Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), are devastating age-associated brain disorders. Significant efforts have been made to uncover the molecular and cellular pathogenic mechanisms that underlie NDDs. However, our understanding of the neural circuit mechanisms that mediate NDDs and associated symptomatic features have been hindered by technological limitations. Our inability to identify and track individual neurons longitudinally in subcortical brain regions that are preferentially targeted in NDDs has left gaping holes in our knowledge of NDDs. Recent development and advancement of the miniature fluorescence microscope (miniscope) has opened up new avenues for examining spatially and temporally coordinated activity from hundreds of cells in deep brain structures in freely moving rodents. In the present mini-review, we examine the capabilities of current and future miniscope tools and discuss the innovative applications of miniscope imaging techniques that can push the boundaries of our understanding of neural circuit mechanisms of NDDs into new territories.

Keywords: neurodegenerative disorders, miniature fluorescence microscopy, miniscope, in vivo calcium imaging, deep brain imaging, longitudinal recording

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD), are prevalent and incredibly devastating diseases, with an estimated 6 million people affected by NDDs in the United States alone. A common risk factor for most NDDs is advancing age, and with a globally growing elderly population, the number of cases is expected to increase rapidly worldwide in the coming years. Substantial efforts have been undertaken to study NDDs, which have led to fundamental insights into these diseases. Still, the neurobiology that underlies NDDs is not well understood. With limited knowledge, therapeutic interventions have been developed to delay deterioration and provide temporary relief of symptoms, but there remains a tremendous need to improve treatments.

Although NDDs uniquely affect specific neuronal subpopulations, the accumulation of distinct protein-based macroscopic deposits that cause neuronal loss is a common hallmark of NDDs. In parallel with progressive neuronal loss, synaptic dysfunction, altered calcium homeostasis, aberrant neural activity, abnormal neuronal plasticity, and impairment in large-scale neural circuits are well-documented features of many NDDs (Palop and Mucke, 2016; Frere and Slutsky, 2018; Pchitskaya et al., 2018; Jackson et al., 2019). The interdependence between abnormal protein depositions, neuronal loss, and dysfunctional neural networks remains to be determined. Nevertheless, growing evidence suggests that many neurological deficits in NDDs may reflect functional impairment in neural circuits rather than neuronal loss (Palop et al., 2006; Seeley et al., 2009), suggesting that targeting reversible neural circuits holds therapeutic potential and deserves substantial consideration (Laxton et al., 2010; Bakker et al., 2012; Canter et al., 2016).

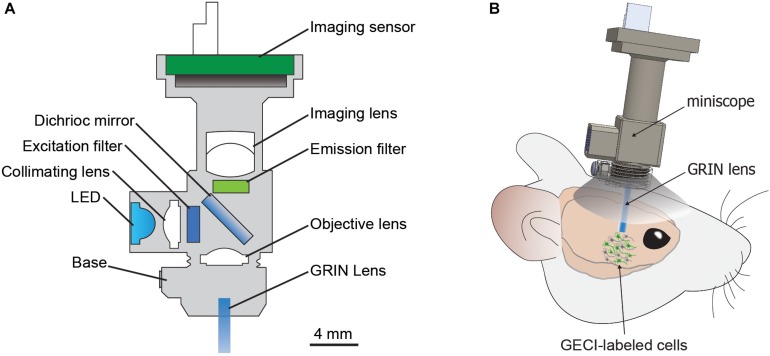

Due to technical challenges in performing longitudinal studies on individual neurons in large-scale populations from subcortical brain regions in freely moving animals, our current understanding of the neural circuit mechanisms that underlie NDDs and associated symptoms remains limited. In the present mini-review, we focus on the potential of the miniature fluorescence microscope (miniscope), a recently developed in vivo calcium imaging technology (Figure 1; Aharoni and Hoogland, 2019), to provide new insights into dysfunctional neural circuits that contribute to the pathogeneses of NDDs. We first discuss a brief history of the miniscope, and then describe specific capabilities of the miniscope with potential applications to study microcircuit dysfunction in models of NDDs.

FIGURE 1.

The miniscope. (A) Basic components of miniScope and GRIN lens system. (B) Schematic for a mounted miniScope with the GRIN lens aimed at GECI-labeled cells in a deep brain structure. GRIN, gradient index lens; GECI, genetically encoded calcium indicator.

A Brief History of the Miniscope

The observation of in vivo calcium transients using microscopy would not be possible without calcium indicators (Grienberger and Konnerth, 2012). Genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs; Miyawaki et al., 1997), and GCaMP-family GECIs in particular (Nakai et al., 2001; Tian et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2013), have proved to be incredibly important tools, and have played important roles in defining what can be achieved with calcium imaging. Ongoing advancements in calcium sensors continue to push beyond current limitations, and with activity sensors also moving beyond calcium, voltage, neurotransmitter, and ion sensors will help to shape a very different future for fluorescence microscopy (Table 1; Lin and Schnitzer, 2016; Deo and Lavis, 2018).

TABLE 1.

Selected genetically encoded indicators.

| Type | Sensor examples | Reference |

| Calcium | GCaMP6 | Chen et al., 2013 |

| GCaMP7 | Dana et al., 2019 | |

| jRGECO1 | Dana et al., 2016 | |

| XCaMPs | Inoue et al., 2019 | |

| Voltage | QuasAr2 | Hochbaum et al., 2014 |

| ArcLight | Kwon et al., 2017 | |

| Dopamine | GRABDA | Sun et al., 2018 |

| dLight1 | Patriarchi et al., 2018 | |

| Glutamate | SF-iGluSnFR | Marvin et al., 2018 |

| Acetylcholine | GACh | Jing et al., 2018 |

| Potassium | KIRIN1 | Shen et al., 2019 |

Coinciding with advancements in fluorescent activity reporters has been progress in imaging instrumentation. Since the development of two-photon microscopy (Denk et al., 1990), studies examining calcium activity have increased dramatically. Imaging cortical activity through cranial windows in head-fixed animals using a variety of behaviors has provided many new insights into the neuronal encoding of behavior (Yang et al., 2009; Komiyama et al., 2010), and the emergence of Gradient Index (GRIN) lenses, which relay images from one end to the other to provide an optical interface to the brain, has allowed for endoscopic imaging of deep brain regions (Barretto et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Examination of neuronal activity during behavior in freely moving animals was then made possible by the development of fiber-optic based microscopes (Helmchen et al., 2001, 2013; Flusberg et al., 2008; Sawinski et al., 2009) and miniature fluorescence microscopes with two-photon (Helmchen et al., 2001; Sawinski et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2017; Zong et al., 2017) or epifluorescent light sources (Ghosh et al., 2011).

