Abstract

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) serotyping is not considered to have significant impact on liver graft survival and does not factor into U.S. organ allocation. Immune-related liver diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) have been speculated to represent a disease subgroup that may have significantly different graft outcomes depending on HLA donor/recipient characterization. The aim of this study was to investigate whether HLA serotyping/matching influenced post-transplant graft failure for immune-related liver diseases using the United Network for Organ Sharing database. From 1994 to 2015, 5665 patients underwent first-time liver-only transplants for PSC, AIH, and PBC with complete graft survival and donor/recipient HLA data. Graft failure was noted in 38.6% (2188/5665), and all groups had comparable 5-year graft survival (75.1%−78.8%, P = 0.069). The overall degree of, and loci-specific mismatch level, did not influence outcomes. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression noted increased graft failure risk for recipient HLA-B7, HLA-B57, HLA-B75, HLA-DR13 and donor HLA-B55, HLA-B58, and HLA-DR8 for PSC patients, protective effects for recipient HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR3 for AIH patients, and increased risk for HLA-DR7 for AIH patients. These findings warrant further investigation to evaluate the impact of HLA serotyping on post-transplant outcomes.

Keywords: autoimmune hepatitis, human leukocyte antigen, liver transplant, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Current liver transplantation dogma contends that human leukocyte antigen (HLA) serotyping and matching for donor and recipient do not produce a clinically significant effect on liver transplant outcomes. HLA matching for liver transplantation has demonstrated inconsistent results, with studies claiming both advantageous1,2 and detrimental effects.3,4 Some observations have noted a possible dualistic role of HLA compatibility in liver transplantation, where greater HLA matching protected against rejection though increased nonrejection-related graft failure.5,6 A large United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)/Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) data-base study found no association between graft survival and HLA matching at the A, B, and DR loci.7 As such, HLA serotyping is not routinely performed nor is it a factor in the allocation strategy for liver transplantation. However, the possibility that HLA serotyping and matching may be particularly important for immune-related liver disease including primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) has been postulated by investigators.8,9 Particular HLA serotypes have been associated with immune-related liver disease, such as HLA-B8 and HLA-DR3 for PSC,10,11 HLA-DR4, HLA-DR13 and HLA-DR17 for AIH,12,13 and HLA-DR7 and HLA-DR8 for PBC.14,15 Further, some smaller studies have identified HLA serotypes that predict recurrence after liver transplantation, such as HLA-DR8 for PSC,16 HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4 for AIH,17 and HLA-B48 for PBC.18 The UNOS/OPTN database has not previously been used to thoroughly investigate the potential consequences of donor and recipient HLA serotypes on liver transplant outcomes for immune-related liver diseases. The aim of this study was to utilize the UNOS/OPTN database to investigate whether HLA serotyping and matching influenced post-transplant graft failure in immune-related liver disease patients.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

