Watch a video presentation of this article

Answer questions and earn CME

Abbreviations

- ASPEN

American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- BCAA

branched‐chain amino acid

- ESPEN

European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

- REE

resting energy expenditure

Prevention and management of malnutrition are essential to improve clinical outcomes for patients with cirrhosis. Depending on the population and assessment method of malnutrition, it is estimated that 50% to 90% of individuals with cirrhosis have malnutrition.1 Individuals may struggle to meet calorie and protein requirements for a multitude of reasons, including but not limited to: increased nutrient requirements, reduced intake, malabsorption, and alterations in protein and glucose metabolism. Early nutrition education and aggressive nutrition interventions are imperative for preventing and halting progression of malnutrition in the population of patients with cirrhosis.

To prevent and treat malnutrition in patients with cirrhosis, clinicians need to prioritize nutrition care for the individual. Given the complexity of nutrition management, a registered dietitian should be involved in the care of these patients to complete a detailed nutrition assessment and intervention. Health literacy, socioeconomic status, social support, and alterations in mental status should all be considered when performing nutrition assessments and providing diet education. Clinicians need to be flexible and concise in their recommendations so that patients understand exactly which nutrition goals to prioritize. In addition, nutrition priorities and goals may change as acuity of the patient's clinical status changes (i.e., decompensated in the hospital versus well‐compensated at home). When discussing nutrition recommendations, total caloric intake and allocation of other macronutrients are important factors given the metabolic changes seen in those with cirrhosis.

Nutrition Priority One: Adequate Caloric Intake

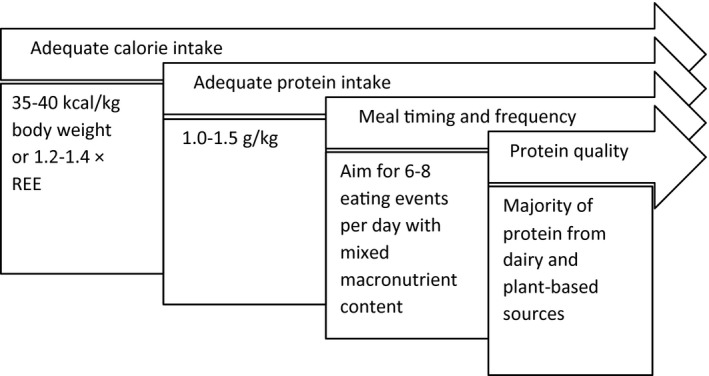

The first nutrition priority for the patient with cirrhosis is to promote overall adequate intake regardless of the macronutrient distribution (Fig. 1). Ensuring overall adequate intake decreases the duration of the fasting state in the body and in turn prevents muscle catabolism. Caloric recommendations for patients with cirrhosis are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Progression of nutrition provision priorities for the patient with cirrhosis.

Table 1.

Nutrition Requirements for End‐Stage Liver Disease With Cirrhosis

Nutrition Priority Two: Adequate Protein Intake

After a patient is working toward improvements in overall caloric intake, then education can shift toward the second priority: protein intake. Ensuring the patient meets protein requirements is essential to conserving lean body mass. Protein requirements are recommended to be 1.0 to 1.5 g/kg dry body weight (Table 1).2, 3 Whereas protein restrictions were once implemented with the intent of preventing encephalopathy, this is not currently recommended. There are no clinical differences in severity of hepatic encephalopathy between patients receiving a low versus normal protein diet during hospital admission for acute hepatic encephalopathy exacerbation. Further, patients prescribed a protein restriction have an increase in the breakdown of skeletal muscle.4 Patients with acute encephalopathy should be provided the appropriate medical management for their symptoms rather than restricting protein intake.3

Nutrition Priority Three: Meal Composition and Timing

The third nutrition priority for patients with cirrhosis involves the ideal composition and frequency of meal and snack intake. Given changes in the liver's ability to store glycogen, intake of carbohydrate in conjunction with protein ensures proper allocation of protein for muscle maintenance and rebuilding.5 Having these mixed macronutrient meals and snacks at regular and frequent intervals throughout waking hours helps the patient meet nutritional needs and reduce the time the patient's body is spent in a fasting state. Therefore, it is recommended that patients have a bedtime time snack containing carbohydrate and protein.5 An example of meal composition and timing is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Example of 1‐Day Dietary Intake for Ambulatory Patient With Cirrhosis

| Patient information | |

| Dry weight | 80 kg |

| Nutrient requirements | 2400‐2800 kcal/day, 80‐120 g/protein/day |

| Meals | |

| Breakfast | 2 eggs, 1 slice sprouted grain toast with butter and jam |

| Snack | 2 tablespoons peanut butter with apple, 8 oz soy milk |

| Lunch | Bean burrito (12‐inch flour tortilla with 3/4 cup refried beans, 1/2 cup shredded cheddar cheese) |

