Abstract

Aims:

Type 2 diabetes is a heterogeneous disease and may manifest from multiple disease pathways. We examined insulin secretion and insulin resistance across two ethnicities with particularly high risk for diabetes yet with widely different distributions of weight class.

Materials and Methods:

In this population-based, cross-sectional study, Pima Indians from Southwestern United States (n=865) and Asian Indians from Chennai, India (n=2,374) had a 75g oral glucose tolerance test. We analyzed differences in plasma glucose, plasma insulin, insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and insulin secretion (ΔI0-30 /ΔG0-30) across categories of body mass index (BMI) and glycemic status per American Diabetes Association criteria.

Results:

Pima Indians were younger (mean 27.4 ± SD 6.6, Asian: 33.9 ± 6.7 years) and had higher BMI (33.6 ± 8.1, Asian: 25.7 ± 4.9 kg/m2). Among normal weight participants (mean BMI: Pima 22.4 SE 0.2; Asian 22.2 SE 0.06 kg/m2), fasting glucose was higher in Asian Indians (5.2 vs. Pima: 4.8 mmol/L, p=0.003), adjusted for age and sex. Pima Indians were 3 times as insulin resistant as Asian Indians (HOMA-IR: 7.7 SE 0.1, Asian: 2.5 SE 0.07), while Asian Indians had three times less insulin secretion (Pima: 2.8 SE 1.0 vs. Asian: 0.9 SE 1.0 pmol/mmol), a pattern evident across age, BMI, and glycemic strata.

Conclusions:

Metabolic differences between Pima and Asian Indians suggest heterogeneous pathways of type 2 diabetes in the early natural history of disease, with emphasis of insulin resistance in Pima Indians and emphasis of poor insulin secretion in Asian Indians.

Keywords: insulin resistance, insulin secretion, epidemiology, pathophysiology, type 2 diabetes, ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

While type 2 diabetes commonly leads to increased lifetime occurrence of co-morbidities and medical costs,1 the biological pathways leading to diabetes can vary, including the relative roles of beta-cell function (eg, amount of insulin produced relative to the body’s needs) and insulin resistance (eg, effectiveness of insulin across the body’s tissues).2,3 Variations in diabetes mechanisms appear linked to unique clusters of individuals who have different trajectories toward specific diabetes complications or who have different levels of success from a given therapy.4,5 Identifying disease clusters in the early natural history of diabetes, before diabetes onset, may illuminate opportunities to more effectively respond to phenotypic heterogeneity.

The study of phenotypes in nondiabetic individuals is complementary to disease-focused discovery. BMI phenotypes have been examined in obese-prone populations, however, examining populations with diverse BMI distributions globally may improve understanding of diabetes susceptibility. Two ethnicities are particularly varied in their BMI distributions. Pima Indians, who have among the highest reported prevalence levels of diabetes worldwide over the last 50 years, have high levels of obesity and insulin resistance compared to other ethnic groups6,7, which may be due to both innate susceptibility as well as lifestyle8. In stark contrast, Asian Indians generally exhibit a thin body mass index (BMI) phenotype with high risk of diabetes9, experiencing a high prevalence levels of type 2 diabetes and at lower BMI levels10 compared to other ethnic groups.

For the present study, our objective was to examine diabetes pathophysiology across a varied landscape of anthropometry. We examined population-based data from Pima Indians and Asian Indians, two populations with dramatically different BMI distributions, yet both considered high-risk populations for diabetes development. We characterized insulin secretion and insulin resistance within each population and across stages in the natural history of diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population.

Study participants in this analysis originated from two population samples. Pima Indian adults (n=865) aged 18-45 years were recruited (1982-1998) for a from population-based study in a reservation community of the Southwestern, USA which included inpatient studies of insulin resistance measured by the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic “clamp”11,12. Individuals with previously diagnosed diabetes were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Asian Indian participants (n=2,374) in the Centre for cArdiometabolic Risk Reduction in South-Asia Surveillance Study (CARRS) were non-pregnant adults aged 20 years or more in 201113. A representative sample from the 5 million urban and semi-urban residents of Chennai, India were selected through multi-stage cluster random sampling. Response rates were 94.7% for questionnaire completion and 84.3% for bio-specimens14. All CARRS-Chennai participants 20-45 years of age with recorded weights and heights were included in the present analysis, and individuals with previously diagnosed diabetes were not included. CARRS received approval for human subjects’ research from the ethics committees of the Madras Diabetes Research Foundation (MDRF) and Emory University. All subjects provided informed consent.

Study Procedures.

Pima Indian and Asian Indian participants were surveyed for demographics (age, sex) and anthropometrics (weight, height, waist circumference). Across both populations, weight was recorded after shoes were removed. Height was measured with a stadiometer with subjects standing upright without shoes. BMI was calculated as mass (kg) / height squared (m2). In Pima Indians, waist circumference was measured at the umbilicus, and in Asian Indians, at the smallest horizontal girth between the costal margins and the iliac crests.

In both Pima Indians and Asian Indians, a standard 75-g OGTT was performed after an overnight fast of at least 8 hours. Plasma glucose and insulin were sampled at 0, 30, and 120 minutes. Plasma glucose concentration was measured by the glucose oxidase method in Pima Indians and hexokinase method in Asian Indians. To validate measures, glucose assays from the MDRF laboratory were exchanged and evaluated against a U.S. reference laboratory, the Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories (NWRL). High concordance for glucose was found; values ranged from 3.8 to 10.1 mmol/L, (n = 20, y = 1.03x – 1.8), the correlation, r, was 0.996, and the % bias ranged 0.5 to 5.5%.

Plasma insulin concentrations in Pima Indians were determined by two different insulin assays over the course of data collection: (a) the modification of Yalow and Berson’s radioimmunoassay through charcoal method15 from 1982-1987 and (b) the Concept 4 analyzer (Concept 4 ICN, Costa Mesa, CA) from 1987-1998. Pima study investigators used a regression equation, derived among individuals in whom both assays had been performed, to make values comparable across assays. Among Asian Indians, serum insulin concentrations were estimated using electrochemiluminescence (COBAS E 411, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Initial samples ranged in insulin concentration from 24.0 to 1,902.0 pmol/L (n=29, y = 0.98x – 3.90, r=0.945) with a mean 13.5% bias (range: 1.1% to 25.0%). The second set of samples ranged from 43.2 to 2,574.0 pmol/L, and the correlation was further improved (n = 30, r = 0.997, y = 1.04x + 0.2) with an average bias of 5.5% (range: 0.1% to 18.0%).

