Abstract

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), which accounts for the majority of kidney cancer, is known to accumulate excess cholesterol. However, the mechanism and functional significance of the lipid accumulation for development of the cancer remains obscure. In this study, we analyzed 42 primary ccRCC samples, and determined that cholesterol levels of ~ 70% of the tumors were at least two-fold higher than that of benign kidney tissues. Compared to tumors without cholesterol accumulation, those containing excess cholesterol expressed higher levels of scavenger receptor BI (SR-B1), a receptor for uptake of HDL-associated cholesterol, but not genes involved in cholesterol synthesis and uptake of LDL-associated cholesterol. To further determine the roles of sterol accumulation for cancer development, we implanted ccRCC from patients into mouse kidneys using a mouse ccRCC xenograft model. Feeding mice with probucol, a compound lowing HDL-cholesterol, markedly reduced levels of cholesterol in tumors containing excess cholesterol. This treatment, however, did not affect growth of these tumors. Our study suggests that cholesterol overaccumulation in ccRCC is the consequence of increased uptake of HDL-cholesterol as a result of SR-B1 overexpression, but the lipid accumulation by itself may not play a significant role in progression of the cancer.

Keywords: Cholesterol, Cancer, Scavenger Receptors, Kidney, Lipidomics, Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

1. Introduction

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC)1 accounts for the majority of kidney cancers (1). The “clear cell” appearance in histology analysis of the cancer cells is believed to be caused by their accumulation of lipid, particularly cholesterol (2–4). In mammalian cells, cholesterol can be produced through de novo synthesis and uptake of low density lipoprotein (LDL) or high density lipoprotein (HDL)-associated cholesterol from circulation (5–7). It remains unclear how ccRCC acquires excess cholesterol. The functional significance of the sterol accumulation for development of the cancer has also not been determined.

Nearly all ccRCC tumor cells contain mutations inactivating Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome protein (VHL), an E3 ubiquitin ligase required for degradation of the α subunits of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFαs) (1). Under normal conditions, HIFαs are ubiquitinated by VHF and rapidly degraded by proteasomes (8). Hypoxia stabilizes HIFαs (8), allowing them to activate transcription of genes coping with the stress condition (9). Inactivation of VHF enables accumulation of HIFαs even under normal conditions. The aberrant activation of HIFαs, particularly HIF2α, is believed to be the major mechanism to trigger development of ccRCC (1, 10). However, the roles of cholesterol accumulation for activation of the HIF pathway have yet to be identified.

In the current study, we demonstrate that ccRCC cells accumulate cholesterol through increased uptake of HDF-cholesterol by overexpressing scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1), the receptor for HDF (7, 11). While increased expression of SR-B1 may facilitate ccRCC development, cholesterol accumulation does not appear to play an important role in progression of the cancer. Thus, cholesterol accumulation may be a consequence but not the cause for development of the cancer.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

We obtained anti-actin and probucol from Sigma-Aldrich; DAPI, BODIPY 493/503, and Infinity™ Cholesterol reagent from Thermo Scientific; and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgGs from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Anti-human SR-B1 was a gift from Dr. Helen Hobbs. De-identified ccRCC tumors and benign tissues from the same patients were obtained from the Tissue Management Shared Resource, the Simmons Cancer Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, which provides Institutional Review Board-approved centralized tissue procurement service.

2.2. Mice

4-6 week old male NOD/SCID mice were used for studies under Animal Protocol Number # 2015-101120 approved by University of Texas Southwestern IACUC. All mice were purchased from UTSW breeding core. Mice were housed in sterile barrier facility and fed an irradiated 16% protein chow diet (Teklad, 2916) or that supplemented with 0.5% (wt/wt) probucol.

2.3. Establishment of xenograft ccRCC in mice

Xenograft tumors were established by implanting ccRCC tumors into mouse kidneys within two hours of removal from patients, and maintained by continued passage in mice exactly as previously described (12).

2.4. Lipid measurement

To measure cholesterol and other sterols, samples were extracted and analyzed as previously reported (13) with the following modifications: Kidney tissue samples (~100mg) were placed in 0.5M KOH in methanol for one hour at 80°C. Lipids were then extracted twice with a Bligh/Dyer lipid extraction (methanol/dichloromethane/aqueous 1:1:1) and the lipid extract was diluted to a uniform concentration. An extract volume equivalent to 250 μg kidney tissue was transferred to a GC vial, dried under a nitrogen with gentle heat, and reconstituted in 1.5ml 90% methanol with 415 ng of d7-cholesterol as an internal standard.

Cholesteryl esters and triglycerides were measured by Cholesterol/Cholesteryl Ester Assay Kit and Triglyceride Assay Kit (Abcam), respectively, according to manufacturer’s instruction.

2.5. Real-time QPCR

Total RNA extracted from tissues homogenized by RNA STAT-60™ (Amsbio) and 2.8-mm ceramic bead kit (Omni international) was subjected to real-time QPCR as previously described (14). Primers used for quantification of the indicated genes are listed in Table 1. The relative amounts of RNAs were calculated through the comparative cycle threshold method by using human 36B4 mRNA as the invariant control. Relative mRNA expression was normalized by level of the genes expressed in HEK293 cells, which is set at 1.

