Abstract

This paper compares facets of behavior analysis and intersectional feminist theory. We begin by describing the history of issues related to gender and sexuality in behavior analysis. Then, we explain how the goals of feminism and applied behavior analysis are aligned, with a focus on intersectional feminism. Intersectional feminism examines the influence of interacting variables (e.g., race, gender, and sexuality) that affect one’s experiences and behaviors, rather than focusing on a single factor, such as gender. Pragmatic behaviorism and intersectionality have many parallels, and by exploring them, researchers can generate more comprehensive explanations of behavior. With prevalent gender, race, and sexual orientation biases in contemporary society, it may be important for behavior analysts to be able to recognize these contingencies that have been previously overlooked. Describing the conceptual commonalities between these disciplines may be a stride towards inclusivity and advancement of the goals of each discipline.

Keywords: Behavior analysis, Behaviorism, Gender, Intersectional feminism, Sexuality

In light of the recent Me Too and Time’s Up movements, issues of sexual abuse, power, and equality have been brought to the forefront of societal discourse. The exploration of these issues within academic disciplines such as behavior analysis may contribute to the expanded impact of these movements and further propel social change. Behavior analysis, in particular, has seen a recent call for broad social action to promote a more equitable, more nurturing society to promote human well-being (e.g., Biglan, 2015; Geller, 2014). Individuals are frequently treated inequitably based on gender and sexuality, and behavior analysts may be well-suited to advance social change in these domains. The efforts of behavior analysts can be further supported, if they are aligned with other approaches to promoting social justice, such as intersectional feminism (cf. Crenshaw, 1989). From the perspective of intersectional feminism, an array of variables (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation) interact to create the experience and perspective of individuals, modifying the salience of particular environmental events and influencing behavior. If behavior analysts integrate other perspectives, such as intersectional feminism, into their conceptual framework and practice, they may be able to generate more complete explanations of behavior, and recognize the gender, race, and sexual orientation biases that have been overlooked in the past. By interfacing with proponents of intersectionality, behavior analysis can advance as a field and enable positive social change. However, the history of women and sexuality in behavior analysis must first be acknowledged in order to then advocate for the incorporation of intersectionalist theory. The present paper describes the history of gender representation in behavior analysis and the conceptual interaction between behavior analysis and feminism, and provides suggestions for implementing intersectionality in behavior-analytic practice.

Historical Context

Although considerable strides towards equality have been made recently, women have been historically underrepresented in psychology and continue to battle for participation in this field. When the American Psychological Association was founded in 1892, women had few opportunities to advance academically, and found limited access to graduate education (Simon, Morris, & Smith, 2007). It was not until 1942 that the National Council of Women Psychologists was founded to address these problems. However, this council was not a panacea for the problem of representation. The Association for Women in Psychology, the Committee on Women in Psychology, the American Psychological Association’s Women’s Program Office and Society for Women in Psychology (Division 35) were founded in the 1970s, and these groups furthered the cause of representing women in psychology.

Throughout this time, there have been some advances in terms of women’s progress in psychology, including a significant increase in the doctoral degrees awarded to women in clinical and counseling psychology. The American Psychological Association task force (1995) found that 64% of clinical doctoral students were women. However, in other areas such as experimental, physiological, and comparative psychology, men continued to be overrepresented in these fields (Osterang & McNamara, 1991). More recently, however, women have had an increased presence in these areas. In a 2006 report, the Women’s Program Office of the American Psychological Association (2006) presented data indicating that from 1996 to 2002, women earned approximately two-thirds of all doctoral degrees in psychology across all subfields, and had attained more leadership roles than in earlier time periods.

As a disciplinary cousin of psychology, behavior analysis is not exempt from underrepresentation of women. Indeed, the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior (JEAB) was founded by a group composed solely of men (Laties, 2008). In addition, for the first 50 years of its existence, JEAB’s editors were all male. However, after the journal’s initial years, there was a steady, small proportion of women serving on this journal’s editorial board (Laties, 2008). This did not mean, however, that women were publishing in the journal. McSweeney, Donahoe, and Swindell (2000) found that participation among women systematically decreased as the selectivity of four top journals in behavior analysis—the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, Behavior Therapy, Behavior Modification, and Behavior Research and Therapy—increased.

