Highlights

-

•

Superior biochemical progression free survival for LDR in combination with EBRT.

-

•

On multivariable analysis, HDR and EBRT and Gleason ≥8 predicted for progression.

-

•

Low cumulative incidence of ≥grade 3 GU and GI toxicities.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Low dose rate brachytherapy, High dose rate brachytherapy, External beam radiotherapy

Abstract

Introduction

There is evidence to support use of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) in combination with both low dose rate brachytherapy (LDR–EBRT) and high dose rate brachytherapy (HDR–EBRT) to treat intermediate and high risk prostate cancer.

Methods

Men with intermediate and high risk prostate cancer treated using LDR–EBRT (treated between 1996 and 2007) and HDR–EBRT (treated between 2007 and 2012) were identified from an institutional database. Multivariable analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between patient, disease and treatment factors with biochemical progression free survival (bPFS).

Results

116 men were treated with LDR-EBRT and 171 were treated with HDR–EBRT. At 5 years, bPFS was estimated to be 90.5% for the LDR–EBRT cohort and 77.6% for the HDR–EBRT cohort. On multivariable analysis, patients treated with HDR–EBRT were more than twice as likely to experience biochemical progression compared with LDR–EBRT (HR 2.33, 95% CI 1.12–4.07). Patients with Gleason ≥8 disease were more than five times more likely to experience biochemical progression compared with Gleason 6 disease (HR 5.47, 95% CI 1.26–23.64). Cumulative incidence of ≥grade 3 genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicities for the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT cohorts were 8% versus 4% and 5% versus 1% respectively, although these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusion

LDR–EBRT may provide more effective PSA control at 5 years compared with HDR–EBRT. Direct comparison of these treatments through randomised trials are recommended to investigate this hypothesis further.

1. Introduction

Dose escalation has been shown to result in improved biochemical progression free survival (bPFS) in localised prostate cancer (PCa) [1]. Doses of up to approximately 80 Gy can be delivered using external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) [2]. However, with brachytherapy (BT), steep dose gradients mean it is possible to deliver greater dose escalation, while meeting dose constraints of adjacent organs at risk (OAR), than would be possible with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) [3]. BT can also be combined with EBRT to achieve even greater dose escalation [4], [5].

Several studies, including randomised controlled trials (RCT), of patients with intermediate and high risk localised PCa have reported improved bPFS for both high dose rate BT (HDR) in combination with EBRT (HDR–EBRT) and low dose rate permanent seed BT (LDR) in combination with EBRT (LDR–EBRT) when compared to EBRT alone [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. However, there is a lack of randomised evidence directly comparing LDR–EBRT with HDR–EBRT.

Variable toxicity rates have been reported for HDR–EBRT and LDR–EBRT [3], [8], [9], [12], [17], [18], [19]. In a RCT comparing HDR–EBRT with EBRT alone, the reported incidence of ≥grade 3 genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicities at 5 years were 26% and 7% respectively [8]. In comparison, 5 year cumulative ≥grade 3 GU and GI toxicities of 18.4% and 8.1% were reported in the ASCENDE-RT study of LDR–EBRT versus dose escalated external beam radiotherapy (DE-EBRT) [20].

Advantages of HDR over LDR may include greater consistency of dose distribution for target volume coverage and normal tissue sparing, absence of seed migration and potentially lower costs [2]. If, as has been estimated, PCa has a low alpha/beta ratio, and therefore potentially greater susceptibility to large doses per fraction, it has been suggested that there could also be radiobiological advantages in favour of HDR [2], [21].

Patients have been treated at our centre using both LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT, thereby presenting an opportunity to compare outcomes for these two treatments.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient population

Between 1996 and 2012, 347 men consecutively treated for intermediate and high risk PCa using a combination of EBRT and BT boost at a single cancer centre were retrospectively identified from an institutional database. Patients were classified using the NCCN criteria. Intermediate risk disease was defined as the presence of one or more of the following factors: T2b disease, prostate specific antigen (PSA) >10 ng/ml or Gleason score 7 (ISUP Grade 2 or 3). High risk disease was defined as the presence of one or more of the following factors: ≥T2c disease, PSA >20 ng/ml or Gleason score ≥8 (ISUP Grade 4 or 5). Clinical staging used the AJCC TNM 7 system. Bone scintigraphic studies were performed for patients with high risk disease to exclude skeletal metastatic disease. Cross-sectional pelvic imaging was undertaken using MRI. 60 patients without record of a post implant PSA (because they were referred from other oncology centres) were excluded from the analysis in this study (48 treated with HDR–EBRT and 12 treated with LDR–EBRT), leaving 287 patients eligible for inclusion.

2.2. Treatment

2.2.1. LDR boost

Between 1996 and 2007, LDR–EBRT was used to treat patients with intermediate and high risk PCa. We previously described our LDR technique and long term outcomes following LDR monotherapy for localised PCa [22], [23]. The aim was to achieve a minimum peripheral dose of 110 Gy (prescribed as per TG43 guidelines) to the prostate capsule with a 3 mm isometric margin (except posteriorly where no margin was applied). Initially, a two step planning technique using the Seattle method was used with prostate volume estimated by transrectal ultrasound (TRUS). From 2000, most patients were treated using a single step technique.

