Abstract

Background:

Accelerated weight gain in infancy is a public health issue and is likely due to feeding behaviors.

Objectives:

To test the accuracy of individuals to dispense infant formula as compared to recommended serving sizes and to estimate the effect of dispensing inaccuracy on infant growth.

Methods:

Fifty-three adults dispensed infant formula powder for three servings of 2, 4, 6 and 8 fl oz bottles, in random order. The weight of dispensed infant formula powder was compared to the recommended serving size weight on the nutrition label. A novel mathematical model was used to estimate the impact of formula dispensing on infant weight and adiposity.

Results:

Nineteen-percent of bottles (20/636) prepared contained the recommended amount of infant formula powder. Three-percent were under-dispensed, and 78% of bottles were over-dispensed resulting in 11% additional infant formula powder. Mathematical modeling feeding 11% above energy requirements exclusively for 6 months for male and female infants suggested infants at the 50th percentile for weight at birth would reach the 75th percentile with increased adiposity by 6 months.

Conclusions:

Inaccurate measurement of infant formula powder and over-dispensing, which is highly prevalent, specifically, may contribute to rapid weight gain and increased adiposity in formula fed infants.

Keywords: Infant formula, feeding, infant growth, infant adiposity, mathematical modeling

Introduction

Diet and feeding practices early in life impact risk for childhood obesity and chronic diseases in adulthood such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease1,2. The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding until six months of age, however over 80% of infants in the U.S. receive infant formula in addition to human milk or as the sole source of nutrition prior to their six month birthday3.

Despite an almost identical energy density between infant formula and breast milk, formula fed infants experience greater weight gain in the first year of age than exclusively breastfed infants4,5. Potential mechanisms linking infant formula feeding to greater weight gain include lower levels of feeding self-regulation and increased appetite due to differences in sucking biomechanics between the bottle and breast6–8, tendencies for bottle emptying9–11, differences in infant gut microbiome12,13, differences in established feeding practices 14,15, and parental attitudes towards infant feeding14. Given majority of infants in the U.S. consume infant formula partially or solely in the first year of age and that infant formula is distributed to low-income families nationally in federal and state nutrition programs, it is surprising that public resources dedicated to proper formula preparation are limited and vary in their information. To our knowledge, no studies have considered the ability of adults to accurately dispense infant formula powder and to understand the implication of formula dispensing on weight gain or adiposity. We conducted a cross-sectional study to assess the accuracy of infant formula powder dispensing in caregivers and non-caregivers, and, post-hoc, we modeled the implications of inaccurate infant formula dispensing on body weight trajectories over the first six months of age.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Individuals were recruited through advertisements and targeted emails directed to residents of the Greater Baton Rouge area from November 2012 to March 2013. The study was reviewed and approved by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Institutional Review Board and was registered as a clinical trial named Remote Food Photography Method in Infants (NCT01762631) prior to the enrollment of the first subject. Fifty-three men and women aged 18 or older were recruited as part of Cohort 1 to prepare bottles of infant formula Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge, Louisiana16,17. Participants who enrolled in Cohort 2 (n=22) of the study were not included in this investigation because infant formula powder was not directly weighed in the Cohort 2 protocol. Participants self-identified as a caregiver (an individual who had provided care for an infant in the past year), or a non-caregiver. Both caregivers and non-caregivers were recruited to allow for examination of differences in bottle preparation behaviors between the two groups, to make the study findings more generalizable, and to ensure the findings would not be biased by behaviors of caregivers who are experienced in infant bottle preparation. Written informed consent was obtained by all participants prior to the initiation of procedures, and compensation was provided for completion of study procedures.

