Abstract

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) mediates epigenetic gene silencing via tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27-me3). Increased expression of EZH2 is frequently detected in various cancers including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is associated with the silencing of tumor suppressor genes. S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-competitive EZH2 inhibitors fall into the major category of EZH2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. In this study, microarray analyses found that induction of genes related to cholesterol homeostasis is a common effect of SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors in cancer cells. As a representative, GSK343 induced lipid accumulation which promoted cancer cell survival. GSK343 selectively activated sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2), but not SREBP1, in HCC cells. Inhibition of SREBP2 by siRNA reduced cell viability and enhanced the anticancer effect of GSK343. Cancer genomics analysis indicated that SREBP2 upregulation was associated with the poor overall survival of HCC patients. Mechanistically, GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation was unrelated to its original ability to compete with SAM and inhibit EZH2 activity. Instead, GSK343 activated SREBP2 in p38α- and site-1 protease (S1P)-dependent manners. Inhibition of p38α and S1P by SB-202190 and PF-429242, respectively, enhanced the in vitro anticancer activity of GSK343, thereby creating a vulnerability for treating HCC.

Keywords: EZH2, hepatocellular carcinoma, lipid accumulation, MAPK, SREBP

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. The main curative treatments for HCC are still surgical resection and liver transplantation. However, these treatments are suitable for only 15 to 25% of HCC patients [2]. In addition, HCC is relatively chemo-resistant and highly refractory to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Currently, no reliable and effective therapy for patients with advanced or metastatic disease are available [2]. Molecular targeted agents have been viewed as new treatment option in recent years. For example, several multi-kinase inhibitors, including sorafenib, regorafenib, lenvatinib, and cabozantinib, have been approved for treating HCC in 2007, 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively [3-6]. However, these drugs only provide a short increase of median overall survival [3-7]. Therefore, development of more effective therapeutic strategy for HCC is still urgently needed.

Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) belongs to the polycomb group (PcG) proteins that act as transcriptional repressors via chromatin modification. PRC2 consists of the H3K27-specific histone methyltransferases, enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) in complexed with other PcG proteins SUZ12 and EED, which is responsible for mono-, di- and trimethylation at histone H3K27 (H3K27-me1/2/3). EZH2 could recruit histone deacetylase (HDAC) and through EED to repress transcription cooperatively [8-10]. Because EZH2 overexpression is frequently observed in tumors, leading to the suppression of tumor suppressor genes, inhibition of EZH2 serves as potential anticancer treatments [8,9,11-14]. In recent year, numerous EZH2 inhibitors have been developed [15]. The major category belongs to the S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-competitive inhibitors based on the reason that SAM is a universal methyl donor for the catalytic reaction of histone methyltransferases. Several SAM-competitive inhibitors, such as EPZ005687, EPZ-6438 (tazemetostat), EI1, CPI-1205, GSK126, and GSK343, have been demonstrated to selectively kill lymphoma cells with EZH2-activating mutations [16-21]. Among them, EPZ-6438, CPI-1205, and GSK126 have entered phase I/II clinical trials [22]. Recently, a phase I study has demonstrated the favorable safety and anticancer activity of EPZ-6438 in refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced solid tumors [23].

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins 1 and 2 (SREBP1/2) belong to the basic-helix-loop-helix leucine zipper class of transcription factors. SREBP1/2 sense nutrient levels and regulate genes related to lipid metabolism. In the presence of sterols, SREBPs are inactivated and retained in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through the formation of complexes with SREBP-cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) and insulin-induced gene 1 and 2 (INSIG1/2). In cells with low levels of sterols, SCAP and the INSIGs are separated and the SREBP-SCAP complex then travels to the Golgi apparatus to be cleaved to a water-soluble N-terminal domain by site-1 protease (S1P) and site-2 protease (S2P). The mature forms of SREBP1/2 are then entered into the nucleus and bind to specific sterol regulatory elements to upregulate the genes involved in sterol biosynthesis. Sterols then inhibit the SREBP1/2 cleavage and prevent additional sterol synthesis, which forms a negative feedback loop [24].

In this study using GSK343 as a representative SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitor, we found that activation of p38α-dependent S1P/SREBP2 signaling is a novel activity of GSK343, which is independent to its original mechanism of actions (i.e., SAM competition and EZH2 inhibition). Activation of SREBP2 by GSK343 contributes to lipid accumulation and cytoprotective effect in HCC cells. Therefore, intervention of p38α/S1P/SREBP2 signaling pathway enhances the anticancer activity of GSK343, thereby creating a druggable vulnerability for HCC.

Results

Microarray analyses reveal the general induction of genes related to cholesterol homeostasis by SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors

Our previous studies found that two SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors (UNC1999 and GSK343) induce cytotoxic autophagy and cytoprotective unfolded protein response in human cancer cells [25,26]. During the investigation, we notice that induction of genes related to cholesterol homeostasis is one of the major hallmark in UNC1999- and GSK343-treated human colorectal cancer HCT116 cells (Table 1; GSE83633) [25]. To investigate whether this phenomenon was a general common effect of the SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors, we analyzed the microarray data sets of GSK343-treated cancer cells (10 μM GSK343 for 6 and/or 16 h in HepG2, A549, and PLC5 cells) using the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) software against hallmark gene sets [27-30]. As shown in Table 1, “cholesterol homeostasis” hallmark was enriched in all these data sets. Interestingly, a time-dependent enrichment was observed. 34-36% and 48-51% of genes in cholesterol homeostasis pathways were enriched in 6-h and 16-h GSK343-treated cancer cells, respectively. These results indicated that induction of genes related to cholesterol homeostasis is a common effect and an early response of cancer cells treated with SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors.

Table 1.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of cancer cells treated with GSK343 and UNC1999

| Cell line & Treatment | Hallmark in MSigDB | NES | p value | FDR | # of genes in pathways (ratio) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT116: 10 μM GSK343 for 4 h | CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS | 0.55 | 1.000 | 0.994 | 10/73 (14%) | Our previous study (GSE83633) |

| HCT116: 5 μM UNC1999 for 4 h | CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS | 1.79 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 17/73 (23%) | |

| UNFOLDED_PROTEIN_RESPONSE | 1.57 | 0.020 | 0.003 | 25/112 (22%) | ||

| HepG2: 10 μM GSK343 for 6 h | CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS | 1.86 | 0.004 | 0.022 | 25/73 (34%) | This study (GSE129204) |

| A549: 10 μM GSK343 for 6 h | CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS | 2.15 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 26/73 (36%) | |

| MTORC1_SIGNALING | 1.67 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 36/197 (18%) | ||

| HepG2: 10 μM GSK343 for 16 h | CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS | 1.89 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 37/73 (51%) | |

| PLC5: 10 μM GSK343 for 16 h | CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS | 2.88 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 35/73 (48%) | |

| MTORC1_SIGNALING | 2.63 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 55/197 (28%) | ||

| HYPOXIA | 2.35 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 90/198 (45%) | ||

| ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_EARLY | 1.78 | 0.000 | 0.015 | 67/198 (34%) | ||

| REACTIVE_OXIGEN_SPECIES_PATHWAY | 1.77 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 6/45 (13%) | ||

| ANDROGEN_RESPONSE | 1.76 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 24/101 (24%) | ||

| GLYCOLYSIS | 1.76 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 48/198 (24%) | ||

| HEME_METABOLISM | 1.72 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 82/193 (42%) | ||

| UNFOLDED_PROTEIN_RESPONSE | 1.67 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 24/108 (22%) | ||

| FATTY_ACID_METABOLISM | 1.59 | 0.002 | 0.028 | 38/154 (25%) | ||

| UV_RESPONSE_DN | 1.57 | 0.003 | 0.029 | 47/143 (33%) |

Microarray data from EZH2 inhibitor-treated HepG2, PLC5, A549 and HCT116 cells were analyzed by GSEA against hallmark gene sets. Significant (P < 0.01; FDR < 0.05) hallmark gene sets were shown. Although no hallmark gene sets were enriched in HCT116 cells treated with 10 μM GSK343 for 4 h, the result for “CHOLESTEROL_HOMEOSTASIS” hallmark was still listed in table as a comparison.

