Abstract

Vitamin D plays an essential role in regulating calcium and phosphate metabolism and maintaining a healthy mineralized skeleton. Humans obtain vitamin D from sunlight exposure, dietary foods and supplements. There are two forms of vitamin D: vitamin D3 and vitamin D2. Vitamin D3 is synthesized endogenously in the skin and found naturally in oily fish and cod liver oil. Vitamin D2 is synthesized from ergosterol and found in yeast and mushrooms. Once vitamin D enters the circulation it is converted by 25-hydroxylase in the liver to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], which is further converted by the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase in the kidneys to the active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D]. 1,25(OH)2D binds to its nuclear vitamin D receptor to exert its physiologic functions. These functions include: promotion of intestinal calcium and phosphate absorption, renal tubular calcium reabsorption, and calcium mobilization from bone. The Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice Guideline defines vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency as serum concentrations of 25(OH)D of <20 ng/mL, 21–29 ng/mL, and 30–100 ng/mL, respectively. Vitamin D deficiency is a major global public health problem in all age groups. It is estimated that 1 billion people worldwide have vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency. This pandemic of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is attributed to a modern lifestyle and environmental factors that restrict sunlight exposure, which is essential for endogenous synthesis of vitamin D in the skin. Vitamin D deficiency is the most common cause of rickets and osteomalacia, and can exacerbate osteoporosis. It is also associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain, muscle weakness, and an increased risk of falling. In addition, several observational studies observed the association between robust levels of serum 25(OH)D in the range of 40–60 ng/mL with decreased mortality and risk of development of several types of chronic diseases. Therefore, vitamin D-deficient patients should be treated with vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 supplementation to achieve an optimal level of serum 25(OH)D. Screening of vitamin D deficiency by measuring serum 25(OH)D is recommended in individuals at risk such as patients with diseases affecting vitamin D metabolism and absorption, osteoporosis, and older adults with a history of falls or nontraumatic fracture. It is important to know if a laboratory assay measures total 25(OH)D or only 25(OH)D3. Using assays that measure only 25(OH)D3 could underestimate total levels of 25(OH)D and may mislead physicians who treat patients with vitamin D2 supplementation.

Keywords: Vitamin D

1. Historical overview of vitamin D

In the 1600s when the industrial revolution swept across Europe, there was an outbreak of a disease causing skeletal deformities in children known as rickets in the Southwest counties of England.1,2 The etiology of rickets remained a mystery for more than 250 years. By the early 1900s upwards of 90% of children living in Leiden, Glasgow, London and Berlin were reported to have skeletal manifestations of rickets.3 Huldschinski exposed rachitic children to a mercury arc lamp and reported marked radiologic improvement of the rachitic children (Fig. 1.). He correctly speculated that something that was synthesized by the skin had systemically improved bone health4 In 1921, Hess and Unger finally demonstrated radiologic improvement of rachitic children after exposing them to sunlight at the roof of their hospital in New York.5 In 1919, Edward Mellanby and Elmer McCollum performed animal studies that proved the antirachitic properties in cod liver oil.6,7 Later, McCollum named the antirachitic factor in cod liver oil as “vitamin D″ because it was the fourth vitamin that had been discovered following vitamin A, B and C.8

Fig. 1.

UV radiation therapy for rickets. (A) Photograph from the 1920s of a child with rickets being exposed to artificial UV radiation. (B) Radiographs demonstrating florid rickets of the hand and wrist (left). The same hand and wrist taken after a course of treatment with 1-h UV radiation 2 times/week for 8 week showing mineralization of the carpal bones and epiphyseal plates (right). Holick, copyright 2006. Reproduced with permission.

In 1924, Hess and Weinstock, and Steenbock and Black discovered that UVB irradiation of ergosterol in yeast and vegetable foods as well as cholesterol (later found to have a small amount of 7-dehydrocholesterol) in the skin resulted in the production of the antirachitic factor vitamin D.9,10 This led Steenbock et al. to introduce the concept of irradiating ergosterol containing milk or adding irradiated ergosterol to milk as a means of providing vitamin D to children.3 This fortification process was practiced in most industrialized countries and thus rickets was essentially eradicated by the early 1930s.5 However, in the early 1950s, several young children in England were reported to have altered facial features, supravalvular aortic stenosis, mild mental retardation and hypercalcemia. It was incorrectly concluded by the experts that this was due to in utero or infantile vitamin D intoxication most likely due to the over fortification of milk with vitamin D. Although there was no proof for this, the fact that infants had similar birth defects was alarming, and as a result, Great Britain immediately banned vitamin D fortification of milk and any other product used by children or adults. This hysteria quickly spread worldwide where only the United States and Canada continued fortifying milk with vitamin D. In retrospect, it is likely that these children had Williams syndrome which causes elfin-like faces, supravalvular aortic stenosis, mild mental retardation and a hypersensitivity to vitamin D that results in hypercalcemia.11 Only a few countries including Sweden, Finland and most recently India have now reinstituted a program to improve vitamin D status of the population by encouraging milk and some other foods and cooking oil to be fortified with vitamin D.12

2. Sources, synthesis, and metabolism of vitamin D

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone responsible for regulating calcium and phosphorus metabolism. Humans obtain vitamin D from either sunlight exposure or dietary foods and supplements. There are two forms of vitamin D: vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) and vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol). Vitamin D3 is synthesized endogenously in the skin and found naturally in oily fish and cod liver oil. Vitamin D2 is synthesized from ergosterol and found in yeast and mushrooms.

Cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3 requires the exposure of UVB at wavelength of 290–315 nm. Once formed, vitamin D3 exits the cutaneous tissue and enters the circulation. Humans also absorb vitamin D as a fat-soluble vitamin from the diet and supplements primarily in the duodenum. The estimated content of vitamin D found in natural products and supplements is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Estimated content of vitamin D2, vitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in diet and pharmaceutical sources.

| Source | Vitamin D content |

|---|---|

| Natural sources | |

| Fresh wild salmon (3.5 oz) | 600–1000 IU of D3 |

| Fresh farmed salmon (3.5 oz) | 100–250 IU of D2 or D3 |

| Canned salmon (3.5 oz) | 300–600 IU of D3 |

| Canned sardine (3.5 oz) | 300 IU of D3 |

| Canned mackerel (3.5 oz) | 250 IU of D3 |

| Canned tuna (3.6 oz) | 230 IU of D3 |

| Cod liver oil (1tsp) | 400–1000 IU of D3 |

| Fresh shiitake mushrooms (3.5 oz) | 600–1000 IU of D2 |

| Sun-dried shiitake mushrooms (3.5 oz) | 600–1000 IU of D2 |

| Beef liver (1 lb) | 0–2500 IU of D3 0.3–3.5 μg of 25-OHD |

| Beef kidney (1 lb) | 20–500 IU of D3 0.4–10.6 μg of 25-OHD |

| Beef muscle (1 lb) | 0–180 IU of D3 0.1–2.6 μg of 25-OHD |

| Pork liver (1 lb) | 70–220 IU of D3 ∼2 μg of 25-OHD |

| Pork muscle (1 lb) | 10–250 IU of D3 0–31.4 μg of 25-OHD |

| Egg yolk | 20 IU of D2 or D3 0.2–0.8 μg of 25-OHD |

| Fortified foods | |

| Fortified milk and infant formula (US) Fortified milk product (India) Fortified cooking oil (India) |

100 IU/8 oz, usually D3 550 IU/L, D2 4.4–6.4 IU/g, D2 |

| Fortified orange juice | 100 IU/8 oz of D3 |

| Fortified yogurts, butter, margarine, cheese | 100 IU/8 oz, usually D3 |

| Fortified breakfast cereals | 100 IU/8 oz, usually D3 |

| Supplements | |

| Prescription | |

| Ergocalciferol (D2) | 20,000, 50,000 IU |

| Drisdol (D2) liquid supplement | 8000 IU/mL |

| Over the counter | |

| Multivitamin | 100, 200, 400 IU of D2 or D3 |

| Vitamin D3 | 400, 800, 1,000, 2,000, 4,000, 5,000, 10,000, 50,000 IU |

Adapted from Holick MF. Vitamin D Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007; 357(19):1980-2., Schmid A, Walther B. Natural vitamin D content in animal products. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2013; 4(4):453-62., and Marwaha RK, Dabas A. Interventions for Prevention and Control of Epidemic of Vitamin D Deficiency. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2019;86(6):532-7.

Once vitamin D enters the circulation, it is weakly bound to the vitamin D binding protein for transport and is stored in adipose tissue. It is metabolized by 25-hydroxylase (CYP2R1) in the liver to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], which is then converted by the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) in the kidneys to the active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D]. 1,25(OH)2D binds to intracellular nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR) to exert its physiologic functions and to regulate its own level via negative feedback mechanism and induction of its own destruction by the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1). 1,25(OH)2D inhibits renal 1α-hydroxylase directly and indirectly by suppressing the expression and production of parathyroid hormone (PTH). The CYP24A1 not only catabolizes 1,25(OH)2D but also 25(OH)D into inactive water-soluble metabolite excreted in the bile.3 Schematic representation of the synthesis and metabolism of vitamin D for skeletal and non-skeletal function is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the synthesis and metabolism of vitamin D for skeletal and nonskeletal function. 1-OHase = 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase; 24-OHase = 25-hydroxyvitamin D-24-hydroxylase; 25(OH)D = 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 1,25(OH)2D = 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; CaBP = calcium-binding protein; CYP27B1, Cytochrome P450–27B1; DBP = vitamin D–binding protein; ECaC = epithelial calcium channel; FGF-23 = fibroblast growth factor-23; PTH = parathyroid hormone; RANK = receptor activator of the NF-kB; RANKL = receptor activator of the NF-kB ligand; RXR = retinoic acid receptor; TLR2/1 = Toll-like receptor 2/1; VDR = vitamin D receptor; vitamin D = vitamin D2 or vitamin D3. Copyright Holick 2013, reproduced with permission.

3. Effect of vitamin D on calcium, phosphate, and bone metabolism

Vitamin D displays its calcemic and phosphatemic make effects by altering the expressions of several genes in the small intestine, kidneys and bone. Activation of VDR by 1,25(OH)2D promotes intestinal calcium and phosphate absorption, renal tubular calcium reabsorption, and calcium mobilization from the bone (Fig. 2.). It should be noted that 1,25(OH)2D promotes bone mineralization mainly by enhancing intestinal calcium and phosphate absorption to maintain an adequate calcium-phosphate product that crystallizes in the collagen matrix resulting in passive bone mineralization. 1,25(OH)2D promotes the expression of osteocalcin which is the major non-collagenous protein in the skeleton. Both 1,25(OH)2D and PTH also enhances bone resorption by stimulating the osteoblast to express receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β (RANK) ligand (RANKL) on cell membrane as well as releasing it into the circulation. RANKL interacts with RANK on the monocytic osteoclast precursor cell causing it to amalgamate with other monocytic cells that results in the formation of a mature osteoclast. Osteoclasts function by bathing bone with hydrochloric acid to aid in the release of calcium into the circulation and collagenases to remove the collagen matrix (Fig. 3, Fig. 4.). In addition, 1,25(OH)2D directly inhibits PTH production and induces FGF23 production in osteocytes as a part of negative feedback loops to maintain serum calcium and phosphate concentration in a physiologic range.13 Overall, vitamin D forms an endocrine system together with PTH and FGF23 to play a crucial role in maintaining calcium and phosphate homeostasis as well as normal bone growth and mineralization.

