Abstract

The divergence of sexual signals is ultimately a coevolutionary process: while signals and preferences diverge between lineages, they must remain coordinated within lineages for matings to occur. Divergence in sexual signals makes a major contribution to evolving species barriers. Therefore, the genetic architecture underlying signal–preference coevolution is essential to understanding speciation but remains largely unknown. In Laupala crickets where male song pulse rate and female pulse rate preferences have coevolved repeatedly and rapidly, we tested two contrasting hypotheses for the genetic architecture underlying signal–preference coevolution: linkage disequilibrium between unlinked loci and genetic coupling (linkage disequilibrium resulting from pleiotropy of a shared locus or tight physical linkage). Through selective introgression and quantitative trait locus (QTL) fine mapping, we estimated the location of QTL underlying interspecific variation in both female preference and male pulse rate from the same mapping populations. Remarkably, map estimates of the pulse rate and preference loci are as close as 0.06 cM apart, the strongest evidence to date for genetic coupling between signal and preference loci. As the second pair of colocalizing signal and preference loci in the Laupala genome, our finding supports an intriguing pattern, pointing to a major role for genetic coupling in the quantitative evolution of a reproductive barrier and rapid speciation in Laupala. Owing to its effect on suppressing recombination, a coupled, quantitative genetic architecture offers a powerful and parsimonious genetic mechanism for signal–preference coevolution and the establishment of positive genetic covariance on which the Fisherian runaway process of sexual selection relies.

Keywords: reproductive isolation, behavioural barrier, mating preference, genetic architecture, pleiotropy, Laupala

1. Introduction

From the courtship dances of birds of paradise to the songs of crickets, species commonly differ in courtship behaviours [1–3]. Because variation in sexual signals and the associated preferential responses can ultimately give rise to reproductive barriers between species, the divergence of sexual signalling systems may be a potent driving force of speciation [3–5]. Divergence of sexual signalling systems often entails the coevolution of signals and preferences within a lineage because they are functionally constrained to maintain effective communication [6,7]. What genetic architecture facilitates signal–preference coevolution? Because response to selection depends on the underlying genetics, the answer to this question is indispensible to understanding the evolution of sexual signalling systems and speciation.

Two contrasting hypotheses for the genetic architecture underlying signal–preference coevolution have been proposed. The first hypothesis posits that genetic variation in sexual traits and preferences is caused by unlinked loci. Coevolution is mediated through preferential mating that results in linkage disequilibrium between the trait and preference alleles over time [8,9]. By contrast, the second hypothesis proposes that genetic coupling (a shared, pleiotropic locus or tightly linked sexual trait and preference loci) underlies variation in both sexual traits and preferences [10–14]. Particularly under pleiotropy, genetic covariance is realized by mutations that affect both traits simultaneously, enhancing the efficacy of divergent selection on the communication system. Under both pleiotropy and tight physical linkage, divergent signal–preference systems are resistant to the homogenizing effects of gene flow when species hybridize because recombination between signal and preference alleles is suppressed. By contrast, under the first hypothesis, recombination can decrease the genetic covariance between unlinked signal and preference loci and even reverse speciation. The two genetic architectures, thus, may differ in their potency in promoting and maintaining speciation.

Theoretical models of sexual selection often assume that signal and preference loci are unlinked and that a positive genetic correlation between these traits arises through assortative mating [15–22]. Indeed, genetic mapping studies have provided support for the hypothesis of unlinked loci in chemical, acoustic and visual signalling modalities [23–25]. By contrast, genetic coupling is often considered unlikely [19]. However, recent evidence from quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping and introgression studies supports the presence of colocalized genes underlying interspecific signal–preference variation in crickets, butterflies, fruit flies and fish [26–30]. In addition, laboratory-induced mutations that alter both male signals and female preferences in fish and flies [31–33] demonstrate that pleiotropic alleles underlying signals and preferences do exist in the genomes of sexual organisms.

The Hawaiian cricket Laupala presents a powerful system to investigate the genetic architecture underlying signal-preference coevolution during divergence in sexual signalling systems. Rapid speciation in this genus has resulted in 38 morphologically and ecologically similar species distinguished by marked differences in acoustic behaviours [34]. Both male song and female acoustic preference have diverged repeatedly between, but remain coordinated within, species [34–37]. Like most crickets, Laupala males sing rhythmic songs that attract females [7,38]. Moreover, female preference for the salient feature, pulse rate, can be studied in computer playback experiments, wherein females indicate preferences by phonotaxis (i.e. orienting and walking towards the preferred song). Thus, female preference for pulse rate can be easily isolated and measured. In addition, variation in acoustic behaviours both within and between species is quantitative [29,36,37], exemplifying a common form of trait evolution in natural systems. Finally, acoustically distinct species of Laupala can be hybridized, allowing the genetic analysis of natural variation in acoustic behaviour.

In support of the genetic coupling hypothesis, a previous study of the fast singing Laupala kohalensis (pulse rate 3.72 pulses per second, pps) and the slow singing L. paranigra (pulse rate 0.71 pps) demonstrated a shared QTL underlying song and preference variation on linkage group one (LG1) [29]. These colocalized loci explain approximately 9% and 15% of the species difference in pulse rate and pulse rate preference, respectively. We subsequently isolated and fine-mapped a song QTL on LG5 that explains an additional approximately 11% of the pulse rate difference of this species pair [39]. Marker association studies have predicted the existence of a preference QTL on LG5, yet its location on this linkage group remains unknown [40,41].