GSK343 induces lipid accumulation in HCC cells

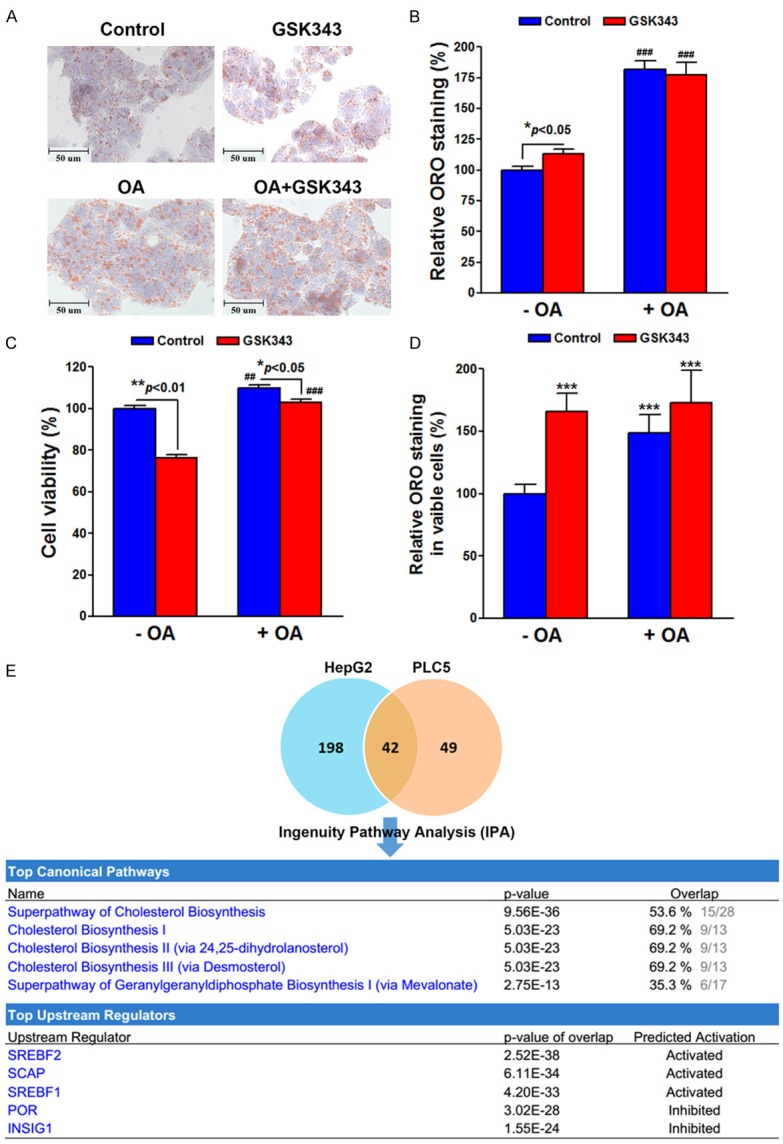

The enrichment of “cholesterol homeostasis” hallmark indicated that GSK343 may alter the intracellular lipid content of cancer cells. To analyze the lipid alterations after GSK343 treatment, the Oil Red O (ORO) staining was performed in HepG2 cells. As shown in Figure 1A and 1B, a slight increase of lipid content (P < 0.05) was found in HepG2 cells treated with 20 μM GSK343 for 6 h. The unsaturated long-chain fatty acid, oleic acid (OA), was used as a positive control. Because GSK343 was a cytotoxic reagent, a parallel cell viability assay was performed. As shown in Figure 1C, treatment of 20 μM GSK343 for 6 h reduced the cell viability. Thus, we normalized the relative ORO staining ratio with cell viability and found that GSK343 significantly (P < 0.001) induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells (Figure 1D). Interestingly, OA seemed to protect HepG2 cells against GSK343-induced cytotoxicity (Figure 1C). Therefore, these results indicated that induction of cholesterol homeostasis pathway by GSK343 leads to lipid accumulation, which promotes cancer cell survival.

Figure 1.

Effect of GSK343 on lipid accumulation and related pathways. HepG2 cells were treated with 20 μM GSK343 for 6 h in the presence or absence of 0.25 mM oleic acid (OA). The lipid content was measured by Oil Red O staining assay. Cells were imaged by inverted microscope (A). The lipid content was quantified by extracting the stain with 100% isopropanol. The absorbance at 492 nm was measured (B). A parallel cell viability (C) was performed for the normalization of lipid content by viable cell numbers (D). In (B), P < 0.001 (###) indicates significant differences between OA-treated and untreated cells. In (C), P < 0.01 (##) and P < 0.001 (###) indicates significant differences between OA-treated and untreated cells. In (D), P < 0.001 (***) indicates significant differences between GSK343/OA-treated and untreated cells. (E) HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with 10 μM GSK343 for 16 h and the gene expression profiles were analyzed by microarray. The overlapped genes (Table 2) were analyzed by IPA for the enrichment of canonical pathways and upstream regulators. The genes for the enrichment were shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) predicts the activation of SREBP signaling pathways by GSK343

To investigate the molecular mechanism for the activation of cholesterol homeostasis pathway by GSK343, the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) was performed using the microarray data sets of HepG2 and PLC5 cells treated with 10 μM GSK343 for 16 h. As shown in Figure 1E, 240 and 91 genes were altered in HepG2 and PLC5 cells, respectively. Forty-two overlapped genes (Table 2) were analyzed by IPA for canonical pathways and upstream regulators. Consistent to the result of GSEA (Table 1), GSK343 regulated genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis (Figure 1E and Table 3). In addition, the analysis for upstream regulators indicated that GSK343 activated SREBF1/2 and SCAP, but inhibited INSIG1 and POR (Figure 1E and Table 4). According to the results of GSEA and IPA, we hypothesized that GSK343 may activate SREBP signaling pathways, leading to cholesterol biosynthesis and lipid accumulation.

Table 2.

The overlapped gene profile that is altered in GSK343-treated HepG2 and PLC5 cells

| Gene Symbol | Description | Fold Change (HepG2) | Fold Change (PLC5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL21R | interleukin 21 receptor | 2.76 | 1.66 |

| ACSS2 | acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 2 | 2.33 | 1.95 |

| HMGCR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase | 2.28 | 2.16 |

| NUPR1 | nuclear protein, transcriptional regulator, 1 | 1.86 | 1.6 |

| SNAI3-AS1 | SNAI3 antisense RNA 1 | 1.86 | 1.72 |

| RASA4 | RAS p21 protein activator 4 | 1.82 | 1.44 |

| MSMO1 | methylsterol monooxygenase 1 | 1.8 | 1.75 |

| RASA4B | RAS p21 protein activator 4B | 1.78 | 1.11 |

| RASA4CP | RAS p21 protein activator 4C, pseudogene | 1.78 | 1.11 |

| LSS | lanosterol synthase (2,3-oxidosqualene-lanosterol cyclase) | 1.72 | 1.25 |

| HMGCS1 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 (soluble) | 1.7 | 1.46 |

| RRAGD | Ras-related GTP binding D | 1.66 | 1.35 |

| SCD | stearoyl-CoA desaturase (delta-9-desaturase) | 1.66 | 1.13 |

| STARD4 | StAR-related lipid transfer (START) domain containing 4 | 1.66 | 1.33 |

| EBP | emopamil binding protein (sterol isomerase) | 1.64 | 1.04 |

| IDI1 | isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase 1 | 1.64 | 1.49 |

| TG | thyroglobulin | 1.61 | 1.39 |

| INHBE | inhibin, beta E | 1.57 | 1.72 |

| C14orf1 | chromosome 14 open reading frame 1 | 1.56 | 1.03 |

| BMF | Bcl2 modifying factor | 1.54 | 1.14 |

| CYP1A1 | cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| PCSK9 | proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 | 1.49 | 1.44 |

| SC5DL | sterol-C5-desaturase (ERG3 delta-5-desaturase homolog, S. cerevisiae)-like | 1.49 | 1 |

| CYP51A1 | cytochrome P450, family 51, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | 1.46 | 1.34 |

| FADS1 | fatty acid desaturase 1 | 1.44 | 1.07 |

| LPIN1 | lipin 1 | 1.37 | 1.41 |

| NSDHL | NAD (P) dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like | 1.35 | 1.01 |

| DDIT4 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4 | 1.33 | 1.25 |

| ELOVL6 | ELOVL fatty acid elongase 6 | 1.32 | 1.33 |

| HSD17B7P2 | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 7 pseudogene 2 | 1.3 | 1.46 |

| OR10A7 | olfactory receptor, family 10, subfamily A, member 7 | 1.29 | 1.17 |

| TRIB3 | tribbles homolog 3 (Drosophila) | 1.29 | 1.74 |

| ALDH1L2 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member L2 | 1.26 | 1.56 |

| MVD | mevalonate (diphospho) decarboxylase | 1.26 | 1.05 |

| GARS | glycyl-tRNA synthetase | 1.2 | 1.01 |

| HSD17B7 | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 7 | 1.19 | 1.46 |

| ASNS | asparagine synthetase (glutamine-hydrolyzing) | 1.15 | 1.3 |

| VLDLR | very low density lipoprotein receptor | 1.14 | 1.36 |

| SQLE | squalene epoxidase | 1.11 | 1.1 |

| DHCR7 | 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase | 1.08 | 1.52 |

| ACAT2 | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2 | 1.06 | 1.16 |

| FDPS | farnesyl diphosphate synthase | 1 | 1.24 |

The fold change value was indicated in log2 scale. Genes were ranked according to their fold changes in HepG2 cells.

