Abstract

Salvia miltiorrhiza is one of the most widely used traditional Chinese medicinal plants because of its excellent performance in treating heart diseases. Tanshinones and phenolic acids are two important classes of effective metabolites, and their biosynthesis has attracted widespread interest. Here, we functionally characterized SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2, two GRAS family transcription factors from S. miltiorrhiza. SmGRAS1/2 were highly expressed in the root periderm, where tanshinones mainly accumulated in S. miltiorrhiza. Overexpression of SmGRAS1/2 upregulated tanshinones accumulation and downregulated GA, phenolic acids contents, and root biomass. However, antisense expression of SmGRAS1/2 reduced the tanshinones accumulation and increased the GA, phenolic acids contents, and root biomass. The expression patterns of biosynthesis genes were consistent with the changes in compounds accumulation. GA treatment increased tanshinones, phenolic acids, and GA contents in the overexpression lines, and restored the root growth inhibited by overexpressing SmGRAS1/2. Subsequently, yeast one-hybrid, dual-luciferase, and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) showed SmGRAS1 promoted tanshinones biosynthesis by directly binding to the GARE motif in the SmKSL1 promoter and activating its expression. Yeast two-hybrid assays showed SmGRAS1 interacted physically with SmGRAS2. Taken together, the results revealed that SmGRAS1/2 acted as repressors in root growth and phenolic acids biosynthesis but as positive regulators in tanshinones biosynthesis. Overall, our findings revealed the potential value of SmGRAS1/2 in genetically engineering changes in secondary metabolism.

Keywords: Salvia miltiorrhiza, SmGRAS1/2, GA, tanshinines, phenolic acids, biosynthesis

Introduction

Danshen, the dried roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, is a traditional Chinese medicine in treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (Dong et al., 2011). In addition, it also has many pharmaceutical activities, including anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antiancer properties (Jiang et al., 2013). In China, numerous pharmaceutical dosage forms of Danshen are commercially available, including tablets, capsules, oral liquids, injectables, granules, and dripping pills. As a model medicinal plant with great economic and medicinal value, there has been many extensive interests in improving bioactive ingredients (Xu et al., 2015a; Xu et al., 2015b). The bioactive ingredients of S. miltiorrhiza fall into two main groups: hydrophilic components (phenolic acids), such as salvianolic acid B and rosmarinic acid (RA), and lipophilic components (tanshinones), such as dihydrotanshinone I (DT-I), cryptotanshinone (CT), tanshinone I (T-I), and tanshinone IIA (T-IIA) (Huang et al., 2019). The contents of tanshinones and phenolic acids are the major quality markers of S. miltiorrhiza medicinal materials, according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (The State Pharmacopoeia Commission of China, 2015). As one kind of diterpenoids, tanshinones are synthesized through mevalonic acid and 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate pathways (Kai et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2015), which included AACT, HMGR, DXS, DXR, CMK, GGPPS, KSL, and CYP76AH biosynthetic genes (Ma et al., 2012). Phenolic acids are produced in phenylpropanoid and tyrosine-derived pathways (Pei et al., 2018), which included C4H, 4CL, TAT, and CYP98A14 biosynthetic genes (Xu et al., 2016). Many reports have focused on these key synthase genes, which could improve the accumulation of active components. However, relatively less is known about the regulatory mechanisms of transcriptional factors in the biosynthesis of tanshinones and phenolic acids in S. miltiorrhiza.

GA is an important phytohormone that controls many aspects of plant growth and development through GA signaling pathway (Sun, 2011). It also has been reported to regulate root growth and secondary metabolism (Du et al., 2015; Davière and Achard, 2016). GA could promote root growth of Arabidopsis via directly reducing the level of flavonols (Tan et al., 2019). Moreover, there is an interaction between energy metabolism and the GA-mediated control of growth that coordinates cell wall extension, lipid metabolism, and secondary metabolism in Arabidopsis (Ribeiro et al., 2012). The metabolic pathways of GA biosynthesis and degradation, as well as GA signaling pathways, have been reported (Sun, 2011; Du et al., 2015). As a group of diterpenoids, GA shares the universal precursor geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) with other diterpenoids, such as tanshinones (Ma et al., 2012; Du et al., 2015). The biosynthesis of tanshinones from GGPP involves CPS1/2, KSL1, CYP76AH1/3, and other unknown genes, while the biosynthesis of GA from GGPP involves CPS5, KS, KAO, GA20ox, GA3ox, and GA2ox genes (Ma et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2015; Su et al., 2016). Notably, GA treatment could increase tanshinones accumulation in the wild-type hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza (Liang et al., 2013; Bai et al., 2017). Thereby, there may exists a tradeoff between GA and tanshinones biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza.

GRAS family transcription factors (TFs), the key regulators of GA signaling, integrated multiple signaling pathways (Hakoshima, 2018). Members of GRAS gene family have been identified in many plants, including Arabidopsis, rice, tomato, and grapevine (Tian et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2015; Grimplet et al., 2016). Based on amino acid sequences, the GRAS family was divided into 13 distinct subfamilies: DELLA, SCR, SHR, PAT1, SCL3, SCL4/7, LISCL, SCL28, LAS, HAM, DLT, OS4, and OS19 (Huang et al., 2015). Previous studies have reported that GRAS proteins play diverse roles in root development, GA signal transduction, light signaling, and biotic and abiotic stress responses (Livne et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015a; Xu et al., 2015b; Heck et al., 2016). For instance, SCR and SHR formed a complex in order to participate in regulating root-related developmental processes in Arabidopsis (Cui et al., 2007; Lucas et al., 2011). The PAT1 subfamily had been shown to mediate phytochrome and defence signaling pathways (Hakoshima, 2018). SCL3 functioned as a repressor of DELLA, which could positively regulate the GA signaling pathway and control GA homeostasis in Arabidopsis root development (Zhang et al., 2011). Therefore, we speculated that SmGRAS could regulate the root development through controlling the GA homeostasis in S. miltiorrhiza.

Since tanshinones are mainly concentrated in the periderm of S. miltiorrhiza roots and induced by GA treatment (Xu et al., 2015a; Xu et al., 2015b; Bai et al., 2017), we speculated that the GA response factors SmGRASs might participate in the tanshinones biosynthesis in S. miltiorrhiza roots. Although five GRAS family genes have been identified in S. miltiorrhiza (Bai et al., 2017), how do the SmGRASs participate in root growth and diterpenoid metabolic flux remains unknown. In this study, we characterized and analyzed the functions of two GRAS genes, SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 in S. miltiorrhiza. Overexpression (OE) of SmGRAS1/2 could inhibit root growth, increase the accumulation of tanshinones, and reduce the contents of GA and phenolic acids. However, all the patterns of the contents mentioned above had the opposite changes after GA treatment in the OE lines, except the tanshinones. Subsequently, yeast one-hybrid (Y1H), dual-luciferase (Dual-LUC), and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) confirmed that SmGRAS1 could directly bind to the GARE motif in the promoter of SmKSL1 to induce its expression. Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) further illustrated SmGRAS1 interacted with SmGRAS2. Finally, the molecular mechanisms of the regulation of GA-mediated root growth and secondary metabolite biosynthesis by SmGRAS1/2 were analyzed and discussed. Functional analysis of SmGRAS1/2 on regulating the root growth and diterpenoid metabolic flux increases our understanding of the molecular basis of the tradeoff between GA and tanshinones biosynthesis, providing a framework for metabolic engineering in S. miltiorrhiza.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, and GA Treatment

The S. miltiorrhiza hairy roots were derived from sterile plantlets infected with Agrobacterium rhizogenes bacterium (ATCC15834), as previously reported (Ru et al., 2016). The hairy roots (0.3 g fresh weight) were cultured in 50 ml of liquid 6,7-V medium on an orbital shaker and sub-cultured every 30 days. Nicotiana benthamiana was grown in a greenhouse (16 h: 8 h, light: dark) at 25°C for 30 days and used for the subcellular localization experiments.