The first miniscope was developed by Ghosh et al. (2011), which included a number of unique features. The miniscope was head-mounted with fluorescence excitation and detection onboard rather than away from the microscope, and also bypassed cost limitations of table-top setups by using commercially available and inexpensive technologies. The miniscope offers many unique advantages, including the ability to perform recordings that are cell-type specific, large-scale (hundreds of cells can be recorded), and longitudinal in nature [cells can be recorded for months (Zhang et al., 2019)]. These features provide a unique tool to study NDDs, as the miniscope can image cells in microcircuits during the development of NDD-like pathophysiology and behavior in animal models.

In Vivo Deep Brain Imaging in Freely Moving Animals

Many behavioral manifestations of NDDs have been modeled in animals (Gitler et al., 2017), and understanding the microcircuitry that encodes disease-related aberrant behaviors could provide essential insights into the neurobiology underlying NDDs. However, observing neuronal activity during behaviors in freely moving animals has been technically challenging. Two-photon imaging using table-top setup approaches requires head fixation, which limits the usability to certain behavioral assays. Moreover, differences in neural activity have been reported in head-fixed animals compared to freely moving animals, suggesting that head-restrained and natural conditions have different neural correlates (Ravassard et al., 2013; Aghajan et al., 2015). Various instruments have been developed to examine neuronal activity during behavior in freely moving animals (Helmchen et al., 2001, 2013; Flusberg et al., 2008; Sawinski et al., 2009; Liang et al., 2017; Zong et al., 2017), but the miniscope offers a unique option that is accessible, compact, and affordable (Figure 1 and Table 2; Aharoni and Hoogland, 2019).

TABLE 2.

Open-source miniscopes.

| Miniscope | Developer | Platform | Reference |

| UCLA miniscope | UCLA | http://miniscope.org/index.php/Main_Page | Cai et al., 2016 |

| FinchScope | Boston University | https://github.com/gardner-lab/FinchScope | Liberti et al., 2016 |

| miniScope | NIDA | https://github.com/giovannibarbera/miniscope_v1.0 | Barbera et al., 2016 |

| CHEndoscope | University of Toronto | https://github.com/jf-lab/chendoscope | Jacob et al., 2018 |

| cScope | Princeton | https://github.com/PrincetonUniversity/cScope | Scott et al., 2018 |

An additional technical challenge is accessing deep brain structures that are preferentially affected in many NDDs. Until recently, the ability of fluorescence microscopy to monitor neuron activity at subcellular resolution has been limited to superficial depths of ∼1 mm (Mittmann et al., 2011). This is due to light scattering that occurs in tissue (Ji, 2014), as well as tissue damage and inflammatory responses that occurs when removing overlaying tissue to provide optical access to a structure of interest. Imaging neurons in deeper brain structures is more practical with endoscopic techniques, which include insertion of lenses into the brain. The use of smaller-diameter GRIN lenses can reduce tissue damage (Bocarsly et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2019) and minimize the effect on behavior (Lee et al., 2016), which can be further improved with the use of robotic surgical instruments (Liang et al., 2019).

Longitudinal Tracking of Individual Cells to Study Ndds

Aging is a leading risk factor for many NDDs. While each NDD demonstrates unique spatiotemporal patterns of degeneration, the often-slow advancement of these diseases provides a similarly distinct challenge for researchers to study. A major cause of age-related degeneration is the accumulation of disease-specific misfolded proteins that lead to progressive loss of neuronal function (Hung et al., 2010; Chiti and Dobson, 2017). However, changes in patterned neural and circuit activity have also been observed in most NDDs and are believed to contribute to the onset and progression of disease states (Palop et al., 2006; Seeley et al., 2009).

Hyperexcitability in Early Stage of NDDs

Hyperexcitability has been observed in a number of NDDs. Cortical and peripheral hyperexcitability has been well-documented in clinical studies of ALS patients (Mills and Nithi, 1997; Vucic and Kiernan, 2006; Vucic et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2013; Menon et al., 2015), and is among the earliest pathologies identified in ALS patients (Bae et al., 2013) and during early stages of ALS-like pathology in rodent models (van Zundert et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2016; Marcuzzo et al., 2019). Therefore, it is presumed that neuronal hyperexcitability is an important factor that leads to neuronal loss in ALS. In AD, although hypoactivity is a key feature of late stages of the disease (Braak and Braak, 1991; Nestor et al., 2003), paradoxical hyperactivity has been observed in multiple brain regions of AD patients during pre-symptomatic stages (Sperling, 2007; Dickerson and Sperling, 2008; Miller et al., 2008; Pihlajamaki et al., 2009; Yassa et al., 2010). Furthermore, chronic aberrant increases in excitatory neuronal activity have been detected in the hippocampal and cortical regions in AD mouse models (Palop et al., 2007; Busche et al., 2008), and increasing neural activity has been demonstrated to directly promote the production and secretion of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide (Cirrito et al., 2005, 2008; Bero et al., 2011), whose excessive accumulation appears to play a causal role in AD (Stargardt et al., 2015). However, how hyperexcitable neurons encode behavior and contribute to disease progression remains unknown.

Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Hyperactivity

Targeting hyperactivity in mouse models of AD and ALS has been demonstrated to improve signatures of neural injury (Sanchez et al., 2012; Yuan and Grutzendler, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Haberman et al., 2017), and, importantly, clinical trials aiming to reduce hippocampal hyperactivity showed positive effects in patients with amnestic cognitive impairment (Bakker et al., 2012). The most widely prescribed drug for ALS, riluzole, reduces excitatory synaptic activity in the brain (Doble, 1996), and memantine, a therapeutic drug approved for use in late-stage AD, functions as a NMDA receptor antagonist to counteract hyperactive glutamatergic circuits (Zhu et al., 2013). But still, there remains a need to determine how these drugs affect neuronal activity to provide therapeutic relief to disease-related behavioral symptoms. Examining the activity of individual neurons across time could provide insights into how microcircuits encode pathophysiological behaviors as diseases advance. The miniscope is able to track individual neurons for several months during behaviors in freely moving animals (Liang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019), providing an opportunity to examine how changes in activity in individual neurons within a microcircuit across long periods of time affect behavior.

