Summary

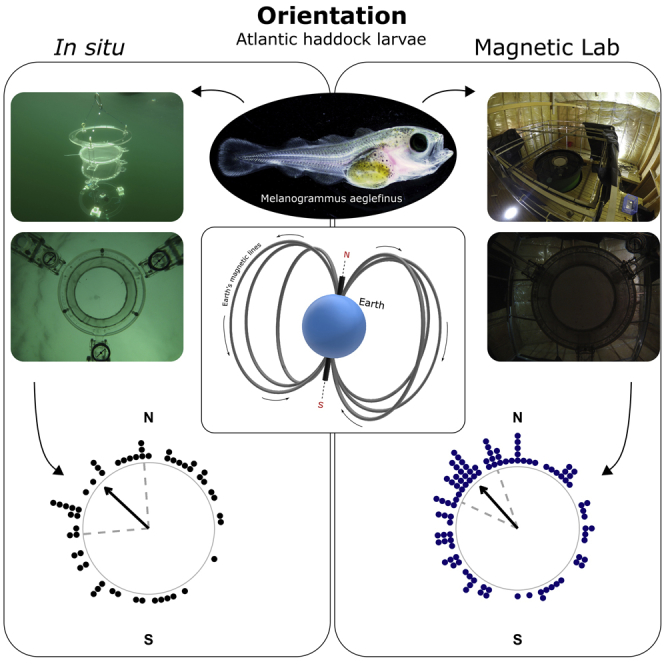

Atlantic haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) is a commercially important species of gadoid fish. In the North Sea, their main spawning areas are located close to the northern continental slope. Eggs and larvae drift with the current across the North Sea. However, fish larvae of many taxa can orient at sea using multiple external cues, including the Earth's magnetic field. In this work, we investigated whether haddock larvae passively drift or orient using the Earth's magnetic field. We observed the behavior of 59 and 102 haddock larvae swimming in a behavioral chamber deployed in the Norwegian North Sea and in a magnetic laboratory, respectively. In both in situ and laboratory settings, where the magnetic field direction was modified, haddock larvae significantly oriented toward the northwest. We conclude that haddock larvae orientation at sea is guided by a magnetic compass mechanism. These results have implications for retention and dispersal of pelagic haddock larvae.

Subject Areas: Piscine Behavior, Geomagnetism, Ichthyology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Atlantic haddock larvae drift with the current and spread across the North Sea

-

•

In this area, larvae swimming in situ orient to the northwest

-

•

In a magnetic laboratory, larvae orient to the same direction, the magnetic northwest

-

•

Haddock larvae have a magnetic compass that they use to orient at sea

Piscine Behavior; Geomagnetism; Ichthyology

Introduction

Haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) is a species of great ecological and economic importance that has supported a fishery in the North Sea for more than a hundred years (Pope and Macer, 1996). Haddock stocks exhibit large natural fluctuations in abundance on both annual and decadal timescales (Fogarty and Murawski, 1998, Houde, 2016). The main hypotheses explaining such fluctuations, proposed over a century ago, are based on both survival success of the very early life stages and subsequent recruitment (Hjort, 1914). Specifically, Hjort proposed that the fate of year classes depended on a critical period, occurring at first feeding of the larvae, during which failure to find prey and to feed would result in high mortality, affecting the abundance of adults during the following years (Hjort, 1914). However, Hjort also proposed that year class success could depend on the dispersal of larvae, and on whether favorable or unfavorable transport of eggs and larvae occurs (Hjort, 1914, Houde, 2016). The meaning of favorable transport varies according to the species, as larvae of some species seek retention in their spawning area, whereas larvae of different species might be advantaged by transport to nursery areas, far from the spawning area. The idea behind Hjort's second hypothesis is that favorable currents, together with appropriate larval behavior, would increase the chances of retention in the nursery areas (or transport to nursery grounds), where the probability of survival is higher (Houde, 2016). The main factor in such retention is the interaction between oceanographic conditions and biological mechanisms, such as larval orientation and swimming (Paris et al., 2013, Paris and Cowen, 2004). At mid-high latitutes, information on swimming and orientation behavior of early life stages of fish is available for only a very few species (Faillettaz et al., 2018, Faillettaz et al., 2015, Faria et al., 2009) and there is no information at all for haddock larvae.