| Snack | 6 oz greek yogurt |

| Dinner | 3 oz chicken breast, 3 medium asparagus spears, 1 cup cooked wild rice |

| Bedtime snack | 1 cup ice cream |

| Nutrient totals | 2400 kcal, 120 g protein |

Nutrition Priority Four: Protein Source

Once a patient is meeting the earlier nutrition recommendations, then a discussion regarding the source of protein may be the next step in optimizing nutrition care. Patients may benefit from a higher percentage of protein intake from plant‐based and dairy‐sourced protein (Table 3). One pathophysiological reason to support protein from plant‐based and dairy sources is an increased intake of branched‐chain amino acids (BCAAs) found within these foods.6, 7 Because of the changes in amino acid metabolism and insulin resistance in patients with cirrhosis, there is an imbalance of BCAAs available for protein synthesis in skeletal muscle.8 Increased intake of BCAA intake may improve appetite, increase muscle synthesis, and have an impact in improving quality of life.7, 9 However, more randomized controlled studies comparing isonitrogenous (i.e., same total protein provision, but with composition from different food sources) interventions and their impact on outcomes are needed to provide more definitive recommendations. It should be noted that patients should not be discouraged from consuming animal‐based proteins, because it can be difficult to meet total protein needs without consumption of those foods. However, there is no harm and it is likely beneficial to encourage plant‐ and dairy‐based protein sources to a patient.

Table 3.

Protein Content of Selected Food Sources

| Dairy | |

| Cow's milk (1 cup) | 8 g |

| Greek yogurt (7 oz) | 20 g |

| Cottage cheese (4 oz) | 13 g |

| Cheese (1 oz) | 7 g |

| Ice cream (1 cup) | 4 g |

| Grain | |

| Lentils (1/2 cup cooked) | 9 g |

| Sprouted grain bread (1 slice) | 4 g |

| Quinoa (1/2 cup cooked) | 4 g |

| Wild rice (1/2 cup cooked) | 3.5 g |

| Vegetable | |

| Soy milk (1 cup) | 8 g |

| Peas (1 cup) | 8 g |

| Beans (1/2 cup) | 7‐10 g |

| Peanut butter (2 tablespoons) | 8 g |

| Nuts (1 oz) | 6 g |

| Pumpkin seeds (1 oz) | 9 g |

| Almonds (1 oz) | 6 g |

| Broccoli (1 cup) | 2.5 g |

| Corn (1 cup) | 4 g |

| Soy beans (edamame, 1/2 cup) | 8.5 g |

| Asparagus (3 medium spears) | 1.5 g |

| Brussel sprouts (1 cup) | 3 g |

| Artichokes (1 medium) | 4 g |

| Protein powder | |

| Whey (1 scoop) | 25 g |

| Casein (1 scoop) | 25 g |

| Pea (1 scoop) | 25 g |

| Animal based | |

| Egg (1 large) | 6 g |

| Chicken (1 oz) | 7 g |

| Beef (1 oz) | 7 g |

| Pork (1 oz) | 7 g |

| Fish (1 oz) | 7 g |

Overall, aggressive and early nutrition care, ideally provided by a registered dietitian, as a part of the patient's overall medical management is crucial to improvement in clinical outcomes. Given the risk for and prevalence of malnutrition in this patient population, nutrition assessment and education should be done at regular intervals.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Cheung K, Lee SS, Raman M. Prevalence and mechanisms of malnutrition in patients with advanced liver disease, and nutrition management strategies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:117‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Plauth M, Cabre E, Riggio O, et al. ESPEN guidelines on enteral nutrition: liver disease. Clin Nutr 2006;25:285‐294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Medici V, Mendoza MS, Kappus MR. Liver disease In: Mueller CM, ed. The ASPEN Adult Nutrition Support Core Curriculum, 3rd edn Silver Spring, MD: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cordoba J, Lopez‐Hellin J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol 2004;41:38‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, et al. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology 2013;58:325‐336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amodio P, Caregaro L, Patteno E, et al. Vegetarian diets in hepatic encephalopathy: facts or fantasies? Dig Liver Dis 2001;33:492‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ruiz‐Margáin A, Macias‐Rodriguez RU, Rios‐Torres SL, et al. Effect of a high‐protein, high‐fiber diet plus supplementation with branched‐chain amino acids on the nutritional status of patients with cirrhosis. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2018;83:9‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mouzaki M, Ng V, Kamath BM, et al. Enteral energy and macronutrients in end‐stage liver disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014;38:673‐681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hidaka H, Nakazawa T, Kutsukake S, et al. The efficacy of nocturnal administration of branched‐chain amino acid granules to improve quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol 2013;48:269‐276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]