Imaging Specific Cellular Subtypes to Study Ndds

Each NDD has a signature pattern of degeneration progression. Particular circuits are vulnerable, and specific subtypes of cells within circuit-associated brain regions are targeted. In combination with transgenic rodent lines and/or cell-type specific and inducible promotors for vectors in gene therapy, specific neuron subtypes, and other cell-types in the brain can be imaged with the miniscope. This capability provides exciting opportunities for new insights into how neuronal subtypes encode pathology-related behaviors in models of NDDs.

Imaging Dopaminergic, Cholinergic, and Medium Spiny Neurons

The manifestation of PD symptoms is believed to be the cause of dopaminergic neuron loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) that leads to an imbalance in basal ganglia direct and indirect pathways (McGregor and Nelson, 2019). Studies with parkinsonian rodents have linked activity changes to discrete neuronal populations with potentially distinct contributions to and/or alleviation of parkinsonian motor symptoms (Mallet et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2018; Sagot et al., 2018). Using transgenic Cre-driver mouse lines and a commercial miniscope, Parker et al. (2018) reported that medium spiny neurons (MSNs) in the direct and indirect pathways displayed bidirectional changes in firing rate in parkinsonian mice. Firing rates in MSNs, along with behavioral abnormalities, were reversed by administration of L-DOPA or a dopamine receptor D2 receptor agonist (Parker et al., 2018). While this study demonstrated some of the capabilities of miniscope imaging, numerous questions still remain related to firing rate, pattern, and synchronization of neurons in the SNc and other brain regions that are believed to contribute to PD pathology.

Selective vulnerability of MSNs in the basal ganglia is a characteristic of HD (Ross and Tabrizi, 2011). MSNs are unique in that they not only receive dopaminergic input from the midbrain but also glutamatergic input from the cortex and other brain regions. Direct imaging of MSN activity in the basal ganglia would provide useful clues to determine intrinsic properties of MSNs that may lead to vulnerability in HD.

Neuromodulatory system dysfunction has been linked to a number of NDDs, but how specific neuromodulatory systems encode behavior in models of NDD has yet to be examined. Selective loss of cholinergic neurons have been observed in postmortem brains of AD patients (Whitehouse et al., 1981; Mesulam et al., 2004), and reductions in cholinergic markers are strongly correlated with cognitive decline in PD patients (Perry et al., 1985). Importantly, clinical studies support beneficial effects of cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in both PD and AD patients (Emre et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2013), suggesting a need to better understand how cholinergic neuron dysfunction contributes to symptoms in PD, AD, and other NDDs.

Imaging Specific Inhibitory Interneurons

γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) plays a central role in regulating neuronal excitability and maintaining balanced network activity, and inhibitory interneuron abnormalities also contribute to a number of NDDs. Inhibitory interneuron dysfunction has been suggested to contribute to network hypersynchrony (Palop and Mucke, 2016) that underlies frequent epileptic activity that occurs in AD patients (Vossel et al., 2016, 2017), as deficits in inhibitory interneurons result in impaired oscillatory rhythm and network hyperactivity in AD mouse models (Baglietto-Vargas et al., 2010; Villette et al., 2010; Verret et al., 2012; Hamm et al., 2017). In addition, reductions of subpopulations of inhibitory interneurons have been described in AD mouse models and postmortem brains of AD patients (Ramos et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2010; Albuquerque et al., 2015; Mahar et al., 2016). Dysfunctional interneurons have also been linked to upper motor neuron hyperexcitability in an ALS/FTD model (Zhang et al., 2016). Imbalance of excitation-to-inhibition (E/I) due to interneuron impairment has been suggested to be a potential common driver for AD and ALS, as well as other NDDs (Do-Ha et al., 2018; Ambrad Giovannetti and Fuhrmann, 2019). Studies on inhibitory interneurons using miniscope imaging in NDD models could shed light on this theory and provide information on inhibitory interneurons in NDD pathogenesis.

Imaging Specific Glial Cells

A variety of glial cells have complex reciprocal interactions with neurons to support their functions and are active participants in neural circuit refinement (Paolicelli et al., 2011; Schafer et al., 2012; Risher et al., 2014; Tani et al., 2014). For instance, subsets of astrocytes in the basal ganglia release glutamate to selectively activate homotypic synapses to regulate neural networks (Martin et al., 2015). Dysfunctional glial cells contribute to the disease progression in both HD and ALS through non-cell-autonomous toxicity (Yamanaka et al., 2008; Haidet-Phillips et al., 2011; Creus-Muncunill and Ehrlich, 2019). Neuroinflammation that results from chronic activation of immune responses are often mediated by microglia and occur in susceptible regions, and are believed to contribute to age-related degeneration (McGeer and McGeer, 2004; Cappellano et al., 2013). Microglial activation and reactive astrogliosis are observed in many NDDs, and reactive astrocytes lose many normal functions and gain new abnormal functions. Synapse elimination by microglial and astrocytes may contribute to the loss of presynaptic terminals and dendritic spines (Chung et al., 2015; Henstridge et al., 2019), one of the earliest features associated with cognitive impairment in many NDDs (Terry et al., 1991; Scheff et al., 2006). Glial cells may selectively remove excitatory or inhibitory synapses to compensate for disease-associated changes at specific brain regions (Hong et al., 2016; Aono et al., 2017; Paolicelli et al., 2017), or may act as a primary driver for the E/I imbalance by directly inducing excessive synaptic pruning (Serrano-Pozo et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2014). Studying glial activity though miniscope calcium imaging might provide useful information on the mechanism of how glial dysfunctions contribute to NDDs.

