Abstract

The current gold standard for clinical diagnosis of melanoma is excisional biopsy and histopathologic analysis. Approximately 15–30 benign lesions are biopsied to diagnose each melanoma. In addition, biopsies are invasive and result in pain, anxiety, scarring, and disfigurement of patients, which can add additional burden to the health care system. Among several imaging techniques developed to enhance melanoma diagnosis, optical coherence tomography (OCT), with its high-resolution and intermediate penetration depth, can potentially provide required diagnostic information noninvasively. Here, we present an image analysis algorithm, “optical properties extraction (OPE),” which improves the specificity and sensitivity of OCT by identifying unique optical radiomic signatures pertinent to melanoma detection. We evaluated the performance of the algorithm using several tissue-mimicking phantoms and then tested the OPE algorithm on 69 human subjects. Our data show that benign nevi and melanoma can be differentiated with 97% sensitivity and 98% specificity. These findings suggest that the adoption of OPE algorithm in the clinic can lead to improvements in melanoma diagnosis and patient experience.

Introduction

Melanoma is an increasingly important public health problem worldwide. The incidence of melanoma has been rising faster than any other cancer, mainly due to changes in sun exposure behavior as well as climate change (1). Melanoma was responsible for 59,782 global deaths in 2015 with an age-standardized rate of one death per 100,000 persons (2).

Healthy and nonhealthy tissues can be well differentiated on the basis of their characteristics. There are characteristic differences in the number, size, and distribution of melanocytes seen in healthy skin, nevi, and melanoma. In healthy skin, melanocytes occur singly along the basal layer of epidermis at the rate of approximately 1 for every 10 keratinocytes. In benign nevi, there is an increase in the number of melanocytes and they occur grouped into nests, but they maintain their normal size. In melanoma, there is an increase in the number of melanocytes and the cells are larger and atypical. The atypical melanocytes are frequently seen in the layers of epidermis above the basal layer, known as pagetoid spreading.

Traditionally, the process of diagnosing a melanoma begins with visual inspection of the skin lesions. Visual evaluation criteria for suspected melanomas include the “ABCDE” criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter > 6 mm, Evolving; ref. 3). Skin lesions that fulfill the ABCDE criteria for melanoma are then biopsied for histopathologic analysis. The specificity (~59%–78%; ref. 4) of visual inspection criteria varies widely based on the experience of a clinician and when used singly or in combination. This wide variability in the specificity is due to both subjective interpretation by physicians as well the variability in the number of criteria present in a given suspicious lesion. This results in unnecessary biopsy of many benign lesions, ranging from 15 to 30 benign lesions, biopsied to diagnose one melanoma (5). Performing a biopsy can result in pain, anxiety, scarring, and disfigurement for patients as well as a cost for the healthcare system. Another challenge is finding the correct lesion(s) to biopsy in a patient with many pigmented lesions. Toward addressing these challenges, several imaging techniques have been developed to noninvasively image melanoma; however, each of these technologies has inherent limitations. The optimal imaging parameters for the detection of melanoma have not been clearly established. However, penetration depth reaching at least the papillary dermis is necessary to detect the melanoma invasion and differentiate invasive melanoma from melanoma in situ. Resolution at the cellular level is desirable to make the diagnosis based on histologic differences between benign and malignant melanocytes; however, lower resolution devices can still be used for detecting architectural differences between melanoma and benign nevi. The limitations of various imaging systems are as follows: dermoscopy depends on the appearance of the classic dermoscopic features (6), and, therefore, has limited utility in the diagnosis of very early and mainly featureless melanomas (7). Dermoscopy also cannot plan the excision because the margins of the excision rely on the Breslow depth. Multispectral imaging captures the image data within specific wavelength ranges across the electromagnetic spectrum; these data, however, are projected on the same plane, obscuring depth information (8). Reflectance confocal microscopy provides cellular information on melanocytic lesions; however, its penetration depth is too limited to detect invasive melanoma (9). High-frequency ultrasound has a satisfactory penetration depth to detect the size and shape of a tumor, but low resolution and low specificity preclude diagnosis of the actual type of malignancy (10). Recently, raster scanning photoacoustic (PA) microscopy and cross-sectional PA tomography have been explored for diagnosis and staging of melanoma (11, 12) in which melanin serves as an endogenous contrast agent. However, melanin is not a tumor-specific biomarker of melanoma as it is present in benign nevi and may actually be absent in amelanotic melanoma (13). There have been several melanoma detection devices marketed such as MelaFind (14), SIAscop (15), Verisante Aura (16), and Nevisence (16). These devices were developed to assist clinicians with any level of experience in the detection of melanoma and subsequently rely on histopathologic assessment. However, these devices suffer various drawbacks that result in the limited specificity [68% (8), 77% (17), 68% (18), and 34% (19) respectively)] and/or sensitivity [93% (8), 81% (17), 90% (18), and 94% (19), respectively] and are therefore of limited benefit to the clinician. The Melafind and SIAcope devices utilize visible/NIR cameras to obtain images of lesions at multiple wavelengths and then apply machine-learning algorithms to the resulting image sets to try to distinguish melanomas from benign nevi. These longer wavelengths (near-infra-red) images provide subsurface details; however, results are reported from all layers simultaneously obscuring essential depth information. The Verisante Aura utilizes Raman spectroscopy to analyze the chemical “fingerprint” of the lesion, but also has no depth discrimination. The Nevisense device is a nonoptical machine that analyses the electrical impedance spectrum of a lesion detected from tiny electrodes inserted into the tissue. However, Nevisense does not accurately differentiate nevi from melanoma. To date, none of these devices has been widely adopted by clinicians. A key challenge with any device that purports to diagnose melanoma is setting the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. Clearly, one desires maximum sensitivity to minimize the risk of missing a potentially fatal melanoma, but when set up to do this, the device may produce an unacceptably high false-positive rate from benign lesions due to poor specificity and so offers little benefit to the clinician over using dermoscopy and their experience. Some of these devices can produce a measurement of “risk level” for diagnosing melanoma, but this then requires the user to decide “what is an acceptable level of risk.” Therefore, there is a persistent unmet need for a melanoma diagnosis device with high sensitivity and specificity.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) with a high spatial resolution (<10 microns), intermediate penetration depth (~1.5 to 2 mm), and volumetric imaging capability has become a popular diagnostic-assistant modality in dermatology, especially to detect and diagnose nonmelanoma skin tumors (20), for example, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (21–23). Contrast in OCT images is generated by the intrinsic scattering characteristics of the tissue that are proportional to the density, size, and shape of the tissue microstructures (24). Because malignant cells show pleomorphism with different refractive indices and absorption characteristics than normal cells, based on light–tissue interaction theories (25), OCT images should discriminate malignant tissues from normal tissues and benign neoplasms (26, 27). However, the specificity of OCT for melanoma detection is lower than anticipated. Several groups including ours (28) have attempted to increase such specificity by image enhancement (29, 30), texture analysis (31–34), even implementing more sophisticated configurations of OCT, including polarization-sensitive, phase-sensitive, and dynamic OCT; these have also failed to adequately discriminate between melanoma and benign lesions. Ostensibly, the aggregation of the predominant optical properties that contribute to OCT image formation diminishes the specificity of melanoma detection. We have developed an optical properties extraction (OPE) algorithm, based on the Extended Huygens–Fresnel (EHF) model (35), to disaggregate the OCT image into its individual optical attributes, that is, tissue-scattering coefficient, absorption coefficient, and anisotropy factor. We then identified unique optical radiomic signatures pertinent to melanoma detection among the extracted optical properties and trained a machine-learning kernel; this is the basis of our optical radiomic melanoma detection (ORMD) protocol. The ORMD protocol is applied to OCT images of the suspect lesion and will provide the clinician with clear information on the tissue status, for example, “Tissue sample is consistent with healthy tissue,” “Tissue sample exhibits characteristics consistent with melanoma.”

