Abstract

The candidate pan-Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine RG1-VLP are HPV16 major capsid protein L1 virus-like-particles (VLP) comprising a type-common epitope of HPV16 minor capsid protein L2 (RG1; aa17–36). Vaccinations have previously demonstrated efficacy against genital high-risk (hr), low-risk (lr) and cutaneous HPV.

To compare RG1-VLP to licensed vaccines, rabbits (n = 3) were immunized thrice with 1 mg, 5 mg, 25 mg, or 125 mg of RG1-VLP or a 1/4 dose of Cervarix®.5 mg of RG1-VLP or 16L1-VLP (Cervarix) induced comparable HPV16 capsid-reactive and neutralizing antibodies titers (62,500/12,500–62,500 or 1000/10,000). 25 mg RG1-VLP induced robust cross-neutralization titers (50–1000) against hrHPV18/31/33/45/52/58/26/70. To mimic reduced immunization schedules in adolescents, mice (n = 10) were immunized twice with RG1-VLP (5 µg) plus 18L1-VLP (5 µg). HPV16 neutralization (titers of 10,000) similar to Cervarix and Gardasil and cross-protection against hrHPV58 vaginal challenge was observed.

RG1-VLP vaccination induces hrHPV16 neutralization comparable to similar doses of licensed vaccines, plus cross-neutralization to heterologous hrHPV even when combined with HPV18L1-VLP.

1. Introduction

Persistent infection with ~15 different mucosal high-risk (hr) Human Papillomaviruses (HPV), most often HPV16 and 18, is the main cause of all cervical cancers and a subset of other anogenital and likely also oropharyngeal carcinomas. Mucosal low-risk (lr) HPV induce benign genital and laryngeal warts (condylomata). In addition, common cutaneous HPV types cause cutaneous, most frequently palmo-plantar warts, whereas the diverse group of cutaneous genus beta HPV have been implicated in the development of non-melanoma-skin-cancers (NMSC) in immunosuppressed individuals [1].

Licensed HPV vaccines are recombinant subunit vaccines, comprised of major capsid protein L1 self-assembled into virus-like particles (VLP), that are remarkably immunogenic and durably induce high-titer, type-restricted neutralizing antibodies [2–4]. Following prophylactic L1-VLP vaccination, the highly efficacious (close to 100% seroconversion) and enduring antibody response prevents infection and subsequent development of warts and anogenital dysplasias caused by the targeted vaccine types. Bivalent Cervarix® and quadrivalent (4v) Gardasil® target hrHPV16, 18 infections causing ~70% of cervical cancers (CxCa). The newest HPV vaccine, nonavalent (9v) Gardasil-9®, which contains L1-VLP of hrHPV16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58 and lrHPV6, 11 is predicted to protect against 90% of all CxCa. Moreover, vaccination with 4vGardasil or 9vGardasil-9, both also containing lrHPV6 and 11 L1 VLP, protects against 90% of all genital warts [5,6]. However, the realization of polyvalent L1-VLP vaccines, designed to protect against all high-risk HPV and other medically significant types, will be limited by manufacturing challenges.

As an alternative to more multivalent L1-VLP vaccines, the development of experimental vaccines based on the papillomavirus (PV) minor capsid protein L2 has been investigated in recent years [7]. Immunizations with L2 protein or peptides containing type-common motifs induce cross-neutralizing, yet lowtiter antibodies against divergent HPV types [8,9]. Improving the immunogenicity of L2 is therefore pivotal to provide effective L2-based HPV vaccines. We have previously generated chimeric HPV16L1-VLP which present the cross-neutralization epitope HPV16L2 aa17–36 (recognized by the cross-neutralizing monoclonal antibody RG1) within the DE-loop repetitively on the VLP surface, termed RG1-VLP. RG1-VLP, expressed in Sf-9 insect cells, were highly immunogenic in rabbits and mice using human applicable aluminiumhydroxide plus monophosphoryl lipid A (alum/MPL) adjuvant, inducing cross-neutralizing antibodies against a broad range of hrHPV, lrHPV, common cutaneous and beta HPV types. Cross-protection against experimental challenge in vivo was demonstrated for all relevant mucosal hrHPV (HPV16/18/45/31/33/52/58/35/39/51/59/68/56/73/26/53/66/34) and lrHPV (HPV6/43/44) [10,11].

Based on these promising preclinical results, RG1-VLP is currently produced under cGMP for a planned first-in-human clinical trial (supported by the US NCI PREVENT program). An outstanding feature of RG1-VLP, when compared to other L2-based vaccine approaches, is the very close resemblance with wild-type HPV16L1-VLP contained in licensed vaccines, suggesting a similar safety profile when using similar antigen/adjuvant doses. To support a planned phase I clinical study in humans the herein presented dose-finding study was performed to initially evaluate (a) efficacy of RG1-VLP vaccine compared to wild-type HPV16 VLP in raising HPV16L1-specific antibodies, (b) dose-dependency of cross-neutralizing L2 antibodies induced by RG1-VLP, (c) a possible use of RG1-VLP in a 2 dose vaccination regime, and (d) a bivalent RG1-VLP + 18L1-VLP vaccine formulation. All questions were to be answered in the setting of adjuvant formulations and doses applicable in humans. This vaccine study presents earliest and descriptive data from a limited number of animals on the questions addressed.