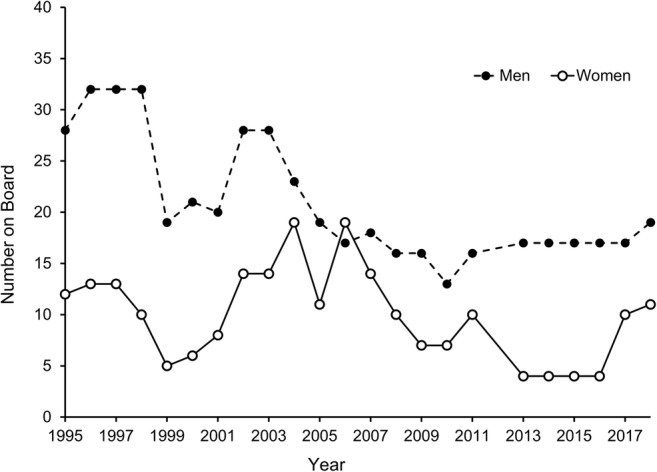

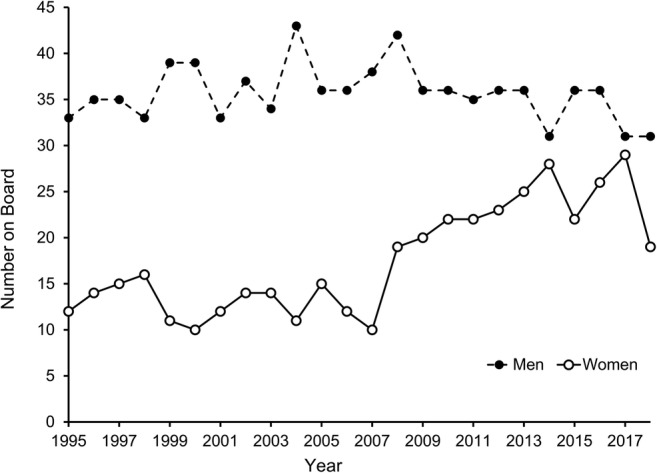

In prominent behavior-analytic journals, like The Behavior Analyst (now Perspectives on Behavior Science), the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, and the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, women are also picking up ground in editorial boards. Between 1995 and 2003, women made up only 21% to 35% of The Behavior Analyst editorial board. In 2004, women accounted for 45% of the editorial board, and then 52% in 2006. Since then, women have constituted between 19% and 44% of the editorial board between 2007 and 2018 (see Fig. 1). In the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, women made up only between 20% and 31% from 1994 to 2008, but the proportion increased to between 36% and 48% from 2009 to 2018 (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The number of men and women on The Behavior Analyst editorial board by year

Fig. 2.

The number of men and women on the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis editorial board by year

While publication and editorial activities may provide an index of the representation within a discipline, there is a stringent selectivity to this process. Participation in conference presentations may be more broadly available to members of a professional community. Simon et al. (2007) evaluated women’s representation at conferences in behavior analysis. At the annual meetings of the Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) from 1975 to 2005, women were consistently underrepresented in participation relative to men. Specifically, in 2005, women were still below parity in 7 of the 11 presentations (either poster, symposia, paper, or invited presentations), as well as participation roles (number of women chairs and discussants on the symposia, paper, and invited sessions), and authorship levels (sole author, first author of two authors, or other than first author). Simon et al. (2007) also found that women’s percentage of presentation of invited papers was at least three times lower than males, and male authors outnumbered women authors by almost 3 to 1 in the first 10 years of the ABAI’s existence.