This algorithm will (i) reduce the number of unnecessary biopsies by helping identify the most probable malignant lesion in a person with multiple pigmented spots, which will result in fewer biopsies and less pain, anxiety, scarring, and disfigurement for patients; (ii) considerably reduce cost to the healthcare system; and (iii) detect melanoma in its early stage, when prognosis is optimal. Importantly, the optical properties come at no additional cost as they are embedded in the existing image data and can readily be extracted via postprocessing applicable to virtually all OCT systems.

Materials and Methods

Imaging system

In this study, we used a multi-beam, swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) system (Vivosight, Michelson Diagnostic Inc.; see Supplementary Fig. S1). The OCT system is an FDA-approved machine with a hand-held scanning probe for skin imaging. The lateral and axial resolutions are 7.5 μm and 10 μm, respectively. The scan area of the OCT system is 6 mm (width) × 6 mm (length) × 2 mm (depth), with a frame rate of 20 frames/second. A tunable broadband laser source (Santee HSL-2000-11-MDL), with central wavelength of 1,305 ± 15 nm, successively sweeps through the optical spectrum and leads the light to four separate interferometers and forms four consecutive confocal gates.

OPE algorithm and EHF model

The light–tissue interaction specific to OCT imaging, that is, OCT modeling, was initiated by Schmitt who considered only scattering coefficient for modeling using the single-scattering theory, that is, the ballistic component only (36). Studies have shown that the primary effect of multiple scattering is a less steep slope of signal decay with depth, than predicted by the so-called single-scattering model. Since then, several other groups have considered a quantitative analysis of OCT images to improve diagnosis (37–40). The first model that adequately includes the ballistic light component and multiple scattered light is an analytic solution to the scalar wave equation based on the mutual coherence functions, known as the Extended Huygens–Fresnel (EHF) principle. It includes diffraction effects and it allows Gaussian beam under any focusing condition (35, 41). We have integrated the lateral coherence length variation with depth into previous models by considering the so-called “shower curtain effect.” The model describes the heterodyne OCT signal as a function of depth. This model incorporates both multiple scattering and single scattering effects. Later, we employed the EHF principle and proposed an OCT model in a multilayer-scattering geometry (35, 42). Here, we apply a further extension to our previous model with the addition of a third parameter, absorption coefficient, to scattering coefficient and anisotropy factor. The mean squared of the OCT heterodyne signal current at the probing depth z is described as:

| (A) |

where is the mean squared heterodyne signal current in the absence of scattering and absorption, a is a constant characterized by the OCT system setup, and is 1/e irradiance radius at the probing depth in the absence of scattering:

| (B) |

where A and B are the elements of the ABCD matrix for light propagation from the lens plane to the probing depth in the sample. If the focal plane of the beam is fixed on the surface of the sample, then A = 1 and B = f + z/n, where n is the refractive index, and f is the focal length of the lens, w0 represents the 1/e irradiance radius of the input sample beam at the lens plane. k = 2π/λ, and λ is the wavelength of the light source. ψSA(z) is the heterodyne efficiency factor describing signal degradation due to scattering and absorption, see Eq. C.

| (C) |

The first term in the brackets represents the single-scattering effect, the third term is the multiple-scattering term, and the second term is the cross term including both single and multiple scattering. wsA is the 1/e irradiance radius at the probing depth in the presence of scattering and absorption:

| (D) |

where ρ0 is the lateral coherence length given by:

| (E) |

where θrms is the root mean squared scattering angle, defined as the half-width at 1/e maximum of a Gaussian curve fitted to the main frontal lobe of the scattering phase function, and nR is the real part of refractive index. Also, ΔzN and ΔzD are presented by equations F and G:

| (F) |

| (G) |

Implementation of OPE algorithm

The OPE algorithm was implemented in MATLAB2015a. w0, λ, and f are inputs to the algorithm (the exact values have been acquired from Michelson Diagnostics Inc.). The optical properties obtained from the OPE algorithm are scattering and absorption coefficients and anisotropy factor.