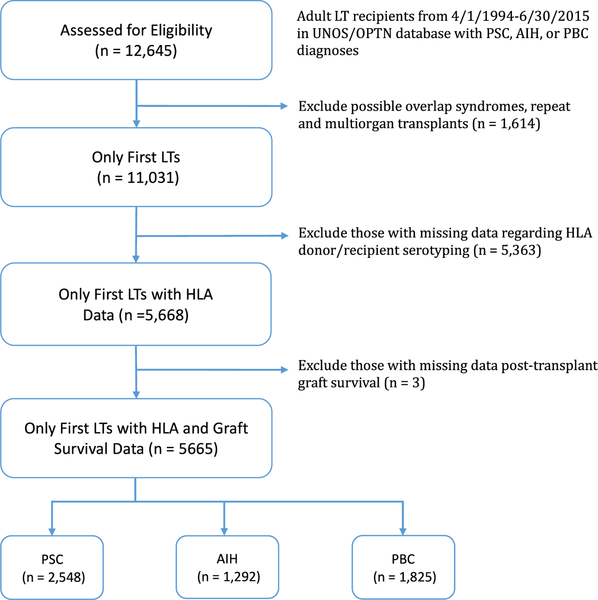

Data were obtained from UNOS/OPTN Standard Transplant Analysis and Research files as of 9/25/2015. All adult (age ≥18 years) liver transplant recipients from 4/1/1994 to 6/30/2015 with a primary diagnosis of PSC, AIH, or PBC were eligible for inclusion (n = 12 645). Multiorgan or retransplantation recipients (n = 1390) were excluded. Recipients with a secondary diagnosis of PSC, AIH, or PBC (eg, a primary diagnosis of PSC and a secondary diagnosis of AIH), which may represent a possible overlap syndrome, were also excluded (n = 224) so as to better isolate the role of HLA serotyping for each diagnosis. Liver transplant recipients with missing data for HLA donor and recipient serotyping (n = 5363) or post-transplant graft survival were additionally excluded (n = 3).

The causes of graft failure were classified into the following categories: disease recurrence, biliary tract complication, vascular thrombosis, chronic rejection, acute rejection, primary nonfunction, and other. They were determined from coded responses to the contributing causes of graft failure variables, of which multiple could be selected. Free-text responses to the “other” category were recoded according to the main classifications when possible. This was performed in order to obtain the cause of graft failure for as many recipients as possible. In all, a cause of graft failure was assigned in 875/2188 cases (40.0%).

HLA mismatch was reported in the UNOS database as 0–6 for overall mismatch and 0–2 for mismatch at each locus (A, B, DR). The degree of overall mismatch was grouped into 0–2, 3–4, and 5–6 for analysis. The individual HLA serotypes were analyzed as the reported computed antigens, with the exception of HLA-DR17 and HLA-DR18, which were recoded to the parent HLA-DR3 due to a large proportion being reported as HLA-DR3. In addition, because HLA-A1, HLA-B8, and HLA-DR3 are in tight linkage disequilibrium, these serotypes were considered both individually and as a haplotype.

To account for any possible time-related bias in outcomes due to HLA typing being more common in earlier transplants, the study population was divided into three eras (1994–1998, 1999–2005, and 2006–2015), each containing approximately one-third of the transplants included in the analysis.

2.1 |. Statistical analysis

Comparisons of baseline characteristics by liver disease etiology were made using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, depending on the normality of the distribution. Graft survival was computed using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared using log-rank tests at the intervals of 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years. Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to assess the relationship between graft failure and the degree of overall and loci-specific HLA mismatch as well as specific HLA recipient/donor serotypes and matching for each liver disease etiology. The univariate analyses of recipient HLA serotype, donor HLA serotype, and recipient/donor HLA matching status were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate (FDR) at 5%, and HLA characteristics with adjusted P-values <0.25 were included in the multivariable model. A more lenient alpha was chosen so as not to exclude potentially useful predictors in screening and to allow for further refinement by adjusting for other recipient and donor factors. The HLA-A1-B8-DR3 haplotype and its individual serotypes were not included in the same multivariable models. Recipient covariates considered for inclusion included age, sex, race/ethnicity, location at transplant (intensive care unit [ICU], hospital, ambulatory), total bilirubin at transplant, creatinine at transplant, and albumin at transplant. Donor covariates included donor age (<60 years vs >60 years), deceased vs living donor, donation after cardiac death (DCD) donor, and graft type (split vs whole). Predictors were retained in the multivariable models at P < 0.05 using a stepwise selection process. Each multivariate model was adjusted for the era of transplantation. All analyses were performed using SAS® Studio software, version 3.5 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and a two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 |. RESULTS

A total of 4845 PSC, 2591 AIH, and 3598 PBC adult patients were transplanted during the study period excluding possible overlap syndromes, multiorgan transplants and retransplants. Of these recipients, 52.6% (2548/4845) of PSC, 49.9% (1292/2591) of AIH, and 50.7% (1825/3598) of PBC patients had complete HLA recipient/donor data and graft survival information sufficient for study inclusion (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of patients included in this study. AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; LT, liver transplant; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis

Baseline recipient and donor characteristics of included patients are described in Table 1. PBC patients were older at transplant and more likely to be female than the other groups. AIH patients had significantly lower median bilirubin at transplant compared to the other groups, and along with PBC, had the smallest proportion of living donor transplants.

TABLE 1.

