Abstract

Lipid accumulation is a driving force in tumor development, as it provides tumor cells with both energy and the building blocks of phospholipids for construction of cell membranes. Aberrant homeostasis of lipid metabolism has been observed in various tumors; however, the molecular mechanism has not been fully elucidated.

Methods: Yin yang 1 (YY1) expression in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was analyzed using clinical specimens, and its roles in HCC in lipid metabolism were examined using gain- and loss-of function experiments. The mechanism of YY1 regulation on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1β (PGC-1β) and its downstream genes medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) and long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) were investigated using molecular biology and biochemical methods. The role of YY1/ PGC-1β axis in hepatocarcinogenesis was studied using xenograft experiment.

Results: This study showed that YY1 suppresses fatty acid β-oxidation, leading to increase of cellular triglyceride level and lipid accumulation in HCC cells, and subsequently induction of the tumorigenesis potential of HCC cells. Molecular mechanistic study revealed that YY1 blocks the expression of PGC-1β, an activator of fatty acid β-oxidation, by directly binding to its promoter; and thus downregulates PGC-1β/MCAD and PGC1-β/LCAD axis. Importantly, we revealed that YY1 inhibition on PGC-1β occurs irrespective of the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF1-α), enabling it to promote lipid accumulation under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Conclusion: Our study reveals the critical role of YY1/PGC-1β axis in HCC cell lipid metabolism, providing novel insight into the molecular mechanisms associated with tumor cell lipid metabolism, and a new perspective regarding the function of YY1 in tumor progression. Thus, our study provides evidences regarding the potential of YY1 as a target for lipid metabolism-based anti-tumor therapy.

Keywords: Yin Yang 1, fatty acid oxidation, lipid accumulation, hepatocellular carcinoma, PGC-1β

Introduction

Metabolic reprogramming is a characteristic of tumor cells and is closely related to malignancy 1, 2. Recent studies revealed alterations in lipid metabolism as an important hallmark of tumor metabolic reprogramming 3. Fatty acids are not only important sources of cell energy but also major sources for cell-membrane synthesis and signaling molecules 4, 5. In normal cells, the balance of cellular fatty acid content is determined by the balance of fatty acid synthesis (FAS) and degradation maintained by fatty acid oxidation (FAO) pathways 6. However, to meet the demand of their highly proliferative growth, tumor cells alter their lipid metabolism by accelerating de novo fatty acid synthesis while simultaneously suppressing fatty acid degradation, resulting in cellular lipid accumulation. Furthermore, tumor microenvironment, such as hypoxia, is also an important driving force for tumor cell lipid metabolic reprogramming 7-9. On the other hand, recent studies demonstrated that disrupted lipid homeostasis is also highly related with the most common chronic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), whose full spectrum ranges from isolated hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH could progress to cirrhosis, which in turn predisposes patients to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 10, 11.

Yin yang 1 ( YY1 ) is a GLI-Krüppel zinc finger protein with four C2H2 zinc finger domains at its carboxy terminus which could act as both positive and negative regulators of target genes depending on the contexts 12, 13. YY1 could bind and regulate its target genes both at their transcriptional 14-16 and post-translational 17-19 levels. Furthermore, recent study reveals that YY1 could also control gene expression by binding to active enhancers and promoter-proximal elements, facilitating the interaction of these DNA elements 20. YY1 plays critical roles in various biological processes, including DNA replication, cell proliferation and differentiation, and embryonic development 13, 19, 21, 22. Aberrant YY1 expression is closely related to diseases, and its overexpression is observed in various cancers including HCC 23-27. A previous study showed that YY1 suppresses C/EBP homologous protein transcription and induces the accumulation of triglyceride (TG) in adipocytes, suggesting its relationship with obesity 28. Furthermore, YY1 increases in the liver of obese mice and promotes cellular TG accumulation in adipocytes by suppressing the expression of the farnesoid X receptor gene, thereby leading to increased hepatosteatosis 29. These studies indicate that YY1 might be involved in lipid metabolic disorder diseases; however, YY1 involvement in altering tumor cell lipid metabolism has not been fully elucidated.

Here, we revealed that YY1 is critical for alteration of lipid metabolism in HCC cells by suppressing the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1β (PGC-1β), a transcriptional activator of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) and long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) 7, 30. PGC-1β enhances the expression levels of both MCAD and LCAD, which are key enzymes necessary for FAO, and thus are critical for promoting tumorigenesis 7, 31. In line with this, our findings demonstrated that YY1 overexpression suppresses fatty acid β-oxidation, leading to increased lipid accumulation in HCC cells and subsequent hepatocarcinogenesis. Interestingly, our results showed that YY1 inhibition of PGC-1β expression occurs independent of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a key regulator of hypoxic response that has been known to promote tumor cell lipid accumulation. Accordingly, YY1 could alter HCC cell lipid metabolism under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. These results provide novel insight into the molecular mechanisms associated with cell lipid metabolic reprogramming, an important hallmark and driving force of hepatocarcinogenesis.

Methods

Vectors construction

U6 promoter-based shRNA expression vectors specific for YY1, MCAD, LCAD, PGC-1β and HIF-1α were designed and constructed as described previously 32. Target sequences were as follows: shYY1-1 (5'-GCA AGA AGA GTT ACC TCA G-3'); shYY1-2 (5'-GGC AGA ATT TGC TAG AAT G-3'); shMCAD-1 (5'-GCA CCA AGC AAT ATC ATT T-3'); shMCAD-2 (5'-GGA GAA AGG AAT TAA ACA T-3'); shLCAD-1 (5'-GGT AAG AAG TAA ATA TGT A-3'); shLCAD-2 (5'-GAA AGA GCT TCC ACA GGA A-3'); shPGC-1β-1 (5'-TGA GTA TGA CAC TGT CTT T-3'); shPGC-1β-2 (5'-CAG ATA CAC TGA CTA CGA T-3'); shHIF-1α-1 (5'-GGA TGA AAG TGG ATT ACC A-3') and shHIF-1α-2 (5'-GAC ACA GCC TGG ATA TGA A-3'). shRNA expression vector containing a stretch of 7 thymines terminator sequences exactly downstream of the U6 promoter, namely shCon, was used as a control. YY1 (pcYY1), HIF-1α (pcHIF-1α), and YY2 (pcYY2) overexpression vectors were constructed as described previously 19, 24. For YY1 and PGC-1β overexpression vectors with puromycin resistance gene (pcEF9-puro-YY1 and pcEF9-puro-PGC-1β), the corresponding coding sequences were further subcloned into pcEF9-puro vector (kindly provided by Dr. Makoto Miyagishi, AIST, Japan).

For wild-type PGC-1β luciferase reporter vector (PGC-1β-Luc) and PGC-1β luciferase reporter vector without predicted YY1 binding site (PGC-1βdel-Luc), we cloned the -594 to +532 and the -594 to -226 regions of the PGC-1β promoter, respectively, into the BglII and HindIII sites of the pGL4.13 vector (Promega, Madison, WI). Human genome DNA was extracted from HepG2 cells using TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China), and used as template. Promoter regions were then amplified using Takara PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio, Dalian, China). PGC-1β luciferase reporter vector with mutated YY1 binding site (PGC-1βMut-Luc) were constructed using Site-directed mutagenesis kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

Cell lines, cell culture and transient transfection

HepG2 and MHCC-97H cell lines were purchased from the Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China), and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cell lines were verified using short-tandem repeat profiling method, and were tested periodically for mycoplasma contamination by using Mycoplasma Detection Kit-Quick Test (Biotool, Houston, TX).

For gene-silencing experiments, cells were seeded in 6-well plate and transfected with 2 μg of indicated vectors. 24 h after transfection, transfected cells were selected by using 1 μg/ml puromycin for 36 h. For gene overexpression experiments, cells were seeded in 6 well-plates, transfected with 2 μg of indicated vectors, and collected 24 h after transfection for further experiments. For double silencing and triple silencing experiments, cells were transfected with 1 μg or 0.7 μg of each indicated vectors respectively, and subjected to puromycin selection to eliminate untransfected cells. For establishing YY1-silenced and YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced MHCC-97H stable cell lines, cells were seeded in 10 cm well-plates, and transfected with 7.5 μg each of shYY1-1 and shCon vectors, or 7.5 μg each of shYY1 and shPGC-1β-1 vectors. Cells transfected with 15 μg shCon were used as control. For establishing YY1-overexpressed and YY1/PGC-1β-double overexpressed MHCC-97H stable cell lines, cells were seeded in 10 cm well-plates, and transfected with 7.5 μg of pcEF9-puro-YY1, or 7.5 μg each of pcEF9-puro-YY1 and pcEF9-puro-PGC-1β vectors. Cells transfected with 15 μg pcEF9-puro were used as control. Stable cell lines were then established by performing puromycin selection. HIF-1α-null HepG2 (HepG2HIFnull) stable cells were established using CRISPR/Cas9 method. Briefly, cells were transfected with vectors targeting HIF-1α (GeneCopoiea, Rockville, MD; HCP001130-CG09-3-10-a, target site: TTC TTT ACT TCG CCG AGA TC; HCP001130-CG09-3-10-b, target site: CCA TCA GCT ATT TGC GTG TG; HCP001130-CG09-3-10-c, target site: TGT GAG TTC GCA TCT TGA TA). Twenty-four hours later, puromycin selection (1 μg/ml) was performed for 7 days to eliminate untransfected cells. Cell line was then established from a single clone. The corresponding genome DNA was subjected to sequencing and deletion of nucleotides located in 567 to 606 region (40 bp) of HIF-1α coding sequence was confirmed. All transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Hypoxia treatment was performed as described in our previous work for 24 h or 48 h before RNA or protein extraction, respectively 19.