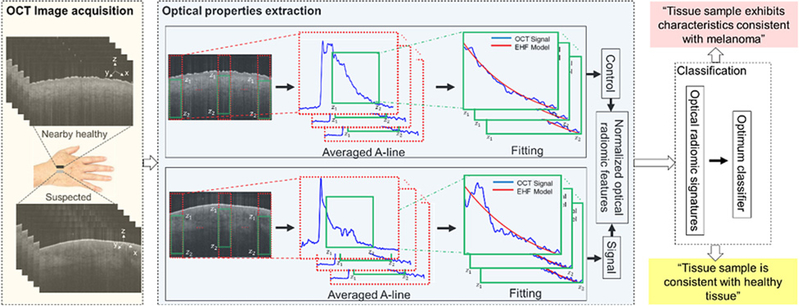

Implementation of the OPE algorithm is as follows (see Fig. 1): an region of interest (ROI) is selected in a preprocessed B-scan OCT image (details of preprocessing are in the Preprocessing Section of the Supplementary document); the green rectangles in Fig. 1 demarcate the selected ROI from which the optical properties are calculated. The pixel intensities along the x-axis in the ROI are averaged to obtain an averaged A-line. For the fitting, a modified exhaustive search algorithm is utilized (43).

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the principles of the optical radiomic melanoma detection protocol. The steps include: acquisition of OCT images from suspected and a nearby healthy skin; the OCT B-scans are preprocessed; optical properties are extracted from the green box (z1 and z2 represent the start and end points of the ROI) by fitting the EHF model to intensity profile of the averaged A-line obtained from the ROI; the values are the mean and SD of scattering coefficient, absorption coefficient, and anisotropy factor extracted from the suspected (we call it signal) and nearby healthy (we call it control) skin to create a set of normalized optical radiomic features; the selected optical radiomic features, that is, optical radiomic signatures, with the optimum classifier evaluate the status of the tissue: “Tissue sample is consistent with healthy tissue,” “Tissue sample exhibits characteristics consistent with melanoma.”

The OPE algorithm adjusts the scattering and absorption coefficients as well as the anisotropy factor in the modeled OCT signal, to obtain a curve that best fits the averaged A-line; that is, to minimize the sum of the differences, (F(μsi, θrmsi, xdatai) − ydatai), where, F(μs, θrms, xdata), is the modeled OCT signal, xdata is a vector including the indices of the pixels of the ROI from depth z1 to z2 in the axial direction, ydata is the smoothed averaged A-line intensity vector, z1 corresponds to the index of the start pixel of the ROI, and z2 corresponds to its end. The fitting error was calculated using l1 norm described as below (Eq. H).

| (H) |

where n is the number of signal elements, i is the pixel index in depth, signalOCT(i) is the averaged OCT A-line, and signalmodel(i) is the corresponding EHF model heterodyne signal, calculated from Eq. A; a smaller error correlates to a better fit and a more robust result is obtained.

Statistical analysis

We used ANOVA to test the global difference among the experimental settings. The null hypothesis was that there was no difference among the experiment settings. For the similarity measure, we used the equivalence test at 5% level of significance. In this test, the null hypothesis was that the absolute difference between the means of two experimental settings is larger or equal to a threshold value Δ. (i.e., H0: | meanA − meanB | ≥ Δ). Different values of delta were chosen for different settings and the values were based on our preliminary results for clinical importance. The rejection of the null hypothesis indicates the equivalence of two conditions. All the other statistical tests were two-sided at 5% level of significance. Matlab Version 2015a was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Phantom study

To evaluate the OPE algorithm, we created phantoms, using milk and ink, with optical characteristics similar to skin in a comparative study. The advantages of milk are its well-known optical properties (44), the similarity of its microparticles to organelles that constitute the scattering sources in tissue (45), and its homogeneity and accessibility at different concentrations. Various concentrations of milk (Horizon Organic Milk) were obtained by mixing it with varying quantities of distilled water and India ink (#385460, Speedball Art Products) to make milk and milk-ink phantoms.

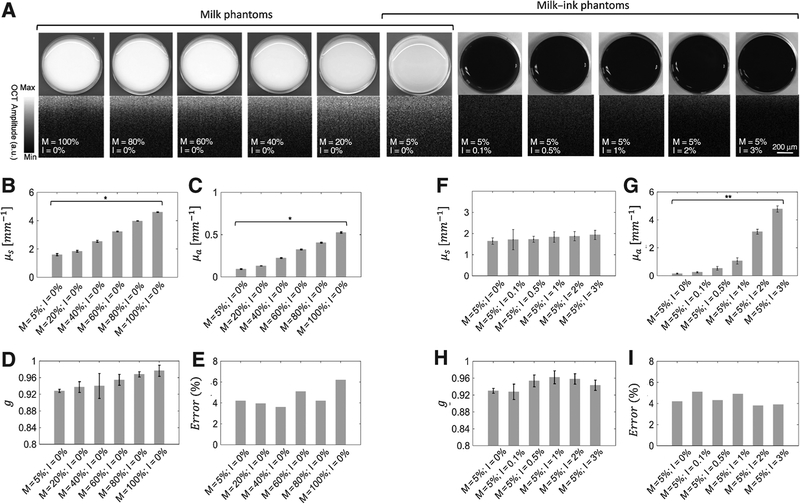

The concentrations of milk in water were 5%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%, and those of ink were 0%, 0.1%, 0.5%, 1%, 2%, and 3% (see Supplementary Table S1). The photographic and OCT images of the phantoms and the values of the scattering coefficients, absorption coefficients, anisotropy factors, and error bars for 10 runs, are given in Fig. 2A–I.

Figure 2.

Phantom study. Photographic and OCT images of milk and milk-ink phantoms (A), scattering coefficients (μs; B and F); absorption coefficients (μa; C and G); anisotropy factors (D and H); and fitting error (G, E, and I). *,P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01. x-axis shows the concentration of milk diluted by water. M and I in the x-axis show the concentration of milk and ink diluted by water.

