Abstract

Quorum sensing (QS) is a mechanism allowing microorganisms to sense population density and synchronously control genes expression. It has been shown that QS supervises the activity of many processes important for microbial pathogenicity, e.g., sporulation, biofilm formation, and secretion of enzymes or membrane vesicles. This contributed to the concept of anti-QS therapy [also called quorum quenching (QQ)] and the opportunity of its application in fighting against various types of pathogens. In recent years, many published articles reported promising results indicating the possibility of reducing pathogenicity of tested microorganisms and their easier eradication when co-treated with antibiotics. The aim of the present article is to point to the opposite, negative side of the QQ therapy, with particular emphasis on three fundamental properties attributed to anti-QS substances: the selectivity, virulence reduction, and lack of resistance against QQ. This point of view may highlight new directions of research, which should be taken into account in the future before the widespread introduction of QQ therapies in the treatment of people.

Keywords: quorum sensing, quorum quenching, microbiota, pathogenicity, virulence, resistance

Introduction

Quorum sensing (QS) is a mechanism allowing microorganisms to sense population density, synchronously control genes expression after reaching a critical point (a quorum) and assess the efficiency of producing diffusible extracellular effectors. This process is associated with the synthesis of extracellular autoinductive substances with a function similar to hormones produced by higher organisms (Redfield, 2002; Hense et al., 2007; Bandara et al., 2012; Hawver et al., 2016). The first scientific report, indicating the presence of hormone-like compounds in bacteria, was an article by Tomasz (1965). In the next decade, attention was drawn to the relationship between the production of a specific group of metabolites (autoinducers) and luciferase-dependent bioluminescence in bacteria of the Vibrionaceae family (Nealson et al., 1970; Greenberg et al., 1979). A breakthrough in QS research was made by Eberhard et al. (1981), who for the first time identified the structure of signaling factors involved in the microbial communication, i.e., acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), now often named as autoinducer-1 (AI-1). In 1994, the presence of other substances controlling bioluminescence was shown (Bassler et al., 1994). They were called autoinducer-2 (AI-2), and their structure was identified at the beginning of the twenty-first century (Chen et al., 2002). In 1995, two publications were released, in which the relationship between oligopeptides synthesis [called autoinducing peptides (AIPs)] and inter-microbial communication in Gram-positive bacteria was noticed (Havarstein et al., 1995; Ji et al., 1995). AI-1, AIPs, and AI-2 are currently the most intensively investigated compounds related to the QS activity, and their presence has been demonstrated in many bacteria belonging to Gram-negative, Gram-positive, and various classes of microorganisms, respectively (Bandara et al., 2012). In the following years, the presence of other substances associated with the microbial communication was also documented, including autoinducer-3 (AI-3) (Sperandio et al., 2003), Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) (Deziel et al., 2004) and diffusible signal factors (DSFs) (Tang et al., 1991). In order to broaden the knowledge on the functioning of QS systems at the molecular level, we refer to the Hawver et al. (2016) review paper.

Quorum sensing controls the activity of many mechanisms important for the microbial physiology, including production of biofilm (Parsek and Greenberg, 2005; Dickschat, 2010), exoenzymes (Pena et al., 2019), membrane vesicles (Kulp and Kuehn, 2010; Toyofuku, 2019), siderophores (Cornelis and Aendekerk, 2004), and secondary metabolites with antimicrobial activity (Barnard et al., 2007; Kareb and Aïder, 2019), as well as induction of sporulation (Schultz et al., 2009), swarming motility (Daniels et al., 2004), and competence for horizontal gene transfer (Blokesch, 2012; Shanker and Federle, 2017). Because many of these processes are associated with virulence, there is a belief that inhibition of QS activity [also called quorum quenching (QQ)] will reduce pathogenicity and contribute to easier eradication of microorganisms. Examples of in vitro and in vivo studies showing the effectiveness of QQ substances in reducing virulence mainly include an activity of lactonase, an enzyme breaking down the lactone ring of molecules involved in QS (Fan et al., 2017; Guendouze et al., 2017; Rehman and Leiknes, 2018; Utari et al., 2018; Mion et al., 2019) and azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic with QQ properties (Nalca et al., 2006; van Delden et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2016). Currently, in silico studies are also used to search for new, promising QS inhibitors to accelerate the effectivity and reduce the costs associated with the discovery of new compounds with such properties (Mellini et al., 2019). Promising features of QQ substances are reflected in the presence of many review papers describing the possibilities resulting from the use of this type of compounds (LaSarre and Federle, 2013; Chen et al., 2018; Defoirdt, 2018; Rémy et al., 2018; Fleitas Martínez et al., 2019).

The aim of this article is to point to the opposite, negative side of the QQ therapy, with particular emphasis on three fundamental properties attributed to anti-QS substances: the selectivity, virulence reduction, and lack of resistance against QQ.

The First Objection – The Selectivity of Quorum Quenching Substances

Despite the key role of QS signals in the virulence of many pathogens, the involvement of these signaling factors in the physiological processes of microorganisms is rarely taken into account. For AI-2, participation in controlling gene expression related to metabolism (DeLisa et al., 2001; McNab et al., 2003; Shao et al., 2012; Mitra et al., 2016; Ha et al., 2018; Yadav et al., 2018), cell division, and morphogenesis (DeLisa et al., 2001; Shao et al., 2012; Yadav et al., 2018), and DNA repair (Yadav et al., 2018) has been demonstrated. Importantly, the presence of the AI-2 producing luxS system was also noticed in commensal bacteria inhabiting the human body, including Bifidobacterium (Sun et al., 2014) and Lactobacillus (Lebeer et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2017, 2018a), but also many other representatives, such as Eubacterium, Roseburia, or Ruminococcus (Lukáš et al., 2008). Signaling associated with AI-2 in these bacteria is associated with adaptation to environmental conditions, affecting biofilm formation (Rickard et al., 2006; Lebeer et al., 2007; Cuadra-Saenz et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017, 2018a) and resistance to stressors during the passage through the digestive tract (Yeo et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018a). Additionally, the luxS system is required for the synthesis of bacteriocins by Escherichia coli (Lu et al., 2017), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Miller et al., 2018), Streptococcus mutans (Merritt et al., 2005; Sztajer et al., 2008), and Lactobacillus (Jia et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019). It was observed that AI-2 produced by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans is a factor directly involved in the inhibition of both biofilm formation and transformation into the filamentous form by Candida albicans (Bachtiar et al., 2014). Similarly, the production of these signaling factors was crucial in the Ruminococcus obeum-dependent reduction of intestinal colonization by Vibrio cholerae (Hsiao et al., 2014) or Bifidobacterium-dependent protection against Salmonella infections (Christiaen et al., 2014b). Therefore, it should not be surprising that the disruption of AI-2-related signaling may have an indirect/direct effect on the ability of human microflora to adhere, form biofilms, and produce metabolites with antimicrobial activity and hence results in disturbance of microbiota homeostasis (Figure 1; Thompson et al., 2016). The use of enzymes degrading QS molecules, instead of chemicals inhibiting QS (5-fluorouracil or brominated furanones) seems to be a solution because the former show higher selectivity against targeted microorganisms (Chen et al., 2013; Guendouze et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019).