Table 1.

Forward (F) and reversed (R) primers used for quantification of indicated human mRNA through RT-QPCR

| mRNA | Primer | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| HMGCR | F | CAAGGAGCATGCAAAGATAATCC |

| R | GCCATTACGGTCCCACACA | |

| Insig-1 | F | CCCAGATTTCCTCTATATTCGTTCTT |

| R | CACCCATAGCTAACTGTCGTCCTA | |

| SQLE | F | GAGATGGAAGAAAGGTGACAGTCA |

| R | CACCCGGCTGCAGGAAT | |

| LDLR | F | GGCTGCGTTAATGTGACACTCT |

| R | CTCTAGCCATGTTGCAGACTTTGT | |

| SR-B1 | F | CTCATCAAGCAGCAGGTCCTT |

| R | TAGGGATCTCCTTCCACATGTTG | |

| ABCA1 | F | CCAGGCCAGTACGGAATTC |

| R | CCTCGCCAAACCAGTAGGA | |

| ACAT1 | F | CCTGAGGAAGATGAAGACCAGAGA |

| R | ACTGTTTTATGTCAATTCGACCATTACT |

2.6. Bisulfite Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from xenograft tumors using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen), and subject to bisulfite conversion (C→U) using the EX DNA Methylation Lightning Kit (Zymo) following the protocols provided by the manufacturers. Converted DNA was amplified by PCR using ZymoTaq Premix (Zymmo) with the forward primer 5’-ATTGTAGTTTYGGTGTGGTGGTTTTTTATGTAGG-3’ and the reverse primer 5’-AAAAAATAACCRACTCAATCCATAAAATAATATC-3’. Amplified fragments were ligated into a plasmid using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) followed by sequencing analysis.

2.7. Immunoblot

Tissue samples lysed in buffer A (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, l% NP-40, 5mM EDTA) containing cOmplete Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Roche) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with anti-SR-Bl (8 μg/ml) and anti-actin (1:10,000 dilution). Bound antibodies were visualized with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (0.2 μg/ml) using SuperSignal ECL-HRP substrate system (Pierce). Immunoblot image was analyzed by Li-Cor Odyssey imaging system and Image studio software.

2.8. Lipid droplet staining

Flash-frozen tumors were mounted in Cryomold using the O.C.T Compund (Tissue-Tek), slowly frozen in crushed dry ice, and sliced through Leica CM 1900 with the temperature kept at −20°C. Cryosection was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 2 μg/ml BODIPY 493/503 and 3 μg/ml DAPI, and visualized through a Zeiss LSM880 Airyscan microscope to obtain confocal fluorescent image. Images were analyzed by Image J software.

2.9. Lipoprotein Analysis

Lipoprotein in mouse serum was separated through FPLC as previously described (15). Cholesterol in each fraction was quantified through Infinity™ total cholesterol reagents according to the instruction of the manufacturer.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Paired or unpaired, two-tailed student t-tests were performed as described in the figure legend to determine the statistical significance.

3. Results

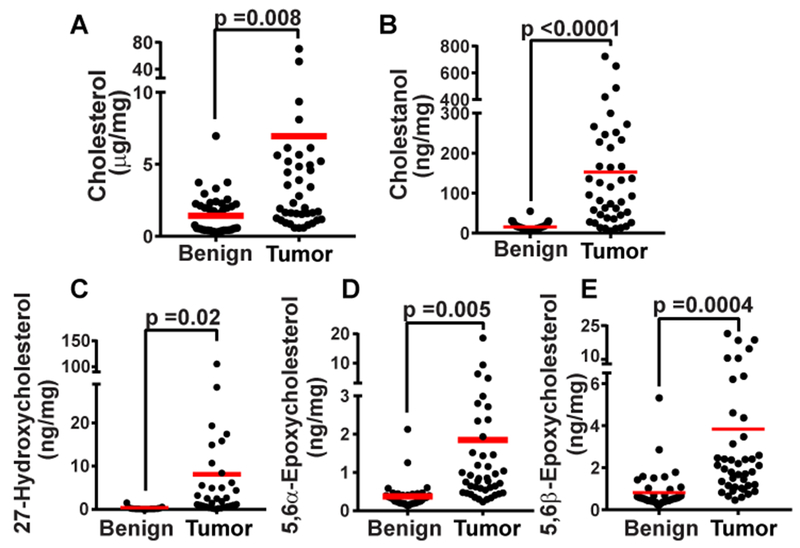

Using lipidomic analysis, we and other reported that the lipid accumulated at the highest level in ccRCC was cholesterol (2, 3). We thus performed a targeted analysis to measure cholesterol and other sterols with mass spectroscopy (Table S1). The cholesterol levels in two-thirds of the 42 ccRCC tumors we analyzed were at least two-fold higher than that in the benign kidney tissues taken from the same patient (Fig. 1A). On average, the amount of cholesterol in ccRCC was ~5-fold higher than that in the benign controls (Fig. 1A). In addition to cholesterol, levels of sterols derived from cholesterol such as 27-hydroxycholesterol, cholestanol, 5,6α-epoxy cholesterol, and 5.6β-epoxy cholesterol were also significantly elevated in the tumors (Figs. 1B–E).

