Historical issues with genetic manipulation of Chlamydia have prevented rigorous functional genetic characterization of the ∼1,000 genes in chlamydial genomes. Here, we report the development of a transposon mutagenesis system for C. muridarum, a mouse-adapted Chlamydia species that is widely used for in vivo investigations of chlamydial pathogenesis. This advance builds on the pioneering development of this system for C. trachomatis. We demonstrate the generation of an initial library of 33 mutants containing stable single or double transposon insertions. Using these mutant clones, we characterized in vitro phenotypes associated with genetic disruptions in glycogen biosynthesis and three polymorphic outer membrane proteins.

KEYWORDS: Chlamydia muridarum, glycogen, pmp, transposon mutagenesis

ABSTRACT

Functional genetic analysis of Chlamydia has been a challenge due to the historical genetic intractability of Chlamydia, although recent advances in chlamydial genetic manipulation have begun to remove these barriers. Here, we report the development of the Himar C9 transposon system for Chlamydia muridarum, a mouse-adapted Chlamydia species that is widely used in Chlamydia infection models. We demonstrate the generation and characterization of an initial library of 33 chloramphenicol (Cam)-resistant, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing C. muridarum transposon mutants. The majority of the mutants contained single transposon insertions spread throughout the C. muridarum chromosome. In all, the library contained 31 transposon insertions in coding open reading frames (ORFs) and 7 insertions in intergenic regions. Whole-genome sequencing analysis of 17 mutant clones confirmed the chromosomal locations of the insertions. Four mutants with transposon insertions in glgB, pmpI, pmpA, and pmpD were investigated further for in vitro and in vivo phenotypes, including growth, inclusion morphology, and attachment to host cells. The glgB mutant was shown to be incapable of complete glycogen biosynthesis and accumulation in the lumen of mutant inclusions. Of the 3 pmp mutants, pmpI was shown to have the most pronounced growth attenuation defect. This initial library demonstrates the utility and efficacy of stable, isogenic transposon mutants for C. muridarum. The generation of a complete library of C. muridarum mutants will ultimately enable comprehensive identification of the functional genetic requirements for Chlamydia infection in vivo.

IMPORTANCE Historical issues with genetic manipulation of Chlamydia have prevented rigorous functional genetic characterization of the ∼1,000 genes in chlamydial genomes. Here, we report the development of a transposon mutagenesis system for C. muridarum, a mouse-adapted Chlamydia species that is widely used for in vivo investigations of chlamydial pathogenesis. This advance builds on the pioneering development of this system for C. trachomatis. We demonstrate the generation of an initial library of 33 mutants containing stable single or double transposon insertions. Using these mutant clones, we characterized in vitro phenotypes associated with genetic disruptions in glycogen biosynthesis and three polymorphic outer membrane proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis impose a heavy burden on public health throughout the world. C. trachomatis is the most common cause of bacterial sexually transmitted disease and has the highest incidence of all reportable infections (1, 2). A long-sought goal of the field is to obtain a global functional genomic understanding of the specific roles Chlamydia genes play in infection and pathogenesis. Historically, these efforts have been hampered by a general lack of experimental systems for genetic manipulation of Chlamydia species. A series of advances made over the past 5 to 10 years, however, have begun to reduce these limitations (3, 4). Highlighted discoveries include the development of a stable system for genetic transformation through a shuttle vector (5), an inducible gene expression system (6), intron-based targeted gene inactivation (7), interspecies lateral gene transfer (8–10), recombination-based gene replacement (11), and forward genetics using chemically mutagenized Chlamydia bacteria (12–14). These new tools have greatly expanded the field’s capabilities for genetic manipulation of Chlamydia. Functional genomic progress has also been limited by restrictions imposed by the obligate intracellular nature of Chlamydia and bottlenecks associated with its biphasic developmental cycle.

Chlamydial developmental growth occurs in mucosal epithelial cells within a pathogen-modified vacuole called an inclusion. From within this niche, Chlamydia hijacks cellular processes necessary for nutrient acquisition and maintaining a favorable replicative environment (15, 16). Chlamydia bacteria manipulate host cell functions with a highly streamlined genome that encodes roughly 900 proteins (17); the portion of these required for chlamydial developmental growth, or for specific Chlamydia-host interactions in either cell culture or in vivo models, is incompletely understood.

A single suicide vector system for transposon mutagenesis in C. trachomatis recently emerged (18). Transposon mutagenesis is an empowering, widely used strategy for generating random, single-gene insertion mutations on a genomic scale that are fixed within a chromosome and easily identified by methods such as PCR (19–21). We predicted that Chlamydia genes that manifest as nonessential for growth in cell culture are maintained in the genome because of selective pressures related to growth in host species. As a first step toward investigating this, we sought to establish an isogenic library of single-gene disruption mutants in the mouse-adapted species C. muridarum. This species is phylogenetically related to C. trachomatis and has been widely used in the field to model immune responses and immunopathology similar to what is found in human infections with C. trachomatis. C. muridarum infection of mice has developed into an excellent model system for the integration of contemporary genetics technologies with the examination of the roles of genes in chlamydial in vivo biology (22–25).

Here, we report the successful development of the Himar transposon system for C. muridarum. We describe the characterization of a library of isogenic mutant strains that can be used to test for virulence determinants in cell culture. We generated an initial library of 33 mutants, each containing 1 or 2 transposon insertions and many of which were genome sequenced to verify their genotypes. Across this library of mutants, a range of in vitro growth phenotypes were exhibited in cell culture. We describe the inability of a glgB transposon mutant to fully synthesize and accumulate glycogen in the inclusion lumen, and we characterize the in vitro defects of 3 mutant strains with transposon insertions in pmp genes—pmpI, pmpA, and pmpD.

RESULTS

Transposon mutagenesis of C. muridarum.

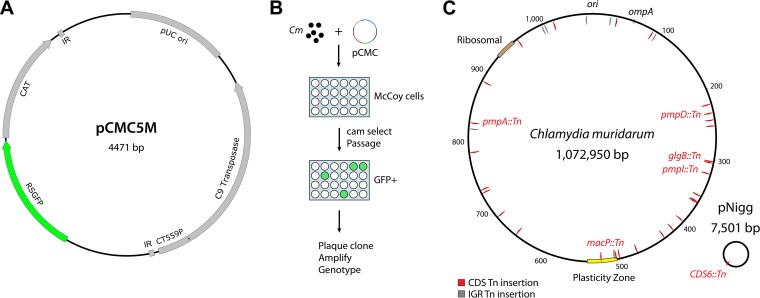

We adapted the Himar transposon system for use in C. muridarum by modifying the nonreplicating vector used previously for introduction of transposon insertions in C. trachomatis L2 (18). Specifically, bla was replaced with gfp-cat (5) to produce pCMC5M (Fig. 1A). This construct allowed chloramphenicol (Cam)-based selection of C. muridarum mutants and screening of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing plaques of Chlamydia-infected cells. Wild-type C. muridarum was transformed with pCMC5M and incubated with McCoy cells grown in multiwell plates for infection, and mutants containing transposon insertions were selected for by using Cam and monitoring of cultures for GFP-expressing bacteria (Fig. 1B). Thirty-three C. muridarum transposon mutants were generated from a total of 10 independent transformation experiments, and the isolated mutant strains were assigned names in numeric order from UWCM001 to UWCM033 (Fig. 1C and Table 1).

FIG 1.