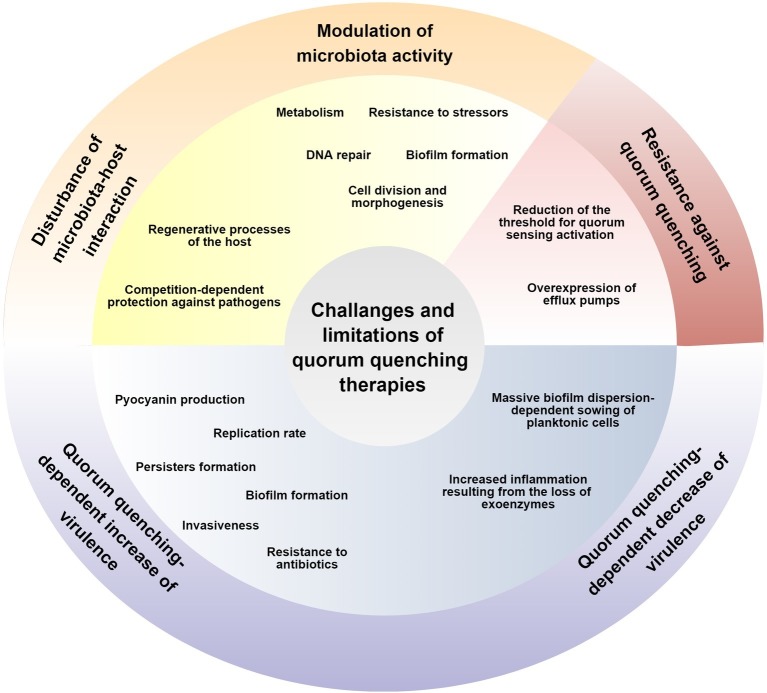

Figure 1.

Challenges and limitations of anti-QS therapies are marked by yellow, blue, and red colors for the selectivity, reduction of microbial virulence, and lack of the possibility to develop resistance mechanisms, respectively.

Thompson et al. (2015), in pioneer studies determining the effect of AI-2 on intestinal microflora of antibiotic-treated mice, showed that a modified E. coli strain producing AI-2 promoted the expansion of the Firmicutes phylum and increased the Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratio in guts. The authors of the article suggested that the use of antibiotics may most likely contribute to the destruction of microorganisms belonging to Firmicutes and create an environment with a low AI-2 concentration (Thompson et al., 2015). Other authors in their report also pointed to the beneficial, buffering effect of AI-2 on the number of Firmicutes in stool samples treated with this signaling factor (Park et al., 2016). In another study, it has been shown that lactonase has the modulating effect on the composition of biofilm and planktonic soil microorganisms. The most significant changes were observed for Stenotrophomonas and Pseudomonas (increase), as well as Clostridium cluster XIVa (decrease) (Schwab et al., 2019). Although the experiment was conducted against soil bacteria, these observations indicate the possibility of quantitative changes in microorganisms exposed to factors limiting the QS activity. Particularly, worrying is the decrease in the amount of butyrate-producing Clostridium clade XIVa, constituting about 60% of the mucosa-associated microbiota within the gut (Van den Abbeele et al., 2013). In many scientific reports, a relationship between the decrease in the number of these bacteria and the development of pro-inflammatory diseases, including cystic fibrosis (Duytschaever et al., 2013), sclerosis (Miyake et al., 2015), irritable bowel disease (Sokol et al., 2006; Imhann et al., 2018), and an increase in the amount of Enterococcus (Livanos et al., 2018) and Clostridium difficile (Antharam et al., 2013) in intestines, has been observed. Anti-QS therapies could thus adversely affect the number of Clostridium cluster XIVa and contribute to the formation of pro-inflammatory/autoimmune diseases.

The impact of QS on the human health may be associated not only with the modulation of microbiota metabolic activity but also with the direct effect of signaling factors on the host. It was determined that AHLs are chemoattractants for neutrophils (Smith et al., 2002; Zimmermann et al., 2006; Karlsson et al., 2012). In addition, many in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated the direct involvement of AHLs in inducing pro-inflammatory (Smith et al., 2002; Li et al., 2009; Grabiner et al., 2014; Curutiu et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2018) and pro-apoptotic (Schwarzer et al., 2012, 2015; Losa et al., 2015) responses in eukaryotic cells. However, in studies using the skin wound healing model, it was observed that the AHLs-dependent pro-inflammatory activity of neutrophils is associated with the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and is crucial for tissue regeneration (Nakagami et al., 2011; Kanno et al., 2013, 2016). The ability of AHLs to stimulate protective, innate immune responses was also detected in mice treated with these compounds because exposure of mice to AHLs increased their survival during infection with Aeromonas hydrophila (Khajanchi et al., 2011). For AI-2, the potential to stimulate immune cells and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-8 was also indicated (Zargar et al., 2015). On the other hand, the host can also affect the activity of the microflora. Ismail et al. (2016) observed that mammalian epithelial cells produce AI-2 mimics in response to the presence of bacteria. Because the synthesis of these molecules occurred during the destruction of tight junctions, the authors of the manuscript concluded that AI-2 mimics are probably involved in the stimulation of symbiotic microflora-dependent regenerative processes (Ismail et al., 2016). On this basis, it can be concluded that a risk of disrupting regeneration processes in the human body during anti-QS therapy may occur. This could develop by interfering with both the microflora QS activity and the AI-2 mimics-dependent host-microbiota signaling (Figure 1).

The Second Objection – The Reduction of Virulence by Quorum Quenching Substances

One of the main assumptions of anti-QS therapy is the reduction of pathogens’ virulence by limiting the communication-dependent pathogenicity induction, reviewed in Defoirdt (2018) and Fleitas Martínez et al. (2019). This effect was observed in both in vitro and in vivo animal studies (Chu et al., 2013; Jang et al., 2013; Park et al., 2014; Ryu et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018; Torabi Delshad et al., 2018). There are, however, numerous scientific reports indicating that the dysfunction of genes responsible for the QS activity determines an increase of certain pathogenicity features. Among microorganisms in which deletion of luxS (ΔluxS) increased the aggregation or/and biofilm formation are representatives of Gram-negative bacteria: Helicobacter pylori (Cole et al., 2004; Anderson et al., 2015; Sweeney et al., 2018), Vibrio cholerae (Ali and Benitez, 2009), Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Velusamy et al., 2017), Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (Li et al., 2008), and Haemophilus parasuis (Zhang et al., 2019), as well as Gram-positive: Staphylococcus aureus (Yu et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2017), Staphylococcus epidermidis (Xu et al., 2006; Xue et al., 2015), Streptococcus mutans (Huang et al., 2009; He et al., 2015), Enterococcus faecalis (He et al., 2016), and Bacillus cereus (Auger et al., 2006). In addition, ΔluxS Streptococcus pyogenes and S. aureus mutants showed an increase in survivability when incubating with macrophages (Siller et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2010). The use of anti-QS therapy could therefore promote the development of isolates with an increased survival ability and are thus more difficult to eradicate (Figure 1).

Despite the aforementioned examples, there are many microorganisms for which the presence of the luxS gene and the production of AI-2 is crucial for the formation of biofilms (McNab et al., 2003; Jesudhasan et al., 2010; Jang et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015, 2017; Laganenka et al., 2016; Jani et al., 2017; Laganenka and Sourjik, 2018). The aim of QQ therapy, in this case, would be to maintain the microorganisms in a planktonic form, more sensitive to antibiotics or immune cells’ attack (Chow et al., 2014; Christiaen et al., 2014a; Ryu et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2017; Srinivasan et al., 2017; Mayer et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018). In pioneer in vivo studies by Fleming and Rumbaugh (2018), for the first time, the effect of massive dispersion of bacteria using the mouse wound infection model was determined. It was noticed that the dispersion of biofilm resulted in the rapid release of planktonic bacteria and their sowing into the blood (Fleming and Rumbaugh, 2018). Such a scenario indicates a potential risk of developing bacteremia/sepsis as a consequence of the biofilm disruption during the QS inhibition (Figure 1).