Key Variables.

Classification of glycemic status followed American Diabetes Association criteria16: (a) diabetes as fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 7.0 mmol/l (126 mg/dl) and/or 2-hour plasma glucose (2hPG) ≥ 11.1 mmol/l (200 mg/dl); (b) isolated impaired fasting glucose (iIFG) as FPG 5.6–6.9 mmol/l (100-125 mg/dl) and 2hPG < 7.8 mmol/l (140 mg/dl); (c) isolated impaired glucose tolerance (iIGT) as FPG <5.6 mmol/l (100 mg/dl) and 2hPG 7.8 –11.0 mmol/l (140-199 mg/dl); (d) normal glucose metabolism as FPG <5.6 mmol/l (100 mg/dl) and 2hPG < 7.8 mmol/l (140 mg/dl); and (e) combined IFG and IGT (IFG+IGT), as FPG 5.6–6.9 mmol/l (100-125 mg/dl) and 2hPG 7.8 –11.0 mmol/l (140-199 mg/dl). Prediabetes was defined as iIFG, iIGT, or IFG+IGT.

Early phase insulin secretion was assessed by the insulinogenic index, a measure of the early insulin response in the OGTT calculated as the ratio of change in insulin to the change in glucose from 0 to 30 minutes [ΔInsulin0-30 /ΔGlucose0-30], and individuals having a negative or zero value for the insulinogenic index were excluded from the analysis.35 Insulin resistance was estimated using HOMA (HOMA-IR = [fasting insulin x fasting glucose]/22.5)17. The modified Matsuda Index for whole body insulin sensitivity was calculated using: (10,000/square root of [fasting glucose x fasting insulin] x [mean glucose x mean insulin]), with mean glucose and insulin calculated from values at 0, 30 and 120 minutes of the OGTT18. Overweight and obese were defined as 25.0 ≤ BMI < 30.0 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2, respectively19. Waist circumference was dichotomized for overweight status (men: waist ≥ 90 cm, women: ≥ 80 cm)20.

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We compared metabolic characteristics between ethnic groups (e.g., glucose, insulin, insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity) using two-sided T-tests and ANOVA, including the Tukey test for multiple comparisons. Non-normally distributed variables were log transformed as required to meet assumptions for regression. Age, BMI, and waist circumference were examined as continuous and categorical variables. Data were expressed as arithmetic mean (SD) in crude models and least squares mean (SE) for multivariate linear models. Since the insulin assays were not standardized across populations, levels of insulinemia may not be directly comparable. Therefore, to assess the relative contributions of insulin secretion and insulin resistance across ethnicities, Fisher’s Z transformation was used to compare Pima Indians and Asian Indians on partial correlations between blood glucose (FPG or 2hPG) and measures of insulin resistance and insulin secretion; to avoid overlap between the outcome and predictor variables, for these analyses we used fasting insulin as a measure of insulin resistance and the 30-minute corrected insulin response (CIR30 = Insulin30*100/Glucose30 (Glucose30-70)) as a measure of insulin secretion21. To further evaluate the relative contribution of insulin resistance or insulin secretion to categories of dysglycemia, HOMA-IR and insulinogenic index were standardized within each ethnicity, and multivariate multinomial logistic models were fit for the associations of these standardized insulin secretion and insulin resistance variables with glycemic outcomes, (i.e., prediabetes and diabetes compared with normoglycmia). Regression coefficients for these standardized variables were compared between Pima Indians and Asian Indians based on their standard errors; the p-values for population differences for prediabetes and diabetes were combined using a Z-transformation method to produce a summary test of the population difference in effect22. These analyses helped assess the extent to which relative within-population ranks for insulin resistance and insulin secretion variables associate differently with dysglycemia in Pima Indians versus Asian Indians.

RESULTS

The Pima Indian population had less normoglycemia (Pima 64.2% vs. Asian 71.7%, p<0.0001) and more prediabetes (Pima 29.6% vs. Asian 21.9%, p<0.0001). We found antithetical distributions of prediabetes subtypes, iIFG and iIGT, across the ethnicities; Pima Indians had more iIGT (17.7% versus Asian: 2.9%, p<0.0001), and Asian Indians had more iIFG (Pima: 5.4% versus Asian: 15.0%, p<0.0001). The prevalence of iIGT+iIFG was 6.5% in Pimas and 4.0% in Asian Indians (p=0.003). Both ethnicities had ~6% newly diagnosed diabetes (Pima n=54, 6.2% vs. Asian n=152, 6.4%, p=0.87). Pima Indians had a greater percentage of females (56.1% female); were younger (mean age 27.4 years, SD 6.6); and were more obese (mean BMI 33.6 kg/m2, SD 8.1) than Asian Indians (36.4% female, mean age 33.9 years, SD 6.7; mean BMI 25.7 kg/m2, SD 4.9; each p<0.0001).

After adjustment for age, sex, and BMI, Pima Indians had significantly higher 2hPG values (6.8 versus 6.2 mmol/L; or in conventional units, 122 vs. 112 mg/dL, see Table 1) than Asian Indians and were significantly more insulin resistant (HOMA-IR 7.7 vs. Asian HOMA-IR 2.5). The insulinogenic index was greater in Pima Indians versus Asian Indians (2.8 versus 0.9 pmol/mmol), even after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI. These differences in mean insulinogenic index remained after further adjustment for HOMA-IR (Pima: 2.7 versus Asian: 0.9 pmol/mmol, p<0.001). However, Pima Indians had significantly lower FPG values than Asian Indians (4.9 versus 5.4 mmol/L; 88 versus 97 mg/dL). Pima Indians also had lower mean 30 minute glucose (7.9 versus 8.7 mmol/L; or 142.3 versus 156.7 mg/dL). Concomitantly, Asian Indians exhibited significantly lower fasting and 30 minute insulin levels (Pima: 204.5 and 1242.5 pmol/L versus Asian: 60.4 and 411.6 pmol/L, respectively). The partial correlations between FPG and CIR30 were not different between populations, even after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, and fasting insulin (p=0.19, Appendix Table 1). However, the partial correlation between 2hPG and fasting insulin was significantly larger in Pima Indians compared to Asian Indians after adjustment for age and sex (P=.0001) and after further adjustment for BMI and CIR30 (P=.0007).

