Vaginal lubricants are widely used both in-clinic and for personal use. Here, we employed monolayer and 3-dimensional vaginal epithelial cell models to show that select hyperosmolar lubricants induce cytotoxicity, reduce cell viability, and alter barrier and inflammatory targets.

Keywords: vaginal lubricants, genital inflammation, nonoxynol-9, 3-D cell culture, human vaginal epithelial cells, cytotoxicity, inflammatory mediators

Abstract

Background

A majority of US women report past use of vaginal lubricants to enhance the ease and comfort of intimate sexual activities. Lubricants are also administered frequently in clinical practice. We sought to investigate if hyperosmolar lubricants are toxic to the vaginal mucosal epithelia.

Methods

We tested a panel of commercially available lubricants across a range of osmolalities in human monolayer vaginal epithelial cell (VEC) culture and a robust 3-dimensional (3-D) VEC model. The impact of each lubricant on cellular morphology, cytotoxicity, barrier targets, and the induction of inflammatory mediators was examined. Conceptrol, containing nonoxynol-9, was used as a cytotoxicity control.

Results

We observed a loss of intercellular connections, and condensation of chromatin, with increasing lubricant osmolality. EZ Jelly, K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, and Conceptrol induced cytotoxicity in both models at 24 hours. There was a strong positive correlation (r = 0.7326) between lubricant osmolality and cytotoxicity in monolayer VECs, and cell viability was reduced in VECs exposed to all the lubricants tested for 24 hours, except McKesson. Notably, select lubricants altered cell viability, barrier targets, and inflammatory mediators in 3-D VECs.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that hyperosmolar lubricants alter VEC morphology and are selectively cytotoxic, inflammatory, and barrier disrupting in the 3-D VEC model.

Vaginal lubricants are commonly used in sexual practices and are often utilized by postmenopausal women [1–6]. The symptoms of vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and vulvovaginal pain that accompany the genitourinary syndrome of menopause affects approximately 50% of postmenopausal women, and the first line of treatment is nonhormonal vaginal lubricants [7]. In addition, lubricants are regularly used for office-based clinical examinations, including digital exams, pelvic exams, and transvaginal ultrasound, and obstetric practitioners frequently apply lubricants during pregnancy and labor.

A robust vaginal mucosal barrier is essential to vaginal health and is colonized by healthy vaginal microbiota, including high abundance of Lactobacillus species, which provide protection to pathogenic infections by producing lactic acid and maintaining a low pH [8]. A vaginal microbiota that has low abundance of Lactobacillus species, clinically defined as bacterial vaginosis, has been consistently associated with increased risk to a number of sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [9, 10]. Several epidemiologic studies suggest that lubricants adversely affect the vaginal microbiota and are associated with bacterial vaginosis states [2, 4, 11–14]. Lubricants may directly disturb the vaginal ecosystem because they are markedly hypertonic to mucosal epithelia and contain antimicrobial preservatives, such as chlorhexidine gluconate. A compromised vaginal epithelial cell (VEC) barrier, through dysregulation of important structural proteins, also increases the risk of the attachment and entry of potentially harmful organisms within the vagina. Recent in vitro studies have begun to document vaginal lubricants’ detrimental effects on sperm motility, chromatin integrity, and epithelial barrier properties [15, 16].

Spermicides have been similarly investigated as they contain the active ingredient nonoxynol-9 (N-9), which was found to disrupt the VEC barrier and increase the transmission of HIV type 1 in a cohort of female sex workers who used N-9 frequently [17–19]. In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that vaginal lubricants remain under 1200 mOsm/kg, have a pH of 4.5, and that ingredients such as polyquaternium-15 and N-9 be avoided due to their significant irritant effects [20]. Polyquaternium-15 is a formaldehyde-releasing preservative previously found to increase HIV replication rates in vitro [21]. Despite these recommendations, the majority of over-the-counter vaginal lubricants available remain hyperosmolar and contain some of the named toxic ingredients.

Lubricants intended for clinical use are classified by the US Food and Drug Administration as class I/class II medical devices and are not required to enter human safety trials. Currently, the safety testing of these lubricants utilizes the rabbit vaginal irritation model [22]. No current animal model system accurately reflects the human vaginal microenvironment [23] and, as with all model systems, the rabbit vaginal irritation model has its limitations. For example, the rabbit vaginal mucosa displays a more neutral pH of around 7, a non-Lactobacillus-dominant microbiota, and has a different vaginal epithelial tissue structure and cell morphology to that of humans [24–27]. To extend the cytotoxicity testing of vaginal lubricants, existing animal models could potentially be used in combination with human VEC in vitro models [23, 28–30]. Here, we screened a panel of both personal and clinically utilized vaginal lubricants at a range of osmolalities, including a N-9–containing product, to reflect products currently available on the market. We aimed to study their effect on VEC cytotoxicity, viability, cell membrane integrity, and morphology, as well as inflammatory mediator and barrier target secretion levels in vitro, by employing monolayer (ML) VECs and a robust 3-dimensional (3-D) VEC culture model, which recapitulates the stratified squamous vaginal epithelium [23, 28].