Generation of C. muridarum transposon mutants. (A) Schematic of the pCMC5M plasmid used for transformation, containing the pUC ori, Himar1 C9 transposase, and a transposon with cat-gfp and flanking inverted repeat (IR) sequences. (B) Overview of procedure for generating C. muridarum transposon mutants in McCoy cells. (C) Genome map of transposon insertions in the C. muridarum chromosome and plasmid pNigg. Insertions in coding sequences (CDS) are in red; insertions in intergenic regions (IGR) are in gray. Nucleotide markers on C. muridarum chromosome are expressed in kilobase pairs.

TABLE 1.

Chlamydia muridarum transposon mutants

| Straina | Insert position (TA location)b | Locus | Gene | Protein | % predicted translated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UWCM001 | 242824>25 | TC0206 | Hypothetical protein | 86 | |

| UWCM002 | 785559<60 | TC0657 | pgi | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 30 |

| UWCM003 | 472705>06 | TC0411 | Inc (predicted) | 99 | |

| UWCM004a | 35408>09 | TC0031 | gyrA2 | DNA topoisomerase IV subunit A | 67 |

| UWCM004b | 730561>62 | TC0610 | uvrA | Excinuclease ABC subunit A | 11 |

| UWCM005 | 1018583 | TC0878 | Hypothetical protein | 11 | |

| UWCM006 | 818430<31 | IGR | |||

| UWCM007a | 301598>99 | TC0257 | glgB | 14-Alpha-glucan-branching protein | 86 |

| UWCM007b | 498439>40 | TC0431 | macP | MAC/perforin family protein | 8 |

| UWCM008 | 303619>20 | TC0259 | Hypothetical protein | 90 | |

| UWCM009 | 220664>65 | TC0189 | Hypothetical protein | 77 | |

| UWCM010 | 363126>27 | TC0305 | Hypothetical protein | 80 | |

| UWCM011 | 687198<99 | TC0575 | pknD | Serine/threonine protein kinase | 7 |

| UWCM012 | 827362<63 | TC0693 | pmpA | Outer membrane protein PmpA | 77 |

| UWCM013 | 413657<58 | TC0350 | folD | Bifunctional 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase | 25 |

| UWCM014a | 232911>12 | TC0197 | pmpD | Outer membrane protein PmpD | 67 |

| UWCM014b | 395719<20 | TC0333 | gnd | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 98 |

| UWCM015 | 503579<80 | TC0435 | Phospholipase | 66 | |

| UWCM016 | 505694>95 | IGR | |||

| UWCM017 | 887618<19 | TC0473 | Acetyltransferase | 66 | |

| UWCM018 | 1065355<56 | IGR | |||

| UWCM019 | 319531<32 | TC0267 | pmpI | Outer membrane protein PmpI | 70 |

| UWCM020 | 94501>02 | IGR | |||

| UWCM021 | 26638<39 | IGR | |||

| UWCM022 | 361528< | TC0303 | Hypothetical protein | 0 | |

| 363601c | TC0306 | Hypothetical protein | 70d | ||

| UWCM023a | 524741>42 | TC0438 | Cytotoxin/adherence factor | 86 | |

| UWCM023b | 1001585<86 | IGR | |||

| UWCM024 | 429854<55 | TC0368 | ribF | Bifunctional riboflavin kinase/FMN adenyltransferase | 2 |

| UWCM024 | TC0369 | truB | tRNA pseudouridine synthase B | 98 | |

| UWCM025 | 726016>17 | TC0606 | Exodeoxyribonuclease 7 small subunit | 32 | |

| UWCM026 | 251258<59 | TC0212 | rmuC | DNA recombination protein RmuC homolog | 60 |

| UWCM027 | 301598>99 | TC0257 | glgB | 1,4-Alpha-glucan branching protein | 86 |

| UWCM028 | 1006942<42 | IGR | |||

| UWCM029 | 4770>71e | CDS6 | pNigg CDS6 | 64 | |

| UWCM030 | 641212<13 | TC0530 | Protein phosphatase | 72 | |

| UWCM031 | 358972<73 | TC0302 | recD | ATPase AAA | 86 |

| UWCM032 | 959708<09 | TC0828 | mip | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 15 |

| UWCM033 | 87859<60 | TC0075 | Hypothetical protein | 22 |

a and b indicate two separate transposon insertions.

Genome location on C. muridarum chromosome (NC_002620); > and < indicate the orientation of the gfp-cat transposon in the genome.

Insert occurred with a 2,072-bp deletion beginning at 361529; genes TC0304 and TC0305 were deleted.

Truncation due to transposon insertion occurred at the 3′ end of TC0306.

Genome location on C. muridarum plasmid pMoPn (NC_002182).

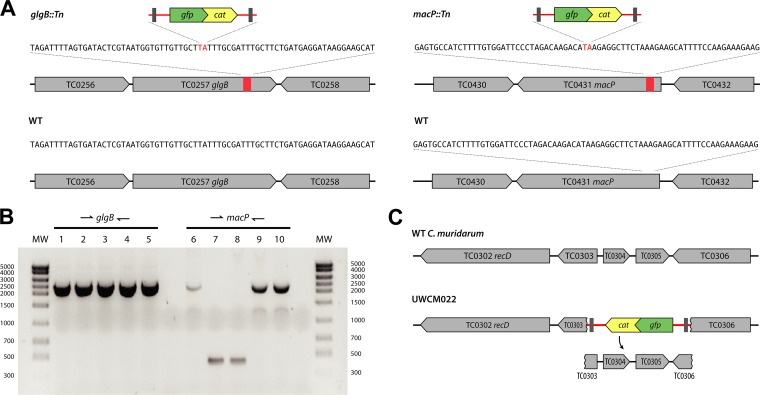

To determine the insertion sites of transposon mutants, genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from C. muridarum mutants and subjected to pyrosequencing using primers designed for sequences immediately inside the 5′ and 3′ ends of the transposed DNA. The sequencing products were analyzed by BLAST to identify candidate genomic insertion sites. For all the mutants, sequencing analysis showed that transposon insertions occurred at TA dinucleotides, with the genomic TA being replaced by the 2,003-bp transposon (Tn) as TA-transposon-TA in either orientation (Fig. 2A). To confirm the genomic locations of transposon insertions, PCR was performed on gDNA isolated from mutant strains, using primers specific to genomic sequences flanking the candidate insertion sites. Analysis showed bands that migrated 2 kb higher than wild-type (WT) C. muridarum parental gDNA lacking transposons (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Transposon insertions in glgB and macP. (A) Chromosomal sequences of insertion sites. (B) PCR analysis of UWCM007 using primers against flanking sequences in genomic DNA. Lanes: 1, UWCM007 (glgB::Tn and macP::Tn); 2, plaque-cloned UWCM007 (glgB::Tn); 3, plaque-cloned UWCM027 (glgB::Tn); 4, plaque-cloned UWCM007 (glgB::Tn and macP::Tn); 5, 2× plaque-cloned UWCM007 (glgB::Tn and macP::Tn); 6, UWCM007 (glgB::Tn and macP::Tn); 7, plaque-cloned UWCM007 (glgB::Tn); 8, plaque-cloned UWCM027 (glgB::Tn); 9, plaque-cloned UWCM007 (glgB::Tn and macP::Tn); 10, 2× plaque-cloned UWCM007 (glgB::Tn and macP::Tn). (C) Schematic showing the deletion of sequences between TC0303 and TC0306 that occurred with the insertion of an intact transposon (red) in mutant clone UWCM022.