Table 1.

Metabolic characteristics in two ethnicities at high risk for type 2 diabetes

| Characteristic | PIMA INDIAN n=865 | ASIAN INDIAN n=2374 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normoglycemia, n (%) | 555 (64.2) | 1701 (71.7) | <0.0001 | ||

| iIFG, n (%) | 47 (5.4) | 357 (15.0) | <0.0001 | ||

| iIGT, n (%) | 153 (17.7) | 69 (2.9) | <0.0001 | ||

| IFG+IGT, n (%) | 56 (6.5) | 95 (4.0) | 0.003 | ||

| Newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 54 (6.2) | 152 (6.4) | 0.87 | ||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | P | |

| Waist circumference (cm)1 | 94.4 | 0.3 | 87.0 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.9 | 0.05 | 5.4 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| 30 min glucose (mmol/L) | 7.9 | 0.1 | 8.7 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| 2 hour glucose (mmol/L) | 6.8 | 0.1 | 6.2 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 204.5 | 2.7 | 60.4 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| 30 min insulin (pmol/L) | 1242.5 | 20.8 | 411.6 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| 2 hour insulin (pmol/L) | 1014.8 | 22.2 | 338.1 | 11.9 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR (uIU*mmol/L2) | 7.7 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| modified Matsuda Index ((L2)/mmolglu x pmolins) | 8.1 | 0.4 | 20.4 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Insulinogenic Index (pmol/mmol)2 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

Least squares means and standard errors are adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index. For conventional units: waist (1 inch = 2.54 cm); glucose (1 mg/dL = 0.05551 mmol/L); insulin (1 uIU/ mL = 6.0 pmol/L). Abbreviations: IFG, Impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; iIFG, isolated IFG; iIGT, isolated IGT.

Missing waist circumference data for seven Pima Indians and 46 Asian Indians.

Geometric means and geometric standard errors provided.

Metabolic characteristics adjusted for age and sex were quantified across BMI categories in Appendix Table 2. Within the BMI category of normal weight, where mean BMI was nearly identical across ethnicities (Pima Indian 22.4 and Asian Indian 22.2 kg/m2), FPG was over 8% higher in Asian Indians (Pima: 4.8 versus Asian: 5.2 mmol/L, or in conventional units, Pima: 86.5 mg/dL versus Asian: 93.7 mg/dL, p=0.003). However, 2hPG was higher in Pima Indians (6.2 versus Asian: 5.6 mmol/L, or 111.7 versus 100.9 mg/dL, p=0.001). In addition, mean insulin values across OGTT time points were consistently lower in Asian Indians compared to Pima Indians, with the insulinogenic index of Asian Indians half that of the Pima Indians (Pima 2.1 versus Asian 1.0 pmol/mmol, p<0.001). Pima Indians were more insulin resistant (Pima HOMA-IR: 4.3 versus Asian: 1.7 mg*uIU/L, p<0.001). These differences were also observed across overweight and obese strata, with Pima Indians having greater levels of 2hPG and insulin resistance compared to Asian Indians, while for Asian Indians, FPG was consistently greater and insulinogenic index consistently lower.

