Microwave-assisted click reaction endowed cyclodextrin with amphiphilic structure leading to bacteriocidal membrane disruption, no development of resistance, and no haemolysis.

Microwave-assisted click reaction endowed cyclodextrin with amphiphilic structure leading to bacteriocidal membrane disruption, no development of resistance, and no haemolysis.

Abstract

A membrane-active antimicrobial peptide gramicidin S-like amphiphilic structure was prepared from cyclodextrin. The mimic was a cyclic oligomer composed of 6-amino-modified glucose 2,3-di-O-propanoates and it exhibited antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, together with no resistance development and low haemolytic activity against red blood cells.

Introduction

‘We estimate that by 2050, 10 million lives a year and a cumulative 100 trillion USD of economic output are at risk due to the rise of drug-resistant infections if we do not find proactive solutions now to slow down the rise of drug resistance’.1 At present, 90 years after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, the antimicrobial resistance of bacteria is a serious threat facing mankind. In Europe, approximately 25 000 people die every year from antibiotic-resistant infections.2 There is thus a need to develop new antibiotics with alternative mechanisms of action to combat antimicrobial resistance. Within this context, antimicrobial peptides have attracted attention as new agents against drug-resistant bacteria.3–6 The peptides disrupt bacterial membranes through the interaction of their positively charged amino groups with the negatively charged bacterial cell membranes and the interaction of their hydrophobic moieties with apolar lipid acyl chains in the membranes, resulting in broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity.7,8 In addition, compared with conventional antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides may lead to the slower development of resistance because cell membrane alteration can be metabolically expensive.6,9,10 The peptides inspired us to develop a new series of antimicrobial compounds made from cyclic oligosaccharides called cyclodextrins (CDs). The CD derivatives possessed alkylamino groups as membrane active functionalities that strongly disrupt the bacterial membrane; their antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria was also demonstrated to be higher than that against Gram-negative bacteria.11 The World Health Organisation (WHO) has paid attention to the threat of Gram-negative bacteria that are resistant to multiple antibiotics on a list of priority pathogens for research and development of new antibiotics.12 A clue to a novel CD derivative active against Gram-negative bacteria was provided by antimicrobial peptide gramicidin S and its analogue.

A cyclic decapeptide gramicidin S with an amphiphilic structure possessing two amino groups of the Orn residues on one side of the β-sheet plane and the alkyl chain of the Val and Leu residues on the other side exhibits strong antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 1).13–15 Meanwhile, the introduction of additional amino groups onto gramicidin S exhibited broader-spectrum antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.16,17 Furthermore, the chemical modification reduced toxicity against red blood cells. Based on previous research on gramicidin S analogues we designed novel γ-CD derivatives. γ-CD comprises eight glucose residues, and the diameter of the CD cone structure is ∼1 nm, which is comparable to that of a gramicidin S molecule. To mimic an amphiphilic structure of gramicidin S, where the cationic and hydrophobic regions are structurally separated, eight cationic amino groups were introduced at the primary hydroxy end on the γ-CD cone and 16 hydrophobic acyl groups were at the secondary hydroxy end. Here, the amino groups on the CD molecule were more numerous than those on native gramicidin S, and different types of alkyl moieties such as i-Pr and i-Bu groups on the peptide were simplified to one type of acyl group, such as a propanoyl group.

Fig. 1. Structure of the antimicrobial peptide gramicidin S and its CD mimic.