Table 3.

Pathway enrichment by IPA for the overlapped gene profile that is altered in GSK343-treated HepG2 and PLC5 cells

| Pathway | Genes in Pathway | Ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superpathway of Cholesterol Biosynthesis | EBP, HMGCS1, NSDHL, ACAT2, FDPS, HMGCR, SC5D, MSMO1, LSS, SQLE, IDI1, HSD17B7, CYP51A1, MVD, DHCR7 | 15/28 (53.6%) | < 0.0001 |

| Cholesterol Biosynthesis I | EBP, LSS, NSDHL, SQLE, HSD17B7, CYP51A1, SC5D, MSMO1, DHCR7 | 9/13 (69.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| Cholesterol Biosynthesis II (via 24,25-dihydrolanosterol) | EBP, LSS, NSDHL, SQLE, HSD17B7, CYP51A1, SC5D, MSMO1, DHCR7 | 9/13 (69.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| Cholesterol Biosynthesis III (via Desmosterol) | EBP, LSS, NSDHL, SQLE, HSD17B7, CYP51A1, SC5D, MSMO1, DHCR7 | 9/13 (69.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| Superpathway of Geranylgeranyldiphosphate Biosynthesis I (via Mevalonate) | HMGCS1, IDI1, FDPS, ACAT2, HMGCR, MVD | 6/17 (35.3%) | < 0.0001 |

Top 5 canonical pathways were shown.

Table 4.

Upstream regulator analysis by IPA for the overlapped gene profile that is altered in GSK343-treated HepG2 and PLC5 cells

| Upstream Regulator | Description | Downstream Genes | Predicted Activity | Activation z-score | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SREBF2 | Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2 | ACSS2, CYP51A1, DHCR7, EBP, ELOVL6, FDPS, HMGCR, HMGCS1, IDI1, LSS, MSMO1, MVD, NSDHL, PCSK9, SC5D, SCD, SQLE, STARD4 | Activated | 4.063 | < 0.0001 |

| SCAP | SREBP-cleavage-activating protein | ACSS2, CYP51A1, DHCR7, ELOVL6, FDPS, HMGCR, IDI1, LSS, MSMO1, MVD, NSDHL, PCSK9, SC5D, SCD, SQLE, STARD4 | Activated | 3.959 | < 0.0001 |

| SREBF1 | Sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 | ACSS2, CYP51A1, DHCR7, ELOVL6, FADS1, FDPS, HMGCR, HMGCS1, IDI1, LPIN1, LSS, MSMO1, MVD, NSDHL, PCSK9, SC5D, SCD, SQLE, STARD4 | Activated | 4.238 | < 0.0001 |

| POR | P450 (cytochrome) oxidoreductase | ACAT2, ASNS, CYP1A1, CYP51A1, DHCR7, ELOVL6, FDPS, HMGCR, HMGCS1, IDI1, LSS, MSMO1, MVD, NSDHL, SC5D, SCD, SQLE, STARD4 | Inhibited | -4.084 | < 0.0001 |

| INSIG1 | Insulin-induced gene 1 | ACSS2, CYP51A1, DHCR7, ELOVL6, FADS1, FDPS, HMGCR, HMGCS1, IDI1, LPIN1, LSS, SCD, SQLE, STARD4 | Inhibited | -3.654 | < 0.0001 |

Top 5 upstream regulators were shown.

GSK343 activates SREBP2 that promotes cancer cell survival

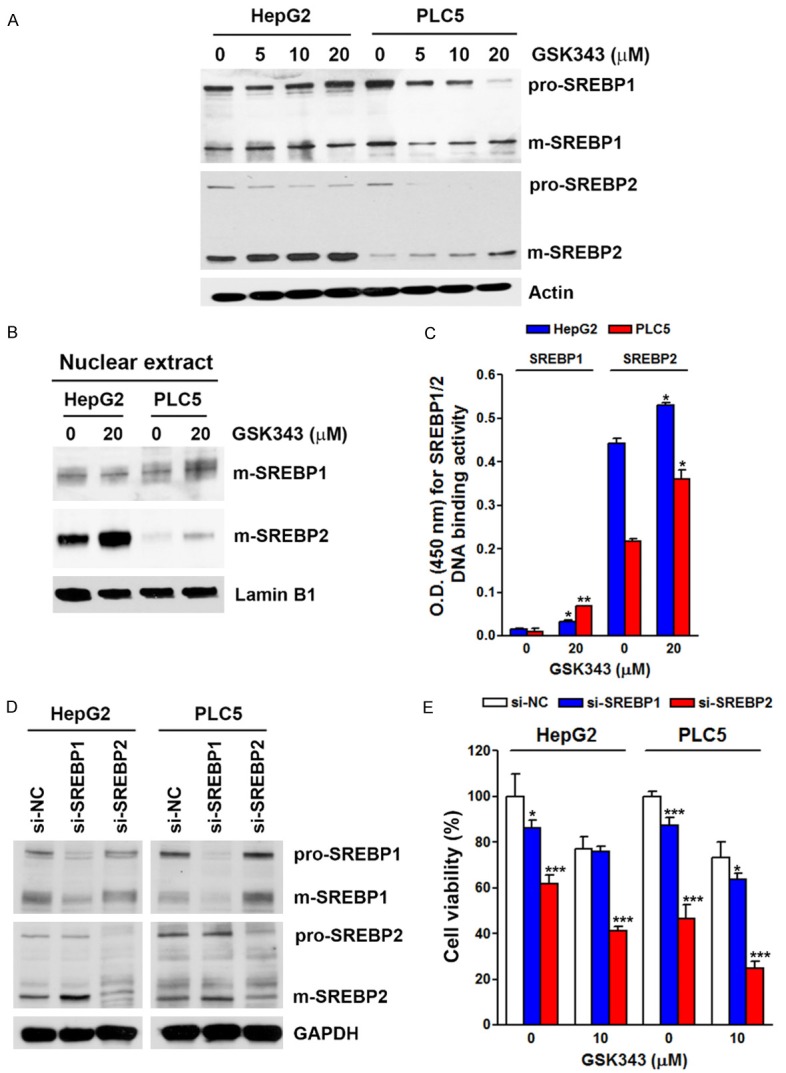

To investigate whether SREBP signaling pathways were activated by GSK343, the processing of SREBP1/2 precursors to their mature forms was examined by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 2A, GSK343 increased the level of mature SREBP2, but not SREBP1, in both HepG2 and PLC5 cells. Although the expression of SREBP1 precursor in PLC5 cells was reduced by GSK343, no increase of mature SREBP1 was observed. To confirm the activation of SREBP2, the nuclear localization and DNA binding activity of SREBP1/2 were examined. Consistently, GSK343 increased nuclear level and DNA binding ability of SREBP2, but not SREBP1, in HepG2 and PLC5 cells (Figure 2B and 2C). To investigate the role of SREBP1/2 in the GSK343-induced cytotoxicity, the expression of SREBP1/2 was knocked down by siRNAs (Figure 2D). Compared to the consequence of SREBP1 knockdown, inhibition of SREBP2 had higher cytotoxicity and could enhance the anticancer activity of GSK343 in HepG2 and PLC5 cells (Figure 2E). Therefore, GSK343 activates SREBP2 signaling pathway, which protects cancer cells against the cytotoxicity of GSK343.

Figure 2.

Effect of GSK343 on SREBP processing. A. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with 0~20 μM GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. B. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with 20 μM GSK343 for 6 h. The nuclear lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. C. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with 20 μM GSK343 for 6 h. The nuclear lysates were subjected to SREBP1/2 DNA binding activity assay. P < 0.05 (*) or P < 0.01 (**) indicates significant differences between GSK343-treated and untreated cells. D. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were transfected with SREBP1/2 siRNAs for 3 days. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. E. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were transfected with SREBP1/2 siRNAs and then exposed to 10 μM GSK343 for 72 h. Cell viability was measured by MTS assay. P < 0.05 (*) or P < 0.001 (***) indicates significant differences between siRNA-transfected and untransfected cells.