Recipient and donor characteristics at transplant

| PSC n = 2548, n (%) |

AIH n = 1292, n (%) |

PBC n = 1825, n (%) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | ||||

| Age (y)a | 48 (38–57) | 49 (37–59) | 56 (49–62) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1692 (66.4) | 303 (23.4) | 242 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 2123 (83.3) | 877 (67.9) | 1474 (80.8) | <0.001 |

| Black | 294 (11.5) | 202 (15.6) | 90 (4.9) | |

| Hispanic | 90 (3.5) | 166 (12.8) | 209 (11.4) | |

| Asian | 26 (1.0) | 28 (2.2) | 31 (1.7) | |

| Other | 15 (0.6) | 19 (1.5) | 21 (1.2) | |

| Location at transplant | ||||

| ICU | 170 (6.7) | 167 (12.9) | 184 (10.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalized | 347 (13.6) | 247 (19.1) | 269 (14.7) | |

| Laboratory values and scores at transplanta | ||||

| MELD scoreb | 19 (14–25) | 21 (15–30) | 20 (15–27) | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 6.0 (2.6–14.1) | 3.7 (2.0–10.3) | 5.6 (2.7–12.7) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/0.9 dL) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) | 2.9 (2.4–3.3) | 2.9 (2.5–3.4) | <0.001 |

| Donor | ||||

| Donor >60 y | 314 (12.3) | 171 (13.2) | 269 (14.8) | 0.067 |

| Living donor | 229 (9.0) | 44 (3.4) | 91 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| DCD donor | 67 (2.6) | 32 (2.5) | 44 (2.4) | 0.893 |

| Split graft | 278 (10.9) | 67 (5.2) | 138 (7.6) | <0.001 |

DCD, donation after cardiac death; ICU, intensive care unit; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease.

Data expressed as median (IQR).

Available for post-2/27/2002 transplants (n = 1440/2548, 684/1292, 886/1825).