Clinical human HCC specimens

Human HCC specimens were obtained from patients undergoing surgery at Chongqing University Cancer Hospital (Chongqing, China). Patients did not receive chemotherapy, radiotherapy or other adjuvant therapies prior to the surgery. The specimens were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Prior patients' written informed consents were obtained. The experiments were approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Chongqing University Cancer Hospital, and conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki.

Xenograft experiment

For the in vivo tumor study, BALB/c-nu/nu mice (male, body weight: 18-22 g, 6 weeks old) were purchased from the Third Military Medical University (Chongqing, China). Animal studies were carried out in the Third Military Medical University (Chongqing, China, Permit Number SYXK-PLA-20120031), and approved by the Laboratory Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of the Third Military Medical University. All animal experiments conformed to the approved guidelines of Animal Care and Use Committee of Third Military Medical University. All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

For generating experimental subcutaneous tumor model, BALB/c-nu/nu mice were randomly divided into three groups (n = 6), and each group was injected subcutaneously with stable cell lines. Tumor size (V) was evaluated by caliper every four days with reference to the following equation: V = a x b2/2, where a and b are the major and minor axes of the tumor, respectively 19. The investigator was blinded to the group allocation and during the assessment.

RNA extraction, quantitative reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis and western blotting

Detailed methods for RNA extraction, qRT-PCR and western blotting are described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods. The sequences of the primers and the antibodies used are listed in Table S1 and Table S2, respectively.

Fatty acid β-oxidation rate

Cells were transfected with indicated shRNA expression vectors or overexpression vectors as described above. Cells or tissues were collected and mitochondrial protein was extracted using Cell Mitochondria Isolation Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Fatty acid β-oxidation rate was measured using Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Detection Kit (Genmed Scientifics, Shanghai, China). Values were normalized with the amount of mitochondrial protein.

Statistical analysis

All values were presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Quantification results were analyzed as a relative to that of controls of each experiment, which were defined as one, and then presented as an average of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by One-way ANOVA conducted using SPSS Statistics v. 17.0. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05, and P < 0.01 was considered highly significant compared to control group. For analyzing the correlation of two variables in human HCC specimens, bivariate correlation analysis (Pearson's r test) was conducted using Prism5.

Results

YY1 enhances lipid accumulation in HCC cells

Accumulation of lipid is crucial for tumor cells to meet the demand of their highly proliferative growth. Hypoxia is an important driving force for tumor cell lipid accumulation 8, 9. As shown in Figure S1A, hypoxic environment enhances the level of TG, which in turn contributes to tumor cell metabolic plasticity and promotes tumor cell growth, as well as metastasis 33, 34. To investigate the role of YY1 in regulating HCC cell lipid metabolism under hypoxic condition, we knocked down YY1 expression in the HCC cell lines HepG2 and MHCC-97H using short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), and confirmed that both shYY1 vectors efficiently knocked down YY1 mRNA expression (Figure S1B). To exclude the cross-reactivity of the anti-YY1 antibody we used with YY2, another member of YY1 family highly homologous with YY1, we examined the specificity of anti-YY1 antibody in YY2-overexpressed HepG2 cells. As shown in Figure S1C, anti-YY1 antibody could only detect the band of YY1 but not that of YY2 both in control and in YY2-overexpressed cells, confirming that the antibody we used was specific to YY1. Using this antibody, we further confirmed the efficiency of shYY1 in downregulating YY1 protein expression (Figure S1D). We next examined alterations in lipid accumulation using Nile Red and Oil Red O stainings, and found that YY1 silencing significantly suppressed lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells under hypoxic condition (Figure 1A, Figure S1E). Concomitantly, YY1 overexpression (Figure S1F) enhanced lipid accumulation (Figure 1B). Similar tendency was also observed in MHCC-97H cells (Figure 1C). Evaluation of changes in TG level also revealed that under hypoxic condition, YY1 silencing significantly suppressed TG level in both cell lines, whereas YY1 overexpression promoted it (Figure 1D-E). These results suggested that YY1 is critical for lipid accumulation in HCC cells.

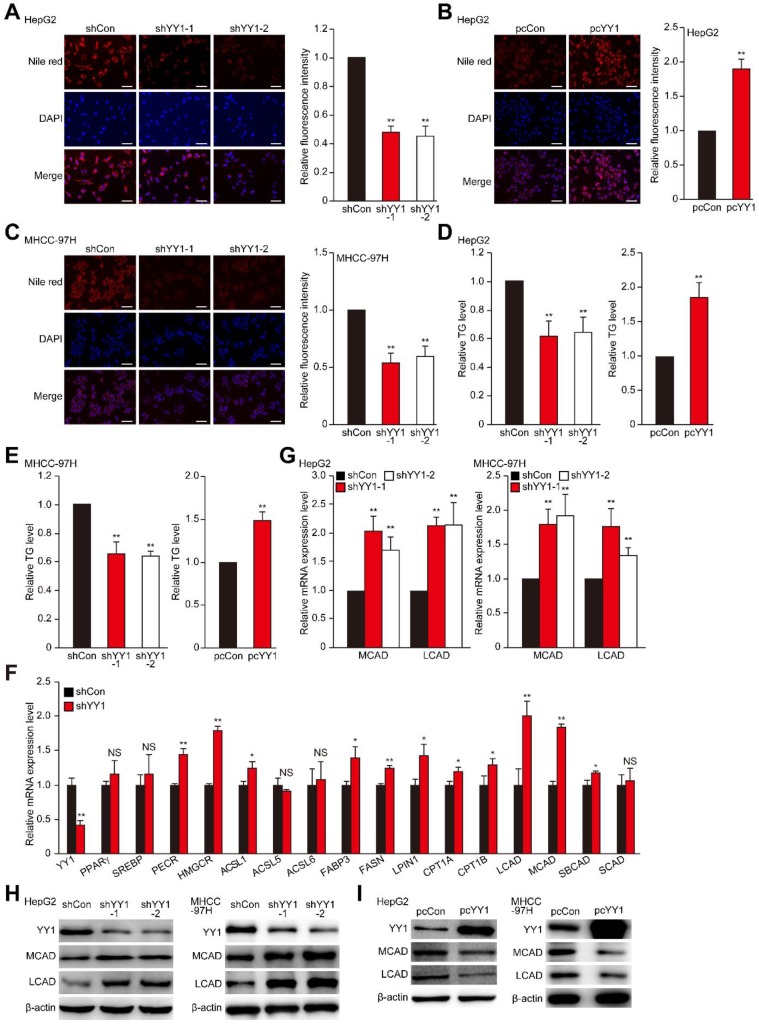

Figure 1.

YY1 induces hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cell lipid accumulation by regulating MCAD and LCAD expression. A-B. The accumulation of lipid droplets in YY1-silenced (A) and YY1-overexpressed (B) HepG2 cells, as determined using Nile Red staining. Representative images (left) and relative fluorescence intensity (right, n = 9) are shown. C. The accumulation of lipid droplets in YY1-silenced MHCC-97H cells, as examined using Nile Red staining. Representative images (left) and relative fluorescence intensity (right, n = 9) are shown. D-E. The levels of cellular triglyceride (TG) in YY1-silenced and YY1-overexpressed HepG2 (D) and MHCC-97H (E) cells (n = 3). F. mRNA expression levels of various lipid metabolic-associated factors in YY1-silenced HepG2 cells, as determined using quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR (qRT-PCR). Representative data are shown (n = 3). G-H. mRNA (G) and protein (H) expression levels of MCAD and LCAD in YY1-silenced HepG2 and MHCC-97H cells, as determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3) and western blotting, respectively. I. Protein expression levels of MCAD and LCAD in YY1-overexpressed HepG2 and MHCC-97H cells, as determined using western blotting. All experiments were performed under hypoxic condition. Cells transfected with shCon or pcCon were used as controls. β-actin was used for qRT-PCR normalization and as western blotting loading control. Scale bars: 200 μm. Quantification data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. pcCon: pcDNA3.1(+); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; NS: not significant (ANOVA).

To uncover the mechanisms underlying YY1 regulation of HCC cell lipid metabolism, we investigated the effect of YY1 silencing and overexpression on the expression of genes associated with lipid metabolism in tumors 4, 7. As shown in Figure 1F, among the genes whose expression levels were affected by YY1-silencing, the levels of medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA-reductase (HMGCR) were induced most significantly. In line with the results of YY1 silencing, YY1 overexpression significantly suppressed MCAD and LCAD expression; however, it did not significantly affect HMGCR expression (Figure S2A). Previous studies showed that MCAD and LCAD are key enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation and, therefore, are critical for fatty acid degradation 7, 31; while HMGCR is the rate limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis whose upregulation promotes lipid accumulation 35. Given that YY1-silencing suppressed lipid accumulation in HCC cells, and that it altered the expression of MCAD and LCAD more significantly, we next focus on the regulatory effect of YY1 on MCAD and LCAD. By using both shYY1 vectors, we further confirm that YY1 silencing could significantly enhance MCAD and LCAD mRNA as well as protein levels under hypoxic condition (Figure 1G-H). Accordingly, YY1 overexpression reduced the expression levels of MCAD and LCAD (Figure S2B, Figure 1I), confirming that YY1 negatively regulated MCAD and LCAD expression at the transcriptional level. Together, these results indicated that YY1 is a novel regulator of MCAD and LCAD expression.

