Abstract

A recurring theme in the evolution of tetrapods is the shift from sprawling posture with laterally orientated limbs to erect posture with the limbs extending below the body. However, in order to invade particular locomotor niches, some tetrapods secondarily evolved a sprawled posture. This includes moles, some of the most specialized digging tetrapods. Although their forelimb anatomy and posture facilitates burrowing, moles also walk long distances to forage for and transport food. Here, we use X-ray Reconstruction Of Moving Morphology (XROMM) to determine if the mole humerus rotates around its long axis during walking, as it does when moles burrow and echidnas walk, or alternatively protracts and retracts at the shoulder in the horizontal plane as seen in sprawling reptiles. Our results reject both hypotheses and demonstrate that forelimb kinematics during mole walking are unusual among those described for tetrapods. The humerus is retracted and protracted in the parasagittal plane above, rather than below the shoulder joint and the ‘false thumb’, a sesamoid bone (os falciforme), supports body weight during the stance phase, which is relatively short. Our findings broaden our understanding of the diversity of tetrapod limb posture and locomotor evolution, demonstrate the importance of X-ray-based techniques for revealing hidden kinematics and highlight the importance of examining locomotor function at the level of individual joint mobility.

Keywords: tetrapod, locomotion, walk, forelimb, humerus, sesamoid bone

1. Introduction

Early tetrapods had a sprawling posture with limbs extending laterally, but throughout the evolution of tetrapods, the limbs have often migrated to a position beneath the body, in order to provide an upright stance [1–4]. Erect posture is one of many vertebrate transitions associated with energy savings that evolved in concert with ever-increasing metabolic demands; it confers energy savings by supporting body weight more directly along the long axes of limb bones, reducing the forces and energy required of limb extensors [2,5]. Erect posture also relaxes constraints on limb–substrate interactions by reducing lateral body undulations associated with a sprawling gait, decoupling breathing from locomotion [6], improving stamina [7] and allowing animals with erect posture to move faster [1,8]. Despite the apparent advantages of an upright stance, a few mammals have undertaken the evolutionary invasion of locomotor niches associated with a secondarily derived, sprawling posture. These include semi-aquatic species that use their limbs to swim, such as seals, sea lions, walrus, otters and platypus, and true moles (family Talpidae), which live their lives almost completely underground.

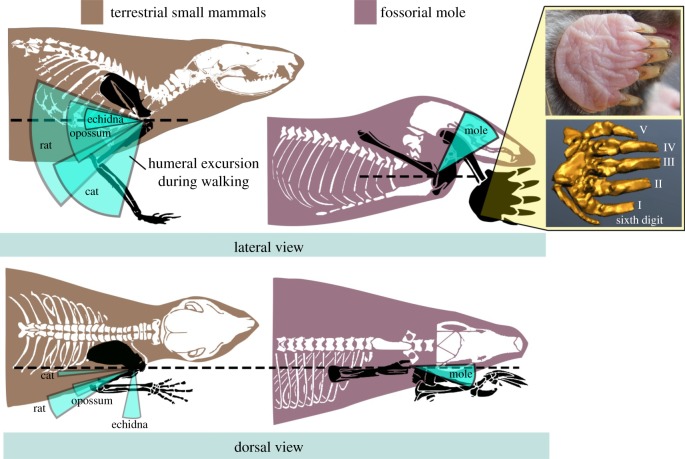

Moles are highly specialized digging vertebrates and exhibit a highly exaggerated sprawling stance (figure 1). Their short, broad humerus (upper arm bone) extends dorsally and cranially (upward and forward, respectively) from the shoulder joint. Their palm, which is significantly widened by a ‘false thumb’ (os falciforme or sixth digit), faces laterally and away from the body. With this forelimb anatomy and posture, moles can compress loose soil into the walls of their tunnels [10] instead of transporting soil to the surface [10,11] at the expense of metabolic energy [12]. Eastern moles occupy home ranges exceeding 10 000 m2 [13], which is 23–42 times larger than the home ranges of burrowing pocket gophers of similar size [14]. Individuals negotiate over 400 m of tunnel daily to forage for and transport food [13]. This distance is more than 2650 times a mole's body length and is equivalent to a 4.5 km walk for a 1.75 m tall human. Walking is probably a significant portion of a mole's daily energy budget. A recent kinematic study revealed that mole forelimb kinematics involve a significant component of long-axis rotation during burrowing [10], but we know little about how this extremely specialized forelimb moves during walking.

