Abstract

Background

Local injection of BaCl2 is an established model of acute injury to study the regeneration of skeletal muscle. However, the mechanism by which BaCl2 causes muscle injury is unresolved. Because Ba2+ inhibits K+ channels, we hypothesized that BaCl2 induces myofiber depolarization leading to Ca2+ overload, proteolysis, and membrane disruption. While BaCl2 spares resident satellite cells, its effect on other tissue components integral to contractile function has not been defined. We therefore asked whether motor nerves and microvessels, which control and supply myofibers, are injured by BaCl2 treatment.

Methods

The intact extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle was isolated from male mice (aged 3–4 months) and irrigated with physiological salt solution (PSS) at 37 °C. Myofiber membrane potential (Vm) was recorded using sharp microelectrodes while intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) was evaluated with Fura 2 dye. Isometric force production of EDL was measured in situ, proteolytic activity was quantified by calpain degradation of αII-spectrin, and membrane disruption was marked by nuclear staining with propidium iodide (PI). To test for effects on motor nerves and microvessels, tibialis anterior or gluteus maximus muscles were injected with 1.2% BaCl2 (50–75 μL) in vivo followed by immunostaining to evaluate the integrity of respective tissue elements post injury. Data were analyzed using Students t test and analysis of variance with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Addition of 1.2% BaCl2 to PSS depolarized myofibers from − 79 ± 3 mV to − 17 ± 7 mV with a corresponding rise in [Ca2+]i; isometric force transiently increased from 7.4 ± 0.1 g to 11.1 ± 0.4 g. Following 1 h of BaCl2 exposure, 92 ± 3% of myonuclei stained with PI (vs. 8 ± 3% in controls) with enhanced cleavage of αII-spectrin. Eliminating Ca2+ from PSS prevented the rise in [Ca2+]i and ameliorated myonuclear staining with PI during BaCl2 exposure. Motor axons and capillary networks appeared fragmented within 24 h following injection of 1.2% BaCl2 and morphological integrity deteriorated through 72 h.

Conclusions

BaCl2 injures myofibers through depolarization of the sarcolemma, causing Ca2+ overload with transient contraction, leading to proteolysis and membrane rupture. Motor innervation and capillarity appear disrupted concomitant with myofiber damage, further compromising muscle integrity.

Keywords: Skeletal muscle, Motor innervation, Capillary supply, Neuromuscular junction

Background

Acute injury to skeletal muscle initiates a coordinated process of tissue degeneration and regeneration that encompasses inflammation; digestion of damaged components; activation, proliferation, and differentiation of resident myogenic stem cells (satellite cells); and maturation of nascent myofibers [1, 2]. While different injury models (freeze injury, cardiotoxin, Marcaine™, and BaCl2) induce variable degrees of tissue damage and inflammation [3–5], the advantages of chemical injury with BaCl2 include both ease of use and its ability to reproducibly damage myofibers while preserving their associated satellite cells [3, 6–9] (Additional file 1). However, the mechanism by which BaCl2 exposure leads to the death of skeletal muscle myofibers has not been identified. The divalent cation Ba2+ blocks inward rectifying potassium channels (KIR) at concentrations of 10–100 μM [10] and serves as a broad spectrum K+ channel inhibitor at concentrations ≥ 1 mM [11, 12]. Thus, injection of 1.2% BaCl2 (~ 57 mM), as used to induce muscle damage [3, 6–9], would be predicted to depolarize myofibers. In turn, depolarization can activate L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (CaV1.1) in the sarcolemma, leading to increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) via release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and influx from the extracellular fluid [13, 14]. Sufficient elevation of [Ca2+]i initiates proteolysis, leading to degradation of contractile proteins and cell membranes [15, 16]. We therefore tested the hypothesis that BaCl2 injures skeletal muscle through myofiber depolarization, with elevated [Ca2+]i leading to proteolysis and rupture of the sarcolemma.

Motor axons and microvessels are intimately associated with myofibers. At the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), myelinated axons projecting from α motor neurons in the spinal cord terminate and are covered by perisynaptic Schwann cells which overlay postsynaptic clusters of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [17]. Arterioles control the perfusion of capillary networks that collectively span the entire length of myofibers to provide oxygen and nutrients essential to supporting contractile activity [18]. While BaCl2 can damage the capillary supply [3], it is unknown whether concomitant injury occurs to the motor nerves that control myofiber contraction. Therefore, also we tested whether local injection of BaCl2 disrupts the integrity of NMJs and capillaries concomitant with injuring myofibers.

Methods

Aim, design, and setting

The aim of this study was to determine how BaCl2 injures skeletal muscle myofibers and whether motor innervation and microvascular supply are concomitantly disrupted by exposure to BaCl2. We studied the acute effects of BaCl2 exposure on membrane potential (Vm), [Ca2+]i, membrane integrity, αII-spectrin degradation, and force production in extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles. Neuromuscular synapses were studied in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle and the microcirculation was studied in the gluteus maximus (GM) muscle at 0 (control) and 1–3 days post injury (dpi) following local injection of BaCl2.

Animal care and use

All protocols and experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri (Columbia, MO, USA). Procedures were performed on male mice (age, 3–4 months; weight, ~ 30 g) of the following strains: C57BL/6J (WT) (Jackson Labs, n = 31), D2-Tg(S100B-EGFP)1Wjt/J (S100B-GFP) (Jackson Labs, n = 6); and Cdh5-CreERT2:ROSA-mTmG (Cdh5-mTmG) (cross of VE-cadherin-CreERT2 mice [19] and Rosa26mTmG mice (007676 Jackson Labs)), (n = 3). Cre recombination was induced through intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg tamoxifen (Cat. # T5648, Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA; 1 mg/100 μL in peanut oil) on 3 consecutive days with at least 1 week allowed prior to further study. Mice were housed locally on a 12-h light-dark cycle at ~ 23 °C, with freshwater and food available ad libitum.

To induce muscle injury in vivo, mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively; intraperitoneal injection), the skin was shaved over the muscle of interest, and then 1.2% BaCl2 was injected unilaterally into the TA (50 μL [9]) or under the GM (75 μL [8]) as described. Mice were kept warm during recovery and then returned to their cage. On the day of an experiment, mice were anesthetized (as above). Following tissue harvest, mice were killed by exsanguination.