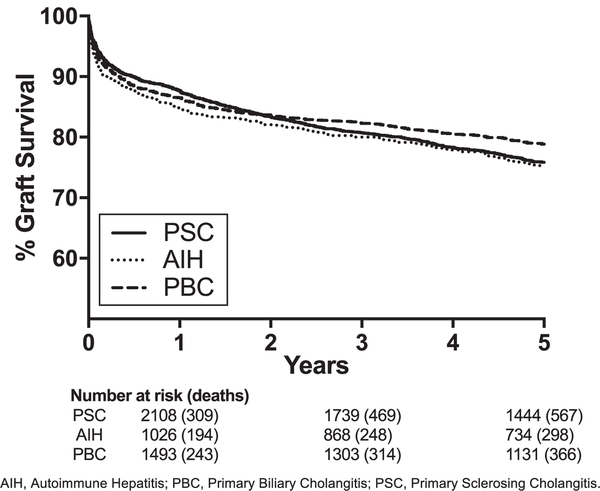

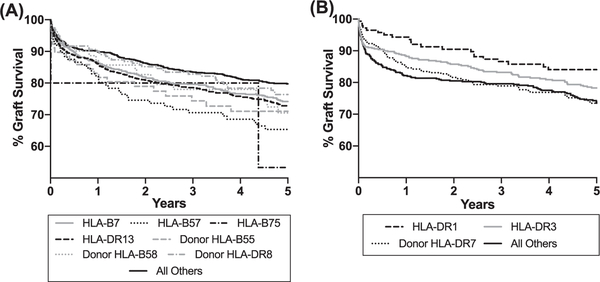

Graft failure was noted in 38.6% (2188/5665) over the time period. Graft survival by recipient disease etiology is depicted in Figure 2. All groups had comparable 5-year graft survival (range 75.1%−78.8%, P = 0.069). Causes of graft failure were reported in 40.0% (875/2188). The frequency of graft failure cause by disease etiology based on reported data are described in Table 2. Based on data provided to the OPTN, PSC was more likely than PBC and AIH to have disease recurrence. PSC was also more likely than AIH to have biliary complications as a cause of graft failure. Significant hazard ratios (P < 0.05) for HLA characteristics in our adjusted multi-variable models for the overall risk of graft failure are described in Table 3, and the graft survival curves for these HLA types are depicted in Figure 3. Hazard ratios found to be significant (P < 0.05) did not differ by era of transportation. The most recent (2006–2015) era was associated with a reduced risk of graft failure compared to the oldest (1994–1998) era in patients with PSC and AIH, but not for PBC. Other significant predictors of graft failure in these groups are described in Table S1 and include location at transplant (PSC: P < 0.001; AIH: P < 0.001), race/ethnicity (AIH: P = 0.01), serum creatinine (AIH: P = 0.02), and donor age >60 (PSC: <0.001; AIH: P = 0.001). No significant associations for HLA characteristics were found for PBC.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for graft survival by disease etiology. AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis

TABLE 2.

Causes of graft failure by disease etiology

| PSC (n = 450/974) | AIH (n = 186/502) | PBC (n = 239/712) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Causes of graft failure, n (%) | ||||

| Disease recurrence | 133 (29.6) | 35 (18.8) | 35 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| Biliary complications | 77 (17.1) | 17 (9.1) | 34 (14.2) | 0.034 |

| Vascular thrombosis | 98 (21.8) | 41 (22.0) | 46 (19.2) | 0.670 |

| Acute rejection | 37 (8.2) | 15 (8.1) | 19 (8.0) | 0.992 |

| Chronic rejection | 58 (12.9) | 33 (17.7) | 34 (14.2) | 0.282 |

| Primary nonfunction | 99 (22.0) | 62 (33.3) | 72 (30.1) | 0.005 |

| Other | 118 (26.2) | 49 (26.3) | 73 (30.5) | 0.448 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios for graft failure by HLA characteristics

| PSC | AIH | |

|---|---|---|

| Recipient HLA-B7 | 1.21 (1.04–1.40), P = 0.012, n = 607 | |

| Recipient HLA-B57 | 1.50 (1.14–1.98), P = 0.004, n = 113 | |

| Recipient HLA-B75 | 3.00 (1.12–8.07), P = 0.029, n = 5 | |

| Recipient HLA-DR1 | 0.61 (0.44–0.85), P = 0.004, n = 146 | |

| Recipient HLA-DR3 | 0.76 (0.63–0.92), P = 0.005, n = 497 | |

| Recipient HLA-DR13 | 1.18 (1.04–1.35), P = 0.010, n = 963 | |

| Donor HLA-B55 | 1.56 (1.12–2.19), P = 0.009, n = 78 | |

| Donor HLA-B58 | 1.57 (1.12–2.22), P = 0.010, n = 72 | |

| Donor HLA-DR7 | 1.28 (1.05–1.57), P = 0.01, n = 305 | |

| Donor HLA-DR8 | 1.30 (1.04–1.63), P = 0.022, n = 200 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Data displayed as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval), P-value, and the overall number (n) with the serotype. Data only reported for P-value <0.05 in the multivariable model.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for graft survival for patients with PSC (A) and AIH (B) by selected donor and recipient HLA types. AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis

Results of our analysis for overall risk of graft failure by degree of HLA and loci-specific mismatch are noted in Table 4. The degree of combined HLA mismatch and loci-specific A-,B-, or DR- mismatch did not significantly impact risk of graft failure for PSC, AIH, and PBC. However, an increased risk of graft failure was noted for B locus matching in AIH (P = 0.045) for 0 vs 1 mismatch (and not 0 vs 2 mismatch). After adjustment, the degree of B locus mismatch was overall not significantly associated with graft failure (P = 0.056), but the comparison between 0 vs 1 mismatch did remain significant (hazard ratio 1.74, 95% confidence interval 1.10–2.74).