A GA3 (Sigma, USA) stock solution was added to the 21-day-old hairy roots to obtain a final concentration of 100 μM. The hairy roots were treated for 2 h, 24 h, or 6 days. Hairy roots without GA3 treatment were used as controls. The controls and treated roots were collected at the same time and used for real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. All treatments were performed in three independent biological replicates.

To analyze the tissue-specific SmGRAS1/2 genes expression levels, leaf, stem, flower, bud flower, phloem, xylem, and periderm tissue were collected from the 2-year-old S. miltiorrhiza.

Bioinformatics Analysis of SmGRAS1/2

SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 protein sequences from S. miltiorrhiza and multiple sequence alignments of GRAS protein sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana (http://www.arabidopsis.org) were performed using the ClustalX program. A phylogenetic tree based on the alignment was constructed with MEGA6 by the neighbor-joining method with the bootstrap test (n = 500 replications).

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR Assays

Total RNA was extracted by using the RNAprep pure plant kit (TIANGEN, China), and then reverse transcribed to cDNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, China). qRT-PCR was performed on a real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad CFX96, USA) using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II Kit (Takara, China). The SmActin gene was used as the endogenous control (Yang et al., 2010). The relative expression levels of the genes were calculated by the 2−ΔΔct method. All the primers used for the qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Table S1 . The data were obtained from three independent biological replicates and three technical replicates.

HPLC Analysis of Tanshinones and Phenolic Acids Contents

The contents of tanshinones and phenolic acids in the S. miltiorrhiza roots were determined by HPLC, according to previous method (Liu et al., 2016). In brief, 0.04 g powder of dried hairy roots was extracted by soaking the sample overnight in 8 ml of 70% methanol and then sonicating the sample for 45 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2-μm filter and analyzed by HPLC.

Subcellular Localization

The full-length coding regions of SmGRAS1/2 were fused with green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the pA7-GFP vector. The pA7-SmGRAS1/2-GFP and pA7-GFP plasmids were transiently transformed into onion epidermis with gene gun (Bio-Rad, USA). After 1 day of incubation, the onion epidermis was stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (Solarbio, China) for 20 min, washed twice with PBS buffer (pH 7.2), and later observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon A1R, Japan).

The pA70390-SmGRAS1/2-GFP and pA70390-GFP plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium strain GV3101. The GV3101 suspension cultures were infiltrated into leaves of 4-week-old N. benthamiana, following the previously described method (Bai et al., 2018). After 2 days of co-culture, the protoplasts were prepared as previously described (Li, 2011). The protoplasts were stained with DAPI for 15 min and later observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope. The primers used for the subcellular localization analysis are listed in Table S1 .

Analysis of Transcriptional Activity

The pDEST-GBKT7-SmGRAS1/2 and pDEST-GBKT7 plasmids were transformed into the yeast strain AH109. The pGBKT7-53 + pGADT7-T plasmid was constructed as a positive control. The transformed AH109 were first screened on synthetic dropout (SD) medium lacking tryptophan (SD/-Trp) and then selected on SD medium without tryptophan, histidine and adenine (SD/-Trp/-His/-Ade). Transcriptional activity was evaluated according to the growth status of the yeast.

Plasmid Construction and Genetic Transformation

The full-length sequences of SmGRAS1/2 were amplified and cloned into the restriction sites NocI and SpeI of the pCAMBIA1304 binary vector in sense and antisense orientations under the control of the CaMV35S promoter. The positive clones were confirmed by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. Afterwards, the plasmids were transformed into ATCC15834. The transformants were screened with a combination of cefotaxime (Sigma, USA) and hygromycin B (MP Bio, USA). Genomic DNA was isolated from hairy roots by using the cetyl trimethylammonium bromide method. Four primer pairs, rolB, rolC, hptII, 35S forward primer (35S F), and GRAS1/2 reverse primer (GRAS1/2 R), were designed for the PCR identification and the positive transgenic lines screening. The positive transgenic lines were used for the qRT-PCR and HPLC analyses. All the primers used for the expression vector construction and the PCR identification of transgenic lines are listed in Table S1 .

Determination of GA3 Concentrations

The 21-day-old transgenic hairy roots and control roots (ATCC) were treated with 100 μM GA3 for 6 days. Each line (ATCC, ATCC-GA, G1O7, G1O7-GA, G2O17, and G2O17-GA) was collected in three biological replicates and used for the analysis GA3 concentrations, which were measured by HPLC as previously described (Mornya and Cheng, 2018).

Y1H Verification

The coding sequences of full-length SmGRAS1/2 were inserted into the pGADT7 vector. The primers for the pGADT7-SmGRAS1/2 vector are listed in Table S1 . Then, the 649-bp SmKSL1 promoter sequences were cloned into the pBait-AbAi vector. The primers for the bait vectors (pBait-AbAi-SmKSL1-649) are listed in Table S1 . Aureobasidin A (AbA) suppressed the basal expression of the Y1H-pAbAi-SmKSL1-649 (PYK649) yeast strain (Bai et al., 2018). pGADT7-SmGRAS1/2 was verified by interactions with PYK649 yeast strains, which recombined the SmKSL1 promoter in SD/-Leu/AbA. The following step and α-X-gal staining were described in the yeast protocol handbook (Clontech, PT3024-1).

Protein Extraction and Western Blot

The full-length coding sequences of SmGRAS1 were cloned into the pMAL-2A vector (Novagen) by using specific primers ( Table S1). The plasmids were transformed and expressed in Escherichia coli cells (Rosetta strain). Protein induction and purification were performed as previously described (Bai et al., 2018). The SDS-PAGE analyses of MBP (malE) and SmGRAS1-MBP purified proteins were conducted and showed major bands with an approximate molecular mass of 96.4 kDa ( Figure S6 ). Subsequently, the purified proteins were verified using western blot as previously described (Ru et al., 2017).

Dual-Luciferase Assay

The 649-bp promoter of SmKSL1 was cloned and inserted into pGREEN. The vector pCAMBIA1304-SmGRAS1 was transferred into Agrobacterium strain GV3101. pCAMBIA1304 empty vector was used as a negative control and the 35S promoter-driven Renilla luciferase as an internal control. The two GV3101 strains were co-infiltrated into tobacco leaves. Infiltrated leaves were incubated in darkness for 8 h and then in light for 40 h. Three biological replicates of each sample were assayed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, USA).

EMSA Analysis

The oligonucleotide probes were synthesized (listed in Table S1 ) and annealed at 95°C for 5 min, followed by cooling to room temperature. EMSA was performed using the EMSA kit (Invitrogen, USA), and a protein-free sample was used as the blank control. The mass ratios of the probe and protein were 1:5/15/50 in each reaction mixture (10 μl). The gels were imaged on a 490 nm SYBR photographic filter using a ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad, USA).