METHODS

Generation of 3-D Human VEC Aggregates, Cell Culture, and Viable Cell Count

Human vaginal epithelial (V19I) cells were cultured in 1:1 (vol/vol) of Epilife/Keratinocyte Serum-Free Media (Life Technologies) as previously described [28]. V19I cells were cultured as monolayers (ML VECs) at 37°C in 5% carbon dioxide (CO2), prior to seeding in a rotating wall vessel bioreactor with collagen-coated dextran microcarrier beads as previously published [28, 30]. Once fully differentiated at 28 days, cells were quantified using a Countess automated cell counter and Trypan blue exclusion (0.25%; vol/vol). VEC aggregates (3-D VECs) were divided into 24- and 48-well tissue culture–treated plates for downstream assays at a density of 1–5 × 105 cells/mL.

Lubricant Treatment Preparation and Osmolality

Selected lubricants used in this study are listed in Table 1 and some lots varied through the course of testing. Osmolality measurements were made using a membrane osmometer (Carolina Biological Supply Company). Lubricants were diluted 100-fold with distilled water, and measured osmotic pressures (mm/minute) were converted to mOsm by comparison with standard glucose solutions of known concentrations. Under aseptic conditions, lubricants for treatment were diluted at 1:10 (vol/vol) preparations in the V19I cell media using a blunt pipette tip, unless otherwise stated. Due to the viscosity of the lubricant formulations, a 1:10 treatment in cell media was selected from tested dilution factors, to properly evaluate in the context of human VEC models.

Table 1.

Key Properties of Selected Commercial Clinical and Personal Lubricants

| Lubricant | Osmolality, mOsm/kg | Lubricant pH | Manufacturer | Ingredients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good Clean Love Almost Nakeda | 270 [31] | 4.8 [32] | Good Clean Love Inc | Organic aloe barbadensis leaf juice, xanthan gum, agar, potassium sorbate, sodium benzoate, sodium lactate, lactic acid, natural flavors |

| McKesson Lubricant | 2125b | 5.6–6.7c | McKesson Medical- Surgical Inc | Water, glycerin, sodium hydroxide, carbomer 140G, polyethylene glycol, propylparaben, methylparaben |

| EZ Jelly | 2243b | 5.0–6.0c | Athena Medical Products | Water, glycerin, carbomer, sodium hydroxide, PEG-150, methylparaben, propylparaben |

| K-Y Jelly | 2500 [31] | 4.55 [20] | Reckitt Benckiser Group plc | Water, glycerin, hydroxyethylcellulose, chlorhexidine gluconate, gluconolactone, methylparaben, sodium hydroxide |

| Astroglide Liquid | 6100 [31] | 4.44 [20] | BioFilm Inc | Purified water, glycerin, propylene glycol, polyquaternium 15d, methylparaben, propylparaben |

| K-Y Warming Jelly | 10 300 [31] | 4.5–6.5 [20] | Reckitt Benckiser Group plc | Propylene glycol, PEG-8, hydroxypropyl cellulose, tocopherol |

| Conceptrol (N-9 4%) | 1257 [33] | 4.5 [33] | Caldwell Consumer Health LLC | Nonoxynol-9 (4%)d, lactic acid, methylparaben, povidone, propylene glycol, purified water, sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, sorbic acid, sorbitol solution |

aLubricant formulation adheres to 2012 World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

bMeasured by osmometer and reported herein.

cLubricant osmolality and pH range values taken from manufacturer website/product specifications.

dIngredient not recommended in lubricant formulations by 2012 WHO guidelines.

Crystal Violet Staining for VEC Morphology

Cell morphology was visualized using crystal violet stain (Sigma-Aldrich) (in 10%–30% ethanol). Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at 2.5 × 104 (cells/well) and grown overnight (37°C, 5% CO2). Adhered cells were stained with 100 μL of crystal violet solution for 3 minutes, washed with distilled water, dried, and imaged using bright-field microscopy (Olympus, IX2-SP). Cellular density was quantified using Fiji (ImageJ). Images were converted to 8-bit and processed to remove background staining. Thresholds were adjusted to select for stained cells and particles analyzed to quantify the area stained (%).

MTT Assay for Cell Proliferation

Cells were seeded in a 96-well format and treated with the selected lubricants for 24 hours. MTT [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide] (AMRESCO) stock was prepared and added to wells as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at 570 nm (reference 650 nm) was recorded using the Tecan Safire II Multi-Mode Plate reader (Tecan). Percentage viability was calculated as (sample absorbance – media background absorbance) / (control absorbance – media background absorbance) × 100.

Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay for VEC Cytotoxicity

Monolayer VECs were seeded and treated for 4 hours and 24 hours with lubricants in a 96-well plate as above, and 3-D VECs were cultured as above and distributed to a 48-well plate. Supernatants were collected and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured in 1:5 dilution of supernatant using the Pierce LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Confocal Staining and Imaging

Glass coverslips were seeded with VECs in a 6-well plate at 2 × 105 cells per slide. Cells were treated with lubricants at 1:10 for 24 hours, rinsed twice in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature. Fixed cells were labeled with 10 μg/mL of wheat germ agglutinin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 633 (ThermoFisher), to visualize the cellular membrane. VECs were stained for 1 hour at 4°C in the dark, rinsed twice with DPBS, and mounted in ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Invitrogen). Slides were stored in the dark at 4°C, imaged at ×63 using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope, and analyzed using Zeiss Zen 2009 LE Software platform. Settings for all imaging were set according to the unstained and untreated sample at each magnification.