In Europe, the largest stocks of haddock are located in the Barents Sea (Northeast Atlantic stocks) (Bergstad et al., 1987) and in the North Sea (Daan et al., 1990). Haddock is demersal; juvenile habitat is associated with the continental shelf/slope and coastal areas (Albert, 1994). In the North Sea, this species undertakes seasonal migrations between the spawning grounds located north-northwest and the more southern feeding areas (Daan et al., 1990, Thompson, 1927). The general circulation pattern of the North Sea results in a south-southeastward drift of haddock larvae, from the spawning areas toward the Skagerrak and the Norwegian trench (Albert, 1994, Heath and Gallego, 1998). Behavioral observations of haddock larvae have focused mainly on feeding (Petrik et al., 2009) and vertical migration during the dispersal phase (Werner et al., 1993). However, little is known about the swimming behavior of haddock larvae at sea, and there is currently no information on whether they perform active and directional swimming or drift passively with the currents. Research on these aspects of haddock larval behavior is needed, as they would make an important contribution to our ability to model retention and dispersal of this species during the early-life stages.

Many late larval stage fish perform oriented swimming in response to/guided by a multiplicity of environmental cues. The larvae of coral reef and Mediterranean fish species use cues such as the sun (Faillettaz et al., 2015, Mouritsen et al., 2013), sound of the reef (Leis et al., 2003, Simpson et al., 2004), polarized light (Berenshtein et al., 2014), and odors (Foretich et al., 2017, Paris et al., 2013) to orient. However, some of these cues might be patchy or unavailable in offshore and/or in deep waters. The only ubiquitous, steady, and directional cue, available at all times, is the Earth's magnetic field. The larvae of some coral reef fish have a magnetic field-based compass mechanism (Bottesch et al., 2016, O’connor and Muheim, 2017) that they might use to reduce dispersal (Bottesch et al., 2016). Similar abilities were reported in post-larval glass eels, which use a magnetic compass linked to an endogenous tidal clock to guide their swimming and orientation (Cresci et al., 2017). However, whether high-latitude fish such as haddock have magnetic orientation abilities at the larval stage is not known.

In this work, we explored the possibility that the pelagic larvae of haddock from the North Sea orient using the Earth's magnetic field. To test this hypothesis, we used a transparent drifting in situ chamber (DISC, Paris et al., 2008) to observe the orientation of haddock larvae in situ. We also tested the orientation of haddock larvae while swimming in DISC when inside a magnetic laboratory facility (MagLab) in which the magnetic field could be manipulated in three dimensions.