Figure 1.

Humeral excursion and manus (hand) orientation during walking differs between moles and other terrestrial mammals. Lateral and dorsal views of humeral movements are illustrated as excursion arcs around the shoulder joint (light blue) relative to the horizontal plane in small mammals [9] and moles (this study). The mole manus (gold) faces laterally with the ‘false thumb’ lateral to Digit I (the homologue of the human thumb).

Here, we use the X-ray Reconstruction Of Moving Morphology (XROMM [15]) to test two hypotheses about kinematics at the mole shoulder joint during walking. The first hypothesis is that the primary movement is rotation around the long axis of the humerus (humeral pronation/supination), which is the main driver of mole burrowing movements [10,16] and of walking in echidnas [9,17]. The second hypothesis is that movement at the shoulder is dominated by retraction/protraction in the horizontal plane, compared with the long-axis rotation, as seen in reptiles with sprawling postures [18–20]. We test these hypotheses by quantifying relative movements at the shoulder, elbow and the ‘false thumb’ across the stance and swing phases of the walking gait cycle.

2. Results

Moles walk at a speed of 20.8 ± 2.2 cm s−1 Supplemental video S1 - video mole walking with a duty factor of 0.56 ± 0.02 (table 1). The dominating humeral motion is protraction/retraction (62–109°; range-of-motion = 47°), compared with pronation/supination (93–122°; range-of-motion = 28°) at the shoulder joint (table 1). Humeral movements mainly occur above the horizontal plane (see excursion arc in figure 1, top right and Supplemental video S2 - XROMM dorsal) and in the parasagittal plane (see excursion arc in figure 1, bottom right and Supplemental video S3 - XROMM lateral).

Table 1.

Stride parameters and movements of humerus (mean ± s.e.m.) during mole walking. Rx, movement along x-axis (abduction/adduction); Ry, movement along y-axis (protraction/retraction); Rz, movement along z-axis (supination/pronation); ROM, range-of-motion (max. angle–min. angle). Trials: four cycles from each of three individuals (total of 12 cycles).

| stride parameter |

shoulder joint angle |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| individual | speed (cm s−1) | contact time (s) | swing time (s) | stride length (cm) | stride frequency (Hz) | duty factor | individual |

Rx | Ry | Rz | |

| no. 1 | 21.9 ± 3.7 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 1.0 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | max. | no. 1 | 6.7 ± 1.9 | 108.2 ± 0.6 | 131.5 ± 1.1 |

| no. 2 | 12.9 ± 1.1 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | no. 2 | 14.6 ± 2.1 | 103.8 ± 3.1 | 111.1 ± 2.0 | |

| no. 3 | 27.6 ± 1.7 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | no. 3 | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 114.8 ± 1.7 | 123.7 ± 1.9 | |

| mean | 20.8 ± 2.2 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | mean | 9.7 ± 1.4 | 108.9 ± 1.7 | 122.1 ± 2.7 | |