In vivo study

A motorized, triaxial holder was used to fix the OCT probe, described in the Materials and Methods section, to ensure that the probe is stable during imaging. The OCT probe was placed in the middle of the suspected lesion, based on the bright-field image provided by miniaturized camera integral to the OCT system and the red indicator beam. A volume of 6 mm (L) × 6 mm (W) × 2 mm (D) was scanned and 600 cross-section images with 10 μm span were generated.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on the AC Camargo Ethics Committee guidelines and on known limitations of the device. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age 18 years or older; (ii) able to provide written informed consent prior to any trial-related procedure. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) failure to give written informed consent; (ii), the anatomic site of the lesion not accessible to the device; (iii), the lesion previously biopsied, excised, or traumatized; (4) skin not intact (e.g., open sores, ulcers, bleeding); (v) lesion on palmar, plantar, or mucosal (e.g., lips, genitals) surface or under nails; (vi) lesion containing foreign matter (e.g., tattoo ink, splinter, marker). All of the imaging procedures and experimental protocols were approved and carried out according to the guidelines of the Skin Cancer Department in AC Camargo Cancer Center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrollment in the study. The patients neither refused to sign the written informed consent nor were excluded from the study. OCT images were taken from 69 subjects, aged between 20 and 80 years, in a high-risk dermatology clinic at the Skin Cancer Department in AC Camargo Cancer Center in Brazil. Twenty-three patients with healthy skin, 23 patients assessed with a variety of benign nevi, and 23 patients with at least one suspect melanoma lesion scheduled for biopsy were invited to participate in the trial. See Supplementary Table S2 for details of patients, lesion types, and locations.

For each of the melanoma or benign nevi imaged, adjacent healthy skin was imaged as a control. Two experienced pathologists evaluated all the cases and reported the histopathologic findings as per standard of care. The histology image of the suspected area, as well as the OCT images of both healthy and diseased regions, were recorded. OCT images and histology photographs for ten selected melanoma and benign nevi cases are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2 together with OCT images of their nearby healthy skin.

To prepare the images for analysis, an optimum preprocessing strategy was identified and applied (explained in preprocessing section in Supplementary Data). In Supplementary Fig. S3, the steps to choose the optimum preprocessing algorithm are given. The optical properties of healthy skin, melanoma, and benign nevi were then extracted from the images using the OPE algorithm. In the processing procedure, for each patient, three adjacent OCT images (10 μm apart) from the melanoma/benign and three adjacent OCT images from their nearby healthy skin were used for analysis. For each of these three images, 24 ROIs were specified, and the optical properties of these ROIs, including the scattering coefficient, the absorption coefficient and anisotropy factor, were calculated. The mean and SD of optical properties obtained from the 72 ROIs of suspicious images were reported as the optical properties of the imaged lesion and 72 ROIs of nearby healthy images were reported as the optical properties of the imaged nearby healthy tissue. A more detailed description of the algorithm is found in the Materials and Methods section.

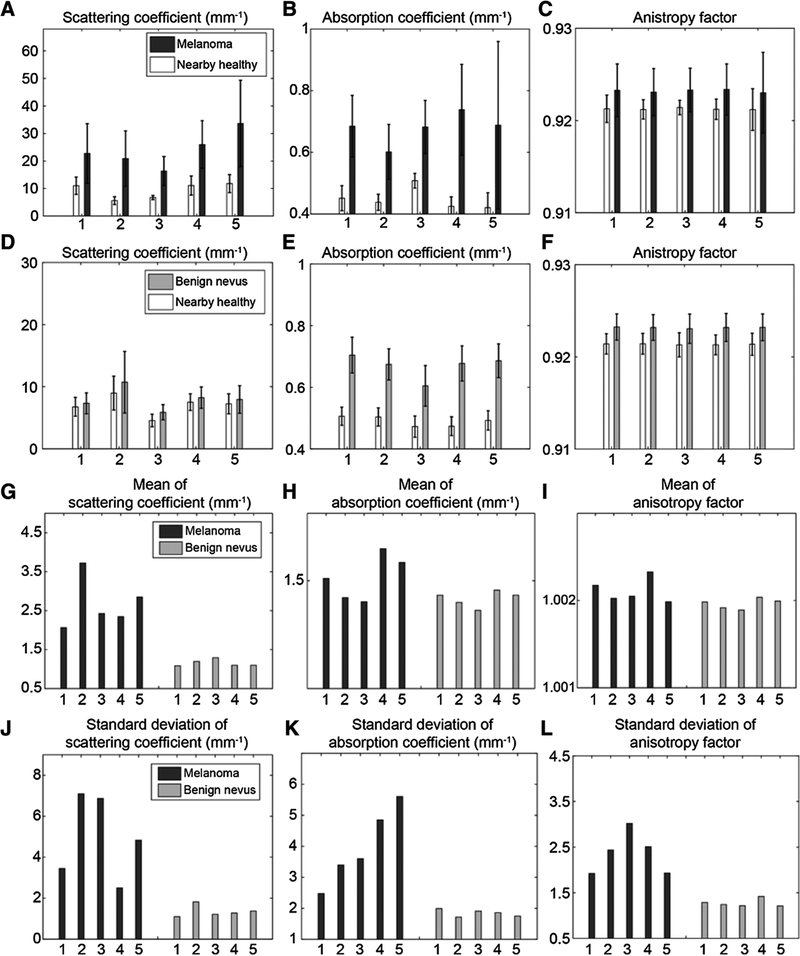

The OPE-derived optical properties for ten, arbitrarily selected cases of melanoma and benign nevi (five each), as well as their nearby healthy skin comparators, are given in Fig. 3A–F. Figure 3G–L shows mean and SD for the same patients to demonstrate, in general, how melanoma and benign nevi skin differ for each optical property extracted. A detailed analysis of these cases is given in Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5. The extracted optical properties from the other 36 cases of melanoma and nevi are given in Supplementary Figs. S6A–S6C and S7A–S7C.

Figure 3.

Optical properties extracted from OCT images of melanoma and benign nevi, and nearby healthy skin for ten arbitrarily selected subjects. Scattering coefficients (A), absorption coefficients (B), and anisotropy factor of melanoma lesions and their nearby healthy skin (C). Scattering coefficients (D), absorption coefficients (E), and anisotropy factor of benign nevi and their nearby healthy skin (F). G-L, Side-by-side comparison of the optical properties, the normalized to nearby healthy tissue of melanoma versus benign nevi: G-l, normalized means of scattering coefficient, absorption coefficient, and anisotropy factor, respectively. J-L, the normalized SDs of the scattering coefficient, the absorption coefficient, and the anisotropy factor, respectively.