YY1 suppresses fatty acid β-oxidation by suppressing MCAD and LCAD levels

MCAD and LCAD are key enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation. They enhanced fatty acids degradation, leading to the suppression of lipid accumulation and subsequently, tumor cells proliferation 7. Indeed, MCAD and LCAD silencing increased lipid accumulation (Figure S3A-E). We next examined whether YY1 affects fatty acid β-oxidation. We found that YY1 silencing significantly increased fatty acid β-oxidation (Figure 2A), whereas YY1 overexpression decreased it (Figure 2B). These results indicated possible YY1 involvement in HCC cell lipid metabolism and promoting lipid accumulation by suppressing fatty acid β-oxidation.

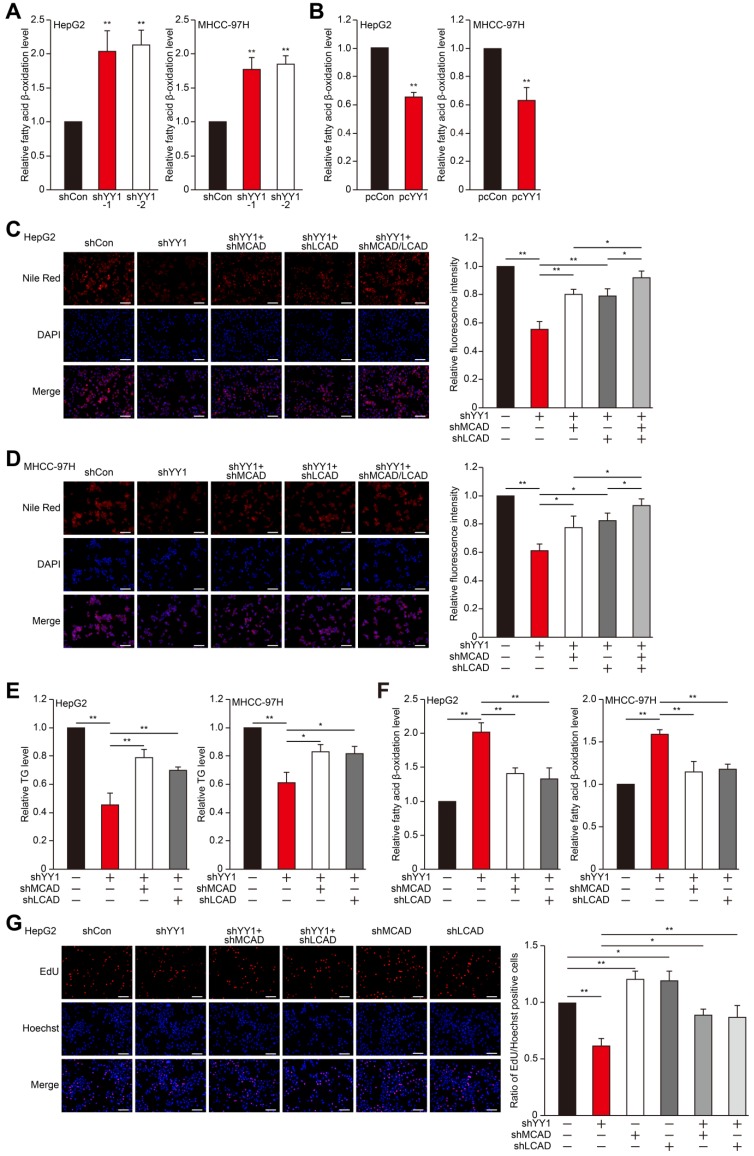

Figure 2.

YY1 upregulates fatty acids β-oxidation by negatively regulates the expression of MCAD and LCAD at their transcriptional levels. A-B. The level of fatty acid β-oxidation in YY1-silenced (A) and YY1-overexpressed (B) HepG2 and MHCC-97H cells (n = 3). C-D. The accumulation of lipid droplets in YY1/MCAD- or YY1/LCAD-double silenced HepG2 (C) and MHCC-97H (D) cells, as examined using Nile Red staining. Representative images (left) and relative fluorescence intensity (right, n = 9) are shown. E-F. The levels of cellular TG (E) and fatty acid β-oxidation (F) in YY1/MCAD- or YY1/LCAD-double silenced HepG2 (left) and MHCC-97H (right) cells (n = 3). G. Number of proliferative YY1/MCAD- or YY1/LCAD-double silenced HepG2 cells, as determined by EdU incorporation assay. Representative images (left) and ratio of the EdU positive cells to the total cell number (right) are shown (n = 9). All experiments were performed under hypoxic condition. Cells transfected with shCon or pcCon were used as controls. Scale bars: 200 μm. Quantification data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. pcCon: pcDNA3.1(+); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

To elucidate the roles of MCAD and LCAD in the YY1 regulatory pathway associated with lipid metabolism, we performed YY1/MCAD-double silencing as well as YY1/LCAD-double silencing (Figure S3F). We confirmed that YY1/MCAD-double silencing and YY1/LCAD-double silencing clearly recovered lipid accumulation suppressed by YY1 silencing alone under hypoxic condition in HepG2 and MHCC-97H cells, while knocking down three of them recovered lipid accumulation more significantly (Figure 2C-D). Furthermore, YY1/MCAD-double silencing and YY1/LCAD-double silencing also restored cellular TG level (Figure 2E). Concomitantly, MCAD and LCAD silencing together with YY1 significantly attenuated the increase in fatty acid β-oxidation induced by YY1 silencing alone (Figure 2F). Moreover, we found that double silencing of YY1 and either MCAD or LCAD resulted in pronounced recovery of total cell number (Figure S3G) and the number of proliferative cells (Figure 2G). These results indicated that YY1 suppressed fatty acid β-oxidation by downregulating MCAD and LCAD levels, resulting in increased lipid accumulation under hypoxic condition.