Results

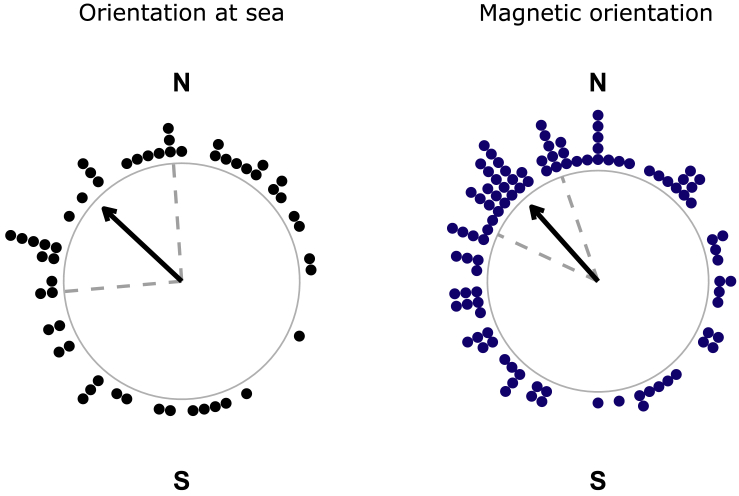

When tested in situ, 91% of larvae (54 of the 59 tested) oriented significantly (Rayleigh test of uniformity applied to the track of each larva (Rayleigh's p < 0.05; Figure S1.3) swimming in the DISC at sea (Figures 1A and 1B). In the MagLab (Figures 1C and 1D), 99% of the larvae (101 of the 102 larvae tested) displayed significant orientation. The haddock larvae that oriented displayed the same mean orientation direction (Figure S1.4) in situ and in the MagLab (Figure 2). Larvae significantly oriented toward the northwest in situ (N = 54; mean angle = 313°, magnetic declination = +1.1°, r = 0.26, p = 0.03; Figure 2) and oriented toward the same direction, the magnetic northwest, in the MagLab (N = 101; mean angle = 318°, magnetic declination = +1.1°, r = 0.34, p = 0.00001; Figure 2). The mean directions of the larvae swimming in situ and in laboratory conditions did not differ statistically (Mardia-Watson-Wheeler test p = 0.49).

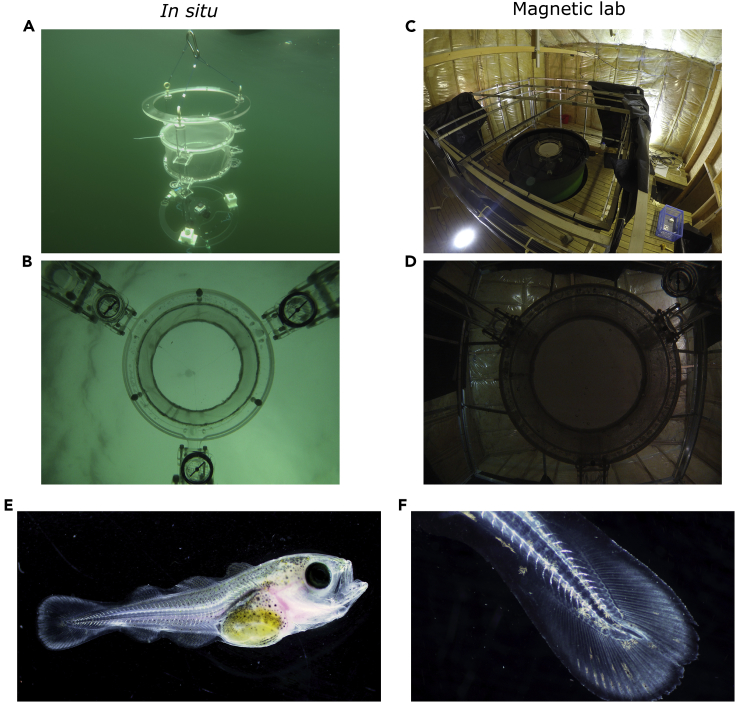

Figure 1.

DISC (Drifting In Situ Chamber), Magnetic Laboratory (MagLab), and Haddock Larvae (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) Used in the Experiments

(A) Photograph of the DISC drifting at sea. The main underwater unit is composed of the chamber, the acrylic frame, the camera, and sets of sensors. In this study the arena has a diameter of 20 cm and is placed 30 cm above a GOPRO camera.

(B) Example of an image from the upward-looking camera placed underneath the behavioral chamber of the DISC.

(C) View of the electric coils setup in the MagLab designed to modify the magnetic field in three dimensions. A tank filled with seawater is present at the center of the coils. The same device used in situ (DISC) is placed at the center of the tank.

(D) Example of an image from the upward-looking camera placed underneath the behavioral chamber of the DISC in the MagLab.