New Frontiers in Miniscope Imaging

The current generation of miniscopes offers many exciting possibilities for the study of NDDs. Innovation of the miniscope has been dramatically accelerated by open-source sharing of miniscope projects (Table 2; Aharoni and Hoogland, 2019), with functional improvements that hold the promise of new frontiers. The next generation of miniscopes and fluorescence sensors boast capabilities to distinguish two neuron subtypes simultaneously, manipulate cellular activity while imaging, image cellular events with non-calcium indicators, and record electrical properties (Deo and Lavis, 2018; Aharoni and Hoogland, 2019).

GECIs With Spectrally Separable Wavelengths

In the case of NDDs, it would be advantageous to simultaneously image a preferentially affected cell-type population, as those described above, while also imaging surrounding cell-types. This would provide information to understand how dysfunction of a vulnerable cellular population not only affects behavior, but also the other cells in the local microcircuit. Development of GECIs (Table 1) with spectrally separable wavelengths (Chen et al., 2013; Dana et al., 2016; Inoue et al., 2019) provide potential to examine the concomitance of two distinct neuronal populations correlated to specific behaviors, which can be accomplished a number of ways, including using a Cre-On/Cre-off approach (Saunders et al., 2012).

GECIs with distinct wavelengths also provide an opportunity to concurrently image and manipulate neural activity. Miniscope imaging offers correlational insight into neural activity that encodes behavior, but manipulating neural activity concurrently with imaging can offer insight into causal roles of cell populations within microcircuits (Stamatakis et al., 2018). This task can be achieved by using light-driven channels that have minimal overlapping spectra with a fluorescent activity sensor. One could also model dysregulated neuronal firing observed in NDDs with optogenetics while recording surrounding neuron activity during behavior.

Non-calcium Fluorescence Activity Sensors

Fluorescence imaging has focused primarily on measuring intracellular calcium transients. However, florescent sensors for dopamine transients (Patriarchi et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018), glutamate transients (Marvin et al., 2013, 2018), intracellular potassium ion concentration (Shen et al., 2019) and voltage signals (Lin and Schnitzer, 2016; Deo and Lavis, 2018), among others, have been developed for imaging (Table 1), with more to come. Many NDDs feature a variety of aberrant signaling, including dysfunction of dopamine and glutamate (Heath and Shaw, 2002; Hynd et al., 2004; Lewerenz and Maher, 2015; Schwab et al., 2015; Poewe et al., 2017), which provides an abundance of opportunities to study NDDs with these cutting-edge sensors. For example, dopamine sensors could be used to image dopamine transients in the SNc during progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons.

Extensive evidence suggests that many NDDs may be characterized by alterations in single-cell firing patterns and dyssynchronization between circuit nodes. Electrophysiological techniques currently offer unparalleled temporal resolution, but are unable to record spatiotemporal dynamics of action potential activity in ensembles with single-neuron resolution (Henze et al., 2000; Obien et al., 2014). Fluorescence imaging infers neural activity with high sensitivity but is traditionally unable to accurately resolve individual action potentials during high frequency firing due to slow decays. Engineering of voltage-responsive fluorophores is advancing rapidly with hopes of providing fluorescence responses that can greatly improve temporal resolution (Deo and Lavis, 2018; Quicke et al., 2019).

Conclusion

Capable of performing cell-type specific recordings on large-scale populations longitudinally, the miniscope offers opportunities to ask new and exciting questions in NDDs. Studies utilizing miniscope imaging are increasing rapidly across disciplines of neuroscience but are not commonly being used in NDD models. It is our hope that this mini-review, while by no means exhaustive, brings attention to the powerful capabilities of miniscope imaging, and offers a glimpse into potential questions that could be answered with miniscope experiments in studies of NDDs.

Author Contributions

CTW, CJW, MF, D-TL, and YL contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. CTW, D-TL, and YL wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by grants from NIH NIDA IRP, COBRE NIGMS (grant no. 5P20GM121310-03), and NINDS (grant nos. 1R61NS115161-01 and 1UG3NS115608-01).