While representation of gender is important, there are other minority classifications (e.g., ethnicity, sexual orientation) that may also be of interest when considering the degree to which a discipline is representative and inclusive. Although there are some data (as described above) related to gender representation, there is virtually no research regarding diversity with respect to ethnicity and sexual orientation within the profession of behavior analysis. Within psychology as a general field, the research examining minority group representation has not had favorable findings. Russo, Olmedo, Stapp, and Fulcher (1981) found that 3.1% of all APA members and 8% of all doctorate recipients were racial minorities. Twenty-two years later, the percentage of minorities holding doctoral degrees had only increased to 22.1% in 2003 (Maton, Kohout, Wicherski, Leary, & Vinokurov, 2006). Since then, there has been minimal literature on the representation of minorities in psychology, with no papers exploring these variables within the context of behavior analysis. Such work represents a potentially important mechanism to better understand our profession and the people who influence it.

Although the previous data are potentially discouraging, the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) shows progress in representing women—four of the six current executive staff are female. According to their website, the BACB’s board of directors also shows decent representation of women, with six female directors out of the 11 positions (including the President and Vice President) at the time of writing this manuscript. Nosik, Luke, and Carr (2018), three of the leaders of the BACB, summarized a variety of metrics related to the representation of women in behavior analysis. They reported that 53% of the presidents of the Association for Behavioral Analysis International, the Association for Professional Behavior Analysts, and the BACB were women from the past 5 years. Similarly, Li, Curiel, Pritchard, and Poling (2018) found that from 2014 to 2017, there were more women than men as first authors in The Analysis of Verbal Behavior and the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Together, these data indicate substantial progress in the representation of women in behavior analysis. Such progress may be viewed favorably, particularly in light of where the field has been in terms of issues of sexuality and gender equality. The discussion of interventions related to gender expression and sexuality provide additional historical context for issues associated with feminist theory; these interventions will be discussed before describing the integration of philosophical systems relevant to feminism and behaviorism.

Early in its history, applied behavior analysis included treatments for “deviant” sexual behavior, including homosexuality and transgenderism. For instance, McGuire and Vallance (1964) conducted a study using electric shock therapy to eliminate sexual fetishes, among other behaviors, such as homosexuality and alcoholism. Subsequently, several other studies were done to modify the sexual behavior of gay and trans* (i.e., individuals whose gender identity did not correspond with their sex designated at birth) men. In 1973, Barlow and Agras conducted a study on three gay cisgender (i.e., individuals whose gender identity corresponded with their sex designated at birth) men using a fading technique, in an attempt to increase arousal when looking at images of nude females rather than nude males. In the following year, Callahan and Leitenberg (1973) tested two aversion treatments, one which delivered an electric shock following arousal to homosexual erotic material, and the other which made the participant imagine an aversive event with homosexual behavior, like vomiting, while engaging in a sexual act. Furthermore, Rekers and Lovaas (1974) attempted to eliminate a 5-year-old boy’s desire to be a girl by providing reinforcement contingent on “masculine” behavior and ignoring (i.e., extinction) contingent on “feminine” behavior.

Although there are not clearly available records of the clinical application of the techniques described in the previous research, it is possible that they were applied in practice. Since the 1970s, multiple professional organizations, including the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Counseling Association, have come out to oppose conversion therapies and insist on conveying to the client accurate information on sexuality and offer alternatives (Haldeman, 1999). Within the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2016), the use of reinforcement-based procedures is required before the use of aversive interventions. Thus, these early studies no longer meet the ethical requirements for our field and are no longer consistent with societal and scientific views of sexual behavior. Within the context of research, greater protections have been afforded to all human subjects, not just members of LGBTQ+ populations. For instance, in the BACB’s ethics code, Section 9 deals with the responsible conduct of research, including the elements of informed consent (9.03), review by appropriate ethics boards (9.02a), and maintaining the dignity and welfare of research participants (9.02c). Thus, contemporary research is more consistent with the ethical application of behavior-analytic techniques.