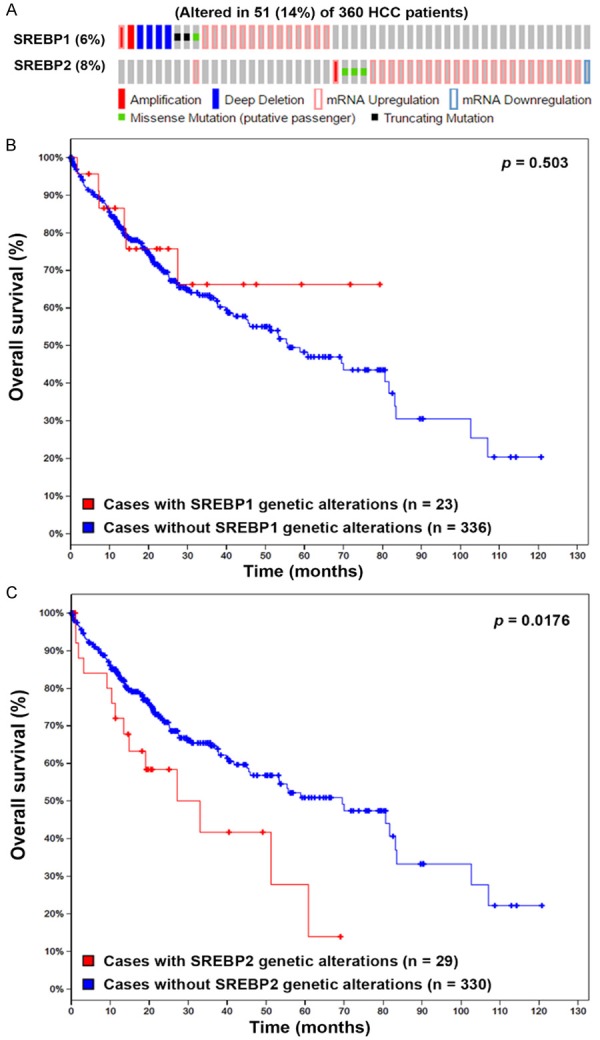

To investigate the clinical impacts of SREBP1/2 on HCC patient, cancer genomics analysis was performed using the cBioPortal online tool (http://www.cbioportal.org/) [31,32]. As shown in Figure 3A, upregulation of SREBP1/2 mRNA was the major type of genetic alterations in HCC. Interestingly, patients with genetic alterations of SREBP2 (P = 0.00176), but not SREBP1 (P = 0.503), had shorter overall survival (Figure 3B and 3C). Therefore, inhibition of SREBP2 in combination with GSK343 may provide clinical benefit for HCC patients.

Figure 3.

Cancer genomics analysis of SREBP1/2 in HCC. The genetic alterations of SREBP1/2 in HCC were analyzed by the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org/). The genetic alterations of SREBP1/2 were shown as an OncoPrint (A). The impacts of SREBP1 (B) and SREBP2 (C) on the overall survival of HCC patients were shown as Kaplan-Meier plot.

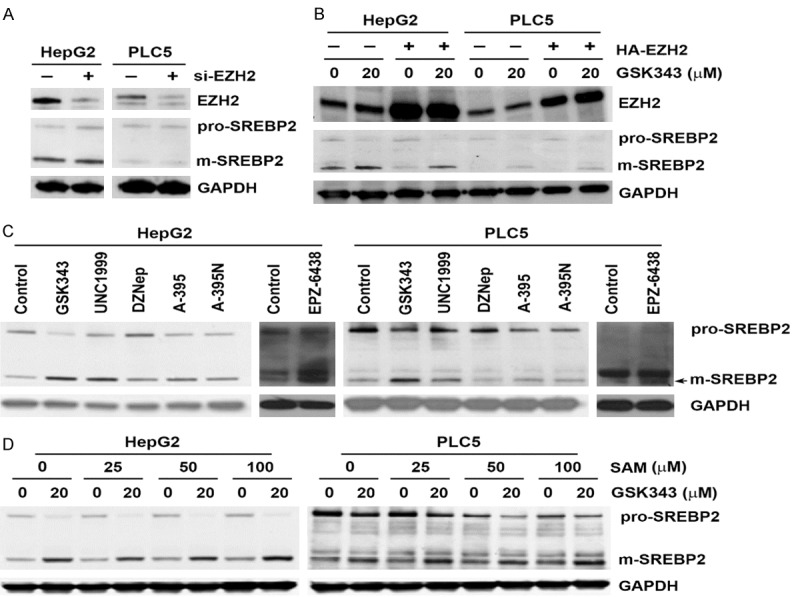

EZH2 inhibition and SAM competition are not involved in GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing

To investigation whether GSK343 activated SREBP2 through the inhibition of EZH2, HepG2 and PLC5 cells were transfected with EZH2 siRNA to knockdown EZH2 expression (Figure 4A). However, EZH2 knockdown did not induce SREBP2 processing (Figure 4A). Consistently, overexpression of EZH2 did not suppress GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing (Figure 4B). In addition, cells were treated with various types of EZH2 inhibitors to compare their abilities to activate SREBP2, including SAM-competitive inhibitors (GSK343, UNC1999, and EPZ-6438), SAH inhibitor (DZNep), EZH2-EED disruptor (A395), and the inactive analog of A395 (A395N). As shown in Figure 4C, only SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors could induce SREBP2 processing. Therefore, these results suggesting that inhibition of EZH2 is not responsible for GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation. To investigate whether SAM competition was involved in GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing, cells were supplemented with exogenous SAM, and then exposed to GSK343. However, SAM supplements were not able to reverse GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing (Figure 4D), suggesting that SAM competition is not responsible for GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation.

Figure 4.

Role of EZH2 inhibition and SAM supplementation in GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation. A. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were transfected with EZH2 siRNAs for 3 days. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. B. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with various EZH2 inhibitors for 6 h. A-395N is an inactive structural analog of A-395. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. C. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with various concentration for SAM for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. D. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with GSK343 (20 μM), UNC1999 (10 μM), DNZep (20 μM), A-395 (5 μM), A-395N (5 μM), and EPZ-6438 (5 μM) for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting.