Figure 1.

Accumulation of sterols in ccRCC. Sterols in ccRCC and corresponding benign tissue samples taken from patients were measured through mass spectroscopy. Statistical analysis was performed by paired two-tailed t-tests (n= 42). Only the sterols the levels of which in tumors were significantly higher than that in benign tissues (p < 0.05) were shown in the figure.

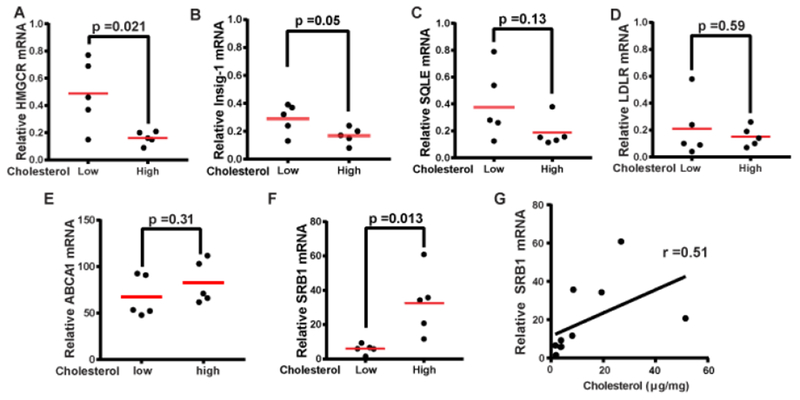

To investigate the mechanism through which ccRCC acquires excess cholesterol, we compared expression of genes involved in cholesterol synthesis and uptake between tumors containing higher levels of cholesterol (more than 4-fold higher than the average level of benign tissues) and those without the apparent lipid accumulation (less than 2-fold higher than the average level of the benign tissues). This analysis revealed that expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), the rate-limiting enzyme involved in cholesterol synthesis (16), was actually inhibited in tumors containing higher levels of cholesterol (Fig. 2A). This observation suggests that cholesterol accumulation in ccRCC is unlikely caused by increased de novo synthesis. The decreased expression of HMGCR in the tumors with higher levels of cholesterol was likely caused by cholesterol-mediated feedback inhibition of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs), a family of transcription factors activating all genes involved in cholesterol synthesis including HMGCR (6, 17). Consistent with this idea, expression of Insig-1, a SREBP target required for sterol-mediated inhibition of SREBPs (18), was also inhibited in tumors containing higher levels of cholesterol (Fig. 2B). Expression of squalene epoxidase (SQLE), another enzyme involved in cholesterol synthesis activated by SREBPs (17), followed the same trend but the difference was less statistically significant (Fig. 2C). There was no significant difference in expression of LDL receptor, a protein responsible for uptake of LDL-cholesterol (5) (Fig. 2D), and ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily A Member 1 (ABCA1), a transporter exporting cholesterol out of cells (19) (Fig. 2E), between the two groups of the tumors. In contrast, expression of SR-B1, which mediates uptake of HDL-cholesterol, was markedly elevated in tumors containing higher levels of cholesterol (Fig. 2F). The amount of SR-B1 mRNA appeared to be positively correlated with the cholesterol content in the tumor cells (Fig. 2G)

Figure 2.

Expression of the cholesterol metabolic genes in ccRCC. (A-F) Expression of the indicated genes in primary ccRCC tumors containing high (more than 4-fold higher than the average level of benign tissues) or low levels of cholesterol (less than 2-fold higher than the average level of the benign tissues) was quantified by real-time QPCR, and normalized by level of the genes expressed in HEK293 cells, which is set at 1. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. (G) The relative amount of SR-B1 mRNA was plotted against the amount of cholesterol in the tumors and analyzed by Pearson analysis.