Bio-Plex Analysis of Cytokines and Barrier Targets

Supernatants from 1:10 lubricant-treated 3-D VECs were collected at 24 hours from 3 independent experiments. Levels of 17 protein targets were measured by cytometric bead array analysis using a R&D Systems Human Magnetic Luminex Assay (C-C motif chemokine ligand 20 [CCL20], extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer [EMMPRIN], Fas, macrophage migration inhibitory factor [MIF], mucin 1 [MUC1], and mucin 16 [MUC16]), a Milliplex MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead Panel (interleukin [IL] 1α, IL-1 receptor antagonist [IL-1RA], IL-6, IL-8, interferon γ–induced protein 10 [IP-10], and regulated on activation, normal expressed and secreted protein [RANTES/CCL5]) and a Milliplex MAP Human Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) Magnetic Bead Panel 2 (MMP-1, -2, -7, -9, and -10). The assays were performed in accordance with the manufacturers’ protocols, on the Bio-Plex200 system and analyzed using the Bio-Plex 5.0 Manager Software (Bio-Rad). All samples were assayed in duplicate. A 5-parameter logistic regression curve fit was used to determine concentrations. Concentration values below the detection limit were substituted with 0.5 of the minimum detectable concentration. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using ClustVis [34]. Three biological replicates from independent experiments were averaged and log2-transformed to normalize the data. Values for each target were mean centered and variance scaled. Clustering of the heat map was based on Euclidean distance between rows and columns and average linkage cluster algorithm.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using Prism 7 software (GraphPad), and statistical significance was tested for LDH and MTT data using a one-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. Due to untreated samples being at baseline LDH cytotoxicity or set as 100% cell viability in the MTT assay, one-tailed analysis was conducted to compare lubricant samples to untreated VECs. Pearson correlation coefficient analysis was conducted on ML LDH vs osmolality and 3-D LDH vs viability data. Analysis was conducted on data from at least 3 independent experiments for LDH and MTT and displayed as mean with standard error of the mean. Significance of protein induction levels as compared to untreated was conducted on log2-transformed data using one-way analysis of variance. Results with a P value ≤.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Hyperosmolar Lubricants Alter ML VEC Morphology and Cell Membrane Integrity In Vitro