GSK343 induces SREBP2 activation in a S1P-dependent manner

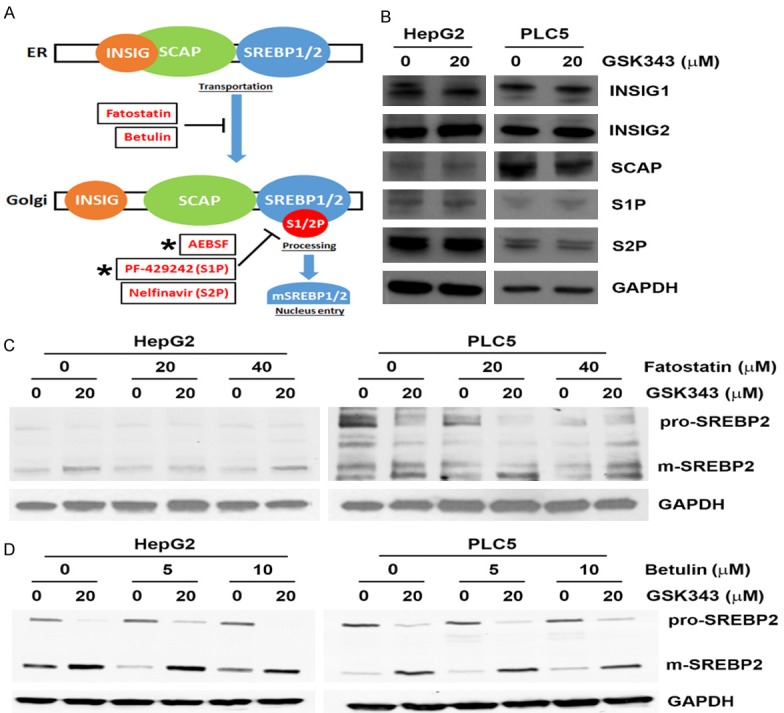

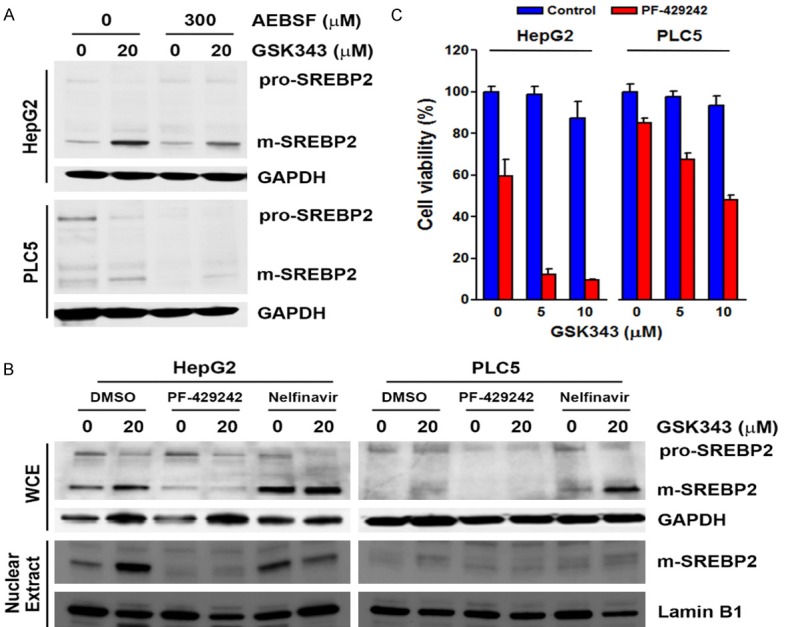

Because SREBP activation involves multiple steps, we further dissected how GSK343 activated SREBP2 using specific chemical inhibitors (Figure 5A). We first ascertain that GSK343 did not alter the expression levels of protein involved in SREBP pathways, including INSIG1/2, SCAP, S1P, and S2P (Figure 5B). Fatostatin inhibits the ER-Golgi translocation of SREBP1/2 through binding to SCAP at a distinct site from the sterol-binding domain [33]. Botulin inhibits SREBP1/2 maturation by inducing interaction of SCAP and INSIG1/2 [34]. Fatostatin and botulin did not affect GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing (Figure 5C and 5D). AEBSF, a serine protease inhibitor used to inhibit both S1P and S2P, attenuated GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing (Figure 6A). To clarify which protease was responsible for GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing, specific S1P (PF-429242) and S2P (Nelfinavir) inhibitors were used [35,36]. As shown in Figure 6B, PF-429242, but not Nelfinavir, suppressed GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing, suggesting that S1P, but not S2P, is required for GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing. To investigate whether inhibition of S1P/SREBP2 by PF-429242 could potentiate the anticancer activity of GSK343, cells were treated with GSK343 with or without PF-429242, and then MTT assay was performed. As shown in Figure 6C, synergistic anticancer activity was found by PF-429242 and GSK343. Therefore, these results indicate that GSK343 induces S1P-dependent SREBP2 activation.

Figure 5.

Effect of fatostatin and betulin on GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing. (A) A cartoon for SREBP processing and the stage-dependent inhibitors. (B) HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. (C and D) HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with fatostatin (C) or betulin (D) for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting.

Figure 6.

Effect of S1P and S2P inhibitors on GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing. A. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with AEBSF for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. B. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with PF-429242 or Nelfinavir for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. C. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with GSK343 with or without 10 μM PF-429242 for 72 h. Cell viability was analyzed by MTS assay.

Activation of p38α is involved in GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation

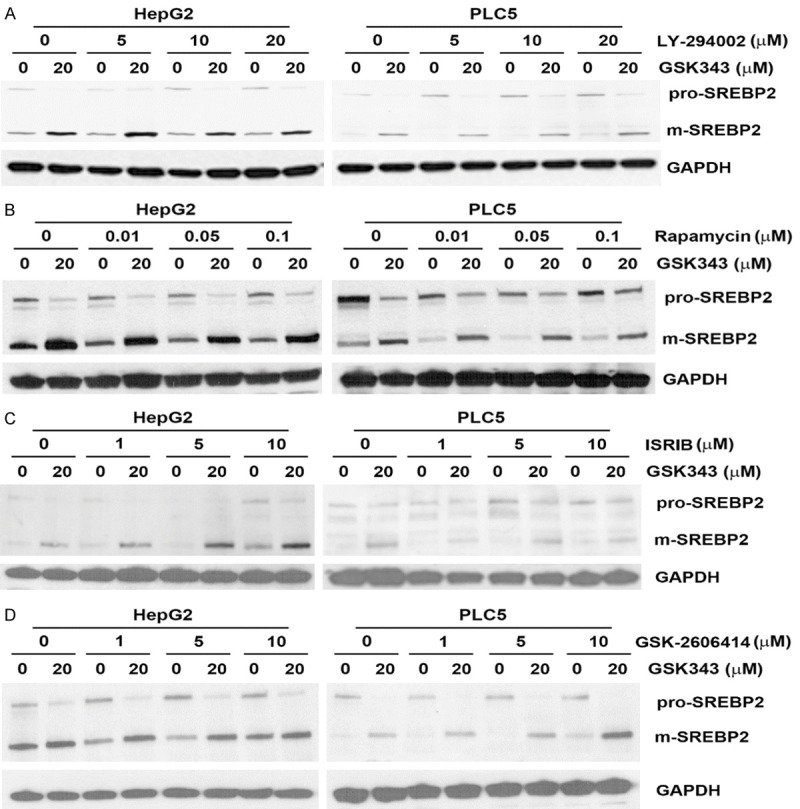

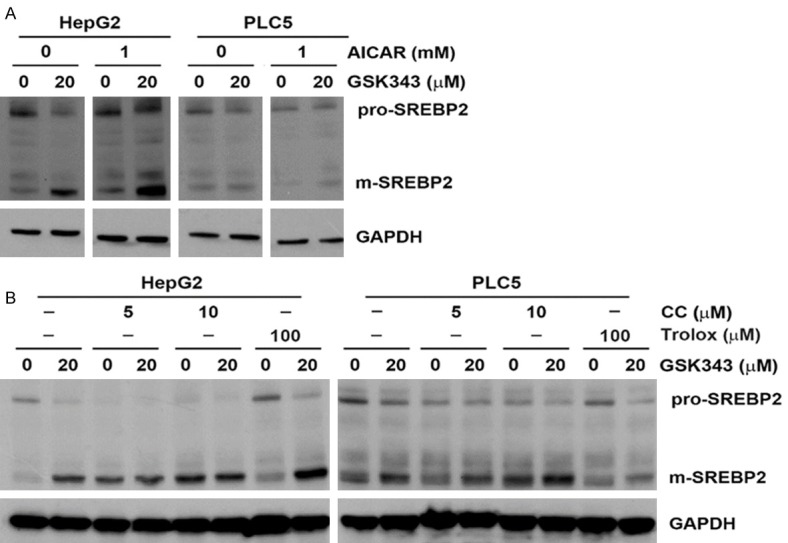

To further explore the potential upstream mechanisms involved in GSK343-induced S1P/SREBP2 activation, we searched literatures and found that various signaling pathways can modulate SREBP activity, including AKT/mTOR [37], ER stress [38], and reactive oxidative species (ROS) [39] can activate SREBP1 or SREBP2. In contrast, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a negative regulator of SREBP activation [40]. Therefore, chemicals targeting to these signaling pathways were used, including LY-294002 (AKT inhibitor), rapamycin (mTOR inhibitor), ISRIB (ER stress/ATF4 inhibitor), GSK-2606414 (ER stress/PERK inhibitor), Trolox (antioxidant/vitamin E analog), AICAR (AMPK activator), and compound C (AMPK inhibitor). As shown in Figures 7 and 8, inhibition of AKT, mTOR, ER stress, and ROS did not prevent GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing. Inhibition of AMPK by compound C was sufficient to induce SREBP2 processing, suggesting a negative role of AMPK. However, activation of AMPK by AICAR did not affect GSK343-induced SREBP2.

Figure 7.

Effect of AKT, mTOR, and ER stress inhibitors on GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with LY-294002 (A), rapamycin (B), ISRIB (C), or GSK-2606414 (D) for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting.

Figure 8.

Effect of AMPK modulators and ROS inhibitors on GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with AICAR (A), compound C (CC) (B), or trolox (B) for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting.

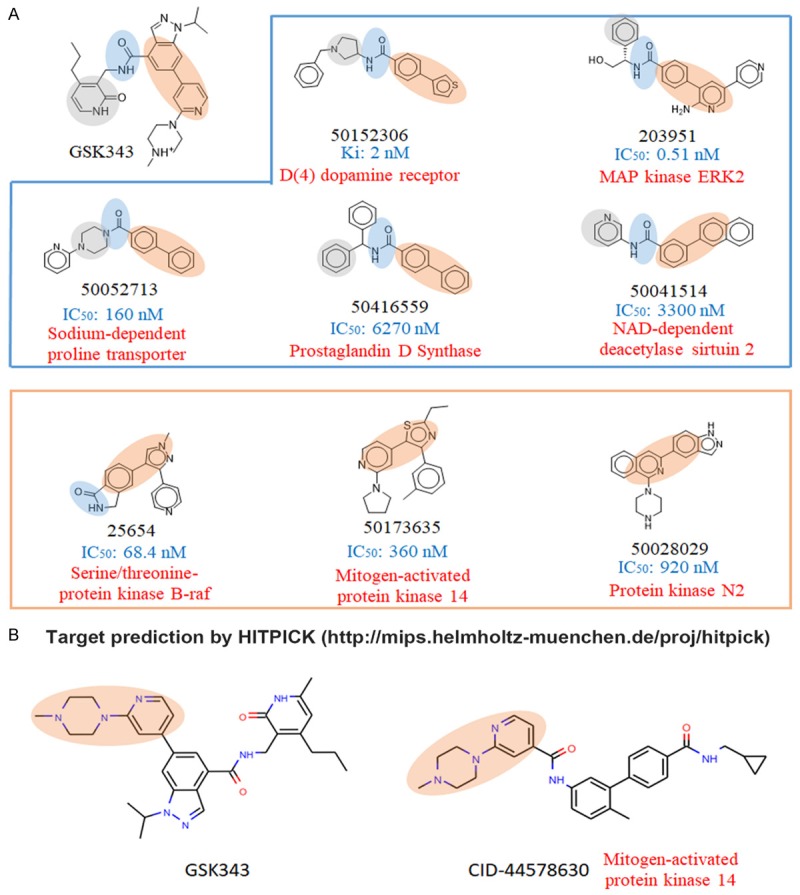

To predict the action mechanism of GSK343, we compared the whole- or sub-structures of GSK343 with other compounds with known targets. As shown in Table 5, whole-structure comparison indicated that GSK343 was mostly similar to inhibitors of p38α, coagulation factor X, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor, and luciferin 4-monooxygenase. Sub-structure comparison also found that GSK343 was similar to a compound (BDBM50173635) that can inhibit p38α (Figure 9A). In addition, we also predict GSK343’s target by using an online tool, HitPick (http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/proj/hitpick) [41]. Interestingly, the result (Figure 9B) also predicted p38α as a target of GSK343 based on its similarity to a compound (CID-44578630). Therefore, we will further investigate the role of p38α in GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation.

