Abstract

Rationale:

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a heterogeneous, usually familial disorder of heart muscle. The hypertrophic form of cardiomyopathy is frequently genetic, or as part of several neuromuscular disorders. In neonates, especially prematurity, HCM could also be secondary to corticosteroid treatment.

Patient concerns:

We reported here a 34 weeks gestational age preterm infant presented with profound cardiomegaly after multiple doses of hydrocortisone used to treat blood pressure instability associated with septic shock and persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN).

Diagnosis:

Patient presented auscultation of a grade III/IV harsh systolic ejection murmur from day 14, which was absent before. Profound cardiomegaly was indicated at chest film at day 30. Echocardiography showed severe thickening of the IVS (13.8 mm, z score = 8.29) and mild thickening of the posterior left ventricular wall (LVPW, 6 mm).

Interventions:

Propranolol and captopril were started along with supportive care. The patient was also admitted to NICU for further treatment with 24-hour Holter electrocardiographic monitoring.

Outcomes:

A reversible course was observed without left ventricular outflow tract obstruction nor arrhythmias within 4 weeks.

Lessons:

The risk/benefit ratio must be carefully considered when corticosteroids are used in prematurity. Monitors such as echocardiography and electrocardiograph should be conducted in order to guide cardiovascular management. Systematic surveys of the incidence of cardiac complications in a larger population of preterm infant treated with corticosteroid are needed in the future.

Keywords: hydrocortisone, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, neonatal intensive care, septic shock

1. Introduction

Hydrocortisone (HC) is widely used in infants with increased inotropic support in septic shock and severe pulmonary disease.[1] The most recent Surviving Sepsis Guidelines use the term “catecholamine resistant shock” and recommend consideration of corticosteroids at this point.[2] However, question still needs to be resolved regarding the appropriate target population. In certain subgroups, increased risks of mortality, suppression of adaptive immunity, and secondary infections from corticosteroid administration have been suggested in several retrospective controlled trials (RCTs) in pediatric critical care.[3,4] Herein, we present a preterm infant with transient myocardial hypertrophy after multiple dose of hydrocortisone used to treat septic shock.

2. Case report

A 2260-g male infant was born at 34 weeks of gestation via caesarean section due to central placenta previa with hemorrhage to a 36-year-old multipara whose pregnancy was complicated with hyperthyroidism. Full dose of dexamethasone was given to the mother prior to delivery. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. The patient was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit and intubated because of respiratory distress within the first 30 minutes of life. Pulmonary hemorrhage presented shortly after high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV). Inhalational nitric oxide was applied because of PPHN from day 3 to day 7. He received 2 doses of surfactant, umbilical venous catheter (UVC), and umbilical artery catheter (UAC) were conducted thereafter to monitor central artery pressure.

During the first 3 days, HC 2 mg/kg q8 h was given intravenously because of circulatory failure indicated by hypotension responsive to substantial fluid administration and intensive inotropic support. When the epinephrine and dopamine requirement were reduced, HC was weaned gradually over a period of 5 days. The mean arterial pressure (MAP) raised up to 92 mmHg from day 7 and remained at 85 ± 7.4 mmHg until discharge. The patient also accepted blood exchange and albumin (2 g as a total dose) because of hyperbilirubinemia (greatest indirect bilirubin 434 μmol/L).

Acute hypokalemia arised on day 14, serum potassium decreased to as low as 2.1 mmol/L. Potassium replacement was given as 0.3 mmol/kg/h intravenously, as well as oral repletion 4 mmol/kg/d in divided doses. Serum potassium was between 2.8 and 3.3 mmol/L in the following 2 weeks and remain normal thereafter.

Fetal echocardiography had been performed at 24 weeks of gestation, which showed a structurally normal heart without ventricular hypertrophy. The first pediatric cardiology consultation was requested at day 1. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed 3 mm right-to-left shunting of blood across the foramen ovale and a large patent ductal arteriosus (PDA) with bidirectional shunting. The second TTE, performed at day 3, indicated mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) 35 mmHg, LVEF 67% and similar atrial left-right shunt and patent ductal shunt when PPHN was persistent. At day 11, PPHN was ameliorated clinically, and the mean PAP had decreased to 23 mmHg suggested by 3rd TTE. The thickness of the interventricular septum (IVS) was normal at all these abovementioned TTE.