Results and discussion

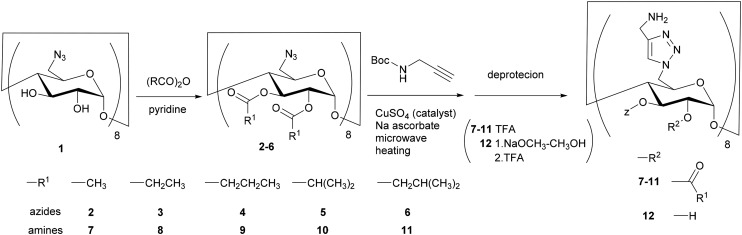

The CD derivatives were synthesised as illustrated in Scheme 1. The difference in reactivity between primary hydroxy groups and secondary hydroxy groups of a CD molecule was utilised for sequential modification and the primary hydroxy groups were first converted to azide groups [octakis(6-azido-6-deoxy) γ-CD, 1].18 Next, secondary hydroxy groups of azide 1 were reacted with the corresponding acid anhydride to yield azide acylates 2–6. Here, the acyl groups were linear and branched structures, and their carbon number was varied from 2 to 5. To introduce eight amino groups onto a CD molecule, we used the microwave (MW)-assisted Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction developed in previous research.11,18–20 Octakis(6-azido-6-deoxy-2,3-O-propanoyl)-CD 3 was reacted with Boc-protected propargylamine in the presence of a copper catalyst. MW heating (120 °C) for 10 min attached the Boc-protected amino groups onto the γ-CD molecule (73.6%). The Boc groups were subsequently deprotected, affording the desired CD 8 as its trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) salt (95.1%). Amines 7 and 9–12 were similarly prepared from the corresponding azides 2 and 4–6, respectively, whose two-step overall yields were approximately ≥70%. These results demonstrate that MW-assisted click reactions are advantageous for poly-amino functionalization.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of gramicidin S-like CD derivatives.

The inhibition of bacterial proliferation by the CDs was evaluated using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against Gram-negative strains of Escherichia coli, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Gram-positive strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis (Table 1). Notably, amongst the six amino γ-CD acylates 7–12, only propanoate 8 whose hydrophobic group was linear and not branched as that in the peptide, was found to effectively inhibit bacterial growth. MIC values of 8 against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria were ≤9 μM, whereas those of other acylates 7 and 9–11 and OH-free 12 were ≥31 μM. Notably, the CD derivative 8 possessing eight amino groups and structurally separated cationic and hydrophobic regions exhibited strong activity against not only Gram-positive but also Gram-negative bacteria, consistent with our expectations based on the aforementioned properties of the gramicidin S analogues16,17 and in contrast to the Gram-positive selective γ-CDs11 whose primary hydroxy end was modified with alkylamino groups. The functional groups and their position on the CD may determine the spectrum of antimicrobial activity.

Table 1. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC; μM) of CD derivatives against Gram-positive S. aureus and B. subtilis strains and Gram-negative E. coli, S. Typhimurium and P. aeruginosa strains a .

| Compounds |

Gram-positive strains |

Gram-negative strains |

||||||

| CD | Substituent on 2,3-O | log P b | S. aureus | B. subtilis | E. coli | S. Typhimurium | P. aeruginosa | |

| 7 | γ | Acetyl | –2.20 | >36 | >36 | >36 | >36 | >36 |

| 8 | γ | Propanoyl | –0.89 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 4 |

| 9 | γ | n-Butanoyl | –0.06 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| 10 | γ | 2-Methyl-propanoyl | 0.24 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >31 | 31 |

| 11 | γ | 3-Methyl-butanoyl | 0.60 | >31 | >31 | >31 | >43 | >43 |

| 12 | γ | H | –2.66 | >45 | 22 | >45 | >45 | >45 |

| 13 | α | Propanoyl | –0.89 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 |

| 14 | β | Propanoyl | –0.89 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Gramicidin S c | 4 | 28 | ||||||

| Daptomycin | 3 | |||||||

| Colistin d | 0.7 | 2 | ||||||

aMICs are determined using the liquid microdilution method.

bValues of the corresponding substituted glucose.

cSee ref. 11.

dAs (C52H98N16O13)2·5H2SO4.