(E) Photograph of larval haddock at 38 days post hatch (dph).

(F) Zoomed-in view of the caudal fin of the larva at 38 dph.

Figure 2.

Orientation of the Haddock Larvae (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) at Sea and in the Magnetic Laboratory (MagLab)

Orientation is presented with respect to the magnetic north (N) and south (S). Each black point corresponds to the mean bearing of one haddock larva in situ (averaged over 600 data points from the video tracks, Figure S1) (N = 54). Each navy blue data point is the mean bearing of one haddock larva in the magnetic laboratory (N = 101). During the experiments, the magnetic north in the laboratory was rotated for each larva (i.e., the magnetic north in the laboratory had a different direction for each of the blue data points). This figure displays the mean bearings of the larvae that showed an individual preferred orientation. The black arrow points toward the mean angle of all the individual bearings (mean bearing in situ = 313°, p = 0.03; mean bearing in the MagLab = 319°, p = 0.00001). Dashed gray lines are the 95% confidence intervals around the mean.

Discussion

Haddock larvae exhibited significant orientation direction when swimming in situ, and the experiments conducted in the MagLab revealed that this is based on a magnetic compass mechanism. These results are consistent with earlier studies showing that fish larvae and adults of multiple species use the Earth's magnetic field to guide their movement. For example, salmon use magnetic cues, imprinted on first contact with saltwater, to find their home estuary later in life (Lohmann et al., 2008, Putman et al., 2013). The magnetic compass of sockeye salmon smolts (Oncorhynchus nerka) depends on the availability of celestial cues (Quinn, 1980), indicating that these orientation mechanisms can be based on a complex combination of multiple cues. Magnetic orientation was also reported in adult European eel (Anguilla anguilla), which are able to detect spatial displacement and reorient using the magnetic field (Durif et al., 2013). Similar abilities were documented in post-larval glass eel, which use a compass mechanism linked to the rhythm of the tide (Cresci et al., 2017). The pelagic larvae of the tropical reef fish, the four line cardinalfish (Ostorhinchus doederleini), use a magnetic compass mechanism to orient against the direction of the current that would otherwise transport them far from the reef (Bottesch et al., 2016). For haddock larvae, the magnetic compass observed in this study could possibly serve a similar function, but on a larger spatial scale.

Haddock larvae develop caudal, anal, and dorsal fin rays and grow large pectoral fins, when they are 8–9 mm in length (Auditore et al., 1994) (Figures 1E and 1F), which greatly improves their swimming ability and maneuverability. Based on the locations at which larvae of different ages were distributed, it was estimated that they might swim at speeds ranging from 0.65 to 1 cm s−1 (Lough and Bolz, 2006). These swimming speeds, coupled with the orientation abilities observed here, could play a significant role in the dispersal and retention of haddock larvae in the North Sea. The inflow of saline Atlantic water from the north is the main factor driving the overall circulation pattern of the North Sea (Sundby et al., 2017). Atlantic water enters the region through two large branches. One shallower current flows along the eastern Shetlands, and the second deeper current enters the North Sea at the western boundary of the Norwegian trench (Sundby et al., 2017). This water mass defines the northern sub-region of the North Sea, where there is the highest diversity of fish species (Heessen et al., 2015). These areas also host the main spawning grounds of the North Sea haddock, located near the continental slope of North East Scotland and the Orkney and Shetland Isles (Daan et al., 1990, Heath and Gallego, 1998). In this context, haddock are hypothesized to be separated into two main sub-populations within the northern part of North Sea, a northwestern and a northeastern one (Wright et al., 2011).

