Visual Abstract

Keywords: pathology; systemic lupus erythematosus; glomerulonephritis; humans; lupus nephritis; glomerulonephritis, Membranoproliferative; glomerulonephritis, Membranous; glomerulonephritis, IGA; control groups; kidney; Fluorescent Antibody Technique; biopsy; kidney biopsy; Staining and Labeling

Abstract

Background and objectives

In 2012, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics proposed that lupus nephritis, in the presence of positive ANA or anti-dsDNA antibody, is sufficient to diagnose SLE. However, this “stand-alone” kidney biopsy criterion is problematic because the ISN/RPS classification does not specifically define lupus nephritis. We investigated the combination of pathologic features with optimal sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of lupus nephritis.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Three hundred consecutive biopsies with lupus nephritis and 560 contemporaneous biopsies with nonlupus glomerulopathies were compared. Lupus nephritis was diagnosed if there was a clinical diagnosis of SLE and kidney biopsy revealed findings compatible with lupus nephritis. The control group consisted of consecutives biopsies showing diverse glomerulopathies from patients without SLE, including IgA nephropathy, membranous glomerulopathy, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (excluding C3 GN), and infection-related glomerulonephritis. Sensitivity and specificity of individual pathologic features and combinations of features were computed.

Results

Five characteristic features of lupus nephritis were identified: “full-house” staining by immunofluorescence, intense C1q staining, extraglomerular deposits, combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits, and endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions, each with sensitivity ranging from 0.68 to 0.80 and specificity from 0.8 to 0.96. The presence of at least two, three, or four of the five criteria had a sensitivity of 0.92, 0.8, and 0.66 for the diagnosis of lupus nephritis, and a specificity of 0.89, 0.95, and 0.98.

Conclusions

In conclusion, combinations of pathologic features can distinguish lupus nephritis from nonlupus glomerulopathies with high specificity and varying sensitivity. Even with stringent criteria, however, rare examples of nonlupus glomerulopathies may exhibit characteristic features of lupus nephritis.

Introduction

SLE, with the kidney manifestation lupus nephritis, is a protean disease. The classification scheme for lupus nephritis has evolved significantly since the original World Health Organization classification of lupus nephritis published by Pirani and Pollak in 1975 (1). At present, the most widely accepted classification is the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) classification of lupus nephritis (2,3). The ISN/RPS 2003 classification of lupus nephritis was originally published in 2004 and has recently undergone small modifications (2,3).

In 2012, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC), an international group dedicated to research on SLE, modified the 1997 American College of Rheumatology criteria to diagnose SLE (4). In a sharp departure from the prior classification scheme developed from the initial proposal in 1971, the SLICC group stated, for the first time, that biopsy-confirmed nephritis compatible with SLE according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification of lupus nephritis, in the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) or anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies, is sufficient to diagnose SLE (4,5). However, this stand-alone kidney biopsy criterion is problematic because the ISN/RPS classification only provides the means to classify lupus nephritis in a patient who has been diagnosed with SLE (3,6). In fact, the ISN/RPS classification states that “it is important to realize that the kidney biopsy findings, per se, cannot be used to establish a diagnosis of SLE” (3,6). This conundrum creates the need to examine systematic, well characterized pathologic criteria for optimal diagnosis of lupus nephritis.

Pathologic features typically seen in lupus nephritis include so-called “full-house” staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, and C3, strong staining for C1q, and tissue ANA on immunofluorescence, as well as the presence of extraglomerular immune deposits by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy, and endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions by electron microscopy. The combination of subendothelial and subepithelial deposits is also characteristic of lupus nephritis. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of these features have only been evaluated systematically on a limited basis and, most notably, to differentiate idiopathic membranous glomerulopathy from membranous lupus nephritis (7).

Herein, we systematically evaluate the diagnostic performance of these pathologic features to distinguish lupus nephritis from nonlupus glomerulopathies, and examine the ability and potential pitfalls of using solely pathologic criteria to diagnose lupus nephritis.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Three hundred consecutive kidney biopsies with lupus nephritis, accessioned in the Columbia Renal Pathology Laboratory from January 2016 to December 2017, were reviewed. A patient was considered to have lupus nephritis if (1) there was a clinical diagnosis of SLE or if the clinical history provided fulfilled the 1997 American College of Rheumatology criteria, and (2) kidney biopsy revealed immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis consistent with lupus nephritis. The latter was classified according to the ISN/RPS 2003 classification (2).

For the control group, 560 consecutive native kidney biopsies from the same period with the following pathologic diagnoses were examined: the first 100 biopsies with IgA nephropathy, membranous glomerulopathy, or pauci-immune glomerulonephritis from 2016, and all other glomerulopathies from 2016, including 77 immune complex–mediated membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN; excluding C3 glomerulopathy), 47 infection-related glomerulonephritis, 36 immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis not otherwise specified (NOS), and 25 cases each of antiglomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease, proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposits, fibrillary glomerulonephritis, and C1q nephropathy. For the latter four relatively rare glomerulopathies, additional consecutive samples from 2017 were included to reach a sample size of 25.

A validation cohort of 219 native kidney biopsies from 2013 was obtained in a similar fashion, and consisted of 75 cases of lupus nephritis; 25 cases each of membranous glomerulopathy, IgA nephropathy, and pauci-immune glomerulonephritis; 20 cases of immune complex–mediated MPGN; nine cases of immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis NOS; 12 cases of infection-related glomerulonephritis; and seven cases each of anti-GBM disease, proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposits, fibrillary glomerulonephritis, and C1q nephropathy.

Pathologic Assessments

Repeat kidney biopsies were excluded. All kidney biopsies were processed according to standard techniques for light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. Cases with inadequate tissues for light, immunofluorescence, or electron microscopy were excluded. Cases of membranous glomerulopathy in which immunofluorescence staining for PLA2R was not available were also excluded.

