To the Editor:

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that is estimated to affect 26 million people in the United States as of 2016 (1). As the U.S. population ages, there are more elderly patients older than 65 years who have asthma. Aging has been associated with changes in asthma pathophysiology, symptoms, and response to therapy (2). Higher morbidity and mortality have been associated with this population. The reasons for this are multifaceted. These patients tend to underperceive their symptoms, and they are underdiagnosed and undertreated. Asthma in the elderly has been associated with more severe and difficult-to-treat asthma, and it is associated with higher inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β-agonist use compared with adult patients with asthma aged 45 years and younger (3). Asthma mortality is highest in the population older than 65 years, even after adjusting for other age-related comorbidities (4).

Differences in asthma severity have also been observed in women and black patients. Women have more severe asthma, higher hospitalization rates, and higher mortality rates (4, 5). Black patients with asthma have poorer asthma control, more emergency room visits, and more treatment failures (6, 7). In this letter, we investigate the trends in asthma mortality in the United States from 1999 to 2015 and explore the variation in different age groups, sex, and race. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (8).

Methods and Results

We conducted a population-based study using data collected by the CDC’s National Asthma Control Program on asthma prevalence, and the CDC’s Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), based on death certificates for US residents from 1999 to 2015. Results were adjusted for changes in the age and population structure during the study period from 1999 to 2015. Patients who died from asthma (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, codes: J45 and J46) as the underlying cause of death were selected. Mortality was calculated per 100,000 persons, based on 2000 U.S. Census data. We divided the population into four age groups: 1–14, 15–44, 45–64, and >65 years. The population was also stratified on the basis of sex and race: non-Hispanic white men and women, Hispanic men and women, and African American men and women. Spearman correlation test was used to analyze trends.

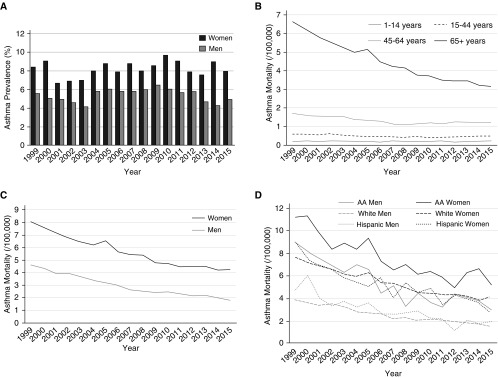

Between 1999 and 2015, a total of 61,815 asthma deaths occurred. The overall mortality rate was 1.5 per 100,000 persons. During the study period, women aged 15 years and older had higher asthma prevalence compared with men (Figure 1A). African American women had the highest age-adjusted asthma mortality (3.4 per 100,000; Figure 1D) compared with the other sex and race groups. Similarly, non-Hispanic white men had the lowest age-adjusted asthma mortality rate (0.9 per 100,000; Figure 1D). The overall incidence of asthma mortality decreased from 2.1 in 1999 to 1.2 in 2015 per 100,000 (43%; P < 0.001). Although this drop in mortality was seen in both sexes and all race groups over the study period (Figures 1C and 1D), mortality in women continued to exceed the mortality in men by twofold (Figure 1C). Asthma mortality decreased over this time across all age groups older than 15 years, but the largest decrease was among patients older than 65 years (Figure 1B). In the youngest age group (1–14 years), the mortality rate is low and has not changed significantly during this period. Mortality in patients aged 15–44 years decreased from 0.72 to 0.61 (15%; P = 0.025). Mortality in patients aged 45–64 years decreased from 1.97 to 1.30 (34%; P < 0.001). Mortality in patients older than 65 years decreased from 7.0 to 3.2 (54%; P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Trends in asthma prevalence and mortality between 1999 and 2015. (A) Asthma prevalence stratified by sex in youth and adults aged 15 years and greater. (B) Asthma mortality stratified by age category. (C) Asthma mortality stratified by sex in patients aged 65 years and older. (D) Asthma mortality stratified by sex and race in patients aged 65 years and older. AA = African American.