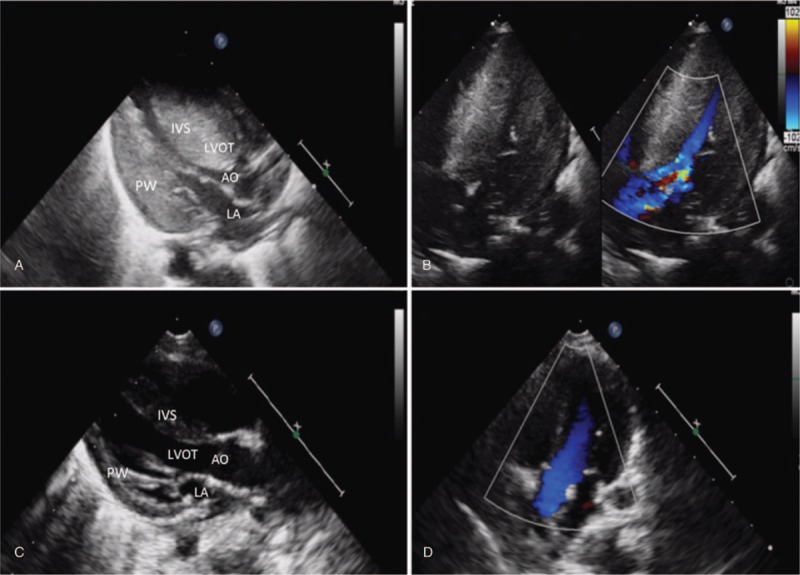

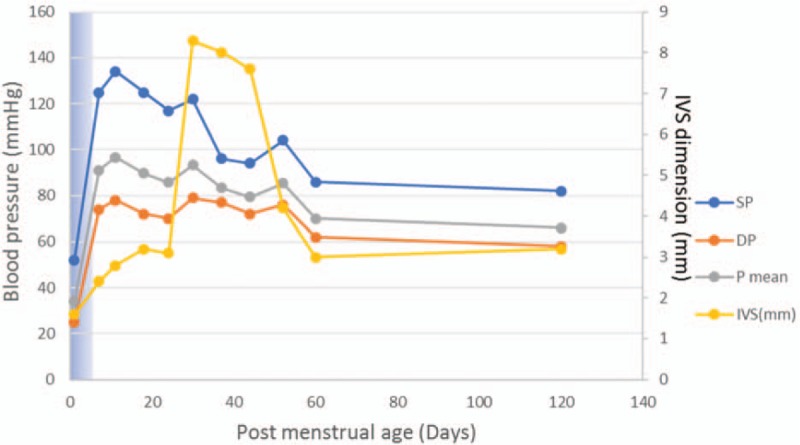

Echocardiography was repeated at day 30 because of profound cardiomegaly indicated at chest film and auscultation of a grade III/IV harsh systolic ejection murmur. This TTE showed severe thickening of the IVS (13.8 mm, z score = 8.29) and mild thickening of the posterior left ventricular wall (LVPW, 6 mm). Thicken of the ventricle affect the septum more than the ventricular free wall (IVS/LVPW 2.3, Fig. 1A and B). For children, IVS z-score of ≥2 related to body surface area is compatible with the diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Outflow tract obstruction was not observed, with a peak velocity of 0.85 m per second. Aortic coarctation (COA) was ruled out. Prenatal history was negative for maternal risk factors as well as the familial history regarding genetic and metabolic diseases, sudden death, or syncope history. Maternal oral glucose tolerance test and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were normal (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Cardiomyopathy and hypertension track against the steroid dose. Hydrocortisone (2 mg/kg) was administrated in the first 5 days, duration shown as blue shadow in the chart.

Figure 2.