Recently, researchers have demonstrated the efficacy of ethical behavior-analytic interventions for sexual behaviors. Whereas gender nonconformity was previously labeled as inappropriate, now inappropriate behaviors are identified as a function of the harm that is possible to the individual engaging in them, or to other people in their environment. For example, McLay, Carnett, Tyler-Merrick, and van der Meer (2015) reviewed the literature on children with intellectual disabilities displaying inappropriate sexual behavior (public masturbation, inappropriate touching of others, etc.) and found that out of 12 relevant studies, the majority of those that used behavioral strategies used a multicomponent intervention to decrease inappropriate sexual behavior. Two studies used aversive procedures; however, it should be noted that these were almost the two oldest studies reviewed, conducted in 1978 and 1981. Three of the studies used an antidepressant medication, and one study used a cognitive behavioral intervention.

Other studies have been conducted by behavior analysts to identify inappropriate sexual arousal to children in adults with developmental disabilities. For example, Reyes et al. (2006) and Reyes, Vollmer, and Hall (2017) used a penile plethysmograph to measure change in penile circumference to appropriate/non-deviant stimuli (adult men and women) and inappropriate/deviant stimuli (children). They used stimulus preference assessment procedures and penile plethysmography (to measure tumescence) to assess sex offenders with intellectual disabilities for age and gender preferences. These researchers noted that these findings have clinical application for teaching specific skills to this population so that they can avoid specific high-risk stimuli and situations. This current approach is more humane than the initial approach the field took to issues related to sexuality and helps to support marginalized populations. Thus, it may be considered more consistent with a feminist perspective.

Behavior Analysis and Feminism

Historically, behavior analysts have not considered issues associated with feminism. For instance, in his novel Walden II, Skinner (1948) focused on the thoughts and experiences of the male characters, minimizing women’s roles. The main character, Frazier, explained that after a woman has several children, she is then finally equal to men, and should be as able-bodied as she was before having kids. Wolpert (2005) noted that no social contingencies are discussed related to the duration of the pregnancy, or during the labor itself. In Notebooks, Skinner commented that an author writing a book is much the same as a mother having a baby, in that neither do much other than “participate” (1980, p. 333). The treatment of childbearing indicates little appreciation for the complexities of a woman carrying a child, or the labor itself, and disregards any possible hardships. Also in Notebooks, when Skinner wrote about social contingencies, he only explained the social contingencies in place for boys, suggesting that boys “are less likely to be nurtured for small wounds and more likely to be shamed for crying” (p. 346), failing to comment on the social contingencies girls experience. Of course, these works arose as the product of a different historical era, and contemporary behavior analysts can operate in a more “woke” (i.e., inclusive and aware) environment. Despite its history, a behavioral perspective can still help support the goals of feminism, which is to carry out social movements “necessary to achieve equality between women and men, with the understanding that gender always intersects with other hierarchies” (Freedman, 2002, p. 7). Maria Ruiz, a feminist behavior analyst who spent much of her career teaching at Rollins College (cf. Soreth, Dickson, & Terry, 2017), published several articles discussing how this could be possible.

Ruiz (1995) discussed what radical behaviorism can offer feminism and explained why a feminist perspective would not agree with radical behaviorism. First, Ruiz (1995) clarified that feminists may not agree with the perspective of radical behaviorists because of common misconceptions of what radical behaviorism really is. This includes thinking the organism is passive to external influences, that behaviorism is a simple stimulus-response mechanistic psychology, and that radical behaviorists ignore individual experiences like feelings. These misconceptions of behaviorism would be antithetical to a feminist perspective.

As readers of this journal likely know, radical behaviorism, unlike methodological behaviorism, is contextual in its approach (e.g., Morris, 1988, 1993) and thus would appeal to a feminist standpoint. Contextualism applies to the principles of behavior by recognizing that these principles can change, regardless of how long they have been useful (Morris, 1993). For instance, the interventions for sexual behavior involving electric shock described above were considered appropriate in the local context in which they occurred. Now, however, they are no longer appropriate. Morris (1993) noted that behavior emerges as a function of both its historic context and current context. This would align with feminist thought, as historical and contemporary experiences can impact the oppression experienced by an individual. Thus, both fields understand the importance taking into account the environment and its role in the development of the individual.