2. Results

Proof-of-principle vaccination studies in New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits have demonstrated induction of cross-protective antibodies against numerous hrHPV and lrHPV, and cross-neutralization against cutaneous HPV types using 3 or 4 doses of 20 µg or 50 µg RG1-VLP adjuvanted with alum/MPL.

Here, dose finding studies were performed to support informed decisions on planned phase I RG1-VLP trials in humans. RG1-VLP were baculovirus-expressed in Sf9 insect cells and purificated on sucrose and CsCl gradients as described earlier on [10]. Following characterization of VLP assembly and 16L1 and RG1 protein expression using Transmission Electron Microscopy and Western Blot [10], RG1-VLP were immunologically characterized using a panel of monoclonal antibodies to HPV16L1 (kindly provided by N. Christensen; data unpublished). Similarly characterized cGMP produced RG1-VLP were not available for the study. NZW rabbits (groups of n = 3) were immunized using increasing doses of 1 µg (“RG1–1”), 5 µg (“RG1–5”), 25 µg (“RG1–25”), or 125 µg (“RG1–125”) of RG1-VLP combined with a fixed amount of alum/MPL (125µg/12,5 mg) adjuvants, or 1/4 vial of Cervarix (corresponding to 5 µg of 16L1-VLP, adjuvanted with ASO4, containing 12,5 µg of 3-O-desacyl-4-monophosphoryl-lipid A and 125 µg of Al3+) on days 0, 60 and 120 (Table 1). Additionally, one group of NZW rabbits was vaccinated twice with 5 mg RG1-VLP plus alum/MPL (“RG1–5 (2x)”) on days 0 and 120. Sera were drawn on day 134 and tested in HPV16L1-VLP Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and RG1 peptide ELISA, allowing a clear differentiation and quantification of both L1-specific and L2-specific antibody responses. To further characterize and quantify the subset of neutralizing antibodies, sera were analyzed for (cross-)neutralizing antibodies against hrHPV16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, 26, 70 in Pseudovirion-based Neutralization Assays (PBNA). Antibody titers for each individual animal are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

RG1-VLP Dose Escalation Immunization of NZW Rabbits. New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits in groups of n = 3 animals were immunized 3x (days 0, 60, 120) with 1 µg (“RG1–1”), 5 µg (“RG1–5”), 25 µg (“RG1–25”) or 125 µg (“RG1–125”) of RG1-VLP plus adjuvant (125 µg of aluminium hydroxide and 12,5 µg of MPL); or with 125 µl of Cervarix (“Cervarix”); or 2x (days 0, 120) with 5 µg of RG1-VLP similarly adjuvanted (“RG1–5 (2x)”). Sera were drawn before and 14 days after the final boost and analyzed for HPV16L1-VLP- and RG1-peptide-specific antibodies by ELISA, and for (cross-)neutralizing antibodies in standard PBNA (hrHPV16/18) or a modified PBNA providing improved detection of L2-specific neutralizing antibodies (hrHPV31/33/45/52/58/26/70). Antibody titers are given for individual rabbit sera. The geometric mean titer (GMT) of L2-specific cross-neutralization against HPV18, 26, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, and 70 is indicated in [] for every animal (rounded to whole numbers). RG1, RG1-VLP; 16, 16L1-VLP; 18, 18L1-VLP; alum, aluminium hydroxide; MPL, monophosphoryl lipid A; RG1pep, RG1 synthetic peptide; PBNA, pseudovirion-based neutralization assay.

| Group n = 3 | “RG1–1“ | “RG1–5“ | “RG1–25“ | “RG1–125“ | “RG1–5 (2x)“ | “Cervarix“ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VLP | RG1 | 16 | 18 | |||||

| µg/dose | 1 | 5 | 25 | 125 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| alum (µg) | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 | AlOH | ||

| MPL (µg) | 12,5 | 12,5 | 12,5 | 12,5 | 12,5 | 12,5 | ||

| NZW rabbit vaccination (d) | 0, 60, 120 | 0, 60, 120 | 0, 60, 120 | 0, 60, 120 | 0, 120 | 0, 60, 120 | ||

| ELISA | HPV16L1-VLP | 2500/2500/12,500 | 62,500/62,500/62,500 | 12,500/12,500/12,500 | 62,500/62,500/312,500 | 2500/2500/500 | 62,500/62,500/12,500 | |

| RG1pep | 500/2500/2500 | 2500/500/2500 | 2500/62,500/12,500 | 1.562,500/2500/62,500 | 2500/500/2500 | 0/0/0 | ||

| PBNA | HPV16 | 1000/100/100 | 1000/1000/1000 | 1000/1000/1000 | 10,000/10,000/100,000 | 1000/1000/50 | 10,000/10,000/10,000 | |