Table 5.

Top-5 drug targets for compounds similar to GSK343 based on whole-structure comparison

| Rank | Target | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | EZH2 | Histone-lysine_N-methyltransferase_EZH2 |

| 2 | MAPK14 | MAP_kinase_p38_alpha |

| 3 | F10 | Coagulation_factor_X |

| 4 | GLP1R | Glucagon-like_peptide_1_receptor |

| 5 | NA | Luciferin_4-monooxygenase |

Figure 9.

Prediction of GSK343 targets by structural similarity comparison. A. Three sub-structures (highlighted in different colors) were used to compare with other compounds to identify similar compounds to GSK343. Drug structures and their accessing numbers in the Binding Database (https://www.bindingdb.org/) were shown. The corresponding targets and the activity (IC50 or Ki values) of each compound were indicated. B. Target prediction was performed using an online tool, HitPick (http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/hitpick/).

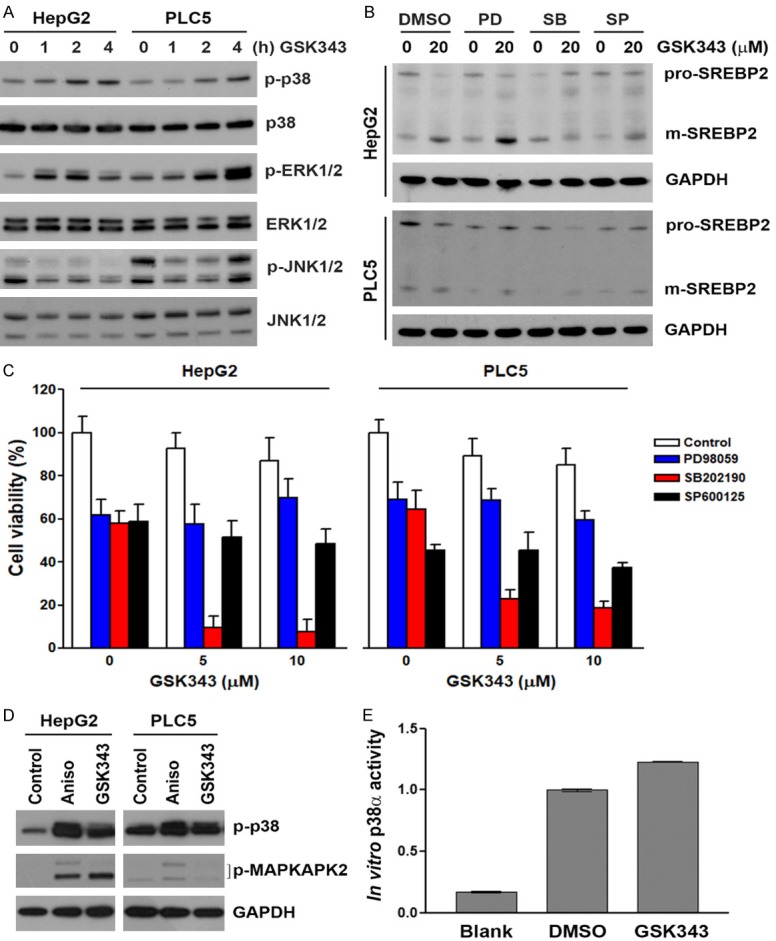

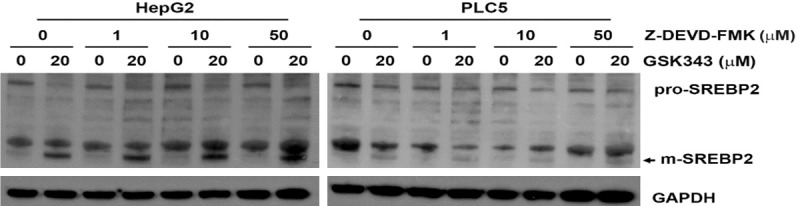

Because p38 belongs to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family with extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), we first examined the effect of GSK343 on MAPK activity based on their phosphorylation. To our surprise, GSK343 time-dependently induced phosphorylation of p38α and ERK1/2, but inhibited that of JNK1/2 (Figure 10A), suggesting that GSK343 activated p38α and ERK1/2 and suppressed JNK1/2 activity. Thus, the inhibitors of 38α (SB202190), ERK1/2 (PD98059), and JNK1/2 (SP600125) were used. As shown in Figure 10B, SB202190 inhibited GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing. In addition, inhibition of p38α enhanced the cytotoxicity of GSK343 in HepG2 and PLC5 cells (Figure 10C), which was similar to the effect of PF-429242 (Figure 6C). To ascertain the activation of p38α by GSK343, the phosphorylation of its substrate, MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAPK2), was examined by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 10D, GSK343 induced the phosphorylation of MAPKAPK2, as the p38 activator (anisomycin) did. In vitro p38α activity assay was also performed and found that GSK343 activated p38α (Figure 10E). Therefore, these results suggest that GSK343 activates SREBP2 in a p38α-dependent manner. A previous study has found that p38 could activate caspase-3 that cleaves and activates SREBP2 [42]. However, we showed that a caspase-3 inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK, did not alter GSK343-induced SREBP2 processing (Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Role of MAPK in GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation. A. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with 20 μM GSK343 for the indicated time intervals. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting. B. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with 20 μM of PD98059, SB202190, or SP600125 for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting. C. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated GSK343 with or without 10 μM of PD98059, SB202190, or SP600125 for 72 h. Cell viability was analyzed by MTS assay. D. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were treated with 20 μM GSK343 or 50 ng/mL anisomycin (Aniso) for 0.5 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting. E. HepG2 cells were treated with DMSO or 20 μM GSK343 for 2 h. The cell lysates were analyzed by in vitro p38 MAPK activity assay. Blank without the addition of cell lysates was performed as a negative control.

Figure 11.

Effect of caspase-3 inhibitor on GSK343-induced SREBP2 activation. HepG2 and PLC5 cells were pretreated with Z-DEVD-FMK for 1 h and then exposed to GSK343 for 6 h. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting.

Discussion

This study identified a novel activity of SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors to activate p38α- and S1P-dependent SREBP2 signaling pathway, which may become an obstacle to treat cancers in the future. However, we also identified that pharmacological intervention of this pathway could enhance the anticancer activity of the SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors, thereby creating a druggable vulnerability. Therefore, development of combination therapy using SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors with S1P/SREBP2 inhibitors or novel SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors without the activation of S1P/SREBP2 signaling pathway would be a promising anticancer strategy.

Although the anticancer activity of SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors has been demonstrated in different genetically defined hematologic and solid tumors, especially for those with EZH2-activating mutations [22], their effects on HCC are still unclear. Knockdown of EZH2 by lentivirus-mediated RNA interference inhibits HCC growth in a mouse model [43], providing the first hint for using pharmacological EZH2 inhibitors to treat HCC. Later, an EZH2 inhibitor, DZNep, is found to inhibit tumor-initiating HCC cells [44]. Our previous study also shows that GSK343 induces autophagic cell death in HCC cells [26]. Interestingly, EZH2 inhibition may also involve in the anticancer activity of sorafenib, an approved multikinase inhibitor for treating HCC. For example, we and other group demonstrate that sorafenib inhibits EZH2 expression and inhibition of EZH2 promotes the anticancer activity of sorafenib in HCC [26,45]. These findings highlight the potential application of EZH2 inhibition for HCC cancer therapy.