Y2H Assays

The full-length coding sequences of SmGRAS1 were inserted into the pGADT7 vector and SmGRAS2 were inserted into the pGBKT7 vector by using specific primers ( Table S1 ). The SmGRAS1-AD and SmGRAS2-BD plasmids were co-transformed into strain Y2H. The pGBKT7 and pGADT7 vectors were co-transformed to serve as a negative control. After selection on SD/-Leu/-Trp, single transformant colonies were screened for growth on a SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp with AbA and α-X-gal. Interactions were observed after 3-day incubation at 29°C.

Results

Characterization of SmGRAS1/2

To study the functions of SmGRAS genes, their coding regions were amplified to generate transgenic hairy roots. We first obtained two SmGRAS genes (SmGRAS1/2) transgenic hairy roots. The ORFs of SmGRAS1 (GenBank accession number KY435886) and SmGRAS2 (GenBank accession number KY435887) encode 489 and 459 amino acids, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that SmGRAS1 clustered with Arabidopsis AtSHR, while SmGRAS2 clustered with AtPAT1 ( Figure S1 ). The SHR and PAT1 subfamilies are involved in the root development, light signaling, and stress tolerance. The results indicated the potential functions of the two genes in the root development of S. miltiorrhiza.

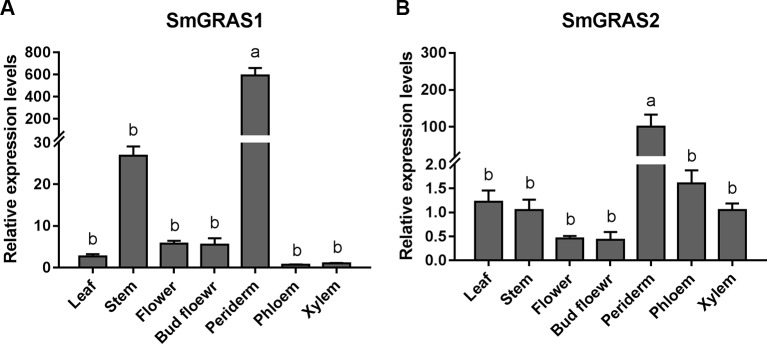

Expression Pattern of SmGRAS1/2

To determine the potential functions of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 in S. miltiorrhiza, we detected their expression patterns in leaf, stem, flower, bud flower, periderm, phloem, and xylem tissue ( Figure 1 ). SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 were expressed in all these tissues, remarkably higher in the periderm. Considering that diterpenoid tanshinones not only accumulate but are also biosynthesized in the periderm of S. miltiorrhiza roots (Xu et al., 2015a; Xu et al., 2015b), the highest expressions of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 in the periderm suggest that SmGRAS1/2 might be functionally involved in tanshinones biosynthesis in the periderm of S. miltiorrhiza roots.

Figure 1.

Tissue-specific expressions of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2. (A) Tissue-specific expressions of SmGRAS1 in leaf, stem, flower, bud flower, periderm, phloem, and xylem tissues of S. miltiorrhiza roots. (B) Tissue-specific expressions of SmGRAS2 in leaf, stem, flower, bud flower, periderm, phloem, and xylem tissues of S. miltiorrhiza roots. The expression levels were normalized to values in the xylem. Standard errors were calculated from three sets of biological replicates. Significant differences using one-way ANOVA and S-N-K comparison tests, P < 0.05.

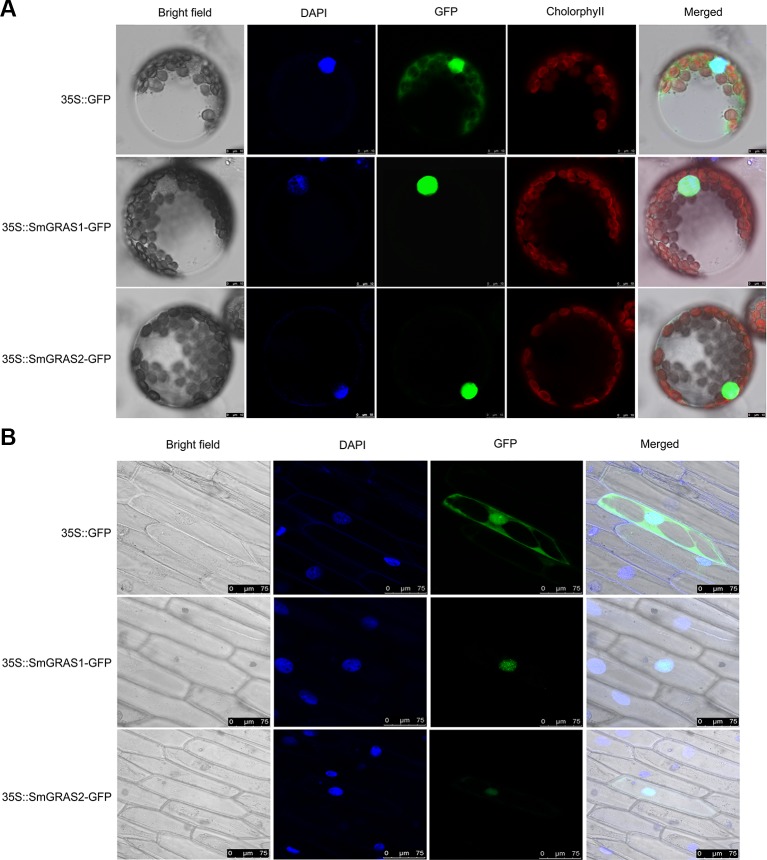

Subcellular Localization and Transactivation Activity of SmGRAS1/2

To identify the subcellular localization of SmGRAS1/2, we fused the SmGRAS1/2 proteins with GFP label. The GFP signal was scanned in the protoplasts of tobacco leaves ( Figure 2A ) and onion epidermal cells ( Figure 2B ). The results showed that the GFP controls distributed throughout the cell, while the SmGRAS1/2 were localized only in the nucleus. The results indicated that SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 might function as TF.

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2. (A) Subcellular localization of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 in protoplasts of tobacco leaves. (B) Subcellular localization of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 in onion epidermal cells. Upper images represent the green fluorescent protein (GFP) control, while lower images represent the SmGRAS1/2-GFP fusion proteins. GFP, green fluorescence; DAPI, fluorescence of DAPI nuclear dye; Cholorophyll, chloroplast autofluorescence; Bright field, field observations; Merged, merge of bright field and relevant fluorescence.

To further verify the characteristics of SmGRAS1/2, the transactivation activity of SmGRAS1/2 were analyzed. The results showed that the SmGRAS1/2-pGBKT7 and control yeast were able to survive on SD/-Trp medium. The yeast with SmGRAS1-pGBKT7 and positive control grew normally but the yeast with SmGRAS2-pGBKT7 and negative control constructs could not grow on SD/-Trp-His-Ade medium ( Figure S2 ). These results demonstrated that SmGRAS1 had transcriptional activity, while SmGRAS2 had no transcriptional activity.