S. aureus is one of the references, Gram-positive bacteria in studies determining the effect of QS on the physiology of bacterial cells. In addition to the aforementioned ability of AI-2 production, staphylococci has also another important QS system controlling their functioning, i.e., accessory gene regulator (Agr) (Le and Otto, 2015). In Δagr mutants, a higher biofilm production (Vuong et al., 2004; He et al., 2019) and higher degree of persister forms development, a phenotype associated with changed metabolism and resistance to many antibiotics (Xu et al., 2017), were observed (Figure 1). For Δagr mutants, an increased tendency to initiate a chronic, difficult to eradicate bacteremia was also indicated (Fowler et al., 2004; Paulander et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2017). He et al. (2019) assessed the selective pressure associated with maintaining of the Agr activity in isolates from biofilm vs. non-biofilm staphylococcal infections. It has been observed that Δagr mutants appear practically exclusively during the biofilm phase, so there is a high selective pressure to maintain the Agr system when staphylococci are present in the planktonic form. For this reason, according to the authors of the article, it seems that the use of QS inhibitors would be useful only in therapies of infections unrelated to biofilm formation (He et al., 2019). This condition, however, may be difficult to meet because it was estimated that nearly 80% of all chronic infections in the human body are associated with biofilms (Römling and Balsalobre, 2012).

P. aeruginosa, a representative of Gram-negative bacteria, is an alternative to S. aureus model microorganism in QS research. In this bacterium, two QS systems associated with the production of AHLs (Las and Rhl) are present (Lee and Zhang, 2015). In ΔlasR mutants (without an ability to detect signaling factors), a selective advantage related to the replication rate in the stationary phase (D’Argenio et al., 2007; Lujan et al., 2007), as well as the increased activity of β-lactamases (D’Argenio et al., 2007), as compared to the wild-type strain was noticed. Additionally, in a placebo-controlled trial, it has been shown that a QS-inhibiting antibiotic, azithromycin, increases the prevalence of P. aeruginosa strains with higher virulence after treatment with this drug (Köhler et al., 2010). In an in vitro study, it has been observed that ΔlasR mutants had an altered phenotype, i.e., a 4- to 12-fold higher production of pyocyanin and 1.5-fold greater motility, but had a significantly lower level of exoprotease and elastase secretion (Lujan et al., 2007). Another study found that the lower production of exoenzymes had its immunological consequences in vivo. In ΔlasR P. aeruginosa mutants, adapted to cystic fibrosis, the ability to induce more intensive host immune responses compared to the wild-type strain was observed. This mechanism was associated with an increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and neutrophils recruitment, as a result of the loss of exoenzymes-dependent cytokine degradation by P. aeruginosa ΔlasR mutants (LaFayette et al., 2015). This indicates the possibility of exacerbation of pro-inflammatory reactions at the site of ongoing infections after the use of QS inhibitors by limiting the number of microbial enzymes degrading mediators of inflammatory responses (Figure 1). On the other hand, it has been shown that oxidative stress, which could be associated with the inflammation-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species, contributes to the selection of P. aeruginosa cells having an active QS system (García-Contreras et al., 2015). Therefore, it seems that the final result may depend on the environmental conditions prevailing during the infection, the immune status of infected people, as well as the pathogenic potential of the specie/strain of the microorganism (Chugani et al., 2012; Feltner et al., 2016; Kostylev et al., 2019). A perspective article, pointing out the limitations and challenges facing the introduction of QQ therapies for treatment of P. aeruginosa, was written by García-Contreras (2016). The benefits of using QQ therapies against P. aeruginosa have been discussed in review papers by Chan et al. (2015) and Pérez-Pérez et al. (2017).

The Third Objection – The Lack of Possibility to Develop Resistance Against Quorum Quenching Therapies

Another basic assumption of anti-QS therapies, apart from the selectivity and the reduction of microbial virulence, is the lack of the possibility for microorganisms to develop resistance mechanisms against this type of treatment. This postulate was based on the ability of QS inhibitors to disrupt systems controlling the pathogenicity of microorganisms and/or the lack of bactericidal activity of these compounds (Hentzer et al., 2003; Peters et al., 2003; Rasch et al., 2004; Rasmussen et al., 2005; Lönn-Stensrud et al., 2007; Swem et al., 2009; Ng et al., 2012; Park et al., 2014). The majority of research in which above-mentioned features were indicated came before 2012, the year in which for the first time the isolation of bacteria with reduced sensitivity to QS inhibitors was demonstrated. The first study, using computer modeling, determined the possibility of developing resistance to QQ by digital microorganisms by reducing the level of signaling factors needed to activate QS processes (Beckmann et al., 2012). In the same year, Maeda et al. (2012) in in vitro studies observed that P. aeruginosa could develop resistance to QS inhibitors (in this case, brominated furanones) by mutating genes encoding efflux pumps, proteins responsible for the removal of harmful substances from cells. These observations were confirmed in subsequent experiments conducted by the same research group (García-Contreras et al., 2013b). In 2018, it was shown that horizontal gene transfer in P. aeruginosa may be associated with the spread of integrative and conjugative elements responsible for resistance to both carbapenems and azithromycin-dependent inhibition of QS (Ding et al., 2018). Thus, contrary to the prevailing opinion, there is a possibility of developing resistance to QQ therapies (Figure 1). In silico modeling seems to be one of the potential solutions limiting the spread of resistance to QQ therapies (Wei et al., 2016). The topic of resistance against QQ therapies was discussed in details in review papers by Defoirdt et al. (2010), García-Contreras et al. (2013a), Kalia et al. (2014), and Liu et al. (2018b).

Conclusion

Over 50 years have passed since the first observation indicating the ability of bacteria to produce hormone-like substances, referred to today as autoinducers. Since then, our knowledge about the universality and functions of QS in various groups of microorganisms has significantly expanded. Especially in the last two decades, thanks to the development of sophisticated genetic and microbiological techniques, scientists have been able to demonstrate the participation of QS in many key microbial processes, most of them related to pathogenicity. This dependence contributed to the concept of anti-QS therapy and the possibility of its application in fighting against various types of pathogens. This article is a voice in the discussion indicating the challenges and limitations facing such therapies. Its aim is not to lower the value of previously published papers but to point to potential new directions of research, which should be taken into account in the future before the widespread introduction of QQ therapies in the treatment of people.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed for this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. The study was supported by the Wroclaw Medical University grant No: SUB.A130.19.021. The funder had no role in the preparation of the manuscript. The publication was prepared under the project financed from the funds granted by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in the “Regional Initiative of Excellence” programme for the years 2019–2022, project number 016/RID/2018/19, the amount of funding 11 998 121.30 PLN.