Membrane potential

The EDL muscle was used for these experiments because it can be isolated and secured in vitro by its tendons to approximate in vivo muscle length without damaging myofibers. An EDL muscle was removed from the anesthetized mouse, pinned onto transparent rubber (Sylgard 124; Midland, MI, USA), placed in a tissue chamber (RC-37 N; Warner Instruments; Hamden, CT, USA), transferred to the stage of a Nikon 600FN microscope (Tokyo, Japan), and irrigated (3 mL min− 1) with standard physiological salt solution (PSS; pH 7.4) of the following composition: 140 mM NaCl (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA, USA), 5 mM KCl (Fisher), 1 mM MgCl2 (Sigma), 10 mM HEPES (Sigma), 10 mM glucose (Fisher), and 2 mM CaCl2 (Fisher) while maintained at 37 °C.

The membrane potential (Vm) of myofibers was recorded with an amplifier (AxoClamp 2B, Molecular Devices; Sunnyvale, CA, USA) using sharp microelectrodes pulled (P-97, Sutter Instruments; Novato, CA, USA) from glass capillary tubes (GC100F-10, Warner, Hamden, CT, USA) filled with 2 M KCl (~ 150 MΩ) with a Ag/AgCl pellet serving as a reference electrode [20]. The amplifier was connected to a data acquisition system (Digidata 1322A, Molecular Devices) and an audible baseline monitor (ABM-3, World Precision Instruments; Sarasota, FL, USA). Successful impalements were indicated by sharp negative deflection of Vm, stable Vm for > 1 min, and prompt return to ~ 0 mV upon withdrawal of the electrode. Data were acquired at 1 kHz on a personal computer using AxoScope 10.1 software (Molecular Devices). Once a single myofiber was impaled, Vm was recorded for at least 5 min to establish a stable baseline. PSS containing 1.2% BaCl2 then irrigated the muscle at 37 °C. Additional experiments were performed using isotonic substitution of BaCl2 for NaCl (final [NaCl] = 54 mM vs. 140 mM in standard PSS) to test whether differences in osmolality affected responses during exposure to 1.2% BaCl2. Each of these experiments represents one myofiber in one EDL; each muscle was obtained from a separate mouse.

Calcium photometry

Intracellular [Ca2+] responses were measured as reported [20]. An EDL muscle was incubated in either standard PSS or in Ca2+-free PSS containing 3 mM (ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA)). Each solution contained 1 μM Fura 2-AM (Cat. # F4185, Fisher); a muscle was incubated for 60 min at 37 °C and then washed for 20 min to remove excess dye. The 1.2% BaCl2 was then added while fluorescence was recorded at 510 nm during alternative excitation (10 Hz) at 340 nm and 380 nm using a × 20 objective (Nikon Fluor20, numerical aperture (NA) = 0.45). Data were acquired using IonWizard 6.3 software (IonOptix; Milford, MA) on a personal computer and expressed as fluorescence (F) ratios (F340/F380) after subtracting autofluorescence recorded prior to dye loading.

Membrane damage

As an index of myofiber membrane damage, EDL muscles were treated for 1 h with standard PSS, 1.2% BaCl2 dissolved in standard PSS, or 1.2% BaCl2 dissolved in Ca2+-free PSS then stained for 20 min with membrane-permeant Hoechst 33342 (1 μM, Cat. # H1399, Fisher) and membrane-impermeant propidium iodide (PI; 2 μM, Cat. # P4170, Sigma) in PSS. These dyes stain the nuclei of all cells and nuclei of cells with disrupted membranes, respectively [21]. Muscles were then washed for 30 min in standard PSS and image stacks were acquired with a water immersion objective (× 40; NA = 0.8) coupled to a DS-Qi2 camera with Elements software (version 4.51) on an E800 microscope (all from Nikon). Stained nuclei were counted within a defined region of interest (ROI; 300 × 400 μm) of image stacks using Image J (NIH) to quantify the percentage (%) of total nuclei stained with PI.

Western blot for αll-spectrin degradation

EDL muscles were secured to approximate in situ length and incubated in either standard PSS or 1.2% BaCl2 in PSS for 1 h at 37 °C then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Following homogenization, protein concentration of the supernatant was quantified with the Bradford method (Cat. # 5000006; Sigma). Protein concentration of each sample was normalized in 4x Laemmli sample buffer (Cat. # 1610747, Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA) containing 5% dithiothreitol. Samples were loaded on 4–20% gradient Mini-Protein TGX gels (Bio-Rad) for electrophoresis and transferred to LF-PVDF membranes (Millipore; Burlington, MA). Following 2 h blocking in 5% milk, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C and again for 3 h at 25 °C in primary antibody raised against αII-spectrin (1:250, Cat. # sc48382, Santa Cruz; Dallas, TX, USA). A secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 800 IgG, 1:5000; Cat. # 926–32,212, Li-Cor Biosciences; Lincoln, NE, USA) was used to quantify protein differences with an Li Cor Odyssey Fc imaging system. Western blots were normalized to total protein according to the recommendations for fluorescent Western blotting [22] using Revert total protein stain (Cat. # 926-11010, Li-Cor). The 40 kDa bands correlate with the total protein in each lane and are shown to represent equal protein loading [23, 24].

Muscle force

The EDL was prepared for in situ measurements as described [25]. Briefly, in an anesthetized mouse, a 2-0 suture was placed around the left patellar tendon. The distal tendon of the EDL was isolated, secured in 2-0 suture, and then severed from its insertion. The mouse was placed prone on a plexiglass board and the patellar tendon was secured to a vertical metal peg immobilized in the board. The distal EDL tendon was tied to a load beam (LCL-113G; Omega, Stamford, CT, USA) coupled to a Transbridge amplifier (TBM-4; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). The load beam was attached to a micrometer for adjusting optimal length (Lo) as determined during twitch contractions at 1 Hz [8]. A strip of KimWipe® was wrapped around the EDL and 1.2% BaCl2 irrigated the EDL (3 mL min− 1) while resting force was evaluated for 1 h with Power Lab acquisition software (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) on a personal computer.