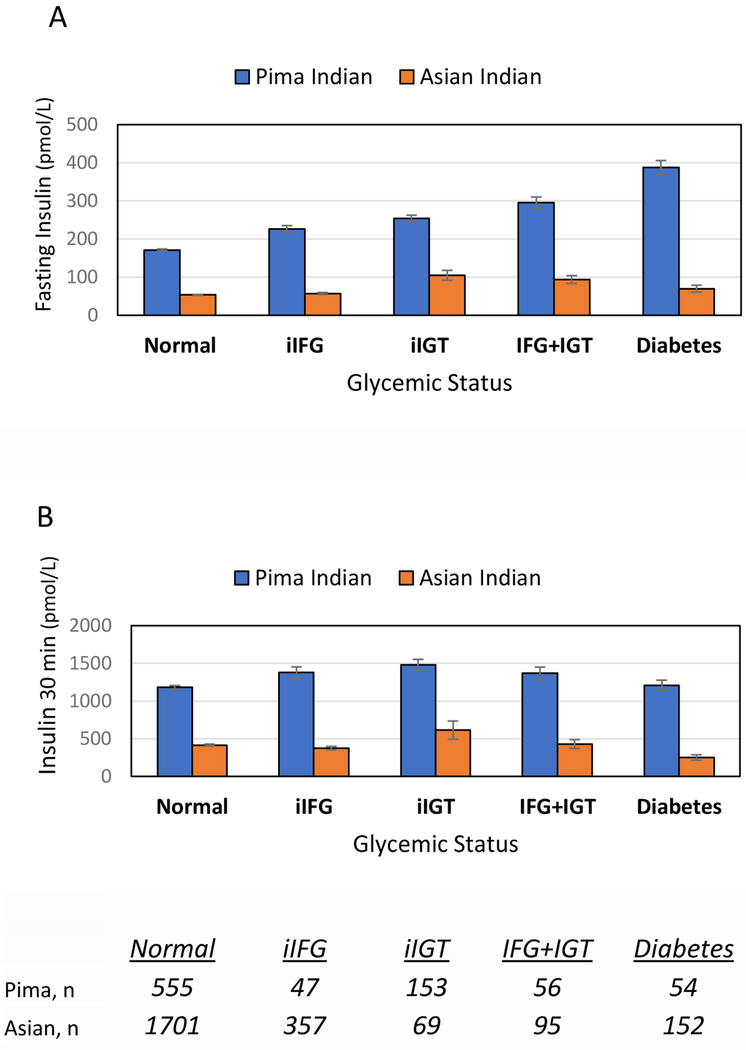

Appendix Table 3 compares metabolic characteristics of Asian Indians to Pima Indians adjusted for age, sex, and BMI across categories of glycemic status. Among those with normoglycemia, Asian Indians had higher FPG levels (Pima: 4.7 vs. Asian: 5.0 mmol/L; or Pima: 84.7 versus Asian: 90.1 mg/dL, p<0.001), whereas Pima Indians had higher 2hPG levels (5.8 mmol/L vs. Asian 5.2 mmol/L, or 104.5 vs. Asian 93.7 mg/dL, p<0.001). Mean fasting and 30 minute insulin were three times lower in normoglycemic Asian Indians compared to normoglycemic Pima Indians. Pima Indians were 3 times more resistant (HOMA-IR 6.0 vs. Asian Indian 2.0, p<0.001), and Asian Indians had 2.5 times less beta-cell function (insulinogenic index Pima: 2.8 versus Asian: 1.1, p<0.001). In Figure 1 mean insulin levels (for Figure 1A -during fasting state and Figure 1B - at 30 minutes of OGTT) were compared across glycemic strata for each ethnicity. Different trends in insulin secretion were observed between the two ethnicities, particularly for milder categories of dysglycemia. Among Pima Indians, mean 30 minute insulin was greater in iIFG (1375.7 pmol/L, SE 76.4.5) compared to normoglycemia (Pima Indians: 1181.9 pmol/L, SE 24.0). Among Asian Indians, however, mean 30-minute insulin in iIFG was lower compared to normoglycemia (iIFG: 375.6 pmol/L SE 22.7 vs. normoglycemia in Asian Indians: 416.2 pmol/L SE 12.2).

Figure 1.

Variation of mean insulin within each ethnicity, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI.

Mean insulin levels (for Figure 1A - fasting state and Figure 1B - 30 minutes of OGTT) are presented across glycemic strata for each ethnicity. Mean insulin values are provided for each category of glycemic status, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI, to allow for within-ethnicity comparisons. Figure 1A provides mean fasting insulin values of the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and Figure 1B provides means of insulin values collected at 30 minutes of the OGTT. n=sample size per category; for conventional units: Insulin 1 uIU/mL = 6.0 pmol/L.

Metabolic characteristics of the youngest age group, stratified by BMI and adjusted for sex, were assessed (Table 2). Among the youngest, normal weight individuals, BMIs were similar between ethnicities, yet FPG was higher in Asian Indians compared to Pima Indians (Pima: 4.6 versus Asian: 5.0 mmol/L, i.e., Pima: 82.9 versus 90.1 mg/dL, p<0.05). Although Pima Indians had higher mean BMIs in the obese strata of young adults compared to Asian Indians, mean FPG remained higher in Asian Indians, reaching 5.7 mmol/L (102.7 mg/dL) in Asians (Pima: 5.2 mmol/L or 93.7 mg/dL, p<0.05). Across higher BMI strata, the insulinogenic index in Pima Indians increased; however, for Asians, the insulinogenic index did not differ among BMI strata. In the obese category of young participants, the mean insulinogenic index was 3.6 pmol/mmol for the Pima Indians compared to 1.0 pmol/mmol in Asian Indians (p<0.05).

Table 2.

Metabolic characteristics among the youngest adults (ages 18-29 years), stratified by BMI and adjusted for sex

| Normal Weight BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 | Overweight BMI 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2 | Obese BMI 30 kg/m2 or more | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pima n=82 | Asian n=297 | Pima n=105 | Asian n=222 | Pima n=380 | Asian n=90 | ||||||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | P | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | P | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | P | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.0 | 0.2 | 22.0 | 0.1 | 0.97 | 27.8 | 0.1 | 27.3 | 0.1 | 0.013 | 37.9 | 0.3 | 33.1 | 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| waist circumference (cm)† | 78.2 | 0.8 | 75.1 | 0.4 | 0.0007 | 92.3 | 0.8 | 85.5 | 0.5 | <0.0001 | 115.6 | 0.6 | 94.3 | 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.6 | 0.1 | 5.0 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 4.8 | 0.1 | 5.2 | 0.1 | <0.0001 | 5.2 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 0.1 | 0.0024 |

| 30 min glucose (mmol/L) | 7.6 | 0.2 | 7.6 | 0.1 | 0.79 | 7.9 | 0.2 | 8.3 | 0.1 | 0.090 | 8.3 | 0.1 | 9.1 | 0.2 | 0.0025 |

| 2 hour glucose (mmol/L) | 5.8 | 0.2 | 5.3 | 0.1 | 0.0051 | 6.4 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 0.0066 | 7.6 | 0.2 | 6.5 | 0.3 | 0.0023 |

| fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 123.9 | 3.4 | 42.8 | 1.8 | <0.0001 | 164.2 | 4.0 | 52.3 | 2.7 | <0.0001 | 295.4 | 6.1 | 47.0 | 13.0 | <0.0001 |

| 30 min insulin (pmol/L) | 953.8 | 35.3 | 348.1 | 18.2 | <0.0001 | 1215.3 | 46.6 | 417.3 | 31.5 | <0.0001 | 1691.3 | 50.1 | 525.1 | 106.3 | <0.0001 |

| 2 hour insulin (pmol/L) | 524.5 | 28.8 | 238.4 | 14.9 | <0.0001 | 822.1 | 42.6 | 317.2 | 28.8 | <0.0001 | 1449.7 | 49.8 | 248.3 | 105.6 | <0.0001 |

| HOMA-IR (uIU*mmol/L2) | 4.2 | 0.1 | 1.6 | 0.1 | <0.0001 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 2.1 | 0.1 | <0.0001 | 11.6 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| Modified Matsuda Index (((L2)/mmolglu x pmolins) | 8.8 | 1.1 | 24.2 | 0.6 | <0.0001 | 7.0 | 0.9 | 19.9 | 0.6 | <0.0001 | 3.8 | 0.2 | 15.9 | 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| Insulinogenic Index (pmol/mmol)‡ | 2.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | <0.0001 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | <0.0001 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | <0.0001 |

missing waist circumference data for 7 Pima Indians and 46 Asian Indians.

geometric least squares means and geometric standard errors provided. For conventional units: Insulin 1 uIU/mL = 6.0 pmol/L.