Here, we present the remarkable discovery of a second QTL for female acoustic preference, whose map position coincides with the male pulse rate QTL on LG5. This represents the second case of a shared QTL underlying signal-preference coevolution in Laupala. This finding illuminates the process of quantitative evolution in sex-limited traits under sexual selection. Furthermore, our results suggest that genetic coupling in signal–preference communication systems may be more common than previously thought.

2. Methods

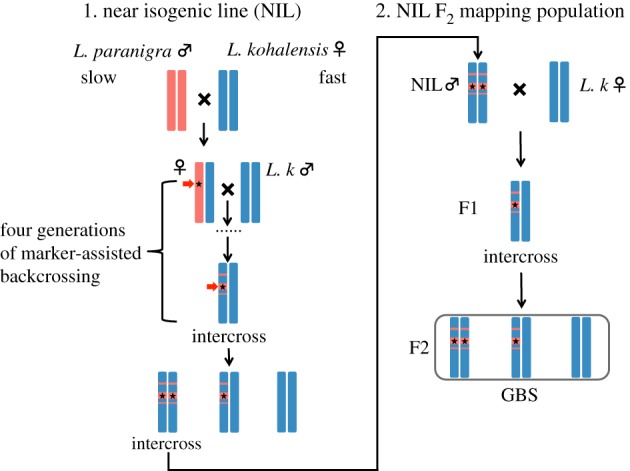

(a). Breeding design

Details of the breeding design have been described in [39]. Briefly, through selective introgression, we isolated and introgressed the largest-effect QTL for the male song pulse rate (QTL4) on LG5 from L. paranigra into the L. kohalensis genome in two independent near isogenic lines (NIL4C and NIL4E; figure 1) [40,43]. NIL males were then backcrossed with L. kohalensis females to generate two F2 mapping families for two NILs (denoted as family 4C.9 and 4E.1; figure 1), from which we phenotyped 89 females and 469 males. All crickets were reared individually in 120 ml specimen cups with a piece of moist tissue and fed ad libitum Organix organic chicken and brown rice dry cat food (Castor & Pollux Natural Petworks, Clackamas, OR, USA) twice per week at 20°C and light cycle at 12 L : 12 D.

Figure 1.

A two-step breeding design for QTL fine mapping of male song pulse rate and female acoustic preference variation between Laupala paranigra (slow singer) and L. kohalensis (fast singer) on linkage group 5 (represented by red and blue bars). In step 1, NILs were created through four generations of marker-assisted backcrossing (see the red arrow) selecting for individuals carrying the L. paranigra allele at the genetic marker linked to QTL4 in Shaw et al. [42] (indicated by the black star) and one generation of intercrossing. Two independent NIL replicates (NIL4C and 4E) were established. In step 2, seventh- to ninth-generation NIL males were backcrossed to L. kohalensis females to generate segregating F2 mapping populations within each NIL replicate. The generation used for genotype-by-sequencing is indicated with GBS. Reproduced with modifications from figure 2 in [39] with permission from the Genetics Society of America.

(b). Male song simulation

We simulated digital songs for female preference trials in LabVIEW v.8.2 [44]. The simulated songs consisted of pulsed sinusoidal tones with characteristics of natural Laupala songs (40 ms pulse duration, 5 kHz carrier frequency; also see electronic supplementary material, methods). In a preference trial, songs played simultaneously from two speakers were calibrated to 90 dB at the cricket release point and 75 cm from the speaker (i.e. at the centre of the phonotaxis tube, see below).

(c). Phenotyping

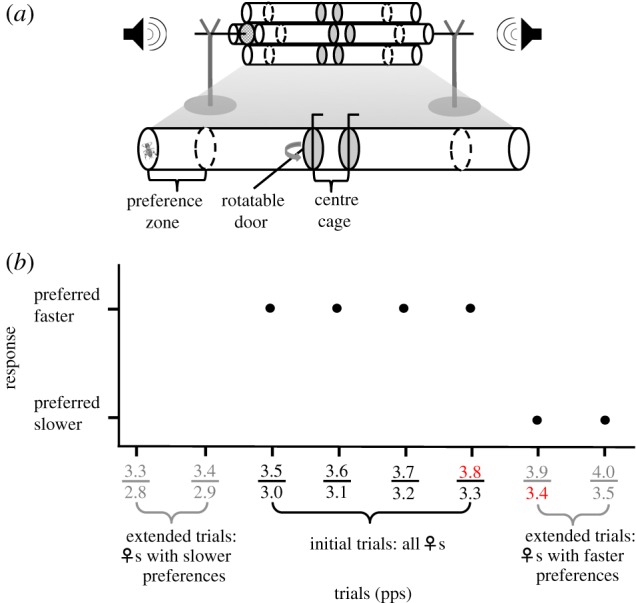

Methods for phenotyping male song pulse rate were reported in [39]. Here, we measured the peak preference for pulse rate from females using repeated, two-choice phonotactic trials. The trials were conducted in custom-made phonotaxis tubes (figure 2a; also see electronic supplementary material, methods) in an RS-243 ETS-Lindgren's sound isolation booth (ETS-Lindgren, Wood Dale, IL, USA) at 20°C.

Figure 2.

(a) Preference trial apparatus. For a detailed description, see electronic supplementary material. The tube below the apparatus is enlarged to show details of a single phonotaxis tube and (b) experimental design of the preference trials, response data from a hypothetical female that goes through four initial trials and two extended trials at the faster end, and inference of peak preference. Pulse rates of the two songs played in a given trial are shown on the x-axis. In the example here, the female shows a switch from preferring the faster to the slower pulse rate between trial 3.3 versus 3.8 pulses per second (pps) and trial 3.4 versus 3.9 pps. The peak preference is, thus, calculated as (3.8 + 3.4)/2 = 3.6 pps.