Neuromuscular junction histology

In a mouse strain with genetically labeled Schwann cells (S100B-GFP/Kosmos [26]), the TA muscle of one hindlimb was injured with BaCl2 injection and the contralateral limb was left intact. Mice were studied at 0 (control), 1, 2, and 3 dpi. At each time point, the hindlimb was excised, the TA was removed, and myofibers were gently teased apart with fine forceps in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to facilitate antibody penetration. Samples were fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS 3 times for 5 min, and stained for neurofilament-heavy (primary antibody: chicken anti-mouse, 1:400; Cat. # CPCA-NF-H Encor Biotechnology Inc.; Gainesville, FL, USA; secondary antibody: goat anti-chicken, 647 IgY, 1:1000, Cat. # A-21449, Fisher); each antibody was incubated overnight at 4 °C followed by washing in PBS 6 times for 30 min. Nicotinic receptors were then stained with α-bungarotoxin conjugated to tetramethylrhodamine (1:500, Cat. # 00014, Biotrend; Koln, Germany) for 2 h at room temperature and washed in PBS prior to imaging. Images were acquired with a × 25 water immersion objective (NA = 0.95) at × 1.75 digital zoom on an inverted laser scanning confocal microscope (TCS SP8, Leica Microsystems Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) using Leica LAX software. Image stacks (thickness, ~ 150 μm) were used to resolve NMJ morphology.

Microvessel histology

The GM was used for histological analysis of skeletal muscle microvasculature based on it being a thin (100–200 μm), planar muscle which facilitates imaging of microvessels throughout the tissue [8]. A GM was dissected away from its origin along the lumbar fascia, sacrum, and iliac crest, reflected away from the body, and spread onto a transparent rubber pedestal. Superficial connective tissue was removed using microdissection and the muscle was severed from its insertion. To image capillary networks, the unfixed GM was immersed in PBS, a small glass block was placed on top to gently flatten the muscle, and image stacks were acquired as described for NMJs. In Cdh5-mTmG mice, all endothelial cells are labeled with membrane-localized GFP following tamoxifen-induced Cre recombination.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Student’s t test and one-way Analysis of Variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test post hoc when appropriate (Prism 5, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Summary data are presented as means ± SEM; n refers to the number of preparations (each from a different mouse) in a given experimental group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

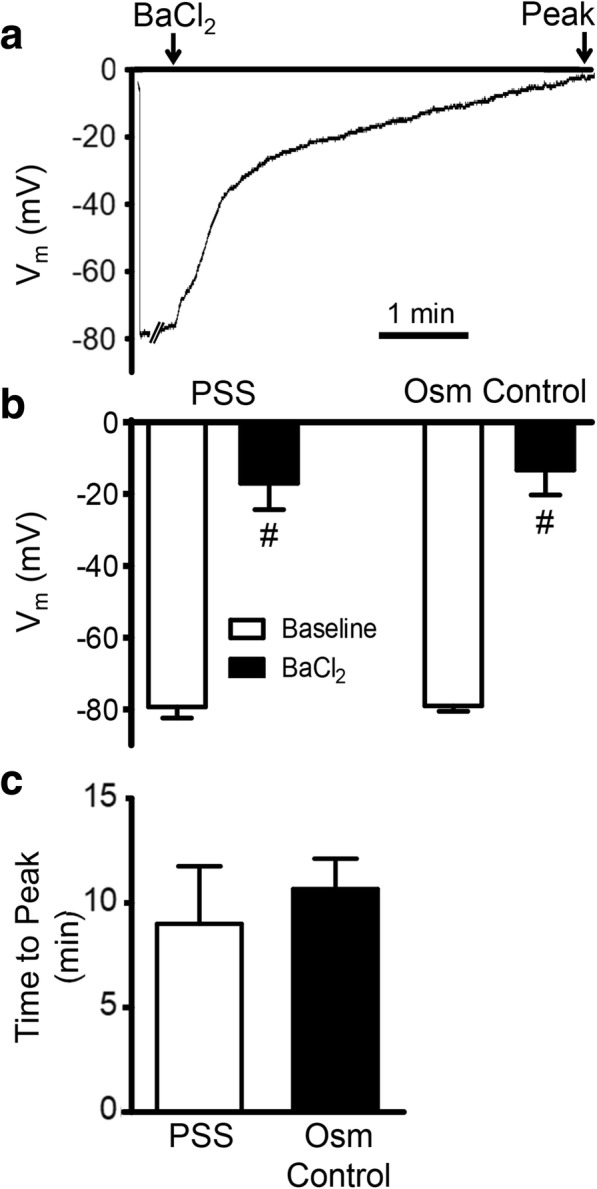

BaCl2 depolarizes myofibers

Resting Vm of EDL myofibers was ~ − 80 mV, consistent with previous reports [27–29]. The myofiber sarcolemma contains multiple K+ channels, including KV, KIR, KCa, and KATP [30]. Consistent with BaCl2 acting as a broad spectrum K+ channel inhibitor [12], the addition of 1.2% BaCl2 to standard PSS irrigating the muscle depolarized myofibers from − 79 ± 3 mV at rest to − 17 ± 7 mV (Fig. 1; P = 0.001). A rapid phase of depolarization occurred within the first 1–2 min followed by a slower phase (Fig. 1a). In some cells, Vm reached 0 mV indicating cell death. A similar depolarization was recorded when BaCl2 was substituted isotonically for NaCl (osmotic control, Fig. 1b; P = 0.001), illustrating that the effects of BaCl2 were not due to osmotic changes from its addition to PSS. There were no differences in ΔVm (vehicle 62 ± 5 mV, osmotic control 66 ± 8 mV; P = 0.72), or the time course (Fig. 1c; P = 0.68) between respective solutions containing 1.2% BaCl2. In the absence of BaCl2, Vm remained stable (~ − 80 mV) for at least 30 min (n = 3).

Fig. 1.