YY1 negatively regulates PGC-1β expression

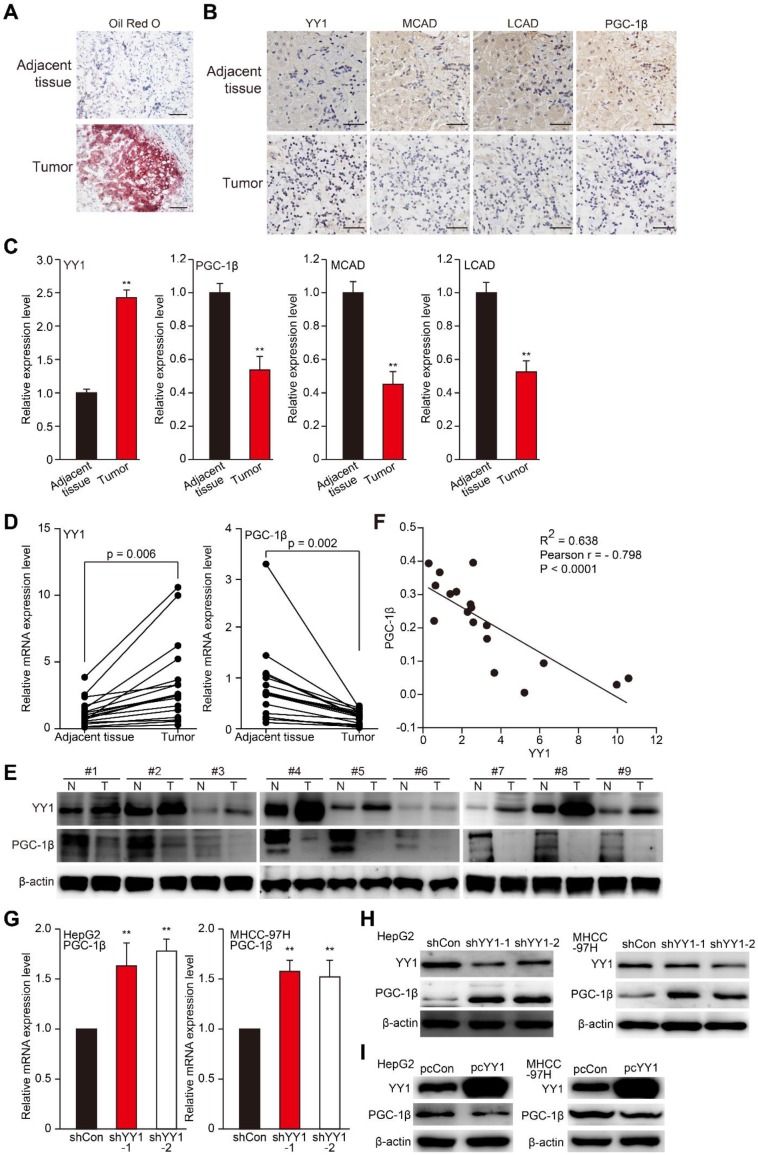

To investigate the relations between YY1 and lipid accumulation in HCC, we first examined lipid accumulation, as well as levels of YY1, MCAD, LCAD, and PGC-1β in clinical HCC tissues. Previous studies demonstrated that PGC-1β is an upstream, common regulator of MCAD and LCAD that enhances their expression, and thus is crucial for fatty acid β-oxidation 7, 30. As shown in Figure 3A-C, compared with normal adjacent tissue, Oil Red O (A) and immunohistochemical staining results of clinical HCC tissues showed elevated lipid accumulation along with increased YY1 level in HCC lesions; whereas MCAD and LCAD levels were lower (B-C). Additionally, we found a decrease of PGC-1β level in clinical HCC tissues relative to those in normal adjacent tissues. Moreover, qRT-PCR and western blot analysis further confirmed that compared to the corresponding normal adjacent tissues, YY1 expression was upregulated in clinical HCC tissues, while PGC-1β was suppressed (Figure 3D-E). Furthermore, correlation analysis of YY1 and PGC-1β mRNA expression in clinical HCC tissues and normal adjacent tissues showed a negative correlation (Figure 3F, Figure S4A). To confirm YY1-specific regulation of PGC-1β expression, we examined PGC-1β expression in YY1-silenced HCC cells, finding that YY1 silencing significantly upregulated PGC-1β mRNA (Figure 3G). In line with this, the expression level of PGC-1β protein was upregulated in YY1-silenced cells (Figure 3H), and suppressed in YY1-overexpressed cells (Figure 3I). These results clearly suggested that YY1 negatively regulates PGC-1β at the transcriptional level, and that YY1/PGC-1β pathway might be involved in HCC progression.

Figure 3.

YY1 negatively regulates PGC-1β at the transcriptional level in HCC cell. A. The accumulation of lipid droplets in the clinical HCC tissue and the normal adjacent tissue, as analyzed using Oil Red O staining. Scale bars: 200 μm. B-C. The expression levels of YY1, MCAD, LCAD and PGC-1β in the clinical HCC tissue and the normal adjacent tissue, as analyzed by immunohistochemical staining using serial sections. Representative images (B) and the quantification results (C, n = 6) are shown. Scale bars: 40 μm. Quantification results are shown as relative to adjacent tissue. D-E. The mRNA (D, n = 18) and protein (E, n = 9) expression levels of YY1 and PGC-1β in clinical human HCC and the corresponding normal adjacent tissues. F. Correlation analysis between the mRNA expression levels of YY1 and PGC-1β in clinical HCC tissue. G-H. PGC-1β mRNA (G) and protein (H) expression levels in YY1-silenced HepG2 and MHCC-97H cells cultured under hypoxic condition, as determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3) and western blotting, respectively. I. PGC-1β protein expression levels in YY1-overexpressed HepG2 (left) and MHCC-97H (right) cells cultured under hypoxia, as determined using western blotting. Cells transfected with shCon or pcCon were used as controls. β-actin was used for qRT-PCR normalization and as western blotting loading control. Quantification data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. pcCon: pcDNA3.1(+); **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

YY1 suppresses fatty acid β-oxidation by inhibiting the PGC-1β/MCAD and PGC-1β/LCAD axis

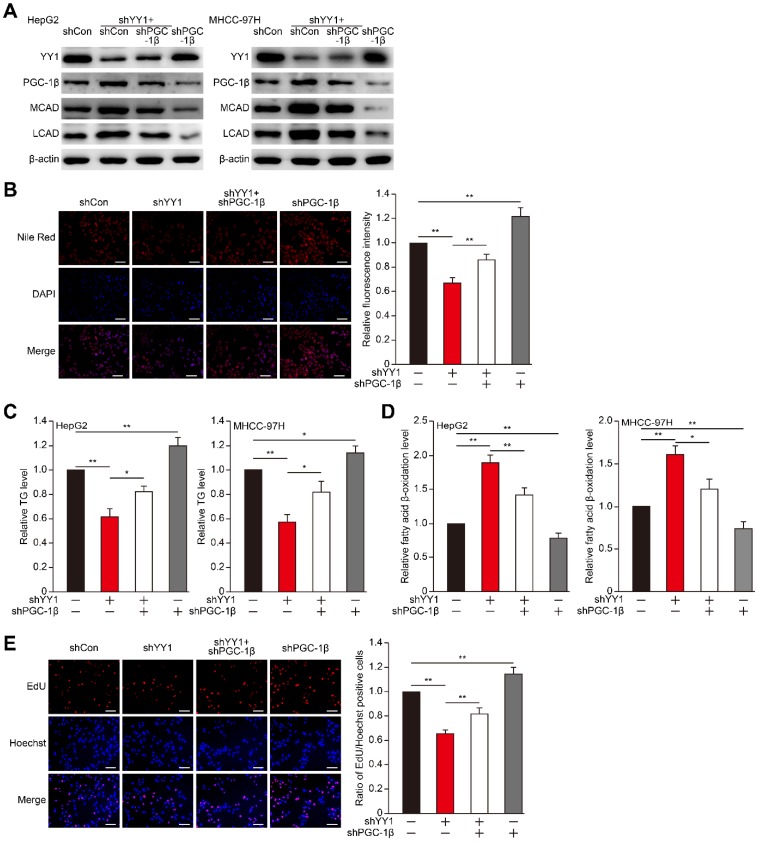

To examine the role of PGC-1β in YY1-regulated HCC cell lipid accumulation, we first constructed shRNA against PGC-1β (Figure S4B-C), and performed YY1/PGC-1β double silencing (Figure S4D-E). YY1/PGC-1β double silencing suppressed MCAD and LCAD mRNA (Figure S4F-G) as well as protein (Figure 4A) expression in both HepG2 and MHCC-97H cells. Concomitantly, YY1/PGC-1β double silencing re-induced lipid and TG accumulation suppressed by YY1 silencing alone (Figure 4B-C). Furthermore, PGC-1β silencing cancelled the observed increase in fatty acid β-oxidation level induced by YY1 silencing (Figure 4D), suggesting that YY1 negatively regulates the PGC-1β/MCAD and PGC-1β/LCAD axis to block fatty acid β-oxidation and subsequently increase lipid accumulation. As YY1 is a positive regulator of tumor cell proliferation, and that lipid accumulation is crucial for tumor cell proliferation, we further investigated the role of YY1/PGC-1β axis in HCC cell proliferation. Our results showed that PGC-1β silencing restored the proliferative potential (Figure 4E) and total cell number (Figure S4H) suppressed by YY1 silencing alone. These results indicated that YY1 regulation of lipid accumulation and subsequent effect on HCC cell proliferation and tumorigenesis potential occurred through inhibition of PGC-1β expression.

Figure 4.

PGC-1β is critical for YY1-induced lipid accumulation in HCC cell. A. The protein expression levels of PGC-1β, MCAD and LCAD in YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced HepG2 (left) and MHCC-97H (right) cells, as examined using western blotting. B. The accumulation of lipid droplets in YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced HepG2 cells, as analyzed using Nile Red staining. Representative images (left) and relative fluorescence intensity (right, n = 9) are shown. C-D. The levels of cellular TG (C) and fatty acid β-oxidation (D) in YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced HepG2 (left) and MHCC-97H (right) cells (n = 3). E. Number of proliferative YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced HepG2 cells, as determined by EdU incorporation assay. Representative images (left) and ratio of the EdU positive cells to the total cell number (right) are shown (n = 9). All experiments were performed under hypoxic condition. Cells transfected with shCon were used as controls. β-actin was used as western blotting loading control. Quantification data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Scale bars: 200 μm. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

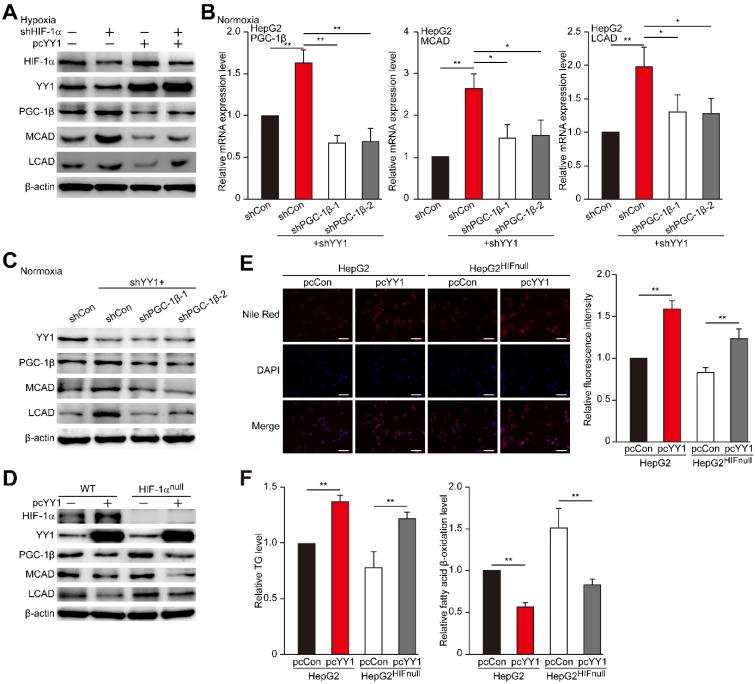

YY1 regulates PGC-1β irrespective of HIF-1α status

Previous reports showed that PGC-1β is regulated by HIF-1α 7, and that YY1 stabilizes HIF-1α protein under hypoxic condition 19. Therefore, we next assessed whether YY1 regulation of PGC-1β occurs in a HIF-1α-dependent manner. Indeed, we found that overexpression of HIF-1α partially suppressed the protein expression levels of PGC-1β, MCAD and LCAD upregulated by YY1-silencing (Figure S5A-B), suggesting the presence of HIF-1α-dependent pathway in YY1 regulation on PGC-1β. To determine whether HIF-1α is compulsory in YY1/PGC-1β pathway, we examined the effect of YY1 overexpression in HIF-1α-silenced cells (Figure S5C). As shown in Figure 5A, consistent with our previous report 19, YY1 overexpression enhanced the accumulation of HIF-1α protein; however, intriguingly, our results clearly showed that similar to that in the cells with HIF-1α, YY1 overexpression continued to significantly suppress PGC-1β level, as well as its downstream targets, even in HIF-1α-silenced cells. These results showed that YY1 regulation on PGC-1β could also occur in a HIF-1α-independent manner.