Each phonotaxis trial consisted of a 5-min pre-trial period and a 10-min testing period. Two simulated songs differing by 0.5 pps, but were otherwise identical, were broadcasted simultaneously during both the pre-trial and testing periods from speakers placed 180° apart (figure 2a). Songs were randomized by the speaker for each trial. During the pre-trial period, the focal female was confined to the central cage. To commence a trial, the doors at both ends of the central cage were opened to connect the cage with the phonotaxis tube. If the focal female entered the preference zone defined as the last 10 cm at each end of the tubes, we scored a preference for the song pulse rate from that speaker.

Each female was tested in a series of trials to estimate peak preference (figure 2b). All females were initially tested in four trials in random order where the pulse rates were 3.2 versus 3.7 pps, 3.3 versus 3.8 pps, 3.4 versus 3.9 pps and 3.5 versus 4.0 pps for 4C.9; and 3.0 versus 3.5 pps, 3.1 versus 3.6 pps, 3.2 versus 3.7 pps and 3.3 versus 3.8 pps for 4E.1. The pulse rate range of the initial four trials was determined by the F1 male pulse rate distribution in each family. If the female response switched from faster pulse rates at the lower end to slower pulse rates at the higher end of the trial range, her peak preference was estimated on the basis of these four trials as the midpoint of the switch from faster to slower pulse rates (figure 2b). If the female showed a consistent response to either faster or slower pulse rates in the initial four trials, she was further tested in extended trials at either the lower (4C.9: 3.0 versus 3.5 pps and 3.1 versus 3.6 pps; 4E.1: 2.8 versus 3.3 pps and 2.9 versus 3.4 pps) or the higher (4C.9: 3.6 versus 4.1 pps and 3.7 versus 4.2 pps; 4E.1: 3.4 versus 3.9 pps and 3.5 versus 4.0 pps) end of the range, depending on the direction of her response in the initial trials (figure 2b). We repeated each trial up to three times for females who failed to respond in a given trial. On any given day, females were tested in not more than two trials, with at least 2 h between the trials. In cases where a female consistently showed a preference for faster or slower pulse rates in all six trials, we estimated the peak preference at the most conservative value (i.e. the midpoint in the next extreme trial, assuming the female would show a switch in her preference).

(d). Genotyping and linkage mapping

Genotyping has been reported in [39]. Briefly, we sequenced F2 individuals using genotyping-by-sequencing [45]. Genotypes of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers were called in each family using the L. kohalensis genome reference as the L. kohalensis parent (whose genotype was denoted as ‘B’); the alternative allele (denoted as ‘A’) was assigned to the NIL parent. We excluded SNPs that deviated significantly from a 1 : 2 : 1 segregation ratio (Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p < 0.05) and/or had a mean depth of coverage less than 20 in each family. Using the resulting SNPs, linkage maps of LG5 for family 4C.9 and 4E.1 have been constructed previously [39] and integrated herein in Joinmap 4 [46]. We kept one SNP marker per 10 kb on the same scaffold. When markers on the same scaffold showed order conflict between the two families, we removed the marker with fewer unique pairwise recombinations until the marker order conflict was resolved.

(e). QTL mapping

QTL mapping for pulse rate in each family was performed previously [39]. Here, we combined data from both families to increase power in QTL mapping of female peak preference on the integrated map. We also remapped the pulse rate QTL using combined data on the integrated map. Individuals with less than 25% missing genotypes were used for QTL mapping. We first tested for a family effect on phenotype using the Welch's t-test. We then performed multiple imputation (IMP) with family as an additive covariate. As a minor-effect QTL for song pulse rate has been detected previously, we also performed multiple QTL mapping (MQM) for both pulse rate and preference in case the existence of other minor-effect QTL affects location and effect size estimation of the focal QTL. Missing genotypes were simulated by 10 000 multiple imputations. Linkage group-wide logarithm of odds (LOD) thresholds were calculated from 1000 permutations at an α level of 0.05. We estimated the effect sizes of a significant QTL by both the final MQM models and by phenotypes at the marker with the highest LOD score. All QTL mapping analyses were conducted in R/qtl v.1.39-5 [47].

Finally, we tested whether the phenotypic distribution of female preference in the combined F2 families deviated from a 1 : 2 : 1 Mendelian segregation ratio with a two-sided χ2-test. To do so, we binned phenotypic data by dividing the range of the phenotypic values evenly in three bins.