BaCl2 depolarizes skeletal muscle myofibers. a Representative continuous recording of Vm illustrates depolarization of mouse EDL myofiber upon exposure to 1.2% BaCl2. b Summary data for Vm are at resting baseline, at peak depolarization during 1.2% BaCl2 added to standard PSS and to PSS in which BaCl2 replaced NaCl for osmotic (Osm) control. c Summary data for time to peak depolarization during 1.2% BaCl2 added to standard PSS, and to PSS in which BaCl2 replaced NaCl for Osm control. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3–6 myofibers, each from one EDL muscle per mouse). #P ≤ 0.05 vs. baseline

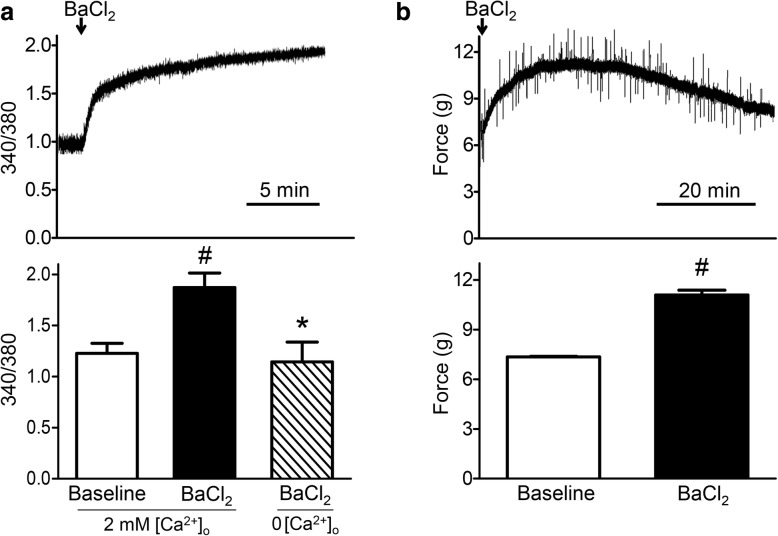

BaCl2 increases [Ca2+]i and muscle force

A primary consequence of myofiber depolarization in healthy muscle is internal release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via coupling to L-type Ca2+ channels (i.e., dihydropyridine receptors), which act as voltage sensors in the sarcolemma [31]. The addition of 1.2% BaCl2 to standard PSS evoked a robust increase in myofiber [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2a; P < 0.001). Isotonic BaCl2 solution resulted in a similar increase in [Ca2+]i (F340/F380 increased from 1.18 ± 0.02 (baseline) to 1.58 ± 0.06 (BaCl2); n = 3). In contrast, adding 1.2% BaCl2 to Ca2+-free PSS had no significant effect on [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2a). In the absence of BaCl2, Fura 2 fluorescence remained stable at the resting baseline for at least 30 min (n = 3).

Fig. 2.

BaCl2 increases [Ca2+]i and muscle force. a Top: representative continuous recording of F340/F380 illustrates intracellular Ca2+ accumulation. Bottom: summary data for F340/F380 at rest (baseline) and during peak response to 1.2% BaCl2 in PSS (n = 5) and 1.2% BaCl2 in Ca2+-free PSS (0 [Ca2+]o) (n = 3). b Top: representative continuous recording of force developed by EDL in situ at optimum resting length (Lo) in response to irrigation with 1.2% BaCl2 for 1 h. Bottom: summary data for resting and peak force in response to 1.2% BaCl2; values are means ± SEM (n = 4 muscles). #P ≤ 0.05 vs. baseline, *P ≤ 0.05 vs. 1.2% BaCl2 in standard PSS with 2 mM extracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]o)

Irrigating the EDL in situ with 1.2% BaCl2 in standard PSS increased resting force from 7.4 ± 0.1 to 11.1 ± 0.4 g over ~ 30 min, which then returned to baseline during the 60 min exposure (Fig. 2b; P = 0.001). Whereas a rise in [Ca2+]i activates the contractile proteins [32], sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i stimulates mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can impair cross-bridge function [33]. Ca2+-activated proteolysis disrupts the integrity of contractile proteins [15], which we surmise may have occurred in the present experiments.

BaCl2 activates proteolysis and disrupts membranes

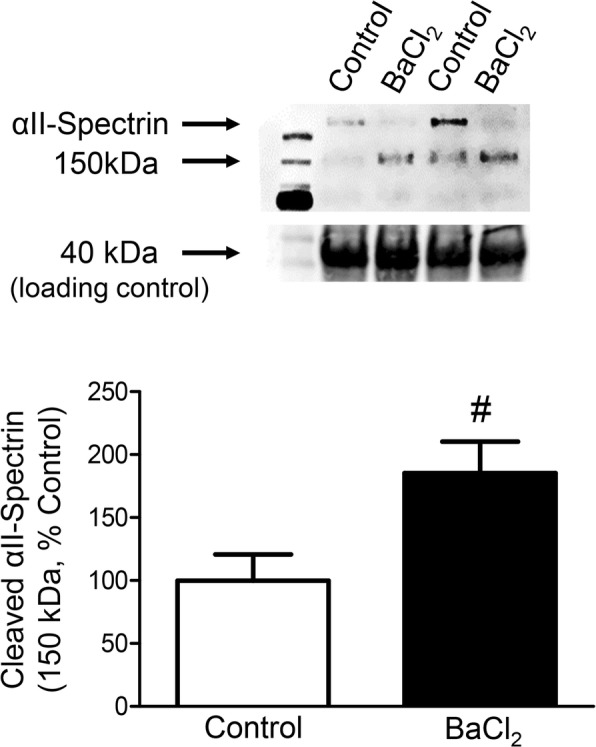

Elevating [Ca2+]i leads to degradation of muscle fibers through proteolysis by Ca2+-activated neutral proteases [15, 16]. For example, calpain is activated in two primary steps: (1) the inactive enzyme translocates to the sarcolemma where the N-terminus is cleaved through autolysis releasing active calpain, and (2) two Ca2+ ions bind to the protease domain to maintain the active site [34]. Active calpain cleaves skeletal muscle structural proteins including titan, nebulin, and αII-spectrin [35]. In EDL muscles exposed to 1.2% BaCl2 in standard PSS for 1 h, αII-spectrin was cleaved from 240 to a 150 kDa product (Fig. 3; P = 0.02), which was accompanied by an increase in the ratio of cleaved: total αII-spectrin (control = 2.8 ± 1.25; BaCl2 = 17.9 ± 8.9 (P = 0.12, n = 6)).

Fig. 3.