| HPV18 | 0/100/0 | 1000/100/0 | 100/100/100 | 100/100/1000 | 100/50/0 | 100,000/10,000/10,000 | ||

| HPV31 | 0/100/0 | 0/50/0 | 1000/100/0 | 100/100/50 | 0/0/0 | 100/100/0 | ||

| HPV52 | 0/1000/0 | 1000/100/0 | 1000/100/1000 | 0/100/0 | 0/0/0 | 0/0/0 | ||

| HPV45 | 0/100/0 | 0/100/0 | 1000/50/1000 | 1000/1000/0 | 0/0/0 | 100/0/0 | ||

| HPV33 | 0/1000/0 | 100/100/0 | 50/100/1000 | 100/1000/100 | 0/100/50 | 0/100/0 | ||

| HPV58 | 0/1000/0 | 100/100/0 | 100/100/1000 | 100/1000/100 | 100/0/50 | 0/0/0 | ||

| HPV26 | 0/100/0 | 100/50/0 | 1000/100/100 | 100/1000/1000 | 100/0/0 | 0/0/0 | ||

| HPV70 | 50/100/0 | 100/100/50 | 1000/100/100 | 100/10,000/10,000 | 100/0/0 | 100/0/0 | ||

| GMT of cross-neutralization (HPV18…HPV70)/NZW | [6]/[438]/[0] | [300]/[88]/[6] | [656]/[94]/[538] | [200]/[1788]/[1531] | [50]/[19]/[13] | – | ||

ELISA studies were performed using rabbit sera in 5-fold dilutions starting at 1:100. Sera from rabbits in group “RG1–5” elicited antibody titers against HPV16L1 similar to rabbits of group “Cervarix” (titers of 62,500 or 12,500–62,500, respectively). Mean titers were lower in groups “RG1–1” or “RG1–5 (2x)” (2500–12,500 or 500–2500). By RG1-ELISA, “RG1–1”, “RG1–5” and “RG1–5 (2x)” raised similar titers of antibodies (500–2500) reactive against the RG1-epitope, and improved titers were induced in higher dose groups “RG1–25” (2500–62,500) and “RG1–125” (2500–1.562,500). We next evaluated antisera for (cross-) neutralizing antibodies against hrHPV16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, 26, 70 in PBNA, performed as described previously (hrHPV16, 18), or in a modified protocol with improved sensitivity for L2-directed antibodies (hrHPV31, 45, 52, 58, 26, 70) [12,13]. In both types of PBNA assays sera were used at 1:50, 1:100, and consecutive serial 10-fold dilutions. Neutralization titers are reported as the reciprocals of the highest dilution causing ≥50% reduction of reporter plasmid activity, compared to preimmune sera of the same dilution. For sera that failed to neutralize at dilutions of 1:50 titer was designated 0.

Neutralization titers against HPV16 were 1000 in rabbits of “RG1–5” and RG1–25”, and 10,000 in animals of the “Cervarix” group, and titers were lower for groups “RG1–1” and “RG1–5 (2x)” (100–1000 and 50–1000). Cross-neutralizing antibodies against HPV18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58 were found in RG1 vaccinated animals with titers up to 10,000. Due to the limited number of animals (n = 3) we refrained from showing geometric mean titers (GMT) of HPV type specific (cross-)neutralization for all rabbits of a single vaccination group. Nevertheless, trends in the RG1 vaccine’s potential to induce cross-protection, dependent on RG1-VLP doses, are illustrated by GMT of L2-specific cross-neutralizing antibodies against HPV18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, 26, and 70 for each individual rabbit. Overall GMT of cross-neutralization against hrHPV18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, 26, 70 for individual animals in “RG1–25” ([656]/[94]/[538]) and “RG1–125” ([200]/[1788]/[1531]) inclined to be higher than in “RG1–1’’([6]/[438]/[0]), “RG1–5”([300]/[88]/[6]), or “RG1–5 (2x)” ([50]/[19]/[13]), demonstrating advantageous cross-neutralization in animals that received higher doses of RG1-VLP. Cross-neutralizing antibodies for HPV31, 33, and 45 were detected in Cervarix vaccinated animals, but not for HPV52, 58, 26 and 70 when least diluted (1:50).