TRUS based pre-planning objectives during this period included the prostate volume covered by 100% of the prescription dose (Vp100) of greater than 99% and a dose to 90% of the prostate (D90) of approximately 140 Gy. The D90 planned was expected to be higher than achieved. The mean central dose had an objective of less than 150% and a constraint for the rectal mucosal volume which received 100% (Vr100) of the prescription dose to be less than 1 cc. Urethra was not contoured as a separate structure. Post implant dosimetry was not mandatory during the time period covered by this study.

2.2.2. HDR boost

Between 2007 and 2012, HDR–EBRT was used to treat patients with intermediate and high risk PCa. HDR boost was performed under real time TRUS guidance. 14–20 needles were inserted into the prostate via a perineal template. Once the needles were positioned, the prostate and any seminal vesicle (SV) involvement were contoured and a 3 mm margin (isotropic apart from posteriorly) was added to generate the planning target volume (PTV). OAR (urethra and outer rectal wall) were outlined on ultrasound. Oncentra Prostate treatment planning software (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) was used to prospectively plan treatment delivery to provide an optimal dose distribution to target volume while minimising dose to OARs. Between 2007 and 2010, a dose fractionation of 17 Gy in 2 fractions delivered 1 week apart was used. From 2010, a single 15 Gy fraction was used. The use of a PTV in the treatment planning process was introduced for the single fraction regime, prior to this plans for the two fraction regime were optimised to the GTV only.

TRUS based planning objectives included the prostate plus any seminal vesicle involvement covered by the prescription dose (V100) of greater than 95% for both fractionation regimes. The PTV objective, VPTV100 greater than 90%, was introduced for the single fraction regime. Dose to 10% of the urethra (Durethra10%) was to be less than 10.25 Gy per fraction for the two fraction cohort and 17.5 Gy for the single fraction cohort. The rectum dose constraint is D2cc (minimum dose to the most irradiated 2 cc) less than 78.8% of the prescription dose.

2.2.3. EBRt

LDR boost was combined with 45 Gy in 20 fractions of EBRT to the prostate and SV delivered using 3D CRT. HDR boost delivered as 17 Gy in 2 fractions was combined with 35.75 Gy in 13 fractions of EBRT to the prostate and SV. HDR boost of 15 Gy in 1 fraction was combined with 37.5 Gy in 15 fractions of EBRT. Delivery of EBRT commenced 2–3 weeks after the BT boost. Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) was introduced from 2011.

2.2.4. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)

The majority of the patients received ADT, either by 3 monthly LHRH agonist subcutaneous injection (Prostap 11.25 mg or Zoladex 10.8 mg) or bicalutamide 150 mg once daily tablet. Duration of ADT varied between 6 and 36 months based on PCa risk stratification. Where it was administered, ADT was commenced as neoadjuvant therapy 3 months prior to the BT implant and the remaining course was given as adjuvant therapy.

2.2.5. Follow up

As per our departmental protocol, patients were followed up using PSA at 6 monthly intervals for the first 3 years post treatment and annually thereafter. Biochemical relapse was defined by a PSA of plus 2 ng/ml above the nadir value post treatment.

2.3. Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study is to compare bPFS in the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups. The secondary endpoint is to report the cumulative incidence of grade 3 or greater crude GU and GI toxicities.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS® version 21 (IBM, USA). Baseline patient and treatment characteristics for the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups were compared using a chi-squared independence test for categorical variables and a two sample t-test for continuous variables. Duration of follow up was calculated from the time of the BT procedure. Actuarial bPFS survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for univariable (UVA) and multivariable analysis (MVA) to assess factors associated with biochemical relapse free survival. The following variables were analysed by UVA: age, PSA, T stage, Gleason score, NCCN risk group, duration of ADT and treatment group. Variables with p value <0.2 on UVA were included in the MVA. Univariable logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate factors asociated with PSA control at 4 years. A p value of <0.05 was taken to indicate a statistically significant difference between factors in the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of baseline characteristics

116 and 171 patients were evaluable in the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups respectively. A comparison of baseline patient, disease and treatment characteristics between the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups is shown in Table 1. The median duration of follow up for the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups was 74.1 months and 57 months respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of PSA, Gleason score, T stage and duration of ADT administration. Patients treated with LDR–EBRT were slightly younger at baseline (median age: 63 years versus 65 years, p = 0.02). The LDR–EBRT group contained a greater proportion of patients with high risk PCa (69% (LDR–EBRT) versus 55% (HDR–EBRT, p = 0.02), while more patients in the HDR–EBRT group had intermediate risk disease (40% (HDR–EBRT) versus 24% (LDR–EBRT), p = 0.02).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline patient, disease and treatment characteristics between LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups.

| LDR–EBRT n = 128 |

HDR–EBRT n = 219 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluable patients | 116 | 171 | |

| Missing data | 12 (9.5%) | 48 (22%) | |

| Median follow up (range) | 74.1 months (1.0–187) | 57.0 months (1.8–116) | |

| Median age (range) | 63 years (36–75) | 65 years (49–76) | 0.02 |

| Median PSA value (range) | 10.7 ng/ml (1.6–59) | 10 ng/ml (1.4–131) | Not significant |

| Gleason score (ISUP Grade) | |||

| 6 (1) | 17 (15%) | 20 (12%) | |

| 7 (2 or 3) | 76 (65%) | 121 (71%) | Not significant |

| 8–10 (4 or 5) | 21 (18%) | 29 (17%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | |

| T stage | |||

| T1c-T2c | 50 (43%) | 69 (40%) | |

| T3a-T3b | 56 (48%) | 97 (57%) | Not significant |

| Unknown | 10 (9%) | 5 (3%) | |

| NCCN risk group | |||

| Low | 2 (2%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Intermediate | 28 (24%) | 68 (40%) | |

| High | 80 (69%) | 94 (55%) | 0.02 |

| Unknown | 6 (5%) | 7 (4%) | |

| Hormone duration | |||

| ≤12 months | 74 (64%) | 126 (74%) | |

| >12 months | 7 (6%) | 27 (16%) | 0.06 |

| Unknown | 35 (30%) | 18 (10%) | |

3.2. HDR dosimetry

For HDR boost using 17 Gy in 2 fractions (utilised 2007–2010), median prostate D90 per fraction was 9.46 Gy (range 8.92–10.4 Gy) and median prostate V100 was 98.5% (range 93.5–100%). For HDR boost using 15 Gy in 1 fraction (utilised 2010–2012), median prostate D90 was 17.2 Gy (range 16.1–17.9 Gy) and median prostate V100 was 99.6% (range 94.7–100%).

3.3. Biochemical progression free survival

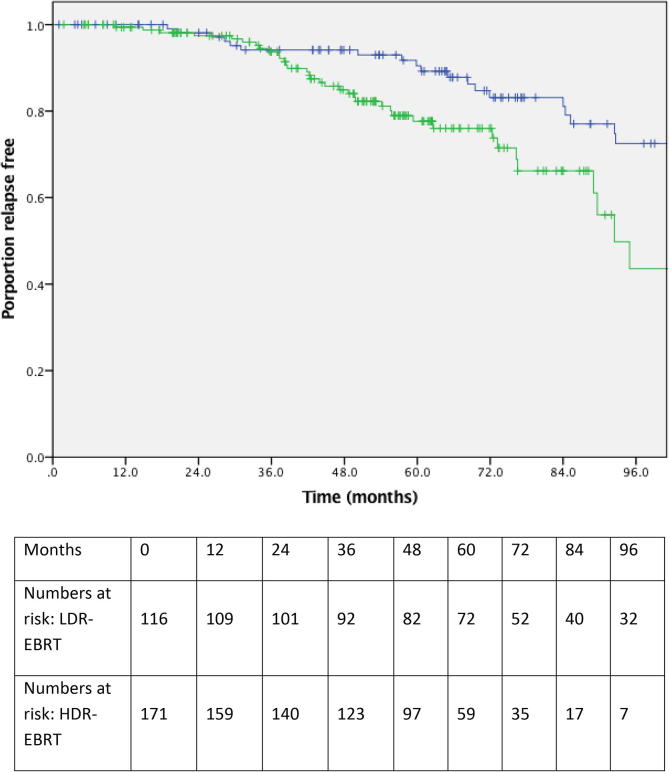

Fig. 1 illustrates bPFS for LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT patients. At 3 and 5 years, bPFS was 94.1% and 90.5% for LDR–EBRT and 93.7% and 77.6% for HDR–EBRT respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in bPFS at 5 years in favour of LDR–EBRT compared with HDR–EBRT (p = 0.01). Table 2 summarise the results of UVA and MVA. Gleason score of ≥8 (ISUP Grade group 4 and 5) and treatment with HDR–EBRT both predicted for biochemical relapse on MVA. The HDR–EBRT group were more than twice as likely to experience biochemical progression compared with the LDR–EBRT group (HR 2.33, 95% CI 1.12–4.07) and patients with Gleason score ≥8 (ISUP Grade group 4 and 5) disease were more than five times more likely to progress compared with those with Gleason score 6 (ISUP Grade group 1) (HR 5.47, 95% CI 1.26–23.64).

Fig. 1.

A Kaplan-Meier plot showing proportions of patients treated with LDR–EBRT (blue curve) and HDR–EBRT (green curve) remaining free of biochemical progression. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable analyses for biochemical progression free survival.

| Variable analysed by UVA | p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Variable analysed by MVA | p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.44 | 0.99 (0.95–1.02) | Gleason (ISUP) score 7 vs 6 (2 or 3 vs 1) ≥8 vs 6 (4 or 5 vs 1) |

0.21 0.02 |

2.48 (0.58–10.46) 5.47 (1.26–23.64) |

| PSA | 0.029 | 1.01 (1–1.03) | Treatment group HDR–EBRT vs LDR–EBRT |

0.01 | 2.33 (1.22–4.42) |

| Gleason (ISUP) | |||||

| 7 vs 6 (2 or 3 vs 1) | 0.31 | 1.84 (0.56–5.98) | |||

| ≥8 vs 6 (4 or 5 vs 1) | 0.04 | 3.7 (1.09–12.56) | |||

| T stage | |||||

| T1/2 vs T3 | 0.50 | 1.2 (0.7–2.06) | |||

| NCCN risk group | |||||

| Intermediate vs low | 0.95 | 0.94 (0.12–7.13) | |||

| High vs low | 0.83 | 1.24 (0.17–9.03) | |||

| Treatment group | |||||

| HDR–EBRT vs LDR–EBRT | 0.004 | 2.3 (1.31–4.09) | |||

| Duration of ADT | |||||

| >12 months vs <12 months | 0.01 | 2.3 (1.2–4.43) | |||

3.4. PSA metrics

The median PSA in unrelapsed patients at the time of last follow up was 0.11 ng/ml (range 0.01–1.97) in the LDR–EBRT group compared with 0.26 ng/ml (0.07–1.6) in HDR–EBRT group. 82 of 116 (70.7%) and 97 of 171 (56.7%) patients in LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups were followed up for a minimum of 4 years respectively. Of these, 52 and 15 patients in the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups had a PSA <0.1 at time of last follow up respectively. On logistic regression analysis, this difference was statistically significant (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.13–0.45, p = <0.001). Age, baseline PSA, Gleason score, T stage, risk group and use of androgen deprivation were all non-significant.