BaCl2 increases calpain activity. Representative Western blots (top) and mean densitometric data (bottom) for αII-spectrin from EDL muscles treated with standard PSS (Control) or 1.2% BaCl2 in standard PSS for 1 h. The αII-spectrin band at 240 kDa and its cleavage product at 150 kDa were both normalized to total protein reflected by the 40 kDa band, which was not different between samples. Summary data are means ± SEM (n = 6 muscles). #P ≤ 0.05 vs. control

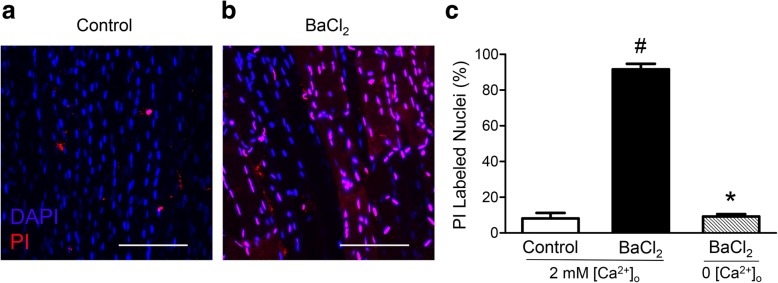

Myonuclei in EDL muscles treated with PSS exhibited minimal PI staining after 1 h (8%) while nearly all myonuclei (92%) were stained following 1 h of exposure to 1.2% BaCl2, thus indicating gross disruption of sarcolemma throughout the muscle (Fig. 4; P < 0.001). Removal of Ca2+ from the irrigation solution prevented the incorporation of PI, demonstrating the importance of Ca2+ influx from the extracellular fluid in BaCl2-induced membrane disruption (Fig. 4c; P < 0.0001). Ca2+-activated calpain can stimulate several proapoptotic pathways. While calpain-activated caspase 12 promotes apoptosis through the “executioner” caspase 3 [36, 37], it can also cleave BH3-only protein (Bid) and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) to truncated Bid and truncated AIF, thereby causing mitochondrial membrane permeability and ensuing apoptosis [38].

Fig. 4.

BaCl2 disrupts myofiber plasma membranes. a, b Representative images of nuclear staining in EDL muscles after 1 h in standard PSS (control) and in 1.2% BaCl2 added to standard PSS. Propidium iodide (PI, red) identifies nuclei of cells with disrupted plasma membranes and Hoechst 33342 (blue) is membrane permeant and identifies all cell nuclei. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ (0 [Ca2+]o)ameliorated myonuclear staining with PI as in a. c Summary data for percentage of PI-labeled nuclei, calculated as (# red nuclei/# blue nuclei) × 100. Each region of interest contained ~ 150 myonuclei. Summary data are means ± SEM for n = 4–5 muscles per group. #P ≤ 0.05 vs. control, *P ≤ 0.05 vs. 1.2% BaCl2 in standard PSS with 2 mM [Ca2+]o. Scale bars, 100 μm

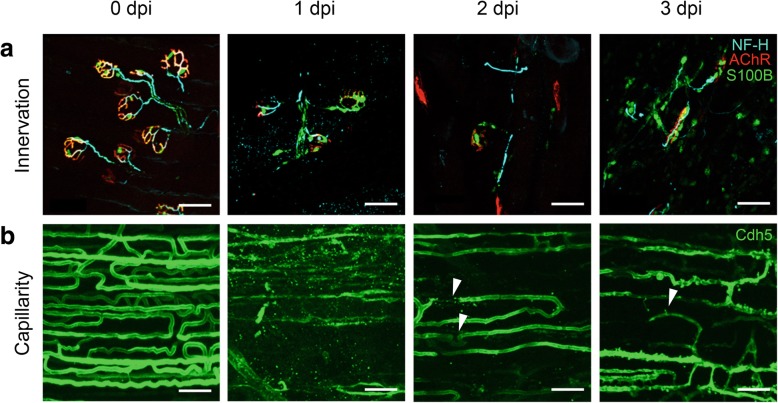

BaCl2 induces injury of motor axons and microvessels

In contrast to the integrity of pre- and postsynaptic elements characteristic of healthy NMJs, neurofilament-heavy staining at 1 dpi appeared fragmented, suggesting axonal disruption. Clusters of acetylcholine receptors also became dispersed along the laminar surface and Schwann cells began to migrate away from the NMJ, which progressed through 2 dpi (Fig. 5a). By 3 dpi, Schwann cells appear to associate with axonal fragments and AChR clusters. These data demonstrate that motor axons in the vicinity of BaCl2 injection undergo degeneration within 24 h that extends over 3 days, consistent with the time course of Schwann cell migration following axotomy [39].

Fig. 5.

Motor innervation and capillaries are disrupted by local BaCl2 injection. a Neuromuscular junctions in TA muscle. Schwann cells (green) are closely associated with axonal neurofilament-heavy (cyan; indicates motor axons) and overlay postsynaptic nicotinic receptors (red) at 0 dpi (uninjured control). Following injection of 1.2% BaCl2, NMJ components are dissociating at 1 dpi and fragmented at 2 and 3 dpi. b Capillaries in GM (green endothelial cells) are densely organized and align along myofibers in uninjured muscle (0 dpi). Following injection of 1.2% BaCl2, disrupted and fragmented capillaries are observed at 1–2 dpi (arrowheads) while evidence of capillary neoformation is apparent at 3 dpi (arrowhead). Scale bars, 50 μm. Color coding in 3 dpi panels applies to earlier timepoints for innervation and capillarity. NF-H, neurofilament heavy; AChR, nicotinic actetylcholine receptors; S100B, Schwann cells expressing GFP; Cdh5, endothelial cells expressing GFP

Uninjured muscle exhibits an orderly network of capillaries (Fig. 5b). Following BaCl2 injury, capillaries were fragmented at 1 dpi. By 3 dpi, anastomoses (interconnecting loops) began to appear between capillary sprouts. While these observations add new insight to the extent of tissue injury induced by BaCl2, our findings are consistent with structural damage of microvessels induced by BaCl2 at 2 dpi [3] and our recent report that capillary perfusion was disrupted at 1 dpi [8].

Discussion

Skeletal muscle comprises ~ 40% of body mass and has the remarkable ability to regenerate following injury due to resident satellite cells. Skeletal muscle injuries occur in multiple ways including disease, physical trauma, temperature extremes, eccentric contractions, and exposure to myotoxic agents [3–5]. Whereas myofibers follow a similar pattern of regeneration irrespective of the mechanism of injury [1, 40], the kinetics and involvement of satellite cells can vary with the nature of insult [3]. For example, freeze injury results in a dead zone of tissue that viable cells must penetrate, whereas local exposure to BaCl2 induces coordinated necrosis of myofibers with infiltration of inflammatory cells followed by sequential regeneration of myofibers [1, 3].