Postnatal TTE at 30 days (A, B) and 60 days (C, D) of life. A, Parasternal long-axis view showing the severely narrowed left ventricular cavity as well as the hypertrophic interventricular septum. IVS/LVPW: 2.3; B, Parasternal 4 chamber view with color-flow Doppler showing no restriction of flow through the left ventricular outflow tract. EF 51%; C, Significant remission of left ventricular hypertrophy. D, Improvement of septal configuration. AO = aorta; IVS = interventricular septum; LA = left atrium; LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract; PW = posterior wall.

Propranolol (0.2 mg q8 h) and captopril (0.02 mg q8 h) were administrated. 24-hour Holter electrocardiographic monitoring demonstrated no arrhythmia. Serial transesophageal echocardiograms were performed the next few weeks. Thickness of the IVS decreased to 3 mm progressively on day 60 (Fig. 1C and D). Except increased MAP, the baby remained completely asymptomatic. Supplemental oxygen was discontinued on the 30th day. Tandem mass spectroscopy analysis was normal. Exome sequencing targeting over 4000 genes was negative. The patient was discharged from hospital at 45th of life. At post-discharge follow-up, MAP was 65 mmHg 60th postnatal day, cardiologic evaluation was normal.

3. Discussion

This report provides evidence that HC treatment is associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) in prematurity. It is a well-established notion that HCM is the most common of the genetic cardiovascular diseases, caused by a multitude of mutations in gene encoding proteins of the cardiac sarcomere. Eleven mutated genes, most commonly encoding beta-myosin heavy chain, are presently associated with HCM, accounting for about 50% patients. Other causes may include non-sarcomeric protein mutations cause storage diseases that are phenocopies of sarcomeric HCM and require molecule diagnosis, namely, Fabry disease, Pompe disease, Friedreich ataxia, mitochondrial disorders, and medications such as tacrolimus. Several epidemiologic studies have reported a prevalence of the HCM phenotype as 2‰, however, it is notable that most affected individuals remain asymptomatic and unidentified. Notably this condition is No. 1 cause of sudden death in the young, including competitive athletes. On the other hand, myocardium of prematurity is susceptible. In this population, dietary deficiency, or enzymatic defects that affect energy utilization may impair myocardial function. Occasionally, low calcium or magnesium, hypophosphatemia, and severe hypoglycemia cause reversible cardiac dilation and heart failure. Infants of diabetic mother can also have hypertrophic hearts with or without obstruction that resemble HCM with asymmetric septal hypertrophy, notably, this prevalence is higher in prematurity.[5,6,7] In this case, the fetal echocardiography was normal, the patient did not have any clinical and laboratory evidence of genetic disorder nor persistent metabolic disturbance, which indicates prenatal and maternal causes could not be responsible for the myocardial hypertrophy after birth. Moreover, the spontaneous reversal nature makes familial and metabolic causes less likely.

In the immediate postnatal period, abnormal regulation of peripheral vascular resistance with or without myocardial dysfunction is a frequent cause of hypotension underlying shock, especially in preterm infants. Shock secondary to sepsis is also related with release of proinflammatory cascades that lead to vasodilation. HC infusion at stress dose (50 mg/m2/d) is powerful drug in extremely premature infants with hypotension refractory to volume expansion and vasopressors via a number of different mechanisms.[1,4] HC suppresses the inflammatory response, induces the expression of cardiovascular adrenergic receptors that are downregulated by prolonged use of sympathomimetic agents and also inhibits catecholamine metabolism. After HC administration, there is a rapid increase in intracellular calcium availability, resulting in enhanced response to adrenergic agents as evident as 2 hours. Short-term side effects of HC are hypertension, hyperglycemia, GI hemorrhage, and perforation, moreover, cerebral palsy is the most important long-term sequela.[8,9]