3. Results

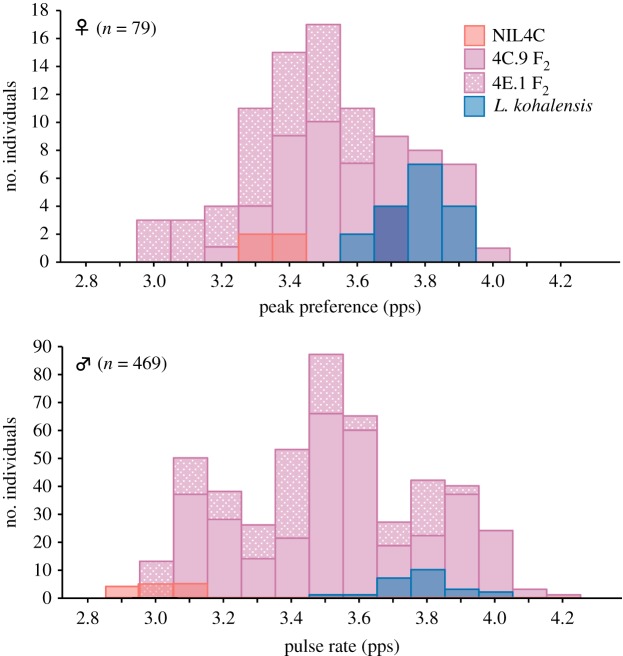

We obtained peak preference measures from 56 and 33 F2 females in 4C.9 and 4E.1, respectively, and 21 females in NIL4C and L. kohaensis lines. As expected, females from the control L. kohalensis line preferred fast pulse rate (3.78 ± 0.10 pps, mean ± s.d., n = 17), and females from a NIL4C preferred slow pulse rate (3.34 ± 0.05 pps, n = 4; figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phenotypic distributions of parental L. kohalensis males and females, near isogenic line 4C (NIL4C), and two F2 mapping families 4C.9 and 4E.1. The histograms for the two F2 families are stacked, and the histograms of parental and F2 individuals are overlapped (i.e. not stacked).

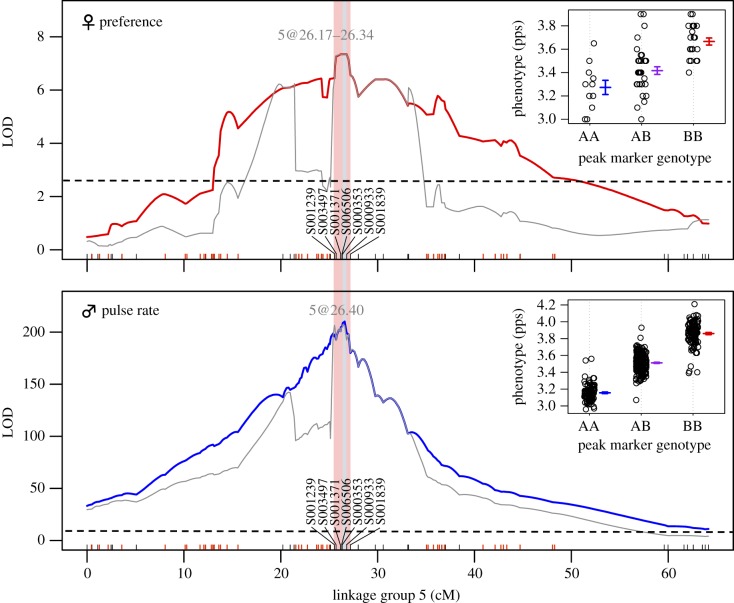

Using IMP, we localized a preference QTL from combined 4C.9 and 4E.1 families that explained 58.8% of F2 variance in female preference to a peak (plateau) in the LOD profile between 26.17 and 26.34 cM (table 1 and figure 4) on the integrated LG5 (electronic supplementary material, results and figure S1). The final MQM model detected a single QTL at the same location (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). The 1.5-LOD confidence interval spanned 2.79 cM (table 1) and included eight SNP markers from seven scaffolds (figure 4). Three markers on scaffold S001371, S006506 and S000353 had the highest LOD score among all markers (figure 4).

Table 1.

Results from MQM for variation in male song pulse rate and female peak preference for pulse rate using combined data from two F2 mapping families. Only results for the major-effect pulse rate QTL are shown in this table.

| trait | sex | sample size | linkage group | QTL location (cM) | LOD score (LOD threshold) | 1.5-LOD confidence interval (cM) | QTL effect size–additive (pps) | % species difference explained | % F2 variance explained |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| preference | female | 71 | 5 | 26.17–26.34 | 7.35 (2.63) | 25.20–27.99 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 4.32 | 58.76 |

| pulse rate | male | 450 | 5 | 26.40 | 207.09 (2.51) | 26.34–26.80 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 10.96 | 85.61 |

Figure 4.

LOD profiles and phenotypic effects of alleles at the markers with the highest LOD score from IMP models for interspecific variation in pulse rate and preference. LOD profiles from IMP models using marker genotypes segregating at a ratio of 1 : 2 : 1 in both families (markers segregating in only one family were treated as missing data and thus simulated in the non-segregating family) are shown in red (female preference) and blue (male pulse rate). LOD profiles from IMP models using all marker genotypes, including those not segregating in one of the two families (obtained from forced SNP call, see electronic supplementary material) are shown in grey. Markers (tick marks on the x-axis) in red indicate those segregating in one of the two families, and markers in black are those segregating in both families (see electronic supplementary material for details). The red- and blue-shaded areas indicate 1.5-LOD confidence intervals for preference and pulse rate QTL, respectively. The scatter plots show individual phenotypes for three genotypes at the marker with the highest LOD score for preference and pulse rate, respectively; the middle horizontal lines are means, and the whiskers are standard errors).

At the markers with the highest LOD score, females with the L. paranigra-origin (AA), the heterozygous and the L. kohalensis-origin (BB) genotypes showed preference for slow (3.27 ± 0.05 pps, mean ± s.e.; figure 4), intermediate (3.42 ± 0.03 pps) and fast pulse rates (3.66 ± 0.04 pps), respectively. The phenotypic effect of a single allele at the preference QTL was largely additive (0.13 ± 0.03 pps), explaining 4.3% of the phenotypic difference between the pure species parents (table 1). Combining 4C.9 and 4E.1, the phenotypic distribution of the female peak preference in the F2 generation was consistent with a 1 : 2 : 1 segregation ratio (bin1 = 21, bin2 = 45, bin3 = 23, χ2 = 0.10, d.f. = 2, p = 0.95; figure 3).