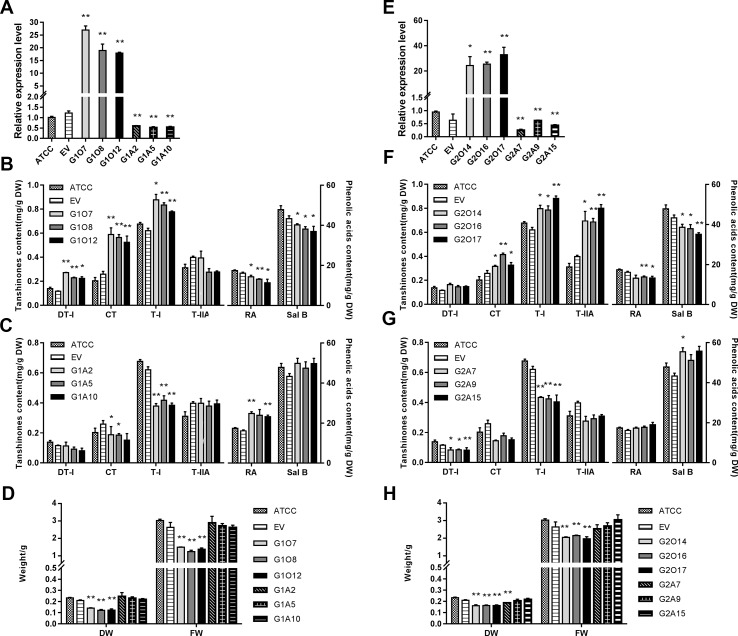

SmGRAS1/2 Regulate the Root Growth and Biosynthesis of Tanshinones, GA, and Phenolic Acids

To explore the regulatory role of SmGRAS1/2 in the biosynthesis of tanshinones, phenolic acids, and GA, OE and antisense expression (AE) approaches were used to generate respective transgenic hairy roots lines. The positive transgenic hairy roots were identified by PCR ( Figure S3 ). Hairy roots developed using ATCC15834 without plasmids were the controls (ATCC). Three independent OE and AE lines of each gene were selected for further experiments. Together, the expression of SmGRAS1/2 were 15–35 fold higher in the OE lines than in the control but decreased by 30%–70% in the AE lines ( Figures 3A, E ).

Figure 3.

Root growth and the biosynthesis of tanshinones, phenolic acids, and GA in the control and transgenic hairy roots. (A, E) Relative quantitative analysis of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 expressions in the transgenic lines and controls. (B, C) Analysis of tanshinones and phenolic acids productions from SmGRAS1 OE and AE hairy root lines. (F, G) Analysis of tanshinones and phenolic acids productions from SmGRAS2 overexpression (OE) and antisense expression (AE) hairy root lines. (D, H) Root biomass of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 transgenic lines. Standard errors were calculated from three sets of biological replicates. Significant differences using Student’s t-test, * 0.01 < P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01).

The biomass of the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines was significantly reduced, and that of the AE lines showed little change compared with the control ( Figures 3D, H ), which could be due to the redundancy among the SmGRAS genes. This result was consistent with the phenotypes of the control and SmGRAS1/2 transgenic hairy roots ( Figure S4 ). The results indicated that SmGRAS1/2 could inhibit the root growth.

The HPLC analysis showed that the tanshinones (DT-I, CT, T-I, T-IIA) contents were significantly increased in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines compared to the controls ( Figures 3B, F ). CT content in SmGRAS1 OE lines and T-IIA content in SmGRAS2 OE lines increased the most, reaching about 2-fold of the controls. In contrast, the contents of four tanshinones were reduced in the SmGRAS1/2 AE lines, especially T-I ( Figures 3C, G ). In addition, the RA and salvianolic acid B contents were decreased in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines and increased in the AE lines ( Figures 3B, C, F, G ). The results showed that SmGRAS1/2 promoted the accumulation of tanshinones but reduced the accumulation of phenolic acids. As we speculated that the decline of root biomass in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines might be associated with the decrease of active GA content, we also quantified the GA content in the G1O7 and G2O17 lines. The concentration of GA in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines was significantly decreased by more than a half compared to that of the control lines ( Figure 5G ). These data supported the speculation that the inhibition of root growth was tightly associated with a reduced GA content.

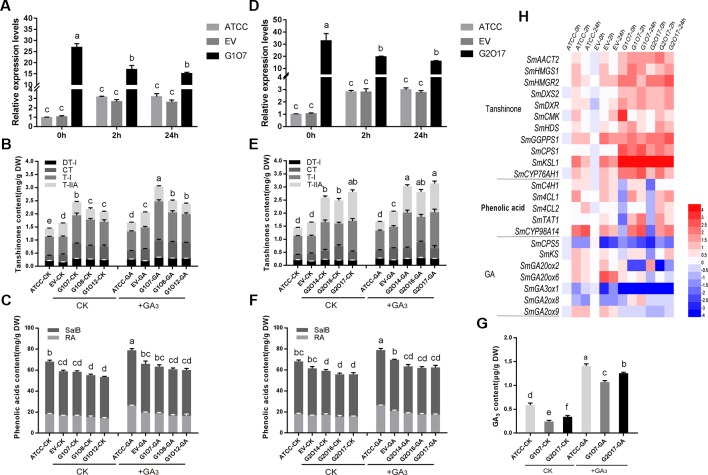

Figure 5.

GA affects the root biomass and the contents of tanshinones, phenolic acids, and GA in SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 OE hairy roots. (A, D) Relative quantitative analysis the expressions of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 in the OE lines and controls with or without 100 µM GA treatment for 2/24 h. (B, C) Analysis of tanshinones and phenolic acids productions from SmGRAS1 OE lines and controls with or without 100 µM GA treatment for 6 days. (E, F) Analysis of tanshinones and phenolic acids productions from SmGRAS2 OE lines and controls with or without 100 µM GA treatment for 6 days. (G) Analysis of GA production from SmGRAS1/2 OE lines and controls with or without 100 µM GA treatment for 6 days. (H) Relative expression levels of genes involved in tanshinones, phenolic acids and GA biosyntheses in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines with 100 µM GA treatment for 2/24 h. Standard errors were calculated from three sets of biological replicates. Significant differences using one-way ANOVA and S-N-K comparison tests, P < 0.05.