Fig. 3.

In vitamin D-deficient bone, increased parathyroid hormone induces the osteoblast to express receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANKL) on their cell surface and to secrete soluble RANKL into the extracellular matrix. Both surface RANKL and soluble RANKL interact with receptor activator of NF-kB on the surface of osteoclast precursor cells which are differentiated from macrophage-colony forming unit (M-CFU). RANK-RANKL interaction leads to the differentiation of osteoclast precursor cells into multinucleated osteoclasts which are then activated to exert its bone resorbing activity.

Fig. 4.

Activation of receptor activator NF-kB (RANK) by receptor activator NF-kB ligand (RANKL) leads to osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast activation. It promotes bone resorbing activity of the osteoclast in the lacuna by inducing its secretion of acids including citric acid, lactic acid, hydrochloric acid, and enzymes including cathepsins and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP), leading to a release in collagen fragment, calcium and phosphate from the bone into the extracellular matrix.

4. Non-calcemic effects of vitamin D

Vitamin D has a multitude of non-calcemic actions. This is due in part to the presence of the VDR in most tissues and cells including the skin, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, endocrine pancreas, immune cells, blood vessels, brain, breast, many cancer cells and placenta.14 There is evidence that activation of the VDR by 1,25(OH)2D results in a multitude of biologic activations in these tissues through both genomic and non-genomic pathways. For example, 1,25(OH)2D has been shown to have prodifferentiation and antiproliferation effects on the keratinocyte, antitumergenic and antimetastatic activities on several types of cancer cells, immunomodulatory effects on macrophages and on activated T and B lymphocytes, effects on skeletal muscle function, and protective effects against cardio-metabolic disorders and pregnancy related complications.15

5. Defining vitamin D deficiency and vitamin D insufficiency

The Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice Guideline defines vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency as serum concentrations of 25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL (<50 nmol/L), 21–29 ng/mL (51–74 nmol/L) and 30–100 ng/mL (75–250 nmol/L), respectively.16 They also noted that toxicity is usually not observed until 25(OH)D > 150 ng/mL (>375 nmol/L). Although the cutoff values for the optimal level of 25(OH)D remains controversial, using these values is considered clinically reasonable according to the results from a number of studies. Firstly, an experimental study in adults receiving 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 once a week and calcium supplementation for 8 weeks displayed a significant 35% decrease in their PTH levels when their baseline 25(OH)D was less than 20 ng/mL.17 Secondly, giving vitamin D supplement to postmenopausal women with average serum 25(OH)D of 20 ng/mL to increase their 25(OH)D levels to 32 ng/mL caused a significant increase in efficiency of intestinal calcium absorption by 45–65%.18 Thirdly, several observational studies demonstrated that PTH levels are inversely associated with 25(OH)D levels and plateau in individuals with serum 25(OH)D levels of at least 30–40 ng/mL.19,20 This evidence also concurs with the threshold for prevention of hip and nonvertebral fracture from a meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials with oral vitamin D supplement.21 The normalization of PTH and the changes in important clinical outcomes from improving vitamin D status to certain levels of 25(OH)D suggests that these cutoff values can be used for guidance of treatment decisions. It should be noted that measuring 1,25(OH)2D is not useful for diagnosis and monitoring of vitamin D status, because it is usually normal or elevated due to secondary hyperparathyroidism in the presence of vitamin D deficiency. 1,25(OH)2D measurement should only be considered in patients who have dysregulated vitamin D metabolism such as chronic kidney disease, granulomatous diseases, vitamin D-resistant rickets, and phosphate-losing disorders.16

6. Epidemiology of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency

Vitamin D deficiency is a major global public health problem in all age groups. It is estimated that 1 billion people worldwide have vitamin D deficiency (25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL) or insufficiency (25(OH)D 20–29 ng/mL).22 People living in countries with high latitude were thought to be more susceptible to vitamin D deficiency especially in the wintertime because of the oblique zenith angle of the sun and wearing more clothing.23 Several studies in North America and Europe showed that 40–100% of elderly community-living people are vitamin D deficient.17,19,24,25 Even in healthy young adult students, physicians and residents at a Boston Hospital who were drinking a glass of milk and taking multivitamin daily, the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency at the end of the winter was as high as 32%.26 It is a myth that populations living near the equator where there is robust sunlight are immune to vitamin D deficiency. More than 50% and up to 80% of children and adults in the Middle East, India, Brazil, and South East Asia have been reported to be vitamin D deficient or insufficient.27, 28, 29, 30, 31 The high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in these populations could be attributed to several factors, including extensive skin coverage especially in Middle Eastern women, increased skin melanin content in Africans living in urban areas, lack of vitamin D supplementation and dietary fortification, and inadequate sunlight exposure. Pregnant women and infants are also at high risk for vitamin D deficiency as 73% of the women and 80% of their infants were found to have vitamin D deficient at the time of birth despite taking a daily prenatal multivitamin containing 400 IU of vitamin D.32

7. Factors influencing vitamin D status

Vitamin D status is influenced by several factors, including those affecting skin synthesis, bioavailability and metabolism of vitamin D, and acquired and inherited disorders of vitamin D metabolism and responsiveness. Factors influencing vitamin D status and their mechanisms are summarized in Table 2.22

Table 2.