Pathology reports were reviewed for the following features: dominant or codominant immunofluorescence staining for IgG; ≥2+ intensity staining for C1q (scale 0, ±[trace], 1+, 2+, 3+); full-house staining, defined as at least trace staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, and C3 (excluding staining attributed to nonspecific trapping in segmental scars or linear basement membrane staining in patients with diabetes); immunofluorescence or electron microscopic evidence of extraglomerular deposits (with at least trace intensity, in the tubular basement membrane and/or vessels); tissue ANA on immunofluorescence; presence of at least one subendothelial, mesangial, or subepithelial deposits on immunofluorescence or electron microscopy; and endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions. The median number of open glomeruli evaluated by electron microscopy was 3 (interquartile range, 2–4).

Statistical Analyses

Sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) for each feature to discriminate between lupus nephritis (all classes) and nonlupus nephritis, as well as between pure class 5 lupus nephritis and nonlupus membranous glomerulopathy, were computed. The same metrics were computed for selected combinations of these features. 95% confidence intervals for the AUC were computed by bootstrapping (n=2000). Given the low sample size of lupus nephritis class 5 and PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy in the validation cohort (n=13 each), these values were not computed in these patients. All statistical analyses were performed with R (version 3.2.1), using a package “pROC” and “EpiR” (8).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Results

General Characteristics

Demographic and laboratory information are shown in Table 1. There were 300 patients with lupus nephritis and 560 patients without lupus nephritis. Among those with lupus nephritis, 248 were women and 52 were men, and there were 268 women and 292 men without lupus nephritis. Race was unknown in 125 (42%) patients with lupus nephritis and 227 (41%) patients without lupus nephritis. Among those with known race, most patients with lupus nephritis were black (n=80, 27%), followed by white (n=44, 15%), Hispanic (n=36, 12%), and Asian (n=15, 5%). In contrast, most patients without lupus nephritis were white (n=192, 34%), followed by black (n=60, 11%), Hispanic (n=60, 11%), and Asian (n=21, 4%). Patients with lupus nephritis were younger (median age of 34 versus 48 years), more likely to be women (83% versus 48%) and black (27% versus 11%), and less likely to be white (15% versus 34%). Serum ANA and anti–double-stranded DNA antibody were available for 210 and 213 patients with lupus nephritis, and 345 and 151 patients without lupus nephritis. Patients with lupus nephritis were more likely to have positive serum ANA and anti–double-stranded DNA antibody (97% versus 26% for serum ANA and 87% versus 8% for anti–double-stranded DNA antibody).

Table 1.

Demographics and laboratory features of study participants by pathologic diagnosis

| Total (n=860) | Patients with Lupus nephritis (n=300) | Immune Complex–Mediated MPGN (n=77) | Immune Complex–Mediated GN, NOS (n=36) | Infection-Related GN (n=47) | Membranous Glomerulopathy (n=100) | IgA Nephropathy/HSP (n=100) | Pauci-Immune GN (n=100) | Anti-GBM Disease (n=25) | Fibrillary GN (n=25) | C1q Nephropathy (n=25) | Proliferative GN with Monoclonal Ig Deposits (n=25) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||||||||

| Age, year | 48 (31–65) | 34 (26–44) | 63 (51–74) | 61 (30–74) | 57 (46–68) | 60 (50–68) | 40 (30–54) | 69 (54–77) | 64 (46–70) | 63 (59–68) | 33 (18–41) | 61 (55–73) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 344 (60) | 52 (17) | 45 (58) | 19 (53) | 32 (68) | 59 (59) | 62 (62) | 39 (39) | 7 (28) | 8 (32) | 13 (52) | 8 (32) |

| Female | 516 (40) | 248 (83) | 32 (42) | 17 (47) | 15 (32) | 41 (41) | 38 (38) | 61 (61) | 18 (72) | 17 (68) | 12 (48) | 17 (68) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Black | 140 (16) | 80 (27) | 7 (9) | 8 (22) | 5 (11) | 13 (13) | 4 (4) | 6 (6) | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | 8 (32) | 4 (16) |

| White | 236 (27) | 44 (15) | 29 (38) | 7 (19) | 15 (32) | 35 (35) | 36 (36) | 43 (43) | 9 (36) | 9 (36) | 3 (12) | 6 (24) |

| Hispanic | 96 (11) | 36 (12) | 8 (10) | 7 (19) | 2 (4) | 10 (10) | 9 (9) | 13 (13) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 7 (28) | 3 (12) |

| Asian | 36 (4) | 15 (5) | 3 (4) | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 8 (8) | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) |

| Unknown | 352 (41) | 125 (42) | 30 (39) | 12 (33) | 24 (51) | 40 (40) | 43 (43) | 37 (37) | 13 (52) | 12 (48) | 6 (24) | 10 (40) |

| Laboratory studies and symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl), n=800 | 1.6 (0.9–3) | 0.93 (0.7–1.55) | 2.01 (1.4–2.75) | 2.1 (1.07–3.69) | 3.7 (2.05–5.75) | 1.2 (0.8–1.86) | 1.7 (1.1–3) | 3.6 (2.1–5.8) | 6.85 (4.36–10.1) | 2.76 (1.6–4) | 1.7 (1.21–3.9) | 1.8 (1.47–2.9) |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.74 m2 via CKD-EPI), n=800 | 42 (18–87) | 81 (45–113) | 30.1 (18–49) | 29 (14–64) | 17 (9.2–34) | 59 (33–90) | 39 (23–75) | 13.0 (8–25) | 6 (4–16) | 20 (14–33) | 47 (21–62) | 31 (17–46) |