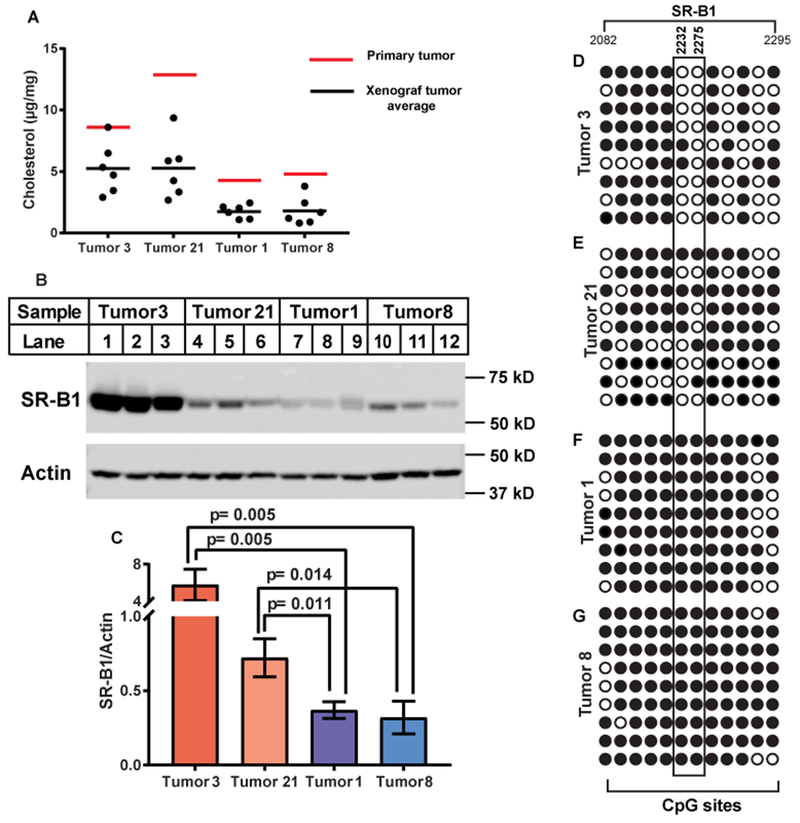

To further delineate the mechanism of cholesterol accumulation and its contribution to progression of ccRCC, we transplanted the tumors with higher levels of cholesterol (tumors 3 and 21) and those without the lipid accumulation (tumors 1 and 8) into mouse kidneys according to the protocol to establish xenograft ccRCC in mice (12, 20). Mass spectroscopy analysis revealed that these lines of xenograft tumors grown in mice maintained their difference in cholesterol accumulation, even though cholesterol levels in all the tumors grown in mice were lower than that in the primary tumors (Fig. 3A). Likewise, expression levels of SR-B1 were higher in xenograft tumors 3 and 21 derived from ccRCC with higher levels of cholesterol than tumors 1 and 8 derived from those without the lipid accumulation (Figs. 3B and C).

Figure 3.

Cholesterol accumulation in xenograft ccRCC tumors correlates with SR-B1 expression. (A) Indicated primary tumors were transplanted into kidneys of NOD/SCID mice as described in Experimental Procedures. Six (tumor 3) or eight weeks (the rest of the tumors) after the implantation, tumors were harvested for measurement of cholesterol content through mass spectroscopy. (B) Lysates of the xenograft tumors were analyzed by immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibody (C) Immunoblot signal of SR-B1 shown in B normalized by that of actin was quantified through Image-J software. Statistical analysis was performed by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. (D-G) Genomic DNA was extracted from indicated tumors for bisulfite sequencing as described in Materials and Methods. The closed and open circles denote methylated and unmethylated CpGs, respectively. The position is numbered according to SR-B1 transcript (GenBank accession No., NM_005505). Cytosines that showed the most significant difference in methylation between tumors expressing higher levels of SR-B1 and those expressing lower levels of the protein are boxed.

SR-B1 expression is known to be inhibited epigenetically by methylation of CpG islands throughout the gene (21). We thus measured the methylation status of the gene through bisulfate sequencing. We identified two cytosines in a CpG island located in exon 13 of SR-B1 that were much less frequently methylated in tumors 3 and 21, which expressed higher levels of SR-B1, than tumors 1 and 8, which expressed lower levels of the gene (Figs. 3D–G).