References

- Aghajan Z. M., Acharya L., Moore J. J., Cushman J. D., Vuong C., Mehta M. R. (2015). Impaired spatial selectivity and intact phase precession in two-dimensional virtual reality. Nat. Neurosci. 18 121–128. 10.1038/nn.3884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni D., Hoogland T. M. (2019). Circuit investigations with open-source miniaturized microscopes: past, present and future. Front. Cell Neurosci. 13:141. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque M. S., Mahar I., Davoli M. A., Chabot J. G., Mechawar N., Quirion R., et al. (2015). Regional and sub-regional differences in hippocampal GABAergic neuronal vulnerability in the TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7:30. 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrad Giovannetti E., Fuhrmann M. (2019). Unsupervised excitation: GABAergic dysfunctions in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1707 216–226. 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aono H., Choudhury M. E., Higaki H., Miyanishi K., Kigami Y., Fujita K., et al. (2017). Microglia may compensate for dopaminergic neuron loss in experimental Parkinsonism through selective elimination of glutamatergic synapses from the subthalamic nucleus. Glia 65 1833–1847. 10.1002/glia.23199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae J. S., Simon N. G., Menon P., Vucic S., Kiernan M. C. (2013). The puzzling case of hyperexcitability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Clin. Neurol. 9 65–74. 10.3988/jcn.2013.9.2.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglietto-Vargas D., Moreno-Gonzalez I., Sanchez-Varo R., Jimenez S., Trujillo-Estrada L., Sanchez-Mejias E., et al. (2010). Calretinin interneurons are early targets of extracellular amyloid-beta pathology in PS1/AbetaPP Alzheimer mice hippocampus. J. Alzheimers Dis. 21 119–132. 10.3233/JAD-2010-100066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A., Krauss G. L., Albert M. S., Speck C. L., Jones L. R., Stark C. E., et al. (2012). Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron 74 467–474. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbera G., Liang B., Zhang L., Gerfen C. R., Culurciello E., Chen R., et al. (2016). Spatially Compact Neural Clusters in the Dorsal Striatum Encode Locomotion Relevant Information. Neuron 92 202–213. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barretto R. P., Messerschmidt B., Schnitzer M. J. (2009). In vivo fluorescence imaging with high-resolution microlenses. Nat. Methods 6 511–512. 10.1038/nmeth.1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bero A. W., Yan P., Roh J. H., Cirrito J. R., Stewart F. R., Raichle M. E., et al. (2011). Neuronal activity regulates the regional vulnerability to amyloid-beta deposition. Nat. Neurosci. 14 750–756. 10.1038/nn.2801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocarsly M. E., Jiang W. C., Wang C., Dudman J. T., Ji N., Aponte Y. (2015). Minimally invasive microendoscopy system for in vivo functional imaging of deep nuclei in the mouse brain. Biomed. Opt. Express 6 4546–4556. 10.1364/BOE.6.004546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82 239–259. 10.1007/bf00308809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche M. A., Eichhoff G., Adelsberger H., Abramowski D., Wiederhold K. H., Haass C., et al. (2008). Clusters of hyperactive neurons near amyloid plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 321 1686–1689. 10.1126/science.1162844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D. J., Aharoni D., Shuman T., Shobe J., Biane J., Song W., et al. (2016). A shared neural ensemble links distinct contextual memories encoded close in time. Nature 534 115–118. 10.1038/nature17955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canter R. G., Penney J., Tsai L. H. (2016). The road to restoring neural circuits for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 539 187–196. 10.1038/nature20412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellano G., Carecchio M., Fleetwood T., Magistrelli L., Cantello R., Dianzani U., et al. (2013). Immunity and inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2 89–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T. W., Wardill T. J., Sun Y., Pulver S. R., Renninger S. L., Baohan A., et al. (2013). Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499 295–300. 10.1038/nature12354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti F., Dobson C. M. (2017). Protein misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of progress over the last decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86 27–68. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung W. S., Welsh C. A., Barres B. A., Stevens B. (2015). Do glia drive synaptic and cognitive impairment in disease? Nat. Neurosci. 18 1539–1545. 10.1038/nn.4142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito J. R., Kang J. E., Lee J., Stewart F. R., Verges D. K., Silverio L. M., et al. (2008). Endocytosis is required for synaptic activity-dependent release of amyloid-beta in vivo. Neuron 58 42–51. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito J. R., Yamada K. A., Finn M. B., Sloviter R. S., Bales K. R., May P. C., et al. (2005). Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-beta levels in vivo. Neuron 48 913–922. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creus-Muncunill J., Ehrlich M. E. (2019). Cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous pathogenic mechanisms in huntington’s disease: insights from In Vitro and In Vivo Models. Neurotherapeutics [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dana H., Mohar B., Sun Y., Narayan S., Gordus A., Hasseman J. P., et al. (2016). Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity. eLife 5:e12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dana H., Sun Y., Mohar B., Hulse B. K., Kerlin A. M., Hasseman J. P., et al. (2019). High-performance calcium sensors for imaging activity in neuronal populations and microcompartments. Nat. Methods 16 649–657. 10.1038/s41592-019-0435-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk W., Strickler J. H., Webb W. W. (1990). Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science 248 73–76. 10.1126/science.2321027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deo C., Lavis L. D. (2018). Synthetic and genetically encoded fluorescent neural activity indicators. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 50 101–108. 10.1016/j.conb.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson B. C., Sperling R. A. (2008). Functional abnormalities of the medial temporal lobe memory system in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: insights from functional MRI studies. Neuropsychologia 46 1624–1635. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble A. (1996). The pharmacology and mechanism of action of riluzole. Neurology 47 S233–S241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do-Ha D., Buskila Y., Ooi L. (2018). Impairments in motor neurons, interneurons and astrocytes contribute to hyperexcitability in ALS: underlying mechanisms and paths to therapy. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 1410–1418. 10.1007/s12035-017-0392-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emre M., Aarsland D., Albanese A., Byrne E. J., Deuschl G., De Deyn P. P., et al. (2004). Rivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 351 2509–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flusberg B. A., Nimmerjahn A., Cocker E. D., Mukamel E. A., Barretto R. P., Ko T. H., et al. (2008). High-speed, miniaturized fluorescence microscopy in freely moving mice. Nat. Methods 5 935–938. 10.1038/nmeth.1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frere S., Slutsky I. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease: from firing instability to homeostasis network collapse. Neuron 97 32–58. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K. K., Burns L. D., Cocker E. D., Nimmerjahn A., Ziv Y., Gamal A. E., et al. (2011). Miniaturized integration of a fluorescence microscope. Nat. Methods 8 871–878. 10.1038/nmeth.1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler A. D., Dhillon P., Shorter J. (2017). Neurodegenerative disease: models, mechanisms, and a new hope. Dis. Model Mech. 10 499–502. 