Study Measurements

Non-fasting body weight was measured in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg on a calibrated scale (GSE, Livonia, Michigan, United States). Height was measured using a stadiometer (Holtain Limited, Crymych, United Kingdom) without shoes to the nearest 0.1 cm. Body mass index was calculated from body weight and height at the first visit. In addition, other demographic characteristics including age, sex, and race were collected. At two visits to the metabolic kitchen approximately one week apart, participants used a commercially-available infant formula powder to prepare 12 bottles that provided three servings of a 2 fl oz, 4 fl oz, 6 fl oz and 8 fl oz bottle. Two bottles of each serving size were prepared at Visit 1, and one bottle in each serving size was prepared at Visit 2. The order of bottle preparation at each visit was assigned at random. Participants were provided with infant feeding bottles, water and a canister of commercially available infant formula powder which contained the measuring scoop provided by the manufacturer. Participants received the same scripted instructions from study staff. Subjects were instructed to use the packaging instructions as needed to aid in their preparation of the bottles. Study staff did not provide any coaching or guidance. After the infant formula powder was dispensed into each bottle, the bottle was weighed on a calibrated electronic scale (Mettler Toledo PB3001, Columbus, OH) not in view of the subject. At the completion of the entire study, the weight of the dispensed infant formula powder was compared to the recommended serving size weight provided on the nutrition label. Formula dispensing was considered accurate when the gram weight of the dispensed infant formula powder was within ± 5% of the gram weight suggested for each serving size. Bottles were thereby defined as under-dispensed and over-dispensed when the gram weight was <5% or >5% of the gram weight suggested for each serving size, respectively.

Mathematical Modeling and Infant Weight Gain Simulations

Using a previously published mathematical model of human energy balance dynamics and childhood growth from age 5 years to adulthood18 as a starting point, we developed a new model that simulates body weight and composition dynamics for individuals from birth through adulthood (fully described in Supporting Information). This new model was used to simulate the effects of the potential dispensing error observed in the laboratory dispensing study on infant weight and adiposity compared to the energy intake corresponding to the reference body weight, length, and composition in females and males over the first 6 months of age using the WHO Child Growth Standards 19.

Statistical Analysis

A linear mixed model for repeated measures was used to investigate effects on error in dispensing of formula, with fixed effects for serving size, study trial, and the 2-way interaction, and a random subject effect to account for intra-individual correlations. Group differences in the prevalence of dispensing error based on demographic characteristics (caregiver status, sex, BMI, age, and race) were analyzed via chi square tests. Using the potential dispensing error observed in the laboratory dispensing study, estimates of infant weight and percent body fat were simulated in our infant energy balance model using Monte Carlo simulations. Ten thousand random samples were drawn from a normal distribution of the observed mean and standard deviation of percent dispensing error in the 636 bottles prepared in the laboratory in this study. Ten thousand random samples were drawn from a normal distribution of 0% dispensing error with the observed standard deviation for normal feeding and weight at the 50th percentile for both females and males. The uncertainty was obtained by calculating the mean and standard deviation of predicted body weight and percent body fat estimates. Infant weight estimates from the WHO Child Growth Standards19 and the infant weight estimates simulated from dispensing error in our infant energy balance model were used in mixed models to compare weight and percent body fat at 6 months of age for female and male infants with significance set at p<0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. Study participants were predominantly female and Caucasian, with ages ranging from 18 to 71 years and a median age of 29. Study participants were varied in caregiver status and BMI ranged across all classifications.

Table 1:

Demographics of study participants (n=53)

| Age, yr | 29 (18, 71) |

| BMI Classification | |

| Underweight | 1 (1.9) |

| Normal weight | 32 (60.4) |

| Overweight | 7 (13.2) |

| Obese | 13 (24.5) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 39 (73.6) |

| African American | 9 (17.0) |

| Other | 5 (9.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 6 (11.3) |

| Female | 47 (88.7) |

| Caregiver Status | |

| Caregiver | 28 (52.8) |

| Non-caregiver | 25 (47.2) |

Values are expressed as median (minimum, maximum) for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