Analysis of the transposon insertion frequency in the C. muridarum genome across all 33 mutants characterized during this initial study indicated that insertions occurred randomly over the genome and without notable bias (Fig. 1C). Twenty-five insertions fell within chromosomal coding regions, 7 insertions occurred within intergenic sequences, and 1 insertion was in the C. muridarum plasmid. Three transposon insertions were contained within the C. muridarum plasticity zone, a genomic region that is highly variable among species against an overall background of genomic synteny (26–28). Plasticity zone mutants were obtained for TC0431 macP, a MAC/perforin family protein at the 5′ end of the plasticity zone; in TC0435, a phospholipase family D protein; and in TC0438, the third of three large cytotoxin/adherence factor genes that are variably present and truncated in different chlamydial strains and species (26, 29).

In 4 mutants, two separate transposon insertions occurred (Table 1 [indicated by a and b after the strain name]). Mutants with more than two insertions were not observed. An example of a double-insertion mutant was UWCM007, where genotyping of clonal plaque isolates revealed a subpopulation of mutants with a single insertion (in TC0257 glgB) and a second subpopulation with an identical mutation in TC0257 glgB and a second transposon insertion in TC0431 macP (Fig. 2). These plaque-cloned strains were subsequently reclassified as UWCM007 (insertions in both macP and glgB) and UWCM027 (a single insertion in glgB). In a lone instance (mutant clone UWCM022), transposition was associated with the deletion of approximately 2 kb of genomic DNA adjacent to the insertion, between chromosomal coordinates 361528 and 363601 (Fig. 2C). The deleted genes included TC0303 to TC0306, and the transposed DNA remained intact in this event.

Whole-genome sequence analysis.

Whole-genome sequencing was performed on 17 transposon mutants. Genome sequence analysis revealed that the transposon insertions were intact in these mutants and confirmed that the insertions were at the TA locations indicated by PCR and Sanger sequencing. Whole-genome sequencing of the C. muridarum parent strain used to create the transposon library showed the presence of 41 single nucleotide variants (SNVs) from the reference strain NC_02620 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The C. muridarum parent contained noted variants in the poly(G) tracts of two phospholipase family proteins, TC0436 and TC0447. No additional SNVs or other mutations, for example, compensatory mutations from propagation of transposon mutants, were identified in the transposon mutants.

Stability of transposon insertions in C. muridarum.

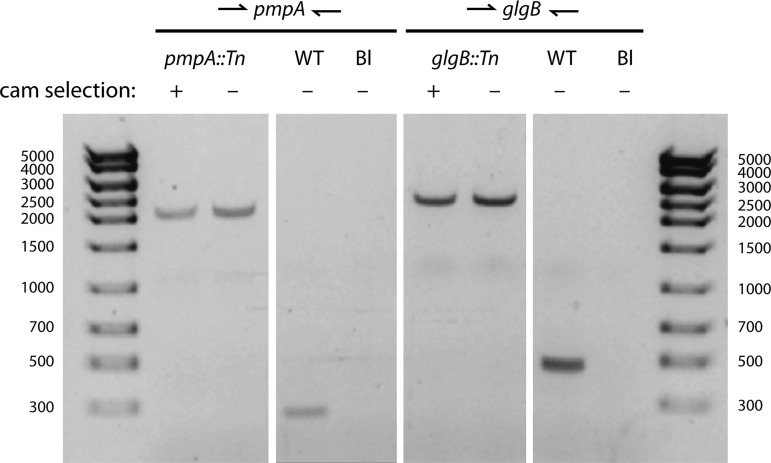

We investigated whether transposon insertions were stable during long-term propagation of mutant strains in the absence of selection. Two plaque-purified transposon mutants, pmpA::Tn and glgB::Tn mutants, were passaged for 10 generations either with or without 0.5 μg/ml Cam. Following serial passage, gDNA was extracted from the mutant strains, and the presence of each transposon insert was analyzed by PCR using primers flanking the insertion sites. PCR analysis showed that high-molecular-weight products—indicating the presence of transposon insertions—were present in the strains regardless of Cam selection (Fig. 3). Furthermore, low-molecular-weight bands were not present, indicating no detectable loss of fragments of the transposed DNA. Thus, the transposon insertions were stable for at least 10 passages, consistent with previous measurements (18).

FIG 3.

Stability of transposon inserts. Two plaque-purified transposon mutants, UWCM012 (pmpA::Tn) and UWCM027 (glgB::Tn), were grown continuously for 10 generations in the presence (+) or absence (−) of 0.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol (cam). Genomic DNA from the passaged strains was extracted and subjected to PCR analysis using primers designed against genomic sequences flanking the transposon inserts. The ∼2-kb bands denote the sizes of transposon inserts.

Requirement for glgB in inclusion glycogen biosynthesis.

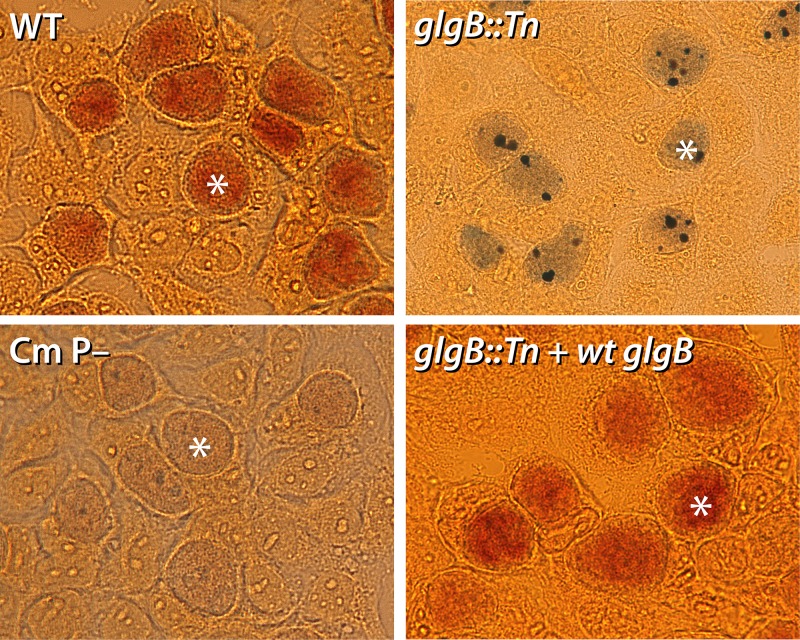

The accumulation of glycogen within inclusions is a hallmark feature of some Chlamydia species and strains, and the trait has been linked to plasmid-regulated expression of glycogen metabolism enzymes and acquisition of UDP-glucose from the host cell (5, 13, 30, 31). To determine the role of GlgB in glycogen production inside C. muridarum inclusions, we compared the abilities of a glgB::Tn mutant clone (UWCM027) and the WT parent to synthesize and accumulate glycogen in inclusions. GlgB is a predicted 1,4-alpha-glucan branching protein and was expected to play a critical role in glycogen biosynthesis inside inclusions (13). McCoy cells were infected with the glgB::Tn mutant, WT C. muridarum, or a plasmid-free C. muridarum strain; stained with iodine at 26 h postinfection (hpi) to label glycogen; and analyzed by bright-field microscopy. Inclusions derived from the glgB::Tn mutant contained dark purple-black deposits representative of amylose accumulation (Fig. 4), a feature that was visually distinct from those of both the WT (accumulated glycogen) and plasmid-lacking (no-glycogen) strains (30, 32). To confirm that this phenotype was due to transposon-mediated disruption of glgB, we generated a complemented strain transformed with a plasmid containing WT glgB and mCherry. Iodine staining of inclusions infected with the WT-glgB-complemented strain (glgB::Tn plus WT glgB) demonstrated a restoration of glycogen accumulation to WT levels (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Deficient glycogen accumulation in glgB::Tn inclusions. McCoy cells were infected with WT C. muridarum, a glgB::Tn mutant, a plasmid-free strain of C. muridarum (Cm P–), or a complemented glgB::Tn strain expressing WT glgB. Iodine staining of the infected cells at 26 hpi showed glycogen accumulation in WT and complemented inclusions (dark orange), no glycogen in Cm P– inclusions, and amylose accumulation in glgB::Tn inclusions (purple with dark deposits). Representative inclusions in each image are marked with asterisks.