10.1242/dmm.030205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienberger C., Konnerth A. (2012). Imaging calcium in neurons. Neuron 73 862–885. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberman R. P., Branch A., Gallagher M. (2017). Targeting neural hyperactivity as a treatment to stem progression of late-onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 14 662–676. 10.1007/s13311-017-0541-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet-Phillips A. M., Hester M. E., Miranda C. J., Meyer K., Braun L., Frakes A., et al. (2011). Astrocytes from familial and sporadic ALS patients are toxic to motor neurons. Nat. Biotechnol 29 824–828. 10.1038/nbt.1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm V., Heraud C., Bott J. B., Herbeaux K., Strittmatter C., Mathis C., et al. (2017). Differential contribution of APP metabolites to early cognitive deficits in a TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 3:e1601068. 10.1126/sciadv.1601068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath P. R., Shaw P. J. (2002). Update on the glutamatergic neurotransmitter system and the role of excitotoxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 26 438–458. 10.1002/mus.10186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F., Denk W., Kerr J. N. (2013). Miniaturization of two-photon microscopy for imaging in freely moving animals. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2013 904–913. 10.1101/pdb.top078147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F., Fee M. S., Tank D. W., Denk W. (2001). A miniature head-mounted two-photon microscope. High-resolution brain imaging in freely moving animals. Neuron 31 903–912. 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00421-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henstridge C. M., Tzioras M., Paolicelli R. C. (2019). Glial contribution to excitatory and inhibitory synapse loss in neurodegeneration. Front. Cell Neurosci. 13:63. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze D. A., Borhegyi Z., Csicsvari J., Mamiya A., Harris K. D., Buzsaki G. (2000). Intracellular features predicted by extracellular recordings in the hippocampus in vivo. J. Neurophysiol. 84 390–400. 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochbaum D. R., Zhao Y., Farhi S. L., Klapoetke N., Werley C. A., Kapoor V., et al. (2014). All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins. Nat. Methods 11 825–833. 10.1038/nmeth.3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S., Beja-Glasser V. F., Nfonoyim B. M., Frouin A., Li S., Ramakrishnan S., et al. (2016). Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 352 712–716. 10.1126/science.aad8373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C. W., Chen Y. C., Hsieh W. L., Chiou S. H., Kao C. L. (2010). Ageing and neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 9(Suppl. 1), S36–S46. 10.1016/j.arr.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynd M. R., Scott H. L., Dodd P. R. (2004). Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 45 583–595. 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M., Takeuchi A., Manita S., Horigane S. I., Sakamoto M., Kawakami R., et al. (2019). Rational engineering of XCaMPs, a multicolor GECI suite for In Vivo imaging of complex brain circuit dynamics. Cell 177:e1324. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J., Jambrina E., Li J., Marston H., Menzies F., Phillips K., et al. (2019). Targeting the Synapse in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 13:735. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob A. D., Ramsaran A. I., Mocle A. J., Tran L. M., Yan C., Frankland P. W., et al. (2018). A compact head-mounted endoscope for In Vivo calcium imaging in freely behaving mice. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 84:e51. 10.1002/cpns.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji N. (2014). The practical and fundamental limits of optical imaging in mammalian brains. Neuron 83 1242–1245. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing M., Zhang P., Wang G., Feng J., Mesik L., Zeng J., et al. (2018). A genetically encoded fluorescent acetylcholine indicator for in vitro and in vivo studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 36 726–737. 10.1038/nbt.4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama T., Sato T. R., O’connor D. H., Zhang Y. X., Huber D., Hooks B. M., et al. (2010). Learning-related fine-scale specificity imaged in motor cortex circuits of behaving mice. Nature 464 1182–1186. 10.1038/nature08897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon T., Sakamoto M., Peterka D. S., Yuste R. (2017). Attenuation of synaptic potentials in dendritic spines. Cell Rep. 20 1100–1110. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxton A. W., Tang-Wai D. F., Mcandrews M. P., Zumsteg D., Wennberg R., Keren R., et al. (2010). A phase I trial of deep brain stimulation of memory circuits in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 68 521–534. 10.1002/ana.22089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. A., Holly K. S., Voziyanov V., Villalba S. L., Tong R., Grigsby H. E., et al. (2016). Gradient index microlens implanted in prefrontal cortex of mouse does not affect behavioral test performance over Time. PLoS One 11:e0146533. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewerenz J., Maher P. (2015). Chronic glutamate toxicity in neurodegenerative diseases-what is the evidence? Front. Neurosci. 9:469. 10.3389/fnins.2015.00469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B., Zhang L., Moffitt C., Li Y., Lin D. T. (2019). An open-source automated surgical instrument for microendoscope implantation. J. Neurosci. Methods 311 83–88. 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2018.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B., Zhang L. F., Barbera G., Fang W., Zhang J., Chen X., et al. (2018). Distinct and dynamic On and Off neural ensembles in the prefrontal cortex code social exploration. Neuron 100 700.e9–714.e9. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W., Hall G., Messerschmidt B., Li M. J., Li X. (2017). Nonlinear optical endomicroscopy for label-free functional histology in vivo. Light Sci. Appl. 6:e17082. 10.1038/lsa.2017.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberti W. A., III, Markowitz J. E., Perkins L. N., Liberti D. C., Leman D. P., Guitchounts G., et al. (2016). Unstable neurons underlie a stable learned behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 19 1665–1671. 10.1038/nn.4405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. Z., Schnitzer M. J. (2016). Genetically encoded indicators of neuronal activity. Nat. Neurosci. 19 1142–1153. 10.1038/nn.4359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahar I., Albuquerque M. S., Mondragon-Rodriguez S., Cavanagh C., Davoli M. A., Chabot J. G., et al. (2016). Phenotypic alterations in hippocampal NPY- and PV-expressing interneurons in a presymptomatic transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8:327. 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet N., Schmidt R., Leventhal D., Chen F., Amer N., Boraud T., et al. (2016). Arkypallidal cells send a stop signal to striatum. Neuron 89 308–316. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcuzzo S., Terragni B., Bonanno S., Isaia D., Cavalcante P., Cappelletti C., et al. (2019). Hyperexcitability in cultured cortical neuron networks from the G93A-SOD1 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis model mouse and its molecular correlates. Neuroscience 416 88–99. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R., Bajo-Graneras R., Moratalla R., Perea G., Araque A. (2015). Circuit-specific signaling in astrocyte-neuron networks in basal ganglia pathways. Science 349 730–734. 10.1126/science.aaa7945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin J. S., Borghuis B. G., Tian L., Cichon J., Harnett M. T., Akerboom J., et al. (2013). An optimized fluorescent probe for visualizing glutamate neurotransmission. Nat. Methods 10 162–170. 10.1038/nmeth.2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin J. S., Scholl B., Wilson D. E., Podgorski K., Kazemipour A., Muller J. A., et al. (2018). Stability, affinity, and chromatic variants of the glutamate sensor iGluSnFR. Nat. Methods 15 936–939. 