The above findings were reevaluated with other indices of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, modified Matsuda Index) and insulin secretion (insulinogenic index and area under the curve of insulin relative to glucose for the first 30 minutes of OGTT). All results were consistent, regardless of index used for insulin resistance or insulin secretion (data not shown). For each ethnicity, the relative contributions of insulin secretion and insulin resistance to glycemic outcomes were examined (Appendix Table 4). In Asian Indians, the associations of higher insulinogenic index with prediabetes and diabetes were consistently stronger (i.e., the odds ratios were lower) than in Pima Indians. The associations of higher standardized HOMA-IR within prediabetes and diabetes were greater in Pima Indians compared with Asian Indians, although statistical significance was not reached. These results further support a more prominent role of decreased insulin secretion in the early natural history of diabetes in Asian Indians, even after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI.

DISCUSSION

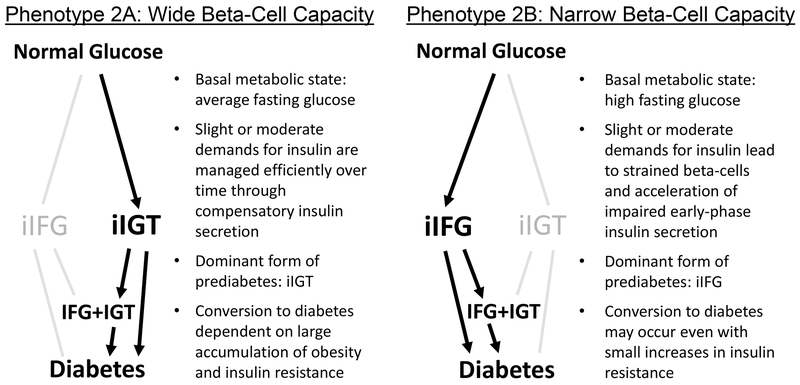

In this study, we compared two ethnicities at high-risk for type 2 diabetes, Pima Indians and Asian Indians, and identified marked metabolic differences that support two distinct pathways in the early natural history of diabetes. Asians Indians predominantly exhibited iIFG for prediabetes type, and Pima Indians predominantly iIGT. Second, Pima Indians were three times more insulin resistant than Asians, whereas Asian Indians secreted nearly 3 times less insulin, findings consistent across age strata. Strikingly, these findings were evident in normal weight individuals and normoglycemic individuals. Previous studies in Pima Indians have shown that both insulin sensitivity and insulin secretory capacity deteriorate as diabetes develops23,24. However, the timing and concentration of these metabolic problems may differ across populations. The totality of these findings support different phenotypes of type 2 diabetes risk, and Figure 2 presents a hypothesis generated from these findings. “Phenotype 2a” is characterized by insulin resistance and elevated metabolic load by weight status, as observed in Pima Indians. “Phenotype 2b” is characterized by impaired insulin secretion and reduced metabolic capacity of the pancreas, as observed in Asian Indians25.

Figure 2.

Hypothesis: Heterogeneous Phenotypes of Type 2 Diabetes Risk.

The hypothesis includes Phenotype 2a, defined largely by insulin resistance and adiposity as observed in Pima Indians, and Phenotype 2b, characterized largely by impaired insulin secretion and reduced functional capacity of the pancreatic beta-cells, as observed in Asian Indians.

Our findings are further supported by other studies that have examined normal weight subjects with unhealthy metabolic characteristics. Stefan and colleagues showed that from a study of nearly 1,000 Caucasian subjects stratified by BMI categories, 18% of the 181 normal weight subjects were metabolically unhealthy, and the most prevalent risk phenotype was insulin secretion failure26. Across normal weight U.S. adults, 21.0% of non-Hispanic whites, 31.1% of African Americans, 38.5% of Hispanics, and 43.6% of South Asians were metabolically unhealthy yet thin9,27–29, and South Asians had poorer pancreatic beta-cell function compared with whites, blacks, and Hispanics9. Similarly, an analysis from the Whitehall II cohort study in the U.K. suggested that South Asians may have a poorer beta-cell reserve relative to white Europeans30. These studies support the hypothesis of Phenotype 2b describing high-risk individuals with narrow beta-cell capacity.

Our findings of low insulin secretion in Asian Indians at fasting and during the first 30 minutes of the OGTT suggest abnormalities specific to early phase insulin release. The two ethnicities had similar partial correlations between fasting glucose and insulin secretion, yet Asian Indians still had lower absolute levels of insulin secretion. IFG may be the manifestation of defects in basal glucose metabolism, insulin secretion and raised hepatic glucose output31. Partial correlations of 2hPG and fasting insulin were different across ethnicities, even after adjusting for insulin secretion, suggesting differences between ethnicities in mechanisms related to IGT and diabetes pathogenesis (e.g., peripheral insulin resistance). Furthermore, our results suggest that population differences insulin secretion may be particularly important for disease risk, and not just differences in insulin resistance. The clinical implications of heterogeneous disease pathways include treatment effectiveness. In the only diabetes prevention trial of Asian Indians that included participants with iIFG, iIGT, or IFG+IGT, the intervention of lifestyle and metformin, designed to improve insulin sensitivity through weight loss, exercise, dietary changes, and pharmacology, was least effective in participants with iIFG compared to those with iIGT or IFG+IGT32. A recent study of European diabetes patients (i.e., late natural history of type 2 diabetes) identified clusters of participants differing in progression to kidney disease and retinopathy4, suggesting that our findings of heterogeneity in the early natural history of type 2 diabetes may have long term consequences.

Several limitations exist in this study. First, this study was cross sectional and cannot be used to infer temporality or causality. Second, different insulin assays were employed for each ethnicity, and observations may be an artefact of differing assay sensitivity. However, in previous studies that have compared insulin levels in Pima Indians to other populations using the same insulin assay, Pima Indians were hyperinsulinemic compared to other ethnicities as observed here33,34, and a U.S. reference laboratory was used for validation of the Asian Indian population. Moreover, we applied two statistical approaches to overcome insulin assay limitations: (1) use of variables standardized within each population and (2) correlation analyses. These approaches enabled examination of differences in the relative ranks within each population. Results consistently showed greater contributions of insulin secretion to dysglycemia in Asian Indians and greater contributions of insulin resistance to glucose tolerance in Pima Indians. This study was limited to single measurements of fasting glucose, 30 minute glucose, and 2-hour glucose from one study visit, all measured by rigorous methods of OGTT. Clamp-derived measures of insulin secretion and insulin resistance are gold-standard measures, however, OGTT-derived measures are valid; highly predictive of type 2 diabetes after 10 years; consistent with biological constructs; simulate true physiologic metabolic responses after glucose ingestion (e.g., incretins); and are preferred by study participants for convenience35.