| Proteinuria (g/d or g/g), n=676 | 3 (1.3–6) | 2.5 (1.2–5.6) | 3.05 (1.2–7.2) | 3.8 (1.91–8.57) | 2.7 (1.38–4.70) | 5.3 (2.9–10) | 2.4 (1–4) | 1.6 (0.90–3.2) | 1.5 (1–1.98) | 3.25 (1.2–7.75) | 3.85 (1.9–7.5) | 5.15 (3.28–8.90) |

| Serum albumin (g/dl), n=629 | 3 (2.4–3.6) | 2.9 (2.2–3.5) | 2.8 (2.4–3.5) | 3 (2.4–3.6) | 2.5 (2.1–3) | 2.7 (2–3.4) | 3.55 (2.8–3.9) | 3 (2.4–3.5) | 3.05 (2.6–3.3) | 3.6 (3.2–3.7) | 3.35 (2.3–3.8) | 3 (2.6–3.7) |

| Albuminuria by urinalysis available | 459 | 154 | 38 | 23 | 17 | 58 | 54 | 62 | 17 | 11 | 15 | 10 |

| 0 or trace | 18 (4) | 4 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (7) | 6 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) |

| 1+ | 51 (11) | 20 (13) | 2 (5) | 1 (4) | 3 (18) | 3 (5) | 6 (11) | 14 (23) | 2 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 2+ | 115 (25) | 37 (24) | 7 (18) | 6 (26) | 5 (29) | 11 (19) | 19 (35) | 16 (26) | 4 (24) | 3 (27) | 5 (33) | 2 (20) |

| 3+ | 173 (38) | 61 (40) | 15 (39) | 9 (39) | 6 (35) | 22 (38) | 18 (33) | 20 (32) | 7 (41) | 6 (55) | 6 (40) | 3 (30) |

| 4+ | 102 (22) | 32 (21) | 13 (34) | 7 (30) | 2 (12) | 22 (38) | 7 (13) | 6 (10) | 4 (24) | 1 (9) | 4 (27) | 4 (40) |

| Hematuria (present/total available) | 506/663 (76) | 171/219 (78) | 53/62 (85) | 22/30 (73) | 33/36 (92) | 30/73 (41) | 72/85 (85) | 76/82 (93) | 23/23 (100) | 12/20 (60) | 3/19 (16) | 11/14 (79) |

| Edema (present/total available) | 272/554 (49) | 83/193 (43) | 35/53 (66) | 14/22 (64) | 19/27 (70) | 60/82 (73) | 15/65 (23) | 16/50 (32) | 5/12 (42) | 5/16 (31) | 10/17 (59) | 10/17 (59) |

| Positive ANA (positive/total available) | 294/555 (53) | 203/210 (97) | 12/42 (29) | 9/24 (38) | 2/26 (8) | 21/74 (28) | 6/58 (10) | 23/57 (40) | 5/13 (38) | 9/18 (50) | 2/17 (12) | 2/17 (12) |

| Positive anti–double-stranded DNA antibody (positive/total available) | 198/364 (54) | 186/213 (87) | 4/24 (17) | 2/10 (20) | 0/14 (0) | 1/32 (3) | 0/18 (0) | 3/28 (11) | 0/5 (0) | 2/8 (25) | 0/3 (0) | 0/9 (0) |

All data are displayed as median (interquartile range) or N (%). MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; NOS, not otherwise specified; HSP, Henoch–Schönlein purpura; GBM, glomerular basement membrane; CKD-EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody.

Proportion of Pathologic Features in Various Glomerular Diseases

The proportion of kidney biopsies with each pathologic feature, stratified by diagnosis, is shown in Table 2. Of note, almost all lupus nephritis cases had IgG dominance by immunofluorescence (0.98), and the majority of the lupus nephritis cases had intense C1q staining (0.68), full-house staining (0.71), combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits (0.76), extraglomerular deposits (0.79), and endothelial tubuloreticular inclusions (0.80). Of the nonlupus nephritis cases, immune complex–mediated MPGN and immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis NOS most frequently exhibited full-house staining, combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits, tubuloreticular inclusions, extraglomerular deposits, and intense C1q staining, although a subset of these cases may represent yet undiagnosed lupus nephritis (see below).

Table 2.

Proportion of cases with pathologic features in various glomerular diseases

| Diagnosis | No. of Cases | IgG Dominant | C1q ≥2+ | Tubuloreticular Inclusions | Full-House Staininga | Extraglomerular Depositsb | Tissue ANA | Mesangial Deposits | Subendothelial Deposits | Subepithelial Deposits | Subendothelial and Subepithelial Deposits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lupus nephritis | 300 | 0.98 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.79 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.76 |

| All nonlupus GN | 560 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.39 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Immune complex–mediated MPGN | 77 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Immune complex–mediated GN, NOS | 36 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.44 |

| Infection-related GN | 47 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.66 |

| Membranous glomerulopathy | 100 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.14 |

| PLA2R+ | 51 | 1.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| PLA2R– | 49 | 1.00 | 0.1 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0 | 0.55 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 0.22 |

| IgA nephropathy/HSP | 100 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| Pauci-immune GN | 100 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| Anti-GBM disease | 25 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0 | 0.12 | 0 |

| Fibrillary GN | 25 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0 | 1.00 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 |

| C1q nephropathy | 25 | 0.12 | 0.88 | 0 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 |

| Proliferative GN with monoclonal Ig deposits | 25 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.36 |

ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; MPGN, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis; NOS, not otherwise specified; PLA2R, phospholipase A2 receptor; HSP, Henoch–Schönlein purpura; Anti-GBM disease, antiglomerular basement membrane disease.

Defined as at least trace staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, and C3 on a scale of 0–3.

By immunofluorescence with at least trace intensity or electron microscopy.