| min. | no. 1 | −11.9 ± 5.2 | 54.1 ± 2.0 | 101.4 ± 1.7 | |||||||

| no. 2 | 0.88 ± 0.6 | 66.2 ± 3.4 | 88.0 ± 1.0 | ||||||||

| no. 3 | −3.7 ± 3.4 | 65.4 ± 6.1 | 92.4 ± 2.5 | ||||||||

| mean | −4.9 ± 2.5 | 61.9 ± 2.8 | 93.9 ± 1.9 | ||||||||

| ROM | no. 1 | 18.7 ± 3.6 | 54.1 ± 1.7 | 30.1 ± 2.2 | |||||||

| no. 2 | 13.7 ± 2.2 | 37.7 ± 4.9 | 23.2 ± 1.6 | ||||||||

| no. 3 | 11.4 ± 3.0 | 49.4 ± 6.6 | 31.3 ± 1.2 | ||||||||

| mean | 14.6 ± 1.8 | 47.0 ± 3.3 | 28.2 ± 1.4 | ||||||||

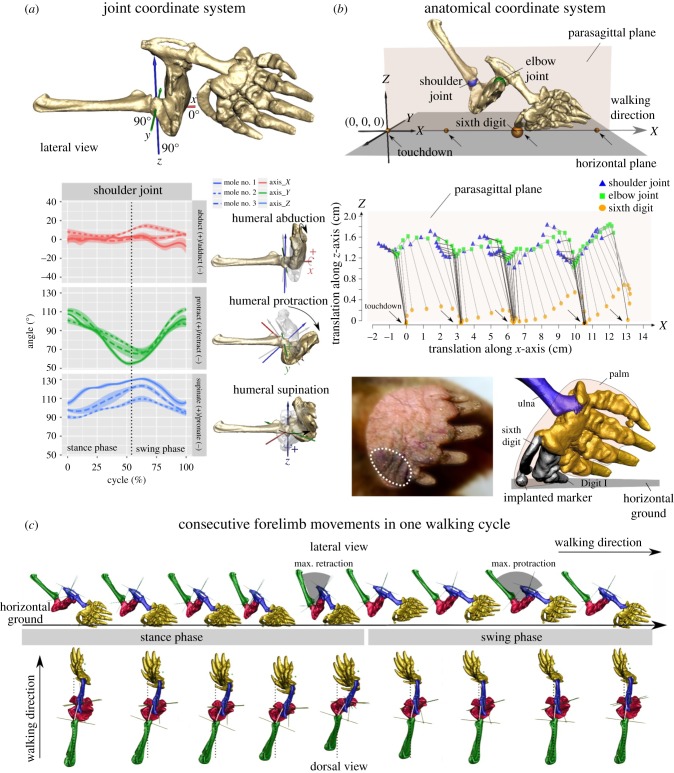

During the swing, the humerus is protracted (figure 2a) and reaches maximum protraction before the ‘false thumb’ contacts the ground (figure 2c). During stance, the ‘false thumb’ always remains cranial to the shoulder and elbow joints (figure 2b, middle panel). Only the ‘false thumb’ and Digit I make ground-contact during walking (figure 2b, bottom panel). The ‘false thumb’ makes the first contact, followed by Digit I, together forming a stable support.

Figure 2.

Forelimb kinematics during walking. (a) Joint coordinate system (JCS) of humeral movements during mole walking. The coordinate system origin is defined as the midpoint of a line connecting the lateral and medial sides of the humeral head (a) [16]. The JCS z-axis is aligned with the humerus long axis (supination (+z) /pronation (−z)) and the y-axis is parallel with the plane that passes through the width of the relatively flat humerus (humeral plane; protraction (+y)/retraction (−y)) (a, top panel). A JCS reference angle is defined as describing joint movements relative to a neutral position in which the humeral plane is perpendicular to the scapular long axis and the humeral long axis is parallel to the glenoid fossa (shoulder joint). In this position, the humeral XYZ relative to scapula is 0°, 90°, 90°. Humerus movements relative to scapula are then described along x- (red, abduction+/adduction−), y- (green, extension+/flexion−) and z-axes (blue, supination+/pronation−). The dotted line indicates toe-off. (b) Displacements of the shoulder (blue sphere) and elbow (green sphere) joints and the pivot (orange sphere) of the ‘false thumb’ in the anatomical coordinate system (ACS). The ACS origin is defined as the location of the ‘false thumb’ at the initiation of the contact phase during the first gait cycle. The ACS x-axis is aligned with the walking direction, defined as a line intersecting each point at which the ‘false thumb’ first contacted the ground (small orange spheres in b); the z-axis is perpendicular to the horizontal plane (i.e. vertical). The displacements of joint centres and ‘false thumb’ along x-, y-, z-axes were tracked to illustrate their movements in the cranial (+x) and caudal (−x), lateral (+y) and medial (−y), and dorsal (+z) and ventral (−z) directions. Middle panel: Locations of each joint/pivot in the x- and z-axes projected onto the parasagittal plane (light orange plane in the top panel) during movement along the x-axis. Arrows indicate ‘false thumb’ touchdowns and beginning of stance phase. Bottom panel: White broken circle represents the mole palm area that touched an inkpad on the ground during walking. Bones that make ground-contact are coloured black. (c) Forelimb movements during a walking gait cycle; top panel: in a lateral view, bottom panel: in a dorsal view. Grey arcs illustrate peak shoulder flexion and extension. White line indicates the long axis of humerus. Scapula (green), humerus (red), ulna (blue) and manus (gold).