Figure 5.

YY1 regulates HCC cell lipid accumulation in a HIF-1α independent pathway. A. Protein expression levels of PGC-1β, MCAD and LCAD in HIF-1α-silenced HepG2 cells overexpressing YY1 cultured under hypoxic condition, as examined using western blotting. B-C. mRNA (B) and protein (C) expression levels of PGC1-β, MCAD and LCAD in YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced HepG2 cells cultured under normoxic condition, as determined using qRT-PCR (n = 3) and western blotting, respectively. D. Protein expression level of PGC-1β, MCAD and LCAD in YY1-overexpressed HIF-1α-knocked out HepG2 cells (HepG2HIFnull) cultured under hypoxic condition, as determined using western blotting. E. The accumulation of lipid droplets in YY1-overexpressed HepG2HIFnull cells cultured under hypoxic condition, as analyzed using Nile Red staining. Representative images (left) and relative fluorescence intensity (right, n = 9) are shown. F. The level of cellular TG (left) and fatty acid β-oxidation (right) in YY1-overexpressed HepG2HIFnull cells cultured under hypoxic condition (n = 3). Cells transfected with shCon or pcCon were used as controls. β-actin was used for qRT-PCR normalization and as western blotting loading control. Quantification data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Scale bars: 200 μm. pcCon: pcDNA3.1(+); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

HIF-1α is a master regulator of the response to hypoxia, as it is stabilized under hypoxic condition while being hydroxylated at Pro402 and Pro564 under normoxic condition, leading to its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation rapidly 36-39. Given that YY1 could also regulate PGC-1β in a HIF-1α-independent manner, we next examined the effect of YY1 silencing on PGC-1β under normoxic condition, in which HIF-1α was degraded and almost undetectable (Figure S5D). Concomitant with the effect on HIF-1α-silenced cells, we observed increased levels of PGC-1β, MCAD, and LCAD in YY1-silenced cells under normoxic condition, whereas silencing both YY1 and PGC-1β attenuated MCAD and LCAD levels (Figure 5B-C). Similarly, we found that PGC-1β silencing restored TG and fatty acid β-oxidation level altered by YY1 silencing under normoxic condition (Figure S5E). These results clearly indicated that YY1 could regulate HCC cell lipid accumulation through PGC-1β/MCAD and PGC-1β/LCAD axis even when HIF-1α was absence, suggesting the presence of HIF-1α-independent pathway in YY1 regulation of PGC-1β-induced fatty acid β-oxidation.

To further confirm this finding, we constructed a HIF-1α-null HepG2 cell line (HepG2HIFnull) using the CRISPR/Cas9 method (Figure S5F). We then overexpressed YY1 in HepG2HIFnull cells, and analyzed its effect on the levels of PGC-1β and its downstream targets under hypoxic condition. We found that similar to results in wild-type HepG2 cells, YY1 overexpression in HepG2HIFnull cells significantly suppressed PGC-1β, MCAD, and LCAD expression in their mRNA (Figure S5G) and protein (Figure 5D) levels. Furthermore, YY1 overexpression significantly upregulated lipid accumulation, as well as TG level, in HepG2HIFnull cells under hypoxic condition, most likely due to the inhibition of fatty acid β-oxidation (Figure 5E-F). These results clearly demonstrated the presence of a HIF-1α-independent pathway involved in YY1-dependent fatty acid β-oxidation inhibition.

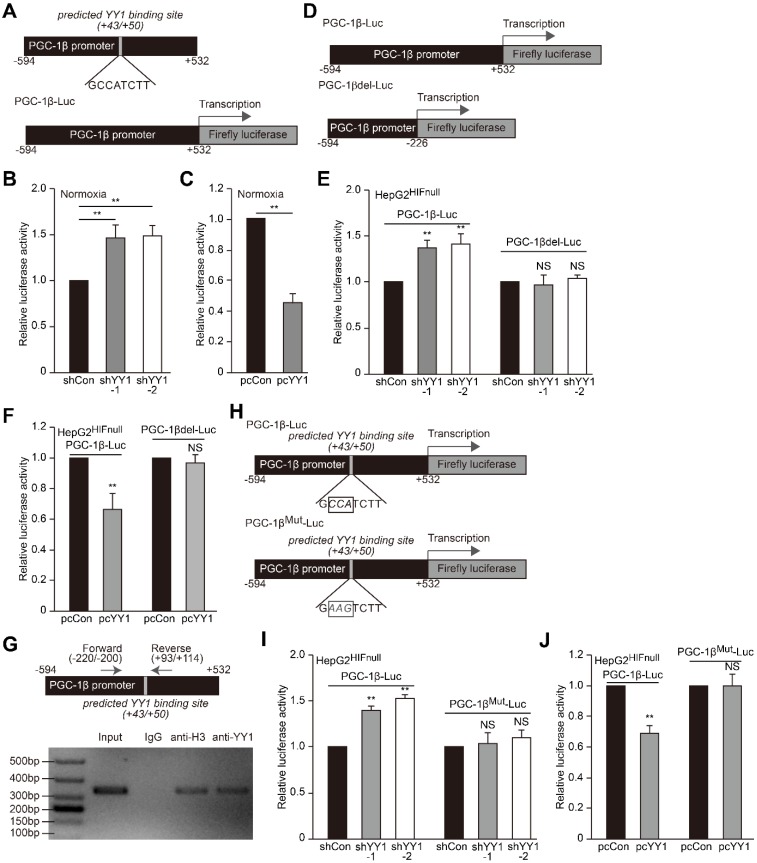

YY1 binds to the PGC-1β promoter and suppresses its transcription

As YY1 negatively regulates PGC-1β level in the absence of HIF-1α, we next investigated whether YY1 directly regulates PGC-1β transcription. According to the UCSC genome browser, we identified a YY1 consensus binding site in the PGC-1β promoter region (+43 to +50, Figure 6A upper panel) 40; thus we first examined the effect of manipulating YY1 expression on PGC-1β transcription using a luciferase reporter bringing the -594 to +532 region of the PGC-1β promoter (PGC-1β-Luc, Figure 6A lower panel). A dual luciferase assay using the reporter vector revealed that under normoxic condition, YY1 silencing significantly induced PGC-1β-Luc activity, whereas YY1 overexpression significantly reduced it (Figure 6B-C), indicating that YY1 might negatively regulate PGC-1β transcription. Next we constructed a luciferase-reporter vector without YY1 binding site harboring the -594 to -226 region of the PGC-1β promoter (PGC-1βdel-Luc; Figure 6D), followed by evaluation of the effect of YY1 silencing. The results showed that while YY1 silencing resulted in the increase of PGC-1β-Luc activity in HepG2HIFnull cells under hypoxic condition, it failed to increase PGC-1βdel-Luc activity (Figure 6E). Consistently, YY1 overexpression significantly suppressed the activity of PGC-1β-Luc but not PGC-1βdel-Luc activity (Figure 6F). These results suggested that YY1 targeted the PGC-1β promoter in a HIF-1α-independent manner, and that the -227 to +532 region of the PGC-1β promoter was essential for regulation of YY1 on PGC-1β.

Figure 6.