Unlike freeze damage, BaCl2-induced injury preserves satellite cells, which allows detailed examination of their gene expression, cell signaling, and regeneration kinetics in vivo. Remarkably, how BaCl2 kills myofibers has remained undefined. In accord with the ability of Ba2+ to block K+ channels [11, 12], we reasoned that it would depolarize myofibers, as the sarcolemma contains KV, KIR, KCa, and KATP channels [30]. The progression of depolarization we observed in EDL may reflect reliance on Cl− conductance for resting Vm in skeletal muscle, which can buffer the abrupt effect of changing the conductance of other ions [41]. Following BaCl2-induced depolarization, the present data show that increasing [Ca2+]i leads to proteolysis, membrane disruption, and myofiber death. Moreover, preventing the rise of [Ca2+]i by removing extracellular Ca2+ preserves membrane integrity as demonstrated by the paucity of myonuclei stained with PI under this condition (Fig. 4c). Myotoxicity through Ca2+-mediated proteolysis and membrane disruption subsequent to Ba2+ exposure is consistent with the action of biological agents known to disrupt myofibers such as bee, wasp, and snake venoms [42–44].

BaCl2 has been used to study the pathophysiology of hypokalemia, a clinical condition which depolarizes muscle fibers through reduced K+ efflux [10, 45]. In hypokalemia, the SR is integral to myofiber disruption [10, 46, 47], with Ca2+ release from internal stores being a primary source of the elevated [Ca2+]i that contributes to muscle injury. While the relative contribution of Ca2+ release from internal stores vs. influx through L-type channels during BaCl2 injury remains to be determined, the SR is the principal source of elevating [Ca2+]i during muscle contractions [48]. Consistent with this effect, we observed transient contraction of the EDL upon exposure to BaCl2 that peaked with the rise in [Ca2+]i over 20–30 min (Fig. 2). The recovery to resting (passive) tension during the ensuing 30 min may reflect disruption of the contractile machinery. This interpretation is consistent with the degradation of αII-spectrin we observed within 60 min of BaCl2 exposure (Fig. 3). Once in the cytoplasm, Ba2+ can enter mitochondria [49] and generate superoxide by increasing electron flow from Ca2+-sensitive citric acid cycle dehydrogenases and thereby dissipate mitochondrial membrane potential [50]. The ensuing disruption of mitochondria releases cytochrome C into the cytosol to initiate intrinsic apoptosis, culminating in the activation of caspase 3 and cell death [36].

Nerve and microvessel injury

Motor nerves and microvessels control and supply myofibers of intact skeletal muscle by initiating contraction and delivering nutrients in response to metabolic demand [51]. Given their intimate physical proximity and shared signaling events, we hypothesized that muscle injury induced by BaCl2 would disrupt motor axons and capillaries. Similar to the time course of myofiber disruption [3], the present data illustrate that motor nerves and microvessels appear fragmented within 24 h following local injection of BaCl2 (Fig. 5).

It is unclear whether nerves and capillaries undergo damage directly from BaCl2 or indirectly as a secondary effect of myofiber disruption. Mechanical changes within the injured myofiber can lead to degeneration of the NMJ. For example, with local injury, myofilaments contract on both sides of the injured site, leaving an empty tube with partially retracted nerve terminals juxtaposed to the site [52]. While mechanisms of axon retraction remain to be defined, the change in cell shape suggests that it is a consequence of cytoskeletal remodeling in response to a retraction program or loss of the ability to maintain the cytoskeleton [53]. Because it is a cytoskeletal protein integral to the structure of cell membranes, degradation of αII-spectrin is disruptive to the sarcolemma and contributes to fragmentation of motor nerve synapses with dissolution of AChR clusters (Fig. 5).

Disruption of capillaries occurs in multiple models of muscle injury [3]. The present data are the first to illustrate that these events coincide with the loss of neuromuscular integrity. Thus, key elements of myofiber control and supply are similarly affected, with loss of structural integrity occurring during the initial 24 h (1 dpi) and initial stages of recovery apparent at 3 dpi. In addition to myofibers, vessels and nerves may undergo calpain-dependent degradation [54, 55]. Thus, while skeletal muscle consists primarily of myofibers, the increase in calpain-specific αII-spectrin degradation measured in our homogenates (Fig. 3) may be derived from multiple cell types. As we have observed directly with intravital microscopy in the GM, the inflammatory response to BaCl2 begins within 1–2 h of exposure (Fernando and Segal, unpublished observations from [8]). Infiltration of the tissue with neutrophils, monocytes, and pro-inflammatory macrophages ensues over the next 2–3 days, thereby disrupting all tissue components indiscriminately [3, 56] through activation of additional proteolytic pathways and oxidative modification of proteins to accelerate proteolysis [36].

Conclusion

Skeletal muscle injury induced by BaCl2 is widely used as a method for studying myofiber damage and regeneration [3, 6–9]. Because the mechanism of BaCl2-induced injury was unknown, the goal of the present study was to define the nature of myofiber damage and ascertain whether associated tissue elements were similarly affected. Using complementary ex vivo preparations of skeletal muscle, we demonstrate that acute exposure to BaCl2 causes myofiber damage via Ca2+-dependent proteolysis secondary to membrane depolarization. Further, motor axons and microvessels appear to undergo damage with a similar time course to the disruption of myofibers. These data provide a foundation for investigating how major tissue components responsible for skeletal muscle structure and function (i.e., myofibers, motor nerves, and microvessels) respond to and interact during muscle injury and regeneration.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Satellite cells are spared from BaCl2-induced death in vitro. Treatment with BaCl2 in vivo is used to induce myofiber damage leading to satellite cell activation and muscle regeneration. To formally demonstrate the differential effects of BaCl2 on myofibers and their associated satellite cells, we isolated single muscle fibers from the EDL muscle and exposed them to either saline or 1.2% BaCl2 in the presence of propidium iodide (PI) to label nuclei with disrupted laminae (dead or dying). Fibers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde then stained for expression of the satellite cell marker CD34 (rat monoclonal RAM-34, eBioscience at 1:200) (arrows). Myofibers fixed at 0 min (A) or after 50 min in Ca2+, Mg2+-free PBS (B) retain their morphology and integrity and do not incorporate PI in either satellite cell nuclei or myonuclei. In contrast, myofibers exposed to 1.2% BaCl2 for 50 min (C) have hypercontracted, lost their structural integrity, and possess PI-labeled nuclei. However, satellite cells associated with these fibers have not incorporated PI. D, Addition of 1.2% BaCl2 to isolated single fibers leads to elevated [Ca2+]i as observed in whole-muscle preparations (Fig. 2). The severity and kinetics of BaCl2-induced myotoxicity for single fibers appear to be less than observed in our experiments using whole muscles. We hypothesize that the absence of fixed attachments at the ends of single myofibers may reduce the damaging membrane stress following Ca2+-induced hypercontraction. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]i