From these areas, the general circulation of the North Sea flows mainly southward with a branch expanding southeast toward the Skagerrak and the Norwegian deep (Albert, 1994, Heath and Gallego, 1998, Turrell, 1992). These currents transport eggs, larvae, and juvenile haddock southeastward toward the Norwegian trench and the Skagerrak area (Munk et al., 1999, Sundby et al., 2017). As the larvae oriented toward the magnetic northwest, it is possible that the magnetic orientation direction observed in this study serves as an innate mechanism that limits the dispersal of haddock larvae toward the southeast (as would be the case if they drifted passively with the current). This orientation behavior could also play an important role at the western boundaries of the Norwegian trench, where a spawning area of North Sea haddock is located (Munk et al., 1999). Here, the circulation differs from the rest of the North Sea as the current flows to the north (Sundby et al., 2017) in the form a narrow jet of less saline water coming from the Baltic, known as the Norwegian Coastal Current (Mork, 1981). This current flows along the western coast of Norway and exits the basin following the Norwegian coast up to the Barents Sea. Magnetic orientation to the northwest could help haddock larvae to exit the western boundary of the Norwegian trench, where larvae would drift north and possibly disperse out of the basin. This possibility is further supported by simulations of larval dispersal showing that orientation behavior significantly affects dispersal at the boundaries of the Norwegian current (Fiksen et al., 2007, Vikebø et al., 2007).

Although haddock undertake migrations from the feeding to the spawning grounds, the distance that they cover during their life cycle is still fairly limited compared with other pelagic fish (e.g., herring) (Daan et al., 1990). Thus, behavioral mechanisms such as magnetic-based orientation during the early life stages might play a role in the distribution of this species, as this would help retention in the northern area of the North Sea where this species is most abundant (Albert, 1994). However, the orientation direction of haddock larvae could vary depending on the stocks and local populations. It is possible that populations from different areas of the North Atlantic display different magnetic orientation directions. Indeed, haddock may adapt to local oceanographic conditions, as orientation to the northwest could be beneficial in the North Sea, but this might not be the case for haddock from other regions. These scenarios should be explored experimentally in future work by testing the orientation behavior of haddock from different areas and stocks. Moreover, the role of orientation behavior during the dispersal phase should also be tested using biophysical modeling that incorporates the swimming and orientation behavior.

As adult haddock in the Norwegian Deep and other areas of the North Sea undertake spawning migrations (Albert, 1994), a magnetic-compass-based orientation could be important in the journey toward the spawning areas and back. Whether haddock conserve a compass-based magnetic orientation from the larval stage through adulthood is unknown. Future work will investigate whether adult haddock display the same abilities as larvae.

Limitations of the Study

In the present study, the orientation behavior was not compared between different populations of haddock. The behavior described here might vary according to the different populations and geographical areas. Furthermore, we used the age of the larvae and the temperature at which they were reared as an indirect indicator of larval growth. However, we did not record larval length, which is a more direct measure of larval growth.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Michal Rejmer and Stig Ove Utskot for culture and maintenance of the fish.

Funding for C.B.P., A.C., and M.A.F.: NSF-OCE # 1459156 to CBP. A.C. was also funded by the C.B.P. Lab at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science of the University of Miami. The DISC was developed from NSF-OTIC #1155698 to C.B.P. A.C.'s travel to Austevoll, Norway, and living and accommodation expenses while there were funded by the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research’s (IMR) project “Fine-scale interactions in the plankton” (project # 81529) to H.I.B. The research reported in this article was co-funded by a grant from the Research Council of Norway through the project, “In situ swimming and orientation ability of larval cod and other plankton” (project # 234338/E40) to H.I.B., F.B.V., and C.B.P. (as a visiting researcher) and by the IMR project # 81529.

Author Contributions

A.C. designed the study; collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data; and wrote the paper; C.B.P. designed the study; collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data; wrote the paper; and funded the research; M.A.F. analyzed and interpreted the data; C.M.D. designed the study, collected and interpreted the data; S.D.S. collected and analyzed the data; CJ.E.O. collected and analyzed the data; F.B.V. interpreted the data, wrote the paper, and funded the research; A.B.S. designed the study, collected and interpreted the data, wrote the paper, and funded the research; H.I.B. designed the study, collected and interpreted the data, wrote the paper, and funded the research.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Published: September 27, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.001.