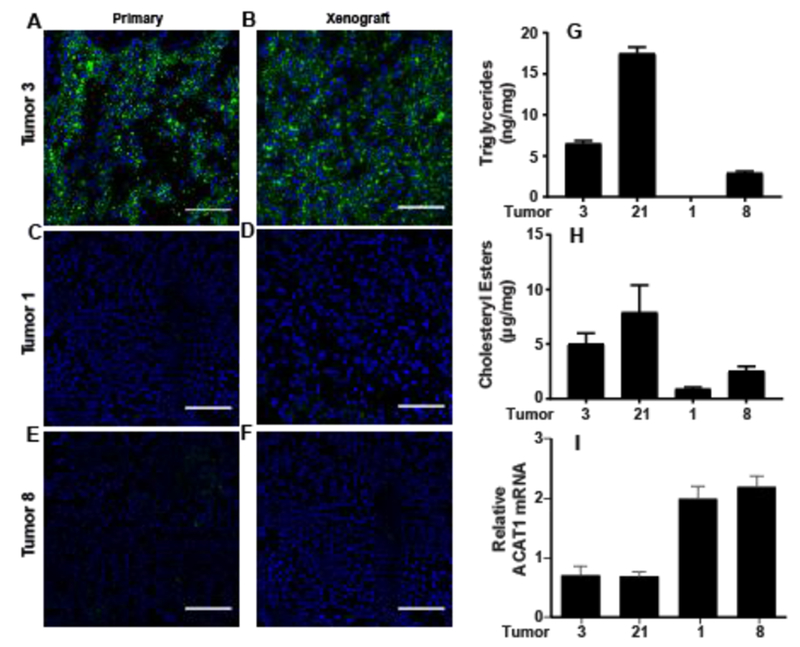

We also measured cholesterol accumulation by staining the tumor slides for lipid droplets where excess cholesterol is stored as cholesteryl esters (22). Both the primary and xenograft tumors originated from tumor 3, but not those from 1 or 8, were stained positively for lipid droplets (Figs. 4A–F). We did not have enough primary tumor tissues from tumor 21 to perform this analysis, but the xenograft tumors from this line were stained positively for lipid droplets (data not shown). Since xenograft tumors 3 and 21 contained much more cholesteryl esters than triglycerides (Figs. 4G and H), generation of lipid droplets in these tumors was most likely caused by accumulation of cholesteryl esters. Interestingly, expression of Acyl-coenzyme A cholesterol acyltransferase 1 (ACAT1), an enzyme catalyzing synthesis of cholesteryl esters (23), was actually lower in tumors with cholesterol accumulation (Fig. 4I), an observation suggesting that increased production of cholesteryl esters in these tumors was caused by increased availability of the substrate cholesterol but not elevated expression of the enzyme catalyzing the reaction. We did not detect measurable amounts of ACAT2, another ACAT enzyme expressed in mammals (23), and hormone-sensitive lipase, an enzyme hydrolyzing cholesteryl esters in adrenal cortex (24), in all four lines of xenograft ccRCC. Taken together, these results indicate that xenograft ccRCC tumors grown in mice inherited their trait in cholesterol accumulation from their parental primary tumors, thereby making this xenograft system a suitable model to study cholesterol accumulation in ccRCC.

Figure 4.

Cholesteryl ester accumulation in xenograft ccRCC tumors established in mice. (A-F) Cryosectioned primary (A, C and E) and the corresponding xenograft tumors (B, D and F) were stained by BODIPY 493/503 and DAPI for detection of lipid droplets and nucleus, respectively, through immunofluorescent microscopy. Scale bars = 100 μm. (G and H) The amount of triglycerides and cholesteryl esters in indicated tumors were measured and normalized against the weight of the tumors. The amount of triglycerides in tumor 1 was below the detection limit. (I) ACAT1 mRNA in indicated xenograft tumors was quantified by real-time QPCR, and normalized by level of the gene expressed in HEK293 cells, which is set at 1. (G-I) Results are reported as mean ± S.E. from three different xenografts of the indicated tumor line.

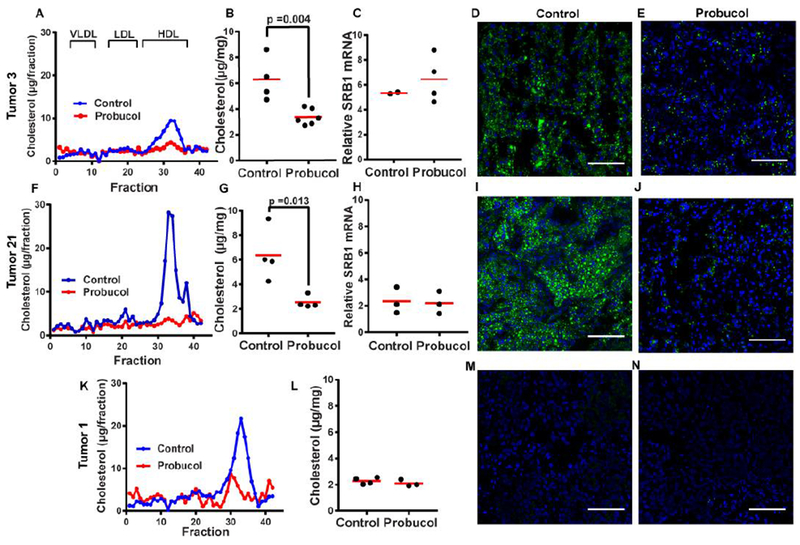

To determine whether enhanced uptake of HDL-cholesterol through elevated levels of SR-B1 is responsible for the ccRCC tumors to acquire excess cholesterol, we fed the mice bearing the xenograft tumors from tumors 3 and 21 that contain higher levels of cholesterol with probucol, a compound known to reduce HDL-cholesterol (25). Probucol treatment lowered the amount of HDL-cholesterol in serum of the mice implanted with tumors derived from tumor 3 (Fig. 5A). This treatment significantly lowered the levels of cholesterol in the xenograft tumors measured through mass spectroscopy (Fig. 5B) without affecting expression of SR-B1 in the tumor cells (Fig. 5C). The lipid-lowering effects of the probucol treatment were also demonstrated through lipid droplet staining (Figs 5D and E). Similar results were obtained from mice implanted with tumor 21 (Figs. 5F–J). As a control, we also fed the mice bearing tumor 1, which did not accumulate cholesterol, with probucol. While still lowing serum levels of HDL-cholesterol in these mice (Fig. 5K), probucol treatment did not further reduce cholesterol levels in these tumors (Figs. 5L–N).

Figure 5.