Classification

For subjects with dermatologically identified benign nevi and malignant lesions, stacks of 60 OCT images, with a span of 10 μm, were taken. In addition, another stack of images was taken of nearby healthy skin, at a minimum distance of 1.5 cm from the lesion, for data normalization; to compensate for factors related to skin type, age, and gender. The dorsal surface of the hand was imaged for healthy subjects. From each stack, three images acquired from the center of the lesion were selected, and used for the image analysis using our OPE algorithm. For each lesion, six optical radiomic features were obtained; F1,F2, F3, the means of the scattering coefficient, the absorption coefficient, and the anisotropy factor; and F4, F5, F6, the SDs.

Several well-established linear and nonlinear classifiers (46), including Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Linear Regression (LR), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) with different K-values (K = 1, 3, 5, and 7), Linear Support Vector Machine (LSVM), Quadratic SVM (QSVM), and Gaussian SVM (GSVM) were tested using all possible combinations of features. Because of the small number of subjects, we utilized an n-fold cross validation algorithm (47) with 20 folds; that is, each classifier was trained with 20 random combinations of training and test datasets (70% and 30%, respectively). The reported values are the average of 20 measurements, with mean and SDs.

Using all permutations of the six previously obtained features, in combination with each classifier and its various configurations, we have numerous unique discriminators to determine the best values for sensitivity, specificity, Jaccard index, and accuracy (the equations describing these statistics are given in Supplementary Table S3). The best results for each classifier are reported in Supplementary Fig. S8S–S8D). The ROC curve for GSVM classifier was produced by changing the margin factor, that is, C from 0 to 4 with steps 0.1 (see Supplementary Fig. S9). The AUC for each margin was calculated and demonstrated in the Supplementary Fig. S10. Supplementary Table S4 reports an example of the best data for the combinations of four features. Supplementary Table S5 shows the optimum selection of the classifier and the feature combinations for sensitivity, specificity, Jaccard index and accuracy, and in combination. The best overall was a combination of features 1 through 5 with the GSVM classifier (C = 2.1; see Supplementary Table S5).

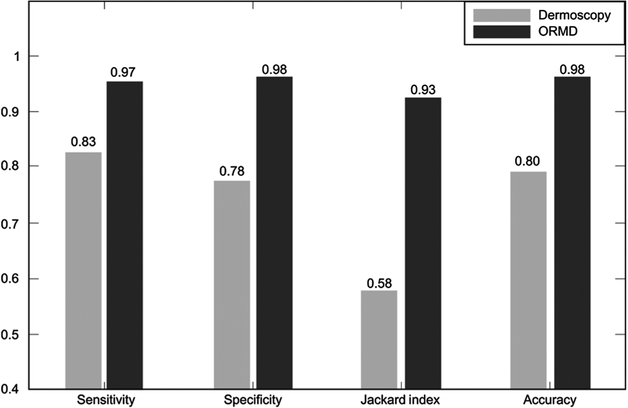

The sensitivity, specificity, Jaccard index, and accuracy of melanoma detection based on dermoscopic criteria and ORMD criteria, when the optimum classifier [GSVM classifier (C = 2.1)] was used with the optical radiomic signatures, including mean and SD of scattering and absorption coefficients, and the mean of the anisotropy factor, are given in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of diagnostic statistics based on dermoscopic and ORMD criteria for the selected optimum classifier [GSVM classifier (C = 2.1)] and optimum feature set.

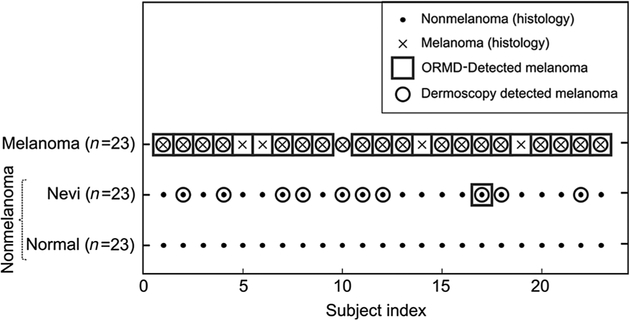

The intention of our methodology is to produce a binary output: (i) “Tissue sample exhibits characteristics consistent with melanoma,” the lesion should be considered for biopsy; or (0) “Tissue sample is consistent with healthy tissue,” the lesion does not require biopsy. The decision of the proposed method and of dermoscopy versus histology results for the subjects used in this study are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Classification results. Comparison of dermoscopic diagnosis, ORMD method, and histology. Nonmelanoma (healthy skin and benign nevi) are marked as dots while melanomas are marked with crosses. The tissue statuses were confirmed by histologic analysis. Circles, detection of melanoma using dermoscopy. Squares, detection of melanoma using the ORMD method. GSVM classifier with the margin factor of 2.1 was used.

Discussion

Malignant melanoma is by far the most dangerous type of skin cancer (1). The initial step in a physician’s decision to biopsy a suspicious lesion is dermoscopic inspection using the ABCDE criteria (3). A lesion that apparently fulfills the ABCDE criteria for melanoma is biopsied for definitive histopathologic diagnosis (3). Several noninvasive imaging approaches have been developed for the diagnosis of melanoma and differentiation from benign nevi. Their clinical utility, however, is limited because they do not provide sufficient specificity and sensitivity.

Tissues have intrinsic scattering characteristics based on the density, size, and shape of tissue microstructures; the absorption characteristics derived from chromophore concentration; and the anisotropy factor, which correlates to cell size and disorder. These characteristics are modified during tumor development. Methods that can uniquely identify these characteristics hold promise for providing diagnostic value (48). OCT is inherently sensitive to the changes of these characteristics (49). However, its sensitivity and specificity in differentiating morphologically similar structures is low, due to the interrelationships of these optical characteristics. Previously, we tried the texture analysis of OCT images, but the improvement was limited (31). Here, we proposed an image analysis algorithm based on the EHF principles, which we call OPE, to disaggregate the OCT image into its individual optical attributes. These optical attributes, when extracted from the OCT image, form a set of tissue-specific optical radiomic features. The method presented here demonstrates significant improvements in melanoma detection over the current clinical methods.