To examine the potential of a bivalent vaccine formulation, RG1-VLP (5 µg) were combined with 18L1-VLP (5 µg) (and 125 µg alum/12,5µg MPL adjuvant), similar to 16L1-VLP + 18L1-VLP in Cervarix or 4vGardasil. In two independent experiments, mice were immunized twice in groups of n = 5 on days 0 and 21 (“RG1 + 18L1 ×2”) or day 0 only (“RG1 + 18L1 ×1”) (Table 2). For comparison, groups of mice were immunized with a 1/4 dose of Cervarix (“1/4 Cervarix x2”, = 16L1-VLP 5 µg + 18L1-VLP 5 µg), a 1/4 dose of 4vGardasil (“1/4 Gardasil x2”, = 16L1-VLP 10 µg + 18L1-VLP 5 µg), or 125 µg alum/12,5mg MPL adjuvant only (“adjuvant control”) on days 0 and 21. Antisera were drawn two weeks later. Due to the limited blood volume collected from individual animals, equivalent volumes of 5 mouse sera per group were pooled and tested for (neutralizing) antibodies in ELISA and PBNA. For ELISA mice sera were serially diluted 10-fold starting at 1:100. PBNA were performed as indicated for rabbit sera, using dilutions of 1:50, 1:100, and consecutive serial 10-fold dilutions. Titers are shown for two independent vaccination experiments. Evaluation of HPV16 antibodies by VLP-ELISA and PBNA showed comparable results when using two immunizations with RG1-VLP, Cervarix or 4vGardasil with titers of 10,000/10,000; 10,000/100,000; 10,000/10,000 (ELISA), and 10,000/10,000; 10,000/10,000; 10,000/1000 (PBNA) respectively. In comparison, HPV18 antibody titers were 1000/100; 1000/1000; 100/1000 by HPV18VLP ELISA. Lower neutralizing titers against HPV18 were observed in PBNA for “RG1 + 18L1 ×2” group (100/1000) than in “1/4 Cervarix x2” (100,000/10,000) and “1/4 Gardasil x2” (10,000/10,000) groups, which was attributed to partial degradation of the 18L1-VLP vaccine component by long-term storage and repeated freeze/thaw cycles, although immune interference in the combined vaccine formulation cannot be completely ruled out. Distinct L2-specific antibodies were found in sera of mice vaccinated either twice (1000/1000) or singly (1000/1000) with RG1 + 18L1, as measured by RG1-peptide ELISA, but not in Cervarix or Gardasil immunized or adjuvant control animals. Additionally, mice immunized with RG1-VLP + HPV18L1-VLP only once (“RG1 + 18L1 ×1”), showed similar or 1 log lower antibodies against HPV16L1-VLP, HPV18L1-VLP in ELISA, or HPV16- and HPV18-neutralization titers in PBNA than mice immunized twice with RG1-VLP + HPV18L1-VLP (“RG1 + 18L1 ×2”) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Combined RG1-VLP + 18L1-VLP vaccination compared to Cervarix and 4vGardasil. In two independent experiments, BALB/c mice in groups of n = 5 animals were immunized subcutaneously with 5 µg of RG1-VLP plus 5 µg of HPV18L1-VLP, absorbed to 125 µg aluminium hydroxide plus 12,5 µg MPL (alum/MPL) adjuvants, on day 0 (“RG1 + 18L1 (1x)“) or days 0 and 21 (“RG1 + 18L1 (2x)“); or with a 1/4 dose of Cervarix or 4vGardasil (“1/4 Cervarix x2“, “1/4 Gardasil x2“), or with indicated doses of alum/MPL adjuvant only on days 0 and 21. Sera were drawn on day 38 (experiment 1) or 52 (experiment 2), and pooled for groups of 5 animals. Sera were serially diluted 5 fold and tested in triplicates in HPV16L1-VLP, HPV18L1-VLP and RG1-peptide ELISA. Titers of pooled sera (n = 5) from two independent experiments are shown. Further, sera were diluted 1:50, and 1:100 – 1:1.000,000 in 10-fold serial dilution steps and analyzed in HPV16 and HPV18 neutralization assays (PBNA). Neutralization titers are shown for two independent vaccination experiments. RG1, RG1-VLP; 16, 16L1-VLP; 18, 18L1-VLP; alum, aluminium hydroxide; MPL, monophosphoryl Lipid A; RG1pep, RG1 synthetic peptide.

| Number of immunizations | 1 x | 2 x | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group n = 5 | “RG1 + 18L1 x1” | “RG1 + 18L1 x2” | “ 1/4 Cervarix x2” | “1/4 Gardasil x2” | adjuvant control | |

| VLP | RG1 + 18 | RG1 + 18 | 16 + 18 | 16 + 18 | – | |

| µg /dose | 5 5 | 5 5 | 5 5 | 10 5 | – | |

| alum (µg) | 125 | 125 | 125 | 56,25 | 125 | |

| MPL (µg) | 12,5 | 12,5 | 12,5 | 0 | 12,5 | |

| BALBc mouse vaccination (d) | 0 | 0, 21 | 0, 21 | 0, 21 | 0, 21 | |

| ELISA | HPV16L1-VLP | 10,000/1000 | 10,000/10,000 | 10,000/100,000 | 10,000/10,000 | 0/0 |

| HPV18L1-VLP | 100/100 | 1000/100 | 1000/1000 | 100/1000 | 0/0 | |

| RG1pep | 1000/1000 | 1000/1000 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 | |