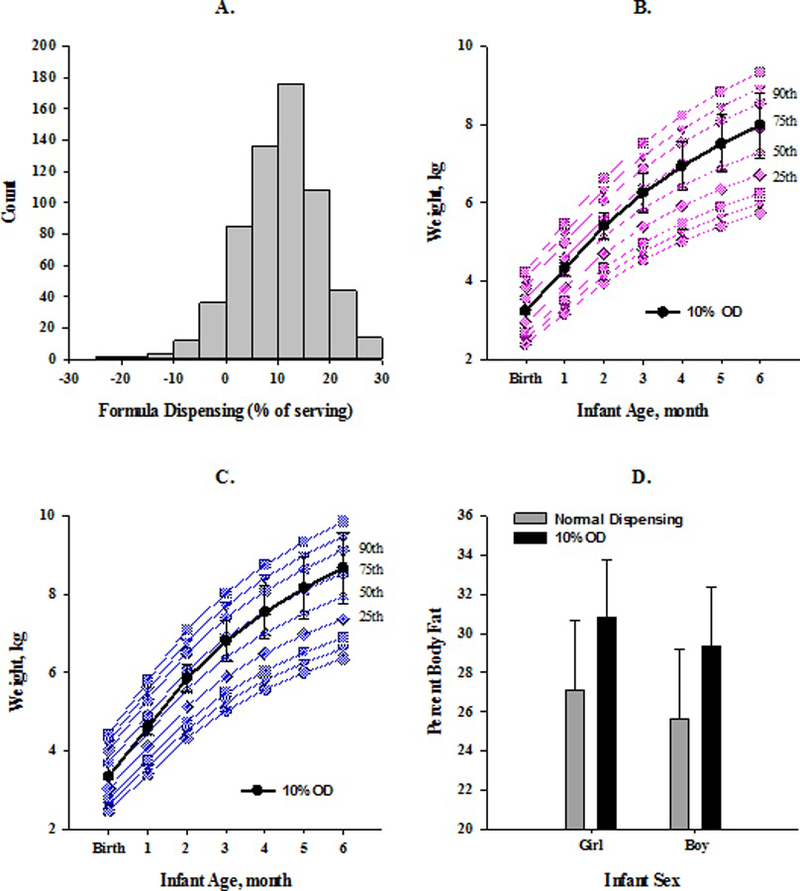

Of the 636 bottles of infant formula that were prepared under standardized conditions (Figure 1A), 20 (3%) bottles were under-dispensed, 121 (19%) were accurately dispensed and 495 (78%) were over-dispensed when compared to the recommended weight on the nutrition label. The distribution of formula dispensing was uniform across the four different serving sizes (p=0.44), and the three trials (p=0.17) and was not influenced by the order of bottle preparation (p=0.33). In addition, the distribution of formula dispensing was not statistically different between Visit 1 and Visit 2 (p=0.06). The prevalence of over-dispensing was higher in caregivers compared to non-caregivers (82% vs 73% respectively, p<0.01) and males compared to females (89% vs 76% respectively, p=0.02). Individuals with BMI <25.0 kg/m2 had higher prevalence of over-dispensing as compared to individuals with BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (81% vs 73% respectively, p=0.03), and individuals aged 29 or younger had higher prevalence of over-dispensing as compared to individuals aged 30 or older (83% vs 72%, p<0.001). There were no differences between Caucasians and non-Caucasians in over-dispensing (p=0.55).

Figure 1.

The observed prevalence of infant formula powder dispensing error (A) and mathematically modeled impact of 11% over-dispensing on infant weight trajectories19 (B – female, C - male) and percent body fat at 6 months of age (D). Data are shown as mean ± SD. OD= over-dispensing

Considering all 636 bottles, the magnitude of over-dispensing resulted in an additional 11% of infant formula powder dispensed in each bottle, regardless of the planned serving size. However, in only those bottles that were over-dispensed (n=495) an additional 14% of infant formula powder was added. Assuming accurate water dispensing and complete bottle emptying by infants, extrapolating the 11% over-dispensing occurring at a single meal to all meals expected during a day for exclusively formula fed infants from birth to 6 months (Table 2) would amount to almost an additional day of food per week.