3.5. Toxicity

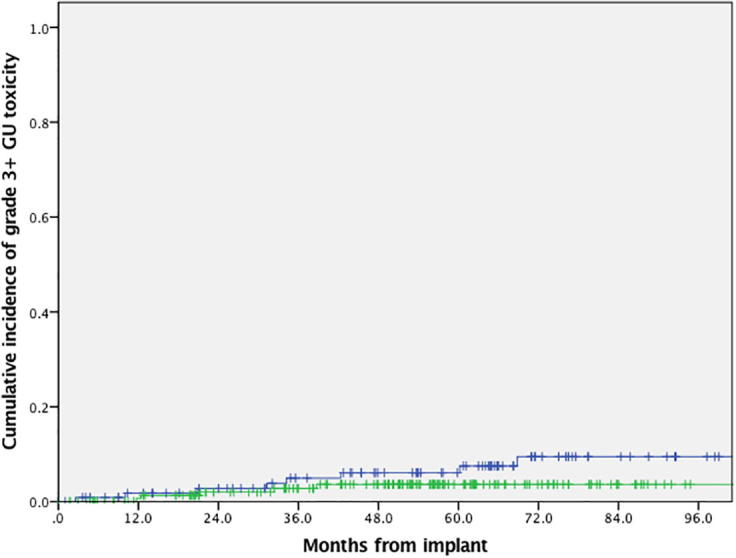

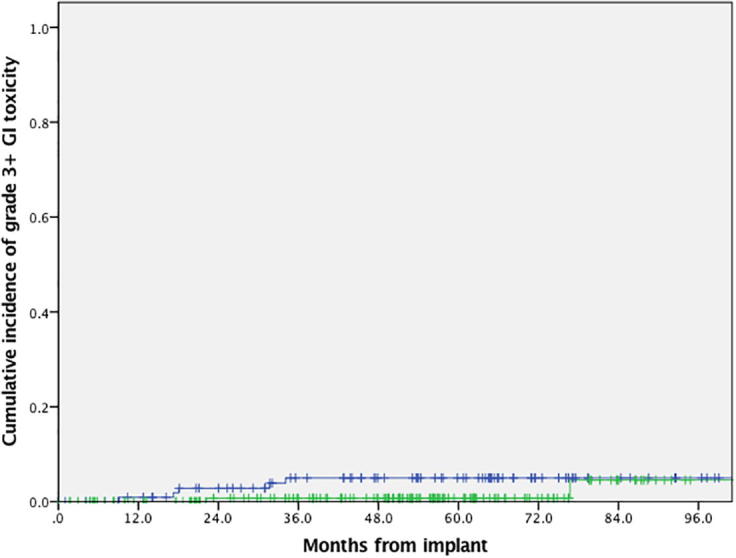

The 5 year cumulative incidence of grade 3 or above GU toxicity was 8% and 4% in the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups respectively, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.17). The 5 year cumulative incidence of grade 3 or above GI toxicity was 5% and 1% for the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups respectively. Again, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.13). Fig. 2, Fig. 3 illustrate cumulative incidence curves for grade 3 or above GU and GI toxicities respectively.

Fig. 2.

Graph showing cumulative incidence of grade ≥3 genitourinary toxicity for patients treated using LDR–EBRT (blue curve) and HDR–EBRT (green curve), p = 0.17. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

Graph showing cumulative incidence of grade ≥3 gastrointestinal toxicity for patients treated using LDR–EBRT (blue curve) and HDR–EBRT (green curve), p = 0.13. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

This retrospective study compared long term bPFS and late GU and GI toxicity outcomes for men with intermediate and high risk PCa treated with LDR–EBRT or HDR–EBRT treated in a single centre. At 5 years, bPFS was 90.5% for the LDR–EBRT group versus 77.6% for the HDR–EBRT group. On MVA, HDR–EBRT was associated with a greater than doubling of the risk of biochemical failure compared to LDR–EBRT. Patients with Gleason score ≥8 (ISUP Grade group 4 or 5) were associated with a greater than five times increased risk of failure. Although cumulative GU and GI grade 3 or above toxicities were greater in the LDR–EBRT group, this difference was not statistically significant.

Both LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT are recommended as treatments for men with intermediate and high risk PCa by American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), American Brachytherapy Society, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and European Association of Urology [24], [25], [26], [27], [28]. No RCTs directly comparing LDR–EBRT with HDR–EBRT have been reported, although one is currently in progress (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03426748). However, there are studies demonstrating benefits for combination LDR and HDR with EBRT compared with EBRT alone including DE-EBRT. A recent analysis of over 120,000 patients from the National Cancer Database concluded that overall survival was similar between patients treated with LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT [29].