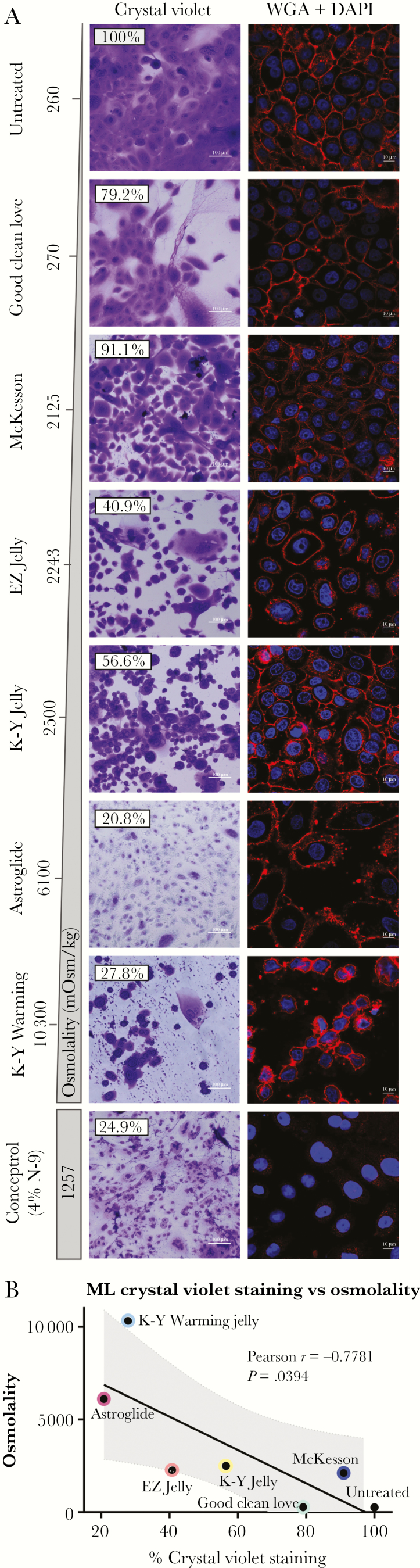

VEC morphology was visualized by crystal violet staining following treatment with a panel of vaginal lubricants (Table 1). Normal, untreated cells produced a healthy, confluent cellular layer with consistent ratios of cytoplasm to nuclear material and a healthy honeycomb structure, indicative of tight intercellular connections. After treatment with selected lubricants at 24 hours, a trend of decreased cellular integrity and density with increased osmolality (Osm) was observed. Good Clean Love (Osm 270, Table 1) and McKesson (Osm 2125) did not significantly alter cell morphology of ML VECs, with largely intact, healthy cells observed at 24 hours (Figure 1A). Good Clean Love was noted to be extremely viscous and remained on cells postwashing, resulting in background crystal violet staining of the lubricant; however, no morphological changes were observed. EZ Jelly (Osm 2243) and K-Y Jelly (Osm 2500) had higher osmolalities and correlated with the rounding up of cells and a general loss of intercellular connections. Stressed cells were observed after treatment with EZ Jelly and K-Y Jelly, due to the elongation and stretching of the cellular membranes and loss of intercellular junctions. Compounds with higher osmolality (Astroglide [Osm 6100], K-Y Warming Jelly [Osm 13 000]) and Conceptrol containing the detergent N-9 (Osm 1257) caused higher levels of damage as evidenced by cellular debris and ruptured cells. Correlation analysis demonstrated a negative relationship between lubricant osmolality and crystal violet staining (r = –0.7781, P = .0394) (Figure 1B). Chromatin condensation was observed after confocal staining with DAPI, in K-Y Warming– and N-9–treated cells. These data indicate a strong negative correlation between vaginal lubricant osmolality and vaginal epithelial cell integrity, indicating that higher osmolality lubricant formulations cause cellular stress and altered cell membrane structure.

Figure 1.

Exposure to hyperosmolar lubricants induces changes in cellular morphology, chromatin condensation, and loss of intercellular junctions in monolayer vaginal epithelial cells (ML VECs). ML VECs were treated with a 1:10 dilution of vaginal lubricants in cell media for 24 hours. A, Changes in cellular morphology were observed via crystal violet staining, using a ×20 brightfield objective lens to visualize. Untreated VECs are shown on the top left, and lubricant treatment groups are shown from top to bottom in increasing osmolality. Conceptrol, which contains nonoxynol-9 (N-9), was placed at the bottom as the positive control for cytotoxicity. Cellular staining density (%) can be observed at the top left of each image, quantified using Fiji (ImageJ). ML VECs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Visualization of glycoconjugates, ie, N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylneuraminic acid (sialic acid) residues, on the cellular membrane of ML VECs was determined after staining with 10 μg/mL of wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 633. Nuclear material was stained using 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and cells were imaged by confocal microscopy at ×63 original magnification. Images were taken at the middle plane of ML VECs to highlight the cellular morphology as it relates to crystal violet images. All images were collected with the same settings. B, Fiji (ImageJ) was used to quantify crystal violet staining density. Pearson correlation coefficient analysis between ML crystal violet staining density and osmolality was calculated as r = –0.7781 (P = .0394).

Hyperosmolar Lubricants Are Cytotoxic to ML VECs and Reduce Cell Viability

To quantify the cytotoxicity and changes in morphology that select lubricants incur on VECs in vitro, cytotoxicity and cytolysis were measured by LDH assay after treatment with 1:10 dilutions of selected lubricants at 24 hours (Figure 2A). EZ Jelly, K-Y Jelly, and Astroglide (P ≤ .01) and K-Y Warming Jelly and Conceptrol (4% N-9) (P ≤ .001) all increased cytotoxicity at 24 hours compared with untreated controls. Correlation analysis indicated a strong positive correlation between osmolality of the selected lubricants and cytotoxicity at 24 hours (Figure 2B; r = 0.7326, P = .0306). Conceptrol was excluded from this analysis due to its active ingredient, the detergent N-9, known to cause cell death, hence its inclusion in this study as a positive control for cytotoxicity.

Figure 2.

Treatment with hyperosmolar vaginal lubricants induces cytotoxicity and reduces monolayer vaginal epithelial cell (ML VEC) viability at 24 hours. ML VECs were treated with a 1:10 dilution of vaginal lubricants in cell media for 24 hours. A, Percentage cytotoxicity was measured using lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay to detect the production of the cytosolic enzyme LDH on induction of cellular toxicity. Spectrophotometric absorbance was measured at 24 hours, and each bar represents the percentage of cytotoxicity calculated relative to a ×10 lysis control. Statistical analysis was conducted by one-tailed Mann–Whitney U test, and data were collected from 3 independent experiments. B, Pearson correlation coefficient (r) analysis was used to measure the linear correlation between lubricant osmolality and percentage cytotoxicity at 24 hours. A positive correlation r value of 0.7326 was calculated with P = .0306. C, Percentage cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. MTT is produced by actively proliferating cells, and this colorimetric assay was used to measure cell viability relative to untreated ML VECs at 24 hours after treatment with vaginal lubricants. Statistical significance was determined by a one-tailed Mann–Whitney U test, and data are representative of 3 independent experiments. **P ≤ .01, ***P ≤ .001, ****P ≤ .0001.