The SREBP protein family is responsible for sensing nutrient levels and regulating genes related to lipid metabolism. However, SREBP1 isoforms (SREBP1a and SREBP1c) preferentially control genes regulating fatty acid, phospholipid, and triacylglycerol biosyntheses, whereas SREBP2 prefers to control genes for cholesterol biosynthesis [46,47]. Our results highlighted the essential role of SREBP2, but not SREBP1, in HCC, implying that alteration of cholesterol homeostasis during HCC development. Consistently, a recent proteomics study has demonstrated that key proteins related to cholesterol homeostasis, including sterol O-acyltransferase 1 (SOAT1), SCAP, SREBP2, low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR), cytochrome P450 family 7 subfamily A member 1 (CYP7A1), and NPC intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 (NPC1), are significantly upregulated in early-stage HCC [48].

We identified that GSK343 activated p38α. It is controversial that EZH2 can promote p38 activation via binding with phospho-p38, together with the core members of PRC2, EED and SUZ12 in breast cancer cells [49]. In addition, p38 can phosphorylate EZH2 at Thr367 to execute PRC2-dependent and PRC2-independent functions [50,51]. Although inhibition of EZH2 expression by shRNA and DZNep could suppress p38 phosphorylation, the effect of SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors on p38 activity is not investigated yet in these studies [49,52]. Given the fact that SAM-competitive EZH2 inhibitors did not reduce the level of EZH2, we hypothesize that GSK343 may block the interaction between EZH2 and p38α without losing the phosphorylated p38α.

Materials and methods

Materials

DMEM medium, L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, and antibiotic-antimycotic solution (penicillin G, streptomycin and amphotericin B), and Lipofectamine 3000 and RNAiMAX transfection reagents were purchased from Life Technologies. Fetal bovine serum was purchased from GIBCO. SREBP1 and SREBP2 antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. Lamin B1 and INSIG2 antibodies were purchased from ProteinTech. INSIG1 antibody was purchased from Abcam. EZH2 and GAPDH antibodies were purchased form GeneTex. SCAP antibody was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories. S2P, phospho-MAPK family antibody sampler kit, and phospho-Thr334-MAPKAPK2 antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Oil Red O lipid staining kit, S1P antibody, S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM), LY-294002, oleic acid (OA), Trolox, AICAR, anisomycin, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma. GSK343, PF-429242, Nelfinavir, compound C, PD98059, SB202190, SP600125, and EPZ-6438 were purchased from Adooq BioScience. Betulin was purchased from Millipore. UNC1999, DZNep, rapamycin, fatostatin, AEBSF, and SREBP1 and SREBP2 transcription factor assay kits were purchased from Cayman Chemical. ISRIB was purchased from Tocris Bioscience. Z-DEVD-FMK was purchased from R&D Systems. GSK-2606414 was purchased from ApexBio Technology. A-395 and A-395N were kindly provided by Structural Genomics Consortium. Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails were purchased from Roche. HepG2 and PLC/PRF/5 (PLC5) cells were purchased from the Bioresources Collection and Research Center in Taiwan. Human EZH2-encoding plasmid (pCMV-EZH2) and its control vector (pCMV) were purchased from Addgene. M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent and TRIzol reagent were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. Nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit was purchased from BioVision.

Cell culture

Cells were cultured at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% L-glutamine, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution, and incubated in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2.

Cell viability assay

Cells were cultured in 96-well plates and treated with drugs before the addition of 0.5 mg/mL MTT for 4 h. After incubation, the blue MTT formazan precipitates were dissolved in 200 μL DMSO. The absorbance at 550 nm was then measured on a multiwell plate reader.

Oil Red O (ORO) staining

After treatment, cells were washed twice by PBS and fixed by 10% formalin for 30 min. After fixation, cells were pre-incubated with 60% isopropanol for 5 min and then stained with ORO working solution for 20 min. After washing with water 2-5 times, cells were counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min. Then, cells were washed 2-5 times with water. Cell morphology was observed under microscope. To quantify ORO staining levels, 100% isopropanol was added to each sample and then the absorbance at 492 nm was measured on a multiwell plate reader.

SREBP1/2 transcriptional activity assay

Nuclear lysates with or without GSK343 treatment were prepared using the nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In vitro SREBP1 and SREBP2 transcriptional activity was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

p38 MAPK activity assay

Whole cell lysates with or without GSK343 treatment were prepared using the M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent. In vitro p38 MAPK activity assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transient transfection

For transient EZH2 overexpression, cells were transfected with human EZH2-overexpressing plasmid (pCMV-EZH2) and its control vector (pCMV) by Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For transient EZH2 siRNA knockdown analysis, cells were reversely transfected with human EZH2 and control siRNAs by RNAiMAX transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot analysis

After drug treatment, total cell lysates were prepared using the M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent. Western blot was performed as previously [26].

Microarray analysis and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent. The mRNA expression was profiled using the Human OneArray Plus (Phalanx Biotech, Hsinchu, Taiwan). Results were deposited in NCBI GEO database (GSE129204). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the 50 cancer hallmarks from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) v6.2 was performed with default parameter setting using the GSEA v3.0 software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/) [27-30].