Factors influencing vitamin D status.

| Factor | Effects |

|---|---|

| Skin synthesis | |

|

|

| |

| Bioavailability | |

|

|

| 25-hydroxylation | |

|

|

| Vitamin D binding protein | |

|

|

| Catabolism | |

|

|

| 1α-hydroxylation | |

| • Acquired disorders | |

|

|

| • Inherited disorders | |

|

|

| Vitamin D responsiveness | |

|

|

Adapted from Holick MF. Vitamin D Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007; 357(19):1980-2.

8. Vitamin D and clinical outcomes

8.1. Rickets and osteomalacia

Rickets is the clinical consequence of defective mineralization throughout the growing skeleton, while osteomalacia is the result of impaired skeletal mineralization occurring after the fusion of epiphyseal plates in adults.3,33 Vitamin D deficiency is the most common cause of rickets and osteomalacia. The second most common cause is inadequate dietary calcium intake of less than 400–500 mg/day.34 In vitamin D-deficient patients, only 10–15% of dietary calcium and 50–60% of dietary phosphorus can be absorbed in small intestine.3 The poor absorption of calcium results in decreased ionized calcium which causes secondary hyperparathyroidism as a compensatory mechanism. PTH maintains calcium by increasing tubular reabsorption of calcium in the kidney and enhancing bone resorption to mobilize calcium stores from the skeleton. Furthermore, PTH also decreases renal phosphate reabsorption leading to urinary loss of phosphate.35 Thus, patients with rickets and osteomalacia usually have 25(OH)D levels of less than 15 ng/mL, elevated serum alkaline phosphatase, normal serum calcium, and low normal to low serum phosphate. Inadequate calcium-phosphate product results in generalized defective osteoid mineralization which then leads to the development of rickets and osteomalacia (Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7.).3,36

Fig. 5.

When serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) is less than 30 ng/mL, there is a significant decrease in intestinal calcium and phosphate absorption. This causes a decrease in serum ionized calcium concentration and subsequent secondary hyperparathyroidism. Elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) induces differentiation of preosteoclast into mature osteoclast leading to increased osteoclast activity. This results in increased bone resorption, loss of bone mineral and matrix, and subsequent low bone mass and osteoporosis. In addition, PTH displays a phosphaturic effect leading to an increase in urinary phosphate excretion. Urinary phosphate loss and decreased intestinal phosphate absorption due to vitamin D deficiency [25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL] contribute to inadequate calcium-phosphate product, thereby resulting in defective bone mineralization and development of rickets and osteomalacia.

Fig. 6.

Normal bone histology with normal trabeculae and normal bone mass is demonstrated in the left picture. Histology of bone with low bone mass/osteoporosis demonstrating thin trabeculae, poor connectivity and low bone mass is shown in the middle picture. Histology of bone with rickets/osteomalacia demonstrating accumulated osteoid (red areas around black mineralized trabeculae) is shown in the right picture.

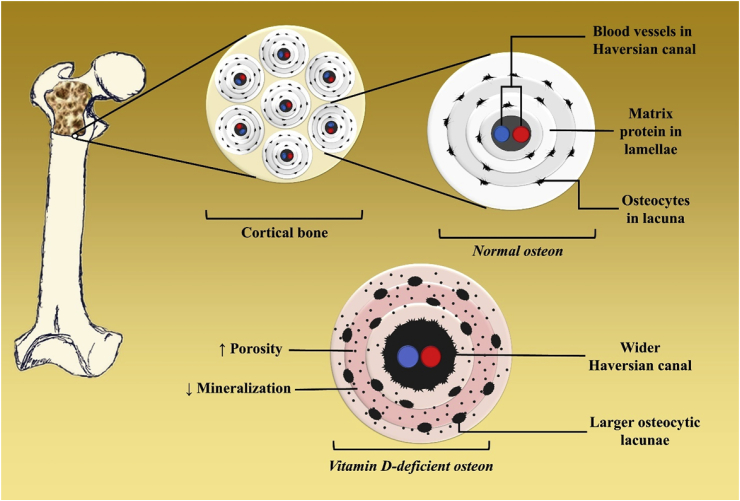

Fig. 7.

Bone consists of two major components, including cortical bone which is a major determinant of bone strength and resistance to fracture, and trabecular bone which acts as bridges built inside the cortical bone that intensifies bone strength. Cortical bone is a built of cylinders called osteons. Each osteon is composed of bone collagen matrix protein arranged concentrically in lamellae around a Haversian canal containing venous (blue) and arterial (red) blood vessels. Osteocytes and osteoclasts are located in lacunae between each lamellae. Vitamin D-deficient osteons displayed larger lacunae, wider Haversian canal due to the PTH induced increase in numbers and activity of osteoclasts thereby increasing the porosity. In addition, there is defect in osteoid mineralization (light pink area) compared with those of normal bone.

Clinical manifestations of rickets and osteomalacia are listed in Table 3. Defective enchondral bone formation in rickets typically appears before the age of 18 months with maximum frequency between the ages of 4 and 12 months because it predominantly affects areas of rapid bone growth including costochondral junctions and long bone epiphyses (Fig. 8.). Vitamin D deficiency prevents normal chondrocyte maturation resulting in hypertrophy of the cells causing widening of the growth plates. Hypertrophy of the costochondral junctions can cause beading known as the classic rachitic rosary, and can progress to protrusion of the sternum, involution of the ribs and costochondral junction, and traverse depressions at the lower end of the rib cage. Flattened pelvic bones and skull deformities including very thin parchment like consistency (craniotabes) and frontal bossing can also be observed in some rachitic children. In severe cases, hypocalcemia can develop, leading to tetany, seizures, laryngospasm, cardiomyopathy and death.3,37 Moreover, profuse sweating is another common finding in infantile rickets and is thought to be caused by bone pain and neuromuscular irritability of the sweat glands.38

Table 3.