TABLE 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios for graft failure by HLA matching at A, B, and DR loci

| PSC | AIH | PBC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined HLA mismatch | |||

| 0–2 vs 3–4 | 0.92 (0.65–1.29) | 0.92 (0.58–1.47) | 0.89 (0.60–1.30) |

| 0–2 vs 5–6 | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) | 0.96 (0.64–1.44) | 1.06 (0.78–1.50) |

| 3–4 vs 5–6 | 0.92 (0.76–1.13) | 1.05 (0.80–1.38) | 1.20 (0.97–1.48) |

| P-value | 0.424 | 0.921 | 0.225 |

| A locus mismatch | |||

| 0 vs 1 | 0.90 (0.70–1.15) | 1.06 (0.75–1.48) | 1.26 (0.97–1.63) |

| 0 vs 2 | 0.80 (0.63–1.03) | 0.94 (0.68–1.32) | 1.20 (0.93–1.56) |

| 1 vs 2 | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 0.89 (0.74–1.07) | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) |

| P-value | 0.106 | 0.463 | 0.226 |

| B locus mismatch | |||

| 0 vs 1 | 1.30 (0.92–1.83) | 1.63 (1.04–2.56) | 0.89 (0.56–1.40) |

| 0 vs 2 | 1.14 (0.82–1.58) | 1.34 (0.87–2.06) | 1.02 (0.65–1.60) |

| 1 vs 2 | 0.88 (0.76–1.01) | 0.82 (0.67–1.00) | 1.15 (0.98–1.35) |

| P-value | 0.116 | 0.046 | 0.231 |

| DR locus mismatch | |||

| 0 vs 1 | 1.05 (0.79–1.40) | 1.20 (0.82–1.74) | 1.17 (0.86–1.60) |

| 0 vs 2 | 1.08 (0.81–1.43) | 1.10 (0.77–1.59) | 1.16 (0.85–1.57) |

| 1 vs 2 | 1.02 (0.90–1.17) | 0.92 (0.76–1.11) | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) |

| P-value | 0.839 | 0.546 | 0.601 |

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Data displayed as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to determine whether HLA serotyping and matching influenced post-1 iver transplant graft failure for immune-related liver diseases. By using the UNOS/OPTN dataset, we were afforded the advantages of a large cataloged sample including increased statistical power, the ability to control for several important donor and recipient confounders, and the capacity to control for the effect of different time periods. Our results suggest that certain recipient and donor HLA characteristics are associated with graft failure among the immune-related liver disease spectrum. Our study adds to the controversy regarding the influence of HLA serotyping on liver transplantation outcomes for immune-related liver disease by identifying donor and recipient HLA characteristics that suggest meaningful impact.

The influence of HLA serotyping and matching on liver transplant outcomes has been a debated topic spanning decades with studies drawing conflicting conclusions. Markus et al5 suggested that HLA compatibility had a dualistic effect on liver transplant outcome: reducing rejection risk, but otherwise increasing risk of graft failure by other immunological processes. Neumann et al19 found that rejection decreased with increased HLA matching, though the number of HLA matches did not influence graft survival. For PSC, in particular, graft survival was significantly impaired in the presence of up to two HLA-DR compatibilities, and in AIH, survival tended to be lower in the presence of more HLA compatibilities.19 Balan et al20 noted that 10-year survival was worse with HLA-A locus mismatch, and that HLA-DR mismatch increased recurrence of autoimmune liver disease. Knechtle et al21 similarly noted that HLA-A locus mismatch worsened graft survival, and that better HLA-A locus matching significantly improved patient and graft survival. Navarro et al, on the other hand, found that the degree of match/mismatch at the HLA-A, HLA-B, or HLA-DR loci had no impact on 5-year graft outcomes in a large OPTN database study.

Our study found that recipient HLA-B7, recipient HLA-B57, recipient HLA-B75, recipient HLA-DR13, donor HLA-B55, donor HLA-B58, and donor HLA-DR8 were associated with significantly increased adjusted hazard ratios for graft failure for PSC patients. This finding is consistent with published literature on HLA-DR8 having an increased association with PSC graft recurrence,16 and with HLA-DR13 having a PSC disease association and implication for worsened post-transplant graft survival.22,23 HLA-DR13 has further been linked to increasing the risk of acute allograft rejection for PSC patients.24 In a subset analysis, we found that individuals with HLA-DR13 in our study population were more likely to experience acute rejection (defined as treated for rejection within 1 year or graft failure due to acute rejection; total N = 1838, 30.6% vs 25.5%, P = 0.017). This is particularly notable given the increased risk of graft failure and death noted in transplant patients who suffer acute rejection.25 HLA-B7 has been associated with elevated IgG4 and suggested to potentially characterize a distinct aggressive phenotype of PSC,26,27 which potentially may explain our findings of increased risk of graft failure with this HLA serotype. Our study also found that recipient HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR3 were protective against graft loss in AIH, whereas HLA-DR7 was associated with increased risk of graft failure. This is in contrast to other studies that have noted increased AIH recurrence in recipient HLA-DR3 patients.17,19