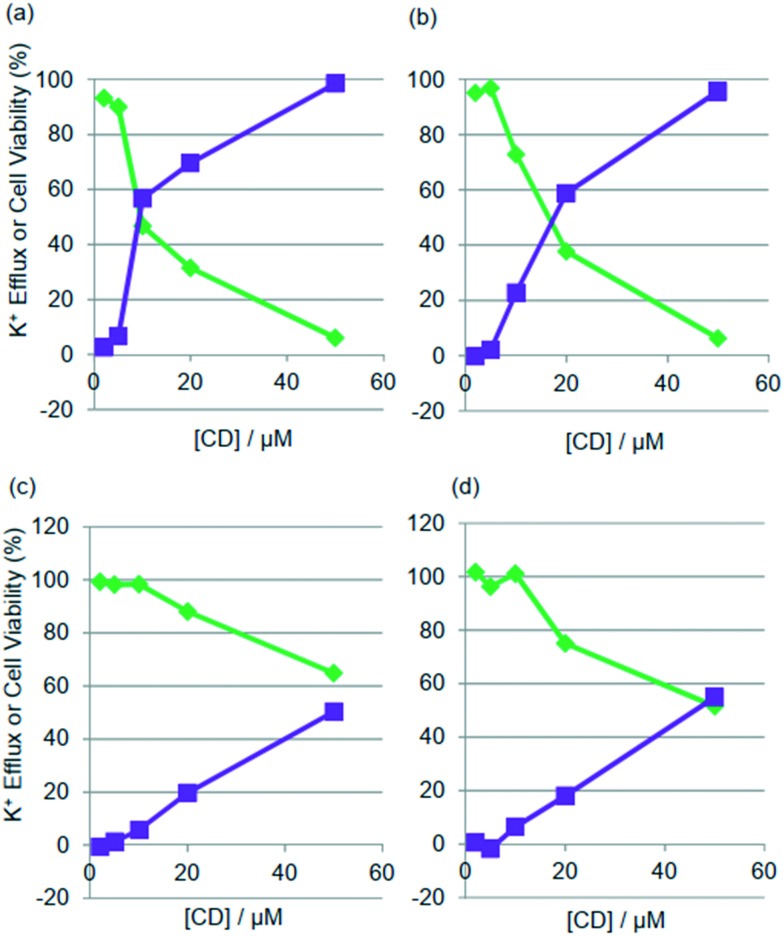

To determine whether the observed antimicrobial activity of the CD derivative 8 was attributable to membrane disruption, the cytoplasmic membrane-disrupting abilities of the CDs were examined. Each of the compounds 7–9 was applied to bacteria, where the K+ efflux from the bacterial cells was measured using a K+ electrode and changes to cell viability were simultaneously assayed.18 Bacteria have high concentrations of K+ (100–500 mM) within them, and permeabilisation of their cytoplasmic membranes causes ion efflux.21 Propanoate 8 exhibited substantial K+ efflux from Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative E. coli, and increases in the K+ efflux were proportional to decreases in the cell viability (Fig. 2a and b). By contrast, the less antimicrobial acetate 7 (Fig. 2c and d) and n-butanoate 9 (see ESI†) were found to exhibit much lower permeabilisation and less cell death than 8. The native CD molecule exhibited neither K+ efflux nor a decrease in cell viability (see ESI†). These results provide direct evidence that the site of action of CD 8 was the cytoplasmic membranes of the Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Generally, three main models explaining the mechanism of action of antimicrobial peptides have been suggested: the barrel-stave pore, the toroidal pore and the carpet model.22–24 The CDs here appear to differ from α-helical peptides and be incapable of forming a transmembrane pore structures. Gramicidin S is considered to be located at the polar/apolar interfacial region of membrane phospholipid bilayers, penetrate deeply into the bilayers and permeabilise the membrane.25 Presumably, the CDs may interact with the bacterial membrane in a carpet-like manner and permeabilise phospholipid bilayers as gramicidin S does.

Fig. 2. Dose-dependent curves for K+ efflux and cell viability of bacteria upon addition of propanoate 8 ((a) S. aureus, (b) E. coli) and acetate 7 ((c) S. aureus and (d) E.coli). Purple lines: K+ efflux, green lines: cell viability. Cells are incubated with the CD derivative for 30 min at 37 °C. To determine the 100% level of K+ efflux, melittin (10 μM for S. aureus) and polymixin B (200 μg cm–3 for E. coli) are used.