10.1038/s41592-018-0171-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer P. L., McGeer E. G. (2004). Inflammation and the degenerative diseases of aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1035 104–116. 10.1196/annals.1332.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor M. M., Nelson A. B. (2019). Circuit Mechanisms of Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron 101 1042–1056. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon P., Kiernan M. C., Vucic S. (2015). Cortical hyperexcitability precedes lower motor neuron dysfunction in ALS. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126 803–809. 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M., Shaw P., Mash D., Weintraub S. (2004). Cholinergic nucleus basalis tauopathy emerges early in the aging-MCI-AD continuum. Ann. Neurol. 55 815–828. 10.1002/ana.20100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. L., Fenstermacher E., Bates J., Blacker D., Sperling R. A., Dickerson B. C. (2008). Hippocampal activation in adults with mild cognitive impairment predicts subsequent cognitive decline. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 79 630–635. 10.1136/jnnp.2007.124149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills K. R., Nithi K. A. (1997). Corticomotor threshold is reduced in early sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 20 1137–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann W., Wallace D. J., Czubayko U., Herb J. T., Schaefer A. T., Looger L. L., et al. (2011). Two-photon calcium imaging of evoked activity from L5 somatosensory neurons in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 14 1089–1093. 10.1038/nn.2879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki A., Llopis J., Heim R., Mccaffery J. M., Adams J. A., Ikura M., et al. (1997). Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 388 882–887. 10.1038/42264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai J., Ohkura M., Imoto K. (2001). A high signal-to-noise Ca(2+) probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 19 137–141. 10.1038/84397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor P. J., Fryer T. D., Smielewski P., Hodges J. R. (2003). Limbic hypometabolism in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann. Neurol. 54 343–351. 10.1002/ana.10669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obien M. E., Deligkaris K., Bullmann T., Bakkum D. J., Frey U. (2014). Revealing neuronal function through microelectrode array recordings. Front. Neurosci. 8:423. 10.3389/fnins.2014.00423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop J. J., Chin J., Mucke L. (2006). A network dysfunction perspective on neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443 768–773. 10.1038/nature05289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop J. J., Chin J., Roberson E. D., Wang J., Thwin M. T., Bien-Ly N., et al. (2007). Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 55 697–711. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop J. J., Mucke L. (2016). Network abnormalities and interneuron dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17 777–792. 10.1038/nrn.2016.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolicelli R. C., Bolasco G., Pagani F., Maggi L., Scianni M., Panzanelli P., et al. (2011). Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science 333 1456–1458. 10.1126/science.1202529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolicelli R. C., Jawaid A., Henstridge C. M., Valeri A., Merlini M., Robinson J. L., et al. (2017). TDP-43 depletion in microglia promotes amyloid clearance but also induces synapse loss. Neuron 95:e296. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. G., Marshall J. D., Ahanonu B., Wu Y. W., Kim T. H., Grewe B. F., et al. (2018). Diametric neural ensemble dynamics in parkinsonian and dyskinetic states. Nature 557 177–182. 10.1038/s41586-018-0090-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriarchi T., Cho J. R., Merten K., Howe M. W., Marley A., Xiong W. H., et al. (2018). Ultrafast neuronal imaging of dopamine dynamics with designed genetically encoded sensors. Science 360:eaat4422. 10.1126/science.aat4422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pchitskaya E., Popugaeva E., Bezprozvanny I. (2018). Calcium signaling and molecular mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Calcium 70 87–94. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry E. K., Curtis M., Dick D. J., Candy J. M., Atack J. R., Bloxham C. A., et al. (1985). Cholinergic correlates of cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: comparisons with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 48 413–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajamaki M., Jauhiainen A. M., Soininen H. (2009). Structural and functional MRI in mild cognitive impairment. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 6 179–185. 10.2174/156720509787602898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poewe W., Seppi K., Tanner C. M., Halliday G. M., Brundin P., Volkmann J., et al. (2017). Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 3:17013. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quicke P., Song C., Mckimm E. J., Milosevic M. M., Howe C. L., Neil M., et al. (2019). Single-neuron level one-photon voltage imaging with sparsely targeted genetically encoded voltage indicators. Front. Cell Neurosci. 13:39. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos B., Baglietto-Vargas D., Del Rio J. C., Moreno-Gonzalez I., Santa-Maria C., Jimenez S., et al. (2006). Early neuropathology of somatostatin/NPY GABAergic cells in the hippocampus of a PS1xAPP transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 27 1658–1672. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravassard P., Kees A., Willers B., Ho D., Aharoni D. A., Cushman J., et al. (2013). Multisensory control of hippocampal spatiotemporal selectivity. Science 340 1342–1346. 10.1126/science.1232655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risher W. C., Patel S., Kim I. H., Uezu A., Bhagat S., Wilton D. K., et al. (2014). Astrocytes refine cortical connectivity at dendritic spines. eLife 3:e04047. 10.7554/eLife.04047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez G. A., Tai L. M., Ladu M. J., Rebeck G. W. (2014). Human APOE4 increases microglia reactivity at Abeta plaques in a mouse model of Abeta deposition. J Neuroinflammation 11:111. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. A., Tabrizi S. J. (2011). Huntington’s disease: from molecular pathogenesis to clinical treatment. Lancet Neurol. 10 83–98. 10.1016/s1474-4422(10)70245-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M. B., Bair-Marshall C., Nelson A. B. (2018). Aberrant striatal activity in parkinsonism and levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Cell Rep. 23:e3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagot B., Li L., Zhou F. M. (2018). Hyperactive response of direct pathway striatal projection neurons to L-dopa and D1 agonism in freely moving parkinsonian mice. Front. Neural Circuits 12:57. 10.3389/fncir.2018.00057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez P. E., Zhu L., Verret L., Vossel K. A., Orr A. G., Cirrito J. R., et al. (2012). Levetiracetam suppresses neuronal network dysfunction and reverses synaptic and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 E2895–E2903. 10.1073/pnas.1121081109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders A., Johnson C. A., Sabatini B. L. (2012). Novel recombinant adeno-associated viruses for Cre activated and inactivated transgene expression in neurons. Front. Neural Circuits 6:47. 10.3389/fncir.2012.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawinski J., Wallace D. J., Greenberg D. S., Grossmann S., Denk W., Kerr J. N. (2009). Visually evoked activity in cortical cells imaged in freely moving animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 19557–19562. 10.1073/pnas.0903680106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer D. P., Lehrman E. K., Kautzman A. G., Koyama R., Mardinly A. R., Yamasaki R., et al. (2012). Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron 74 691–705. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheff S. W., Price D. A., Schmitt F. A., Mufson E. J. (2006). Hippocampal synaptic loss in early Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 27 1372–1384. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab L. C., Garas S. N., Drouin-Ouellet J., Mason S. L., Stott S. R., Barker R. A. (2015). Dopamine and Huntington’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 15 445–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott B. B., Thiberge S. Y., Guo C., Tervo D. G. R., Brody C. D., Karpova A. Y., et al. (2018). Imaging cortical dynamics in GCaMP transgenic rats with a head-mounted widefield macroscope. Neuron 100:e1045. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley W. W., Crawford R. K., Zhou J., Miller B. L., Greicius M. D. (2009). Neurodegenerative diseases target large-scale human brain networks. Neuron 62 42–52. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Pozo A., Muzikansky A., Gomez-Isla T., Growdon J. H., Betensky R. A., Frosch M. P., et al. (2013). Differential relationships of reactive astrocytes and microglia to fibrillar amyloid deposits in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 72 462–471. 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182933788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Wu S. Y., Rancic V., Aggarwal A., Qian Y., Miyashita S. I., et al. (2019). Genetically encoded fluorescent indicators for imaging intracellular potassium ion concentration. Commun. Biol. 2:18. 10.1038/s42003-018-0269-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling R. (2007). Functional MRI studies of associative encoding in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1097 146–155. 10.1196/annals.1379.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. M., Schachter M. J., Gulati S., Zitelli K. T., Malanowski S., Tajik A., et al. (2018). Simultaneous optogenetics and cellular resolution calcium imaging during active behavior using a miniaturized microscope. Front. Neurosci. 12:496. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stargardt A., Swaab D. F., Bossers K. (2015). Storm before the quiet: neuronal hyperactivity and Abeta in the presymptomatic stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 36 1–11. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F., Zeng J., Jing M., Zhou J., Feng J., Owen S. F., et al. (2018). A genetically encoded fluorescent sensor enables rapid and specific detection of dopamine in flies. Fish, and Mice. Cell 174 481.e19–496.e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Brasnjevic I., Rutten B. P., Van Der Kolk N., Perl D. P., Bouras C., et al. (2010). Hippocampal interneuron loss in an APP/PS1 double mutant mouse and in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Struct. Funct. 214 145–160. 10.1007/s00429-010-0242-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani H., Dulla C. G., Farzampour Z., Taylor-Weiner A., Huguenard J. R., Reimer R. J. (2014). A local glutamate-glutamine cycle sustains synaptic excitatory transmitter release. Neuron 81 888–900. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. D., Masliah E., Salmon D. P., Butters N., Deteresa R., Hill R., et al. (1991). Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann. Neurol. 30 572–580. 10.1002/ana.410300410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Hires S. A., Mao T., Huber D., Chiappe M. E., Chalasani S. H., et al. (2009). Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods 6 875–881. 10.1038/nmeth.1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zundert B., Peuscher M. H., Hynynen M., Chen A., Neve R. L., Brown R. H., et al. (2008). Neonatal neuronal circuitry shows hyperexcitable disturbance in a mouse model of the adult-onset neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 28 10864–10874. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1340-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verret L., Mann E. O., Hang G. B., Barth A. M., Cobos I., Ho K., et al. (2012). Inhibitory interneuron deficit links altered network activity and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer model. Cell 149 708–721. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villette V., Poindessous-Jazat F., Simon A., Lena C., Roullot E., Bellessort B., et al. (2010). Decreased rhythmic GABAergic septal activity and memory-associated theta oscillations after hippocampal amyloid-beta pathology in the rat. J. Neurosci. 30 10991–11003. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6284-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel K. A., Ranasinghe K. G., Beagle A. J., Mizuiri D., Honma S. M., Dowling A. F., et al. (2016). Incidence and impact of subclinical epileptiform activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 80 858–870. 10.1002/ana.24794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vossel K. A., Tartaglia M. C., Nygaard H. B., Zeman A. Z., Miller B. L. (2017). Epileptic activity in Alzheimer’s disease: causes and clinical relevance. Lancet Neurol. 16 311–322. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30044-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucic S., Kiernan M. C. (2006). Novel threshold tracking techniques suggest that cortical hyperexcitability is an early feature of motor neuron disease. Brain 129 2436–2446. 10.1093/brain/awl172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vucic S., Nicholson G. A., Kiernan M. C. (2008). Cortical hyperexcitability may precede the onset of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 131 1540–1550. 10.1093/brain/awn071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse P. J., Price D. L., Clark A. W., Coyle J. T., Delong M. R. (1981). Alzheimer disease: evidence for selective loss of cholinergic neurons in the nucleus basalis. Ann. Neurol. 10 122–126. 10.1002/ana.410100203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. L., Fifita J. A., Vucic S., Durnall J. C., Kiernan M. C., Blair I. P., et al. (2013). Pathophysiological insights into ALS with C9ORF72 expansions. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84 931–935. 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka K., Chun S. J., Boillee S., Fujimori-Tonou N., Yamashita H., Gutmann D. H., et al. (2008). Astrocytes as determinants of disease progression in inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Neurosci. 11 251–253. 10.1038/nn2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Pan F., Gan W. B. (2009). Stably maintained dendritic spines are associated with lifelong memories. Nature 462 920–924. 10.1038/nature08577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhang L., Wang Z., Liang B., Barbera G., Moffitt C., et al. (2019). A two-step grin lens coating for In Vivo brain imaging. Neurosci. Bull. 35 419–424. 10.1007/s12264-019-00356-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa M. A., Stark S. M., Bakker A., Albert M. S., Gallagher M., Stark C. E. (2010). High-resolution structural and functional MRI of hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage 51 1242–1252. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P., Grutzendler J. (2016). Attenuation of beta-amyloid deposition and neurotoxicity by chemogenetic modulation of neural activity. J. Neurosci. 36 632–641. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2531-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Liang B., Barbera G., Hawes S., Zhang Y., Stump K., et al. (2019). Miniscope GRIN lens system for calcium imaging of neuronal activity from deep brain structures in behaving animals. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 86:e56. 10.1002/cpns.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Zhang L., Liang B., Schroeder D., Zhang Z. W., Cox G. A., et al. (2016). Hyperactive somatostatin interneurons contribute to excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 19 557–559. 10.1038/nn.4257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C. W., Livote E. E., Scarmeas N., Albert M., Brandt J., Blacker D., et al. (2013). Long-term associations between cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine use and health outcomes among patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 9 733–740. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong W., Wu R., Li M., Hu Y., Li Y., Li J., et al. (2017). Fast high-resolution miniature two-photon microscopy for brain imaging in freely behaving mice. Nat. Methods 14 713–719. 10.1038/nmeth.4305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]