In other disease categories, IgG dominance was also seen in all cases of anti-GBM disease, membranous glomerulopathy, fibrillary glomerulonephritis, and proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposits. Full-house staining was also seen relatively frequently in C1q nephropathy and both PLA2R-positive and negative membranous glomerulopathy. Strong C1q staining was seen by definition in C1q nephropathy (0.88), as well as in fibrillary glomerulonephritis (0.20) and proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposits (0.28). Combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits were also common in infection-related glomerulonephritis (0.66), PLA2R-negative membranous glomerulopathy (0.22), and proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal Ig deposits (0.36).

The proportion of kidney biopsies with each pathologic feature, stratified by class of lupus nephritis, is provided in Table 3. Although mesangial deposits were seen in nearly all classes, other evaluated features were found most commonly in classes 3 and 5, 4, and 4 and 5 rather than 3, and less frequently in classes 1 and 2, although the sample sizes for these cases were small. Of note, 68% of cases classified as pure lupus nephritis class 3 and 83% with pure lupus nephritis class 4 contained subepithelial deposits; in these cases, the subepithelial deposits were present in <50% of the GBM in <50% of glomeruli and as such, the additional designation of lupus nephritis class 5 was not warranted.

Table 3.

Proportion of cases with pathologic features by lupus classes

| Diagnosis | No. of Cases | IgG Dominant | C1q ≥2+ | Tubuloreticular Inclusions | Full-House Staininga | Extraglomerular Depositsb | Tissue ANA | Mesangial Deposits | Subendothelial Deposits | Subepithelial Deposits | Subendothelial and Subepithelial Deposits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 2 | 8 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

| 3 | 41 | 0.95 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.68 | 0.63 |

| 3+5 | 69 | 0.99 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.86 |

| 4 | 69 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.78 |

| 4+5 | 55 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| 5 | 54 | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.13 | 0.98 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.59 |

ANA, anti-nuclear antibody.

Defined as at least trace intensity staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, and C3 on a scale of 0–3.

By immunofluorescence with at least trace intensity or electron microscopy.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Pathologic Features to Distinguish between Lupus Nephritis and Nonlupus Nephritis

Sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values of the individual features to distinguish between lupus nephritis and nonlupus nephritis, and to separate pure lupus nephritis class 5 from PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy, are shown in Supplemental Table 1 and Table 4.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of various pathologic features to distinguish lupus nephritis from nonlupus nephritis

| Features | No. of Lupus Nephritis Cases with Features | No. of Lupus Nephritis Cases without Features | No. of Nonlupus Nephritis Cases with Features | No. of Nonlupus Nephritis Cases without Features | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Area Under the Curve (95% CI) | Positive Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Negative Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant or c-dominant staining for IgG | 294 | 6 | 265 | 295 | 0.98 (0.96 to 0.99) | 0.53 (0.49 to 0.57) | 0.75 (0.73 to 0.78) | 2.07 (1.89 to 2.26) | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.08) | 0.53 (0.48 to 0.57) | 0.98 (0.96 to 0.99) |

| ≥2+ Intensity staining for C1q | 203 | 97 | 67 | 493 | 0.68 (0.62 to 0.73) | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.91) | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.81) | 5.66 (4.46 to 7.17) | 0.37 (0.31 to 0.43) | 0.75 (0.70 to 0.80) | 0.84 (0.80 to 0.86) |

| Full-house staininga | 213 | 87 | 58 | 502 | 0.71 (0.66 to 0.76) | 0.9 (0.87 to 0.92) | 0.80 (0.77 to 0.83) | 6.86 (5.32 to 8.84) | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.39) | 0.79 (0.73 to 0.83) | 0.85 (0.82 to 0.88) |

| Extraglomerular deposits | 238 | 62 | 38 | 522 | 0.79 (0.75 to 0.84) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.89) | 11.69 (8.55 to 15.98) | 0.22 (0.18 to 0.28) | 0.86 (0.82 to 0.90) | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.92) |

| Tissue ANA | 32 | 268 | 1 | 559 | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.14) | 1 (0.99 to 1) | 0.55 (0.54 to 0.57) | 59.73 (8.20 to 434.98) | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.93) | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.00) | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.71) |

| Mesangial deposits | 299 | 1 | 392 | 168 | 1 (0.99 to 1) | 0.3 (0.26 to 0.34) | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.67) | 1.42 (1.35 to 1.50) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.08) | 0.43 (0.40 to 0.47) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.00) |

| Subendothelial deposits | 252 | 48 | 219 | 341 | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.88) | 0.61 (0.57 to 0.65) | 0.73 (0.70 to 0.75) | 2.15 (1.92 to 2.41) | 0.26 (0.20 to 0.34) | 0.54 (0.49 to 0.58) | 0.88 (0.84 to 0.91) |

| Subepithelial deposits | 268 | 32 | 225 | 335 | 0.89 (0.85 to 0.92) | 0.60 (0.56 to 0.64) | 0.75 (0.72 to 0.77) | 2.22 (2.00 to 2.48) | 0.18 (0.13 to 0.25) | 0.54 (0.50 to 0.59) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) |

| Tubuloreticular inclusion | 239 | 61 | 24 | 536 | 0.80 (0.75 to 0.84) | 0.96 (0.94 to 0.97) | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.90) | 18.59 (12.52 to 27.61) | 0.21 (0.17 to 0.27) | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.94) | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.92) |

| Subendothelial and subepithelial deposits | 228 | 72 | 113 | 447 | 0.76 (0.71 to 0.81) | 0.8 (0.76 to 0.83) | 0.78 (0.75 to 0.81) | 3.77 (3.16 to 4.49) | 0.30 (0.24 to 0.37) | 0.67 (0.62 to 0.72) | 0.86 (0.83 to 0.89) |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; ANA, anti-nuclear antibody.