Our initial tests were conducted on milk and milk-ink phantoms, to determine whether the OPE algorithm correctly correlated to changes in optical properties of the phantoms, specifically, scattering and absorption coefficients (see Fig. 2).

We observed the following in the OPE-extracted optical properties: the scattering coefficient (μs) progressed almost linearly with increasing milk concentration (P <0.001); the absorption coefficient (μa) in milk phantoms progressed almost linearly with increasing milk concentration (P <0.001); the absorption coefficient in milk-ink phantoms progressed almost linearly with increasing ink concentration (P <0.01). The results in Fig. 2G appear nonlinear because of the nonlinear scaling of x-axis. The linearized plot is shown in Supplementary Fig. S11. Increasing both absorption and scattering coefficients by increasing the concentration of milk are consistent with the previous studies conducted by Stocker and colleagues (50). This issue does not indicate cross-talk between the scattering and absorption coefficients, but indicates the presence of both scattering and absorption properties in milk; both are accurately extracted using the OPE algorithm. Also, the observed OPE-extracted μs in milk-ink phantoms shows no statistically significant difference (P < 0.001 with Δ = 1[mm−1]). The values of the anisotropy factor (g) also show no statistically significant difference in both milk and milk-ink phantoms (P <0.05 with Δ = 0.03), which is consistent with phantoms being homogenous solutions consisting of scatterers of near-identical size. Different values of delta were chosen for different settings and the values were based on our preliminary results for clinical importance. The average fitting error in both datasets was about 4%. Precision of the obtained values can be improved by using a higher resolution OCT.

The next tests were conducted on human subjects. An optimum preprocessing strategy was identified [Supplementary Figs. S12 (A–O), S13 (A–D), and S14 (A–C)].Our method is noninvasive, the OCT system used is FDA approved, and we acquired IRB approval for testing on human subjects. A block diagram of the proposed method, when used in the clinic, is given in Fig. 1. Sixty-nine melanoma, benign nevi, and healthy subjects were recruited (see Supplementary Table S2). The results obtained from the clinically identified melanoma to nonmelanoma area showed a meaningful difference (see Fig. 3). The Differences due to factors such as skin type, ethnicity, sun exposure, etc., were negated when normalized to nearby healthy skin. The large SD of the optical radiomic features for melanoma images correlates to irregularity in tissue structure, signifying disease. Our results were consistent with the finding that the scattering and absorption coefficients increase with the concentration of melanocytes (melanocyte frequency – melanoma: 71% ± 11%; benign nevi: 18% ± 3%; healthy: 14% ± 3%); anisotropy factor increased with cell size (average mean diameter of 200 consecutive melanocytes -melanoma: 16 ± 3 μm; benign nevi: 7 ± 0.4 μm; healthy: 6 ± 0.4 μm) and tissue disorder due to cellular displacement. This was also observed in simulations using the OMLC online Mie calculator (Supplementary Tables S6–S8; ref. 51).

We propose that increases in scattering and absorption coefficients, as can be seen in Fig. 3, may be due to increased concentration of melanocytes, and the increase in anisotropy factor may be due to increased cell size. The combination of increased numbers of melanocytes that are larger with pleomorphic nuclei is the hallmark of melanoma on pathologic assessment (52).

Six optical radiomic features are generated by the OPE algorithm from the OCT images. These are the mean and SD of the scattering coefficient, the absorption coefficient, and the anisotropy factor. As there are only six features, we were able to examine each possible combination of features to identify the optimal feature set (46). This exhaustive search reaches the optimal feature sets, because it systematically enumerates all possible candidates, it finds the optimal feature set more efficiently, compared with other similar methods designed for feature selection, such as sequential floating forward search and sequential floating backward search (46).

As for the criteria to choose the most appropriate classifier, we need to estimate the true class probability density function (46). With small to medium size datasets, such a function cannot accurately be estimated, and the performance of classifiers is difficult to calculate. As a rule of thumb, low variance classifiers (i.e., Naïve Bayes, SVM) are preferred for such datasets. The recommended method in this case is to find the best classifier with the aid of validation/training and a repeated random sampling strategy (53). We selected six established classifiers; each was trained and tested on the data using a 20-fold cross-validation algorithm; this evaluates the classifier generalization. The values for sensitivity, specificity, Jaccard index, and the accuracy, were determined by testing all permutations of the six features, in combination with each classifier [see Supplementary Fig. S8A–S8D; Supplementary Tables S4 and S5]. On the basis of the clinical requirements of high specificity and sensitivity, a specific classifier and set of features were selected. Some combinations generated high sensitivity with low specificity or vice versa. For example, features F2, F3 with the GSVM (C = 1) classifier resulted in the best sensitivity (99%) with a specificity of 50% (for more examples, see Supplementary Table S5). The best overall was a combination of features through F5 with GSVM classifier; results were sensitivity (97% ± 3%), specificity (98% ± 2%), Jaccard index (93% ± 5%), and accuracy (98% ± 2%; see Fig. 4). For the preferred classifier, GSVM, we calculated AUC with different C-values, and C = 2.1 gave us the best results (see Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10).

Using a computer with a Core i7 CPU and 8 GB memory, with MATLAB2015a, it took 1.2 seconds to assess a suspected lesion with input of OCT images from healthy and suspect tissue. Using lower level programming languages, for example, C and parallel processing, the computation time will greatly be improved.