Variable dose fractionation schedules are reported by different studies, making direct comparison of our study with published data difficult. Several studies included treated patients with whole pelvis radiotherapy, unlike our study. In addition, there are often differences in the baseline characteristics between studies, such as the proportions of patients with intermediate and high risk disease. Nevertheless, our outcomes for the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT groups are not dissimilar to previously published studies. A comparison is shown in Table 3. The ASCENDE-RT study of LDR–EBRT compared with DE-EBRT reported 5 year bPFS of 89% for patients treated with LDR–EBRT [12]. A phase II study by Lawton et al. reported 8 year bPFS of 82% and in retrospective cohorts 5 year bPFS ranged from 89% to 94.1% at 5 years [9], [15], [18]. The RCT of HDR–EBRT by Hoskin et al. reported 5 year bPFS of 75% [8]. At 5 years, Helou et al. reported bPFS was 97.4% and 92.7% in sequential phase II studies of a single 15 Gy HDR boost and two 10 Gy fraction boosts respectively [7]. Retrospective series reported bPFS at 5 years ranging from 82.5% to 97.7% [6], [17], [19]. It should be noted that those studies with bPFS at 5 years for HDR–EBRT in excess of 90% had more patients with intermediate risk disease and fewer with high risk disease [6], [7], [19].

Table 3.

Comparison of the results of our study with selected previously published studies of LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT.

| Author | Year | Type of study | Treatment | Number of patients | NCCN risk category | Numbers receiving whole pelvis RT | Biochemical PFS | Late GU toxicity | Late GI toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slevin, Rodda et al. | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | LDR–EBRT versus HDR–EBRT | LDR–EBRT: 116 HDR–EBRT: 171 |

LDR–EBRT: Low 2 (2%) Intermediate (Int.) 28 (24%) High 80 (69%) Unknown 6 (5%) HDR–EBRT: Low 2 (1%) Int. 68 (40%) High 94 (55%) Unknown 7 (4%) |

None | LDR–EBRT: 90.5% at 5 years HDR–EBRT: 77.6% at 5 years |

LDR–EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 8% at 5 years HDR–EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 4% at 5 years |

LDR–EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 5% at 5 years HDR–EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 1% at 5 years |

| Morris et al. [12] | 2017 | RCT | LDR–EBRT versus DE-EBRT | LDR–EBRT: 198 DE-EBRT: 200 |

LDR–EBRT: Int. 59 (29.8%) High 139 (70.2%) DE-EBRT: Int. 63 (31.5%) High 137 (68.5%) |

All patients | LDR–EBRT: 89% at 5 years, 83% at 9 years DE-EBRT: 84% at 5 years, 62% at 9 years |

LDR–EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 18.4% at 5 years DE-EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 5.2% at 5 years |

LDR–EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 8.1% at 5 years DE-EBRT: Cumulative ≥grade 3 3.2% at 5 years |

| Lawton et al. [9] | 2012 | Phase II trial | LDR–EBRT | 138 | Int. 138 (100%) | None | 82% at 8 years | Estimates of ≥grade 3 15% at 8 years | Estimates of ≥grade 3 15% at 8 years |

| Shilkrut et al. [15] | 2013 | Retrospective cohort | LDR–EBRT versus DE-EBRT | LDR–EBRT: 448 DE-EBRT: 510 |

LDR–EBRT: High 448 (100%) DE-EBRT: High 510 (100%) |

All patients | LDR–EBRT: 89% at 5 years, 87% at 8 years DE-EBRT: 73% at 5 years, 60% at 8 years |

Toxicity data not presented | Toxicity data not presented |

| Abughrahib et al. [18] | 2017 | Retrospective cohort | LDR–EBRT versus EBRT | LDRT-EBRT: 191 EBRT: 388 |

LDR–EBRT: Int. 191 (100%) EBRT: Int. 388 (100%) |

None | LDR–EBRT: 94.1% at 5 years, 91.7% at 10 years EBRT: 89.2% at 5 years, 75.4% at 10 years |

LDR–EBRT: Cumulative incidence of ≥grade 3 3.6% at 6 years, 7.5% at 10 years EBRT: Cumulative incidence of ≥grade 3 1.4% at 6 years, 1.4% at 10 years |

LDR–EBRT: Cumulative incidence of ≥grade 2 31.2% at 6 years, 35.5% at 10 years EBRT: Cumulative incidence of ≥grade 2 33.1% at 6 years, 33.1% at 10 years |

| Hoskin et al. [8] | 2012 | RCT | HDR–EBRT versus EBRT | HDR–EBRT: 110 EBRT: 106 |

HDR–EBRT: Low 2 (2%) Int. 48 (44%) High 60 (54%) EBRT: Low 7 (7%) Int. 43 (40%) High 56 (53%) |

None | HDR–EBRT: 75% at 5 years, 46% at 10 years EBRT: 61% at 5 years, 39% at 10 years |

HDR–EBRT: Incidence of ≥grade 3 26% at 5 years, 31% at 7 years EBRT: Incidence of ≥grade 3 26% at 5 years, 30% at 7 years |

HDR–EBRT: Incidence of ≥grade 3 7% at 5 years, 7% at 7 years EBRT: Incidence of ≥grade 3 6% at 5 years, 6% at 7 years |

| Helou et al. [7] | 2015 | Sequential phase II studies | Single 15 Gy versus two 10 Gy fraction boosts HDR–EBRT | Single fraction boost HDR–EBRT: 123 Two fraction boost HDR–EBRT: 60 |

Single fraction boost HDR–EBRT: Int. 123 (100%) Two fraction boost HDR–EBRT: Int. 60 (100%) |