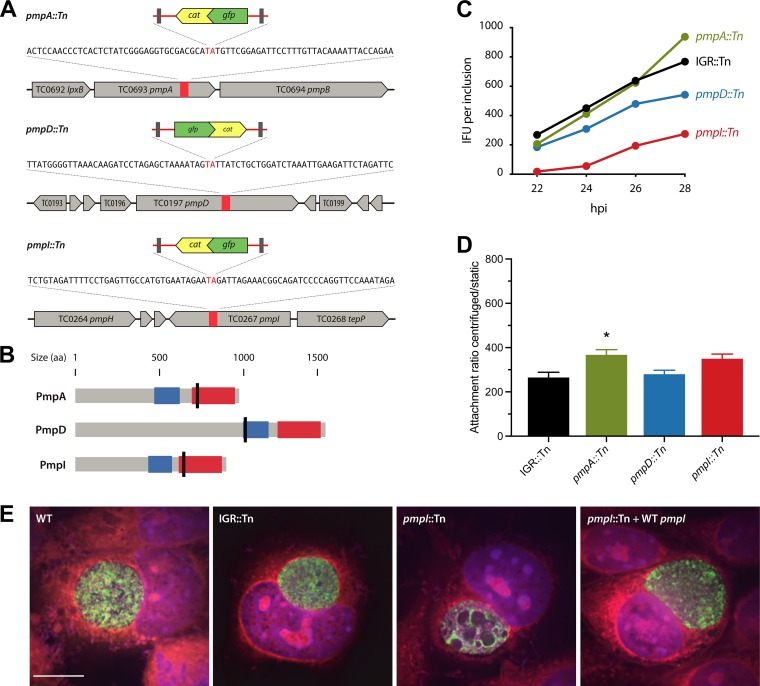

In vitro phenotypes of C. muridarum pmp mutants.

Three transposon insertions in the library fell within polymorphic membrane protein (pmp) genes (Fig. 5A), encoding a protein family with potential functions in Chlamydia adherence and pathogenesis (33–36). Isogenic transposon mutants therefore presented a unique opportunity to test the importance of individual Pmp proteins—PmpI, PmpA, and PmpD—for in vitro growth phenotypes in C. muridarum. The pmpD::Tn transposon mutant contained a second transposon insertion in gnd, encoding 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Table 1). In all three pmp mutants, transposon insertion sites lay upstream of the autotransporter domains (Fig. 5B), and therefore, the truncated proteins were predicted to be functionally disrupted. We performed growth curve analysis by infecting McCoy cells with each of the mutant strains or a control strain with an intergenic transposon insertion (IGR::Tn [IGR, intergenic region]; UWCM016), at low multiplicities of infection (MOI) and measured the amount of infectious progeny production for each strain on a per-inclusion basis over 22 to 28 hpi. UWCM016 was selected as a control over other IGR::Tn mutants because the transposon in the mutant was over 250 and 600 nucleotides away from the nearest, diverging genes. Compared to the IGR::Tn control strain, the pmpI::Tn mutant exhibited significant attenuation across all the times examined—64% fewer infectious progeny than the IGR::Tn strain at 28 hpi (Fig. 5C). The pmpD::Tn mutant was also partially attenuated for growth, with 30% reduced progeny formation at 28 hpi compared to the IGR::Tn strain. The pmpA::Tn mutant exhibited no growth attenuation; however, it reproducibly produced greater amounts of infectious elementary bodies (EB) at 28 hpi only, 122% of the EB produced by the IGR::Tn strain (Fig. 5C). We tested whether the presence of the transposon had any deleterious effect on chlamydial growth by comparing propagation ratios between the IGR::Tn control and WT C. muridarum, and we measured similar levels of inclusion-forming unit (IFU) production for both control strains (745 ± 69 for the WT and 739 ± 37 for the IGR::Tn strain) (data not shown). The enhanced progeny formation phenotype of the pmpA::Tn strain correlated with an abundance of floating Chlamydia-containing objects above the pmpA::Tn mutant-infected cell monolayer (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These objects resembled chlamydial extrusions (37, 38); however, we do not have an explanation or hypothesis for why this particular mutant would produce either more extrusions or more stable ones. The observations were nonetheless reproducible, and it was not pursued further because of its minor contribution to pmpA::Tn phenotypes.

FIG 5.

In vitro phenotypes of C. muridarum pmp mutants. (A) Chromosomal locations of transposon insertions in pmp genes. The orientations of inserts are indicated by the gene directionality. (B) Predicted protein topologies of Pmp proteins. Transposon insertion sites are marked with black lines; blue, Pmp middle domain; red, autotransporter domain. (C) Inclusion burst sizes of pmpI::Tn, pmpA::Tn, and pmpD::Tn strains versus an IGR::Tn control strain. McCoy cells infected with the indicated strains were harvested at the times postinfection indicated, and the amount of infectious progeny in each sample was determined by infecting fresh McCoy cells, followed by IFU assays. (D) Attachment of the indicated strains to McCoy cells was determined by inoculating the cells under centrifugation-aided and static conditions. The ratios of centrifugation to static conditions were computed. The data represent means, and the error bars indicate standard deviations. Statistical comparisons between transposon mutants and the IGR::Tn control were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05. (E) Confocal immunofluorescence analysis of inclusions containing WT C. muridarum, the IGR::Tn or pmpI::Tn mutant, and the complemented pmpI::Tn-plus-WT pmpI strain analyzed at 24 hpi. Green, anti-LPS; blue, DAPI; red, Evans blue. Scale bar, 10 μm.

We next characterized Chlamydia cell and inclusion morphologies within host cells infected with pmp transposon mutants. L929 mouse fibroblasts were infected with WT C. muridarum, IGR::Tn, pmpI::Tn, and pmpI::Tn-plus-WT pmpI strains and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy at 24 hpi. Antilipooligosaccharide (anti-LOS) immunofluorescence revealed that every pmpI::Tn inclusion contained enlarged, abnormal-size bodies within the chlamydial inclusion (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). pmpI::Tn plus WT pmpI restored the phenotype of pmpI::Tn to wild-type phenotypic conditions (Fig. 5E). Inclusions derived from the pmpA::Tn mutant appeared WT in terms of general morphology, as did pmpA::Tn-plus-WT pmpA mutant-derived inclusions (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Inclusions containing pmpD::Tn mutants mostly exhibited bacteria and inclusion morphologies and distributions like those containing WT C. muridarum. Approximately 30% of pmpD::Tn inclusions contained abnormally dispersed bacteria (see Fig. S3).