Discussion

This study clearly outlines the associations of age, sex, and race on asthma mortality in the United States between 1999 and 2015. Significant racial and sex differences in asthma-related mortality continue to exist, with mortality being highest among African American women and lowest among non-Hispanic white men. The decrease in asthma-related mortality was consistent in both sexes and in all race groups, with the largest decrease in patients older than 65 years.

This decline in asthma-related mortality may be related to overall improvements in the diagnosis and management of asthma. However, research specifically focused on asthma in the elderly is still limited. Older adults, in general, are more likely to have higher rates of severe asthma and asthma-related hospitalization and mortality (3, 9). Yet the prevalence of asthma in adults older than 65 years remains relatively low compared with that of younger adults, which is reported to be between 4.5% and 12.7% (10). Lower prevalence in this age group is probably related to the underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis, often as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, of asthma in older adults (11). There is also evidence that asthma in this population is phenotypically different than asthma in younger patients. Furthermore, treatment failure risk increases with age (2), placing older patients with asthma at higher risk for severe uncontrolled asthma.

Although asthma mortality has dropped by 43% since 1999, older age, female sex, and African American race continue to be associated with higher risk for asthma-related mortality. This reflects the overall complexity of the disease and the interaction of different factors that contribute to disease control. With a greater risk for severe asthma, this group of patients would benefit from targeted interventions geared toward optimizing asthma therapy and improving access to care. In general, with the world population aging, it will become increasingly important to have research focused on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of asthma in older populations.

In summary, asthma-related mortality has declined in all age groups older than 15 years in the United States from 1999 to 2015. Although this decline was seen in both sexes and all races, asthma mortality continues to be higher in women compared with men, African American women in particular. Our findings suggest that improvements in the diagnosis and management of asthma have led to declines in asthma-related mortality. Following these trends in asthma mortality can help to direct focus toward at-risk populations who might benefit the most from targeted interventions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1844LE on March 27, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.CDC. Most recent asthma data, asthma prevalence 2016[accessed 2018 July 27]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm

- 2.Dunn RM, Lehman E, Chinchilli VM, Martin RJ, Boushey HA, Israel E, et al. NHLBI Asthma Clinical Research Network. Impact of age and sex on response to asthma therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:551–558. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0426OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zein JG, Dweik RA, Comhair SA, Bleecker ER, Moore WC, Peters SP, et al. Severe Asthma Research Program. Asthma is more severe in older adults. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zein JG, Udeh BL, Teague WG, Koroukian SM, Schlitz NK, Bleecker ER, et al. Impact of age and sex on outcomes and hospital cost of acute asthma in the United States, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kynyk JA, Mastronarde JG, McCallister JW. Asthma, the sex difference. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:6–11. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283410038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haselkorn T, Lee JH, Mink DR, Weiss ST TENOR Study Group. Racial disparities in asthma-related health outcomes in severe or difficult-to-treat asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:256–263. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wechsler ME, Castro M, Lehman E, Chinchilli VM, Sutherland ER, Denlinger L, et al. Impact of race on asthma treatment failures in the asthma clinical research network. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1247–1253. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0514OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaqoob Z, Al-Kindi S, Zein J.2017. Trends in asthma mortality in the United States: a population-based study. Presented at the Chest 2017 Annual Meeting. Oct 23, 2017, Glenview, IL [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai CL, Lee WY, Hanania NA, Camargo CA., Jr Age-related differences in clinical outcomes for acute asthma in the United States, 2006-2008. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1252–1258, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanez A, Cho SH, Soriano JB, Rosenwasser LJ, Rodrigo GJ, Rabe KF, et al. Asthma in the elderly: what we know and what we have yet to know. World Allergy Organ J. 2014;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1939-4551-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enright PL, McClelland RL, Newman AB, Gottlieb DJ, Lebowitz MD Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of asthma in the elderly. Chest. 1999;116:603–613. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.