The dermoscopic analysis was made using the two-step algorithm followed by Pattern Analysis (54, 55). Two experienced dermatologists, T. Blumetti and A.F. Moraes, from the dermatology clinic at the Skin Cancer Department in AC Camargo Cancer Center in Brazil performed the dermoscopic analysis. The suspicious lesions were selected on the basis of changes on dermoscopic follow-up. Assessment of dermoscopy images compared with the results of the ORMD methodology showed a significant diagnostic improvement (see Fig. 5). Using ORMD, only one unnecessary biopsy for melanoma was performed, while dermoscopy identified 10 benign nevi as possible melanoma, necessitating 10 biopsies. In melanoma, OPE missed one case, where dermoscopy misdiagnosed four cases as benign nevi, resulting in delayed treatment.

The statistics indicate that ORMD-based diagnosis is reliable and can effectively differentiate between melanoma and nonmelanoma cases (see Figs. 4 and 5), a larger number of subjects is required to make a more rigorous conclusion. Overall, the rate of unnecessary biopsies is significantly decreased with the use of ORMD methodology. A larger number of subjects may necessitate the use of a more sophisticated classification algorithm, which may farther increase the accuracy of ORMD methodology and minimize the number of misdiagnoses. The next practical challenge for the proposed method is the development of a real-time, 3D melanoma margin detection algorithm for use during the biopsy.

Supplementary Material

Significance:

This study describes a noninvasive, safe, simple-to-implement, and accurate method for the detection and differentiation of malignant melanoma versus benign nevi.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank their industrial partner, Michelson Diagnostics in the United Kingdom, and The Office of Research at Wayne State University (Detroit, MI) for their support. We acknowledge AC Camargo Cancer Institute for providing OCT images used in this study. This work was funded by Institutional Research Grant number 14-238-04-IRG from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