The toxicity of amino acylates 7–12 against rabbit's red blood cells was evaluated through hemolysis; the results revealed that the CDs 7, 8, and 12 (OH, acetate, and pronanoate, respectively) were only slightly or not haemolytic and the 9–11 (butanoate and pentanoate) were very haemolytic (at 50 μM, 7 1%, 8 17%, 9 102%, 10 101%, 11 87%, 12 ∼0%). The CD possessing larger acyl groups may be more haemolytic. Therefore, the observed haemolytic activity is discussed from the viewpoint of correlation with molecular hydrophobicity. Herein, we used the partition coefficient logarithm (log P) value as a measure of the hydrophobicity of a compound. The correlation of the haemolytic activity of CDs 7–12 and also alkylamino-modified γ-CDs 15–2811 with the log P values of the corresponding substituted glucose of CDs is shown in Fig. 3a. The results demonstrate that the membrane-permeabilising activity of amino acylates and alkylamino CDs (at 50 μM) against red blood cells drastically changed at log P values of approximately –0.1. The more hydrophilic CDs were, the less haemolytic activity; therefore, propanoate 8 with a log P value of –0.89 was less haemolytic. The structures of 7–12 with amino groups on the primary hydroxyl end and acyl groups on the secondary end of the CD molecule differ completely from those of CDs 15–28 with alkylamino groups on the primary hydroxyl end. However, the two types of CD derivatives notably exhibited similar hydrophobicity–haemolytic activity correlation. Meanwhile, propanoate 8 exhibited good antimicrobial activity, whereas the more hydrophobic butanoates and pentanoate (9, 10, and 11) and the less hydrophobic CDs (acetate 7 and OH 12) were less effective. These findings may suggest that the hydrophilicity–hydrophobicity balance suitable for disrupting the bacterial cell membrane differs from that suitable for interacting with the red blood cell membrane. The correlation of the antimicrobial activity of amino CD acylates 7–12 with their hydrophobicity (the log P values of the corresponding substituted glucose) is illustrated, together with those of the alkylamino γ-CDs 15–28 whose MIC values against S. aureus, S. Typhimurium and P. aeruginosa were obtained here. MIC values against B. subtilis and E. coli were previously reported11 (in Fig. 3b and c for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa and in ESI† for other bacteria). The results demonstrate that alkylamino CDs with log P values from –1 to 0 exhibit smaller MIC values against Gram-positive bacteria than the CDs with log P values outside this range, whereas the amino propanoate 8, with a log P value of –0.89, exhibited good antimicrobial activity. The more hydrophobic CDs (9, 10 and 11) and the less hydrophobic CDs (7 and 12) were less effective. The correlation in the case of Gram-negative bacteria was unique. The log P region over which alkylamino CDs were antimicrobial (MIC < 20 μM) for E. coli was –0.5 ≤ log P ≤ 0.0, whereas that for S. Typhimurium and P. aeruginosa was specifically around log P = –0.1. Amino propanoate 8 is slightly outside the optimal region, and it is antimicrobial against all three investigated pathogens. The 1,2,3-triazole group is considered as a surrogate of an amide group.26 The triazole group may contribute to enhancement of the hydrophilicity of the CDs and adjust the hydrophobicity-hydrophilicity balance for the biological activities.

Fig. 3. Relation of log P values of amino γ-CD acylates 7–12 and alkylamino derivatives 15–28 with their haemolytic activity (a) as well as MICs against Gram-positive S. aureus (b) and Gram-negative P. aeruginosa (c). Blue dots: amino acylates 7–12; orange dots: alkylamino derivatives 15–28. Lysolethicin (50 μM) was used to determine the 100% level of hemolysis.

We prepared α- and β-CD analogues of γ-CD 8, particularly 13 and 14, which comprise of six and seven 6-amino-modified glucose 2,3-di-O-propanoates, respectively. Both of the α- and β-CD derivatives 13 and 14 exhibited strong antimicrobial activity comparable to that of γ-CD analogue 8 and those of daptomycin and colistin (Table 1). In addition, the haemolytic activity of α-CD 13 (50 μM) was 3%, whereas those of β-CD 14 and γ-CD 8 were ∼20%. At a concentration almost 10 times its MIC, 13 was not toxic to red blood cells. Therefore, we examined the resistance development against the most promising α-CD, namely 13. Serially exposing bacteria to 13 at doses below lethal concentrations and monitoring the changes in the MIC values27 over 11 passages demonstrated that the MIC value of 13 against S. aureus remained the same (6 μM) (Fig. 4). By contrast, the MIC value of fosfomycin, a broad-spectrum clinically used antibiotic, started to increase from 14 μM after the second passage. At the fourth passage, it became >927 μM, which is more than 64 times greater than that at the first passage. Norfloxacin, a clinically used fluoroquinone, gradually increased its MIC value from 0.8 to 3 μM to become almost four times greater. In the case of E. coli, the MIC value of CD 13 remained almost the same (3–6 μM), whereas those of fosfomycin and norfloxacin increased 16 times and above (for fosfomycin, from 58 to >927 μM; for norfloxacin, from 0.2 to 6 μM). The results of this multipassage resistance study indicate that CD 13 may be resistant to bacteria acquiring resistance to it, presumably because it exhibits a membrane-disrupting mechanism similar to that of natural antimicrobial peptides.28