YY1 binds to PGC-1β promoter and enhances its transcription independently of HIF-1α. A. Schematic diagrams of the predicted YY1 binding site in PGC-1β promoter and the luciferase reporter bringing PGC-1β promoter (PGC-1β-Luc). B-C. The activity of PGC-1β-Luc in YY1-silenced (B) and YY1-overexpressed (C) HepG2 cells cultured under normoxic condition, as analyzed by using dual luciferase assay (n = 3). D. Schematic diagram of firefly luciferase reporter bringing the PGC-1β promoter lacking YY1 binding site (PGC-1βdel-Luc). E-F. The activities of PGC-1β-Luc and PGC-1βdel-Luc in YY1-silenced (E) and YY1-overexpressed (F) HepG2HIFnull cells cultured under hypoxic condition, as analyzed using dual luciferase assay (n = 3). G. Binding of YY1 to the promoter region of PGC-1β in HepG2 cells as examined using chromatin immunoprecipitation assay with anti-YY1 antibody followed by PCR. Location of the primer set (top) and the length of the amplicon (bottom) are shown. H. Schematic diagram of the firefly luciferase reporter bringing PGC-1β promoter with mutated predicted YY1 binding site (PGC-1βMut-Luc). Wild-type nucleotides are shown in black, and mutated ones are shown in gray. I-J. The activities of PGC-1β-Luc and PGC-1βMut-Luc in YY1-silenced (I) and YY1-overexpressed (J) HepG2HIFnull cells cultured under hypoxic condition, as analyzed using dual luciferase assay (n = 3). Cells transfected with shCon or pcCon were used as controls. Quantification data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. pcCon: pcDNA3.1(+); **P < 0.01; NS: not significant (ANOVA).

We then analyzed whether YY1 binds the predicted site within the PGC-1β promoter. We first performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay using the indicated primers flanking the predicted YY1 binding site (Figure 6G, upper panel), finding that the corresponding promoter region was detected in the chromatin immunoprecipitated using the anti-YY1 antibody (Figure 6G, lower panel). This result indicated that YY1 binds to the -220 to +114 region of the PGC-1β promoter. To assess function of the predicted YY1-binding site, we constructed a mutant PGC-1β-Luc reporter (PGC-1βMut-Luc) by mutating 3 nucleotides in the predicted YY1-binding site (GCCATCTT to GAAGTCTT) (Figure 6H). As shown in Figure 6I, while YY1-silencing robustly induced the activity of the wild-type PGC-1β-Luc reporter in HepG2HIFnull cells cultured under hypoxic condition, this effect was diminished upon use of the PGC-1βMut-Luc reporter. In agreement with this result, compared to cells transfected with control vector, YY1 overexpression failed to suppress the activity of the PGC-1βMut-Luc reporter while significantly reduce that of the PGC-1β-Luc reporter (Figure 6J). These results suggested that YY1 directly regulates PGC-1β transcription through binding its promoter in the +43 to +50 region; and that this regulation occurs independent of HIF-1α status.

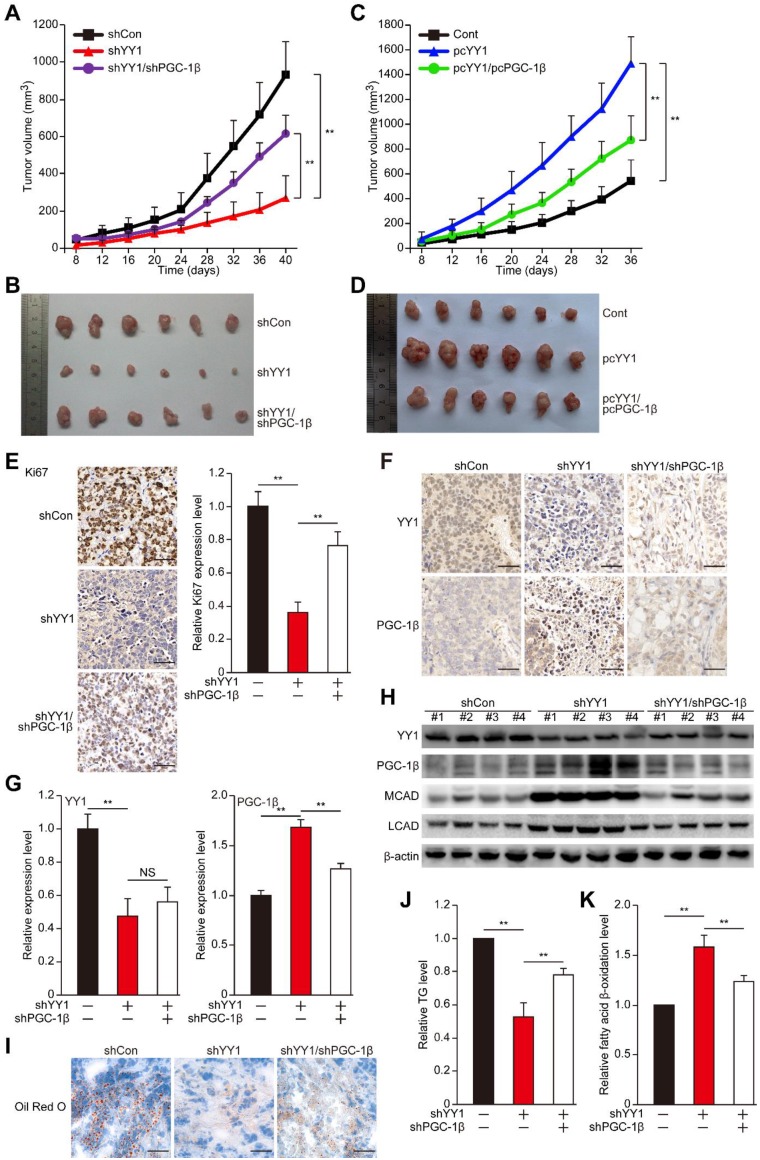

The YY1/PGC-1β axis is critical for hepatocarcinogenesis potential

Next we examined the role of YY1/PGC-1β axis in hepatocarcinogenesis. While knocking down YY1 suppressed HCC cells colony formation potential, double knocked down of YY1 and PGC-1β restored it (Figure S6), indicating that PGC-1β might be involved in YY1-mediated hepatocarcinogenesis. To confirm this, finally we examined the pathological function of the YY1/PGC-1β pathway in hepatocarcinogenesis potential in vivo. To this end, we constructed stable YY1-silenced and YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced cell lines (Figure S7A), as well as YY1-overexpression and YY1/PGC-1β-double overexpressed cell lines (Figure S7B) using MHCC-97H cells. Xenograft experiments showed that YY1 silencing reduced the tumorigenesis potential of MHCC-97H cells; however, silencing of both YY1 and PGC-1β significantly restored this potential (Figure 7A-B). Furthermore, while YY1-overexpression robustly enhanced tumorigenesis potential, overexpression of both YY1 and PGC-1β reduced it (Figure 7C-D), suggesting that YY1/PGC-1β axis is crucial for promoting hepatocarcinogenesis. Moreover, Ki67 staining results also showed that the number of proliferative cells was conspicuously lower in xenografted tumors originating from YY1-silenced MHCC-97H cells, while PGC-1β-silencing significantly restored it (Figure 7E). Consistent with this finding, immunohistochemical staining results also revealed an upregulation of PGC-1β level in xenografts generated from YY1-silenced cells, whereas silencing of both YY1 and PGC-1β cancelled this effect (Figure 7F-G). Western blotting analysis also confirmed these results, as inhibition of YY1 expression correlating with significant increase in PGC-1β, MCAD and LCAD protein levels (Figure 7H).

Figure 7.

YY1 mediates hepatocarcinogenesis potential by negatively regulates PGC-1β. A-B. Hepatocarcinogenesis potential of control (shCon), YY1-silenced (shYY1) and YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced (shYY1/shPGC-1β) MHCC-97H stable cell lines were examined in vivo by subcutaneous injection into Balb/c-nu/nu mice (n = 6). Volume of the tumors formed at indicated time points (A) and the appearance (B) are shown. C-D. Hepatocarcinogenesis potential of control (Cont), YY1-overexpressed (pcYY1) and YY1/PGC-1β-double overexpressed (pcYY1/pcPGC-1β) MHCC-97H stable cell lines were examined in vivo by subcutaneous injection into Balb/c-nu/nu mice (n = 6). Volume of the tumors formed at indicated time points (C) and the appearance (D) are shown. E. Proliferative cells in the tissue section of xenografted tumors in Balb/c-nu/nu mice injected with the indicated cell lines, as stained using Ki67. Scale bars: 40 μm. Representative images (left) and quantification results (right, n = 6) are shown. F-G. Immunohistochemical staining images against YY1 (top) and PGC-1β (bottom) in the tissue section of xenografted tumors in Balb/c-nu/nu mice injected with the indicated cell lines. Scale bars: 40 μm. Representative images (F) and relative expression level (G) are shown (n = 6). Quantification was performed by counting the ratio of the positive cells to total cell number, and the results are shown as relative to control. H. YY1, PGC1-β, MCAD and LCAD protein expression levels in the xenografted tumors in Balb/c-nu/nu mice injected with the indicated cell lines were examined using western blotting. I. The accumulation of lipid droplets in the tissue section of xenografted tumors in Balb/c-nu/nu mice injected with the indicated cell lines were stained using Oil Red O staining. J-K. The level of cellular TG (J) and fatty acid β-oxidation (K) in the xenografted tumors in Balb/c-nu/nu mice injected with the indicated cell lines. Cells transfected with shCon or pcEF9-puro were used as controls. β-actin was used as western blotting loading control. Quantification data are shown as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01; NS: not significant (ANOVA).