| PBNA | HPV16 | 1000/1000 | 10,000/10,000 | 10,000/10,000 | 10,000/1000 | 0/0 |

| HPV18 | 100/1000 | 100/1000 | 100,000/10,000 | 10,000/10,000 | 0 | |

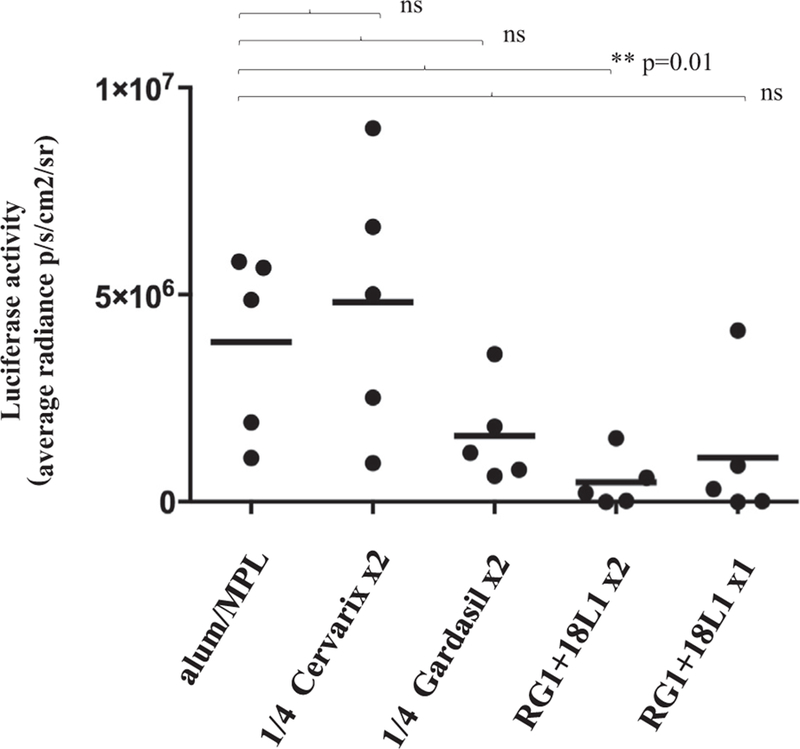

We next determined the potential of 5 µg RG1-VLP vaccination (s) to cross-protect against a hrHPV type beyond those targeted by Cervarix and 4vGardasil. Mice (groups of n = 5) were immunized twice in 3 weeks intervals as described above, challenged with heterologous hrHPV58 pseudovirions (PsV; containing a Luciferase reporter gene) 14 days after the second immunization and infection was detected by chemiluminescence 3 days later. Mice vaccinated with RG1-VLP + 18L1-VLP twice “RG1 + 18L1 ×2” were significantly (p = 0.01) cross-protected against vaginal challenge with heterologous hrHPV58, whereas two vaccinations with Cervarix or 4vGardasil, or a single vaccination “RG1 + 18L1 ×1” did not provide significant cross-protection (Fig. 1). Non-significant reduction of hrHPV58 PsV infection was found following experimental vaccinations with “RG1 + 18L1 ×1” or “Gardasil x2” (4vGardasil) but not “Cervarix x2”. Low-titer cross-neutralizing antibodies against the most closely related hrHPV of genus alpha HPV16 (species 9; HPV31) and HPV18 (species 7; HPV45) following bivalent or quadrivalent vaccination has been described previously [14]. Quantitative and qualitative differences in the crossneutralization potential of the two licensed vaccines may be attributed to the use of different adjuvants and/or the impact of different protein expression systems in vaccine manufacturing.

Fig. 1.

Two RG1-VLP + 18L1-VLP Immunizations Cross-Protect Mice from HPV58 Experimental Challenge. Mice in groups of n = 5 were immunized once on day 0 with RG1-VLP + HPV18L1-VLP (“RG1 + 18L1 ×1’’), or twice on days 0 and 21 (“RG1 + 18L1 ×2’’), Cervarix (“1/4 Cervarix x2”), 4vGardasil (“1/4 Gardasil x2”), or 125/12,5 mg alum/MPL adjuvant only. 14 days later mice were intravaginally challenged with HPV58 PsV encoding for luciferase. Luciferase activity was quantitated by bioluminescence imaging (Y axis: average radiance; p/s/cm2/sr) and is given with the respective background luminescence (unvaccinated mice challenged with carboxymethylcellulose only) subtracted from all data points. The p-value (0.01) comparing group “alum/MPL” and “RG1 + 18L1 ×2” is indicated by **p. ns, not significant.

Finally, we sought to obtain correlates of protection against HPV58 challenge in vivo and PBNA titers in vitro. By PBNA (data not shown), immune sera showed HPV58 neutralization titers of 50 in 3/5 mice in “RG1 + 18L1 ×2” group, 0/5 mice in “RG1 + 18L1 ×1” group, 0/5 mice in “1/4 Gardasil” group, and 0/3 mice (2 sera were not available for retesting) in “1/4 Cervarix” group, suggesting that HPV58 neutralizing activity in sera correlates with protection against experimental HPV58 challenge in vivo.

3. Discussion

The experimental RG1-VLP vaccine is based on HPV16L1-VLP (used in current vaccines) modified by the insertion of a single cross-neutralization epitope (RG1) of minor capsid protein L2 into the DE surface loop of L1. Similar to licensed Cervarix, RG1-VLP is recombinantly produced in insect cells. In addition to the ultrastructural resemblance of the RG1 morphology to wild-type HPV16L1-VLP by electron microscopy [10], RG1-VLP is immunologically similar to wild-type HPV16L1-VLP. Characterization of RG1-VLP by monoclonal antibodies to conformational sites of HPV16L1 shows a similar yet not identical profile indicating preservation of important neutralization epitopes (our unpublished data). Importantly, previous studies have shown induction of high-titer HPV16 neutralizing antibody responses by RG1-VLP vaccination, comparable to HPV16L1wt-VLP vaccination. A head-to-head comparison of RG1-VLP and 16L1-VLP in commercial HPV vaccines is essential to prove non-inferiority of RG1-VLP to protect against HPV16 infection. We have used experimental vaccine formulations containing aluminium hydroxide/MPL adjuvant in antigen/adjuvant doses equivalent to Cervarix. Immunizations with 5 µg RG1-VLP or 5 µg 16L1-VLP (the latter contained in Cervarix and Gardasil) of rabbits (3× immunization protocol) or mice (2x immunization protocol) induced similar titers of HPV16 capsid antibodies by ELISA, and similar (mice) or 1 log lower titers (rabbits) of neutralizing HPV16 antibodies by PBNA. Whether generic differences in L1 epitope presentation in RG1-VLP and HPV16L1 result in lower HPV16 neutralizing antibodies in RG1-VLP compared to Cervarix vaccinated rabbits cannot be completely ruled out. However, similar levels of HPV16L1-specific antibodies in ELISA and equivalent HPV16 neutralization in sera of RG1-VLP and Cervarix vaccinated mice render it more likely that lower HPV16 neutralization titers in RG1-VLP vaccinated rabbits are due to higher portions of degraded protein in preclinically produced RG1-VLP than in Cervarix vaccine. We conclude, that RG1-VLP are non-inferior to 16L1-VLP in generating a potent neutralizing antibody response against HPV16 in pre-clinical immunization protocols.