References

- Ali S. A., Benitez J. A. (2009). Differential response of vibrio cholerae planktonic and biofilm cells to autoinducer 2 deficiency. Microbiol. Immunol. 53, 582–586. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2009.00161.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. K., Huang J. Y., Wreden C., Sweeney E. G., Goers J., Remington S. J., et al. (2015). Chemorepulsion from the quorum signal autoinducer-2 promotes Helicobacter pylori biofilm dispersal. MBio 6:e00379. 10.1128/mBio.00379-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antharam V. C., Li E. C., Ishmael A., Sharma A., Mai V., Rand K. H., et al. (2013). Intestinal dysbiosis and depletion of butyrogenic bacteria in Clostridium difficile infection and nosocomial diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 2884–2892. 10.1128/JCM.00845-13, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger S., Krin E., Aymerich S., Gohar M. (2006). Autoinducer 2 affects biofilm formation by Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 937–941. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.937-941.2006, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtiar E. W., Bachtiar B. M., Jarosz L. M., Amir L. R., Sunarto H., Ganin H., et al. (2014). AI-2 of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans inhibits Candida albicans biofilm formation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4:94. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00094, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara H. M. H. N., Lam O. L. T., Jin L. J., Samaranayake L. (2012). Microbial chemical signaling: a current perspective. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 38, 217–249. 10.3109/1040841X.2011.652065, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard A. M. L., Bowden S. D., Burr T., Coulthurst S. J., Monson R. E., Salmond G. P. C. (2007). Quorum sensing, virulence and secondary metabolite production in plant soft-rotting bacteria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 362, 1165–1183. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler B. L., Wright M., Silverman M. R. (1994). Multiple signalling systems controlling expression of luminescence in Vibrio harveyi sequence and function of genes encoding a second sensory pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 13, 273–286. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00422.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann B. E., Knoester D. B., Connelly B. D., Waters C. M., McKinley P. K. (2012). Evolution of resistance to quorum quenching in digital organisms. Art&Life 18, 291–310. 10.1162/artl_a_00066, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokesch M. (2012). A quorum sensing-mediated switch contributes to natural transformation of Vibrio cholerae. Mob. Genet. Elem. 2, 224–227. 10.4161/mge.22284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.-G., Liu Y.-C., Chang C.-Y. (2015). Inhibiting N-acyl-homoserine lactone synthesis and quenching pseudomonas quinolone quorum sensing to attenuate virulence. Front. Microbiol. 6:1173. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01173, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Gao Y., Chen X., Yu Z., Li X. (2013). Quorum quenching enzymes and their application in degrading signal molecules to block quorum sensing-dependent infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 17477–17500. 10.3390/ijms140917477, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Schauder S., Potier N., Van Dorsselaer A., Pelczer I., Bassler B. L., et al. (2002). Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature 415, 545–549. 10.1038/415545a, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhang L., Zhang M., Liu H., Lu P., Lin K. (2018). Quorum sensing inhibitors: a patent review (2014–2018). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 28, 849–865. 10.1080/13543776.2018.1541174, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow J. Y., Yang Y., Tay S. B., Chua K. L., Yew W. S. (2014). Disruption of biofilm formation by the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii using engineered quorum-quenching lactonases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 1802–1805. 10.1128/AAC.02410-13, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaen S. E. A., Matthijs N., Zhang X.-H., Nelis H. J., Bossier P., Coenye T. (2014a). Bacteria that inhibit quorum sensing decrease biofilm formation and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Pathog. Dis. 70, 271–279. 10.1111/2049-632X.12124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiaen S. E. A., O’Connell Motherway M., Bottacini F., Lanigan N., Casey P. G., Huys G., et al. (2014b). Autoinducer-2 plays a crucial role in gut colonization and probiotic functionality of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. PLoS One 9:e98111. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y.-Y., Nega M., Wölfle M., Plener L., Grond S., Jung K., et al. (2013). A new class of quorum quenching molecules from Staphylococcus species affects communication and growth of gram-negative bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003654. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003654, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugani S., Kim B. S., Phattarasukol S., Brittnacher M. J., Choi S. H., Harwood C. S., et al. (2012). Strain-dependent diversity in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing Regulon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2823–E2831. 10.1073/pnas.1214128109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. P., Harwood J., Lee R., She R., Guiney D. G. (2004). Characterization of monospecies biofilm formation by Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 186, 3124–3132. 10.1128/JB.186.10.3124-3132.2004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis P., Aendekerk S. (2004). A new regulator linking quorum sensing and iron uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 150, 752–756. 10.1099/mic.0.27086-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadra-Saenz G., Rao D. L., Underwood A. J., Belapure S. A., Campagna S. R., Sun Z., et al. (2012). Autoinducer-2 influences interactions amongst pioneer colonizing streptococci in oral biofilms. Microbiology 158, 1783–1795. 10.1099/mic.0.057182-0, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curutiu C., Iordache F., Lazar V., Pisoschi A. M., Pop A., Chifiriuc M. C., et al. (2018). Impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing signaling molecules on adhesion and inflammatory markers in endothelial cells. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 14, 2580–2588. 10.3762/bjoc.14.235, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Argenio D. A., Wu M., Hoffman L. R., Kulasekara H. D., Déziel E., Smith E. E., et al. (2007). Growth phenotypes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR mutants adapted to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 512–533. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05678.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R., Vanderleyden J., Michiels J. (2004). Quorum sensing and swarming migration in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28, 261–289. 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt T. (2018). Quorum-sensing systems as targets for antivirulence therapy. Trends Microbiol. 26, 313–328. 10.1016/j.tim.2017.10.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt T., Boon N., Bossier P. (2010). Can bacteria evolve resistance to quorum sensing disruption? PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000989. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000989, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisa M. P., Wu C. F., Wang L., Valdes J. J., Bentley W. E. (2001). DNA microarray-based identification of genes controlled by autoinducer 2-stimulated quorum sensing in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183, 5239–5247. 10.1128/JB.183.18.5239-5247.2001, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deziel E., Lepine F., Milot S., He J., Mindrinos M. N., Tompkins R. G., et al. (2004). Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinolines (HAQs) reveals a role for 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline in cell-to-cell communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1339–1344. 10.1073/pnas.0307694100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickschat J. S. (2010). Quorum sensing and bacterial biofilms. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 343–369. 10.1039/b804469b, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Teo J. W. P., Drautz-Moses D. I., Schuster S. C., Givskov M., Yang L. (2018). Acquisition of resistance to carbapenem and macrolide-mediated quorum sensing inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa via ICETn43716385. Commun. Biol. 1:57. 10.1038/s42003-018-0064-0, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duytschaever G., Huys G., Bekaert M., Boulanger L., De Boeck K., Vandamme P. (2013). Dysbiosis of bifidobacteria and clostridium cluster XIVa in the cystic fibrosis fecal microbiota. J. Cyst. Fibros. 12, 206–215. 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.10.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard A., Burlingame A. L., Eberhard C., Kenyon G. L., Nealson K. H., Oppenheimer N. J. (1981). Structural identification of autoinducer of Photobacterium fischeri luciferase. Biochemistry 20, 2444–2449. 10.1021/bi00512a013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X., Liang M., Wang L., Chen R., Li H., Liu X. (2017). Aii810, a novel cold-adapted N-acylhomoserine lactonase discovered in a metagenome, can strongly attenuate Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors and biofilm formation. Front. Microbiol. 8:1950. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01950, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltner J. B., Wolter D. J., Pope C. E., Groleau M.-C., Smalley N. E., Greenberg E. P., et al. (2016). LasR variant cystic fibrosis isolates reveal an adaptable quorum-sensing hierarchy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. MBio 7, e01513–e01516. 10.1128/mBio.01513-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleitas Martínez O., Rigueiras P. O., Pires Á. D. S., Porto W. F., Silva O. N., de la Fuente-Nunez C., et al. (2019). Interference with quorum-sensing signal biosynthesis as a promising therapeutic strategy against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:444. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00444, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming D., Rumbaugh K. (2018). The consequences of biofilm dispersal on the host. Sci. Rep. 8:10738. 10.1038/s41598-018-29121-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler V. G., Jr., Sakoulas G., McIntyre L. M., Meka V. G., Arbeit R. D., Cabell C. H., et al. (2004). Persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection is associated with agr dysfunction and low-level in vitro resistance to thrombin-induced platelet microbicidal protein. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 1140–1149. 10.1086/423145, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Contreras R. (2016). Is quorum sensing interference a viable alternative to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections? Front. Microbiol. 7:1454. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01454, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Contreras R., Maeda T., Wood T. K. (2013a). Resistance to quorum-quenching compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 6840–6846. 10.1128/AEM.02378-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Contreras R., Martínez-Vázquez M., Velázquez Guadarrama N., Villegas Pañeda A. G., Hashimoto T., Maeda T., et al. (2013b). Resistance to the quorum-quenching compounds brominated furanone C-30 and 5-fluorouracil in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Pathog. Dis. 68, 8–11. 10.1111/2049-632X.12039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Contreras R., Nuñez-López L., Jasso-Chávez R., Kwan B. W., Belmont J. A., Rangel-Vega A., et al. (2015). Quorum sensing enhancement of the stress response promotes resistance to quorum quenching and prevents social cheating. ISME J. 9, 115–125. 10.1038/ismej.2014.98, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabiner M. A., Fu Z., Wu T., Barry K. C., Schwarzer C., Machen T. E. (2014). Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule homoserine lactone modulates inflammatory signaling through PERK and eI-F2α. J. Immunol. 193, 1459–1467. 10.4049/jimmunol.1303437, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg E. P., Hastings J. W., Ulitzur S. (1979). Induction of luciferase synthesis in Beneckea harveyi by other marine bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 120, 87–91. 10.1007/BF00409093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guendouze A., Plener L., Bzdrenga J., Jacquet P., Rémy B., Elias M., et al. (2017). Effect of quorum quenching lactonase in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and comparison with quorum sensing inhibitors. Front. Microbiol. 8:227. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha J.-H., Hauk P., Cho K., Eo Y., Ma X., Stephens K., et al. (2018). Evidence of link between quorum sensing and sugar metabolism in Escherichia coli revealed via cocrystal structures of LsrK and HPr. Sci. Adv. 4:eaar7063. 10.1126/sciadv.aar7063, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havarstein L. S., Coomaraswamy G., Morrison D. A. (1995). An unmodified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 11140–11144. 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawver L. A., Jung S. A., Ng W.-L. (2016). Specificity and complexity in bacterial quorum-sensing systems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 738–752. 10.1093/femsre/fuw014, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Le K. Y., Khan B. A., Nguyen T. H., Hunt R. L., Bae J. S., et al. (2019). Resistance to leukocytes ties benefits of quorum sensing dysfunctionality to biofilm infection. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1114–1119. 10.1038/s41564-019-0413-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Liang J., Tang Z., Ma R., Peng H., Huang Z. (2015). Role of the luxS gene in initial biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 60–68. 10.1159/000371816, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Liang J., Zhou W., Xie Q., Tang Z., Ma R., et al. (2016). Effect of the quorum-sensing luxS gene on biofilm formation by Enterococcus faecalis. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 124, 234–240. 10.1111/eos.12269, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hense B. A., Kuttler C., Müller J., Rothballer M., Hartmann A., Kreft J.-U. (2007). Does efficiency sensing unify diffusion and quorum sensing? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 230–239. 10.1038/nrmicro1600, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentzer M., Wu H., Andersen J. B., Riedel K., Rasmussen T. B., Bagge N., et al. (2003). Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 22, 3803–3815. 10.1093/emboj/cdg366, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao A., Ahmed A. M. S., Subramanian S., Griffin N. W., Drewry L. L., Petri W. A., et al. (2014). Members of the human gut microbiota involved in recovery from vibrio cholerae infection. Nature 515, 423–426. 10.1038/nature13738, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Meric G., Liu Z., Ma R., Tang Z., Lejeune P. (2009). LuxS-based quorum-sensing signaling affects biofilm formation in Streptococcus mutans. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17, 12–19. 10.1159/000159193, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T., Song X., Zhao K., Jing J., Shen Y., Zhang X., et al. (2018). Quorum-sensing molecules N-acyl homoserine lactones inhibit Trueperella pyogenes infection in mouse model. Vet. Microbiol. 213, 89–94. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.11.029, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhann F., Vich Vila A., Bonder M. J., Fu J., Gevers D., Visschedijk M. C., et al. (2018). Interplay of host genetics and gut microbiota underlying the onset and clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 67, 108–119. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail A. S., Valastyan J. S., Bassler B. L. (2016). A host-produced autoinducer-2 mimic activates bacterial quorum sensing. Cell Host Microbe 19, 470–480. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.02.020, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.-J., Choi Y.-J., Lee S.-H., Jun H.-K., Choi B.-K. (2013). Autoinducer 2 of Fusobacterium nucleatum as a target molecule to inhibit biofilm formation of periodontopathogens. Arch. Oral Biol. 58, 17–27. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.04.016, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani S., Seely A. L., Peabody V. G. L., Jayaraman A., Manson M. D. (2017). Chemotaxis to self-generated AI-2 promotes biofilm formation in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 163, 1778–1790. 10.1099/mic.0.000567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesudhasan P. R., Cepeda M. L., Widmer K., Dowd S. E., Soni K. A., Hume M. E., et al. (2010). Transcriptome analysis of genes controlled by luxS autoinducer-2 in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7, 399–410. 10.1089/fpd.2009.0372, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G., Beavis R. C., Novick R. P. (1995). Cell density control of staphylococcal virulence mediated by an octapeptide pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 12055–12059. 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F.-F., Pang X.-H., Zhu D.-Q., Zhu Z.-T., Sun S.-R., Meng X.-C. (2017). Role of the luxS gene in bacteriocin biosynthesis by Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391: a proteomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 7:13871. 10.1038/s41598-017-13231-4, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia V. C., Wood T. K., Kumar P. (2014). Evolution of resistance to quorum-sensing inhibitors. Microb. Ecol. 68, 13–23. 10.1007/s00248-013-0316-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C. K., Kim Y. K., Jung S.-I., Park W. B., Song K.-H., Park K.-H., et al. (2017). Agr functionality affects clinical outcomes in patients with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36, 2187–2191. 10.1007/s10096-017-3044-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno E., Kawakami K., Miyairi S., Tanno H., Otomaru H., Hatanaka A., et al. (2013). Neutrophil-derived tumor necrosis factor-α contributes to acute wound healing promoted by N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Dermatol. Sci. 70, 130–138. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.01.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno E., Kawakami K., Miyairi S., Tanno H., Suzuki A., Kamimatsuno R., et al. (2016). Promotion of acute-phase skin wound healing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa C4-HSL. Int. Wound J. 13, 1325–1335. 10.1111/iwj.12523, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kareb O., Aïder M. (2019). Quorum sensing circuits in the communicating mechanisms of bacteria and its implication in the biosynthesis of bacteriocins by lactic acid bacteria: a review. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 10.1007/s12602-019-09555-4 [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson T., Musse F., Magnusson K.-E., Vikström E. (2012). N-acylhomoserine lactones are potent neutrophil chemoattractants that act via calcium mobilization and actin remodeling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 91, 15–26. 10.1189/jlb.0111034, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajanchi B. K., Kirtley M. L., Brackman S. M., Chopra A. K. (2011). Immunomodulatory and protective roles of quorum-sensing signaling molecules N-acyl homoserine lactones during infection of mice with Aeromonas hydrophila. Infect. Immun. 79, 2646–2657. 10.1128/IAI.00096-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim J., Kim Y., Oh S., Song M., Choe J. H., et al. (2018). Influences of quorum-quenching probiotic bacteria on the gut microbial community and immune function in weaning pigs. Anim. Sci. J. 89, 412–422. 10.1111/asj.12954, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler T., Perron G. G., Buckling A., van Delden C. (2010). Quorum sensing inhibition selects for virulence and cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000883. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000883, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostylev M., Kim D. Y., Smalley N. E., Salukhe I., Greenberg E. P., Dandekar A. A. (2019). Evolution of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing hierarchy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 7027–7032. 10.1073/pnas.1819796116, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulp A., Kuehn M. J. (2010). Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 163–184. 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073413, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFayette S. L., Houle D., Beaudoin T., Wojewodka G., Radzioch D., Hoffman L. R., et al. (2015). Cystic fibrosis–adapted Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing lasR mutants cause hyperinflammatory responses. Sci. Adv. 1:e1500199. 10.1126/sciadv.1500199, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganenka L., Colin R., Sourjik V. (2016). Chemotaxis towards autoinducer 2 mediates autoaggregation in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 7:12984. 10.1038/ncomms12984, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganenka L., Sourjik V. (2018). Autoinducer 2-dependent Escherichia coli biofilm formation is enhanced in a dual-species coculture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e02638–e02617. 10.1128/AEM.02638-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaSarre B., Federle M. J. (2013). Exploiting quorum sensing to confuse bacterial pathogens. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77, 73–111. 10.1128/MMBR.00046-12, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le K. Y., Otto M. (2015). Quorum-sensing regulation in staphylococci—an overview. Front. Microbiol. 6:1174. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01174, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeer S., De Keersmaecker S. C. J., Verhoeven T. L. A., Fadda A. A., Marchal K., Vanderleyden J. (2007). Functional analysis of luxS in the probiotic strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG reveals a central metabolic role important for growth and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 189, 860–871. 10.1128/JB.01394-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Zhang L. (2015). The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell 6, 26–41. 10.1007/s13238-014-0100-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Li X., Song C., Zhang Y., Wang Z., Liu Z., et al. (2017). Autoinducer-2 facilitates Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 pathogenicity in vitro and in vivo. Front. Microbiol. 8:1944. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01944, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Li X., Wang Z., Fu Y., Ai Q., Dong Y., et al. (2015). Autoinducer-2 regulates Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm formation and virulence production in a dose-dependent manner. BMC Microbiol. 15:192. 10.1186/s12866-015-0529-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Wang L., Ye L., Mao Y., Xie X., Xia C., et al. (2009). Influence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing signal molecule N-(3-oxododecanoyl) homoserine lactone on mast cells. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 198, 113–121. 10.1007/s00430-009-0111-z, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Yang X., Shi G., Chang J., Liu Z., Zeng M. (2019). Cooperation of lactic acid bacteria regulated by the AI-2/LuxS system involve in the biopreservation of refrigerated shrimp. Food Res. Int. 120, 679–687. 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.11.025, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhou R., Li T., Kang M., Wan Y., Xu Z., et al. (2008). Enhanced biofilm formation and reduced virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae luxS mutant. Microb. Pathog. 45, 192–200. 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.05.008, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Ebalunode J. O., Briggs J. M. (2019). Insights into the substrate binding specificity of quorum-quenching acylase PvdQ. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 88, 104–120. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2019.01.006, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Qin Q., Defoirdt T. (2018b). Does quorum sensing interference affect the fitness of bacterial pathogens in the real world? Environ. Microbiol. 20, 3918–3926. 10.1111/1462-2920.14446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Wu R., Zhang J., Li P. (2018a). Overexpression of luxS promotes stress resistance and biofilm formation of lactobacillus paraplantarum L-ZS9 by regulating the expression of multiple genes. Front. Microbiol. 9:2628. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Wu R., Zhang J., Shang N., Li P. (2017). D-ribose interferes with quorum sensing to inhibit biofilm formation of lactobacillus paraplantarum L-ZS9. Front. Microbiol. 8:1860. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01860, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livanos A. E., Snider E. J., Whittier S., Chong D. H., Wang T. C., Abrams J. A., et al. (2018). Rapid gastrointestinal loss of clostridial clusters IV and XIVa in the ICU associates with an expansion of gut pathogens. PLoS One 13:e0200322. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200322, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lönn-Stensrud J., Petersen F. C., Benneche T., Scheie A. A. (2007). Synthetic bromated furanone inhibits autoinducer-2-mediated communication and biofilm formation in oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 22, 340–346. 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2007.00367.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losa D., Köhler T., Bacchetta M., Saab J. B., Frieden M., van Delden C., et al. (2015). Airway epithelial cell integrity protects from cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing signals. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 53, 265–275. 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0405OC, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S.-Y., Zhao Z., Avillan J. J., Liu J., Call D. R. (2017). Autoinducer-2 quorum sensing contributes to regulation of microcin PDI in Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 8:2570. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02570, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan A. M., Moyano A. J., Segura I., Argarana C. E., Smania A. M. (2007). Quorum-sensing-deficient (lasR) mutants emerge at high frequency from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutS strain. Microbiology 153, 225–237. 10.1099/mic.0.29021-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukáš F., Gorenc G., Kopečný J. (2008). Detection of possible AI-2-mediated quorum sensing system in commensal intestinal bacteria. Folia Microbiol. 53, 221–224. 10.1007/s12223-008-0030-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., Dong B., Wang K., Cai S., Liu T., Cheng X., et al. (2017). Baicalin inhibits biofilm formation, attenuates the quorum sensing-controlled virulence and enhances Pseudomonas aeruginosa clearance in a mouse peritoneal implant infection model. PLoS One 12:e0176883. 10.1371/journal.pone.0176883, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma R., Qiu S., Jiang Q., Sun H., Xue T., Cai G., et al. (2017). AI-2 quorum sensing negatively regulates rbf expression and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 307, 257–267. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.03.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T., García-Contreras R., Pu M., Sheng L., Garcia L. R., Tomás M., et al. (2012). Quorum quenching quandary: resistance to antivirulence compounds. ISME J. 6, 493–501. 10.1038/ismej.2011.122, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer C., Muras A., Romero M., López M., Tomás M., Otero A. (2018). Multiple quorum quenching enzymes are active in the nosocomial pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC17978. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:310. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00310, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNab R., Ford S. K., El-Sabaeny A., Barbieri B., Cook G. S., Lamont R. J. (2003). LuxS-based signaling in Streptococcus gordonii: autoinducer 2 controls carbohydrate metabolism and biofilm formation with Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 185, 274–284. 10.1128/JB.185.1.274-284.2003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellini M., Di Muzio E., D’Angelo F., Baldelli V., Ferrillo S., Visca P., et al. (2019). In silico selection and experimental validation of FDA-approved drugs as anti-quorum sensing agents. Front. Microbiol. 10:2355. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt J., Kreth J., Shi W., Qi F. (2005). LuxS controls bacteriocin production in Streptococcus mutans through a novel regulatory component. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 960–969. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04733.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. L., Kjos M., Abrudan M. I., Roberts I. S., Veening J.-W., Rozen D. E. (2018). Eavesdropping and crosstalk between secreted quorum sensing peptide signals that regulate bacteriocin production in Streptococcus pneumoniae. ISME J. 12, 2363–2375. 10.1038/s41396-018-0178-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mion S., Rémy B., Plener L., Brégeon F., Chabrière E., Daudé D. (2019). Quorum quenching lactonase strengthens bacteriophage and antibiotic arsenal against Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Front. Microbiol. 10:2049. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02049, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra A., Herren C. D., Patel I. R., Coleman A., Mukhopadhyay S. (2016). Integration of AI-2 based cell-cell signaling with metabolic cues in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 11:e0157532. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157532, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake S., Kim S., Suda W., Oshima K., Nakamura M., Matsuoka T., et al. (2015). Dysbiosis in the gut microbiota of patients with multiple sclerosis, with a striking depletion of species belonging to clostridia XIVa and IV clusters. PLoS One 10:e0137429. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137429, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami G., Minematsu T., Asada M., Nagase T., Akase T., Huang L., et al. (2011). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing signal N-(3-oxododecanoyl) homoserine lactone can accelerate cutaneous wound healing through myofibroblast differentiation in rats. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 62, 157–163. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00796.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalca Y., Jänsch L., Bredenbruch F., Geffers R., Buer J., Häussler S. (2006). Quorum-sensing antagonistic activities of azithromycin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: a global approach. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 1680–1688. 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1680-1688.2006, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nealson K. H., Platt T., Hastings J. W. (1970). Cellular control of the synthesis and activity of the bacterial luminescent system. J. Bacteriol. 104, 313–322. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5473898 (Accessed July 2, 2019). PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng W.-L., Perez L., Cong J., Semmelhack M. F., Bassler B. L. (2012). Broad spectrum pro-quorum-sensing molecules as inhibitors of virulence in vibrios. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002767. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002767, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.-Y., Chong Y. P., Park H. J., Park K.-H., Moon S. M., Jeong J.-Y., et al. (2013). Agr dysfunction and persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients with removed eradicable foci. Infection 41, 111–119. 10.1007/s15010-012-0348-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Lee K., Yeo S., Shin H., Holzapfel W. (2016). “Autoinducer-2 signalling in probiotics: a mechanism of gut microbiota modulation” in Proceedings of the 2016 11th International Pipeline Conference (IPC2016), 56. Available at: http://www.probiotic-conference.net/files/AUTOINDUCERwb.pdf (Accessed June 13, 2019).