3. Discussion

Moles walk with forelimb movements that are unusual in several ways, compared with tetrapods with sprawling postures [17,18,21], and with terrestrial quadrupedal mammals, including those with a more upright posture [1,9,22–24]. Similar to sprawling reptiles and salamanders [18,25] as well as terrestrial mammals [9,26], the mole humerus is protracted and retracted during walking. Particularly noteworthy, however, is the fact that humeral retraction occurs above, rather than in or below the horizontal plane (figure 1).

Throughout the mole walking gait cycle, the ground-contact point remains cranial to the shoulder and elbow joints (figure 2). This pattern is akin to how humans use a cane or walker to assist ambulation. The sixth digit is placed on the ground in front of the body, which then moves forward to meet it. This ambulatory pattern differs fundamentally from all other terrestrial tetrapods studied to date, where the distal-most forelimb element (hoof, pad or palm) stays caudal to the shoulder during stance [17–21,27]. Only Digit I (homologous to the human thumb) and the ‘false thumb’, on the medial aspect of the mole palm touch the ground, suggesting that the ‘false thumb’, a sesamoid bone, supports the mole's body weight much like the radial sesamoid bone of elephants bears body weight when foot posture is altered [28,29].

Humeral movements during mole walking differ substantially from the major element of humeral long-axis rotation seen during burrowing [10,16]. Changes in humeral orientation and kinematics between burrowing and walking likely require muscles of the shoulder and forelimb to operate across very different ranges of fibre lengths. The lower force requirements for walking compared with burrowing may mean that muscles of the shoulder can stretch beyond their optimal length for force generation during walking [30]. This may, in turn, facilitate the exaggerated extension at the shoulder maintained during walking. Studies are needed to determine how muscle and joint operating lengths and ranges are altered with respect to burrowing and locomotion patterns in moles.

Humerus long-axis rotation is not a key kinematic component of mole walking, as previously documented for another burrowing locomotor specialist with sprawling posture, the echidna [9,17]. Differences in mole and echidna forelimb movements may be linked to their fundamentally different gaits; echidnas use a pace-like walking gait, moving limbs on one side together, resulting in a noticeable side-to-side (yaw) motion of the trunk [31]. By contrast, moles have a symmetrical gait with diagonal limbs making synchronous ground-contact (electronic supplementary material, videos S1–S3). Lateral body undulations are reduced as a result, and similar in magnitude to those generally observed during walking in upright tetrapods [6,32].

Moles walk at speeds similar to ‘high walking’ alligators, geckos, skinks and similarly sized ground squirrels and chipmunks (10–20 cm s−1, [32–35]). However, the significantly lower duty factor of mole walking compared with ‘high-walkers’ and slow-moving mammals such as sloths and lorises (0.56 compared with 0.70–0.90 [36–38]) means that moles walk more like race-walking humans, and approach the kinematics cut-off defining running (less than 0.5 [32]). The fact that moles do not extend their stance phase by letting the shoulder move past the hand may be linked to the relatively low duty factor, and provide the narrow-body profile that enables moles to move quickly in their expansive yet tight tunnel networks during foraging. Whether moles use their forelimbs to generate propulsion during walking, like vampire bats [39], or propel themselves with their hind limbs like generalized tetrapods [40] including dogs [41], squirrels and chipmunks [33] warrants further study.

Our results broaden our understanding of the evolutionary diversity of tetrapod limb posture and locomotion, demonstrate the importance of X-ray techniques in revealing hidden movements during tetrapod locomotion, and highlight the power of examining how joint mobility contributes to locomotor function [42,43].