HPVL1-VLP are potent inductors of antibodies, raised against densely-spaced conformational capsid surface epitopes. These antibodies neutralize infection by impeding viral association with the basal membrane or binding to the basal keratinocytes, respectively. In contrast, L2 (poly)peptide vaccinations induce antibodies that do not prevent basal membrane binding of the virus in the first place but depend on subsequent conformational changes of the capsid to disable viral infection of the basal keratinocytes [15]. These complex mechanisms can only be inadequately reproduced in in vitro assays. Additionally, recent findings suggest a role for L2 antibody in protection via opsonization that is not detected by current in vitro assays [16]. Although antibody titers induced to L2 are several logs lower compared to antibodies to L1, in vivo protection against homologous and heterologous PV induced by immunizations with PV L2 (poly)peptides has extensively been reported before. RG1-VLP immune sera have efficiently (cross-) protected mice against experimental infection with all relevant hrHPV [11]. The desirable titer of neutralizing antibodies against L2 (or L1) required to mediate sustainable protection from infection at a given timepoint is unknown. Previously published data have shown cross-protection in vivo over 1 year provided by vaccination with 50 µg RG1-VLP, even in the absence of detectable serum neutralization in vitro, indicating the low sensitivity of current in vitro assays to detect L2-mediated (cross-)neutralization [11]. Thus in vivo mouse or rabbit challenge models (using HPV PsV or quasi-virions, respectively) are regarded the gold standard to determine HPV vaccine efficacy [13]. Herein, vaccinations with RG1-VLP have induced robust anti-L2 (RG1) serum titers by RG1 peptide ELISA in rabbits and mice (Tables 1 and 2), and broadly cross-neutralizing activity to hrHPV18/31/33/45/52/58/26/70 was determined in rabbit sera (Table 1). Although inadequate amount of antisera obtained prevented further determination of crossneutralization induced in mice by RG1-VLP plus HPV18L1 VLP immunization, we infer from robust anti-L2 (RG1) titers (Table 2), that in addition to L1-specific neutralizing antibody response against HPV16 and HPV18, broad cross-neutralization of heterologous HPV types via antibodies recognizing the RG1 motif of L2 was likely induced.

To the best of our knowledge dose finding studies with chimeric L1-L2 vaccines have not been published. Vaccinating thrice with 25 µg (or 125 µg) RG1-VLP in rabbits induced robust and hightiter cross-neutralizing antibodies against hrHPV18/31/33/45/52/58/26/70, raised by the single epitope RG1 in the context of a chimeric VLP immunization with an estimated MW ratio of ~1:25 (RG1:16L1 protein). The 9vL1-VLP vaccine includes relatively high antigen doses (270 µg protein per dose) presenting immunologically favorable L1-VLP amounts of each L1-VLP type included. The exhaustive spectrum of crossneutralization induced by RG1-VLP immunization exceeds that known for licensed human L1-VLP vaccines (Table 1). A comparison of the spectrum of protection provided by conserved L2 motifs (RG1-VLP), or type-specific conformational L1 epitopes (multivalent L1-VLP) may therefore be performed using comparable amounts of antigen. Here we describe robust cross-neutralization of types included in 9vGardasil and of additional hrHPV achieved by vaccination with 25 mg RG1-VLP. The use of higher overall amounts of RG1-VLP did induce a significantly higher HPV16-specific response, but not cross-neutralization of other HPV types. The negligible differences in cross-neutralizing antibody titers raised with 25 µg or 125 µg RG1-VLP injections appears to indicate a dose-dependent saturation of RG1 epitopes within the chimeric HPV16 capsid exposed to the immune system. Human doseranging studies with monovalent L1-VLP, and studies comparing 4v to 9vL1-VLP vaccinations have shown rates of local side effects increase with total amount of protein injected [17,18]. However no local or systemic side effects with higher amounts of RG1-VLP were observed in our preclinical studies (our personal observation/personal communication T. Twardzik, Charles River).