To further reveal the relation between YY1/PGC-1β-induced tumorigenesis and lipid accumulation in vivo, we next examined the lipid accumulation, TG and fatty acid β-oxidation in xenografted tumors. Significant decreases of lipid accumulation and TG were observed in the xenografted tumors originating from YY1-silenced cells; however, the amounts of lipid accumulation and TG were restored in tumors originating from YY1/PGC-1β-double silenced cells (Figure 7I-J). In line with this, YY1/PGC-1β-double silencing significantly attenuated the increase of fatty acid β-oxidation in xenografted tumors induced by YY1 silencing alone (Figure 7K). These results clearly showed a negative correlation between YY1 and PGC-1β expression, as well as the importance of YY1/PGC-1β axis in lipid metabolism and tumor progression of hepatocellular carcinoma.

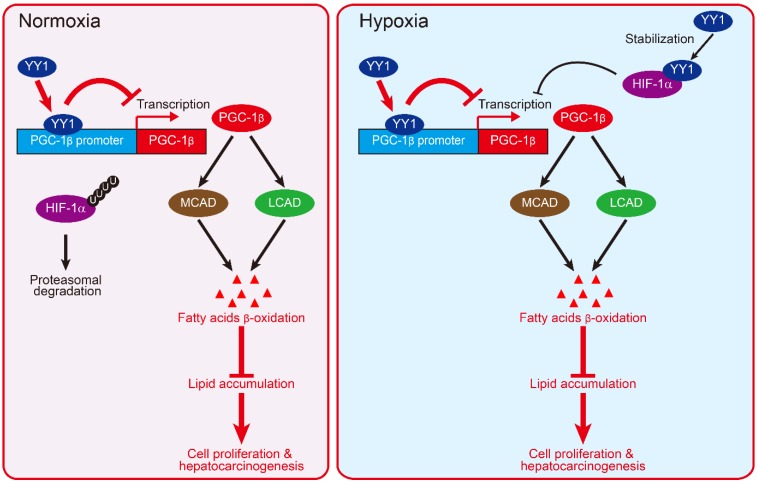

Together, our results described a novel regulatory mechanism involved in HCC cell lipid metabolic reprogramming. We found that YY1 suppressed PGC-1β transcription by directly binds to its promoter, resulting in subsequent suppression of MCAD and LCAD levels and decreased fatty acid β-oxidation irrespective of HIF-1α status. This in turn elevated lipid accumulation, which is a crucial driver of hepatocarcinogenesis (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram showing the mechanism of YY1/PGC-1β axis-mediated HCC cells lipid metabolism in both normoxia and hypoxia.

Discussion

Metabolic reprogramming is a characteristic of tumor cells and is essential for supporting their rapid proliferation, as it provides tumor cells with several benefits, including macromolecule biosynthesis, adaptation to the microenvironment, and an ability to cope with oxidative stress 1, 2, 41. Lipid metabolic reprogramming enables tumor cells to meet the demand of their highly proliferative growth 42, and is an important driving force for HCC development 7, 35. Specifically, lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells induces aberrant lipid accumulation 3. Consequently, this facilitates tumorigenesis by providing tumor cells with both the energy and materials necessary for the biosynthesis of signaling molecule such as arachidonic acid, as well as phospholipids as the major component of cell membranes 4, 43. In the present study, our findings reveal that the transcription factor YY1 is critical for lipid metabolism in HCC cells, as it negatively regulates fatty acid β-oxidation by directly binds to the PGC-1β promoter and suppresses its transcription under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. YY1-mediated downregulation of PGC-1β expression in turn attenuates MCAD and LCAD levels, leading to the suppression of fatty acid β-oxidation and subsequently lipid accumulation. Furthermore, as previous studies revealed that PGC-1β is crucial for muscle-cell metabolism and suppressing inflammation 44, 45, our results also suggest the possibility of YY1 involvement in other biological processes apart from tumorigenesis through the YY1/PGC-1β axis.

Previous studies showed that aberrant YY1 expression is observed in cancers, including colon, breast, liver and pancreatic cancers 23-27. YY1 has been implicated in tumor progression, as it could enhance cell proliferation by facilitating interactions between the tumor suppressor p53 and its upstream negative regulator mouse double-minute homolog-2, thereby inducing p53 degradation 18. Moreover, YY1 destabilizes p53 and blocks p53-mediated transcriptional activity by disrupting its interaction with p300 17. Furthermore, YY1 supports tumor cell proliferation and survival by inducing tumor angiogenesis 16, 19. Despite its importance as an oncogene, the role of YY1 in tumor cell lipid metabolism remains unraveled. Our present study elucidates a novel, critical role of YY1 in regulating tumor cell lipid homeostasis, especially by regulating fatty acid β-oxidation, linking up YY1 with tumor cell lipid metabolic reprogramming, another characteristic of tumor cell which is critical for supporting its survival, tumor progression, and metastasis 7, 46, 47. YY1 is a transcription factor crucial for the regulation of various genes 48, and furthermore, a recent report revealed that it could regulate gene expression as a structural regulators of enhancer-promoter loops 20. Hence, YY1 might also regulate lipid metabolism-related factors at their transcriptional level, indicating that although further investigation is needed, there might be alternative pathways of YY1 regulation on tumor cells lipid metabolism. Nevertheless, our findings showed for the first time the crucial role of YY1/PGC-1β pathway in tumor cells lipid metabolism.

HIF-1α is a factor induced by hypoxia. It regulates the transcription of various genes involved in cell proliferation and survival, metabolic reprogramming, and other functions that support cell-specific adaptation to the tumor hypoxic microenvironment. Huang et al reported that HIF-1α suppresses FAO and enhances lipid accumulation 7. On the other hand, our previous study has shown that under hypoxic condition, YY1 inhibits HIF-1α proteasomal degradation, thereby stabilizing HIF-1α protein level 19. In the present study, we show that YY1 suppresses PGC-1β transcription even in the absence of HIF-1α by directly binds to its promoter. This enables the YY1/PGC-1β axis to regulate lipid accumulation in HCC cells not only under hypoxic condition in both HIF-1α-dependent and -independent manners, but also under the presence of oxygen, during which HIF-1α is hydroxylated and degraded (Figure 8). The ability of YY1 to regulate tumor cell lipid metabolism in a HIF-1α-independent manner also provides evidence of the importance of HIF-1α-independent pathways in tumorigenesis.

Our results reveal that YY1 could induce HCC cell lipid accumulation under both hypoxic and normoxic conditions. Due to the rapid proliferation of tumor cells, oxygen pressure in tumor tissues is negatively correlated with their distance from blood vessels, thereby resulting in their inevitable exposure to hypoxic condition. Tumor cells not only adapt to hypoxic microenvironments, but hypoxia in turn supports tumor development. However, not all cells in tumor tissue are consistently exposed to hypoxic condition. A previous study reported that in tumor tissue with a diameter < 1 mm, oxygen could be supplied by diffusion from blood vessels 49. Furthermore, tumor cells secrete various angiogenic factors that induce the formation of new blood vessels in order to increase their supply of oxygen and nutrients; although, the abnormal architecture and patterns of tumor vasculature results in unstable oxygen supply 50. In the present study, our results reveal that the YY1/PGC-1β axis regulates HCC cell lipid metabolic reprogramming under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions, suggesting that this pathway is common in tumor cells, regardless of their location in tumor tissue. Additionally, this regulatory pathway likely ensures continuous lipid accumulation without being affected by a fluctuating oxygen supply. This pathway might also enable enhanced lipid accumulation in both early-stage tumor with relatively smaller size, and in late-stage tumor with relatively larger size. Furthermore, previous studies reported both increased YY1 expression and lipid accumulation in NAFLD 29, 51, which can progress to cirrhosis and subsequently HCC 10, 52. Therefore, although further investigation is required, our results demonstrate the possibility that activation of the YY1/PGC-1β axis might be crucial for liver metabolic disorder diseases, and that it might be a potential driver of HCC development from hepatic steatosis.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrate a novel role for YY1 in promoting hepatocellular carcinoma progression by altering HCC cell lipid metabolism independent of oxygen pressure. These results not only provide insight regarding the molecular mechanism of tumor cell lipid metabolism, but also a new perspective regarding the function of YY1 in tumor progression. Therefore, our study provides evidences regarding the potential of YY1 as a target for anti-tumor therapies based on targeting tumor cell lipid metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Miyagishi Makoto (National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Japan) for kindly predicting shRNA target sites and providing pcEF9-puro vector. We thank Dr. Xingming Liu (Biological Resource Bank, Chongqing University Cancer Hospital, Chongqing University, China) for his kind helps in collecting and storing human clinical samples, and Oncology Precision Medicine Research Center, Chongqing University Cancer Hospital for technical support during this study. We also thank Prof. Yemiao Chen (The Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China) for his advices during manuscript preparation. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11832008, 81872273 and 31871367); the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (cstc2018jcyjAX0374 and cstc2018jcyjAX0411); and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019CDQYSW010).