4. Methods

(a). Animals

Three eastern moles (Scalopus aquaticus, 94.7 ± 10.2 g) were captured in Hadley, MA, and housed in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use protocols at University of Massachusetts Amherst and Brown University. At Brown University, subjects were anaesthetized for implantation of radio-opaque markers by sterile surgery. The procedure is described in depth elsewhere [10], but briefly: we implanted a 1 mm spherical tantalum marker in the right scapula, three to four 0.5 mm tantalum makers in the right humerus, and two 0.5–1 mm markers in the right ulna. Three 0.5 mm tantalum markers were implanted subcutaneously in the palm: underneath the medially positioned ‘false thumb’ and at the base of the third (mid) and fifth (lateral) digits. The three moles recovered from surgery and resumed normal feeding and burrowing within 3 days. The sample is minimal owing to difficulties inherent to keeping moles and getting them through the research pipeline.

(b). Data collection

Animals voluntarily walked in a rectangular box-enclosure, custom-fashioned from radiotranslucent polycarbonate (20H × 7W × 50L cm), and fitted with anti-slip tape on the flat ground surface, to encourage normal locomotion while facilitating the use of biplanar video fluoroscopy (Imaging Systems and Service, 55 kVp/250 mA, retrofitted with Phantom, v.10 high-speed cameras (Vision Research; 90 Hz frame rate, 1/250 s shutter speed) to determine how the mole forelimb made ground-contact. The box was wide enough for animals to walk without touching the walls but narrow enough to keep them walking forward in a straight line. The world coordinate axis was marked using tantalum markers in the enclosure floor. After walking trials, subjects were euthanized for computed tomography scanning to build 3D models of the forelimb skeletal elements (scapula, humerus, ulna and manus) as well as the marker implants (Mimics v. 16.0 and Geomagic Studio v. 12).

(c). Forelimb motion analysis

We used established marker-based videofluoroscopy workflows [15,44,45] to construct digital models and calculate forelimb joint kinematics for four consecutive walking cycles from each individual. The XROMM workflow [15] was used for bones implanted with at least three markers (humerus, manus). Scientific Rotoscoping [44] was used to align 3D models of bones with fewer than three markers (scapular and ulna) to match their positions in both X-ray images.

We ran two analyses. One describes humeral movements at the shoulder joint within a joint coordinate system (figure 2a). The second analysis sought to determine the trajectory of the forelimb joints and the ‘false thumb’ relative to the ground as well as the movement trajectory of the animal. Therefore, we visualized the relative 3D locations of the shoulder, elbow and ‘false thumb’ (blue, green and orange spheres in figure 2b, respectively), tracking their global coordinates over time.

We calculated mean values and standard errors for angular movements at the shoulder joint and XYZ displacement of the shoulder and elbow joint centres and the ‘false thumb’ from each individual by normalizing data over each gait cycle to 0–100% of the stroke cycle using cubic spline interpolation [46]. Stance and swing phase durations and the contact duty factor (percentage of the stride where the forelimb touches the ground) were calculated for each gait cycle. Walking speed was defined as the 3D displacement of a body landmark per second (cm s−1), averaged across all strides within a given trial, and stride frequency was defined as the inverse of stride duration.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas Roberts for assistance with surgeries, Angela Horner for discussion of the experimental design, Elizabeth Brainerd, David Baier, Ariel Camp and Peter Falkingham for XROMM support, and Paul Spurlock, Joanne Huyler and Animal Care Services of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Brown University for animal husbandry.

Data accessibility

Data analysed for this study is provided on Dryad (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5qp11c9) [47].

Authors' contributions

Study conceptualization and design: Y.-F.L., E.R.D. Data acquisition: Y.-F.L., E.R.D., N.K. Analysis and interpretation of data: Y.-F.L. Drafting of the manuscript: Y.-F.L., N.K. Editing: Y.-F.L., E.R.D., N.K. Final approval of the version to be published: Y.-F.L., E.R.D., N.K. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation grant no. IOS-1407171, Sigma Xi Committee on Grants-in-Aid of Research G2012162703 and the Natural History Collections, and the Graduate Program in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