Defined as at least trace intensity staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, and C3 on a scale of 0–3.

By immunofluorescence ≥± intensity or electron microscopy.

Tissue ANA was the single most specific feature for lupus nephritis (specificity =1), but it had the lowest sensitivity (0.11). In contrast, IgG-dominant staining and mesangial deposits had the highest sensitivity (0.98 and 1.00, respectively), but had low specificity (0.53 and 0.3, respectively). The individual criteria of full-house staining, intense C1q staining, tubuloreticular inclusions, extraglomerular deposits, and combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits had specificities ranging between 0.8 and 0.96 and sensitivities ranging between 0.68 and 0.80.

Given the relative paucity of immune staining in pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, we also calculated sensitivity and specificity after excluding the 100 biopsies with pauci-immune glomerulonephritis. Differences in specificity were ≤3%, and sensitivity remained unchanged (data not shown).

Development of Criteria for Lupus Nephritis

There are multiple potential methods to develop diagnostic criteria for lupus nephritis using morphologic features. To develop simple and straightforward criteria in a transparent manner, we chose to take an informed approach using our clinical experience and receiver-operating characteristics analysis.

Given the relatively high sensitivity and specificity of intense C1q staining, full-house staining, extraglomerular deposits, tubuloreticular inclusions, and combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits, we assessed whether we could create a scoring system to define lupus nephritis with high specificity by requiring more than one of these features. The sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values of having one or more of the five features to distinguish lupus nephritis from nonlupus nephritis cases are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Sensitivity and specificity of combination of pathologic features to distinguish lupus nephritis from nonlupus nephritis

| No. of Features Presenta | No. of Lupus Nephritis Cases with Features | No. of Lupus Nephritis Cases without Features | No. of Nonlupus Nephritis Cases with Features | No. of Nonlupus Nephritis Cases without Features | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Area Under the Curve (95% CI) | Positive Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Negative Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One or more | 295 | 5 | 199 | 361 | 0.98 (0.96 to 0.99) | 0.64 (0.60 to 0.68) | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.84) | 2.77 (2.47 to 3.10) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.06) | 0.60 (0.55 to 0.64) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.00) |

| Two or more | 276 | 24 | 62 | 498 | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.95) | 0.89 (0.86 to 0.91) | 0.91 (0.89 to 0.93) | 8.31 (6.56 to 10.53) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.13) | 0.82 (0.77 to 0.86) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.97) |

| Three or more | 240 | 60 | 27 | 533 | 0.8 (0.75 to 0.84) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.97) | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.9) | 16.59 (11.43 to 24.08) | 0.21 (0.17 to 0.26) | 0.90 (0.86 to 0.93) | 0.90 (0.87 to 0.92) |

| Four or more | 197 | 103 | 9 | 551 | 0.66 (0.6 to 0.71) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | 0.82 (0.79 to 0.85) | 40.86 (21.26 to 78.52) | 0.35 (0.30 to 0.41) | 0.96 (0.92 to 0.98) | 0.84 (0.81 to 0.87) |

| Five | 111 | 189 | 4 | 556 | 0.37 (0.31 to 0.43) | 0.99 (0.98 to 1) | 0.68 (0.66 to 0.71) | 51.80 (19.29 to 139.07) | 0.63 (0.58 to 0.69) | 0.97 (0.91 to 0.99) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.78) |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Lupus nephritis can be distinguished from nonlupus nephritis immune complex–mediated GN by presence of some of the following features: (1) intense C1q staining: defined as ≥2 on a scale of 0–3; (2) full-house staining: defined as ≥± intensity staining for IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, and C3 on a scale of 0–3; (3) extraglomerular deposits (with at least trace intensity by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy); (4) presence of both subendothelial and subepithelial deposits by immunofluorescence or electron microscopy; and (5) tubuloreticular inclusion.