Lowering down HDL-cholesterol levels reduced cholesterol contents in xenograft ccRCC derived from the tumors accumulating cholesterol. (A, F and K) Mice were fed with control diet or that contained 0.5% probucol (wt/wt) for 1 week prior to tumor implantation. The mice were fed with the same control diet or that containing probucol after the tumor implantation, and sacrificed 6-8 weeks later depending on the lines of the tumor transplanted as described in Fig. 3A. The amount of cholesterol in different serum lipoprotein fractions averaged from 3-6 mice was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. (B, G and L) The amount of cholesterol in xenograft tumors from mice fed with or without probucol was quantified through mass spectroscopy. The statistical analysis was performed by unpaired two-tailed t-tests. (C and H) Expression of SR-B1 in xenograft tumors from mice fed with or without probucol was quantified by RT-QPCR. (D, E, I, J, M and N) Lipid droplets were detected through fluorescent microscopy in cryosectioned xenograft tumors from mice fed with or without probucol as described in Fig. 4A. Scale bars = 100 μm.

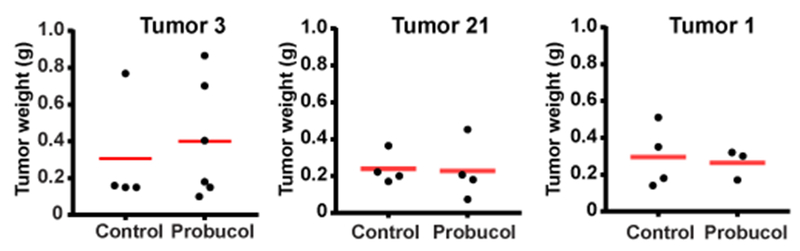

Although probucol decreased the cholesterol levels in xenograft tumors derived from tumors 3 and 21, this treatment did not affect growth of either line of the xenograft tumors (Fig. 6). Nor did this treatment prolong the life of the mice bearing xenograft tumors originated from tumor 3, which killed mice in 1-2 months. Thus, it appeared that cholesterol accumulation did not play an important role in growth of the xenograft ccRCC tumors.

Figure 6.

Growth of xenograft ccRCC was not affected by the treatment reducing cholesterol levels of the tumors. Weight was measured for xenograft tumors grown in mice fed with a control diet or that containing probucol shown in Fig. 5.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrate that increased uptake of HDL-cholesterol is likely the primary mechanism through which ccRCC acquires excess cholesterol. This conclusion is supported by the observation that expression levels of SR-BI, the receptor for HDL, were markedly elevated in ccRCC tumors that over-accumulated cholesterol. Consistent with an earlier report demonstrating that DNA methylation is frequently altered in ccRCC owing to VHL deficiency (26), we showed that reduction in methylation of CpG island present in SR-B1 contributed to increased expression of the gene in these tumors. Since SR-B1 is barely expressed in normal kidney tissues (27), this observation explains why only tumor cells but not benign renal tissues accumulate cholesterol in ccRCC patients. Another evidence supporting the conclusion is that lowering down levels of HDL-cholesterol in mice through probucol treatment reduced the amount of cholesterol in xenograft ccRCC tumors derived from those that accumulate higher levels of the lipid. Surprisingly, this treatment did not affect growth of the xenograft tumors. Nor did it improve conditions of the mice bearing the tumors. Thus, at least in this mouse xenograft model, cholesterol accumulation does not appear to play a major role for progression of ccRCC. If this is the case, then why do two-thirds of ccRCC contain excess cholesterol?

A possible explanation for the dilemma is that cholesterol accumulation may facilitate ccRCC development in human but this effect is unable to be reproduced in mouse-based experiments. For example, since ccRCC tumors have to be transplanted into immuno-deficient mice in order for them to grow in mouse kidneys, it is difficult to test whether cholesterol accumulation may help ccRCC to evade T cell-mediated immunity through the mouse xenograft model. Another possible explanation is that SR-B1 is a multifunctional protein. In addition to uptake of HDL-cholesterol, SR-B1 is critical for clearance of modified lipoproteins, and for various signaling reactions by serving as a cell surface receptor for many extracellular ligands besides HDL (28). Thus, it is possible that SR-B1 overexpression may facilitate development of ccRCC, but its beneficial reactions for the tumor are independent of uptake of HDL-cholesterol. From RNA-Seq results of hundreds of ccRCC tumors deposited into the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), PCSK6, SCD1, NOL3, PAI-1, SCT2 and GluT1 were identified as the genes whose expression was most positively correlated with SR-B1 mRNA. Remarkably, all these genes are known target genes of HIFαs (29–34). A possible explanation for this observation is that SR-B1 is transcriptionally activated by HIFαs so that expression of SR-B1 is co-activated with these known HIFα targets. This is unlikely the case, as treatment of mice with a HIF2α inhibitor, which markedly inhibited expression of HIF target genes in xenograft ccRCC, had no effect on SR-B1 expression (35). A more likely scenario is that SR-B1 overexpression may cooperates with loss of VHL to further stimulate HIFα transcriptional activity in ccRCC cells. Consistent with this idea, it was reported that SR-B1-mediated signaling reactions led to activation of HIF1α (36). If this is indeed the case, then cholesterol accumulation is the consequence of SR-B1 overexpression, but may contribute little to cancer development.