Table 2:

Representation of Infant Energy Needs and Estimated Impact of Observed Over-dispensing Infant Formula Powder on Daily Energy Intake.

| Infant Age | Serving Size (Fl oz)* | Servings per Day* | Daily Intake (Kcal) | % Over-dispensed§ | Daily Intake with Over-dispensing (Kcal/Day)# | Weekly Intake with Over-dispensing (Kcal/Week)# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn | 2 | 6 | 320 | 12 | 38 | 266 |

| 2 Months | 4 | 6 | 480 | 11 | 53 | 371 |

| 4 Months | 6 | 4 | 600 | 11 | 66 | 462 |

| 6 Months | 8 | 4 | 640 | 11 | 70 | 490 |

Serving size and number of servings per day as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics29

Average observed infant formula powder over-dispensing for each bottle size.

Estimated impact of the observed infant formula powder over-dispensing on daily energy intake.

Fl oz= fluid ounce, Kcal= kilocalories

Using a novel dynamic energy balance model of infant growth (Supporting Information), we simulated the impact of the dispensing error observed in the laboratory dispensing study (11.13±9.75%) daily for a female (Figure 1B) and male (Figure 1C) infant with normal birth weight (50th percentile) on body weight change from birth to 6 months on the WHO Child Growth Standards chart 19. In comparison to an infant eating in accordance with their daily energy requirements and sustaining weight gain at the 50th percentile 19, a female infant consuming meals containing 11% more formula powder would have increased weight gain of 114 g/month. Similarly, a male infant consuming meals containing 11% more formula powder would have increased weight gain of 123 g/month. At 6 months of age, the hypothetical female would have a body weight of 7,981 g corresponding to the 76th percentile own the WHO Child Growth Standards chart compared to 7,297 g for the reference female at the 50th percentile (p<0.01, Figure 1B). In the hypothetical male, body weight at 6 months of age would be 8,671 g corresponding to the 78th percentile compared to 7,934 g for the reference male at the 50th percentile (p<0.01, Figure 1C). Furthermore, female and male infants consuming meals containing 11% more formula powder daily would have a higher percent of body fat compared to their birth weight and length- matched counterparts consuming infant formula in accordance with manufacturer serving sizes at 6 months of age (Females: 30.81±2.96% vs 27.10±3.59% p<0.01, Males: 29.33±3.01% vs 25.61±3.58% p<0.01, Figure 1D).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study provides compelling observational evidence as to the potential prevalence and magnitude of over-dispensing of infant formula powder and its impact on weight gain in infants fed infant formula partially or solely. Despite food intake early in life being fairly universal, there is a discordance of infant growth between formula fed and breastfed infants4,5. Indeed, research has uncovered many factors that may explain the exaggerated growth trajectories for formula fed infants; yet one area less studied is the role of the caregiver in meal preparation.

In nutrition literature it is well described that humans are inaccurate at measuring food portions20. However at a time during early development when people are considered the most vulnerable to their environment, one of the most prevalent food sources, infant formula, requires human measurement for preparation. Inaccurate portion size estimation in adults has been linked to low levels of health literacy in the comprehension of nutrition labels, but this is primarily attributed to vast differences in serving sizes across food items21. Fortunately, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandate strict instructions for labeling on infant formula, including instructions on dispensing infant formula powder and bottle preparation using pictographs. A recent study found that commercial infant formula powder labels do not meet plain language guidelines, and the directions for formula preparation have an average reading and comprehension level equivalent to a college education22. It is also documented that parents with low health literacy are more likely to feed with infant formula23. Similarly, medication dispensing in parents with a low level of health literacy is poor24 but has been improved with the use of standardized labeling and pictographs in conjunction with provider counseling25.