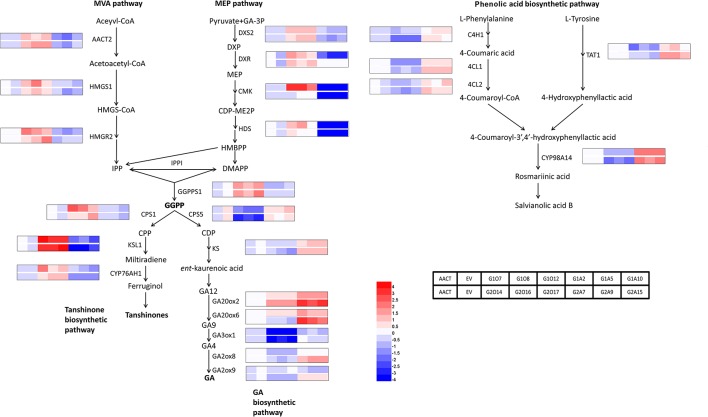

To identify biosynthetic genes regulated by SmGRAS1/2 in S. miltiorrhiza, we measured the expressions of key enzyme genes in the tanshinones, GA, and phenolic acids biosynthetic pathways ( Figure 4 ). As expected, expressions of the genes whose promoters contained the GA response element GARE motif and P-box were consistent with HPLC results. Expressions of most tanshinones biosynthetic genes, except for CMK and HDS, were upregulated to various degrees in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines. Among these genes, the first key enzyme gene CPS1 in the biosynthesis from diterpenoids common precursor GGPP to tanshinones was upregulated and the downstream gene KSL1 was the most dramatically upregulated one in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines. In contrast, expressions of most tanshinones biosynthetic genes were decreased in the AE lines. Expressions of most of GA biosynthetic downstream genes, except for GA20ox2/6, were inhibited in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines. And the first key enzyme gene CPS5 in the biosynthesis from diterpenoids common precursor GGPP to GA was downregulated in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines. In addition, the expressions of most phenolic acids biosynthetic genes were downregulated in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines and upregulated in the AE lines. Collectively, our data indicated that SmGRAS1/2 could regulate the biosynthesis of tanshinones, phenolic acids, and GA through regulating the expressions of key biosynthesis genes. Taken together, our results suggested that SmGRAS1/2 inhibited root growth, GA and phenolic acids biosynthesis, but promoted tanshinones biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

Relative expression levels of tanshinones, phenolic acids and GA biosynthesis pathway genes in SmGRAS1/2 transgenic and control hairy roots (21-day-old). Each line had three biological replicates. The expression levels were normalized to values in the ATCC lines. Blocks with colors indicate low/downregulated expression (blue), high/upregulated expression (red), or no expression/no change (white).

Roles of SmGRAS1/2 in the GA-Mediated Root Growth and Biosynthesis of Tanshinones and Phenolic Acids

Since overexpressing of SmGRAS1/2 caused the transgenic hairy roots to grow slower, the inhibition of root growth was similar to the GA-deficient phenotypes. To further confirm whether the regulatory functions of SmGRAS1/2 are GA-dependent, we then used GA to treat the SmGRAS1/2 OE and control lines. GA treatment significantly upregulated and downregulated the expressions of SmGRAS1/2 in the control lines and SmGRAS1/2 OE lines, respectively ( Figures 5A, D ). The root biomass and GA content of SmGRAS1/2 OE lines were significantly increased under GA treatments ( Figures 5G , S5 ), which showed that the inhibition of SmGRAS1/2 in root growth might be mainly caused by GA deficiency. Intriguingly, tanshinones contents were also significantly increased under GA treatments ( Figures 5B, E ). Furthermore, GA treatment increased the phenolic acids contents in the control and SmGRAS1/2 OE lines ( Figures 5C, F ). Collectively, these changes in root biomass, GA, and phenolic acids contents in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines were the opposite after GA treatment. These results indicated that SmGRAS1/2 played negative roles in GA-regulated root growth and phenolic acids biosynthesis but that the roles of SmGRAS1/2 in regulating tanshinones biosynthesis were an exception.

As expected, the expressions of most tanshinones biosynthesis genes were quickly induced by GA application, as shown by an early peak at 2 h and a relatively high level of expressions at all sampling times ( Figure 5H ). Among these genes, the expression of downstream key enzyme gene KSL1 had the most significant increasement. Expressions of most phenolic acids biosynthesis genes were also upregulated. The expressions of phenolic acids biosynthesis genes and downstream key enzyme gene CYP98A14 were significantly increased. In addition, the expressions of GA biosynthesis key genes were different and GA30xo1 was the most significantly downregulated gene among them. Collectively, the expressions of these biosynthetic pathway genes were consistent with the content changes. Taken together, our results indicated that SmGRAS1/2 regulated root growth and phenolic acids biosynthesis probably through GA-dependent pathways but the regulation of tanshinones biosynthesis was not.

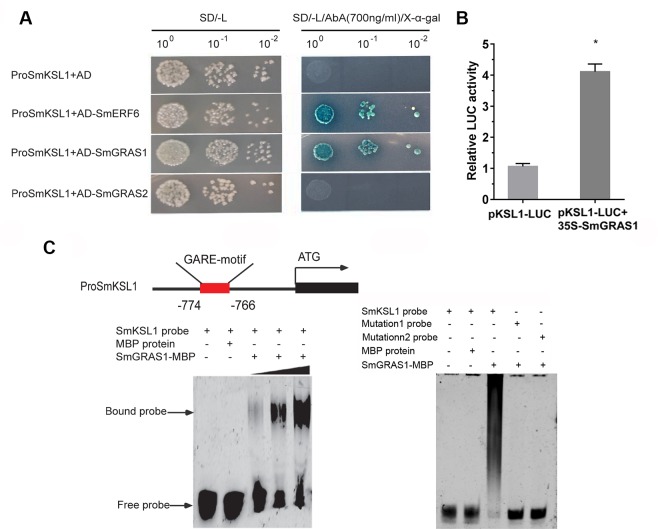

SmGRAS1 Binds to the Promoter of SmKSL1 Involved in Tanshinones Biosynthesis

Because only the regulation of SmGRAS1/2 to tanshinones biosynthesis was not affected by GA treatment, we speculated that SmGRAS1/2 might directly regulate the expressions of the tanshinones biosynthetic pathway genes. According to our qRT-PCR results, SmKSL1, which is the key downstream gene in tanshinones biosynthesis, was remarkably upregulated in SmGRAS1/2 OE lines. Moreover, its promoter had a GA response elements GARE motif. Y1H and EMSA assays were performed to demonstrate whether SmGRAS1/2 could bind to the GARE motif of the SmKSL1 promoter. The Y1HGold reporter of the strains that had the SmKSL1 promoter transformed with SmGRAS1 prey plasmid could grow on SD/-Leu (700 ng/ml AbA) but the strains that had the SmGRAS2 prey plasmid could not grow ( Figure 6A ). These results showed that SmGRAS1 could directly bind to SmKSL1 promoter. This was further confirmed by Dual-LUC report system. Dual-LUC assay showed that SmGRAS1 could directly activate the SmKSL1 promoter ( Figure 6B ).

Figure 6.

SmGRAS1 binds to the SmKSL1 promoter and activates its expression. (A) Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays shows the interactions between SmGRAS1/2 and the SmKSL1 promoter. SmKSL1 promoter + pGADT7 as the negative control and SmKSL1 promoter + pGADT7-SmERF6 as the positive control. (B) Dual-luciferase (Dual-LUC) assay shows the effects of SmGRAS1 on SmKSL1 promoter activation. (C) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis of SmGRAS1 binding to the GARE-motif of the SmKSL1 promoter. Schematic diagram showing the GARE motif in the SmKSL1 promoter.

To further confirm the bond between SmGRAS1 and the GARE motif of the SmKSL1 promoter in vitro, purified SmGRAS1-MBP fusion proteins were combined with the fragment containing the GARE motif and they were analyzed by EMSA. Subsequently, specific DNA–SmGRAS1 protein complex was strongly detected ( Figure 6C ). However, SmGRAS1 could not bind to the mutated GARE motif fragments ( Figure 6C ). These results confirmed that SmGRAS1 participated in regulating tanshinones biosynthesis by directly binding to the GARE motif of the SmKSL1 promoter.

