P. (2005). Transgender health: Findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health & Social Work, 30(1), 19–26. doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd J. D., & Witten T. M (2007). Transgender and trans sexual identities: The next strange fruit-hate crimes, violence and genocide against the global trans-communities. Journal of Hate Studies, 6(1), 31–63. doi: 10.1.1.577.9419 [Google Scholar]

- King M. E., Winter S., & Webster B (2009). Contact reduces transprejudice: A study on attitudes towards transgenderism and transgender civil rights in Hong Kong. International Journal of Sexual Health, 21(1), 17–34. doi: 10.1080/19317610802434609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., & Kwan P (2014). The trans panic defense: Masculinity, heteronormativity, and the murder of transgender women. Hastings Law Journal, 66, 77–133. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2430390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Lewis D. C., Flores A. R., Haider-Markel D. P., Miller P. R., Tadlock B. L., & Taylor J. K (2017). Degrees of acceptance: Variation in public attitudes toward segments of the LGBT community. Political Research Quarterly, 70(4), 861–875. doi: 10.1177/1065912917717352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi E. (2009). Varieties of transgender/transsexual lives and their relationship with transphobia. Journal of Homosexuality, 56(8), 977–992. doi: 10.1080/00918360903275393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottes I. L., & Kuriloff P. J (1992). The effects of gender, race, religion, and political orientation on the sex role attitudes of college freshman. Adolescence, 27(107), 675–688. PMID: 1414577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch A. M. (2005). Hate crime as a tool of the gender border patrol: The importance of gender as a protected category Paper presented at the When Women Gain, So Does the World, IWPR’s Eighth International Women’s Policy Research Conference Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- *Mao J. M., Haupert M. L., & Smith E. R (2018). How Gender Identity and Transgender Status Affect Perceptions of Attractiveness [Supplemental material] Social Psychological and Personality Science. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1948550618783716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Mbote D. K., Sandfort T. G., Waweru E., & Zapfel A (2018). Kenyan religious leaders’ views on same-sex sexuality and gender nonconformity: Religious freedom versus constitutional rights. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 630–641. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1255702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. R., & Grollman E. A (2015). The social costs of gender nonconformity for transgender adults: Implications for discrimination and health. Sociological Forum, 30(3), 809–831. doi: 10.1111/socf.12193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., (2015). …. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–9. Stewart L. A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Nagoshi J. L., Adams K. A., Terrell H. K., Hill E. D., Brzuzy S., & Nagoshi C. T (2008). Gender differences in correlates of homophobia and transphobia. Sex Roles, 59(7–8), 521–531. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9458-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Nagoshi C. T., Cloud J. R., Lindley L. M., Nagoshi J. L., & Lothamer L. J (2018). A test of the three-component model of gender-based prejudices: Homophobia and transphobia are affected by raters’ and targets’ assigned sex at birth. Sex Roles, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11199-018-0919-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Norton A. T., & Herek G. M (2013). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward transgender people: Findings from a national probability sample of US adults. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 738–753. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-0110-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Riggs D. W., & Bartholomaeus C (2016). Australian mental health nurses and transgender clients: Attitudes and knowledge. Journal of Research in Nursing, 21(3), 212–222. doi: 10.1177/1744987115624483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Scandurra C., Picariello S., Valerio P., & Amodeo A. L (2017). Sexism, homophobia and transphobia in a sample of Italian pre-service teachers: The role of socio-demographic features. Journal of Education for Teaching, 43(2), 245–261. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2017.1286794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shariff A. F., Willard A. K., Andersen T., & Norenzayan A (2016). Religious priming: A meta-analysis with. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(1), 27–48. doi: 10.1177/1088868314568811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Skarsgard N., Ganesan A., Broussard K., Goldsmith P., & Harton H (2014). Prejudice Towards Transsexual Women. Unpublished data.

- *Solomon H. E., & Kurtz-Costes B (2018). Media’s Influence on Perceptions of Trans Women. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(1), 34–47. doi: 10.1007/s13178-017-0280-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stotzer R. L. (2008). Gender identity and hate crimes: Violence against transgender people in Los Angeles County. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 5(1), 43. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2008.5.1.43 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stotzer R. L. (2009). Violence against transgender people: A review of United States data. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(3), 170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroumsa D. (2014). The state of transgender health care: policy, law, and medical frameworks. American Journal of Public Health, 104(3), e31–e38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Swank E., Woodford M. R., & Lim C (2013). Antecedents of pro-LGBT advocacy among sexual minority and heterosexual college students. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10(4), 317–332. doi: 10.1007/s13178-013-0136-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tee N., & Hegarty P (2006). Predicting opposition to the civil rights of trans persons in the United Kingdom. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 16(1), 70–80. doi: 10.1002/casp.851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Transgender Europe (2016). Transgender day of visibility: Trans murder monitoring update. Retrieved from http://tgeu.org/transgender-day-of-visibility-2016-trans-murder-monitoring-update/.

- Van Anders S. M. (2015). Beyond sexual orientation: Integrating gender/sex and diverse sexualities via sexual configurations theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(5), 1177–1213. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0490-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Watjen J., & Mitchell R. W (2013). College men’s concerns about sharing dormitory space with a male-to-female transsexual. Sexuality & Culture, 17(1), 132–166. doi: 10.1007/s12119-012-9143-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead A. L. (2014). Politics, religion, attribution theory, and attitudes toward same‐sex unions. Social Science Quarterly, 95(3), 701–718. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley B. E. (2009). Religiosity and attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: A meta-analysis. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19(1), 21–38. doi: 10.1080/10508610802471104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley B. E., & Lee S. E (2000). The relationship of authoritarianism and related constructs to attitudes toward homosexuality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(1), 144–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02309.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]