Our study did not find a consistent pattern of overall degree of HLA matching/mismatching nor loci-specific matching/mismatching and graft failure. We performed an additional analysis assessing the risk of graft failure in recipients with zero HLA mismatch compared to all others, and this remained true. Our findings are consistent with Navarro et al7 whom evaluated the UNOS/OPTN database from 1987 to 2002 and did not find an association with HLA compatibility and 5-year graft survival. We did find that mismatch at the B locus appeared to increase the risk of graft failure in recipients with AIH. This was only true of 0 vs 1 mismatch and not 0 vs 2 nor 0 vs 1–2, however, making this finding somewhat difficult to interpret. We believe this 0 vs 1 mismatch finding may represent a type I error as further increasing the number of mismatches at the B locus did not as a pattern increase the risk of graft failure. Our study suggests that although the degree of overall or loci-specific HLA matching does not influence graft outcome for immune-related liver diseases, specific HLA recipient/donor serotypes in PSC and AIH may produce a clinically relevant impact on graft survival.

Strengths of our study include the large number of transplant patients captured in the UNOS/OPTN database with complete HLA serotyping and graft failure outcomes, and the ability to control for multiple influential recipient and donor factors that impact graft survival. We further controlled for a possible era effect by adjusting our analysis by time period to address changes in transplantation management over the years. This further helped us account for potential improvement in accuracy of HLA assignment over time, as typing modalities utilized by transplant centers likely improved through the years with PCR methods.28 Limitations of this study are tied to data missingness in the UNOS/OPTN database. Though our included patient sample is large, we did have to exclude 5366 patients from the analysis because of incomplete HLA serotyping or graft survival data. HLA typing is not required for liver transplants, which likely affected the distribution of patients that were included in this study and potentially contributed to a bias to include more patients from earlier years when HLA typing was more common. Additionally, perhaps patients that were serotyped reflect more aggressive phenotypes of disease that prompted their physicians to order HLA testing or reflect biases of certain centers. Furthermore, the etiology of graft failure was not reported for the vast majority of patients. Graft failure causes such as acute rejection, chronic rejection, and recurrence of primary disease may be related to HLA characteristics, although other causes of graft failure, such as vascular thrombosis, may not share a logical link. Graft failure causes also may sometimes be difficult to ascertain from a clinical standpoint, particularly when distinguishing chronic rejection and advanced recurrent disease by pathology. Furthermore, although the UNOS/OPTN database is extensive, we were unable to control for other factors that influence graft outcomes, namely immune-suppression. These limitations may help explain differences in our results compared to other studies, as they may increase the risk of type 1 error. Despite these limitations, we believe the relationship between HLA serotyping and liver transplant warrants further investigation in the immune-related liver disease spectrum given our substantial results.

In conclusion, our study noted associations between HLA serotyping and graft survival using the UNOS/OPTN database for PSC and AIH patients. We did not find the overall degree of and loci-specific mismatch level to be significant for the immune-related liver disease spectrum. We believe further investigation is needed to further validate these HLA associations with graft survival for PSC and AIH patients given their potential impact on liver transplantation outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding information

National institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: 5T32DK007568–25