We measured pulse rate from 339 and 130 males in 4C.9 and 4E.1, respectively (published previously in [39]). A major-effect QTL explaining 85.6% F2 variance in pulse rate was localized at 26.40 cM in both IMP and MQM (figure 4; electronic supplementary material, figure S2 and table S1), consistent with previous results [39]. The 1.5-LOD confidence interval of this QTL spanned 0.46 cM (table 1 and figure 4). MQM identified two additional small-effect QTL that explained 1.17% and 0.48% of F2 variance at 5.6 cM and 59.8 cM, respectively (electronic supplementary material, figure S2 and table S1).

Similar to the preference QTL, males with homozygous L. paranigra (AA), heterozygous (AB) and homozygous L. kohalensis genotype (BB) at the marker with the highest LOD score had slow (3.16 ± 0.01 pps), intermediate (3.51 ± 0.01 pps) and fast pulse rates (3.87 ± 0.01 pps; figure 4), respectively. The phenotypic effect of an allele at the pulse rate QTL was almost entirely additive (0.33 ± 0.01 pps), explaining 11.0% of species difference (table 1). The F2 phenotypic distribution of male pulse rate was consistent with a 1 : 2 : 1 segregation ratio (figure 3) as shown previously [39] and did not significantly differ from that of female preference in F2 (χ2 = 2.15, d.f. = 2, p = 0.34).

4. Discussion

Sexual signals and preferences commonly differ between species, reflecting the powerful role of signal and preference divergence in the speciation process [5,48]. While sexual traits routinely diverge, sexual selection likely constrains sexual signals and preferences to remain coordinated during this process. The genetic architecture underlying signal–preference coevolution is central to understanding the complex selective landscape underlying speciation. Signal and preference traits are often modelled with independent hereditary bases where assortative mating alone results in linkage disequilibrium among unlinked loci. Yet, recent findings consistent with a coupled basis to natural variation in signals and preferences in multiple taxa [26–30] suggest a key to understanding signal–preference coevolution. Laupala crickets exemplify these patterns, exhibiting distinctive male songs and female acoustic preferences that have diverged between closely related species in an extremely rapid speciation context [34]. Laupala are further distinct from other systems in that signal and preference are sex-limited traits involved in speciation by sexual selection. Moreover, unlike traits with simple genetic switches, both song and preference are complex, and vary quantitatively, representing a common mode of trait evolution. Laupala, thus, offers the potential for novel insights.

A significant limitation for many quantitative preference phenotypes is the ability to estimate preference in a segregating population. The relatively simple acoustic behaviours in Laupala allowed us to fine map a new female preference QTL on LG5 between the fast singing (and preferring) L. kohalensis and slow singing L. paranigra. We localized the preference QTL on a 0.17 cM wide peak with a 1.5-LOD confidence interval of only 2.8 cM. Our study is one of only three to have mapped the location of preference/mate choice loci with a sufficiently high resolution to rigorously test alternative hypotheses of genetic architecture [26,28]. Moreover, our study is unique among these in that acoustic preference in Laupala is a sex-limited, quantitative trait expressed in the context of sexual selection by female mate choice [34], the leading causal explanation for the evolution of elaborate sexual communication.

Remarkably, we found that the estimated map position of the female preference QTL on LG5 is nearly identical to a male pulse rate QTL with the peaks between only 0.06 (26.40–26.34) and 0.17 (26.40–26.17) cM apart (figure 4). Furthermore, the 1.5-LOD confidence intervals of the preference and song QTL largely overlap (figure 4; electronic supplementary material, figure S2) with the top three LOD scores for preference and song attributed to the same markers. Coincidentally, both preference and song QTL contribute relatively minor to moderate effects in a largely additive way to the differences in acoustic behaviours between the two species (table 1). Equally importantly, the phenotypic effects of pulse rate and preference QTL are in the same direction, required for establishing a positive genetic covariance between pulse rate and preference. Features of genetic architecture such as these can greatly facilitate the coevolution of a signal–preference system, whereby both traits vary in quantitatively small steps in the same direction, enabling coordinated changes despite the divergent phenotypic evolution that must occur during the speciation process [12–14].

The song and preference QTL identified in the present study are the second pair of colocalizing QTL identified in Laupala. We have previously mapped QTL that makes a similarly coupled contribution to pulse rate and preference differences between L. paranigra and L. kohalensis on LG1 [29]. At least eight and four QTL underlie the species difference in pulse rate and preference, respectively, between these species [29,40–42]. The fact that two of the four preference QTL independently coincide with a different pulse rate QTL (the location of the remaining two as yet unknown) suggests a compelling pattern underlying the coevolution of these traits. Moreover, the allelic effect of the two preference QTL and of their colocalizing pulse rate QTL together account for roughly 20% of species difference (table 1 herein; table 1 in [29]). Such a substantial proportion attests to a significant role that genetic coupling plays in sexual signal divergence and speciation in Laupala.