MTT assay was used to quantify changes in cell proliferation/viability (Figure 2C). At 24 hours, treatment with Good Clean Love (P ≤ .01), EZ Jelly (P ≤ .001), and K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, K-Y Warming Jelly, and Conceptrol (P ≤ .0001) markedly reduced cell viability. K-Y Warming Jelly was excluded from analysis as the warming properties of this compound and the ingredients within the formulation interfered with the MTT assay, producing false-positive results for cell viability when tested alone. These data were confirmed at 1 hour, and McKesson (P ≤ .05), EZ Jelly, K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, and Conceptrol (P ≤ .01) also all reduced cell viability at this time point (data not shown). These data indicate a relationship between vaginal lubricant osmolality and cytotoxicity within ML VECs, and that select lubricants decrease ML VEC viability at 24 hours.

Select Lubricants Alter 3-D VEC Viability In Vitro

To validate and extend the results obtained from ML cell culture, we used a robust 3-D VEC model. VEC aggregates were treated with a 1:10 dilution of the selected lubricants for 24 hours. The LDH assay confirmed that Astroglide (P ≤ .05) and EZ Jelly, K-Y Jelly, and Conceptrol (P ≤ .01) have a significantly negative effect on 3-D VECs across 3 independent experiments (Figure 3A). The MTT assay was not conducted as the formazan product would not dissolve, and hence could not be quantified, upon addition of the dimethyl sulfoxide detergent. Therefore, Trypan blue exclusion was used to enumerate the number of viable cells per treatment group, as compared to the untreated negative control. An inverse relationship between 3-D VEC viability and cytotoxicity was observed (r = –0.7468, P = .0333) (Figure 3B). A comparison between cytotoxicity observed in MLs and our 3-D model was made using Pearson correlation. Treatment groups were tested with (Figure 3C; r = 0.9512, P = .0003) and without (Figure 3D; r = 0.6348, P = .1256) the inclusion of Conceptrol, displaying the distinct effect of our positive control, 4% N-9, on these data. On exclusion of Conceptrol, we observed a positive correlation between the 2 models that did not reach statistical significance. EZ and K-Y Jelly caused higher toxicity in both models and K-Y Warming Jelly and Astroglide in MLs, whereas Good Clean Love and McKesson displayed lower levels of cytotoxicity in both models. No lubricant was more cytotoxic in our 3-D model than in MLs (Figure 3C and 3D). These data confirm that the 3-D VEC bioreactor model is more robust than ML cell culture and select lubricants remain cytotoxic at 24 hours.

Figure 3.

Treatment with select vaginal lubricants causes cytotoxicity and reduces cell viability in 3-dimensional (3-D) vaginal epithelial cell (VEC) aggregates at 24 hours. The 3-D VECs were treated with a 1:10 dilution of vaginal lubricants in cell media for 24 hours. A, Percentage cytotoxicity was measured via lactate dehydrogenase assay, and spectrophotometric absorbance was measured at 24 hours. Each bar represents the percentage of cytotoxicity calculated relative to a ×10 lysis control. Statistical analysis was conducted by a one-tailed Mann–Whitney U test, and data are the average of 3 independent experiments. B, Mean percentage cytotoxicity of each lubricant treatment was plotted on the left y-axis (dashed line) and lubricants were listed from left to right in order of increasing osmolality. The positive control for cytotoxicity in this study, Conceptrol, which contains 4% nonoxynol-9 (N-9), was placed on the far right of the x-axis. Cell viability of 3-D VECs was counted using Trypan blue exclusion (solid line) and displayed on the right y-axis. A strong negative correlation r value of –0.7468 was calculated with a P value of .0333. *P ≤ .05, **P ≤ .01. C, Pearson correlation analysis between monolayer (ML) and 3-D cytotoxicity was conducted including Conceptrol (4% N-9), and a strong positive coefficient (r = 0.9512, P = .0003) was calculated. Dashed lines identify quadrants of the graph. D, Pearson correlation analysis of ML vs 3-D cytotoxicity excluding Conceptrol (r = 0.6348, P = .1256).

Select Lubricants Alter Barrier Targets and Inflammatory Mediator Expression in 3-D VECs