Approval for a two dose protocol for adolescents <15 years substantially improves cost efficiency of licensed HPV vaccination programs [19,20]. Next generation vaccines will have to measure up to this immunization regime to gain wider acceptance. Although antibody titers (both to L1 and L2) were lower in rabbits immunized twice with RG1-VLP compared to those vaccinated three times, two (but not single) immunizations with a combined formulation of RG1-VLP + 18L1-VLP were sufficient to protect mice against challenge with non-related hrHPV58. Whether dosage optimization can provide robust vaccine efficacy even in a single dose immunization protocol needs further study. We also tested RG1-VLP coformulated with HPV18L1-VLP to exclude immune interference in vaccinated mice. As expected, both HPV16- and RG1-specific antibody responses (ELISA) against RG1-VLP were maintained. The observed lower neutralizing antibody response against HPV18 by PBNA, but unimpaired overall antibody titers in ELISA when compared with Cervarix or 4vGardasil are most likely due to subtle degradation of HPV18L1-VLP through long-term storage. These results may also support combined vaccine formulations of divergent RG1-VLP based on additional HPV L1 VLP types and/or RG1-homologous peptides to target different spectra of HPV serotypes in a multivalent RG1-VLP vaccine setting. Such strategies may allow further expansion of HPV vaccine protection to include cutaneous HPV with the aim to develop a comprehensive pan-HPV vaccine [21].

4. Materials & methods

4.1. RG1-VLP

Generation of chimeric RG1-VLP by genetic insertion of HPV16 L2 peptide aa 17–36 (RG1) into the DE-surface loop of HPV16L1, protein expression in Sf9 insect cells and purification has been described [10].

4.2. Immunization

NZW rabbits were immunized subcutaneously (Charles River Laboratories, Germany) with 1 µg, 5 µg, 25 µg or 125 µg of RG1-VLP adsorbed to 125 µg aluminiumhydroxide (Alhydrogel 2%, Invivogen) and 12,5 µg of MPL (PHAD, Avanti Polar Lipids) adjuvant, or 125 µl (1/4 dose) of Cervarix on days 0, 60, 120, or 5 µg of RG1-VLP similarly adjuvanted on day 0 and 120. Sera were drawn 14 days after the final boost.

Female BALB/c mice (groups of n = 5) were immunized subcutaneously with 5 µg of RG1-VLP plus 5 mg of HPV18L1-VLP adjuvanted with 125 mg aluminium hydroxide and 12,5 µg MPL in saline on day 0, or days 0 and 21; or with 125 µl (1/4 dose) of Cervarix or 4vGardasil on days 0 and 21. Following vaginal challenge cardiac puncture and neck dissection was performed on anesthesized animals.

4.3. Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

Standard procedures such as L1-VLP ELISA using HPV16L1-VLP and HPV18L1-VLP as antigen, and L2-peptide ELISA using the biotinylated peptide HPV16L2 aa 17–36 (QLYKTCKQAGTCPPDIIPK; JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany) has been described [10,11]. Rabbit sera were used in 5-fold serial dilutions starting at 1:100, and mice sera were used in 10-fold serial dilutions starting at 1:100.

4.4. Murine vaginal challenge

The intravaginal PsV challenge model was performed according to Roberts et al [11,22]. In brief, mice (groups of n = 5) were pretreated with 3 mg of progesterone to synchronize the oestrus. Following cytobrush-induced microtrauma, mice were intravaginally challenged with luciferase-encoding HPV58 PsV in 3% carboxymethylcellulose. After 3 days, 20 µl of luciferin was applied into the vagina, and infection was analyzed by bioluminescence imaging (IVIS, Caliper Life Science). Data are given with background signal subtracted (mice challenged with carboxymethylcellulose) only.

4.5. Pseudovirion-based neutralization assays (PBNA)

Production of PsV and hrHPV16 and hrHPV18 neutralization assays were performed with minor modifications as previously described (http://home.ccr.cancer.gov/lco/protocols.asp) and neutralization was detected colorimetrically [12]. Additionally, L2 PBNA with hrHPV types HPV31, 33, 45, 52, 58, 26 and 70 were performed according to Day et al [13]. In brief, 2*106 HaCaT cells were plated onto 96-well plates for 24 h at 37 °C, washed with PBS and lysed using PBS + 0.5% Triton X-100 + 20 mM NH4OH for 5 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, the remaining extracellular matrix was gently washed with PBS (3x), PsV in CHODfurin conditioned medium containing heparin (Gilvasan Pharma) were added, incubated at 37 °C overnight and washed with PBS. Following addition of serial dilutions of antiserum, 8*103 PGSA-745 cells were added and the mixture incubated for two days at 37 °C. For luciferase encoding PsV, assays were evaluated using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega #E1501) and the Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega #E153A) according to company’s instructions in 96-well opaque Optiplates (Nunc). Luciferase activity was measured using either a 1420 Victor3 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer) or Fluoroskan Ascent FL (Thermo Scientific) plate reader, with 10 s per well reading time.

4.6. Animal welfare

Animal studies have been approved (BMWF-66.009/0173–1I/3b/2011) and animal care was in accordance with the guidelines of the Austrian Federal Ministry for Science and Research.