The strengths of this study include examination of heterogeneity in the early natural history of diabetes using large, population-based samples of high-risk ethnicities not historically compared. By including a large number of normoglycemic and normal weight individuals, we assess the relative contributions of insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion across the natural history of diabetes, including early stages of disease. We use a large cohort of Asian Indian individuals to examine an understudied but highly prevalent diabetes phenotype: poor early-phase insulin secretion and high FPG levels before prediabetes and in the general absence of obesity. Therefore, we link characteristics of disease pathogenesis to a global context of health disparities for Asian Indians9,28. Other strengths of this study include identifying newly diagnosed cases of diabetes using OGTT, the assessment of beta cell function based on a dynamic measure that is highly predictive of diabetes35, and quality assurance of glucose and insulin assays by evaluating laboratory assays against a reputable U.S. reference laboratory.

In conclusion, this study identified pronounced ethnic heterogeneity in the early natural history of diabetes. The physiological basis of distinct phenotypes provides strong rationale to investigate the molecular mechanisms leading to diabetes presentation across diverse and understudied populations. Insights into type 2 diabetes heterogeneity could lead to advances in clinical care and/or precision public health36 for timely risk stratification in the early natural history of diabetes, for improved intervention response by tailoring interventions (e.g., lifestyle or drug dosing), and for greater drug safety37. For normal weight populations with Phenotype 2b, one of the greatest challenges may be out-racing the silent progression of diabetes where the visible, clinical risk factor of obesity is lacking.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The CARRS Study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN268200900026C, and the United Health Group, Minneapolis, MN, USA. LRS was supported by the Molecules to Mankind Program sponsored by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (BWF Award Number 1008188). MD was supported in part by the Fogarty International Center of the NIH under Award Number D43TW009135. MKA was supported by NHLBI Contract No. HHSN268200900026C; the United Health Group, Minneapolis, MN, USA; and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) of the NIH, Award Number P30DK111024. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. RLH was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. KMVN was supported in part by NIDDK Award Number P30DK111024. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Parts of this study were presented at the 74th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Francisco, CA, June 13-17, 2014. The authors thank the contributions of Shreya Kothari who assisted in editing a portion of the manuscript.

Appendix Table 1.

Population partial correlations of fasting glucose or 2 hour glucose and factors related to diabetes pathogenesis

| Fasting Glucose | 2 Hour Glucose | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Estimated Correlation | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P value ((ho: ρ1 = ρ2) | Estimated Correlation | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P value ((ho: ρ1 = ρ2) |

| CIR30 adjusted for age, sex | ||||||||

| Pima | −0.26 | −0.32 | −0.19 | 0.95 | −0.25 | −0.31 | −0.19 | 0.90 |

| Asian | −0.26 | −0.30 | −0.22 | −0.26 | −0.29 | −0.22 | ||

| CIR30 adjusted for age, sex, BMI | ||||||||

| Pima | −0.30 | −0.36 | −0.24 | 0.10 | −0.29 | −0.35 | −0.23 | 0.14 |

| Asian | −0.24 | −0.28 | −0.20 | −0.23 | −0.27 | −0.20 | ||

| CIR30 adjusted for age, sex, BMI, fasting insulin | ||||||||

| Pima | −0.31 | −0.37 | −0.25 | 0.19 | −0.34 | −0.40 | −0.28 | 0.06 |

| Asian | −0.27 | −0.30 | −0.23 | −0.27 | −0.31 | −0.24 | ||

| Fasting insulin adjusted for age, sex | ||||||||

| Pima | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.0001 |

| Asian | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.27 | ||

| Fasting insulin adjusted for age, sex, BMI | ||||||||

| Pima | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.0012 |

| Asian | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.22 | ||

| Fasting Insulin adjusted for age, sex, BMI, CIR30 | ||||||||

| Pima | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.0007 |

| Asian | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.27 | ||

For each ethnicity, stepwise addition of covariates were considered, as shown.

Appendix Table 2.

Metabolic characteristics among BMI strata in two ethnicities, adjusted for age and sex

| Normal Weight BMI 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2 | Overweight BMI 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2 | Obese BMI 30 kg/m2 or more | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pima | Asian | Pima | Asian | Pima | Asian | ||||||||||

| n=120 | n=941 | n=169 | n=870 | n=571 | n=409 | ||||||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | P | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | P | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | P | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.4 | 0.2 | 22.2 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 27.7 | 0.1 | 27.3 | 0.5 | 0.004 | 38.1 | 0.2 | 33.2 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| waist circumference (cm)* | 79.9 | 0.7 | 76.6 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 92.6 | 0.6 | 86.8 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 117.3 | 0.2 | 94.5 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.8 | 0.1 | 5.2 | 0.04 | 0.003 | 5.1 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 0.05 | 0.001 | 5.3 | 0..06 | 5.7 | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| 30 min glucose (mmol/L) | 8.0 | 0.2 | 8.0 | 0.07 | 0.6 | 8.3 | 0.2 | 8.9 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 8.4 | 0.1 | 9.4 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| 2 hour glucose (mmol/L) | 6.2 | 0.2 | 5.6 | 0.8 | 0.001 | 6.9 | 0.3 | 6.3 | 0.1 | <0.001 | 7.8 | 0.1 | 6.8 | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 123.8 | 2.6 | 42.3 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 164.6 | 2.9 | 51.3 | 1.2 | 0.0010 | 290.0 | 4.8 | 52.4 | 5.9 | <0.001 |

| 30 min insulin (pmol/L) | 938.8 | 27.1 | 332.5 | 9.2 | 0.99 | 1176.0 | 29.8 | 375.8 | 12.3 | 0.02 | 1494.9 | 34.9 | 490.2 | 42.6 | <0.001 |

| 2 hour insulin (pmol/L) | 528.3 | 22.6 | 250.4 | 7.7 | 0.02 | 859.0 | 29.0 | 302.2 | 12.0 | 0.03 | 1423.1 | 38.6 | 303.9 | 47.2 | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR (uIU*mmol/L2) | 4.3 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.4 | <0.001 | 6.1 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 0.6 | <0.001 | 11.6 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Modified Matsuda Index ((L2)/mmolglu x pmolins) | 8.9 | 1.0 | 24.2 | 0.3 | <0.001 | 6.5 | 0.7 | 19.4 | 0.3 | <0.001 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 16.1 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| Insulinogenic Index (pmol/mmol)† | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

For conventional units: waist (1inch=2.54 cm), glucose (mg/dL = 0.05551 mmol/L), insulin (uIU/mL = 6.0 pmol/L);

missing waist circumference data for 7 Pima Indians and 46 Asian Indians;

Geometric means and geometric standard errors provided.