Intracellular calcium concentration

- [Ca2+]o

Extracellular calcium concentration

- AChR

Acetylcholine receptors

- AIF

Apoptosis-inducing factor

- Bid

BH3-only protein

- dpi

Days post injury

- EDL

Extensor digitorum longus

- EGTA

Ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- GM

Gluteus maximus

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- NMJ

Neuromuscular junction

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PSS

Physiological salt solution

- ROI

Region of interest

- TA

Tibialis anterior

- Vm

Membrane potential

Authors’ contributions

ABM and CEN share equal contribution to the experimental design, data acquisition and analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. NLJ assisted with the data acquisition and interpretation. CAF, DDWC, and SSS contributed to the conception and design of the experiments, interpretation of the data, and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

The study was supported by a Margaret Proctor Mulligan Professorship and a R37HL041026 to SSS from the National Institutes of Health; DDWC was supported by NIH R01AR067450.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Materials used in this study are commercially available.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri, Columbia (protocol reference no. 9220) and were performed in accord with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Aaron B. Morton and Charles E. Norton are co-first authors.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13395-019-0213-2.

References

- 1.Tidball JG. Mechanisms of muscle injury, repair, and regeneration. Compr Physiol. 2011;1(4):2029–2062. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carosio S, Berardinelli MG, Aucello M, Musaro A. Impact of ageing on muscle cell regeneration. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy D, Besnard A, Latil M, Jouvion G, Briand D, Thepenier C, et al. Comparative study of injury models for studying muscle regeneration in mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabebordbar M, Wang ET, Wagers AJ. Skeletal muscle degenerative diseases and strategies for therapeutic muscle repair. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:441–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benoit PW, Belt WD. Destruction and regeneration of skeletal muscle after treatment with a local anaesthetic, bupivacaine (Marcaine) J Anat. 1970;107(Pt 3):547–556. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tierney MT, Sacco A. Inducing and evaluating skeletal muscle injury by notexin and barium chloride. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1460:53–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3810-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casar JC, McKechnie BA, Fallon JR, Young MF, Brandan E. Transient up-regulation of biglycan during skeletal muscle regeneration: delayed fiber growth along with decorin increase in biglycan-deficient mice. Dev Biol. 2004;268(2):358–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernando CA, Pangan AM, Cornelison D, Segal SS. Recovery of blood flow regulation in microvascular resistance networks during regeneration of mouse gluteus maximus muscle. J Physiol. 2019;597(5):1401–1417. doi: 10.1113/JP277247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelison DD, Wilcox-Adelman SA, Goetinck PF, Rauvala H, Rapraeger AC, Olwin BB. Essential and separable roles for Syndecan-3 and Syndecan-4 in skeletal muscle development and regeneration. Genes Dev. 2004;18(18):2231–2236. doi: 10.1101/gad.1214204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallant EM. Barium-treated mammalian skeletal muscle: similarities to hypokalaemic periodic paralysis. J Physiol. 1983;335:577–590. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonev AD, Nelson MT. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in smooth muscle cells from Guinea pig urinary bladder. Am J Phys. 1993;264(5 Pt 1):C1190–C1200. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.5.C1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Phys. 1995;268(4 Pt 1):C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flucher BE, Tuluc P. How and why are calcium currents curtailed in the skeletal muscle voltage-gated calcium channels? J Physiol. 2017;595(5):1451–1463. doi: 10.1113/JP273423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho CH, Woo JS, Perez CF, Lee EH. A focus on extracellular Ca2+ entry into skeletal muscle. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(9):e378. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner PR, Westwood T, Regen CM, Steinhardt RA. Increased protein degradation results from elevated free calcium levels found in muscle from mdx mice. Nature. 1988;335(6192):735–738. doi: 10.1038/335735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan CJ. Role of intracellular calcium in promoting muscle damage: a strategy for controlling the dystrophic condition. Experientia. 1978;34(12):1531–1535. doi: 10.1007/BF02034655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimune H, Shigemoto K. Practical anatomy of the neuromuscular junction in health and disease. Neurol Clin. 2018;36(2):231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segal SS. Regulation of blood flow in the microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2005;12(1):33–45. doi: 10.1080/10739680590895028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Nakayama M, Pitulescu ME, Schmidt TS, Bochenek ML, Sakakibara A, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465(7297):483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norton CE, Segal SS. Calcitonin gene-related peptide hyperpolarizes mouse pulmonary artery endothelial tubes through KATP channel activation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315(2):L212–LL26. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00044.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norton CE, Sinkler SY, Jacobsen NL, Segal SS. Advanced age protects resistance arteries of mouse skeletal muscle from oxidative stress through attenuating apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide. J Physiol. 2019;15:3801–3816. doi: 10.1113/JP278255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaton SL, Roche SL, Llavero Hurtado M, Oldknow KJ, Farquharson C, Gillingwater TH, et al. Total protein analysis as a reliable loading control for quantitative fluorescent Western blotting. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn B, Beharry AW, Frye GS, Judge AR, Ferreira LF. NAD(P) H oxidase subunit p47phox is elevated, and p47phox knockout prevents diaphragm contractile dysfunction in heart failure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309(5):L497–L505. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00176.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton AB, Smuder AJ, Wiggs MP, Hall SE, Ahn B, Hinkley JM, et al. Increased SOD2 in the diaphragm contributes to exercise-induced protection against ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction. Redox Biol. 2018;20:402–413. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakim CH, Wasala NB, Duan D. Evaluation of muscle function of the extensor digitorum longus muscle ex vivo and tibialis anterior muscle in situ in mice. J Vis Exp. 2013;72. 10.3791/50183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Zuo Y, Lubischer J, Kang H, Tian L, Mikesh M, Marks A, et al. Fluorescent proteins expressed in mouse transgenic lines mark subsets of glia, neurons, macrophages, and dendritic cells for vital examination. J Neurosci. 2004;24(49):10999–11009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3934-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris JB. The resting membrane potential of fibres of fast and slow twitch muscles in normal and dystrophic mice. J Neurol Sci. 1971;12(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(71)90250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathes C, Bezanilla F, Weiss RE. Sodium current and membrane potential in EDL muscle fibers from normal and dystrophic (mdx) mice. Am J Physiol. 