The mechanism of HC-related myocardial thickening is less clear. HC may act through insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) or its receptors on cardiac myocytes to induce left ventricular hypertrophy, as a result, synthesis of various intracellular cardiac protein increased, contributing to hypertrophy of myocytes.[10,11] Although the ventricle size often remains normal, the thickening may block blood flow out of the ventricle, result in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Echocardiography is the primary tool for diagnosis of HCM. HCM can raise pressure in the ventricles and the blood vessels of the lungs. Changes also occur to the cells in the damaged heart muscle, which may disrupt the heart's electrical signals and lead to arrhythmias. Very vigorous physical activity which triggers arrhythmias may cause sudden cardiac arrest in some case with HCM. The goal of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy treatment is to relieve symptoms and prevent sudden cardiac death in people at high risk. Medications such as beta blockers and calcium channel blockers are used to reduce myocardia oxygen demand and to slow the heart rate, therefore improve the compliance. Other treatments include septal myectomy or ablation, and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. HC-induced HCM is usually a benign condition and was resolved a few weeks after discontinuation, furthermore, none of case in the literature present hypertension related to HCM. The precise incidence is lacking, however, the frequency and severity of myocardial hypertrophy may increase with dose and duration of HC treatment, infants receiving insulin in addition to HC may present in greater level of hypertrophy.

In conclusion, we strongly recommend that the risk/benefit ratio must be carefully considered when corticosteroids are used in neonatal septic shock, especially in prematurity. Since HCM is associated with lethiferous arrythmias in some cases, adequate monitor such as echocardiography and electrocardiograph should be conducted in order to guide cardiovascular management. Novel therapeutic approaches to be applied in controlling its harmful consequences are suggested.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xiaobi Liang for productive discussions and thoughtful suggestions.

Author contributions

Data curation: Jiawen Zhang.

Investigation: Jingbo Jiang, Mengmeng Kang.

Methodology: Jingbo Jiang.

Resources: Jingbo Jiang, Mengmeng Kang.

Supervision: Jie Yang.

Writing – original draft: Jingbo jiang.

Writing – review & editing: Jingbo Jiang, Jiawen Zhang, Mengmeng Kang, Jie Yang.

Jingbo Jiang orcid: 0000-0001-7453-904X.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AO = aorta, COA = aortic coarctation, HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin, HCM = hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, HC = hydrocortisone, IVS = interventricular septum, LA = left atrium, LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract, LVPW = posterior left ventricular wall, MAP = mean arterial pressure, PAP = pulmonary artery pressure, PDA = patent ductal arteriosus, PPHN = persistent pulmonary hypertension, PW = posterior wall, TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram, UAC = umbilical artery catheter, UVC = umbilical venous catheter.

The written consent we obtained from study participants was approved by the ethics committee of Guangdong Women and Children's Hospital.

Written consent for publication of the patient's data was provided by his father.

All datasets are deposited in the patient's digital health care file. All datasets are also presented in machine readable format.

No funding was obtained for this study.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1]. Menon K, Wong HR. Corticosteroids in pediatric shock: a call to arms. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015;16:e313–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines Committee including the pediatric, surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:165–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, et al. Corticosteroids are associated with repression of adaptive immunity gene programs in pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:940–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Doyle LW, Cheong JL, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Early (< 8 days) systemic postnatal corticosteroids for prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;10:CD001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Paech C, Wolf N, Thome UH, et al. Hypertrophic intraventricular flow obstruction after very-low-dose dexamethasone (Minidex) in preterm infants: case presentation and review of the literature. J Perinatol 2014;34:244–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Goldberg JF, Mery CM, Griffiths PS, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in severe hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy associated with persistent pulmonary hypertension in an infant of a diabetic mother. Circulation 2014;130:1923–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Cloherty JP, Eichenwald EC, Stark AR. Manual of Neonatal Care. The Netherlands: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Doyle LW, Ehrenkranz RA, Halliday HL. Dexamethasone treatment in the first week of life for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants: a systematic review. Neonatology 2010;98:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Altit G, Vigny-Pau M, Barrington K, et al. Corticosteroid therapy in neonatal septic shock-do we prevent death? Am J Perinatol 2018;35:146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Bassareo PP, Abella R, Fanos V, et al. Biomarkers of corticosteroid-induced hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in preterm babies. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2010;2:1460–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Aoyama T, Matsui T, Novikov M, et al. Serum and glucocorticoid-responsive kinase-1 regulates cardiomyocyte survival and hypertrophic response. Circulation 2005;111:1652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]