Supplemental Information

The experimental group is also reported (in situ/MagLab).

References

- Albert O. Ecology of haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus L.) in the Norwegian deep. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1994;51:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Auditore P.J., Lough R.G., Broughton E.A. NAFO Science Council Studies; 1994. A Review of the Comparative Development of Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua L.) and Haddock (Melanogrammus Aeglefinus L.) Based on an Illustrated Series of Larvae and Juveniles from Georges Bank, 20. pp. 7–18.https://archive.nafo.int/open/studies/s20/auditore.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Berenshtein I., Kiflawi M., Shashar N., Wieler U., Agiv H., Paris C.B. Polarized light sensitivity and orientation in coral reef fish post-Larvae. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstad O.A., Jørgensen T., Dragesund O. Life history and ecology of the gadoid resources of the Barents Sea. Fish. Res. 1987;5:119–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bottesch M., Gerlach G., Halbach M., Bally A., Kingsford M.J., Mouritsen H. A magnetic compass that might help coral reef fish larvae return to their natal reef. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:R1266–R1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresci A., Paris C.B., Durif C.M.F., Shema S., Bjelland R.M., Skiftesvik A.B., Browman H.I. Glass eels (Anguilla anguilla) have a magnetic compass linked to the tidal cycle. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:1–9. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daan N., Bromley P.J., Hislop J.R.G., Nielsen N.A. Ecology of North Sea fish. Neth. J. Sea Res. 1990;26:343–386. [Google Scholar]

- Durif C.M.F., Browman H.I., Phillips J.B., Skiftesvik A.B., Vøllestad L.A., Stockhausen H.H. Magnetic compass orientation in the European Eel. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faillettaz R., Blandin A., Paris C.B., Koubbi P., Irisson J.-O. Sun-compass orientation in Mediterranean fish larvae. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faillettaz R., Durand E., Paris C.B., Koubbi P., Irisson J.O. Swimming speeds of Mediterranean settlement-stage fish larvae nuance Hjort’s aberrant drift hypothesis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018;63:509–523. [Google Scholar]

- Faria A., Ojanguren A., Fuiman L., Gonçalves E. Ontogeny of critical swimming speed of wild-caught and laboratory-reared red drum Sciaenops ocellatus larvae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009;384:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fiksen Ø., Jørgensen C., Kristiansen T., Vikebø F., Huse G. Linking behavioural ecology and oceanography: larval behaviour determines growth, mortality and dispersal. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007;347:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty M.J., Murawski S.A. Large-scale disturbance and the structure of marine systems: fishery impacts on georges bank. Ecol. Appl. 1998;8:S6–S22. [Google Scholar]

- Foretich M.A., Paris C.B., Grosell M., Stieglitz J.D., Benetti D.D. Dimethyl sulfide is a chemical attractant for reef fish Larvae. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02675-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath M.R., Gallego A. Bio-physical modelling of the early life stages of haddock, Melanogrammus aeglefinus, in the North Sea. Fish. Oceanogr. 1998;7:110–125. [Google Scholar]

- Heessen H.J.L., Daan N., Ellis J.R., editors. Fish Atlas of the Celtic Sea, North Sea, and Baltic Sea. Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hjort J. ICES Rapp. Proc.-Verb.; 1914. Fluctuations in the Great Fisheries of Northern Europe Viewed in the Light of Biological Research; pp. 1–228.http://hdl.handle.net/11250/109177 [Google Scholar]

- Houde E.D. Recruitment variability. In: Jakobsen T., Fogarty M.J., Megrey B.A., Moksness E., editors. Fish Reproductive Biology: Implications for Assessment and Management. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2016. pp. 98–187. [Google Scholar]