Clinical manifestations of rickets and osteomalacia.

| Rickets | Osteomalacia |

|---|---|

|

|

Adapted from Holick MF, Lim R, Dighe AS. Case 3–2009. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009; 360(4):398–407.

Fig. 8.

Skeletal deformities observed in rickets. (A) Photograph from the 1930s of a sister (left) and brother (right), aged 10 months and 2.5 years, respectively, showing enlargement of the ends of the bones at the wrist, carpopedal spasm, and a typical “Taylorwise” posture of rickets. (B) The same brother and sister 4 years later, with classic knock-knees and bow legs, growth retardation, and other skeletal deformities. Holick, copyright 2006. Reproduced with permission.

The histologic manifestation of osteomalacia is an excessive accumulation of poorly mineralized osteoid matrix (Fig. 6.). Osteoblast function is relatively normal in vitamin D deficient children and adults and therefore they produce the collagen matrix. However, because of the inadequate calcium phosphate product in the extracellular space the skeletal collagen matrix cannot be mineralized. The collagen matrix becomes gelatin-like and when it is exposed to water it expands. This matrix expansion underneath the periosteum, which is heavily innervated with sensory fibers, leads to common patient complaints of throbbing and aching bone pain. Tenderness on sternal compression on physical examination helps support the diagnosis.39 In addition, patients typically complain of proximal muscle weakness causing difficulty with transitioning from a sitting to a standing position; and in some cases, patients are unable to lift their head due to severe proximal muscle weakness in the shoulder girdle muscles. In addition to proximal muscle weakness, patients often complain of generalized fatigue and are often misdiagnosed as other rheumatologic diseases such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and polymyalgia rheumatica.40 Patients can also display a characteristic waddling gait which may result from thigh weakness and hip pain.3

8.2. Osteoporosis and fracture

Osteoporosis, the most common metabolic bone disorder worldwide, is the major cause of pathologic fracture in the elderly.41 About one third of women aged between 60 and 70 years old and two third of women over the age of 80 are found to have osteoporosis. It is estimated that 22% of men and 47% of women older than 50 years old will sustain an osteoporotic fracture throughout their remaining lifetime.42,43

Long-standing vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency is a risk factor of osteoporosis. When serum 25(OH)D level is less than 30 ng/mL, there is a decrease in intestinal calcium absorption, leading to a decrease in serum ionized calcium and secondary hyperparathyroidism as a compensatory mechanism. Elevated serum parathyroid hormone induces osteoclast differentiation and activation resulting in an increase in bone resorbing activity by removing both osteoid and mineral bone matrix (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5.). Histologic manifestation and microstructural abnormalities of vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency causing low bone mass/osteoporosis are demonstrated in Fig. 6 and 7., respectively.

There is promising epidemiological evidence showing the positive association between higher serum 25(OH)D levels and greater bone mineral density (BMD) which plateau at a serum 25(OH)D level of 30 ng/mL in both young and old individuals.44 The association is more pronounced in ethnic groups with higher risk of osteoporosis such as Caucasians and Asians, while it is not as robust in Hispanics and blacks that carry the lower risk of osteoporosis.45,46 Nonetheless, whether vitamin D and calcium supplementation can increase or maintain BMD or is beneficial for prevention of osteoporotic fracture is still debatable as placebo-controlled interventional trials examining the effect of vitamin D supplement on the incidence of osteoporotic fracture have displayed largely inconsistent results. For instance, Macdonald et al. reported that giving 1000 IU of vitamin D3 for 1 year could attenuate the decline in BMD at the total hip site when compared to placebo or giving 400 IU of vitamin D3.47 Another study in 3270 elderly French women by Chapuy et al. gave 800 IU of vitamin D3 and 1200 mg of calcium daily for 3 years and observed that the reduction of the risk of nonvertebral fracture by 32% and the risk of hip fracture by 43% compared to the placebo group.48 A study by Dawson-Hughes et al. observed a 58% reduction in nonvertebral fractures in 389 community-dwelling elderly individuals 65 years and older who were receiving 700 IU/day of vitamin D3 along with 500 mg of calcium.49 On the other hand, several large clinical trials and meta-analysis including the vitamin D Individual Patient Analysis of Randomized Trials50, Cochrane review51, and IOM review52 have shown little or no benefits of vitamin D supplement in prevention of fractures. This might be attributed to the heterogeneity of the included subjects such as ethnicity, age, baseline and change in serum 25(OH)D, and baseline vitamin D and calcium intake. It is worth noting that prevention of both nonvertebral and hip fracture was observed in trials giving at least 700 IU of vitamin D3 per day in patients whose baseline serum 25(OH)D level was less than 17 ng/mL and whose mean serum 25(OH)D level rose to around 40 ng/mL.53 This suggests that the antifracture effect of vitamin D supplementation is observed only when vitamin D deficiency is corrected with adequately high dosage of vitamin D to achieve the optimal level of serum 25(OH)D.