None | Single fraction boost HDR–EBRT: 97.4% at 5 years, 89.1% at 7 years Two fraction boost HDR–EBRT: 92.7% at 5 years, 92.7% at 7 years |

Toxicity data for single 15 Gy arm presented by Shahid et al. [3] | Toxicity data for single 15 Gy arm presented by Shahid et al. [3] |

| Shahid et al. [3] | 2017 | Phase II study | HDR–EBRT | 125 | Int. 125 (100%) |

None | Efficacy data presented by Helou et al. [7] | Incidence of ≥grade 3 4% | Incidence of ≥grade 3 0% |

| Vigneault et al. [19] | 2017 | Retrospective cohort | Various dose fractionation schedules of HDR boost and EBRT | 832 | Low 57 (7%) Int. 640 (77%) High 135 (16%) |

Proportion not stated | 94.6% at 5 years, 92.5% at 10 years | ≥grade 3 1.7% for schedules with BED 250–260 Gy and 4.9% for schedules with BED > 260 Gy | ≥grade 3 0% |

| Zwahlen et al. [17] | 2010 | Retrospective cohort | HDR–EBRT versus EBRT | HDR–EBRT: 196 EBRT: 391 |

HDR–EBRT: Low 9 (5%) Int. 89 (46%) High 98 (50%) EBRT: Low 82 (21%) Int. 157 (40%) High 152 (39%) |

4 (<1%) | HDR–EBRT: 82.5% at 5 years, 80.3% at 7 years EBRT: 81.3% at 5 years, 71% at 7 years |

HDR–EBRT: ≥grade 3 7.1% EBRT: ≥grade 3 not reported |

HDR–EBRT: ≥grade 3 0% EBRT: ≥grade 3 0% |

| Deutsch et al. [6] | 2008 | Retrospective cohort | HDR–EBRT versus EBRT | HDR–EBRT: 160 LDR–EBRT: 470 |

HDR–EBRT: Low 22 (14%) Int. 114 (71%) High 24 (15%) EBRT: Low 97 (21%) Int. 190 (40%) High 183 (39%) |

None | HDR–EBRT: 97.7% at 5 years EBRT: 82% at 5 years |

Toxicity data not presented | Toxicity data not presented |

Nadir PSA is an important predictor of longterm bPFS in men treated with prostate BT and a lower PSA nadir is associated with a better outcome [30]. Radiobiological models suggested that LDR and HDR should provide similar tumour control, with a potential advantage for the high dose per fraction used with HDR if PCa does indeed have a low alpha/beta ratio [2], [21], [31]. However, 44.8% of patients treated with LDR–EBRT in our study achieved an ablative PSA <0.1 compared with 8.7% treated with HDR–EBRT, despite having a greater proportion of patients with high risk disease. It has been shown that increasing biological effective dose (BED) is associated with improved disease control. However, a different BED equation is used for LDR calculations and there are difficulties in comparing BEDs between LDR and other treatments [32], [33]. The dose rate and fractionation and intrinsic radiobiological properties of LDR differ significantly to HDR [34]. Given the differences in nadir PSA we have observed, it is possible that the improved outcomes demonstrated in our study for patients treated with LDR–EBRT are related to radiobiological advantages compared with HDR–EBRT.

There are limitations to comparing our toxicity data with published studies because of its retrospective nature and differences in scoring systems, methods and timings of analyses, frequency of follow up and dose fractionation schedules of LDR–EBRT and HDR–HDR–EBRT [8]. We have also only reported ≥grade 3 toxicities and have not collected patient reported outcomes, which more accurately measure adverse events [35]. A comparison of our results with previously published studies is shown in Table 3. Our study found lower cumulative 5 year ≥grade 3 GU and GI toxicities for LDR–EBRT than in the ASCENDE-RT trial and the study by Lawton et al. [9], [20]. Cumulative ≥grade 3 events were 18.4% and 8.1% for GU and GI toxicities at 5 years in the ASCENDE-RT study and 15% at 8 years in the Lawton et al. study compared with 8% and 5% respectively in our study. The differences observed compared to our study may be because of stricter patient follow up protocols used within these trials and the use of whole pelvis treatments in the ASCENDE-RT study. In addition, the ASCENDE-RT study used a BT boost of 115 Gy compared with 110 Gy in our cohort [12]. Our study had low rates of significant late toxicity in the HDR–EBRT group that compare favourably with published studies. We found cumulative ≥grade 3 GU and GI toxicities of 4% and 1% respectively. Hoskin et al. reported ≥grade 3 GU and GI toxicity rates at 5 years of 26% and 7% respectively [8]. Shahid et al. reported incidence of ≥grade 3 GU and GI toxicities of 4% and 0% respectively in a phase II study of HDR–EBRT [3].

Strengths of this study include the relatively large numbers of patients eligible for analysis with both biochemical control and toxicity endpoints reported. Limitations of this study that could have influenced the differences in outcomes include its non-randomised, retrospective design and non-overlapping treatment periods for LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT. The non-overlapping time periods could have introduced historical bias because of changes in diagnostic imaging/staging, use of active surveillance protocols and changes in treatment delivery. Different dose fractionation schedules were used in the LDR–EBRT and HDR–EBRT cohorts. In addition, post-implant PSA data was missing from some patients leading to their exclusion from the analysis with more excluded patients in the HDR–EBRT cohort (48 versus 12). There were also some differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. The LDR–EBRT group had a slightly younger median age, but they also had a greater proportion of high risk PCa. More patients were evaluated in the HDR–EBRT group (171 versus 116), which could have introduced selection bias relating to treatment eligibility criteria. A further limitation was that numbers of patients at risk evaluable at each timepoint differed between the two cohorts.