- Park H., Yeo S., Ji Y., Lee J., Yang J., Park S., et al. (2014). Autoinducer-2 associated inhibition by lactobacillus sakei NR28 reduces virulence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Food Control 45, 62–69. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.04.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsek M. R., Greenberg E. P. (2005). Sociomicrobiology: the connections between quorum sensing and biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 13, 27–33. 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.007, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulander W., Nissen Varming A., Bæk K. T., Haaber J., Frees D., Ingmer H. (2012). Antibiotic-mediated selection of quorum-sensing-negative Staphylococcus aureus. MBio 3, e00459–e00412. 10.1128/mBio.00459-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena R. T., Blasco L., Ambroa A., González-Pedrajo B., Fernández-García L., López M., et al. (2019). Relationship between quorum sensing and secretion systems. Front. Microbiol. 10:1100. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01100, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez M., Jorge P., Pérez Rodríguez G., Pereira M. O., Lourenço A. (2017). Quorum sensing inhibition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: new insights through network mining. Biofouling 33, 128–142. 10.1080/08927014.2016.1272104, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters L., König G. M., Wright A. D., Pukall R., Stackebrandt E., Eberl L., et al. (2003). Secondary metabolites of Flustra foliacea and their influence on bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 3469–3475. 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3469-3475.2003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasch M., Buch C., Austin B., Slierendrecht W. J., Ekmann K. S., Larsen J. L., et al. (2004). An inhibitor of bacterial quorum sensing reduces mortalities caused by vibriosis in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27, 350–359. 10.1078/0723-2020-00268, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen T. B., Bjarnsholt T., Skindersoe M. E., Hentzer M., Kristoffersen P., Köte M., et al. (2005). Screening for quorum-sensing inhibitors (QSI) by use of a novel genetic system, the QSI selector. J. Bacteriol. 187, 1799–1814. 10.1128/JB.187.5.1799-1814.2005, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield R. J. (2002). Is quorum sensing a side effect of diffusion sensing? Trends Microbiol. 10, 365–370. 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)02400-9, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman Z. U., Leiknes T. (2018). Quorum-quenching bacteria isolated from Red Sea sediments reduce biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 9:1354. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01354, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rémy B., Mion S., Plener L., Elias M., Chabrière E., Daudé D. (2018). Interference in bacterial quorum sensing: a biopharmaceutical perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 9:203. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00203, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard A. H., Palmer R. J., Blehert D. S., Campagna S. R., Semmelhack M. F., Egland P. G., et al. (2006). Autoinducer 2: a concentration-dependent signal for mutualistic bacterial biofilm growth. Mol. Microbiol. 60, 1446–1456. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05202.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römling U., Balsalobre C. (2012). Biofilm infections, their resilience to therapy and innovative treatment strategies. J. Intern. Med. 272, 541–561. 10.1111/joim.12004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu E.-J., Sim J., Sim J., Lee J., Choi B.-K. (2016). D-galactose as an autoinducer 2 inhibitor to control the biofilm formation of periodontopathogens. J. Microbiol. 54, 632–637. 10.1007/s12275-016-6345-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D., Wolynes P. G., Jacob E. B., Onuchic J. N. (2009). Deciding fate in adverse times: sporulation and competence in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21027–21034. 10.1073/pnas.0912185106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M., Bergonzi C., Sakkos J., Staley C., Zhang Q., Sadowsky M. J., et al. (2019). Signal disruption leads to changes in bacterial community population. Front. Microbiol. 10:611. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00611, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer C., Fu Z., Morita T., Whitt A. G., Neely A. M., Li C., et al. (2015). Paraoxonase 2 serves a proapopotic function in mouse and human cells in response to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-homoserine lactone. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 7247–7258. 10.1074/jbc.M114.620039, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer C., Fu Z., Patanwala M., Hum L., Lopez-Guzman M., Illek B., et al. (2012). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm-associated homoserine lactone C12 rapidly activates apoptosis in airway epithelia. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 698–709. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01753.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanker E., Federle M. J. (2017). Quorum sensing regulation of competence and bacteriocins in Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus mutans. Genes 8:15. 10.3390/genes8010015, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C., Shang W., Yang Z., Sun Z., Li Y., Guo J., et al. (2012). LuxS-dependent AI-2 regulates versatile functions in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J. Proteome Res. 11, 4465–4475. 10.1021/pr3002244, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller M., Janapatla R. P., Pirzada Z. A., Hassler C., Zinkl D., Charpentier E. (2008). Functional analysis of the group a streptococcal luxS/AI-2 system in metabolism, adaptation to stress and interaction with host cells. BMC Microbiol. 8:188. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-188, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. S., Harris S. G., Phipps R., Iglewski B. (2002). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule N-(3-Oxododecanoyl) homoserine lactone contributes to virulence and induces inflammation in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 184, 1132–1139. 10.1128/jb.184.4.1132-1139.2002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol H., Seksik P., Rigottier-Gois L., Lay C., Lepage P., Podglajen I., et al. (2006). Specificities of the fecal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 12, 106–111. 10.1097/01.MIB.0000200323.38139.c6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperandio V., Torres A. G., Jarvis B., Nataro J. P., Kaper J. B. (2003). Bacteria-host communication: the language of hormones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8951–8956. 10.1073/pnas.1537100100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R., Santhakumari S., Ravi A. V. (2017). In vitro antibiofilm efficacy of Piper betle against quorum sensing mediated biofilm formation of luminescent Vibrio harveyi. Microb. Pathog. 110, 232–239. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.07.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., He X., Brancaccio V. F., Yuan J., Riedel C. U. (2014). Bifidobacteria exhibit LuxS-dependent autoinducer 2 activity and biofilm formation. PLoS One 9:e88260. 10.1371/journal.pone.0088260, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney E. G., Nishida A., Weston A., Bañuelos M. S., Potter K., Conery J., et al. (2018). Agent-based modeling demonstrates how local chemotactic behavior can shape biofilm architecture. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/421610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Swem L. R., Swem D. L., O’Loughlin C. T., Gatmaitan R., Zhao B., Ulrich S. M., et al. (2009). A quorum-sensing antagonist targets both membrane-bound and cytoplasmic receptors and controls bacterial pathogenicity. Mol. Cell 35, 143–153. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.029, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztajer H., Lemme A., Vilchez R., Schulz S., Geffers R., Yip C. Y. Y., et al. (2008). Autoinducer-2-regulated genes in Streptococcus mutans UA159 and global metabolic effect of the luxS mutation. J. Bacteriol. 190, 401–415. 10.1128/JB.01086-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.-L., Liu Y.-N., Barber C. E., Dow J. M., Wootton J. C., Daniels M. J. (1991). Genetic and molecular analysis of a cluster of rpf genes involved in positive regulation of synthesis of extracellular enzymes and polysaccharide in Xanthomonas campestris pathovar campestris. MGG Mol. Gen. Genet. 226, 409–417. 10.1007/bf00260653, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. A., Oliveira R. A., Djukovic A., Ubeda C., Xavier K. B. (2015). Manipulation of the quorum sensing signal AI-2 affects the antibiotic-treated gut microbiota. Cell Rep. 10, 1861–1871. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.049, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. A., Oliveira R. A., Xavier K. B. (2016). Chemical conversations in the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 7, 163–170. 10.1080/19490976.2016.1145374, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasz A. (1965). Control of the competent state in pneumococcus by a hormone-like cell product: an example for a new type of regulatory mechanism in bacteria. Nature 208, 155–159. 10.1038/208155a0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torabi Delshad S., Soltanian S., Sharifiyazdi H., Bossier P. (2018). Effect of quorum quenching bacteria on growth, virulence factors and biofilm formation of Yersinia ruckeri in vitro and an in vivo evaluation of their probiotic effect in rainbow trout. J. Fish Dis. 41, 1429–1438. 10.1111/jfd.12840, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku M. (2019). Bacterial communication through membrane vesicles. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 83, 1599–1605. 10.1080/09168451.2019.1608809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utari P. D., Setroikromo R., Melgert B. N., Quax W. J. (2018). PvdQ quorum quenching Acylase attenuates Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in a mouse model of pulmonary infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:119. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00119, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Delden C., Köhler T., Brunner-Ferber F., François B., Carlet J., Pechère J.-C. (2012). Azithromycin to prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated pneumonia by inhibition of quorum sensing: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 38, 1118–1125. 10.1007/s00134-012-2559-3, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Abbeele P., Belzer C., Goossens M., Kleerebezem M., De Vos W. M., Thas O., et al. (2013). Butyrate-producing clostridium cluster XIVa species specifically colonize mucins in an in vitro gut model. ISME J. 7, 949–961. 10.1038/ismej.2012.158, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velusamy S. K., Sampathkumar V., Godboley D., Fine D. H. (2017). Survival of an Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans quorum sensing luxS mutant in the mouths of rhesus monkeys: insights into ecological adaptation. Mol Oral Microbiol 32, 432–442. 10.1111/omi.12184, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong C., Kocianova S., Yao Y., Carmody A. B., Otto M. (2004). Increased colonization of indwelling medical devices by quorum-sensing mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 1498–1505. 10.1086/424487, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G., Lo C., Walsh C., Hiller N. L., Marculescu R. (2016). In silico evaluation of the impacts of quorum sensing inhibition (QSI) on strain competition and development of QSI resistance. Sci. Rep. 6:35136. 10.1038/srep35136, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Li H., Vuong C., Vadyvaloo V., Wang J., Yao Y., et al. (2006). Role of the luxS quorum-sensing system in biofilm formation and virulence of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 74, 488–496. 10.1128/IAI.74.1.488-496.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T., Wang X.-Y., Cui P., Zhang Y.-M., Zhang W.-H., Zhang Y. (2017). The Agr quorum sensing system represses persister formation through regulation of phenol soluble modulins in Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 8:2189. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02189, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T., Ni J., Shang F., Chen X., Zhang M. (2015). Autoinducer-2 increases biofilm formation via an Ica- and bhp-dependent manner in Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A. Microbes Infect. 17, 345–352. 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.01.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M. K., Vidal J. E., Go Y. Y., Kim S. H., Chae S.-W., Song J.-J. (2018). The LuxS/AI-2 quorum-sensing system of Streptococcus pneumoniae is required to cause disease, and to regulate virulence- and metabolism-related genes in a rat model of middle ear infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:138. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00138, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo S., Park H., Ji Y., Park S., Yang J., Lee J., et al. (2015). Influence of gastrointestinal stress on autoinducer-2 activity of two lactobacillus species. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91:fiv065. 10.1093/femsec/fiv065, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D., Zhao L., Xue T., Sun B. (2012). Staphylococcus aureus autoinducer-2 quorum sensing decreases biofilm formation in an icaR-dependent manner. BMC Microbiol. 12:288. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-288, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Zhu X., Zhou J., Cai Z. (2018). Biofilm inhibition and pathogenicity attenuation in bacteria by Proteus mirabilis. R. Soc. Open Sci. 5:170702. 10.1098/rsos.170702, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zargar A., Quan D. N., Carter K. K., Guo M., Sintim H. O., Payne G. F., et al. (2015). Bacterial secretions of nonpathogenic Escherichia coli elicit inflammatory pathways: a closer investigation of interkingdom signaling. MBio 6:e00025. 10.1128/mBio.00025-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Zhang N., Huang B., Cai R., Wu B., E S., et al. (2016). Mechanism of azithromycin inhibition of HSL synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 6:24299. 10.1038/srep24299, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Ku X., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Chen G., Chen F., et al. (2019). The AI-2/luxS quorum sensing system affects the growth characteristics, biofilm formation, and virulence of Haemophilus parasuis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9:62. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00062, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L., Xue T., Shang F., Sun H., Sun B. (2010). Staphylococcus aureus AI-2 quorum sensing associates with the KdpDE two-component system to regulate capsular polysaccharide synthesis and virulence. Infect. Immun. 78, 3506–3515. 10.1128/IAI.00131-10, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., Zhang A., Yin H., Chu W. (2016). Bacillus sp. QSI-1 modulate quorum sensing signals reduce Aeromonas hydrophila level and Alter gut microbial community structure in fish. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6:184. 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00184, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann S., Wagner C., Müller W., Brenner-Weiss G., Hug F., Prior B., et al. (2006). Induction of neutrophil chemotaxis by the quorum-sensing molecule N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone. Infect. Immun. 74, 5687–5692. 10.1128/IAI.01940-05, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed for this study.