To assess whether vaginal lubricants alter the protein levels of immune mediators and barrier targets, and ultimately impact host immune response mechanisms, we used BioPlex analysis. Our analysis revealed that at 24 hours, the levels of IL-1RA (P ≤ .05), 1L-1α, MIF, EMMPRIN, and Fas (P ≤ .0001), MUC1 (P ≤ .001), and MUC16 (P ≤ .005) were increased after treatment with Conceptrol, and that Astroglide treatment increased levels of CCL20, IL-1RA (P ≤ .05), and IL-1α, MIF, and MMP-2 (P ≤ .0001). IL-8 (P ≤ .0001), RANTES and MMP-1 (P ≤ .05–P ≤ .0001), and MMP-10 (P ≤ .0001) were decreased after treatment with all lubricants except Good Clean Love as compared to untreated cells (Supplementary Figure 1). Hierarchical clustering analysis of these data (Figure 4) highlighted the increased levels of select local inflammatory mediators such as IL-1α at 24 hours in hyperosmolar lubricant–treated cells. Clinical lubricants (McKesson and EZ) clustered together, whereas the lowest osmolality lubricant Good Clean Love clustered with, and showed similar levels of mediators as, untreated samples. We also observed a trend of increased levels of the tested targets when cytotoxic ingredients such as N-9 and polyquaternium-15 were present (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Cluster analysis identifies lubricants with potentially harmful epithelial barrier outcomes. Heat map of altered immune mediator and barrier target secretion. Three-dimensional (3-D) vaginal epithelial cells were treated with lubricants at 1:10 for 24 hours and cell supernatant was taken from 3 independent experiments. The data were mean centered, and variance was scaled for each target and is presented as log2-transformed data. Lubricants are grouped within clusters determined by hierarchical cluster analysis. Clustering of the heat map was based on Euclidean distance between rows and columns and average linkage cluster algorithm. Significance of protein induction levels as compared to untreated was conducted on log2-tranformed data using one-way analysis of variance. Results with a P value ≤.05 were considered significant. Conceptrol (4% N-9) was included as a positive control for cytotoxicity. Osmolality and 3-D cytotoxicity of corresponding lubricant treatment are shown beneath cluster analysis. Abbreviations: CCL, C-C motif chemokine ligand; EMMPRIN, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer; IL, interleukin; MIF, macrophage migration inhibitory factor; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MUC, mucin; N-9, nonoxynol-9; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal expressed and secreted protein.

DISCUSSION

We sought to assess the effect of both clinical and personal vaginal lubricants on the local vaginal microenvironment using 2 in vitro models—first, a human monolayer VEC culture, and second, a robust, well-established, 3-D human bioreactor cell culture model, a more physiologically relevant model characterized by a stratified squamous epithelium [23, 28]. The lubricants included in this study were selected to represent a range of commercially available products and those used in clinical settings. Following the application of hyperosmolar lubricant products, we observed distinct negative changes in epithelial cell viability, cytotoxicity, morphology, the induction of specific inflammatory mediators, and an overall decrease in MMPs.

The history of the spermicide N-9 is informative for current efforts in lubricant and microbicide formulation. N-9 was originally investigated for potential antiviral action [35, 36]; however, once the compound entered larger randomized controlled trials, it was found to increase risk of HIV and cause damage to the vaginal epithelium [17]. Since then, the safety of commonly utilized rectal and vaginal lubricants were called into question, and recent findings have indicated that the osmolality of lubricant formulations may play an important role in epithelial barrier breach [16, 32, 33]. The present study confirmed that the N-9-containing product, Conceptrol, as well as non-N-9–containing products (EZ Jelly, K-Y Jelly, Astroglide Liquid, and K-Y Warming Jelly) were cytotoxic to VECs. We also observed a strong correlation between increasing lubricant osmolality and cytotoxicity and confirmed a trend that higher-osmolality lubricants, above the WHO-recommended osmolality of 1200 mOsm/kg [20], induce greater vaginal epithelial damage. A reduction in VEC integrity, as displayed by the loss of epithelial intercellular connections, may predispose a woman to increased risk of sexually transmitted infection (STI) acquisition [37], and our data identify the need for further research into the association between vaginal lubricants and STI acquisition in the context of the vaginal epithelium. In addition, the impact of excipients, such as tocopherol, chlorhexidine gluconate, parabens, and PEG-150, on the vaginal epithelium requires further investigation to elucidate how specific compounds and formulations play a role in altering the local microenvironment.

Previously, we have demonstrated that the rotating wall vessel bioreactor–derived 3-D VEC aggregates can be used for a variety of downstream applications [23]. Human 3-D VEC aggregates are fully differentiated and exhibit in vivo–like features such as tight junctions, mucin expression, secretion of immune mediators, microvilli, and microridge formation, and can effectively investigate host–microbe interactions [23, 28, 30, 38]. In prior work, we used N-9 during the characterization of our 3-D model to assess the graded cytotoxic impact and the induction of inflammatory mediators such as TRAIL and IL1-RA [28]. Though similar cytotoxicity trends were observed between the 2 models, a reduction in statistical significance was observed, with higher 3-D cell viability across all treatment groups. Therefore, the presented data confirmed that our 3-D model is more resistant than VEC monolayers to lubricant cytotoxicity, with only EZ Jelly, K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, and Conceptrol displaying high levels of cytotoxicity at 24 hours, as was previously reported for Conceptrol [28].