Appendix Table 3.

Metabolic characteristics among glycemic status groups, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI

| Normoglycemia | iIFG | iIGT | IFG+IGT | Diabetes | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pima Indian n=555 | Asian Indian n=1701 | Pima Indian n=47 | Asian Indian n=357 | Pima Indian n=153 | Asian Indian n=69 | Pima Indian n=56 | Asian Indian n=95 | Pima Indian n=54 | Asian Indian n=152 | |||||||||||

| LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | LS Mean | SE | |

| fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.7 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 0.01*** | 5.7 | 0.1 | 5.9 | 0.01* | 5.0 | 0.03 | 5.1 | 0.1* | 5.8 | 0.05 | 6.7 | 0.4*** | 6.9 | 5.8 | 9.2 | 0.3** |

| 30 min glucose (mmol/L) | 7.5 | 0.07 | 7.7 | 0.04** | 8.5 | 0.3 | 9.4 | 0.1** | 8.6 | 0.1 | 9.1 | 0.2 | 9.4 | 0.2 | 10.7 | 10.4*** | 10.9 | 0.7 | 15.0 | 0.3*** |

| 2 hour glucose (mmol/L) | 5.8 | 0.1 | 5.2 | 0.03*** | 6.5 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.1** | 8.8 | 0.1 | 8.6 | 0.1 | 9.3 | 0.1 | 8.9 | 0.1** | 14.1 | 0.9 | 15.1 | 0.4 |

| fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 171.5 | 2.6 | 53.3 | 1.3*** | 226.7 | 8.4 | 57.3 | 2.5*** | 254.7 | 8.1 | 104.8 | 13.2*** | 295.6 | 14.7 | 93.8 | 10.5*** | 387.7 | 18.2 | 70.0 | 9.0*** |

| 30 min insulin (pmol/L) | 1181.9 | 24.0 | 416.2 | 12.2*** | 1375.7 | 76.4 | 375.6 | 22.7 *** | 1479.6 | 73.7 | 613.9 | 120.3*** | 1368.3 | 82.5 | 428.2 | 58.6*** | 1205.5 | 71.4 | 250.3 | 35.5*** |

| 2 hour insulin (pmol/L) | 709.3 | 17.8 | 293.2 | 9.0*** | 724.2 | 51.0 | 322.2 | 15.1*** | 1730.1 | 82.1 | 859.6 | 134.2*** | 1819.1 | 126.7 | 808.8 | 90.1*** | 2098.4 | 154.4 | 339.9 | 76.8*** |

| HOMA-IR (uIU*mmol/L2) | 6.0 | 0.09 | 2.0 | 0.5*** | 9.8 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 0.1*** | 9.4 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 0.5*** | 12.7 | 0.7 | 4.4 | 0.5*** | 18.8 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 0.4*** |

| Modified Matsuda Index ((L2)/mmolglu x pmolins) | 9.2 | 0.5 | 23.2 | 0.2*** | 8.6 | 1.3 | 17.1 | 0.4*** | 3.9 | 3.3 | 13.1 | 0.5*** | 3.5 | 0.6 | 11.6 | 0.4*** | 2.4 | 0.7 | 9.5 | 0.3*** |

| Insulinogenic Index (pmol/mmol)* | 2.8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0*** | 3.2 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.0*** | 2.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.1*** | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.1*** | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.1*** |

For conventional units: glucose (mg/dL = 0.05551 mmol/L), insulin (uIU/mL = 6.0 pmol/L). For comparisons between Pima Indians and Asian Indians within each glycemic category:

p< 0.05;

p< 0.01; and

p<0.001. Geometric least square (LS) means and geometric standard errors provided.

Appendix Table 4.

Contributions of insulin secretion and insulin resistance to glycemic status across populations

| Normoglycemia | Prediabetes | Diabetes | Summary | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Variable | OR Pima* | OR Asian* | OR Pima Indian | OR Asian Indian | P-val | OR Pima Indian | OR Asian Indian | P-val | P-val |

| 1 | Insulinogenic Index | 1 | 1 | 0.59 (0.49, 0.72) | 0.47 (0.41, 0.54) | 0.0532 | 0.20 (0.13, 0.29) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.11) | 0.0002 | <0.0001 |

| 1 | HOMA-IR | 1 | 1 | 4.19 (3.26, 5.40) | 3.16 (2.73, 3.66) | 0.0569 | 11.81 (8.01, 17.42) | 9.98 (7.67, 12.98) | 0.7034 | 0.0652 |

| 2 | Insulinogenic Index | 1 | 1 | 0.64 (0.53, 0.79) | 0.47 (0.42, 0.54) | 0.0059 | 0.20 (0.14, 0.30) | 0.07 (0.05, 0.11) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | HOMA-IR | 1 | 1 | 3.98 (3.08, 5.14) | 3.15 (2.71, 3.65) | 0.1230 | 10.99 (7.43, 16.27) | 10.64 (8.08, 14.0) | 0.8945 | 0.2343 |

| 3 | Insulinogenic Index | 1 | 1 | 0.64 (0.52, 0.78) | 0.49 (0.43, 0.56) | 0.0328 | 0.21 (0.14, 0.31) | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11) | 0.0023 | 0.0002 |

| 3 | HOMA-IR | 1 | 1 | 3.76 (2.80, 5.05) | 2.77 (2.38, 3.23) | 0.0709 | 11.40 (7.23, 17.97) | 9.22 (6.97, 12.2) | 0.7784 | 0.0676 |