Fig. 4. Multi-passage resistance studies of 13 against (a) S. aureus and (b) E. coli. Blue lines: CD 13, grey lines: fosfomycin, red lines; norfloxacin.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed unique membrane-active antimicrobial CD derivatives that exhibited good antimicrobial activity comparable to that found for natural peptides, less haemolytic activity and less bacterial resistance development. Preliminary experiments suggested that the amino propanoates were active against clinically isolated drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. The MIC values of amino propanoates γ (8), β (14), and α (13) against extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E.coli were 4, 5, and 6 μM, respectively. Furthermore, MIC values of 8, 14, and 13 against carbapenem-resistant E.coli were 9, 5, and 11 μM, respectively, and those against carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa were 9, 5, and 6 μM, respectively. The last two pathogens belong to a critical priority group on the WHO list. The antimicrobial activity of CDs described in this paper is comparable but not superior to those of colistin and daptomycin at present. Nevertheless, the versatile derivatisation of CDs may provide optimised lead structures with desired activities to be developed for new antibiotic compounds. Further research in this field is underway.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. R. Naito and Mr. S. Nakagawa for technical assistance. This work was supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research grant number 15K07857.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Syntheses of the compounds and bioactivity assays. See DOI: 10.1039/c9md00229d

References

- O'neill J., Tackling Drug-resistant Infections globally: Final Report and Recommendations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2015, Annual report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zavascki A. P., Goldani L. Z., Li J., Nation R. L. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:1206. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. Nature. 2002;415:389. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. E. W., Sahl H. G. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1551. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bambeke F., Mingeot-Leclercq M. P., Struelens M. J., Tulkens P. M. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;29:124. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimley W. C. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:905. doi: 10.1021/cb1001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog I. N., Fridman M. Med. Chem. Commun. 2014;5:1014. [Google Scholar]

- Yeaman M. R., Yount N. Y. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003;55:27. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell K. M. G., Hodgkinson J. T., Sore H. F., Welch M., Salmond G. P. C., Spring D. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:10706. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura H., Miyagawa A., Sugiyama H., Murata K., Mabuti T., Mitsuhashi R., Hagiwara T., Nonaka M., Tanimoto K., Tomita H. ChemistrySelect. 2016;3:469. [Google Scholar]

- Global Priority List of Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. 27 February 2017, WHO.

- Waki M. and Izumiya N., in Biochemistry of Peptide Antibiotics. Recent Advances in the Biotechnology of β-Lactams and Microbial Bioactive Peptides, ed. H. Kleinhauf and H. von Döhren, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin,·New York, 1990, ch. 9, p. 205. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. L., Hodges R. S. Biopolymers. 2003;71:28. doi: 10.1002/bip.10374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Unno M., Kobayashi K., Oku H., Yamamura H., Araki S., Matsumoto H., Katakai R., Kawai M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12684. doi: 10.1021/ja020307t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M., Tanaka R., Yamamura H., Yasuda K., Narita S., Umemoto H., Ando S., Katsu T. Chem. Commun. 2003:1264. doi: 10.1039/b302351f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M., Yamamura H., Tanaka R., Umemoto H., Ohmizo C., Higuchi S., Katsu T. J. Pept. Res. 2005;65:98. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura H., Sugiyama Y., Murata K., Yokoi T., Kurata R., Miyagawa A., Sakamoto K., Komagome K., Inoue T., Katsu T. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:5444. doi: 10.1039/c3cc49543d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura H., Nonaka M., Okuno S., Mitsuhashi R., Kato H., Katsu T., Masuda K., Tanimoto K., Tomita H., Miyagawa A. MedChemComm. 2018;9:509. doi: 10.1039/c7md00592j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura H., Shimohara K., Kurata R., Fujita Y., Murata K., Hayashi T., Miyagawa A. Chem. Lett. 2013;(6):643. [Google Scholar]

- Katsu T., Nakagawa H., Yasuda K. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1073. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.1073-1079.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann G., Mueller P. J. Supramol. Struct. 1974;2:538. doi: 10.1002/jss.400020504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki K., Murase O., Tokuda H., Fujii N., Miyajima K. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11361. doi: 10.1021/bi960016v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouny Y., Rapaport D., Mor A., Nicholas P., Shai Y. Biochemistry. 1992;31:12416. doi: 10.1021/bi00164a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenner E. J., Lewis R. N. A. H., Neuman K. C., Gruner S. M., Kondejewski L. H., Hodges R. S., McElhaney R. N. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7906. doi: 10.1021/bi962785k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed I., Kummetha I. R., Singh G., Sharova N., Lichinchi G., Dang J., Stevenson M., Rana T. M. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:19. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J. J., Lin S., Aung T. T., Lim F., Zou H., Bai Y., Li J., Lin H., Pang L. M., Koh W. L., Salleh S. M., Lakshminarayanan R., Zhou L., Qiu S., Pervushin K., Verma C., Tan D. T. H., Cao D., Liu S., Beuerman R. W. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:739. doi: 10.1021/jm501285x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koczulla A. R., Bals R. Drugs. 2003;63:389. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.