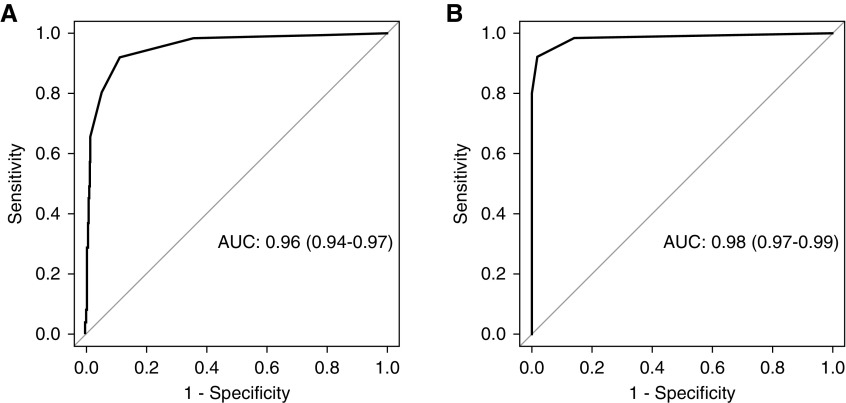

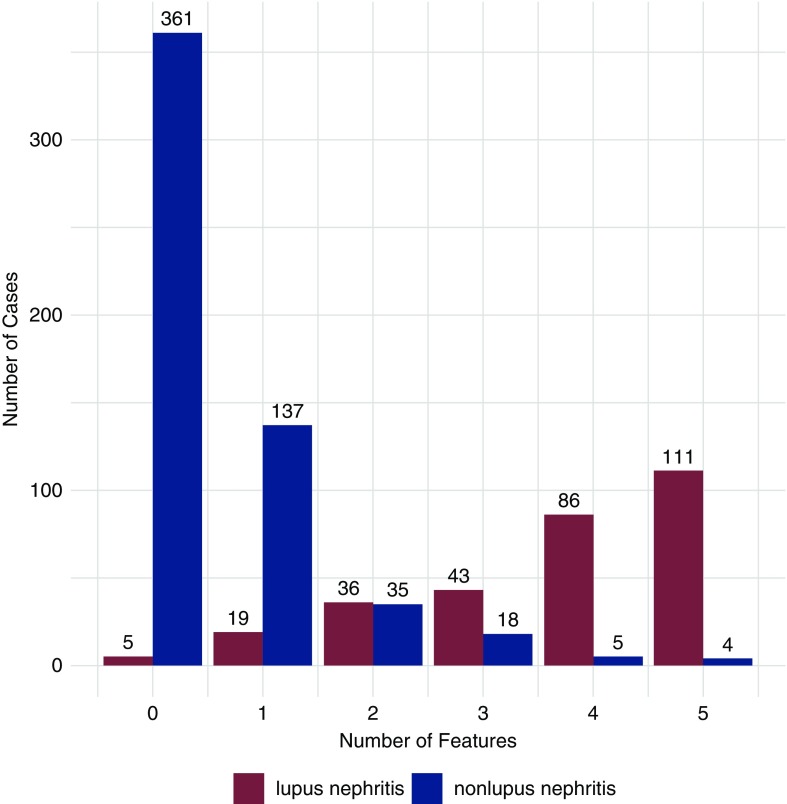

The receiver-operating characteristics curve for five features to distinguish between lupus nephritis and nonlupus nephritis is shown in Figure 1A. The AUC was 0.96 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.94 to 0.97). The number of lupus nephritis and nonlupus nephritis biopsies that met each number of criteria (0–5) are provided in Figure 2. The presence of at least three of five features had a sensitivity of 0.80 and specificity of 0.95, with an AUC of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.85 to 0.9). With four or five features, specificity increased to 0.98 and 0.99 and sensitivity decreased to 0.66 and 0.37, respectively. These values changed by ≤2%, and sensitivity remain unchanged after exclusion of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis (data not shown). IgG dominance and tissue ANA did not improve the performance of the system appreciably, likely because of low specificity and sensitivity, respectively. These findings were validated in a similarly constructed cohort (n=219) comprising 75 lupus nephritis cases and 144 nonlupus nephritis cases (Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver-operating characteristics curves to distinguish lupus nephritis and nonlupus glomerulopathies (A) and lupus nephritis class 5 and PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy (B).

Figure 2.

Number of features present in biopsies from patients with lupus nephritis and nonlupus glomerulopathies. The five features considered are: (1) intense C1q staining, (2) full-house staining, (3) extraglomerular deposits, (4) tubuloreticular inclusions, and (5) combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits.

Use of Criteria to Distinguish between Class 5 Lupus Nephritis and PLA2R-Positive Membranous Glomerulopathy

The receiver-operating characteristics curve for five features to distinguish between lupus nephritis class 5 and PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy is shown in Figure 1B. The AUC was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.97 to 0.99). Sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values of the above criteria to distinguish between pure lupus nephritis class 5 and PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy are also provided in Supplemental Table 3. Under this more restricted setting, the presence of at least one of the five features showed sensitivity of 0.94 and specificity of 0.86, with an AUC of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.85 to 0.96). The presence of at least two of the five features had a sensitivity of 0.83 and specificity of 0.98, with an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.85 to 0.96). When at least three of five features was used as the cutoff, the specificity was 1 and the sensitivity was 0.69.

Nonlupus Nephritis Cases with Three or More Features

Among the biopsies from patients without lupus nephritis, 27 of 560 (5%) satisfied at least three of five criteria, including 11 cases of immune complex–mediated MPGN, eight cases of immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis NOS, five cases of PLA2R negative membranous glomerulopathy, two cases of infection-related glomerulonephritis, and one case of fibrillary glomerulonephritis (Figure 2). Among the 27 patients, serum ANA was positive in seven, negative in 12, and unavailable in eight patients; anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies were available in six patients and all were negative. In ten of the 27 biopsies, pathologists were highly suspicious for lupus nephritis. The remaining 17 cases included four with hepatitis C virus (HCV)–associated immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis, two IgM-dominant immune complex–mediated MPGN in the setting of low-grade lymphoma, two infection-related glomerulonephritis, one fibrillary glomerulonephritis, and eight of unclear cause (although a suspicion for lupus nephritis was raised in multiple cases). Of note, the two IgM-dominant immune complex–mediated MPGN cases with low-grade lymphoma had positive serum ANA. Importantly, the presence of biopsies that clearly represent nonlupus nephritis glomerulopathies but still meet three or more of the five criteria, including rare cases with a positive ANA, clearly demonstrate that pathologic criteria, in isolation, are not completely specific for lupus nephritis.

Lupus Nephritis Cases with Two or Less Features

Among the biopsies from patients with lupus nephritis, 24 of 300 (8%) satisfied less than two of the five criteria (Figure 2), including two biopsies with lupus nephritis class 1, one with lupus nephritis class 2, seven with lupus nephritis class 3, two with lupus nephritis class 3 and 5, three with lupus nephritis class 4, and nine with lupus nephritis class 5. Not surprisingly, 21 of these 24 biopsies had low National Institute of Health activity index scores, ranging from 0 to 3 (scale, 0–24). Two of the remaining three cases had features of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis with scant deposits, and the remaining biopsy showed lupus nephritis class 4 with a chronicity index of 10.

Discussion

Lupus nephritis encompasses a spectrum of glomerular, tubulointerstitial, and vascular changes occurring in patients with SLE. Despite its protean manifestations, some pathologic features of lupus nephritis are felt to be characteristic enough to allow authors to apply the term “lupus-like” to describe diverse entities including cases of apparently kidney-limited SLE, HIV-associated immune complex disease of the kidney, and even some cases of glomerulonephritis associated with HCV infection (9–19). However, the pathologic features used to label these cases as lupus-like are highly variable, reflecting a lack of formal criteria to diagnose lupus nephritis. With the introduction of the 2012 SLICC stand-alone kidney biopsy criterion, there is now a heightened desire to define pathologic criteria for lupus nephritis (4,6).