To more directly address the role of SR-B1 on development of ccRCC, we would have to knockout the gene from the tumor cells to determine whether such treatment inhibits progression of the cancer. Unfortunately, none of the cultured lines of ccRCC cells expressed SR-B1, nor do these cells over-accumulate cholesterol. It appears that the in vitro cell culture condition selects against ccRCC cells that overexpress SR-B1. The lack of a suitable cell culture system makes it extremely difficult to test this hypothesis, as there is currently no way to knockout a particular gene from xenograft tumors that can only be passaged and maintained in vivo.

In the current study, we observed that the majority of cholesterol in ccRCC cells was converted to cholesteryl esters stored in lipid droplets. Previous studies have demonstrated that conversion of cholesterol to cholesteryl esters is critical to prevent toxicity generated by over accumulation of free cholesterol (23, 37). Thus, it will be interesting to determine whether inhibiting ACAT activity will cause selective cytotoxicity to ccRCC cells that contain excess cholesterol, thereby providing a novel targeted therapy against these cancers.

As far as our knowledge is concerned, this is the first study that comprehensively measured sterols in ccRCC. In addition to cholesterol, cholestanol was also over-accumulated in ccRCC. Cholestanol, which only differs from cholesterol by the lack of a double bond between C5 and C6 of the sterol ring, is considered as a minor sterol in normal human body, as it exists at the concentration of 1/500 to 1/800 of cholesterol (38). Our analysis revealed that cholestanol accounted for 10% of cholesterol in both tumor and benign renal tissues, making it the second most abundant sterol in human kidneys. Cholestanol is known to be overproduced in patients with the genetic disease cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis owing to the deficiency in cholesterol 27-hydroxylase (38). This mechanism is unlikely to play a major role in production of cholestanol in kidneys, as 27-hydroxycholesterol, the product of the hydroxylase, was produced and accumulated in ccRCC. Judging by the increased production of 5,6-epoxycholesterol in ccRCC, we speculate that a novel metabolic pathway, which utilizes the epoxy sterol as the metabolic intermediate, might be responsible for converting cholesterol to cholestanol in kidneys. Understanding this metabolic pathway may provide insights into the functions of cholestanol in kidneys.

5. Conclusions

ccRCC cells acquire excess cholesterol through increased uptake of HDL-cholesterol as a result of elevated expression of SR-B1. While the majority of ccRCC tumors contain excess cholesterol, the lipid accumulation does not affect tumor growth in a mouse-based experimental model.

Supplementary Material

The majority of ccRCCs contain excess cholesterol

Elevated SR-B1 expression causes increased uptake of HDL-cholesterol in ccRCC

Cholesterol accumulation does not affect growth of xenograft ccRCC in mice

Cholesterol accumulation may be the consequence but not cause of ccRCC development

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Jeff Cormier for assistance in RT-QPCR, Dr. James Brugarolas for assistance in setting up the mouse xenograft model of ccRCC, Tissue Management Shared Resource of the Simmons Cancer Center in UTSW for distribution of primary ccRCC samples and their benign controls, and UTSW live cell imaging facility for confocal microscopy and training. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM-116106 and HL-20948) and the Welch Foundation (I-1832).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: ACAT, Acyl-coenzyme A cholesterol acyltransferase; ccRCC, clear cell renal cell carcinoma; GluT1, glucose transporter 1; HIF, hypoxia-induced factor; HMGCR, HMG-CoA A reductase; NOL3, nucleolar protein 3; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PCSK6, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 6; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; SQLE, squalene epoxidase; SR-B1, scavenger receptor BI; SREBPs, sterol regulatory element binding proteins; STC2, stanniocalcin 2.