Despite this point of congruence, Ruiz (1998) indicated that there is a disagreement between behaviorists and feminists on agency, and how each group defines it. In a possible paradox, feminists believe that the agent is the source of resistance, yet also believe that external social controls are limiting the individual. For a behaviorist, this theory would need to be reconstructed, as one cannot attribute resistance to something “within” the individual. Ruiz (1998) explained that a behaviorist would define agency as actions, which include “knowing that” you are doing agentic acts and denying agency as a characteristic of the individual (p. 189). So, instead of agency being an internal trait, it can be redefined as the behaviors of an individual. With this reconstructed framework, it is now easier to incorporate feminism into behaviorism.

Ruiz (2007) also emphasized the shared agreement on pragmatism for both behaviorists and feminists. Generally, pragmatism is a method of achieving meaning by the usefulness of the idea based in action; see Lattal and Laipple (2003) for a discussion of the interaction between pragmatism and behavior analysis. Ruiz explained how pragmatism can relate to feminism. Instead of searching for some ultimate truth about the world, Ruiz (2007) suggested that the style of pragmatism advanced by John Dewey is more appropriate, as it allows many possible reasons for individuals to vary. Dewey’s theory emphasized making the future better than the present by seeking the best possible course of action for a group. Recognizing that one solution may work for some people but not others, Ruiz (2007) explained that Dewey’s theory encourages open, free discussion that allows dialogue across cultures to advance society. This way of thinking supports feminist thought. Heldke (1987) explained that Dewey and Evelyn Fox Keller, a famous feminist, shared a similar epistemology. Both emphasized the importance of the activity of knowing, like the processes of coming to solutions, rather than a static knowledge of ultimate truth. Both also recognized the different ways a phenomenon could be explained, depending on the view taken. There can be different reasons as to why two people do the same thing, rather than a definitive truth for everyone. This line of thought extends into a type of feminism that has emerged since the work of Ruiz: intersectionality.

Intersectionality

First addressed by Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality emphasizes the intersection of race and gender, and looks at the multidimensionality of black women’s experiences rather than viewing women from a traditional single-axis analysis (p. 139). That is, factors including race and gender combine to create the full experience that an individual has. In this way, intersectionality looks at the factors to which feminist scholars have paid little attention in the past, such as race, gender, class, and sexuality (Nash, 2008). McCall (2005) explained that the traditional way of looking at disparities did not adequately summarize all subordinate groups. For example, that “white feminists’ use of women and gender as unitary and homogeneous categories” would reflect the “common essence of all women” (p. 1776). Since traditional feminism categorized men versus women, and it left no space for subcategories of white women and black women; white feminists failed to recognize the different experiences of black women.

Crenshaw (1989) argued that without taking into account all of the various interplaying variables like race, gender, class, and sexuality, one cannot adequately analyze the way black women are oppressed. This logic hints at John Dewey’s theory of pragmatism, where he suggested that there are so many ways humans can differ, and so it would not make sense to give one ultimate explanation for the behavior of everyone (Dewey, 1925). Yet, neither Dewey, nor Ruiz, specifically examined the interplay of the particular variables brought up by intersectional scholars. Ruiz recognized the different gender social contingencies without realizing the importance of interacting factors such as race, class, and sexuality on behavior. Dewey, although understanding the importance of individual differences, did not elaborate on the specific intersecting variables that contribute to these differences. Yet, the variables that Crenshaw described are essential for this understanding, and they influence behavior every day. For example, Irvine (1986) described differences in the frequency of positive feedback students received as a function of race and gender. In this study, white female students from both upper elementary and lower elementary ages received less positive feedback than did upper elementary black male students. Black female students of lower elementary ages received less positive feedback than white male lower elementary age students, and less positive feedback than black male upper elementary age students. Thus, this disparity emerges from the interaction of race and gender, potentially influencing the developmental trajectory of these individuals. As demonstrated by interventions like the Good Behavior Game, contacting positive social contingencies in early developmental periods can contribute to enduring success (cf. Embry, 2002).