Since both water and formula powder are dispensed to prepare reconstituted infant formula, both contents may be dispensed inaccurately and thus may affect the energy density of the formula contained in the bottle. If the entire contents of a bottle prepared with formula powder and water is consumed, the amount of formula powder alone represents the kilocalorie intake; but, indeed, if bottles are not entirely consumed, kilocalorie intake can be varied due to the amount of water added. It has been shown that potential dispensing error of water may be due to inaccurate volume markers on the infant bottle26. Though, we provided measuring cups to all participants. Water dispensing was investigated, but we focused on simulating the effects of formula dispensing error.

This study uncovers the potential for providing infants with meals containing additional infant formula unintentionally due to over-dispensing infant formula powder and provides new explanation for accelerated weight gain trajectories in formula fed infants. Since bottle-fed infants and infants younger than 6 weeks27 are less likely to self-regulate feeding patterns6,9,28, and caregivers are more likely to insist on bottle emptying10,11, it seems plausible to hypothesize that increased caloric density in early life might program poor self-regulation and increased appetite in children as complementary foods are introduced.

An important strength of this study was the inclusion of adults with diverse backgrounds including whether or not they were currently a caregiver for an infant. One could hypothesize that caregivers are more accurate in bottle preparation than non-caregivers, but alternatively, caregivers, who are familiar with bottle preparation, may be more relaxed with their approach and have less accurate formula dispensing. The findings are thereby generalizable to all demographic groups and allow for comparisons in dispensing accuracy between demographic groups. The current study demonstrated that individuals who self-identify as caregivers, are male, younger, and with BMI less than 25 kg/m2, may be at higher risk for over-dispensing infant formula powder. The prevalence of over-dispensing shown in these specific demographic characteristics, which describe many parents and caregivers of young children, highlights the importance of portion estimation in infant formula powder dispensing and the necessity for appropriate formula instructions and education for parents and other caregivers.

Certainly, the chief limitation of this cross-sectional research study was that infants were not provided the bottles which were prepared and hence the simulations assume that infants would have normal bottle emptying behaviors and therefore overconsume calories due to over-dispensing, regardless of the increase in caloric density of the formula. In addition, this study was conducted in a controlled laboratory setting so scooping behavior may differ in a free-living environment.

This study highlights the necessity for research on nutritional health literacy and infant formula feeding. Evidence-based programs designed to educate caregivers on the importance of infant feeding need to be developed and tested to address excess weight gain early in life, particularly in health disparate populations that are the highest consumers of infant formula and have infants and children with the highest rates of overweight and obesity. Finally, the distribution of infant formula powder as a pre-packaged portion requires consideration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding Source

This work was supported in part by a Nutritional Obesity Research Center Grant (P30DK072476) and the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center (1U54GM104940). JG, DR, CC, DT, AG, and KDH were supported by the Intramural Research

Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Abbreviations:

- Fl oz

fluid ounce

- U.S.

United States

- WHO

World Health Organization

- Kcal

kilocalories

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and analyzed for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Zheng M, Lamb KE, Grimes C, et al. Rapid weight gain during infancy and subsequent adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence. Obes Rev 2018;19(3):321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plagemann A, Harder T, Schellong K, Schulz S, Stupin JH. Early postnatal life as a critical time window for determination of long-term metabolic health. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;26(5):641–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. National Immunization Surveys 2012 and 2013 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm.