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations of samples were calculated from the numerical data (at least three replica) generated in this study. Data were analyzed using Student’s t test. p values < 0.05 (*) were considered significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology [grant number MOST105-2314-B-195-009-MY3] and the Mackay Memorial Hospital [grant numbers MMH-107-13; MMH108-12; MMH-108-086]. This work was also financially supported by the “TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine” from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts LR, Gores GJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular pathways and new therapeutic targets. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25:212–225. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Haussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V, Gerolami R, Masi G, Ross PJ, Song T, Bronowicki JP, Ollivier-Hourmand I, Kudo M, Cheng AL, Llovet JM, Finn RS, LeBerre MA, Baumhauer A, Meinhardt G, Han G RESORCE Investigators. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo BY, Cicin I, Merle P, Chen Y, Park JW, Blanc JF, Bolondi L, Klumpen HJ, Chan SL, Zagonel V, Pressiani T, Ryu MH, Venook AP, Hessel C, Borgman-Hagey AE, Schwab G, Kelley RK. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron A, Park JW, Han G, Jassem J, Blanc JF, Vogel A, Komov D, Evans TRJ, Lopez C, Dutcus C, Guo M, Saito K, Kraljevic S, Tamai T, Ren M, Cheng AL. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391:1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, Xu J, Sun Y, Liang H, Liu J, Wang J, Tak WY, Pan H, Burock K, Zou J, Voliotis D, Guan Z. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, Shen R, Ota I, Tomlins SA, Ghosh D, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Hayes DF, Sabel MS, Livant D, Weiss SJ, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11606–11611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1933744100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, Ghosh D, Pienta KJ, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, Rubin MA, Chinnaiyan AM. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624–629. doi: 10.1038/nature01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Vlag J, Otte AP. Transcriptional repression mediated by the human polycomb-group protein EED involves histone deacetylation. Nat Genet. 1999;23:474–478. doi: 10.1038/70602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raaphorst FM, Meijer CJ, Fieret E, Blokzijl T, Mommers E, Buerger H, Packeisen J, Sewalt RA, Otte AP, van Diest PJ. Poorly differentiated breast carcinoma is associated with increased expression of the human polycomb group EZH2 gene. Neoplasia. 2003;5:481–488. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(03)80032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breuer RH, Snijders PJ, Smit EF, Sutedja TG, Sewalt RG, Otte AP, van Kemenade FJ, Postmus PE, Meijer CJ, Raaphorst FM. Increased expression of the EZH2 polycomb group gene in BMI-1-positive neoplastic cells during bronchial carcinogenesis. Neoplasia. 2004;6:736–743. doi: 10.1593/neo.04160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croonquist PA, Van Ness B. The polycomb group protein enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH 2) is an oncogene that influences myeloma cell growth and the mutant ras phenotype. Oncogene. 2005;24:6269–6280. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan J, Yang X, Zhuang L, Jiang X, Chen W, Lee PL, Karuturi RK, Tan PB, Liu ET, Yu Q. Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb-repressive complex 2-mediated gene repression selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1050–1063. doi: 10.1101/gad.1524107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan JZ, Yan Y, Wang XX, Jiang Y, Xu HE. EZH2: biology, disease, and structure-based drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014;35:161–174. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knutson SK, Wigle TJ, Warholic NM, Sneeringer CJ, Allain CJ, Klaus CR, Sacks JD, Raimondi A, Majer CR, Song J, Scott MP, Jin L, Smith JJ, Olhava EJ, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Richon VM, Copeland RA, Keilhack H, Pollock RM, Kuntz KW. A selective inhibitor of EZH2 blocks H3K27 methylation and kills mutant lymphoma cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:890–896. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, Korenchuk S, Thompson C, Van Aller GS, Liu Y, Graves AP, Della Pietra A 3rd, Diaz E, LaFrance LV, Mellinger M, Duquenne C, Tian X, Kruger RG, McHugh CF, Brandt M, Miller WH, Dhanak D, Verma SK, Tummino PJ, Creasy CL. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012;492:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi W, Chan H, Teng L, Li L, Chuai S, Zhang R, Zeng J, Li M, Fan H, Lin Y, Gu J, Ardayfio O, Zhang JH, Yan X, Fang J, Mi Y, Zhang M, Zhou T, Feng G, Chen Z, Li G, Yang T, Zhao K, Liu X, Yu Z, Lu CX, Atadja P, Li E. Selective inhibition of Ezh2 by a small molecule inhibitor blocks tumor cells proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:21360–21365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210371110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma SK, Tian X, LaFrance LV, Duquenne C, Suarez DP, Newlander KA, Romeril SP, Burgess JL, Grant SW, Brackley JA, Graves AP, Scherzer DA, Shu A, Thompson C, Ott HM, Aller GSV, Machutta CA, Diaz E, Jiang Y, Johnson NW, Knight SD, Kruger RG, McCabe MT, Dhanak D, Tummino PJ, Creasy CL, Miller WH. Identification of potent, selective, cell-active inhibitors of the histone lysine methyltransferase EZH2. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:1091–1096. doi: 10.1021/ml3003346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knutson SK, Warholic NM, Wigle TJ, Klaus CR, Allain CJ, Raimondi A, Porter Scott M, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Copeland RA, Richon VM, Pollock RM, Kuntz KW, Keilhack H. Durable tumor regression in genetically altered malignant rhabdoid tumors by inhibition of methyltransferase EZH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7922–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303800110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaswani RG, Gehling VS, Dakin LA, Cook AS, Nasveschuk CG, Duplessis M, Iyer P, Balasubramanian S, Zhao F, Good AC, Campbell R, Lee C, Cantone N, Cummings RT, Normant E, Bellon SF, Albrecht BK, Harmange JC, Trojer P, Audia JE, Zhang Y, Justin N, Chen S, Wilson JR, Gamblin SJ. Identification of (R)-N-((4-Methoxy-6-methyl-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridin-3-yl)methyl)-2-methyl-1-(1-(1 -(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)piperidin-4-yl)ethyl)-1H-indole-3-carboxamide (CPI-1205), a potent and selective inhibitor of histone methyltransferase EZH2, suitable for phase i clinical trials for B-cell lymphomas. J Med Chem. 2016;59:9928–9941. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulati N, Beguelin W, Giulino-Roth L. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitors. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018;59:1574–1585. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1430795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Italiano A, Soria JC, Toulmonde M, Michot JM, Lucchesi C, Varga A, Coindre JM, Blakemore SJ, Clawson A, Suttle B, McDonald AA, Woodruff M, Ribich S, Hedrick E, Keilhack H, Thomson B, Owa T, Copeland RA, Ho PTC, Ribrag V. Tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:649–659. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawson RB. The SREBP pathway--insights from Insigs and insects. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:631–640. doi: 10.1038/nrm1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh YY, Lo HL, Yang PM. EZH2 inhibitors transcriptionally upregulate cytotoxic autophagy and cytoprotective unfolded protein response in human colorectal cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:1661–1680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu TP, Lo HL, Wei LS, Hsiao HH, Yang PM. S-Adenosyl-L-methionine-competitive inhibitors of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 induce autophagy and enhance drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2015;26:139–147. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstrale M, Laurila E, Houstis N, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Mesirov JP, Golub TR, Tamayo P, Spiegelman B, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Groop LC. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, Thorvaldsdottir H, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1739–1740. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamisuki S, Mao Q, Abu-Elheiga L, Gu Z, Kugimiya A, Kwon Y, Shinohara T, Kawazoe Y, Sato S, Asakura K, Choo HY, Sakai J, Wakil SJ, Uesugi M. A small molecule that blocks fat synthesis by inhibiting the activation of SREBP. Chem Biol. 2009;16:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang JJ, Li JG, Qi W, Qiu WW, Li PS, Li BL, Song BL. Inhibition of SREBP by a small molecule, betulin, improves hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance and reduces atherosclerotic plaques. Cell Metab. 2011;13:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawkins JL, Robbins MD, Warren LC, Xia D, Petras SF, Valentine JJ, Varghese AH, Wang IK, Subashi TA, Shelly LD, Hay BA, Landschulz KT, Geoghegan KF, Harwood HJ Jr. Pharmacologic inhibition of site 1 protease activity inhibits sterol regulatory element-binding protein processing and reduces lipogenic enzyme gene expression and lipid synthesis in cultured cells and experimental animals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:801–808. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.139626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guan M, Fousek K, Jiang C, Guo S, Synold T, Xi B, Shih CC, Chow WA. Nelfinavir induces liposarcoma apoptosis through inhibition of regulated intramembrane proteolysis of SREBP-1 and ATF6. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1796–1806. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson TR, Sengupta SS, Harris TE, Carmack AE, Kang SA, Balderas E, Guertin DA, Madden KL, Carpenter AE, Finck BN, Sabatini DM. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell. 2011;146:408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colgan SM, Tang D, Werstuck GH, Austin RC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress causes the activation of sterol regulatory element binding protein-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1843–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seo K, Shin SM. Induction of lipin1 by ROS-dependent SREBP-2 activation. Toxicol Res. 2017;33:219–224. doi: 10.5487/TR.2017.33.3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Xu S, Mihaylova MM, Zheng B, Hou X, Jiang B, Park O, Luo Z, Lefai E, Shyy JY, Gao B, Wierzbicki M, Verbeuren TJ, Shaw RJ, Cohen RA, Zang M. AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits SREBP activity to attenuate hepatic steatosis and atherosclerosis in diet-induced insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metab. 2011;13:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Vogt I, Haque T, Campillos M. HitPick: a web server for hit identification and target prediction of chemical screenings. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1910–1912. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pham DD, Do HT, Bruelle C, Kukkonen JP, Eriksson O, Mogollon I, Korhonen LT, Arumae U, Lindholm D. p75 neurotrophin receptor signaling activates sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 in hepatocyte cells via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and caspase-3. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:10747–10758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.722272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y, Lin MC, Yao H, Wang H, Zhang AQ, Yu J, Hui CK, Lau GK, He ML, Sung J, Kung HF. Lentivirus-mediated RNA interference targeting enhancer of zeste homolog 2 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth through down-regulation of stathmin. Hepatology. 2007;46:200–208. doi: 10.1002/hep.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiba T, Suzuki E, Negishi M, Saraya A, Miyagi S, Konuma T, Tanaka S, Tada M, Kanai F, Imazeki F, Iwama A, Yokosuka O. 3-Deazaneplanocin A is a promising therapeutic agent for the eradication of tumor-initiating hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2557–2567. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S, Zhu Y, He H, Liu J, Xu L, Zhang H, Liu H, Liu W, Liu Y, Pan D, Chen L, Wu Q, Xu J, Gu J. Sorafenib suppresses growth and survival of hepatoma cells by accelerating degradation of enhancer of zeste homolog 2. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:750–759. doi: 10.1111/cas.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 1997;89:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osborne TF, Espenshade PJ. Evolutionary conservation and adaptation in the mechanism that regulates SREBP action: what a long, strange tRIP it’s been. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2578–2591. doi: 10.1101/gad.1854309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang Y, Sun A, Zhao Y, Ying W, Sun H, Yang X, Xing B, Sun W, Ren L, Hu B, Li C, Zhang L, Qin G, Zhang M, Chen N, Zhang M, Huang Y, Zhou J, Zhao Y, Liu M, Zhu X, Qiu Y, Sun Y, Huang C, Yan M, Wang M, Liu W, Tian F, Xu H, Zhou J, Wu Z, Shi T, Zhu W, Qin J, Xie L, Fan J, Qian X, He F Chinese Human Proteome Project (CNHPP) Consortium. Proteomics identifies new therapeutic targets of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature. 2019;567:257–261. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0987-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore HM, Gonzalez ME, Toy KA, Cimino-Mathews A, Argani P, Kleer CG. EZH2 inhibition decreases p38 signaling and suppresses breast cancer motility and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:741–752. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2498-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anwar T, Arellano-Garcia C, Ropa J, Chen YC, Kim HS, Yoon E, Grigsby S, Basrur V, Nesvizhskii AI, Muntean A, Gonzalez ME, Kidwell KM, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Kleer CG. p38-mediated phosphorylation at T367 induces EZH2 cytoplasmic localization to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2801. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05078-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palacios D, Mozzetta C, Consalvi S, Caretti G, Saccone V, Proserpio V, Marquez VE, Valente S, Mai A, Forcales SV, Sartorelli V, Puri PL. TNF/p38alpha/polycomb signaling to Pax7 locus in satellite cells links inflammation to the epigenetic control of muscle regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:455–469. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang H, Huang Q, Liao MJ, Xu F, Zhang T, He J, Zhang L, Liu HZ. EZH2 plays a crucial role in ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury by regulating p38 signaling. Inflamm Res. 2019;68:325–336. doi: 10.1007/s00011-019-01221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]