In this study, we examined diagnostic performances of multiple pathologic features to distinguish lupus nephritis from a control group that includes a variety of glomerular diseases (Tables 2, 4, and 5). We identified five pathologic findings with reasonably high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of lupus nephritis: (1) intense C1q staining, (2) full-house staining, (3) extraglomerular deposits, (4) tubuloreticular inclusions, and (5) combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits. Furthermore, we demonstrated progressively greater specificity, with declining but still acceptable sensitivity, for combinations of these findings. Specifically, the presence of two, three, or four of the five criteria carried a specificity of 0.89, 0.95, and 0.98 for the diagnosis of lupus nephritis, respectively, with a sensitivity of 0.92, 0.8, and 0.66, respectively. This data has the potential to form the basis for the development of SLICC kidney biopsy stand-alone criteria to diagnose lupus nephritis. Given the clinical consequence of a diagnosis of SLE by kidney stand-alone criteria, the threshold to diagnosis lupus nephritis in the absence of clinically established SLE should be sufficiently high. To date, only one study assessed the utility of the SLICC stand-alone kidney biopsy criteria to diagnose SLE (20). This study used full-house staining as the sole criteria which, not surprisingly, had a low specificity. This is because full-house staining can be seen in well defined entities distinct from lupus nephritis, including, but not limited to, HCV-associated immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis, membranous glomerulopathy, IgA nephropathy, and C1q nephropathy (Table 1). Validation and investigation of appropriate thresholds to define lupus nephritis using our more stringent pathologic criteria in an independent cohort are warranted to better define kidney biopsy stand-alone SLICC criteria. Importantly, even with stringent criteria, rare examples of nonlupus glomerulopathies may exhibit characteristic features of lupus nephritis.

It should be noted that some lupus nephritis biopsies did not routinely fulfill our proposed criteria, namely pure class 5 lupus nephritis, lupus nephritis with low modified National Institute of Health activity index, and cases of class 3 or 4-S with features more typical of pauci-immune glomerulonephritis (21). In the setting where the differential diagnosis is limited to lupus nephritis class 5 versus PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy, the number of features required to obtain a high degree of specificity is lower; in this situation, the presence of only two of the five features had a specificity of 0.98. These results are similar to the findings from a seminal study that predates the discovery of PLA2R (7).

Conversely, nearly 5% of the nonlupus nephritis glomerulopathies fulfilled three of the five criteria for lupus nephritis. Some of these patients may have a forme fruste of SLE, may meet criteria for SLE in the future, and have been variably referred to as “lupus-like nephritis” or “full-house nephropathy” in the literature (11–19). Such cases are highly heterogeneous. Although the presence of three or more features strongly suggests a diagnosis of lupus nephritis and warrants a close follow-up for signs and symptoms of SLE, these cases should not be diagnosed with lupus nephritis pending further validation in independent cohorts. This point is further emphasized by the observation that we have identified three or more of the five criteria in rare cases of other well defined nonlupus nephritis glomerulopathies, including HCV-associated immune complex–mediated glomerulonephritis, IgM-dominant MPGN in the setting of low-grade lymphoma, fibrillary glomerulonephritis, and infection-related glomerulonephritis. It should be emphasized that proper pathologic diagnosis requires critical evaluation of all available clinical, laboratory, and pathologic information, and not simply the rote application of pathologic criteria.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the clinical diagnosis of SLE was made by the referring rheumatologist or nephrologist and could not be independently verified. Although the American College of Rheumatology criteria were used to diagnose SLE, we could not ensure that the criteria were applied in a uniform manner. Second, morphologic evaluation was not performed in a blinded fashion, which may have inflated the specificity. We believe, however, that withholding the diagnosis of SLE would not reduce this bias because kidney biopsy findings alone would strongly suggest a diagnosis of SLE (4). In contrast, the likely presence of forme fruste lupus nephritis in the nonlupus nephritis group had the contrasting effect of potentially deflating the specificity. Third, the nonlupus nephritis control group was suboptimal in that it contained glomerulonephritides that are easily distinguishable from lupus nephritis. Because this study is retrospective, our findings and any proposed criteria should be validated in another cohort. It also should be noted that electron microscopy is not available in many kidney pathology laboratories outside of the United States. That said, four of the five criteria examined in this study can be identified in the absence of electron microscopy, with the sole exception of tubuloreticular inclusions. Finally, although positive and negative predictive values are provided, these numbers are not emphasized because our cohort is intentionally enriched in patients with lupus nephritis, and therefore may not be applicable to a real-world clinical setting because of over- and underestimation of positive and negative predictive values, respectively.

In conclusion, we have provided data on five kidney biopsy findings that have reasonably high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of lupus nephritis (≥2+ intensity staining for C1q, full-house staining, extraglomerular deposits, combined subendothelial and subepithelial deposits, and tubuloreticular inclusions). When three of more of the five criteria are met, the specificity for the diagnosis of lupus nephritis is 0.95, and it increases to 0.98 with four criteria. The progressive increase in specificity is met with an expected decline in sensitivity. Although these findings may form the basis for the development of SLICC stand-alone kidney biopsy criteria for the diagnosis of lupus nephritis, we have demonstrated that exceptions exist and, as such, clinical judgment is needed to avoid an erroneous diagnosis of SLE.

Disclosures

Dr. Bomback, Dr. D’Agati, Dr. Kudose, Dr. Markowitz, Dr. Santoriello, and Dr. Stokes have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Bomback was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant R01MD009223.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01570219/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Sensitivity and specificity of various pathologic features to distinguish pure class 5 lupus nephritis from PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy.