Moradi and Grzanka (2017) described how, traditionally, psychologists have studied people’s experiences from a single-axis viewpoint with homogeneous samples. For example, when psychologists study LGBTQ+ individuals, these samples are mainly white. Such research does not necessarily generalize to broader populations, as experiences are framed within intersecting variables of race, gender, class, or sexual orientation. Moradi and Grzanka (2017) further explained that by reconceptualizing social categories such as race and gender as “dynamic social context variables,” psychologists can theorize how specific constructs may shape outcomes across groups and shift the “responsibility and points of intervention from the individual to the collective and to structures/systems of power” (p. 506). Put in behavioral terms, nuanced aspects of learning history that are a function of these social variables necessarily influence the behavior of the individual.

Moradi and Grzanka (2017) explained that psychologists need to critically evaluate whether their research is actually helping to promote social justice, and whether their research actually evaluates those oppressed, since psychologists have commonly researched social issues that will not generalize to the actual oppressed population. These authors concluded that intersectionality is very similar to pragmatism in that both have applied concerns. Consequently, intersectionality also applies to behavior-analytic researchers and practitioners. If applied behavior analysts recognize the multiple variables affecting an individual, they can more effectively provide interventions that support meaningful change. Realizing the multiple factors that can lead to certain behaviors may be more beneficial than just targeting a single factor.

Cole (2009) provided evidence that supported claims made by Moradi and Grzanka (2017), indicating that just asking who is included in a category can attempt to amend the years of underrepresentation of minority groups. By analyzing groups that have been overlooked in the past, psychologists can better understand their experiences, rather than just seeing them in the ways they differ from the “dominant group” norms (Cole, 2009, p. 172). Furthermore, Cole (2009) claimed that ignoring how social categories intersect makes any knowledge gained from research incomplete. For practicing behavior analysts, relevant categories may expand beyond race and gender, and include domains such as disability status or sexual orientation.

Engaging with clients as individuals with a complex learning history, including core variables that influence who they are and how they act, is crucial for cultural competence. Fong, Catagnus, Broadhead, Quigley, and Field (2016) suggested that it is important for behavior analysts to be aware of their own cultural values as well as those of their clients. Such awareness may allow behavior analysts to identify targets of intervention that are socially valid for both the client and the practitioner. These authors suggested that “without information about cultural preferences and norms, behavior analysts may unintentionally provide less than optimal service delivery” (p. 85). Specific recommendations to improve the interaction between behavior analysts and their clients is to include using culturally aware language, conducting a cultural identity assessment of the client and/or family, and using resources such as the community members to learn more about the client’s culture (Fong et al., 2016). A similar argument could be made for the interacting variables related to intersectional feminism—engaging with these variables may also be necessary to deliver effective and valid interventions. Fortunately, understanding the interaction of key categories is already at the heart of Skinner’s approach to behavior.

Intersectionality and Behavior Analysis

Skinner (1974) set the stage for the parallels between intersectionality and radical behaviorism. He emphasized how human behavior is caused by a confluence of factors, rather than assigning agency to the individual. Skinner said that a person “is a locus, a point at which many genetic and environmental conditions come together in joint effect” (Skinner, 1974, p. 168). Skinner proposed that since everyone has different personal histories and genes, everyone is vastly unique. The individual acquires a “repertoire of behavior” and “complex contingencies of reinforcement create complex repertoires” which enables a sense of “different persons in the same skin” (Skinner, 1974, p. 167). This line of thought is consistent with the approach of intersectionality. Intersectionality accepts the idea that many genetic and environmental conditions come together to make up the whole person, rather than one dominating factor. Crenshaw (1989) wrote that the “dominant conception” of discrimination erroneously makes one believe that discrimination occurs on a “single coordinate axis” (p. 140). Yet this is not the case, as race, gender, class, and sexuality create experiences specific to the individual, and that individual is then shaped by those experiences. Because the individual is made up of all these layers, it is as though there are “different persons in the same skin” that are emphasized under different contexts, or contingencies.