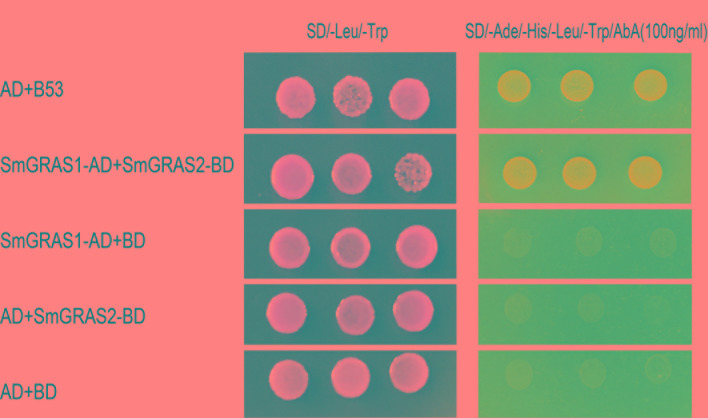

Physical Interaction Between SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2

Since SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 had similar functions in regulating the biosynthesis of tanshinones and phenolic acids, Y2H assays were utilized to investigate this interaction. Y2H yeast cells co-transformed by SmGRAS1-AD and SmGRAS2-BD not only grew well on SD/-Leu/-Trp medium, but also grew on the SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/AbA medium, and could turn blue in the α-X-Gal staining assay. However, all the Y2H yeast cells that harbored the negative controls could only grow on the SD/-Leu/-Trp medium but not on SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/AbA medium ( Figure 7 ).

Figure 7.

SmGRAS1 interacts with SmGRAS2. Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays to detect the interaction of SmGRAS1 with SmGRAS2. Transformed Y2H are grown on SD/-Leu/-Trp or SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/AbA with α-X-Gal. The co-transformed pGBKT7 and pGADT7-53 vector as the positive control, pGBKT7 and pGADT7-lam vector as the negative control.

Discussion

SmGRAS1/2 Involved in Tanshinones Biosynthesis

As the major active ingredient of S. miltiorrhiza, tanshinones contents have been reported to be concentrated in the periderm of root (Xu et al., 2015a; Xu et al., 2015b). As the key regulators in GA signal, GRAS family genes have been reported involved in the regulation of root growth (Gong et al., 2016). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that SmGRAS1 clustered with Arabidopsis AtSHR, which was highly expressed in root tip tissue and participated in Arabidopsis root development (Cui et al., 2007). SmGRAS2 clustered with AtPAT1, which had been reported to participate in light signaling and stress tolerance (Hakoshima, 2018). The tissue-specific expressions of GRAS genes pointed to their functional roles in root development. For instance, VviSHR3 was more highly expressed in the roots than in other tissues in Vitis vinifera, and its tomato ortholog SlGRAS16 was also predicted to be involved in root development (Huang et al., 2015; Grimplet et al., 2016). Considering that diterpenoids tanshinones not only accumulate but are also biosynthesized in the periderm of S. miltiorrhiza roots (Xu et al., 2015a; Xu et al., 2015b), the highest expressions of SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 in the periderm indicated that SmGRAS1/2 functionally involved in tanshinones biosynthesis in the periderm of S. miltiorrhiza roots. Moreover, GA could increase tanshinones accumulation and induce the SmGRAS1 and SmGRAS2 genes response in the wild-type hairy roots of S. miltiorrhiza in our previous study (Bai et al., 2017), which further confirmed the potential functions of two genes in GA-mediated secondary metabolite accumulation in the roots of S. miltiorrhiza.

SmGRAS1/2 Promote Tanshinones Biosynthesis and Inhibit GA Biosynthesis by Regulating the Metabolic Flux in the Roots of S. miltiorrhiza

Both as diterpenoids, GA and tanshinones has a common biosynthesis precursor GGPP. There exists a tradeoff between GA and tanshinones biosynthesis. The biosynthetic pathways of GA and tanshinones involves many enzymes. Many TFs have been reported to have universal regulatory functions in terpenoid biosynthesis (Lu et al., 2016). However, studies on the regulation of SmGRASs to secondary metabolism in S. miltiorrhiza have not been reported. In our study, SmGRAS1/2 OE hairy roots grow slower than the control. Similarly, tomato primary and lateral root growth in SlGRAS24 OE lines were strongly suppressed (Huang et al., 2017). The results indicated that SmGRAS1/2 were the inhibitors of root growth. And the GA content in the OE lines was also decreased higher than the control. These data supported the speculation that the inhibition of root growth was tightly associated with a reduced GA content. It has been reported that overexpressing HaGRASL reduces the metabolic flow of GAs in Arabidopsis, which could be relevant in axillary meristem development (Fambrini et al., 2015). Silencing SlGRAS26 inhibit the GA biosynthetic pathway but promote the GA inactivation pathway, and finally resulted in GA deficiency in tomato (Zhou et al., 2018). The decreased expression of SlGRAS2 is associated with a reduction in active GA, leading to a deficiency in positive growth signals during ovary development in tomato (Li et al., 2018). Overexpressing of SmGRAS1/2 also inhibited the phenolic acids and promoted tanshinones biosynthesis through regulating the biosynthetic pathway genes. Many biosynthetic pathway genes such as C4H, TAT, DXS, GGPPS, and CYP76AH1, have been reported to promote the phenolic acids or tanshinones accumulation (Xiao et al., 2011; Ma et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2016). The downstream pathway genes from GGPP to GA were downregulated and the genes from GGPP to tanshinones was upregulated. Therefore, these results implied that SmGRAS1/2 could regulate the flow of metabolites by catalyzing the precursor GGPP to synthesize more tanshinones but inhibit the GA biosynthetic pathway. Taken together, SmGRAS1/2 acted as positive regulators of tanshinones biosynthesis and negative regulators of GA and phenolic acids biosynthesis.

SmGRAS1/2 Regulate Root Growth and Phenolic Acids Biosynthesis in GA-Dependent Pathway, But Regulate Tanshinones by Directly Binding to the SmKSL1 Promoter

Since SmGRAS1/2 OE lines showed some GA-deficient phenotypes. To explore whether the regulations of SmGRAS1/2 to phenolic acids and tanshinones biosynthesis were involved in GA signaling pathway, we treated SmGRAS1/2 OE and control lines with GA. GA treatment recovered the inhibition of SmGRAS1/2 on root growth. And the GA content was also increased after GA treatment. The result showed that the increased GA content in the SmGRAS1/2 OE lines maybe not have occurred by promoting GA biosynthesis but could have also been caused by exogenous GA entering the cell. And the inhibition of SmGRAS1/2 in root growth was mainly caused by the GA deficiency, and the inhibition could be restored by adding GA.

In addition, GA has been reported to promote the accumulation of secondary metabolites as well as the expressions of related biosynthetic genes. For instance, GA could induce SmHPPR response, which was highly correlated with hydrophilic phenolic acids accumulation (Wang et al., 2017). After GA treatment, the phenolic acids contents were increased and most of the biosynthetic pathway genes were also upregulated, which had opposite changes compared to the OE lines before treatment. The results showed that SmGRAS1/2 regulated phenolic acids biosynthesis dependent on GA signaling pathway. SmGRAS1/2 played negative regulatory roles in GA-mediated root growth and phenolic acids biosynthesis.