Pmp proteins have been reported to play roles in Chlamydia attachment to host cells, including C. pneumoniae (33, 36, 39) and C. trachomatis (10). We investigated whether PmpA, PmpD, or PmpI individually contributed to C. muridarum binding to McCoy cells by measuring attachment under centrifugation-aided versus static conditions. Cells were infected with each pmp::Tn mutant or an IGR::Tn control using a low MOI to ensure that the resulting inclusions were derived from individual bacteria. Parallel infections were performed with centrifugation or in static culture, and at 20 to 22 hpi, the cells were lysed, the numbers of infectious EB were determined by infecting fresh McCoy cells, and the numbers of IFU per original inclusion were back calculated. The overall attachment efficiencies for all C. muridarum strains were low, and determination of the ratios of inclusion burst sizes under centrifugation and static conditions showed minimal differences attributable to each of the pmp mutants (Fig. 5D). There appeared to be a slight trend toward reduced attachment of pmpI::Tn and pmpA::Tn mutants under static conditions (Fig. 5D).

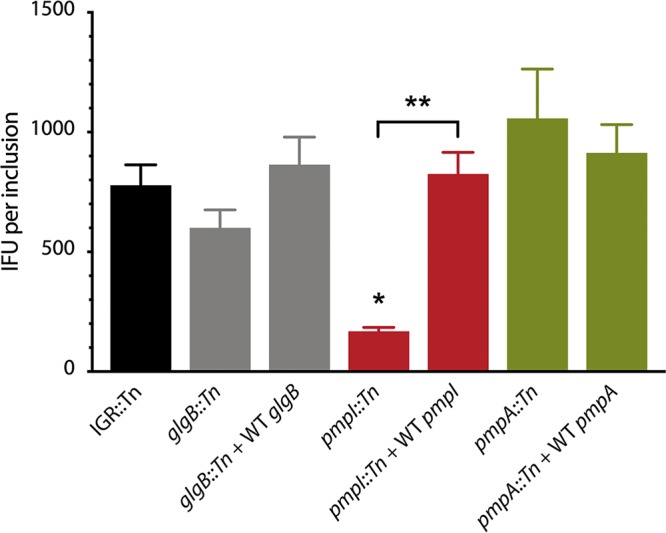

Complementation of transposon mutants restored in vitro growth phenotypes.

To validate the genotypes of glgB and pmp genes, we generated complemented strains containing plasmid-borne mCherry and WT glgB, WT pmpI, or WT pmpA. Complemented genes were placed under the control of their endogenous promoters, and mCherry was constitutively expressed. The pmpD::Tn mutant was not included for complementation analysis due to the large size of the pmpD gene and weak phenotypes associated with the mutant. For each complemented strain, the capacity for complete inclusion growth was determined by measuring IFU on a per-inclusion basis, using serial infections with low-MOI inocula. Compared to cells infected with the IGR::Tn strain, glgB::Tn mutant-infected cells produced 23% fewer IFU (Fig. 6). The small growth defect due to transposon disruption of glgB, while not statistically significant, was overcome by complementation with plasmid-expressed WT glgB (Fig. 6). These data for glgB are consistent with previous findings for glgB mutants in C. trachomatis (13). Cells infected with pmpI- and pmpA-complemented strains also exhibited restored growth phenotypes (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

In vitro growth phenotypes of transposon mutants and complemented strains. The growth of mutants and complemented strains was assessed by the IFU propagation ratio. McCoy cells were infected with each strain in 24-well plates. At 20 to 22 hpi, images were taken for inclusion counting by fluorescence microscopy. At 26 hpi, the cells were lysed and the bacteria were inoculated onto fresh McCoy cells for IFU determination. The data are expressed as means, and the error bars indicate standard deviations. Statistical comparisons between the transposon mutants, complemented strains, and IGR::Tn control were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

An increasing number of genetic tools have emerged for genetic manipulation of Chlamydia (4, 40). The recent development of a transposon mutagenesis system for C. trachomatis L2/434 by Hefty and colleagues adds a powerful new technique to this growing repertoire of chlamydial genetic techniques (18). This study expands on the transposon technological platform by adapting it for use in the rodent species C. muridarum. The development of a transposon mutant library in C. muridarum provides two important advantages. First, it enables functional genetic analysis of homologous chlamydial gene products across two Chlamydia species. Second, it allows the screening of chlamydial genes for critical in vivo functions in their matched host species. Functional genetic studies in cell culture are likely not the best model for Chlamydia, based on evidence that particular loci rapidly accumulate disruptive mutations during adaptation of C. trachomatis to cell culture and mice (41, 42). Thus, we expect that the growing availability of isogenic transposon mutants in C. muridarum will be a valuable resource for investigators in the field.

The distribution and frequency of transposon insertions in this initial library suggest that transposon insertions occurred without chromosomal bias. Consequently, the eventual generation of a saturation library in genes and operons that can tolerate disruption is feasible. As for C. trachomatis, the critical bottleneck limiting the generation of transposon mutants is getting DNA into the bacteria. This limitation continues to be a major factor for most genetic-engineering applications in Chlamydia (4, 5). Based on previous genome-wide chemical mutagenesis findings, where 75 unique nonsense mutants were obtained (14), one can speculate on how many transposon mutants are necessary to achieve saturation levels of mutagenesis. We have run statistical modeling and determined that a library of 1,000 mutants would cover 599 of ∼890 Chlamydia open reading frames (ORFs); 2,000 mutants would cover 784 ORFs with 1,216 duplicate hits. This library size likely would approach saturation levels of mutagenesis. Our C. muridarum library contains transposon insertions in coding and intergenic regions, and while the majority of inserts were in the chromosome, a mutant was obtained in the C. muridarum plasmid. Curiously, several mutant clones harboring two transposon insertions were obtained. This is in contrast to C. trachomatis, where only mutants with single insertions were derived across nearly 100 mutant strains (18). The simplest explanation for the occurrence of double insertions is that it was an outcome of two or more plasmid copies entering a bacterium, allowing the mobilization of two transposons into the chromosome. Supporting evidence for this comes from analysis of mutant UWCM007, which contained transposon insertions in TC0257 glgB and TC0431 macP. Subsequent whole-genome sequencing analysis of plaque clones from this parent mutant strain showed the presence of two subpopulations—one containing an insert in TC0257 glgB and another containing inserts in the same location in TC0257 glgB and additionally in TC0431 macP. The likeliest explanation for the generation of these mutant clones is that a first insertion occurred in TC0257 glgB and, after some chlamydial replication, a second insertion occurred from residual plasmid in TC0431 macP in a single daughter cell. An alternative explanation, given the low efficiency of DNA delivery into Chlamydia and the observation that double insertions have not yet been detected in C. trachomatis (18), is different mechanisms of drug selection—chloramphenicol in C. muridarum and penicillin in C. trachomatis. The bacteriostatic effect of chloramphenicol could enable the relatively rare double molecule uptake and transposon insertion. Additional possibilities include the contribution of marker removal by recombination with wild-type genomes, or possibly low-level pCMC5M plasmid replication, to the generation of double transposon insertions.

Among the diversity of transposon mutants generated in this study, 4 particular insertions were selected for follow-up investigation based on the predicted biological functions of the disrupted genes in Chlamydia infections. The importance of the chlamydial enzymes GlgA and GlgX for glycogen biosynthesis and accumulation in the inclusion lumen has been characterized for C. trachomatis (5, 30, 31, 43). Furthermore, a GlgB C. trachomatis mutant strain derived from chemical mutagenesis was shown to be defective in converting unbranched to branched glycogen in the inclusion lumen (13). Our data using the glgB::Tn isogenic mutant confirmed that the glycogen-debranching enzyme GlgB plays a similarly important role for glycogen biosynthesis in C. muridarum inclusions and additionally demonstrates that GlgB-deficient C. muridarum bacteria accumulate the glycogen intermediate amylose in their inclusion lumens. We expect that the isolation of transposon insertions in additional genes predicted to play roles in chlamydial glycogen biosynthesis, through expansion of the transposon mutant library, will be informative to further advance our understanding of the role glycogen plays in Chlamydia biology (31).