Another similarity between behaviorism and intersectionality is their goal to help solve social problems. Moradi and Grzanka (2017) noted that analyzing race, gender, class, and sexuality is just one part of intersectionalism, as “doing coalitional and ally work to enact resistance and activism” should be the central focus to actually help those oppressed (p. 509). Skinner (1971) argued that since major problems involve human behavior, human behavior needs to be studied to overcome those problems. Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968) suggested that for work to be considered applied behavior analysis, it must focus on promoting behavior change that is meaningful to the target individual and others around them. By being able to predict and control behavior, behavior analysts can make changes for the well-being of society by manipulating the environment (cf. Biglan, 2015). This is absolutely necessary if behavior analysts want to promote social change to prevent oppression and discrimination.

One way that behavior analysts can make a greater impact in this domain is to make their research more accessible to the general public. Of course, it is necessary for members of this field to be aware of the inequalities that certain groups face; however, communicating these thoughts to the general public is critical to making a lasting difference. Perhaps behavior analysts in schools could collaborate more with the teachers to increase their awareness of a student’s background and ways in which key variables may influence the student’s behavior. As behavior analysts develop intervention plans for clients, it may be useful to consider the variables intersectionality emphasizes to intervene in a culturally competent manner. Finally, behavior analysts need to study with diverse, generalizable samples that have not been studied in the past. Even the representation of minorities within the field of behavior analysis is unknown. Future research should explore current levels of representation and inform actions that can increase that representation to desirable levels, within both the field of practitioners, and also in the populations who are served.

Conclusions

From the outset, both behavior analysis and feminism were not as inclusive as they might have been. However, progress has been made in both disciplines, and can continue to be made. To best pursue their goal of helping to overcome social problems, each field might benefit from adopting some of the other’s perspective. Both McCall, a lead intersectionalist theorist, and Skinner, a prominent behaviorist, agree that more than just one factor should be taken into consideration to better understand the experiences of individuals. With the many gender, race, and sexual orientation biases prevalent in society today, it may be useful for behavior analysts to recognize controlling variables of these biases that have been largely disregarded in the past. By doing this, the field may continue to advance the well-being of society and increase the effectiveness of the field.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Clare Mehta and Laura Diller for their feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest associated with the publication of this manuscript, and all appropriate ethical standards have been upheld.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychological Association . Report of the task force on the changing gender composition of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2006). Women in the American Psychological Association. Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/pi/women/committee/wapa-2006.pdf.

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(1):91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Agras WS. Fading to increase heterosexual responsiveness in homosexuals. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1973;6(3):355–366. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1973.6-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB). (2016). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Retrieved from: https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/170706-compliance-code-english.pdf.

- Biglan A. The Nurture Effect: how the science of human behavior can improve our lives and our world. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan EJ, Leitenberg H. Aversion therapy for sexual deviation: Contingent shock and covert sensitization. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1973;81(1):60–73. doi: 10.1037/h0034025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics, 1989 University of Chicago legal forum.

- Dewey J. Experience and nature. New York: Norton; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Embry DD. The good behavior game: A best practice candidate as a universal behavioral vaccine. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5(4):273–293. doi: 10.1023/A:102977107086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Broadhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller, E. S. (2014). Actively caring for people: Cultivating a culture of compassion. Newport:Make-a-Difference LLC.