The overlap of the confidence intervals of pulse rate and preference QTL and the extremely close estimates of their peak locations are consistent with a pleiotropic basis to variation in pulse rate and preference. Pleiotropy provides a genetic mechanism whereby positive genetic covariance between signal and preference genes is an immediate consequence of mutations at the locus (or loci for quantitative traits). Alternatively, our results may reflect the genetic architecture of a tightly linked signal–preference gene cluster, akin to a ‘supergene’, an equally exciting explanation that has been repeatedly shown to facilitate the adaptation of complex traits [49–51]. Like pleiotropy, tight physical linkage can facilitate coevolution by effectively suppressing recombination between signal and preference alleles. Distinguishing pleiotropy and tight linkage requires identifying the causal genes and is a logical next step in this system. Recent technological advances place such a goal within reach in non-model systems [52].

Mechanistically, recent findings suggest that shared genes for singing and temporal auditory pattern recognition are plausible. Insect singing by wing movements is controlled by central pattern generators (CPGs) in thoracic and abdominal ganglia [53,54]. In the field cricket, an auditory feature detector circuit that selectively responds to the pulse rate of conspecific song has been identified in the female brain [55]. In this circuit, pulse rate selectivity is achieved via post-inhibitory rebound that offsets direct and delayed line inputs to a coincidence detector neuron by the exact duration of the conspecific pulse period. We suggest that a shared molecular mechanism, for example, the type or number of ion channels or neural projections, may regulate both the oscillation period of the song CPG and the offset duration of the feature detector circuit. Fine mapping and gene annotation [39] identified a promising candidate gene for song variation, the putative Laupala cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel-like gene (Cngl) on scaffold S001371. Here, we show that the highest LOD score for preference also associates with this scaffold. Although unknown in Laupala, Drosophila Cngl is expressed in brain, thoracic ganglia and muscles [56], consistent with the expectation for a causal gene for song and preference variation. Finally, a related group of genes in the same gene superfamily are implicated in both rhythmic muscle contraction [57–60] and temporal coincidence detection and relay in auditory systems [61–63]. Such evidence renders Cngl a candidate pleiotropic gene for further functional validation.

Colocalization of loci for sexual traits and mate choice has been shown in two other high-resolution mapping studies. In the three spine stickleback, the QTL for mate choice and body shape were 14.3 cM apart [26]. In the Heliconius butterflies, a QTL contributing to visual preference is only 1.2 cM from optix, a gene regulating the forewing red band [28], demonstrating genetic coupling underlying variation in wing colouration and visual preference. In both these systems, mating signals or cues are likely magic traits [64] that function in both ecological (foraging or predator avoidance) and mate choice contexts. By contrast, the sexual traits we have studied in Laupala are sex-limited and function primarily in a reproductive context (ecological function of pulse rate or preference for pulse rate has yet to be discovered), representing the widespread process of sexual selection by female choice thought to underlie the evolution of many elaborate and extravagant sexual signalling systems. Intriguingly, the Fisherian runaway process of sexual selection, a primary explanation for the evolution of exaggerated sexual traits, relies on positive genetic covariance between sexual trait and preference [8,19]. Whether such positive genetic covariances exist is debated [65,66], our finding offers a parsimonious and effective genetic mechanism for the establishment and maintenance of positive genetic covariance for the trait pair [19,22,67].

Taken together with the studies above, genetic coupling may transcend communication modality, evolutionary mechanism and taxonomic group (invertebrates or vertebrates) and prove to be of general importance to the divergence of sexual communication systems and speciation. In the light of these emerging empirical findings, theoretical and modelling work has recently begun to explore the effect of pleiotropy and tight physical linkage on the process and consequence of lineage divergence [68,69]. Further empirical and theoretical efforts should be fruitful in deepening our understanding of how divergence in communication systems can spur speciation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ben Weaver, Alex Thomas, Eric Cole, Laura Hernandez, Isabelle Phillipe, Nathan Barr and McKenzie Laws for assistance in cricket rearing, phenotyping and DNA extraction; Cornell Genomic Diversity Facility for advice on molecular procedures; and Aure Bombarely, Thomas Blankers, Linlin Zhang and Cornell BioHPC Lab for assistance in bioinformatics.

Data accessibility

DNA sequences are available at NCBI (accession PRJNA509479). Phenotype and genotype data, as well as bioinformatic, QTL mapping and LabVIEW scripts, can be downloaded at https://github.com/MingziXu/QTL4-colocalization-scripts-and-data.

Authors' contributions

M.X. and K.L.S. designed research, M.X. collected and analysed data, and M.X. and K.L.S. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This project is funded by the National Science Foundation (grant no. 1257682) to K.L.S.