- Leis J.M., Carson-Ewart B.M., Hay A.C., Cato D.H. Coral-reef sounds enable nocturnal navigation by some reef-fish larvae in some places and at some times. J. Fish Biol. 2003;63:724–737. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann K.J., Putman N.F., Lohmann C.M.F. Geomagnetic imprinting: a unifying hypothesis of long-distance natal homing in salmon and sea turtles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:19096–19101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801859105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lough R.G., Bolz G.R. The movement of cod and haddock larvae onto the shoals of Georges Bank. J. Fish Biol. 2006;35:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mork M. Circulation phenomena and frontal dynamics of the Norwegian coastal current. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1981;302:635–647. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen H., Atema J., Kingsford M.J., Gerlach G. Sun compass orientation helps coral reef fish larvae return to their natal reef. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munk P., Larsson P., Danielssen D., Moksness E. Variability in frontal zone formation and distribution of gadoid fish larvae at the shelf break in the Northeastern North Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999;177:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- O’connor J., Muheim R. Pre-settlement coral-reef fish larvae respond to magnetic field changes during the day. J. Exp. Biol. 2017;220(Pt 16):2874–2877. doi: 10.1242/jeb.159491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris C.B., Atema J., Irisson J.O., Kingsford M., Gerlach G., Guigand C.M. Reef odor: a wake up call for navigation in reef fish larvae. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris C.B., Cowen R.K. Direct evidence of a biophysical retention mechanism for coral reef fish larvae. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2004;49:1964–1979. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, C.B., Guigand, C.M., Irisson, J., Fisher, R.., 2008. Orientation with No frame of reference ( OWNFOR ): a novel system to observe and quantify orientation in reef fish larvae. Carribbean Connect. Implic. Mar. Prot. Area Manag. NOAA Natl. Mar. Sanctuary Progr. 52–62. 10.1046/j.1467-2960.2001.00053.x. [DOI]

- Petrik C., Kristiansen T., Lough R., Davis C. Prey selection by larval haddock and cod on copepods with species-specific behavior: an individual-based model analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009;396:123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Pope J., Macer C.T. An evaluation of the stock structure of North Sea cod, haddock, and whiting since 1920, together with a consideration of the impacts of fisheries and predation effects on their biomass and recruitment. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1996;53:1157–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Putman N.F., Lohmann K.J., Putman E.M., Quinn T.P., Klimley A.P., Noakes D.L.G. Evidence for geomagnetic imprinting as a homing mechanism in Pacific Salmon. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn T.P. Evidence for celestial and magnetic compass orientation in lake migrating sockeye salmon fry. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 1980;137:243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson S., Meekan M., McCauley R., Jeffs A. Attraction of settlement-stage coral reef fishes to reef noise. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004;276:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Sundby S., Kristiansen T., Nash R.D.M., Johannesen T. Dynamic mapping of North Sea spawning: report of the “KINO” project. Fisk. Hav. 2017;2:183. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H. Haddock biology. IV. The haddock of the Northwestern North Sea. Sci. Invest. Fish. Bd. Scotl. 1927;3:20. [Google Scholar]

- Turrell W.R. New hypotheses concerning the circulation of the northern North Sea and its relation to North Sea fish stock recruitment. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1992;49:107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Vikebø F., Jørgensen C., Kristiansen T., Fiksen Ø. Drift, growth, and survival of larval Northeast Arctic cod with simple rules of behaviour. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007;347:207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Werner F.E., Page F.H., Lynch D.R., Loder J.W., Lough R.G., Perry R.I., Greenberg D.A., Sinclair M.M. Influences of mean advection and simple behavior on the distribution of cod and haddock early life stages on Georges Bank. Fish. Oceanogr. 1993;2:43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wright P., Gibb F., Gibb I., Millar C. Reproductive investment in the North Sea haddock: temporal and spatial variation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011;432:149–160. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The experimental group is also reported (in situ/MagLab).