Also of high interest were three transposon insertions in the polymorphic membrane protein ORFs pmpI, pmpA, and pmpD. Pmps comprise a 9-member family of autotransporter adhesins in C. muridarum and C. trachomatis, and their presence in all sequenced Chlamydia strains is suggestive of important functions mediated by each Pmp protein (35, 44). Neutralizing antibodies to Pmps have been shown to be effective at blunting infection (33, 45), and recombinant C. trachomatis Pmps were capable of eliciting protective immune responses against C. muridarum challenge in mice (46). It has been hypothesized that pmp genes may undergo a type of antigenic variation through patterns of transcriptional and/or translational expression (47–50). Our data show that C. muridarum lacking PmpI exhibited significant growth defects in cell culture. These results are consistent with prior reports that PmpI plays a prominent role during C. trachomatis infection, particularly under conditions of stress (50). The previous study also showed that the expression of PmpA, PmpD, and PmpI genes was less affected than that of other pmp genes in penicillin-stressed cells and suggested that these Pmps might play important functional roles for Chlamydia (50). Our data showed that PmpD is important for optimal C. muridarum growth in culture, whereas PmpA was dispensable. The lack of pronounced phenotypes for pmpD::Tn substantiates a previous report that a pmpD-null strain of C. trachomatis had no defect in murine cell culture or in mice (51). The study also reported reduced attachment to human cells and abnormal morphology with the pmpD-null mutant, which is somewhat similar to the inclusion morphology obtained in the present study for the pmpD::Tn mutant. In summary, our data demonstrate that transposon mutagenesis is a powerful new tool for functional genetic investigation in C. muridarum, in that isogenic mutants can be evaluated for phenotypes in a cell culture system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and bacterial strains.

McCoy cells were cultured in 6-well plates or T-25 flasks in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) GlutaMax growth medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (full growth medium [FGM]). C. muridarum strain Nigg (provided by Kyle Ramsey) was grown in McCoy cells and centrifuged at 700 × g for 30 to 60 min to initiate infection. Following centrifugation, the medium was replaced with fresh FGM supplemented with 1 μg/ml cycloheximide.

Transposon mutant generation.

C. muridarum transposon mutants were generated by transformation of wild-type C. muridarum with the transposon vector pCMC5M, using the previously described CaCl2 transformation system and chloramphenicol for selection (5, 52, 53). Briefly, C. muridarum EB (∼2 × 107 IFU) were mixed with plasmid pCMC (∼10 μg) in 200 μl of CaCl2-Tris buffer for 20 to 30 min at room temperature (RT). Meanwhile, approximately 6 × 106 McCoy cells were resuspended in 300 μl of CaCl2-Tris buffer. The bacterium-plasmid mixture was then added to McCoy cells and incubated at RT for a further 15 min. Finally, the cell-bacterium-plasmid mixture was aliquoted into a 6-well plate with 2 ml FGM in each well. The plate was incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for ∼2 h before being centrifuged at 700 × g for 30 to 60 min. The plate was placed in the incubator for approximately 6 h, after which the culture medium was replaced with FGM supplemented with 0.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 1 μg/ml cycloheximide. At 30 hpi, cultures from each well were harvested individually for further passages and selections in 0.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The cultures were frequently and carefully checked for GFP expression on an inverted fluorescence microscope. The isolated mutants were plaque cloned and serially passaged 3 or 4 times through McCoy cells. The resulting clones were expanded and then stored at −80°C until they were used.

Stability test of transposon insertions.

Cloned transposon mutants were grown continuously in either the presence or absence of 0.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol selection. For each passage, serial dilutions of samples were used to infect McCoy cells in 24-well plates. Samples in the wells with ∼10 to 20% infection were harvested 24 hpi and then used for the next round of passage. After 10 passages, all the samples were grown in medium without chloramphenicol for genomic-DNA extraction. PCRs were performed using primers flanking the transposon inserts and genomic DNA as templates.

PCR genotyping of mutants.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from mutants growing in McCoy cells for sequencing using the primers within the transposon: MCIP_upseq1, 5′-ACACACGCGGCACTTTATAG-3′, and Cat_dseq_2, 5′-CAGGGCGGGGCGTAAAGATC-3′. The locations of transposon insertions were first predicted by aligning a short sequence right after the transposon inverted repeat (IR) with the sequence of C. muridarum Nigg in GenBank (NC_002620) and then confirmed by sequencing using primers on the genome (near the transposon insertions) and PCR using primer sets on the genome flanking the transposon insertions (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Whole-genome sequencing.

Purified EB were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in water and treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) at 37°C for 30 min. RQ1 stop solution was added to the solution for 10 min at 65°C. Dithiothreitol was added to a final concentration of 5 mM, and the lysates were incubated at 56°C for 1 h. Genomic DNA was then extracted using a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). Whole-genome sequencing templates were prepared using a Nextera XT DNA library preparation (Illumina). Genome sequencing was conducted on an Illumina HiSeq 3000 at the Oregon State University Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing Core. The Illumina-generated reads were filtered and trimmed using Trimmomatic (54). The manicured read files were mapped to the parental strains using the programs Bowtie2 (55) and Trinity (56) and assembled using the bioinformatics software platform Geneious (57). Genome sequences were assembled using a reference-guided approach employing the genome sequence of C. muridarum NC_002620 (26).

Generation of complemented strains.

Three plasmid vectors, pNigg-mCherry-glgB, pNigg-mCherry-pmpA, and pNigg-mCherry-pmpI, were constructed for complementation studies of three C. muridarum transposon mutants in which one of the glgB, pmpA, and pmpI genes was interrupted. The vectors contained a backbone of C. muridarum Nigg plasmid CDS2-8, the pUC origin of replication (ori), bla, and mCherry, as well as a genomic gene. These plasmid vectors were transformed into corresponding C. muridarum transposon mutants under penicillin selection. The transformants were visualized by red fluorescence from mCherry.

Immunofluorescence and light microscopy.

L929 cells were grown to near confluence in an 8-well ibiTreat μ-Slide (Ibidi, Martinsried, Germany) and were infected with the respective wild-type C. muridarum or transposon mutant at about 10 to 20 IFU per well. At 24 hpi, the infected cells were fixed with 100% methanol for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were washed once with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) and again with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then stained with PathoDx Chlamydia culture confirmation (Remel, Kent, United Kingdom) (Evans blue counterstain and anti-lipopolysaccharide [anti-LPS] GFP-conjugated antibody) diluted 1:40 in PBS overnight at room temperature in the dark. Twenty microliters of 1 μM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) diluted 1:100 in PBS was then added to the wells and allowed to stain for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. The stain was then removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. A final overlay of Vectashield antifade mounting medium (Vector, Burlingame, CA) was added, and the slides were immediately imaged. The cells were visualized on an Olympus IX81/3I spinning-disk confocal inverted microscope at ×150 magnification and captured on an Andor (Belfast, Northern Ireland) Zyla 4.2 scientific complementary metal oxide semiconductor (sCMOS) camera. The microscope and camera were operated using SlideBook 6 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Eight to 10 inclusions were imaged for each wild-type C. muridarum cell or transposon mutant. The exposure time remained consistent for all fields captured, with exposure for DAPI (DNA) at 1 s, LPS (Chlamydia) at 3 s, and cytoplasm (host cell) at 2.5 s. At least 10 z-stack images 0.3 μm apart were taken per imaged field. The images were processed in SlideBook 6 using a no-neighbors deconvolution, with a subtraction constant of 0.4 applied to all the images.