For patients treated in the initial period after introduction of HDR–EBRT there may have been a learning curve which could detrimentally influenced outcomes. The mean prostate V100 in the HDR–EBRT increased from 96.6% (standard deviation 1.6%) in 2007 to 99.6% (standard deviation 0.7%) in 2012, demonstrating a dosimetric improvement over this period. This can be explained by technique experience, introduction of a PTV and improvements in the dose optimisation class solution/algorithm. Hoskin et al. reported that D90 and V100 were important dose predicators of biochemical control of prostate cancer in their randomised control trial cohort [36]. Current practice at our centre has evolved further adopting in 2013 the GEC-ESTRO recommendations that VPTV100 should be at least 95% of the planning aim dose [4]. Future work will further evaluate the impact of this learning curve and technique evolution.

In summary, we have observed a statistically significant difference in bPFS in favour of LDR–EBRT compared with HDR–EBRT. Cumulative rates of grade 3 or above GU and GI toxicity were greater for LDR–EBRT, although these differences were not statistically significant. Well conducted randomised trials directly comparing LDR–EBRT with HDR–EBRT are needed to determine whether true differences in bPFS exist.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective study suggests that LDR–EBRT may provide more effective PSA control at 5 years compared with HDR–EBRT. Direct comparison of these treatments through randomised trials are recommended to investigate this hypothesis further.

6. Sources of support

This work was undertaken in Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust which receives funding from NHS England. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of NHS England. F Slevin reports grants from Cancer Research UK Centres Network Accelerator Award Grant (A21993) to the Advanced Radiotherapy Technologies Network (ART-NET) consortium during the conduct of this study. L Murray is a University Clinical Academic Fellow funded by Yorkshire Cancer Research (award number L389LM). AM Henry reports grants from Cancer Research UK (108036) during the conduct of this study; grants from NIHR, United Kingdom (111218), grants from MRC, United Kingdom (107154) and grants from Sir John Fisher Foundation, United Kingdom (charity, no grant number) outside the submitted work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Leeds Cares (the official charity partner of Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust) for their payment of the open access publication charge for this article. No writing assistance used.

Contributor Information

Finbar Slevin, Email: finbarslevin@nhs.net.

Sree Lakshmi Rodda, Email: sreerodda@nhs.net.

Peter Bownes, Email: p.bownes@nhs.net.

Louise Murray, Email: louise.murray8@nhs.net.

David Bottomley, Email: davidm.bottomley@nhs.net.

Clare Wilkinson, Email: clare.wilkinson4@nhs.net.

Ese Adiotomre, Email: ese.adiotomre@nhs.net.

Bashar Al-Qaisieh, Email: bashar.al-qaisieh@nhs.net.

Emma Dugdale, Email: emma.dugdale@nhs.net.

Oliver Hulson, Email: oliverhulson@nhs.net.

Joshua Mason, Email: joshua.mason@nhs.net.

Jonathan Smith, Email: jonathan.smith18@nhs.net.