References

- 1.Huber F, Moore TE, Loher W. 1989. Cricket behavior and neurobiology. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laman T, Scholes E. 2012. Birds of paradise: revealing the world's most extraordinary birds. Washington, D. C., USA: National Geographic Books. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uy JAC, Irwin DE, Webster MS. 2018. Behavioral isolation and incipient speciation in birds. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 49, 1–24. ( 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110617-062646) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panhuis TM, Butlin R, Zuk M, Tregenza T. 2001. Sexual selection and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 364–371. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02160-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie MG. 2007. Sexual selection and speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 38, 79–102. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095733) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowler-Finn KD, Rodríguez RL. 2016. The causes of variation in the presence of genetic covariance between sexual traits and preferences. Biol. Rev. 91, 498–510. ( 10.1111/brv.12182) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh KP, Shaw KL. 2013. Multivariate sexual selection in a rapidly evolving speciation phenotype. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20130482 ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.0482) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher RA. 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection: a complete variorum edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lande R. 1984. The genetic correlation between characters maintained by selection, linkage and inbreeding. Genet. Res. 44, 309–320. ( 10.1017/S0016672300026549) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander RD. 1962. Evolutionary change in cricket acoustical communication. Evolution 16, 443–467. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1962.tb03236.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoy RR, Hahn J, Paul RC. 1977. Hybrid cricket auditory behavior: evidence for genetic coupling in animal communication. Science 195, 82–84. ( 10.1126/science.831260) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boake CR. 1991. Coevolution of senders and receivers of sexual signals: genetic coupling and genetic correlations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 6, 225–227. ( 10.1016/0169-5347(91)90027-U) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butlin R, Ritchie M. 1989. Genetic coupling in mate recognition systems: what is the evidence? Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 37, 237–246. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1989.tb01902.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh ND, Shaw KL. 2012. On the scent of pleiotropy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5–6. ( 10.1073/pnas.1118531109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall DW, Kirkpatrick M, West B. 2000. Runaway sexual selection when female preferences are directly selected. Evolution 54, 1862–1869. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb01233.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkpatrick M. 1982. Sexual selection and the evolution of female choice. Evolution 36, 1–12. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1982.tb05003.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkpatrick M. 1985. Evolution of female choice and male parental investment in polygynous species: the demise of the ‘sexy son’. Am. Nat. 125, 788–810. ( 10.1086/284380) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkpatrick M. 1996. Good genes and direct selection in the evolution of mating preferences. Evolution 50, 2125–2140. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb03603.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lande R. 1981. Models of speciation by sexual selection on polygenic traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 78, 3721–3725. ( 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3721) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pomiankowski A. 1987. Sexual selection: the handicap principle does work—sometimes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 231, 123–145. ( 10.1098/rspb.1987.0038) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pomiankowski A, Iwasa Y. 1993. Evolution of multiple sexual preferences by Fisher's runaway process of sexual selection. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 253, 173–181. ( 10.1098/rspb.1993.0099) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pomiankowski A, Iwasa Y, Nee S. 1991. The evolution of costly mate preferences I. Fisher and biased mutation. Evolution 45, 1422–1430. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb02645.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dopman EB, Bogdanowicz SM, Harrison RG. 2004. Genetic mapping of sexual isolation between E and Z pheromone strains of the European corn borer (Ostrinia nubilalis). Genetics 167, 301–309. ( 10.1534/genetics.167.1.301) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Limousin D, Streiff R, Courtois B, Dupuy V, Alem S, Greenfield MD. 2012. Genetic architecture of sexual selection: QTL mapping of male song and female receiver traits in an acoustic moth. PLoS ONE 7, e44554 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0044554) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merrill RM, Van Schooten B, Scott JA, Jiggins CD.. 2011. Pervasive genetic associations between traits causing reproductive isolation in Heliconius butterflies. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 511–518. ( 10.1098/rspb.2010.1493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bay RA, et al. 2017. Genetic coupling of female mate choice with polygenic ecological divergence facilitates stickleback speciation. Curr. Biol. 27, 3344– 3349.e4 ( 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.037) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kronforst MR, Young LG, Kapan DD, McNeely C, O'Neill RJ, Gilbert LE. 2006. Linkage of butterfly mate preference and wing color preference cue at the genomic location of wingless. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6575–6580. ( 10.1073/pnas.0509685103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrill RM, Rastas P, Martin SH, Melo MC, Barker S, Davey J, McMillan WO, Jiggins CD. 2019. Genetic dissection of assortative mating behavior. PLoS Biol. 17, e2005902 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005902) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw KL, Lesnick SC. 2009. Genomic linkage of male song and female acoustic preference QTL underlying a rapid species radiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9737–9742. ( 10.1073/pnas.0900229106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNiven VTK, Moehring AJ. 2013. Identification of genetically linked female preference and male trait. Evolution 67, 2155–2165. ( 10.1111/evo.12096) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukamachi S, Kinoshita M, Aizawa K, Oda S, Meyer A, Mitani H. 2009. Dual control by a single gene of secondary sexual characters and mating preferences in medaka. BMC Biol. 7, 64 ( 10.1186/1741-7007-7-64) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gumm JM, Snekser JL, Iovine MK. 2009. Fin-mutant female zebrafish (Danio rerio) exhibit differences in association preferences for male fin length. Behav. Process. 80, 35–38. ( 10.1016/j.beproc.2008.09.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcillac F, Grosjean Y, Ferveur J-F. 2005. A single mutation alters production and discrimination of Drosophila sex pheromones. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 303–309. ( 10.1098/rspb.2004.2971) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendelson TC, Shaw KL. 2005. Sexual behaviour: rapid speciation in an arthropod. Nature 433, 375 ( 10.1038/433375a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otte D. 1994. The crickets of Hawaii: origin, systematics and evolution. Philadelphia: The Orthopterists' Society, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw KL. 1996. Polygenic inheritance of a behavioral phenotype: interspecific genetics of song in the Hawaiian cricket genus Laupala. Evolution 50, 256–266. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb04489.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw KL. 2000. Interspecific genetics of mate recognition: inheritance of female acoustic preference in Hawaiian crickets. Evolution 54, 1303–1312. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00563.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw KL, Herlihy DP. 2000. Acoustic preference functions and song variability in the Hawaiian cricket Laupala cerasina. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267, 577–584. ( 10.1098/rspb.2000.1040) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu M, Shaw KL. 2019. The genetics of mating song evolution underlying rapid speciation: linking quantitative variation to candidate genes for behavioral isolation. Genetics 211, 1089–1104. ( 10.1534/genetics.118.301706) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiley C, Ellison CK, Shaw KL. 2011. Widespread genetic linkage of mating signals and preferences in the Hawaiian cricket Laupala. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 1203–1209. ( 10.1098/rspb.2011.1740) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiley C, Shaw KL. 2010. Multiple genetic linkages between female preference and male signal in rapidly speciating Hawaiian crickets. Evolution 64, 2238–2245. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01007.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw KL, Parsons YM, Lesnick SC. 2007. QTL analysis of a rapidly evolving speciation phenotype in the Hawaiian cricket Laupala. Mol. Ecol. 16, 2879–2892. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03321.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellison CK, Shaw KL. 2013. Additive genetic architecture underlying a rapidly evolving sexual signaling phenotype in the Hawaiian cricket genus Laupala. Behav. Genet. 43, 445–454. ( 10.1007/s10519-013-9601-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elliott C, Vijayakumar V, Zink W, Hansen R. 2007. National instruments LabVIEW: a programming environment for laboratory automation and measurement. J. Assoc. Lab. Autom. 12, 17–24. ( 10.1016/j.jala.2006.07.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elshire RJ, Glaubitz JC, Sun Q, Poland JA, Kawamoto K, Buckler ES, Mitchell SE. 2011. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. PLoS ONE 6, e19379 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0019379) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Ooijen J. 2006. Software for the calculation of genetic linkage maps in experimental populations. Wageningen, the Netherlands: Kyazma BV. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broman KW, Wu H, Churchill GA, Sen Ś. 2003. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics 19, 889–890. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Doorn GS, Dieckmann U, Weissing FJ.. 2004. Sympatric speciation by sexual selection: a critical reevaluation. Am. Nat. 163, 709–725. ( 10.1086/383619) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lamichhaney S, et al. 2016. Structural genomic changes underlie alternative reproductive strategies in the ruff (Philomachus pugnax). Nat. Genet. 48, 84 ( 10.1038/ng.3430) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwander T, Libbrecht R, Keller L. 2014. Supergenes and complex phenotypes. Curr. Biol. 24, R288–R294. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuttle EM, et al. 2016. Divergence and functional degradation of a sex chromosome-like supergene. Curr. Biol. 26, 344–350. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.069) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. 2014. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096 ( 10.1126/science.1258096) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schöneich S, Hedwig B. 2017. Neurons and networks underlying singing behaviour. In The cricket as a model organism, pp. 141–153. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 54.von Philipsborn AC, Liu T, Jai YY, Masser C, Bidaye SS, Dickson B.. 2011. Neuronal control of Drosophila courtship song. Neuron 69, 509–522. ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schöneich S, Kostarakos K, Hedwig B. 2015. An auditory feature detection circuit for sound pattern recognition. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500325 ( 10.1126/sciadv.1500325) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyazu M, Tanimura T, Sokabe M. 2000. Molecular cloning and characterization of a putative cyclic nucleotide-gated channel from Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol. Biol. 9, 283–292. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00186.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu L, Selverston AI, Ayers J. 2016. Role of Ih in differentiating the dynamics of the gastric and pyloric neurons in the stomatogastric ganglion of the lobster, Homarus americanus. J. Neurophysiol. 115, 2434–2445. ( 10.1152/jn.00737.2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calabrese RL, Norris BJ, Wenning A. 2016. The neural control of heartbeat in invertebrates. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 41, 68–77. ( 10.1016/j.conb.2016.08.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Herrmann S, Schnorr S, Ludwig A. 2015. HCN channels—modulators of cardiac and neuronal excitability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 1429–1447. ( 10.3390/ijms16011429) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thoby-Brisson M, Telgkamp P, Ramirez J-M. 2000. The role of the hyperpolarization-activated current in modulating rhythmic activity in the isolated respiratory network of mice. J. Neurosci. 20, 2994–3005. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02994.2000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oertel D, Bal R, Gardner SM, Smith PH, Joris PX. 2000. Detection of synchrony in the activity of auditory nerve fibers by octopus cells of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 11 773–11 779. ( 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11773) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamada R, Kuba H, Ishii TM, Ohmori H. 2005. Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels regulate auditory coincidence detection in nucleus laminaris of the chick. J. Neurosci. 25, 8867–8877. ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-05.2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Forsythe ID. 2018. Integration of synaptic and intrinsic conductances shapes microcircuits in the superior olivary complex. In The mammalian auditory pathways, pp. 101–126. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gavrilets S. 2004. Fitness landscapes and the origin of species. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Greenfield MD, Alem S, Limousin D, Bailey NW. 2014. The dilemma of Fisherian sexual selection: mate choice for indirect benefits despite rarity and overall weakness of trait-preference genetic correlation. Evolution 68, 3524–3536. ( 10.1111/evo.12542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roff DA, Fairbairn DJ. 2014. The evolution of phenotypes and genetic parameters under preferential mating. Ecol. Evol. 4, 2759–2776. ( 10.1002/ece3.1130) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fisher RA. 1915. The evolution of sexual preference. Eugen. Rev. 7, 184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kopp M, et al. 2018. Mechanisms of assortative mating in speciation with gene flow: connecting theory and empirical research. Am. Nat. 191, 1–20. ( 10.1086/694889) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Servedio MR, Bürger R. 2018. The effects on parapatric divergence of linkage between preference and trait loci versus pleiotropy. Genes 9, 217 ( 10.3390/genes9040217) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

DNA sequences are available at NCBI (accession PRJNA509479). Phenotype and genotype data, as well as bioinformatic, QTL mapping and LabVIEW scripts, can be downloaded at https://github.com/MingziXu/QTL4-colocalization-scripts-and-data.