- Haldemann DM. The pseudo-science of sexual orientation conversion therapy. Angles. 1999;4(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Heldke L. John Dewey and Evelyn fox Keller: A shared epistemological tradition. Hypatia. 1987;2(3):129–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-2001.1987.tb01345.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine JJ. Teacher–student interactions: Effects of student race, sex, and grade level. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1986;78(1):14–21. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.78.1.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KA, Laipple JS. Pragmatism and behavior analysis. In: Lattal KA, Chase PN, editors. Behavior theory & philosophy. Boston, MA: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Curiel H, Pritchard J, Poling A. Participation of women in behavior analysis research: Some recent and relevant data. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(2):160–164. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0211-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maton KI, Kohout JL, Wicherski M, Leary GE, Vinokurov A. Minority students of color and the psychology graduate pipeline: Disquieting and encouraging trends, 1989-2003. American Psychologist. 2006;61(2):117–131. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall L. The complexity of intersectionality. Signs. 2005;30(3):1771–1800. doi: 10.1086/426800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire RJ, Vallance M. Aversion therapy by electric shock: A simple technique. British Medical Journal. 1964;1:151–153. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5376.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLay L, Carnett A, Tyler-Merrick G, van der Meer L. A systematic review of interventions for inappropriate sexual behavior of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities. Review Journal Autism Development Disorder. 2015;2:357–373. doi: 10.1007/s40489-015-0058-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney FK, Donahoe P, Swindell S. Women in applied behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23(2):267–277. doi: 10.1007/BF03392015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, Grzanka PR. Using intersectionality responsibly: Toward critical epistemology, structural analysis, and social justice activism. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2017;64(5):500–513. doi: 10.1037/cou0000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EK. Contextualism: The worldview of behavior analysis. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1988;46(3):289–323. doi: 10.1016/0022-0956(88)90063-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EK. Mechanism and contextualism in behavior analysis: Just some observations. The Behavior Analyst. 1993;16(2):255–268. doi: 10.1007/BF03392634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash JC. Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review. 2008;89:1–15. doi: 10.1057/fr.2008.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nosik Melissa R., Luke Molli M., Carr James E. Representation of women in behavior analysis: An empirical analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2019;19(2):213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag PA, McNamara JR. 'Feminization' of psychology: The changing sex ratio and its implications for the profession. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1991;15(3):349–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1991.tb00413.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rekers GA, Lovaas OI. Behavioral treatment of deviant sex-role behaviors in a male child. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1974;7(2):173–190. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1974.7-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JR, Vollmer TR, Sloman KN, Hall A, Reed R, Jansen G, et al. Assessment of deviant arousal in adult male sex offenders with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39(2):173–188. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.46-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JR, Vollmer TR, Hall A. Comparison of arousal and preference assessment outcomes for sex offenders with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50(1):27–37. doi: 10.1002/jaba.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MR. B. F. Skinner's radical behaviorism: Historical misconstructions and grounds for feminist reconstructions. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1995;19(2):161–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00285.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MR. Personal agency in feminist theory: Evicting the illusive dweller. The Behavior Analyst. 1998;21(2):179–192. doi: 10.1007/BF03391962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz MR, Roche B. Values and the scientific culture of behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst. 2007;30(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03392139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo NF, Olmedo EL, Stapp J, Fulcher R. Women and minorities in psychology. American Psychologist. 1981;36(11):1315–1363. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.36.11.1315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JL, Morris EK, Smith NG. Trends in women's participation at the meetings of the Association for Behavior Analysis: 1975-2005. The Behavior Analyst. 2007;30(2):181–196. doi: 10.1007/BF03392154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Walden two. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Beyond freedom and dignity. New York, NY, US: Knopf/Random House; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. About behaviorism. Oxford, England: Alfred A. Knopf; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. Notebooks. Eaglewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Soreth ME, Dickson CA, Terry CM. In memoriam: Maria del Rosario Ruiz. The Behavior Analyst. 2017;40(2):553–557. doi: 10.1007/s40614-017-0131-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert RS. A multicultural feminist analysis of Walden two. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2005;6(3):186–190. doi: 10.1037/h0100063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]