Ann M Henry, Email: A.Henry@leeds.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Bannuru R.R., Dvorak T., Obadan N. Comparative evaluation of radiation treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):171–178. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton G.C., Hoskin P.J. Brachytherapy: current status and future strategies—can high dose rate replace low dose rate and external beam radiotherapy? Clin Oncol. 2013;25(8):474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahid N., Loblaw A., Chung H.T. Long-term toxicity and health-related quality of life after single-fraction high dose rate brachytherapy boost and hypofractionated external beam radiotherapy for intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Clin Oncol. 2017;29(7):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2017.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoskin P.J., Colombo A., Henry A. GEC/ESTRO recommendations on high dose rate afterloading brachytherapy for localised prostate cancer: an update. Radiother Oncol. 2013;107(3):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morton GC, Original paper<br> High-dose-rate brachytherapy boost for prostate cancer: rationale and technique. 2014. 6(3): 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Deutsch I., Zelefsky M.J., Zhang Z. Comparison of PSA relapse-free survival in patients treated with ultra-high-dose IMRT versus combination HDR brachytherapy and IMRT. Brachytherapy. 2010;9(4):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2010.02.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helou J., D’Alimonte L., Loblaw A. High dose-rate brachytherapy boost for intermediate risk prostate cancer: long-term outcomes of two different treatment schedules and early biochemical predictors of success. Radiother Oncol. 2015;115(1):84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoskin P.J., Rojas A.M., Bownes P.J. Randomised trial of external beam radiotherapy alone or combined with high-dose-rate brachytherapy boost for localised prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2012;103(2):217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawton C.A., Yan Y., Lee W.R. Long-term results of an RTOG phase II trial (00-19) of external-beam radiation therapy combined with permanent source brachytherapy for intermediate-risk clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(5):e795–e801. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merrick G.S., Butler W.M., Wallner K.E. Impact of supplemental external beam radiotherapy and/or androgen deprivation therapy on biochemical outcome after permanent prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(1):32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrick G.S., Wallner K.E., Butler W.M. 20 Gy versus 44 Gy of supplemental external beam radiotherapy with palladium-103 for patients with greater risk disease: results of a prospective randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(3):e449–e455. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris W.J., Tyldesley S., Rodda S. Androgen suppression combined with elective nodal and dose escalated radiation therapy (the ASCENDE-RT Trial): An analysis of survival endpoints for a randomized trial comparing a low-dose-rate brachytherapy boost to a dose-escalated external beam boost for high- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98(2):275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morton G., Loblaw A., Cheung P. Is single fraction 15 Gy the preferred high dose-rate brachytherapy boost dose for prostate cancer? Radiother Oncol. 2011;100(3):463–467. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pieters B.R., van de Kamer J.B., van Herten Y.R.J. Comparison of biologically equivalent dose–volume parameters for the treatment of prostate cancer with concomitant boost IMRT versus IMRT combined with brachytherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2008;88(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shilkrut M, Merrick GS, McLaughlin PW, et al., The addition of low-dose-rate brachytherapy and androgen-deprivation therapy decreases biochemical failure and prostate cancer death compared with dose-escalated external-beam radiation therapy for high-risk prostate cancer. 2013. 119(3): 681–690. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Smith G.D., Pickles T., Crook J. Brachytherapy improves biochemical failure-free survival in low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer compared with conventionally fractionated external beam radiation therapy: a propensity score matched analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(3):505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwahlen D.R., Andrianopoulos N., Matheson B. High-dose-rate brachytherapy in combination with conformal external beam radiotherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2010;9(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abugharib A.E., Dess R.T., Soni P.D. External beam radiation therapy with or without low-dose-rate brachytherapy: analysis of favorable and unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients. Brachytherapy. 2017;16(4):782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vigneault E., Mbodji K., Magnan S. High-dose-rate brachytherapy boost for prostate cancer treatment: different combinations of hypofractionated regimens and clinical outcomes. Radiother Oncol. 2017;124(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodda S., Tyldesley S., Morris W.J. ASCENDE-RT: an analysis of treatment-related morbidity for a randomized trial comparing a low-dose-rate brachytherapy boost with a dose-escalated external beam boost for high- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98(2):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogelius I.R., Bentzen S.M. Meta-analysis of the alpha/beta ratio for prostate cancer in the presence of an overall time factor bad news, good news, or no news? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(1):89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henry A.M., Al-Qaisieh B., Gould K. Outcomes following iodine-125 monotherapy for localized prostate cancer: the results of Leeds 10-year single-center brachytherapy experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joseph J, Al-Qaisieh B, Ash D, et al., Prostate-specific antigen relapse-free survival in patients with localized prostate cancer treated by brachytherapy. 2004. 94(9): 1235–1238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bekelman J.E., Rumble R.B., Chen R.C. Clinically localized prostate cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline endorsement of an American Urological Association/American Society for Radiation Oncology/Society of Urologic Oncology Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00606. Jco1800606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Association of Urology. Prostate cancer. 2019; Available from: <https://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/#note_484>. [Accessed: 25/06/2019].

- 26.Merrick GS, Zelefsky MJ, Sylvester J, et al. American Brachytherapy Society Prostate Low-Dose Rate Task Group. 2010; Available from: https://www.americanbrachytherapy.org/ABS/document-server/?cfp=ABS/assets/File/public/consensus-statements/prostate_low-doseratetaskgroup.pdf. [Accessed: 19/07/2019]

- 27.Hsu I-C, Yamada Y, Vigneault E, et al. American Brachytherapy Society Prostate High-Dose Rate Task Group. 2008; Available from: https://www.americanbrachytherapy.org/ABS/document-server/?cfp=ABS/assets/file/public/consensus-statements/HDRTaskGroup.pdf. [Accessed: 19/07/2019]

- 28.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management. 2019; Available from: <https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG131>. [Accessed: 25/06/2019] [PubMed]

- 29.King M.T., Yang D.D., Muralidhar V. A comparative analysis of overall survival between high-dose-rate and low-dose-rate brachytherapy boosts for unfavorable-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2019;18(2):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo A.C., Morris W.J., Lapointe V. Prostate-specific antigen at 4 to 5 years after low-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy is a strong predictor of disease-free survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.King C.R. LDR vs. HDR brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer: the view from radiobiological models. Brachytherapy. 2002;1(4):219–226. doi: 10.1016/S1538-4721(02)00101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stock R.G., Stone N.N., Cesaretti J.A. Biologically effective dose values for prostate brachytherapy: effects on PSA failure and posttreatment biopsy results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(2):527–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaorsky N.G., Palmer J.D., Hurwitz M.D. What is the ideal radiotherapy dose to treat prostate cancer? A meta-analysis of biologically equivalent dose escalation. Radiother Oncol. 2015;115(3):295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang R., Zhao N., Liao A. Dosimetric and radiobiological comparison of volumetric modulated arc therapy, high-dose rate brachytherapy, and low-dose rate permanent seeds implant for localized prostate cancer. Med Dosim. 2016;41(3):236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.meddos.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rammant E., Ost P., Swimberghe M. Patient- versus physician-reported outcomes in prostate cancer patients receiving hypofractionated radiotherapy within a randomized controlled trial. Strahlenther Onkol. 2019;195(5):393–401. doi: 10.1007/s00066-018-1395-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoskin P.J., Rojas A.M., Ostler P.J. Dosimetric predictors of biochemical control of prostate cancer in patients randomised to external beam radiotherapy with a boost of high dose rate brachytherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110(1):110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]