Author Contributions

V.K. and S.W. conceived the project, design the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the experimental results, wrote the manuscript and supervised all the work. Y.L. carried out most of the experiments, analyzed the experimental data and prepared the manuscript. X.Y carried out screening, luciferase assay, Nile Red staining, and ChIP assay. L.L., I.T.S.M., and Z.L. carried out qRT-PCR and western blotting analysis. C.H. performed xenograft experiments. K.L. constructed plasmids. S.G. analyzed part of the data and provided part of the material. X.Z. collected and analyzed human clinical samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- YY1

yin yang 1

- YY2

yin yang 2

- PGC-1β

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1β

- FAS

fatty acid synthesis

- FAO

fatty acid oxidation

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- TG

triglyceride

- MCAD

medium-chain acyl-CoA-dehydrogenase

- LCAD

long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase

- HMGCR

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA-reductase

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

References

- 1.DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv. 2016;2:e1600200–18. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin YH, Wu MH, Huang YH, Yeh CT, Cheng ML, Chi HC. et al. Taurine up-regulated gene 1 functions as a master regulator to coordinate glycolysis and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:188–203. doi: 10.1002/hep.29462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulze A, Harris AL. How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature. 2012;491:364–73. doi: 10.1038/nature11706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Currie E, Schulze A, Zechner R, Walther TC, Farese RV Jr. Cellular fatty acid metabolism and cancer. Cell Metab. 2013;18:153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo X, Cheng C, Tan Z, Li N, Tang M, Yang L. et al. Emerging roles of lipid metabolism in cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:76–86. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0646-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Cellular metabolism and disease: what do metabolic outliers teach us? Cell. 2012;148:1132–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Li T, Li X Zhang L, Sun L He X. et al. HIF-1-mediated suppression of acyl-CoA dehydrogenases and fatty acid oxidation is critical for cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1930–42. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakazawa MS, Keith B, Simon MC. Oxygen availability and metabolic adaptations. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:663–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du W, Zhang L, Brett-Morris A, Aguila B, Kerner J, Hoppel CL. et al. HIF drives lipid deposition and cancer in ccRCC via repression of fatty acid metabolism. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1769. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01965-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starley BQ, Calcagno CJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a weighty connection. Hepatology. 2010;51:1820–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smagris E, BasuRay S, Li J, Huang Y, Lai KM, Gromada J. et al. Pnpla3I148M knockin mice accumulate PNPLA3 on lipid droplets and develop hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2015;61:108–18. doi: 10.1002/hep.27242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seto E, Shi Y, Shenk T. YY1 is an initiator sequence-binding protein that directs and activates transcription in vitro. Nature. 1991;354:241–5. doi: 10.1038/354241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Y, Seto E, Chang LS, Shenk T. Transcriptional repression by YY1, a human GLI-Kruppel-related protein, and relief of repression by adenovirus E1A protein. Cell. 1991;67:377–88. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Wu S, Huang C, Li Y, Zhao H, Kasim V. Yin Yang 1 promotes the Warburg effect and tumorigenesis via glucose transporter GLUT3. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:2423–34. doi: 10.1111/cas.13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan X, Chen J, Cheng Q, Zhao Y, Zhang P, Shao X. et al. Hepatic expression of Yin Yang 1 (YY1) is associated with the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) progression in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:147–56. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0871-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Nigris F, Crudele V, Giovane A, Casamassimi A, Giordano A, Garban HJ. et al. CXCR4/YY1 inhibition impairs VEGF network and angiogenesis during malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14484–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008256107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gronroos E, Terentiev AA, Punga T, Ericsson J. YY1 inhibits the activation of the p53 tumor suppressor in response to genotoxic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12165–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402283101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sui G, Affar el B, Shi Y, Brignone C, Wall NR, Yin P. et al. Yin Yang 1 is a negative regulator of p53. Cell. 2004;117:859–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu S, Kasim V, Kano MR, Tanaka S, Ohba S, Miura Y. et al. Transcription factor YY1 contributes to tumor growth by stabilizing hypoxia factor HIF-1alpha in a p53-independent manner. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1787–99. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weintraub AS, Li CH, Zamudio AV, Sigova AA, Hannett NM, Day DS. et al. YY1 Is a Structural Regulator of Enhancer-Promoter Loops. Cell. 2017;171:1573–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.008. e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donohoe ME, Zhang X, McGinnis L, Biggers J, Li E, Shi Y. Targeted disruption of mouse Yin Yang 1 transcription factor results in peri-implantation lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7237–44. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atchison ML. Function of YY1 in Long-Distance DNA Interactions. Front Immunol. 2014;5:45–56. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chinnappan D, Xiao D, Ratnasari A, Andry C, King TC, Weber HC. Transcription factor YY1 expression in human gastrointestinal cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1417–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasim V, Xie YD, Wang HM, Huang C, Yan XS, Nian WQ. et al. Transcription factor Yin Yang 2 is a novel regulator of the p53/p21 axis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:54694–707. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan P, He XH, Rong YF, Cao J, Li Y, Hu YP. et al. KRAS/NF-kappaB/YY1/miR-489 Signaling Axis Controls Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2017;77:100–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal N, Dancik GM, Goodspeed A, Costello JC, Owens C, Duex JE. et al. GON4L Drives Cancer Growth through a YY1-Androgen Receptor-CD24 Axis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:5175–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsang DP, Wu WK, Kang W, Lee YY, Wu F, Yu Z. et al. Yin Yang 1-mediated epigenetic silencing of tumour-suppressive microRNAs activates nuclear factor-kappaB in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pathol. 2016;238:651–64. doi: 10.1002/path.4688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang HY, Li X, Liu M, Song TJ, He Q, Ma CG. et al. Transcription factor YY1 promotes adipogenesis via inhibiting CHOP-10 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;375:496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Ma Z, Zhang Z, Xiong X, Wang X, Zhang H. et al. Yin Yang 1 promotes hepatic steatosis through repression of farnesoid X receptor in obese mice. Gut. 2014;63:170–8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Zhang L, Smith KL, Morel CR. et al. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1beta attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lea W, Abbas AS, Sprecher H, Vockley J, Schulz H. Long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase is a key enzyme in the mitochondrial beta-oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1485:121–8. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyagishi M, Taira K. Strategies for generation of an siRNA expression library directed against the human genome. Oligonucleotides. 2003;13:325–33. doi: 10.1089/154545703322617005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ackerman D, Tumanov S, Qiu B, Michalopoulou E, Spata M, Azzam A. et al. Triglycerides Promote Lipid Homeostasis during Hypoxic Stress by Balancing Fatty Acid Saturation. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.015. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu DT, Phuong TNT, Tien NLB, Tran DK, Nguyen TT, Thanh VV. et al. The Effects of Adipocytes on the Regulation of Breast Cancer in the Tumor Microenvironment: An Update. Cells. 2019;8:857–76. doi: 10.3390/cells8080857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Che L, Chi W, Qiao Y, Zhang J, Song X, Liu Y, Cholesterol biosynthesis supports the growth of hepatocarcinoma lesions depleted of fatty acid synthase in mice and humans. Gut. 6 Apr; 2019. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berra E, Benizri E, Ginouves A, Volmat V, Roux D, Pouyssegur J. HIF prolyl-hydroxylase 2 is the key oxygen sensor setting low steady-state levels of HIF-1alpha in normoxia. EMBO J. 2003;22:4082–90. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando J, Ohh M. et al. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaelin WG Jr, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semenza GL. A compendium of proteins that interact with HIF-1alpha. Exp Cell Res. 2017;356:128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM. et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Li X, Zhang J, Yang Q, Chen W, Jin W. et al. AHNAK2 is a Novel Prognostic Marker and Oncogenic Protein for Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Theranostics. 2017;7:1100–13. doi: 10.7150/thno.18198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nomura DK, Long JZ, Niessen S, Hoover HS, Ng SW, Cravatt BF. Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates a fatty acid network that promotes cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2010;140:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao Y, Pearman AT, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM. Intracellular unesterified arachidonic acid signals apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11280–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200367597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakkar N, Ladner K, Canan BD, Liyanarachchi S, Bal NC, Pant M. et al. IKKalpha and alternative NF-kappaB regulate PGC-1beta to promote oxidative muscle metabolism. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:497–511. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Liu Y, Li D, Song J, Xia M. PGC-1beta suppresses saturated fatty acid-induced macrophage inflammation by inhibiting TAK1 activation. IUBMB Life. 2016;68:145–55. doi: 10.1002/iub.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sounni NE, Cimino J, Blacher S, Primac I, Truong A, Mazzucchelli G. et al. Blocking lipid synthesis overcomes tumor regrowth and metastasis after antiangiogenic therapy withdrawal. Cell Metab. 2014;20:280–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin H, He Y, Zhao P, Hu Y, Tao J, Chen J. et al. Targeting lipid metabolism to overcome EMT-associated drug resistance via integrin beta3/FAK pathway and tumor-associated macrophage repolarization using legumain-activatable delivery. Theranostics. 2019;9:265–78. doi: 10.7150/thno.27246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gordon S, Akopyan G, Garban H, Bonavida B. Transcription factor YY1: structure, function, and therapeutic implications in cancer biology. Oncogene. 2006;25:1125–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JY, Lee JY. Targeting Tumor Adaption to Chronic Hypoxia: Implications for Drug Resistance, and How It Can Be Overcome. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1854–67. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bristow RG, Hill RP. Hypoxia and metabolism. Hypoxia, DNA repair and genetic instability. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:180–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu GY, Rui C, Chen JQ, Sho E, Zhan SS, Yuan XW. et al. MicroRNA-122 Inhibits Lipid Droplet Formation and Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation via Yin Yang 1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44:1651–64. doi: 10.1159/000485765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science. 2011;332:1519–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1204265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.