8.3. Muscle strength and fall

Skeletal muscle expresses vitamin D receptor and may require vitamin D for maximizing its function.54 Vitamin D deficiency impairs proximal muscle function, and is thought to predispose falls in the elderly. It has been shown that proximal muscle strength and performance speed improved when 25(OH)D rose from 4 to 16 ng/mL and continued to improve as the levels increased to more than 40 ng/mL.53 A randomized clinical trial conducted in nursing home residents demonstrated that giving 800 IU/day of vitamin D2 supplement plus calcium lead to a 72% reduction in risk of falls when compared with the placebo; the effect was not observed in those who are given lower dose of vitamin D2.55 This result is consistent with a meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials including a total of 1,237 elderly subjects showing that supplementation of vitamin D intake reduced the risk of falls by 22% as compared with only calcium or placebo. This meta-analysis also suggested that trials that gave 800 IU of vitamin D3/day plus calcium significantly reduced the risk of fall, whereas the results from a trial that gave 400 IU of vitamin D3/day did not show the effectiveness of vitamin D3in prevention of falls.53 According to this evidence, it can be concluded that supplementation of vitamin D by at least 800 IU/day along with calcium can prevent the risk of falls, while giving lower dose of vitamin D failed to demonstrate the effect.

8.4. Non-skeletal clinical outcomes

Several observational studies have reported the association between robust levels of serum 25(OH)D in the range of 40–60 ng/mL with decreased risk of development of several types of cancers including Hodgkin lymphoma, colon, prostate, breast, and other cancers.15 Furthermore, people with high serum 25(OH)D levels are observed to have lower rate of cardio-metabolic disorders including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes and peripheral arterial disease, all of which are risk factors for stroke, myocardial infarction, and mortality.15,22 Despite the promising laboratory and epidemiological data, the cause-effect relationship of these observations remains controversial as most previous randomized controlled trials failed to prove the benefit of vitamin D in prevention of cardiovascular diseases and cancers.56

It is thought that the observed association between living in lower latitudes and reduction of the risk of autoimmune diseases is mediated by the immunomodulatory effect of sunlight and vitamin D.57 The risk of multiple sclerosis decreased by 41% for every increase of 20 ng/mL in 25(OH)D above approximately 24 ng/mL among Caucasian men and women.58 Women who took more than 400 IU of vitamin D per day were 42% less susceptible to multiple sclerosis.59 Similar findings have been reported for rheumatoid arthritis.60 A study in Finland conducted a study in 10,366 children who were given 2000 IU of vitamin D3/day during their first year of life and were followed for 31 years showed the reduction of the risk of type 1 diabetes by approximately 80%. Those who were vitamin D-deficient were found to have increased risk by around 200%.61 Furthermore, increasing prenatal vitamin D intake is found to lower the risk of the development of islet autoantibodies in offspring.62

9. Diagnosis and management of vitamin D deficiency

Screening of vitamin D deficiency by measurement of serum 25(OH)D is recommended in individuals at risk as shown in Table 4.16 There are multiple methods for measurement for 25(OH)D, including radioimmunoassay, high performance liquid chromatography, and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy.63 In clinical practice, it is important to know if an assay measures total 25(OH)D or only 25(OH)D3. Using assays that measure only 25(OH)D3 could underestimate total blood levels of 25(OH)D and may mislead physicians who treat vitamin D-deficient patients with vitamin D2 supplementation.64, 65, 66 More importantly in countries such as India where milk and cooking oil are fortified with vitamin D2 these assays will be unreliable in providing an accurate blood level for total 25(OH)D.

Table 4.

Indications for screening of vitamin D deficiency.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adapted from Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011; 96(7):1911–30.

Recommended vitamin D intake in children and adults who are at risk for vitamin D deficiency and dosage of vitamin D therapy for patients with vitamin D deficiency is summarized in Table 5. In vitamin D-deficient obese patients, patients with malabsorptive conditions, and patients who are receiving medications affecting vitamin D metabolism, dosage of vitamin D therapy should be increased 2–3 times higher than in normal individuals.22 In pregnant women 4000 IUs daily was effective in raising 25(OH)D blood levels in the range of 40–60 ng/mL. Recent studies suggests that blood 25(OH)D levels of 40–60 ng/mL is associated with reduced risk for preeclampsia, need for a cesarean section, and premature births.67 Since human breast milk essentially contains no vitamin D lactating women should take 6000 IUs daily. By doing so they add enough vitamin D to their milk to satisfy their infant's requirement. Otherwise the infant requires 400–600 IUs daily as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and Endocrine Society.16

Table 5.

The Endocrine Society Practice Guidelines for vitamin D intake in individuals who are at risk for vitamin D deficiency and dosage of vitamin therapy treatment for patients with vitamin D deficiency.

| Age group | For individuals at risk for vitamin D deficiency |

Treatment for patients with vitamin D deficiency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily requirement | Upper limit | ||

| 0–1 yr | 400–1000 IU | 2000 IU |

|

| 1–18 yr | 600–1000 IU | 4000 IU |

|

| >18 yr | 1500–2000 IU | 10,000 IU |

|

Adapted from Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011; 96(7):1911–30.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

Nipith Charoenngam and Arash Shirvani do not any financial or nonfinancial potential conflict of interest. Michael F. Holick is a consultant for Quest Diagnostics Inc. and Ontometrics Inc, and on the speaker's Bureau for Abbott Inc.

Authors’ contributions

All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

Learning points

-

•

Vitamin D plays an essential role in regulating calcium and phosphate metabolism and maintaining a healthy mineralized skeleton.

-

•

Approximately 1 billion people worldwide are vitamin D-deficient or insufficient. This is attributed to a modern lifestyle and environmental factors that restrict sunlight exposure.