In addition to inducing changes in cellular morphology, the more cytotoxic hyperosmolar lubricants increased the production of local immune mediators within the 3-D VEC model. Abnormal secretion of inflammatory mediators hinders the body’s ability to fight infection and disrupts homeostasis [39]. Previous studies have demonstrated that N-9 is associated with significant increases in IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-8 [40]. We confirmed that hyperosmolar lubricants (K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, K-Y Warming Jelly, and Conceptrol) increased levels of IL-1α in our 3-D VEC model, as well as MIF. Increased expression of MIF at sites of inflammation could play a role in regulating macrophage function in host immune responses [41]. Conceptrol increased levels of EMMPRIN, which modulates the production of MMPs. EMMPRIN dysregulation could play a role in breakdown of the cervical plug, facilitating upper genital tract infections [42]. Interestingly, MMP-1, -7, -9, and -10 showed reduced levels after lubricant treatments, with EZ Jelly displaying the most pronounced reduction. However, McKesson, Astroglide, and K-Y Warming increased MMP-2 levels. Conceptrol treatment increased the levels of the membrane-associated mucins MUC1 and MUC16 and Fas, an inducer of apoptosis. MUC1 and MUC16 are components of the vaginal epithelial barrier [28] and possess transmembrane signaling domains that could play a role in host defense mechanisms against invading pathogens [43]. MUC16 is a heavily glycosylated mucin that creates a hydrophilic environment providing both lubrication and a barrier to locally applied compounds or invading pathogens [44]. Therefore, upregulation of MUC1, MUC16, EMMPRIN, and dysregulation of MMPs by vaginal lubricants could hold important implications for both infection and epithelial barrier function; however, this will require further research.

The duration that lubricants persist within the vagina is understudied. One study observed that condom-based lubricant can persist for up to 35 hours; however, this is likely to differ between women [45]. The duration of the experiments presented here were between 4 and 24 hours; however, a reduction in the natural “washing-out” of lubricants in vivo could impact results. Although our 3-D VEC model is well-established and characterized as a stratified squamous epithelium, no model currently recapitulates all aspects of the human vaginal epithelium, including pH [23, 28].

Our findings validate and extend prior work suggesting an association between hyperosmolar lubricants and cytotoxicity to the vaginal mucosal surface, which could have potential implications for risk to bacterial vaginosis, as well as susceptibility to HIV and STI transmission and acquisition during rectal or vaginal intercourse [16]. The lubricants evaluated in this study were chosen to reflect those currently commercially available, highlighting that the majority of vaginal lubricants are well above the WHO guidelines for osmolality. The use of in vitro human VEC models, used in conjunction with the current rabbit vaginal irritation model, could provide a cost-effective method of assessing lubricant cytotoxicity in a more physiologically relevant model. Finally, well-designed longitudinal studies are needed to better understand how personal lubricant products affect epithelial barriers, microbiota, and genital inflammation and, in turn, how these disturbances in the vaginal microenvironment affect risk for STIs.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the members of the Herbst-Kralovetz laboratory for productive discussions on this research. The authors also acknowledge the University of Bath Placement Program.

Author contributions. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number RO1-AI119012 to R. M. B.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: Infectious Diseases Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, August 2018. Abstract 9.

REFERENCES

- 1. Herbenick D, Reece M, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Ghassemi A, Fortenberry JD. Women’s vibrator use in sexual partnerships: results from a nationally representative survey in the United States. J Sex Marital Ther 2010; 36:49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown JM, Hess KL, Brown S, Murphy C, Waldman AL, Hezareh M. Intravaginal practices and risk of bacterial vaginosis and candidiasis infection among a cohort of women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121:773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gallo MF, Sharma A, Bukusi EA, et al. Intravaginal practices among female sex workers in Kibera, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect 2010; 86:318–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hassan WM, Lavreys L, Chohan V, et al. Associations between intravaginal practices and bacterial vaginosis in Kenyan female sex workers without symptoms of vaginal infections. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34:384–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leiblum SR, Hayes RD, Wanser RA, Nelson JS. Vaginal dryness: a comparison of prevalence and interventions in 11 countries. J Sex Med 2009; 6:2425–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nappi RE, Mattsson L-Å, Lachowsky M, Maamari R, Giraldi A. The CLOSER survey: impact of postmenopausal vaginal discomfort on relationships between women and their partners in Northern and Southern Europe. Maturitas 2013; 75:373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. North American Menopause Society. Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2013; 20:888–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin DH. The microbiota of the vagina and its influence on women’s health and disease. Am J Med Sci 2012; 343:2–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gosmann C, Anahtar MN, Handley SA, et al. Lactobacillus-deficient cervicovaginal bacterial communities are associated with increased HIV acquisition in young South African women. Immunity 2017; 46:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brotman RM, Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, et al. Bacterial vaginosis assessed by gram stain and diminished colonization resistance to incident gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal genital infection. J Infect Dis 2010; 202:1907–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marrazzo JM, Thomas KK, Agnew K, Ringwood K. Prevalence and risks for bacterial vaginosis in women who have sex with women. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37:335–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Graham SM, et al. A prospective study of risk factors for bacterial vaginosis in HIV-1-seronegative African women. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35:617–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitchell C, Manhart LE, Thomas K, Fiedler T, Fredricks DN, Marrazzo J. Behavioral predictors of colonization with Lactobacillus crispatus or Lactobacillus jensenii after treatment for bacterial vaginosis: a cohort study. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2012; 2012:706540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brotman RM, Ravel J, Cone RA, Zenilman JM. Rapid fluctuation of the vaginal microbiota measured by Gram stain analysis. Sex Transm Infect 2010; 86:297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mowat A, Newton C, Boothroyd C, Demmers K, Fleming S. The effects of vaginal lubricants on sperm function: an in vitro analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet 2014; 31:333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ayehunie S, Wang YY, Landry T, Bogojevic S, Cone RA. Hyperosmolal vaginal lubricants markedly reduce epithelial barrier properties in a three-dimensional vaginal epithelium model. Toxicol Rep 2018; 5:134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Van Damme L, Ramjee G, Alary M, et al. COL-1492 Study Group Effectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360:971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roddy RE, Cordero M, Cordero C, Fortney JA. A dosing study of nonoxynol-9 and genital irritation. Int J STD Aids 1993; 4:165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rustomjee R, Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Laga M, Stein Z. Phase 1 trial of nonoxynol-9 film among sex workers in South Africa. AIDS 1999; 13:1511–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization. Use and procurement of additional lubricants for male and female condoms: WHO/UNFPA/FHI.http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/76580/WHO_RHR_12.33_eng.pdf;jsessionid=A7FCF42EAA43BA8CD70628CC529A5AEA?sequence=1. Accessed 15 August 2018.