Iodine staining of Chlamydia-infected cells.

McCoy cells cultured on glass coverslips in individual shell vials were infected with the above-described strains at an MOI of 0.5 and incubated for 26 h. To detect the presence of accumulated glycogen, the medium was removed and the monolayers were rinsed 3 times with PBS and then stained with iodine (58). Briefly, a solution of 50% methanol and 50% iodine was added to the monolayers for 5 min and then removed, and coverslips were mounted with a solution of 50% iodine solution plus 50% glycerol. The iodine-stained cells were immediately imaged using a Nikon digital camera system.

In vitro growth profiles of mutants.

The in vitro growth profiles of C. muridarum transposon insertion mutants were assessed by the IFU propagation ratio, i.e., the number of IFU (inclusions) produced from 1 IFU after infection of McCoy cells for a period of time. All the strains were prepared and grown in parallel to avoid any confounding issues due to host cells, media, or handling. Mutant stocks were grown in parallel in McCoy cells at series dilution in 24-well plates, and the wells with ∼10 to 30% infection were chosen for imaging and harvest. At 20 to 22 hpi, 20 GFP images were taken randomly for inclusion counting to estimate the initial IFU in the wells. The samples in the wells were harvested at selected time points (22 h, 24 h, 26 h, and 28 h). To assess the IFU in these time point samples, 6 wells of McCoy cells in a 24-well plate were infected with each sample dilution (1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:400, 1:800, and 1:1,600), and the wells with ∼10 to 20% infection were chosen for imaging. Again, about 22 hpi, 20 GFP images were taken randomly for inclusion counting. The green inclusions were counted using the Fuji image-processing package (ImageJ).

Cell adherence assays.

The attachment efficiencies of the C. muridarum mutant strains were measured in the presence or absence of centrifugation, with slight modifications from published procedures (10). McCoy cells were grown in 24-well plates to 90% confluence and washed with HBSS prior to use. C. muridarum samples were diluted with a 2-fold dilution series in HBSS, and 0.5 ml of diluted bacteria was inoculated onto McCoy monolayers. A starting MOI of ∼1 was used for centrifuged samples and ∼100 for static samples. Low-MOI plates were spun at 700 × g for 1 h, after which the cells were incubated with fresh medium containing cycloheximide. High-MOI plates were incubated with C. muridarum for 2 h at room temperature without agitation, after which the cells were incubated with fresh medium containing cycloheximide. At 20 to 22 hpi, samples were subjected to live fluorescence microscopy to visualize and image inclusions containing GFP-expressing C. muridarum. Ten random images were taken for each sample well at ×20 magnification. Inclusion counts were quantified using ImageJ. From two experiments, five sets of data were calculated from each mutant with similar infection ratios in both centrifuged and noncentrifuged samples.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software. Comparisons between IFU, bacterial attachment, and in vivo bacterial burdens were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Oregon State University Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing for sequencing and bioinformatics assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, NIAID AI126785, to K. Hybiske and P. S. Hefty.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00366-19.