Supplemental Table 2. Sensitivity and specificity of combination of pathologic features to distinguish lupus nephritis from nonlupus nephritis in a validation cohort (N=219).

Supplemental Table 3. Sensitivity and specificity of combination of pathologic features to distinguish pure class 5 lupus nephritis from PLA2R-positive membranous glomerulopathy.

Supplemental Figure 1. Receiver-operating characteristics curves to distinguish lupus nephritis and nonlupus glomerulopathies in the validation cohort.

References

- 1.McCluskey RT: Lupus nephritis. In: Kidney Pathology Decennial 1966 – 1975, edited by Sommers SC, East Norwalk, CT, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1975, pp 435–450 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajema IM, Wilhelmus S, Alpers CE, Bruijn JA, Colvin RB, Cook HT, D’Agati VD, Ferrario F, Haas M, Jennette JC, Joh K, Nast CC, Noël LH, Rijnink EC, Roberts ISD, Seshan SV, Sethi S, Fogo AB: Revision of the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society classification for lupus nephritis: Clarification of definitions, and modified National Institutes of Health activity and chronicity indices. Kidney Int 93: 789–796, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, Balow JE, Bruijn JA, Cook T, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Ginzler EM, Hebert L, Hill G, Hill P, Jennette JC, Kong NC, Lesavre P, Lockshin M, Looi LM, Makino H, Moura LA, Nagata M: The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 241–250, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, Bruce IN, Isenberg D, Wallace DJ, Nived O, Sturfelt G, Ramsey-Goldman R, Bae SC, Hanly JG, Sánchez-Guerrero J, Clarke A, Aranow C, Manzi S, Urowitz M, Gladman D, Kalunian K, Costner M, Werth VP, Zoma A, Bernatsky S, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Khamashta MA, Jacobsen S, Buyon JP, Maddison P, Dooley MA, van Vollenhoven RF, Ginzler E, Stoll T, Peschken C, Jorizzo JL, Callen JP, Lim SS, Fessler BJ, Inanc M, Kamen DL, Rahman A, Steinsson K, Franks AG Jr., Sigler L, Hameed S, Fang H, Pham N, Brey R, Weisman MH, McGwin G Jr., Magder LS: Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 64: 2677–2686, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canoso JJ, Cohen AS: A review of the use, evaluations, and criticisms of the preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 22: 917–921, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stokes MB, D’Agati VD: Full-house glomerular deposits: Beware the sheep in wolf’s clothing. Kidney Int 93: 18–20, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennette JC, Iskandar SS, Dalldorf FG: Pathologic differentiation between lupus and nonlupus membranous glomerulopathy. Kidney Int 24: 377–385, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, Müller M: pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 77, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sise ME, Wisocky J, Rosales IA, Chute D, Holmes JA, Corapi KM, Babitt JL, Tangren JS, Hashemi N, Lundquist AL, Williams WW, Mount DB, Andersson KL, Rennke HG, Smith RN, Colvin R, Thadhani RI, Chung RT: Lupus-like immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection treated with oral, interferon-free, direct-acting antiviral therapy. Kidney Int Rep 1: 135–143, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas M, Kaul S, Eustace JA: HIV-associated immune complex glomerulonephritis with “lupus-like” features: A clinicopathologic study of 14 cases. Kidney Int 67: 1381–1390, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baskin E, Agras PI, Menekşe N, Ozdemir H, Cengiz N: Full-house nephropathy in a patient with negative serology for lupus. Rheumatol Int 27: 281–284, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gianviti A, Barsotti P, Barbera V, Faraggiana T, Rizzoni G: Delayed onset of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with “full-house” nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol 13: 683–687, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maziad ASA, Torrealba J, Seikaly MG, Hassler JR, Hendricks AR: Renal-limited “lupus-like” nephritis: How much of a lupus? Case Rep Nephrol Dial 7: 43–48, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirkle JL, Freedman BI, Fogo AB: Immune complex disease with a lupus-like pattern of deposition in an antinuclear antibody-negative patient. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 159–164, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rijnink EC, Teng YK, Kraaij T, Wolterbeek R, Bruijn JA, Bajema IM: Idiopathic non-lupus full-house nephropathy is associated with poor renal outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 654–662, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simmons SC, Smith ML, Chang-Miller A, Keddis MT: Antinuclear antibody-negative lupus nephritis with full house nephropathy: A case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 42: 451–459, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Touzot M, Terrier CS, Faguer S, Masson I, François H, Couzi L, Hummel A, Quellard N, Touchard G, Jourde-Chiche N, Goujon JM, Daugas E; Groupe Coopératif sur le Lupus Rénal (GCLR) : Proliferative lupus nephritis in the absence of overt systemic lupus erythematosus: A historical study of 12 adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 96: e9017, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen YK, Chen ML: Clinicopathological study of originally non-lupus “full-house” nephropathy. Ren Fail 32: 1025–1030, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huerta A, Bomback AS, Liakopoulos V, Palanisamy A, Stokes MB, D’Agati VD, Radhakrishnan J, Markowitz GS, Appel GB: Renal-limited ‘lupus-like’ nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2337–2342, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rijnink EC, Teng YKO, Kraaij T, Dekkers OM, Bruijn JA, Bajema IM: Validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria in a cohort of patients with full house glomerular deposits. Kidney Int 93: 214–220, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner-Stokes T, Wilson HR, Morreale M, Nunes A, Cairns T, Cook HT, Pusey CD, Tarzi RM, Lightstone L: Positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody serology in patients with lupus nephritis is associated with distinct histopathologic features on renal biopsy. Kidney Int 92: 1223–1231, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.