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported in part by US Public Health Service grants (grants.nih.gov) from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under awards numbered R01CA118790, P50CA098252, and R01CA233486 to RBSR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Further support was provided by EU-funded InfectEra: HPV-MOTIVA to RK.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

Under a license agreement between PathoVax LLC, Medical University of Vienna and Johns Hopkins University, CS, RK and RBSR are entitled to distributions of payments associated with an invention relating to RG1-VLP. CS, RK and RBSR also own equity in Patho-Vax LLC and RK and RBSR are members of its scientific advisory board. These arrangements have been reviewed and approved by Medical University of Vienna and Johns Hopkins University in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

References

- [1].Formana D, de Martel C, Lacey CJ, Soerjomatarama I, Lortet-Tieulent J, Bruni L, et al. Global burden of human papillomavirus and related diseases. Vaccine 2012;30:F12–23. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kirnbauer R, Booy F, Cheng N, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Papillomavirus Li major capsid protein self-assembles into virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic. Med Sci 1992;89:12180–4. 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rose RC, Bonnez W, Reichman RC, Garcea RL. Expression of human papillomavirus type 11 L1 protein in insect cells: in vivo and in vitro assembly of viruslike particles. J Virol 1993;67:1936–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hagensee ME, Yaegashi N, Galloway DA. Self-assembly of human papillomavirus type 1 capsids by expression of the L1 protein alone or by coexpression of the L1 and L2 capsid proteins. J Virol 1993;67:315–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Einstein MH, Levin MJ, Chatterjee A, Chakhtoura N, Takacs P, Catteau G, et al. Comparative humoral and cellular immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine and HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine in healthy women aged 18–45 years: follow-up through Month 48 in a Phase III randomized study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014;10:3455–65. 10.4161/hv.36117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen O-E, Bouchard C, Mao C, Mehlsen J, et al. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med 2015;372:711–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1405044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Schellenbacher C, Roden RBS, Kirnbauer R. Developments in L2-based human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. Virus Res 2017;231 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [8].Chandrachud LM, Grindlay GJ, McGarvie GM, O’Neil BW, Wagner ER, Jarrett WFH, et al. Vaccination of cattle with the N-terminus of L2 is necessary and sufficient for preventing infection by bovine papillomavirus-4. Virology 1995;211:204–8. 10.1006/viro.1995.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gambhira R, Karanam B, Jagu S, Roberts JN, Buck CB, Bossis I, et al. A protective and broadly cross-neutralizing epitope of human papillomavirus L2. J Virol 2007;81:13927–31. 10.1128/JVI.00936-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schellenbacher C, Roden R, Kirnbauer R. Chimeric L1–L2 virus-like particles as potential broad-spectrum human papillomavirus vaccines. J Virol 2009;83:10085–95. 10.1128/JVI.01088-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schellenbacher C, Kwak K, Fink D, Shafti-Keramat S, Huber B, Jindra C, et al. Efficacy of RG1-VLP vaccination against infections with genital and cutaneous human papillomaviruses. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:2706–13. 10.1038/jid.2013.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Buck CB, Pastrana DV, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Efficient intracellular assembly of papillomaviral vectors. J Virol 2004;78:751–7. 10.1128/JVI.78.2.751-757.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Day PM, Pang YYS, Kines RC, Thompson CD, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. A human papillomavirus (HPV) in vitro neutralization assay that recapitulates the in vitro process of infection provides a sensitive measure of HPV L2 infection-inhibiting antibodies. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012;19:1075–82. 10.1128/CVI.00139-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Einstein MH, Baron M, Levin MJ, Chatterjee A, Fox B, Scholar S, et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 vaccine and the HPV-6/11/16/18 vaccine for oncogenic non-vaccine types HPV-31 and HPV-45 in healthy women aged 18–45 years. Human Vaccin 2011;12:1359–73. 10.4161/hv.7.12.18282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Day PM, Kines RC, Thompson CD, Jagu S, Roden RB, Lowy DR, et al. In vivo mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against HPV infection. Cell Host Microbe 2010;8:260–70. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang JW, Wu WH, Huang TC, Wong M, Kwak K, Ozato K, et al. Roles of Fc domain and exudation in L2 antibody-mediated protection against human papillomavirus. J Virol 2018;92(15). 10.1128/JVI.00572-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Harro CD, Pang YYS, Roden RBS, Hildesheim A, Wang Z, Reynolds MJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity trial in adult volunteers of a human papillomavirus 16 L1 virus-like particle vaccine. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001. 10.1093/jnci/93.4.284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [18].Huh WK, Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, de Andrade RP, Ault KA, et al. Final efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety analyses of a nine-valent human papillomavirus vaccine in women aged 16–26 years: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2017. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31821-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [19].Schwarz TF, Leo O. Immune response to human papillomavirus after prophylactic vaccination with AS04-adjuvanted HPV-16/18 vaccine: Improving upon nature. Gynecol Oncol 2008. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [20].Leung TF, Liu APY, Lim FS, Thollot F, Oh HML, Lee BW, et al. Comparative immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine and 4vHPV vaccine administered according to two- or three-dose schedules in girls aged 9–14 years: Results to month 36 from a randomized trial. Vaccine 2018;36:98–106. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Huber B, Schellenbacher C, Shafti-Keramat S, Jindra C, Christensen N, Kirnbauer R. Chimeric L2-Based Virus-Like Particle (VLP) Vaccines Targeting Cutaneous Human Papillomaviruses (HPV). PLoS One 2017;12:e0169533 10.1371/journal.pone.0169533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Roberts JN, Buck CB, Thompson CD, Kines R, Bernardo M, Choyke PL, et al. Genital transmission of HPV in a mouse model is potentiated by nonoxynol-9 and inhibited by carrageenan. Nat Med 2007. 10.1038/nm1598. [DOI] [PubMed]