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nikaein A, Backman L, Jennings L, et al. HLA compatibility and liver transplant outcome. Improved patient survival by HLA and cross-matching. Transplantation. 1994;58(7):786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson S 3rd, Imagawa DK, Johnson C, et al. UCLA liver transplantation: analysis of immunological factors affecting outcome. Artif Organs. 1996;20(10):1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong T, Donaldson P, Devlin J, Williams R. Repeat HLA-B and -DR loci mismatching at second liver transplantation improves patient survival. Transplantation. 1996;61(3):440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francavilla R, Hadzic N, Underhill J, et al. Role of HLA compatibility in pediatric liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66(1):53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markus BH, Duquesnoy RJ, Gordon RD, et al. Histocompatibility and liver transplant outcome. Does HLA exert a dualistic effect? Transplantation. 1988;46(3):372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donaldson P, Underhill J, Doherty D, et al. Influence of human leukocyte antigen matching on liver allograft survival and rejection: “the dualistic effect”. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 1993;17(6):1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarro V, Herrine S, Katopes C, Colombe B, Spain CV. The effect of HLA class I (A and B) and class II (DR) compatibility on liver transplantation outcomes: an analysis of the OPTN database. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(4):652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doran TJ, Geczy AF, Painter D, et al. A large, single center investigation of the immunogenetic factors affecting liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69(7):1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheil AG, Thompson JF, McCaughan GW, et al. Determinants of successful liver transplantation. Transpl Proc. 1990;22(5):2144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman RW, Varghese Z, Gaul R, Patel G, Kokinon N, Sherlock S. Association of primary sclerosing cholangitis with HLA-B8. Gut. 1983;24(1):38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrumpf E, Fausa O, Forre O, Dobloug JH, Ritland S, Thorsby E. HLA antigens and immunoregulatory T cells in ulcerative colitis associated with hepatobiliary disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17(2):187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Podhorzer A, Paladino N, Cuarterolo ML, et al. The early onset of type 1 autoimmune hepatitis has a strong genetic influence: role of HLA and KIR genes. Genes Immun. 2016;17(3):187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Gerven NM, de Boer YS, Zwiers A, et al. HLA-DRB1*03:01 and HLA-DRB1*04:01 modify the presentation and outcome in autoimmune hepatitis type-1. Genes Immun. 2015;16(4):247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M, Zheng H, Tian QB, Rui MN, Liu DW. HLA-DR polymorphism and primary biliary cirrhosis: evidence from a meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 2014;45(3):270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Invernizzi P. Human leukocyte antigen in primary biliary cirrhosis: an old story now reviving. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2011;54(2):714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alexander J, Lord JD, Yeh MM, Cuevas C, Bakthavatsalam R, Kowdley KV. Risk factors for recurrence of primary sclerosing cholangitis after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(2):245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Koch A, Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, et al. Recurrent autoimmune hepatitis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7(4):302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez EQ, Levy MF, Goldstein RM, et al. The changing clinical presentation of recurrent primary biliary cirrhosis after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;76(11):1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann UP, Guckelberger O, Langrehr JM, et al. Impact of human leukocyte antigen matching in liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75(1):132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balan V, Ruppert K, Demetris AJ, et al. Long-term outcome of human leukocyte antigen mismatching in liver transplantation: results of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Liver Transplantation Database. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2008;48(3):878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knechtle SJ, Kalayolu M, D’Alessandro AM, et al. Histocompatibility and liver transplantation. Surgery. 1993;114(4):667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowlus CL, Li CS, Karlsen TH, Lie BA, Selmi C. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in genetically diverse populations listed for liver transplantation: unique clinical and human leukocyte antigen associations. Liver Transpl. 2010;16(11):1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Futagawa Y, Waki K, Cai J. The association of HLA-DR13 with lower graft survival rates in hepatitis B and primary sclerosing cholangitis Caucasian patients receiving a liver transplant. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(4):600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oertel M, Berr F, Schroder S, et al. Acute rejection of hepatic allografts from HLA-DR13 (Allele DRB1(*)1301)-positive donors. Liver Transpl. 2000;6(6):728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levitsky J, Goldberg D, Smith AR, et al. Acute rejection increases risk of graft failure and death in recent liver transplant recipients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(4):584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berntsen NL, Klingenberg O, Juran BD, et al. Haplotypes and increased serum levels of IgG4 in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(5):924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendes FD, Jorgensen R, Keach J, et al. Elevated serum IgG4 concentration in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(9):2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bozon MV, Delgado JC, Turbay D, et al. Comparison of HLA-A antigen typing by serology with two polymerase chain reaction based DNA typing methods: implications for proficiency testing. Tissue Antigens. 1996;47(6):512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.