Interestingly, the tanshinones contents of SmGRAS1/2 OE and control lines all increased after GA treatment. This result indicated that SmGRAS1/2 and GA had some independent ways of regulating tanshinones biosynthesis. Studies had shown that GRAS could interact with the promoter of downstream genes and regulate their expressions (Hirsch et al., 2009). For instance, OsGRAS23 could bind to the promoters of its potential target genes to positively modulate rice drought tolerance (Xu et al., 2015a; Xu et al., 2015b). SlGRAS2 regulated the expressions of downstream genes related to fruit development (Li et al., 2018). We speculated that SmGRAS1/2 could directly regulated tanshinones biosynthesis genes. Considering the significant response of SmKSL1 to SmGRAS1/2 and GA. Y1H, Dual-LUC and EMSA assays demonstrated that SmGRAS1 could directly regulate tanshinones biosynthesis by activating SmKSL1 rather than through GA-dependent regulation, while SmGRAS2 might regulate the tanshinones biosynthesis through interacting with SmGRAS1. These results indicated that SmGRAS1/2 played negative roles in GA-regulated root growth and phenolic acids biosynthesis but that the roles of SmGRAS1/2 in regulating tanshinones biosynthesis were an exception.

However, SmKSL1 was likely not the only target gene for GRAS1 regulation. GRAS could also interact with other TFs to mediate the regulation of transcription activity of other target genes. For instance, DELLA protein could interact with SG7 MYBs to regulate the transcriptional levels of the flavonol biosynthesis pathway key genes (Tan et al., 2019). Therefore, identifying new interactive partners or targets of SmGRAS1/2 may provide further insight into the molecular mechanism of SmGRAS1/2-mediated regulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis.

Conclusion

As the medicinal parts of S. miltiorrhiza, the roots contain very low contents of tanshinones and phenolic acids. Therefore, improving S. miltiorrhiza root biomass and the accumulation of the two major bioactive compounds, tanshinones and phenolic acids, in S. miltiorrhiza roots has a crucial influence on the quality of medicinal materials. However, few functional genes have been reported to regulate both root growth and secondary metabolism. Our study revealed that SmGRAS1/2 could regulate the flow of diterpenoids biosynthesis pathway by catalyzing the precursor GGPP to synthesize more tanshinones but inhibiting GA biosynthetic pathway. Notably, SmGRAS2 interacted with SmGRAS1 to form a complex, and promoted the biosynthesis of tanshinones through directly binding to the promoter of SmKSL1. In summary, SmGRAS1/2 acted as repressors in the regulation of GA-mediated root growth and phenolic acids biosynthesis and positive regulators in tanshinones biosynthesis. These results provided theoretical guidance for improving the yield and quality of medicinal materials. More work is needed to fully understand the specific mechanism of SmGRAS proteins regulate secondary metabolism in S. miltiorrhiza.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

WL and ZL conceived and designed the experiments. WL, ZB, TP, RM, BZ, and CL preformed the experiments. WL and DY analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81373908) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China through the Twelfth Five-Year National Science and Technology Pillar Program (No. 2015BAC01B03).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ningjuan Fan, Hui Duan, and Jingquan Kang (Northwest A & F University) for providing experimental instrument and instruction.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.01367/full#supplementary-material