For a companion article on this topic, see https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00365-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torrone E, Papp J, Weinstock H, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection among persons aged 14-39 years—United States, 2007–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:834–838. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson NB, Hayes LD, Brown K, Hoo EC, Ethier KA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. CDC National Health Report: leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Suppl 63:3–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastidas RJ, Valdivia RH. 2016. Emancipating Chlamydia: advances in the genetic manipulation of a recalcitrant intracellular pathogen. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:411–427. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00071-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hooppaw AJ, Fisher DJ. 2015. A coming of age story: Chlamydia in the post-genetic era. Infect Immun 84:612–621. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01186-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, Clarke IN. 2011. Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickstrum J, Sammons LR, Restivo KN, Hefty PS. 2013. Conditional gene expression in Chlamydia trachomatis using the tet system. PLoS One 8:e76743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson CM, Fisher DJ. 2013. Site-specific, insertional inactivation of incA in Chlamydia trachomatis using a group II intron. PLoS One 8:e83989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demars R, Weinfurter J, Guex E, Lin J, Potucek Y. 2007. Lateral gene transfer in vitro in the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol 189:991–1003. doi: 10.1128/JB.00845-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMars R, Weinfurter J. 2008. Interstrain gene transfer in Chlamydia trachomatis in vitro: mechanism and significance. J Bacteriol 190:1605–1614. doi: 10.1128/JB.01592-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffrey BM, Suchland RJ, Eriksen SG, Sandoz KM, Rockey DD. 2013. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of in vitro-generated Chlamydia trachomatis recombinants. BMC Microbiol 13:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller KE, Wolf K, Fields KA. 2016. Gene deletion by fluorescence-reported allelic exchange mutagenesis in Chlamydia trachomatis. mBio 7:e01817. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01817-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kari L, Goheen MM, Randall LB, Taylor LD, Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Virok D, Rajaram K, Endresz V, McClarty G, Nelson DE, Caldwell HD. 2011. Generation of targeted Chlamydia trachomatis null mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:7189–7193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102229108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen BD, Valdivia RH. 2012. Virulence determinants in the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis revealed by forward genetic approaches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:1263–1268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117884109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kokes M, Dunn JD, Granek JA, Nguyen BD, Barker JR, Valdivia RH, Bastidas RJ. 2015. Integrating chemical mutagenesis and whole-genome sequencing as a platform for forward and reverse genetic analysis of Chlamydia. Cell Host Microbe 17:716–725. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdelrahman YM, Belland RJ. 2005. The chlamydial developmental cycle. FEMS Microbiol Rev 29:949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, Engel J. 2016. Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:385–400. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel C, Fan J, Marathe R, Aravind L, Mitchell W, Olinger L, Tatusov RL, Zhao Q, Koonin EV, Davis RW. 1998. Genome sequence of an obligate intracellular pathogen of humans: Chlamydia trachomatis. Science 282:754–759. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaBrie SD, Dimond ZE, Harrison KS, Baid S, Wickstrum J, Suchland RJ, Hefty PS. 2019. Transposon mutagenesis in Chlamydia trachomatis identifies CT339 as a ComEC homolog important for DNA uptake and lateral gene transfer. mBio 10:e01343-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01343-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akerley BJ, Rubin EJ, Camilli A, Lampe DJ, Robertson HM, Mekalanos JJ. 1998. Systematic identification of essential genes by in vitro mariner mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:8927–8932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hensel M, Shea JE, Gleeson C, Jones MD, Dalton E, Holden DW. 1995. Simultaneous identification of bacterial virulence genes by negative selection. Science 269:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.7618105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. 2003. Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol 48:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajaram K, Giebel AM, Toh E, Hu S, Newman JH, Morrison SG, Kari L, Morrison RP, Nelson DE. 2015. Mutational analysis of the Chlamydia muridarum plasticity zone. Infect Immun 83:2870–2881. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00106-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conrad TA, Gong S, Yang Z, Matulich P, Keck J, Beltrami N, Chen C, Zhou Z, Dai J, Zhong G. 2016. The chromosome-encoded hypothetical protein TC0668 is an upper genital tract pathogenicity factor of Chlamydia muridarum. Infect Immun 84:467–479. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01171-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Z, Tang L, Shao L, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Schenken R, Valdivia R, Zhong G. 2016. The Chlamydia-secreted protease CPAF promotes chlamydial survival in the mouse lower genital tract. Infect Immun 84:2697–2702. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00280-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao L, Zhang T, Liu Q, Wang J, Zhong G. 2017. Chlamydia muridarum with mutations in chromosomal genes tc0237 and/or tc0668 is deficient in colonizing the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Infect Immun 85:e00321-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00321-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read TD, Brunham RC, Shen C, Gill SR, Heidelberg JF, White O, Hickey EK, Peterson J, Utterback T, Berry K, Bass S, Linher K, Weidman J, Khouri H, Craven B, Bowman C, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Nelson W, DeBoy R, Kolonay J, McClarty G, Salzberg SL, Eisen J, Fraser CM. 2000. Genome sequences of Chlamydia trachomatis MoPn and Chlamydia pneumoniae AR39. Nucleic Acids Res 28:1397–1406. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.6.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson DE, Crane DD, Taylor LD, Dorward DW, Goheen MM, Caldwell HD. 2006. Inhibition of chlamydiae by primary alcohols correlates with the strain-specific complement of plasticity zone phospholipase D genes. Infect Immun 74:73–80. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.73-80.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voigt A, Schöfl G, Saluz HP. 2012. The Chlamydia psittaci genome: a comparative analysis of intracellular pathogens. PLoS One 7:e35097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belland RJ, Scidmore MA, Crane DD, Hogan DM, Whitmire W, McClarty G, Caldwell HD. 2001. Chlamydia trachomatis cytotoxicity associated with complete and partial cytotoxin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:13984–13989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241377698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Crane DD, Wicke L, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant DE, Kupko JJ III, Porcella SF, Martinez-Orengo N, Heinzen RA, Kari L, Caldwell HD. 2008. The Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid is a transcriptional regulator of chromosomal genes and a virulence factor. Infect Immun 76:2273–2283. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00102-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gehre L, Gorgette O, Perrinet S, Prevost M-C, Ducatez M, Giebel AM, Nelson DE, Ball SG, Subtil A. 2016. Sequestration of host metabolism by an intracellular pathogen. Elife 5:e12552. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyashita N, Matsumoto A, Fukano H, Niki Y, Matsushima T. 2001. The 7.5-kb common plasmid is unrelated to the drug susceptibility of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Chemother 7:113–116. doi: 10.1007/s1015610070113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mölleken K, Schmidt E, Hegemann JH. 2010. Members of the Pmp protein family of Chlamydia pneumoniae mediate adhesion to human cells via short repetitive peptide motifs. Mol Microbiol 78:1004–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Lent S, De Vos WH, Huot Creasy H, Marques PX, Ravel J, Vanrompay D, Bavoil P, Hsia R-C. 2016. Analysis of polymorphic membrane protein expression in cultured cells identifies PmpA and PmpH of Chlamydia psittaci as candidate factors in pathogenesis and immunity to infection. PLoS One 11:e0162392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vasilevsky S, Stojanov M, Greub G, Baud D. 2016. Chlamydial polymorphic membrane proteins: regulation, function and potential vaccine candidates. Virulence 7:11–22. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2015.1111509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker E, Hegemann JH. 2014. All subtypes of the Pmp adhesin family are implicated in chlamydial virulence and show species-specific function. Microbiologyopen 3:544–556. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hybiske K, Stephens RS. 2007. Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:11430–11435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703218104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuck M, Sherrid A, Suchland R, Ellis T, Hybiske K. 2016. Conservation of extrusion as an exit mechanism for Chlamydia. Pathog Dis 74:ftw093. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftw093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luczak SET, Smits SHJ, Decker C, Nagel-Steger L, Schmitt L, Hegemann JH. 2016. The Chlamydia pneumoniae adhesin Pmp21 forms oligomers with adhesive properties. J Biol Chem 291:22806–22818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.728915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valdivia RH, Bastidas RJ. 2018. The expanding molecular genetics tool kit in Chlamydia. J Bacteriol 200:e00590-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00590-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sturdevant GL, Kari L, Gardner DJ, Olivares-Zavaleta N, Randall LB, Whitmire WM, Carlson JH, Goheen MM, Selleck EM, Martens C, Caldwell HD. 2010. Frameshift mutations in a single novel virulence factor alter the in vivo pathogenicity of Chlamydia trachomatis for the female murine genital tract. Infect Immun 78:3660–3668. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00386-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonner C, Caldwell HD, Carlson JH, Graham MR, Kari L, Sturdevant GL, Tyler S, Zetner A, McClarty G. 2015. Chlamydia trachomatis virulence factor CT135 is stable in vivo but highly polymorphic in vitro. Pathog Dis 73:ftv043. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song L, Carlson JH, Whitmire WM, Kari L, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant DE, Watkins H, Zhou B, Sturdevant GL, Porcella SF, McClarty G, Caldwell HD. 2013. Chlamydia trachomatis plasmid-encoded Pgp4 is a transcriptional regulator of virulence-associated genes. Infect Immun 81:636–644. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01305-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimwood J, Stephens RS. 1999. Computational analysis of the polymorphic membrane protein superfamily of Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae. Microb Comp Genomics 4:187–201. doi: 10.1089/omi.1.1999.4.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crane DD, Carlson JH, Fischer ER, Bavoil P, Hsia R-C, Tan C, Kuo C-C, Caldwell HD. 2006. Chlamydia trachomatis polymorphic membrane protein D is a species-common pan-neutralizing antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:1894–1899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508983103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pal S, Favaroni A, Tifrea DF, Hanisch PT, Luczak SET, Hegemann JH, de la Maza LM. 2017. Comparison of the nine polymorphic membrane proteins of Chlamydia trachomatis for their ability to induce protective immune responses in mice against a C. muridarum challenge. Vaccine 35:2543–2549. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vandahl BB, Pedersen AS, Gevaert K, Holm A, Vandekerckhove J, Christiansen G, Birkelund S. 2002. The expression, processing and localization of polymorphic membrane proteins in Chlamydia pneumoniae strain CWL029. BMC Microbiol 2:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan C, Hsia R-C, Shou H, Haggerty CL, Ness RB, Gaydos CA, Dean D, Scurlock AM, Wilson DP, Bavoil PM. 2009. Chlamydia trachomatis-infected patients display variable antibody profiles against the nine-member polymorphic membrane protein family. Infect Immun 77:3218–3226. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01566-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grimwood J, Olinger L, Stephens RS. 2001. Expression of Chlamydia pneumoniae polymorphic membrane protein family genes. Infect Immun 69:2383–2389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2383-2389.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carrasco JA, Tan C, Rank RG, Hsia R-C, Bavoil PM. 2011. Altered developmental expression of polymorphic membrane proteins in penicillin-stressed Chlamydia trachomatis. Cell Microbiol 13:1014–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kari L, Southern TR, Downey CJ, Watkins HS, Randall LB, Taylor LD, Sturdevant GL, Whitmire WM, Caldwell HD. 2014. Chlamydia trachomatis polymorphic membrane protein D is a virulence factor involved in early host-cell interactions. Infect Immun 82:2756–2762. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01686-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu S, Battaglia L, Bao X, Fan H. 2013. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase as a selection marker for chlamydial transformation. BMC Res Notes 6:377. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Ramsey KH, Thomson NR, Clarke IN. 2014. The genetic basis of plasmid tropism between Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia muridarum. Pathogens Dis 72:19–23. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A. 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol 29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schachter J, Dawson CR. 1978. Laboratory diagnosis, p 181–220. In Schachter J, Dawson CR (ed), Human chlamydial infections. PSG Publishing Company, Burlington, MA. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.