S. Daveluy reports receiving a commercial research grant from InflaRx and has received speakers’ honoraria from Abbvie. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked advertisement in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1.Bharath A, Turner R. Impact of climate change on skin cancer. J R Soc Med 2009;102:215–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karimkhani C, Green AC, Nijsten T, Weinstock M, Dellavalle RP, Naghavi M, et al. The global burden of melanoma: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Br J Dermatol 2017;177:134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman RJ, Rigel DS, Kopf AW. Early detection of malignant melanoma: the role of physician examination and self-examination of the skin. CA Cancer J Clin 1985;35:130–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas L, Tranchand P, Berard F, Secchi T, Colin C, Moulin G. Semiological value of ABCDE criteria in the diagnosis of cutaneous pigmented tumors. Dermatology 1998;197:11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson RL, Yentzer BA, Isom SP, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. How good are US dermatologists at discriminating skin cancers? A number-needed-to-treat analysis. J Dermatol Treatment 2012;23:65–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arpaia N, Cassano N, Vena GA. Dermoscopic patterns of dermatofibroma. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:1336–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skvara H, Teban L, Fiebiger M, Binder M, Kittler H. Limitations of dermoscopy in the recognition of melanoma. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elbaum M, Kopf AW, Rabinovitz HS, Langley RG, Kamino H, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Automatic differentiation of melanoma from melanocytic nevi with multispectral digital dermoscopy: a feasibility study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pellacani G, Guitera P, Longo C, Avramidis M, Seidenari S, Menzies S. The impact of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy for the diagnostic accuracy of melanoma and equivocal melanocytic lesions. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:2759–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frinking PJ, Bouakaz A, Kirkhom J, Ten Cate FJ, De long N. Ultrasound contrast imaging: current and new potential methods. Ultrasound Med Biol 2000;26:965–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh J-T, Li M-L, Zhang HF, Maslov K, Wang LV. Three-dimensional imaging of skin melanoma in vivo by dual-wavelength photoacoustic microscopy. J Biomed Opt 2006;11:034032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y, Tripathi SV, Rosman I, Ma J, Hai P, Linette GP, et al. Noninvasive determination of melanoma depth using a handheld photoacoustic probe. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137:1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelickson AS. The fine structure of the human melanotic and amelanotic malignant melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 1962;39:605–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monheit G, Cognetta AB, Ferris L, Rabinovitz H, Gross K, Martini M, et al. The performance of MelaFind: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michalska M, Chodorowska G, Krasowska D. SIAscopy-a new non-invasive technique of melanoma diagnosis. Ann Univ Mariae Curie-Sklodowska Med 2004;59:421–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink C, Haenssle H. Non-invasive tools for the diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. Skin Res Technol 2017;23:261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomatis S, Carrara M, Bono A, Bartoli C, Lualdi M, Tragni G, et al. Automated melanoma detection with a novel multispectral imaging system: results of a prospective study. Phys Med Biol 2005;50:1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lui H, Zhao J, McLean DI, Zeng H. Real-time Raman spectroscopy for in vivo skin cancer diagnosis. Cancer Res 2012;4061:2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malvehy J, Hauschild A, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Mohr P, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Motley R, et al. Clinical performance of the Nevisense system in cutaneous melanoma detection: an international, multicentre, prospective and blinded clinical trial on efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol 2014; 171:1099–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Leary S, Fotouhi A, Turk D, Sriranga P, Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Nouri K, et al. OCT image atlas of healthy skin on sun-exposed areas. Skin Res Technol 2018;24:570–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman AJ, Richardson TJ, Orchard G, Uddin A, Choi MJ, Lacy KE. Histological correlates of optical coherence tomography in non-melanoma skin cancer. Skin Res Technol 2013;19:10–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welzel J, Lankenau E, Birngruber R, Engelhardt R. Optical coherence tomography of the human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;37: 958–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierce MC, Strasswimmer J, Park BH, Cense B, de Boer JF. Advances in optical coherence tomography imaging for dermatology. J Invest Dermatol 2004;123:458–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hielscher AH, Mourant JR, Bigio IJ. Influence of particle size and concentration on the diffuse backscattering of polarized light from tissue phantoms and biological cell suspensions. Appl Opt 1997;36: 125–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craig FB, Bohren F, Huffman D. Absorption and scattering of light by small particles. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adabi S, Conforto S, Hosseinzadeh M, Noe S, Daveluy S, Mehregan D, et al. Textural analysis of optical coherence tomography skin images: quantitative differentiation between healthy and cancerous tissues. Proceedings of SPIE 2017;10053:100533F–1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajabi-Estarabadi A, Bittar JM, Zheng C, Nascimento V, Camacho I, Feun LG, et al. Optical coherence tomography imaging of melanoma skin cancer. Lasers Med Sci 2018. December 11 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adabi S, Fotouhi A, Xu Q, Daveluy S, Mehregan D, Podoleanu A, et al. An overview of methods to mitigate artifacts in optical coherence tomography imaging of the skin. Skin Res Technol 2018;24:265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hojjatoleslami A, Avanaki M. OCT skin image enhancement through attenuation compensation. Appl Opt 2012;51:4927–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adabi S, Turani Z, Fatemizadeh E, Clayton A, Nasiriavanaki M. Optical coherence tomography technology and quality improvement methods for optical coherence tomography images of skin: a short review. Biomed Eng Comput Biol 2017;2017:0–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adabi S, Hosseinzadeh M, Noei S, Conforto S, Daveluy S, Clayton A, et al. Universal in vivo textural model for human skin based on optical coherence tomograms. Sci Rep 2017;7:17912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gossage KW, Tkaczyk TS, Rodriguez JJ, Barton JK. Texture analysis of optical coherence tomography images: feasibility for tissue classification. J Biomed Opt 2003;8:570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raupov DS, Myakinin OO, Bratchenko IA, Zakharov VP, Khramov AG. Multimodal texture analysis of OCT images as a diagnostic application for skin tumors. J Biomed Photon Eng 2017;3:010307. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raupov DS, Myakinin OO, Bratchenko IA, Zakharov VP, Khramov AG. Skin cancer texture analysis of OCT images based on Haralick, fractal dimension, Markov random field features, and the complex directional field features. Proceedings of SPIE 2016; 10024:1002441. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thrane L, Yura HT, Andersen PE. Analysis of optical coherence tomography systems based on the extended Huygens-Fresnel principle. J Opt Soc Am A 2000;17:484–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmitt IM, Knüttel A, Yadlowsky M, Eckhaus M. Optical-coherence tomography of a dense tissue: statistics of attenuation and backscattering. Phys Med Biol 1994;39:1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adegun OK, Tomlins PH, Hagi-Pavli E, Mckenzie G, Piper K, Bader DL, et al. Quantitative analysis of optical coherence tomography and histopathology images of normal and dysplastic oral mucosal tissues. Lasers Med Sci 2012;27:795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubo T, Xu C, Wang Z, van Ditzhuijzen NS, Bezerra HG. Plaque and thrombus evaluation by optical coherence tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;27:289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Q, Wu X, Tang T, Zhu S, Yao Q, Gao BZ, et al. Quantitative analysis of rectal cancer by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Phys Med Biol 2012;57:5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avanaki MR, Podoleanu AG, Schofield JB, Jones C, Sira M, Liu Y, et al. Quantitative evaluation of scattering in optical coherence tomography skin images using the extended Huygens-Fresnel theorem. Appl Opt 2013;52: 1574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yura HT, Thrane L, Andersen PE. Closed-form solution for the Wigner phase-space distribution function for diffuse reflection and small-angle scattering in a random medium. J Opt Soc Am A 2000;17:2464–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levitz D, Thrane L, Frosz M, Andersen P, Andersen C, Andersson-Engels S, et al. Determination of optical scattering properties of highly-scattering media in optical coherence tomography images. Opt Express 2004; 12: 249–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nievergelt J. Exhaustive search, combinatorial optimization and enumeration: exploring the potential of raw computing power In: Hlaváč V, Jeffery KG, Wiedermann J (eds) SOFSEM 2000: Theory and Practice of Informatics. SOFSEM 2000. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 1963 Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2000. pp. 18–35. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Varkentin A, Otte M, Meinhardt-Wollweber M, Rahlves M, Mazurenka M, Morgner U, et al. Simple model to simulate oct-depth signal in weakly and strongly scattering homogeneous media. J Opt 2016; 18:125302. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aemouts B, Van Beers R, Watté R, Huybrechts T, Jordens J, Vermeulen D, et al. Effect of ultrasonic homogenization on the Vis/NIR bulk optical properties of milk. Colloids Surf B 2015;126:510–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Theodoridis S, Koutroumbas K. Pattern recognition. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burman P. A comparative study of ordinary cross-validation, v-fold cross-validation and the repeated learning-testing methods. Biometrika 1989;76: 503–14. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turchin IV, Sergeeva EA, Dolin LS, Kamensky VA, Shakhova NM, Richards-Kortum R. Novel algorithm of processing optical coherence tomography images for differentiation of biological tissue pathologies. J Biomed Opt 2005;10:064024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turchin IV, Sergeeva EA, Dolin LS, Shakhova NM, Richards-Kortum RR. Novel algorithm of processing optical coherence tomography images for differentiation of biological tissue pathologies. J Biomed Opt 2005; 10: 064024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stocker S, Foschum F, Krauter P, Bergmann F, Hohmann A, Scalfi Happ C, et al. Broadband optical properties of milk. Appl Spectrosc 2017;71: 951–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prahl S. Mie scattering calculator. Available from: http://omlc.org/calc/mie_calc.html.

- 52.Rhodes AR, Melski JW, Sober AJ, Harrist TJ, Mihm MC Jr, Fitzpatrick TB. Increased intraepidermal melanocyte frequency and size in dysplastic melanocytic nevi and cutaneous melanoma. A comparative quantitative study of dysplastic melanocytic nevi, superficial spreading melanoma, nevocellular nevi, and solar lentigines. J Invest Dermatol 1983;80:452–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Basavanhally A, Viswanath S, Madabhushi A. Predicting classifier performance with limited training data: applications to computer-aided diagnosis in breast and prostate cancer. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braun RP, Rabinovitz HS, Oliviero M, Kopf AW, Saurat JH. Pattern analysis: a two-step procedure for the dermoscopic diagnosis of melanoma. Clin Dermatol 2002;20:236–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marghoob AA, Korzenko AJ, Changchien L, Scope A, Braun RP, Rabinovitz H. The beauty and the beast sign in dermoscopy. Dermatol Surg 2007;33: 1388–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.