References

- 1.Keefe SM, Nathanson KL, Kimryn Rathmell W. The molecular biology of renal cell carcinoma. Seminars in Oncology. 2013;40(4):421–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saito K, Arai E, Maekawa K, Ishikawa M, Fujimoto H, Taguchi R, et al. Lipidomic signatures and associated transcriptomic profiles of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Udayakumar D, Cai L, Hu Z, Kapur P, Kho E-Y, et al. Addressing metabolic heterogeneity in clear cell renal cell carcinoma with quantitative Dixon MRI. JCI Insight. 2017;2(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drabkin HA, Gemmill RM. Cholesterol and the development of clear-cell renal carcinoma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;12(6):742–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. The LDL receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(4):431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Cholesterol feedback: from Schoenheimer’s bottle to Scap’s MELADL. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Supplement):S15–S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen W-J, Azhar S, Kraemer FB. SR-B1: A unique multifunctional receptor for cholesterol influx and efflux. Ann Rev Physiol. 2018;80(1):95–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prolyl Myllyharju J. 4-hydroxylases, master regulators of the hypoxia response. Acta Physiol. 2013;208(2): 148–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dengler VL, Galbraith MD, Espinosa JM. Transcriptional regulation by hypoxia inducible factors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol BioL. 2014;49(1): 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen C, Kaelin WG Jr. The VHL/HIF axis in clear cell renal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(1): 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996;271(5248):518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pavía-Jiménez A, Tcheuyap VT, Brugarolas J. Establishing a human renal cell carcinoma tumorgraft platform for preclinical drug testing. Nat Protocols. 2014;9(8):1848–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald JG, Smith DD, Stiles AR, Russell DW. A comprehensive method for extraction and quantitative analysis of sterols and secosteroids from human plasma. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(7): 1399–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang G, Yang J, Horton JD, Hammer RE, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Diminished hepatic response to fasting/refeeding and liver X receptor agonists in mice with selective deficiency of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(11):9520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horton JD, Shimano H, Hamilton RL, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Disruption of LDL receptor gene in transgenic SREBP-1a mice unmasks hyperlipidemia resulting from production of lipid-rich VLDL. J Clin Invest. 1999; 103(7): 1067–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343(6257):425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horton JD, Shah NA, Warrington JA, Anderson NN, Park SW, Brown MS, et al. Combined analysis of oligonucleotide microarray data from transgenic and knockout mice identifies direct SREBP target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(21): 12027–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang T, Espenshade PJ, Wright ME, Yabe D, Gong Y, Aebersold R, et al. Crucial step in cholesterol homeostasis: sterols promote binding of SCAP to INSIG-1, a membrane protein that facilitates retention of SREBPs in ER. Cell. 2002; 110(4):489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Tall AR. Role of HDL, ABCA1, and ABCG1 transporters in cholesterol efflux and immune responses. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol. 2010;30(2): 139–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denard B, Pavia-Jimenez A, Chen W, Williams NS, Naina H, Collins R, et al. Identification of CREB3L1 as a biomarker predicting doxorubicin treatment outcome. PLoS ONE. 2015; 10(6):e0129233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu Z, Li J, Kuang Z, Wang M, Azhar S, Guo Z. Cell-specific polymorphism and hormonal regulation of DNA methylation in scavenger receptor class B, type I. DNA Cell Biol. 2016;35(6):280–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walther TC, Farese RV. Lipid droplets and cellular lipid metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81(1):687–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang T-Y, Li B-L, Chang CCY, Urano Y. Acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferases. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(1):E1–E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Brochu Ml, Wang SP, Rochdi L, Côté Mn, Mitchell G, et al. Hormone-sensitive lipase deficiency in mice causes lipid storage in the adrenal cortex and impaired corticosterone response to corticotropin stimulation. Endocrinology. 2002;143(9):3333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miettinen HE, Rayburn H, Krieger M. Abnormal lipoprotein metabolism and reversible female infertility in HDL receptor (SR-BI)–deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001; 108( 11): 1717–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson CM, Lefebvre F, Poon BP, Bousard A, Fan X, Lathrop M, et al. Consequences of VHL loss on global DNA methylome. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao G, Garcia CK, Wyne KL, Schultz RA, Parker KL, Hobbs HH. Structure and localization of the human gene encoding SR-BI/CLA-1: evidence for transcriptional control by steroidogenic factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(52):33068–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linton MF, Tao H, Linton EF, Yancey PG. SR-BI: A multifunctional receptor in cholesterol homeostasis and atherosclerosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2017;28(6):461–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Schgoer W, Beer AGE, Jeschke J, Leierer J, Theurl M, et al. Hypoxia up-regulates the angiogenic cytokine secretoneurin via an HIF-1α- and basic FGF-dependent pathway in muscle cells. FASEB J. 2007;21(11):2906–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Wang H, Zhang J, Lv J, Huang Y. Positive feedback loop and synergistic effects between hypoxia- inducible factor- 2α and stearoyl–CoA desaturase- 1 promote tumorigenesis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(4):416–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ao J-e, Kuang L-h, Zhou Y, Zhao R, Yang C-m. Hypoxia-inducible Factor 1 regulated ARC expression mediated hypoxia induced inactivation of the intrinsic death pathway in p53 deficient human colon cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;420(4):913–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kietzmann T, Roth U, Jungermann K. Induction of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene expression by mild hypoxia via a hypoxia response element binding the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in rat hepatocytes. Blood. 1999;94(12):4177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Law AYS, Lai KP, Ip CKM, Wong AST, Wagner GF, Wong CKC. Epigenetic and HIF-1 regulation of stanniocalcin-2 expression in human cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(8): 1823–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C, Pore N, Behrooz A, Ismail-Beigi F, Maity A. Regulation of glut1 mRNA by Hypoxia-inducible Factor-1: Interaction between H-ras and hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(12):9519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen W, Hill H, Christie A, Kim MS, Holloman E, Pavia-Jimenez A, et al. Targeting renal cell carcinoma with a HIF-2 antagonist. Nature. 2016;539:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan JTM, Prosser HCG, Vanags LZ, Monger SA, Ng MKC, Bursill CA. High-density lipoproteins augment hypoxia-induced angiogenesis via regulation of post-translational modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. FASEB J. 2013;28(1):206–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang L-H, Gui J, Artinger E, Craig R, Berwin Brent L, Ernst Patricia A, et al. Acatl gene ablation in mice increases hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation in bone marrow and causes leukocytosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vase Biol. 2013;33(9):2081–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seyama Y Cholestanol metabolism, molecular pathology, and nutritional implications. J Med Food. 2003;6(3):217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.