References

- 1.Bakker RT. 1971. Dinosaur physiology and the origin of mammals. Evolution 25, 636–658. ( 10.2307/2406945) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biewener AA. 1990. Biomechanics of mammalian terrestrial locomotion. Science 250, 1097–1103. ( 10.1126/science.2251499) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrier DR. 1987. The evolution of locomotor stamina in tetrapods: circumventing a mechanical constraint. Paleobiology 13, 326–341. ( 10.1017/S0094837300008903) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crompton AW, Jenkins FA Jr. 1973. Mammals from reptiles: a review of mammalian origins. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 1, 131–155. ( 10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biewener AA. 1989. Scaling body support in mammals: limb posture and muscle mechanics. Science 245, 45–48. ( 10.1126/science.2740914) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bramble D, Carrier D. 1983. Running and breathing in mammals. Science 219, 251–256. ( 10.1126/science.6849136) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett A., Ruben J. 1979. Endothermy and activity in vertebrates. Science 206, 649–654. ( 10.1126/science.493968) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garland T., Jr 1982. Scaling maximal running speed and maximal aerobic speed to body mass in mammals and lizards. Physiologist 25, 338. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins FA. 1971. Limb posture and locomotion in the Virginia opossum (Didelphis marsupialis) and in other non-cursorial mammals. J. Zool. 165, 303–315. ( 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1971.tb02189.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Y-F, Konow N, Dumont ER. 2019. How moles destroy your lawn: the forelimb kinematics of eastern moles in loose and compact substrates. J. Exp. Biol. 224, jeb.182436 ( 10.1242/jeb.182436) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin YF, Chappuis A, Rice S, Dumont ER. 2017. The effects of soil compactness on the burrowing performance of sympatric eastern and hairy-tailed moles. J. Zool. 301, 310–319. ( 10.1111/jzo.12418) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vleck D. 1979. The energy costs of burrowing by the pocket gopher Thommomys bottae. Physiol. Zool. 52, 122–136. ( 10.1086/physzool.52.2.30152558) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey MJ. 1976. Home range, movements, and diel activity of the eastern mole, Scalopus aquaticus. Am. Midl. Nat. 95, 436–445. ( 10.2307/2424406) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yates TL, Schmidly DJ. 1978. Scalopus aquaticus. Mamm. Species 105, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brainerd EL, Baier DB, Gatesy SM, Hedrick TL, Metzger KA, Gilbert SL, Crisco JJ. 2010. X-ray reconstruction of moving morphology (XROMM): precision, accuracy and applications in comparative biomechanics research. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 313, 262–279. ( 10.1002/jez.589) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed CA. 1951. Locomotion and appendicular anatomy in three soricoid insectivores. Am. Midl. Nat. 45, 513–671. ( 10.2307/2421996) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins FA. 1970. Limb movements in a monotreme (Tachyglossus aculeatus): a cineradiographic analysis. Science 168, 1473–1475. ( 10.1126/science.168.3938.1473) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baier DB, Gatesy SM. 2013. Three-dimensional skeletal kinematics of the shoulder girdle and forelimb in walking alligator. J. Anat. 223, 462–473. ( 10.1111/joa.12102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gambaryan PP, Gasc JP, Renous S. 2002. Cinefluorographical study of the burrowing movements in the common mole, Talpa europaea (Lipotyphla, Talpidae). Russ. J. Theriol. 1, 91–109. ( 10.15298/rusjtheriol.01.2.03) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins FA, Goslow GE. 1983. The functional anatomy of the shoulder of the savannah monitor lizard (Varanus exanthematicus). J. Morphol. 175, 195–216. ( 10.1002/jmor.1051750207) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambaryan PP. 2002. Evolution of tetrapod locomotion. Zh. Obshcheĭ Biol. 63, 426–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charig AJ. 1972. The evolution of the archosaur pelvis and hindlimb: an explanation in functional terms (eds Joysey KA, Kemp TS), pp. 121–155. Edinburgh, UK: Oliver & Boyd. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory WK. 1912. Notes on the principles of quadrupedal locomotion and the mechanism of the limbs in hoofed animals. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 22, 267–294. ( 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1912.tb55164.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kardong K. 1995. Vertebrates: comparative anatomy, function, evolution. Dubuque, IA: Wm C. Brown Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashley-Ross MA, Lundin R., Johnson KL. 2009. Kinematics of level terrestrial and underwater walking in the California newt, Taricha torosa. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 311A, 240–257. ( 10.1002/jez.522) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer MS, Schilling N, Schmidt M, Haarhaus D, Witte H. 2002. Basic limb kinematics of small therian mammals. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 1315–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnan MF, Shulman J, Varadharajan R, Gilbert C, Wilkes M, Horner A, Brainerd E. 2016. Forelimb kinematics of rats using XROMM, with implications for small eutherians and their fossil relatives. PLoS ONE 11, e0149377 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0149377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutchinson JR, Delmer C, Miller CE, Hildebrandt T, Pitsillides AA, Boyde A. 2011. From flat foot to fat foot: structure, ontogeny, function, and evolution of elephant ‘Sixth Toes’. Science 334, 1699–1703. ( 10.1126/science.1211437) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panagiotopoulou O, Pataky TC, Day M, Hensman MC, Hensman S, Hutchinson JR, Clemente CJ. 2016. Foot pressure distributions during walking in African elephants (Loxodonta africana). R. Soc. open sci. 3, 160203 ( 10.1098/rsos.160203) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lutz G., Rome L. 1994. Built for jumping: the design of the frog muscular system. Science 263, 370–372. ( 10.1126/science.8278808) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gambaryan PP, Kuznetsov AN. 2013. An evolutionary perspective on the walking gait of the long-beaked echidna. J. Zool. 290, 58–67. ( 10.1111/jzo.12014) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biewener AA. 2006. Patterns of mechanical energy change in tetrapod gait: pendula, springs and work. J. Exp. Zool. A Comp. Exp. Biol. 305A, 899–911. ( 10.1002/jez.a.334) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biewener AA. 1983. Locomotory stresses in the limb bones of two small mammals: the ground squirrel and chipmunk. J. Exp. Biol. 103, 131–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farley CT, Ko TC. 1997. Mechanics of locomotion in lizards. J. Exp. Biol. 200, 2177–2188. ( 10.1242/jeb.00761) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willey JS, Biknevicius AR, Reilly SM, Earls KD. 2004. The tale of the tail: limb function and locomotor mechanics in Alligator mississippiensis. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 553–563. ( 10.1242/jeb.00774) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biewener AA. 1983. Allometry of quadrupedal locomotion: the scaling of duty factor, bone curvature and limb orientation to body size. J. Exp. Biol. 105, 147–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nyakatura JA, Andrada E. 2013. A mechanical link model of two-toed sloths: no pendular mechanics during suspensory locomotion. Acta Theriol. 58, 83–93. ( 10.1007/s13364-012-0099-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Granatosky MC, Schmitt D. 2017. Forelimb and hind limb loading patterns during below branch quadrupedal locomotion in the two-toed sloth. J. Zool. 302, 271–278. ( 10.1111/jzo.12455) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riskin DK, Hermanson JW. 2005. Biomechanics: independent evolution of running in vampire bats. Nature 434, 292 ( 10.1038/434292a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biewener A, Patek S. 2018. Animal locomotion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee DV, Bertram JE, Todhunter RJ. 1999. Acceleration and balance in trotting dogs. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 3565–3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierce SE, Ahlberg PE, Hutchinson JR, Molnar JL, Sanchez S, Tafforeau P, Clack JA. 2013. Vertebral architecture in the earliest stem tetrapods. Nature 494, 226–229. ( 10.1038/nature11825) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierce SE, Clack JA, Hutchinson JR. 2012. Three-dimensional limb joint mobility in the early tetrapod Ichthyostega. Nature 486, 523–526. ( 10.1038/nature11124) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gatesy SM, Baier DB, Jenkins FA, Dial KP. 2010. Scientific rotoscoping: a morphology-based method of 3-D motion analysis and visualization. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 313, 244–261. ( 10.1002/jez.588) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Knörlein BJ, Baier DB, Gatesy SM, Laurence-Chasen JD, Brainerd EL. 2016. Validation of XMALab software for marker-based XROMM. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 3701–3711. ( 10.1242/jeb.145383) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Neill MC, Lee LF, Demes B, Thompson NE, Larson SG, Stern JT, Umberger BR. 2015. Three-dimensional kinematics of the pelvis and hind limbs in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and human bipedal walking. J. Hum. Evol. 86, 32–42. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.05.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin Y-F, Konow N, Dumont ER. 2019. Data from: How moles walk; it's all thumbs Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.5qp11c9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Lin Y-F, Konow N, Dumont ER. 2019. Data from: How moles walk; it's all thumbs Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.5qp11c9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data analysed for this study is provided on Dryad (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.5qp11c9) [47].