- 21. Begay O, Jean-Pierre N, Abraham CJ, et al. Identification of personal lubricants that can cause rectal epithelial cell damage and enhance HIV type 1 replication in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2011; 27:1019–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Food and Drug Administration. Over-the-counter drug products; safety and efficacy review. Federal Register. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2003:75585–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Herbst-Kralovetz MM, Pyles RB, Ratner AJ, Sycuro LK, Mitchell C. New systems for studying intercellular interactions in bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 2016; 214(Suppl 1):S6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Costin GE, Raabe HA, Priston R, Evans E, Curren RD. Vaginal irritation models: the current status of available alternative and in vitro tests. Altern Lab Anim 2011; 39:317–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barberini F, De Santis F, Correr S, Motta PM. The mucosa of the rabbit vagina: a proposed experimental model for correlated morphofunctional studies in humans. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1992; 44:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jacques M, Olson ME, Crichlow AM, Osborne AD, Costerton JW. The normal microflora of the female rabbit’s genital tract. Can J Vet Res 1986; 50:272–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Witkin SS. The vaginal microbiome, vaginal anti-microbial defence mechanisms and the clinical challenge of reducing infection-related preterm birth. BJOG 2015; 122:213–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hjelm BE, Berta AN, Nickerson CA, Arntzen CJ, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Development and characterization of a three-dimensional organotypic human vaginal epithelial cell model. Biol Reprod 2010; 82:617–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barrila J, Radtke AL, Crabbé A, et al. Organotypic 3D cell culture models: using the rotating wall vessel to study host-pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010; 8:791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Radtke AL, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Culturing and applications of rotating wall vessel bioreactor derived 3D epithelial cell models. J Vis Exp 2012. doi:10.3791/3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wolf L. Studies raise questions about safety of personal lubricants. Chem Eng News 2012; 90:46–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dezzutti CS, Brown ER, Moncla B, et al. Is wetter better? An evaluation of over-the-counter personal lubricants for safety and anti-HIV-1 activity. PLoS One 2012; 7:e48328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fuchs EJ, Lee LA, Torbenson MS, et al. Hyperosmolar sexual lubricant causes epithelial damage in the distal colon: potential implication for HIV transmission. J Infect Dis 2007; 195:703–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Metsalu T, Vilo J. ClustVis: a web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using principal component analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43:W566–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miller CJ, Alexander NJ, Gettie A, Hendrickx AG, Marx PA. The effect of contraceptives containing nonoxynol-9 on the genital transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus in rhesus macaques. Fertil Steril 1992; 57:1126–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hillier SL, Moench T, Shattock R, Black R, Reichelderfer P, Veronese F. In vitro and in vivo: the story of nonoxynol 9. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 39:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thurman AR, Doncel GF. Innate immunity and inflammatory response to Trichomonas vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis: relationship to HIV acquisition. Am J Reprod Immunol 2011; 65:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gardner JK, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Three-dimensional rotating wall vessel-derived cell culture models for studying virus-host interactions. Viruses 2016; 8. pii:E304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Deeks SG, Walker BD. The immune response to AIDS virus infection: good, bad, or both? J Clin Invest 2004; 113:808–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mauck CK, Lai JJ, Weiner DH, et al. Toward early safety alert endpoints: exploring biomarkers suggestive of microbicide failure. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29:1475–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oddo M, Calandra T, Bucala R, Meylan PR. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor reduces the growth of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Infect Immun 2005; 73:3783–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Witkin SS, Mendes-Soares H, Linhares IM, Jayaram A, Ledger WJ, Forney LJ. Influence of vaginal bacteria and D- and L-lactic acid isomers on vaginal extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer: implications for protection against upper genital tract infections. MBio 2013; 4. doi:10.1128/mBio.00460-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Carson DD, DeSouza MM, Kardon R, Zhou X, Lagow E, Julian J. Mucin expression and function in the female reproductive tract. Hum Reprod Update 1998; 4:459–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blalock TD, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, et al. Functions of MUC16 in corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48:4509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tottey LS, Coulson SA, Wevers GE, Fabian L, McClelland H, Dustin M. Persistence of polydimethylsiloxane condom lubricants. J Forensic Sci 2019; 64:207–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.