- 4.Li R, Magadia J, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Risk of bottle-feeding for rapid weight gain during the first year of life. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 2012;166(5):431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell KA, Wagner CL, Feldman HA, Shypailo RJ, Belfort MB. Associations of infant feeding with trajectories of body composition and growth. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106(2):491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ventura AK, Inamdar LB, Mennella JA. Consistency in infants’ behavioural signalling of satiation during bottle-feeding. Pediatric obesity 2015;10(3):180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pados BF, Park J, Thoyre SM, Estrem H, Nix WB. Milk flow rates from bottle nipples used for feeding hospitalized infants. American journal of speech-language pathology / American Speech-Language-Hearing Association 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Fewtrell MS, Kennedy K, Nicholl R, Khakoo A, Lucas A. Infant feeding bottle design, growth and behaviour: results from a randomised trial. BMC research notes 2012;5:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li R, Fein SB, Grummer-Strawn LM. Do infants fed from bottles lack self-regulation of milk intake compared with directly breastfed infants? Pediatrics 2010;125(6):e1386–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ventura AK, Teitelbaum S. Maternal Distraction During Breast- and Bottle Feeding Among WIC and non-WIC Mothers. J Nutr Educ Behav 2017;49(7S2):S169–S176 e161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li R, Scanlon KS, May A, Rose C, Birch L. Bottle-feeding practices during early infancy and eating behaviors at 6 years of age. Pediatrics 2014;134 Suppl 1:S70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forbes JD, Azad MB, Vehling L, et al. Association of Exposure to Formula in the Hospital and Subsequent Infant Feeding Practices With Gut Microbiota and Risk of Overweight in the First Year of Life. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172(7):e181161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savage JH, Lee-Sarwar KA, Sordillo JE, et al. Diet during Pregnancy and Infancy and the Infant Intestinal Microbiome. J Pediatr 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Brown A, Raynor P, Lee M. Maternal control of child-feeding during breast and formula feeding in the first 6 months post-partum. J Hum Nutr Diet 2011;24(2):177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golen RB, Ventura AK. Mindless feeding: Is maternal distraction during bottle-feeding associated with overfeeding? Appetite 2015;91:385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duhe AF, Gilmore LA, Burton JH, Martin CK, Redman LM. The Remote Food Photography Method Accurately Estimates Dry Powdered Foods-The Source of Calories for Many Infants. J Acad Nutr Diet 2016;116(7):1172–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altazan AD, Gilmore LA, Burton JH, et al. Development and Application of the Remote Food Photography Method to Measure Food Intake in Exclusively Milk Fed Infants: A Laboratory-Based Study. PLoS One 2016;11(9):e0163833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall KD, Butte NF, Swinburn BA, Chow CC. Dynamics of childhood growth and obesity: development and validation of a quantitative mathematical model. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013;1(2):97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. Complementary feeding in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatr Suppl 2006;450:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almiron-Roig E, Solis-Trapala I, Dodd J, Jebb SA. Estimating food portions. Influence of unit number, meal type and energy density. Appetite 2013;71:95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med 2006;31(5):391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace LS, Rosenstein PF, Gal N. Readability and Content Characteristics of Powdered Infant Formula Instructions in the United States. Matern Child Health J 2016;20(4):889–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin HS, Sanders LM, Rothman RL, et al. Parent health literacy and “obesogenic” feeding and physical activity-related infant care behaviors. J Pediatr 2014;164(3):577–583 e571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lokker N, Sanders L, Perrin EM, et al. Parental misinterpretations of over-the-counter pediatric cough and cold medication labels. Pediatrics 2009;123(6):1464–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin HS, Dreyer BP, van Schaick L, Foltin GL, Dinglas C, Mendelsohn AL. Randomized controlled trial of a pictogram-based intervention to reduce liquid medication dosing errors and improve adherence among caregivers of young children. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 2008;162(9):814–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gribble K, Berry N, Kerac M, Challinor M. Volume marker inaccuracies: A cross-sectional survey of infant feeding bottles. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fomon SJ, Filer LJ Jr., Thomas LN, Rogers RR, Proksch AM. Relationship between formula concentration and rate of growth of normal infants. J Nutr 1969;98(2):241–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ventura AK, Mennella JA. An Experimental Approach to Study Individual Differences in Infants’ Intake and Satiation Behaviors during Bottle-Feeding. Child Obes 2017;13(1):44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Academy of Pediatrics. The Complete and Authoritative Guide: Caring For Your Baby And Young Child Birth to Age 5 Sixth Edition ed: Bantam Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.