-

•

Measurement of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is used for determining vitamin D status, and is indicated for screening for vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency in individuals at risk.

-

•

The Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice Guideline defines vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency as serum concentrations of 25(OH)D of <20 ng/mL, 21–29 ng/mL, and 30–100 ng/mL, respectively.

-

•

Vitamin D deficiency is the most common cause of rickets and osteomalacia, and can exacerbate osteoporosis. It is also associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain, muscle weakness, and an increased risk of falling in the elderly.

-

•

Robust levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is associated with decreased mortality and risk of several types of chronic diseases.

-

•

Vitamin D-deficient patients should be treated with vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 supplementation to achieve an optimal level of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

-

•

Using assays that recognize only 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 could underestimate total levels of 25(OH)D in patients receiving vitamin D2 supplementation.

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge Yuhao Huangfu (John) for his assistance in making figures for this review and Tyler Arek Kalajian for his assistance in proofreading this review.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2019.07.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Hess A.F. Henry Kimpton; London W.C.: 1930. Rickets Including Osteomalacia and Tetany. 263, High Holborn; p. 485. xv + [Google Scholar]

- 2.Still G.F. London EOUP, Humphrey Milford; 1931. The History of Pediatrics. The Progress of the Study of Disease of Children up to the End of XVIIIth Century. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick M.F. Resurrection of vitamin D deficiency and rickets. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2062–2072. doi: 10.1172/JCI29449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huldschinsky K. Heilung von Rachitis durch künstliche Höhensonne. Dtsch med Wochenschr. 1919;45(26):712–713. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajakumar K., Greenspan S.L., Thomas S.B., Holick M.F. SOLAR ultraviolet radiation and vitamin D: a historical perspective. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1746–1754. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellanby E. An experimental investigation on rickets. Nutrition. 1919;5(2):81–86. 1989. discussion 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shipley P.G.P.E., McCollum E.V., Simmonds N., Parsons H.T. Studies on experimental rickets, II: the effect of cod liver oil administered to rats with experimental rickets. J Biol Chem. 1921;45:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCollum E.V.S.N., Becker J.E., Shipley P.G. Studies on experimental rickets, XXI: an experimental demonstration of the existence of a vitamin which promotes calcium deposition. J Biol Chem. 1922;53:293–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess A.F.W.M. Antirachitic properties imparted to inert fluids and to green vegetables by ultra-violet irradiation. J Biol Chem. 1924;62:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess A.F.W.M., Helman F.D. The antirachitic value of irradiated phytosterol and cholesterol. Int J Biol Chem. 1925;63:305–309. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holick M.F. Vitamin D is not as toxic as was once thought: a historical and an up-to-date perspective. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(5):561–564. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alamoudi L.H., Almuteeri R.Z., Al-Otaibi M.E. Awareness of vitamin D deficiency among the general population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Nutr Metabol. 2019;2019:7. doi: 10.1155/2019/4138187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergwitz C., Jüppner H. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annu Rev Med. 2010;61:91–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.051308.111339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norman A.W. Vitamin D: Physiology, Molecular Biology, and Clinical Applicationsedited by Michael F Holick, 1999, 457 pages, hardcover, $175.00. Humana Press, Inc, Totowa, NJ. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(4) 578-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen C.J., Adams J.S., Bikle D.D. The nonskeletal effects of vitamin D: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(3):456–492. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holick M.F., Binkley N.C., Bischoff-Ferrari H.A. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):1911–1930. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malabanan A., Veronikis I.E., Holick M.F. Redefining vitamin D insufficiency. Lancet. 1998;351(9105):805–806. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)78933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heaney R.P., Dowell M.S., Hale C.A., Bendich A. Calcium absorption varies within the reference range for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22(2):142–146. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holick M.F., Siris E.S., Binkley N. Prevalence of Vitamin D inadequacy among postmenopausal North American women receiving osteoporosis therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3215–3224. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapuy M.C., Schott A.M., Garnero P., Hans D., Delmas P.D., Meunier P.J. Healthy elderly French women living at home have secondary hyperparathyroidism and high bone turnover in winter. EPIDOS Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(3):1129–1133. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Shao A., Dawson-Hughes B., Hathcock J., Giovannucci E., Willett W.C. Benefit-risk assessment of vitamin D supplementation. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(7):1121–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holick M.F. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(19):1980–1982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc072359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wacker M., Holick M.F. Sunlight and Vitamin D: a global perspective for health. Dermatoendocrinology. 2013;5(1):51–108. doi: 10.4161/derm.24494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holick M.F. High prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy and implications for health. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(3):353–373. doi: 10.4065/81.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas M.K., Lloyd-Jones D.M., Thadhani R.I. Hypovitaminosis D in medical inpatients. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(12):777–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803193381201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tangpricha V., Pearce E.N., Chen T.C., Holick M.F. Vitamin D insufficiency among free-living healthy young adults. Am J Med. 2002;112(8):659–662. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01091-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charoenngam N., Sriussadaporn S. Prevalence of inadequate vitamin D status in ambulatory Thai patients with cardiometabolic disorders who had and had no vitamin D supplementation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2018;101:739–752. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bassil D., Rahme M., Hoteit M., Fuleihan G.E.-H. Hypovitaminosis D in the Middle East and North Africa: prevalence, risk factors and impact on outcomes. Dermatoendocrinology. 2013;5(2):274–298. doi: 10.4161/derm.25111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aparna P., Muthathal S., Nongkynrih B., Gupta S.K. Vitamin D deficiency in India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7(2):324–330. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_78_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nimitphong H., Holick M.F. Vitamin D status and sun exposure in southeast Asia. Dermatoendocrinology. 2013;5(1):34–37. doi: 10.4161/derm.24054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pereira-Santos M., Santos JYGd, Carvalho G.Q., Santos DBd, Oliveira A.M. Epidemiology of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency in a population in a sunny country: geospatial meta-analysis in Brazil. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1437711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J.M., Smith J.R., Philipp B.L., Chen T.C., Mathieu J., Holick M.F. Vitamin D deficiency in a healthy group of mothers and newborn infants. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2007;46(1):42–44. doi: 10.1177/0009922806289311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahay M., Sahay R. Rickets-vitamin D deficiency and dependency. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;16(2):164–176. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.93732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balk E.M., Adam G.P., Langberg V.N. Global dietary calcium intake among adults: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(12):3315–3324. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4230-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potts J.T. Parathyroid hormone: past and present. J Endocrinol. 2005;187(3):311–325. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uday S., Högler W. Nutritional rickets and osteomalacia in the twenty-first century: revised concepts, public health, and prevention strategies. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2017;15(4):293–302. doi: 10.1007/s11914-017-0383-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bendik I., Friedel A., Roos F.F., Weber P., Eggersdorfer M. Vitamin D: a critical and essential micronutrient for human health. Front Physiol. 2014;5:248. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holick M.F., Lim R., Dighe A.S. Case 3-2009. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):398–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcpc0807821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holick M.F. Vitamin D deficiency: what a pain it is. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(12):1457–1459. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Häuser W., Perrot S., Sommer C., Shir Y., Fitzcharles M.-A. Diagnostic confounders of chronic widespread pain: not always fibromyalgia. Pain Rep. 2017;2(3):e598–e. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sözen T., Özışık L., Başaran N.Ç. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017;4(1):46–56. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boonen S., Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Cooper C. Addressing the musculoskeletal components of fracture risk with calcium and vitamin D: a review of the evidence. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;78(5):257–270. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larsen E.R., Mosekilde L., Foldspang A. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation prevents osteoporotic fractures in elderly community dwelling residents: a pragmatic population-based 3-year intervention study. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(3):370–378. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Kiel D.P., Dawson-Hughes B. Dietary calcium and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status in relation to BMD among U.S. adults. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(5):935–942. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill T.R., Aspray T.J. The role of vitamin D in maintaining bone health in older people. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017;9(4):89–95. doi: 10.1177/1759720X17692502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cauley J.A. Defining ethnic and racial differences in osteoporosis and fragility fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):1891–1899. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1863-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macdonald H.M., Wood A.D., Aucott L.S. Hip bone loss is attenuated with 1000 IU but not 400 IU daily vitamin D3: a 1-year double-blind RCT in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(10):2202–2213. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chapuy M.C., Arlot M.E., Duboeuf F. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in elderly women. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(23):1637–1642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dawson-Hughes B., Harris S.S., Krall E.A., Dallal G.E. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(10):670–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patient level pooled analysis of 68 500 patients from seven major vitamin D fracture trials in US and Europe. Bmj. 2010;340:b5463. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Avenell A., Mak J.C., O'Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):Cd000227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ross A.C., Taylor C.L., Yaktine A.L., Del Valle H.B., editors. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences.; Washington (DC): 2011. Institute of medicine committee to review dietary reference intakes for vitamin D, calcium. The national academies collection: reports funded by national institutes of health. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Giovannucci E., Willett W.C., Dietrich T., Dawson-Hughes B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(1):18–28. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boland R.L. VDR activation of intracellular signaling pathways in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;347(1-2):11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Broe K.E., Chen T.C., Weinberg J., Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Holick M.F., Kiel D.P. A higher dose of vitamin D reduces the risk of falls in nursing home residents: a randomized, multiple-dose study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):234–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manson J.E., Cook N.R., Lee I.M. Vitamin D supplements and prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;380(1):33–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cantorna M.T., Zhu Y., Froicu M., Wittke A. Vitamin D status, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, and the immune system. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6) doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1717S. 1717S-20S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munger K.L., Levin L.I., Hollis B.W., Howard N.S., Ascherio A. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2006;296(23):2832–2838. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.23.2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Munger K.L., Zhang S.M., O'Reilly E. Vitamin D intake and incidence of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62(1):60. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000101723.79681.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merlino L.A., Curtis J., Mikuls T.R., Cerhan J.R., Criswell L.A., Saag K.G. Vitamin D intake is inversely associated with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(1):72–77. doi: 10.1002/art.11434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hyppönen E., Läärä E., Reunanen A., Järvelin M.-R., Virtanen S.M. Intake of vitamin D and risk of type 1 diabetes: a birth-cohort study. The Lancet. 2001;358(9292):1500–1503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fronczak C.M., Barón A.E., Chase H.P. In utero dietary exposures and risk of islet autoimmunity in children. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3237. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farrell C.-J., Herrmann M. Determination of vitamin D and its metabolites. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2013;27(5):675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee J.H., Choi J.-H., Kweon O.J., Park A.J. Discrepancy between vitamin D total immunoassays due to various cross-reactivities. J Bone Metab. 2015;22(3):107–112. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2015.22.3.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jones G. Interpreting vitamin D assay results: proceed with caution. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):331–334. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05490614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ferrari D., Lombardi G., Banfi G. Concerning the vitamin D reference range: pre-analytical and analytical variability of vitamin D measurement. Biochem Med. 2017;27(3) doi: 10.11613/BM.2017.030501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Holick M.F. A call to action: pregnant women in-deed require vitamin D supplementation for better health outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;104(1):13–15. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.