References

- Bai Z. Q., Xia P. G., Wang R. L., Jiao J., Ru M., Liu J. L., et al. (2017). Molecular cloning and characterization of five SmGRAS genes associated with tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Plos One 12, e0185322. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z. Q., Li W. R., Jia Y. Y., Yue Z. Y., Jiao J., Huang W. L., et al. (2018). The ethylene response factor SmERF6 co-regulates the transcription of SmCPS1 and SmKSL1 and is involved in tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Planta 248, 243–255. 10.1007/s00425-018-2884-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G. H., Duan L. X., Jin B. L., Qian J., Xue Z. Y., Shen G. A., et al. (2015). Functional divergence of diterpene syntheses in the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza . Plant Physiol. 169, 1607–1618. 10.1104/pp.15.00695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H. C., Levesque M. P., Vernoux T., Jung J. W., Paquette A. J., Gallagher K. L., et al. (2007). An evolutionarily conserved mechanism delimiting SHR movement defines a single layer of endodermis in plants. Science 316, 421–425. 10.1126/science.1139531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davière J. M., Achard P. (2016). A pivotal role of DELLAs in regulating multiple hormone signals. Mol. Plant 9, 10–20. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y. Z., Morris-natschke S. L., Lee K. H. (2011). Biosynthesis, total syntheses, and antitumor activity of tanshinones and their analogs as potential therapeutic agents. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28, 529–542. 10.1039/c0np00035c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q., Li C. L., Li D. Q., Lu S. F. (2015). Genome-wide analysis, molecular cloning and expression profiling reveal tissue-specifically expressed, feedback-regulated, stress-responsive and alternatively spliced novel genes involved in gibberellin metabolism in Salvia miltiorrhiza . BMC Genomics 16, 1087. 10.1186/s12864-015-2315-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fambrini M., Mariotti L., Parlanti S., Salvini M., Pugliesi C. (2015). A GRAS-like gene of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) alters the gibberellin content and axillary meristem outgrowth in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biol. 17, 1123–1134. 10.1111/plb.12358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Flores-Vergara M. A., Hong J. H., Chu H. W., Lim J., Franks R. G., et al. (2016). SEUSS integrates gibberellin signaling with transcriptional inputs from the SHR-SCR-SCL3 module to regulate middle cortex formation in the Arabidopsis Root. Plant Physiol. 170, 1675–1683. 10.1104/pp.15.01501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimplet J., Agudelo-romero P., Teixeira R. T., Martinez-zapater J. M., Fortes A. M. (2016). Structural and functional analysis of the GRAS gene family in grapevine indicates a role of GRAS proteins in the control of development and stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 353–374. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakoshima T. (2018). Structural basis of the specific interactions of GRAS family proteins. FEBS Lett. 592, 489–501. 10.1002/1873-3468.12987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck C., Kuhn H., Heidt S., Walter S., Rieger N., Requena N. (2016). Symbiotic fungi control plant root cortex development through the novel GRAS transcription factor MIG1. Curr. Biol. 26, 2770–2778. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch S., Kim J., Munoz A., Heckmann A. B., Downie J. A., Oldroyd G. E. (2009). GRAS proteins form a DNA binding complex to induce gene expression during nodulation signaling in Medicago truncatula . Plant Cell 21, 545–557. 10.1105/tpc.108.064501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Sun M. H., Yuan T. P., Wang Y., Shi M., Lu S. J., et al. (2019). The AP2/ERF transcription factor SmERF1L1 regulates the biosynthesis of tanshinones and phenolic acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza . Food Chem. 274, 368–375. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.08.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Xian Z. Q., Kang X., Tang N., Li Z. G. (2015). Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of GRAS gene family in tomato. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 209. 10.1186/s12870-015-0590-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Peng S. Y., Xian Z. Q., Lin D. B., Hu G. J., Yang L., et al. (2017). Overexpression of a tomato miR171 target gene SlGRAS24 impacts multiple agronomical traits via regulating gibberellin and auxin homeostasis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 472–488. 10.1111/pbi.12646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W. Y., Jeon B. H., Kim Y. C., Lee S. H., Sohn D. H., Seo G. S. (2013). PF2401-SF, standardized fraction of Salvia miltiorrhiza shows anti-inflammatory activity in macrophages and acute arthritis in vivo . Int. Immunopharmacol. 16, 160–164. 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai G. Y., Xu H., Zhou C. C., Liao P., Xiao J. B., Luo X. Q., et al. (2011). Metabolic engineering tanshinone biosynthetic pathway in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures. Metab. Eng. 13, 319–327. 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang X., Li C. X., Li H. X., Zhang J. H., Ye Z. B. (2018). Silencing GRAS2 reduces fruit weight in tomato. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 60, 498–513. 10.1111/jipb.12636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. (2011). A transient expression assay using Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts. Bio-Protocol 1, e70. 10.21769/BioProtoc.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z. S., Ma Y. N., Xu T., Cui B. M., Liu Y., Guo Z. X., et al. (2013). Effects of abscisic acid, gibberellin, ethylene and their interactions on production of phenolic acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge hairy roots. Plos One 8, e72806. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Yang D. F., Liang T. Y., Zhang H. H., He Z. G., Liang Z. S. (2016). Phosphate starvation promoted the accumulation of phenolic acids by inducing the key enzyme genes in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 1933–1942. 10.1007/s00299-016-2007-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livne S., Lor V. S., Nir I., Eliaz N., Aharoni A., Olszewski N. E., et al. (2015). Uncovering DELLA-independent gibberellin responses by characterizing new tomato procera mutants. Plant Cell 27, 1579–1594. 10.1105/tpc.114.132795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Tang K. X., Li P. (2016). Plant metabolic engineering strategies for the production of pharmaceutical terpenoids. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1647. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas M., Swarup R., Paponov I. A., Swarup K., Casimiro I., Lake D., et al. (2011). Short-Root regulates primary, lateral, and adventitious root development in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiol. 155, 384–398. 10.1104/pp.110.165126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X. H., Ma Y., Tang J. F., He Y. L., Liu X. J., Shen Y., et al. (2015). The biosynthetic pathways of tanshinones and phenolic acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza . Molecules 20, 16235–16254. 10.3390/molecules200916235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Ma X. H., Meng F. Y., Zhan Z. L., Guo J., Huang L. Q. (2016). RNA interference targeting CYP76AH1 in hairy roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza reveals its key role in the biosynthetic pathway of tanshinones. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 477, 155–160. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y. M., Yuan L. C., Wu B., Li X. E., Chen S. L., Lu S. F. (2012). Genome-wide identification and characterization of novel genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza . J. Exp. Bot. 63, 2809–2823. 10.1093/jxb/err466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mornya P., Cheng F. Y. (2018). Effect of Combined Chilling and GA3 Treatment on Bud Abortion in Forced ‘Luoyanghong’ Tree Peony (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.) Hortic. Plant J. 4, 250–256. 10.1016/j.hpj.2018.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pei T. L., Ma P. D., Ding K., Liu S. J., Jia Y. Y., Ru M., et al. (2018). SmJAZ8 acts as a core repressor regulating JA-induced biosynthesis of salvianolic acids and tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 1663–1678. 10.1093/jxb/erx484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro D. M., Araújo W. L., Fernie A. R., Schippers J. H. M., Bernd M. R. (2012). Translatome and metabolome effects triggered by gibberellins during rosette growth in Arabidopsis . J. Exp. Bot. 63, 2769–2786. 10.1093/jxb/err463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ru M., An Y. Y., Wang K. R., Peng L., Li B., Bai Z. Q., et al. (2016). Prunella vulgaris L. hairy roots: culture, growth, and elicitation by ethephon and salicylic acid. Eng. Life Sci. 16, 494–502. 10.1002/elsc.201600001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ru M., Wang K. R., Bai Z. Q., Peng L., He S. X., Wang Y., et al. (2017). A tyrosine aminotransferase involved in rosmarinic acid biosynthesis in Prunella vulgaris L. Sci. Rep. 7, 4892. 10.1038/s41598-017-05290-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M., Luo X. Q., Ju G. H., Li L. L., Huang S. X., Zhang T., et al. (2016). Enhanced diterpene tanshinone accumulation and bioactivity of transgenic Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots by pathway engineering. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 2523–2530. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su P., Tong Y. R., Cheng Q. Q., Hu Y. T., Zhang M., Yang J., et al. (2016). Functional characterization of ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase, kaurene synthase and kaurene oxidase in the Salvia miltiorrhiza gibberellin biosynthetic pathway. Sci. Rep. 6, 23057. 10.1038/srep23057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T. P. (2011). The molecular mechanism and evolution of the GA-GID1-DELLA signaling module in plants. Curr. Biol. 21, 338–345. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H. J., Man C., Xie Y., Yan J. J., Chu J. F., Huang J. R. (2019). A crucial role of GA-regulated flavonol biosynthesis in root growth of Arabidopsis . Mol. Plant 12, 521–537. 10.1016/j.molp.2018.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The State Pharmacopoeia Commission of China (2015). Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China, Part I. Beijing, China: Chemical Industry Press, 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tian C. G., Wan P., Sun S. H., Li J. Y., Chen M. S. (2004). Genome-wide analysis of the GRAS gene family in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 54, 519–532. 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000038256.89809.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. Q., Chen J. F., Bo Y. I., Tan H. X., Zhang L., Chen W. S. (2017). HPPR encodes the hydroxyphenylpyruvate reductase required for the biosynthesis of hydrophilic phenolic acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza . Chin. J. Nat. Med. 15, 917–927. 10.1016/S1875-5364(18)30008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Zhang L., Gao S. H., Seachao S., Di P., Chen J. F., et al. (2011). The c4h, tat, hppr and hppd genes prompted engineering of rosmarinic acid biosynthetic pathway in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures. Plos One 6, e29713. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K., Chen S. J., Li T. F., Ma X. S., Liang X. H., Ding X. F., et al. (2015. a). OsGRAS23, a rice GRAS transcription factor gene, is involved in drought stress response through regulating expression of stress-responsive genes. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 141. 10.1186/s12870-015-0532-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. C., Peters R. J., Weirather J., Luo H. M., Liao B. S., Zhang X., et al. (2015. b). Full-length transcriptome sequences and splice variants obtained by a combination of sequencing platforms applied to different root tissues of Salvia miltiorrhiza and tanshinone biosynthesis. Plant J. 82, 951–961. 10.1111/tpj.12865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z. C., Luo H. M., Ji A. J., Zhang X., Song J. Y., Chen S. L. (2016). Global identification of the full-length transcripts and alternative splicing related to phenolic acid biosynthetic genes in Salvia miltiorrhiza . Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1–10. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. F., Hou S., Cui G. H., Chen S. L., Wei J. H., Huang L. Q. (2010). Characterization of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in various tissues of Salvia miltiorrhiza . Mol. Biol. Rep. 37, 507–513. 10.1007/s11033-009-9703-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. L., Ogawa M., Fleet C. M., Zentella R., Hu J. H., Heo J. O., et al. (2011). SCARECROW-LIKE 3 promotes gibberellin signaling by antagonizing master growth repressor DELLA in Arabidopsis . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 2160–2165. 10.1073/pnas.1012232108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S. G., Hu Z. L., Li F. F., Yu X. H., Naeem M., Zhang Y. J., et al. (2018). Manipulation of plant architecture and flowering time by down-regulation of the GRAS transcription factor SlGRAS26 in Solanum lycopersicum . Plant Sci. 271, 81–93. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.