Odds ratios (OR) are expressed per 1 SD unit for each variable standardized within population for each outcome relative to normoglycemia (for which the ORs=1 by definition). P-values are for the null hypothesis that the odds ratios for Pima Indians and Asian Indians are the same; the summary p-value is combined over both prediabetes and diabetes. Model 1 contains the independent variables of insulinogenic index and HOMA-IR; Model 2 further adjusts for age and sex; and Model 3 further adjusts for BMI.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. Brussels, Belgium: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuomi T, Santoro N, Caprio S, Cai M, Weng J, Groop L. The many faces of diabetes: a disease with increasing heterogeneity. Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1084–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udler MS, Kim J, von Grotthuss M, et al. Type 2 diabetes genetic loci informed by multi-trait associations point to disease mechanisms and subtypes: A soft clustering analysis. PLoS Med. 2018;15(9):e1002654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahlqvist E, Storm P, Karajamaki A, et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: a data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(5):361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou X, Zhou X, Zhu Z, Ji L. Novel subgroups of patients with adult-onset diabetes in Chinese and US populations. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(1):9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett PH, Burch TA, Miller M. Diabetes mellitus in American (Pima) Indians. Lancet. 1971;2(7716):125–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowler WC, Bennett PH, Hamman RF, Miller M. Diabetes incidence and prevalence in Pima Indians: a 19-fold greater incidence than in Rochester, Minnesota. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108(6):497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz LO, Bennett PH, Ravussin E, et al. Effects of traditional and western environments on prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians in Mexico and the U.S. Diabetes care. 2006;29(8):1866–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gujral UP, Vittinghoff E, Mongraw-Chaffin M, et al. Cardiometabolic Abnormalities Among Normal-Weight Persons From Five Racial/Ethnic Groups in the United StatesA Cross-sectional Analysis of Two Cohort StudiesCardiometabolic Abnormalities Among Normal-Weight Persons. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan JC, Malik V, Jia W, et al. Diabetes in Asia: epidemiology, risk factors, and pathophysiology. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(20):2129–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lillioja S, Mott DM, Zawadzki JK, et al. In vivo insulin action is familial characteristic in nondiabetic Pima Indians. Diabetes. 1987;36(11):1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Savage PJ, Bennett PH. Diabetes incidence in Pima indians: contributions of obesity and parental diabetes. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113(2):144–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair M, Ali MK, Ajay VS, et al. CARRS Surveillance study: design and methods to assess burdens from multiple perspectives. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali MK, Bhaskarapillai B, Shivashankar R, et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk in urban South Asia: The CARRS Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbert V, Lau KS, Gottlieb CW, Bleicher SJ. Coated charcoal immunoassay of insulin. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1965;25(10):1375–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2019. Diabetes care. 2019;42 Suppl 1:S13–28.30559228 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeFronzo RA, Matsuda M. Reduced time points to calculate the composite index. Diabetes care. 2010;33(7):e93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. Brussels, Belgium: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sluiter WJ, Erkelens DW, Reitsma WD, Doorenbos H. Glucose tolerance and insulin release, a mathematical approach I. Assay of the beta-cell response after oral glucose loading. Diabetes. 1976;25(4):241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitlock MC. Combining probability from independent tests: the weighted Z-method is superior to Fisher’s approach. J Evol Biol. 2005;18(5):1368–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lillioja S, Mott DM, Spraul M, et al. Insulin resistance and insulin secretory dysfunction as precursors of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Prospective studies of Pima Indians. The New England journal of medicine. 1993;329(27):1988–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weyer C, Bogardus C, Pratley RE. Metabolic characteristics of individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 1999;48(11):2197–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Narayan KM. Type 2 Diabetes: Why We Are Winning the Battle but Losing the War? 2015 Kelly West Award Lecture. Diabetes care. 2016;39(5):653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stefan N, Schick F, Haring HU. Causes, Characteristics, and Consequences of Metabolically Unhealthy Normal Weight in Humans. Cell Metab. 2017;26(2):292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hulman A, Gujral UP, Narayan KMV, et al. Glucose patterns during the OGTT and risk of future diabetes in an urban Indian population: The CARRS study. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2017;126:192–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanaya AM, Herrington D, Vittinghoff E, et al. Understanding the high prevalence of diabetes in U.S. south Asians compared with four racial/ethnic groups: the MASALA and MESA studies. Diabetes care. 2014;37(6):1621–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gujral UP, Mohan V, Pradeepa R, Deepa M, Anjana RM, Narayan KM. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of diabetes in underweight and normal weight individuals: The CARRS and NHANES studies. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2018;146:34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikehara S, Tabak AG, Akbaraly TN, et al. Age trajectories of glycaemic traits in non-diabetic South Asian and white individuals: the Whitehall II cohort study. Diabetologia. 2015;58(3):534–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer C, Pimenta W, Woerle HJ, et al. Different mechanisms for impaired fasting glucose and impaired postprandial glucose tolerance in humans. Diabetes care. 2006;29(8):1909–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber MB; Ranjani H; Staimez LR; Anjana M; Ali MK; Narayan KMV; Mohan V. The stepwise approach to diabetes prevention: results from the D-CLIP randomized controlled trial. Diabetes care. 2016;39(10):1760–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pettitt DJ, Moll PP, Knowler WC, et al. Insulinemia in children at low and high risk of NIDDM. Diabetes care. 1993;16(4):608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lillioja S, Nyomba BL, Saad MF, et al. Exaggerated early insulin release and insulin resistance in a diabetes-prone population: a metabolic comparison of Pima Indians and Caucasians. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1991;73(4):866–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Utzschneider KM, Prigeon RL, Faulenbach MV, et al. Oral disposition index predicts the development of future diabetes above and beyond fasting and 2-h glucose levels. Diabetes care. 2009;32(2):335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khoury MJ, Iademarco MF, Riley WT. Precision Public Health for the Era of Precision Medicine. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(3):398–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langenberg C, Lotta LA. Genomic insights into the causes of type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2018;391(10138):2463–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]