1991;261(4 Pt 1):C718–C725. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.4.C718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yensen C, Matar W, Renaud JM. K+-induced twitch potentiation is not due to longer action potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283(1):C169–C177. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00549.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maqoud F, Cetrone M, Mele A, Tricarico D. Molecular structure and function of big calcium-activated potassium channels in skeletal muscle: pharmacological perspectives. Physiol Genomics. 2017;49(6):306–317. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00121.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laver DR. Regulation of the RyR channel gating by Ca2+ and Mg2+ Biophys Rev. 2018;10(4):1087–1095. doi: 10.1007/s12551-018-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berchtold MW, Brinkmeier H, Müntener M. Calcium ion in skeletal muscle: its crucial role for muscle function, plasticity, and disease. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(3):1215–1265. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powers SK, Ji LL, Kavazis AN, Jackson MJ. Reactive oxygen species: impact on skeletal muscle. Compr Physiol. 2011;1(2):941–969. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang J, Zhu X. The molecular mechanisms of calpains action on skeletal muscle atrophy. Physiol Res. 2016;65(4):547–560. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei W, Cong J. The calpain system. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(3):731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powers SK, Morton AB, Ahn B, Smuder AJ. Redox control of skeletal muscle atrophy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;98:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin Z, El-Deiry WS. Overview of cell death signaling pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4(2):139–163. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.2.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng SY, Wang SC, Lei M, Wang Z, Xiong K. Regulatory role of calpain in neuronal death. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13(3):556–562. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.228762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torigoe K, Tanaka HF, Takahashi A, Awaya A, Hashimoto K. Basic behavior of migratory Schwann cells in peripheral nerve regeneration. Exp Neurol. 1996;137(2):301–308. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karalaki M, Fili S, Philippou A, Koutsilieris M. Muscle regeneration: cellular and molecular events. In Vivo. 2009;23(5):779–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallinga W, Meijer SL, Alberink MJ, Vliek M, Wienk ED, Ypey DL. Modelling action potentials and membrane currents of mammalian skeletal muscle fibres in coherence with potassium concentration changes in the T-tubular system. Eur Biophys J. 1999;28(4):317–329. doi: 10.1007/s002490050214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ownby CL, Cameron D, Tu AT. Isolation of myotoxic component from rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis viridis) venom. Electron microscopic analysis of muscle damage. Am J Pathol. 1976;85(1):149–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Habermann E. Bee and wasp venoms. Science. 1972;177(4046):314–322. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4046.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris JB, Cullen MJ. Muscle necrosis caused by snake venoms and toxins. Electron Microsc Rev. 1990;3(2):183–211. doi: 10.1016/0892-0354(90)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhoelan BS, Stevering CH, van der Boog AT, van der Heyden MA. Barium toxicity and the role of the potassium inward rectifier current. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014;52(6):584–593. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.923903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.López JR, Rojas B, Gonzalez MA, Terzic A. Myoplasmic Ca2+ concentration during exertional rhabdomyolysis. Lancet. 1995;345(8947):424–425. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trewby PN, Rutter MD, Earl UM, Sattar MA. Teapot myositis. Lancet. 1998;351(9111):1248. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)01294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flucher BE. How is SR calcium release in muscle modulated by PIP (4,5)2? J Gen Physiol. 2015;145(5):361–364. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201511395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Howell SL, Tyhurst M. Barium accumulation in rat pancreatic B cells. J Cell Sci. 1976;22(2):455–465. doi: 10.1242/jcs.22.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Powers SK, Wiggs MP, Duarte JA, Zergeroglu AM, Demirel HA. Mitochondrial signaling contributes to disuse muscle atrophy. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(1):E31–E39. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00609.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.VanTeeffelen JW, Segal SS. Effect of motor unit recruitment on functional vasodilatation in hamster retractor muscle. J Physiol. 2000;524(Pt 1):267–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Mier P, Lichtman J. Regenerating muscle fibers induce directional sprouting from nearby nerve terminals: studies in living mice. J Neurosci. 1994;14(9):5672–5686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05672.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo L, O'Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:127–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Girouard MP, Bueno M, Julian V, Drake S, Byrne AB, Fournier AE. The molecular interplay between axon degeneration and regeneration. Dev Neurobiol. 2018;78(10):978–990. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Liu NM, Wang Y, Youn JY, Cai H. Endothelial cell calpain as a critical modulator of angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol basis Dis. 2017;1863(6):1326–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tidball JG. Regulation of muscle growth and regeneration by the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(3):165–178. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Satellite cells are spared from BaCl2-induced death in vitro. Treatment with BaCl2 in vivo is used to induce myofiber damage leading to satellite cell activation and muscle regeneration. To formally demonstrate the differential effects of BaCl2 on myofibers and their associated satellite cells, we isolated single muscle fibers from the EDL muscle and exposed them to either saline or 1.2% BaCl2 in the presence of propidium iodide (PI) to label nuclei with disrupted laminae (dead or dying). Fibers were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde then stained for expression of the satellite cell marker CD34 (rat monoclonal RAM-34, eBioscience at 1:200) (arrows). Myofibers fixed at 0 min (A) or after 50 min in Ca2+, Mg2+-free PBS (B) retain their morphology and integrity and do not incorporate PI in either satellite cell nuclei or myonuclei. In contrast, myofibers exposed to 1.2% BaCl2 for 50 min (C) have hypercontracted, lost their structural integrity, and possess PI-labeled nuclei. However, satellite cells associated with these fibers have not incorporated PI. D, Addition of 1.2% BaCl2 to isolated single fibers leads to elevated [Ca2+]i as observed in whole-muscle preparations (Fig. 2). The severity and kinetics of BaCl2-induced myotoxicity for single fibers appear to be less than observed in our experiments using whole muscles. We hypothesize that the absence of fixed attachments at the ends of single myofibers may reduce the damaging membrane stress following Ca2+-induced hypercontraction. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Materials used in this study are commercially available.